Abstract

This study tested a longitudinal model of religious social support as a potential mediator of the relationship between religious beliefs and behaviors, and multiple health-related outcomes (e.g., depressive symptoms, functioning, diet, alcohol use, cancer screening). A national probability sample of African Americans enrolled in the RHIAA (Religion and Health In African Americans) study completed three waves of telephone interviews over a 5-year period (N=766). Longitudinal structural equation models indicated that religious behaviors, but not beliefs, predicted a slowing of a modest overall decline in positive religious social support, while negative interactions with congregational members were stable. Positive religious support was associated with lower depressive symptoms and heavy drinking over time, while negative interaction predicted increases in depressive symptoms and decreases in emotional functioning. Positive religious support mediated the relationship between religious behaviors and depressive symptoms and heavy drinking. Findings have implications for mental health interventions in faith-based settings.

Keywords: Longitudinal, religion, African American, religious social support, depression, health behaviors

Introduction

Many previous studies have examined associations between religious involvement and various health-related outcomes (Ellison & Hummer, 2010; Koenig, King, & Carson, 2012; Koenig, McCullough, & Larson, 2001). Studies have largely, but not always, reported a positive association between religious involvement and health. We define religious involvement as engagement in “an organized system of [religious] beliefs, practices, rituals, and symbols” (Thoresen, 1998)” Recognizing that religious involvement is a multidimensional construct and experience (Hill & Hood, 1999) we employ a two-dimensional model to characterize religious involvement, comprised of religious beliefs (e.g., close personal relationship with higher power/God) and religious behaviors (e.g., religious service attendance) (Lukwago, Kreuter, Bucholtz, Holt, & Clark, 2001; Roth et al., 2012).

After a fairly consistent pattern in the literature, studies on the “religion-health connection” naturally evolved from identifying if there was a relationship to examining potential explanatory mechanisms of (or reasons for) that relationship. Identifying mechanisms that might account for the religion-health connection constitutes much of the theory that has been applied in this area (see Holt, Schulz, & Wynn, 2009 for a discussion). Possible explanatory mechanisms of the religion-health connection include but are not limited to ideas that religious involvement impacts health outcomes through: fostering good mental health (Ellison & Levin, 1998; Levin & Vanderpool, 1989; Oman & Thoresen, 2002); beliefs that one should live healthy or avoid health risk behaviors in accord with religious doctrine (Chatters, 2000; Ellison & Levin, 1998; George, Larson, Koenig, & McCullough, 2000; Levin & Vanderpool, 1989; Musick, Traphagan, Koenig, & Larson, 2000; Oman & Thoresen, 2002); and opportunities for greater social support (Chatters, 2000; Ellison & Levin, 1998; George et al., 2000; Levin & Vanderpool, 1989; Musick et al., 2000; Oman & Thoresen, 2002).

Religious social support

Religious social support, sometimes referred to as church-based social support, is a type of social support in which participation in religious activities provides people with access to social networks that include support from clergy and from other members of that religious organization (Kanu, Baker, & Brownson, 2008). The benefits received from these religious networks may be unique from support received from more secular networks (Debnam, Holt, Clark, Roth, & Southward, 2012; Krause, 2002). Theory indicates that social support is a multidimensional construct having to do with the function of the support provided (Cohen, 2009). The present study utilizes a multidimensional model of religious social support that includes several aspects: emotional support provided, emotional support received, anticipated tangible support (these three aspects combined are hereafter called “positive religious support”), and negative interactions with one's fellow church members (Krause, Ellison, Shaw, Marcum, & Boardman, 2001). Though general social support has been included in several theoretical models of the religion-health connection, the role of religious social support is potentially highly important yet it has been less often examined.

Studies have reported on the role of religious social support in a variety of populations and health-related outcomes. Religious social support was found to be associated with better recovery from serious mental illness in a patient sample (Webb, Charbonneau, McCann, & Gayle, 2011). In a national sample of Presbyterian adults, it was found that congregational support (e.g., health-related support from one's congregation) played a role in participants' engagement in preventive health services (Benjamins, Ellison, Krause, & Marcum, 2011). In a study of older African Americans, social support from church members (e.g., religious social support) was significantly associated with lower depressive symptoms and psychological distress (Chatters, Taylor, Woodward, & Nicklett, 2015). The negative interaction dimension of religious social support was associated with more depressive symptoms and psychological distress. Religious social support was not associated with participants' general health perception in a sample including those with cancer, spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, stroke, or healthy individuals (Campbell, Yoon, & Johnstone, 2010).

Several studies have reported a unique role of religious support in health studies, beyond the contributions of general social support. In a study of family members of individuals having cardiac bypass surgery, use of religious sources of support was associated with psychosocial adjustment after controlling for nonreligious support (VandeCreek, Pargament, Belavich, Cowell, & Friedel, 1999). Using the wave 1 the present study data, Debnam and colleagues (2012) identified the unique role of religious social support by reporting the relative contributions of these constructs to a variety of health behaviors. Multiple dimensions of religious social support predicted fruit and vegetable consumption, moderate physical activity, and lower alcohol use, above and beyond general social support. With religious social support conceptualized as support from God, congregation, or religious leaders, only congregational support predicted self-reported health status while controlling for non-religious social support, among British Christians (Brewer, Robinson, Sumra, Tatsi, & Gire, 2015).

Far fewer studies have specifically considered religious social support as a mediator of the religion-health connection. Religious social support was found to mediate the relationship between religious behaviors and depressive symptoms and emotional functioning, but not physical functioning, in a cross-sectional analysis of wave 1 of the present study (Holt, Wang, Clark, Williams, & Schulz, 2013). In a study of individuals caring for those with Alzheimer's disease and non-caregiving controls, those in the caregiving role reported lower well-being, quality of life, and religious social support than controls (Burgener, 1999). In a sample of Caucasian and African American older adults studied over a 4-year period, those with greater disability reported receiving more tangible support from their congregations, and higher tangible support was associated with a slower increase in disease trajectory (Hayward & Krause, 2013).

The present study

The present study examined the mediational role of religious social support in longitudinal relationships between religious involvement and a variety of health-related outcomes in a national sample of African Americans. We know of few longitudinal studies that have examined whether religious social support mediates the role of religious involvement in physical- or mental health-related outcomes. Though the few cross-sectional mediation models are informative, these designs have limitations involving temporal and cause-and-effect interpretations. In addition, cross-sectional analyses can yield biased estimates of underlying longitudinal mediation mechanisms (Maxwell & Cole, 2007). The current study used a prospective design, with the ability to assess and control for known confounders in religion-health research (Powell, Shahabi, & Thoresen, 2003) and baseline values, thus allowing the examination of change over time.

The study focused on African Americans because this group as a whole is on average highly religiously involved (Taylor, Chatters, & Levin, 2003) and carries a disproportionate burden of most chronic diseases and poor health outcomes (Williams, 2012). The special emphasis on this population has implications for better understanding these health disparities and has the potential to inform public health interventions to eliminate them. We employed a 3-wave longitudinal design over a 5-year period in order to try and rule out the possibility of reverse causality, in which healthier people are either more attracted to religious participation and/or are physically able to attend worship services (Maselko, Hayward, Hanlon, Buka, & Meador, 2012; Roth, Usher, Clark, & Holt, 2016).

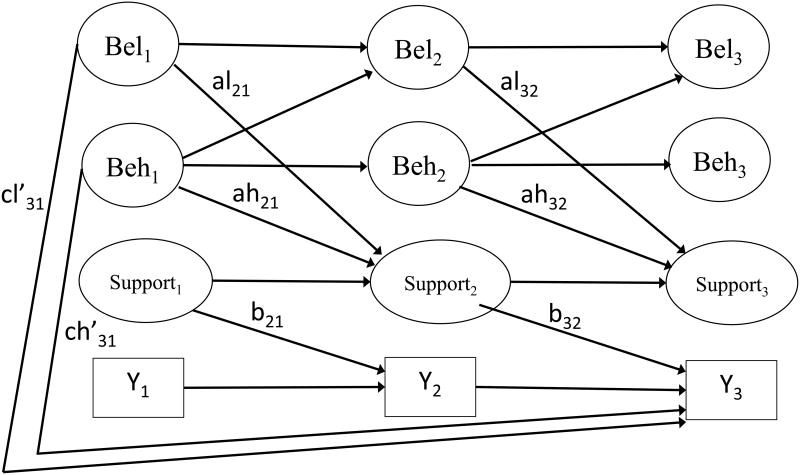

Guided by theory and research in religious social support (Pargament, Feuille, & Burdzy, 2011) and our previous cross-sectional research examining religious social support as a mediator of the religion-health connection, we put forth several hypotheses based on the conceptual model shown in Figure 1. First, we hypothesized that both religious beliefs and religious behaviors would predict changes in religious social support over time (the “al” and “ah” paths in Figure 1). Second, consistent with the theoretical model of religious social support that includes both positive (emotional support provided/received; anticipated tangible support) and negative (negative interaction) aspects (Krause et al., 2001), we anticipated that the positive aspects of religious support would be associated with increases in adaptive health behaviors and reductions in health risk behaviors over time, and that the opposite would be true for the negative interaction dimension (the b32 paths in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Longitudinal model of religious social support as a mediator of the religious involvement -- health connection.

Third, based on our previous cross-sectional research (Holt, Clark, Debnam, & Roth, 2014) and that religious social support is provided by people in one's faith-based social network, we hypothesized that religious behaviors would play a stronger role in the longitudinal religion-health behavior model than private religious beliefs. Fourth, we anticipated that both positive and negatively-valenced dimensions of religious social support would at least in part mediate the relationship between religious involvement and change in a number of the health behavior indicators over time. Given the direct effect of religious beliefs/behaviors and health-related outcomes has been reported previously (Holt, Roth, Huang, Park, & Clark, 2017) (“cl' ” and “ch' ” in Figure 1) we did not include additional hypotheses for these relationships.

Method

RHIAA Study

The “Religion and Health in African Americans” (RHIAA) study was designed specifically to examine religion-health associations and mediators among a national probability-based sample of healthy African American adults (not targeting a particular medical condition). Though the RHIAA study was not originally designed as a longitudinal study, later when additional support became available, the study team attempted to re-contact those participants who completed the initial telephone interview (wave 1). Participants completed the waves 2 and 3 follow-up interviews at 2.5 and 5.0 years after wave 1, respectively (Holt et al., 2015). An external subcontractor (OpinionAmerica) developed the study sample and conducted all data collection activities (discussed in more detail elsewhere (Holt et al., 2015). Participant eligibility criteria included the ability to speak English, self-identification as African American, and being at least age 21 at wave 1. Individuals with a previous cancer diagnosis were excluded because the telephone interview included cancer screening questions that would not be applicable to those who had cancer. Verbal assent was documented following the interviewers reading the informed consent script to participants, who were mailed a $25 gift card for completing each interview.

Measures

Religious involvement

We assess religious involvement through a 9-item instrument that assesses two dimensions: religious beliefs (e.g., “I feel the presence of God in my life.”; “I have a close personal relationship with God.”; Cronbach's α = .92 in present sample) and religious behaviors (e.g., church service attendance, involvement in other church activities; talking openly about faith with others; Cronbach's α = .74 in present sample) (Lukwago et al., 2001; Roth et al., 2012). While most of the items employed a 5-point Likert-type format, the two service attendance items used a 3-point format. Subscale scores can range from 4-20 for religious beliefs and 5-21 for behaviors, with higher scores reflecting greater religious involvement.

Religious social support

Religious social support was assessed using a scale from the Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality for use in Health Research (Fetzer Institute: National Institute on Aging Working Group, 1999). This brief version 8-item instrument includes 2 items for each of the four subscales (described previously; sample items: “How often do people in your congregation make you feel loved and cared for?”; “If you were ill, how much would the people in your congregation be willing to help out?”; How often do people in your congregation put too many demands on you?). Based on previous research (Krause et al., 2001), because 2 items are typically not sufficient for extracting latent factors in structural equation modeling (Kline, 2005), and for model parsimony, we combined the three positive aspects of religious social support into a single latent factor or “positive religious support” with 6 indicator items. This 2-dimensional measurement model (positive religious support; negative interaction) performed well in previous work (Holt et al., 2013). Internal reliability of the scale overall was α=0.76 in the present sample, (α=0.84 for positive religious support [emotional support provided/received, anticipated tangible support]; α=0.60 for negative interaction). Items comprising each scale were assessed using a 4-point Likert-type scale and can be summed to result in a possible range 6 to 24 for positive religious support and 2 to 8 for negative interaction, with higher scores indicating greater levels of the construct.

Health behaviors

An adapted National Cancer Institute's 5-A-Day Survey was used to evaluate fruit and vegetable consumption (Block et al., 1986; Kreuter et al., 2005). Seven items assess fruit consumption and 5 items target vegetables, totaling 15 fruits and 18 vegetables assessed specifically within these items. The response scale ranges from 0 to 8 or more weekly servings, with servings per day computed by summing and dividing by 7.

Alcohol and tobacco use were assessed using Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) modules. Adequate test-retest reliability was evidenced in a previous sample of African Americans (Stein, Lederman, & Shea, 1993). The alcohol consumption module began by asking whether participants had any alcohol use in the previous 30 days. For those answering “yes,” items followed that assessed binge and heavy drinking (“Considering all types of alcoholic beverages, how many times during the past 30 days did you have 4/5 or more drinks on an occasion? [4 for women; 5 for men]”; “During the past 30 days, what is the largest number of drinks you had on any occasion?”). The tobacco use items asked whether participants smoked cigarettes every day, some days, or not at all. The brief version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) (Craig et al., 2003) was used to assess physical activity. Items evaluate the number of days in the previous week and amount of time participants spent on activities including vigorous and moderate activity and walking. Minutes per week are reported.

Cancer screening behaviors

Participants reported on select age-and sex-appropriate cancer screening behaviors using items based on the BRFSS. Screenings included mammography for women, prostate specific antigen testing for men, and colonoscopy for all age-eligible participants. Because recall of screening tests can be difficult and often results in over-reporting and telescoping (McPhee et al., 2002; Rauscher, Johnson, Cho, & Walk, 2008), participants indicated whether they had ever had the screening. A ceiling effect resulted in mammography being analyzed as past two years vs. more than two years ago (including never).

Depressive symptoms

The Centers for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) was used to assess depressive symptoms (Radloff, 1977). Previously validated with an African American population (Makambi, Williams, Taylor, Rosenberg, & Adams-Campbell, 2009; Roth, Ackerman, Okonkwo, & Burgio, 2008), participants indicate the frequency in the past week that they experienced symptoms such as ‘I had crying spells’ and ‘I felt that everything I did was an effort’ (rarely/less than one day . . . all of the time/5–7 days). Test–retest reliability and internal consistency were strong in previous normal and patient populations, including in the present sample (α=0.89).

Physical and emotional functioning

The Medical Outcomes Survey Short Form SF-12 is widely used to assess physical (e.g. ‘Does your health now limit you in these activities? If so, how much?: Moderate activities such as moving a table, pushing a vacuum cleaner, bowling or playing golf’) and emotional (e.g. [how often during past four weeks] ‘Have you felt calm and peaceful?; Did you have a lot of energy?’) functioning (Ware, Kosinski, & Keller, 1996). This 12-item form has evidenced reliability and validity similar to the longer versions, and acceptable test–retest reliability for the physical (0.89) and emotional (0.76) subscales (Ware et al., 1996).

Demographics

Participant sex, date of birth, marital status, years of education, employment, and self-rated health status were assessed. These variables were based on recommendations about potential confounding factors in religion-and-health research (Powell et al., 2003).

Statistical analyses

All analyses reported here were conducted using structural equation modeling (SEM) procedures as conducted by Mplus version 7.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 2013). These models are discussed in greater detail in our previous work (Holt et al., 2017). Measurement models were conducted first and were followed by the structural models. After satisfactory fit was obtained for the measurement models, structural models were then estimated that included both the mediated effects and unmediated or direct effects of religious involvement at wave 1 on health behaviors at wave 3 as illustrated in Figure 1. Predictive effects on a variable at wave t are actually predicting a change on that variable from wave t-1 to wave t.

The mediation paths in Figure 1 extend on the classic a, b, and c' paths from the mediation literature (MacKinnon, 2008; Maxwell & Cole, 2007; Roth & MacKinnon, 2012). In our notation of the predictive paths in the mediation models, we use subscripts to denote measurement waves, and “l” and “h” to denote paths from religious beliefs and religious behaviors, respectively. Path ch'31, for example, depicts the unmediated or direct effect of religious behaviors at wave 1 on the health outcome at wave 3. Because this was an observational study with no interventions and a fairly consistent inter-wave interval of approximately 2.5 years, additional parsimony was achieved by restricting the analysis to 766 African American participants who provided data at all 3 waves, and constraining the wave 1 → wave 2 paths to be equal to the wave 2 → wave 3 paths for the same variables as long as those effects were also adjusted for the same covariates at each wave. Additional paths from religious behaviors at time t to religious beliefs at the subsequent data collection wave were included in the model based on findings from an earlier two-wave analysis (Roth et al., 2016).

All variables in Figure 1 were further adjusted for age, sex, years of education, and self-rated health assessed at wave 1. The maximum likelihood estimation method was used for all model estimates. The mediation effects (al21*b32 for religious beliefs, ah21*b32 for religious behaviors) were tested for statistical significance using Sobel's delta method (Sobel, 1982). An RMSEA less than 0.06 was considered as indicative of excellent model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

RHIAA sample

The RHIAA study is comprised of two sub-samples of participants who completed a telephone interview using the same protocol except that subsample 1 (N=2,370) also reported on lifestyle behaviors while subsample 2 (N=803) also reported on physical/emotional functioning. Both subsamples reported on depressive symptoms. A total of 3,173 participants completed wave 1. Wave 1 response rates were 19% and 27% (respectively), calculated as #accepted / [#accepted + # non-interviewed] (Holt et al., 2014; Holt et al., 2013). Upper bound response rates included only those individuals who were eligible upon screening but then refused, and were 94% and 98% (Holt et al., 2014; Holt et al., 2013). Retention rates from Waves 1 to 3 were 24% overall largely because the RHIAA study was not originally designed for longitudinal data collection (Holt et al., 2015). Analyses of participant retention found that the retained participants were slightly but significantly older, more educated, more likely to be female, and less likely to report “poor” self-rated health than those not retained (Holt et al., 2015). The current analytic sample includes individuals who provided data at all three waves (N=766; see Table 1 for participant characteristics). Table 2 displays the distributions for all study variables.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics for all participants who were interviewed for all 3 waves.

| Variable | All participants (n=766) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 58.72 ± 12.06 |

|

| |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 491 (64.10) |

| Male | 275 (35.90) |

|

| |

| Education, n (%) | |

| ≥College | 455 (59.55) |

| <College | 309 (40.45) |

|

| |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Never been married | 76 (9.95) |

| Currently single | 136 (17.80) |

| Separated or divorced | 138 (18.06) |

| Widowed | 123 (16.10) |

| Currently married or living with partner | 291 (38.09) |

|

| |

| Employment, n (%) | |

| Full-time employed | 252 (33.07) |

| Part-time employed | 89 (11.68) |

| Not currently employed | 83 (10.89) |

| Retired | 250 (32.81) |

| Receiving disability | 88 (11.55) |

|

| |

| Health status, n (%) | |

| Poor | 36 (4.70) |

| Fair | 167 (21.80) |

| Good | 265 (34.60) |

| Very good | 201 (26.24) |

| Excellent | 97 (12.66) |

|

| |

| Income, n (%) | |

| ≤$30,000 | 308 (47.09) |

| >$30,000 | 346 (52.91) |

Note: Also reported in Holt, Roth, Huang, Park, & Clark, (2017).

Table 2. Descriptives of study outcomes at the three study waves.

| Variable | N | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religious beliefs (/20 max) | 756 | 17.74 (2.91) | 17.83 (2.77) | 17.81 (2.82) |

| Religious behaviors (/21 max) | 742 | 16.24 (3.42) | 16.51 (3.39) | 16.40 (3.38) |

| Religious social support - positive (/24 max) | 635 | 19.33 (3.96) | 18.90 (4.32) | 18.83 (4.53) |

| Religious social support - negative (/8 max) | 651 | 3.34 (1.39) | 3.30 (1.30) | 3.34 (1.43) |

| Depressive symptoms (/60 max) | 737 | 9.98 (9.25) | 10.55 (9.08) | 10.68 (9.04) |

| SF-12 physical (/100 max) | 196 | 45.01 (11.31) | 43.66 (11.25) | 43.58 (11.53) |

| SF-12 mental (/100 max) | 196 | 53.68 (8.06) | 52.62 (9.77) | 52.10 (9.72) |

| Fruit servings per day (/8 max) | 564 | 2.62 (1.34) | 2.38 (1.21) | 2.38 (1.21) |

| Vegetable servings per day (/5.71 max) | 564 | 2.21 (0.94) | 2.12 (0.94) | 1.98 (0.88) |

| Drinking alcohol Y/N in the past 30 days (%) | 563 | 0.40 (0.49) | 0.40 (0.49) | 0.39 (0.49) |

| 4/5 or more alcohol drinks (%) | 509 | 0.51 (2.28) | 0.37 (1.96) | 0.52 (2.73) |

| Largest number of drinks∧ | 520 | 1.01 (1.94) | 0.92 (1.79) | 0.93 (2.07) |

| Currently smoking (%) | 562 | 0.17 (0.38) | 0.16 (0.37) | 0.15 (0.36) |

| Vigorous activities minutes / week | 536 | 170.07 (268.43) | 162.29 (234.51) | 138.59 (226.48) |

| Moderate activities minutes / week | 523 | 148.41 (249.87) | 131.59 (206.18) | 133.15 (219.34) |

| Walking minutes / week | 527 | 232.24 (294.37) | 217.78 (280.85) | 176.72 (249.50) |

| Ever had a mammogram (%) | 348 | 0.95 (0.21) | 0.95 (0.22) | 0.97 (0.17) |

| Last mammogram: past 2 years vs. > 2 years or never (%) | 348 | 0.90 (0.30) | 0.88 (0.33) | 0.89 (0.31) |

| Ever had a PSA test (%) | 157 | 0.78 (0.42) | 0.87 (0.34) | 0.89 (0.32) |

| Ever had a colonoscopy (%) | 382 | 0.74 (0.44) | 0.82 (0.38) | 0.87 (0.34) |

NOTE: Sample sizes, means, standard deviations, and percentages are reported.

Means reflect the majority of participants who reported 0 drinks in the past 30 days for whom a value of 0 was entered.

Results

Measurement model

The measurement model included the aforementioned 2-factor religious involvement model based on wave 1 data (Roth et al., 2012), which we expanded by adding waves 2 and 3 and by adding all 3 waves of religious social support items. For the model that included religious beliefs, religious behaviors, and positive religious support, good fit to the observed data was found (χ2 = 3541.38, df = 1050, RMSEA = .056). Excellent fit was found for the model that included religious beliefs, religious behaviors, and negative interaction (χ2 = 1216.16, df = 556, RMSEA = .039). All observed indicators had reasonable and highly significant standardized factor loadings greater than 0.40 on their latent factors.

Structural mediation models

Mediation effects for positive religious support

This section involves the following paths in Figure 1 and in Tables 2 and 3: al; ah; b32; al*b32, ah*b32. Examination of the subscale means in religious social support at the three waves shown in Table 2 suggests a slight decrease in positive religious support over time. The mediation model findings for the latent variable structural models for positive religious support are shown in Table 3. Overall model fit was good, with RMSEA values at or below .06 for all models. The al paths, representing the effect of religious beliefs to change in positive religious support at the following wave, were largely non-significant, suggesting that religious beliefs were not associated with changes in positive religious support over time. The ah paths were mostly significant, indicating that higher religious behaviors at wave 1 prevented the otherwise slight overall decrease in positive religious support observed in the sample over time (ps < .001).

Table 3. Adjusted mediation model using positive religious social support as mediator.

| Outcome | al | ah | b32 | Indirect effect | cl' | ch' | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| al*b32 | ah*b32 | |||||||

| Depressive symptoms1 | -0.037 | 0.290*** | -0.123** | 0.005 | -0.036* | 0.014 | 0.043 | 0.046 |

| SF-12 physical function1 | -0.044 | 0.043 | 0.011 | 0.000 | 0.000 | -0.027 | -0.002 | 0.059 |

| SF-12 emotional function1 | -0.051 | 0.057 | 0.074 | -0.004 | 0.004 | 0.150 | -0.088 | 0.060 |

| Fruit servings per day1 | -0.081 | 0.423*** | -0.054 | 0.004 | -0.023 | -0.198** | 0.266** | 0.047 |

| Vegetable servings per day1 | -0.082 | 0.420*** | -0.126* | 0.010 | -0.053 | -0.161* | 0.209* | 0.048 |

| Drinking alcohol Y/N in the past 30 days1 | -0.097* | 0.447*** | 0.092 | -0.009 | 0.041 | 0.150* | -0.237** | 0.047 |

| 4/5 or more alcohol drinks1 | -0.083 | 0.432*** | -0.181** | 0.015 | -0.078* | -0.181** | 0.254* | 0.047 |

| Largest number of drinks1 | -0.078 | 0.420*** | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.070 | -0.064 | 0.047 |

| Currently smoking1 | -0.078 | 0.418*** | 0.012 | -0.001 | 0.005 | 0.040 | -0.049 | 0.047 |

| Vigorous activities minutes / week1 | -0.079 | 0.415*** | 0.039 | -0.003 | 0.016 | 0.041 | -0.035 | 0.047 |

| Moderate activities minutes / week1 | -0.076 | 0.412*** | -0.013 | 0.001 | -0.005 | -0.039 | 0.025 | 0.046 |

| Walking minutes / week1 | -0.077 | 0.413*** | 0.042 | -0.003 | 0.017 | 0.027 | -0.105 | 0.046 |

| Last mammogram (within last 2 years vs. > 2 years or never)2 | -0.108 | 0.390*** | 0.079 | -0.009 | 0.031 | 0.084 | -0.050 | 0.053 |

| Ever had a PSA test2 | -0.099 | 0.538*** | -0.148 | 0.015 | -0.079 | -0.183 | 0.471* | 0.053 |

| Ever had a colonoscopy1 | -0.079 | 0.420*** | 0.075 | -0.006 | 0.032 | 0.042 | -0.134 | 0.047 |

Note.

Age, gender, education and self-rated health were adjusted.

Age, education and self-rated health were adjusted.

The b32 paths, representing the effect of positive religious support at wave 2 on the change in the outcome from wave 2 to wave 3, were only significant for depressive symptoms (p = .005), vegetable servings per day (p = .035), and number of days where 4/5 or more alcoholic drinks were consumed (p = .003). All of these effects were in the negative direction, for example indicating that positive religious support was associated with less increase in depressive symptoms over time. While the al*b32 mediation effects were non-significant, the ah*b32 mediation effects were significant for depressive symptoms (p = .012) and number of days where 4/5 or more alcoholic drinks were consumed (p = .013). This indicates that positive religious support mediates the relationship between religious behaviors and these two outcomes.

Mediation effects for negative interaction subscale

This section involves the following paths in Figure 1 and in Tables 2 and 4: al; ah; b32; al*b32, ah*b32. Examination of the means at the three waves shown in Table 2 shows stability in negative interaction over time. The mediation model findings for the latent variable structural models for negative interaction are shown in Table 4. Overall model fit was good, with RMSEA values below .06 for all models and at or below .04 for most. The al paths, representing the effect of religious beliefs on change in negative interaction at the following wave, were largely non-significant, suggesting that religious beliefs were not associated with a change in negative interaction over time. However, the ah paths were mostly significant, suggesting that while negative interaction means did not change over time, there was individual level change where those higher in religious behaviors had increases while those low in religious behaviors had decreases (ps < .01).

Table 4. Adjusted mediation model using negative interaction as mediator.

| Outcome | al | ah | b32 | Indirect effect | cl' | ch' | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| al*b32 | ah*b32 | |||||||

| Depressive symptoms1 | -0.058 | 0.194** | 0.113* | -0.007 | 0.022 | 0.034 | -0.082 | 0.039 |

| SF-12 physical function1 | -0.295 | 0.235 | -0.067 | 0.020 | -0.016 | -0.047 | 0.050 | 0.056 |

| SF-12 emotional function1 | -0.291* | 0.260* | -0.218* | 0.063 | -0.057 | 0.145 | -0.034 | 0.055 |

| Fruit servings per day1 | -0.059 | 0.219** | 0.016 | -0.001 | 0.004 | -0.180** | 0.208** | 0.039 |

| Vegetable servings per day1 | -0.045 | 0.202** | -0.003 | 0.000 | -0.001 | -0.120 | 0.087 | 0.040 |

| Drinking alcohol Y/N in the past 30 days1 | -0.056 | 0.213** | -0.004 | 0.000 | -0.001 | 0.105 | -0.131 | 0.042 |

| 4/5 or more alcohol drinks1 | -0.048 | 0.211** | -0.070 | 0.003 | -0.015 | -0.136* | 0.108 | 0.040 |

| Largest number of drinks1 | -0.067 | 0.234** | 0.039 | -0.003 | 0.009 | 0.053 | -0.053 | 0.039 |

| Currently smoking1 | -0.056 | 0.211** | -0.020 | 0.001 | -0.004 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.041 |

| Vigorous activities minutes / week1 | -0.035 | 0.189** | 0.087 | -0.003 | 0.016 | 0.018 | -0.013 | 0.040 |

| Moderate activities minutes / week1 | -0.045 | 0.196** | -0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | -0.068 | 0.064 | 0.039 |

| Walking minutes / week1 | -0.046 | 0.207** | -0.041 | 0.002 | -0.008 | -0.003 | -0.028 | 0.039 |

| Last mammogram (within last 2 years vs. > 2 years or never)2 | -0.032 | 0.170 | 0.016 | -0.001 | 0.003 | 0.090 | -0.038 | 0.044 |

| Ever had a PSA test2 | -0.098 | 0.126 | -0.025 | 0.002 | -0.003 | -0.126 | 0.320** | 0.049 |

| Ever had a colonoscopy1 | -0.042 | 0.196** | -0.010 | 0.000 | -0.002 | 0.025 | -0.073 | 0.040 |

Note.

Age, gender, education and self-rated health were adjusted.

Age, education and self-rated health were adjusted.

The b32 paths, representing the effect of negative interaction at wave 2 on the change in the outcome from wave 2 to wave 3, were significant only for depressive symptoms (p = .013) and emotional functioning (p = .040). The al*b32 and ah*b32 paths, representing the indirect/mediation effect of religious beliefs and behaviors, respectively, through a change in negative interaction from wave 1 to wave 2, on the change in the outcome from wave 2 to wave 3, were non-significant. This indicates that there is no evidence that negative interaction mediated the relationship between religious beliefs or behaviors and the health-related outcomes examined.

Unmediated effects

This section involves the following paths in Figure 1 and Tables 3 and 4: cl' and ch'. As reported previously (Holt et al., 2017) the cl' and ch' paths, representing the unmediated/direct effect of religious beliefs and behaviors (respectively) at wave 1 on the change in outcomes from wave 2 to wave 3, were similar across both religious social support models and to previous findings. There were several significant paths for fruit/vegetable consumption (ps < .05 - .01), and heavy drinking (p < .05), and men's reports of having a prostate specific antigen test (p < .01). The latent factors for religious beliefs and religious behaviors at wave 1 were substantially correlated (r = 0.70, p < .001) and this affects the interpretation of their opposing direct effects on these outcomes. Because the small negative direct effects for religious beliefs only emerge as statistically significant when controlling for the stronger positive direct effects of religious behaviors, the smaller, counteractive effects for religious beliefs are considered to be suppression effects. Consistent with a previous report (Holt et al., 2017), the longitudinal predictive paths from religious behaviors at one wave to religious beliefs at the subsequent wave were consistent and statistically significant (ps < .001) across all models.

Discussion

This study tested a longitudinal model of religious social support as a potential mediator of the relationship between religious involvement and an array of health-related outcomes in a national sample of African Americans. Even though previous research reported on the mediational role of religious social support based on cross-sectional data, conclusions that can be drawn about mediational relationships using this approach are limited. The present models are considerably more rigorous because they examined change over time. Therefore, we were able to evaluate whether religious involvement is associated with changes in religious social support over time, and whether such changes are associated with changes in health-related outcomes.

Religious involvement and change in religious social support

Our findings indicate that a person's religious behaviors, such as regularly attending church services and participating in other religious activities, appeared to attenuate the modest decrease in positive aspects of religious social support over the 5-year study period. In other words, religious support trended down to a lesser degree for those with more frequent religious behaviors. These findings partially support the first hypothesis, but it is somewhat surprising that levels of religious social support had declined over time in the sample, even if modestly. It is possible that there is a maturation effect, reflecting the finding that as people age, their social network tends to get smaller (Wrzus, Hanel, Wagner, & Neyer, 2013) and this could include one's church social network, an idea echoed in Carstensen's theory of socioemotional selectivity (Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, 1999). The decline in religious social support could also coincide with the modest decline in religious involvement observed in the US overall (Pew Research Center, 2015), however religious involvement did not decline in the current sample.

It was previously reported that a spiritual connectedness (e.g., perceptions that one's faith facilitates connections to others) was associated with providing more emotional and tangible support to fellow church members over time in a sample of older US adults (Krause & Bastida, 2009). Both spiritual connectedness and religious behaviors in the current study (e.g., service attendance; talking about faith with others) reflect a social aspect of religious participation, which in the current study played a greater role than the more private aspects of religious beliefs. This is consistent with previous findings that indicated religious behaviors, but not beliefs, at wave 1 were associated with change in all dimensions of religious social support over time using the data from waves 1 and 2 of the RHIAA study (Le, Holt, Hosack, Huang, & Clark, 2016). Religious involvement did not predict changes in general social support, which supports the unique aspects of the relationship with religious social support, specifically.

Religious social support and change in health outcomes

The second hypothesis involved the relationship between religious social support and health-related outcomes. Our longitudinal findings suggested that positive religious support predicted decreases in depressive symptoms and heavy drinking, while negative interaction predicted increases in depressive symptoms. This illustrates the importance of examining religious social support as a multidimensional construct, and highlights that religious participation can have both positive and negative effects.

Negative interaction was also associated with declines in emotional functioning over time. Previous research supported the association between negative interaction and more depressive symptoms and psychological distress (Chatters et al., 2015). Notably, religious social support, particularly negative interaction, was associated to a greater degree with poorer mental health outcomes in the present study, than with the physical health outcomes. Taken together, these findings confirm previous research suggesting that religious social support may be a protective factor against poor mental health and that positive religious support may protect against binge drinking. They also highlight the negative aspects of religious involvement and that negative interactions with fellow church members can have adverse health consequences.

Religious social support as a religion-health mediator

The current mediation findings echo those reported in our cross-sectional model from the RHIAA study, where religious social support mediated the relationship between religious behaviors and depressive symptoms and emotional functioning, but not for physical functioning. Similarly, we found a longitudinal mediation role of positive religious support in the relationship between religious behaviors, and depressive symptoms and heavy drinking. This provides greater evidence and confidence in the idea that religious participation is important for maintaining positive religious support, which in turn is protective against these negative health outcomes in African Americans. However, mediation was not detected for many of the behavioral outcomes, largely due to the lack of an association between religious social support and health behaviors, again suggesting that while religious social support may play a protective role in mental health-related outcomes, this is not the case for engagement in health-protective behaviors such as fruit/vegetable consumption or physical activity.

Religious behaviors impact on religious beliefs

Informed by a previous finding from the RHIAA data (Roth et al., 2016), a novel path in the current model signified the impact of participants' religious behaviors at tx to religious beliefs at the subsequent time point. This is consistent with Festinger's Cognitive Dissonance Theory (Festinger, 1957) and Bem's Self-Perception Theory (Bem, 1967), suggesting that people align their beliefs in accord with their behaviors. It is a provocative finding, given that most research on the religion-health connection conceptualizes religiosity as a multidimensional construct (Hill & Hood, 1999) with models typically assuming that various facets of religious involvement exert independent effects on outcomes. This robust finding has implications for future research in religion-health models, including those that examine mediation.

Strengths and limitations

The RHIAA dataset provided a unique opportunity to examine complex longitudinal relationships between religious involvement and multiple health-related outcomes in an important group in relation to health disparities. Using data collected for this purpose has the advantage of being able to examine a number of relevant constructs using multidimensional approaches. However, the RHIAA study was not initially designed for participant re-contact, resulting in low retention rates that may introduce bias (as previously described). Some of the variables showed limited change during the study. Perhaps a longer follow-up period may show more robust change, thus increasing the ability of the models to detect mediation.

Implications and conclusions

The present findings have important implications for working with faith-based organizations to foster and protect mental health among African Americans. Interventions designed to capitalize on the natural social networks and social capital in faith communities may be helpful, as well as those that serve to manage conflict and role strain. The current findings suggest that such interventions may have a positive impact on mental health-related issues such as depressive symptoms and heavy drinking. The findings also suggest that while private religious beliefs may have positive direct effects on health-related outcomes, participation in a religious community may be more beneficial when it comes to retaining the support that they can provide, which in turn can have positive mental health impact.

Acknowledgments

The team would like to acknowledge the work of OpinionAmerica and Tina Madison who conducted participant recruitment/retention and data collection activities for the present study.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute, (#1 R01 CA 105202; #1 R01 CA154419) and a grant from the Duke University Center for Spirituality, Theology, and Health, through the John Templeton Foundation (#11993).

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards: Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest Research involving Human Participants Informed consent.

Disclosure of Potential Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Right and Informed Consent: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study involved human data and was approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board (#373528-1). It does not involve animal data or tissue

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Bem D. Self-perception: An alternative interpretation of cognitive dissonance phenomena. Psychological Review. 1967;74:183–200. doi: 10.1037/h0024835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamins MR, Ellison CG, Krause NM, Marcum JP. Religion and preventive service use: do congregational support and religious beliefs explain the relationship between attendance and utilization? Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;34(6):462–476. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block G, Hartman AM, Dresser CM, Carroll MD, Gannon J, Gardner LA. A data-based approach to diet questionnaire design and testing. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1986;124(3):453–469. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer G, Robinson S, Sumra A, Tatsi E, Gire N. The Influence of Religious Coping and Religious Social Support on Health Behaviour, Health Status and Health Attitudes in a British Christian Sample. Journal of Religion and Health. 2015;54(6):2225–2234. doi: 10.1007/s10943-014-9966-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgener SC. Predicting quality of life in caregivers of Alzheimer's patients: the role of support from and involvement with the religious community. Journal of Pastoral Care. 1999;53(4):433–446. doi: 10.1177/002234099905300406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JD, Yoon DP, Johnstone B. Determining relationships between physical health and spiritual experience, religious practices, and congregational support in a heterogeneous medical sample. Journal of Religion and Health. 2010;49(1):3–17. doi: 10.1007/s10943-008-9227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Isaacowitz DM, Charles ST. Taking time seriously. A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist. 1999;54(3):165–181. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.3.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM. Religion and health: Public health research and practice. Annual Review Public Health. 2000;21:335–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Woodward AT, Nicklett EJ. Social support from church and family members and depressive symptoms among older African Americans. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2015;23(6):559–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Basic psychometrics for the ISEL 12 item scale. 2009 Retrieved June 12, 2010. Retrieved from http://www.psy.cmu.edu/∼scohen.

- Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, Oja P. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2003;35(8):1381–1395. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000078924.61453.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debnam K, Holt CL, Clark EM, Roth DL, Southward P. Relationship between religious social support and general social support with health behaviors in a national sample of African Americans. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;35(2):179–189. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9338-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Hummer RA. Religion families and health: Population-based research in the United States. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Levin JS. The religion-health connection: Evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Education & Behavior. 1998;25(6):700–720. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. A theory of cognitive dissonance. California: Stanford University Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer Institute: National Institute on Aging Working Group. Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/Spirituality for use in health research. Kalamazoo, MI: John E. Fetzer Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- George LK, Larson DB, Koenig HG, McCullough ME. Spirituality and health: What we know, what we need to know. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2000;19(1):102–116. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2000.19.1.102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward RD, Krause N. Trajectories of disability in older adulthood and social support from a religious congregation: a growth curve analysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2013;36(4):354–360. doi: 10.1007/s10865-012-9430-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill PC, Hood RW Jr, editors. Measures of religiosity. Birmingham, AL: Religious Education Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Holt CL, Clark EM, Debnam KJ, Roth DL. Religion and Health in African Americans: The Role of Religious Coping. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2014;38(2):190–199. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.38.2.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CL, Le D, Calvanelli J, Huang J, Clark E, Roth DL, Schulz E. Participant retention in a longitudinal national telephone survey of African American men and women. Ethnicity and Disease. 2015;25(1):187–192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CL, Roth DL, Huang J, Park C, Clark EM. Longitudinal effects of religious involvement on religious coping and health behaviors in a national sample of African Americans. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.06.014. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CL, Schulz E, Wynn TA. Perceptions of the religion-health connection among African Americans: Sex, age, and urban/rural differences. Health Education and Behavior. 2009;36(1):62–80. doi: 10.1177/1090198107303314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CL, Wang MQ, Clark EM, Williams BR, Schulz E. Religious involvement and physical and emotional functioning among African Americans: the mediating role of religious support. Psychology Health. 2013;28(3):267–283. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2012.717624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanu M, Baker E, Brownson RC. Exploring associations between church-based social support and physical activity. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2008;5(4):504–515. doi: 10.1123/jpah.5.4.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, King DE, Carson VB. Handbook of Religion and Health. 2nd. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, McCullough ME, Larson DB. Handbook of Religion and Health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press USA; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Church-based social support and health in old age: Exploration variations by race. Journal of Gerontology. 2002;57B(6):S332–S347. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.s332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Bastida E. Core Religious Beliefs and Providing Support to Others in Late Life. Mental Health, Religion and Culture. 2009;12(1):75–96. doi: 10.1080/13674670802249753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Ellison CG, Shaw BA, Marcum JP, Boardman JD. Church-based social support and religious coping. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2001;40(4):637–656. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, Skinner CS, Holt CL, Clark EM, Haire-Joshu D, Fu Q, Bucholtz DC. Cultural tailoring for mammography and fruit and vegetable consumption among low-income African American women in urban public health centers. Preventive Medicine. 2005;41(1):53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le D, Holt CL, Hosack DP, Huang J, Clark EM. Religious Participation is Associated with Increases in Religious Social Support in a National Longitudinal Study of African Americans. Journal of Religion and Health. 2016;55(4):1449–1460. doi: 10.1007/s10943-015-0143-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS, Vanderpool HY. Is religion therapeutically significant for hypertension? Social Science and Medicine. 1989;29(1):69–78. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90129-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukwago SL, Kreuter MW, Bucholtz DC, Holt CL, Clark EM. Development and validation of brief scales to measure collectivism, religiosity, racial pride, and time orientation in urban African American women. Family and Community Health. 2001;24(3):63–71. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200110000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Makambi KH, Williams CD, Taylor TR, Rosenberg L, Adams-Campbell LL. An assessment of the CES-D scale factor structure in black women: The Black Women's Health Study. Psychiatry ResearchPsychiatry Research. 2009;168:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maselko J, Hayward RD, Hanlon A, Buka S, Meador K. Religious Service Attendance and Major Depression: A Case of Reverse Causality? American Journal of Epidemiology. 2012;175(6):576–583. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE, Cole DA. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods. 2007;12(1):23–44. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhee SJ, Nguyen TT, Shema SJ, Nguyen B, Somkin C, Vo P, Pasick R. Validation of recall of breast and cervical cancer screening by women in an ethnically diverse population. Preventive Medicine. 2002;35(5):463–473. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musick MA, Traphagan JW, Koenig HG, Larson DB. Spirituality in physical health and aging. Journal of Adult Development. 2000;7(2):73–86. doi: 10.1023/A:1009523722920. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. 7th. Los Angeles, CA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Oman D, Thoresen CE. Does religion cause health? Differing interpretations and diverse meanings. Journal of Health Psychology. 2002;7(4):365–380. doi: 10.1177/1359105302007004326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Feuille M, Burdzy D. The Brief RCOPE: Current psychometric status of a short measure of religious coping. Religions. 2011;2:51–76. doi: 10.3390/rel2010051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. U.S. Public Becoming Less Religious. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.pewforum.org/2015/11/03/u-s-public-becoming-less-religious/

- Powell LH, Shahabi L, Thoresen CE. Religion and spirituality: Linkages to physical health. American Psychologist. 2003;58(1):36–52. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rauscher GH, Johnson TP, Cho YI, Walk JA. Accuracy of self-reported cancer screening histories: A meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers, and Prevention. 2008;17:748–757. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth DL, Ackerman ML, Okonkwo OC, Burgio LD. Factor model of depressive symptoms in dementia caregivers: A structural equation model of ethnic differences. Psychology and Aging. 2008;23:567–576. doi: 10.1037/a0013287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth DL, MacKinnon DP. Mediation analysis with longitudinal data. In: Newsom JT, Jones RN, Hofer SM, editors. Longitudinal data analysis: A practical guide for researchers in aging, health, and social sciences. New York: Routledge; 2012. pp. 181–216. [Google Scholar]

- Roth DL, Mwase I, Holt CL, Clark EM, Lukwago S, Kreuter MW. Religious involvement measurement model in a national sample of African Americans. Journal of Religion and Health. 2012;51(2):567–578. doi: 10.1007/s10943-011-9475-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth DL, Usher T, Clark EM, Holt CL. Religious Involvement and Health Over Time: Predictive Effects in a National Sample of African Americans. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2016;55(2):417–424. doi: 10.1111/jssr.12269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic Confidence Intervals for Indirect Effects in Structural Equation Models. Sociological Methodology. 1982;13:290–312. doi: 10.2307/270723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein AD, Lederman RI, Shea S. The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System questionnaire: its reliability in a statewide sample. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83(12):1768–1772. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.83.12.1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Levin J. Religion in the lives of African Americans: Social, psychological, and health perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Thoresen CE. Spirituality, health, and science: The coming revival? In: Roth-Roemer S, Kurpius SR, editors. The emerging role of counseling psychology in health care. New York: W. W. Norton; 1998. pp. 409–431. [Google Scholar]

- VandeCreek L, Pargament K, Belavich T, Cowell B, Friedel L. The unique benefits of religious support during cardiac bypass surgery. Journal of Pastoral Care. 1999;53(1):19–29. doi: 10.1177/002234099905300104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb M, Charbonneau AM, McCann RA, Gayle KR. Struggling and enduring with God, religious support, and recovery from severe mental illness. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2011;67(12):1161–1176. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR. Miles to go before we sleep: racial inequities in health. Journal of health and social behavior. 2012;53(3):279–295. doi: 10.1177/0022146512455804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrzus C, Hanel M, Wagner J, Neyer FJ. Social network changes and life events across the life span: a meta-analysis. Psychology Bulletin. 2013;139(1):53–80. doi: 10.1037/a0028601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]