Abstract

Background

Child and adolescent mental health in Africa remains largely neglected. Quick and cost-effective ways for early detection may aid early intervention. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) is globally used to screen for mental health problems, but little is known about its use in Africa. We set out to perform a scoping review to examine existing studies that have used the SDQ in Africa.

Methods

A comprehensive scoping review methodology was used to identify all peer-reviewed studies ever published that have used the SDQ in Africa. Data were extracted and analysed to assess the countries, languages and SDQ versions used, the purpose of the SDQ studies, psychometric properties of the SDQ, and to consider knowledge gaps for future in-country and cross-country studies.

Results

Fifty-four studies from 12 African countries were identified, most from South Africa. Many different languages were used, but authorized SDQs in those languages were not always available on the SDQinfo website. Authors frequently commented on challenges in the translation and backtranslation of mental health terminology in African languages. The SDQ was typically used to investigate internalisation/externalization disorders in different clinical populations, and was most frequently used in the evaluation of children and adolescents affected by HIV/AIDS. Sixteen studies (29.6%) administered the SDQ to participants outside the intended age range, only 4 (7.4%) used triangulation of all versions to generate assessments, and eight studies (14.8%) used only subscales of the SDQ. Only one study conducted thorough psychometric validation of the SDQ, including examination of internal consistency and factor analysis. Where ‘caseness’ was defined in studies, UK cut-off scores were used in all but one of the studies.

Conclusions

The SDQ may be a very useful tool in an African setting, but the scoping review suggested that, where it was used in Africa researchers did not always follow instrument guidelines, and highlighted that very little is known about the psychometric properties of the SDQ in Africa. We recommend comprehensive evaluation of the psychometric properties of the SDQ in various African languages, including internal consistency, factor structure, need for local cut-off values and ensuring cultural equivalence of the instrument.

Background

Mental health disorders account for at least 14% of the global burden of disease [1], underlining its importance as a global public health concern. Three-quarters of people with mental health problems live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [2, 3], where 75–85% with severe mental health concerns receive little or no treatment [4]. This large treatment gap [5] has multiple underlying causes, including a scarcity in the number of trained mental health professionals [6], lack of advocacy and awareness, as well as the associated stigma of mental illness. When comparing mental health professional availability between high- and LMICs, Europe on average has nine psychiatrists for every 100,000 of the population, while Africa has 0.05 psychiatrists per 100,000 [7]. In addition to the limited mental health services in LMICs, there is also a lack of contextually relevant, rigorous, mental health research in many of these geographical areas [8].

Mental health problems represent the greatest burden of disease among children and adolescents [9]. Ninety percent of children and adolescents live in LMICs, yet only 10% of all child and adolescent mental health (CAMH) research has been conducted in LMICs [8]. In sub-Saharan Africa, projected to be home to 40% of the world’s children by 2025, there are only about 60 qualified child and adolescent psychiatrists and very limited CAMH services. Given the rising incidence of mental health disorders and concomitant resource deficiencies, the treatment gap in Africa is widening [10, 11].

Identification, evaluation and implementation of simple, short and freely-available screening tools for CAMH difficulties may offer a powerful strategy to close the treatment gap, as it may enable the identification of children and adolescents in need of next-step evaluation and treatment. Screening tools might be particularly useful in primary care [12] and in educational settings. Currently a number of screening tools, including the Child Behaviour Checklist [13], SNAP-IV [14], Conners’ ADHD Rating Scales [15] and Social Communication Questionnaire [16] are used in Africa, but it is not clear where or how consistently these tools are used, or to what extent these have been evaluated for their reliability, validity and cultural appropriateness for the diverse populations and contexts in Africa [17].

In CAMH settings around the globe, the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) is widely used as a behavioural screening tool, as it has several advantages. It is relatively short, allows for rapid administration, measures both mental health difficulties and competencies, and can be administered by a non-professional with minimal training [18, 19]. The SDQ was developed by Goodman and colleagues [20] in the UK as an open-access, downloadable screening tool, available as a self-report (SDQ-S), parent/caregiver (SDQ-P) and teacher report version (SDQ-T). Goodman [18] recommended the optimal use of the instrument to be a multi-informant tool, with triangulation between parent, teacher and (where appropriate) adolescent self-report. Authorized translations of the tool are available on the SDQ website (http://www.sdqinfo.org) in 83 languages. A strict process of translation, back-translation and authorisation of the tools is maintained by the authors. These processes were designed to ensure the availability of the SDQ in a number of languages whilst maintaining the integrity of the instrument.

The SDQ consists of 25 items to assess a range of ‘strengths’ and ‘difficulties’ as behavioural markers of potential mental health problems. The items contribute to five subscales of five items each with a minimum score of 0 (lowest score) to 10 (highest score): conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, emotional symptoms, peer problems, and prosocial behaviour. The sum of the first four subscales generates a total difficulties score, which can range from 0 to 40. From the total difficulties and subscale scores, cut-off scores for clinical ‘caseness’ can be generated. The top 10% of scores based on UK population norms were used to define the ‘abnormal’ range, the next 10% as the ‘borderline’ range, and the remaining 80% of scores as the ‘normal range’ [20]. A higher total difficulty score indicates a greater likelihood of significant problems. Four of the five subscales are scored in a similar way with higher scores indicating more difficulties. The prosocial subscale provides a reverse score where higher scores indicate more prosocial behaviours or strengths.

The reliability and validity of the SDQ has been examined in a number of studies across Europe [20], Asia, Australia and South America [21, 22], but with little or no reference to the use of the SDQ on the African continent. Given the growing awareness of the CAMH needs in Africa [11], it seemed timely to establish the landscape of all research ever performed in Africa that used any versions of the SDQ. We therefore set out to conduct a comprehensive scoping review of the SDQ aimed to describe the use of the SDQ, and to examine the reliability and validity of the SDQ for local use in Africa.

Methods

The methodological framework for scoping reviews [23, 24] was followed. This included identifying the research question, searching for relevant studies, selecting studies, charting and summarizing the data, and reporting the results. The review objective, inclusion criteria and study methods for this scoping review were specified in advance. Inclusion criteria were (i) any of the versions of the SDQ was used in the study, (ii) the study took place in Africa, (iii) the article was data-driven (i.e. not a review paper), and (iv) the article had been peer-reviewed. We also expressly included studies performed in any language and with no time limit since the development of the SDQ. Given that this was a comprehensive scoping review and not a systematic review, no articles were excluded on the basis of any quality criteria.

Search strategy

A literature search to identify studies that used the SDQ to evaluate CAMH in Africa since its development in 1997, was conducted until December 2016. Online databases Ebscohost (Africa Wide Information, Medline, PsycINFO) and PubMed were searched with no date limitations, or language restrictions for any African study involving use of the SDQ, in December 2016 and a follow-up search was conducted in April 2017. A general search of Google Scholar was also conducted. The databases were searched using the following keywords: ‘Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire’, ‘SDQ’, ‘Africa’, ‘children’, ‘adolescents’, and ‘mental health’. An additional search was conducted which included the use of ‘reliability’ and ‘validity’. Searches were not restricted to any search date, but included all available published studies. An additional search was conducted using key words ‘Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire’, ‘SDQ’ combined with ‘Africa’, ‘adolescents’ and ‘mental health’. The terms ‘reliability’ and ‘validity’ were also used in addition to the combination of the above terms used. Additionally, examination of relevant bibliographies provided further references for review. Titles and abstracts were examined using the inclusion criteria, after which full articles were retrieved.

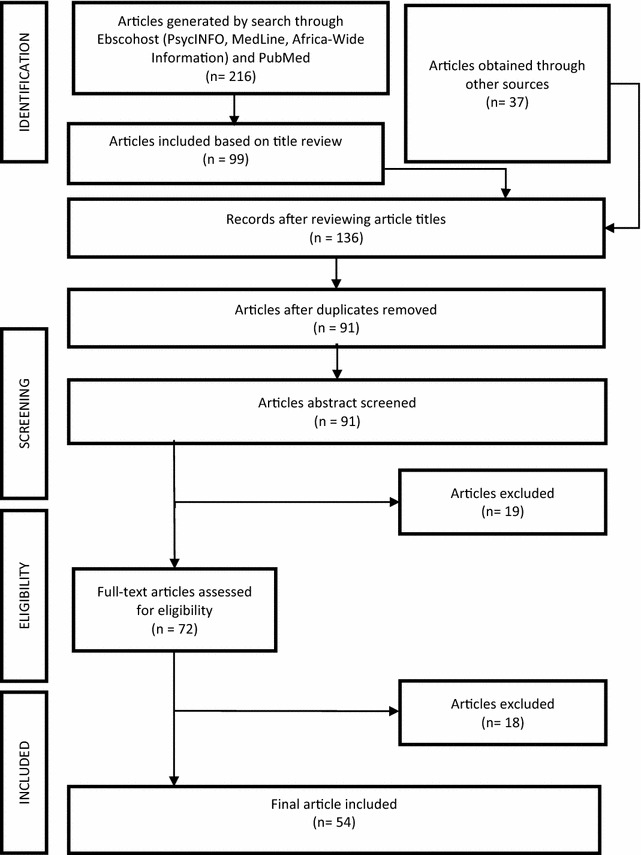

The initial online search produced 216 articles. Titles were screened for eligibility and 99 articles were identified. A further 37 articles were generated from reference lists and other sources, producing a total of 136 articles. Duplicates were removed, reducing the sample to 91 articles. The abstracts of these were then reviewed to confirm study location and use of the SDQ, producing a total of 72 articles. The 19 articles excluded in the abstract screening phase included review papers, those not conducted in Africa, and articles that used tools with the same acronym as the SDQ (e.g. self-description questionnaire). Eighteen of these were found to be review articles (not apparent from abstract review), reports, one study on African populations living outside of Africa, and presentations using the SDQ in Africa, and were thus excluded. Two independent reviewers assessed the articles for eligibility (NH, ELD). Disagreements were resolved by consensus between the reviewers and, in cases of an impasse, the two senior authors (PJdV, MSK) made the final decision. Figure 1 outlines the process involved in the literature review and final selection of articles. The final sample consisted of 54 articles included in the review (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the literature search process

Table 1.

Strengths and difficulties questionnaire in Africa: data extraction

| First author (year) | Location | Age range | Study aim | Theme | SDQ versiona | Sample | Language | Translation process | Cut-off scores | Differences to UK norms | Alpha scores/internal consistency | Results from use of the SDQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kashala (2005) [25] | Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo | 7–9 | Pilot testing examining stability of the factor structure and reliability of the SDQ | Tool validation | Teacher | 1306 learners assessed by teachers | French | None mentioned, French version from SDQ site used | Overall (gender in article) TDS = 19 Emo = 6 Conduct = 5 Hyper = 7 Peer = 5 Pros = 3 Somewhat different to British cut offs |

Higher cut-off scores for conduct and low cut-off for Pros, but similar to British cut-offs for Hyper, Emo and Peer | TSD = .81 Emo = .71 Conduct = .64 Hyper = .66 Peer = .35 Pros = .80 |

Internal consistency satisfactory on all SDQ scales. Using the 90th percentile, cut-off scores were somewhat higher than the published cut-off scores in this younger sample |

| Cluver (2006) [26] | Cape Town, South Africa | 6–19 | Examined psychological well-being and mental outcomes of children orphaned by AIDS compared to a matched, non-affected control group | HIV/AIDS, orphans, non-orphans | Self-report (read aloud in Xhosa or English to participants) | 60 children living in informal settlements | isiXhosa and English | Translated and blind back-translated | No SDQ norm cut-offs in SA (possibly used percentages to determine three bands) | Using UK cut-off scores high levels of difficulty were found in Peer, Emo and TDS | No mention of alpha scores | Orphaned children and matched controls scored highly for peer problems, emotional problems and total scores. However, orphans were more likely to view themselves as having no good friends, to have marked concentration difficulties (and to report frequent somatic symptoms but were less likely to display anger through loss of temper. Orphans were more likely to have constant nightmares, and 73% scored above the cut-off for PTSD |

| Kashala (2006) [27] | Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo | 7–9 | Explore hyperactivity–inattention symptoms and co-existing symptoms of emotional and behavioural problems in African school children and their relationship with health status, socio-demographic factors, and school performance | Hyperactivity–inattention, emotional/behavioural problems, children | Teacher | 357 children: 183 were defined as cases due to abnormal scores on the hyperactivity sub-scale, and 174 with normal hyperactivity sub-scale scores | French | None mentioned | Does not specify which cut-off scores were used | Does not specify which cut-off scores were used, nor made a comparison to UK sample | No alpha score reported | Three quarters of hyperactive-inattentive children had co-existing symptoms using SDQ with conduct problems being most common |

| Cluver (2007) [28] | Cape Town, South Africa | 10–19 | Investigated psychological consequences of AIDS orphanhood, compared to control groups of children and adolescents orphaned by other causes, and non-orphans | HIV/AIDs, orphans, non-orphans | Peer and conduct problems subscale (self-report) | 1025 children and adolescents | isiXhosa | None mentioned | Applied UK cut-off scores of borderline = 4–5, and abnormal = < 6 for peer problems. 14% of AIDS orphans, 9% other-orphans and 8% non-orphans met abnormal criteria. Conduct problems associated with orphanhood by AIDS. Conduct problems in British cut-off for abnormal was 5, and had 5% of AIDS orphans, 3% other-orphans and 4% non-orphan which was lower than what was found in UK levels of conduct problems | Used UK cut-off scores | Did not report alpha scores for two sub-scales used | Controlling for socio-demographic factors AIDS orphaned children were more likely to report symptoms of depression, peer relationship problems, post-traumatic stress, delinquency and conduct problems than both children orphaned by other causes and non-orphaned children Compared to Western norms, AIDS-orphaned children showed higher levels of internalising problems and delinquency, but lower levels of conduct problems |

| Menon (2007) [29] | Lusaka, Zambia | 11–15 | Examined emotional and behavioural difficulties in HIV positive Zambian adolescents | HIV, emotional and behavioural difficulties | Self-report; parent | 127 children and their | English and Nyanja | Translated and back-translated | Applied UK cut off scores | Zambian sample was more than twice as likely to score outside the normal range to total difficulties, 3 times more likely to have emotional symptoms and 7 times more likely to score in abnormal range for peer problems when compared with UK sample cut offs | Parent form: TDS = .54, Emo = .51, Conduct = .56, Peer = .34, Hyper = .24 Self-report: TDS = .51, Emo = .51, Conduct = .61, Peer = .31 and Hyper = .18 |

Adolescents who have not disclosed their HIV status were twice as likely to experience high emotional difficulties compared to those who disclosed their HIV status |

| Okello (2007) [30] |

Gulu District, Uganda | 11–19 | Assessed psychiatric disorders among war-abducted adolescents in northern Uganda, compared to non-abducted adolescents | Psychiatric disorders, war abducted adolescents | Self-report | 82 war-abducted and 71 non-abducted adolescents | Language not specified | None mentioned | Applied the following cut offs to the TDS (used in Goodman, 2001): 0–15 = normal, 16-19 = borderline, 20-40 = abnormal | Using Goodman’s (2001) cut offs 51.2% of the war-abducted and 18.3% of the non-abducted adolescents had significant clinical distress on the TDS | No alphas reported | War abducted adolescents had poorer emotional and behavioural adjustment as indicated by their total difficulties scores than non-war abducted adolescents |

| Cluver, Gardner, and Operario (2008) [31] | Cape Town, South Africa | 10–19 | Explore mediating effects of stigma and other factors operating on a community level, on associations between AIDS orphanhood and mental health, and associations of four risk factors that can potentially be addressed at a community level (bullying, stigma, community violence, and lack of positive activities) with psychological problems and orphanhood status | HIV/AIDs, orphanhood, stigma, community risk factors, psychological problems | Self-report peer and conduct problems subscale | 1025 children and adolescents | isiXhosa | None mentioned | Did not applied any cut-offs | Has not used UK cut-off scores to make comparisons | No alpha scores reported for the two sub-scales used | AIDS orphanhood was significantly associated with higher peer relationship problems AIDS orphanhood was significantly related to higher conduct problems but this association was eliminated when stigma was accounted |

| Elhamid, Howe, Reading (2009) [32] | Minia, Egypt | 6–12 | To conduct a population prevalence study of emotional and behavioural disorders among children in this region | Emotional and behavioural disorders | Teacher and parents | 1177 children | Arabic | None undertaken. Authors reference that the Arabic version has been previously validated | Applied UK cut-off scores | Applied UK cut-off scores | No alpha scores reported | The prevalence of reported behaviour problems by teachers and parents were much higher in Egypt than in UK |

| Cluver, Gardner, Operario (2009) [77] | Cape Town, South Africa | 10–19 | Examine associations between orphanhood, poverty, and psychological distress | HIV/AIDS, orphanhood, poverty, psychological problems | Peer and conduct problems subscale (assumed self-report) | 1025 children and adolescents: 425 AIDS orphaned, 241 non-AIDS orphans, 278 non-orphans | isiXhosa | None mentioned | Did not applied any cut-off scores, used continuous scores | Has not used UK cut-off scores to make comparisons | No alpha scores reported for the two sub-scales used | Orphan hood by AIDS was significantly related to peer problems |

| Doku (2009) [34] | Manya Krobo District, Ghana | 10–19 | Examine impact of parental HIV/AIDS status and death on child mental health | HIV/AIDS | Self-report | 200 children | English | Not applicable/none mentioned | Applied UK cut-offs did not evaluate validity of SDQ | Applied UK SDQ cut-off scores to Ghanaian sample | Did not report alpha scores | Children whose parents died of AIDS showed very high levels of peer problems whilst both orphaned groups scored similarly high on conduct problems Hyperactivity showed no difference and was very low in the entire sample Emotional problems were very high in all the groups except among the non-orphaned children |

| Menon (2009) [35] | Lusaka, Zambia | 11–15 | Assess mental health of HIV positive Zambian adolescents in comparison to a school sample and an age matched British normative sample | HIV | Self-report | 419 school learners in grades 5-9, 93 HIV positive clinical sample | English and translated version | None mentioned | Has not applied any cut-offs | Has not used UK cut-offs to make comparisons | Did not report alpha scores | Zambian HIV positive adolescents scored higher emotional symptoms and peer problems when compared to a British community sample |

| Doku (2010) [37] | Ghana | 10–18 | Assess psychosocial adjustment of children affected by HIV/AIDS | HIV/AIDS, psychosocial | Self-report | 50 AIDS orphans, 51 orphans due to other causes, 48 children living with HIV-infected parents, 51 children who did not have HIV/AIDS related deaths in family | English | Not applicable/None mentioned | Did not apply any cut-off scores | Has not used UK cut-off scores to make comparisons | Did not report alpha scores | Total difficulties fort children whose parents died of AIDS but not children whose parents died of causes other than AIDS and children whose parents are infected with HIV/AIDS, scored significantly higher than non-orphaned children whose parents are not known to be infected with HIV/AIDS |

| Bakare (2010) [36] | Nigeria | 4–18 | Assess prevalence and pattern of behavioural problems using the teacher reported SDQ among Nigerian children with intellectual disability, to associate behavioural problems with child socio-demographic variables | Behavioural problems | Teacher | 44 children with intellectual disability | Language not specified | None mentioned | Use UK cut-off scores | 47.7% were classified as borderline and abnormal for total difficulties based on TDS cut off of 12-40 | Overall alpha reported = .63 | 47.7% of children were classified as having behavioural problems in the borderline and abnormal categories on total difficulties clinical scale of SDQ using the cut-off point recommended by Goodman Mild intellectual disability (ID) as compared to moderate, severe and profound ID was associated with highest total difficulties mean score Males were more likely to exhibit conduct and hyperactivity behavioral problems compared to the females |

| Mueller (2011) [38] | Knysna, South Africa | 8–18 | Evaluated efficacy of the make a difference about art programme | HIV/AIDS | Self-report | 297 children | English, Afrikaans and isiXhosa | Translations performed by bilingual translators and back-checked for accuracy by a second bilingual translator | Did not applied any cut-off scores | Has not used UK cut-off scores to make comparisons | Presents other study’s alpha scores but not their own | Community-based art therapy intervention had no effect on emotional and behavioural problems among children affected by HIV |

| Puffer (2012) [39] | Muhuru Bay, Kenya | 10–18 | Examine orphan status, mental health, social support, and HIV risk among adolescents in rural Kenya | HIV, orphan status, mental health, social support | Self-report | 325 children | Dholuo | Translated and back-translated | Did not applied any cut-off scores | Has not used UK cut-off scores to make comparisons | Overall alpha score reported = .59 | Orphans reported poorer mental health, less social support, and fewer material resources They did not differ from non-orphans on HIV risk indicators Longer time since parental death was associated with poorer outcomes Orphan status was significantly associated with emotional problems |

| Abbo (2013) [40] | Lira, Tororo, Kaberamaido and Gulu, Uganda | 3–19 | investigated prevalence, comorbidity, and predictors of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents | Anxiety disorders | Self-report and parent | 420 households with children and adolescents | Translated into 4 dialects (not named) | Authors attempted to ensure semantic equivalence between English and local dialects. Forward and back-translation was undertaken for each dialect two teams of mental health professionals were created. The first team translated tools into the local dialect, the second team, blind to the English version, translated the local dialect version into English. A consensus meeting with the two teams was held to resolve any major differences by discussion | Assessed total difficulties score where a score of 16 and above indicated psychological distress | Used a cut-off of above 16 for TDS as an indication of ‘caseness’ | No alpha scores reported | Prevalence of anxiety disorders among children and adolescents were higher when having emotional and behavioural problems when measured using SDQ and when having an abnormal or borderline score on emotional symptoms scale |

| Cortina (2013) [42] | Mpumalanga, South Africa | 10–12 | Examine prevalence of psychological problems in children, as well as possible risk and protective factors | psychological functioning | Teacher and self-report | 1025 children in the 4th and 6th grade | English and Shangaan | Translation, back-translation and adjustment to ensure linguistic equivalence. Two members of the research team native to the area and fluent in Shangaan, one with a Master’s degree in mental health and the other a research officer, translated the questionnaires into Shangaan. Each item was discussed in detail to determine an appropriate translation. A 3rd member of the team also fluent in Shangaan back-translated the items | Did not specify which cut-off scores were used | Teachers ratings found 40% of children as having significant difficulties compared to 10% in UK samples and 17% had reported difficulties in prosocial behaviour compared to 13% in UK samples | TDS = .75, Pros = .80 | Teachers reported high levels of behavioural, emotional, conduct and attention problems, with the TDS score from the teacher report SDQ showing that over 40% of children had significant difficulties Poorer psychological outcomes were associated with socio demographic factors like living with a single mother; lower maternal education level; and being from a former refugee family (identified a risk factor) |

| Atilola (2013) [41] | Nigeria, India, Serbia, Turkey and Indonesia | 13–19 | Evaluated the prevalence, pattern, and sociodemographic correlates of self-reported mental health problems among adolescents from five countries, to inform the methodology and design of a larger scale study | Mental health | Self-report | 1894 adolescents from Nigeria, India, Serbia, Turkey and Indonesia | Not specified | Authors mention that culturally adapted versions of the SDQ for each language and culture in the participating countries were obtained from the SDQ website, “among other sources”. No further explanation of the latter statement | Used UK cut-off scores 4 | Applied standard cut offs as recommended in Goodman (1997) | Did not report alpha scores | The prevalence of self-reported mental health problems was 10.5% (range 5.8–15) with conduct and emotional problems being the most prevalent |

| Kinyanda (2013) [43] | Lira, Gulu, Tororo, and Kaberamaido in Uganda | 3–19 | Examined prevalence and risk factors of depression in childhood and adolescence in a community sample derived from four disadvantaged districts in north-eastern Uganda | Psychosocial, depression | Self-report, parent | 1587 children | Translated into four dialects, but dialects not named | Forward and back-translation was undertaken For each of the four main dialects Two teams of mental health professionals were created. The first team translated tools into the local dialect and the second team blind to the initial English version translated the local dialect version into English. A consensus meeting with the two teams to resolve major differences by discussions was held |

Assessed total difficulties score where a score of 16 and above indicated psychological distress | Used a cut-off of above 16 for TDS as an indication of ‘caseness’ | No alpha scores reported | Psychiatric co-morbidities/psychiatric problems of emotional distress (assessed by the SDQ), were independently significantly associated with depressive disorder syndromes |

| Marais (2013) [44] | Mangaung, South Africa | 7–11 | Investigated the relationship between housing conditions and the socio-emotional health of orphans and vulnerable children in South Africa | OVC | Self-report, parent and teacher | 466 orphans, 143 other vulnerable children (non-orphaned) | Sesotho | Following guidelines, the SDQ was translated independently into Sesotho by 2 Sesotho native speakers, who agreed upon a version, which a third native speaker back-translated into English. All translators met and agreed on the final version |

Applied UK cut-offs | Applied UK cut-offs | No alphas reported | Orphaned and vulnerable children (OVC) who used other types of toilet facilities (bucket or none) were less likely to have a clinically diagnosable total difficulty score when compared to those using a flush toilet OVC living in a crowded household were more likely to be clinically diagnosed by teachers with a high total difficulties score |

| Bhana (2014) [45] | Durban, South Africa | 10–13 | Evaluate a pilot randomized control trial at 2 clinical sites | HIV/AIDS, adolescent, mental health | Self-report | 74 families with a child between 10–14 years of age | isiZulu | Translated into isiZulu using standard procedures for translation and back-translation | Did not apply any cut-off scores | Has not used UK cut-off scores to make comparisons | Inter-item reliability = .42–.54 | Pre-adolescents who formed part of a family-based, 10 session, intervention saw improvements in mental health, HIV knowledge and adherence to medication |

| Devries (2014) [46] | Luwero District, Uganda | 11–14 | To report the prevalence of corporal punishment on children in Uganda and its effects on child mental health and educational outcomes | Violence, corporal punishment | Self-report | 3706 students | Unclear if both English and Luganda versions of SDQ were used | All items translated into Luganda and reviewed by a panel of teachers and “Raising Voices” staff to ensure that they would be appropriate for Ugandan child participants and school staff. Thereafter items were cognitively tested and refined iteratively in a sample of ~ 40 children and 20 school staff members from Kampala primary schools to ensure understanding and that meanings of original items were adequately captured. They then surveyed a larger sample of 697 children and 40 staff from Kampala schools to test distributions of items and to test study procedures | Cut-off scores used were highest decile formed the ‘high difficulties’, the next decile formed ‘medium difficulties’ and the remaining 80% formed the ‘low difficulties’ | Has not used UK cut-off scores to make comparisons | TDS = .70 | For girls exposure to physical violence in the past week was associated with higher levels of poor mental health using the SDQ |

| Escueta (2014) [47] | Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, India, Cambodia | 6–12 | Examined relationship between psychosocial well-being and cognitive development orphans and abandoned children (OAC) relative to non-OAC in 5 LMICs to understand factors associated with success in learning | Orphans, psychosocial well-being, cognitive development | Self-report, parent | 1480 orphaned and abandoned children | Not specified | None mentioned | Did not apply any cut-off scores | Has not used UK cut-off scores to make comparisons | Overall alpha score reported = .73 | An increase in emotional difficulties was found to be associated with delays in cognitive development |

| Lachman (2014) [48] | KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa | 10–17 | Examined the relationship between HIV/AIDS and positive parenting | HIV/AIDS, parenting | Parent | 685 parent–child dyads with AIDS-ill caregiver and 184 caregiver-child dyad orphaned by AIDS | isiZulu | Translated into isiZulu and back-translated into English | Did not apply any cut-off scores | Has not used UK cut-off scores to make comparisons | TDS = .71 | Families who had caregivers who had AIDS or AIDS-orphaned children were significantly related to less positive parenting, higher poverty, higher depression and higher child total difficulties when compared to non-affected families |

| Marais (2014) [49] | Mangaung, South Africa | 7–11 | Assess community-based responses to well-being of OVC, compared with their actual mental health to evaluate South African government’s funding approach to CBOs supporting and caring for OVC | OVC, mental health | Self-report, parent, and teacher | 465 orphans and 142 other vulnerable children | Sesotho | Adapted and translated in accordance with published guidelines for the translation of instruments in cross-cultural research | Made use of cut-offs to present % of 3 groupings of total difficulties | Does not specify which cut-off scores were used | TDS = .72 | Orphaned and vulnerable children with access to medical care reported lower total difficulties than those who had no access to medical care The more a household used its expenditure on food the higher the total difficulties |

| Skeen (2014) [51] | Malawi | 4–13 | Explore use of developmental screening tools to measure outcomes of children affected by HIV/AIDS attending community-based organisations (CBO) and to determine what types of CBO provision received by these children | HIV/AIDS, community based organizations | Carers completed a short 10- item version of the SDQ | 979 children from South Africa (824) and Malawi (155) as well as 979 caregivers/parents. | Language not specified | None mentioned | Total difficulties score ranged from 0 to 20, higher scores indicating greater behavioural and emotional pathology | Has not used UK cut-off scores to make comparisons | No alpha scores reported | Being a younger child was associated with emotional/behavioural difficulties. Boys were more likely to have higher emotional/behavioural problem scores than girls in both South Africa and Malawi |

| Sharp (2014) [50] | Free State, South Africa | 7–11 | To evaluate the construct validity of the caregiver, teacher, and self-report versions of the SDQ | Tool validation | Self-report, teacher, and parent | 466 orphans | Sesotho | Adapted and translated in accordance with published guidelines for translation of instruments in cross-cultural research | Parent-form: TDS = 13.5 Emo = 4.5/5.5 Conduct = 3.5 Hyper = 4.5 Peer = not used in this paper Pros = not used in this paper Self-report: TDS = 11.5 Emo = 4.5 Conduct = 1.5 Hyper = 2.5 Peer = not used in this paper Pros = not used in this paper |

UK cut-offs: parent-form: TDS = 17 Emo = 5 Conduct = 4 Hyper = 7 Self-report: TDS = 20 Emo = 7 Conduct = 5 Hyper = 7 Teacher-form TDS = 16 Emo = 6 Conduct = 4 Hyper = 7 |

Alphas: parent-form: TDS = .72, Emo = .60, Conduct = .66, Hyper = .30; Self-report: TDS = .62, Emo = .50, Conduct = .34, Hyper = .26; teacher-form: TDS = .84, Emo = .77, Conduct = .70, Hyper = .67 | Orphan care-givers reported cut-offs that were in line with UK cut-offs for emotional symptoms and conduct problems, but less for ADHD and total problems The orphans self-reported cut-offs were significantly lower when compared to UK cut-offs, and teacher reported cut-offs were also lower |

| Waller (2014) [52] | Western Cape and Mpumalanga, South Africa | 10–17 | Examined significant risk factors for antisocial behaviour and substance use identified in high income countries (e.g., abuse and poverty), and to determine whether they had predictive effects among South African youth | Antisocial behaviour, substance use | Self-report: conduct problem subscale used only | 3515 children | isiXhosa, isiZulu, Swati, Sotho and Shangaan | Translated and back-translated into the five languages | Did not apply any cut-off scores | Has not used UK cut-off scores to make comparisons | Conduct sub-scale alpha score (included items merged from the Child Behaviour Checklist Youth Self-report) = time 1 = .71; time 2 = .65 | 4 items from the conduct problems sub-scale was used to assess antisocial behaviour among youth that was associated with substance use over time during Time 1 of the study Experience of abuse and community violence at Time 1 predicted antisocial behaviour at Time 2 Being older and male had a significant effect on the increase in antisocial behaviour |

| Asante (2015) [53] | Accra, Ghana | 8–19 | Determine the association between psychological functioning and social and health risk behaviours in Ghanian homeless youth | Homeless youth, psychological functioning | Self-report (interviewer administered due to low literacy) | 227 homeless children and adolescents | Twi and Ga | None mentioned | Applied UK cut-offs | Applied UK cut-offs | Overall alpha score reported = .72 | Only 12.5% of the participants were not exhibiting any psychological symptoms emotional problems were reported by 68.9%, conduct problems by 73.8%, hyperactivity/inattention problems by 53.9% and 88.6% reported peer relationship problems among the homeless youth |

| Casale (2015) [33] | KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa | 10–17 | Examined role of caregiver social support as a protective factor for adolescent emotional and behavioural problems | HIV/AIDS, caregiver support | Parent version | 2477 adolescent-caregiver dyads | isiZulu | Translated into isiZulu and back-translated into English | Did not apply any cut-off scores | Has not used UK cut-off scores to make comparisons | TDS = .71; Pros = .69 | Higher caregiver education is a socio-demographic variable associated with fewer adolescent emotional and behavioral problems for all four TDS subscales Adolescent children who were female and/or orphaned had more emotional problems, while adolescents with older caregivers had fewer conduct problems Caregivers living in the urban sites reported more adolescent child peer and conduct problems, and less prosocial behaviour Lower household socio-economic status was also associated with more adolescent peer problems and less prosocial behaviour |

| Hermenau (2015) [55] | Tanzania | 6–15 | Investigate orphans’ experiences of maltreatment and stigmatization to identify factors that relate to their psychological distress | Psychological distress, maltreatment stigmatization orphans | Self-report | 89 orphaned and 89 non-orphaned children | Swahili | Translated into Swahili and back-translated into English, using established international guidelines | Did not apply any cut-off scores | Has not used UK cut-off scores to make comparisons | TDS = .63 | The main effect of neglect, abuse, and stigmatization correlated significantly positively with orphans’ internalizing and externalizing problems |

| Collishaw (2015) [54] | Cape Town, South Africa | 10–19 | Identify predictors of resilient adaptation at child, family and community levels within a group of AIDS-orphaned children, and to consider their collective influence | HIV/AIDS, orphans | Conduct subscale (self-report)S | 1025 orphaned children and adolescents | isiXhosa | Translated, back-translated and piloted | Applied UK cut-off scores of borderline = 4–5, and abnormal = < 6 for conduct | Used UK cut-off scores | Conduct = wave 1 = .32, wave 2 = .47; Peer only used in wave 1 = .47 | Resilient adaptation is associated with influences across the child, family and community level |

| Mazzucato (2015) [56] | Angola, Ghana, Nigeria | 11–21 | To analyse survey data on the psychological well-being of school children and young adults living in transnational families by comparing them with those living with their parents in their countries of origin | Psychological well-being, parent migration | Self-report | 2760 students from Ghana, 2243 students from Angola and 2168 students from Nigeria | English and Portuguese | None mentioned | Did not specify which cut-off scores were used | Does not specify which cut-offs were used | No alphas score reported | Children from transnational families (at least one member of the nuclear family lives in a different country) have higher levels of psychological distress than children who live with their parents |

| Pappin (2015) [57] | Mangaung, South Africa | 7–11 | Investigated the relationship between socio-economic status and emotional well-being and mental health of orphans | Emotional well-being, orphans | Self-report, parent, and teacher | 500 orphans | Not specified | None mentioned | TDS cut-offs: Teacher (normal = 0–11, borderline = 12–15, abnormal/clinically diagnosable = 16 and above); Caregiver (normal = 0–13; borderline = 14–16; abnormal/clinically diagnosable = 17 and above) | Applied UK cut-off scores | Teacher form: TDS = .89 Caregiver form: TDS = .72 |

Having a female caregiver, 2 daily meals were significantly associated with higher care-giver reported total difficulty scores of orphans Four daily meals, households with higher monthly expenditure and access to medical care associated with lower care-giver reported total difficulty scores of orphans Care-giver with secondary education, employed adult in home and being an older child was associated with lower teacher-reported total difficulties scores Living in a household were a family member receives an old age pension was associated with higher teacher-reported total difficulties scores |

| Profe (2015) [58] | Cape Town, South Africa | 12–17 | Examine association between mother, father, and closest grandparent involvement with South African adolescents’ mental health and substance use | Substance use, parent involvement, grandparent involvement | Self-report | 512 adolescents | English, Afrikaans and isiXhosa | None mentioned | Applied UK cut-offs for TDS and Pros | Applied UK cut-offs | Internalising problems (Emo and Peer) = .66, externalising problems (Conduct and Hyper) = .76, Pros = .66 | Mother and father involvement were both significantly negatively associated with adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems Closest grandparent involvement was not significantly associated with adolescents’ internalizing or externalizing problems Mother involvement was significantly positively associated with prosocial behaviour Closest grandparent involvement was positively associated with prosocial behaviour |

| Abdulmalik (2016) [59] | Ibadan, Nigeria | 9–14 | Assessed effect of interventions on aggressive behaviour among male primary school learners | Aggressive behaviour | Teacher | 37 Male students in the ‘primary five’ school level assigned to an intervention and control group | Not specified | None mentioned | No cut-off scores mentioned | Does not mention which cut-off scores were used and no comparison to UK norms | No mention of alpha scores | The intervention group scored higher for conduct scores than the control group, yet the differences were not significant |

| Bella-Awusah (2016) [60] | Ibadan, Nigeria | 14–17 | Determine the effects of a CBT programme on depressed adolescents | Depressed adolescents | Self-report: impact supplement of the SDQ | 40 Adolescents who scored 18 or more on the Beck Depression Inventory assigned to an intervention and control group | Both English and Yoruba. All chose English version | Iterative back-translation procedure | Impact score of 2 or more suggest difficulties in psycho-social functioning | Did not use UK cut-off scores to make comparisons | Impact = .72 | No significant differences between intervention and control group between baseline and post-intervention, however, improvement in psycho-social functioning/impact 16 weeks follow-up post intervention |

| Bhana (2016) [61] | KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa | 9–14 | Determine resilience in perinatal HIV positive adolescents in South Africa | Resilience perinatal HIV + adolescents | Parent | 177 caregiver-child dyads who were perinatally HIV infected | isiZulu version | None mentioned, isiZulu versions from SDQ site used | No cut-off scores mentioned | Does not mention which cut-off scores were used and no comparison to UK norms | Pros = .56 TDS = .71 |

Lower total difficulty scores were associated with decreased caregiver depression, lower caregiver communication difficulties, and increased self-esteem in children. Higher prosocial scores were associated with increased caregiver communication, and the use of wishful (resilient) thinking for coping in children |

| Chirwa-Mwanza (2015) [62] | Lusaka, Zambia | 10–16 | Explore associations between relational aggression and psychological well-being among perpetrators in schools in Lusaka | Aggression, psychological well-being | Self-report | 170 students in grades 6 and 8, 51% were male | Not specified | None mentioned | Not specified | Did not specify cut-off scores and no comparison made to UK norms | Reported previously published study alpha scores | No significant gender differences were found, however a significant positive associations was found between relational aggression and psychological well-being of perpetrators. Perpetrators of relational aggression were found to have higher conduct problems, peer problems and hyperactivity |

| Cortina (2016) [63] | South Africa | 10–12 | Examine cognitive interpretations and psychological functioning of children in rural South Africa | Resilience, HIV/AIDS | Prosocial behaviour subscale (self-report) Total difficulties score (teacher version) |

1025 students from a rural, socioeconomic disadvantaged area (40% were from former refugee households) | Shangaan | Translated into Shangaan, and back-translated | No cut-off scores mentioned | Does not mention which cut-off scores were used and no comparison to UK norms | Did not provide alpha scores for SDQ sub-scales | Children who had more negative cognitive interpretations had greater reported difficulties and less pro-social behaviour |

| Dow (2016) [64] | Moshi, Tanzania | 12–24 | Establish the prevalence and severity of mental health difficulties among HIV-positive adolescents and to examine the associations between mental health difficulties, stigma, ART adherence and CD4 cell count | HIV/AIDS, ART adherence | Self-report | 182 HIV-positive adolescents, just over half were female (54%) and most were attending school (75.8%) | Swahili | Translated into Swahili, and back-translated | A score of 17 or greater for TDS indicated mental health difficulties | Did not use UK cut-off scores to make comparisons | Reported previously published studies alpha scores, but not specific to this study | Mental health difficulties were prevalent in HIV-positive adolescents, and were associated with incomplete adherence to ART and stigma |

| Doku (2016) [65] | Lower Manya Krobo District, Ghana | 10–18 | Explore prevalence of child labour and the association with psychological well-being | Child labour, Orphaned and vulnerable children (OVC), HIV/AIDS | Self-report Parent |

291 children and adolescents, 51% were female | Not specified | None mentioned | Not specified | No comparison to UK norms | Not specified | Psychological symptoms were higher among children and adolescents who were orphaned by AIDS/caregivers were affected by HIV/AIDS. Children affected by HIV/AIDS (OVC) has significantly more domestic chores and care responsibilities. Child labour mediated the association between orphan status and psychological difficulties |

| Hecker (2016) [66] | Tanzania | 6–15 | Examine associations between harsh discipline, internalising mental health problems and cognitive functioning (working memory and scholastic performance) | Harsh discipline, cognitive functioning | Peer problem and emotional symptoms subscales (self-report) | 409 primary school students, 52% were male | Swahili | Translated into Swahili, and blind back-translation | Peer: a score of 4-5 indicates “enhanced levels” of peer problems, and 6 indicates abnormal levels of peer problems Emo: a score of 6 indicates “enhanced levels” of emotional problems, and a score higher than 6 indicates abnormal levels of emotional symptoms |

Did not use UK cut-off scores to make comparisons | Combined alpha score of.67 was presented | A strong relationship was established between harsh discipline and internalising problems, and were associated with lower working memory and scholastic performance |

| Hensels (2016) [67] | South Africa and Malawi | 4–13 | Examine the effect of gender on the development of children attending a community-based organisation in high HIV-affected areas and to examine associations in community-based organisation attendance and changes in gender differences | Gender differences | Parent | 979 children from high HIV-affected communities | Not specified | None mentioned | Not specified | Cut-off score not specified and made no comparison to UK norms | Not specified | Males experienced more violence, performed worse at school and more behavioural problems were prevalent than for females at baseline. At follow-up, gender differences persisted, but males reported worse quality of life than females and males were found to experience poorer educational outcomes and behaviour problems |

| Lentoor (2016) [68] | Eastern Cape, South Africa | 31.38–92.78 months (caregivers were 18 or older) | Explore associations in primary caregiver depressive symptomology and psychological functioning of children infected with HIV | Parent depression, HIV/AIDS, psychological well-being | Parent | 152 caregiver-child dyads, children were HIV-positive, 87 girls and 65 boys | Not specified | None mentioned | Not specified | Cut-off score not specified and made no comparison to UK norms | Overall alpha score of .73 | Depressive symptomology in caregivers were associated with poor psychological functioning in their children |

| Levetan (2016) [69] | Cape Town, South Africa | 13.96 (mean age) | Examine differences in maternal grandmother involvement in grandchildren between those who co-reside and those who do not, and to examine associations between co-residence status, grandmother involvement, adolescent internalising and externalising problems as well as prosocial behaviour | Grandmother involvement, adjustment | Self-report | 384 mixed race and black African Grade 8 and 9 learners, 58% were females and 27% lived in 3 generation households with grandmother | Not specified | None mentioned | Not specified | Cut-off score not specified and made no comparison to UK norms | Presented alpha scores from previously published studies | No significant differences were established between involvement of co-residing and non-residing grandmothers. Furthermore, greater maternal grandmother involvement was associated with more adolescent prosocial behaviour, and fewer internalising behaviour problems in three generation households |

| Mazzucato (2017) [70] | Ghana | 11–21 | Explore whether being in a transnational family is associated with psychological well-being | Transnational families, psychological well-being | Self-report | 2760 secondary school students from areas of high out-migration rates | Not specified | None mentioned | Not specified, just indicated that higher number indicate more psychological distress | Did not specify cut-off scores to make comparisons | The alpha scores for the sub-scales ranged from .70–.73 | Being in a transnational family was associated with lower levels of psychological well-being, only in families where parents were divorced or separated |

| Okewole (2016) [71] | Abeokuta, Nigeria | 11.6 (mean age – children) 40.4 (mean age – mothers) |

Examine the association between maternal depression and child psychopathology | Maternal mental health, child psychopathology | Self-report | 100 mother–child dyads attending a child and adolescent neuropsychiatric hospital | Yoruba | None mentioned, Yoruba version from the SDQ site used | Not specified | Did not specify cut-off scores to make comparisons | Not specified | 23% of mothers had a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. 25% of children had abnormal total difficulty scores. A diagnosis of major depressive disorder in mothers were associated with poor total difficulty SDQ scores and poor scores on all SDQ sub-scales except emotional problems |

| Okewole (2015) [78] | Abeokuta, Nigeria | 15.4 (mean age) | Establish the relationship between prodromal psychotic symptoms and psychological distress | Prodromal symptoms, mental health | Self-report | 508 secondary school students in the 10th–12th grades. | English | Not applicable/None mentioned | Applied UK cut-off scores | No comparison to UK norms were used | Overall Cronbach alpha score = .63 | The prevalence of prodromal symptoms was 20.9 and 11.8% scored abnormal scores on the emotional sub-scale, while 6% scored abnormal scores on the conduct problems sub-scale and 6% for both hyperactivity and peer problems sub-scales. Prodromal symptoms was predicted by higher total difficulty scores and difficulty sub-scales |

| Puffer (2016) [72] | Migori County, Kenya | 10–16 | Evaluate intervention aimed at improving family relationships, reduce HIV risk and promote mental health | HIV/AIDS, family relationships, mental health | Version not specified | 124 families (237 adolescents and 203 caregivers) from four churches | Not specified | None mentioned | Not specified | Did not specify cut-off scores to make comparisons | Not specified | No effects were found for the intervention on secondary outcomes such as parenting, social support and mental health |

| Skeen (2016) [73] | South Africa and Malawi | 4–13 | Establish the relationship between violence exposure and mental health among HIV-affected children | HIV/AIDS, violence, mental health | Version not specified | 989 children (834 from South Africa and 155 from Malawi) attending community-based organisations | Not specified | None mentioned | Not specified | Did not specify cut-off scores to make comparisons | Not specified | HIV-negative children who lived with a HIV-positive person experienced more violence, and was followed by HIV-positive children. Interpersonal violence in the home and community predicted internalising and externalising behaviour problems. Harsh physical discipline also predicted behavioural problems in children |

| Sherr (2016) [74] | South Africa and Malawi | 4–13 | Examine the effects of caregiver and household HIV on child development | HIV/AIDS, child development | Version not specified | 808 caregiver – child dyads, compared over having a HIV caregiver, having HIV in the household and no HIV | Not specified | None mentioned | Not specified | Did not specify cut-off scores to make comparisons | Not specified | Many negative child developmental outcomes was associated by HIV burden, and was mediated by caregiver depression levels. The familial burden of HIV at baseline affected child behavioural problem as follow indirectly as a result of depression of the caregiver. Both internalising and externalising behaviour problems were indirectly affected by familial HIV burden and caregiver depression |

| Thumann (2016) [75] | Luwero District, Uganda | 7–18 | Examine whether individual and contextual factors in the school environment were associated with mental health difficulties, including the association of mental health difficulties with violence exposure and differences by gender | School environment, violence, mental health | Self-report | 3565 primary school students | Not specified | None mentioned | Binary variable created for those above and below the 80th percentile | Did not compare to UK norms but applied rule that those above the 80th percentile would be categorised as “borderline/abnormal” as outlined by Goodman, Meltzer and Bailey (1998) | Overall Cronbach alpha score = .69 | Experiences of violence by staff or students were associated with mental health difficulties. Low school connectedness also increased the odds of mental health difficulties. Effect of violence on mental health difficulties were not mediated by school connectedness and there were no significant differences across gender. Attending an urban school increased the odds of mental health difficulties |

| Tucker (2016) [76] | KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa | 10–17 (children) Over 18 (caregiver) |

Establish the impact of caregiver ill-health and child orphan status on prosociality in HIV-affected settings | HIV/AIDS, orphans, prosocial behaviour | Prosocial behaviour sub-scale only: self-report and parent versions only | 2136 child-caregiver dyads in an HIV-epidemic community | English and isiZulu | None mentioned | Applied UK cut-off scores | Used UK cut-off scores but no comparison to UK norms | Pros (Self-report) = .89 Pros (parent version) = .69 |

Differences were found in the rating of prosocial behaviour in households where caregivers were ill and children were orphaned due to AIDS. Caregivers reported low prosocial behaviour in children, while the children rated high prosocial behaviour |

TDS total difficulties score, Emo emotional symptoms, Conduct conduct problems, Hyper hyperactivity/inattention, Peer peer problems, Pros prosocial behaviour

aSelf-report, parent or teacher version

Data extraction

Full PDF versions of all included articles were collated by the first author and analysed by the first and second author to extract relevant information for the review. A summary table was generated (Table 1) which included the following fields: author, year, study location, participant age, study samples, aim of the paper, theme of study, SDQ report version used, SDQ language version used, translation process, clinical cut-off scores used, comparison to UK norms, internal consistency of the SDQ, as well as the results of each study.

Data analysis

The data gathered and extracted from the articles were analysed using thematic analysis. In keeping with the aim of the review to examine the use and cultural appropriateness of the SDQ in Africa, the deductive themes extracted included specific examination of the location of studies, languages used, instrument translations, cultural comments about use, and psychometric properties of the instrument. Other inductive themes which emerged during extracting and synthesis of data, were research theme of use, versions and subscales used. All findings are summarised in Table 1.

Results

The review identified 54 studies [25–78], conducted in 12 African countries (Table 1). Below we summarise data based on (i) sociodemographic descriptors, (ii) SDQ versions, (iii) SDQ triangulation, (iv) tool properties and validation, (v) translation, back-translation and authorization, and (vi) the purpose of using the SDQ in Africa.

Sociodemographic descriptors

The 12 countries represented in the review included South Africa (n = 21 plus an additional 3 from two-country studies between South Africa and Malawi), Nigeria (n = 6 plus an additional study from a three-country study between Nigeria, Angola and Ghana), Ghana (n = 5, plus the additional three-country study with Nigeria and Angola), Uganda (n = 5), Tanzania (n = 3, plus an additional three-country study between Tanzania, Kenya and Ethiopia), Kenya (n = 2, plus the additional three-country study), Zambia (n = 3), Democratic Republic of Congo (n = 2), Angola (n = 1, based on the three-country study with Nigeria and Ghana), Egypt (n = 1), Ethiopia (n = 1, based on the three-country study with Tanzania and Kenya), and Malawi (n = 1, plus the additional 3 two-country studies with South Africa) (Fig. 2). As listed above, five studies represented samples from two countries, namely South Africa and Malawi in three studies, and two three-country studies, namely Tanzania, Kenya and Ethiopia as well as Nigeria, Angola and Ghana. All studies included male and female participants who ranged in age between 31 months and 24 years. Interestingly, 16 studies (29.6%) administered the self-report version to participants as young as six and as old as 24 years, despite the SDQ administration guidelines recommending the self-report version for 11–17 year olds [26, 30, 34, 37–39, 41, 42, 54–56, 62, 64, 66, 70, 75].

Fig. 2.

Geographical location of SDQ studies in Africa

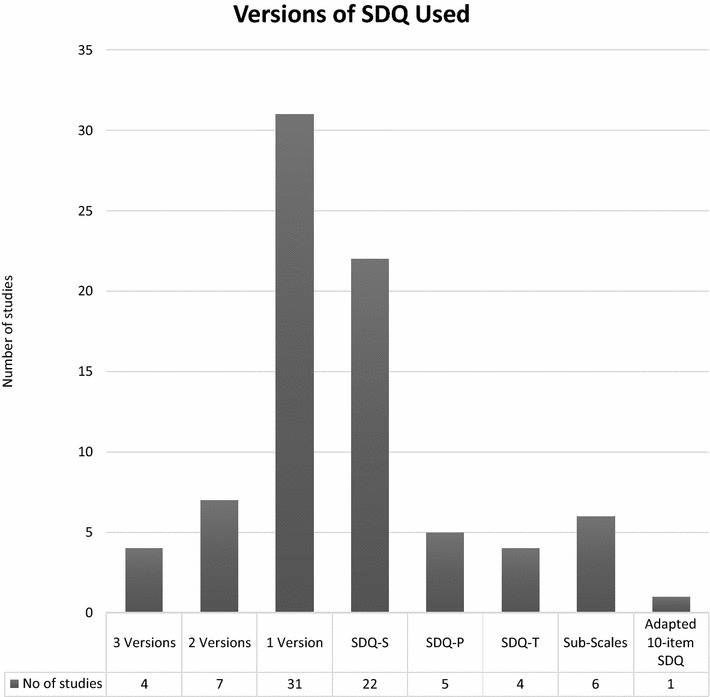

SDQ versions used

Of the 54 studies, four (7.4%) used all three versions (parent, teacher and self-report) of the SDQ [44, 49, 50, 57] (see Fig. 3). Seven studies (12.9%) employed 2 SDQ versions [29, 32, 40, 42, 43, 47, 65]. Thirty-one studies (57.4%) used only one version of the SDQ, of which 22 used the SDQ-S [26, 30, 34, 35, 37–39, 41, 45, 46, 53, 55, 56, 58, 60, 62, 64, 69–71, 75, 78], four the SDQ-T [25, 27, 36, 59] and five the SDQ-P [33, 48, 61, 67, 68] (see Table 2 for summary of results by SDQ versions). In the remaining 12 articles (22.2%), three used only the peer and conduct problem subscales from the SDQ self-report version [28, 31, 77], one used only the peer and emotional problem subscales [66], while a further two articles used only the conduct subscale of the self-report SDQ [52, 54]. In addition, the self-report prosocial subscale was used together with the parent prosocial subscale [76] and the teacher total difficulty score [63]. Three studies did not specify which version of the SDQ was used [72–74]. One study used an unauthorised modified 10-item version of the SDQ-P [51] which assessed total difficulties. Overall, the SDQ self-report version was most frequently used (32 studies, 56.1%), followed by the parent report (15 studies, 26.3%), and the teacher report version (10 studies, 17.5%).

Fig. 3.

SDQ versions used in studies from Africa

Table 2.

Summary of results by SDQ version (SDQ-S, SDQ-P and SDQ-T) used

| SDQ self-report | SDQ parent report | SDQ teacher report | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of papers identified | 35a | 18a | 10a |

| Location | South Africa (n = 9) Ghana (n = 6) Uganda (n = 5) Nigeria (n = 5) Tanzania (n = 3) Zambia (n = 3) Kenya (n = 2) Angola (n = 1) Ethiopia (n = 1) |

South Africa (n = 9) Uganda (n = 2) Egypt (n = 1) Ethiopia (n = 1) Ghana (n = 1) Kenya (n = 1) Malawi (n = 1) Tanzania (n = 1) Zambia (n = 1) |

South Africa (n = 5) Nigeria (n = 2) Congo (n = 2) Egypt (n = 1) |

| Translation process | |||

| Translated and back-translated | 15 | 5 | 1 |

| Translation guide used | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| No mention of process | 8 | 7 | 4 |

| Not applicable | 4 | 0 | 2 |

| Common themes | HIV/AIDS and orphans (n = 12) | HIV/AIDS and orphans (n = 10) | Orphans and emotional and behavioural problems (n = 6) |

| Psychometric properties | |||

| Included in study | 14 | 9 | 6 |

| No mention in study | 16 | 6 | 4 |

| Cronbach alpha score ranges | 0.18–0.80 | 0.24–0.73 | 0.35–0.89 |

aNumber includes multi-country and triangulated studies (which might inflate number of studies)

SDQ triangulation

Triangulation of SDQ data through the use of multiple informants is recommended by the developers [79]. Only four (7.4%) [44, 49, 50, 57] of the 54 studies in the review made use of all versions (parent, teacher and self-report) of the SDQ to satisfy triangulation of the screening tool. All four studies took place within South Africa, three made use of the Sesotho versions of the SDQ (parent, teacher and self-report), while the other study did not specify the language version used. The remaining 50 studies in the review did not make use of triangulation.

Psychometric properties and validation

Twenty-six studies (48.1%) included an evaluation of some aspect of the psychometric properties of the SDQ, for instance, 25 (46.2%) reported the Cronbach alpha scores for internal consistency [25, 29, 33, 36, 39, 42, 45–50, 52–55, 57, 58, 60, 61, 66, 68, 70, 71, 75, 76]. Four studies (7.4%) also presented Cronbach alpha scores from previously published studies [38, 62, 64, 69]. The overall reported Cronbach alpha scores ranged from 0.18–0.89. For the SDQ-S Cronbach alpha scores were reported in 14 studies (25.9%) and ranged between 0.18 and 0.80. Sixteen studies (29.6%) did not report on the psychometric properties for the SDQ-S. For the SDQ-P Cronbach alpha scores were reported in 9 studies (16.7%) and ranged between 0.24 and 0.73. Six studies (11.1%) did not report on psychometric properties of the SDQ-P. SDQ-T scores ranged between 0.35 and 0.89 in the 6 studies (11.1%) that reported Cronbach alphas, while four studies (7.4%) did not report on internal consistency or other psychometric properties of the SDQ-T (see summary in Table 2). One study made use of inter-item reliability on the SDQ-S [45] and another generated a composite score for all subscales used on the SDQ-S [52]. Overall, twenty-four studies (44.4%) failed to report or examine Cronbach alpha scores. One study examined the factor structure of the SDQ among children in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) using the SDQ-T, and the same study established clinical cut-off scores on the SDQ-T for the DRC population [25]. One study examined the construct validity of all three versions of the SDQ in a sample of Sesotho children and adolescents in South Africa, as well as their caregivers and teachers [50]. To do this, the SDQ was administered alongside the computerised diagnostic interview schedule for children (4th edition; CDISC-IV) to the sample and the subscales were matched with the CDISC-IV diagnostic groups based on the DSM-IV criteria [50]. The emotional problem subscale was matched to detect anxiety disorders and affective disorders on the CDISC-IV, while the conduct problem subscale was matched to detect oppositional-defiant disorder and conduct disorder. In addition, the hyperactivity/inattention subscale was matched to detect ADHD. The peer problem and prosocial behaviour scales were not matched as there were no criteria in the CDISC-IV to find matched equivalent diagnostic groups [50]. The study [50] suggested support for the SDQ-P version, but not for the SDQ-T and SDQ-S, and provided clinical cut-offs with some caution.

Translation, back-translation and authorization

With regards to translation and adaptation of the SDQ, 23 studies (42.6%) reported the process of translation and back-translation of the SDQ. Of these, eight translations were not listed as authorized on the SDQ website and have not been translated in consultation with the tool developers, namely Nyanja [29], Dholou [39], Sesotho [44, 49, 50, 52], Luganda [46], Swati [52], Shangaan [52, 63], Twi [53] and Ga [53]. Challenges raised in the process of translations and adaptions included absence of a linguistic equivalent in some of the local languages for words such as ‘fidget’ [80], ‘nervous’ or ‘fidgeting’ [35]. Of the studies in the review, the SDQ was available in seventeen different languages, while twenty studies did not specify language(s) used. Five studies, two in South Africa [26, 54] and one each in Ghana [53], Tanzania [66] and Nigeria [71] reported the use of interviewer support when using the self-report SDQ, due to low literacy levels. There are no authorised procedure at http://www.sdqinfo.com for interviewer administration of the SDQ. Of the 23 studies reporting on the translation and adaption of the SDQ, only seven provided evidence of the evaluation of translated words and its equivalences [35, 39, 40, 43, 49, 64, 66], evidence of translation team discussions regarding semantics was found in one study [46], and another used a qualitative approach to perform a cognitive review of the translated version of the SDQ [50].

In addition, three studies used English versions of the SDQ and thus did not require translation [34, 37, 78]. Of the remaining 51 studies, three used translated versions of the SDQ from the official site [25, 61, 71] and 27 did not discuss any process of translation. Elhamid and colleagues [32] did not discuss translation of the SDQ used but referenced the Arabic version that had been previously validated.

While some authors discussed the process and implications of instrument translation in both their methods and discussion, this was not universal, and showed varying degrees of detail across studies. Seventeen studies mentioned that back-translations were performed. Four studies did not provide specific details about the translation process, but rather referenced that the process was undertaken according to published guidelines or standard procedures [45, 49, 50, 55].

There is a distinct lack of consistent examination and reporting of translation processes for this tool. Devries [46] and Cortina [42] represent good examples of processes that take into account cultural appropriateness and linguistic equivalence in the translations of the SDQ. The use of trained mental health professionals who are native speakers, independent forward and blind back-translations, collaboration with teachers and staff to assess the tool, as well as pilot testing of tools in small and then bigger samples, are all steps that can be taken to assess the SDQ in a setting before use. The translation process for studies that made use of the SDQ-S commonly reported the use of a translation and back-translation process (n = 15; 27.8%), while the studies using the SDQ-P (n = 7; 13.0%) and SDQ-T (n = 4; 7.4%) more frequently did not report on the translation process (see Table 2).

Purpose of SDQ use in Africa

Use of the SDQ in Africa fell into two broad categories, (i) assessing internalising and externalising problems among children and adolescents in Africa, and (ii) assessing mental health in the context of HIV/AIDS.

Internalising and externalising problems among children and adolescents in Africa

The SDQ was used to examine internalising and externalising problems of children and adolescents in Africa in 21 of 54 studies. Some of the internalising disorders included emotional problems [27, 32, 36, 51, 59, 62], anxiety disorders [40], depression [43, 60], psychological functioning and mental health in homeless youth [53], orphans and vulnerable children exposed to maltreatment and stigma [44, 47, 55, 57], war-abducted adolescents [30], psychological well-being as it relates to parental migration [56, 70] and lack of parenting support [30]. Externalising problems examined included hyperactivity/impulsivity [27], behavioural problems [27, 32, 36, 51, 59, 62], effects of corporal punishment on mental health and educational outcomes [46, 75], antisocial behaviour and substance use [52], and caregiver association with substance use and mental health [58].

Mental health difficulties in the presence of HIV/AIDS

The majority of articles (24 of 54) identified in this review used the SDQ to explore child and adolescent mental health in the context of HIV/AIDS (17 studies from South Africa, three from Ghana, two from Zambia, Kenya and Malawi, and one from Tanzania) and compared mental health and HIV associations between orphaned and non-orphaned children in South Africa [26, 28, 31, 54, 76, 77]. Peer problems were among the common mental health difficulties for children orphaned due to AIDS [26, 28, 31, 77], followed by posttraumatic stress disorder [26, 28] and conduct problems [28, 31]. Studies included examination of emotional and behavioural difficulties in HIV positive adolescents [29, 61, 64], the impact of parental HIV/AIDS status and death on the mental health of the child [34], psychosocial adjustment of children affected by HIV/AIDS [37], evaluation of community art therapy intervention on the mental health of children affected by HIV [38], randomised controlled trials pilot evaluation [45], caregiver social support [33], positive parenting [48], and in the provision and outcomes of community-based organizations for children and adolescents [54, 67, 73, 74].

Discussion

Given the divide between need for and access to CAMH services particularly in low- and middle-income settings such as in Africa, screening tools such as the SDQ that are simple, accessible and freely-available has the real potential to improve early identification and access to care in Africa and other LMIC settings. However, for clinically-meaningful implementation, it is essential that any instrument not designed in the context should be examined to ensure it has good psychometric properties (e.g. is reliable and valid in the new context), is culturally appropriate, and is used in adherence to the guidelines of the developers of the instrument. We therefore set out to explore the current knowledge-base about the use of the SDQ in Africa.

We identified 54 peer-reviewed publications from 12 African countries, most from South Africa. The SDQ was typically used to investigate internalisation/externalization disorders in different clinical populations, including vulnerable populations such as orphans, children in war-torn areas, and migrants. Interestingly, the SDQ was most frequently used in the evaluation of children and adolescents affected by HIV/AIDS. Many different languages were used, but authorized SDQs in those languages were not always available on the official SDQinfo website. Authors frequently commented on challenges in the translation and back-translation of mental health terminology in African languages. Sixteen studies (29.6%) administered the SDQ to participants outside the intended age range, only 4 (7.4%) used triangulation of all versions to generate assessments, and 8 studies (14.8%) used only subscales of the SDQ. Where ‘caseness’ was defined in studies, UK cut-off scores were used in all but one of the studies. Only one study conducted a thorough psychometric validation of the SDQ, including examination of internal consistency, generating cut-off scores, and factor analysis [25].

The African continent is highly multi-cultural and multilingual. Screening tools such as the SDQ initially validated for a UK population, have been reported to have good psychometric properties in high-income settings [81], but, as shown in this scoping review, these findings have not been replicated in Africa. The results presented in the current review suggest that the SDQ has been used in several African countries among various groups of children and adolescents, without comprehensive validation for use in these settings. The many studies that have used the SDQ in Africa reporting limited or no validation therefore raises concerns about the robustness of findings reported in the African CAMH literature to date.

We were surprised to observe the application of the SDQ outside the scope and guidelines of the instrument. We strongly believe that all researchers who work in Africa have an ethical duty to ensure adherence to instrument guidelines and to work in collaboration with tool developers. Given the limited research resources available in Africa, we have to ensure high-quality research at all times.

An additional potential area of concern was the limited use of triangulation of measures in only four studies all conducted in South Africa. Whilst the philosophical position of the SDQ developers is to encourage triangulation of data in clinical practice, many different research questions could be answered without triangulation of data, for instance, investigation of the psychometric properties of a specific version of the SDQ [82]. We also acknowledge that the low rate of triangulated use of the SDQ may have been purely pragmatic, for instance, for the assessment of homeless youth, a self-report version may have been the only option for assessment. For this reason, we are cautious not to overinterpret the limited use of triangulation reported here. Further examination of triangulated data would, however, be of interest to examine measurement invariance between parent, teacher and self-report versions, and cross-culturally. To date, measurement invariance for the different versions of the SDQ have yielded conflicting, and ambiguous findings [83, 84].

Context-specific validation of the SDQ is crucial, as demonstrated in a recent South African study that evaluated the psychometric properties of the SDQ in 3451 adolescents aged 12–16 [82]. The results showed reasonable, yet variable, internal consistency, but identified significant gender-based differences in scores. More importantly, it showed a very unusual profile of ‘caseness’. Using UK cut-off values (designed to identify the top 10% of scorers), 26% of 12–16 year olds were found to be at high risk of emotional problems and 33.7% to be at high risk for peer problems (de Vries et al. 2017 [82], Table 3). Based on these observations, the authors raised the need for extreme caution in making cross-country comparisons. For intra-county clinical use, the study recommended the use of local cut-off scores to define clinical ‘caseness’ in any screening procedure. For example, a suggestion had been made to use the SDQ-S for mass screening as part of the South African Integrated School Health programme (personal communication, MSK). UK cut-off scores for caseness would have led to a two- to three-fold overidentification of young people ‘at risk’, which could have caused potential distress among young people, and could have placed the already very limited mental health services under overwhelming strain.

The scoping review and our recent findings [82] also raised the question about the cultural appropriateness and challenges with translation and back-translation of the SDQ to ensure valid use [85]. Africa has 2000–3000 languages, and only a handful of these have been included in SDQ translations. We suggest that it will be important to understand the local perceptions of mental health and the linguistic subtleties in the description of symptomatology, in order to evaluate how best to translate and validate instruments such as the SDQ [82, 86].

Our findings highlighted a few additional important issues. Firstly, there has been a steadily growing body of research on CAMH in Africa, suggesting a heightened awareness amongst practitioners and researchers of the need to identify and document mental health conditions. In this review we identified a significant number of articles in 2016, suggesting a recent growth spurt in research. The review further highlighted that mental health challenges for African children and adolescents often occur within contexts of significant large-scale trauma, such as in situations of conflict, conflict-linked migration and the persistent and long-standing HIV/AIDS epidemic with the accompanying personal and societal devastation. Close to 18 million children and adolescents on the African continent have been orphaned due to HIV/AIDS [87], it is therefore not surprising that 27 studies in the review examined children and adolescents’ mental health in relation to HIV/AIDS. Some studies were set among homeless children and adolescents [88] and those exposed to war [43]. This is not necessarily the case in other regions in which the SDQ had been applied. This raises the empirical question about the extent to which the SDQ, developed in a high-income setting, typically applied in a stable, non-crisis environment could, even if applied with great due diligence, be appropriate for the identification of mental health challenges in such challenging contexts.

Lessons learnt for future SDQ research in Africa

One of the key findings from our review is the importance of ensuring that use of screening tools such as the SDQ should be used in adherence with developer guidelines and authorization. Where instruments are translated without authorization, used outside the prescribed age-ranges or where only subsections or items are used, there is a real risk of incorrect and potentially misleading findings.