Abstract

Heterotrimeric G proteins play central roles in many signaling pathways, including the phototransduction cascade in animals. However, the degree of involvement of the G protein subunit Gαq is not clear since animals with previously reported strong loss-of-function mutations remain responsive to light stimuli. We recovered a new allele of Gαq in Drosophila that abolishes light response in a conventional electroretinogram assay, and reduces sensitivity in whole-cell recordings of dissociated cells by at least five orders of magnitude. In addition, mutant eyes demonstrate a rapid rate of degeneration in the presence of light. Our new allele is likely the strongest hypomorph described to date. Interestingly, the mutant protein is produced in the eyes but carries a single amino acid change of a conserved hydrophobic residue that has been assigned to the interface of interaction between Gαq and its downstream effector, PLC. Our study has thus uncovered possibly the first point mutation that specifically affects this interaction in vivo.

Keywords: phototransduction, photoreceptor, G protein, ERG, Gαq, Gα PLC interaction, light-induced retinal degeneration

G proteins are essential in the physiological responses to exogenous stimuli. G proteins normally consist of three subunits: Gα, Gβ, and Gγ (Neer 1995; Neves et al. 2002). In its inactive state, Gα binds GDP and forms a heterotrimeric complex with Gβ and Gγ. Upon exogenous stimulation, GTP exchange factors, such as G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), convert Gα into a GTP-bound state and release Gα from Gβ and Gγ (Siderovski and Willard 2005; Oldham and Hamm 2008; Rosenbaum et al. 2009; Campden et al. 2015). How Gα activates downstream targets differs according to the types of Gα involved. Gαs and Gαi both act through regulating the level of the secondary messenger cAMP, although in opposite ways (Hildebrandt et al. 1983; Sunahara and Taussig 2002; Garcia-Marcos et al. 2009). The Gαq subfamily, on the other hand, acts by activating downstream phospholipase C (PLC) (Running Deer et al. 1995; Rhee 2001). Activated G protein heightens its GTPase activity by binding to GTPase-activating proteins (e.g., RGS proteins or PLC itself) and converts the GTP-bound state into a GDP-bound one, thus terminating the biological response (Arshavsky and Bownds 1992; Cook et al. 2000; Ross and Wilkie 2000; Hollinger and Hepler 2002). Because G proteins are essential for a large number of biological processes and their dysfunction can lead to human diseases such as cancer, the mechanism by which G proteins function has been the subject of intense investigation (Zwaal et al. 1996; Ruppel et al. 2005; Kelly et al. 2006; Shan et al. 2006).

The visual system of the fruit fly Drosophila has been a fertile ground for studies of G protein. Upon light stimulation, the GPCR rhodopsin is transformed into its activated form, called metarhodopsin, which activates G protein (Lee et al. 1990, 1994; Kiselev and Subramaniam 1994; Scott et al. 1995). The activated Gαq subunit dissociates from Gβ and Gγ and activates PLC, which in turn generates secondary messengers that ultimately open the TRP and TRPL Ca++ channels and results in the depolarization of the photoreceptor cells (Montell and Rubin 1989; Hardie and Minke 1992; Leung et al. 2008; Hardie and Franze 2012). Upon termination of the light stimulus, Gαq relocates to the cell membrane, reforms the heterotrimeric complex, and reverts to the inactive GDP-bound conformation. Many aspects of the light response in Drosophila can be reliably monitored by the simple electroretinogram (ERG) recording method (Wang et al. 2005a; Wang and Montell 2007), which has been widely used to identify mutants that are defective in various aspects of the phototransduction cascade.

Although placed in a central position in the phototransduction cascade, whether the Gαq subunit is essential for transduction has not been firmly established because existing mutants still have some response to light. This may reflect the hypomorphic nature of existing mutations or the fact that Drosophila Gαq has numerous splice variants, with different amino acid compositions and different tissue expression patterns (Lee et al. 1990; Talluri et al. 1995; Alvarez et al. 1996; Ratnaparkhi et al. 2002). For example, the original Gαq1 allele results in the loss of 99% of an eye-specific Gαq protein (quantified by Western blot analysis), yet still retains a substantial ERG response (Scott et al. 1995). Moreover, the Gαq961 allele with a premature stop codon in the head-specific isoform does not eliminate the ERG response (Hu et al. 2012). Moreover, neither mutation causes a rapid light-induced retinal degeneration, whereas other severe loss-of-function mutants of the visual system do.

In this study, we recovered a new Gαq allele with a single residue change in the most abundant isoform in the adult compound eye. Remarkably, this new allele has a much more severe phenotype than any previously identified Gαq alleles, yielding an essentially flat ERG response. The mutant eyes also demonstrate a rapid rate of light-induced degeneration. We show that the mutant Gαq protein is still expressed in the eye but is likely nonfunctional. Interestingly, the altered residue lies in a region of Gαq important for its interaction with PLC based on Gα structural studies.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila stocks

The genotype of wild-type flies used in our study is w1118. All flies we used for this study were put into the w1118 background to eliminate the effects of genetic backgrounds. The collection from which our Gαq allele was recovered was kindly provided by Dr. Yi Rao’s group at Beijing University of China. The mutant stocks of Gαq1, trp343, and norpAP24 were obtained from Dr. Junhai Han at Southeast University of China. The deficiency stocks and the gmr-gal4 driver stock (BL8605) were from the Bloomington Stock Center. To avoid light and age-dependent retinal degeneration, flies were reared in standard medium at 25° in the dark and examined when they were 1–2 d old. The three mutations discussed in this study and their location according to Figure 1A of Alvarez et al. (1996) are: (1) Gαq1, which is a three amino acid deletion in exon 4A; (2) Gαq961, which is a premature stop in exon 4A; and (3) GαqV303D, which is in exon 7A.

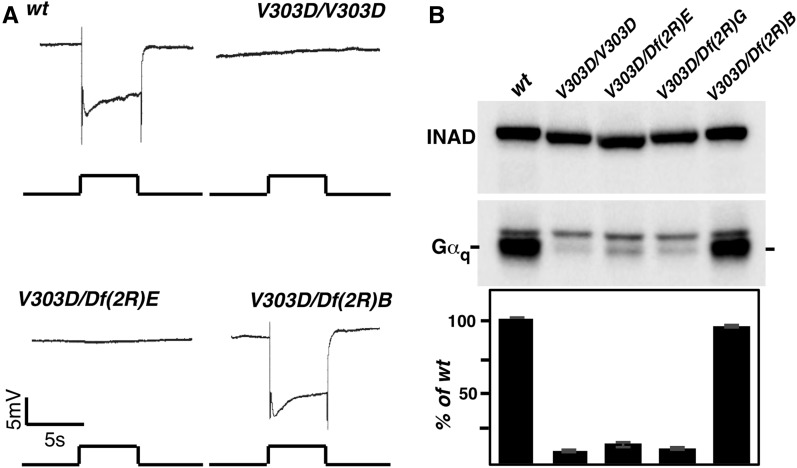

Figure 1.

A new Gαq mutant with a flat ERG response. (A) ERG recording in various genetic backgrounds. Flies that are either homozygous for the V303D mutation or trans-heterozygous for V303D and a chromosomal deficiency uncovering the Gαq region “Df(2R)E” (abbreviated for Df(2R)Exel7121) show a nearly complete loss of response to light stimulation. However, flies trans-heterozygous for V303D and a chromosomal deficiency uncovering an adjacent region to Gαq “Df(2R)B” (abbreviated for Df(2R)BSC485) displayed a normal ERG recoding. For all ERG recordings, event markers represent 5-sec orange light pulses, and scale bar for the vertical axis is 5 mV. (B) The level of Gαq protein in various genetic backgrounds. Western blot was used to detect Gαq protein level in whole exact from fly heads with the indicated genotypes. “Df(2R)G” is the abbreviation for Df(2R)Gαq1.3. In each genotype, the Gαq band is marked and the upper band is nonspecific. INAD was used as a loading control. Quantification of the Western blot results is shown below. The complete genotypes are as follows: w1118 (wt); w1118; GαqV303D (V303D); w1118; GαqV303D/Df(2R)Exel7121 (V303D/Df(2R)E); w1118; GαqV303D/Df(2R)Gαq1.3 (V303D/Df(2R)G); w1118; GαqV303D/Df(2R)BSC485 (V303D/Df(2R)B).

Rescuing Gαq phenotypes with transgenes

To generate transgenic flies carrying individual constructs of UAS-Gαq, UAS-GαqV303D, or UAS-GαqV303I, a wild-type cDNA clone of Gαq was changed to carry the V303D or V303I mutations using site-directed mutagenesis. All three cDNA clones were then subcloned into the pUAST-attB vector and introduced into Drosophila by phi-C31–mediated transformation. The transgenes were subsequently crossed into the GαqV303D mutant background and Gαq expression was driven by the eye-specific GMR-Gal4 driver.

Antibodies

Antibodies used in this study were mouse anti-TRP (83F6) (DSHB), mouse anti-Rh1 (4C5) (DSHB), rabbit anti-Gαq (Calbiochem), rabbit anti-Arr2 (Han et al. 2006), rabbit anti-INAD (Wes et al. 1999), and anti-PLC (Wang et al. 2005b).

Electrophysiological recording

ERG recordings were performed as previously described (Hu et al. 2012). Briefly, 1 or 2-d-old flies were collected, immobilized with strips of tape, and kept in the dark for 5 min before recording. Two glass microelectrodes, filled with Ringer’s solution, were placed on the compound eye and thorax. Flies were stimulated with a Newport light projector for a 5 sec light pulse (2000 Lux). The signal was amplified and recorded using a Warner IE210 Intracellular Electrometer. For each genotype, >10 flies were examined.

Whole-cell recordings

Whole-cell patch clamp recordings of photoreceptors of dissociated ommatidia from newly eclosed, dark-reared adult flies of either sex were performed as previously described (Hardie et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2005b). The bath contained (in mM) 120 NaCl, 5 KCl, 10 N-Tris-(hydroxymethyl)-methyl-2-amino-ethanesulfonic acid (TES), 4 MgCl2, 1.5 CaCl2, 25 proline, and 5 alanine (pH 7.15). The intracellular pipette solution (in mM) was 140 K gluconate, 10 TES, 4 Mg-ATP, 2 MgCl2, 1 NAD, and 0.4 Na-GTP (pH 7.15).

Electron microscopy

Electron microscopy (EM) was performed as previously described (Hu et al. 2015). Briefly, fly heads were fixed for 2 hr in 0.5% glutaraldehyde, 4% paraformaldehyde, and 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (pH 7.2) at 4°. After three washes with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, fly heads were stained with 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 hr at room temperature. They were washed three times and stained with uranyl acetate overnight. After a standard ethanol dehydration series, fly heads were rinsed in propylene oxide twice before they were embedded using standard procedures. Thin sections (100 nm) were cut at the top two thirds of retina, collected on Cu support grids, and stained with uranyl acetate for 15 min, followed with 10 min in lead citrate. Micrographs were taken at 120 kV on a JEM-1400 transmission EM.

Immunostaining

Section staining was carried out as previously described (Tian et al. 2013). Briefly, isolated fly heads were fixed for 2 hr at 4° with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The fly heads were dehydrated with acetone and embedded in LR White resin. Cross-sections of 1 μm were made across the top two thirds of retina, collected, and stained with antibodies (Rh1, 1:200; INAD, 1:400; TRP, 1:400). After being washed in PBS, cross-sections were incubated with secondary antibodies and Phalloidin at room temperature for 1 hr. The stained sections were examined under a ZEISS Axio Image A2 microscope.

Gαq protein translocation assay

Gαq translocation assay was performed as described previously (Frechter et al. 2007). Wild-type and mutant flies were each separated into three groups and treated differently. The D group (dark) was kept in the dark for 2 hr before they were killed for Western blotting. The L group (light) was kept in the dark for 2 hr, and then exposed to bright light for 2 hr before being killed. The LD group (light and dark) was kept in the dark for 2 hr, then exposed to bright light for 2 hr, and finally returned to complete darkness for 2 hr. Flies were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and the heads isolated and homogenized in PBS. Pellets and supernatant fractions were separated by centrifuging at 14,000 × g for 4 min before subjecting to Western blot analysis.

Data availability

The research reagents generated in this study are freely available upon request. The authors affirm that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are represented fully within the article.

Results

A new Gαq allele with a flat ERG response

We have been using the ERG recording method to screen mutagenized Drosophila collections to uncover new players in the phototransduction cascade. We recovered a new mutant line with a flat ERG response (Figure 1A and Figure 2A). Genetic mapping based on the loss of a ERG response revealed that the new mutation is uncovered by the chromosomal deficiencies of Df(2R)Exel7121 and Df(2R)Gαq1.3, which include the Drosophila Gαq locus. Genomic sequencing identified a single T to A nucleotide change in Gαq, making it the prime candidate for the responsible gene. This mutation results in a Val to Asp change at residue 303, and the mutant was thus named GαqV303D, or V303D for short. The V303 residue is specific to the Gαq isoform in the eye.

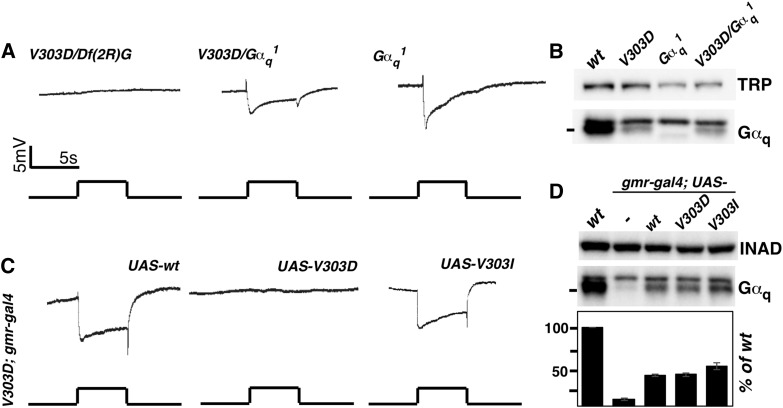

Figure 2.

Defective Gαq protein but not the reduction in Gαq level is responsible for the loss of a light response. (A) ERG recordings of Gαq mutants. Flies trans-heterozygous for V303D and the deficiency Df(2R)Gαq1.3 displayed no light response. Mutants either homozygous for the Gαq1 mutation or trans-heterozygous for Gαq1 and V303D displayed a substantial response to light. (B) Western blot analyses of Gαq protein level showed that Gαq level is lower in Gαq1 mutants than in V303D homozygous mutants. TRP serves as a loading control. (C) The ERG recordings of V303D mutants expressing different Gαq variants. Flies carrying homozygous V303D mutation, a GMR-Gal4 transgene, and different UAS-Gαq transgenes were subject to ERG recording. Both the wild-type Gαq and the mammalian mimic V303I transgenes rescued the ERG phenotype. For all ERG traces, event markers represent 5-sec orange light pulses, and scale bars are 5 mV. (D) Western blot measurement of Gαq protein level in rescued lines. Gαq level was restored to 40% of the wild-type level when GMR-Gal4 was used to drive Gαq expression. INAD served as a loading control. Quantification of the Western blot results is given below. The complete genotypes are as follows: w1118 (wt); w1118; GαqV303D (V303D); w1118; GαqV303D/Df(2R)Gαq1.3 (V303D/Df(2R)G); w1118; Gαq1 (Gαq1); w1118; GαqV303D/Gαq1 (V303D/Gαq1); w1118; GαqV303D gmr-Gal4; UAS-Gαq+; w1118; GαqV303D gmr-Gal4; UAS-GαqV303D; w1118; GαqV303D gmr-Gal4; UAS-GαqV303I.

To confirm that the V303D mutation is responsible for the flat ERG response, we introduced a wild-type copy of the Gαq cDNA driven by the eye-specific GMR promoter into V303D homozygotes, or V303D trans-heterozygotes with a Gαq deficiency, and was able to rescue the ERG response in both cases (Figure 2C). Therefore, the defective ERG response in our mutant is caused by a defective Gαq gene. It is worth noting that before our work, only a few genetic backgrounds were shown to produce a flat ERG response: single mutations in the rdgA gene that encodes diacylglycerol kinase (Masai et al. 1997; Raghu et al. 2000) and the norpA gene that encodes PLC (McKay et al. 1995; Kim et al. 2003), or double mutations in the trp and trpl channels (Leung et al. 2000, 2008; Yoon et al. 2000). This suggests that the new Gαq mutation that we identified is likely to be one of the strongest mutations of the phototransduction cascade in Drosophila.

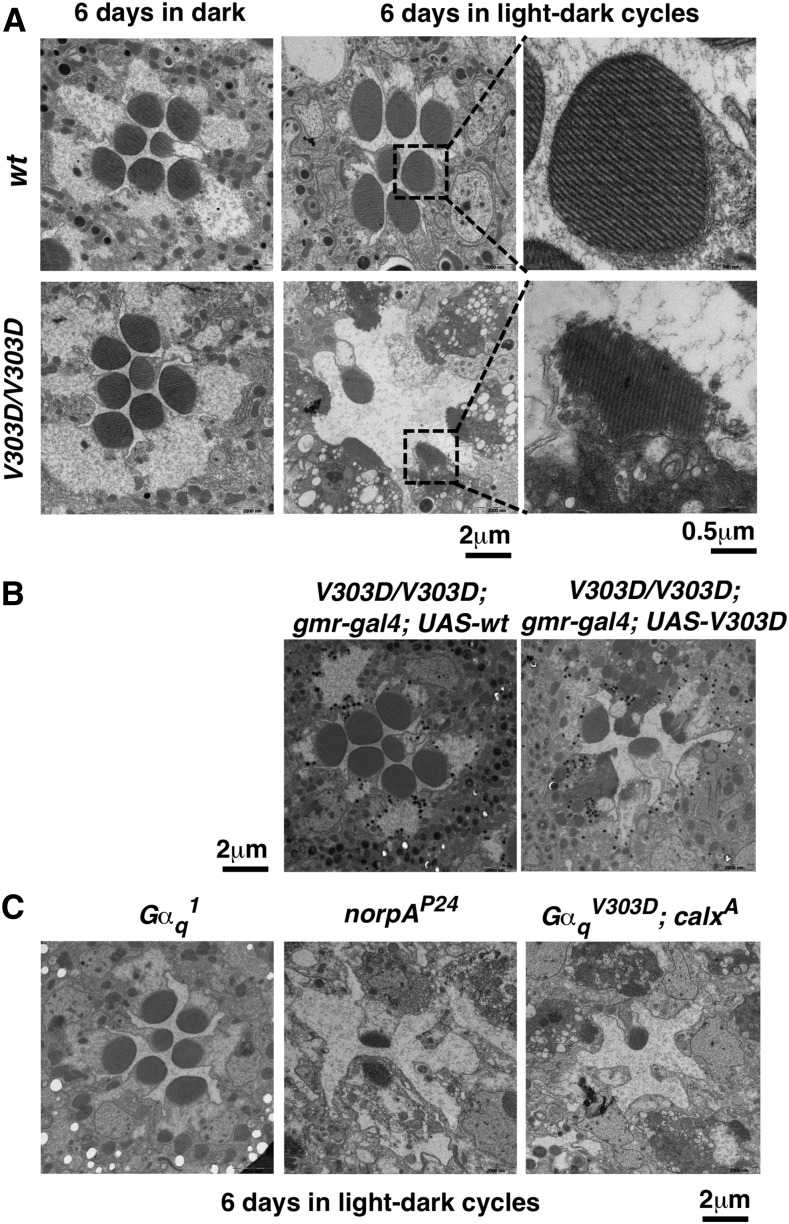

GαqV303D flies undergo rapid retinal degeneration

Many mutants in the Drosophila phototransduction cascade display light-dependent retinal degeneration, including flies with previously identified Gαq mutants (Hu et al. 2012). We raised GαqV303D adults under either regular light-dark cycles or constant dark conditions, and assayed retinal degeneration using EM. We observed severe degeneration in eyes taken from 6-d-old GαqV303D mutants raised under light-dark cycles (Figure 3A), but not from those reared in constant dark (Figure 3A). This degree of light-dependent retinal degeneration was more severe than in previously identified Gαq1 mutants (Figure 3B). Under similar rearing conditions, Gαq1 and Gαq961 mutant eyes display visible degeneration only after 21 d posteclosion (Hu et al. 2012). As shown in Figure 3B, this degree of fast degeneration in V303D mutants resembles that in norpA mutants (loss of PLC), suggesting that the phototransduction pathway in the mutants might have terminated before reaching PLC. Importantly, this visual degeneration of GαqV303D eyes was rescued by the GMR-driven Gαq transgene (Figure 3B). Interestingly, increasing Ca++ concentration with the calxA mutation was not able to rescue the degeneration phenotype (Figure 3C). Therefore, it is unlikely that a drop in Ca++ level in GαqV303D eyes leads to degeneration by preventing RdgC’s dephosphorylation of M-PPP (Wang et al. 2005b).

Figure 3.

GαqV303D mutants undergo rapid light-dependent retinal degeneration. (A) Electron microcopy images of an ommatidium from wild-type and V303D mutant eyes, with higher magnification images of selected rhabdomeres (highlighted with a square) shown to the right. Flies were raised for 6 d under either constant dark condition or a 12 hr light/12 hr dark cycle. (B) The GMR-driven wild-type Gαq transgene, but not the V303D mutant transgene, rescues visual degeneration of the V303D mutant. Scale bars are indicated at the bottom. (C) Retinal degeneration did not happen in similarly dark/light-treated 6-d-old eyes from Gαq1. Fast degeneration of V303D eyes is similar to norpA mutants, and could not be relieved by a calx mutation. The complete genotypes are as follows: w1118 (wt); w1118; GαqV303D (V303D); w1118; GαqV303D gmr-Gal4; UAS-Gαq+; w1118; GαqV303D gmr-Gal4; UAS-GαqV303D; w1118; Gαq1; w1118; norpAP24; w1118; GαqV303D; calxA.

GαqV303D encodes a nonfunctional protein

Both the Gαq1 and Gαq961 alleles previously identified behave as strong loss-of-function alleles (Figure 2A). However, the new GαqV303D allele lacks a response on a conventional ERG setting, although it does produce a small response with very bright illumination (see Figure 6). Interestingly, GαqV303D/Gαq1 trans-heterozygotes behave similarly to Gαq1 homozygous mutants (Figure 2A), consistent with Gαq1 being a hypomorphic mutation and V303D being a functionally null mutant based on ERG recordings. Since the Gαq961 mutant is no longer available, we were not able to test its genetic relationship with V303D.

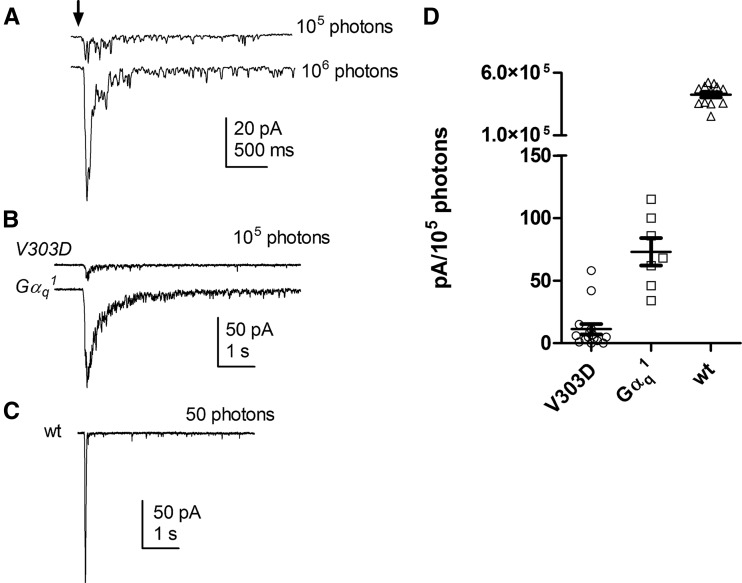

Figure 6.

Light responses measured by whole-cell recording. (A) GαqV303D mutants display greatly reduced responses to 10 msec flashes containing ∼105 and 106 effective photons. (B) GαqV303D mutant’s response to 100 msec flashes containing 105 photons was greatly reduced when compared with that of Gαq1 mutants. (C) A wild-type response is shown. (D) Summary data of peak amplitudes in response to flashes containing 105 photons in wt (n = 11), GαqV303D (n = 15), and Gαq1 (n = 7) mutants. The complete genotypes are as follows: w1118 (wt); w1118; GαqV303D (V303D); w1118; Gαq1 (Gαq1).

Similar with other Gαq mutants, V303D results in a substantial reduction in protein level (∼10% of the wild-type level remaining) as shown by Western blot analyses of total proteins from adult heads (Figure 1B and Figure 2, B and D). However, it is unlikely that this reduction of Gαq protein alone could account for the essentially complete loss of visual capacity in V303D mutants, since Gαq1 results in a more severe loss of Gαq protein (Figure 2B) yet retains a substantial ERG response (Figure 2A). To provide direct evidence supporting the proposition that the visual defects in V303D are at least partly due to the production of a defective Gαq protein, we tested the effect of increasing the level of the V303D mutant protein. As shown in Figure 2D, GMR-driven expression of the wild-type Gαq protein, although only reaching ∼40% of the endogenous Gαq level in wild-type eyes, is sufficient to rescue the ERG defect in V303D mutants (Figure 2C). On the other hand, when the mutant V303D protein was expressed at a similar level (Figure 2D), it was still unable to rescue the ERG defect (Figure 2C). Therefore, a simple elevation of the GαqV303D protein is insufficient to restore visual function, implying that the V303D protein is itself defective, and that its nonfunctionality might have led to its instability.

Other components in the phototransduction cascade are normal in GαqV303D mutants

The flat ERG response of GαqV303D eyes resemble those produced by severe loss-of-function mutations of other components in the phototransduction cascade, such as those in the PLC enzyme (Harris and Stark 1977; McKay et al. 1995; Kim et al. 2003; LaLonde et al. 2005) and the TRP and TRPL channels downstream of the G protein (Leung et al. 2000, 2008; Yoon et al. 2000; Popescu et al. 2006). This suggests that the V303D mutant Gαq is unable to support phototransduction; however, we also considered the possibility that V303D is a neomorphic mutation and that the mutant protein indirectly affects the development of photoreceptor cells or the function of other components of the cascade.

We first ruled out that the V303D mutation is dominant or semidominant. When V303D was expressed in the wild-type background, using the GMR promoter, we did not observe any discernible visual defect. This was also the case when we raised the relative level of V303D protein further by lowering the wild-type dosage of Gαq with heterozygous Gαq deficiencies. In other words, eyes hemizygous for Gαq and expressing gmr-V303D are normal under our experimental conditions. Therefore, V303D is highly unlikely to be dominant to the wild-type allele.

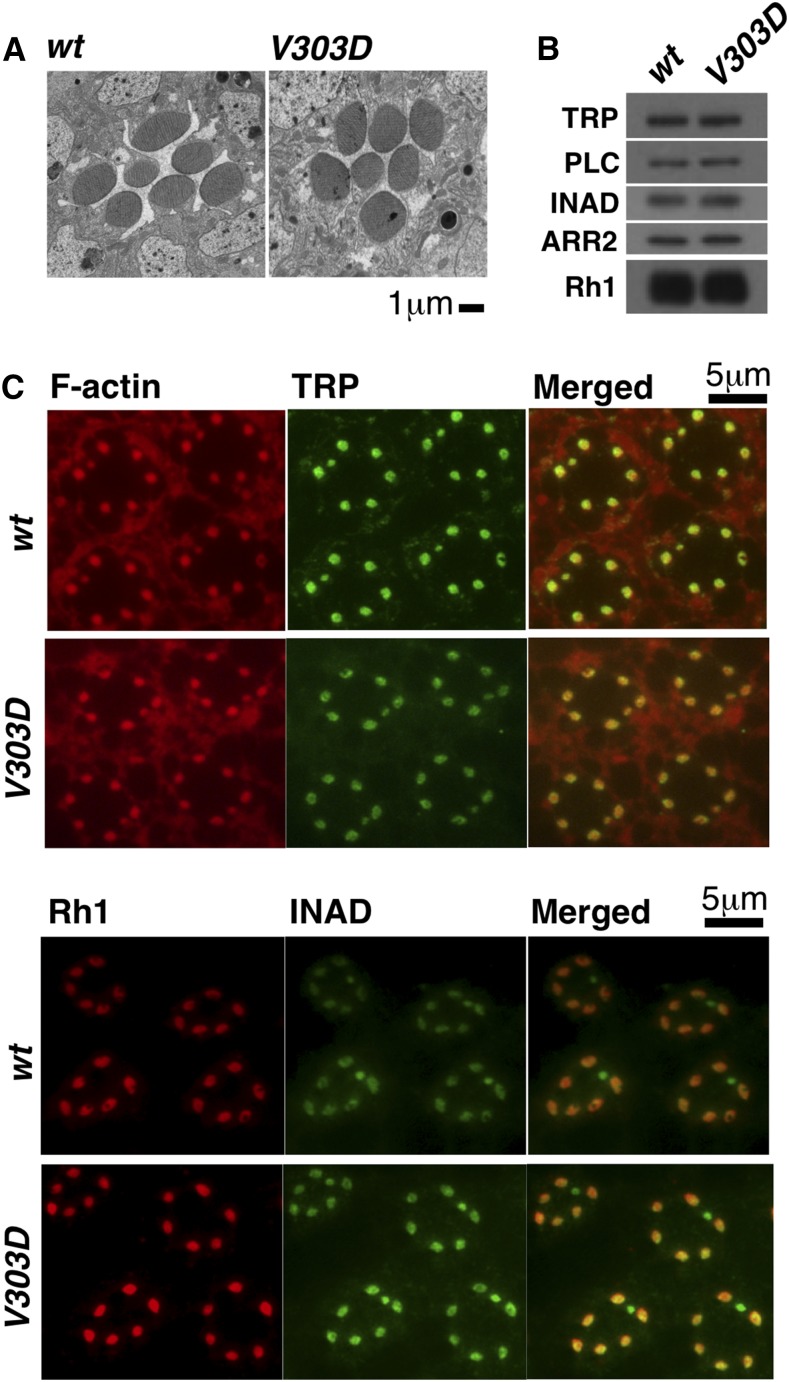

To assess the integrity of other components of the cascade, we checked the structure of photoreceptor cells by EM, the localization of Rh1, TRP, and INAD proteins by immunostaining, and the level of Rh1, TRP, INAD, PLC, and ARR2 proteins by Western blot analysis. To eliminate the secondary effect of degenerated retinal structure suffered by older V303D eyes, our analyses were performed on samples taken from 1-d-old adults, when the overall eye structural remains normal (Figure 4A). As shown in Figure 4, B and C, neither the localization nor the expression level of the various protein components of the phototransduction cascade were altered by the V303D mutation. Therefore, the mutation affects Gαq specifically.

Figure 4.

Normal rhabdomere structure and distribution of other visual factors in GαqV303D mutant. (A) EM images of 1-d-old wild-type and GαqV303D eyes showing normal rhabdomere structure. (B) Western blot results showing protein levels of phototransduction factors are similar between wild type and V303D mutants that were 1 d old. (C) Immunostaining results showing normal distribution of phototransduction factors in GαqV303D mutant flies. The complete genotypes are as follows: w1118 (wt); w1118; GαqV303D (V303D).

The V303D mutation might disrupt the interaction between Gαq and PLC

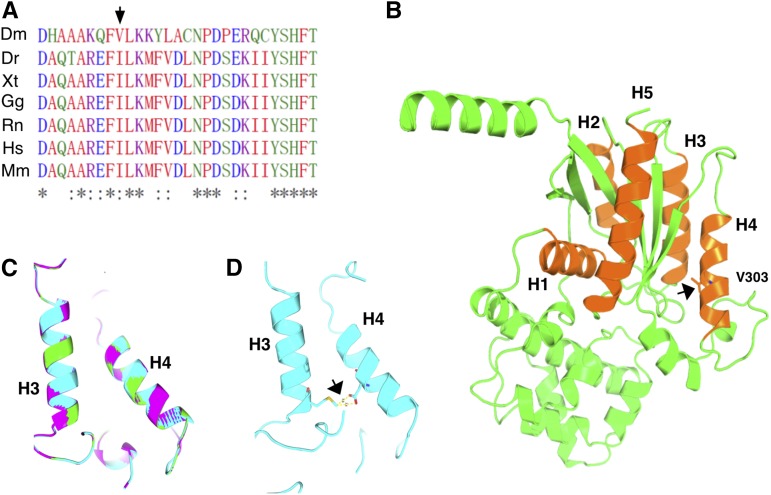

An alignment of the Gαq proteins from various organisms revealed that the V303 residue lies in an important region of Gαq proteins (Figure 5A). Structural analyses of the Gα proteins with regards to its interaction with PLC identified the V303 region as the interface between the two proteins (Noel et al. 1993; Lambright et al. 1994, 1996; Alvarez et al. 1996). Interestingly, Gαq proteins in higher eukaryotes exhibit isoleucine at the position equivalent to the valine residue in the fly protein (Figure 5A), with both being hydrophobic. It is conceivable that the change of a hydrophobic residue to a polar one (D in the V303D mutant) can exert a large effect on the interaction between the two proteins. Consistent with this hypothesis, we were able to rescue the visual defects associated with V303D when we expressed a V303I variant of the fly protein (Figure 2C). We modeled the mutant protein using published structures of Gαq proteins. As shown in Figure 5C, neither the V to D nor the V to I change would lead to a dramatic change of the three-dimensional structure of Gαq. The V303 residue is situated in helix 4 of Gα (Figure 5B). Interestingly, our structural model predicts that the side chains of a mutant Asp at position 303 would be in close proximity with Met at 242 in helix 3, another part of Gαq important for PLC interaction. The two residues might form hydrogen bonding, potentially affecting the Gαq–PLC interaction (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

The molecular model of the V303D protein. (A) Alignment of the V303 region in Gαq proteins. The V303 residue is labeled with an arrow. (B) The structure of Gαq modeled over known Gα structures, with the helices (H) involving in interaction with GPCR and PLC labeled in numbers. V303 is situated on helix 4, with its side chains shown and highlighted with an arrow. Helices 3 and 4 participate in interacting with PLC. (C) The predicted structures of helices 3 and 4 in wild type Gαq (green), GαqV303I (purple), and GαqV303D (cyan) proteins are overlaid to highlight a lack of major structural disruption of the V303D mutation. (D) In V303D, the side chain of the D303 mutant residue might participate in hydrogen bonding with M242 on helix 3 as indicated by the arrow. Dm, Drosophila melanogaster; Dr, Danio rerio; Gg, Gallus gallus; Hs, Homo sapiens; Mm, Mus musculus; Rn, Rattus norvegicus; Xt, Xenopus tropicalis.

Therefore, the defect of V303D could simply be that the mutant Gαq protein is unable to interact with and hence activate PLC. We attempted to use immunoprecipitation to investigate Gαq-PLC interaction. However, we were unable to detect association even under the wild-type condition. Nevertheless, the above hypothesis predicts that the lack of a photo response is simply due to the inability of the mutant protein to relay the signal, and that the downstream cascade should be functional in GαqV303D mutant. Our prior results showing normal expression level and localization of other components of the phototransduction cascade is consistent with this hypothesis (Figure 4).

To gain further evidence that the cascade was otherwise intact, we used whole-cell recording to investigate photoreceptor integrity and whether the function of the TRP channels is normal in the mutant eye. Consistent with our ultrastructural (EM) studies, dissociated ommatidia from V303D mutants appeared normal in appearance. Whole-cell recordings showed no sign of constitutive channel activity and cells had capacitances (59.8 ± 2.2 pF; n = 15), similar to wild-type and essentially identical to that in Gαq1 mutant (58.4 ± 3.1 pF; n = 8), indicating that the area of microvillar membrane was unaffected. Interestingly, under whole-cell recording conditions, most V303D mutant photoreceptors did display a slight response to very bright light stimuli, but with an ∼10-fold reduced sensitivity compared with the Gαq1 mutant (Figure 6). The kinetics and channel noise of these residual response were similar to those in Gαq1, suggesting that downstream components (PLC and TRP/TRPL channels) were functioning normally. Whether these responses were due to minimal residual function of the V303D mutant or an alternative G protein isoform is unclear.

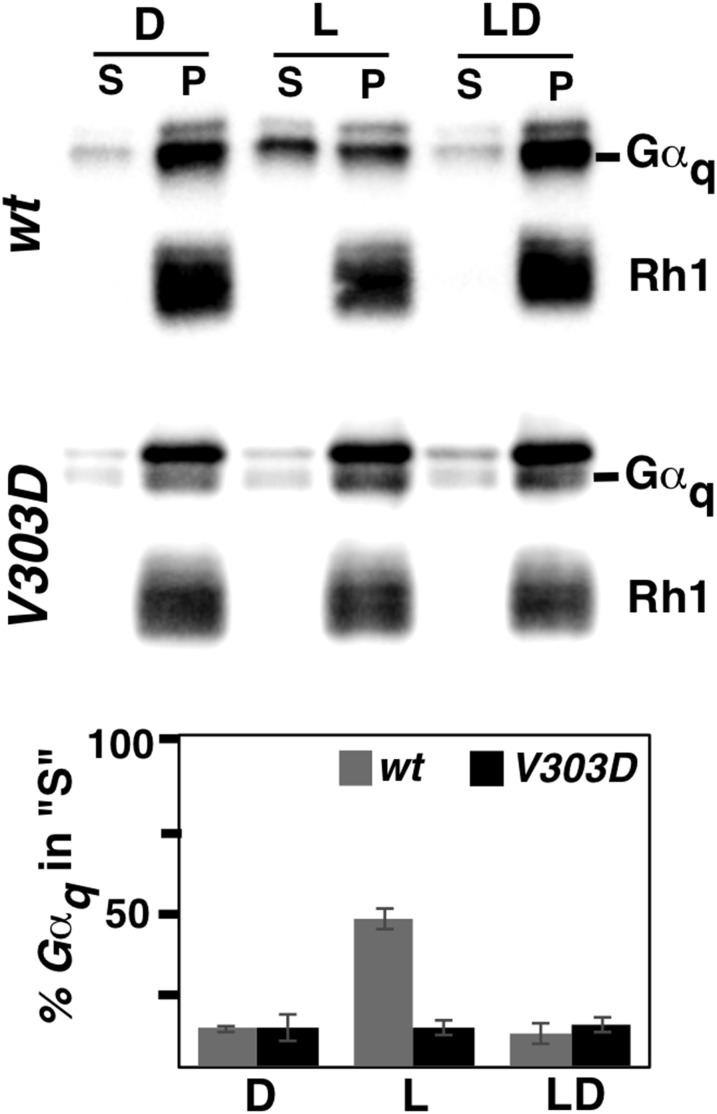

Impaired long-term adaptation in the V303D mutant

In addition to responding to light stimuli, Drosophila eyes have the ability to adapt to maintained illumination. Gαq also participates in this long-term adaptation by shuttling between the cell membrane and the cytoplasm (Cronin et al. 2004; Frechter and Minke 2006). Under normal conditions, constant light stimulation results in the relocation of Gαq to the cytoplasm, to prevent overactivation of the visual system (Kosloff et al. 2003). Upon termination of light stimulation, Gαq returns to the membrane (Frechter et al. 2007). As shown in Figure 7, we were able to recapitulate this shuttling in wild-type eyes exposed to 2 hr of light stimulation. On the other hand, the V303D mutant protein was unable to relocate to the cytoplasm upon a similarly long exposure to light, suggesting that the GαqV303D mutant is defective in long-term adaptation. However, we cannot rule out that the inability of the mutant protein to relocate is due to the lack of a photo response (i.e., the light response is epistatic to the adaptation), even though we showed that the Rh1 receptor appears expressed and localized normally in the mutant (Figure 4).

Figure 7.

The GαqV303D protein is defective in cytoplasmic translocation induced by constant light stimulation. Wild-type and V303D mutant flies were each separated into three groups and treated differently (for treatment details see Materials and Methods). Supernatant (S) and membrane pellet (P) fractions of treated fly heads were subjected to Western blotting analyses, with Rh1 serving as a protein control for the membrane fraction (P). Quantification of the percentage of Gαq protein in the cytoplasm is shown below. The complete genotypes are as follows: w1118 (wt); w1118; GαqV303D (V303D).

Discussion

In this study, we characterized a novel allele of the Drosophila Gαq gene. The mutant protein produced by this new allele possesses a single amino acid change from the wild-type version of an eye-specific isoform, yet it produces the strongest visual defects of all known Gαq mutants.

We suggest that the GαqV303D protein might have only affected the visual pathway at the level of the Gαq–PLC interaction. By Western blot and immunostaining analyses, we showed that key components of the phototransduction pathway are normal both at the protein level and at the subcellular localization level. In addition, the functional integrity of the remaining pathway is indicated by the normal kinetics of the residual light response in whole-cell recordings from mutant photoreceptors.

Structural studies suggest that the Val residue, which is mutated to Asp in our mutant, constitutes part of the interaction interface between Gα and its downstream effector. Interestingly, Val is replaced with Ile in Gαq proteins from vertebrates, yet the hydrophobicity at this position is evolutionally conserved. Val and Ile appear interchangeable for Drosophila visual transduction, as the GαqV303I variant is functional under the conditions of our assays (Figure 2C). Therefore, it is highly likely that the change to a polar residue in V303D causes a major disruption of the interaction between Gαq and its downstream effector, which in the case of Drosophila visual transduction is the PLC enzyme. The model that V303D loses its ability to activate PLC predicts that GαqV303D would behave similarly to a norpA mutant with regard to the visual phenotypes. This is supported by existing data. First, norpA is one of very few mutants that produce a flat ERG response similarly to our Gαq mutant. Second, the V303D mutant phenocopies a norpA mutant in having the fastest rate of retinal degeneration induced by light.

Nevertheless, GαqV303D behaves differently from a norpA mutant in one aspect. GαqV303D protein is defective in relocation to the membrane during prolonged exposure to lights, whereas Gαq proteins in a norpA mutant behave normally (Kosloff et al. 2003; Cronin et al. 2004). Because the absence of PLC does not affect Gαq’s relocation behavior, the molecular defect in GαqV303D must also prevent its translocation to the cytoplasm upon constant light exposure. As shown by others (Kosloff et al. 2003; Cronin et al. 2004), this dynamic relocation to the cytoplasm appears to be affected only by the state of Rh1. Importantly, none of the downstream components of the signaling pathway is important to regulate the membrane-to-cytoplasm dynamics of Gαq, although the NinaC myosin III has a role in promoting the cytoplasm-to-membrane movement of Gαq (Cronin et al. 2004). This would appear to imply that the GαqV303D is also defective in its functional interaction with Rh1. However, our structural modeling suggests that this is unlikely to be the case. As shown in Figure 5, the V303D change might not have altered the overall structure of Gαq including the regions important for GPCR interaction: helices 1 and 5. Therefore, the V303D mutant protein might be intrinsically defective in this membrane to cytoplasm shuttling. Further work is required to distinguish these possibilities.

In summary, we have recovered a new point mutation of the important Gαq protein that essentially abolishes the visual transduction pathway in Drosophila. It also leads to one of the fastest rates of retinal degeneration induced by light. Although the molecular lesion lies in the interaction interface between Gαq and its effector, functional characterization suggests that the mutant protein might harbor additional molecular defects. Therefore, our work reveals additional complexity in the regulation of G protein functions and generates a potential useful reagent for fine structural and functional studies of Gαq in diverse organisms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Junhai Han of Southeast University, China, in whose laboratory this work was initiated. We thank members of the Rong and Hardie laboratories for technical assistance and comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China (grant 201707010022 to W.H.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 31660331 and 31460299 to J.C., 31601162 to W.H., and 31371364 to Y.S.R.), National Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi province, China (grant 20151BAB214012 to J.C.), and Scientific Research Fund of Jiangxi Province Education Department (grant GJJ160728 to Y.H.). R.C.H. and M.K.B. are supported by a grant from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC grant BB/M007006/1).

Footnotes

Communicating editor: B. Reed

Literature Cited

- Alvarez C. E., Robison K., Gilbert W., 1996. Novel Gq alpha isoform is a candidate transducer of rhodopsin signaling in a Drosophila testes-autonomous pacemaker. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93: 12278–12282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arshavsky V., Bownds M. D., 1992. Regulation of deactivation of photoreceptor G protein by its target enzyme and cGMP. Nature 357: 416–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campden R., Audet N., Hebert T. E., 2015. Nuclear G protein signaling: new tricks for old dogs. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 65: 110–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook B., Bar-Yaacov M., Cohen Ben-Ami H., Goldstein R. E., Paroush Z., et al. , 2000. Phospholipase C and termination of G-protein-mediated signalling in vivo. Nat. Cell Biol. 2: 296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin M. A., Diao F., Tsunoda S., 2004. Light-dependent subcellular translocation of Gqα in Drosophila photoreceptors is facilitated by the photoreceptor-specific myosin III NINAC. J. Cell Sci. 117: 4797–4806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frechter S., Minke B., 2006. Light-regulated translocation of signaling proteins in Drosophila photoreceptors. J. Physiol. Paris 99: 133–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frechter S., Elia N., Tzarfaty V., Selinger Z., Minke B., 2007. Translocation of Gqα mediates long-term adaptation in Drosophila photoreceptors. J. Neurosci. 27: 5571–5583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Marcos M., Ghosh P., Farquhar M. G., 2009. GIV is a nonreceptor GEF for Gαi with a unique motif that regulates Akt signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106: 3178–3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Gong P., Reddig K., Mitra M., Guo P., et al. , 2006. The fly CAMTA transcription factor potentiates deactivation of rhodopsin, a G protein-coupled light receptor. Cell 127: 847–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie R. C., Franze K., 2012. Photomechanical responses in Drosophila photoreceptors. Science 338: 260–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie R. C., Minke B., 1992. The trp gene is essential for a light-activated Ca2+ channel in Drosophila photoreceptors. Neuron 8: 643–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie R. C., Gu Y., Martin F., Sweeney S. T., Raghu P., 2004. In vivo light-induced and basal phospholipase C activity in Drosophila photoreceptors measured with genetically targeted phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate-sensitive ion channels (Kir2.1). J. Biol. Chem. 279: 47773–47782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris W. A., Stark W. S., 1977. Hereditary retinal degeneration in Drosophila melanogaster. A mutant defect associated with the phototransduction process. J. Gen. Physiol. 69: 261–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt J. D., Sekura R. D., Codina J., Iyengar R., Manclark C. R., et al. , 1983. Stimulation and inhibition of adenylyl cyclases mediated by distinct regulatory proteins. Nature 302: 706–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollinger S., Hepler J. R., 2002. Cellular regulation of RGS proteins: modulators and integrators of G protein signaling. Pharmacol. Rev. 54: 527–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W., Wan D., Yu X., Cao J., Guo P., et al. , 2012. Protein Gq modulates termination of phototransduction and prevents retinal degeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 287: 13911–13918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W., Wang T., Wang X., Han J., 2015. Ih channels control feedback regulation from amacrine cells to photoreceptors. PLoS Biol. 13: e1002115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly P., Stemmle L. N., Madden J. F., Fields T. A., Daaka Y., et al. , 2006. A role for the G12 family of heterotrimeric G proteins in prostate cancer invasion. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 26483–26490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Chen D. M., Zavarella K., Fourtner C. F., Stark W. S., et al. , 2003. Substitution of a non-retinal phospholipase C in Drosophila phototransduction. Insect Mol. Biol. 12: 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiselev A., Subramaniam S., 1994. Activation and regeneration of rhodopsin in the insect visual cycle. Science 266: 1369–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosloff M., Elia N., Joel-Almagor T., Timberg R., Zars T. D., et al. , 2003. Regulation of light-dependent Gqα translocation and morphological changes in fly photoreceptors. EMBO J. 22: 459–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaLonde M. M., Janssens H., Rosenbaum E., Choi S. Y., Gergen J. P., et al. , 2005. Regulation of phototransduction responsiveness and retinal degeneration by a phospholipase D-generated signaling lipid. J. Cell Biol. 169: 471–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambright D. G., Noel J. P., Hamm H. E., Sigler P. B., 1994. Structural determinants for activation of the alpha-subunit of a heterotrimeric G protein. Nature 369: 621–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambright D. G., Sondek J., Bohm A., Skiba N. P., Hamm H. E., et al. , 1996. The 2.0 A crystal structure of a heterotrimeric G protein. Nature 379: 311–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. J., Dobbs M. B., Verardi M. L., Hyde D. R., 1990. dgq: a drosophila gene encoding a visual system-specific G alpha molecule. Neuron 5: 889–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. J., Shah S., Suzuki E., Zars T., O’Day P. M., et al. , 1994. The Drosophila dgq gene encodes a Gα protein that mediates phototransduction. Neuron 13: 1143–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung H. T., Geng C., Pak W. L., 2000. Phenotypes of trpl mutants and interactions between the transient receptor potential (TRP) and TRP-like channels in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 20: 6797–6803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung H. T., Tseng-Crank J., Kim E., Mahapatra C., Shino S., et al. , 2008. DAG lipase activity is necessary for TRP channel regulation in Drosophila photoreceptors. Neuron 58: 884–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masai I., Suzuki E., Yoon C. S., Kohyama A., Hotta Y., 1997. Immunolocalization of Drosophila eye-specific diacylgylcerol kinase, rdgA, which is essential for the maintenance of the photoreceptor. J. Neurobiol. 32: 695–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay R. R., Chen D. M., Miller K., Kim S., Stark W. S., et al. , 1995. Phospholipase C rescues visual defect in norpA mutant of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 13271–13276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell C., Rubin G. M., 1989. Molecular characterization of the Drosophila trp locus: a putative integral membrane protein required for phototransduction. Neuron 2: 1313–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neer E. J., 1995. Heterotrimeric G proteins: organizers of transmembrane signals. Cell 80: 249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves S. R., Ram P. T., Iyengar R., 2002. G protein pathways. Science 296: 1636–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel J. P., Hamm H. E., Sigler P. B., 1993. The 2.2 A crystal structure of transducin-alpha complexed with GTP gamma S. Nature 366: 654–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham W. M., Hamm H. E., 2008. Heterotrimeric G protein activation by G-protein-coupled receptors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9: 60–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popescu D. C., Ham A. J., Shieh B. H., 2006. Scaffolding protein INAD regulates deactivation of vision by promoting phosphorylation of transient receptor potential by eye protein kinase C in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 26: 8570–8577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghu P., Usher K., Jonas S., Chyb S., Polyanovsky A., et al. , 2000. Constitutive activity of the light-sensitive channels TRP and TRPL in the Drosophila diacylglycerol kinase mutant, rdgA. Neuron 26: 169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnaparkhi A., Banerjee S., Hasan G., 2002. Altered levels of Gq activity modulate axonal pathfinding in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 22: 4499–4508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee S. G., 2001. Regulation of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70: 281–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum D. M., Rasmussen S. G., Kobilka B. K., 2009. The structure and function of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature 459: 356–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross E. M., Wilkie T. M., 2000. GTPase-activating proteins for heterotrimeric G proteins: regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) and RGS-like proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69: 795–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Running Deer J. L., Hurley J. B., Yarfitz S. L., 1995. G protein control of Drosophila photoreceptor phospholipase C. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 12623–12628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruppel K. M., Willison D., Kataoka H., Wang A., Zheng Y. W., et al. , 2005. Essential role for Gα13 in endothelial cells during embryonic development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102: 8281–8286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott K., Becker A., Sun Y., Hardy R., Zuker C., 1995. Gqα protein function in vivo: genetic dissection of its role in photoreceptor cell physiology. Neuron 15: 919–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan D., Chen L., Wang D., Tan Y. C., Gu J. L., et al. , 2006. The G protein Gα13 is required for growth factor-induced cell migration. Dev. Cell 10: 707–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siderovski D. P., Willard F. S., 2005. The GAPs, GEFs, and GDIs of heterotrimeric G-protein alpha subunits. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 1: 51–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunahara R. K., Taussig R., 2002. Isoforms of mammalian adenylyl cyclase: multiplicities of signaling. Mol. Interv. 2: 168–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talluri S., Bhatt A., Smith D. P., 1995. Identification of a Drosophila G protein alpha subunit (dGq alpha-3) expressed in chemosensory cells and central neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92: 11475–11479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y., Li T., Sun M., Wan D., Li Q., et al. , 2013. Neurexin regulates visual function via mediating retinoid transport to promote rhodopsin maturation. Neuron 77: 311–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Montell C., 2007. Phototransduction and retinal degeneration in Drosophila. Pflugers Arch. 454: 821–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Jiao Y., Montell C., 2005a Dissecting independent channel and scaffolding roles of the Drosophila transient receptor potential channel. J. Cell Biol. 171: 685–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Xu H., Oberwinkler J., Gu Y., Hardie R. C., et al. , 2005b Light activation, adaptation, and cell survival functions of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger CalX. Neuron 45: 367–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wes P. D., Xu X. Z., Li H. S., Chien F., Doberstein S. K., et al. , 1999. Termination of phototransduction requires binding of the NINAC myosin III and the PDZ protein INAD. Nat. Neurosci. 2: 447–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon J., Ben-Ami H. C., Hong Y. S., Park S., Strong L. L., et al. , 2000. Novel mechanism of massive photoreceptor degeneration caused by mutations in the trp gene of Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 20: 649–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwaal R. R., Ahringer J., van Luenen H. G., Rushforth A., Anderson P., et al. , 1996. G proteins are required for spatial orientation of early cell cleavages in C. elegans embryos. Cell 86: 619–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The research reagents generated in this study are freely available upon request. The authors affirm that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are represented fully within the article.