Abstract

Objective

To investigate government state and local spending on public goods and income inequality as predictors of the risks of dying.

Methods

Data on 431,637 adults aged 30–74 and 375,354 adults aged 20–44 in the 48 contiguous US states were used from the National Longitudinal Mortality Study to estimate the impacts of state and local spending and income inequality on individual risks of all-cause and cause-specific mortality for leading causes of death in younger and middle-aged adults and older adults. To reduce bias, models incorporated state fixed effects and instrumental variables.

Results

Each additional $250 per capita per year spent on welfare predicted a 3-percentage point (−0.031, 95% CI: −0.059, −0.0027) lower probability of dying from any cause. Each additional $250 per capita spent on welfare and education predicted 1.6-percentage point (−0.016, 95% CI: −0.031, −0.0011) and 0.8-percentage point (−0.008, 95% CI: −0.0156, −0.00024) lower probabilities of dying from coronary heart disease (CHD), respectively. No associations were found for colon cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; for diabetes, external injury, and suicide, estimates were inverse but modest in magnitude. A 0.1 higher Gini coefficient (higher income inequality) predicted 1-percentage point (0.010, 95% CI: 0.0026, 0.0180) and 0.2-percentage point (0.002, 95% CI: 0.001, 0.002) higher probabilities of dying from CHD and suicide, respectively.

Conclusions

Empirical linkages were identified between state-level spending on welfare and education and lower individual risks of dying, particularly from CHD and all causes combined. State-level income inequality also predicted higher risks of dying from CHD and suicide.

Worldwide, the Great Recession of the late 2000s led governments to enforce the biggest fiscal constraints in decades in response to massive budget shortfalls. In the US, since 2007, the pressures to rein in public spending triggered substantial budget cuts in 46 of 50 states spanning welfare, education, health care, and services for the elderly and disabled.1 Meanwhile, income inequality, the divide between the rich and poor, has surged in many western developed nations particularly in the US (in 45 states2) over the past three decades, reaching levels last witnessed at the time of the Great Depression.3

The size and scope of social safety nets and non-health government spending are conceivably related to population health. For example, countries in Scandinavia are characterized by larger, more comprehensive welfare states and longer average life expectancies compared to other developed nations,4 although part of these differences have been attributed to variations in countries’ investments in primary care.5 Government spending on public goods such as education and social assistance (e.g., cash transfers, job training) may improve socioeconomic conditions (e.g., income, employment), especially among those of low income, and thereby may serve as investments in the non-medical social determinants of health—the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age.6–8 Yet studies of social spending and health are sparse, and all have been ecological and cross-sectional in design, thus preventing causal inference. As a whole, these studies show mixed empirical evidence for linkages between non-medical public spending and health.9–11 Furthermore, the health argument has been largely neglected in the public discourse surrounding spending cuts in social safety nets.

By contrast to social safety nets and social spending, income inequality has been posited to be harmful to average population health. Proposed mechanisms include the detrimental effects of absolute poverty, since greater income inequality means that a higher proportion of the population is poor; the stress experienced by low to even middle-income individuals based on social comparisons with the rich; and the weakening of social cohesion and ties as the gap widens between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’.12–16 Overall, the evidence suggests modest adverse effects on average of higher within-country income inequality on individual mortality;12,16–19 with mixed findings as to whether these associations are stronger among those with low income20 or those of high income.21

While randomized experiments are generally regarded as the gold standard for establishing causal relationships, as might in principle be used to estimate the effects of social spending and income inequality on health/mortality, experimental studies are often not feasible or ethical at a large population scale (e.g., entire states), thereby limiting the generalizability of their findings.22 Meanwhile, observational studies on social spending and income inequality, that comprise the evidence to date, are plagued by serious biases including residual confounding and reverse causation, collectively referred to as “endogeneity”23—arising from the lack of random variation in an exposure. Fixed effects analysis and instrumental variable (IV) analysis are two established statistical methods that can help to address endogeneity.23 State fixed effects (FE; dummy variables using longitudinal data across two or more time periods) can reduce confounding by factors at the state level that do not vary over time. Instrumental variables are factors that are correlated with the exposure of interest and are also associated with the outcome of interest but only through their association with the exposure i.e., they are “exogenous” and not a confounder of the exposure-outcome association. By isolating random variation in the exposure,23 instrumental variables can yield less biased estimates of the causal association between an exposure and outcome.24 Such approaches to strengthen causal inference are increasingly being used to better estimate the roles of risk factors in public health including obesity, neighborhood conditions, the social environment, and state policies.24–28

Using a large, representative cohort of adults in the continental United States, this study estimated the impacts of US state and local public spending (welfare, education, health, total) and income inequality on the risks of dying from major causes, while accounting for key state- and individual-level determinants of death. FE and IV analysis were implemented to strengthen causal inference. Furthermore, this study assessed whether the associations for social spending and income inequality varied by individual age and level of household income.

METHODS

Individual-level data were drawn from the US National Longitudinal Mortality Study (NLMS),29 a random sample of the non-institutionalized American population derived from 11 Current Population Survey (CPS) surveys (government household surveys conducted between 1979 and 1987, with average response rates of 90%), linked to the National Death Index (NDI), a national mortality database.30 Linkages were successful for >98% of respondents. The survey samples were combined and considered equivalent to one large sample drawn on April 1, 1983. Original weights were re-weighted using raking to better reflect the population distribution for each state by age, sex, and race. Individuals with survey weights greater than the 99th percentile were excluded. The primary study sample consisted of 431,637 adults aged 30–74 in the 48 contiguous US states. For the analyses of deaths from external injuries and suicide, the age range was modified to those 20–44 years (n=375,354 adults).

The underlying cause and date of death were identified for incident deaths that occurred during the 11 years post-survey. All causes of death combined and underlying causes of death for coronary heart disease (CHD) [International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes 410–414], acute ischemic stroke (ICD-9 codes 434 and 436),31 colon cancer (ICD-9 code 153), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; ICD-9 codes 490–496), diabetes (ICD-9 code 250), external causes of injury (accidents, poisoning, suicide, homicide; ICD-9 codes e800–999), and suicide (ICD-9 codes e950–959) were analyzed as separate outcomes. These causes of death were selected because they have been the leading causes of death in younger and middle-aged adults and older adults over the last several decades.32

Data on US state and local (county and municipal) public spending per capita on welfare, education, health, and all categories combined for the 1981 and 1986 fiscal years were derived from the US Bureau of the Census.33,34 Welfare spending encompassed state supplements for unemployment insurance, workers’ compensation, work incentive programs, public assistance programs (e.g., Aid to Families with Dependent Children; the Food Stamp Program), and the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) Program for the aged, blind, and disabled. Education spending consisted primarily of local government spending on elementary and secondary school education and financial aid to college students. Health expenditures reflected spending on Medicaid programs, which provide health care to low-income households.

US state-level income inequality was measured using the Gini coefficient for pre-tax household income based on the 1980 and 1990 US Census.35 The Gini coefficient ranges from theoretical values of 0 (perfect equality) to 1 (perfect inequality).

Model covariates included individual age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, income, education, occupation, urban residence, and employment status. All statistical models also included state-level median household income, % less than high school education, % Black, % urban, % age 65 and older, unemployment rate, and state governor party affiliation.

The instrumental variables applied in the analysis were dichotomous variables indicating the presence of a US state governor (gubernatorial) election in fiscal years 1982 (November 1981) and 1987 (November 1986). These variables were used to isolate random variation in state and local spending in fiscal years 1981 (October 1980–September 1981) and 1986 (October 1985–September 1986), respectively. The fiscal year leading up to a gubernatorial election (compared to preceding years) has been previously linked to lower governmental spending.36 One explanation for this relationship is the political advantage sought by candidates to not be seen by voters as “overspending” during the year prior to an election. Critically, it is implausible that the timing of gubernatorial elections would affect mortality except through changes in spending. In support of the timing of gubernatorial elections as exogenous, the state election indicator variable was uncorrelated with all state-level covariates (all P>0.2).

Statistical Analyses

Linear probability models were used to estimate the impacts of social spending for all major types (welfare, education, health, total) and the effects of income inequality on the probability of dying from major causes, controlling for state- and individual-level covariates. Linear probability models were estimated rather than logit or probit models to avoid the “incidental parameters problem”37,38—a known source of bias in fixed effects estimates from non-linear models. Three sets of models were estimated: 1) ordinary least squares regression (“OLS”); 2) OLS regression with state and time period FE (“OLS + state FE”); and 3) IV analysis with state and time period FE (“IV + state FE”). For IV models, each category of public spending was examined in a separate model. To reduce confounding, OLS models also controlled for spending outside of the spending category of interest.

Because FE regression requires observations from at least two time points, the follow-up period was divided into two time periods (first five years, subsequent six years). Spending in the 1981 fiscal year was examined as a predictor of mortality during the first period (average follow-up of seven years). Spending during the 1986 fiscal year was explored as a predictor of mortality during the second period (average follow-up of eight years), after excluding those who died during the first period. For OLS and IV models with FE, dummy variables were included for each state and time period.

In secondary analyses, models were stratified by age and income. To test alternative pathways for state governor election year effects, state income tax collections per capita and state tax rates were included as covariates in separate models. Furthermore, in sensitivity analyses, the analyses were repeated after excluding those who died during the first two years of follow-up.

To control for sample design and non-response, all models incorporated survey weights and included cross-product interaction terms between survey weights and individual-level covariates to smooth the weights and the resultant model estimates.39,40 Standard errors were adjusted for correlations on mortality within the same state and time period. All expenditures and aggregate income values were converted into 1999 constant dollars.

The state governor election indicator variable was evaluated as an instrumental variable using the Kleibergen-Paap rank LM test to assess its correlation with spending, under the null hypothesis that the gubernatorial election year indicator variable was uncorrelated with state and local spending;41,42 and the Durbin-Wu-Hausman endogeneity test to examine the endogeneity of spending, under the null hypothesis that spending was exogenous.42,43 If evidence to support endogeneity of spending was lacking, OLS estimates were favored over IV estimates for better precision. For each set of results (OLS, OLS + state FE, IV + state FE), preferred estimates are referred to as ‘best estimates’.

All analyses were conducted using Stata Version 9 (Statacorp, TX, US).

RESULTS

Among adults aged 30–74, 55,609 deaths accrued during the follow-up period. Cancers comprised 30% of deaths (16,972 deaths, including 1,577 deaths from colon cancer), followed by CHD (25%; 13,723 deaths); stroke (3%; 1,639 deaths); COPD (5%; 2,705 deaths); and diabetes (2%; 1,304 deaths). Among those aged 20–44, 6,884 deaths from all causes occurred during follow-up. External injuries and suicide contributed 28% (1,961 deaths) and 8% (516 deaths) of deaths, respectively.

Table 1 shows characteristics of the primary sample and states. All individual-level categorical variables were significantly associated with vital status at the end of the 11-year follow-up period. Welfare and education spending were uncorrelated with each other (r = 0.08 and 0.15 in fiscal years 1981 and 1986, respectively). The state governor election indicator variable was correlated with welfare and education spending (rank test P<0.10; Figures 1 and 2) but not healthcare spending. Spending was endogenous in OLS analyses of CHD and all-cause mortality (all endogeneity test P<0.10; Figures 1 and 2).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics Of Primary Study Sample (431,637 Adults Aged 30–74 Years) and State-Level Factors

| % Dead by End of Follow-up Period | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (yrs) | 47.8 (30 – 74) | - |

| Sex | ||

| Women | 53.4% | 10.2%* |

| Men | 46.6 | 16.0 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 90.0% | 12.7%* |

| Black | 8.0 | 16.6 |

| Other | 1.8 | 7.2 |

| Missing | 0.2 | 8.9 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 76.2% | 11.4%* |

| Widowed, Divorced, separated | 17.2 | 19.4 |

| Never married | 6.5 | 12.8 |

| Missing | 0.1 | 12.7 |

| Income | ||

| 0–14,999 | 19.5% | 24.7%* |

| 15–24,999 | 16.2 | 15.8 |

| 25–49,999 | 32.9 | 9.4 |

| 50–74,999 | 20.8 | 6.9 |

| 75,000+ | 7.3 | 6.9 |

| Missing | 3.4 | 14.5 |

| Education | ||

| 0–8 yrs | 14.3% | 26.7%* |

| 9–12 yrs | 52.0 | 12.5 |

| College+ | 33.6 | 7.5 |

| Missing | 0.03 | 14.8 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 59.8% | 6.8%* |

| Absent from work | 3.8 | 9.6 |

| Unemployed | 3.4 | 8.4 |

| Disabled | 1.6 | 48.8 |

| Retired, other | 31.4 | 23.6 |

| Urban residence | ||

| Urban | 66.5% | 13.2%* |

| Rural | 33.5 | 12.3 |

| Missing | 0.01 | 11.5 |

| State-level factors (n = 48 US states) | Period 1 | Period 2 |

| Total public spending ($ US per capita) | 3,207 (2,386 – 5,097) | 3 721 (2,802 – 6,796) |

| Public welfare spending ($ US per capita) | 362 (161 – 722) | 410 (214 – 883) |

| Education spending ($ US per capita) | 1,189 (877 – 1,857) | 1,349 (992 – 2,533) |

| Health spending ($ US per capita) | 271 (126 – 471) | 316 (160 – 721) |

| Gubernatorial election year | 34 states - Yes; 14 states - No | 3 states - Yes; 45 states - No |

| Median household income ($ US) | 35,036 (25,878 – 43,388) | 37,370 (26,270 – 54,431) |

| % <High school education | 66.9 (51.9 – 80.3) | 76.0 (64.3 – 85.1) |

| % Black | 9.4 (0.2 – 35.2) | 9.8 (0.3 – 35.6) |

| % Urban | 66.6 (33.8 – 91.3) | 67.8 (32.1 – 92.6) |

| % Aged 65+ | 11.2 (7.5 – 17.3) | 12.1 (8.0 – 17.7) |

| % Unemployment rate | 7.3 (3.6 – 12.3) | 6.9 (2.8 – 13.1) |

| Gini coefficient | 0.40 (0.37 – 0.44) | 0.43 (0.38 – 0.48) |

| Governor party affiliation | 26 Democrat, 22 Republican | 24 Democrat, 24 Republican |

Mean values with range in parentheses shown for continuous variables. Percentages shown for categorical variables.

All p<0.01 for comparison of categories on vital status at end of follow-up period using Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test.

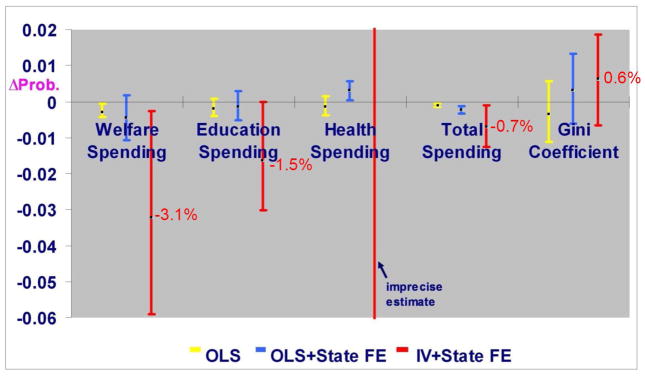

FIGURE 1. Effects of $250 per capita US state and local social spending and 0.1 unit Gini coefficient on individual probability (95% CI) of dying from all causes (431,637 adults aged 30–74 years).

OLS = ordinary least squares analysis; OLS + State FE = ordinary least squares analysis with state and time period fixed effects; IV + State FE = instrumental variable analysis with state and time period fixed effects. All models adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, income, education, occupation, urban residence, and employment status; and state-level median household income, % with less than high school education, % Black, % urban, % aged 65 and older, unemployment rate, state governor party affiliation. All rank test P<0.10 except for healthcare spending (P=0.96). All endogeneity test P<0.10. Robust standard errors clustered by state and time period.

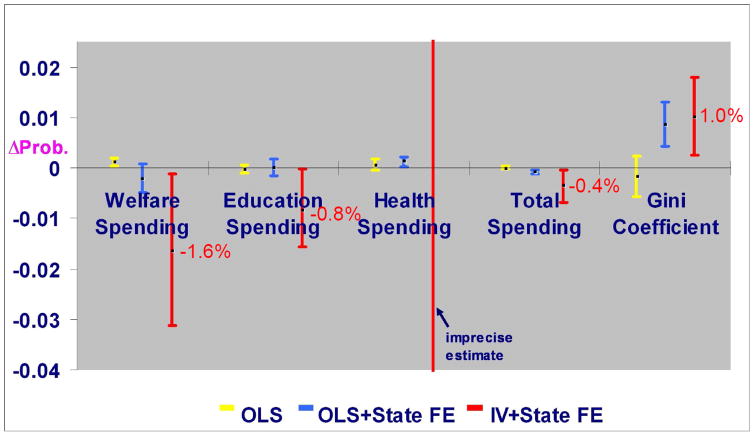

FIGURE 2. Effects of $250 per capita US state and local social spending and 0.1 unit Gini coefficient on individual probability (95% CI) of dying from coronary heart disease (431,637 adults aged 30–74 years).

OLS = ordinary least squares analysis; OLS + State FE = ordinary least squares analysis with state and time period fixed effects; IV + State FE = instrumental variable analysis with state and time period fixed effects. All models adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, income, education, occupation, urban residence, and employment status; and state-level median household income, % with less than high school education, % Black, % urban, % aged 65 and older, unemployment rate, state governor party affiliation. All rank test P<0.10 except for healthcare spending (P=0.96). All endogeneity test P<0.05. Robust standard errors clustered by state and time period.

Using IV analysis, total spending predicted a lower probability of dying from all causes combined (probability change per $250 US spent per capita per year, −0.007, 95% CI −0.013 to −0.001, P=0.02; Figure 1). Welfare and education spending predicted 3.1-percentage point (−0.031, 95% CI −0.059 to −0.0027, P=0.03) and 1.5-percentage point (−0.015, 95% CI −0.030 to −0.0001, P=0.049) reductions in the probability of all-cause mortality, respectively. Healthcare spending was unassociated with all-cause mortality; however, the instrument was poorly correlated with healthcare spending, producing wide confidence intervals (Figure 1). Qualitatively similar associations were found between spending and CHD mortality. Total spending predicted a lower probability of dying from CHD (−0.004, 95% CI −0.007 to −0.0004, P=0.03; Figure 2). Welfare and education spending were associated with a 1.6-percentage point (−0.016, 95% CI −0.031 to −0.0011, P=0.03) and a 0.8-percentage point (−0.008, 95% CI −0.0156 to −0.00024, P=0.04) reductions in the probability of CHD death, respectively (Figure 2).

Figures 1 and 2 show the OLS estimates with and without state and time period FE. Estimates varied in size and direction across models. In OLS models without FE, welfare and total spending were each positively associated with CHD mortality; these associations became inverse in direction once state and time FE were added. For all-cause mortality, both OLS models without FE and IV models produced similar inverse associations for welfare and total spending. Healthcare spending was positively associated with both CHD and all-cause mortality.

Table 2 presents the OLS and IV estimates (controlling for state and time FE) for stroke, colon cancer, COPD, diabetes, external injury, and suicide. For 22 of 24 associations, the ‘best estimates’ were in the hypothesized inverse direction. Evidence suggested impacts of education spending on COPD mortality, welfare and healthcare spending on diabetes mortality, healthcare and total spending on injury mortality, and spending within each category on suicide, although all estimates were at least an order of magnitude smaller than the estimates for CHD mortality. Welfare spending was weakly inversely associated with colon cancer mortality. Healthcare and education spending were positively associated with stroke and diabetes mortality, respectively. For other outcomes, ‘best estimates’ for healthcare spending were derived from OLS models, and suggested inverse associations. For colon cancer and COPD, these estimates were non-significant; for diabetes, external injury, and suicide, estimates were significant but modest in magnitude.

TABLE 2.

Effects of $250 per capita US state and local social spending and 0.1 unit Gini coefficient on individual probabilities (95% CI) of dying from non-CHD major causes

| Stroke | Colon Cancer | COPD | Diabetes | Injury | Suicide | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| IV | OLS | IV | OLS | IV | OLS | IV | OLS | IV | OLS | IV | OLS | |

| Welfare spending | 0.001 (−.003 to 0.005) p=0.54 | −0.0004 (−.001 to .0003) p=0.28 | −0.003 (−.01 to .0001) p=0.06 | −0.001 (−.002 to .0001) p=0.07 | −0.004 (−0.01 to .002) p=0.17 | 0.002 (.001 to .003) p=0.001 | 0.001 (−.003 to .005) p=0.60 | −0.001 (−.002 to −.001) p<0.001 | −0.002 (−.01 to .002) p=0.27 | −0.0003 (−.001 to .001) p=0.64 | −0.001 (−.002 to .001) p=0.41 | −0.001 (−.001 to −.00002) p=0.046 |

| Rank test p | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||||||

| Endogeneity test p | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.79 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Education spending | 0.001 (−.001 to .002) p=0.53 | −0.0002 (−.001 to .0003) p=0.45 | −0.002 (−.004 to .0005) p=0.13 | 0.0005 (−.0001 to .001) p=0.13 | −0.002 (−.005 to .001) p=0.14 | −0.001 (−.001 to −.0001) p=0.03 | 0.0005 (−.001 to .002) p=0.56 | 0.0004 (.0001 to .001) p=0.02 | −0.001 (−.003 to .001) p=0.29 | −0.0003 (−.001 to 0004) p=0.40 | −0.0003 (−.001 to .0004) p=0.38 | −0.0004 (−.001 to −.0002) p=0.001 |

| Rank test p | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | ||||||

| Endogeneity test p | 0.34 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.68 | 0.51 | 0.61 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Healthcare spending | 0.05 (−1.6 to 1.7) p=0.96 | 0.0005 (−.00002 to .001) p=0.06 | −0.13 (−4.7 to 4.4) p=0.96 | −0.0003 (−.001 to .0002) p=0.25 | −0.18 (−6.4 to 6.1) p=0.96 | −0.0001 (−.001 to .0005) p=0.65 | 0.04 (−1.3 to 1.4) p=0.96 | −0.0005 (−.001 to −.0001) p=0.01 | −0.09 (−2.8 to 2.6) p=0.95 | −0.001 (−.001 to −.0001) p=0.02 | −0.02 (−.7 to .6) p=0.95 | −0.0004 (−.001 to −.00004) p=0.03 |

| Rank test p | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.95 | ||||||

| Endogeneity test p | 0.49 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.56 | 0.22 | 0.46 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total spending | 0.0003 (−.001 to .001) p=0.53 | −0.0001 (−.0002 to .0001) p=0.36 | −0.001 (−.002 to .0002) p=0.11 | −0.0002 (−.0004 to .00005) p=0.13 | −0.001 (−.002 to .0003) p=0.14 | −0.0001 (−.0003 to .00004) p=0.13 | 0.0002 (−.0005 to .001) p=0.56 | −0.00003 (−.0002 to .0001) p=0.68 | −0.001 (−.001 to .0004) p=0.26 | −0.0003 (−.0004 to −.0001) p=0.001 | −0.0001 (−.0004 to .0002) p=0.36 | −0.0002 (−.0003 to −.0001) p<0.001 |

| Gini coefficient | 0.0001 (−.001 to .001) p=0.92 | 0.0002 (−.001 to.001) p=0.56 | 0.0002 (−.001, .002) p=0.82 | −0.0001 (−.002 to .001) p=0.83 | 0.001 (−.002 to .003) p=0.58 | 0.0001 (−.002 to .002) p=0.89 | −0.001 (−.002 to.001) p=0.40 | −0.0004 (−.002 to .001) p=0.46 | 0.001 (.0001 to .003) p=0.03 | 0.001 (.00001 to .003) p=0.05 | 0.002 (.001 to .002) p<0.001 | 0.002 (.001 to .002) p<0.001 |

| Rank test p | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | ||||||

| Endogeneity test p | 0.36 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.71 | ||||||

IV = instrumental variable analysis with state and time period fixed effects. OLS = ordinary least squares analysis with state and time period fixed effects. All models adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, income, education, occupation, urban residence, employment status; and state level median household income, % with less than high school education, % Black, % urban, % age 65 and older, unemployment rate, state governor party affiliation. ‘Best’ model estimates based on instrument relevance and endogeneity test statistics for social spending shown in highlighted areas. Robust standard errors clustered by state and time period. Study samples were 431,637 adults age 30–74 years for stroke, colon cancer, COPD and diabetes models; and 375,354 adults age 20–44 years for injury and suicide models.

In total spending models, a 0.1 unit higher Gini coefficient predicted 1, 0.2, and 0.1 percentage point increases in the probabilities of dying from CHD (0.010, 95% CI 0.0026 to 0.0180, P=0.01; Figure 2), suicide (0.002, 95% CI 0.001, 0.002, P<0.001; Table 2), and injury (0.001, 95% CI 0.00001 to 0.003, P=0.05; Table 2), respectively, but did not predict the probability of dying from all causes (0.0061, 95% CI −0.0066 to 0.019, P=0.4; Figure 1) or other causes of death (Table 2).

In IV models stratified by age, the strongest associations were observed among those aged 45–59 (e.g., for welfare spending and all-cause mortality for those aged 45–59: estimated change in probability −0.08, 95% CI −0.15 to −0.003, P=0.04; for those aged 60–74: estimated probability change 0.006, 95% CI −0.07 to 0.09, P=0.9). In income-stratified models, those with annual household incomes <$25,000 US showed stronger associations than those with incomes ≥$25,000 US (e.g., for welfare spending and all-cause mortality for those with incomes <$25,000 US: change −0.05, 95% CI −0.10 to −0.01, P=0.02; for those with incomes ≥$25,000 US: change −0.016, 95% CI −0.04 to 0.01, P=0.3). The Gini coefficient was also more strongly related to CHD mortality among low−income adults, and among adults aged 30–44 and 60+ years (data available on request).

In sensitivity analyses, the addition of state income tax collections per capita or state tax rates to the regression models did not alter the results (data available on request). Likewise, analyses that excluded deaths within the first two years of follow-up yielded comparable findings (e.g., changes in probability of CHD mortality for total spending and per 0.1 higher Gini coefficient, respectively: −0.003, 95% CI −0.005 to −0.0003, P=0.03; and 0.017, 95% CI 0.002 to 0.032, P=0.03).

DISCUSSION

Using data from a large cohort representative of the 48 contiguous US states, this study linked higher state and local public spending on welfare and education to substantially lower chances of dying from heart disease and from any cause. Each additional $250 US per capita spent on welfare and education predicted nearly 2-percentage point and 1-percentage point reductions in the individual probability of dying from heart disease, respectively—on the order of reductions typically achieved through treating a patient with high blood pressure or cholesterol.44,45 Each additional $250 US per capita spent on welfare predicted a 3-percentage point decrease in the probability of dying from any cause. These associations were most salient among middle-aged and low-income adults. More modest associations were found for other major causes of death. Notably, the preferred estimates for healthcare spending were weak and inconsistent across outcomes; however, these estimates were derived from OLS models with state FE and not IV analysis. Controlling for state FE, a 0.1 higher Gini coefficient predicted 1- and 0.2-percentage point higher probabilities of dying from heart disease and suicide, respectively.

Past ecological studies have found similar relations between non-medical social spending and mortality. A cross-country analysis of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) nations examined the associations between country per capita public spending and age-standardized mortality rates.9 A $100 per capita increase in non-medical social spending was associated with a 1-percentage point decrease in all-cause mortality rates, and a 1.2-percentage point decrease in cardiovascular disease mortality rates, controlling for GDP per capita and country FE. Estimated associations with total spending and all-cause mortality in the current study were on the same order of magnitude.

As in the present study, inverse ecological associations have been previously observed between per capita US state welfare and education spending with state-level all-cause mortality rates,10 controlling for state median household income and the Gini coefficient. Another US state-level ecological analysis used state FE along with additional state-level controls, and found inverse associations between education spending and all-cause mortality rates; spending in other categories did not predict mortality.11

The current study determined mixed evidence for healthcare spending effects across outcomes. Healthcare spending appeared to be modestly protective against dying from diabetes, external injuries, and suicide. By contrast, healthcare spending was positively linked to cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality in OLS models; such associations could conceivably be explained by reverse causation.

For income inequality, results from a cross-national ecological study suggested positive relations between country-level income inequality and higher mortality.46 In a meta-analysis of multilevel cohort studies, a 0.05 increase in the Gini coefficient was associated with a modest 1.08 times higher risk of individual mortality.16 A US state-level ecological analysis found that the Gini coefficient was positively associated with all-cause mortality rates.10 Multilevel studies have likewise observed modest positive relations.18,19,47 However, these studies adjusted for confounders to varying degrees, and no studies have yet applied FE or IV analysis to reduce bias.

Previous work by Wilkinson & Pickett48 has shown that preventable causes of death with steeper socioeconomic gradients such as CHD and homicide have more salient associations with income inequality. Significant associations between income inequality with the same or closely related outcomes (deaths from CHD, suicide, and injury) were similarly found, a pattern consistent with income inequality as a “fundamental cause” of mortality disparities.49

This study had several major strengths, including a large cohort design and a population-based sample to strengthen generalizability within the US; linkages to a national mortality database; and analyses of major causes of death in adults. Two statistical tools—fixed effects and instrumental variable analysis—were employed to reduce bias from confounding and reverse causation. Models were further adjusted for multiple individual- and area-level factors to minimize confounding. Subgroup differences in associations were additionally assessed, and suggested the presence of effect modification by age and income.

Some limitations of this study should be noted. First, while FE regression can control for unobserved time-invariant factors, it cannot account for time-varying confounders. Second, IV analysis relies on valid instruments. While empirical evidence supported the validity and exogeneity of the instrument, endogeneity cannot be entirely ruled out. Third, due to the weak correlation of the instrument with healthcare spending, ‘best’ estimates were solely derived from FE models, and may have still been susceptible to bias. Fourth, data on the spending exposures and NLMS cohort corresponded to the 1980s and 1990s, thereby limiting generalizability by time period. Future studies based on data taken from more recent time periods should attempt to replicate these findings. Fifth, the Gini coefficient measure was based on pre-tax household income only, and did not include non-cash government transfers. Nonetheless, state government transfers (e.g., via the Food Stamp Program) would have been captured in the measure of state welfare spending. Finally, the latency period of causal effects of state-level income inequality and social spending on mortality varies by cause of death. While the maximum latency period of 7–8 years in each time period represents a plausible lag period for effects on CHD mortality, it may have fallen short of the true lag periods for selected chronic disease endpoints (e.g., colon cancer). Nonetheless, the inverse association between welfare spending and colon cancer mortality could signify modest short-term benefits of welfare to survival from colon cancer.

The strongest effects of social spending on CHD mortality were for welfare spending, followed by spending on education. Weaker and less consistent effects were suggested for deaths due to diabetes, injury, and suicide. Reductions in the probability of dying with greater welfare spending could be the result of welfare-based increases in income, employment, and other social assistance. The protective effects of education spending against mortality could plausibly be mediated by improvements in the education/health behaviors of family members, friends, or those in close proximity. For example, some evidence suggests that health education in elementary schools can have positive spillover effects on the engagement of children’s parents in physical activity, with these effects appearing to be stronger among parents of lower educational attainment.50

Both state welfare spending and income inequality showed their strongest associations among those of lower income. Such individuals are more likely to be eligible for and thereby to benefit from welfare programs. Furthermore, they may be more sensitive to the effects of income inequality due to the “double burden” of absolute and relative deprivation. Those who were in greatest need may not have access to the best programs and services, which for healthcare has been referred to as the ‘inverse care law’.51

Conclusions

This study identified empirical linkages between higher state-level government spending on welfare and education and lower individual risks of dying, particularly from heart disease and all causes combined. Higher state-level income inequality also predicted higher risks of dying from heart disease and suicide. These findings are in keeping with recent reports by national and international bodies that have highlighted broad social conditions and economic factors as fundamental causes of health, and have called for multisectoral “health in all policies” approaches that extend beyond the traditional health sector.52–54 In this current age of austerity, budgetary constraints, and widening income inequality in the US, further exploration and replication of these findings may best inform such approaches and their associated policies to optimize the public’s health.

HIGHLIGHTS.

State welfare and education spending predicted heart disease and all-cause mortality.

State-level income inequality was also linked to heart disease and suicide mortality.

These associations were more salient among low-income adults.

Acknowledgments

This work was first presented in part as a scientific abstract at the triennial 19th International Epidemiological Association’s (IEA) World Congress of Epidemiology in Edinburgh, Scotland, August 7–11, 2011, for which the author received a Young Investigator Award. This paper uses data obtained from the de-identified public use file of the US National Longitudinal Mortality Study (NLMS). The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NLMS, Bureau of the Census, or the project sponsors of the NLMS: the US National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Cancer Institute, National Institute on Aging, and National Center for Health Statistics.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval: Institutional review board approval was not required, as the study did not involve human participant interactions and all data were publicly available and de-identified.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Johnson N, Oliff P, Williams E. An update on state budget cuts: at least 46 states have imposed cuts that hurt vulnerable residents and cause job loss. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNichol E, Hall D, Cooper D, et al. A state-by-state analysis of income trends. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeBacker J, Heim B, Panousi V, et al. Rising inequality: transitory or permanent?. New evidence from a panel of U.S. tax returns (final conference draft presented at the 2013 Brookings Panel on Economic Activity; March 21–22, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adema W, Ladaique M. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 92. Paris, France: OECD Publishing; 2009. How expensive is the welfare state?: Gross and net indicators in the OECD Social Expenditure Database (SOCX) http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Projects/BPEA/Spring%202013/2013a_panousi.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lurie N. What the federal government can do about the non-medical determinants of health. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2002;21(2):94–106. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilensky GR, Satcher D. Don’t forget about the social determinants of health. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2009;28(2):w194–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.w194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stuckler D, Basu S, McKee M. Budget crises, health, and social welfare programmes. BMJ. 2010;340:c3311. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunn JR, Burgess B, Ross NA. Income distribution, public services expenditures, and all cause mortality in US States. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:768–74. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.030361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim AS, Jennings ET., Jr Effects of US states’ social welfare systems on population health. Policy Studies J. 2009;37:745–767. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lynch J, Smith GD, Harper S, et al. Is income inequality a determinant of population health? Part I. A systematic review. Milbank Quarterly. 2004;82:5, e99. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00302.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawachi I. Income inequality and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, editors. Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 76–94. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilkinson RG. Socioeconomic determinants of health. Health inequalities: relative or absolute material standards? BMJ. 1997;314(7080):591–595. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7080.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim D, Kawachi I, Hoorn SV, et al. Is inequality at the heart of it? Cross-country associations of income inequality with cardiovascular diseases and risk factors. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:1719–32. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kondo N, Sembajwe G, Kawachi I, et al. Income inequality, mortality, and self rated health: meta-analysis of multilevel studies. BMJ. 2009;339:b4471. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE. Income inequality and population health: A review and explanation of the evidence. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(7):1768–1784. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Backlund E, Rowe G, Lynch J, et al. Income inequality and mortality: a multilevel prospective study of 521 248 individuals in 50 US states. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:590–6. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lochner K, Pamuk E, Makuc D, Kennedy BP, Kawachi I. State level income inequality and individual mortality risk: a prospective, multilevel study. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:385–91. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.3.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dahl E, Ivar Elstad J, Hofoss D, Martin-Mollard M. For whom is income inequality most harmful? A multi-level analysis of income inequality and mortality in Norway. Soc Sci Med. 2006 Nov;63:2562–74. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subramanian SV, Kawachi I. Whose health is affected by income inequality? A multilevel interaction analysis of contemporaneous and lagged effects of state income inequality on individual self-rated health in the United States. Health Place. 2006 Jun;12(2):141–56. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wooldridge J. Introductory econometrics: A modern approach. Mason, TX: South-Western College Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davey Smith G, Sterne JAC, Fraser A, et al. The association between BMI and mortality using offspring BMI as an indicator of own BMI: large intergenerational mortality study. BMJ. 2009;339:b5043. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fish JS, Ettner S, Ang A, et al. Association of perceived neighborhood safety on body mass index. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:2296–2303. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.183293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim D, Baum CF, Ganz ML, et al. The contextual effects of social capital on health: a cross-national instrumental variable analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:1689–97. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mojtabai R, Crum RM. Cigarette smoking and onset of mood and anxiety disorders. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1656–1665. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hawkins SS, Baum C. Impact of state cigarette taxes on disparities in maternal smoking during pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(8):1464–1470. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Makuc D, McMillen M, Feinleib M, et al. Proceedings of the Section on Social Statistics. American Statistical Association; 1984. An overview of the U.S. National Longitudinal Mortality Study. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curb JD, Ford CE, Pressel S, et al. Ascertainment of vital status through the National Death Index and the Social Security Administration. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121:754–66. doi: 10.1093/aje/121.5.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldstein LB. Accuracy of ICD-9-CM coding for the identification of patients with acute ischemic stroke: effect of modifier codes. Stroke. 1998;29:1602–1604. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.8.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2010: With Special Feature on Death and Dying. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.US Bureau of the Census. Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1984. Washington, DC: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 34.US Bureau of the Census. Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1989. Washington, DC: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.US Bureau of the Census. Table S4: Gini ratios by state 1969. 1979;1989:1999. Available at: http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/data/historical/state/state4.html. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poterba JM. State response on fiscal crises: the effects of budgetary institutions on policies. J Political Economy. 1994;102:799–821. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lancaster T. The incidental parameter problem since 1948. J Econometr. 2000;95:391–413. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heckman JJ. The incidental parameters problem and the problem of initial conditions in estimating a discrete time discrete data stochastic process. In: Manski C, McFadden D, editors. Structural Analysis of Discrete Data with Econometric Applications. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elliott MR. Bayesian weight trimming for generalized linear regression models. Survey Methodology. 2007;33:23–34. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gelman A. Struggles with survey weighting and regression modeling. Stat Science. 2007;22:153–164. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kleibergen F, Paap R. Generalised reduced rank tests using the singular value decomposition. J Econometr. 2006;133:97–126. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baum CF, Schaffer ME, Stillman S. Enhanced routines for instrumental variables/GMM estimation and testing. Stata Journal. 2007;7:465–506. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hayashi F. Econometrics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wright JM, Musini VM. First-line drugs for hypertension. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009:3. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001841.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators. Mihaylova B, Emberson J, Blackwell L, et al. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomized trials. Lancet. 2012;380(9841):581–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60367-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elgar FJ. Income inequality, trust, and population health in 33 countries. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:2311–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.189134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deaton A, Lubotsky D. Mortality, inequality and race in American cities and states. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:1139–53. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE. Income inequality and socioeconomic gradients in mortality. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(4):699–704. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.109637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Phelan JC, Link BG, Diez-Roux A, Kawachi I, Levin B. “Fundamental causes” of social inequalities in mortality: a test of the theory. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;45(3):265–85. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berniell L, de la Mata D, Valdes N. Spillovers of health education at school on parents’ physical activity. Health Econ. 2013;22(9):1004–20. doi: 10.1002/hec.2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hart JT. The inverse care law. Lancet. 1971;1:405–12. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)92410-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England Post 2010. Fair society, healthy lives. The Marmot Review. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marmot M, Allen J, Bell R, et al. Consortium for the European Review of Social Determinants of Health and the Health Divide. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet. 2012;380(9846):1011–29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Commission to Build a Healthier America. Beyond health care: new directions to a healthier America. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2009. [Google Scholar]