Abstract

Background

Comorbid anxiety disorders have been considered a risk factor for suicidal behavior in patients with mood disorders, although results are controversial. The aim of this two-year prospective study was to determine if lifetime and current comorbid anxiety disorders at baseline were risk factors for suicide attempts during the two-year follow-up.

Methods

We evaluated 667 patients with mood disorders (504 with major depression and 167 with bipolar disorder) divided in two groups: those with lifetime comorbid anxiety disorders (n=229) and those without (n=438). Assessments were performed at baseline and at 3, 12, and 24 months. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and log-rank test were used to evaluate the relationship between anxiety disorders and suicide attempts. Cox proportional hazard regression was performed to investigate clinical and demographic variables that were associated with suicide attempts during follow-up.

Results

Of the initial sample of 667 patients, 480 had all three follow-up interviews. During the follow-up, 63 patients (13.1%) attempted suicide at least once. There was no significant difference in survival curves for patients with and without comorbid anxiety disorders (log-rank test= 0.269; p=0.604). Female gender (HR=3.66, p=0.001), previous suicide attempts (HR=3.27, p=0.001) and higher scores in the Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (HR= 1.05, p≤0.001) were associated with future suicide attempts.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that comorbid anxiety disorders were not risk factors for suicide attempts. Further studies were needed to determine the role of anxiety disorders as risk factors for suicide attempts.

Keywords: Comorbidity, Anxiety, Bipolar, Major Depression, Suicide, Suicide attempts

1. Introduction

Suicidal behavior is highly prevalent among patients with mood disorders [1]. The rate of suicide in such patients can be as high as 15–20% [2]. Suicide attempts are also prevalent in this population, with studies showing that up to 50% of patients with bipolar disorder (BD) and 30–40% of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) have lifetime history of suicide attempts [3,4,5]. Bipolar disorder and MDD share certain risk factors for suicide attempts, such as previous suicide attempts, greater severity of depression, comorbidity with alcohol or substance use, and comorbidity with anxiety disorders [6,7,8]

Anxiety disorders have been linked to suicidal behavior in the general population and in individuals with other psychiatric disorders. In a recent meta-analysis [9], patients with anxiety disorders were more likely to report suicidal ideation (OR: 2.89, 95% CI: 2.09–4.00), to have attempted suicide (OR: 2.47, 95% CI: 1.96–3.10), and to have died by suicide (OR: 3.34, 95% CI: 2.13–5.25) in comparison with patients without anxiety disorders, even after adjusting for comorbid depression.

There are few prospective studies investigating the role of lifetime comorbid anxiety disorders in future suicide attempts. These studies have produced conflicting results. A prospective study with a 3-year follow-up period, showed that the risk of suicide attempt was four times greater among patients with anxiety disorders and comorbid mood disorders than among those with anxiety disorders only (OR: 4.15, 95% CI: 1.34–12.9) and among those with mood disorders only (OR: 2.44, 95% CI: 0.709–7.55) [10]. Other prospective studies have also shown that suicide attempts and suicide ideation during follow-up are more common among BD and MDD patients with comorbid anxiety disorders than among those without [11,12]. In a three-year follow up study of patients with MDD, anxiety disorders were associated with suicide attempts (OR 2.31 CI=1.19–4.47, p <0.005) [11]. In another three-year follow-up study with patients with bipolar disorders there was an association between comorbid anxiety lifetime and suicide ideation (OR 1.66 CI=1.07–2.57, p=0.02). Interestingly in this study future attempts were not associated with comorbid anxiety (OR 1.56 CI= 0.74–3.30, p= 0.2) [12].

In another prospective study with a two-year follow-up involving MDD and BD patients, comorbidity with anxiety disorders was not a risk factor for suicide ideation and attempts [13], a finding that was replicated by other prospective studies with mood disorders patients [14,15]. Thus, the role of comorbidity with anxiety disorders and its relationship to suicide attempts in individuals with mood disorders remains unclear.

Anxiety symptoms are common in patients with mood disorders, even in those without a diagnosis of an anxiety disorder [16,17]. Recent studies have shown that anxiety symptoms (nervousness, uneasiness and anxiety) and self-reported anxiety can predict suicidal ideation and suicide attempts [18]. However, some studies have shown that anxiety symptoms have a protective effect against suicidal behavior in patients with mood disorders or MDD [19,20]. Therefore, the nature of the relationship between anxiety symptoms and suicide attempts is not conclusive.

To date, there have been few studies involving well-characterized, large samples of patients with mood disorders that investigated comorbidity with anxiety disorders as a risk factor for suicide attempts. This topic has fundamental clinical implications, as anxiety disorders are highly comorbid with mood disorders and mood disorders confers the highest risk for suicide attempts among psychiatric disorders [1]. The primary aim of this prospective study was to evaluate the risk for suicide attempts among patients with mood disorders, with and without comorbid anxiety disorders at baseline. We hypothesized that the patients with comorbid anxiety disorders would make more suicide attempts during follow-up than would those without such comorbidity. A secondary and exploratory aim was to determine whether baseline anxiety symptoms were associated with suicide attempts during follow-up.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Patients and procedures

We evaluated 667 patients who volunteered for studies of mood disorders and suicide behavior between January-1990 and July-2013, from two sites: New York, NY (New York State Psychiatric Institute, Columbia University) and Pittsburgh, PA (Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic) The inclusion criteria were: age between 18 and 70 years; diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder (any type) or Major Depressive Disorder according to Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised, and Fourth Edition Axis I disorders, patient edition (SCID-I) and signed a written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were current substance or alcohol abuse or dependence according to SCID-I, pregnancy and presence of neurological or unstable medical diseases (eg a patient with well controlled hypertension or diabetes was included). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute at Columbia University and Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic.

Trained research assessors with at least master’s degree in psychology or psychiatric nurses performed all the interviews, and all diagnoses were confirmed including all available data, by consensus, by senior research psychologists and psychiatrists. At baseline, all patients were diagnosed with the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised, and Fourth Edition Axis I disorders, patient edition (SCID-I). Of those, 161 (24.4%) were diagnosed with BD-I, BD-II, or BD not otherwise specified (BD-NOS) and 506 (75.6%) with MDD. In patients with BD, 122 were current depressed at baseline, 2 were in manic episode and one was in a mixed episode. In the MDD subgroup, 434 patients were currently depressed. Manic symptoms at baseline were measured using the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) and the mean score ± SD was 4.08 (±5.78).

Depressive symptoms were rated using the Beck Depression Inventory (self report scale with 21 items with scores between 0 to 63, with cronbach’s alpha of 0.86) [21] and the 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D-24; with scores between 0 and 70 and a cronbach’s alpha of 0.92) [22]. Anxiety symptoms were evaluating by using the following HAM-D-24 item scores: agitation, psychic anxiety, somatic anxiety, and hypochondriasis. Hopelessness was rated with the Beck Hopelessness Scale (self-report instrument with 20 questions and scores between 0–20, cronbach’s alpha of 0.88) [23]. Lifetime aggression and hostility were rated with the Brown–Goodwin Aggression Scale (11 items, with scores between 22 and 44, cronbach’s alpha 0.88) [24] and the Buss–Durkee Hostility Inventory (self-report scale for with 75 items with “true or false” answers and cronbach’s alpha of 0.74) [25]. Impulsivity was rated with the Barratt Impulsivity Scale (30 questions with scores between 30–120 and cronbach’s alpha of 0.83) [26].

A suicide attempt was defined as a self-destructive act carried out with at least some intent to end one’s life. The Scale for Suicide Ideation (scale with 19 items to evaluate the severity of suicidal ideation with scores between 0–38 and cronbach’s alpha of 0.83) [27] assessed suicide ideation at baseline. All this scales are widely used, validated and reliable measures.

In the follow-up assessments, presence of suicide attempts was evaluated at 3, 12 and 24 months by using the Columbia Suicide History Form (semi-structured interview that evaluates the presence, date, methods and lethality of each attempt. In this study we used only the presence or absence of attempts) [28].

2.2. Statistical analysis

Patients were divided in two groups according to the presence or absence of lifetime comorbid anxiety disorders. In patients with and without lifetime comorbid anxiety disorders at baseline, categorical and continuous variables were compared using chisquare tests and t-tests as appropriate.

Given that anxiety disorders tend to cluster together and are highly comorbid with each other, we initially examined the effect that anxiety disorders as a group had on the risk for future suicide attempts. In sensitivity analyses, we further examined the effect of each anxiety disorder separately.

The main outcome measure was suicide attempt during follow-up. Survival curves for the first suicide attempt after study entry were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the log-rank test was used in order to compare the groups. The Kaplan-Meier curve is defined as the probability of surviving in a given length of time and the log-rank test was used to compare the survival distribution of the sample.

An exploratory analysis of the relationships between each of the HAM-D-24 anxiety symptoms and suicide attempts during follow-up were analyzed using Cox proportional hazard regression. Also, the Cox proportional hazard regression was used to verify if any socio-demographic or clinical characteristics showing significant differences in baseline group comparison were associated with prospective suicide attempts. The Cox regression can investigate the effect of several variables on the risk of a specific event, taking into account the individual censoring times. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS Statistics software package, version 19.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline clinical characteristics

Of the 667 patients, 480 patients completed the three follow-up assessments (568 at 3 months, 492 at 12 months and 480 at 24 months).

Of the 667 patients at baseline, 229 (34.3%) had at least one lifetime comorbid anxiety disorder and 438 (65.7%) did not. One hundred and eighty-eight patients (28.2%) had a current anxiety disorder and 479 (71.8%) did not

Of the 229 patients with lifetime comorbid anxiety disorders, 153 (66.8%) had one anxiety disorder and 76 (33.2%) had two or more. Table 1 displays the number and type of comorbid anxiety disorders in these patients.

Table 1.

Number and type of comorbid anxiety disorders among patients with mood disorders

| Number of comorbid anxiety disorders |

Type of anxiety disorder |

Total N of patients | N of patients (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 anxiety comorbidity | Panic Disorder | 153 | 57 (37.3) |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 153 | 42 (27.5) | |

| Social phobia | 153 | 25 (16.3) | |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 153 | 18 (11.8) | |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 153 | 9 (5.9) | |

| Agoraphobia | 153 | 2 (1.3) | |

|

| |||

| 2 anxiety comorbidities | Panic Disorder | 62 | 44 (71) |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 62 | 43 (69.4) | |

| Social phobia | 62 | 20 (32.3) | |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 62 | 9 (14.5) | |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 62 | 4 (6.5) | |

| Agoraphobia | 62 | 4 (6.5) | |

|

| |||

| 3 anxiety comorbidities | Panic Disorder | 14 | 11 (78.6) |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 14 | 12 (85.7) | |

| Social phobia | 14 | 10 (71.4) | |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder compulsive disorder | 14 | 6 (42.9) | |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 14 | 2 (14.3) | |

| Agoraphobia | 14 | 1(7.1) | |

Table 2 displays the comparison between the two groups, by mood disorder (MDD, BD-I, BD-II, and BD-NOS), in terms of the presence of comorbid anxiety disorders.

Table 2.

Comorbidity with anxiety disorder in patients with different mood disorders using Chi Squared test

| Diagnosis | Lifetime anxiety disorders | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes N = 229 |

No N = 438 |

|

| MDD | 156 (68.1%) | 350 (79.9%)* |

| BD-I | 39 (17%) | 56 (12.8%)* |

| BD-II | 22 (9.6%) | 15 (3.4%)*** |

| BD-NOS | 12 (5.2%) | 17 (3.9%)* |

Abbreviations: MDD= major depressive disorder; BD-I = bipolar I disorder; BD-II = bipolar II disorder; BD-NOS: bipolar disorder not otherwise specified

p>0.05, non-significant

p=0.001

Comorbidity with an anxiety disorder was more common among the patients with BD-II than among those with any of the other primary diagnoses (chi-square = 15.65, p = .001).

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the patients with and without anxiety disorders are shown in Table 3. Females were more likely to have comorbid anxiety disorders than males. Patients with anxiety disorders also had higher scores for objective depression (HAM-D-24), subjective depression (Beck Depression Inventory), hopelessness, impulsivity, and hostility, than did those without anxiety disorders. Those with anxiety disorders were also more likely to report sexual or physical abuse in childhood.

Table 3.

Comparison of baseline socio-demographic and clinical characteristics among mood disordered individuals with and without anxiety disorders.

| Characteristics | Lifetime anxietydisorders | test | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 229) |

No (n = 438) |

|||

| Female sex, n (%) | 155 (68.0) | 233 (54.2) | 11.72a | .001 |

| Age. mean (SD) | 37.58 (11.5) | 37.69 (13.9) | 0.10b | .913 |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 15.13 (2.7) | 14.83 (3.0) | −1.18b | .236 |

| Single, n (%) | 125 (54.8) | 213 (50.1) | 8.43b | .077 |

| History of sexual or physical abuse, n (%) | 126 (56.8) | 125 (36.3) | 26.51a | ≤ .001 |

| Psychotic symptoms (lifetime), n (%) | 21 (9.7) | 48 (13.0) | 2.02a | .369 |

| History of suicide attempts, n (%) | 106 (46.5) | 207 (48.5) | 0.23a | .628 |

| Comorbid substance use (lifetime), n (%) | 61 (26.6) | 94 (21.5) | 2.25a | .133 |

| Comorbid cluster B personality disorders, n (%) | 70 (30.6) | 134 (30.5) | 1.07a | .994 |

| HAM-D-24 score, mean (SD) | 26.87 (8.8) | 25.02 (10.3) | −2.36b | .019 |

| BDI score, mean (SD) | 27.63 (11.4) | 24.70 (12.3) | −2.80b | .005 |

| BHS score, mean (SD) | 12.31 (5.8) | 10.79 (6.2) | −2.87b | .004 |

3.2. Clinical predictors of suicide attempts

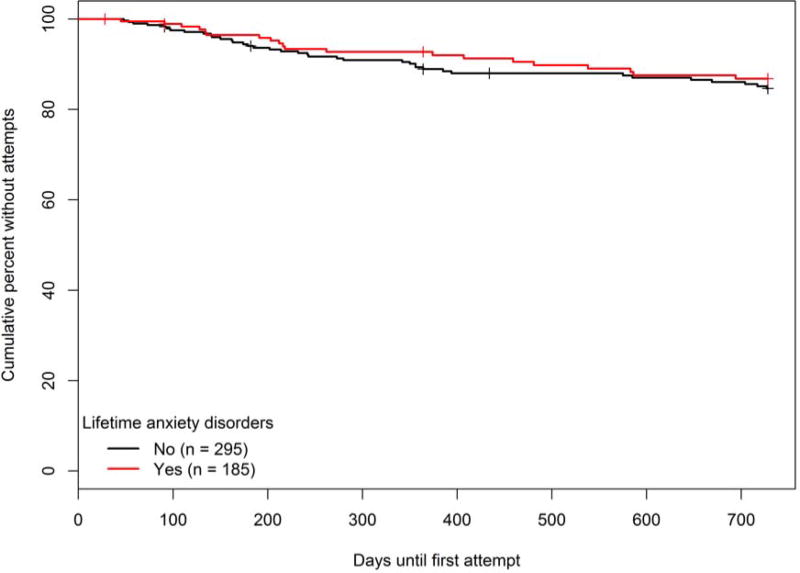

During the two-year follow-up period, 480 (72% of the original sample) completed the study. Of those, 63 patients (13.1%) attempted suicide at least once. Of those who had an attempt, 47 made one attempt, 10 made two attempts and 6 made three attempts, for a total of 85 attempts. Twenty-one patients (33.3% of the future attempters) had at least one comorbid anxiety disorder and 42 (66.7%) did not. Among future attempters, 46 (73%) had a diagnosis of MDD, 16 (25.4%) of BD type I and 1 (1.6%) BD type II. There were no suicide attempts in the follow-up in patients with BD NOS. There was no significant difference in mood disorder diagnoses between the attempters (chi-square test 6.75, p=0.08) although this result suggests a trend towards patients with BD type I having more suicides attempts in the follow-up. There were no suicide deaths during the follow-up. Survival curves showed that patients with and without comorbid anxiety disorders did not differ in terms of the occurrence of suicide attempts during follow-up (log-rank test = 0.269, p = 0.604) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

In a sensitivity analysis using Kaplan–Meier survival curves and the log-rank test, we compared patients without anxiety disorders, patients with one comorbid anxiety disorder, and patients with two or more comorbid anxiety disorders. The three groups did not differ in terms of the occurrence of suicide attempts during follow-up (log-rank test = 0.586, p = 0.746). Because panic disorder, social phobia, and post-traumatic stress disorder were the most common comorbidities in our sample, we also evaluated those comorbidities separately in sensitivity analyses using survival curves. We found that suicide attempts were not associated with panic disorder (log-rank test = 0.205, p = 0.651), social phobia (log-rank test = 1.16, p = 0.281), or post-traumatic stress disorder (log-rank test = 0.006, p = 0.938).

Restricting the analysis to those with current anxiety disorders at baseline, there was no significant difference in the occurrence of suicide attempts during follow-up between patients with current anxiety disorders and patients without them (p=0.851).

Due to the high rate of depressed patients at baseline according to SCID-I criteria for current mood episode (556 patients, 83.4% of the sample), we conducted a secondary analysis to verify if being depressed at baseline was associated with future attempts and there was no association between depressive episode at baseline and future attempts (χ2=0.12, df=1,p=0.914). Another analysis conducted to verify if being currently depressed and having a current anxiety disorder (N=145 patients) were associated with attempts during follow-up showed no significant difference between groups (χ2= 1.63, df=1, p=0.201)

To determine whether other significant clinical variables constituted a risk factor for suicide attempts, we performed Cox proportional hazard regression. The independent variables were the variables that were significant different between patients with and without comorbid anxiety disorders in the univariate analysis: female sex; MDD; BD-I; BD-II; BD-NOS; history of abuse; Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score; Beck Depression Inventory score; Beck Hopelessness Scale score; Buss–Durkee Hostility Inventory score; Barratt Impulsiveness Scale score; history of previous suicide attempts. The independent variable was suicide attempt during follow-up. Only previous attempts, female sex, and higher scores on the Buss–Durkee Hostility Inventory were associated with future suicide attempts. The results of the regression analysis are shown in Table 4. As an exploratory analysis, we performed a Cox regression with the same significant variables and added the anxiety symptoms (agitation, somatic anxiety, psychic anxiety and hypochondriasis) as independent variables. None of the anxiety symptoms was associated with suicide attempts (agitation: HR=1.076, p=0.784; psychic anxiety: HR= 1.027, p=0.838; somatic anxiety: HR= 0.945, p=0.075) and hypochondriasis appears as a protective factor (HR= 0.60, p=0.011).

Table 4.

Baseline risk factors associated with suicide attempts during follow-up using Cox proportional hazard regression.

| Variable | Wald | p-value | Hazard ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 11.19 | ≤ .001 | 3.66 | 1.71–7.84 |

| History of suicide attempts | 10.40 | ≤ .001 | 3.27 | 1.59–6.74 |

| BDHI | 14.94 | ≤ .001 | 1.05 | 1.02–1.08 |

| BD-I | 3.15 | 0.076 | 1.50 | 0.77–2.92 |

| BD-II | 0.08 | 0.930 | 1.24 | 0.16–9.24 |

| BD-NOS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| History of sexual or physical abuse | 0.05 | 0.811 | 0.92 | 0.49–1.73 |

| HAM-D-24 score | 1.13 | 0.286 | 1.02 | 0.98–1.03 |

| BIS score | 2.42 | 0.120 | 1.03 | 0.99–1.03 |

| BDI score | 1.47 | 0.022 | 1.01 | 0.98–1.05 |

| BHS score | 1.84 | 0.174 | 0.96 | 0.90–1.01 |

|

| ||||

| Abbreviations: BDHI = Buss–Durkee Hostility Inventory; BD-I = bipolar I disorder; BD-II = bipolar II disorder; BD-NOS = bipolar disorder not otherwise specified; HAM-D-24 = 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; BIS = Barratt Impulsivity Scale; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; BHS = Beck Hopelessness Scale. | ||||

|

| ||||

| SSI score, mean (SD) | 6.85 (8.33) | 6.09 (7.7) | −1.16b | .254 |

| BIS score, mean (SD) | 54.71 (15.8) | 49.58 (18.6) | −3.28b | .001 |

| BDHI score, mean (SD) | 37.84 (11.5) | 34.34 (12.7) | −3.18b | .002 |

| BGAS score, mean (SD) | 19.03 (5.6) | 18.48 (5.4) | −1.16b | .246 |

Abbreviations: HAM-D-24 = 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; BHS = Beck Hopelessness Scale; SSI = Scale for Suicidal Ideation; BIS = Barratt Impulsiveness Scale; BDHI = Buss–Durkee Hostility Inventory; BGAS = Brown–Goodwin Aggression Scale A=Chi Squared; B=t-test

4. Discussion

Contrary to our hypothesis, patients with and without lifetime comorbid anxiety disorders did not differ significantly in terms of the risk of suicide attempt during the two-year follow-up period. Also, the number of comorbid anxiety disorders, type of anxiety disorders (panic disorder, PTSD and social phobia in our sample), being depressed and with a current anxiety disorder at study entry were not associated with suicide attempts during the follow-up. The strongest predictors of suicide attempt in our sample were previous suicide attempts, female sex, and higher scores on the Buss–Durkee Hostility Inventory. In exploratory analysis, anxiety symptoms of agitation, somatic anxiety and physical anxiety were not associated with future attempts and hypochondriasis was protective against suicide attempt during follow-up.

There are conflicting data regarding the effect of comorbid anxiety disorders in the context of a mood disorder, on the risk of suicide attempt. In two previous retrospective studies conducted by our group based on smaller samples, we found no association between anxiety disorders and suicide attempts. In a retrospective study evaluating depressed bipolar patients with anxiety disorders, the authors found that the presence of anxiety disorders was not associated with suicide attempts[29]. In another study evaluating patients with MDD with and without comorbid panic disorder there was no association between a lifetime history of suicide attempts and comorbid panic disorder [20]. Also, in another retrospective study with a mixed sample of BD and MDD patients, there was no association between comorbid anxiety disorders and a history of suicide attempts [30].

In longitudinal studies in which comorbid anxiety disorders were evaluated, risk factors for suicide attempts were female sex, current depressive episode, age over 40 years, and previous suicide attempts were associated with suicide attempts during 5-year follow-up [15]. Another study also found that anxiety disorders among mood disordered patients did not constitute a risk factor for suicide attempts, the most powerful predictors being previous suicide attempts, the subjective rating of the severity of depression, and smoking [13]. Those studies showed that comorbidity with anxiety disorders was not a risk factor for suicide attempts during follow-up, which is in agreement with our findings Contrary to our findings several studies showed an association between prospective suicide attempts and comorbid anxiety disorders lifetime [10,11,12]. These differences may be explained by differences in sample selection (these studies were done with epidemiological samples in contrast to our sample, which was from both New York State Psychiatric Institute and from the community). Another difference is none of these studies evaluated a mixed sample with patients with MDD and BD, which could lead to the contradictory findings.

We also observed that, among anxiety symptoms at baseline, agitation, psychic anxiety, and somatic anxiety were not associated with suicide attempts during follow-up, and that hypochondriasis was protective against suicide attempts. Similar to our findings, a study using also the anxiety symptoms present in HAM-D scale, found that those same four symptoms were more common among non-attempters than among attempters, although it was a retrospective analysis with only patients with MDD [20]. Contrary to our findings, an association between anxiety symptoms (panic attacks and severe psychic anxiety) and suicide attempts has been reported in a prospective study [31]. One possible explanation for these contradictory findings is that maybe anxiety symptoms could be protective if associated with fear of death or illness [19]. By definition, hypochondriasis is an overwhelming preoccupation with disease and a fear of dying. Therefore, it makes sense that patients with hypochondriasis were less likely to engage in suicidal behavior. Other risk factors associated with suicide attempts in our study were previous suicide attempts, female sex, and higher scores for hostility. A history of suicide attempts has been documented as a risk factor in retrospective and prospective studies [32]. Two prospective studies involving patients with mood disorders found that a history of suicide attempts was a risk factor for future attempts as in the present study, with hazard ratio of 4.39 (95% CI = 1.78–10.8) [15] and a hazard ratio of 4.41 (95% CI = 1.92–10.12) [13], strikingly congruent findings. Female sex was also found to be a risk factor for suicide attempts in some previous prospective studies [13,33] although not in others [15]. Other studies have also demonstrated that female sex is associated with a higher prevalence of subjective depression symptoms and stressful life events [13,33] both of which are also risk factors for suicide attempts.

There have been few studies investigating the role of hostility in suicide attempts. In a computer-assisted review of the literature, we identified no studies evaluating the role of hostility in patients with mood disorders and comorbid anxiety disorders. In this study, we observed that patients with comorbid anxiety disorders had significantly higher scores for impulsivity, aggression, and hostility than did those without. In a previous study,hostility scores itself did not predict future suicide attempts, although a factor comprising hostility, impulsivity, and aggression scores was associated with an OR of 2.26 for future suicide attempts in patients with mood disorders [13]. Further studies should investigate the role of hostility as a risk factor for suicide attempts in patients with comorbid anxiety disorder.

These findings contribute to the ongoing debate in the literature about whether anxiety disorders constitute a risk factor per se or if they are linked to a more severe course of mood disorders [34,35,36]. Although in our study lifetime comorbid of anxiety disorders were not a risk factor for future suicide attempts, we note that the patients with anxiety disorders had higher scores for depression, hopelessness, suicidal ideation, impulsivity, aggression, and hostility, all risk factors for suicide attempts [36]. Our findings supports the hypothesis that comorbidity with anxiety disorders is not a risk factor per se but either is associated with or modifies other risk factors associated with suicide attempts.

There were some limitations to our study. The absence of a controlled treatment for mood and anxiety disorders makes it difficult to interpret the impact of new onset mood episodes or of the treatment of either anxiety disorders or depressive episodes during the follow-up. Also the 2- year length of the study with a relatively long time between assessments could account for memory bias from the participants. Also, because the incidence of suicide attempt is low, two years might be a relatively short follow-up period. In addition, due to the paucity of participants with some anxiety disorders (agoraphobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder), we were unable to compare all anxiety disorders separately. As well, using lifetime anxiety disorder as a yes/no categorical variable and the lack of information regarding anxiety symptoms or anxiety disorders in the time of the attempts could influence the results. Also, we did not use a specific instrument to evaluate the severity of anxiety symptoms or anxiety disorders themselves. Indeed, although we used some Hamilton scale items as a marker of anxiety severity, better assessments of severity of anxiety symptoms/disorders may show a role for anxiety symptoms in suicide attempts.

5. Conclusions

The presence of comorbid anxiety disorders does not seem to be a risk factor for suicide attempts in patients with mood disorders, although patients with anxiety disorders had significant higher scores for depression, hopelessness, suicidal ideation, impulsivity, aggression, and hostility, all risk factors for suicide attempts. In this study, suicide attempts were associated with other well-known risk factors for suicidal behavior, such as female gender, past suicide attempts and hostility Further studies with longer follow-up periods and more detailed evaluation of specific anxiety symptoms could clarify the role of comorbid anxiety disorder and anxiety symptoms as risk factors for suicidal behavior.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant numbers NIMH P50 MH62185 and MH090964 [project name ``Conte Center for the Neuroscience of Mental Disorders: The Neurobiology of Suicidal Behavior"]; and NIMH R01 MH59710 [project name ``Pharmacotherapy of High-Risk Bipolar Disorder"].

We are grateful to the statistician Bernardo Dos Santos for his valuable collaboration; to Tecnisa SA, for its generous donation to PROMAN, and to the Brazilian Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, National Council for Scientific and Technological Development), for providing scholarship funding.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

Dr. Abreu received editorial fees from Cristalia and Supera Laboratories, Brazil Dr. Sullivan reports employ/stockholder from Tonix Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Dr. Burke receives royalties for the commercial use of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale

Dr. Galfalvy reports family owns from Illumina Inc

Dr. Lafer reports grants from CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico e Tecnologico)

Dr. Mann receives royalties for the commercial use of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale

Dr. Oquendo receives royalties for the commercial use of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale and Dr. Oquendo's family owns stock in Bristol Myers Squibb.

References

- Isometsa E. Suicidal Behavior in mood disorders – who, when and why? Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(3):120–130. doi: 10.1177/070674371405900303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick JM, Pankratz VS. Affective disorders and suicide risk: a reexamination. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1925–1932. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone KM, Haas GL, Sweeney JA, Mann JJ. Major depression and the risk of attempt suicide. J Affect Disord. 1995;34(3):173–185. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00015-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokero TP, Melartin TK, Rytsälä HJ, Leskelä US, Lestelä-Mielonen PS, Isometsä ET. Suicidal ideation and attempts among psychiatric patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(9):1094–1100. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valtonen H, Suominen K, Mantere O, Leppämäki S, Arvilommi P, Isometsä ET. Suicidal ideation and attempts in bipolar I and II disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(11):1456–1462. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Sutton L, Haw C, Sinclair J, Harris L. Suicide and suicide attempts in bipolar disorder: a systematic review of risk factors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(6):693–704. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Casañas I, Comabella C, Haw C, Saunders K. Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2013;147:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer A, Isometsä ET, Tondo L, Moreno D, Turecki G, Reis C, Cassidy F, Sinyor M, Azorin JM, Kessing LV, Ha K, Goldstein T, Weizman A, Beautrais A, Chou YH, Diazgranados N, Levitt AJ, Zarate CA, Rihmer Z, Yatham LN. International Society for bipolar disorders task force on suicide: meta-analysis and metaregression of correlates of suicide attempts and suicide deaths in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(1):1–16. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwar A, Malik S, Prokop LJ, Sim LA, Feldstein D, Wang Z, Murad MH. The association between anxiety disorders and suicidal behaviors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(10):917–29. doi: 10.1002/da.22074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, de Graaf R, Asmundson GJ, ten Have M, Stein MB. Anxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: a population-based longitudinal study of adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(11):249–1257. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton JM, Pagura J, Enns MW, Grant B, Sareen J. A population-based longitudinal Study of risk factors for suicide attempts in major depressive disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44:817–826. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala R, Goldstein BI, Morcillo C, Liu SM, Castellanos M, Blanco C. Course of comorbid anxiety disorders among adults with bipolar disorder in the U.S population. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(7):865–872. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Galfavy H, Russo S, Ellis SP, Grunebaum MF, Burke AK, Mann JJ. Prospective study of clinical predictors of suicidal acts after a major depressive episode in patients with major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1433–1441. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valtonen HM, Suominen K, Mantere O, Leppamaki S, Arvilommi P, Isometsa ET. Prospective study of risk factors for attempted suicide among patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:576–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holma KM, Haukka J, Suominen K, Valtonen HM, Mantere O, Merlatin TK, Sokero TP, Oquendo MA, Isometsa ET. Differences in incidence of suicide attempts between bipolar I and II disorders and Major depressive disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16:652–661. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaziuddin N, King CA, Naylor MW, Ghaziuddin M. Anxiety contributes to suicidality in depressed adolescents. Depress Anxiety. 2000;11(3):134–138. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(2000)11:3<134::aid-da9>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Broadhead WE, Weissman MM, Leon AC, Farber L, Hoven C, Kathol R. Subthreshold psychiatric symptoms in a primary care group practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(10):880–886. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830100026004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitoft GR, Rosen M. Is perceived nervousness and anxiety a predictor of premature mortality and severe morbidity? A longitudinal follow-up of the Swedish survey of living conditions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:794–798. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.033076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunebaum MF, Keilp J, Li S, Ellis SP, Burke AK, Oquendo MA, Mann JJ. Symptom components of standard depression scales and past suicidal behavior. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(1):73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Placidi GP, Oquendo MA, Malone KM, Brodsky B, Ellis SP, Mann JJ. Anxiety in major depression: relationship to suicide attempts. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(10):1614–1618. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6(4):278–296. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L. The measurement of pessimism: the Hopelessness Scale. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1974;42:861–865. doi: 10.1037/h0037562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GL, Goodwin FK, Ballenger JC, Goyer PF, Major LF. Aggression in humans correlates with cerebrospinal fluid amine metabolites. Psychiatry Res. 1979;1:131–139. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(79)90053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Durkee A. An inventory for assessing different kinds of hostility. J Consult Psychol. 1957;21:343–349. doi: 10.1037/h0046900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barratt ES. Factor analysis of some psychometric measures of impulsiveness and anxiety. Psychol Rep. 1965;16:547–554. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1965.16.2.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1979;47:343–352. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Halberstam B, Mann JJ, In First MB, editors. Standardized Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 1. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2003. pp. 103–130. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa A, Grunebaum MF, Sullivan GM, Currier D, Ellis SP, Burke AK, Brent DA, Mann JJ, Oquendo MA. Comorbid anxiety in bipolar disorder: does it have an independent effect on suicidality? Bipolar Disord. 2008;10(4):530–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00590.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak J, Dmitrzak-Węglarz M, Skibińska M, Szczepankiewicz A, Leszczyńska-Rodziewicz A, Rajewska-Rager A, Maciukiewicz M, Czerski P, Hauser J. Suicide attempts and psychological risk factors in patients with bipolar and unipolar affective disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(3):309–313. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett J, Scheftener WA, Fogg L. Time-related predictors of suicide in major affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:1189–1194. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.9.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Currier D, Mann JJ. Prospective studies of suicidal behavior in major depressive and bipolar disorders: what is the evidence for predictive risk factors? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114(3):151–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Bongiovi-Garcia ME, Galfavy H, Goldberg PH, Grunebaum MF, Burke AK, Mann JJ. Sex differences in clinical predictors of suicidal acts after major depression: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:134–141. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.1.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir M, Kaplan Z, Efroni R, Kotler M. Suicide risk and coping styles in posttraumatic stress disorder patients. Psychother Psychosom. 1999;68(2):76–81. doi: 10.1159/000012316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon NM, Zalta AK, Otto MW, Ostacher MJ, Fischmann D, Chow CW, Thompson EH, Stevens JC, Demopulos CM, Nierenberg AA, Pollack MH. The association of comorbid anxiety disorders with suicide attempts and suicidal ideation in outpatients with bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41(3–4):255–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ, Waternaux C, Haas GL, Malone KM. Toward a clinical model of suicidal behavior in psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(2):181–189. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]