Abstract

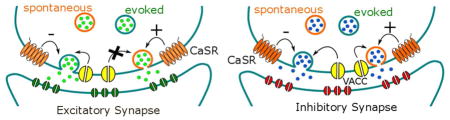

Spontaneous release of neurotransmitter is regulated by extracellular [Ca2+] and intracellular [Ca2+]. Curiously, some of the mechanisms of Ca2+ signaling at central synapses are different at excitatory and inhibitory synapses. While the stochastic activity of voltage-activated Ca2+ channels trigger a majority of spontaneous release at inhibitory synapses, this is not the case at excitatory nerve terminals. Ca2+ release from intracellular stores regulates spontaneous release at excitatory and inhibitory terminals, as do agonists of the Ca2+-sensing receptor. Molecular machinery triggering spontaneous vesicle fusion may differ from that underlying evoked release and may be one of the sources of heterogeneity in release mechanisms.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Fast inter-neuronal signaling is evoked by a presynaptic action potential that synchronizes voltage- activated calcium channel (VACC) openings and mediates Ca2+ entry into the nerve terminal. The subsequent transient uptick in intracellular [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]i), triggers vesicle exocytosis and neurotransmitter release. Over 60 years ago, Katz and colleagues determined that neurotransmitter release also occurred in the absence of a presynaptic action potential (spontaneous release) in recordings at the frog neuromuscular junction. Since these fundamental discoveries, spontaneous release has been identified at synapses throughout the nervous system. The physiological importance of spontaneous release was underscored with the recognition that it is crucial for synaptic development and plasticity (Andreae et al. 2012; McKinney et al. 1999), that it may influence neuronal spiking patterns (Carter and Regehr 2002), and possibly mediate rapid antidepressant effects of ketamine (Autry et al. 2011). Nowadays, the process is usually studied by recording the membrane current in a single neuron and the release of a single vesicle, from one of several hundred synapses, is detected as a rapid current deflection that decays with an exponential time course over several milliseconds while action potentials are blocked with tetrodotoxin (Fig. 1). The spontaneous events, or minis, occur randomly and the frequency in each recording will depend on factors such as temperature and the number of synapses (Fig. 1a). This review will focus on the effect of Ca2+, another major determinant of spontaneous release, and examine the effects of both extracellular [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]o) and intracellular [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]i).

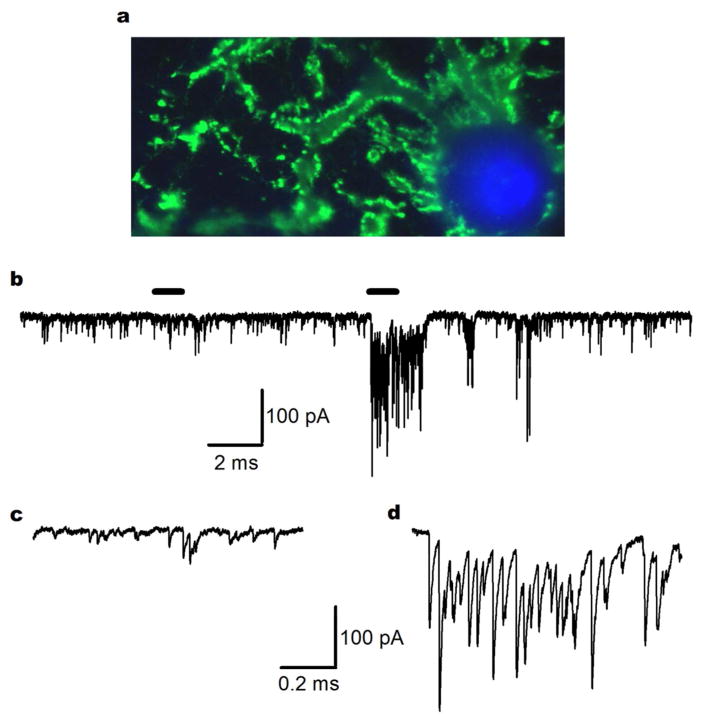

Figure 1.

Random variability in the rate of spontaneous release. a Fluorescent micrograph labeled for synaptophysin (green) and DAPI (blue) illustrates that alarge number of nerve terminals may synapse onto a singleneocortical neuron. Spontaneous release will increase with the number of synaptic contacts, along with other factors including temperature. b Exemplary trace of miniature inhibitory post-synaptic currents (mIPSCs) from cortical cultured neurons recorded at −70 mV under previously described conditions (Williams et al. 2012). Horizontal bars above the trace indicate the traces used in c and d. The stochastic nature of spontaneous release results in a variable frequency and amplitude of events as shown. c Expanded time course from the trace in b to indicate basal mIPSC frequency. d Expanded timecourse from the trace in b to show a portion of the recording where a high frequency “burst” of mIPSCs was taking place.

[Ca2+]o dependence of Spontaneous and Evoked Release

There is substantial interest in the [Ca2+]o dependence of neurotransmission because of its central role as a trigger of exocytosis. Early studies of neurotransmission identified large differences in the [Ca2+]o dependence of spontaneous and evoked release. Dodge and Rahamimoff observed that evoked release was proportional to the fourth power of [Ca2+]o at the frog neuromuscular junction, which was confirmed in a number of preparations (Augustine and Charlton 1986; Borst and Sakmann 1996; Dodge and Rahamimoff 1967). The slope of the log-log transform of the concentration-effect relationship (n) reflects the high intrinsic Ca2+ cooperativity of activation of the exocytotic machinery, and represents a minimum number of Ca2+ binding steps required to trigger vesicle fusion (Matveev et al. 2011). This contrasts with the relatively weak dependence of spontaneous release on [Ca2+]o observed at the neuromuscular junction where n is 0.21–0.41 (Boyd and Martin 1956; Hubbard 1961; Hubbard et al. 1968; Matthews and Wickelgren 1977). At neocortical excitatory and inhibitory synapses, the dependence of spontaneous release on [Ca2+]o was similarly low (n = 0.45–0.63) (Groffen et al. 2010; Vyleta and Smith 2011; Williams et al. 2012). Likewise at the Calyx of Held, a large central synapse, n for spontaneous release is 0.43 (Dai et al. 2015). Overall spontaneous release is [Ca2+]o dependent, albeit with a weaker concentration-dependence than evoked release. This raises the question, how do changes in [Ca2+]o affect spontaneous neurotransmission in the absence of a synchronizing action potential?

Stochastic VACC activity and spontaneous release

Since evoked release is astoundingly sensitive to Ca2+ and can be triggered by only 1 or 2 VACCs per vesicle at some synapses (Bucurenciu et al. 2010; Shahrezaei et al. 2006; Stanley 1993), stochastic activation of VACCs could provide the mechanism for spontaneous release at rest (Matthews and Wickelgren 1977). Certainly at the neuromuscular junction, pharmacological block of VACC currents reduced spontaneous release of acetylcholine, indicating VACC regulate spontaneous release (Losavio and Muchnik 1997; Losavio and Muchnik 1998). Multiple subtypes of VACCs contributed to spontaneous release (N- and L specifically), but about 35% of spontaneous release is apparently independent of VACC activity (Losavio and Muchnik 1997; Losavio and Muchnik 1998).

In the central nervous system the picture is more complex, as VACCs have different roles at different synapses. At sensory cells that contain ribbon synapses, graded changes in membrane potential regulate release by changing the probability of VACC activity when action potentials cannot be generated (Graydon et al. 2011; Li et al. 2009). L-type VACCs with unusual activation curves, where gating has been shifted by around −30 mV and results in almost 50% activation at −40 mV, trigger release at these synapses (Helton et al. 2005). It follows that a modest depolarization can trigger ribbon synapses to release glutamate in a VACC-dependent fashion without needing the strong depolarization of an action potential (Graydon et al. 2011; Trapani and Nicolson 2011). However, even within sensory cells the role of VACCs can be more complex. In photoreceptors there are both VACC-dependent and [Ca2+]i –dependent components of spontaneous release with the former being more concentrated around ribbons (Cork et al. 2016).

In sharp contrast, spontaneous release of glutamate at conventional central excitatory synapses does not appear to be dependent on VACC activity (Table 1). A majority of investigations reported that block of VACCs does not reduce spontaneous release of glutamate at excitatory synapses in the central nervous system. In cultured hippocampal neurons from neonatal rats, Cd2+, a non-selective VACC blocker, did not affect mEPSC frequency (Abenavoli et al. 2002). In cultured mouse neurons from neocortex, VACC block with Cd2+ or MVIIC did not reduce mEPSC frequency (Tsintsadze et al. 2017; Vyleta and Smith 2011). In hippocampal, neocortical, cerebellar, and brainstem slices from mice, spontaneous release of glutamate was also independent of VACC activity (Eggermann et al. 2011; Tsintsadze et al. 2017; Yamasaki et al. 2006). Unlike excitatory synapses, at the majority of central inhibitory synapses, VACCs are important physiological triggers for spontaneous release (Table 1) (Goswami et al. 2012; Tsintsadze et al. 2017; Williams et al. 2012; Yamasaki et al. 2006). The frequency of spontaneous release at these synapses is decreased by application of VACC blockers. Just as at the neuromuscular junction, Cd2+ substantially reduced spontaneous release with a fast course of action (Tsintsadze et al. 2017; Williams et al. 2012). Using selective VACC blockers, P/Q-, N-, L-, and R-type VACCs were shown to regulate spontaneous release of GABA, although a minority of mIPSCs were independent of VACC activity (Goswami et al. 2012; Williams et al. 2012). Spontaneous release of GABA, in acute brain slices from the neocortex and brainstem, was also inhibited by VACC blockers (Tsintsadze et al. 2017), indicating that in many areas of the brain VACCs regulate inhibitory, but not excitatory spontaneous synaptic transmission (however see Scanziani et al. 1992). The regulation of mIPSCs by VACCs is fundamentally different from that of mEPSCs at both small bouton-type and large calyx-type central synapses. This effect is widespread within the CNS and has been observed in culture and acute brain slices, but does not hold for receptors such as hair cells and photoreceptors.

Table 1.

Heterogeneity in VACC-dependence of spontaneous release of glutamate and GABA from central synapses

| Synapse | VACC dependence? | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| GABAergic synapses from hippocampal granule cells in rat hippocampal slices | yes | (Goswami et al. 2012) |

| GABAergic synapses in mouse neocortical culture | yes | (Williams et al. 2012) |

| GABA release from rat medial preoptic nerve | yes | (Druzin et al. 2002) |

| GABAergic synapses in dissociated rat basolateral amygdala neurons | yes | (Koyama et al. 1999) |

| Inhibitory synapses in mouse neocortical and auditory brainstem slice and neocortical culture | yes | (Tsintsadze et al. 2017) |

| Glutamatergic synapses in rat hippocampal cultures | yes | (Ermolyuk et al. 2013) |

| Glutamatergic synapses in slices of hamster and rat spinal laminae I and II | yes | (Bao et al. 1998) |

| Glutamate release from juvenile mouse calyx of held | yes | (Dai et al. 2015) |

| Glutamatergic and GABAergic synapses onto mouse cerebellar Purkinje cells | no | (Yamasaki 2006) |

| Glutamatergic synapses in rat hippocampal cultures | no | (Abenavoli et al. 2002) |

| Glutamatergic synapses in rat hippocampal slice culture | no | (Scanziani et al. 1992) |

| Glutamatergic synapses in mouse neocortical culture | no | (Vyleta & Smith 2011) |

| Glutamatergic synapses from hippocampal granule cells in rat hippocampal slices | no | (Eggermann et al. 2011). |

| Glutamatergic synapses in mouse neocortical and auditory brainstem slice and neocortical culture | no | (Tsintsadze et al. 2017) |

Mechanisms behind differences in VACC regulation of spontaneous release

While a majority of groups reported VACCs do not trigger mEPSCs at conventional central synapses in culture and acute brain slices, others report the contrary (Dai et al. 2015; Ermolyuk et al. 2013; Xu et al. 2009)? One hypothesis to explain the discrepancy is that Cd2+ may enter the cell and increase [Ca2+]i via off-target mechanisms (Ermolyuk et al. 2013), leading to vesicle depletion so that block of VACCs has no detectable impact on synaptic transmission. Consistent with this idea, Cd2+ does permeate VACCs (Chow 1991), and directly increases Fluo-4 fluorescence (Hinkle et al. 1992; Johnson and Spence 2010; Lopin et al. 2012). However, since spontaneous excitatory transmission remained intact in the presence of Cd2+ (Tsintsadze et al. 2017; Vyleta and Smith 2011) this argues against the vesicle depletion hypothesis. Moreover, Cd2+ was effective on spontaneous release from inhibitory synapses but not excitatory synapses recorded simultaneously, making it unlikely that Cd2+ was poisoning synaptic transmission via a VACC-independent pathway(Tsintsadze et al. 2017). Furthermore, in studies in which Cd2+ was ineffective at reducing mEPSCs specific VACC blockers, like MVIIC, were also ineffective (Tsintsadze et al. 2017; Vyleta and Smith 2011). So why did specific VACC blockers impact mEPSC frequency in some studies (Ermolyuk et al. 2013; Xu et al. 2009) neurons but not others. We propose VACC-dependent mEPSCs may be attributable to the preparation being relatively depolarized or developmentally distinct. Modeling studies indicate that a 10 mV depolarization in membrane potential would significantly increase the likelihood of stochastic activation of VACCs, and thus cause an increase in VACC-dependent spontaneous release (Ermolyuk et al. 2013). Additionally, laboratories that detected VACC regulation of mEPSC frequency at small central neurons used external solutions with higher K+, Ca2+, glucose and buffer concentrations (Ermolyuk et al. 2012; Xu et al. 2009). However, switching to solutions with higher K+, Ca2+, glucose and buffer concentrations did not change the sensitivity of mEPSCs to VACC blockers, indicating any relatively depolarized preparation must have arisen for other reasons (Tsintsadze et al. 2017). It is possible that the preparations were developmentally distinct. Interestingly, growth differential factor-15 (GDF-15) was shown to upregulate mEPSC frequency in neocortical slices and this was prevented by simultaneous block of T-type VACC currents (Cav3.1 and 3.3) (Liu et al. 2016). Basal mEPSC frequency, prior to GDF-15 treatment, was insensitive to T-type VACC blockers but T-type VACC currents were essential for GDF-15–mediated mEPSC up-regulation. It remains to be determined if T-type VACCs also regulate spontaneous release once upregulation has occurred (Liu et al. 2016). Overall, the ineffectiveness of VACC blockers on the majority of spontaneous release at excitatory synapses in acute brain slices underlines the existence of distinct actions of VACCs on spontaneous release of GABA and glutamate.

The mechanism underlying the heterogeneity in VACC-dependence of spontaneous release between excitatory and inhibitory synapses requires further investigation. Specifically, these investigations should determine differences between excitatory and inhibitory synapses in: resting membrane potential, number or type of VACCs, size of the Ca2+ domain for release, tightness of coupling between VACCs and vesicles, concentrations and potency of intracellular Ca2+ buffers, and the proteins that comprise the release machinery. Differences in synaptic protein isoforms are well recognized (Geppert et al. 1994; Sun et al. 2007a), and are a putative mechanism to explain why VACCs trigger spontaneous release at inhibitory but not excitatory synapses. Since VACCs trigger evoked release at both types of synapse, this explanation would also necessitate differences in synaptic vesicle protein composition for evoked and spontaneous release (Crawford and Kavalali 2015), or that the same synaptic proteins mediate evoked and spontaneous release but through different molecular mechanisms (Dai et al. 2015).

How Many VACCs are required to Trigger Spontaneous Release of GABA?

If stochastic opening of VACCs is the gateway for Ca2+ entry that triggers spontaneous vesicle fusion at the neuromuscular junction and central inhibitory synapses, are there enough stochastic VACC openings to account for the observed frequency of spontaneous neurotransmission? The frequency of random VACC openings in the inhibitory terminals synapsing with a single neocortical neuron (Fro) was estimated using eq. 1 (Smith et al. 2012).

| eq. 1 |

Where NT was the number nerve terminals per neuron, Pri was the proportion of synapses that are inhibitory, NVACC was the number of VACC per terminal, PVACC was the probability that a VACC was open and T was the average channel open time at the membrane potential. The estimate of the average Fro was more than 100 times greater than the average measured mIPSC frequency (513 s−1 versus 4.4 s−1, respectively), indicating that there are 100-fold more VACC openings than vesicle fusion events at inhibitory synapses (Smith et al. 2012).

However at most synapses, the simultaneous activation of multiple VACCs has been implicated as necessary to trigger single vesicle fusion during evoked release (see(Bucurenciu et al. 2010; Eggermann et al. 2011; Stanley 1997)). Is this the same for spontaneous release? If each spontaneous fusion event depends on the opening of a single channel, the fraction of VACCs blocked should be proportional to the fraction of spontaneous release inhibited with slowly dissociating toxins. Conversely, if multiple channels are involved, cooperativity will result in proportionately smaller reductions in release probability as a larger fraction of VACCs are blocked (Mintz et al. 1995; Wheeler et al. 1996).

Consistent with multiple channel involvement, at the rat neuromuscular junction the relative effectiveness of L-type and N-type VACC blockers was reversed when the order of application was switched (Losavio and Muchnik 1998). Similarly, at neocortical inhibitory synapses N-type and P/Q-type blockers were more effective at reducing mIPSC frequency when the neuron had not been exposed to saturating doses of the other blocker (Williams et al. 2012). These two studies indicate that at GABAergic synapses and the neuromuscular junction spontaneous release is triggered by the cooperative activation of multiple VACCs, and this may be the case for spontaneous release at other synapses as well.

How could synchronized activation of more than one VACC occur? Spontaneous stochastic activity of VACCs at the resting membrane potential seems unlikely given the low basal rate of activity (see above). However, this may be more plausible if VACCs at nerve terminals occasionally occupy high-probability gating modes, as has been observed at neuronal soma (Delcour et al. 1993; Kavalali and Plummer 1994). If a fraction of VACCs enter a high-probability gating mode, this would substantially increase the likelihood that simultaneous VACC openings occur stochastically and thus trigger spontaneous release. Protein kinase C targeting, via AKAP150, is one mechanism that has been identified to facilitate high open probability modes for L-type VACCs (Navedo et al. 2008). Moreover it has been proposed that this mechanism facilitates functional coupling of neighboring VACCs via their C-termini, leading to synchronized activation (Navedo et al. 2010). Whether synchronization of activation of multiple VACC at the nerve terminal occurs stochastically or is due to a physiological link remains unknown.

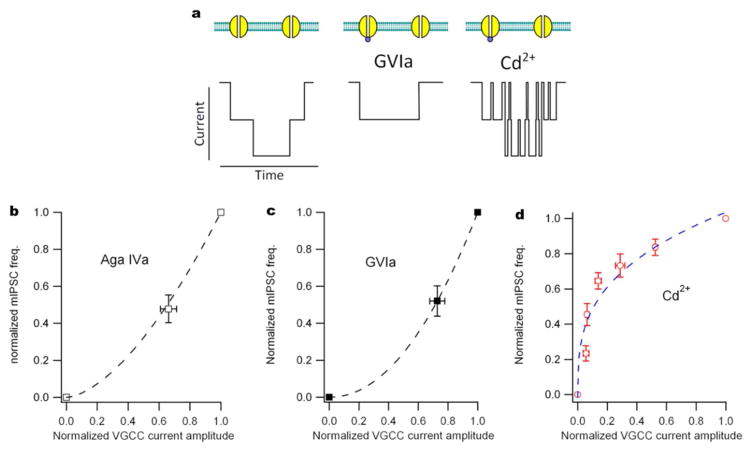

The minimum number of VACCs required to trigger spontaneous release at inhibitory synapses is unclear. Utilization of a model to describe the impact of VACC blockers on action potential-dependent Ca2+ transients and synaptic transmission in small nerve terminals indicated that release occurred as a result of the opening of ≤3 VACCs (Bucurenciu et al. 2010). Modifying this approach to look at the relationship between block of VACC-dependent spontaneous release and VACC- currents by both N-type and P/Q-type channel blockers, revealed a relationship in which mIPSC frequency was more greatly impacted than VACC currents by specific VACC blockers (Fig. 2). The degree of non-linearity was very similar to that reported for evoked release (Bucurenciu et al. 2010), consistent with similar stoichiometry (≤3 VACCs per vesicle) in the coupling between VACC and vesicles for spontaneous and evoked release. However, this hypothesis is dependent on the somatic and terminal VACCs being similarly sensitive to these blockers since these VACC currents were recorded from neuronal soma. Interestingly, in similar experiments using Cd2+ as the VACC blocker, the mIPSC frequency-VACC current relationship was reversed (Fig. 2d). This increase in the effectiveness of Cd2+ on VACC currents recorded at −10 mV compared to spontaneous release at resting membrane potential is mainly attributable to the increased block by Cd2+ at depolarized membrane potentials (Chow 1991; Tsintsadze et al. 2017). However, since spontaneous release of GABA relies on coincident VACCs opening (Williams et al. 2012), the relative loss of affinity of Cd2+ on mIPSC frequency may also arise from its flickery block of VACCs (Lansman et al. 1986) which, unlike irreversible blockers, does not preclude multiple VACC openings (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Non-linear actions of VACC blockers on VACC currents and mIPSCs. a Cartoon of VACC current through two single channels indicating the effects of different types of channel blockers. The center illustration shows block by a selective “irreversible” blocker for N-type VACCs (GVIa, 1μM). The illustration on the right shows the result of blocking channels with Cd2+, which is nonselective and results in “flickery” block of the current (Lansman et al, 1986). b Plot of normalized mIPSC frequency versus normalized VGCC current amplitude in the presence and absence of a saturating dose of Aga Iva (300 nM), a selective P/Q-type channel antagonist. VACC currents were elicited by steps from −70 to −10 mV and mIPSC frequency was recorded at −70 mV, both in cultured neocortical neurons as previously described (Tsintsadze et al. 2017). Data are normalized average frequency (n=4) and average current (n=5) and represent the fraction the mIPSCs and VACC currents that are sensitive to a saturating dose of Cd2+ (300 μM). c Plot of normalized mIPSC frequency versus normalized VGCC current amplitude in the presence and absence of a saturating dose of GVIa (1μM), a selective N-type channel antagonist. Data are average frequency (n=9) and VACC current amplitude (n=5) recorded and normalized as for b. d Plot of normalized mIPSC frequency (n= 9) versus normalized VGCC current amplitude (n=13) in the presence of 0, 1, 3, 10, 30, 100, and 300 μM Cd2+. Recordings made as previously described(Tsintsadze et al. 2017). Note the differences in the shapes of the curves in b and c from the curve in d. If more than one channel contributes to spontaneous release, the relationship between release probability and the size of the Ca2+ current will be supralinear.

Localized changes in [Ca2+]i at resting membrane potential

The [Ca2+]i transient produced by an action potential at a nerve terminal will be substantially different from that elicited by spontaneous activation of a VACC at the resting membrane potential. Since 35–70% of the VACCs at each nerve terminal would be activated by an action potential (Borst and Sakmann 1998; Yang and Wang 2006), a spike should result in the opening of 8–15 VACCs on average at a small nerve terminal (Li et al. 2007; Luo et al. 2011; Smith et al. 2012). If only 1–3 VACCs trigger spontaneous release, the integral of total Ca2+ influx into the terminal accompanying evoked release will be greater than for spontaneous. The signal detected by the vesicle in either form of release may be affected by [Ca2+]i transient overlap resulting from coincident activation of clustered VACCs. Certainly for evoked release the transient overlap varies depending on synapse type and age (Bucurenciu et al. 2008; Nakamura et al. 2015) and variation in the number of channels activated may be substantial and account for non-uniformities in release probability (Ermolyuk et al. 2012). Another difference between evoked and spontaneous Ca2+ transients is expected because of the voltage-dependent gating of calcium channels. Faster deactivation rates for VACCs at the resting membrane potential, during spontaneous VACC activation, will be reflected by shorter mean open times and shorter Ca2+ domain life-times (Delcour et al. 1993; King and Meriney 2005; Luvisetto et al. 2004). In contrast, the driving voltage (VD) for Ca2+ (the difference between membrane potential and reversal potential for Ca2+ (ECa)) will be higher during spontaneous release than during an action potential on average, generating a higher initial flow of Ca2+ and greater peak Ca2+ transient. This difference arises because the measured ECa for VACC currents at physiological divalent concentrations of ~65 mV (Smith et al. 2012; Tsintsadze et al. 2017) will result in a VD of around 55 mV, if peak VACC activation occurs close to the peak of the action potential (10 mV; (Hoppa et al. 2014)), whereas VD will be closer to 133 mV at the resting membrane potential (−78 mV; (Smith et al. 2012)). The peak and volume of the transient Ca2+ domain following VACC opening will be determined, in part, by [Ca2+]o because the single channel current amplitude will increase with [Ca2+]o (Weber et al. 2010). Consequently, increases in [Ca2+]o may increase mIPSC frequency by stimulating nearby vesicles more strongly and by reaching more vesicles (Fig. 3). At ribbon synapses increases in [Ca2+]o also increase the amplitude of spontaneous release events due to highly synchronous multi-vesicular release (MVR) following Ca2+ entry via randomly activated VACCs (Graydon et al. 2011). Since VACCs trigger spontaneous release of GABA at neocortical synapses we asked do rises in [Ca2+]o result in multi-vesicular release at inhibitory neocortical synapses? Increasing [Ca2+]o from 1.1 to 6 mM increased mIPSC frequency (Fig. 4a) which resulted in a substantial reduction in the inter-event interval (IEI) from 192 ± 63 ms (n=8) to 118 ± 32 ms on average (n=8, see Fig. 4j, p=6×10−5). There was no corresponding change in the mIPSC amplitude, indicating that highly synchronized multi-vesicular fusion was not triggered by increasing [Ca2+]o at these synapses (Fig. 4i and k). By acquiring long stable recordings we examined the effect of increasing [Ca2+]o from 1.1 to 6 mM on the distribution of IEI to test if there were any evidence of Ca2+-dependent coordination of release. We hypothesized that coordination of vesicle fusion or mIPSC bursting would preferentially increase the fraction of events with a much shorter IEI. To minimize non-uniformity of errors the histogram shows square root of event number against the logarithm of IEI (Sigworth and Sine 1987). At 1.1 mm Ca2+ the mIPSCs were described by the sum of two exponential distributions with time constants of 0.046 and 0.14 s (Fig. 4h and l). The increased frequency at 6 mM Ca2+ was well-described by two exponential with time constants of 0.034 and 0.089 s. This is substantially longer than the sub-millisecond delay that arises at the hair cell synapse and indicates the increased frequency is unlikely to arise from the same mechanism (Graydon et al. 2011). In fact the majority of the rise in frequency of mIPSCs is attributed to a shortening of the IEI in the longer exponential distribution. In similar experiments examining IEIs for spontaneous release of glutamate the effect of increasing [Ca2+]o to 6 mM was similar to that seen at inhibitory synapses. There was no increase in mEPSC amplitude (Fig. 4c and e), the IEI was reduced in a graded manner (Fig. 4d; 231 ± 44 ms to 85 ± 13 ms; n = 9), and there was no significant change in the time constants for the double exponential fit of the distribution of IEIs (Fig. 4f).

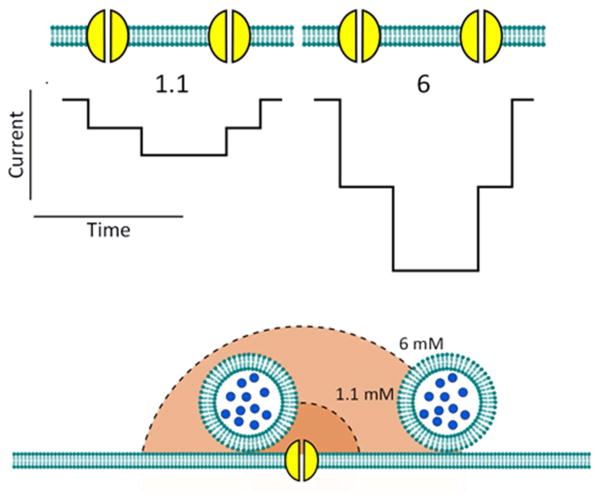

Figure 3.

Single channel currents and Ca2+ domains. (Upper panel) Illustration of VACC current through two single channels in 1.1 and 6 mM [Ca2+]o. Note that the single channel current in 6 mM [Ca2+]o is approximately 3-fold larger than physiological [Ca2+]o (Weber et al. 2010). (Lower panel) Illustration showing the side view of the Ca2+ domain with 2 synaptic vesicles in 1.1 and 6 mM [Ca2+]o. With a higher [Ca2+]o, the Ca2+ domain may also increase 3-fold.

Figure 4.

Spontaneous release is increased by external calcium in cultured neocortical neurons without MVR. a and g Exemplary mIPSC and mEPSCs, respectively, in 1.1 (top, black) and 6 (bottom, blue/red) mM [Ca2+]o. Recordings were made as reported previously (Vyleta and Smith 2011; Williams et al. 2012). b and h Histogram of inter-event interval (IEI) for mIPSCs or mEPSCs in 1.1 (black) and 6 (blue/red) mM [Ca2+]o from the same experiments in a and g. The signal-to-noise is reduced by plotting the square root of the ordinate and using logarithmic binning. Histograms are fit with double exponentials. c and i Histogram of amplitude of mIPSCs or mEPSCs in 1.1 (black) and 6 (blue/red) mM [Ca2+]o from the same experiments in a and g. d – k Cumulative probability plots for IEI and amplitude of mIPSCs or mEPSCs in 1.1 (black) and 6 (blue/red) mM [Ca2+]o from the same experiments in a and g. f and l Average time constants (1st and 2nd Taus) from the double exponential fit of the IEI histograms for mIPSCs (n=9) and mEPSCs (n=8). Black bars indicate time constants in 1.1 [Ca2+]o and 6 blue/red bars represent time constants in 6 mM [Ca2+]o.

The tightness of coupling between VACC and transmitter-containing vesicles has been evaluated with calcium chelators at many synapses (Eggermann et al. 2011). BAPTA and EGTA, have similar affinities for Ca2+ but BAPTA has a ~40 times faster rate of binding so that at mM concentrations BAPTA will attenuate Ca2+ signaling if the mean diffusion distance is as short as 10–20 nm, whereas EGTA will only have an effect if the Ca2+path length is longer (>100 nm)(Eggermann et al. 2011). Using these criteria spontaneous release in the hippocampus has been shown to be triggered by Ca2+ microdomains whereas in the neocortex VACC-vesicle coupling is tighter and dependent on Ca2+ nanodomains (Goswami et al. 2012; Williams et al. 2012). A Ca2+ nanodomain promotes higher release probability and temporal precision of neurotransmission, as tighter coupling minimizes the diffusion component of the synaptic delay (Bucurenciu et al. 2008; Christie et al. 2010; Meinrenken et al. 2002). In contrast, Ca2+ microdomains allow for more modulation by Ca2+ buffers, possibly enabling presynaptic forms of synaptic plasticity (Ahmed and Siegelbaum 2009). Overall biophysical measurements suggest that for spontaneous release at inhibitory synapses, the calcium transient triggering release will be much briefer with a possibly higher peak [Ca2+]i, depending on the degree of domain overlap from neighboring VACCs. However, during evoked release a greater number of VACCs will open, because of the action potential, increasing the total terminal Ca2+ entry and stimulating exocytosis and synaptic transmission via interdependent mechanisms such as endocytosis, membrane potential, and buffering.

VACC-independent mechanisms impacting spontaneous release

Spontaneous release does not always require VACCs for release (Table 1). Spontaneous release in many brain regions is triggered by transient rises in [Ca2+]i from intracellular stores but does not result in multi-vesicular release. In hippocampal neurons, ryanodine reduced release of Ca2+ from stores and decreased spontaneous glutamate release (Emptage et al. 2001)- this pathway accounting for about 50% of basal excitatory spontaneous activity. However, in neocortical and hippocampal neurons basal activity was unaffected by BAPTA-AM (Abenavoli et al. 2002; Vyleta and Smith 2011) possibly indicating that the Ca2+ store-vesicle coupling was very tight or played a diminished role regulating basal spontaneous release in some neurons. The moderate variation in basal activity of spontaneous release reflects the random nature of the process (see Fig. 4a, g). However, episodic bursts of spontaneous activity are also frequently observed (see Fig 1d). One explanation is that spontaneous bursting may be a consequence of episodic release from Ca2+ stores, but the underlying mechanism of regulation and physiological role are unclear. Certainly, pharmacological release of Ca2+ has confirmed the feasibility of this idea. Release of Ca2+ from stores by caffeine increased spontaneous release of glutamate in hippocampal and neocortical neurons (Sharma and Vijayaraghavan 2003; Vyleta and Smith 2008). In addition at some synapses Ca2+ release from intracellular stores may have additional effects. Cerebellar interneurons receive large-amplitude mIPSCs (Llano et al. 2000) that are independent of VACC activity. These events are large because they result from simultaneous multi-vesicular events and appear to be triggered following release of Ca2+ via ryanodine receptors on presynaptic Ca2+ stores (Llano et al. 2000).

Another possible source for Ca2+ regulation of spontaneous release is the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger (NCX), which normally functions in removal of Ca2+ from nerve terminals (Nachshen et al. 1986; Sanchez-Armass and Blaustein 1987). [Ca2+]o could enhance spontaneous fusion by promoting reverse-mode NCX activity (Na+ efflux, Ca2+ influx) (Smith et al. 2012). If this is occurs, direct inhibition of NCX-mediated Ca2+ transport should attenuate the enhancement of spontaneous fusion by elevation of [Ca2+]o. KB-R7943 inhibits forward- and reverse-mode NCX currents, and spontaneous release of glutamate is significantly increased by KB-R7943 in neocortical cultures, consistent with the hypothesis that NCX can increase basal [Ca2+]i and spontaneous fusion through a forward transport mechanism (Kimura et al. 1999; Smith et al. 2012; Vyleta and Smith 2011; Watano et al. 1996).

G protein-coupled receptors mediate Ca2+ dependence of spontaneous release

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) may also mediate a portion of the Ca2+ dependence of spontaneous vesicle fusion. One candidate GPCR, the Ca2+-sensing receptor (CaSR), is activated by increases in [Ca2+]o and [Mg2+]o and is expressed at presynaptic terminals in the central nervous system (Brown et al. 1993; Chen et al. 2010). Cinacalcet, an allosteric CaSR agonist, increases miniature frequency at both excitatory and inhibitory neocortical synapses (Smith et al. 2012; Vyleta and Smith 2011). Gd3+ and Mg2+—both of which are CaSR agonists and VACC blockers—increase spontaneous release of glutamate (Vyleta and Smith 2011). In addition, null mutant CaSR neocortical cultured neurons have a lower mEPSC frequency (Smith et al. 2012; Vyleta and Smith 2011) and CaSR accounts for ~30% of basal spontaneous glutamate release (Smith et al. 2012). Some metabotropic glutamate receptors, such as mGluR1, are activated by external Ca2+ as well as glutamate (Kubo et al. 1998) and when stimulated increase mEPSC frequency (Schoppa and Westbrook 1997). Consequently, activation of mGluR1 by changes in [Ca2+]o is another pathway that may contribute to basal [Ca2+]o-dependent mEPSC frequency. Several other GPCRs modulate spontaneous release (Ramirez and Kavalali 2011). Exogenous phorbol esters and DAG—which activate or participate in a protein kinase C-dependent pathway—augment both spontaneous and evoked release possibly through allosteric modification of Ca2+ sensing release machinery or VACCs (Lou et al. 2005; Malenka et al. 1986; Ramirez and Kavalali 2011; Swartz et al. 1993; Virmani et al. 2005; Waters and Smith 2000). Activation of Group II metabotropic glutamate receptors in cerebellar brain slices reduce spontaneous release of GABA onto Purkinje cells (Glitsch 2006). Likewise, activation of GABAB or cannabinoid receptors reduces spontaneous release at cerebellar synapses (Dittman and Regehr 1996; Yamasaki et al. 2006). Cannabinoid receptor activation also increases spontaneous release in the dentate gyrus, showing that there is brain region-specific variability in these regulatory mechanisms (Hofmann et al. 2011).

Divergence in synaptic vesicle release machinery

At first glance, the striking difference in Ca2+ sensitivity of evoked and spontaneous release appears to support the idea that evoked and spontaneous release mechanisms are distinct. A more parsimonious hypothesis postulated an allosteric model for vesicle fusion and attributed the low Ca2+ dependence of spontaneous release to a Ca2+ independent pathway (Lou et al. 2005). This is consistent with the idea that spontaneous and evoked release utilize the same complex of proteins to trigger synaptic vesicle fusion (Delgado-Martinez et al. 2007; Hu et al. 2002; Rickman and Davletov 2003; Schoch et al. 2001; Verhage et al. 2000; Xu et al. 2009). The vesicle and target synaptic membrane contain a variety of proteins that participate in and regulate exocytosis (Takamori et al. 2006; Weingarten et al. 2014; Wilhelm et al. 2014). However, some of these vesicle associated proteins have been shown to participate in trafficking of vesicles into segregated pools, indicating that vesicles may have distinct molecular identities related to their function as well as contribute to differences in Ca2+-dependence (Crawford and Kavalali 2015; Deitcher et al. 1998; Hua et al. 1998; Tafoya et al. 2006; Washbourne et al. 2002; Yang et al. 2002). Here we discuss the molecular mechanisms that mediate the [Ca2+]i-dependence of release (or lack thereof), and the controversies in the field as well as likely causes for these discrepancies.

One of the major sources of controversy is whether the Ca2+ sensors that catalyze vesicle fusion differ for spontaneous and evoked release. Synaptotagmins 1–17 all sense Ca2+ via their two C-terminal C2 domains and were tested to determine their role in Ca2+-dependent exocytosis (Fernández-Chacón et al. 2001; Pang et al. 2006). Loss of either synaptotagmin 1, 2, or 9 impairs activity-dependent transmission but increases spontaneous or asynchronous release, leading to a hypothesis that synaptotagmins may have a clamping function which prevents unwanted release (Geppert et al. 1994; Liu et al. 2009; Maximov and Südhof 2005; Nishiki and Augustine 2004; Sun et al. 2007b; Wierda and Sorensen 2014). Additionally, deletion of synaptotagmin 7 in both excitatory and inhibitory neurons in hippocampus and retina reduced asynchronous release induced by high-frequency stimulation, suggesting synaptotagmin 7 may be a “slow” Ca2+ sensor working in conjunction with synaptotagmins 1, 2, and 9 which mediate faster forms of release (Bacaj et al. 2013; Luo et al. 2015). Yet, recent work in hippocampus show that synaptotagmin 7 is involved in Ca2+-dependent vesicle pool replenishment and not release (Liu et al. 2014). Other studies have shown that synaptotagmin does function as a Ca2+ sensor for spontaneous release, but deletion of synaptotagmin allows for activation of a second Ca2+ sensor that has an apparent higher Ca2+ affinity (Xu et al. 2009). Differences may arise from the use of knockout mouse models and genetic compensation, as well as differences between release mechanisms across neuronal-cell types. These findings are evidence of divergence in release mechanisms for synaptotagmin proteins, implying that spontaneous and activity dependent modes of release may be regulated independently by the cell and be controlled via different release machineries.

Vesicle fusion is not the only part of the process that is dependent on [Ca2+]i. Vesicle priming--or preparation of a docked vesicle for fusion with the plasma membrane--pool-refilling, and endocytosis are also Ca2+ dependent processes (Burgoyne and Morgan 1995; Smith et al. 1998; Sudhof 2004; Voets 2000; Wang and Kaczmarek 1998). Double C2 domain (DOC2) family proteins are another group of Ca2+ binding proteins that are likely candidates to participate in the Ca2+ dependence of secretion. DOC2 proteins are suggested to regulate synaptic vesicle docking by regulating SNARE protein interactions, but the precise role of DOC2 proteins in docking, priming, and fusion is incomplete (Friedrich et al. 2010; Verhage et al. 1997). The DOC2 family consists of DOC2A, B, and C. Interestingly, while DOC2A has been suggested to have a role in facilitating and sustaining evoked release (Hori et al. 1999; Mochida et al. 1998; Sakaguchi et al. 1999), DOC2B has been shown to selectively maintain spontaneous release, though there is disagreement about whether DOC2 proteins function in a Ca2+-dependent or-independent manner (Groffen et al. 2010; Pang et al. 2011).

Complexin—another SNARE complex-binding protein—activates Ca2+-dependent exocytosis (Brose 2008; McMahon et al. 1995). Genetic ablation studies have all shown that loss of complexin reduces evoked release (Chang et al. 2015; Giraudo et al. 2006; Huntwork and Littleton 2007; Lou et al. 2008; Martin et al. 2011; Maximov et al. 2009; Reim et al. 2001; Strenzke et al. 2009; Xue et al. 2010). A number of studies of complexin null mutations in Drosophila and mouse neurons show marked increases in spontaneous release, suggesting that complexins—similar to, but independent of synaptotagmin—also acts as a clamp to prevent spontaneous vesicle fusion (Giraudo et al. 2006; Huntwork and Littleton 2007; Lai et al. 2014; Maximov et al. 2009; Yang et al. 2013). Other studies in other organisms have shown the opposite effect and it it is suggested that these differences result from the existence of distinct protein domains which confer the ability to either facilitate or clamp release under different conditions (Chang et al. 2015; Martin et al. 2011; Strenzke et al. 2009; Trimbuch and Rosenmund 2016; Xue et al. 2008). This would allow for a conservation of release machinery for spontaneous and evoked release, while allowing for independent and precise regulation. Taken together, the observed actions of complexins, synaptotagmins, and DOC2 proteins suggest that there may be important mechanisms that selectively regulate the probability of spontaneous vesicle fusion events in a Ca2+ dependent mechanism.

Distinct synaptic machinery for spontaneous release at excitatory and inhibitory terminals was raised as a possible mechanism to explain differential regulation by VACCs at these synapses (see above). Early studies indicated that at small neocortical terminals the calcium dependence of spontaneous release of GABA and glutamate were affected similarly by genetic deletion of synaptotagmin 1 (Xu et al. 2009). In both types of synapse there was increased basal spontaneous activity, increased maximal spontaneous activity, and increased sensitivity to [Ca2+]o with synaptotagmin 1 deletion, and it was proposed that the synapses contained a second Ca2+ sensor that triggered spontaneous release and was clamped by synaptotagmin 1 (Xu et al. 2009). If the second Ca2+ sensor were different at excitatory and inhibitory terminals this could explain the differential regulation by VACCs. Evidence for the differential expression of synaptotagmin 1 and 2 at excitatory and inhibitory cerebellar synapses respectively has emerged recently (Chen et al. 2017). It remains uncertain if this underlies differential regulation of spontaneous release by VACCs, but interest in this possibility has increased as synaptotagmin 2 deletion substantially reduced evoked and enhanced spontaneous release at cerebellar inhibitory synapses (Chen et al. 2017). Furthermore, at inhibitory synapses in the brainstem, spontaneous release was increased by synaptotagmin 2 deletion but evoked release was unaffected unless synaptotagmin 1 and 2 were both deleted (Bouhours et al. 2017). It seems likely that greater understanding of the identity and roles of the intracellular Ca2+ sensors at inhibitory and excitatory synapses will foster understanding of the mechanisms of differential regulation of spontaneous release at these synapses.

CONCLUSIONS

Evoked neurotransmitter release is regulated by both [Ca2+]o and [Ca2+]i and the VACC has a key role linking the two. However, during spontaneous release the regulatory role of the VACC varies at different synapses. In general, spontaneous release at inhibitory synapses is mainly regulated by Ca2+ entering through VACCs. This finding contrasts with the VACC-independence of spontaneous release at most excitatory synapses in the central nervous system. These differences in Ca2+ dependence for different modes of transmission and at different types of synapse reflect differences in the size and shape of the Ca2+ domain, number and type of channels involved, action by G-protein coupled receptors, and differences in Ca2+ binding release machinery. Further study is needed to determine the scope of these differences and the underlying mechanisms.

SIGNIFICANCE.

Presynaptic Ca2+ entry via voltage-activated Ca2+ channels (VACC) triggers action potential-evoked synaptic transmission. The role of VACCs and Ca2+ in regulation of spontaneous neurotransmitter release (which occurs in the absence of an action potential) remains a hot topic of discussion. Here we discuss how spontaneous release is regulated by both extracellular [Ca2+] and intracellular [Ca2+] via VACCs, pumps, intracellular stores, and the Ca2+ sensing G-protein coupled receptor. We also discuss the reported controversies in Ca2+ dependence of spontaneous release and the possible sources of heterogeneity for different release mechanisms and neuronal sub-types. We report that at inhibitory synapses, stochastic openings of VACCs trigger the majority of spontaneous release, whereas they do not affect spontaneous release at excitatory synapses. This pattern holds for large and small synapses in the central nervous system. These findings indicate fundamental differences of the Ca2+ dependence of spontaneous release mechanisms which need further study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants awarded by NIGMS (R01 GM097433) and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (BX002547) to SMS. In addition, CLW was supported by NHLBI (T32HL083808) and NINDS (1F31NS083309). We thank Caitlin Harrington-Smith for assistance with figures.

References

- Abenavoli A, Forti L, Bossi M, Bergamaschi A, Villa A, Malgaroli A. Multimodal quantal release at individual hippocampal synapses: evidence for no lateral inhibition. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2002;22(15):6336–6346. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06336.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed MS, Siegelbaum SA. Recruitment of N-Type Ca(2+) channels during LTP enhances low release efficacy of hippocampal CA1 perforant path synapses. Neuron. 2009;63(3):372–385. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreae LC, Fredj NB, Burrone J. Independent vesicle pools underlie different modes of release during neuronal development. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32(5):1867–1874. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5181-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustine GJ, Charlton MP. Calcium dependence of presynaptic calcium current and post-synaptic response at the squid giant synapse. J Physiol. 1986;381(1):619–640. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autry AE, Megumi A, Elena N, Na ES, Los MF, Peng-fei C, Kavalali ET, Monteggia LM. NMDA receptor blockade at rest triggers rapid behavioural antidepressant responses. Nature. 2011;475(7354):91–95. doi: 10.1038/nature10130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacaj T, Wu D, Yang X, Morishita W, Zhou P, Xu W, Malenka RC, Sudhof TC. Synaptotagmin-1 and synaptotagmin-7 trigger synchronous and asynchronous phases of neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 2013;80(4):947–959. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst JG, Sakmann B. Calcium current during a single action potential in a large presynaptic terminal of the rat brainstem. The Journal of physiology. 1998;506(Pt 1):143–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.143bx.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst JGG, Sakmann B. Calcium influx and transmitter release in a fast CNS synapse. Nature. 1996;383(6599):431–434. doi: 10.1038/383431a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhours B, Gjoni E, Kochubey O, Schneggenburger R. Synaptotagmin2 (Syt2) drives fast release redundantly with Syt1 at the output synapses of Parvalbumin-expressing inhibitory neurons. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2017 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3736-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd IA, Martin AR. Spontaneous subthreshold activity at mammalian neuromuscular junctions. J Physiol. 1956;132(1):61–73. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1956.sp005502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brose N. Altered complexin expression in psychiatric and neurological disorders: cause or consequence? Mol Cells. 2008;25(1):7–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EM, Gerardo G, Daniela R, Michael L, Robert B, Olga K, Adam S, Hediger MA, Jonathan L, Hebert SC. Cloning and characterization of an extracellular Ca2 -sensing receptor from bovine parathyroid. Nature. 1993;366(6455):575–580. doi: 10.1038/366575a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucurenciu I, Bischofberger J, Jonas P. A small number of open Ca2+ channels trigger transmitter release at a central GABAergic synapse. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(1):19–21. doi: 10.1038/nn.2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucurenciu I, Kulik A, Schwaller B, Frotscher M, Jonas P. Nanodomain coupling between Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ sensors promotes fast and efficient transmitter release at a cortical GABAergic synapse. Neuron. 2008;57(4):536–545. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne RD, Morgan A. Ca2+ and secretory-vesicle dynamics. Trends in neurosciences. 1995;18(4):191–196. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93900-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AG, Regehr WG. Quantal events shape cerebellar interneuron firing. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5(12):1309–1318. doi: 10.1038/nn970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S, Reim K, Pedersen M, Neher E, Brose N, Taschenberger H. Complexin stabilizes newly primed synaptic vesicles and prevents their premature fusion at the mouse calyx of held synapse. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2015;35(21):8272–8290. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4841-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Arai I, Satterfield R, Young SM, Jr, Jonas P. Synaptotagmin 2 Is the Fast Ca2+ Sensor at a Central Inhibitory Synapse. Cell Rep. 2017;18(3):723–736. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Wenyan C, Bergsman JB, Xiaohua W, Gawain G, Carol-Renée P, Daniel EA, Awumey EM, Philippe D, Dodd RH, Martial R, Smith SM. Presynaptic External Calcium Signaling Involves the Calcium-Sensing Receptor in Neocortical Nerve Terminals. PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8563. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow RH. Cadmium block of squid calcium currents. Macroscopic data and a kinetic model. J Gen Physiol. 1991;98(4):751–770. doi: 10.1085/jgp.98.4.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie JM, Chiu DN, Jahr CE. Ca2 -dependent enhancement of release by subthreshold somatic depolarization. Nat Neurosci. 2010;14(1):62–68. doi: 10.1038/nn.2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cork KM, Van Hook MJ, Thoreson WB. Mechanisms, pools, and sites of spontaneous vesicle release at synapses of rod and cone photoreceptors. The European journal of neuroscience. 2016;44(3):2015–2027. doi: 10.1111/ejn.13288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford DC, Kavalali ET. Molecular underpinnings of synaptic vesicle pool heterogeneity. Traffic. 2015;16(4):338–364. doi: 10.1111/tra.12262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J, Chen P, Tian H, Sun J. Spontaneous Vesicle Release Is Not Tightly Coupled to Voltage-Gated Calcium Channel-Mediated Ca2 Influx and Is Triggered by a Ca2 Sensor Other Than Synaptotagmin-2 at the Juvenile Mice Calyx of Held Synapses. Journal of Neuroscience. 2015;35(26):9632–9637. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0457-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deitcher DL, Ueda A, Stewart BA, Burgess RW, Kidokoro Y, Schwarz TL. Distinct requirements for evoked and spontaneous release of neurotransmitter are revealed by mutations in the Drosophila gene neuronal-synaptobrevin. J Neurosci. 1998;18(6):2028–2039. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-06-02028.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcour AH, Lipscombe D, Tsien RW. Multiple modes of N-type calcium channel activity distinguished by differences in gating kinetics. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1993;13(1):181–194. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-01-00181.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Martinez I, Nehring RB, Sorensen JB. Differential abilities of SNAP-25 homologs to support neuronal function. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007;27(35):9380–9391. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5092-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittman JS, Regehr WG. Contributions of calcium-dependent and calcium-independent mechanisms to presynaptic inhibition at a cerebellar synapse. J Neurosci. 1996;16(5):1623–1633. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01623.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge FA, Rahamimoff R. Co-operative action of calcium ions in transmitter release at the neuromuscular junction. J Physiol. 1967;193(2):419–432. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermann E, Bucurenciu I, Goswami SP, Jonas P. Nanodomain coupling between Ca2+ channels and sensors of exocytosis at fast mammalian synapses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;13(1):7–21. doi: 10.1038/nrn3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emptage NJ, Reid CA, Alan F. Calcium Stores in Hippocampal Synaptic Boutons Mediate Short-Term Plasticity, Store-Operated Ca2 Entry, and Spontaneous Transmitter Release. Neuron. 2001;29(1):197–208. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermolyuk YS, Alder FG, Henneberger C, Rusakov DA, Kullmann DM, Volynski KE. Independent regulation of basal neurotransmitter release efficacy by variable Ca(2)+ influx and bouton size at small central synapses. PLoS biology. 2012;10(9):e1001396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermolyuk YS, Alder FG, Surges R, Pavlov IY, Timofeeva Y, Kullmann DM, Volynski KE. Differential triggering of spontaneous glutamate release by P/Q-, N- and R-type Ca2+ channels. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(12):1754–1763. doi: 10.1038/nn.3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Chacón R, Königstorfer A, Gerber SH, García J, Matos MF, Stevens CF, Brose N, Rizo J, Rosenmund C, Südhof TC. Synaptotagmin I functions as a calcium regulator of release probability. Nature. 2001;410(6824):41–49. doi: 10.1038/35065004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich R, Yeheskel A, Ashery U. DOC2B, C2 domains, and calcium: A tale of intricate interactions. Molecular neurobiology. 2010;41(1):42–51. doi: 10.1007/s12035-009-8094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geppert M, Goda Y, Hammer RE, Li C, Rosahl TW, Stevens CF, Sudhof TC. Synaptotagmin I: a major Ca2+ sensor for transmitter release at a central synapse. Cell. 1994;79(4):717–727. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90556-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraudo CG, Eng WS, Melia TJ, Rothman JE. A clamping mechanism involved in SNARE-dependent exocytosis. Science. 2006;313(5787):676–680. doi: 10.1126/science.1129450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glitsch M. Selective Inhibition of Spontaneous But Not Ca2 -Dependent Release Machinery by Presynaptic Group II mGluRs in Rat Cerebellar Slices. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96(1):86–96. doi: 10.1152/jn.01282.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami SP, Bucurenciu I, Jonas P. Miniature IPSCs in Hippocampal Granule Cells Are Triggered by Voltage-Gated Ca2 Channels via Microdomain Coupling. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(41):14294–14304. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6104-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graydon CW, Cho S, Li G-L, Kachar B, von Gersdorff H. Sharp Ca2+ Nanodomains beneath the Ribbon Promote Highly Synchronous Multivesicular Release at Hair Cell Synapses. J Neurosci. 2011;31(46):16637–16650. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1866-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groffen AJ, Martens S, Arazola RD, Cornelisse LN, Lozovaya N, de Jong APH, Goriounova NA, Habets RLP, Takai Y, Borst JG, Brose N, McMahon HT, Verhage M. Doc2b Is a High-Affinity Ca2 Sensor for Spontaneous Neurotransmitter Release. Science. 2010;327(5973):1614–1618. doi: 10.1126/science.1183765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helton TD, Xu W, Lipscombe D. Neuronal L-Type Calcium Channels Open Quickly and Are Inhibited Slowly. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25(44):10247–10251. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1089-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkle PM, Shanshala ED, 2nd, Nelson EJ. Measurement of intracellular cadmium with fluorescent dyes. Further evidence for the role of calcium channels in cadmium uptake. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1992;267(35):25553–25559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann ME, Chinki B, Frazier CJ. Cannabinoid receptor agonists potentiate action potential-independent release of GABA in the dentate gyrus through a CB1 receptor-independent mechanism. J Physiol. 2011;589(15):3801–3821. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.211482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppa MB, Gouzer G, Armbruster M, Ryan TA. Control and plasticity of the presynaptic action potential waveform at small CNS nerve terminals. Neuron. 2014;84(4):778–789. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori T, Takai Y, Takahashi T. Presynaptic mechanism for phorbol ester-induced synaptic potentiation. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1999;19(17):7262–7267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07262.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu K, Carroll J, Rickman C, Davletov B. Action of complexin on SNARE complex. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277(44):41652–41656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205044200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua J, Liu L, Li G. Optical interconnection for neural networks by use of a self-imaging function. Applied optics. 1998;37(2):308–314. doi: 10.1364/ao.37.000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard JI. The effect of calcium and magnesium on the spontaneous release of transmitter from mammalian motor nerve endings. J Physiol. 1961;159(3):507–517. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1961.sp006824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard JI, Jones SF, Landau EM. On the mechanism by which calcium and magnesium affect the spontaneous release of transmitter from mammalian motor nerve terminals. J Physiol. 1968;194(2):355–380. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntwork S, Littleton JT. A complexin fusion clamp regulates spontaneous neurotransmitter release and synaptic growth. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(10):1235–1237. doi: 10.1038/nn1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson I, Spence MTZ. The Molecular Probes Handbook: a Guide to Fluorescent Probes and Labeling Technolgies. Carlsbad, CA: Life Technologies Corp; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kavalali ET, Plummer MR. Selective potentiation of a novel calcium channel in rat hippocampal neurones. The Journal of physiology. 1994;480(Pt 3):475–484. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura J, Junko K, Tomokazu W, Masanori K, Eiichi S, Junichi Y. Direction-independent block of bi-directional Na/Ca2 exchange current by KB-R7943 in guinea-pig cardiac myocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128(5):969–974. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King JD, Jr, Meriney SD. Proportion of N-type calcium current activated by action potential stimuli. Journal of neurophysiology. 2005;94(6):3762–3770. doi: 10.1152/jn.01289.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo Y, Miyashita T, Murata Y. Structural basis for a Ca2+-sensing function of the metabotropic glutamate receptors. Science. 1998;279(5357):1722–1725. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5357.1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y, Diao J, Cipriano DJ, Zhang Y, Pfuetzner RA, Padolina MS, Brunger AT. Complexin inhibits spontaneous release and synchronizes Ca2+-triggered synaptic vesicle fusion by distinct mechanisms. eLife. 2014;3:e03756. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansman JB, Hess P, Tsien RW. Blockade of current through single calcium channels by Cd2+, Mg2+, and Ca2+. Voltage and concentration dependence of calcium entry into the pore. The Journal of general physiology. 1986;88(3):321–347. doi: 10.1085/jgp.88.3.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G-L, Keen E, Andor-Ardó D, Hudspeth AJ, von Gersdorff H. The unitary event underlying multiquantal EPSCs at a hair cell’s ribbon synapse. J Neurosci. 2009;29(23):7558–7568. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0514-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Bischofberger J, Jonas P. Differential gating and recruitment of P/Q-, N-, and R-type Ca2+ channels in hippocampal mossy fiber boutons. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007;27(49):13420–13429. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1709-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu DD, Lu JM, Zhao QR, Hu C, Mei YA. Growth differentiation factor-15 promotes glutamate release in medial prefrontal cortex of mice through upregulation of T-type calcium channels. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28653. doi: 10.1038/srep28653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Bai H, Hui E, Yang L, Evans CS, Wang Z, Kwon SE, Chapman ER. Synaptotagmin 7 functions as a Ca(2+)-sensor for synaptic vesicle replenishment. eLife. 2014:3. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Dean C, Arthur CP, Dong M, Chapman ER. Autapses and networks of hippocampal neurons exhibit distinct synaptic transmission phenotypes in the absence of synaptotagmin I. J Neurosci. 2009;29(23):7395–7403. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1341-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano I, González J, Caputo C, Lai FA, Blayney LM, Tan YP, Marty A. Presynaptic calcium stores underlie large-amplitude miniature IPSCs and spontaneous calcium transients. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3(12):1256–1265. doi: 10.1038/81781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopin KV, Thevenod F, Page JC, Jones SW. Cd(2)(+) block and permeation of CaV3.1 (alpha1G) T-type calcium channels: candidate mechanism for Cd(2)(+) influx. Molecular pharmacology. 2012;82(6):1183–1193. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.080176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losavio A, Muchnik S. Spontaneous acetylcholine release in mammalian neuromuscular junctions. The American journal of physiology. 1997;273(6 Pt 1):C1835–1841. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.6.C1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losavio A, Muchnik S. Role of L-type and N-type Voltage-dependent Calcium Channels (VDCCs) on Spontaneous Acetylcholine Release at the Mammalian Neuromuscular Junction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1998;841(1):636–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou X, Korogod N, Brose N, Schneggenburger R. Phorbol esters modulate spontaneous and Ca2+-evoked transmitter release via acting on both Munc13 and protein kinase C. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28(33):8257–8267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0550-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou X, Scheuss V, Schneggenburger R. Allosteric modulation of the presynaptic Ca2+ sensor for vesicle fusion. Nature. 2005;435(7041):497–501. doi: 10.1038/nature03568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo F, Bacaj T, Sudhof TC. Synaptotagmin-7 Is Essential for Ca2+-Triggered Delayed Asynchronous Release But Not for Ca2+-Dependent Vesicle Priming in Retinal Ribbon Synapses. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2015;35(31):11024–11033. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0759-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo F, Dittrich M, Stiles JR, Meriney SD. Single-pixel optical fluctuation analysis of calcium channel function in active zones of motor nerve terminals. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2011;31(31):11268–11281. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1394-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luvisetto S, Fellin T, Spagnolo M, Hivert B, Brust PF, Harpold MM, Stauderman KA, Williams ME, Pietrobon D. Modal gating of human CaV2.1 (P/Q-type) calcium channels: I. The slow and the fast gating modes and their modulation by beta subunits. The Journal of general physiology. 2004;124(5):445–461. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenka RC, Madison DV, Nicoll RA. Potentiation of synaptic transmission in the hippocampus by phorbol esters. Nature. 1986;321(6066):175–177. doi: 10.1038/321175a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hu Z, Fenz KM, Fernandez J, Dittman JS. Complexin has opposite effects on two modes of synaptic vesicle fusion. Current biology: CB. 2011;21(2):97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews G, Wickelgren WO. On the effect of calcium on the frequency of miniature end-plate potentials at the frog neuromuscular junction. J Physiol. 1977;266(1):91–101. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matveev V, Victor M, Richard B, Arthur S. Calcium cooperativity of exocytosis as a measure of Ca2 channel domain overlap. Brain Res. 2011;1398:126–138. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maximov A, Südhof TC. Autonomous function of synaptotagmin 1 in triggering synchronous release independent of asynchronous release. Neuron. 2005;48(4):547–554. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maximov A, Tang J, Yang X, Pang ZP, Sudhof TC. Complexin controls the force transfer from SNARE complexes to membranes in fusion. Science. 2009;323(5913):516–521. doi: 10.1126/science.1166505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney RA, Capogna M, Dürr R, Gähwiler BH, Thompson SM. Miniature synaptic events maintain dendritic spines via AMPA receptor activation. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2(1):44–49. doi: 10.1038/4548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon HT, Missler M, Li C, Südhof TC. Complexins: cytosolic proteins that regulate SNAP receptor function. Cell. 1995;83(1):111–119. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinrenken CJ, Borst JGG, Sakmann B. Calcium secretion coupling at calyx of Held governed by nonuniform channel-vesicle topography. J Neurosci. 2002;22(5):1648–1667. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01648.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz IM, Sabatini BL, Regehr WG. Calcium control of transmitter release at a cerebellar synapse. Neuron. 1995;15(3):675–688. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochida S, Orita S, Sakaguchi G, Sasaki T, Takai Y. Role of the Doc2 alpha-Munc13-1 interaction in the neurotransmitter release process. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(19):11418–11422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachshen DA, Sanchez-Armass S, Weinstein AM. The regulation of cytosolic calcium in rat brain synaptosomes by sodium-dependent calcium efflux. J Physiol. 1986;381:17–28. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Harada H, Kamasawa N, Matsui K, Rothman JS, Shigemoto R, Silver RA, DiGregorio DA, Takahashi T. Nanoscale distribution of presynaptic Ca(2+) channels and its impact on vesicular release during development. Neuron. 2015;85(1):145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navedo MF, Cheng EP, Yuan C, Votaw S, Molkentin JD, Scott JD, Santana LF. Increased Coupled Gating of L-Type Ca2+ Channels During Hypertension and Timothy Syndrome. Circulation Research. 2010;106(4):748–756. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.213363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navedo MF, Nieves-Cintrón M, Amberg GC, Yuan C, Votaw VS, Lederer WJ, McKnight GS, Santana LF. AKAP150 Is Required for Stuttering Persistent Ca2+ Sparklets and Angiotensin II–Induced Hypertension. Circulation Research. 2008;102(2):e1–e11. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.167809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiki T, Augustine GJ. Synaptotagmin I synchronizes transmitter release in mouse hippocampal neurons. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2004;24(27):6127–6132. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1563-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang ZP, Melicoff E, Padgett D, Liu Y, Teich AF, Dickey BF, Lin W, Adachi R, Südhof TC. Synaptotagmin-2 is essential for survival and contributes to Ca2+ triggering of neurotransmitter release in central and neuromuscular synapses. J Neurosci. 2006;26(52):13493–13504. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3519-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang ZP, Taulant B, Xiaofei Y, Peng Z, Wei X, Südhof TC. Doc2 Supports Spontaneous Synaptic Transmission by a Ca2 -Independent Mechanism. Neuron. 2011;70(2):244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez DMO, Kavalali ET. Differential regulation of spontaneous and evoked neurotransmitter release at central synapses. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2011;21(2):275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reim K, Mansour M, Varoqueaux F, McMahon HT, Sudhof TC, Brose N, Rosenmund C. Complexins regulate a late step in Ca2+-dependent neurotransmitter release. Cell. 2001;104(1):71–81. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00192-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickman C, Davletov B. Mechanism of calcium-independent synaptotagmin binding to target SNAREs. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278(8):5501–5504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200692200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi G, Manabe T, Kobayashi K, Orita S, Sasaki T, Naito A, Maeda M, Igarashi H, Katsuura G, Nishioka H, Mizoguchi A, Itohara S, Takahashi T, Takai Y. Doc2alpha is an activity-dependent modulator of excitatory synaptic transmission. The European journal of neuroscience. 1999;11(12):4262–4268. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Armass S, Blaustein MP. Role of sodium-calcium exchange in regulation of intracellular calcium in nerve terminals. Am J Physiol. 1987;252(6 Pt 1):C595–603. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.252.6.C595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanziani M, Capogna M, Gahwiler BH, Thompson SM. Presynaptic inhibition of miniature excitatory synaptic currents by baclofen and adenosine in the hippocampus. Neuron. 1992;9(5):919–927. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoch S, Deak F, Konigstorfer A, Mozhayeva M, Sara Y, Sudhof TC, Kavalali ET. SNARE function analyzed in synaptobrevin/VAMP knockout mice. Science. 2001;294(5544):1117–1122. doi: 10.1126/science.1064335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppa NE, Westbrook GL. Modulati one of mEPSCs in Olfactory Bulb Mitral Cells by Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors. Journal of neurophysiology. 1997;78(3):1468–1475. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.3.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahrezaei V, Cao A, Delaney KR. Ca2+ from one or two channels controls fusion of a single vesicle at the frog neuromuscular junction. J Neurosci. 2006;26(51):13240–13249. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1418-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma G, Vijayaraghavan S. Modulation of Presynaptic Store Calcium Induces Release of Glutamate and Postsynaptic Firing. Neuron. 2003;38(6):929–939. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00322-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigworth FJ, Sine SM. Data transformations for improved display and fitting of single-channel dwell time histograms. Biophys J. 1987;52(6):1047–1054. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83298-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Moser T, Xu T, Neher E. Cytosolic Ca2+ acts by two separate pathways to modulate the supply of release-competent vesicles in chromaffin cells. Neuron. 1998;20(6):1243–1253. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80504-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Chen W, Vyleta NP, Williams C, Lee C-H, Phillips C, Andresen MC. Calcium regulation of spontaneous and asynchronous neurotransmitter release. Cell calcium. 2012;52(3–4):226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley EF. Single calcium channels and acetylcholine release at a presynaptic nerve terminal. Neuron. 1993;11(6):1007–1011. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90214-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley EF. The calcium channel and the organization of the presynaptic transmitter release face. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20(9):404–409. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strenzke N, Chanda S, Kopp-Scheinpflug C, Khimich D, Reim K, Bulankina AV, Neef A, Wolf F, Brose N, Xu-Friedman MA, Moser T. Complexin-I is required for high-fidelity transmission at the endbulb of Held auditory synapse. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29(25):7991–8004. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0632-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhof TC. The synaptic vesicle cycle. Annual review of neuroscience. 2004;27:509–547. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Jianyuan S, Pang ZP, Dengkui Q, Fahim AT, Roberto A, Südhof TC. A dual-Ca2 -sensor model for neurotransmitter release in a central synapse. Nature. 2007a;450(7170):676–682. doi: 10.1038/nature06308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Pang ZP, Qin D, Fahim AT, Adachi R, Sudhof TC. A dual-Ca2+-sensor model for neurotransmitter release in a central synapse. Nature. 2007b;450(7170):676–682. doi: 10.1038/nature06308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz KJ, Andrew M, Bean BP, Lovinger DM. Protein kinase C modulates glutamate receptor inhibition of Ca2 channels and synaptic transmission. Nature. 1993;361(6408):165–168. doi: 10.1038/361165a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tafoya LC, Mameli M, Miyashita T, Guzowski JF, Valenzuela CF, Wilson MC. Expression and function of SNAP-25 as a universal SNARE component in GABAergic neurons. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2006;26(30):7826–7838. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1866-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamori S, Shigeo T, Matthew H, Katinka S, Lemke EA, Mads G, Dietmar R, Henning U, Stephan S, Britta B, Philippe R, Müller SA, Burkhard R, Frauke G, Hub JS, De Groot BL, Gottfried M, Yoshinori M, Jürgen K, Helmut G, John H, Felix W, Reinhard J. Molecular Anatomy of a Trafficking Organelle. Cell. 2006;127(4):831–846. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapani JG, Nicolson T. Mechanism of Spontaneous Activity in Afferent Neurons of the Zebrafish Lateral-Line Organ. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31(5):1614–1623. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3369-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimbuch T, Rosenmund C. Should I stop or should I go? The role of complexin in neurotransmitter release. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17(2):118–125. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2015.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsintsadze T, Williams CL, Weingarten D, von Gersdorff H, Smith SM. Distinct Actions of Voltage-activated Ca2+ Channel Block on Spontaneous Release at Excitatory and Inhibitory Central Synapses. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2017 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3488-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhage M, de Vries KJ, Roshol H, Burbach JP, Gispen WH, Sudhof TC. DOC2 proteins in rat brain: complementary distribution and proposed function as vesicular adapter proteins in early stages of secretion. Neuron. 1997;18(3):453–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhage M, Maia AS, Plomp JJ, Brussaard AB, Heeroma JH, Vermeer H, Toonen RF, Hammer RE, van den Berg TK, Missler M, Geuze HJ, Sudhof TC. Synaptic assembly of the brain in the absence of neurotransmitter secretion. Science. 2000;287(5454):864–869. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5454.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virmani T, Ertunc M, Sara Y, Mozhayeva M, Kavalali ET. Phorbol esters target the activity-dependent recycling pool and spare spontaneous vesicle recycling. J Neurosci. 2005;25(47):10922–10929. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3766-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voets T. Dissection of three Ca2+-dependent steps leading to secretion in chromaffin cells from mouse adrenal slices. Neuron. 2000;28(2):537–545. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyleta NP, Smith SM. Fast Inhibition of Glutamate-Activated Currents by Caffeine. PLoS One. 2008;3(9):e3155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyleta NP, Smith SM. Spontaneous Glutamate Release Is Independent of Calcium Influx and Tonically Activated by the Calcium-Sensing Receptor. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31(12):4593–4606. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6398-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LY, Kaczmarek LK. High-frequency firing helps replenish the readily releasable pool of synaptic vesicles. Nature. 1998;394(6691):384–388. doi: 10.1038/28645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washbourne P, Thompson PM, Carta M, Costa ET, Mathews JR, Lopez-Bendito G, Molnar Z, Becher MW, Valenzuela CF, Partridge LD, Wilson MC. Genetic ablation of the t-SNARE SNAP-25 distinguishes mechanisms of neuroexocytosis. Nature neuroscience. 2002;5(1):19–26. doi: 10.1038/nn783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watano T, Tomokazu W, Junko K, Tominori M, Hironori N. A novel antagonist, No. 7943, of the Na/Ca2 exchange current in guinea-pig cardiac ventricular cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;119(3):555–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15708.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters J, Smith SJ. Phorbol esters potentiate evoked and spontaneous release by different presynaptic mechanisms. J Neurosci. 2000;20(21):7863–7870. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-07863.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]