Abstract

Brachiopod shells are the most widely used geological archive for the reconstruction of the temperature and the oxygen isotope composition of Phanerozoic seawater. However, it is not conclusive whether brachiopods precipitate their shells in thermodynamic equilibrium. In this study, we investigated the potential impact of kinetic controls on the isotope composition of modern brachiopods by measuring the oxygen and clumped isotope compositions of their shells. Our results show that clumped and oxygen isotope compositions depart from thermodynamic equilibrium due to growth rate-induced kinetic effects. These departures are in line with incomplete hydration and hydroxylation of dissolved CO2. These findings imply that the determination of taxon-specific growth rates alongside clumped and bulk oxygen isotope analyses is essential to ensure accurate estimates of past ocean temperatures and seawater oxygen isotope compositions from brachiopods.

Introduction

Biomineralising marine organisms serve as important geochemical archives of past climate conditions. Brachiopods constitute one group of calcifying invertebrates that have great potential for palaeoenvironmental reconstructions due to their common occurrences in Phanerozoic sediments since the Cambrian1. Their high abundance in Palaeozoic sediments makes them particularly valuable for deep-time seawater temperature reconstructions based on shell oxygen isotope compositions2. Unlike many other biogenic archives fossil and modern brachiopods can be found from tropical to polar environments and from a great range of water depths1,3.

A limitation of the conventional oxygen isotope palaeothermometer method is that it requires an assumption for the oxygen isotope composition of the palaeo-seawater4. The common assumption that the seawater δ18OVSMOW values remained constantly between −1‰ and 0‰ during the Phanerozoic leads to relatively low apparent oxygen isotope fractionation between ancient seawater and brachiopod calcite, and hence to unrealistically high seawater temperature estimates2. Alternatively, it has been claimed that the progressive 18O depletion of brachiopod shells with age during the Phanerozoic reflects increasing post-depositional alteration or a secular decline in seawater δ18O values of about −6‰ compared to the modern ocean2. To investigate the underlying cause of presumably erroneous extremely warm Phanerozoic temperature estimates, independent constraints on past seawater temperatures and δ18O values are needed.

In contrast to oxygen isotope thermometry, the carbonate clumped isotope thermometer does not require an estimate for the oxygen isotope composition of the seawater, as it considers the fractionation of isotopes exclusively amongst carbonate isotopologues5. In thermodynamic equilibrium, the clumped isotope composition (∆47) of a given carbonate is solely a function of the carbonate precipitation temperature. Fossil brachiopod shells have been analysed both for both their oxygen and clumped isotope composition to independently constrain ocean temperatures and seawater δ18O6–8. However, previous investigations into the temperature dependence of the clumped isotope composition of modern brachiopod shells have reported inconsistent results. Came et al.9 reported a significantly steeper ∆47–temperature slope compared to the theoretical calibration10 and to the empirical calibration based on brachiopods and molluscs11. Came et al.9 exclusively investigated brachiopods, whereas the calibration of Henkes et al.11 was primarily based on molluscs. Differences in phosphoric acid digestion temperatures (90 °C vs. 25 °C) were suggested as a possible explanation for the discrepant ∆47–temperature slopes9. However, it remains an open question whether kinetic fractionation processes may account for the observed discrepancies in the ∆47–temperature slopes.

Kinetic isotope fractionations driven by diffusion, pH or incomplete oxygen isotope exchange between water and dissolved inorganic carbonate species can cause calcite to be precipitated with isotope values that are offset from those predicted for thermodynamic equilibrium12–14. Kinetic fractionation effects have been recognised in other important calcifying groups, including in warm and cold-water corals and in certain foraminifera species12,14–16. It has been postulated that brachiopods incorporate oxygen isotopes into shell calcite (secondary and tertiary layers) in equilibrium with ambient seawater, although certain parts of the shell (i.e., primary layer, uppermost part of the secondary layer, umbo and muscle scar areas) yield depleted δ18O values17–21. In these shell areas, the observed 18O-depletion has been linked to growth-rate-driven kinetic isotope fractionation18,22–26.

Here, we investigate the significance of kinetic controls (also called vital effects) on brachiopod shell ∆47 and δ18O values. We analysed the bulk and clumped isotope compositions of eighteen modern brachiopod shells at a phosphoric acid digestion temperature of 90 °C. The studied specimens represent fourteen species collected from different geographic locations and water depths that cover a substantial range of growth temperatures (Supplementary Table 1). Growth temperatures and seawater δ18O values for each brachiopod were independently-determined and we complemented our measurements with trace element and ion probe-based in situ oxygen isotope analyses.

Results

Trace element analyses

The magnesium concentration of the studied modern brachiopod shells was between 0.27 mol% (Terebratalia transversa) and 6.8 mol% (Pajaudina atlantica) MgCO3. Our results are consistent with the expected range of modern brachiopod calcite and fall along the Global Brachiopod Mg Line20 (Supplementary Fig. 1a).

Bulk and clumped isotope analyses

The δ18OVPDB values of the modern brachiopod shells analysed in this study range between −2.20(±0.02)‰ and 3.92(±0.02)‰, while the δ13CVPDB values range between −0.88(±0.02)‰ and 2.44(±0.01)‰. These values are consistent with the range in isotope compositions of modern brachiopod shells (secondary and tertiary layers) reported elsewhere20,21,25,27. The difference between the oxygen and carbon isotope composition of the shells determined using the [Gonfiantini] and the [Brand] sets of isotopic parameters28 is ~0.01‰. This is similar or less than the 1σ S.E. of replicate measurements and can therefore be ignored (see Methods).

The ∆47(CDES 25) values measured for the modern brachiopods shells calculated with the [Gonfiantini] parameters range between 0.671(±0.007)‰ and 0.775 (±0.004)‰, while the 1σ S.E., calculated from 4–10 replicate analyses, ranges between 0.004–0.014‰. The ∆47(CDES 25) values for the brachiopods calculated with the [Brand] parameters are between 0.664(±0.007)‰ and 0.767(±0.004)‰, while the 1σ S.E., calculated from 4–10 replicate analyses, ranges between 0.004–0.013‰. The difference between ∆47(CDES 25) values calculated with the [Gonfiantini] and the [Brand] sets of isotopic parameters is between 0.005‰ and 0.008‰.

Apparent ∆47–temperature relationship

To obtain a ∆47–temperature relationship for modern brachiopod calcite, a least-squares fit linear regression29,30 was performed on the measured ∆47(CDES 25) values and the independently-sourced brachiopod growth temperatures31 (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). This approach considered uncertainties arising from both the clumped isotope measurements and the growth temperatures. The statistical analyses yielded the following ∆47–temperature relationship (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 2a):

| 1 |

| 2 |

where ∆47 is in ‰, T (temperature) is in K and the two-tailed p-values are calculated using a t-test.

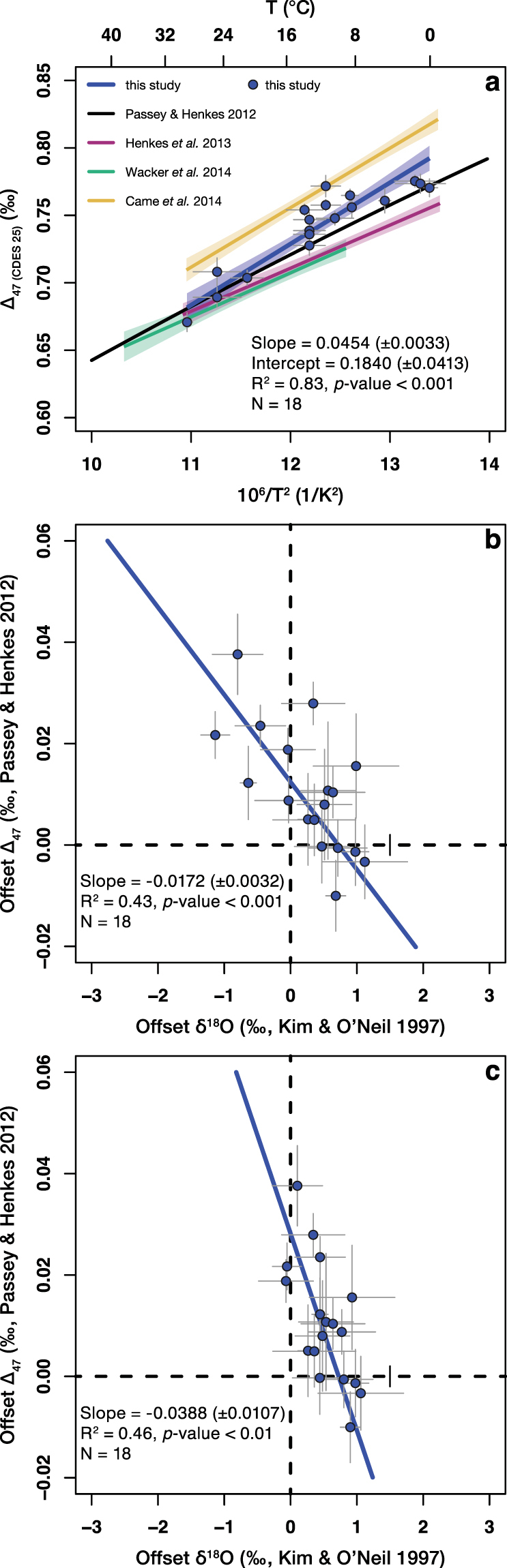

Figure 1.

Brachiopods show an offset from equilibrium ∆47 and δ18O values. (a) ∆47–temperature dependence derived from the eighteen modern brachiopods analysed in this study, calculated using the [Gonfiantini] set of isotopic parameters. (b) The offset δ18O and offset ∆47 values show a significant negative correlation. The brachiopods, which show apparent clumped isotope equilibrium are enriched by up to +1‰, relative to Kim and O’Neil35. Seawater δ18O values were acquired from the Global Seawater Oxygen-18 Database34. (c) The correlation between offset δ18O and offset ∆47 values is still present if, where available, the directly measured seawater δ18O values (Supplementary Table 1) were used for the calculations. For all plots: linear regression lines fitted to our data consider the errors. Corresponding two-tailed p-values are computed using a t-test. Error bars for the offset δ18O values indicate the mean deviation from oxygen isotope equilibrium calculated using the minimum and the maximum temperature estimates. Error bars for the offset ∆47 values indicate the 1σ S.E. of the replicate measurements.

The slope of our ∆47–temperature calibration line (eqs 1 and 2) is steeper compared to the theoretical calibration10 and to previous calibrations made at > 70 °C11,29,32, and shallower than most 25 °C calibrations33. However, the slope of our ∆47–temperature calibration line is indistinguishable from the brachiopod-only calibration of Came et al.9, made at 25 °C.

∆47 and δ18O offsets from apparent equilibrium

The difference between the measured and apparent equilibrium values are here referred to as offset values (Supplementary Data 2). Annual mean habitat temperatures (i.e., brachiopod growth temperatures) were acquired from the World Ocean Atlas 201331. Annual mean seawater δ18O values representative of the sampling location and depth were taken from the Global Seawater Oxygen-18 Database34. For thirteen out of eighteen specimens, directly measured seawater δ18O values were also available, giving actual seawater oxygen isotope compositions at the water depth where the brachiopods were collected20 (Supplementary Table 1). To remain consistent, we distinguish between the two datasets: one using only the seawater δ18O values acquired from the Global Seawater Oxygen-18 Database34 and the other in which gridded δ18O values were replaced by the directly measured δ18O values where available.

Apparent δ18Ocalcite equilibrium values were calculated using the 1000lnαcalcite–water–temperature relationship of Kim and O’Neil35 (see Supplementary Information) and that of Brand et al.20, respectively. The latter includes a correction for the Mg-effect, which accounts for a 0.17‰ change per mol% MgCO3 in the δ18O values of the calcite, in agreement with laboratory precipitation experiments20. Apparent ∆47 equilibrium values were calculated using the theoretical calibration of Passey and Henkes10, i.e., their eq. 5, with the empirically determined intercept of 0.280 (Fig. 1b,c and Supplementary Fig. 2). This equation considers a 25–90 °C acid fractionation factor of 0.081‰ and has been verified in the 0–40 °C temperature range by empirical and experimental approaches11,29,36,37. In addition, offset ∆47 values were also calculated assuming that the most recent calibrations of Bonifacie et al.32 or Kelson et al.38 represent the clumped isotope equilibrium (Supplementary Fig. 3). Offset ∆47 values were computed using both the [Gonfiantini] and the [Brand] processed data.

Most of the analysed brachiopods in this study exhibit combined offsets from clumped and oxygen isotope equilibrium, irrespective how the offset values were calculated (Fig. 1b,c and Supplementary Figs 2b,c and 3). The largest deviations from the equilibrium ∆47 values were observed in the temperate- to cold-water brachiopod species, particularly those of the species Magellania venosa and Magasella sanguinea. In contrast, most of the warm-water (>20 °C) taxa, such as Thecidellina congregata, Argyrotheca sp., Megerlia sp., and P. atlantica, exhibit apparent clumped isotope equilibrium.

Oxygen isotope analyses with ion probe

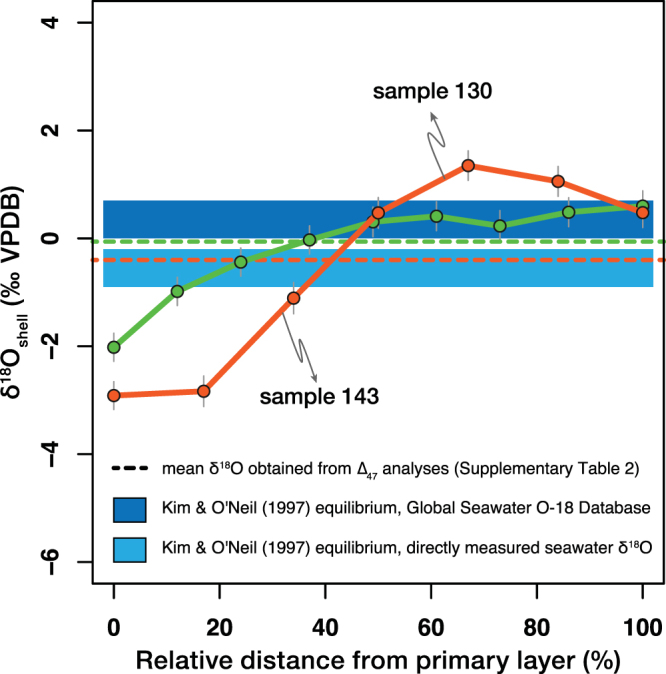

High resolution (20 μm) in situ oxygen isotope analysis was performed on two M. venosa shells using SIMS (Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry). In the secondary layer of the two investigated M. venosa shells, the δ18O values range from −2.91‰ to 1.35‰ (sample 130) and from −2.02‰ to 0.60‰ (sample 143; Fig. 2). This species does not have a tertiary layer and the primary layer was too thin to be analysed (Supplementary Fig. 6). The variation in δ18O between the outer and inner part of the shell was 4.3‰ for sample 130 and 2.6‰ for sample 143 (Supplementary Data 3, Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Variations in δ18O between the outer and the inner part of the secondary layer. Results of the SIMS transects made on two M. venosa shells (samples 130 and 143) also analysed for clumped isotopes. Apparent equilibrium ranges for δ18O were calculated according to Kim and O’Neil35 using the minimum and maximum habitat temperature estimates and the two sets of seawater δ18O values (see main text and Supplementary Table 1). Error bars for the δ18O indicate the external reproducibility (1σ S.D.) based on replicate measurements of carbonate standards.

Discussion

Multiple processes can lead to the deviation of measured δ18O and ∆47 values from thermodynamic equilibrium. If the offset seen in the modern brachiopod δ18O values would arise solely from the varying Mg-content of the analysed shells, one would expect that this offset would disappear if the equilibrium values were calculated using the equation of Brand et al.20 instead of Kim and O’Neil35, since the former includes a correction for the Mg-effect. However, the scatter of the brachiopod δ18O values around the assumed oxygen isotope equilibrium is even greater if the Brand et al.20 equation is used, thus the offset δ18O values cannot be explained by the Mg-content of the shells (compare Fig. 1b,c to Supplementary Figs. 1b,c). We also exclude a direct effect of the Mg-content of the shells on the ∆47 values, considering the recent findings of Bonifacie et al.32 who, for a given precipitation temperature, did not find any difference in the clumped isotope composition between dolomite and calcite reacted at 90 °C.

A mixture of carbonates of different compositions will mix linearly with respect to δ13C and δ18O but non-linearly with respect to ∆47. The resulting mixture can, therefore, have a greater or lower ∆47 value than the weighted sum of the end-member ∆47 values, introducing an artificial bias in ∆4739,40. The range of variation in δ18O and δ13C in modern brachiopod shells is usually not larger than 6‰, considering both the variation within secondary layer calcite19,21–24,41 and between the juvenile and the adult parts of the shell21,22,24–27,41–43. Assuming the most-extreme scenario of 50–50% mixing of carbonates precipitated at the same temperature with a 6‰ difference in both their δ13C and δ18O values, the maximum effect of carbonate mixing on ∆47 in modern brachiopods would be +0.009‰40. To further investigate the role of sample heterogeneity on our data, we assessed the range of variation in δ18O values in two M. venosa shells that exhibited a high (0.024‰ and 0.038‰, respectively) ∆47 offset with respect to Passey and Henkes10. Our data show that the difference in δ18O values in brachiopod secondary layer calcite can be as high as 4.3‰ between the outer and the inner part of the shell (Fig. 2). A covariance of δ18O and δ13C along the depth transects of modern brachiopods shells suggests that the range of variation in δ13C will be comparable to that of δ18O22–24,41,43. A 50–50% mixing of carbonates precipitated at the same temperature with a 4.3‰ difference in both their δ13C and δ18O values results in a ∆47 mixing effect of +0.005‰40. This bias is much smaller than the observed maximum offset ∆47 value of 0.038‰ and unresolvable from the external analytical precision (1σ S.E.) received for most replicates. Thus, it is highly unlikely that a mixing of carbonates of different compositions through the shell significantly contributes to the positive ∆47 offsets observed in this study.

Differences in laboratory procedures, such as reaction temperatures, have previously been suggested as a possible explanation for the discrepancy in the slopes between the Came et al.9 calibration, made at 25 °C, and the Henkes et al.11 calibration, made at 90 °C. Although, Henkes et al.11 also analysed brachiopods (N = 4), their calibration is predominantly based on molluscs (N = 40). Since our study and that of Came et al.9 yielded the same calibration slope despite using two different acid digestion temperatures, we consider this slope gradient to be characteristic of brachiopods and exclude acid digestion temperature as a valid explanation for the difference between the lower (25 °C) and the higher (>70 °C) temperature calibration slopes.

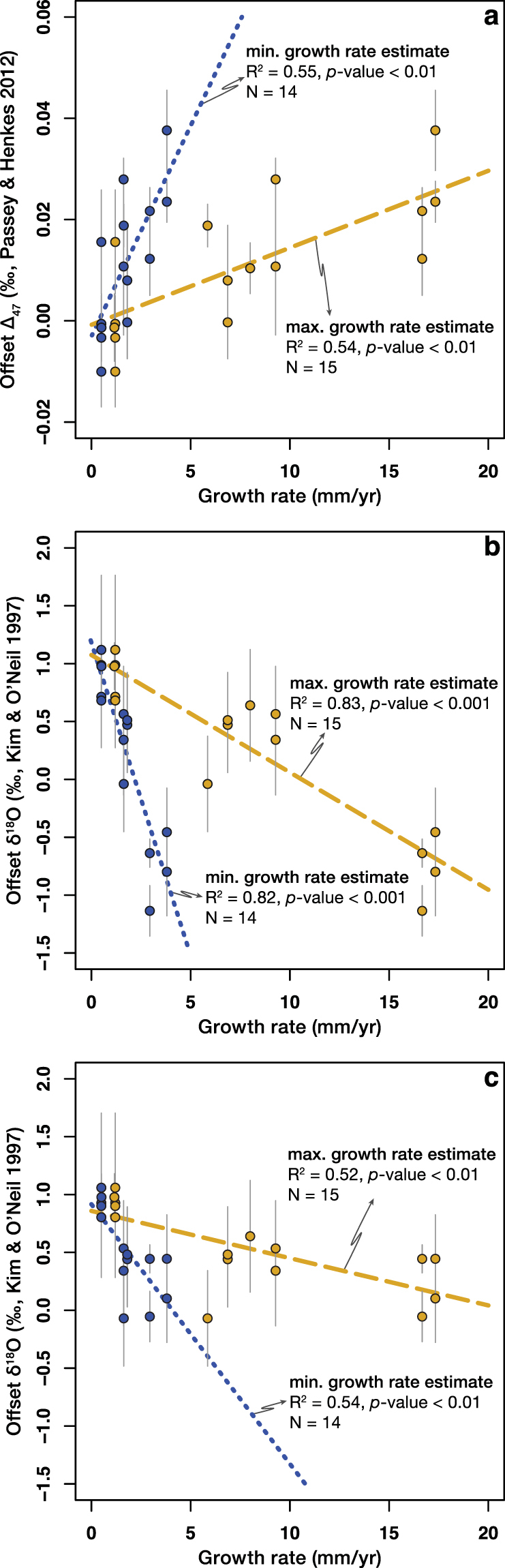

Growth rates of the modern brachiopods analysed in this study correlate well with both the offset ∆47 (R2 ≈ 0.55, p-value < 0.01; Fig. 3a) and the offset δ18O values (R2 > 0.52, p-value < 0.01; Fig. 3b,c). The slowest growing brachiopods (T. congregata, Argyrotheca sp., Megerlia sp., P. atlantica) are in apparent clumped isotope equilibrium10, whereas the fastest growing brachiopods (M. venosa, T. transversa) show a positive ∆47 offset. The offset δ18O values show a negative correlation with growth rate. A similar depletion of 18O with increasing growth rate was observed in other modern brachiopod species by Takayanagi et al.44. The slowest growing brachiopods that are closest to clumped isotope equilibrium relative to Passey and Henkes10 are enriched in 18O relative to the apparent oxygen isotope equilibrium as predicted by Kim and O’Neil35. This strongly implies that growth rate exerts control on the kinetic mechanisms responsible for the observed departures from apparent clumped and oxygen isotope equilibria.

Figure 3.

Offset ∆47 and offset δ18O values correlate with brachiopod growth rates. The dashed and dotted lines are simple linear regressions calculated using the maximum and the minimum growth rate estimates, respectively. (a) Offset ∆47 values, calculated using the [Gonfiantini] set of isotopic parameters, positively correlate with brachiopod growth rates. (b) Offset δ18O values negatively correlate with brachiopod growth rates. Seawater δ18O values were acquired from the Global Seawater Oxygen-18 Database34. (c) The correlation between offset δ18O and brachiopod growth rates is still present if, where available, the directly measured seawater δ18O values were used for the calculations. For all plots: two-tailed p-values are calculated using a t-test. Error bars for the offset δ18O values indicate the mean deviation from oxygen isotope equilibrium calculated using the minimum and the maximum temperature estimates. Error bars for the offset ∆47 values indicate the 1σ S.E. of the replicate measurements.

The calcite shells of articulated brachiopods are secreted in the outer epithelium of the mantle. The primary layer is formed by indirect secretion in the extrapallial fluid, while the secondary layer is formed by extracellular mineralization45,46. To aid our discussion, we consider a simplified model of calcification, introduced for molluscs and corals, but that has also been applied to brachiopods47,48 (Supplementary Fig. 4a). In this model, carbonate formation occurs in a semi-isolated volume, separated from the ambient environment by an organic membrane13,46,49. The organism requires calcium (Ca2+) and carbonate (CO32−) ions to enable the precipitation of CaCO3. In marine calcifiers, such as corals and molluscs, the organic membrane pumps Ca2+ into the calcifying fluid using an enzyme (Ca-ATPase), while increasing the pH of the fluid by removing an equivalent number of protons (2H+)13. We note that the presence of this enzyme, to the best of our knowledge, has not been reported from brachiopods to date. As the membrane is only permeable for aqueous carbon dioxide (CO2(aq)), the CO2(aq) in the mineralizing fluid is transformed into bicarbonate (HCO3−) and CO32− ions via hydration (eq. 3) and hydroxylation (eq. 4) reactions:

| 3 |

| 4 |

It has recently been demonstrated that kinetic effects related to the CO2(aq) hydration and hydroxylation reactions, as well as diffusion, can produce a positive ∆47 and a negative δ18O offset from thermodynamic equilibrium12,50,51 (Supplementary Fig. 4b).

Knudsen-diffusion predicts that a gas diffusing through a membrane will be depleted in 18O but enriched in ∆47, relative to the residual gas51. When correlating the ∆47 and δ18O offsets from equilibrium, the diffused and residual gas fractions would plot along a slope of −0.023. An identical slope would be obtained if kinetic fractionations were evoked by diffusion of CO2(aq) through water51.

The reaction rate of hydration and hydroxylation of the dissolved CO2 is orders of magnitude slower than the reaction rate of bicarbonate dissociation52. Both CO2(aq) hydration and hydroxylation preferentially select light isotopes (16O, 12C) and discriminate against heavy isotopes (18O, 13C). If the carbonate precipitation rate is high, HCO3− can dissociate into CO32− and H+ before reaching equilibrium with CO2(aq) in the calcifying fluid, therefore, the solid carbonate will inherit lighter δ18O values49,53. Simultaneously, incomplete CO2(aq) hydration or hydroxylation results in an increased ∆47 value of the aqueous HCO3−, which can be inherited by the solid carbonate if the precipitation rate is high14. Theoretical calculations predict a regression slope between the offset ∆47 offset and offset δ18O values in the order of −0.05 and −0.01 for kinetic controls associated with hydration and hydroxylation reactions, respectively12,54 (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Carbonic anhydrase, an enzyme often present in calcifying organisms, such as corals, promotes rapid oxygen isotope exchange between dissolved inorganic carbon species55,56. If this enzyme was present in brachiopods, it could reduce or eliminate the kinetic isotope effects caused by the slow hydration and hydroxylation reactions. However, carbonic anhydrase has not been identified in the calcifying fluid of modern brachiopods57.

Our data exhibits an offset ∆47–δ18O slope of −0.017(±0.03) if the offset δ18O values are calculated using the seawater oxygen isotope compositions acquired from the Global Seawater Oxygen-18 Database34 (Fig. 1b). If the offset δ18O values are calculated using directly measured water δ18O values where possible, the offset ∆47–δ18O slope becomes as steep as −0.039(±0.01) (Fig. 1c). Both slopes are significant and stay consistent, irrespective of data processing, i.e., [Gonfiantini] vs. [Brand] parameters, and the clumped isotope calibration we used to calculate the offset values (Supplementary Figs 2b,c and 3).

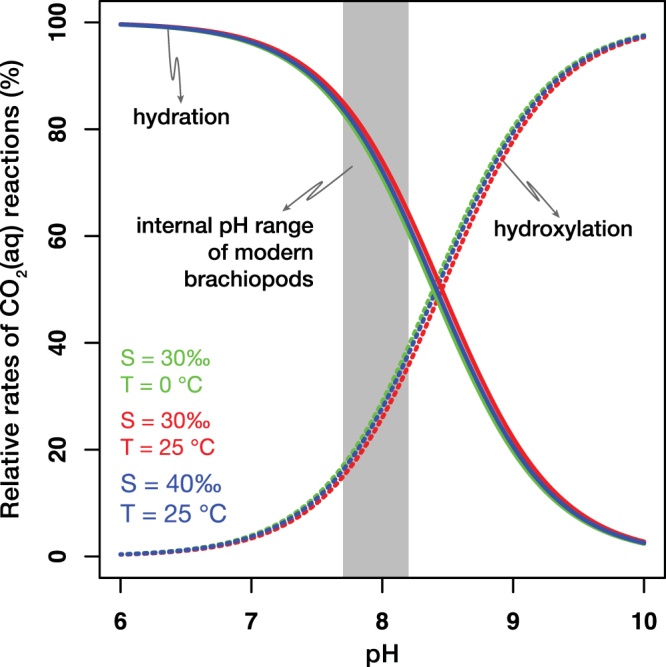

The observed correlation slopes (−0.017 to −0.039, depending on the seawater δ18O dataset) between offset ∆47 and offset δ18O point to the importance of kinetic effects associated with diffusion and incomplete hydration and hydroxylation of CO2(aq). The hydration and hydroxylation reactions occur superimposed onto the diffusion of CO2(aq). Consequently, diffusion alone cannot be the sole kinetic mechanism responsible for the observed trend in our data. If heterogeneous oxygen isotope exchange between water and CO2(aq) proceeds to equilibrium, it would erase the offsets from equilibrium ∆47 and δ18O generated during diffusion. Tang et al.37 precipitated calcites at a pH < 9 and >10 and observed that ∆47 values increased by approximately 0.016‰ for every 1‰ decrease in δ18O at high (>10) pH. They suggested that a combined effect of diffusion and hydroxylation could be responsible for the observed slope. Interestingly, their slope is indistinguishable from the one we observe when we exclusively use the Global Seawater Oxygen-18 Database34 to infer seawater δ18O. However, pH > 10 would be inconsistent with the internal pH range of modern brachiopods, which is likely to be between 7.7 and 8.2, calculated from δ11B values41. Hydration is more prominent at low (<8.4) pH while hydroxylation is more prominent at high (>8.4) pH, assuming temperature and salinity values characteristic of modern seawater49,52 (Fig. 4). In the pH range characteristic for modern brachiopods, only 10–40‰ of the oxygen isotope exchange between water and CO2(aq) should occur via the hydroxylation reaction, whereas 60–90% should proceed via the hydration reaction52 (Fig. 4). Such a dominance of hydration over hydroxylation would result in an offset ∆47–δ18O slope of −0.034 to −0.046, assuming estimated slopes of −0.05 and −0.01 to be characteristic of the hydration and hydroxylation reactions, respectively12,54. This range of slopes is in agreement with our result based on the dataset that combines gridded seawater δ18O data with directly measured values (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Figs 2c and 3b,d).

Figure 4.

At conditions characteristic to modern seawater, hydration is the dominant reaction at which CO2(aq) transforms into HCO3− in the brachiopod calcifying fluid. The balance between the rates of hydration and hydroxylation reactions is defined as R = (kCO2/(kCO2 + kOH/aH) * 100, where kCO2 and kOH are the rate constants for CO2(aq) hydration and hydroxylation, respectively and aH is the H+ activity52. R is calculated for three salinity (S) – temperature (T) scenarios, characteristic to modern seawater. The shaded area represents the internal pH range of modern brachiopods41.

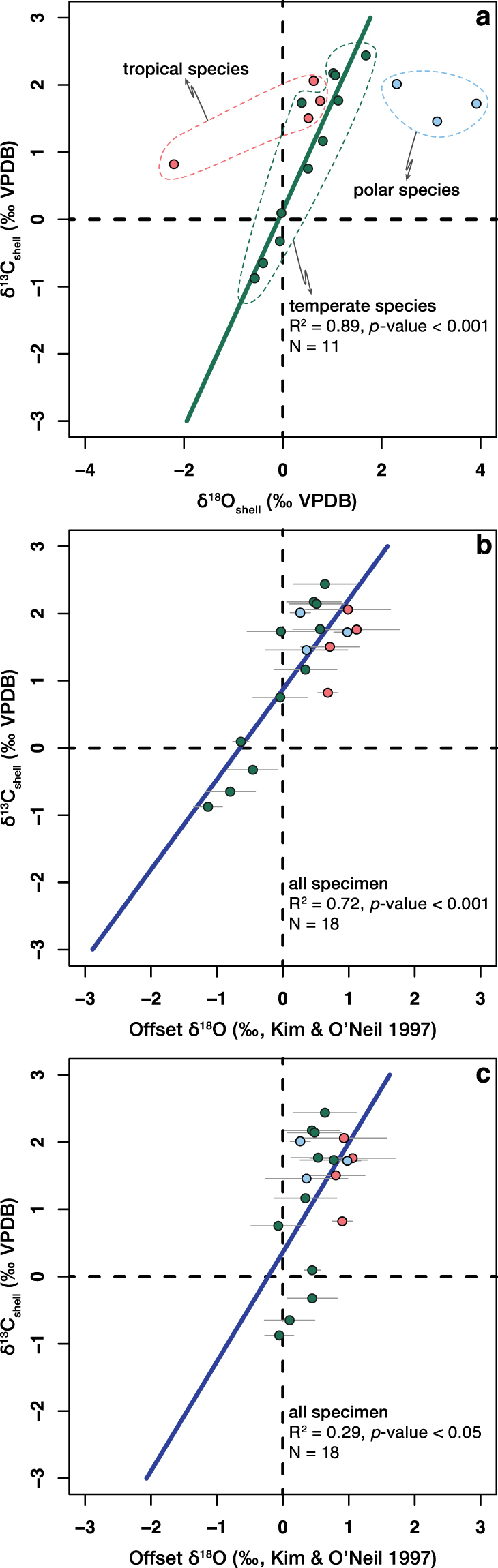

The δ18O values of the temperate modern brachiopod shells analysed in this study correlate well with corresponding δ13C values (R2 = 0.89, p-value < 0.001; Fig. 5a). Brand et al.58 showed that parallel correlations are present between shell δ18O and δ13C among tropical (latitudes < 30°), temperate (latitudes 30°–60°) and polar (latitudes > 60°) brachiopods, respectively. These parallel trends are related to the distinct habitat seawater temperatures and oxygen isotopic compositions of these groups58. With the exchange of the shell δ18O values for the offset δ18O values, the seawater and temperature effect on the shell δ18O can be eliminated. The offset δ18O values of the modern brachiopod shells analysed in this study correlate with corresponding δ13C values (R2 > 0.29, p-value < 0.05; Fig. 5b,c). A covariation of δ18O and δ13C has been also observed in single brachiopod shells by other authors22–24,41,43. A synchronous depletion of the heavy isotopes (18O and 13C) in biogenic carbonates, as observed for the modern brachiopods analysed in this study (Fig. 5a,b,c), agrees with the preferential selection of light isotopes during CO2(aq) hydration and hydroxylation reactions49,53,59.

Figure 5.

Correlation between brachiopod shell bulk oxygen and carbon isotope compositions. (a) The shell δ18O values of the temperate modern brachiopods analysed in this study positively correlate with corresponding δ13C values. (b) Shell δ13C values positively correlate with offset δ18O values for all modern brachiopods analysed in this study. Seawater δ18O values were acquired from the Global Seawater Oxygen-18 Database34. (c) The correlation between shell δ13C and offset δ18O is still present if, where available, the directly measured seawater δ18O values were used for the calculations. For all plots: two-tailed p-values are calculated using a t-test for the simple linear regressions. Error bars for the offset δ18O values indicate the mean deviation from oxygen isotope equilibrium calculated using the minimum and the maximum temperature estimates.

There is still an ongoing debate if the experiments of Kim and O’Neil35 are characteristic for the attainment of overall equilibrium between calcite and water. A natural example for equilibrium precipitation might be the Devil’s Hole carbonate that grew extremely slowly in a constant geochemical environment. Its isotope composition has therefore been postulated not to be affected by kinetics60. The δ18O value of the Devil’s Hole carbonate is approximately +1.5‰ higher than could be calculated using the equation of Kim and O’Neil35. Laboratory experiments, comparing oxygen isotope fractionation factors of slowly and rapidly precipitated synthetic calcites61, and theoretical computations62 provide further evidence that the Kim and O’Neil35 equation is not representative of thermodynamic equilibrium between calcite and water. The δ18O values of the modern brachiopods analysed in this study, which show apparent clumped isotope equilibrium, are enriched by up to 1‰, relative to the Kim and O’Neil35 equilibrium (Fig. 1b,c and Supplementary Figs 2b,c and 3). This finding is in line with the hypothesis60–62 that oxygen isotope equilibrium between calcite and water is expressed by fractionations exceeding those of Kim and O’Neil35.

In summary, the oxygen and clumped isotope composition of modern brachiopod shells are affected by growth rate-induced kinetic effects (i.e., incomplete hydration and/or hydroxylation of CO2(aq) at higher growth rates) as indicated by (1) the negative correlation between offset ∆47 and offset δ18O values, (2) the correlation between growth rates and both ∆47 and δ18O offsets and (3) the positive correlation between shell δ13C and δ18O values. Kinetic effects may significantly contribute to the bottom seawater temperatures calculated from brachiopod shell δ18O and ∆47. Combining isotope data derived from multiple species is likely to result in higher variability in observed δ18O and ∆47 that does not reflect real temperature changes. Based on our findings, information about taxon-specific growth rate and kinetics involved in calcite precipitation is essential whenever constraining seawater temperatures from ∆47 and δ18O values in brachiopods. A future study considering seasonal variations in seawater δ18O values and in growth rates could further improve our understanding of the nature and extent of the kinetic isotope effect in brachiopods.

Methods

Sampling of shells

Organic tissue and encrusting organisms were removed from the brachiopod shells using a metal pin and a brush. Specimen S006L, DS420L, and DS430L were submerged in diluted NaOCl for 5–10 minutes to soften the organic material. The shells were cleaned in an ultrasonic bath using deionized water. Afterwards, the shells were dried using pressured air and stored at room temperature. For the larger species, the primary layer of the shells was mechanically removed using a hand-held electric drill (Proxxon Micromot IBS/E) on the lowest speed setting and only the secondary and/or tertiary layers were sampled. An approximately 0.5 cm2 area from the anterior part of the ventral valve was crushed and homogenised using an agate mortar and pestle. We avoided sampling the umbo area, the hinge area, the muscle scar area and the youngest parts of the shell. Exceptions to this were the micromorphic shells of P. atlantica, T. congregata, Argyrotheca sp., and Megerlia sp., where 4 to 20 whole shells had to be crushed to acquire enough material for multiple replicate analyses.

Growth rate

The growth of brachiopods can be described by the von Bertalanffy asymptotic function63. Juvenile individuals grow the fastest and the growth rate decreases with age, before reaching the species-specific maximum size. To acquire comparable, species-specific growth rates, we estimated a minimum and a maximum growth rate for each analysed species. The maximum growth rate, in our case, depicted the average growth rate of the brachiopod until it reached 50% of its maximum size. Similarly, the minimum estimate was the average growth rate after the brachiopod had already reached 50% of its maximum size. For M. venosa63, M. fragilis64, M. sanguinea65, C. inconspicua66, T. transversa67 and L. neozelanica68, detailed studies were available, thus both a maximum and a minimum growth rate estimate could be calculated. Such a study has not, to date, been made for N. nigricans, therefore we used the available average juvenile growth rate69 as a maximum estimate. For the micromorphic brachiopods P. atlantica, Argyrotheca sp., Megerlia sp., and T. congregata, we assumed a 0.5 mm/yr and a 1.2 mm/yr as a minimum and as a maximum growth rate estimate, respectively. These growth rates are characteristic for micromorphic brachiopods70.

Trace element analyses

The magnesium content of the studied brachiopod shells was analysed using a Thermo Scientific iCap 6000 dual view ICP-OES (Inductively Coupled Plasma - Optical Emission Spectrometry) at the Goethe University, Frankfurt, Germany. For the analyses, we took 120–150 μg of carbonate powder from the homogenised batches that were also used for the isotope measurements and dissolved them in 0.500 cm3 2% HNO3. An aliquot of 0.300 cm3 of the sample solution was diluted with 1.500 cm3 yttrium water (until 1.000 mg/dm3) prior to measurement to correct for matrix biases during analyses. The Mg/Ca measurements were drift-corrected and standardized to an internal consistency standard (ECRM 752–1) measured alongside with the samples. The external reproducibility (2σ S.E.) for this standard was ±0.1 mmol/mol Mg/Ca. Finally, the MgCO3 concentration values (mol%) were adjusted to a 100% carbonate basis and were normalised to a combined Ca and Mg value of 395,000 ppm20.

Stable isotope analyses

Clumped isotope analyses were made using a fully automated gas extraction and purification line connected to a ThermoFisher MAT 253 gas-source isotope-ratio mass spectrometer at the Goethe University, Frankfurt, Germany. Homogenised carbonate powder was reacted at 90 °C with >105% phosphoric acid. In general, six replicate analyses were made every day including one carbonate standard, one equilibrated gas (1000 °C or 25 °C) and four sample replicates. Background correction was performed for the sample and the reference gas separately, as described in Fiebig et al.71 (Supplementary Fig. 5). Background-corrected equilibrated gas data displays slopes that are within errors indistinguishable from zero (Supplementary Data 1). Additional information concerning the methodology of the clumped isotope measurements can be found in the Supplementary Information.

The raw ∆47, δ18O and δ13C values were calculated using two sets of isotope parameters28. In the [Gonfiantini] set, the parameters are as follows: R13PDB = 0.0112372, R18VSMOW = 0.0020052, R17VSMOW = 0.0003799 and λ = 0.5164. In the [Brand] set, the parameters are: R13PDB = 0.01118, R18VSMOW = 0.0020052, R17VSMOW = 0.00038475 and λ = 0.528. The raw ∆47 values were projected to the CDES (Carbon Dioxide Equilibrium Scale72) using equilibrated gases. Empirical transfer functions (ETFs) were determined using gases of various bulk isotope compositions equilibrated at 25 °C and at 1000 °C, respectively. The intercept values of the equilibrated gases in the ∆47–δ47 space were constant between 06.06.2016–12.22.2016 and 01.06.2017–04.05.2017 (Supplementary Data 1, Supplementary Table 3). For referencing the ∆47 values to 25 °C, we used an acid fractionation factor of 0.081‰10. Two internal carbonate reference materials were analysed along with the samples to verify the precision and the stability of clumped isotope measurements: Carrara marble calcite (Carrara) and Arctica islandica (mollusk) shell aragonite (MuStd). The mean ∆47(CDES 25) values (±1σ S.E.) for the Carrara (N = 123) and the MuStd (N = 83) reference materials, calculated using the [Gonfiantini] set of isotopic parameters were 0.396(±0.001)‰ and 0.743(±0.002)‰, and using the [Brand] set of isotopic parameters were 0.395(±0.001)‰ and 0.738(±0.002)‰, respectively. The 1σ S.D. of the ∆47 values for the reference materials is 0.014‰. The [Gonfiantini] values agree within ≤ 0.005‰ with corresponding ∆47(CDES 25) values reported elsewhere for Carrara11,32,72 and MuStd73 after applying a consistent acid fractionation factor to these datasets.

Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry

The ion probe analyses were carried out using a Caméca IMS 1280-HR2 at CRPG-CNRS (Nancy, France). A short summary of the technique is reported in the Supplementary Information. The exact location of the ion probe transects and the analysed points are shown on Supplementary Figure 6. The two analysed shells were also investigated for clumped isotopes. The ventral valve of each brachiopod was cut in half from anterior to posterior part to produce a longitudinal section. One half was mounted in epoxy and polished with diamond paste down to 1µm. Transects from the outermost (primary layer) to the innermost part (closest to mantle cavity) of the shell were performed with 20 µm spots and with a constant step of 50 µm. The number of analysis was determined by the shell thickness. The location of the transect was approximately 3 mm above the anterior margin, at the exact location where the shell was sampled for the clumped and trace element analyses.

Data availability

All data pertinent to this manuscript and its reported findings can be found in the manuscript itself or the associated Supplementary Information file.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Hofmann and C. Schreiber (J. W. Goethe-Universität) for their technical assistance during the clumped isotope analyses, D. Henkel (GEOMAR) and L. Angiolini (University of Milan) for providing the P. atlantica and N. nigricans specimens and R. Sheward for language editing. This paper benefited from the constructive suggestions of Kozue Nishida and two anonymous reviewers. This project was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 643084 (BASE-LiNE Earth).

Author Contributions

B.D. and J.F. designed the study and wrote the manuscript. C.P.R. helped with the statistical treatment of data. A.T., U.B., J.R., C.R.B. and S.G.M. helped interpreting the data. B.D. and N.L. made the stable isotope measurements. J.R. and B.D. carried out the trace element analyses. S.G.M. and C.R.B. made the SIMS analyses.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-17353-7.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Curry, G. B. & Brunton, C. H. C. In Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part H, Brachiopoda (Revised) (ed P. A. Selden) 2901–3081 (Geological Society of America, University of Kansas, 2007).

- 2.Veizer J, Prokoph A. Temperatures and oxygen isotopic composition of Phanerozoic oceans. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2015;146:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2015.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brand U, Webster GD, Azmy K, Logan A. Bathymetry and productivity of the southern Great Basin seaway, Nevada, USA: An evaluation of isotope and trace element chemistry in mid-Carboniferous and modern brachiopods. Palaeogeog. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2007;256:273–297. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.02.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urey HC. The thermodynamic properties of isotopic substances. J. Chem. Soc. 1947;0:562–581. doi: 10.1039/jr9470000562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghosh P, et al. 13C–18O bonds in carbonate minerals: A new kind of paleothermometer. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2006;70:1439–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2005.11.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Came RE, et al. Coupling of surface temperatures and atmospheric CO2 concentrations during the Palaeozoic era. Nature. 2007;449:198–201. doi: 10.1038/nature06085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brand U, et al. Climate-forced change in Hudson Bay seawater composition and temperature, Arctic Canada. Chem. Geol. 2014;388:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2014.08.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cummins RC, Finnegan S, Fike DA, Eiler JM, Fischer WW. Carbonate clumped isotope constraints on Silurian ocean temperature and seawater δ18O. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2014;140:241–258. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2014.05.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Came RE, Brand U, Affek HP. Clumped isotope signatures in modern brachiopod carbonate. Chem. Geol. 2014;377:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2014.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Passey BH, Henkes GA. Carbonate clumped isotope bond reordering and geospeedometry. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2012;351-352:223–236. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2012.07.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henkes GA, et al. Carbonate clumped isotope compositions of modern marine mollusk and brachiopod shells. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2013;106:307–325. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2012.12.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spooner PT, et al. Clumped isotope composition of cold-water corals: A role for vital effects? Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2016;179:123–141. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2016.01.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adkins JF, Boyle EA, Curry WB, Lutringer A. Stable isotopes in deep-sea corals and a new mechanism for “vital effects”. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2003;67:1129–1143. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(02)01203-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saenger C, et al. Carbonate clumped isotope variability in shallow water corals: Temperature dependence and growth-related vital effects. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2012;99:224–242. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2012.09.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimball J, Eagle R, Dunbar R. Carbonate “clumped” isotope signatures in aragonitic scleractinian and calcitic gorgonian deep-sea corals. Biogeosciences. 2016;13:6487–6505. doi: 10.5194/bg-13-6487-2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grauel A-L, et al. Calibration and application of the ‘clumped isotope’ thermometer to foraminifera for high-resolution climate reconstructions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2013;108:125–140. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2012.12.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowenstam HA. Mineralogy, O18/O16 ratios, and strontium and magnesium contents of recent and fossil brachiopods and their bearing on the history of the oceans. Journ. Geol. 1961;69:241–260. doi: 10.1086/626740. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carpenter SJ, Lohmann KC. δ18O and δ13C values of modern brachiopod shells. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1995;59:3749–3764. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(95)00291-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cusack M, Huerta AP. & EIMF. Brachiopods recording seawater temperature - A matter of class or maturation? Chem. Geol. 2012;334:139–143. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brand U, et al. Oxygen isotopes and MgCO3 in brachiopod calcite and a new paleotemperature equation. Chem. Geol. 2013;359:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2013.09.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parkinson D, Curry GB, Cusack M, Fallick AE. Shell structure, patterns and trends of oxygen and carbon stable isotopes in modern brachiopod shells. Chem. Geol. 2005;219:193–235. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2005.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamamoto K, Asami R, Iryu Y. Carbon and oxygen isotopic compositions of modern brachiopod shells from a warm-temperate shelf environment, Sagami Bay, central Japan. Palaeogeog. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2010;291:348–359. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamamoto K, Asami R, Iryu Y. Within-shell variations in carbon and oxygen isotope compositions of two modern brachiopods from a subtropical shelf environment off Amami-o-shima, southwestern Japan. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2010;11:1–16. doi: 10.1029/2010GC003190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Auclair A-C, Joachimski MM, Lécuyer C. Deciphering kinetic, metabolic and environmental controls on stable isotope fractionations between seawater and the shell of Terebratalia transversa (Brachiopoda) Chem. Geol. 2003;202:59–78. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2541(03)00233-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rollion-Bard C, et al. Variability in magnesium, carbon and oxygen isotope compositions of brachiopod shells: Implications for paleoceanographic studies. Chem. Geol. 2016;423:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2016.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jean CB, Kyser TK, James NP, Stokes MD. The Antarctic brachiopod Liothyrella uva as a proxy for ambient oceanographic conditions at McMurdo Sound. J. Sediment. Res. 2015;85:1492–1509. doi: 10.2110/jsr.2015.94. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ullmann CV, Frei R, Korte C, Lüter C. Element/Ca, C and O isotope ratios in modern brachiopods: Species-specific signals of biomineralization. Chem. Geol. 2017;460:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2017.03.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daëron M, Blamart D, Peral M, Affek HP. Absolute isotopic abundance ratios and the accuracy of Δ47 measurements. Chem. Geol. 2016;442:83–96. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2016.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wacker U, et al. Empirical calibration of the clumped isotope paleothermometer using calcites of various origins. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2014;141:127–144. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2014.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.York D, Evensen NM, Martínez ML, De Basabe Delgado J. Unified equations for the slope, intercept, and standard errors of the best straight line. Am. J. Phys. 2004;72:367–375. doi: 10.1119/1.1632486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Locarnini, R. A. et al. World Ocean Atlas 2013, Volume 1: Temperature. (2013).

- 32.Bonifacie M, et al. Calibration of the dolomite clumped isotope thermometer from 25 to 350 °C, and implications for a universal calibration for all (Ca, Mg, Fe)CO3 carbonates. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2017;200:255–279. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2016.11.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaarur S, Affek HP, Brandon MT. A revised calibration of the clumped isotope thermometer. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2013;382:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2013.07.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.LeGrande AN, Schmidt GA. Global gridded data set of the oxygen isotopic composition in seawater. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006;33:1–5. doi: 10.1029/2006GL026011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim S-T, O’Neil JR. Equilibrium and nonequilibrium oxygen isotope effects in synthetic carbonates. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1997;61:3461–3475. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(97)00169-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Defliese WF, Hren MT, Lohmann KC. Compositional and temperature effects of phosphoric acid fractionation on Δ47 analysis and implications for discrepant calibrations. Chem. Geol. 2015;396:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2014.12.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang J, Dietzel M, Fernandez A, Tripati AK, Rosenheim BE. Evaluation of kinetic effects on clumped isotope fractionation (Δ47) during inorganic calcite precipitation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2014;134:120–136. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2014.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelson JR, Huntington KW, Schauer AJ, Saenger C, Lechler AR. Toward a universal carbonate clumped isotope calibration: Diverse synthesis and preparatory methods suggest a single temperature relationship. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2017;197:104–131. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2016.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eiler JM, Schauble E. 18O13C16O in Earth’s atmosphere. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2004;68:4767–4777. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2004.05.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Defliese WF, Lohmann KC. Non-linear mixing effects on mass-47 CO2 clumped isotope thermometry: Patterns and implications. Rap. Commun. Mass Spec. 2015;29:901–909. doi: 10.1002/rcm.7175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Penman DE, Hönisch B, Rasbury ET, Hemming NG, Spero HJ. Boron, carbon, and oxygen isotopic composition of brachiopod shells: Intra-shell variability, controls, and potential as a paleo-pH recorder. Chem. Geol. 2013;340:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2012.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.von Allmen K, et al. Stable isotope profiles (Ca, O, C) through modern brachiopod shells of T. septentrionalis and G. vitreus: Implications for calcium isotope paleo-ocean chemistry. Chem. Geol. 2010;269:210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2009.09.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamamoto K, Asami R, Iryu Y. Correlative relationships between carbon- and oxygen-isotope records in two cool-temperate brachiopod species off Otsuchi Bay, northeastern Japan. Paleontol. Res. 2013;17:12–26. doi: 10.2517/1342-8144-17.1.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takayanagi H, et al. Quantitative analysis of intraspecific variations in the carbon and oxygen isotope compositions of the modern cool-temperate brachiopod Terebratulina crossei. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2015;170:301–320. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2015.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams A. Differentiation and growth of the brachiopod mantle. Am. Zool. 1977;17:107–120. doi: 10.1093/icb/17.1.107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simkiss, K. & Wilbur, K. M. Biomineralization - Cell biology and mineral deposition. (Academic Press, 1989).

- 47.Takayanagi H, et al. Intraspecific variations in carbon-isotope and oxygen-isotope compositions of a brachiopod Basiliola lucida collected off Okinawa-jima, southwestern Japan. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2013;115:115–136. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2013.03.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hughes WW, Rosenberg GD, Tkachuck RD. Growth increments in the shell of the living brachiopod Terebratalia transversa. Mar. Biol. 1988;98:511–518. doi: 10.1007/BF00391542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McConnaughey T. 13C and 18O isotopic disequilibrium in biological carbonates: II. In vitro simulation of kinetic isotope effects. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1989;53:163–171. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(89)90283-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tripati AK, et al. Beyond temperature: Clumped isotope signatures in dissolved inorganic carbon species and the influence of solution chemistry on carbonate mineral composition. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2015;166:344–371. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2015.06.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thiagarajan N, Adkins J, Eiler J. Carbonate clumped isotope thermometry of deep-sea corals and implications for vital effects. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2011;75:4416–4425. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2011.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnson KS. Carbon dioxide hydration and dehydration kinetics in seawater. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1982;27:894–855. [Google Scholar]

- 53.McConnaughey T. 13C and 18O isotopic disequilibrium in biological carbonates: I. Patterns. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1989;53:151–162. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(89)90282-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guo, W., Kim, S., Thiagarajan, N., Adkins, J. F. & Eiler, J. M. In American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting PP34B-07 (2009).

- 55.Uchikawa J, Zeebe RE. The effect of carbonic anhydrase on the kinetics and equilibrium of the oxygen isotope exchange in the CO2–H2O system: Implications for δ18O vital effects in biogenic carbonates. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2012;95:15–34. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2012.07.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Watkins JM, Hunt JD, Ryerson FJ, DePaolo DJ. The influence of temperature, pH, and growth rate on the δ18O composition of inorganically precipitated calcite. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2014;404:332–343. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2014.07.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jackson DJ, et al. The Magellania venosa biomineralizing proteome: A window into brachiopod shell evolution. Genome Biology and Evolution. 2015;7:1349–1362. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brand U, et al. Carbon isotope composition in modern brachiopod calcite: A case of equilibrium with seawater? Chem. Geol. 2015;411:81–96. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2015.06.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Keith ML, Weber JN. Systematic relationships between carbon and oxygen isotopes in carbonates deposited by modern corals and algae. Science. 1965;150:498–501. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3695.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Coplen TB. Calibration of the calcite–water oxygen-isotope geothermometer at Devils Hole, Nevada, a natural laboratory. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2007;71:3948–3957. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2007.05.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dietzel M, Tang JW, Leis A, Kohler SJ. Oxygen isotopic fractionation during inorganic calcite precipitation - Effects of temperature, precipitation rate and pH. Chem. Geol. 2009;268:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2009.07.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Watkins JM, Nielsen LC, Ryerson FJ, DePaolo DJ. The influence of kinetics on the oxygen isotope composition of calcium carbonate. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2013;375:349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2013.05.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baumgarten S, Laudien J, Jantzen C, Häussermann V, Försterra G. Population structure, growth and production of a recent brachiopod from the Chilean fjord region. Mar. Eco. 2014;35:401–413. doi: 10.1111/maec.12097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brey T, Peck LS, Gutt J, Hain S, Arntz WE. Population dynamics of Magellania fragilis, a brachiopod dominating a mixed-bottom macrobenthic assemblage on the Antarctic shelf. J. Mar. Biol. Ass. 1995;75:857–869. doi: 10.1017/S0025315400038200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ostrow, D. G. Larval dispersal and population genetic structure of brachiopods in the New Zealand fjords PhD thesis, University of Otago, (2004).

- 66.Doherty PJ. Demographic study of a subtidal population of the New Zealand articulate brachiopod Terebratella inconspicua. Mar. Biol. 1979;52:331–342. doi: 10.1007/BF00389074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Paine RT. Growth and size distribution of the brachiopod Terebratalia transversa Sowerby. Pac. Sci. 1969;23:337–343. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baird MJ, Lee DE, Lamare MD. Reproduction and growth of the terebratulid brachiopod Liothyrella neozelanica Thomson, 1918 From Doubtful Sound, New Zealand. Biological Bulletin. 2013;225:125–136. doi: 10.1086/BBLv225n3p125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee DE, et al. Observations on recruitment, growth and ecology in a diverse living brachiopod community, Doubtful Sound, Fiordland, New Zealand. Spec. Pap. Palaeo. 2010;84:177–191. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pakhnevich AV. Reasons of micromorphism in modern or fossil brachiopods. Paleontol. J. 2010;43:1458–1468. doi: 10.1134/S0031030109110100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fiebig J, et al. Slight pressure imbalances can affect accuracy and precision of dual inlet-based clumped isotope analysis. Isot. Environ. Health Stud. 2016;52:12–28. doi: 10.1080/10256016.2015.1010531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dennis KJ, Affek HP, Passey BH, Schrag DP, Eiler JM. Defining an absolute reference frame for ‘clumped’ isotope studies of CO2. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2011;75:7117–7131. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2011.09.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kele S, et al. Temperature dependence of oxygen- and clumped isotope fractionation in carbonates: a study of travertines and tufas in the 6–95 °C temperature range. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2015;168:172–192. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2015.06.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data pertinent to this manuscript and its reported findings can be found in the manuscript itself or the associated Supplementary Information file.