Abstract

Pulmonary hypertension is characterized by pulmonary endothelial dysfunction. Previous work showed that systemic artery endothelial cells (ECs) express hemoglobin (Hb) α to control nitric oxide (NO) diffusion, but the role of this system in pulmonary circulation has not been evaluated. We hypothesized that up-regulation of Hb α in pulmonary ECs contributes to NO depletion and pulmonary vascular dysfunction in pulmonary hypertension. Primary distal pulmonary arterial vascular smooth muscle cells, lung tissue sections from unused donor (control) and idiopathic pulmonary artery (PA) hypertension lungs, and rat and mouse models of SU5416/hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension (PH) were used. Immunohistochemical, immunocytochemical, and immunoblot analyses and transfection, infection, DNA synthesis, apoptosis, migration, cell count, and protein activity assays were performed in this study. Cocultures of human pulmonary microvascular ECs and distal pulmonary arterial vascular smooth muscle cells, lung tissue from control and pulmonary hypertensive lungs, and a mouse model of chronic hypoxia-induced PH were used. Immunohistochemical, immunoblot analyses, spectrophotometry, and blood vessel myography experiments were performed in this study. We find increased expression of Hb α in pulmonary endothelium from humans and mice with PH compared with controls. In addition, we show up-regulation of Hb α in human pulmonary ECs cocultured with PA smooth muscle cells in hypoxia. We treated pulmonary ECs with a Hb α mimetic peptide that disrupts the association of Hb α with endothelial NO synthase, and found that cells treated with the peptide exhibited increased NO signaling compared with a scrambled peptide. Myography experiments using pulmonary arteries from hypoxic mice show that the Hb α mimetic peptide enhanced vasodilation in response to acetylcholine. Our findings reveal that endothelial Hb α functions as an endogenous scavenger of NO in the pulmonary endothelium. Targeting this pathway may offer a novel therapeutic target to increase endogenous levels of NO in PH.

Keywords: pulmonary hypertension, hemoglobin, endothelial nitric oxide synthase, nitric oxide, endothelial dysfunction

Clinical Relevance

Our findings reveal that endothelial hemoglobin α functions as an endogenous scavenger of nitric oxide (NO) in pulmonary endothelium. Targeting this pathway may offer a novel therapeutic target to increase endogenous levels of NO in pulmonary hypertension.

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a clinical syndrome defined by the presence of elevated pulmonary artery (PA) pressures, with a mean PA pressure greater than 25 mm Hg required for the diagnosis (1). The disease may be idiopathic, heritable, or associated with other diseases, such as systemic sclerosis (SSc) (1). Although these subgroups may have differences in disease pathogenesis, they ultimately share a vasculopathy characterized by endothelial dysfunction, excessive vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) proliferation, and proinflammatory signaling, all of which lead to artery narrowing and pruning of the pulmonary vascular tree (1, 2). As a result, patients with PH develop right-heart failure, leading to premature death, with a median survival of 2.8 years if untreated (3). The pathogenesis driving vascular dysfunction is multifactorial, and several pathways have been implicated (1, 4–12).

Nitric oxide (NO) is a critical biogas that leads to vasodilation and suppression of VSMC proliferation (1, 13, 14). In the PA and arteriole wall, NO is generated in the endothelium by endothelial NO synthase (eNOS), where it diffuses to the VSMC and binds to its receptor, soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) (13–15). Upon activation by NO, sGC catalyzes the conversion of GTP to cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), which subsequently activates cGMP-dependent protein kinase G (PKG) to elicit vasodilation and suppression of VSMC proliferation (7, 14, 16).

Despite a general consensus that impaired NO signaling characterizes PH (1, 2, 17–20), the specific mechanisms behind this NO depletion remain unclear (2). Findings reported in the literature are inconsistent, and vary with the specific patient characteristics or models used. Some studies suggest that eNOS is unregulated in PH (6, 21–23), whereas others report decreased eNOS expression (5, 24). Other proposed causes of the apparent NO depletion are eNOS uncoupling and NO scavenging via reactive oxygen species (i.e., superoxide) or reactions with cell-free hemoglobin (Hb), levels of which are increased in PH and correlate with hemodynamic severity and risk of hospitalization (25, 26).

Although Hb was previously considered a protein exclusively expressed in erythrocytes, more recent research has demonstrated that various Hb subtypes are expressed in many somatic cells, including alveolar cells (27–29). Recent work has demonstrated that Hb α, one of the constituent chains of the tetrameric protein, Hb, is expressed in systemic small arteries and arterioles, where it is enriched at the myoendothelial junction (MEJ), the point of contact between endothelial cells (ECs) and VSMCs (30). Functionally, Hb α serves to control NO diffusion from endothelium to the vascular smooth muscle via its heme iron redox state (30). In the presence of oxygen, ferrous oxyhemoglobin α rapidly catalyzes a dioxygenation reaction with NO and O2, creating as its product, NO3−.

The rate constant for this reaction is approximately 6–8 × 107 M−1 s−1, making Hb α a functional sink for NO (31). The coupling of Hb α with eNOS was found to be critical for its scavenging function in EC, and inhibition of this association with a novel peptide Hb α mimetic, “Hb α X,” increased endothelial-dependent NO signaling (32). This Hb α–eNOS axis has been demonstrated to play a significant role in normal vascular function in the systemic circulation (33).

Although it is clear that Hb α is expressed in the systemic vasculature and alveolar epithelium, whether Hb α is expressed in the pulmonary circulation remains unknown (34). When compared with both disease-free control subjects and subjects with SSc without PH, gene expression profiles of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patients with idiopathic PA hypertension and PH associated with SSc (SSc-PH) demonstrated increased expression of genes associated with erythroid differentiation, including HBA2. In patients with idiopathic PA hypertension, these gene expression changes directly correlate with the hemodynamic severity of disease (35). Interestingly, these erythroid-specific PBMC gene expressions were present in SSc-PH, but did not correlate with hemodynamic severity, possibly due to differences in the underlying disease pathophysiology. This erythroid differentiation gene signature distinguished between the subjects with and without PH in this study. Although these gene expression changes were thought to be restricted to cell types of hematopoietic lineage, it is also possible that they were demonstrating transcriptional changes in the endothelial progenitor cells captured within PBMC studies (36), and may indicate transcriptional changes within the pulmonary vasculature as well.

For these reasons, we hypothesized that up-regulation of Hb α may contribute to the depletion of the NO signaling pathway in PH. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine the pattern and functional consequences of Hb α expression in the setting of normal pulmonary physiology and in human and animal models of PH.

Materials and Methods

Human Tissues

The use of human pulmonary tissues was conducted under the University of Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh, PA) Institutional Review Board protocols (970,946 and PRO14010265), and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Pulmonary arteries were rinsed with PBS. After rinsing, artery segments to be used for immunofluorescence were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and paraffin embedded. Artery segments to be used for Western blots and spectrophotometry were further processed to lyse red blood cells in a protocol modified from Grek and colleagues (28). Briefly, the arteries were incubated for 5 minutes in red blood cell lysis buffer (BioLegend, San Diego, CA), rinsed in PBS, and then snap frozen. Tissues were homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer before further experiments.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of the Human Subjects Whose Samples Were Used in the Experiments

| Subject ID | Diagnosis | WHO Group | Age (Yr) | Sex | RA Mean (mm Hg) | PA Pressure (Systolic/Diastolic) (mm Hg) | Mean PA (mm Hg) | PCWP (mm Hg) | TPG (mm Hg) | |

|

PVR (Wood Units) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fick CO(L/min) | Fick CI(L min−1m−2) | Experiments | |||||||||||

| 1 | Systemic sclerosis | Group I | 55 | F | 10 | 60/22 | 38 | 7 | 31 | 5.4 | 2.67 | 5.7 | Immunofluorescence |

| 2 | COPD | Group III | 45 | M | 9 | 53/21 | 33 | 9 | 24 | 4.14 | 3.06 | 5.8 | Immunofluorescence |

| 3 | Repaired congenital heart disease | Group I | 50 | F | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Immunofluorescence; PA homogenate |

| 4 | Systemic sclerosis | Group I | 51 | F | 11 | 90/25 | 53 | 13 | 40 | 4.3 | 2.6 | 9.3 | PA homogenate |

| 5 | Systemic sclerosis | Group I | 43 | F | 2 | 46/24 | 31 | 8 | 23 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 6.1 | PA homogenate |

| 6 | Systemic sclerosis | Group I | 66 | F | 9 | 67/30 | 44 | 10 | 34 | 3.8 | 2.08 | 8.9 | PA homogenate |

| 7 | Interstitial lung disease | Group III | 55 | M | 5 | 54/24 | 36 | 11 | 25 | 4.21 | 2.09 | 5.9 | PA homogenate |

| 8 | Repaired congenital heart disease | Group I | 37 | F | 19 | 128/56 | 85 | 12 | 73 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 17.4 | PA homogenate |

| 9 | Control | 52 | F | PA homogenate | |||||||||

| 10 | Control | 69 | F | PA homogenate | |||||||||

| 11 | Control | 35 | M | PA homogenate | |||||||||

| 12 | Control | 64 | F | Immunofluorescence | |||||||||

| 13 | Control | 46 | M | Immunofluorescence | |||||||||

| 14 | Control | 43 | M | Immunofluorescence | |||||||||

| Mean ± SD | 50.8 ± 10.3 | 9.29 ± 5.31 | 45.7 ± 18.8 | 10 ± 2.2 | 35.7 ± 17.5 | 4.26 ± 0.5 | 2.44 ± 0.36 | 8.45 ± 4.2 |

Definition of abbreviations: CI, cardiac index; CO, cardiac output; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PA, pulmonary artery; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RA, right atrial pressure; TPG, transpulmonary gradient; WHO, World Health Organization.

Right-heart catheterization data for this subject were not available.

Animals

Male C57BL/6N mice (8–10 wk of age) were purchased from Taconic Farms (Hudson, NY) and housed according to the University of Pittsburgh Animal Care and Use Committee Guidelines. Separate groups of mice (n = 5–6 per experiment) were exposed to either room air or chronic normobaric hypoxia with 10% oxygen for 3 weeks. Animals, the lungs of which were to be analyzed by microscopy, were anesthetized with isoflurane and perfused with heparin and saline to remove erythrocytes from the lungs, and then killed. Animals, the vessels of which were to be used for myography, were killed before rapidly harvesting tissues for further experiments.

Hemodynamics and Fulton Index Measurements

Hemodynamics were assessed using a closed-chest technique, as previously described (37). After the animals were perfused with saline and killed, the heart and lung tissues were harvested. Atria were trimmed, and the right ventricle (RV) was dissected from the left ventricle and septum. RV hypertrophy was determined by the ratio of the weight of the RV to the left ventricle plus septum.

Myography

PA myography was performed as previously described, with modifications (38). Second-order pulmonary arteries were harvested and prepared, then placed on the Multi Wire Myograph System (620M; DMT, Aarhus, Denmark). Rings were incubated with 5 μM of either Hb α X peptide or the scrambled control peptide. Segments were contracted with a continuous dose response of prostaglandin F2α (1–50 μM). After reaching plateau, endothelial function was examined by generating a cumulative dose–response curve of acetylcholine (ACh) (log M [10−8–10−5]). KCl (80 mM) was added to confirm viability, and was followed by Ca2+-free physiological salt solution containing 100 μM sodium nitroprusside for maximal dilation.

Cell Culture

Human pulmonary VSMCs were isolated and cultured as previously described (39). Human pulmonary microvascular ECs were purchased from Lonza (Basel, Switzerland) and cultured in endothelial basal medium-2 media with microvascular EC bullet kit (Lonza). Cells between passages 4 and 8 were used for experiments. For coculture studies, cells were cultured on Transwells, as previously described (40). For the no-touch coculture experiments, the procedure was modified such that the VSMCs were cultured on the bottom of the six-well dish, rather than on the Transwell insert, and cultured for 24 hours before any further experiments. For hypoxia experiments, cells underwent further culture in either normoxic (21% O2, 5% CO2) or hypoxic (1% O2, 5% CO2) conditions for 48 hours before stimulation or harvesting. For “physioxia” experiments, cells were cultured at an oxygen concentration approximating the oxygen tension present in the normal human pulmonary circulation (5% O2, 5% CO2) (41). For stimulation experiments, ECs were pretreated with scrambled control or Hb α X peptide (5 μM, 30 min), and VSMCs were pretreated for 15 minutes with sildenafil (10 μM, 15 min). After pretreatment with peptides and sildenafil, EC were stimulated with bradykinin (10 μM, 30 min) before harvesting. For the cobalt chloride experiments, ECs were first cultured to 80% confluence and treated with CoCl2 at concentrations of either 100 μM or 500 μM for 24–48 hours. Cell fractions from the EC layer, MEJs, and VSMC layer were harvested as previously described (30).

Western Blot

Immunoblots were performed as previously described (42, 43).

Immunofluorescence

Paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned, placed on glass, and deparaffinized in xylene, followed by rehydration in decreasing concentrations of ethanol (100, 90, and 70%) and water. Samples were boiled for 30 minutes in Antigen Unmasking solution (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Tissues were blocked in 1% BSA and 3 g/500 ml fish skin gelatin in PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature, and then incubated overnight in primary antibodies against Hb α (1:50) and eNOS (1:50) at 4°C. Slides were washed with PBS/Tween-20 (0.1%) and incubated in Alexa Fluor–conjugated secondary antibodies (1:250) and a FITC-conjugated antibody against smooth muscle α-actin (1:500). Specimens were imaged using an Olympus confocal laser-scanning microscope (Fluoview 1,000; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) at 20× and 40× magnifications. Fluorescence intensity was quantified, using NIS Elements software (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), by manually selecting a region of interest over the endothelium and measuring mean fluorescence intensity. Colocalization was assessed using Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), where the Manders’ coefficient was calculated after determining the autothreshold using the Costes method with the Coloc 2 plugin, as previously described (44).

Spectrophotometry

Light scatter immune spectrophotometry was conducted as previously described (42). Briefly, lysates from control, PH, and SSc-PH were isolated in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer and 50 μg of protein were placed into a cuvette and into an Olis Rapid Scanning Spectrophotometer (Olis, Inc., Atlanta, GA). Spectra measurements were made between 450 and 750 nm. Visible Q band peaks at 545 and 580 nm were consistent with Hb spectra and considered positive for Hb.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

After exposure to either ambient oxygen or 3 weeks of normobaric hypoxia (10% O2), mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and killed by asphyxia. Lungs were perfused with heparin/PBS, followed by 2 ml of Karnovsky fixative at a rate of roughly 1 ml/min through the RV. The lungs were excised and incubated overnight at 4°C in Karnovsky solution. Samples were processed as previously described for transmission electron microscopy (45). Images of arterioles were taken with a JEOL JEM 1,210 transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Images were taken at ×15,000 magnification.

MEJ Quantification

MEJ numbers were quantified by tracing along the pulmonary arteriolar endothelial basal lateral membrane to calculate distance using Image J software, followed by counting of cellular EC extensions that came within 250 nm of the adjacent smooth muscle cell, which were considered MEJs. The number of MEJs counted was divided by distance to determine number of MEJs per 10 μm.

Statistical Analysis

Immunoblots were analyzed using Image Studio Lite Version 4.0 (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). Hemodynamic and morphometric data using Indus Instruments (Webster, TX), IOX2 (Emka Technologies, Paris, France), Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA), NIS Elements software (Nikon), and ImageJ. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 6.0 d for Windows, (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Data were analyzed using either t test, Mann–Whitney U Test, or the two-way or one-way ANOVA for repeated measures, as appropriate. The specific statistical tests used are presented below relevant figures. A difference with a P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Pulmonary Arteries from Humans and Mice with PH Demonstrate Increased Hb α Expression

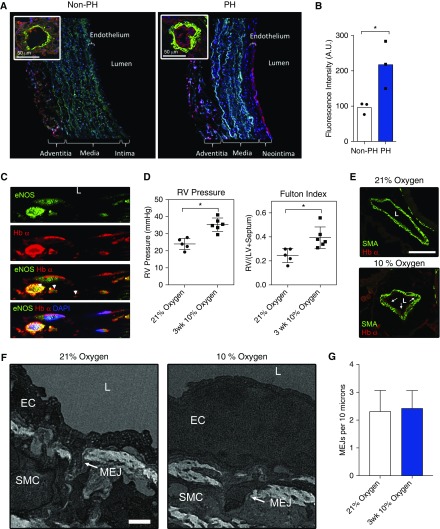

We performed immunofluorescence staining for Hb α and visualized expression patterns using laser confocal microscopy on distal (fifth-order) pulmonary arteries and arterioles (∼50 μm) isolated from humans with and without PH (Table 1). Subjects were mainly women with an average age of 50 years. We included patients with PH from different underlying etiologies, including SSc, repaired congenital heart disease, and chronic lung disease. As shown in Figure 1A, there was little Hb α within the ECs, and some within the surrounding adventitia. However, we found that the intensity of endothelial Hb α staining was significantly higher in the subjects with PH (Figures 1A and 1B). We also costained for eNOS and observed that Hb α colocalized with eNOS (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Hemoglobin (Hb) α is expressed in pulmonary arteries of humans and mice with pulmonary hypertension (PH). (A) Immunofluorescence for Hb α (red), nuclei (blue), and smooth muscle α-actin (green) from normal and PH human fifth-order pulmonary arteries and arterioles (inset). (B) Quantification of Hb α immunofluorescence intensity in the endothelium from normal and PH pulmonary arteries (n = 3). (C) Immunofluorescence staining of Hb α (red), endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase (eNOS; green), and nuclei (blue) from a human pulmonary artery (PA) with PH. Arrowheads point to colocalization between eNOS and Hb α. Manders’ coefficients were 0.441 and 0.596 for eNOS and Hb α, respectively. (D) Measurement of the right ventricle (RV) pressure and Fulton index (RV / [LV + S]), where LV is left ventricle and S is septum, from mice exposed to 21 or 10% oxygen (n = 5). (E) Immunofluorescence staining for Hb α (red) and smooth muscle α-actin (green) from mice exposed to 21% oxygen, or 10% oxygen. Arrows point to Hb α expression in the endothelium. (F) Transmission electron micrograph images of myoendothelial junctions (MEJs) from arterioles in mice exposed to normoxic and hypoxic (3 wk, 10% fraction of inspired oxygen) conditions and (G) quantification of the number of MEJs per 10 μm in each condition. Error bars represent ±SEM. *P < 0.05 using a Student’s test (B, D, and G). Scale bars: 50 μm (A), 100 μm (E), and 0.5 μm (F). L, lumen (C, E, and F). A.U., arbitrary units; EC, endothelial cell; SMA, smooth muscle actin; SMC, smooth muscle cell.

To determine whether the changes in Hb α expression observed in humans with PH were also present in animal models of PH, we compared the immunofluorescence against Hb α in the lungs of mice exposed to normal oxygen conditions (21% oxygen) and those to 3 weeks of hypoxia (10% oxygen). At the end of 3 weeks, mice exposed to hypoxia had typical changes of increased RV pressures and hypertrophy (Figure 1D). Immunofluorescence from the lungs of the mice exposed to hypoxia demonstrated greater Hb α intensity than those exposed to normal oxygen levels (Figure 1E). However, the increase in Hb α expression was not due to an increase in MEJ numbers (Figures 1F and 1G). These findings demonstrate that PA ECs from mice with experimental PH up-regulate Hb α independent of the number of MEJs.

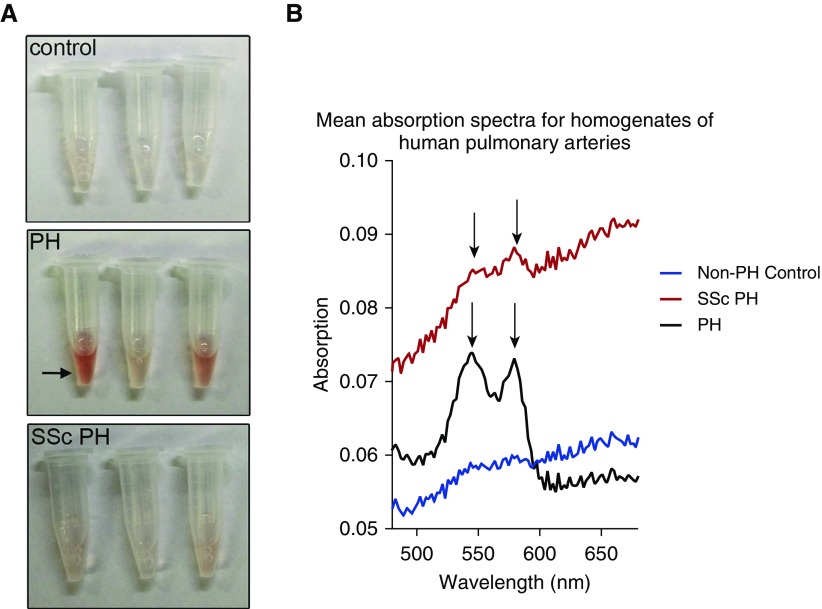

To further confirm the expression of Hb within the human tissues and evaluate the relative expression of Hb α, we also prepared tissue homogenates of the isolated pulmonary arteries and assessed them by spectrophotometry and Western blot. Given the enrichment of subjects with SSc-PH at our center, the heterogeneity of the underlying etiology of PH in our other subjects, and the published differences in erythroid differentiation gene signatures between subjects with SSc-PH (35), we subdivided our analysis between SSc and other causes of PH. The PA homogenates from subjects with PH were visibly pink when compared with those from subjects without PH (Figure 2A). The light scatter immune spectrophotometry spectra from subjects with PH had a pattern typical of oxyhemoglobin (46) (Figure 2B), with Q band peaks at approximately 545 and 580 nm (arrows). The subgroup of subjects with SSc-PH also demonstrated peaks in those regions, though they were somewhat less distinct than those from the other PH subjects. Subjects without PH had no clear peaks, consistent with a lack of abundant Hb in those homogenates.

Figure 2.

Spectrophotometry analyses of PA lysates from control, PH, and systemic sclerosis (SSc) PH. (A) Image of test tubes containing human PA lysates from control, PH, and SSc PH. Arrow points to pink lysate in the PH sample. (B) Mean absorption spectra taken using light scatter immune spectrophotometry from homogenates isolated from human control, PH, and SSc PH PAs. Arrows point to the Q bands indicative of Hb spectra.

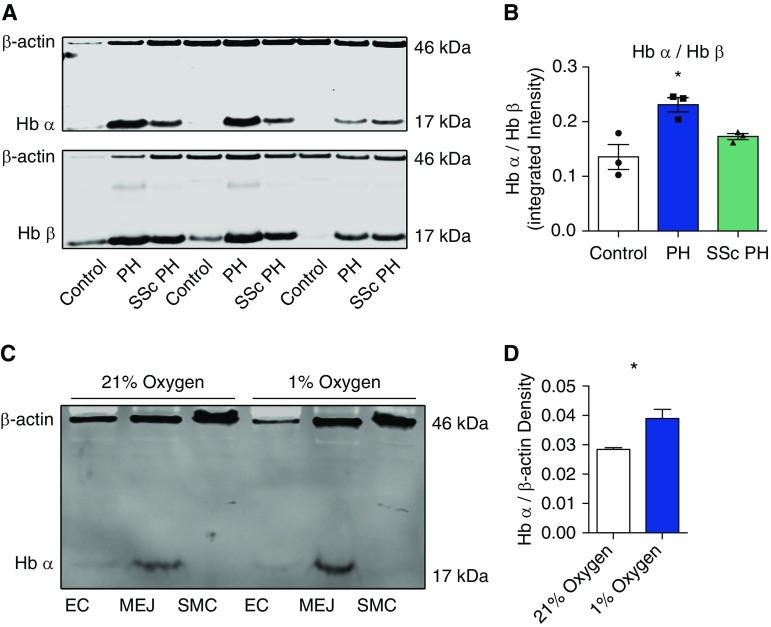

Finally, we performed Western blot with antibodies against Hb α and Hb β on the tissue homogenates from the same vessels in the spectrophotometry experiments. Although Hb α is known to be expressed in the vascular wall, vascular Hb β is negligible (30, 33). In the absence of thalassemia, erythrocytes typically express equimolar concentrations of Hb α and Hb β. We thus compared the ratios of the Hb α and Hb β, assuming that differences between groups would be due to vascular wall expression of Hb α. We found significantly higher expression of Hb α within the pulmonary arteries of subjects with PH compared with subjects with no PH (Figure 3A). There was no significant difference in Hb α expression between subjects with PH due to SSc and those due to other causes. These data suggest that pulmonary arteries from subjects with PH demonstrate increased levels of Hb α expression.

Figure 3.

Western blot analysis of Hb expression from human PAs and in a pulmonary vascular cell coculture model. (A) Western blot for Hb α, Hb β, and β-actin protein expression from control, PH, and SSc PH. (B) Quantification of ratio of Hb α and Hb β (n = 3). (C) Western blot for Hb α and β-actin expression from PA ECs, MEJ, and vascular SMC (VSMC) fractions from cells cocultured on Transwells and exposed to 1% hypoxia for 48 hours. (D) Quantification of Hb α protein expression from the MEJ fraction of cocultured pulmonary ECs and VSMCs exposed to 1% hypoxia for 48 hours (n = 3). Error bars represent ±SEM. *P < 0.05 using a Kruskal-Wallis statistic (B) and a Student’s t test (D).

Cultured Human Pulmonary ECs Express Hb α

To further confirm that the Hb α present in human and mouse pulmonary arteries was due to endogenous expression of Hb α by the ECs rather than either uptake of Hb from blood or contamination of our specimens, we performed cell culture experiments using primary human pulmonary ECs cocultured with primary human pulmonary VSMCs, as previously described (47). By Western blot with antibodies against Hb α, we confirmed that, as in systemic arterioles, pulmonary ECs enrich Hb α within the MEJ (Figure 3C). They do not express Hb β (data not shown), consistent with our previous work. Given our findings in humans and mice with PH, and previous data suggesting that cellular hypoxia up-regulates Hb expression in other pulmonary cells (28), we investigated whether hypoxia triggers increased expression of Hb α in pulmonary ECs. We performed vascular cell coculture experiments and exposed the cells in coculture to either normal oxygen levels or hypoxia. We found that ECs cocultured with pulmonary VSMCs and exposed to 48 hours of hypoxia significantly increased Hb α expression within the MEJ (Figures 3C and 3D).

Heterocellular Communication Is Required for Hypoxia-Induced Increased EC Hb α Expression

To determine whether heterocellular communication is necessary for hypoxia-induced increased EC Hb α expression, we performed coculture experiments where we cultured the VSMCs on the bottom of the well rather than on the Transwell insert, whereas the ECs remained on the upper surface of the Transwell insert. In this way, it was impossible for the ECs to form MEJs, but otherwise the culture conditions were identical. In this instance, there was low-level expression of Hb α within ECs, but hypoxia had no significant effect on Hb α expression (see Figure E1A in the online supplement). To exclude the possibility that culturing the ECs at 21% oxygen could be inducing Hb α expression by exerting a relative hyperoxic stress relative to in vivo physiologic conditions (41), we also compared Hb α expression in ECs cultured in hypoxia, normoxia, and physioxia. Again, there was no difference in Hb α expression. Because hypoxia itself can exert a variety of physiological effects, we sought to determine whether chemical induction of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1 α would affect Hb α expression. We cultured ECs in COCl2 at concentrations of either 100 or 500 μM for 24–48 hours, and saw no significant effect on Hb α expression. These results suggest that HIF-1 likely does not induce Hb α expression in PH.

Disruption of Pulmonary Endothelial Hb α–eNOS Interaction Increases PKG-Dependent Signaling in Cocultured Pulmonary VSMCs

We have previously shown that, in order for endothelial Hb α to function as a scavenger of endogenous NO, it must associate with eNOS (32). Inhibition of that association by an Hb α peptide mimetic, Hb α X peptide, was shown to increase NO bioavailability during vasoconstriction in systemic arteries, and lower blood pressure in mice (32). The effect of Hb α X peptide was dependent on expression of and interaction between both eNOS and endothelial Hb α, and was null in vessels lacking significant Hb α expression, such as the aorta. To test whether endothelial Hb α has a significant effect on endogenous NO signaling in pulmonary cells, we performed coculture and myography experiments of the endothelial-dependent vasodilators, bradykinin and ACh, respectively.

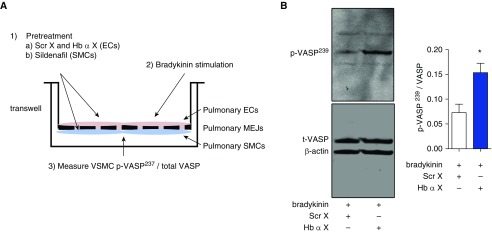

To determine the effects of Hb α X peptide on endogenously produced NO in our system, we performed pulmonary vascular cell coculture with human pulmonary ECs in the upper chamber of a Transwell system and human pulmonary VSMCs on the opposite side of the porous membrane (Figure 4A). We then treated the EC side of the Transwell with bradykinin or a vehicle control and isolated the VSMC layer, and measured the phosphorylation of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) at its serine 239 residue by Western blot (Figure 4A). Phosphorylated VASP (p-VASP239) is a sensitive and specific marker of PKG-dependent signaling, endothelial function, and NO signaling (48). p-VASP239 in the VSMC layer increased significantly in response to EC stimulation with bradykinin (Figure E2). We found that pretreating ECs with Hb α X peptide increased p-VASP239/VASP after stimulation with bradykinin when compared with the scrambled peptide (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Hb α X peptide increases NO signaling in a PA vascular cell coculture. (A) Schematic diagram illustrating the experimental design where pulmonary ECs and VSMCs were cocultured on Transwells. After 3 days, ECs were pretreated with scrambled control peptide (Scr X) or Hb α X peptide (5 μM, 30 min), and VSMCs were pretreated for 15 minutes with sildenafil (10 μM, 15 min). After pretreatment with peptides and sildenafil, ECs were stimulated with bradykinin (10 μM, 30 min). VSMCs were then fractionated and measured for cyclic guanosine monophosphate–protein kinase G–specific target protein, vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) serine 239 residue (p-VASP237), and total VASP. (B) Western blot for p-VASP237, total VASP, and β-actin in the SMC fraction of the coculture system. *P < 0.05 using a Student’s t test (B). Error bars represent ±SEM.

Disruption of Pulmonary Endothelial Hb α–eNOS Interaction Reverses PA Endothelial Dysfunction in Mice

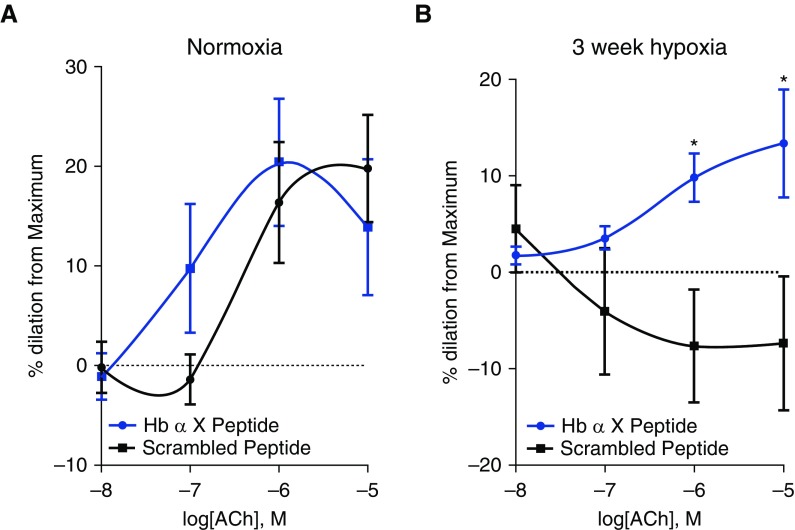

Humans and rodents with chronic hypoxia and humans with PH all demonstrate PA endothelial dysfunction manifested as diminished vasorelaxation responses to ACh (2, 24, 49, 50). To determine whether disruption of pulmonary endothelial Hb α/eNOS association could improve endothelial function in this setting, we performed wire myography on pulmonary arteries harvested from mice exposed to either normal oxygen conditions (21% O2) or 3 weeks of hypoxia (10% O2), with preincubation of the vessel with either Hb α X peptide or the scrambled peptide. Normoxic mice demonstrated an intact vasodilator response to ACh (Figure 5A). There were no significant differences between vessels treated with Hb α X peptide and the scrambled peptide. In hypoxic mice, however, we observed vasoconstriction to ACh, consistent with endothelial dysfunction (Figure 5B). Incubation with Hb α X peptide restored the vasodilator response to ACh (Figure 5B). These data suggest that disruption of the Hb α/eNOS complex can partially restore endogenous PA endothelial function.

Figure 5.

Hb α X peptide reverses PA endothelial dysfunction in hypoxic PH. Cumulative dose–response vascular reactivity curve to acetylcholine (ACh) in the presence of scrambled or Hb α X peptide (5 μM, 30 min preincubation) in second-order PAs from mice exposed to 21% oxygen (A) or 10% oxygen (B) for 3 weeks using wire myography. *P < 0.05 using a two-way ANOVA for the dose–response curve; n = 8–10 arteries from more than five mice for each experiment. Error bars represent ±SEM.

Discussion

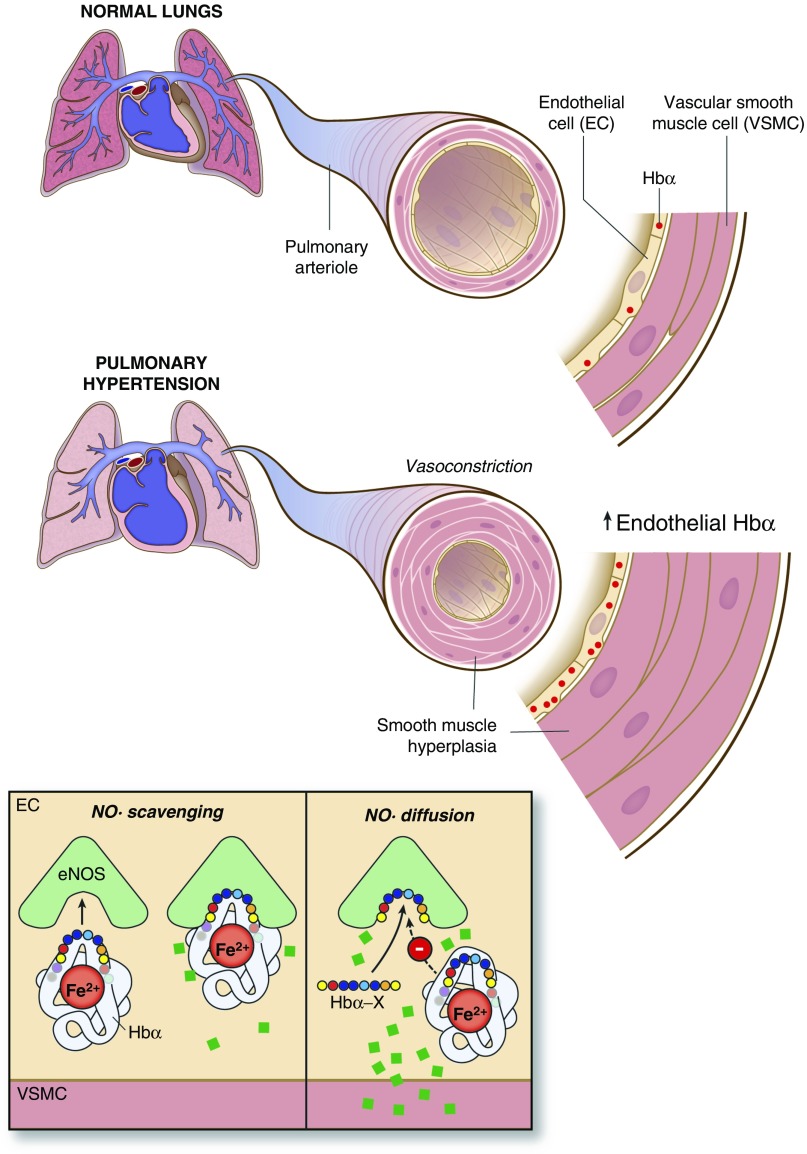

In this study, we present data supporting the hypothesis that Hb α plays a role in the endothelial dysfunction and NO depletion observed in PH. We show that pulmonary vascular Hb α is significantly increased in both human and hypoxic mouse PH. We also show at a cellular and molecular level, through our coculture bradykinin stimulation experiments, that disruption of Hb α/eNOS association with Hb α X peptide increases eNOS- and PKG-dependent signaling, as demonstrated by increased phosphorylation of VSMC p-VASP239. Finally, we present ex vivo evidence of restoration of ACh-dependent (and therefore endothelial-dependent) vasodilatation in the pulmonary arteries of mice with experimental PH caused by chronic hypoxia, suggesting that Hb α can act as an NO sink in PH. Our proposed model is outlined in the accompanying schematic (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Schematic of Hb α expression in pulmonary endothelium and its potential effect on NO signaling. Normal lungs express low levels of Hb α, allowing for abundant NO bioavailability, contributing to low basal pulmonary vascular resistance. However, in the setting of PH, Hb α is up-regulated at the protein level, which leads to increased NO scavenging, promoting PA endothelial dysfunction and vasoconstriction. Hb α X peptide inhibits coupling between Hb α and eNOS, increasing NO diffusion across the MEJ.

We show, through several different techniques, that Hb α is expressed and even up-regulated in the pulmonary vascular wall in chronic hypoxic mouse PH and human PH. The immunofluorescence imaging showed that Hb α staining within the pulmonary vasculature was greatest within ECs. Although Hb expression was noted throughout the ECs, there appeared to be areas of significant colocalization with eNOS. The increase in Hb α expression in PH samples was grossly visible in the tissue lysates, and was observable through Western blot as well as spectrophotometry. The increased expression was also consistent in the mouse models, strengthening the support for the conclusion that the increased Hb α expression is related to PH.

The vascular cell coculture confirmed the expression of Hb in the MEJ in a model that is completely devoid of erythrocyte contamination. The enrichment of Hb α expression in the MEJ fraction is consistent with prior publications in other vascular beds (27, 32). The increased Hb α in response to hypoxia in that model is also consistent with previous data in other pulmonary cell types (28, 29, 51), and internally consistent with the data from our hypoxic mouse experiments. Given the absence of any effect of hypoxia or COCl2 in EC monocultures, the changes in expression do not appear to be due to signaling through HIF. Rather, the absence of Hb α induction in the no-touch coculture system suggests that the hypoxic changes in EC Hb α expression appear to depend on a stimulus arising in the VSMCs and transmitted to the ECs through signaling in the MEJ. Candidate signals include changes in reactive oxygen species, intracellular calcium signaling, and electrochemical signals that are transmitted through MEJ gap junctions. Further studies of the heterocellular signaling between PA ECs and VSMCs are warranted (34).

By combining vascular cell coculture with measurement of bradykinin-induced p-VASP239 in the VSMCs, we are also able to demonstrate that disruption of Hb α–eNOS interaction through the Hb α mimetic peptide, Hb α X, increases PKG-dependent signaling in the VSMCs (48, 52). Although ACh stimulation is more specific for EC function and eNOS stimulation, these responses are lost in cell culture, likely related to changes in muscarinic receptor expression that occur in vitro (53, 54). Bradykinin responses are a useful surrogate for eNOS stimulation in vitro, and their validity as a model of NO signaling is enhanced by our use of p-VASP239 as a readout, which is known to be cGMP and PKG dependent (48, 49, 52, 55).

Finally, we show that PAs from mice exposed to chronic hypoxic PH demonstrate vasoconstrictor responses to ACh after preconstriction with prostaglandin F2α, consistent with severe endothelial dysfunction. We also show that treatment with Hb α X peptide restores a vasodilator response to ACh in these vessels. Hb α X peptide prevents the association of Hb α and eNOS (32). Previous experiments have confirmed that the activity of Hb α X peptide is dependent on the Hb α–eNOS axis, and are abrogated in the presence of pharmacologic or genetic loss of eNOS expression, as well as in the absence of significant Hb α expression (32). Hb α X peptide does not act through direct allosteric effects on eNOS activity, but rather through increasing the bioavailability of endogenous NO created by eNOS (32). Although the vasodilator response of the pulmonary arteries did not return to the same level as those seen in our normoxic mice, the fact that the Hb α X peptide was able to partially restore vasodilation supports the conclusion that Hb α plays a key role in inhibiting the expected vasodilator responses to ACh in this setting. The fact that Hb α X peptide did not have a significant effect on endothelial function in the PAs from normoxic mice is likely explained by the lower level of Hb α expression seen in the absence of PH in those animals, consistent with our immunofluorescence data.

There are important limitations to consider in our study. In our experiments using human tissues, there could be some degree of contamination from erythrocyte sources of Hb. By incubating the tissues in a red blood cell lysis buffer and carefully washing the tissues before preparing the tissue lysates for spectrophotometry and Western blot experiments, we sought to minimize such contamination. The effectiveness of our preparation technique in eliminating erythrocyte contamination is suggested by the absence of significant Hb α bands in the control subjects. Those experiments are also consistent with the immunofluorescence data, where there was no visible contamination with erythrocytes in the artery lumens. The immunofluorescence images do demonstrate some expression of Hb α within the adventitia of the vessels, perhaps related to increased vasa vasorum in the hypertensive vessels. However, the fact that we demonstrate an increase in the relative abundance of Hb α over Hb β suggests that the difference between PH and non-PH vessels arises from a nonerythrocyte source of Hb α, such as the vascular wall.

Another important limitation to our study is that our coculture and myography experiments using Hb α X peptide were necessarily performed in the presence of oxygen. Because the NO scavenging effect of Hb α is dependent on the presence of oxygen, and Hb α X peptide exerts its effect through inhibition of the Hb α/eNOS association required for that scavenging, it is unlikely to have a significant effect in the setting of significant hypoxia, where Hb α is likely to be in the deoxygenated state. Importantly, patients with PH do not typically experience significant systemic hypoxia. So, the consequences of Hb α expression on NO signaling in their pulmonary circulation are better represented by our blood vessel myography experiment, where oxygen tension was normal. Similarly, due to the fact that it is NO bioavailability and diffusion, rather than NO production, that is affected in our system, results of direct measurement of NO are both more technically challenging and difficult to interpret. Most available NO assays combine measurements of both NO2 and NO3−. As NO is converted to NO3− in its reaction with Hb α, this combined value is not indicative of the amount of NO that has successfully diffused to VSMCs and activated its receptor, sGC. For the purpose of measuring the downstream signal from NO, p-VASP239 served as a useful surrogate, and the fact that we stimulated the EC fraction and measured the p-VASP239 in the VSMC fraction does suggest that the differences in p-VASP239 were due to differences in NO diffusion from ECs.

Finally, we are unable to exclude other functions of Hb α in the pulmonary endothelium besides NO scavenging, in particular during hypoxia and under different redox conditions. For example, local tissue hypoxia increases oxidative stress, which may oxidize Hb and further permit increased diffusion of NO and vasodilation (25, 30). In fact, an important role for ferrous Hb may be to help sequester NO in defined cellular micro domains, preventing nitrosative stress that would otherwise occur if NO were permitted to diffuse more freely into other cellular compartments (25). Also perhaps relevant, it is now appreciated that deoxyhemoglobin within erythrocytes acts as a potent nitrite reductase, especially in acidic environments, such as those observed in areas of poorly ventilated lung or in chronic respiratory failure (56, 57). It is certainly possible that endothelial Hb α may play a similar role. In fact, its expression within the MEJ would situate it well to perform such a function. This potential role as an alternate source of NO may actually be an adaptive process to balance hypoxic vasoconstriction in a manner independent of eNOS (58). This would not necessarily exclude its role as an NO scavenger in other environments. Further experiments under acutely hypoxic conditions, including with and without the presence of nitrite, are warranted to further investigate this possibility.

Although important questions remain about the specific signals that regulate Hb α expression and possible alternative consequences of its expression by pulmonary ECs in chronic hypoxia and PH, our study demonstrates, for the first time, that Hb α is up-regulated in pulmonary ECs in humans and mice with PH, and that inhibiting its association with eNOS increases NO signaling, as evidenced by p-VASP239 and endothelial-dependent vasodilation. These observations suggest a possible role for targeting endothelial Hb α to improve endogenous NO signaling in PH. The additional finding that the expression of Hb α is regulated in part by a heterocellular signal from VSMCs also adds to the growing body of literature highlighting the importance of heterocellular cross-talk in the vascular wall.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R00 HL11290402, R01 HL128304, and R01 133864, AHA Grant-in-Aid (A.C.S.), R01HL113178, R01HL130261 (E.G.), R01 HL 131,789 (A.L.M.), P01 HL 103,455 (A.L.M. and E.G.), Department of Defense Research Grant W81XWH-07-10415 (M.R.), the Breathe Pennsylvania Warfield Garson Lung Disease Research Developmental Grant (R.A.A.), and by the Institute for Transfusion Medicine and the Hemophilia Center of Western Pennsylvania (A.L.M., E.G., and A.C.S.).

Author Contributions: R.A.A., E.G., and A.C.S. contributed to the conception and design of this study; R.A.A., M.P.M., S.A.H., J.C.G., J.H., J.S., D.G., and A.C.S. acquired the data; R.A.A., M.P.M., S.A.H., J.C.G., E.B., T.B., J.H., J.S., D.G., A.L.M., M.R., and A.C.S. were involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data; R.A.A. and A.C.S. drafted the manuscript, and all authors revised it critically for important intellectual content; all authors gave final approval of the version to be submitted.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0418OC on August 11, 2017

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Lai Y-CC, Potoka KC, Champion HC, Mora AL, Gladwin MT. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: the clinical syndrome. Circ Res. 2014;115:115–130. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.301146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Budhiraja R, Tuder RM, Hassoun PM. Endothelial dysfunction in pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2004;109:159–165. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000102381.57477.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLaughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, Barst RJ, Farber HW, Lindner JR, Mathier MA, McGoon MD, Park MH, Rosenson RS, et al. American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents; American Heart Association; American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society, Inc; Pulmonary Hypertension Association. ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents and the American Heart Association developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society, Inc.; and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1573–1619. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farber HW, Loscalzo J. Pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1655–1665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giaid A, Saleh D. Reduced expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the lungs of patients with pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:214–221. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507273330403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xue C, Johns RA. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the lungs of patients with pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1642–1644. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schermuly RT, Stasch JP, Pullamsetti SS, Middendorff R, Müller D, Schlüter KD, Dingendorf A, Hackemack S, Kolosionek E, Kaulen C, et al. Expression and function of soluble guanylate cyclase in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:881–891. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00114407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Frutos S, Nitta CH, Caldwell E, Friedman J, González Bosc LV. Regulation of soluble guanylyl cyclase-alpha1 expression in chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension: role of NFATc3 and HuR. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L475–L486. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00060.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xia XD, Xu ZJ, Hu XG, Wu CY, Dai YR, Yang L. Impaired iNOS-sGC-cGMP signalling contributes to chronic hypoxic and hypercapnic pulmonary hypertension in rat. Cell Biochem Funct. 2012;30:279–285. doi: 10.1002/cbf.2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fallah F. Recent strategies in treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension, a review. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;7:307–322. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v7n4p307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sahni S, Ojrzanowski M, Majewski S, Talwar A. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: a current review of pharmacological management. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2016;84:47–61. doi: 10.5603/PiAP.a2015.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humbert M, Ghofrani HA. The molecular targets of approved treatments for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Thorax. 2016;71:73–83. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ignarro LJ, Buga GM, Wood KS, Byrns RE, Chaudhuri G. Endothelium-derived relaxing factor produced and released from artery and vein is nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:9265–9269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnold WP, Mittal CK, Katsuki S, Murad F. Nitric oxide activates guanylate cyclase and increases guanosine 3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate levels in various tissue preparations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:3203–3207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Looft-Wilson RC, Billaud M, Johnstone SR, Straub AC, Isakson BE. Interaction between nitric oxide signaling and gap junctions: effects on vascular function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1818:1895–1902. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu S, Hu H, Dong H. Systematic review of the economic burden of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34:533–550. doi: 10.1007/s40273-015-0361-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peinado VI, Barbera JA, Ramirez J, Gomez FP, Roca J, Jover L, Gimferrer JM, Rodriguez-Roisin R. Endothelial dysfunction in pulmonary arteries of patients with mild COPD. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:L908–L913. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.6.L908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dinh-Xuan AT, Higenbottam TW, Clelland CA, Pepke-Zaba J, Cremona G, Butt AY, Large SR, Wells FC, Wallwork J. Impairment of endothelium-dependent pulmonary-artery relaxation in chronic obstructive lung disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1539–1547. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199105303242203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dinh Xuan AT, Higenbottam TW, Clelland C, Pepke-Zaba J, Cremona G, Wallwork J. Impairment of pulmonary endothelium–dependent relaxation in patients with Eisenmenger’s syndrome. Br J Pharmacol. 1990;99:9–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb14643.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Apitz C, Zimmermann R, Kreuder J, Jux C, Latus H, Pons-Kühnemann J, Kock I, Bride P, Kreymborg KG, Michel-Behnke I, et al. Assessment of pulmonary endothelial function during invasive testing in children and adolescents with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xue C, Johns RA. Upregulation of nitric oxide synthase correlates temporally with onset of pulmonary vascular remodeling in the hypoxic rat. Hypertension. 1996;28:743–753. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.28.5.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hampl V, Cornfield DN, Cowan NJ, Archer SL. Hypoxia potentiates nitric oxide synthesis and transiently increases cytosolic calcium levels in pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:515–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mason NA, Springall DR, Burke M, Pollock J, Mikhail G, Yacoub MH, Polak JM. High expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in plexiform lesions of pulmonary hypertension. J Pathol. 1998;185:313–318. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199807)185:3<313::AID-PATH93>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaul PW, Wells LB, Horning KM. Acute and prolonged hypoxia attenuate endothelial nitric oxide production in rat pulmonary arteries by different mechanisms. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1993;22:819–827. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199312000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crosswhite P, Sun Z. Nitric oxide, oxidative stress and inflammation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Hypertens. 2010;28:201–212. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328332bcdb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brittain EL, Janz DR, Austin ED, Bastarache JA, Wheeler LA, Ware LB, Hemnes AR. Elevation of plasma cell-free hemoglobin in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest. 2014;146:1478–1485. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saha D, Patgaonkar M, Shroff A, Ayyar K, Bashir T, Reddy KV. Hemoglobin expression in nonerythroid cells: novel or ubiquitous? Int J Inflam. 2014;2014:803237. doi: 10.1155/2014/803237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grek CL, Newton DA, Spyropoulos DD, Baatz JE. Hypoxia up-regulates expression of hemoglobin in alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44:439–447. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0307OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newton DA, Rao KM, Dluhy RA, Baatz JE. Hemoglobin is expressed by alveolar epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5668–5676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509314200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Straub AC, Lohman AW, Billaud M, Johnstone SR, Dwyer ST, Lee MY, Bortz PS, Best AK, Columbus L, Gaston B, et al. Endothelial cell expression of haemoglobin α regulates nitric oxide signalling. Nature. 2012;491:473–477. doi: 10.1038/nature11626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Helms C, Kim-Shapiro DB. Hemoglobin-mediated nitric oxide signaling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;61:464–472. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Straub AC, Butcher JT, Billaud M, Mutchler SM, Artamonov MV, Nguyen AT, Johnson T, Best AK, Miller MP, Palmer LA, et al. Hemoglobin α/eNOS coupling at myoendothelial junctions is required for nitric oxide scavenging during vasoconstriction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:2594–2600. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Butcher JT, Johnson T, Beers J, Columbus L, Isakson BE. Hemoglobin α in the blood vessel wall. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;73:136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao Y, Chen T, Raj JU. Endothelial and smooth muscle cell interactions in the pathobiology of pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;54:451–460. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0323TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheadle C, Berger AE, Mathai SC, Grigoryev DN, Watkins TN, Sugawara Y, Barkataki S, Fan J, Boorgula M, Hummers L, et al. Erythroid-specific transcriptional changes in PBMCs from pulmonary hypertension patients. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bogoslovsky T, Wang D, Maric D, Scattergood-Keepper L, Spatz M, Auh S, Hallenbeck J. Cryopreservation and enumeration of human endothelial progenitor and endothelial cells for clinical trials. J Blood Disord Transfus. 2013;4:158. doi: 10.4172/2155-9864.1000158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma Z, Mao L, Rajagopal S.Hemodynamic characterization of rodent models of pulmonary arterial hypertension J Vis Exp 2016110DOI: 10.3791/53335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ke SK, Chen L, Duan HB, Tu YR. Opposing actions of TRPV4 channel activation in the lung vasculature. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2015;219:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goncharova EA, Ammit AJ, Irani C, Carroll RG, Eszterhas AJ, Panettieri RA, Krymskaya VP. PI3K is required for proliferation and migration of human pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L354–L363. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00010.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Isakson BE, Duling BR. Heterocellular contact at the myoendothelial junction influences gap junction organization. Circ Res. 2005;97:44–51. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000173461.36221.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carreau A, El Hafny-Rahbi B, Matejuk A, Grillon C, Kieda C. Why is the partial oxygen pressure of human tissues a crucial parameter? Small molecules and hypoxia. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:1239–1253. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01258.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rahaman MM, Reinders FG, Koes D, Nguyen AT, Mutchler SM, Sparacino-Watkins C, Alvarez RA, Miller MP, Cheng D, Chen BB, et al. Structure guided chemical modifications of propylthiouracil reveal novel small molecule inhibitors of cytochrome b5 reductase 3 that increase nitric oxide bioavailability. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:16861–16872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.629964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rahaman MM, Nguyen AT, Miller MP, Hahn SA, Sparacino-Watkins C, Jobbagy S, Carew NT, Cantu-Medellin N, Wood KC, Baty CJ, et al. Cytochrome b5 reductase 3 modulates soluble guanylate cyclase redox state and cGMP signaling. Circ Res. 2017;121:137–148. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dunn KW, Kamocka MM, McDonald JH. A practical guide to evaluating colocalization in biological microscopy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;300:C723–C742. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00462.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lagoa CE, Vodovotz Y, Stolz DB, Lhuillier F, McCloskey C, Gallo D, Yang R, Ustinova E, Fink MP, Billiar TR, et al. The role of hepatic type 1 plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1) during murine hemorrhagic shock. Hepatology. 2005;42:390–399. doi: 10.1002/hep.20797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sugita Y. Differences in spectra of α and β chains of hemoglobin between isolated state and in tetramer. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:1251–1256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heberlein KR, Straub AC, Best AK, Greyson MA, Looft-Wilson RC, Sharma PR, Meher A, Leitinger N, Isakson BE. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 regulates myoendothelial junction formation. Circ Res. 2010;106:1092–1102. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.215723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oelze M, Mollnau H, Hoffmann N, Warnholtz A, Bodenschatz M, Smolenski A, Walter U, Skatchkov M, Meinertz T, Münzel T. Vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein serine 239 phosphorylation as a sensitive monitor of defective nitric oxide/cGMP signaling and endothelial dysfunction. Circ Res. 2000;87:999–1005. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.11.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Castro AF, Amorena C, Müller A, Ottaviano G, Tellez-Iñon MT, Taquini AC. Extracellular ATP and bradykinin increase cGMP in vascular endothelial cells via activation of PKC. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C113–C119. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.1.C113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vitali SH, Hansmann G, Rose C, Fernandez-Gonzalez A, Scheid A, Mitsialis SA, Kourembanas S. The Sugen 5416/hypoxia mouse model of pulmonary hypertension revisited: long-term follow-up. Pulm Circ. 2014;4:619–629. doi: 10.1086/678508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ishikawa N, Ohlmeier S, Salmenkivi K, Myllärniemi M, Rahman I, Mazur W, Kinnula VL. Hemoglobin α and β are ubiquitous in the human lung, decline in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis but not in COPD. Respir Res. 2010;11:123. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sheng H, Ishii K, Förstermann U, Murad F. Mechanism of bradykinin-induced cyclic GMP accumulation in bovine tracheal smooth muscle. Lung. 1995;173:373–383. doi: 10.1007/BF00172144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Durr E, Yu J, Krasinska KM, Carver LA, Yates JR, Testa JE, Oh P, Schnitzer JE. Direct proteomic mapping of the lung microvascular endothelial cell surface in vivo and in cell culture. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:985–992. doi: 10.1038/nbt993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tracey WR, Peach MJ. Differential muscarinic receptor mRNA expression by freshly isolated and cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells. Circ Res. 1992;70:234–240. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McMahon TJ, Hood JS, Bellan JA, Kadowitz PJ. N omega-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester selectively inhibits pulmonary vasodilator responses to acetylcholine and bradykinin. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1991;71:2026–2031. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.5.2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim-Shapiro DB, Schechter AN, Gladwin MT. Unraveling the reactions of nitric oxide, nitrite, and hemoglobin in physiology and therapeutics. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:697–705. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000204350.44226.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gladwin MT, Kim-Shapiro DB. The functional nitrite reductase activity of the heme-globins. Blood. 2008;112:2636–2647. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-115261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hardison RC. Evolution of hemoglobin and its genes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a011627. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]