Abstract

We measured epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs and DHETs) in 21 normotensive subjects classified as salt-resistant (SR=13) or salt-sensitive (SS=8) with an in-patient protocol of salt loading (460 mEq Na+/24 hrs, HiNa) and depletion (10 mEq Na+/24 hrs + furosemide 40 mg × 3, LoNa). No urine EETs were detected; hence, ELISA 14–15 DHETs were considered the total converted 14–15 urine pool (UTP). We report UPLC-MS plasma EETs, DHETs and their sum (plasma total pool, PTP) for the three regioisomers (8–9, 11–12, 14–15) and their sum (08–15). In SR, UTP was unchanged by HiNa, decreased by LoNa, and correlated with UNaV, fractional excretion of Na+ and Na+/K+ ratio over the three days of the experiment (p<0.03). In contrast, PTP increased in LoNa, did not correlate with natriuresis or Na+/K+ ratio but showed correlations between EETs, blood pressures (BP) and catecholamines and between DHETs and aldosterone (p<0.03). UTP of SS was lower than that of SR in certain phases of the experiment, lacked responses to changes in salt balance, and exhibited limited correlations with natriuresis and Na+/K+ ratio during LoNa only. PTP of SS was lower than in SR, did not correlate with BP or aldosterone, but did with catecholamines. We conclude that UTP reflects a renal pool involved in regulation of natriuresis whereas PTPs are of systemic origin, uninvolved in Na+ excretion, perhaps contributing to regulation of vascular tone. Data suggest that abnormalities in epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in SS participate in their renal or vascular dysfunction, which has potential therapeutic implications.

Keywords: CYP450 eicosanoids, Salt Sensitive, Blood Pressure, Cardiovascular Physiology, Renal Physiology, Catecholamines, Aldosterone

Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) are products of epoxygenation of arachidonic acid. They participate in cardiovascular regulation via vasodilator and natriuretic effects. Research on their actions used urine or plasma measurements of their four active regioisomers (5–6, 8–9, 11–12 and 14–15 EETs) and their relatively inactive derivatives, the dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids or DHETs. The latter are produced by enzymatic (soluble epoxide hydrolase or sEH) or non-enzymatic (e.g., pH, oxidative stress) degradation.

Previous studies in animals suggested that urine and plasma EETs may reflect two distinct pools with different functions. The volume of distribution of intravenous radiolabeled 14,15-EET in dogs approximates their plasma volume and no radioactivity can be detected in their urine1. Plasma EET responses to regulatory PPARα ligands in mice run parallel to Cyp2c epoxygenase expression and EET biosynthesis in the liver2. These studies suggest that plasma EETs reflect a systemic, not a renal pool. Conversely, increased renal EET content produced by dopamine agonists in mice is not associated with changes in plasma EETs3, indicating that the renal EET pool might be better reflected by urine measurements. Our first aim was to assess whether these putative pools could be uncovered by studying clinical and biochemical correlates of urine and plasma EETs in normal volunteers; i.e., normotensive, salt resistant (SR) subjects, during salt loading and depletion.

EETs may play a role in salt sensitivity of blood pressure (SSBP). Salt stimulates renal microsomal biosynthesis of EETs in normal Sprague Dawley4 and Dahl-R rats5, whereas this response is absent in the salt sensitive (SS) Dahl-S strain, leading to hypertension with reduced renal expression of the epoxygenase CYP2C23 and urine excretion of EETs5. In SR rats, the epoxygenase inhibitor clotrimazole decreases urinary EETs and reproduces SS hypertension5. Cyp4a10 knockout mice, which have reduced renal epoxygenase (Cyp2c44) activity6, and the Cyp2c44 knockout7, have diminished urine EETs and amiloride-sensitive hypertension. This is associated with decreased inactivating threonine phosphorylation of γENaC7, which is reversible by the PPARα ligands that stimulate epoxygenases6. Our second aim was to investigate whether SS subjects exhibit differences in urine or plasma EETs levels, in their responses to changes in salt balance or in their clinical or biochemical correlates compared to SR. To avoid confounding effects of established hypertension, we carried out these studies in normotensive volunteers.

METHODS

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article [and its online supplementary files].

Subjects and Protocol

21 normotensive volunteers participated in an Institutional Review Board–approved (Scott and White Hospital) protocol to assess SSBP and to measure urine and plasma epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. After 2 weeks on their habitual salt intake, we obtained demographic and clinical characteristics, physical examinations and routine laboratory data. We verified that there were no excluding illnesses and that blood pressure was <140 mm Hg systolic and <90 diastolic. Subjects brought a 24-hour urine specimen and were admitted to the research ward the night before starting a protocol adapted from Grim et al8 as previously reported9. Briefly, after baseline clinical and laboratory data (Base day), subjects had a 460 mEq Na+ load (160 mEq in metabolic kitchen diet and 2 L intravenous normal saline from 8:00 am to 12:00 noon; salt loading or HiNa day). The next morning, after obtaining clinical and laboratory data representing salt loading, salt depletion was produced with an isocaloric 10 mEq Na+/d diet and 3 oral 40 mg doses of furosemide at ≈8:00 am, 12:00 noon, and 4:00 pm (LoNa day). The following morning, subjects were discharged from the hospital, after obtaining clinical and laboratory data representing salt depletion. Potassium intake was 70 mEq/day and oral fluid intake was ad libitum throughout the study. BP (SpaceLabs 90207) was recorded every 15 minutes from 6:00 am to 10:00 pm and every 30 minutes overnight. Baseline BP was the average from awakening on HiNa until starting the saline infusion. HiNa BP was the average from 12:00 noon (after the saline infusion) until 10:00 pm (time to retire to bed) and LoNa BP was the average from 12:00 noon (after the second dose of furosemide) until 10:00 pm. A fall in systolic BP ≥10 mm Hg from HiNa to LoNa was used to classify a subject as SS. Body weights were measured daily, on awakening.

Laboratory data included blood counts, chemistries with electrolytes and creatinine, plasma renin activity, aldosterone and insulin (radioimmunoassay), and plasma catecholamines (radioenzymatic assay). Insulin sensitivity was the HOMA2-S index (www.dtu.ox.ac.uk)10. Urine specimens for four periods (24-hour Base day, 24-hour HiNa day, 12-hour LoNa day for furosemide-induced diuresis, and 12-hour LoNa day for salt depletion) were collected on ice and stored at −80C without additives. 12-hour periods for LoNa were chosen based on previous experience with duration of furosemide diuresis (10–11 hours). Data for the 12-hour salt depletion period were doubled for comparison with the 24-hour samples, analogous to using per hour data. Volumes, creatinines and electrolytes were recorded for each period. Creatinine clearance and fractional excretion of sodium were calculated.

Measurement of urinary EETs and DHETs

Active EETs were not detected by two different LC-MS/MS methods (see online supplement at http://hyper.ahajournals.org), which we attributed to long-term storage of the samples despite freezing at −80°C. Therefore, we measured levels of 14,15 DHET with a commercial ELISA kit (Eagle Biosciences) that uses a very specific antibody (<3% cross reactivity with other DHETs and <1% with other eicosanoids and like lipids). Results of these measurements were considered the urine total pool of 14–15 epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (14–15 UTP).

Measurement of plasma EETs and DHETs

Plasma EETs and DHETs were quantified in samples frozen and stored at −80°C using a previously published UPLC/MS/MS method11, (see online supplement). The main comparisons are between the total pools of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in urine (14–15 UTP) and plasma (08–15 PTP). Separate data for 08–15 EET and DHET, calculated activity of soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH=DHET/[EET+DHET]) and all data for each regioisomer are given in the supplement.

Statistical Analyses

Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, plasma aldosterone and salt excretion were not normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk) and are presented as log-transformed data, which became normally distributed datasets without outliers (Grubb’s test). Values are presented as mean±SEM. Comparisons between SS and SR subjects were made with unpaired Student’s t tests. Changes in parameters produced by changes in salt balance within the same subjects were analyzed with paired t tests. Correlation coefficients were calculated with Pearson method. All these tests and single-linear regression analyses were performed with JMP software (SAS Institute). A probability <5% was used to reject the null hypothesis. No subanalyses by gender or race were conducted, owing to small n’s.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the participants

Data on the 21 subjects (who had participated in a previously published study12) are in Table 1. Eight (38%) were classified as SS on the basis of their responses to salt depletion. There were no differences in age, gender distribution, renal function or plasma catecholamines between SS and SR. Urine sodium excretion on an ad libitum diet at home was similar to or higher than that of the average US population in both groups and did not differ between them. Blood pressures were below 140/90 mmHg in both groups but were significantly, albeit slightly higher in SS than in SR. Some traditional features of the SS phenotype (e.g., hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance and atherogenic dyslipidemia) were significantly different between SS and SR, whereas others (e.g., larger percent of black subjects, obesity and suppression of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system) showed only non-significant trends.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical and biochemical characteristics of the subjects

| Variable | SR (n=13) | p | SS (n=8) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 38.5 ± 2.5 | 40.6 ± 3.5 | |

| Gender, F/M (%/%) | 12/1(92/8) | 6/2(75/25) | |

| Race, B/W (%/%) | 1/12(8/92) | 2/6(25/75) | |

| SBP mmHg | 111.6 ± 2.8 | <0.01 | 125.1 ± 3.3 |

| DBP mmHg | 72.3 ± 2.4 | <0.01 | 82.6 ± 2.2 |

| ΔSBP (LoNa-HiNa) mmHg | −2.3 ± 1.1 | <0.0001 | −13.7 ± 1.6 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 29.0 ± 1.6 | 0.05<p<0.10 | 35.8 ± 3.6 |

| ClCr (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 148.1 ± 12.8 | 129.6 ± 12.6 | |

| UNaV (mmoL/day) at baseline | 145.8 ± 16.5 | 180.3±24.1 | |

| PRA (ngAI/ml/hr) | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | |

| Aldo (ng/dl) | 10.2 ± 1.4 | 0.05<p<0.10 | 7.9 ± 0.9 |

| Aldo/Renin ratio | 13 ± 3 | 19 ± 7 | |

| Plasma catecholamines (pg/ml) | 395 ± 75 | 252 ± 23 | |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 82±13 | <0.05 | 140±17 |

| HDL-cholesterol, mg/dl | 58±5 | <0.05 | 40±3 |

| Plasma insulin, mU/ml | 10.3±2.4 | <0.05 | 18.6±2.7 |

| HOMA2-S (%) | 110 ± 16 | <0.003 | 49 ± 7 |

SR, salt resistant; SS, salt sensitive; F, female; M, male; B, black; W, white; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; ΔSBP (LoNa-HiNa), decrease in blood pressure from the high-salt to the low-salt day; BMI, body mass index; ClCr, creatinine clearance; UNaV, urine sodium excretion; PRA, plasma renin activity; Aldo, plasma aldosterone; HOMA2-S, insulin sensitivity index. p-values are for the comparison of SR vs SS. Their absence indicates lack of statistical significance.

EET and DHET levels in urine and plasma of normal (SR) subjects and their responses to changes in salt balance

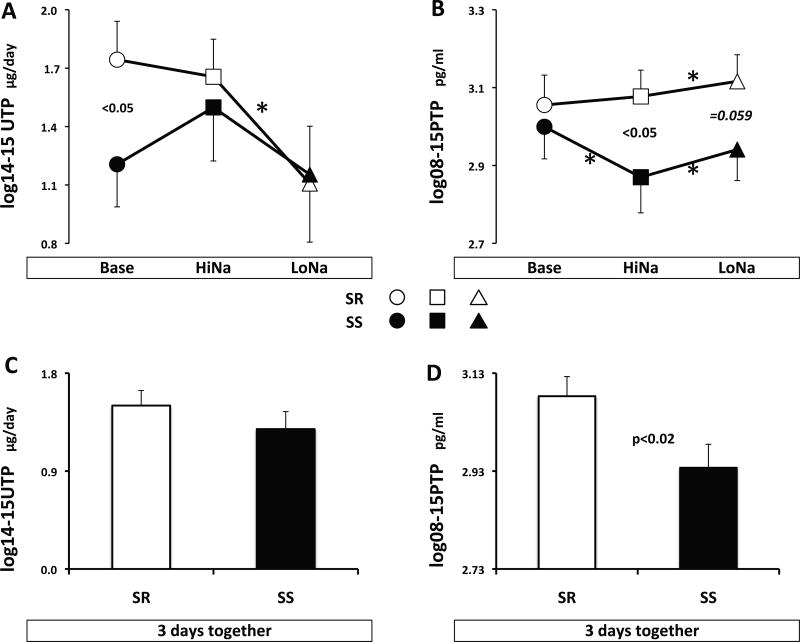

In normal (SR) subjects (open symbols, Figure 1), neither 14–15 UTP nor 08–15 PTP was changed by salt loading (panels A and B). Lack of change in 08–15 PTP by salt resulted from decreased sEH activity and DHETs with concomitant increase in plasma 08–15 EETs (consistent in all regioisomers and significant for some; ‡ in Table S1). In contrast, salt depletion produced opposite significant decreases in 14–15 UTP (Figure 1A) versus increases in 08–15 PTP (Figure 1B). The latter were due to increased plasma sEH activity and DHETs (consistent in all regioisomers and significant for some; § in Table S1) with concomitant albeit not significant increase in EETs. Hence, 14–15 UTP responses to salt depletion were consistent with those expected in a natriuretic system, whereas plasma epoxyeicosatrienoic acids changed in the opposite direction.

Figure 1.

Levels of 14–15 UTP and 08–15 PTP during each day of the protocol (panels A and B), or the three days together (panels C and D. SR=salt resistant, SS=salt sensitive. Symbols for each day of the experiment are indicated on the graph. Asterisks denote statistical significance between two consecutive days (paired t-test). P values are for significant or borderline differences in levels between SS and SR subjects (unpaired t-test).

EET and DHET levels in urine and plasma of SS subjects and their responses to changes in salt balance

14–15 UTP of SS was slightly but not significantly lower than in SR on all days combined (Figure 1C) and significantly lower on ad libitum salt intake at baseline (Figure 1A). In contrast, 08–15 PTP of SS was significantly lower than that of SR on all days combined (Figure 1D), a product of a significant difference in the high salt day and a borderline one in the low salt day (Figure 1B). Decreased 08–15 PTP of SS compared to SR was attributable to lower levels of EETs during salt loading and DHETs during salt depletion (* and † for the regioisomers in Table S1), without differences in sEH activity.

14–15 UTP responses to changes in salt balance were blunted in SS compared to SR, with their levels on an ad libitum diet at baseline being in the same range as those during salt depletion (Figure 1A). Plasma 08–15 PTP of SS decreased during salt loading owing to decreased 11–12 and 14–15 DHETs (‡ in Table S1). In contrast, it increased during salt depletion (Figure 1B) owing to increased DHET in all regioisomers (§ in Table S1), similar to changes in SR.

In summary, lower plasma EETs in SS than SR throughout the experiment, despite almost identical activity of sEH, suggests a deficit in either the expression or the activity of epoxygenases. Further, plasma responses to salt loading and depletion in SS were inconsistent with those expected from a natriuretic system.

UTP correlates in a different manner with natriuresis and activity of the epithelial sodium channel in SR and SS subjects

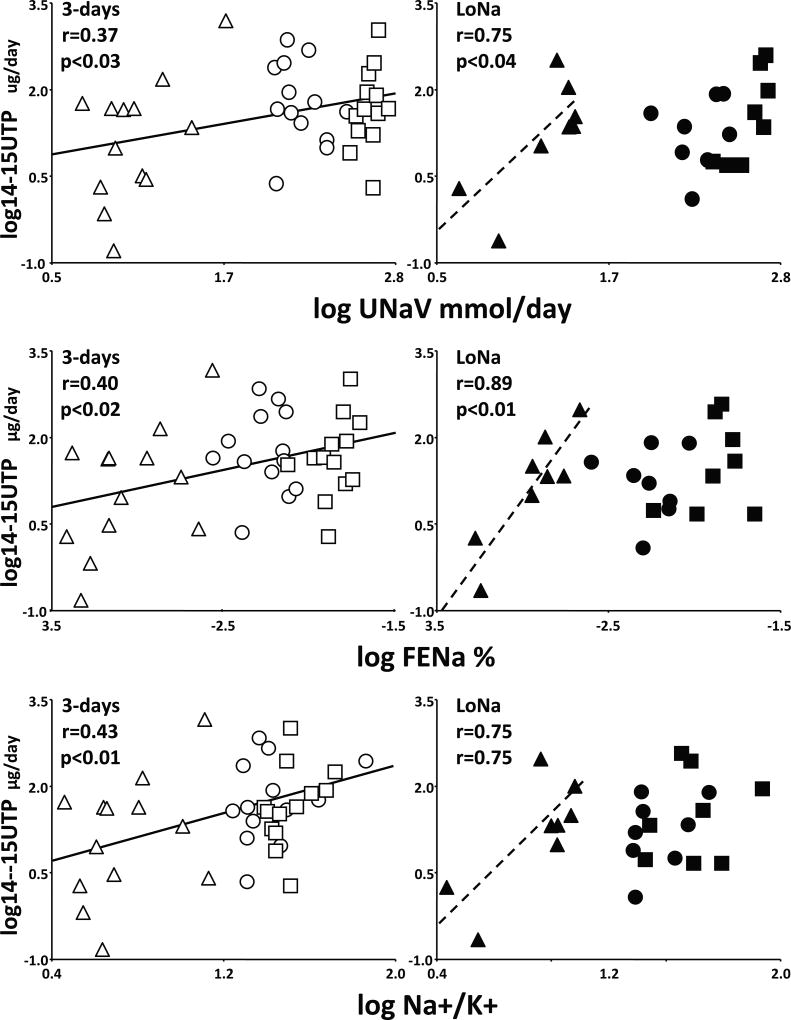

In SR, 14–15 UTP of the three days combined correlated with absolute natriuresis, fractional excretion of sodium and most importantly with the urine Na+/K+ ratio, a marker of inhibition of ENaC (Figure 2, left). The full range of UTP excretion (0.15 to 1463 µg/day) increased concomitantly with the full ranges of UNaV (4 to 563 mEq/day), FeNa (0.04 to 1.95%) and Na+/K+ ratio (2.8 to 58.5) over the three days of the experiment.

Figure 2.

Correlations of 14–15 UTP with daily urine sodium excretion (log UNaV), fractional excretion of sodium (log FENa) and sodium/potassium ratios (log Na+/K+). Data for SR and SS and for each day of the experiment are represented by the same symbols as in Figure 1. Solid regression lines are for SR over the three days of the experiment, whereas dashed ones are for SS during the salt depletion day (LoNa). Pearson’s r coefficients and their statistical significance are given on the graphs.

In contrast, 14–15 UTP of SS correlated with natriuresis and Na+/K+ ratio during LoNa only (Figure 2, right). A smaller full range of UTP excretion (0.22 to 301 µg/day) increased concomitantly with the restricted ranges of UNaV (4 to 23 mEq/day), FeNa (0.05 to 0.21%) and Na+/K+ ratio (2.8 to 10.0) observed during salt depletion. This resulted in steeper slopes in SS than in SR. For example, the regressions predict that at a UNaV of 20 mEq/day, SR subjects will excrete 17.03 µg/day of UTP, whereas SS will excrete 35.42 µg/day. At higher levels of natriuresis or ENaC inhibition, there was no correlation in SS between UTP and UNaV, FeNa or Na+/K+ ratio during the baseline or salt loading periods, analyzed separately or together. Moreover, only one UTP datapoint of SS (during salt-loading) slightly exceeded the maximum UTP excretion during salt depletion.

In neither SR or SS was there any correlation between plasma epoxyeicosatrienoic acid fractions and urine sodium excretion or Na+/K+ ratio (not shown).

Briefly, data suggest that UTP of SR reflects a renal pool involved in regulation of Na+ excretion in normal humans. The correlation between 14–15 UTP and inhibition of ENaC indicates that even after conversion to the diols in our samples, their measurement reflects the activity of this putative renal pool. In contrast, the restricted correlations in SS between UTP and either natriuresis or Na+/K+ ratio suggest abnormalities in EET-dependent natriuresis and ENaC inhibition in SS normotension.

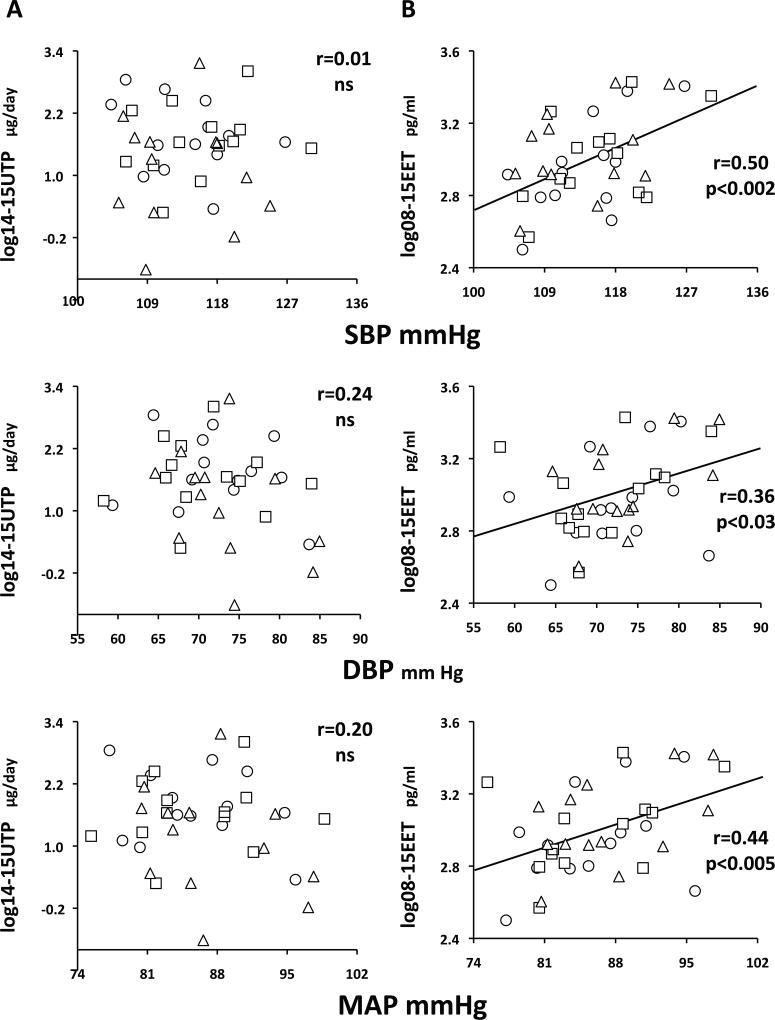

Plasma EETs correlate with arterial pressure in SR but not SS subjects

In SS, there were no significant correlations between urine or plasma epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (PTP, EET or DHET) and blood pressures (Table S2).

In SR, this was also true for urine epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (Figure 3A). In contrast, there were significant correlations between arterial pressures and 08–15 EETs (Figure 3B). These were not observed for DHETs (supplemental Fig S1B) but carried over to 08–15 PTPs (supplemental Fig S1A). Analogous observations were present for all regioisomers (Table S2).

Figure 3.

In SR, no correlations between 14–15 UTP (panels A) and systolic (SBP), diastolic (DBP) or mean arterial pressures (MAP), but significant correlations between 08–15 EET (panels B), and all blood pressures over the three days of the experiment. Symbols for each day as in Figure 1. Pearson’s r coefficients and their statistical significance are given on the graphs. ns, not significant.

Further, correlations between 08–15 EET and arterial pressure were present for the three days analyzed together and also for the two days with relatively high salt intake (Base and HiNa combined; r=0.40 p<0.05) and for the two days with a widely different range of sodium intake (HiNa and LoNa combined; r=0.46 p<0.02).

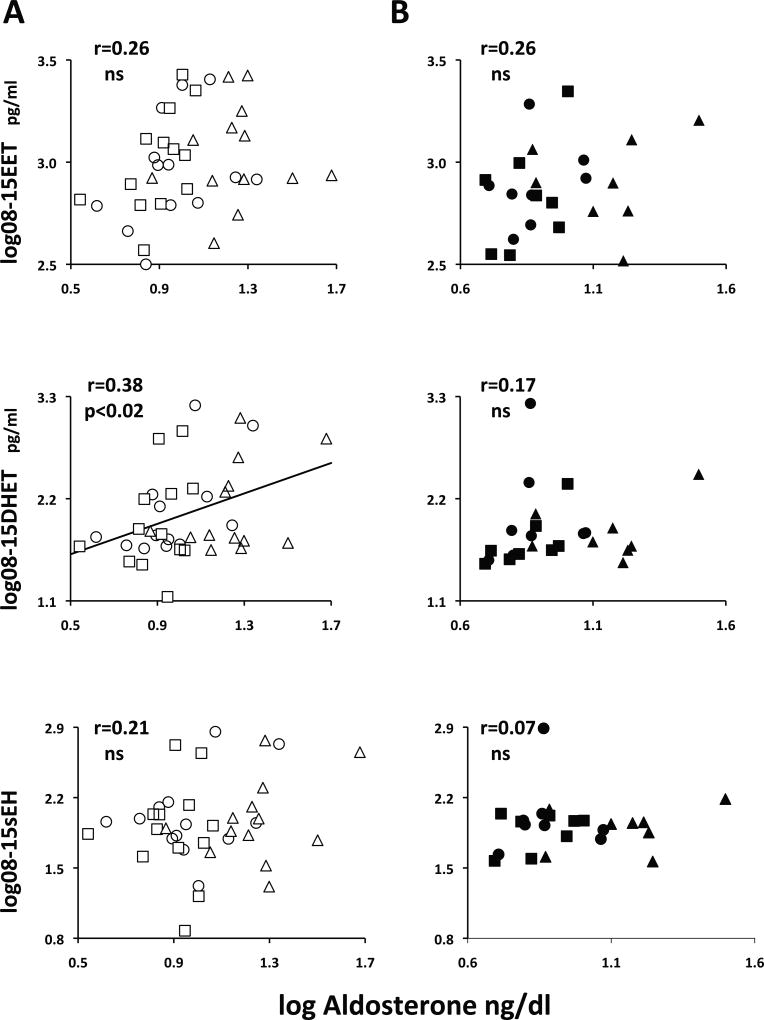

Plasma DHETs correlate with plasma aldosterone in SR but not SS subjects

Baseline plasma aldosterone was slightly but not significantly lower in SS than in SR (Table 1). Its suppression by salt was blunted in the former group (Δlog HiNa-Lona: SS −0.03±0.04, ns vs SR −0.07±0.04, p<0.04) as described previously, whereas its stimulation by salt depletion was similar in both groups (SS 0.30±0.06 vs SR 0.35±0.05).

In SR, there was a significant correlation between aldosterone and 08–15 PTP (r=0.39, p<0.02), entirely attributable to 08–15 DHETs, not 08–15 EETs, and not due to a correlation between aldosterone and 08–15 sEH activity (Figure 4A). The correlation aldosterone/DHET was also significant for the 11–12 and 14–15 plasma regioisomers in all days or in the Base+Hi and HI+Lo days but was not present for UTP (Table S3).

Figure 4.

In SR, a correlation between 08–15 DHET and plasma aldosterone (panel A, middle) not present for EET (top) or sEH (bottom). No correlations present in SS (panels B). Symbols for SR and SS subjects and for each day as in Figure 1. Pearson’s r coefficients and their statistical significance are given on the graphs. ns, not significant.

In contrast, in SS there was no correlation between any urine or plasma epoxyeicosatrienoic acid fraction and aldosterone (Figure 4B and Table S3).

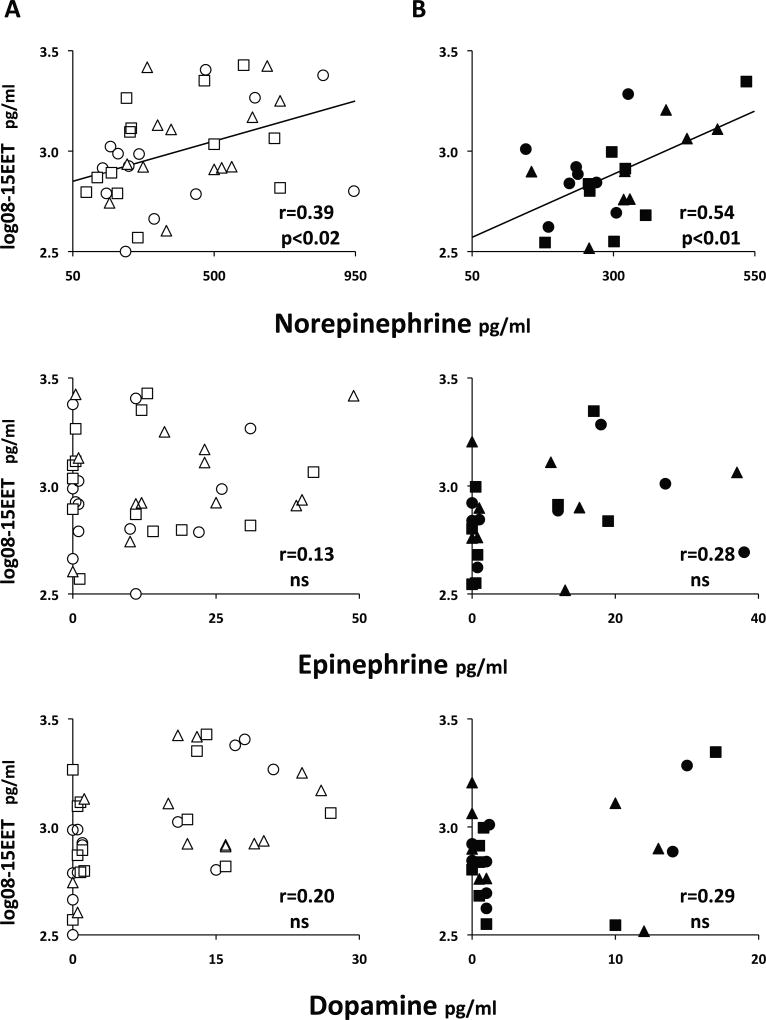

Plasma EETs correlate with with plasma catecholamines in both SR and SS subjects

Baseline plasma catecholamines of SR and SS (346±50 pg/ml) did not change after the salt load (348±42, ns) but were stimulated by salt depletion (418±36, p<0.03).

In both SR and SS, there was a correlation between plasma norepinephrine and 08–15 EET, not present for epinephrine or dopamine (Figure 5). It was highly significant for both groups together (r=0.43, p<0.001) and reflected in a correlation between total catecholamines and 08–15 EETs (r=0.45, p<0.0005).

Figure 5.

Significant correlations between 08–15 EET and plasma norepinephrine, but not epinephrine or dopamine, in SR (panels A) and SS (panels B) subjects. Symbols for SR and SS and for the three days of the experiment are as in Figure 1. Zero values (below the limit of detection) are arbitrarily spread around zero for better visualization. Pearson’s r coefficients and their statistical significance are given on the graphs. ns=not significant.

Also, there was no correlation between norepinephrine and 08–15 DHET in either group, but the effect of EET carried over to a significant one with 08–15 PTP (supplemental Figure S2), This figure also shows that there was no correlation between UTP and catecholamines in either group.

The correlations EET-norepinephrine and their lack thereof for DHETs were consistent for all regioisomers. They were present over the three days and also over the two days of high salt intake (Base+Hi) with narrow variance of catecholamines and over the days of salt loading and depletion (Hi+Lo), with wide variance of catecholamines (Table S4).

DISCUSSION

Our two major observations are: First, in normal (SR) volunteers, responses of urine and plasma epoxyeicosatrienoic acids to changes of salt balance are of opposite direction, and their clinical and biochemical correlates are different. This supports our hypothesis that they reflect two different pools (renal tubular vs systemic), perhaps synthesized independently and with different functions. Second, SS subjects have diminished urine and plasma levels of these eicosanoids compared to SR; with paradoxical or absent responses to changes in salt balance. Also correlations between their urine levels, natriuresis and ENaC function are restricted to very low levels of Na+ excretion. Finally, relationships between plasma levels and vasoactive substances identified in SR are lacking in SS. All these findings suggest involvement of abnormalities in epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in the pathophysiology of the SS phenotype in humans, consistent with observations in rodents.

In SR, urine epoxyeicosatrienoic acids were inhibited by salt depletion, as expected for a natriuretic system. However, their excretion was not increased by salt loading (inconsistent with stimulation of renal epoxygenases by salt in rodents4,5). Because ad libitum salt intake of our subjects was 15-fold greater than that in primitive societies, it is possible that renal epoxyeicosatrienoic acids are maximally stimulated at the current level of salt consumption in Western societies.

Our observations that urine (not plasma) epoxyeicosatrienoic acids correlate with natriuresis and inhibition of ENaC in normal humans are novel but expected in view of the natriuretic role for renal EETs in rodents. Evidence includes: a) stimulation of renal epoxygenases by salt4,5, b) rapid decrease in open probability of collecting duct ENaC by an EET-induced, ERK1/2-catalyzed, inactivating threonine phosphorylation of its β and γ subunits7, c) slower sustained inhibition of ENaC by an EET-activating dephosphorylation of the ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-213, which induces removal of the channel from the membrane14, and d) mediation of proximal tubule dopamine-induced water and sodium excretion by EETs, demonstrated by its blunting in Cyp2c44−/− epogygenase knockout mice3.

Therefore, in normal humans, urine epoxyeicosatrienoic acids most likely reflect the activity of a renal tubular pool that regulates ENaC activity and natriuresis. Hence, research on the renal actions of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in humans must rely on their urine, not plasma measurements.

Plasma levels of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids of normal humans sustained changes opposite to those of UTP in response to changes in salt balance and exhibited different correlates compared to those of UTP. Suppression of sEH and DHET and mild stimulation of EETs by salt suggest a compensatory response to enhance vasodilation during a salt load, whereas stimulation of sEH and DHET by low salt balance may diminish vasodilation for maintenance of blood pressure during salt depletion.

Positive correlations between a vasodilator and higher BP in SR suggest that endothelial synthesis of EETs is stimulated by higher BP to exert counter-regulatory vasodilator tone. Although no such evidence has been published, this speculation is consistent with increased vasodilator tone in normotensive or hypertensive experimental models, when production of vascular EETs is enhanced by dietary means15 or by administration of EET analogs16. These observations are likely due to EET-attenuation of vascular myogenic responses in resistance arterioles, as shown in sEH knockout mice or with sEH inhibitors17.

The correlation between DHET and plasma aldosterone in SR could be due to parallel dichotomization of both parameters by changes in salt balance (inhibition by salt loading and stimulation by salt depletion). However, it was also present during the periods of small variance of aldosterone levels (baseline and high salt days). Because EET release by adrenal zona glomerulosa cells is not accompanied by aldosterone release18, this correlation is unlikely due to effects of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids on aldosterone synthase. Conversely, stimulation of expression or activity of epoxygenases or sEH by aldosterone has never been reported. Finally, we found no relationship between aldosterone and sEH and have no data to alternatively support aldosterone-induced DHET formation by oxidative stress19. The relationship might reflect a feed-forward effect of aldosterone inhibiting its counter-regulatory system to enhance extrarenal effects on ENaC but we have not data in this regard. Therefore, the physiological significance of this relationship remains to be investigated.

Plasma EETs and catecholamines were also affected by salt balance in parallel manner (no change with salt-loading and stimulation by salt-depletion). However, their correlations were present for the periods of narrow (baseline and high salt) and large (high salt and low salt) variances in plasma catecholamines. They were present in both SR and SS and highly significant in all subjects together. Previously reported relationships between epoxyeicosatrienoic acids and the autonomic nervous system include: a) release of catecholamines by chromaffin cells in response to arachidonic acid mediated by endogenous 5–6 EET, which can be blocked by CYP450 inhibitors and restored by exogenous 5–6 EET20; b) coexpression of epoxygenases and sEH in brain parasympathetic perivascular nerves21; and c) production of EETs by sympathetic superior cervical ganglia neurons in culture22. Mechanisms for these interactions have not been elucidated and there is no evidence for either catecholamine-stimulation of epoxygenases or for EET-induced norepinephrine release from sympathetic terminals in whole animals or humans. Reciprocal stimulation of these vasodilator and vasoconstrictor systems suggests a regulatory interaction for maintenance of normal vascular tone and blood pressure or for systemic non-cardiovascular effects of the autonomic nervous system, but these are speculations.

SSBP is a common phenotype of normotensive and hypertensive subject by which blood pressure varies in parallel to salt intake. It confers increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality compared to SR23,24. Although a cardiovascular risk factor, it has no specific treatment because its mechanisms are not completely understood. A deficit in the production or actions of the natriuretic or vasodilator epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, or in both, could participate in the pathophysiology of the SS phenotype via renal or vascular dysfunction, its two putative major mechanisms25,26.

SS had lower levels of 14–15 UTP compared with SR over the three days of the study, reaching significance at baseline, despite their UNaV being 40 mmol/day greater than that of SR. Further, baseline levels were not different than those observed after profound salt-depletion, and although stimulated by salt they did not reach the baseline levels of SR (Figure 1, panel A). Interpretations include: First, SS may have a defect upstream of renal epoxygenase expression (e.g., salt sensing), but this is not supported by the correlation between UTP and natriuresis at low levels of Na+ excretion. Second, they may have defective renal expression of epoxygenases. This is supported by our results, those of a dietary experiment, in which SS had diminished urine EETs during the low salt phase27, and by reduced renal expression of epoxygenases and urine excretion of EETs in Dahl-S rats5. Third, a defect may be downstream of the epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, impairing signaling to renal sodium transporters. This would be analogous to our description of lack of natriuretic effect for normal urine 20-HETE in SS hypertension9 and strongly supported by the observation that excretion of UTP per unit UNaV was markedly increased in SS compared to SR.

Plasma EETs were significantly lower over the three phases of the study in SS than in SR, most strikingly after the salt load (Figure 1, panel B). In the dietary study mentioned above SS also had lower plasma EET than SR, albeit during the low-salt period27. Rather than a flat pattern with changes in salt intake (as their UTP exhibited), SS had decreased plasma sEH and DHETs with salt loading and increased EETs and DHETs with salt depletion, again analogous to the dietary study27. These responses are not consistent with those of a natriuretic system. Finally, equal to SR, no plasma epoxyeicosatrienoic acid fraction of SS correlated with natriuresis or inhibition of ENaC. Therefore, it is extremely unlikely that diminished plasma epoxyeicosatrienoic acids of SS contribute to the SS phenotype via renal tubular (i.e., natriuresis) abnormalities.

Our data are consistent with evidence that plasma epoxyeicosatrienoic acids belong in a systemic, i.e., non-renal tubular compartment1,2. Changes in plasma sEH, DHETs and EETs and correlations with norepinephrine in SS suggest involvement in compensatory vasodilation. This is surprising because the major hemodynamic abnormality of SS is an inability to vasodilate in response to salt loading12. However, these changes took place at lower levels of plasma epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in SS than SR, which may explain this apparent contradiction. Lack of correlation between plasma EETs of SS and blood pressure, present in normal SR subjects, supports dysregulated vasodilation by EETs in SS.

Weaknesses of our study include: 1. Power calculations were made for the previously reported hemodynamic studies in the same subjects12, not specifically for the current one; therefore, we may have been underpowered to show more dramatic differences in levels between SR and SS, many of which were of borderline significance when analyzed for single day lower n’s. However, despite this, we documented a very different set of correlates for urine and plasma measurements, i.e., the small n’s did not preclude detection of significant relationships. 2. Inability to detect active EETs in urine samples, different from other studies1,27,28, was most likely due to non-enzymatic conversion to DHETs during prolonged storage. The relative proportion of EETs and DHETs at collection must have been different in each patient and this unknown variance should have weakened our statistical analyses. Therefore, the detectable and strong correlation between UTP and Na+/K+ ratio, a marker of ENaC inhibition, makes us very confident that measuring the total pool of urine epoxyeicosatrienoic acids as converted relatively inactive diols did nonetheless reflect the activity of this pool at the time the samples were obtained. 3. The only available ELISA for urine DHET measures the 14–15 regioisomer, whereas our plasma methods measured the 8–9, 11–12 and 14–15 regioisomers. Although results with the plasma regioisomers were indistinguishable from those of the sum of the three regioisomers, we could not ascertain whether this was true in our urine samples. 4. Our conclusions are derived in part from correlations, which do not imply causality and should be considered hypothesis-generating, to be tested by pharmacological intervention.

Overall, our studies show different regulation by salt and different clinical and biochemical correlates for urine and plasma epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in humans. They suggest that urine data reflect a renal tubular pool involved in regulation of natriuresis, whereas plasma data reflect a systemic pool unrelated to salt excretion, most likely participating in regulation of vasodilation, maintenance of normal blood pressure or perhaps non-cardiovascular effects that we have not investigated. Additionally, we describe differences between SS and SR subjects that support participation of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in the renal or vascular pathophysiology of the SS phenotype, consistent with beneficial effects of EET analogs and sEH antagonist observed in experimental models of SS hypertension29,30.

PERSPECTIVES

Two broad implications are derived from our studies. First, research on the renal physiology of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in humans, in the absence of tissue samples, must rely on measurements of urine epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, whereas in contrast, research on the multiple systemic actions of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (cardiovascular or otherwise) must rely on plasma measurements. Second, our data encourage investigation of potential use of EET analogs and sEH antagonist (both in development) in the SS phenotype of normotensive or hypertensive subjects, a cardiovascular risk factor which currently has no specific therapy.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is New?

Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, a class of lipids that regulate salt excretion and blood pressure, are partitioned in two different pools (renal and non-renal) in humans, as previously suggested by research in rodents.

Salt-sensitive subjects in this study exhibited alterations in the levels and correlates of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids compared with salt-resistant subjects, which suggests that abnormalities in these lipids may participate in the causation of salt sensitivity of blood pressure, a characteristic known to be a risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

What Is Relevant?

Demonstration of partitioning of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids into different compartments in humans is of practical importance for the design of future clinical research on the renal and non-renal functions of these compounds.

Demonstration of abnormalities of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in the salt sensitive phenotype has therapeutic implications because there are pharmaceutical agents in development that may potentially correct them, so reducing the cardiovascular risk of SS subjects with normal or high blood pressure

Summary.

This study contributes to the body of knowledge supporting a role for epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in the normal physiology of salt metabolism and blood pressure regulation and in the pathophysiology of the salt-sensitive phenotype of humans, a cardiovascular risk factor without current specific treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Shouzou Wei at Vanderbilt University and Katherine Gottlinger at New York Medical College for their expertise and invaluable help in the measurement of the eicosanoids reported in this work.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by grants from the Scott, Sherwood, and Brindley Foundation (to CLL) and from the National Institutes of Health (HL034300 to MLS and DK038226 to NJB).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

None

References

- 1.Catella F, Lawson JA, Fitzgerald DJ, FitzGerald GA. Endogenous biosynthesis of arachidonic acid epoxides in humans: increased formation in pregnancy-induced hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5893–5897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pozzi A, Ibanez MR, Gatica AE, Yang S, Wei S, Mei S, Falck JR, Capdevila JH. Peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor-alpha-dependent inhibition of endothelial cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:17685–17695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang MZ, Wang Y, Yao B, Gewin L, Wei S, Capdevila JH, Harris RC. Role of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) in mediation of dopamine's effects in the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;305:F1680–F1686. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00409.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capdevila JH, Wei S, Yan J, Karara A, Jacobson HR, Falck JR, Guengerich FP, DuBois RN. Cytochrome P-450 arachidonic acid epoxygenase. Regulatory control of the renal epoxygenase by dietary salt loading. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21720–21726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Makita K, Takahashi K, Karara A, Jacobson HR, Falck JR, Capdevila JH. Experimental and/or genetically controlled alterations of the renal microsomal cytochrome P450 epoxygenase induce hypertension in rats fed a high salt diet. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2414–2420. doi: 10.1172/JCI117608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capdevila JH, Pidkovka N, Mei S, Gong Y, Falck JR, Imig JD, Harris RC, Wang W. The Cyp2c44 epoxygenase regulates epithelial sodium channel activity and the blood pressure responses to increased dietary salt. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:4377–4386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.508416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakagawa K, Holla VR, Wei Y, Wang WH, Gatica A, Wei S, Mei S, Miller CM, Cha DR, Price E, Jr, Zent R, Pozzi A, Breyer MD, Guan Y, Falck JR, Waterman MR, Capdevila JH. Salt-sensitive hypertension is associated with dysfunctional Cyp4a10 gene and kidney epithelial sodium channel. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1696–1702. doi: 10.1172/JCI27546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grim CE, Weinberger MH, Higgins JT, Kramer NJ. Diagnosis of secondary forms of hypertension. A comprehensive protocol. JAMA. 1977;237:1331–1335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laffer CL, Laniado-Schwartzman M, Wang MH, Nasjletti A, Elijovich F. Differential regulation of natriuresis by 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid in human salt-sensitive versus salt-resistant hypertension. Circulation. 2003;107:574–578. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000046269.52392.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy JC, Matthews DR, Hermans MP. Correct homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) evaluation uses the computer program. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:2191–2192. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.12.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Capdevila JH, Dishman E, Karara A, Falck JR. Cytochrome P450 arachidonic acid epoxygenase: stereochemical characterization of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Methods in enzymology. 1991;206:441–453. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)06113-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laffer CL, Scott RC, III, Titze JM, Luft FC, Elijovich F. Hemodynamics and salt-and-water balance link sodium storage and vascular dysfunction in salt-sensitive subjects. Hypertension. 2016;68:195–203. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ismail NA, Baines DL, Wilson SM. The phosphorylation of endogenous Nedd4-2 In Na(+)-absorbing human airway epithelial cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;732:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pavlov TS, Ilatovskaya DV, Levchenko V, Mattson DL, Roman RJ, Staruschenko A. Effects of cytochrome P-450 metabolites of arachidonic acid on the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;301:F672–F681. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00597.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charles RL, Rudyk O, Prysyazhna O, Kamynina A, Yang J, Morisseau C, Hammock BD, Freeman BA, Eaton P. Protection from hypertension in mice by the Mediterranean diet is mediated by nitro fatty acid inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:8167–8172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402965111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hye Khan MA, Pavlov TS, Christain SV, Neckar J, Staruschenko A, Gauthier KM, Capdevila JH, Falck JR, Campbell WB, Imig JD. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acid analogue lowers blood pressure through vasodilation and sodium channel inhibition. Clin Sci. 2014;127:463–474. doi: 10.1042/CS20130479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun D, Cuevas AJ, Gotlinger K, Hwang SH, Hammock BD, Schwartzman ML, Huang A. Soluble epoxide hydrolase-dependent regulation of myogenic response and blood pressure. Am J Physiol Heart & Circulatory Physiol. 2014;306:H1146–H1153. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00920.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kopf PG, Gauthier KM, Zhang DX, Falck JR, Campbell WB. Angiotensin II regulates adrenal vascular tone through zona glomerulosa cell–derived EETs and DHETs. Hypertension. 2011;57:323–329. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.158311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Briet M, Schiffrin EL. Vascular actions of aldosterone. J Vasc Res. 2013;50:89–99. doi: 10.1159/000345243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hildebrandt E, Albanesi JP, Falck JR, Campbell WB. Regulation of calcium influx and catecholamine secretion in chromaffin cells by a cytochrome P450 metabolite of arachidonic acid. J Lipid Res. 1995;36:2599–2608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iliff JJ, Close LN, Selden NR, Alkayed NJ. A novel role for P450 eicosanoids in the neurogenic control of cerebral blood flow in the rat. Exp Physiol. 2007;92:653–658. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2006/036889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdu E, Bruun DA, Yang D, Yang J, Inceoglu B, Hammock BD, Alkayed NJ, Lein PJ. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids enhance axonal growth in primary sensory and cortical neuronal cell cultures. J Neurochem. 2011;117:632–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07139.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morimoto A, Uzu T, Fujii T, Nishimura M, Kuroda S, Nakamura S, Inenaga T, Kimura G. Sodium sensitivity and cardiovascular events in patients with essential hypertension. Lancet. 1997;350:1734–1737. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)05189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weinberger MH, Fineberg NS, Fineberg SE, Weinberger M. Salt sensitivity, pulse pressure, and death in normal and hypertensive humans. Hypertension. 2001;37(pt 2):429–432. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris RC, Jr, Schmidlin O, Sebastian A, Tanaka M, Kurtz TW. How does high salt intake cause hypertension? Vasodysfunction that involves renal vasodysfunction, not abnormally increased renal retention of sodium, accounts for the initiation of salt-induced hypertension. Circulation. 2016;133:881–893. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall JE. How does high salt intake cause hypertension? Renal dysfunction, rather than nonrenal vasculardysfunction, mediates salt-induced hypertension. Circulation. 2016;133:894–907. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilbert K, Nian H, Yu C, Luther JM, Brown NJ. Fenofibrate lowers blood pressure in salt-sensitive but not salt-resistant hypertension. J Hypertens. 2013;31:820–829. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835e8227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toto R, Siddhanta A, Manna S, Pramanik B, Falck JR, Capdevila J. Arachidonic acid epoxygenase: detection of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in human urine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;919:132–139. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(87)90199-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li J, Carroll MA, Chander PN, Falck JR, Sangras B, Stier CT. Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitor, AUDA, prevents early salt-sensitive hypertension. Front Biosci. 2008;13:3480–3487. doi: 10.2741/2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imig JD, Zhao X, Zaharis CZ, Olearczyk JJ, Pollock DM, Newman JW, Kim IH, Watanabe T, Hammock BD. An orally active epoxide hydrolase inhibitor lowers blood pressure and provides renal protection in salt-sensitive hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;46:975–981. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000176237.74820.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.