Abstract

Egl-9 family hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)3/prolyl hydroxylase 3 (EGLN3/PHD3) serves a role in the progression and prognosis of cancer. PHD3 is able to induce apoptosis in HepG2 cells. In the present study, the protein levels of PHD3 and HIF2α were analyzed by western blot analysis and immunohistochemistry in 84 paired hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tissues and adjacent non-tumor liver tissues. The mRNA levels of PHD3 and HIF2α were analyzed by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. PHD3 was overexpressed in HCC tissues compared with adjacent liver tissues (mRNA expression: P<0.001; protein expression: P=0.003; immunohistochemistry positive rate: P=0.001). The high level of expression of PHD3 in HCC tissues was associated with good differentiation (mRNA expression: P=0.002; protein expression: P<0.001) and small tumor size (mRNA expression: P<0.001; protein expression: P=0.002). In addition, HIF2α expression was lower in HCC tissues compared with adjacent liver tissues (mRNA expression: P<0.001; protein expression: P=0.002; immunohistochemistry positive rate: P=0.002). No statistically significant associations were identified between HIF2α expression and clinicopathological characteristics. Pearson's and Spearman's correlation coefficients revealed no correlation between HIF2α and PHD3 expression in HCC. In conclusion, PHD3 expression acts as a favorable prognostic marker for patients with HCC. There is no correlation between PHD3 and HIF2α expression in HCC.

Keywords: prolyl hydroxylase 3, hypoxia-inducible factor 2α, hepatocellular carcinoma, prognosis, apoptosis

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common histological subtype of liver cancer, is the fifth most frequently diagnosed malignancy in males worldwide and the seventh most commonly diagnosed carcinoma in females (1). The cancer-related mortality rate of HCC ranked second in men and sixth in women (1). In total, ~85% of HCC cases have occurred in developing countries (2). The incidence of HCC has increased in certain low-incidence countries (2). Furthermore, the prognosis of HCC is poor, with a 5-year survival rate of 11% (3). Therefore, predictive and prognostic factors for the diagnosis and treatment of HCC should be identified.

Hypoxia is widely observed in numerous solid tumors, including HCC. Hypoxic regions may induce abnormal vascular structure, poor vascular permeability and blood shunting (4). Furthermore, hypoxia is able to facilitate tumor progression and resistance to chemoradiation therapy (5). Therefore, hypoxia is a key factor in enabling tumor cells to adapt to a decreased oxygen microenvironment (6).

Transcription factors and hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs), including HIF1α, HIF2α and HIF3α, regulate gene expression in numerous tumor cells to adapt to a microenvironment of reduced oxygen (7). HIF1α and HIF2α are highly expressed in a number of types of cancer, indicating the important roles of these HIFs. However, the role of HIF2α in HCC remains controversial (8–12). A number of studies have reported that HIF2α overexpression is associated with poor prognosis (8–10), however Sun et al (11) reported the opposite results. Previously, Yang et al (12) revealed that there was no correlation between HIF2α and prognosis in patients with HCC.

HIF degradation is performed using HIF prolyl hydroxylase 1–3 (PHD1-3) enzymes under normoxic conditions (13). PHDs consist of three types: PHD1 [Egl-9 family hypoxia-inducible factor 2 (EGLN2)], PHD2 (EGLN1) and PHD3 (EGLN3). Among these PHDs, PHD3 is most efficient at regulating HIF2α compared with other HIFs (14,15). However, these studies were performed in vitro under normal oxygen conditions. It is well established that cancer is a chronic hypoxic process (16). The present study aimed to explore the association between PHD3 and HIF2α expression in HCC (under hypoxic conditions). Several studies have demonstrated that PHD3 serves a novel role in the progression and prognosis of cancer (15–24); PHD3 is also able to induce apoptosis and inhibit proliferation in cancer cells (22–29). To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to report that PHD3 overexpression induces apoptosis and inhibits growth and proliferation in HCC cells. However, no reports are available regarding the expression and prognostic significance of PHD3 in patients with HCC. In addition, the potential correlation between PHD3 and HIF2α under hypoxic conditions remains unclear. In the present study, the association of PHD3 and HIF2α expression with clinicopathological characteristics was analyzed in 84 patients with HCC, and the correlation between PHD3 and HIF2α was evaluated.

Materials and methods

Patients and tissue samples

Tumor and adjacent non-tumor liver tissues were obtained from 84 patients with HCC who underwent curative surgery between January 2012 and May 2013 at the Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical University (Guangdong, China). The selection criteria were as follows: i) Patients with HCC provided written informed consent; ii) sample diagnosis was confirmed by two pathologists; iii) the patients had not received any anticancer therapy prior to surgery and iv) they had not suffered from a second cancer type. Paired tumor tissues and adjacent non-tumor liver tissues for immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis were fixed in 4% buffered formaldehyde at room temperature for 24 h and processed into paraffin blocks. The samples for the western blot and reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) assays were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for 5 min after surgical removal and then stored at −80°C. The age, sex, tumor size, tumor, node and metastasis (TNM) stage (30), α-fetoprotein (AFP) level, Edmondson grade and portal vein tumor thrombus were all recorded (Tables I–III). The present study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical University.

Table I.

Association between PHD3 expression and clinicopathological parameters in HCC.

| PHD3 mRNA (RT-qPCR) | PHD3 protein (western blotting) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Cases | mRNA 2−ΔΔCq | t-value | P-value | Protein expression | t-value | P-value |

| Age, years | |||||||

| <50 | 64 | 8.586±1.861 | 1.228 | 0.223 | 1.032±0.279 | 0.916 | 0.362 |

| ≥50 | 20 | 7.980±2.128 | 0.967±0.273 | ||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 70 | 8.390±1.926 | −0.536 | 0.594 | 1.008±0.282 | −0.617 | 0.539 |

| Female | 14 | 8.695±2.015 | 1.058±0.259 | ||||

| Tumor size, cm | |||||||

| ≤5 | 52 | 9.042±1.898 | 3.939 | <0.001b | 1.089±0.284 | 3.254 | 0.002a |

| >5 | 32 | 7.465±1.574 | 0.897±0.225 | ||||

| AFP | |||||||

| <400 | 52 | 8.282±2.017 | −0.963 | 0.338 | 0.985±0.276 | −1.341 | 0.184 |

| ≥400 | 32 | 8.700±1.786 | 1.068±0.277 | ||||

| TNM stage | |||||||

| I–II | 60 | 8.287±2.092 | −1.161 | 0.249 | 1.003±0.309 | −0.712 | 0.479 |

| III–IV | 24 | 8.827±1.424 | 1.050±0.179 | ||||

| Edmonson | |||||||

| I–II | 46 | 9.030±1.788 | 3.242 | 0.002a | 1.109±0.248 | 3.627 | <0.001b |

| III–IV | 38 | 7.730±1.880 | 0.903±0.272 | ||||

| Portal vein tumor thrombus | |||||||

| No | 72 | 8.425±2.010 | −0.184 | 0.854 | 1.017±0.297 | 0.047 | 0.963 |

| Yes | 12 | 8.537±1.444 | 1.013±0.117 | ||||

P<0.01

P<0.001 (Student's t-test). PHD3, prolyl hydroxylase 3; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; TNM, tumor, node and metastasis; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction; AFP, α-fetoprotein.

Table III.

Association between HIF2α expression and clinicopathological parameters in HCC.

| HIF2α mRNA (RT-qPCR) | HIF2α protein (western blotting) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Cases | mRNA 2−∆∆Cq | t-value | P-value | Protein expression | t-value | P-value |

| Age, years | |||||||

| <50 | 64 | 0.602±0.124 | 0.519 | 0.605 | 0.884±0.488 | 0.782 | 0.436 |

| ≥50 | 20 | 0.586±0.110 | 0.792±0.351 | ||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 70 | 0.603±0.119 | −0.705 | 0.483 | 0.884±0.473 | 0.945 | 0.348 |

| Female | 14 | 0.578±0.129 | 0.757±0.375 | ||||

| Tumor size, cm | |||||||

| ≤5 | 52 | 0.592±0.128 | −0.619 | 0.537 | 0.865±0.504 | 0.066 | 0.947 |

| >5 | 32 | 0.609±0.109 | 0.858±0.382 | ||||

| AFP | |||||||

| <400 | 52 | 0.604±0.120 | 0.554 | 0.581 | 0.887±0.420 | 0.625 | 0.533 |

| ≥400 | 32 | 0.589±0.122 | 0.822±0.503 | ||||

| TNM stage | |||||||

| I–II | 60 | 0.604±0.124 | 0.637 | 0.526 | 0.887±0.469 | 0.773 | 0.442 |

| III–IV | 24 | 0.585±0.123 | 0.801±0.435 | ||||

| Edmonson | |||||||

| I–II | 46 | 0.611±0.126 | 0.509 | 0.304 | 0.919±0.522 | 0.010 | 0.217 |

| III–IV | 38 | 0.584±0.125 | 0.794±0.362 | ||||

| Portal vein tumor thrombus | |||||||

| No | 72 | 0.604±0.119 | 0.829 | 0.351 | 0.877±0.446 | 0.734 | 0.465 |

| Yes | 12 | 0.568±0.128 | 0.772±0.543 | ||||

Statistical comparisons between two groups were performed using the Student's t-test. HIF2α, hypoxia-inducible factor 2α; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction; TNM, tumor, node and metastasis; AFP, α-fetoprotein.

RT-qPCR assay

Total RNA was extracted from snap-frozen paired tumor and adjacent non-tumor liver tissues using TRIzol (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), and complimentary DNA was synthesized using a PrimeScript® RT reagent kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. qPCR was performed using SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II (Takara Bio, Inc.). Gene-specific primer pairs were designed and synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The following primers were used in this study: β-actin forward, 5′-CTGTGCCCATCTACGAGG-3′ and reverse, 5′-ATGTCACGCACGATTTCC-3′; PHD3 forward, 5′-CATCAGCTTCCTCCTGTC-3′ and reverse, 5′-CCACCATTGCCTTAGACC-3′; HIF2α forward, 5′-TGCGACTGGCAATCAGCT-3′ and reverse, 5′-CACCACGGCAATGAAACC-3′. The thermocycling conditions were as follows: One cycle at 95°C for 30 sec and 40 cycles at 95°C for 5 sec and at 60°C for 34 sec. Data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCq method (31).

Western blot analysis

Total proteins were extracted from paired tumor and adjacent non-tumor liver tissues using radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China). The protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Protein samples (30 µg) mixed with loading buffer were loaded on to a 10% SDS-PAGE gel, which was then transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Following blocking with 5% milk at room temperature for 2 h, the membranes were incubated with the corresponding primary antibodies (HIF2a, 1:400, ab8365; PHD3, 1:500, ab77610 Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and GAPDH (1:1,000, Abcam, ab9484) at 4°C overnight and a secondary antibody [horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled Goat Anti-Rat IgG; cat. no. a0192, 1:1,000, Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology] at room temperature for 2 h in turns. The bands were detected by BeyoECL Plus (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Finally, the blot was imaged using the VersaDoc 5000 Imager (Quantity one software; version 4.6.9; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) and scanned for the relative value of protein expression in grayscale using ImageJ software (version 1.45; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Immunohistochemical assay

Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded blocks were cut into 4 µm-thick sections and baked at 60°C for 2 h. These sections were deparaffinized twice in xylene for 12 min and then rehydrated with a gradient of ethanol solution. Antigen retrieval was performed using a citric acid buffer in a microwave for 10 min, and endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by 3% H2O2 at room temperature for 15 min. Afterwards, the sections were incubated with the corresponding primary antibodies (HIF2a, 1:150, ab8365; PHD3, 1:150, ab77610) overnight and a secondary antibody (HRP-labeled Goat Anti-Rat IgG, cat. no. a0192, 1:1,000, Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China) at room temperature for 30 min in turns. The sections were stained with diaminobenzidine reagent (DAB; Boster Biological Technology, Ltd., Wuhan, China) at room temperature for 10 min and hematoxylin at room temperature for 2 min. Sections were visualized using the positive signal of The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, rehydrated with a gradient of ethanol, treated with xylene, and then embedded in neutral resin.

The immunoreactivity of PHD3 and HIF2α was evaluated as follows: Five random microscopic fields were observed using light microscopy at ×400 magnification (CKX41; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The percentage of immune-stained cells were counted, and the mean percentages and intensities were calculated. The score was based on the percentage of immune-staining cells (0, <10%; 1, 10–30%; 2, 31–60%; and 3, >61%). Another four-grade scoring scale was performed on the basis of the intensities of immune-staining cells (0, lack of any immunoreactivity; 1, light-yellow; 2, yellow-brown; and 3, brown). The final score was calculated (percentage of immune-staining cells × staining intensity of immune-staining cells) as negative (0–3) or positive (≥4).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 17.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The values are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical comparisons between two groups were performed using the χ2 or Student's t-test. Furthermore, correlations between PHD3 and HIF2α were assessed using Pearson's or Spearman's correlation coefficient. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Finally, experimental charts were created using GraphPad Prism (version 5; GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

Association between PHD3 expression and clinicopathological characteristics in HCC

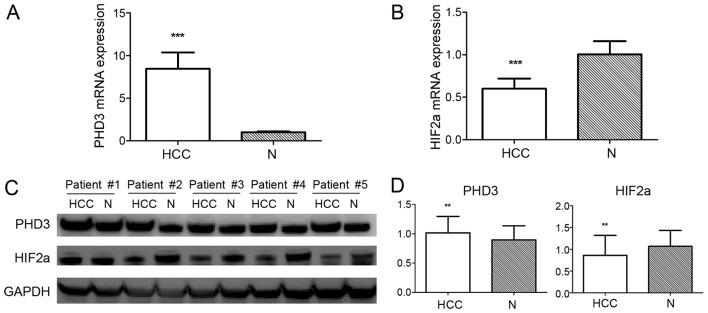

The mRNA and protein expression levels of PHD3 were evaluated from 84 paired tissues by RT-qPCR and western blot analysis, respectively. The mRNA and protein expression levels of PHD3 were significantly higher in HCC tissues compared with adjacent non-tumor liver tissues (average mRNA expression: 8.441±1.932 vs. 1.000±0.123, P<0.001; average protein expression: 1.016±0.278 vs. 0.896±0.241, P=0.003; Fig. 1). Subsequently, the association between PHD3 expression and clinicopathological parameters in HCC was analyzed (Table I). The mRNA and protein expression levels of PHD3 were negatively associated with tumor size (mRNA, P<0.01; protein, P=0.002) and Edmonson grade (mRNA, P=0.002; protein, P<0.001). Furthermore, no significant association was detected between PHD3 expression and other clinicopathological parameters, including age, sex, AFP, TNM stage and portal vein tumor thrombus status.

Figure 1.

PHD3 and HIF2α expression in HCC and adjacent non-tumor liver tissues. (A) PHD3 mRNA expression performed by qPCR demonstrated a higher average expression in HCC than in adjacent non-tumor liver tissues. (B) Low average expression of HIF2α mRNA in HCC tissues compared with adjacent non-tumor liver tissues determined by RT-qPCR. (C) Western blot analysis of PHD3 and HIF2α protein expression in HCC and adjacent non-tumor liver tissues. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (D) Average expression of PHD3 and HIF2a protein in HCC tissues compared with adjacent non-tumor liver tissues. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n=84). ***P<0.001 and **P<0.01 vs. N (Student's t-test). PHD3, prolyl hydroxylase 3; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; N, adjacent non-tumor liver tissues; HIF2α, hypoxia-inducible factor 2α; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

The positive rate of IHC staining in 84 paired HCC tumor tissues and non-cancerous tissues revealed a significantly higher expression of PHD3 in HCC tissues compared with non-cancerous tissues (P=0.001; Fig. 2; Table IV). Furthermore, PHD3 expression was negatively associated with the tumor size (P<0.001; Table II) and Edmonson grade (P=0.001; Table II). No significant associations were observed between PHD3 expression and other clinicopathological characteristics.

Figure 2.

IHC staining of HCC and adjacent non-tumor tissues. (A) Positive for anti-PHD3, where strong cytoplasmic immunoreactivity (brown) of PHD3 is observed in HCC cells. (B) Negative for anti-PHD3 in HCC cells. (C) Positive for anti-PHD3, where strong cytoplasmic immunoreactivity (brown) of PHD3 is observed in adjacent non-tumor liver cells. (D) Negative for anti-PHD3 in adjacent non-tumor liver cells. (E) Positive for anti-HIF2α, where strong brown staining is observed in the cytoplasm of HCC cells. (F) Negative for anti-HIF2α in HCC cells. (G) Positive for anti-HIF2α, where strong brown staining is observed in the cytoplasm of adjacent non-tumor liver cells. (H) Negative for anti-HIF2α in adjacent non-tumor liver cells. Magnification, ×400. IHC, immunohistochemical; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; PHD3, prolyl hydroxylase 3; HIF2α, hypoxia-inducible factor 2α.

Table IV.

Immunohistochemistry positive rates of PHD3 and HIF2α.

| PHD3 | HIF2α | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rates | HCC tissues | Adjacent non-tumor tissues | HCC tissues | Adjacent non-tumor tissues | ||

| Positive (n) | 56 | 34 | 34 | 54 | ||

| Negative (n) | 28 | 50 | 50 | 30 | ||

| Positive rate (%) | 66.7 | 40.5 | 40.5 | 64.3 | ||

| χ2 | 11.583 | 9.545 | ||||

| P-value | 0.001a | 0.002a | ||||

P<0.01. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; PHD3, prolyl hydroxylase 3; HIF2α, hypoxia-inducible factor 2α.

Table II.

Association between PHD3 and HIF2α expression and clinicopathological parameters in HCC (detected by immunohistochemistry).

| PHD3 | HIF2α | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | + | − | +% | χ2 | P-value | + | − | +% | χ2 | P-value |

| Age, years | ||||||||||

| <50 | 44 | 20 | 68.8 | 0.525 | 0.469 | 26 | 38 | 40.6 | 0.002 | 0.960 |

| ≥50 | 12 | 8 | 60.0 | 8 | 12 | 40.0 | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 48 | 22 | 68.6 | 0.686 | 0.408 | 28 | 42 | 40.0 | 0.040 | 0.842 |

| Female | 8 | 6 | 57.1 | 6 | 8 | 42.9 | ||||

| Tumor size, cm | ||||||||||

| ≤5 | 42 | 10 | 80.8 | 12.216 | <0.001b | 26 | 26 | 50.0 | 2.844 | 0.092 |

| >5 | 14 | 18 | 43.8 | 8 | 24 | 25.0 | ||||

| AFP | ||||||||||

| <400 | 32 | 20 | 61.5 | 1.615 | 0.204 | 24 | 28 | 46.2 | 1.826 | 0.177 |

| ≥400 | 24 | 8 | 75.0 | 10 | 22 | 31.2 | ||||

| TNM stage | ||||||||||

| I–II | 38 | 22 | 63.3 | 1.050 | 0.306 | 26 | 34 | 43.3 | 0.712 | 0.399 |

| III–IV | 18 | 6 | 75.0 | 8 | 16 | 33.3 | ||||

| Edmonson | ||||||||||

| I–II | 38 | 8 | 82.6 | 11.629 | 0.001a | 22 | 24 | 47.8 | 2.280 | 0.131 |

| III–IV | 18 | 20 | 47.4 | 12 | 26 | 31.6 | ||||

| Portal vein tumor thrombus | ||||||||||

| No | 46 | 26 | 63.9 | 1.750 | 0.186 | 30 | 42 | 41.7 | 0.296 | 0.586 |

| Yes | 10 | 2 | 83.3 | 4 | 8 | 33.3 | ||||

+, Positive; -, Negative; +%, Positive rate

P<0.01

P<0.001. PHD3, prolyl hydroxylase 3; HIF2α, hypoxia-inducible factor 2α; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; TNM, tumor, node and metastasis; AFP, α-fetoprotein.

Association between HIF2α expression and clinicopathological characteristics in HCC

A total of 84 paired tissues were subjected to RT-qPCR and western blot analyses. The average expression of HIF2α significantly decreased in HCC tissues in comparison with non-tumor tissues (average mRNA expression: 0.599±0.121 vs. 1.005±0.155, P<0.001; average protein expression: 0.862±0.458 vs. 1.067±0.369, P=0.002; Fig. 1). IHC staining of the 84 paired sections of HCC and non-tumor tissues demonstrated that the HIF2α expression of HCC was lower compared with non-tumor tissues (P=0.002; Fig. 2; Table IV). Subsequently, the effect of HIF2α expression on the clinicopathological parameters of the patients was analyzed. No statistically significant associations were identified between HIF2α expression and the clinicopathological parameters considered in the present study (Tables II and III).

Correlation between PHD3 and HIF2α

Pearson's correlation coefficient was calculated to determine the correlation between the average mRNA and protein expression of PHD3 and HIF2α. No statistically significant correlations were identified between PHD3 and HIF2α mRNA expression (r=0.004 and P=0.968) or protein expression (r=0.052 and P=0.642). In addition, Spearman's coefficient analysis revealed no statistically significant correlation between the IHC staining results of PHD3 and HIF2α (r=−0.137 and P=0.213).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to evaluate the prognostic effect of PHD3 on HCC. RT-qPCR, western blot analysis and immunohistochemistry were performed and PHD3 expression was demonstrated to be higher in HCC tissues compared with adjacent non-tumor liver tissues. Decreased expression of PHD3 was identified to be associated with poor differentiation and large tumor size. To date, numerous studies have revealed that PHD3 is associated with a favorable prognosis (15–19,22,24). For instance, Peurala et al (15) assessed the IHC expression of PHD3 in 102 breast cancer samples and revealed that the decreased expression of PHD3 correlates with poor differentiation, high proliferation and large tumor size. Tanaka et al (17) demonstrated that high PHD3 expression is correlated with a favorable recurrence-free survival in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Furthermore, Chen et al (19) identified that PHD3 is upregulated in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and this observation is associated with early-stage cancer and good differentiation. Xue et al (24) also revealed that PHD3 expression decreases in colorectal cancer and is associated with poor tumor grade and metastasis. In gastric cancer, high PHD3 expression correlates with good differentiation and with a favorable tumor grade and size (18,22). By contrast, Gossage et al (21) demonstrated that PHD3 exhibits a trend toward an unfavorable overall disease-specific survival in pancreatic cancer. Andersen et al (20) also reported that high PHD3 expression is associated with poor disease-specific survival in NSCLC.

Given the increasing number of observational studies on PHD3, considerable attention has been focused on the mechanism of PHD3 (17,18,24–28). Su et al (18) revealed that PHD3-induced apoptosis is dependent on nerve growth factor by activating caspase-3 in pancreatic cancer. Furthermore, PHD3 is able to inhibit cell growth by blocking β-catenin/T-cell factor signaling in gastric cancer and suppressing the inhibitor of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) kinase β subunit/NF-κB signaling in colorectal cancer (22,24). PHD3 is also able to be regulated by the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway in renal cell carcinoma (17).

Recent studies have demonstrated that PHD3 suppresses tumor growth by regulating the epidermal growth factor receptor activity (26,27). In our previous study, a vector containing the PHD3 gene was transfected into HepG2 cells and PHD3 overexpression was revealed to inhibit cell proliferation and induce apoptosis by activating caspase-3 (28). Furthermore, stably PHD3-overexpressing HepG2 cells were injected into nude mice and the average tumor size of the PHD3 overexpression group was identified to be larger compared with the control group (25). Accordingly, the functions of PHD3 were confirmed by the present study.

Numerous studies have reported the correlation of HIF2α with carcinogenesis and tumor progression. However, the mechanism underlying HCC remains inconsistent. Bangoura et al (8) reported that a high expression of HIF2α correlates with poor clinicopathological characteristics and a short cumulative survival. Sun et al (11) demonstrated that a high expression of HIF2α induces apoptosis through the TFDP3/E2F1 pathway and correlates with an increased overall survival. Notably, Yang et al (12) identified no association between HIF2α and clinicopathological characteristics, overall and disease-free survival. The results of the present study were similar to those of Yang et al (12). Additionally, the correlation between PHD3 and HIF2α expression was analyzed in the present study. RT-qPCR, western blot analysis and immunoreactivity analyses were performed and no statistically significant correlation was identified between PHD3 and HIF2α expression. Furthermore, HIF degradation was previously conducted using HIF PHD enzymes under normoxic conditions (13). However, the activation of PHD3 may be inhibited under the chronic hypoxic conditions of HCC. Additionally, PHD3 may be associated with another pathway. Our previous study revealed that PHD3 overexpression could not regulate HIF2α expression in HpG2 cells (28). Furthermore, Tanaka et al (17) demonstrated that PHD3 is able to be regulated by the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway independently of HIF proteins in renal cell carcinoma. Therefore, PHD3-induced apoptosis may independently affect HIF2α proteins in HCC.

In conclusion, the present study assessed PHD3 and HIF2α expression in 84 paired HCC and adjacent non-tumor liver tissues. The high average expression of PHD3 was associated with good differentiation and small tumor size. Therefore, PHD3 expression acts as a favorable prognostic marker for patients with HCC. No correlation was identified between PHD3 and HIF2α expression in HCC.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by grants from the Science and Technology Innovation Fund of Guangdong Medical College (grant no. STIF201126) and the Excellent Master's Thesis Fostering Fund of Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical College (grant no. YS1108).

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1264–1273, e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blechacz B, Mishra L. Hepatocellular carcinoma biology. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2013;190:1–20. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-16037-0_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Webb JD, Coleman ML, Pugh CW. Hypoxia, hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF), HIF hydroxylases and oxygen sensing. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:3539–3554. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0147-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stegeman H, Span PN, Kaanders JH, Bussink J. Improving chemoradiation efficacy by PI3-K/AKT inhibition. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40:1182–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis: Therapeutic implications. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1182–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197111182852108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Semenza GL. Defining the role of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in cancer biology and therapeutics. Oncogene. 2010;29:625–634. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bangoura G, Liu ZS, Qian Q, Jiang CQ, Yang GF, Jing S. Prognostic significance of HIF-2alpha/EPAS1 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3176–3182. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i23.3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tong WW, Tong GH, Chen XX, Zheng HC, Wang YZ. HIF2α is associated with poor prognosis and affects the expression levels of survivin and cyclin D1 in gastric carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2015;46:233–242. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Putra AC, Eguchi H, Lee KL, Yamane Y, Gustine E, Isobe T, Nishiyama M, Hiyama K, Poellinger L, Tanimoto K. The A Allele at rs13419896 of EPAS1 is associated with enhanced expression and poor prognosis for non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0134496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun HX, Xu Y, Yang XR, Wang WM, Bai H, Shi RY, Nayar SK, Devbhandari RP, He YZ, Zhu QF, et al. Hypoxia inducible factor 2 alpha inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma growth through the transcription factor dimerization partner 3/E2F transcription factor 1-dependent apoptotic pathway. Hepatology. 2013;57:1088–1097. doi: 10.1002/hep.26188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang SL, Liu LP, Jiang JX, Xiong ZF, He QJ, Wu C. The correlation of expression levels of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in hepatocellular carcinoma with capsular invasion, portal vein tumor thrombi and patients' clinical outcome. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44:159–167. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyt194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruick RK, McKnight SL. A conserved family of prolyl-4-hydroxylases that modify HIF. Science. 2001;294:1337–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.1066373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Appelhoff RJ, Tian YM, Raval RR, Turley H, Harris AL, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Gleadle JM. Differential function of the prolyl hydroxylases PHD1, PHD2 and PHD3 in the regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38458–38465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peurala E, Koivunen P, Bloigu R, Huaapasaari KM, Jukkola-Cuorinen A. Expressions of individual PHDs associate with good prognostic factors and increased proliferation in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133:179–188. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1750-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michiels C, Tellier C, Feron O. Cycling hypoxia: A key feature of the tumor microenvironment. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1866:76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanaka T, Torigoe T, Hirohashi Y, Sato E, Honma I, Kitamura H, Masumori N, Tsukamoto T, Sato N. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-independent expression mechanism and novel function of HIF prolyl hydroxylase-3 in renal cell carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140:503–513. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1593-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su C, Huang K, Sun L, Yang D, Zheng H, Gao C, Tong J, Zhang Q. Overexpression of the HIF hydroxylase PHD3 is a favorable prognosticator for gastric cancer. Med Oncol. 2012;29:2710–2715. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen S, Zhang J, Li X, Luo X, Fang J, Chen H. The expression of prolyl hydroxylase domain enzymes are up-regulated and negatively correlated with Bcl-2 in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;358:257–263. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-0976-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersen S, Donnem T, Stenvold H, Al-Saad S, Al-Shibli K, Busund LT, Bremnes RM. Overexpression of the HIF hydroxylases PHD1, PHD2, PHD3 and FIH are individually and collectively unfavorable prognosticators for NSCLC survival. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gossage L, Zaitoun A, Fareed KR, Turley H, Aloysius M, Lobo DN, Harris AL, Madhusudan S. Expression of key hypoxia sensing prolyl-hydroxylases PHD1, −2 and −3 in pancreaticobiliary cancer. Histopathology. 2010;56:908–920. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cui L, Qu J, Dang S, Mao Z, Wang X, Fan X, Sun K, Zhang J. Prolyl hydroxylase 3 inhibited the tumorigenecity of gastric cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2014;53:736–743. doi: 10.1002/mc.22025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu QL, Liang QL, Li ZY, Zhou Y, Ou WT, Huang ZG. Function and expression of prolyl hydroxylase 3 in cancers. Arch Med Sci. 2013;9:589–593. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2013.36987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xue J, Li X, Jiao S, Wei Y, Wu G, Fang J. Prolyl hydroxylase-3 is down-regulated in colorectal cancer cells and inhibits IKKbeta independent of hydroxylase activity. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:606–615. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou Y, Liang QL, Ou WT, Liu QL, Zhang XN, Li ZY, Huang X. Effect of stable transfection with PHD3 on growth and proliferation of HepG2 cells in vitro and in vivo. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:2197–2203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henze AT, Garvalov BK, Seidel S, Cuesta AM, Ritter M, Filatova A, Foss F, Dopeso H, Essmann CL, Maxwell PH, et al. Loss of PHD3 allows tumours to overcome hypoxic growth inhibition and sustain proliferation through EGFR. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5582. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garvalov BK, Foss F, Henze AT, Bethani I, Gräf-Höchst S, Singh D, Filatova A, Dopeso H, Seidel S, Damm M, et al. PHD3 regulates EGFR internalization and signalling in tumours. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5577. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang QL, Li ZY, Zhou Y, Liu QL, Ou WT, Huang ZG. Construction of a recombinant eukaryotic expression vector containing PHD3 gene and its expression in HepG2 cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2012;31:64. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-31-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Su Y, Loos M, Giese N, Hines OJ, Diebold I, Görlach A, Metzen E, Pastorekova S, Friess H, Büchler P. PHD3 regulates differentiation, tumour growth and angiogenesis in pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:1571–1579. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sobin LH, Wittekind C. International Union Against Cancer (UICC), corp-author . TNM classification of malign ant tumors. 6th. New York: Wiley-Liss; 2002. pp. 81–83. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]