Abstract

Background

The WHO and the World Bank ask countries to report the national volume of surgery. This report describes these data for Sweden, a high‐income country.

Methods

In an 8‐year population‐based observational cohort study, all inpatient and outpatient care in the public and private sectors was detected in the Swedish National Patient Register and screened for the occurrence of surgery. The entire Swedish population was eligible for inclusion. All patients attending healthcare for any disease were included. Incidence rates of surgery and likelihood of surgery were calculated, with trends over time, and correlation with sex, age and disease category.

Results

Almost one in three hospitalizations involved a surgical procedure (30·6 per cent). The incidence rate of surgery exceeded 17 480 operations per 100 000 person‐years, and at least 58·5 per cent of all surgery was performed in an outpatient setting (range 58·5 to 71·6 per cent). Incidence rates of surgery increased every year by 5·2 (95 per cent c.i. 4·2 to 6·1) per cent (P < 0·001), predominantly owing to more outpatient surgery. Women had a 9·8 (95 per cent c.i. 5·6 to 14·0) per cent higher adjusted incidence rate of surgery than men (P < 0·001), mainly explained by more surgery during their fertile years. Incidence rates peaked in the elderly for both women and men, and varied between disease categories.

Conclusion

Population requirements for surgery are greater than previously reported, and more than half of all surgery is performed in outpatient settings. Distributions of age, sex and disease influence estimates of population surgical demand, and should be accounted for in future global and national projections of surgical public health needs.

Short abstract

Higher than previously reported

Introduction

Reliable information on the delivery of surgical services is a new priority in advancing global health1. In 2015, all member states of the WHO unanimously passed Resolution 68/15 calling for the collection of meaningful and reliable measures on access to surgical care2. Initiatives to standardize the reporting of such information include the core indicators of the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery and the Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD) consensus on surgical data collection3, 4. As a measure of the rising importance of surgical metrics, the fundamental surgical indicator – number of surgical procedures – was recently integrated into both the Global Reference List of 100 Core Health Indicators promoted by the WHO, and in the World Development Indicators by the World Bank5, 6.

A great challenge exists in quantifying surgical output and need for surgery at the population level. In most parts of the world, surgical procedure volume is unreported, or unknown, and it has proven methodologically difficult to benchmark population requirements for surgical care7. Recently, national facility‐based data registries in the USA and New Zealand advanced understanding of rates of surgical procedures for discrete disease categories8, 9. However, these studies excluded large volumes of operations performed in the outpatient setting and the private sector, and hence the public health requirement for surgical procedures at the population level is not yet fully known.

The purpose of this study was to quantify the complete volume of surgical procedures for a population, and to describe the relationship between age and sex and the panorama of diseases requiring surgical intervention across multiple healthcare settings. The intention was to minimize sampling errors in a national cohort by including all significant components of a comprehensive healthcare system with low barriers to care, such as public and private sectors, and all inpatient and outpatient care. The Swedish National Patient Register was used to analyse healthcare utilization, and to estimate the total need for surgical procedures and its distribution within a population.

Methods

This was a register‐based cohort study of the entire Swedish population. Data for all inpatient and outpatient care in Sweden between 2006 and 2013 were retrieved from the Swedish National Patient Register, which contains prospectively collected demographic, administrative and medical information, including primary and secondary diagnoses, and procedure codes for every registered inpatient admission or outpatient visit in both public and private parts of the healthcare sector10, 11, 12. Aggregated population data by age and sex were collected from Statistics Sweden13. The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare provided ethical approval for the study. No sensitive information was accessed. Only aggregated data were collected and indirect disclosure was not possible.

Study setting

Sweden is a high‐income country with a mean population of 9 374 052 during 2006–201314, 15. In 2013, the net health expenditure per capita was US $5003 (€4402, exchange rate 3 July 2017), of which 83·4 per cent was publicly funded at a cost of 9·3 per cent of the gross domestic product16. Governmental health insurance covers 100 per cent of the population, and most indicators of health outcomes and quality of care are equal or above the OECD average17, 18. At any given time, there are 44 hospitals providing comprehensive emergency surgical care, with an estimated 99·6 per cent of the population having access to such hospitals within 2 h travelling time19. The number of hospital beds has decreased during the past decade to 2·59 per 1000 population in 2013, which is just over half of the OECD average of 4·84 per 100020. As citizens enjoy equitable and high access to care, and because there are well developed registers and administrative infrastructure, Sweden is suitable for studies of population needs and health service delivery16, 21.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All patients who received any kind of inpatient or outpatient care in Sweden between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2013 were identified. Outpatient care included day surgery and outpatient clinic visits, except primary care, homecare and school care. Medical services not covered by the Swedish healthcare jurisdiction, such as private providers of aesthetically motivated procedures, do not report to the register and were not included. Strictly aesthetic procedures were reported to the register only if they were performed within the healthcare sector and coded according to the ICD‐10 system. Primary diagnoses were classified according to ICD‐10, with three‐digit resolution22. Surgical procedures were classified according to the Swedish version of the Nordic Medico‐Statistical Committee (NOMESCO) Classification of Surgical Procedures version 1.16, with three‐digit resolution (chapters A–Q)23. A heterogeneous group of additional procedures were not included in the overall analysis, but reported separately from the open data sets provided by the Swedish Board of Health and Welfare: superficial incisions, punctures, needle aspiration and needle biopsies (chapter T); transluminal endoscopy through natural or artificial body orifices (chapter U); ultrasonography and other investigative procedures connected with surgery (chapter X); and the procurement of organs or tissue for transplantation (chapter Y)24, 25.

Definitions

The terms ‘admission’ and ‘hospitalization’ were used synonymously for inpatient care, and the term ‘visit’ was used for outpatient care and day surgery. Medical doctors coded all the care events. The primary diagnosis was considered the cause of surgery. Admissions and visits were unique and individual patients may have presented multiple times during the study interval.

The incidence rate of surgery was the annual number of operations per 100 000 person‐years and the population denominator for each year was the mean for the official Swedish population at the beginning and end of the year14. The data source detailed the total number of surgical procedure codes per admission, which may have occurred during one or several unique surgical operations. The most conservative estimate was that all registered inpatient surgical procedures were performed during one single operation and the most liberal estimate was that every surgical procedure code represents a unique operation. For inpatient care, the most conservative value was used as a point estimate and the most liberal value as the range. For outpatient care, no more than one operation could be performed per visit. The likelihood of surgery was defined as the number of admissions or visits associated with surgery divided by the total number of admissions or visits, expressed as a percentage.

Outcomes and independent variables

The primary outcome was incidence rate of surgery during inpatient and outpatient care. Secondary outcomes were likelihood of surgery, primary diagnosis, and type of procedure during admissions and visits. Independent variables were year, age and sex.

Coverage and validity of registers

All public and private providers of inpatient care, and all outpatient somatic and psychiatric clinics in Sweden are by law required to report to the Swedish National Patient Register11. The coverage in the National Patient Register is close to 100 per cent for inpatient care, and 80 per cent for outpatient care10. The validity is high, with 99 per cent of inpatient diagnoses and 86·5 per cent of outpatient diagnoses being reported correctly10.

Statistical analysis

The incidence rate of surgery and likelihood of surgery were analysed for trends over time. Inpatient admissions and outpatient visits were analysed both separately and in combination. Sex‐specific incidence rates were calculated. Data were grouped into 5‐year age intervals, and were stratified by year and sex. Diagnoses were grouped according to the main disease categories in the WHO Global Health Estimates (GHE) and according to the ICD‐10 system22, 26 (Tables S1 and S2, supporting information).

Linear regression with log transformation of the dependent variable was used for univariable analysis of trends over time and results presented as percentages. Multivariable Poisson regression models were used to obtain estimated trends over time using a robust function, adjusted for age and sex variations in the population to compensate for demographic changes over time. The incidence rate ratios are presented as percentages with 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Microsoft Excel® for Mac 2011 version 14.4.8 (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA) was used for data processing, and SPSS® version 22 release 22.0.0.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) for statistical analyses.

Results

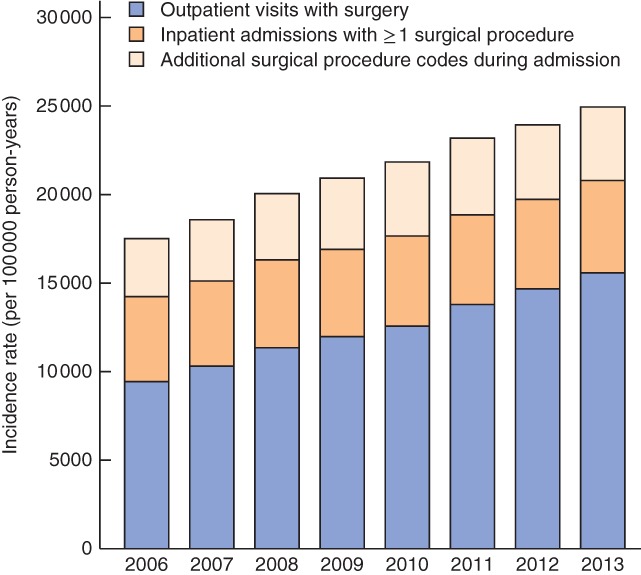

During the 8‐year study interval, 2006–2013, there were 12 million inpatient admissions and 76 million outpatient visits, and more than 13 million unique surgical procedures (conservative to most liberal estimated range 13 111 172–16 06 003) (Table 1). Surgery was performed in 30·6 per cent of all inpatient admissions and this was stable over time (B = 0·003, P < 0·001), but most surgical procedures were undertaken in an outpatient setting (range 58·5–71·6 per cent) (Table 1). The incidence rate of surgery over the entire study period was 17 480 (conservative to most liberal estimated range 17 480–21 420) per 100 000 person‐years. In 2013, the final year of study, the overall incidence rate of surgery was at least 20 748 (20 748–25 058) operations per 100 000 person‐years, corresponding to 5110 (5110–9420) inpatient operations and 15 638 outpatient operations per 100 000 person‐years (Fig. 1). In the same year, additionally 4598 (4598–4702) superficial incisions, punctures, needle aspiration and needle biopsies, and 4187 (4187–4321) transluminal endoscopies were carried out per 100 000 population.

Table 1.

Incidence rates of surgery during inpatient and outpatient care in Sweden, 2006–2013

| Age (years) | n * | Incidence rate (per 100 000 person‐years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inpatient care | Outpatient care | Total surgery‡ | ||||

| All admissions† | Surgery‡ | All visits§ | Surgery | |||

| 0–4 | 550 606 | 11 050 | 2020–4030 | 93 400 | 4230 | 6250–8260 |

| 5–9 | 510 683 | 3610 | 1350–2710 | 59 330 | 4100 | 5450–6810 |

| 10–14 | 512 505 | 4000 | 1500–2930 | 61 040 | 3990 | 5490–6920 |

| 15–19 | 606 991 | 6650 | 2010–3480 | 72 720 | 5810 | 7820–9290 |

| 20–24 | 613 358 | 9210 | 2680–4560 | 71 710 | 6900 | 9580–11 460 |

| 25–29 | 581 776 | 12 310 | 4020–6930 | 80 370 | 7900 | 11 920–14 830 |

| 30–34 | 589 876 | 13 590 | 4810–8450 | 86 580 | 8830 | 13 640–17 280 |

| 35–39 | 625 583 | 10 590 | 3830–6890 | 84 640 | 9670 | 13 500–16 560 |

| 40–44 | 655 637 | 8940 | 3080–5640 | 81 710 | 9680 | 12 760–15 320 |

| 45–49 | 632 247 | 10 040 | 3350–6190 | 88 010 | 10 680 | 14 030–16 870 |

| 50–54 | 586 228 | 12 250 | 4080–7600 | 99 210 | 12 600 | 16 680–20 200 |

| 55–59 | 583 810 | 15 010 | 5170–9610 | 111 760 | 14 840 | 20 010–24 450 |

| 60–64 | 606 237 | 19 190 | 6790–12 510 | 129 340 | 18 120 | 24 910–30 630 |

| 65–69 | 526 007 | 24 470 | 8590–15 690 | 150 510 | 22 860 | 31 450–38 550 |

| 70–74 | 388 598 | 32 590 | 10 790–19 300 | 175 760 | 27 980 | 38 770–47 280 |

| 75–79 | 308 947 | 44 060 | 13 030–22 830 | 195 810 | 32 240 | 45 270–55 070 |

| 80–84 | 247 218 | 56 710 | 14 330–24 380 | 191 590 | 32 500 | 46 830–56 880 |

| 85–89 | 163 935 | 69 000 | 14 840–24 820 | 165 000 | 28 440 | 43 280–53 260 |

| ≥ 90 | 83 810 | 73 120 | 13 670–22 940 | 116 190 | 18 990 | 32 660–41 930 |

| Overall | 9 374 052 | 16 200 | 4960–8900 | 101 880 | 12 520 | 17 480–21 420 |

Mean Swedish population per year during the 8‐year study interval.

Inpatient admission for any disease;

most conservative and most liberal estimates;

outpatient visit for any disease.

Figure 1.

Incidence rates of surgical procedures in Sweden, 2006–2013

Differences over time

Every year, the incidence rate of surgery increased by 5·4 per cent on average (P < 0·001); after adjusting for demographic changes in age and sex, the estimated annual increase in surgery was 5·2 (95 per cent c.i. 4·2 to 6·1 per cent; P < 0·001). The increase was most pronounced in outpatient care; after adjusting for demographic changes in age and sex, the annual increase was 1·3 (–0·001 to 2·7) per cent in inpatient surgery (P = 0·066), and 6·7 (5·9 to 7·5) per cent in outpatient surgery (P < 0·001). In contrast, the overall consumption of inpatient care in Swedish society did not change during the study interval (0·2 (–1·0 to 1·4) per cent; P = 0·763), whereas the overall consumption of outpatient care increased by 4·1 (3·4 to 4·9) per cent per year (P < 0·001). In effect, the annual increase in the proportion of surgery being performed in an outpatient setting was on average 1·5 percentage points (B = 0·015, P < 0·001), so that in 2013 up to 75·4 per cent of operations (range 75·4–66·9 per cent for conservative and liberal counts of inpatient procedures) were performed in outpatient care.

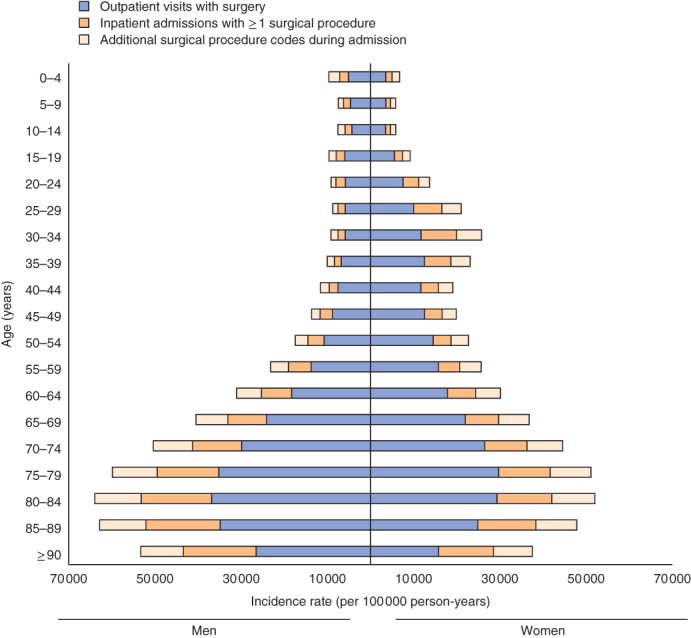

Sex

Men underwent significantly less surgery than women, and were less likely to be admitted for surgical care (Fig. 2). After adjusting for age and changes over time, the incidence rate of surgery was 9·8 (95 per cent c.i. 5·6 to 14·0) per cent higher among women (P < 0·001). The adjusted sex difference reached 16·4 (9·9 to 23·0) per cent for inpatient care (P < 0·001) and 7·2 (3·7 to 10·7) per cent for outpatient care (P < 0·001). In 2013, the incidence rate of inpatient surgery was 5710 (conservative to most liberal estimated range 5710–10 580) per 100 000 women, and 4510 (4510–8260) per 100 000 men. In outpatient care the same year, women had an incidence rate of 17 040 procedures per 100 000 person‐years, compared with 14 230 per 100 000 person‐years for men.

Figure 2.

Incidence rates of surgical procedures by age and sex in Sweden, 2006–2013

Age

There was considerable variation in incidence rates of surgery between different age groups, for both women and men (P < 0·001). In women, the incidence rate of surgery increased remarkably during childbearing age. Children had generally a lower incidence rate of surgery than adults of all ages (Fig. 2). The peak incidence rate was observed among 80–84‐year‐olds (conservative to most liberal estimated range 42 310–51 990 per 100 000 person‐years for women and 53 390–63 970 per 100 000 person‐years for men), and the lowest incidence rate for 5–9‐year‐olds (4660–5830 per 100 000 person‐years for girls and 6190–7720 per 100 000 person‐years for boys).

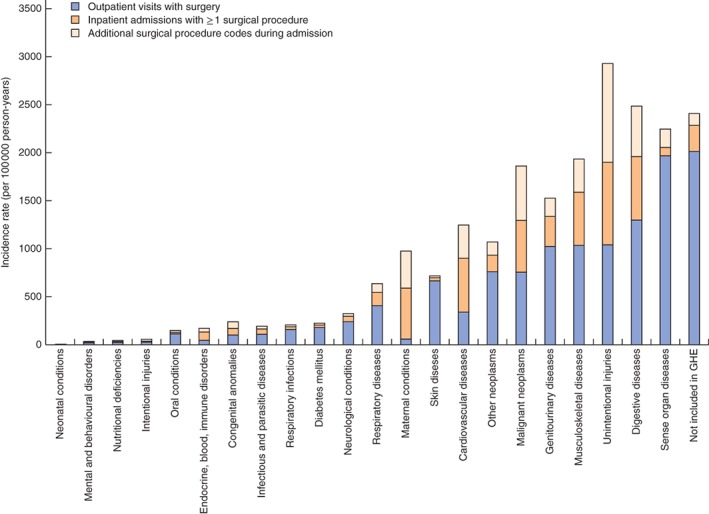

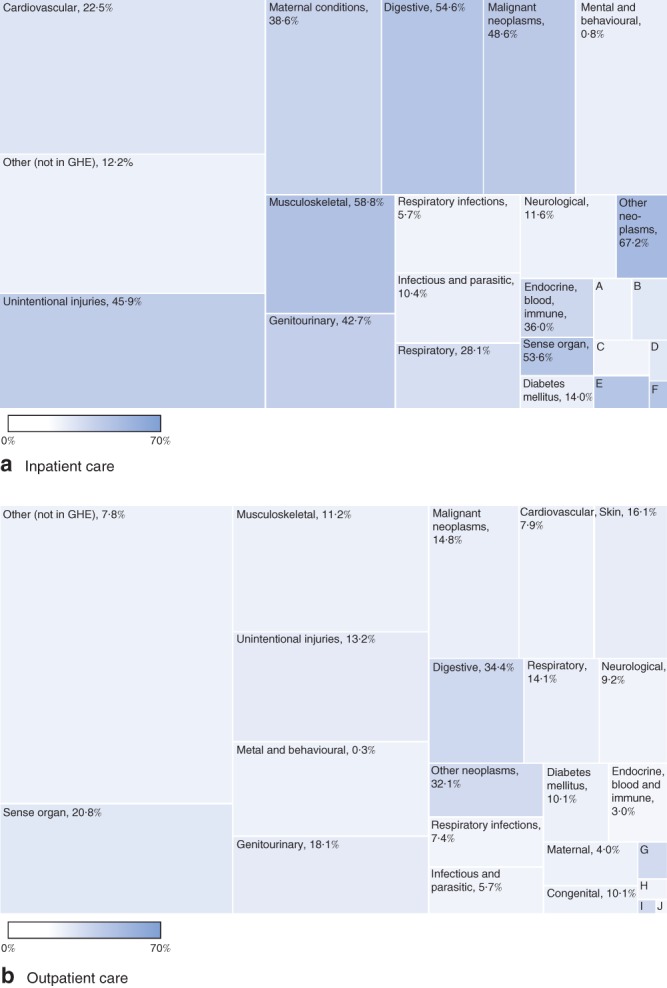

Disease category

Surgery was performed for all disease categories (Fig. 3). However, the likelihood of surgery during an inpatient admission or outpatient visit varied between disease categories, from below 1 per cent in both inpatient and outpatient care of mental disorders, up to 67·2 per cent in inpatient care for other neoplasms, and 34·4 per cent in outpatient care for digestive diseases (Fig. 4). Overall, the likelihood of surgery was low in outpatient care compared with inpatient care. Nonetheless, surgical volumes in outpatient settings were considerable, and outpatient surgery outnumbered the volumes in inpatient care for most disease categories (Table S1, supporting information). As a consequence, the overall incidence rate of surgery varied from fewer than ten procedures (conservative to most liberal estimated range 6·2–8·9) per 100 000 person‐years for neonatal conditions, to more than 2060 (2062–2255) per 100 000 person‐years for sense organ diseases, followed by digestive diseases (1966–2490 per 100 000 person‐years) and unintentional injuries (1905–2935 per 100 000 person‐years) (Fig. 3). The most commonly performed procedures (Table 2) were constant throughout the study interval. Detailed information on disease categories according to GHE and ICD‐10 is available in Tables S1 and S2 (supporting information).

Figure 3.

Incidence rates of surgical procedures in Sweden for WHO Global Health Estimates (GHE) disease categories, 2006–2013

Figure 4.

WHO Global Health Estimates (GHE) disease categories and their contribution to surgery performed in Sweden, 2006–2013: a inpatient admissions and b outpatient visits. Box areas represent counts, and the colour intensity in each box (also presented as a percentage) indicates the proportion of contacts in each disease category with at least one surgical procedure. A, intentional injuries, 10·6 per cent; B, skin, 29·8 per cent; C, neonatal, 4·1 per cent; D, nutritional deficiencies, 29·1 per cent; E, congenital, 64·1 per cent; F, oral, 59·2 per cent; G, oral, 29·5 per cent; H, intentional injuries, 13·3 per cent; I, nutritional deficiencies, 27·5 per cent; J, neonatal, 1·5 per cent. Further details can be found in Table S1 (supporting information)

Table 2.

Most common inpatient and outpatient surgical procedures for men and women in Sweden, 2006–2013

| Incidence rate (per 100 000 person‐years) | |

|---|---|

| Inpatient surgery | |

| Men | |

| Expansion and recanalization of coronary artery | 295 |

| Intraocular operations on vitreous body and retina | 194 |

| Fracture surgery of femur | 176 |

| Primary prosthetic replacement of hip joint | 162 |

| Partial excision of prostate | 137 |

| Appendicectomy | 123 |

| Fracture surgery of ankle and foot | 113 |

| Primary prosthetic replacement of knee joint | 107 |

| Women | |

| Caesarean section | 396 |

| Fracture surgery of femur | 345 |

| Primary prosthetic replacement of hip joint | 255 |

| Surgical induction or advancement of labour | 232 |

| Repair of obstetric lacerations | 231 |

| Total excision of uterus | 158 |

| Operations on gallbladder | 153 |

| Primary prosthetic replacement of knee joint | 153 |

| Outpatient surgery | |

| Men | |

| Extracapsular cataract operations with phacoemulsification | 607 |

| Excision and repair of lesion of skin of head and neck | 340 |

| Excision and repair of lesion of skin of trunk | 247 |

| Procedures for wounds of skin of upper limb | 240 |

| Repair of inguinal hernia | 237 |

| Procedures for wounds of skin of head and neck | 219 |

| Intraocular operations on vitreous body and retina | 213 |

| Operations on meniscus of knee | 198 |

| Women | |

| Extracapsular cataract operations with phacoemulsification | 931 |

| Intrauterine operations and biopsy of uterus and ligaments | 455 |

| Dilatation, curettage and biopsy of cervix uteri | 411 |

| Excision and repair of lesion of skin of head and neck | 365 |

| Intraocular operations on vitreous body and retina | 302 |

| Excision and repair of lesion of skin of trunk | 254 |

| Operations for impaired function of peripheral nerves | 206 |

| Operations on lens for secondary cataract | 171 |

Discussion

Surgical interventions play a prominent role in the provision of healthcare in Sweden. The overall incidence of surgical procedures was high, with an annual increase in recent years, both in absolute numbers and relative to the total amount of care. Surgical procedures occurred in nearly one in three hospitalizations, and yet surgery in outpatient settings outnumbered the volumes performed during inpatient care across all age groups and most disease categories. Surgical disease affects people of all ages, but more so the elderly and the female population. This study offers a comprehensive exploration of the role of surgical care in a healthcare system, and confirms that surgical care is a fundamental building block of universal health coverage.

These findings are consistent with other studies regarding the broad spectrum of surgical care and demonstrate the substantial role of outpatient encounters in meeting the needs of a population8, 9, 27. Overall, it could be confirmed that surgical procedures are involved in treating every major disease category of the extensive WHO GHE8. The proportion of Swedish hospitalizations that included a surgical procedure was similar to that in national studies of inpatient services in the USA (28·6 per cent) and New Zealand (24·9 per cent)8, 9. However, studies evaluating population needs for surgery in the USA and New Zealand were limited to data sets that excluded large volumes of procedures in outpatient care and the private sector. When this broader scope of surgical care is included, it is shown here that roughly two‐thirds (58·5–71·6 per cent) of the total surgical volume occurs in the outpatient setting, suggesting that a population's true need for surgical care is even greater than previously reported.

Use of surgical measures as core indicators of health performance at the country level has recently been promoted by both the WHO and the World Bank to guide implementation of national surgical plans worldwide and to evaluate their effectiveness2, 3, 5, 6. Data on surgical output in Sweden may contribute to benchmarking for such core indicators, and the present sex‐specific data on surgical incidence in different age strata will enable standardized projections of surgical needs and comparisons with populations elsewhere. As life expectancy continues to rise in low‐ and middle‐income countries, the anticipated increase in demand for surgical care may be more predictable, which is relevant in the context of recent targets to upscale surgical services in low‐ and middle‐income countries. In 2015, the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery3 showed that a minimum of 143 million additional surgical procedures are needed each year to cover the current global disease burden, and an initial target of 5000 surgical procedures per 100 000 population annually was recommended for Ministries of Health to improve access to surgical services3. This target was supported by correlations between national surgical outputs and key population health indicators (life expectancy), and benchmarks from disease‐specific rates of surgical procedures in New Zealand's nationalized healthcare system28. The present results provide a robust validation of these findings, and contextualize how a country could extend an even broader scope of surgical services to the public.

Based on these findings, it can be recommended that outpatient surgical care be considered an integrated part of surgical systems, and that future research should investigate variations between countries to improve benchmarking. Although hospital bed rates in Sweden have decreased during the study interval, healthcare utility has increased in outpatient settings. Whether it is possible that healthcare systems in low‐ and middle‐income countries may benefit from strengthening outpatient surgical care as a cost‐effective alternative to inpatient care remains to be addressed by future investigations. Measurement of both inpatient and outpatient surgery will both enable a more granular understanding of variations in surgical volume and ensure that measurements are not influenced by such organizational shifts in the provision of surgical care.

These findings must be interpreted with certain limitations in mind. The panorama of surgery in Sweden may differ from what is to be expected in other populations. Even if the present findings can be standardized to other populations based on age, sex and ICD‐10 distribution, the value of specific interventions and alternative treatment options is dynamic over time, and expectations in the community may differ globally. The method used in the present study does not provide a means of grading the need for any given surgical procedures to achieve or improve health. The data set did, however, not include exclusively aesthetically motivated surgery in the private sector, and the largely state‐financed healthcare system in Sweden provides relatively low economic incentives for overproduction of surgical care. As a sensitivity analysis, the data set was screened for strictly aesthetic procedures (using ICD‐10 code Z41 ‘procedures performed for reasons other than improving health’); these represented less than 0·1 per cent of all included procedures, confirming that these procedures are unlikely to skew the results.

This study also has limitations that are intrinsic to the Swedish National Patient Register. During the study interval, only 80 per cent of outpatient care providers reported to the National Patient Register, and as a consequence the data might slightly underestimate surgery performed in that sector. In addition, the number of unique trips to the operating theatre in a single hospitalization could not be specified, and therefore the most conservative measure is reported. Although the structure and legislation of healthcare policy did not change dramatically during the study interval, it is possible that the tendency and ability to report diagnostic codes or procedure codes could have changed. Finally, it is possible that surgical procedures are both overperformed and underperformed for discrete disease categories. As such, national surgical output should best be interpreted as a surrogate for surgical need (‘met need’), but not equal to surgical need as defined by epidemiological survey studies29. In fact, as a high‐income country with a long tradition of equal access to socialized healthcare, generalization of the present results to populations with other social conditions must be done with great care.

There are also limitations given the non‐standardized definitions of ‘surgery’ in the current literature. Debas and colleagues30 defined surgery as ‘anything that requires suture, incision, excision, manipulation, or other invasive procedures’ under any type of anaesthesia. Weiser et al.31 used Debas' definition with registry data collected by OECD Health Statistics to estimate Sweden's national surgical volume as 15 610 per 100 000 population in 2012. The present study excludes superficial incisions, punctures, needle aspiration, needle biopsies, transluminal endoscopies and ultrasonography procedures related to surgery, as defined by NOMESCO, and yet 19 812 surgical procedures per 100 000 population in Sweden the same year (roughly 27 per cent more) were found23. Rose and co‐workers8 restricted the definition to inpatient procedures in the operating room from a publicly available list of over 2000 ICD codes to define surgical volume in the US Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Hider and colleagues9 limited their definition of surgery to any procedure requiring general or neuroaxial anaesthesia in the inpatient or day‐surgery setting in New Zealand's National Minimum Dataset. Because of these non‐uniform definitions, comparisons of the present results with those of other studies should be undertaken with caution. This clearly illustrates the urgent need for a uniform classification system for surgical procedures, as well as the need for clear criteria on which procedures to consider in surgical metrics, such as surgical volume and perioperative mortality rate5, 6. By including both inpatient and outpatient surgery, these findings can nevertheless serve as a public health reference for countries that seek to expand surgical coverage.

Supporting information

Table S1 Counts, incidence rate and likelihood of surgical procedures in Sweden, 2006–2013, by WHO Global Health Estimates disease category (Word document)

Table S2 Counts, incidence rate and likelihood of surgical procedures in Sweden, 2006–2013, by disease category in ICD‐10 (Word document)

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the services provided by the Swedish Board of Health and Welfare and the Swedish Patient Register in their help with data extraction. This project was funded by Lund University tuition grants and by the Swedish Research Council (grant no. 340‐2013‐5474). The funding source had no involvement in approving, planning or conducting the study.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Ng‐Kamstra JS, Greenberg S, Abdullah F, Amado V, Anderson GA, Cossa M et al Global Surgery 2030: a roadmap for high income country actors. BMJ Glob Health 2016; 1: e000011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO . Resolution A 68/15: Strengthening Emergency and Essential Surgical Care and Anaesthesia as a Component of Universal Health Coverage. World Health Assembly; 2015. http://www.who.int/surgery/wha-eb/en/ [accessed 5 April 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Meara JG, Leather AJ, Hagander L, Alkire BC, Alonso N, Ameh EA et al Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet 2015; 386: 569–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lafortune G, Balestat G, Durand A; OECD Health Division . Comparing Activities and Performance of the Hospital Sector in Europe: How Many Surgical Procedures Performed as Inpatient and Day Cases?; 2012. http://www.oecd.org/health/Comparing-activities-and-performance-of-the-hospital-sector-in-Europe_Inpatient-and-day-cases-surgical-procedures.pdf [accessed 5 April 2017].

- 5. WHO Department of Health Statistics and Information Systems . Global Reference List of 100 Core Health Indicators; 2015. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/indicators/2015/en [accessed 5 April 2017].

- 6. The World Bank . World Development Indicators 2016; 2016. https://data.worldbank.org/products/wdi [accessed 5 April 2017].

- 7. Weiser TG, Haynes AB, Molina G, Lipsitz SR, Esquivel MM, Uribe‐Leitz T et al Estimate of the global volume of surgery in 2012: an assessment supporting improved health outcomes. Lancet 2015; 385(Suppl 2): S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rose J, Chang DC, Weiser TG, Kassebaum NJ, Bickler SW. The role of surgery in global health: analysis of United States inpatient procedure frequency by condition using the Global Burden of Disease 2010 framework. PLoS One 2014; 9: e89693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hider P, Wilson L, Rose J, Weiser TG, Gruen R, Bickler SW. The role of facility‐based surgical services in addressing the national burden of disease in New Zealand: an index of surgical incidence based on country‐specific disease prevalence. Surgery 2015; 158: 44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Swedish Board of Health and Welfare [Socialstyrelsen] . Quality of the National Patient Register [Kvalite och innehåll i patientregistret]; 2009. http://www.rdk2001.se/rdk2001/dokument/Kvalitet_och_innehall_i_patientregistret.doc.pdf [accessed 5 April 2017].

- 11. Swedish Board of Health and Welfare [Socialstyrelsen] . SOSFS 13:35 Swedish Board of Health and Welfare Regulations on Reporting to the National Patient Register [Socialstyrelsens föreskrifter om uppgiftsskyldighet till Socialstyrelsens patientregister]; 2013. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2013/2013-12-23 [accessed 5 April 2017].

- 12. Swedish Board of Health and Welfare [Socialstyrelsen] . The National Patient Register [Patientregistret]; 2016. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/register/halsodataregister/patientregistret/inenglish [accessed 5 April 2017].

- 13. Statistics Sweden [Statistiska Centralbyrån] . Finding Statistics [Statistikdatabasen]; 2016. http://www.scb.se/en_/Finding-statistics/Statistics-by-subject-area/Population [accessed 1 December 2016].

- 14. Statistics Sweden [Statistiska Centralbyrån] . Population by Region, Marital Status, Age and Sex. Year 1968– 2014. Finding Statistics [Statistikdatabasen]; 2016. http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/?rxid=e0690a76-b047-42b0-96f2-7b7c9125c5f7 [accessed 1 December 2016].

- 15. The World Bank . World Bank Data Sweden; 2016. http://data.worldbank.org/country/sweden [accessed 5 April 2017].

- 16. OECD OECD Data Sweden https://data.oecd.org/sweden.htm [accessed 5 April 2017].

- 17. OECD . OECD Reviews of Healthcare Quality: Sweden 2013 https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264204799-en [accessed 4 July 2017].

- 18. Anell A. The public–private pendulum – patient choice and equity in Sweden. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ng‐Kamstra JS, Raykar NP, Lin Y, Mukhopadhyay S, Saluja S, Yorlets R et al; Global Surgery 2030. Data for the Sustainable Development of Surgical Systems: a Global Collaboration, June – September 2015; 2015. http://www.lancetglobalsurgery.org/#!indicators/o217z [accessed 5 April 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 20. OECD . OECD. Health at a Glance 2015 – OECD Indicators; 2015. http://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/health-at-a-glance-19991312.htm [accessed 16 October 2017].

- 21. Registerforskning.se. Swedish Research Council [Vetenskapsrådet] ; 2016. http://www.registerforskning.se [accessed 1 December 2016].

- 22. WHO . WHO International Classification of Diseases; 2016. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd/en [accessed 4 July 2017].

- 23. Nordic Centre for Classifications in Health Care . NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures (NSCP). Version 1.16; 2012. http://www.nordclass.se/ncsp_e.htm [accessed 1 December 2016].

- 24. Swedish Board of Health and Welfare [Socialstyrelsen] . Statistical Database for Inpatient Care Surgery [Statistikdatabas för operationer i slutenvården]; 2017. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik/statistikdatabas/operationerislutenvard [accessed 23 March 2017].

- 25. Swedish Board of Health and Welfare [Socialstyrelsen] . Statistical Database for Outpatient Surgery (Day Surgery) [Statistikdatabas för operationer i öppenvård (dagkirurgi)]; 2017. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik/statistikdatabas/operationerioppenvarddagkirurgi [accessed 23 March 2017].

- 26. WHO . WHO Methods and Data Sources for Global Burden of Disease Estimates 2000–2011 Global Health Estimates Technical Paper WHO/HIS/GHE/2013.4; 2013. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/en [accessed 1 December 2016].

- 27. Jarnheimer A, Kantor G, Bickler S, Farmer P, Hagander L. Frequency of surgery and hospital admissions for communicable diseases in a high‐ and middle‐income setting. Br J Surg 2015; 102: 1142–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rose J, Weiser TG, Hider P, Wilson L, Gruen RL, Bickler SW. Estimated need for surgery worldwide based on prevalence of diseases: a modelling strategy for the WHO Global Health Estimate. Lancet Glob Health 2015; 3(Suppl 2): S13–S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gupta S, Ranjit A, Shrestha R, Wong EG, Robinson WC, Shrestha S et al Surgical needs of Nepal: pilot study of population based survey in Pokhara, Nepal. World J Surg 2014; 38: 3041–3046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Debas HT, Gosselin R, McCord C, Thind A. Surgery In Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries (2nd edn), Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB. et al (eds). Oxford University Press: Washington DC, 2006; 1245–1259. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Weiser TG, Haynes AB, Molina G, Lipsitz SR, Esquivel MM, Uribe‐Leitz T et al Size and distribution of the global volume of surgery in 2012. Bull World Health Organ 2016; 94: 201F–209F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Counts, incidence rate and likelihood of surgical procedures in Sweden, 2006–2013, by WHO Global Health Estimates disease category (Word document)

Table S2 Counts, incidence rate and likelihood of surgical procedures in Sweden, 2006–2013, by disease category in ICD‐10 (Word document)