Abstract

Introduction:

Moderate to heavy alcohol consumption is a risk factor for all-cause mortality and cancer incidence. Although cross-sectional data are available through national surveys, data on alcohol consumption in Alberta from a large prospective cohort were not previously available. The goal of these analyses was to characterize the levels of alcohol consumption among adults from the Alberta’s Tomorrow Project in the context of cancer prevention guidelines. Furthermore, we conducted analyses to examine the relationships between alcohol consumption and other high-risk or risk-related behaviours.

Methods:

Between 2001 and 2009, 31 072 men and women aged 35 to 69 years were enrolled into Alberta’s Tomorrow Project, a large provincial cohort study. Data concerning alcohol consumption in the past 12 months were obtained from 26 842 participants who completed self-administered health and lifestyle questionnaires. We conducted cross-sectional analyses on daily alcohol consumption and cancer prevention guidelines for alcohol use in relation to sociodemographic factors. We also examined the combined prevalence of alcohol consumption and tobacco use, obesity and comorbidities.

Results:

Approximately 14% of men and 12% of women reported alcohol consumption exceeding recommendations for cancer prevention. Higher alcohol consumption was reported in younger age groups, urban dwellers, those with higher incomes and those who consumed more red meat. Moreover, volume of daily alcohol consumption was positively associated with current tobacco use in both men and women. Overall, men were more likely to fall in the moderate and high-risk behavioural profiles and show higher daily alcohol consumption patterns compared to women.

Conclusion:

Despite public health messages concerning the adverse impact of alcohol consumption, a sizeable proportion of Alberta’s Tomorrow Project participants consumed alcohol in excess of cancer prevention recommendations. Continued strategies to promote low-risk drinking among those who choose to drink could impact future chronic disease risk in this population.

Keywords: alcohol, cancer, Alberta’s Tomorrow Project, cohort, prevention guidelines

Highlights

Alcohol consumption is a risk factor for a number of chronic diseases and all-cause mortality.

Levels of alcohol consumption were reported by 31 072 participants (2001–2009) in Alberta’s Tomorrow Project cohort; a geographicallybased cohort of adults aged 35 to 69 years.

Fourteen percent of men and 12% of women reported alcohol consumption exceeding recommendations for cancer prevention.

Elevated levels of alcohol consumption were positively associated with tobacco use and other risk factors for chronic disease.

Public health messaging should continue to promote minimal intake levels of alcohol or low-risk drinking to reduce the burden of chronic disease in Alberta.

Introduction

Alcohol contributes substantially to various causes of mortality. Estimates suggest that, globally, alcohol is related to 25.8% of deaths due to injuries, 33.4% of deaths due to diabetes and cardiovascular disease, and 12.5% of cancer-related deaths.1 Regular alcohol consumption is a known risk factor for at least eight specific types of cancer, including oral cavity, esophagus, pharynx, larynx, female breast, stomach, liver and colorectum.2,3 The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has declared ethanol (the active metabolite of alcohol consumption) a Group 1 carcinogen to humans4, and there is sufficient evidence to suggest a dose-risk relationship between alcohol and adverse health outcomes, especially for cancer5-9, with no evidence of a threshold effect.2 Moreover, there does not seem to be any appreciable differences for beverage type.2 Recent population attributable risk estimates predict that 4.2% of all incident cancer cases in the province of Alberta were attributable to alcohol consumption in 2012.10

In contrast, light-to-moderate alcohol consumption has previously been shown to have cardioprotective effects11-14 and provide protection against type II diabetes15,16 and other chronic diseases.14,17 However, recent evidence has challenged these findings and suggest that there is no safe limit of consumption, especially for cancer. 18-21 Despite the controversy, identifying a safe threshold based on sound methodology which accounts for beverage type, the frequency and volume of consumption and patterns of use for alcohol remains an important research question.21 Recent reviews on the topic suggest that even light-to-moderate alcohol use may not be protective for chronic disease.21 This is contradictory to the messaging that currently exists surrounding alcohol consumption guidelines, which promote moderate alcohol consumption in those who choose to drink.3,22 Although the rates of past-year drinking among Canadians aged 15 years and older has decreased from 79% in 2004 to 76% in 2013, the rates of risky drinking behaviours have increased.23 For example, Canada’s Low-Risk Drinking Guidelines24 recommend that women consume no more than 10 drinks per week (with no more than two drinks per day) and for men to consume no more than 15 drinks per week (with no more than three drinks per day).24,25 Despite these guidelines, the proportion of Canadians who exceed lowrisk drinking guidelines continues to rise. Compared to 13.0% in 200426, 17.6%27 and 20.0%28 of those who drank alcohol (age 25 years and over) exceeded low-risk drinking guidelines for long-term health effects (e.g. cancer, epilepsy, pancreatitis, low birthweight, hemorrhagic stroke, dysrythmias, liver cirrhosis and hypertension) in 2012 and 2013, respectively.

Previous estimates of alcohol consumption prevalence in Alberta have come from national surveys on drug and alcohol use.26,28-34 Although cross-sectional data are available through national surveys, data on alcohol consumption in Alberta from a large prospective cohort were not previously available. The goal of these analyses was to characterize the levels of alcohol consumption among adults from Alberta’s Tomorrow Project in the context of cancer prevention guidelines. Additionally, we identified sociodemographic factors associated with alcohol consumption patterns, its combined prevalence with tobacco use and high-risk profiles, and evaluated the proportion of participants exceeding the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute of Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) recommendations for alcohol consumption.

Methods

Alberta’s Tomorrow Project is a prospective longitudinal cohort study established to examine the association between various lifestyle factors and chronic disease outcomes, and currently includes 55 000 Albertans aged 35 to 69 years. Detailed information on recruitment methods for Alberta’s Tomorrow Project have been published previously.35,36 In brief, Alberta’s Tomorrow Project participants were recruited by random digit dialing (RDD) between 2001 and 2009. The RDD process resulted in 63 486 interested individuals from which 48.8% enrolled into the cohort, resulting in 31 072 participants.36 Participants completed self-administered questionnaires, including the Health and Lifestyle Questionnaire, the Diet History Questionnaire37, and the Past Year Total Physical Activity Questionnaire.38,39 These questionnaires captured information about personal and family health history, cancer screening behaviours, diet and alcohol consumption, smoking habits and environmental exposures. These analyses examine only the first phase of recruited participants who completed the Health and Lifestyle Questionnaire and Diet History Questionnaire. Of the 31 072 cohort participants who enrolled between 2001 and 2009, 86% (n = 26 842) completed information on alcohol consumption.

Assessment of alcohol and variables of interest

Information on alcohol consumption was collected from 2001 to 2009 using a cognitive- based food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) developed by the United States National Cancer Institute as a tool for assessing nutrition over the preceding 12 months40 and has been adapted for use in Canada.37 The Diet History Questionnaire (DHQ) was analyzed using Diet*Calc, version 1.4.2 (Canadian version) software. The DHQ has been validated across nutrients and food groups including alcohol. Additionally, numerous other well-designed studies have employed FFQs in their assessment of alcohol consumption.12,41,42 Participants were queried about consumption frequency and volume of beer, wine/ wine coolers, and liquors/mixed drinks during the past year. The questionnaire asked separately about cans/bottles of beer (12-ounce), glasses of wine/wine cooler (5-ounce), and drinks of liquor/ mixed drinks (1.5-ounce). Each beverage type had ten frequency response categories ranging from never to six or more servings (drinks) per day over the previous year. We estimated the average amount of ethanol consumed per week using the Canadian standard of 13.6 g of ethanol in a standard drink, corresponding to approximately 341 ml of beer, 142 ml of wine, and 43 ml of liquor.43 It was not possible to garner information on heavy episodic drinking or whether participants typically drank on weekdays or weekends. We evaluated the proportion of participants who adhered to or exceeded the WCRF/AICR alcohol consumption recommendations for cancer prevention.44 Individuals were classified as those who adhered (≤ 2 drinks/day for men; ≤ 1 drink/ day for women) and those who exceeded recommendations (> 2 drinks/day for men; > 1 drink/day for women).

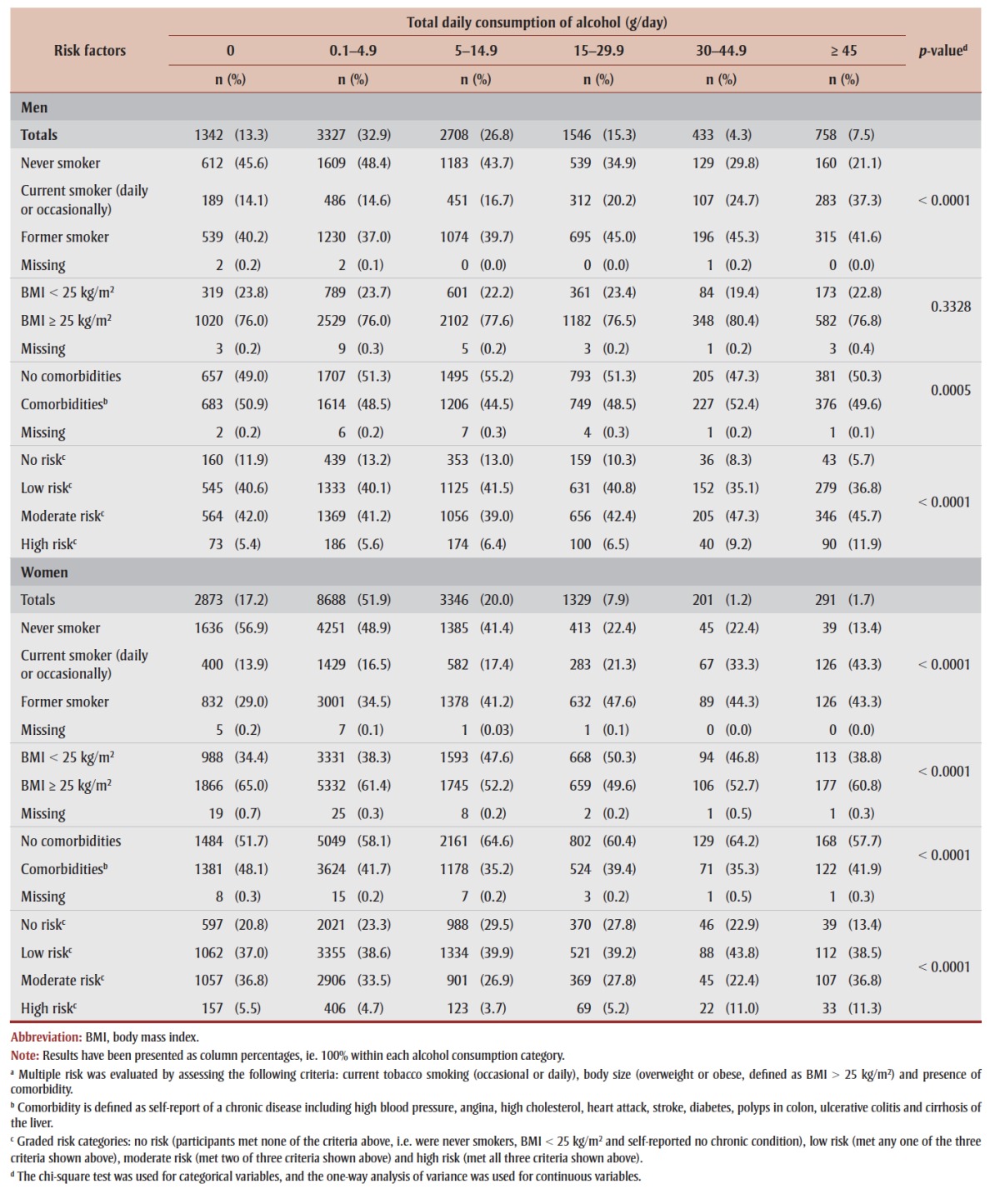

To estimate the association between alcohol consumption patterns and tobacco use, we examined the proportion of men and women who adhered to or exceeded alcohol consumption guidelines across tobacco use groups. Tobacco use was captured from participant responses to self-report questionnaires at baseline. Participants were asked about their current and former tobacco use histories and were categorized as follows: never, former, current occasional and current daily smoker. Body Mass Index (BMI) was derived from participants’ self-measured height and weight, and co-morbidity status was obtained from participants’ self-reported physician diagnoses from the baseline questionnaire. To assess prevalence of multiple risk factors, we also considered the prevalence of tobacco smoking, body size (overweight or obesity, defined as body mass index [BMI] > 25 kg/m2) and presence of comorbidity (defined as selfreport of a chronic disease including high blood pressure, angina, high cholesterol, heart attack, stroke, diabetes, polyps in the colon, ulcerative colitis, and cirrhosis of the liver). Multiple risk factors were categorized as none (participants met none of the criteria, i.e. were non-smokers, BMI < 25 kg/m2 and reported no chronic conditions), low (met any one of the three criteria), moderate (two of three criteria) and high (all three criteria were met). We then examined the proportion of men and women who were within or exceeded lowrisk drinking guidelines within these graded risk categories.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize consumption patterns within the cohort; we examined average consumption of alcohol (0, 0.1 to 4.9, 5 to 14.9, 15 to 29.9, 30 to 44.9, ≥ 45 g/day). Means and standard deviations (SD) were estimated for continuous variables, while frequencies and percentages were estimated for categorical variables. A kappa sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine the agreement between the Diet*Calc estimation of alcohol in number of drinks per day compared to grams of ethanol per day (1 drink = 13.6 g of ethanol). Pearson’s chi-square tests were used for all comparison analyses. Additionally, multivariable logistic regression models were used to assess associations between sociodemographic characteristics and WCRF drinking recommendations. Missing data represented < 1% for all included variables. Missing values were omitted from analyses. All statistical tests were performed at a 5% level of significance using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) on a Linux interface.

Results

Alcohol Consumption Patterns

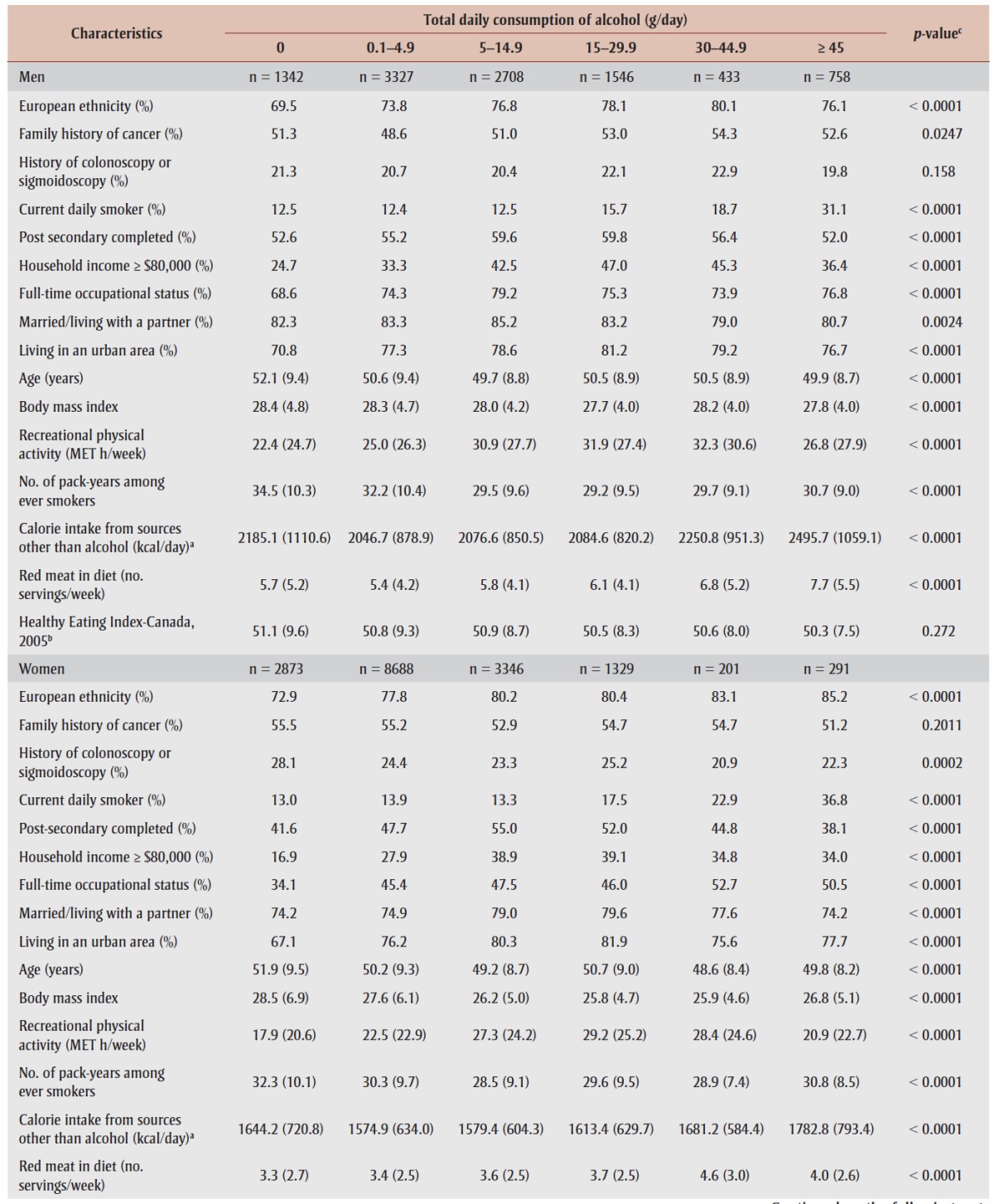

The majority of participants (84%, n = 22 627) reported consuming alcohol at some point in the preceding 12 months. Table 1 presents the proportion of Alberta’s Tomorrow Project participants in each alcohol consumption category by sex and sociodemographic characteristics. Median (IQR) consumption of alcohol was 2.1 (5.8) g/day for women and 5.9 (14.8) g/ day for men. Compared to non-drinkers, men and women who consumed alcohol tended to be younger, consume more servings of red meat, be of European ethnicity, live in an urban setting, work full-time, and have a household income that exceeded $80 000 annually. A clear positive association was observed between daily consumption of alcohol and current tobacco use for both men and women.

TABLE 1. Characteristics of participants according to reported alcohol consumption patterns (g/day).

|

World Cancer Research Fund Drinking Recommendations for Cancer Prevention

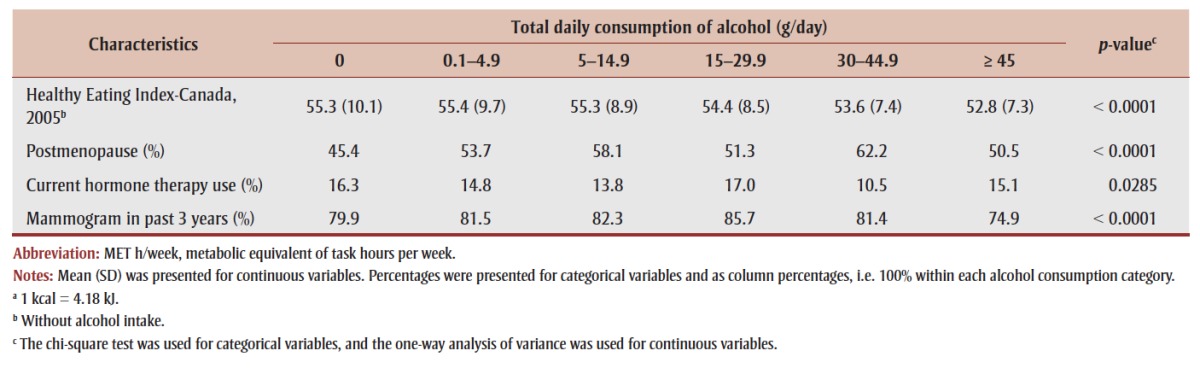

Table 2 presents the proportion of men and women that fell within or exceeded World Cancer Research Fund recommendations for personal alcohol consumption across demographic categories based on self-reported alcohol consumption. The majority (87%) of cohort participants who reported consuming alcohol in the past 12 months fell within personal recommendations for alcohol consumption, while 13% of participants consumed alcohol in excess of recommendations. Slightly fewer women exceeded the drinking guidelines compared to men (12.1% vs. 13.6%). A higher proportion of men exceeding the recommendations was observed for those who were more educated, had higher annual household incomes, who were middle aged (45 to 54 age group) and divorced/separated/widowed. Similar to men, women exceeding guidelines had higher household incomes, were employed full-time or retired, and were in the 45 to 54 year old age range.

TABLE 2. Proportion of Alberta’s Tomorrow Project participants who fall within or exceed the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research alcohol consumption recommendations by sociodemographic characteristicsa.

|

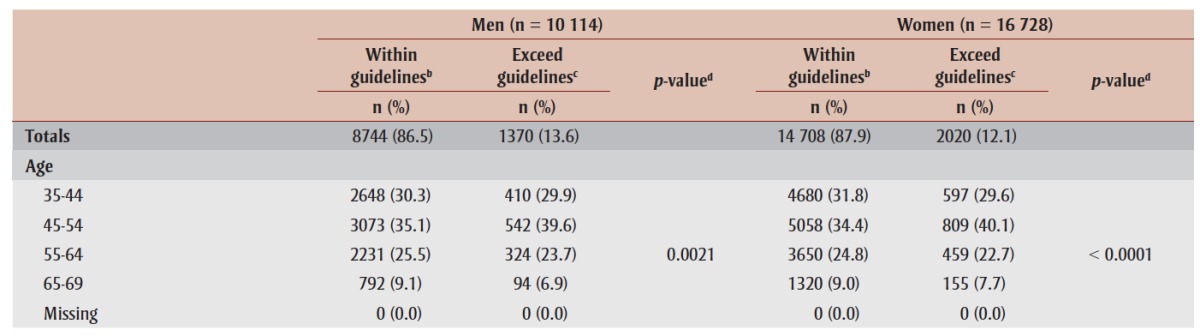

Associations between WCRF drinking guidelines and sociodemographic characteristics are presented in Table 3. Overall, men and women with higher household incomes had higher odds of exceeding WCRF drinking guidelines. Additionally, participants who had ever smoked (current daily, current occasional and former smokers) had a higher odds of exceeding WCRF drinking guidelines compared to never smokers (p < .0001). This was highest for men who were current daily smokers (OR, 95% CI, 3.61, 3.00 to 4.36) and those who were current occasional smokers (OR, 95% CI, 3.56, 2.63 to 4.82). Similar findings were observed for women who smoked daily (OR, 95% CI, 3.06, 2.62 to 3.59) and occasionally (OR, 95% CI, 3.20, 2.43 to 4.21). Women who were of non-European or mixed ethnicity were less likely to exceed guidelines compared to women of European ethnic background (OR, 95% CI, 0.66, 0.51 to 0.85).

TABLE 3. Associations between WCRF alcohol intake guidelines and sociodemographic characteristics among participants in the Alberta’s Tomorrow Project Cohort Study.

|

Drinking and other risk behaviour patterns

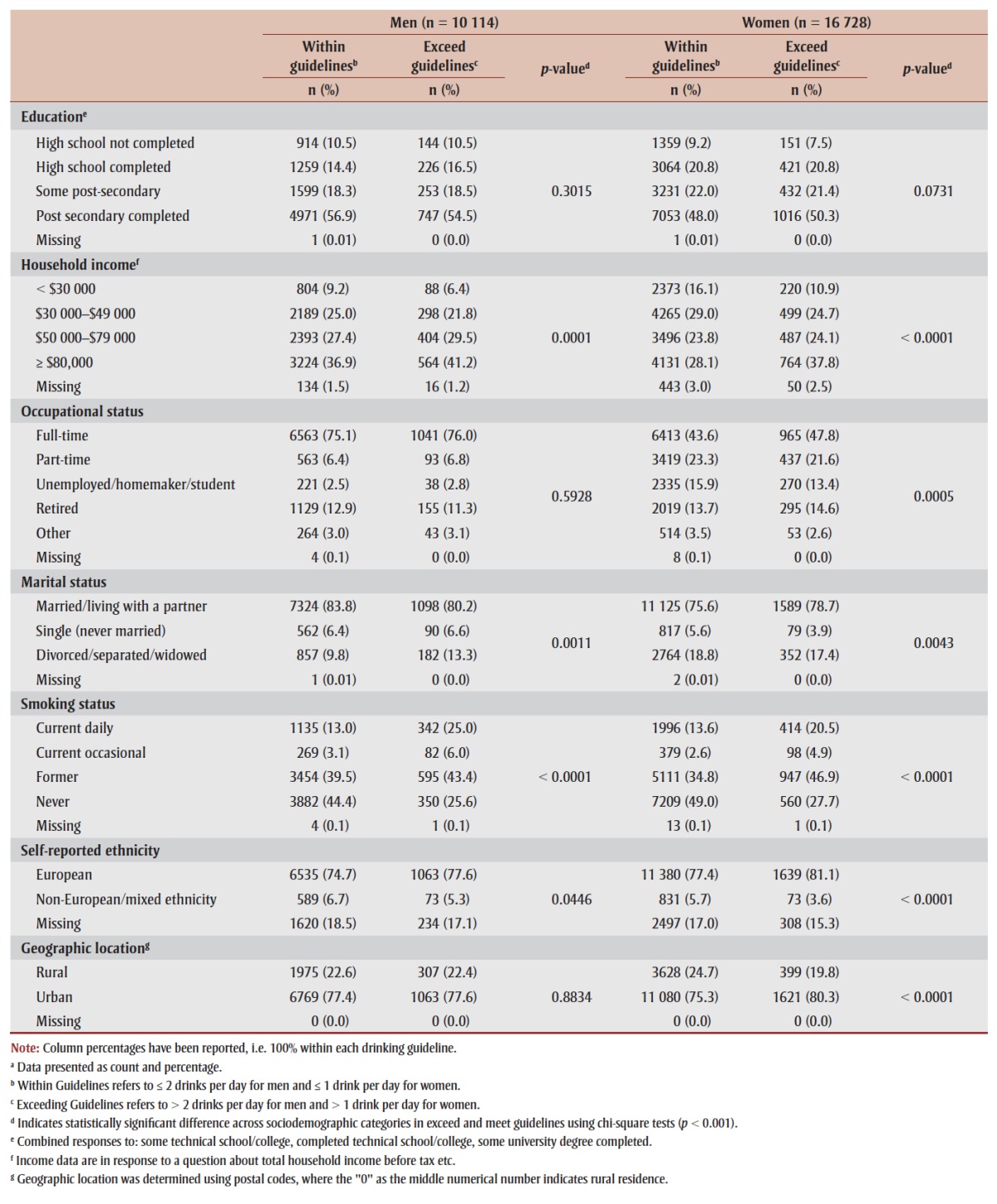

As shown in Table 4, a higher proportion of non-smokers were observed among those who did not consume alcohol. A positive association was observed between current smoking status and total daily alcohol consumption. Volume of alcohol consumption was associated with multiple risk factor categories for both men and women.

TABLE 4. The prevalence of self-reported alcohol consumption patterns and risk-related characteristics in Alberta's tomorrow Project cohorta.

|

Nearly 31.0% of men and 25.4% of women who exceeded guidelines were also current tobacco users (Table 5). The graded/multiple risk factor analysis revealed that a higher proportion of men exceeded the drinking guidelines and had moderate to high-risk profiles compared to women (56.0% vs. 34.6%). Women who exceeded guidelines showed a slightly lower prevalence of multiple risk factors compared to women who fell within the guidelines (35% vs. 37%).

TABLE 5. Prevalence of alcohol consumption WCRF drinking guidelines and risk-related characteristicsa in Alberta’s Tomorrow Project cohort.

|

Discussion

We observed that the majority of cohort participants (84%) consumed alcohol in the previous 12 months, which is slightly higher than that reported in other studies on alcohol use in Alberta (76%)45 and Canada (77.1%).46 Most participants who reported consuming alcohol in the past 12 months fell within alcohol consumption recommendations for low-risk drinking put forth by the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR). However, it should be noted that the cohort only included adults 35 years and older, which excludes those aged 20 to 34 years, known to be the heaviest drinkers in Canada.23 Globally, the prevalence of alcohol consumption is rising and remains a public health concern.1 Excess alcohol consumption is widely recognized as a contributor to adverse health outcomes.1,5,6,8,9,22,47,48 A recent meta-analysis concluded that approximately 34 000 cancer deaths worldwide could be attributed to “light” drinking (defined as: ≤ 12.5 g ethanol or ≤ 1 drink per day) in 2004.49 The adverse effects of alcohol consumption on health may be underappreciated compared to that of tobacco use, but it has been suggested that the global burden of disease attributable to alcohol was similar to that attributable to smoking exposure in the year 2000.8,48 Recent findings do not support an overall protective effect from alcohol consumption. 18,50-52 Flawed study designs have been implicated in earlier findings of “protective effects”53-58– however, a great deal of controversy on this topic remains.51,55,59-62

A large proportion of participants in this study reported light-moderate drinking (0.1 to 29.9 g of ethanol/day or < 1 to 2 drinks/day), and may be unaware of the potential harm associated with even small but regular amounts of alcohol. Further investigation into the relationship between low-risk drinking and health outcomes is essential to better characterize the exact risk-benefit threshold for alcohol consumption among different population groups. It is likely that current recommendations are not specific enough to account for inter-individual variation, susceptibility to particular disease, and tolerance thresholds.

As previously highlighted by the Pan American Health Organization and the WCRF, alcohol consumption behaviours differ considerably by sex.3,47 In the present study, men consumed alcohol more frequently and in greater quantities compared to women. Men were twice as likely to report daily drinking compared to women. This gender difference has been observed in previous population-based studies3,47 and cross-national studies,63,64 which found higher prevalence of harmful alcohol consumption profiles among men, especially with respect to total volume consumed and risky patterns of use.63-65 Similar studies have also found that alcohol- attributable disease burden (i.e. cancer, cirrhosis of the liver, neuropsychiatric disorders, etc.) is five times higher in men than women, with a mortality ratio of 10:1 compared to women.8 The higher consumption observed in men could be attributable to biopsychosocial factors.63 Similarly, we observed that men were more likely to engage in both higher rates of alcohol consumption and tobacco smoking, amplifying their risk for adverse health outcomes and disease. Both men and women who exceeded drinking guidelines were more likely to use tobacco and have overall higher risk profiles compared to those who fell within current guidelines.

Preliminary analyses from this study suggests that some chronic conditions and comorbidities may be higher among those who exceed WCRF/AICR drinking recommendations, especially for men. Therefore, healthcare providers and public policy initiatives should work within the framework of risk-reduction to determine which strategies may be most appropriate for particular groups of individuals. Interventions targeted at specific populations who are known to have “at risk” alcohol consumption patterns are needed. Given the overwhelming evidence supporting a dose-risk relationship between alcohol and chronic disease, including cancer, public health messaging should continue to focus on limiting heavy drinking and supporting low-risk drinking for individuals who choose to drink, in addition to targeting individuals who may already have a high-risk profile. Future analyses using Alberta’s Tomorrow Project will focus on investigating the association between long-term alcohol consumption patterns and incidence of cancer and other chronic diseases in this cohort.

Limitations

It is important to acknowledge several limitations of the present study. Alberta’s Tomorrow Project cohort does not include young adults (< 35 years), who have been shown to have a higher prevalence of alcohol consumption compared to middle- aged adults.31,34,66 Therefore, these estimates reflect only the adult population of Alberta between the ages of 35 and 69 years. While Alberta's Tomorrow Project was designed to be geographically representative of the adult population of Alberta, no weighted sampling strategy was used in the cohort design. Additionally, the initial recruitment through RDD methods resulted in a 48.4% response rate. It is unknown how responders differed from non-responders as no data were collected on those who did not enroll. While we believe that these results are largely generalizable to adults in Alberta, the data should not be considered representative of the Alberta population as a whole. The exclusion of Albertans under age 35 years may also account for the lower prevalence of Alberta’s Tomorrow Project participants who exceed WCRF drinking recommendations compared to other national surveillance data.31,34,66 In addition, the results of the current analyses are based on participant responses to self-report surveys. Sensitive questions, such as those related to alcohol intake, can often lead to exposure misclassification due to underestimation and underreporting of true consumption.3,8 An unpublished analysis of the 2004 Canadian Addiction Survey found that respondents indicated they only drink on average one-third of what would be expected from official alcohol sales.67 A limitation of the use of the Diet History Questionnaire for the assessment of alcohol consumption is that it does not adequately capture heavy episodic or “binge” drinking habits, which may have led to an underestimation of total alcohol consumption. Numerous other well-designed studies have assessed alcohol consumption in a similar fashion, most notably the Nurses’ Health Study41 and the Health Professionals Follow-up study12, both large ongoing prospective cohort studies.42

Conclusion

Despite the potential for underreporting, 84% of participants in the present study reported consuming alcohol in the past year. Men had a median (IQR) consumption of 5.9 (14.8) g/day of alcohol and women had a median consumption of 2.1 (5.8) g/day. Approximately 14% of men and 12% of women exceeded cancer prevention alcohol consumption recommendations. Additionally, higher volumes of alcohol consumption were found to be associated with tobacco use and elevated risk behaviour profiles in both men and women (all p < .0001). Public health messaging that continues to support minimal intake levels or low-risk drinking is essential in promoting moderation among individuals who choose to drink.

Acknowledgements

Alberta’s Tomorrow Project is only possible due to the commitment of its research participants, its staff and its funders: Alberta Cancer Foundation, Canadian Partnership Against Cancer, Alberta Cancer Prevention Legacy Fund (administered by Alberta Innovates – Health Solutions) and substantial in kind funding from Alberta Health Services. The views expressed herein represent the views of the author(s) and not of Alberta’s Tomorrow Project or any of its funders. The data product presented here from CCHS is provided ‘as-is,’ and Statistics Canada makes no warranty, either express or implied, including but not limited to, warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose. In no event will Statistics Canada be liable for any direct, special, indirect, consequential or other damages, however caused. Christine Friedenreich holds a Health Senior Scholar Award from Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions and the Alberta Cancer Foundation’s Weekend to End Women’s Cancers Breast Cancer Chair. Darren Brenner holds a Canadian Cancer Society Career Development Award in Cancer Prevention.

Conflicts of interest

There were no conflicts of interest declared.

Authors’ contributions and statement

D.R.B., P.J.R. and C.M.F. were responsible for the study conception. C.M.F., D.R.B., P.J.R., A.E.P., T.R.H. and A.A. contributed substantially to the study design and interpretation of the data. A.A. completed the analyses. D.R.B and T.R.H. were major contributors in writing the manuscript. All authors read and gave final approval of this version to be published and agreed to be guarantors of the work.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- World Health Organisation. World Health Organization. 2014;1–392 [Google Scholar]

- Danaei G, Vander Hoorn S, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, Ezzati M. Causes of cancer in the world: comparative risk assessment of nine behavioural and environmental risk factors. Lancet. 2005;366:1784–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67725-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute of Cancer Research (WCRF/ AICR). Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. World Cancer Res Fund Int. 2007;517 [Google Scholar]

- IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcvinogenic Risks to Humans PREAMBLE. IARC [Google Scholar]

- Fedirko V, Tramacere I, Bagnardi V, et al. Alcohol drinking and colorectal cancer risk: an overall and dose-response meta-analysis of published studies. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1958–72. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islami F, Tramacere I, Rota M, et al. Alcohol drinking and laryngeal cancer: overall and dose-risk relation - asystematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:802–10. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, et al. Carcinogenicity of alcoholic beverages. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:292–93. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(07)70099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Room R, Monteiro M, et al. Alcohol [Google Scholar]

- Corrao G, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, La Vecchia C. A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases. Prev Med (Baltim) 2004;38:613–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy A, Poirier AE, Khandwala F, McFadden A, Friedenreich CM, Brenner DR. Cancer incidence attributable to alcohol consumption in Alberta, Canada in 2012. Can Med Assoc J Open. 2016;4:E507–14. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20160070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimm EB, Klatsky A, Grobbee D, Stampfer MJ. Review of moderate alcohol consumption and reduced risk of coronary heart disease: is the effect due to beer, wine, or spirits. BMJ. 1996;312:731–36. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7033.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Willett WC, et al. Prospective study of alcohol consumption and risk of coronary disease in men. Lancet. 1991;338:464–68. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90542-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukamal KJ, Jensen MK, Grønbæk M, et al. Drinking frequency, mediating biomarkers, and risk of myocardial infarction in women and men. Circulation. 2005;112:1406–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.537704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins MA, Neafsey EJ, Mukamal KJ, et al. Alcohol in moderation, cardioprotection and neuroprotection: epidemiological considerations and mechanistic studies. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:206–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00828.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beulens JWJ, Van der Schouw YT. Bergmann MM, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in European men and women: Influence of beverage type and body size. The EPIC-InterAct study. J Intern Med. 2012;272:358–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf PA, Scragg RKR, Jackson R. Light to moderate alcohol consumption is protective for type 2 diabetes mellitus in normal weight and overweight individuals but not the obese. J Obes. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/634587. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/634587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arranz S, Chiva-Blanch G, Valderas- Martínez P, Medina-Remón A, Lamuela-Raventós RM, Estruch R. Wine, beer, alcohol and polyphenols on cardiovascular disease and cancer. Nutrients. 2012;4:759–81. doi: 10.3390/nu4070759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor J. Alcohol consumption as a cause of cancer. Addiction. 2016;103:153–60. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Shield K. World Cancer Report 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Klatsky AL, Udaltsova N, Li Y, Baer D, Nicole Tran H, Friedman GD. Moderate alcohol intake and cancer: the role of underreporting. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:693–9. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0372-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toma A, Paré G, Leong DP. Alcohol and cardiovascular disease: how much is too much? Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2017;19:13. doi: 10.1007/s11883-017-0647-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, et al. Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk : a comprehensive dose-response. Br J Cancer. 2014;112:580–93. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. The Chief Public Health Officer's Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2015: Alcohol Consumption in Canada. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1469605310365110. [Google Scholar]

- Butt P, Beirness D, Gliksman L, Paradis C, Stockwell T. Alcohol and health in Canada: A summary of evidence and guidelines for low-risk drinking. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00342.x. Available from: http:// www.ccsa.ca . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Canada’s Low Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines. Alcohol Drink Guidel. 2013;4–5 [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. Health Canada. Available from: http://www.ccsa.ca/ResourceLibrary/ccsa-004804-2004.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. Health Canada. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps /drugs-drogues/stat/_2012/tables -tableaux-eng.php#t9_fnb1-ref . [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Statistics Canada. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/12-591-x/2009001/02-step -etape/ex/ex-census-recensement-eng.htm . [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Statistics Canada. Available from: http://www23 .statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function =getSurvey&Id=135927 . [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Statistics Canada. Available from: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb /p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&Id =22642 . [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. Health Canada. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/drugs -drogues/stat/_2008/summary -sommaire-eng.php . [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. Health Canada. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/drugs -drogues/stat/_2009/summary -sommaire-eng.php . [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. Health Canada. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/drugs -drogues/stat/_2010/summary -sommaire-eng.php . [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. Health Canada. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/drugs -drogues/stat/_2011/summary -sommaire-eng.php . [Google Scholar]

- Bryant H, Robson PJ, Ullman R, Friedenreich C, Dawe U. Population-based cohort development in Alberta, Canada: a feasibility study. Chronic Dis Can. 2006;27:51–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson PJ, Solbak N, Haig T. Cohort profile: design, methods, and demographics from phase I of Alberta’s Tomorrow Project cohort. Can Med Assoc J Open 4. 2016;E515–E527 doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20160005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csizmadi I, Kahle L, Ullman R, et al. Adaptation and evaluation of the National Cancer Institute’s Diet History Questionnaire and nutrient database for Canadian populations. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10:88–96. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007184287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedenreich CM, Courneya KS, Bryant HE. The lifetime total physical activity questionnaire: development and reliability. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:266–74. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199802000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedenreich CM, Courneya KS, Neilson HK, et al. Reliability and validity of the Past Year Total Physical Activity Questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:959–70. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. Diet History Questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- Mostofsky E, Mukamal KJ, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Rimm EB. Key findings on alcohol consumption and a variety of health outcomes from the Nurses’ Health Study. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:1586–91. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci EL. Light to moderate intake of alcohol, drinking patterns, and risk of cancer: results from two prospective US cohort studies. BMJ. 2015;351:h4238. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Toronto (ON):: 2012 [accessed 4 Jan 2017]. Alcohol. [Internet]. . Available from: http://www .camh.ca/en/hospital/health_ information/a_z_mental_health_and _addiction_information/alcohol /Pages/alcohol.aspx . [Google Scholar]

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Washington DC, American Institute for Cancer Research: 2007. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. http://dx.doi.org/978-0-9722522-2-5. [Google Scholar]

- Alberta Health Services. Alcohol and Health: Alcohol and Alberta. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Alcohol. [Google Scholar]

- Alcohol, gender, culture and harms in the Americas: PAHO Multicentric Study final report. [Internet]. Pan American Health Organization. Washington, DC, 2007 [accessed January 4, 2017] . Available from: http://www.who.int /substance_abuse/publications/alcohol _multicentric_americas.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373:2223–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, et al. Light alcohol drinking and cancer: A meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:301–08. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikritzhs T, Fillmore K, Stockwell T. A healthy dose of scepticism: four good reasons to think again about protective effects of alcohol on coronary heart disease. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009;28:441–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikritzhs T, Stockwell T, Naimi T, reasson S, Dangardt F, Liang W. Has the leaning tower of presumed health benefits from ‘moderate’ alcohol use finally collapsed? (editorial). Addiction. 2015;110:726–27. doi: 10.1111/add.12828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockwell T, Naimi T. Study raises new doubts regarding the hypothesised health benefits of ‘moderate’ alcohol use. Evid Based Med. 2016;21:156. doi: 10.1136/ebmed-2016-110407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekjaer HO. Alcohol-a universal preventive agent? A critical analysis. Addiction. 2013;108:2051–57. doi: 10.1111/add.12104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimi TS, Stockwell T, Zhao J, et al. Addiction. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/add.13451. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson R, Broad J, Connor J, Wells S. Alcohol and ischaemic heart disease: probably no free lunch. Lancet. 2005;366:1911–12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67770-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimi TS, Brown DW, Brewer RD, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and confounders among nondrinking and moderate-drinking U.S. adults. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:369–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg IJ. To drink or not to drink? N Engl J Med. 2003;348:163–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe020163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimi TS, Xuan Z, Brown DW, Saitz R. Confounding and studies of ‘moderate’ alcohol consumption: the case of drinking frequency and implications for low-risk drinking guidelines. Addiction. 2013;108:1534–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roerecke M, Rehm J. Alcohol consumption, drinking patterns, and ischemic heart disease: a narrative review of meta-analyses and a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of heavy drinking occasions on risk for moderate drinkers. BMC Med. 2014;12:182. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0182-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockwell T. A reply to Roerecke & Rehm: Continuing questions about alcohol and health benefits. Addiction. 2013;108:428–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockwell T, Chikritzhs T. Commentary: Another serious challenge to the hypothesis that moderate drinking is good for health? Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:1792–94. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann MM, Rehm J, Klipstein- Grobusch K, et al. The association of pattern of lifetime alcohol use and cause of death in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:1772–90. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack RW, Vogeltanz ND, Wilsnack SC, et al. Gender differences in alcohol consumption and adverse drinking consequences: cross-cultural patterns. Addiction. 2000;95:251–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95225112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, Kristjanson AF, Vogeltanz-Holm ND, Gmel G. Gender and alcohol consumption: patterns from the multinational GENACIS project. Addiction. 2009;104:1487–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02696.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, Wilsnack SC, Kantor LW. The influence of gender and sexual orientation on alcohol use and alcohol-related problems: toward a global perspective. Alcohol Res. 2016;38:121–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawka E, Huebert K, Malcolm C, Phare S, Adlaf E. Canadian Addiction Survey 2004: provincial differences-alcohol. [Google Scholar]

- Stockwell T, Zhao J, Thomas G. Should alcohol policies aim to reduce total alcohol consumption? New analyses of Canadian drinking patterns. Addict Res Theory. 2009;17:135–51. [Google Scholar]