Abstract

The sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase SERCA promotes muscle relaxation by pumping calcium ions from the cytoplasm into the sarcoplasmic reticulum. SERCA activity is regulated by a variety of small transmembrane peptides, most notably by phospholamban in cardiac muscle and sarcolipin in skeletal muscle. However, how phospholamban and sarcolipin regulate SERCA is not fully understood. In the present study, we evaluated the effects of phospholamban and sarcolipin on calcium translocation and ATP hydrolysis by SERCA under conditions that mimic environments in sarcoplasmic reticulum membranes. For pre-steady-state current measurements, proteoliposomes containing SERCA and phospholamban or sarcolipin were adsorbed to a solid-supported membrane and activated by substrate concentration jumps. We observed that phospholamban altered ATP-dependent calcium translocation by SERCA within the first transport cycle, whereas sarcolipin did not. Using pre-steady-state charge (calcium) translocation and steady-state ATPase activity under substrate conditions (various calcium and/or ATP concentrations) promoting particular conformational states of SERCA, we found that the effect of phospholamban on SERCA depends on substrate preincubation conditions. Our results also indicated that phospholamban can establish an inhibitory interaction with multiple SERCA conformational states with distinct effects on SERCA's kinetic properties. Moreover, we noted multiple modes of interaction between SERCA and phospholamban and observed that once a particular mode of association is engaged it persists throughout the SERCA transport cycle and multiple turnover events. These observations are consistent with conformational memory in the interaction between SERCA and phospholamban, thus providing insights into the physiological role of phospholamban and its regulatory effect on SERCA transport activity.

Keywords: allosteric regulation, calcium ATPase, cardiac muscle, membrane transport, sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), calcium translocation, phospholamban, sarcolipin, solid supported membrane

Introduction

The sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR)4 Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) plays a central role in muscle relaxation by removing calcium from the cytosol and transporting it into the lumen of the SR. The mechanism of active calcium transport by SERCA has been well described (1–3). According to the original E1-E2 scheme (4), SERCA activation requires the binding of two calcium ions (E1-Ca2) followed by formation of a phosphoenzyme intermediate from ATP (E1P). The free energy from ATP, captured in phosphoenzyme formation, is used for a conformational transition (E1P to E2P) that favors the release of calcium into the SR in exchange for luminal protons. Hydrolytic cleavage of the phosphoenzyme intermediate (dephosphorylation) is the final reaction step, which returns the enzyme to the ground state and allows the initiation of a new transport cycle. Crystal structures of most of the intermediates in the reaction cycle have been determined, providing a thorough description of SERCA at atomic detail (for reviews, see Refs. 1–3).

SERCA transport activity in muscle cells is regulated by the homologous membrane proteins phospholamban (PLN; 52 amino acids) and sarcolipin (SLN; 31 amino acids). PLN is primarily expressed in cardiac muscle where it regulates SERCA2a, whereas SLN expression predominates in skeletal muscle where it regulates SERCA1a. PLN and SLN interact with SERCA in a groove formed by transmembrane helices M2, M6, and M9 as characterized by cross-linking studies (5), molecular modeling (6), NMR (7, 8), and X-ray crystallography (9–11). PLN lowers the apparent calcium affinity of SERCA, and this inhibitory effect is reversed upon PLN phosphorylation by protein kinase A (12), calcium-calmodulin–dependent protein kinase II (13), or Akt (14). It has been hypothesized that SLN alters the apparent calcium affinity of SERCA in a manner similar to PLN. However, the molecular mechanism (15, 16) and physiological consequences (17) of SLN inhibition are distinct from PLN.

In addition to cytosolic calcium levels and phosphorylation status, the oligomeric state of PLN plays a critical role in SERCA regulation. PLN exists as an equilibrium mixture of monomers and pentamers, both of which are required for normal cardiac function (18). The main inhibitor is the PLN monomer, which physically interacts with SERCA and alters its apparent affinity for calcium. The PLN pentamer has been described as an inactive storage form; however, experimental evidence suggests that the PLN pentamer also interacts with SERCA (19), and it forms a cation-selective pore (20–22). Although the consensus model for PLN regulation of SERCA involves the reversible association of a monomer under calcium-free conditions, there is a growing body of evidence that PLN remains associated with SERCA and adopts multiple conformational states in the SERCA–PLN complex (19, 23–25).

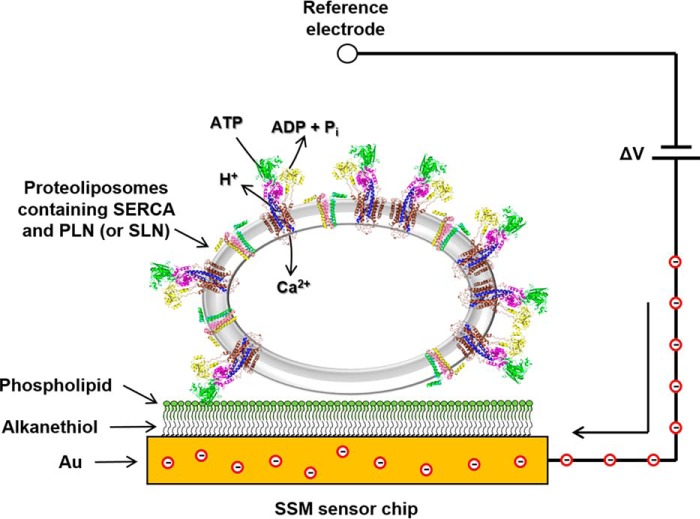

To address this, we evaluated the effects of PLN and SLN on ATP-dependent calcium translocation by SERCA using pre-steady-state current measurements on a solid-supported membrane (SSM; Fig. 1). The SSM method has been used to investigate the ion translocation mechanism of P-type ATPases (26, 27). We performed current measurements on co-reconstituted proteoliposomes containing SERCA and PLN or SLN. Such proteoliposomes have been used extensively to characterize PLN structure and function (7, 19, 28–33) and more recently to investigate SERCA inhibition by SLN (15). The proteoliposomes were adsorbed to the SSM and activated by a calcium and/or ATP concentration jump. Following SERCA activation, an electrical current was detected related to the displacement of calcium ions within the protein during the first catalytic cycle (27, 34, 35). These results from pre-steady-state charge translocation during the first SERCA turnover were compared with steady-state measurements of ATPase activity during continuous turnover (32, 33). The choice of substrate conditions promoted particular conformational states of SERCA from which catalytic turnover could be initiated. We found that the effect of PLN on SERCA activity depended on the starting conditions, and our observations were consistent when comparing pre-steady-state charge translocation with steady-state ATPase activity. In contradiction to previous hypotheses, we conclude that PLN can interact with at least two conformational states of SERCA with distinct effects on SERCA's maximal activity, apparent calcium affinity, and cooperative calcium binding. Moreover, once a particular SERCA–PLN inhibitory interaction was established, it persisted during continuous catalytic turnover of SERCA. This “conformational memory” (36) in the SERCA–PLN regulatory complex provides insights into the functional relevance of the published crystal structures of SERCA bound to PLN (11) and SLN (9, 10).

Figure 1.

SSM technique. A schematic diagram of a proteoliposome containing SERCA and PLN adsorbed to a SSM and subjected to an ATP concentration jump is shown. If the ATP jump induces net charge displacement across the protein, a current transient is measured (the red circles are electrons) when the potential difference applied across the whole system is kept constant.

Results

In the present study, we focused on SERCA1a in the presence of PLN and SLN. The skeletal muscle SERCA1a isoform is a validated surrogate for the cardiac SERCA2a isoform (e.g. see Figs. 3 and 9 in Ref. 37). Perhaps most importantly, SERCA1a was shown to functionally substitute for SERCA2a in the heart, including regulation by endogenous PLN (38, 39). Herein, we use the term “SERCA” to designate the SERCA1a isoform.

Pre-steady-state charge movement

ATP jumps

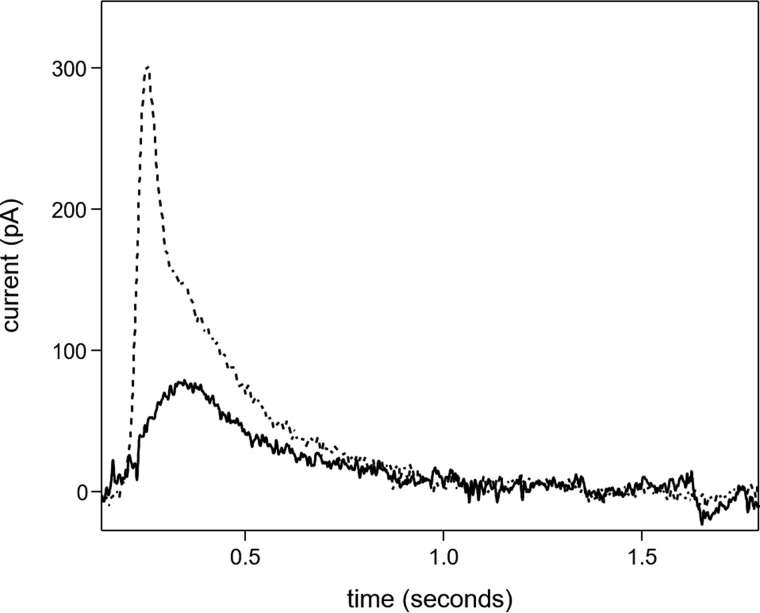

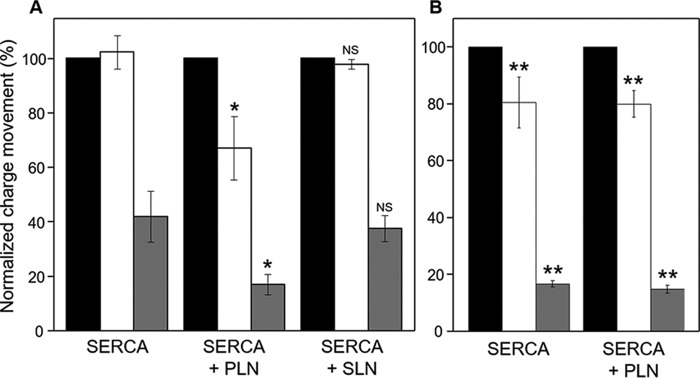

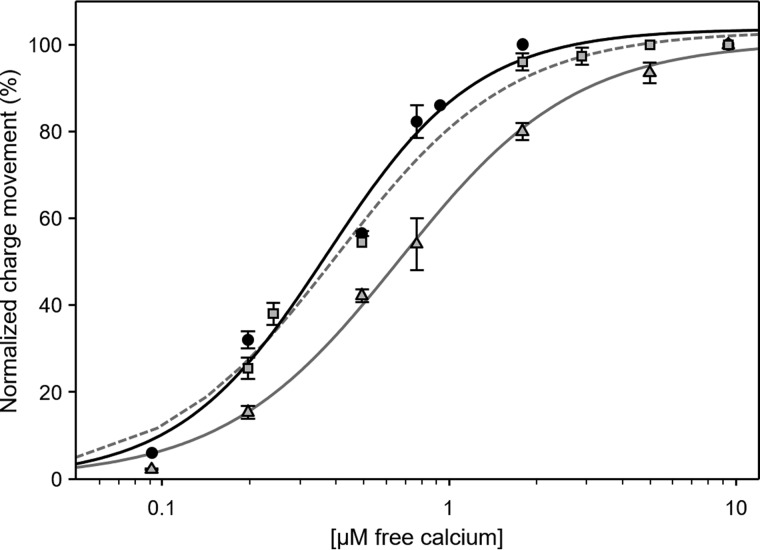

SERCA proteoliposomes were characterized by pre-steady-state current measurements on an SSM following ATP jumps (Fig. 2; preincubation with calcium and reaction initiation with ATP; condition ii in Table 1). The charge obtained by integration of the ATP-induced current transient is attributable to the translocation of calcium into the proteoliposomes during the first SERCA transport cycle (27, 34, 35). To confirm that the measured current is due to SERCA, we performed an ATP jump in the presence of thapsigargin (40), which caused nearly complete suppression of the current transient (not shown). ATP jumps were then carried out on SERCA–PLN proteoliposomes. The ATP-induced current signals at 3 and 0.3 μm free calcium were reduced compared with proteoliposomes containing SERCA alone (Fig. 3A). As expected, PLN affected ATP-dependent calcium translocation by SERCA. ATP jumps were performed over a range of calcium concentrations, and the resulting displaced charges were analyzed using the Hill equation (Fig. 4 and Table 1; calcium concentration at half-maximal activity (KCa) of 0.70 μm). It is interesting to compare this value with that determined for proteoliposomes containing SERCA alone (KCa of 0.38 μm). Overall, these pre-steady-state values are in good agreement with previous measurements of SERCA ATPase activity in the absence and presence of PLN (32, 33).

Figure 2.

ATP-induced current transients. Current transients observed following an ATP concentration jump on proteoliposomes containing SERCA in the presence of 10 (dashed line) and 0.3 μm free Ca2+ (solid line) are shown.

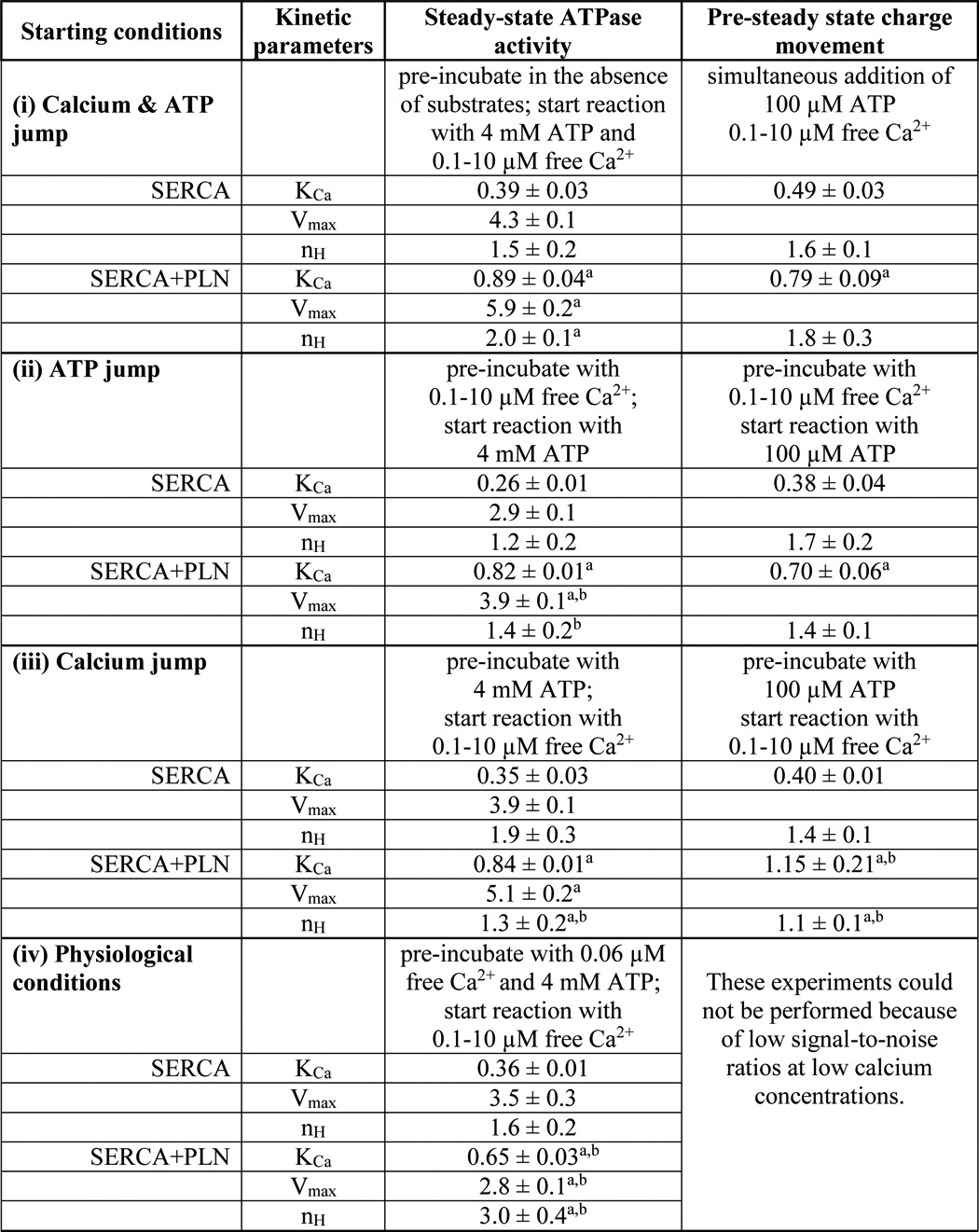

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for SERCA and SERCA–PLN proteoliposomes derived from pre-steady-state charge movement and steady-state ATPase activity measurements

Statistical significance was evaluated based on a threshold p value (p < 0.05). See Table S1 for a full comparison of all kinetic parameters and the associated p values.

Figure 3.

Effects of PLN and SLN on ATP-dependent Ca2+ translocation by SERCA. Normalized charges related to ATP concentration jumps on proteoliposomes containing SERCA, SERCA + PLN, or SERCA + SLN in the presence of 1 mm MgCl2 (A) and 5 mm MgCl2 (B) are shown. Free Ca2+ concentrations used were 10 (black columns; control measurement), 3 (white columns), and 0.3 μm (gray columns). Values are normalized with respect to the charge obtained following a 100 μm ATP jump in the presence of 10 μm free Ca2+. Error bars represent S.E. of at least four independent measurements. *, p < 0.01 compared with SERCA alone in A. **, p < 0.01 compared with SERCA alone in A but not significantly different when compare with each other. NS, not significant compared with SERCA alone in A.

Figure 4.

SERCA charge translocation as a function of Ca2+ concentration in the presence of PLN or SLN. Normalized charges related to ATP concentration jumps on proteoliposomes containing SERCA (circles; black line), SERCA + PLN (triangles; gray line), or SERCA + SLN (squares; gray dashed line) in the presence of various Ca2+ concentrations are shown. Values are normalized with respect to the charge obtained following a 100 μm ATP jump in the presence of 10 μm free Ca2+. The lines represent curve fitting of the experimental data using the Hill equation (kinetic parameters can be found in Table 1). Error bars represent S.E. of at least four independent measurements.

We next performed current measurements on SERCA–SLN proteoliposomes. In this case, the displaced charges measured after ATP jumps at 3 and 0.3 μm free calcium were indistinguishable from those obtained for proteoliposomes containing SERCA alone (Figs. 3A and 4; KCa of 0.43 μm and Hill coefficient (nH) of 1.6 in the presence of SLN). There have been conflicting reports on the regulatory effect of SLN on SERCA. One study reported that SLN decreased the apparent calcium affinity of SERCA and stimulated the maximal calcium uptake rate (41). Another recent study reported that SLN decreases the maximal activity of SERCA, but it does not affect the apparent calcium affinity (16). Based on our recent studies using the SERCA–SLN proteoliposomes, we believe that SLN decreases both the apparent calcium affinity and maximal activity of SERCA (15). Nonetheless, these perplexing observations may reflect the nature of the experimental systems (cells versus purified components and calcium transport versus ATP hydrolysis).

Finally, we found that a high magnesium concentration (5 mm) eliminated the effect of PLN on the ATP-induced, SERCA-dependent charge movement in proteoliposomes regardless of the calcium concentration (Fig. 3B). Unexpectedly, 5 mm magnesium decreased charge translocation by SERCA proteoliposomes, which became indistinguishable from SERCA–PLN proteoliposomes in the presence of either 5 or 1 mm magnesium. In other words, 5 mm magnesium promotes a SERCA response that is comparable with PLN inhibition, but this response cannot be further modulated by PLN (Fig. 3, A and B, compare bars for SERCA and SERCA + PLN). The decrease in charge translocation may reflect competitive binding of calcium and magnesium to SERCA where the magnesium affinity is low (∼mm) but significant at low calcium concentrations (2). As seen in recent crystal structures (9, 10), magnesium may stabilize the calcium-binding sites of an E1-like SERCA conformation, which is not catalytically active for charge transport until the magnesium has been displaced.

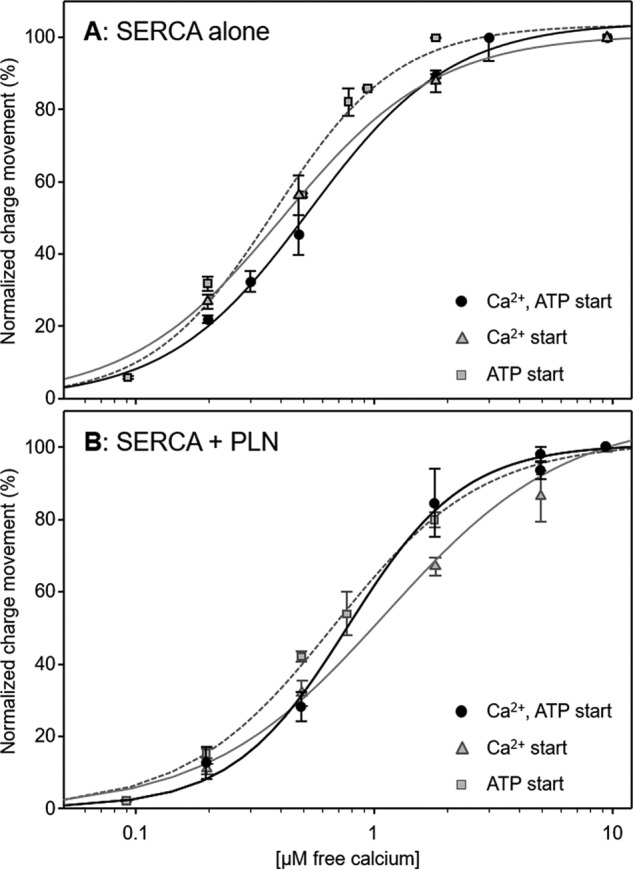

Simultaneous calcium and ATP jumps

To gain further insights into the effect of PLN on the SERCA transport cycle, we performed simultaneous ATP (100 μm) and calcium (varying concentrations) jumps with proteoliposomes containing SERCA and PLN (starting condition i in Table 1). As shown in Fig. 5 and Table 1, we observed a decrease in the calcium affinity of SERCA (KCa of 0.79 μm) and comparable cooperativity for calcium binding (nH of 1.8) with respect to the values obtained following simultaneous ATP and calcium jumps for proteoliposomes containing SERCA alone (KCa of 0.49 μm and nH of 1.6). The simultaneous addition of calcium and ATP mimics conditions used for steady-state measurements of SERCA ATPase activity. Thus, the kinetic parameters agree well with previous observations (32, 33). Simultaneous ATP and calcium jumps with proteoliposomes containing SERCA and SLN were again indistinguishable from those obtained for proteoliposomes containing SERCA alone (not shown). We conclude that, under the conditions used to measure charge translocation during the first SERCA transport cycle, SLN does not alter SERCA function.

Figure 5.

Charge translocation as a function of calcium concentration for proteoliposomes under different starting conditions. A, proteoliposomes containing SERCA alone. B, proteoliposomes containing SERCA and PLN. Normalized charges related to simultaneous ATP (100 μm) and free Ca2+ (various concentrations) jumps are indicated by circles and a black line. Values are normalized with respect to the charge obtained following a simultaneous 100 μm ATP and 10 μm free Ca2+ jump. Normalized charges related to free Ca2+ (various concentrations) jumps in the presence of 100 μm ATP are indicated by triangles and a gray line. Values are normalized with respect to the charge obtained following a 10 μm free Ca2+ jump in the presence of 100 μm ATP. Normalized charges related to ATP jumps in the presence of various Ca2+ concentrations are indicated by squares and a gray dashed line. Values are normalized with respect to the charge obtained following a 100 μm ATP jump in the presence of 10 μm free Ca2+. The lines represent curve fitting of the experimental data using the Hill equation (kinetic parameters can be found in Table 1). Error bars represent S.E. of at least four independent measurements.

Calcium jumps

The differences between ATP jumps and simultaneous calcium–ATP jumps prompted us to investigate calcium as the initiating event for SERCA-dependent charge displacement (starting condition iii in Table 1). Calcium jumps were carried out on proteoliposomes containing SERCA and PLN preincubated with ATP (100 μm). These conditions resulted in a much lower apparent calcium affinity of SERCA (KCa of 1.15 μm) and reduced cooperativity (nH of 1.1) for calcium binding (Fig. 5 and Table 1) as compared with the results obtained following calcium jumps for proteoliposomes containing SERCA alone preincubated with ATP (KCa of 0.40 μm and nH of 1.4). Thus, preincubation of SERCA–PLN with saturating ATP followed by calcium jumps led to a reduction in the apparent calcium affinity and cooperativity for calcium binding by SERCA. The results support the view that calcium and ATP promote slightly different SERCA conformational states from which the transport cycle can be initiated. Although this latter point may seem obvious, PLN inhibition still occurred under the different initiating conditions, although the kinetic effects and nature of PLN inhibition depend on how SERCA was poised before initiation of the transport cycle.

Steady-state ATPase activity

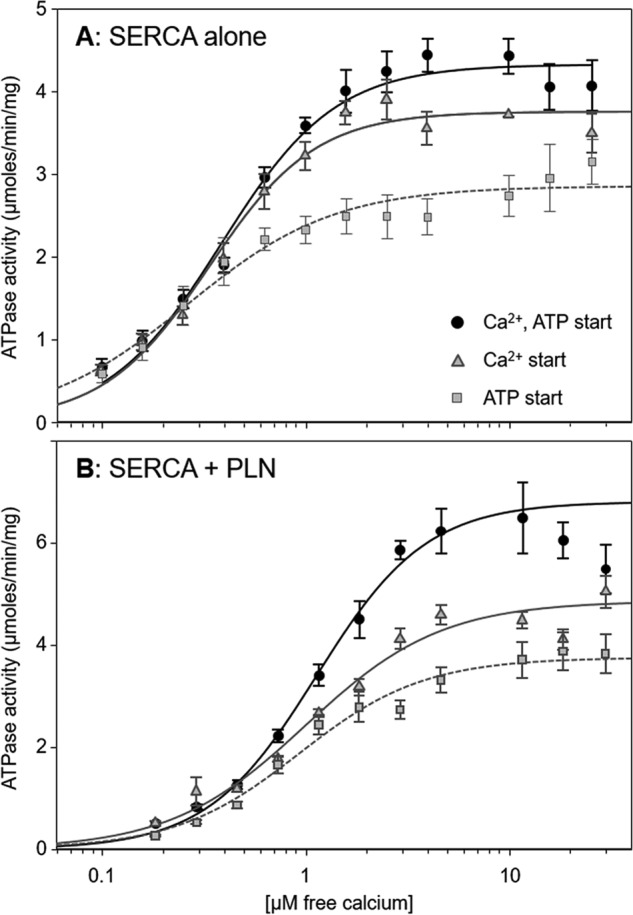

Measurement of ATP hydrolysis rates of the SERCA proteoliposomes in the absence and presence of PLN (31–33) provided an important benchmark for the pre-steady-state measurements. We determined the ATPase activity of SERCA alone and in the presence of PLN with the preincubation and starting conditions described above. Proteoliposomes containing SERCA alone or SERCA and PLN (Fig. 6) were subjected to the following conditions (Table 1): condition i, reaction initiation by the simultaneous addition of calcium and ATP, condition ii, reaction initiation by the addition of ATP, and condition iii, reaction initiation by the addition of calcium (0.1–10 μm). The outcome of these experiments prompted us to include condition iv with more physiological substrate concentrations. It should be noted that the measurement of steady-state ATPase activity was performed with 4 mm ATP and 5 mm magnesium. These conditions differ from those used in pre-steady-state measurements.

Figure 6.

ATPase activity as a function of Ca2+ concentration for proteoliposomes under different starting conditions. A, proteoliposomes containing SERCA alone. B, proteoliposomes containing SERCA and PLN. SERCA ATPase activity was initiated by the simultaneous addition of calcium and ATP (circles; black line), addition of calcium (preincubation with ATP; triangles; gray line), or addition of ATP (preincubation with calcium; squares; gray dashed line). The lines represent curve fitting of the experimental data using the Hill equation (kinetic parameters can be found in Table 1). Each data point is the mean ± S.E. (n ≥ 4). Error bars represent S.E.

For SERCA proteoliposomes, the traditional method of initiating the reaction, simultaneous calcium and ATP addition, provided baseline values for the apparent calcium affinity, maximal activity, and cooperativity of SERCA. The values obtained (Table 1) were similar to those reported previously (31–33). Varying the starting conditions impacted the ATPase activity (Fig. 6) and the kinetic parameters determined from fitting of the Hill equation. The apparent calcium affinity varied slightly (KCa ranged from 0.26 to 0.39 μm; p < 0.01) with the highest affinity occurring when SERCA was preincubated with calcium (ATP jump). The cooperativity for calcium binding also varied (average nH of 1.6) with reduced cooperativity occurring when SERCA was preincubated with calcium (ATP jump; nH of 1.2). Finally, the maximal activity of SERCA varied the most depending on starting conditions, and this paralleled the effect on the apparent calcium affinity of SERCA. The simultaneous calcium–ATP jump had the lowest affinity and highest maximal activity, whereas the ATP jump had the highest affinity and lowest maximal activity. In fact, there was a linear correlation between KCa and maximal activity (Vmax) for the different preincubation and starting conditions (not shown).

Our usual conditions are to initiate ATPase activity by SERCA–PLN proteoliposomes with the simultaneous addition of calcium and ATP (31–33) such that we observe effects of PLN on the apparent calcium affinity (∼2-fold decrease), maximal activity (∼1.4-fold increase), and cooperativity (∼1.3-fold increase) of SERCA (condition i in Table 1). Varying these starting conditions had a minor impact on the ability of PLN to alter the apparent calcium affinity of SERCA (KCa varied from 0.82 to 0.89 μm; p < 0.01). Although the changes were small, there was a similar trend toward higher affinity when SERCA was preincubated with calcium (ATP jump; KCa of 0.82 μm). As was seen for SERCA proteoliposomes, the maximal activity varied significantly depending on starting conditions. Again, the simultaneous calcium–ATP starting condition had the lowest affinity and highest maximal activity, the ATP starting condition had the highest affinity and lowest maximal activity, and a linear correlation was observed (not shown). Finally, the largest change occurred in the cooperativity for calcium binding (nH varied from 1.3 to 2.0; p < 0.04). The loss of cooperativity occurred when SERCA was preincubated with either calcium or ATP, and this same trend was observed for pre-steady-state charge displacement (single SERCA turnover) and steady-state ATPase activity (continuous SERCA turnover). In other words, PLN inhibition increased the cooperativity for calcium binding only when SERCA was preincubated in the absence of both substrates.

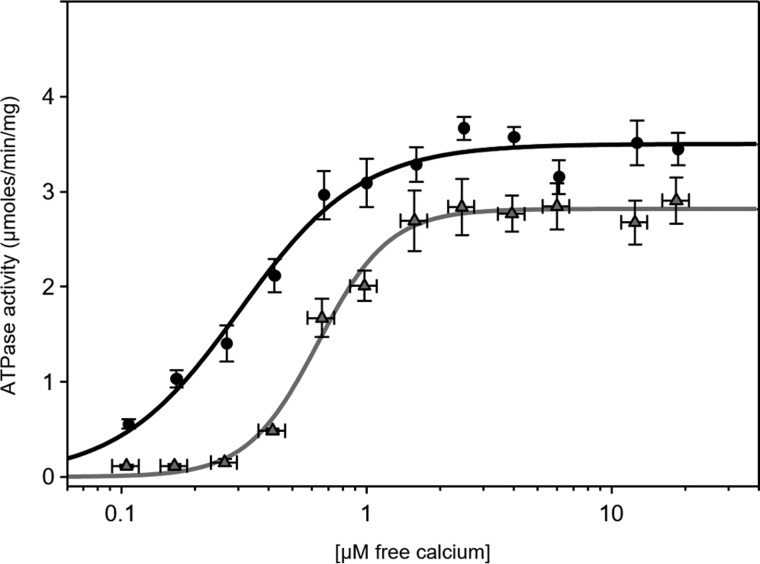

Mimicking physiological conditions

The dependence of SERCA inhibition by PLN on starting conditions prompted us to explore more physiological substrate concentrations (starting condition iv in Table 1). At rest, the substrate concentrations that SERCA experiences are low cytosolic calcium (<0.1 μm) and high ATP (1–10 mm). We preincubated SERCA and SERCA–PLN proteoliposomes with 60 nm calcium and 4 mm ATP followed by calcium jump experiments in which the addition of calcium was used to achieve various concentrations (0.1–10 μm; Fig. 7). Overall, the SERCA proteoliposomes behaved in a manner similar to the other starting conditions with comparable kinetic parameters (Table 1). However, the SERCA–PLN proteoliposomes exhibited a striking increase in cooperativity for calcium binding to SERCA. Indeed, this is the largest change in cooperativity (nH value of 3.0) observed with our SERCA–PLN proteoliposome preparation (31–33). Thus, PLN inhibition increased the cooperativity for calcium binding when SERCA was preincubated in the presence or absence of both substrates but not in the presence of individual substrates (calcium or ATP).

Figure 7.

ATPase activity as a function of Ca2+ concentration for SERCA (circles) and SERCA + PLN (triangles) proteoliposomes. To mimic physiological resting-state conditions, the proteoliposomes were preincubated with 0.06 μm calcium and 4 mm ATP. SERCA ATPase activity was initiated by the addition of the remaining calcium required to achieve 0.1–10 μm free calcium. The lines represent curve fitting of the experimental data using the Hill equation (kinetic parameters can be found in Table 1). Each data point is the mean ± S.E. (n ≥ 4). Error bars represent S.E.

Discussion

Pre-steady-state charge movement versus steady-state ATPase activity

The SERCA-dependent current transients described above reflect pre-steady-state calcium translocation across the proteoliposome membrane during the first SERCA transport cycle. The conditions tested poise SERCA in distinct conformations prior to the initiation of the SERCA transport cycle. These same conditions were tested in steady-state measurements of SERCA ATPase activity where calcium-dependent ATP hydrolysis by SERCA remained constant over time. Overall, the kinetic parameters for pre-steady-state charge movement and steady-state ATPase activity agreed well (Table 1). However, there was one notable difference: the KCa values for SERCA in the presence of PLN under calcium jump conditions. This difference may reflect the nature of the experimental measurements and incomplete coupling between calcium transport and ATP hydrolysis by SERCA (2:1 expected stoichiometry) under single turnover and continuous turnover conditions.

Conformational memory in the SERCA–PLN regulatory complex

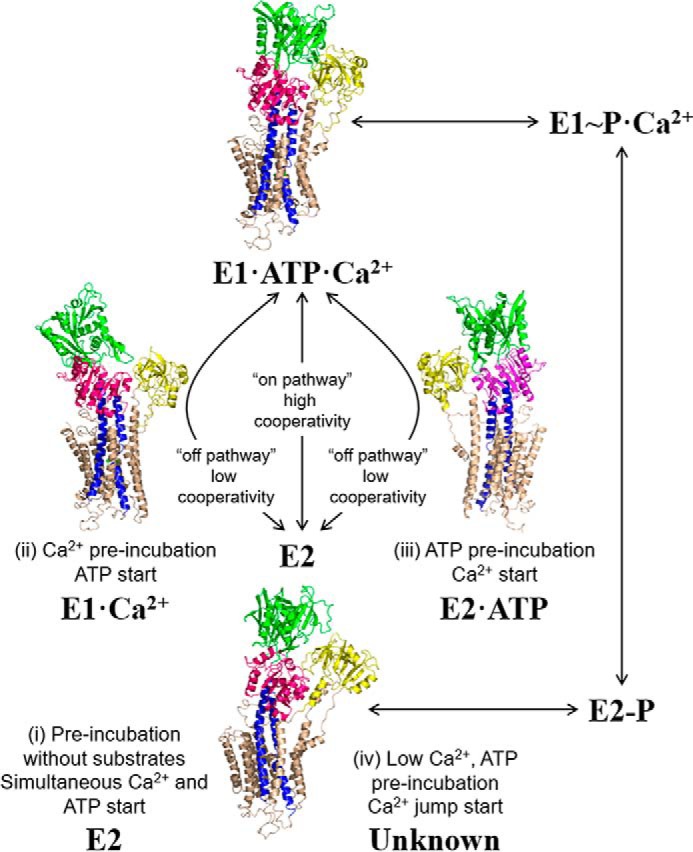

The choice of substrate conditions promotes particular conformational states of SERCA from which catalytic turnover and calcium transport can be initiated (Fig. 8). Preincubation of SERCA in the absence of substrates promotes the E2 state (42), preincubation of SERCA with calcium promotes the E1 calcium-bound state (43), and preincubation of SERCA with ATP promotes an E2 ATP-bound state (44). The SERCA conformational state that is traditionally associated with PLN inhibition is the calcium-free E2 state (6, 7). However, crystal structures of SERCA–SLN complex (9, 10) revealed a new calcium-free, magnesium-bound E1-like state. The structure of the SERCA–PLN complex is remarkably similar to this E1-like state (11), although magnesium is absent. Nonetheless, molecular models of the SERCA–PLN complex based on the calcium-free E2 state are instructive for considering the mechanism of PLN inhibition. In the absence of calcium, PLN binds in a groove formed by transmembrane helices M2, M6, and M9 of SERCA. Because this groove closes upon calcium binding, PLN alters the apparent calcium affinity of SERCA by impeding groove closure and the E2-E1 transition. This model is consistent with kinetic arguments that PLN alters the activation energy for a slow conformational change triggered by calcium binding to SERCA (45), which impacts both the apparent calcium affinity and cooperativity for calcium binding.

Figure 8.

The SERCA transport cycle with structural states relevant to the present study. The preincubation and starting conditions used herein are indicated with corresponding structures of SERCA. Shown are the calcium-free E2 state (Protein Data Bank code 1IWO), an E1-like state promoted by calcium (Protein Data Bank code 1SU4), an E2-like state promoted by ATP (Protein Data Bank code 4H1W), and a catalytically active E1-ATP-Ca2+ state (Protein Data Bank code 1T5S). For condition iv with low calcium and high ATP concentrations, PLN inhibition appears to follow the on-pathway E2 to E1 transition; however, the structural state of SERCA under these conditions is unknown.

SERCA inhibition by PLN occurred under the different starting conditions (Figs. 4–7), although the kinetic effects and nature of PLN inhibition depended on how SERCA was poised before the initiation of transport. The most significant change occurred in the cooperativity for calcium binding, reflected by the large change in Hill coefficients across the different preincubation conditions (Table 1). In the absence of substrates or under physiological substrate conditions (low calcium and high ATP), PLN strongly increased the cooperativity for calcium binding. The theoretical limit for the Hill coefficient is 2 (two Ca2+ ions transported per SERCA molecule); however, we observed a value of 3 (nH of 3.0). The simplest explanation for this is substrate- and PLN-dependent coupling between SERCA molecules (46). Nonetheless, these conditions promote an “on-pathway” reaction trajectory from the E2 calcium-free state to the E1-ATP-Ca2+ state of SERCA such that PLN induces a strongly cooperative transition between the calcium-free and calcium-bound states (Fig. 8). The substrate-free condition promotes the E2 state of SERCA, which requires a large multidomain conformational change to form the catalytically active E1-ATP-Ca2+ state (42). Thus, PLN stabilization of the E2 state of SERCA offers a plausible explanation for the increase in cooperativity: PLN lowers the probability of binding the first calcium ion, but once binding occurs there is a higher probability for binding the second calcium ion. The increased cooperativity was also observed under more physiological substrate conditions (low calcium and high ATP), suggesting a common structural basis. However, the conformational state of SERCA under these latter conditions is unknown.

In an opposite trend, there was reduced cooperativity for calcium binding when SERCA was preincubated with either calcium or ATP. Again, this same observation occurred in pre-steady-state charge displacement (condition i versus condition iii; nH decreased from 1.8 to 1.1; p < 0.025) and steady-state ATPase activity (condition i versus condition iii; nH decreased from 2.0 to 1.3; p < 0.04). The following question then arises: what causes the reduced cooperativity when SERCA is preincubated with either ATP or calcium in the presence of PLN? Because only a single substrate is present, these conditions are described as an “off-pathway” reaction trajectory from the E2 calcium-free state to the catalytically active E1-ATP-Ca2+ state of SERCA. Calcium promotes the E1 calcium-bound state in a concentration-dependent manner. Although this offers an explanation for the reduced cooperativity, PLN can still alter the apparent calcium affinity of SERCA. In contrast, ATP alone promotes an E2 ATP-bound state; however, the reduced cooperativity suggests that SERCA adopts a conformation more compatible with calcium binding. These characteristics are reminiscent of the novel E1-like state identified in crystal structures of the SERCA–SLN (9, 10) and SERCA–PLN (11) complexes. In this state, the calcium-binding sites are formed and exposed to the cytoplasm. PLN stabilization of this E1-like state offers a plausible explanation for the reduced cooperativity for calcium binding to SERCA: the conformational transition that establishes cooperativity and forms the calcium-binding sites has already occurred. In the crystal structures of the SERCA-SLN complex (9, 10), magnesium ions stabilize the calcium sites in the E1-like state. This offers an explanation for PLN inhibition and the decrease in the apparent calcium affinity of SERCA: magnesium ions must be displaced before calcium can bind. This latter point is consistent with the effects of the higher magnesium concentration (5 mm) on pre-steady-state charge displacement by SERCA–PLN proteoliposomes (Fig. 3).

Overall, our observations support the concept that PLN can establish an inhibitory interaction with multiple SERCA conformational states, minimally a calcium-free E2 state and a more E1-like state. We hypothesize that the calcium-free inhibitory state is the canonical complex as depicted by molecular modeling (6, 7) and that the E1-like inhibitory state is represented by the more recent crystals structures (9–11). Furthermore, once these modes of PLN interaction are established, they persist through multiple cycles of SERCA transport. If SERCA transport activity is initiated in the absence of substrates, PLN establishes and retains the ability to interact with the E2 state of SERCA through multiple turnover events (effect on both KCa and nH). Instead, if SERCA is preincubated with ATP or calcium, PLN establishes and retains the ability to interact with an E1-like state of SERCA through multiple turnover events (effect only on KCa). More importantly, PLN does not appear to access the E2 state of SERCA under these conditions. Recall that resting conditions in cardiac muscle are typically associated with low calcium (<0.1 μm) and high ATP (1–10 mm) and magnesium (∼2 mm) concentrations.

SERCA is a molecular machine that carries out the complex functions of ATP hydrolysis and active calcium transport. To achieve this, SERCA undergoes plastic deformations and large domain movements enabled by flexibility and spontaneous conformational fluctuations (47). However, the transition between different conformational states is not random but instead is driven by the availability of substrates and the suppression of backward transitions. PLN regulates SERCA by altering the transition between the E2 and E1 conformational states, which manifests as a decrease in SERCA's calcium affinity. Herein, our data are consistent with conformational memory (36) in the SERCA–PLN regulatory complex. The SERCA–PLN complex attains distinct structural states depending on substrate conditions (Fig. 8), and these states are retained during SERCA catalytic turnover and conformational cycling. In other words, there are multiple modes of interaction between SERCA and PLN, and once a particular mode of interaction is engaged it remains throughout the SERCA calcium transport cycle and multiple turnover events.

Experimental procedures

Co-reconstitution of SERCA and recombinant PLN or SLN

Human PLN and SLN were expressed and purified as described (48). Peptides were confirmed by DNA sequencing (TAGC Sequencing, University of Alberta) and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Alberta Proteomics and Mass Spectrometry Facility, University of Alberta). SERCA1a was purified from rabbit skeletal muscle SR (49, 50) and co-reconstituted with PLN and SLN as described (15, 31). The purified proteoliposomes yielded a final molar ratio of 1 SERCA:4.5 PLN (or SLN):∼120 lipids. For the calculation of specific activity, the SERCA, PLN, and SLN concentrations were determined by quantitative SDS-PAGE (29).

Electrical measurements

All current measurements were performed with the SURFE2ROne device (Nanion Technologies, Munich, Germany). The temperature was maintained at ∼23 °C. Charge movement was measured by adsorbing proteoliposomes containing (i) SERCA, (ii) SERCA and PLN, or (iii) SERCA and SLN onto a hybrid alkane thiol/phospholipid bilayer anchored to a gold electrode (SSM; Fig. 1) (26, 51). Once the proteoliposomes were adsorbed, SERCA was activated by a concentration jump of a suitable substrate (e.g. ATP). If the substrate concentration jump induces charge displacement across the membrane, a current transient can be recorded due to capacitive coupling between the proteoliposome and SSM (27, 34). The numerically integrated current transient is related to the net charge movement in the proteoliposomes, which depends upon the electrogenic calcium translocation by SERCA. Our premise is that the SSM technique detects pre-steady-state current transients within the first catalytic cycle of SERCA and that it is not sensitive to stationary currents following the first cycle (27, 34, 52).

For the ATP concentration jump experiments, “non-activating” and “activating” buffered solutions were used. The non-activating solution contained 100 mm KCl, 0.25 mm EGTA, 0.2 mm DTT, 1 mm MgCl2, 25 mm MOPS (pH 7.0), and various concentrations of CaCl2 (0.1–10 μm free Ca2+; as calculated by the WinMAXC program (53); e.g. control measurements utilized 0.25 mm CaCl2 to achieve 10 μm free Ca2+). The activating solution was identical except for addition of 100 μm ATP. To prevent calcium accumulation into proteoliposomes, 1 μm calcium ionophore (A23187; calcimycin) was used. In inhibition experiments, SERCA was preincubated with 100 nm thapsigargin for 10 min. The ATP-induced current signal observed in the absence and presence of thapsigargin was then compared.

To verify the reproducibility of the current transients on the same SSM, each single measurement was repeated five times and then averaged to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. Standard deviations did not exceed 5%. At the beginning and end of a concentration jump experiment, initial and final control measurements (i.e. 100 μm ATP jumps in the presence of 10 μm free Ca2+) were carried out. This allowed comparison of maximum current transients at the start and end of each experiment and the detection of signal deterioration during the time course of each experiment (e.g. due to protein degradation or loss of proteoliposome adsorption). Each set of measurements was reproduced using four to six different gold sensors.

ATPase activity assays

Calcium-dependent ATPase activities of the co-reconstituted proteoliposomes were measured by a coupled enzyme assay (54). The coupled enzyme assay reagents were of the highest purity available (Sigma-Aldrich). The proteoliposomes contained SERCA alone, SERCA in the presence of PLN, or SERCA in the presence of SLN. A minimum of three independent reconstitutions and activity assays were performed for each set of proteoliposomes, and the calcium-dependent ATPase activity was measured over a wide range of calcium concentrations (0.1–10 μm). The assay was adapted to a 96-well format utilizing a BioTek Synergy 4 hybrid microplate reader (340-nm wavelength; 150-μl volume; 10–20 nm SERCA/well; 30 °C; data points collected every 39 s for 1 h). The reactions were initiated by (i) the simultaneous addition of calcium and ATP (preincubation of the proteoliposomes without calcium or ATP), (ii) the addition of ATP (preincubation of the proteoliposomes with calcium), or (iii) the addition of calcium (preincubation of the proteoliposomes with ATP). The KCa, Vmax, and nH were calculated based on non-linear least-squares fitting of the activity data to the Hill equation using Sigma Plot software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Errors were calculated as the standard error of the mean for a minimum of three independent measurements. Comparison of KCa, Vmax, and nH parameters was carried out using analysis of variance (between-subjects, one-way) followed by the Holm-Sidak test for pairwise comparisons (Sigma Plot).

Author contributions

S. S. and G. P. A. acquired the data, analyzed the results, and revised the article critically for important intellectual content. J. J. B. assisted in data acquisition and analysis. M. J. L. and M. R. M. edited the article and revised it critically for important intellectual content. H. S. Y. and F. T.-B. made substantial contributions to the conception, experimental design, and interpretation of results. H. S. Y. and F. T.-B. drafted the article and revised it critically for important intellectual content.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Paul Lapointe, Rebecca Mercier, and Annemarie Wolmarans for technical assistance.

This work was supported by Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze and Programma Operativo Regione Toscana (POR) - Competitività Regionale e Occupazione (CRO) - Fondo Sociale Europeo (FSE) 2007-2013 (to S. S., M. R. M., and F. T.-B.), the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (to H. S. Y.), and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada-Collaborative Research and Training Experience program and the International Research Training Group in Membrane Biology (to G. P. A.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Table S1.

- SR

- sarcoplasmic reticulum

- SERCA

- sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase

- PLN

- phospholamban

- SLN

- sarcolipin

- SSM

- solid-supported membrane

- KCa

- calcium concentration at half-maximal activity.

References

- 1. Toyoshima C. (2009) How Ca2+-ATPase pumps ions across the sarcoplasmic reticulum membrane. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1793, 941–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Toyoshima C., and Cornelius F. (2013) New crystal structures of PII-type ATPases: excitement continues. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 23, 507–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Møller J. V., Olesen C., Winther A. M., and Nissen P. (2010) The sarcoplasmic Ca2+-ATPase: design of a perfect chemi-osmotic pump. Q Rev. Biophys. 43, 501–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Meis L., and Vianna A. L. (1979) Energy interconversion by the Ca-dependent ATPase of the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 48, 275–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jones L. R., Cornea R. L., and Chen Z. (2002) Close proximity between residue 30 of phospholamban and cysteine 318 of the cardiac Ca2+ pump revealed by intermolecular thiol cross-linking. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 28319–28329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Toyoshima C., Asahi M., Sugita Y., Khanna R., Tsuda T., and MacLennan D. (2003) Modeling of the inhibitory interaction of phospholamban with the Ca2+ ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 467–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seidel K., Andronesi O. C., Krebs J., Griesinger C., Young H. S., Becker S., and Baldus M. (2008) Structural characterization of Ca2+-ATPase-bound phospholamban in lipid bilayers by solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Biochemistry 47, 4369–4376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gustavsson M., Traaseth N. J., and Veglia G. (2011) Activating and deactivating roles of lipid bilayers on the Ca2+-ATPase/phospholamban complex. Biochemistry 50, 10367–10374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Winther A. M., Bublitz M., Karlsen J. L., Møller J. V., Hansen J. B., Nissen P., and Buch-Pedersen M. J. (2013) The sarcolipin-bound calcium pump stabilizes calcium sites exposed to the cytoplasm. Nature 495, 265–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Toyoshima C., Iwasawa S., Ogawa H., Hirata A., Tsueda J., and Inesi G. (2013) Crystal structures of the calcium pump and sarcolipin in the Mg2+-bound E1 state. Nature 495, 260–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Akin B. L., Hurley T. D., Chen Z., and Jones L. R. (2013) The structural basis for phospholamban inhibition of the calcium pump in sarcoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 30181–30191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tada M., Kirchberger M. A., and Katz A. M. (1976) Regulation of calcium transport in cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. Recent Adv. Stud. Cardiac Struct. Metab. 9, 225–239 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bilezikjian L. M., Kranias E. G., Potter J. D., and Schwartz A. (1981) Studies on phosphorylation of canine cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum by calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Circ. Res. 49, 1356–1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Catalucci D., Latronico M. V., Ceci M., Rusconi F., Young H. S., Gallo P., Santonastasi M., Bellacosa A., Brown J. H., and Condorelli G. (2009) Akt increases sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ cycling by direct phosphorylation of phospholamban at Thr17. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 28180–28187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gorski P. A., Glaves J. P., Vangheluwe P., and Young H. S. (2013) Sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA) inhibition by sarcolipin is encoded in its luminal tail. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 8456–8467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sahoo S. K., Shaikh S. A., Sopariwala D. H., Bal N. C., and Periasamy M. (2013) Sarcolipin protein interaction with sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) is distinct from phospholamban protein, and only sarcolipin can promote uncoupling of the SERCA pump. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 6881–6889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bal N. C., Maurya S. K., Sopariwala D. H., Sahoo S. K., Gupta S. C., Shaikh S. A., Pant M., Rowland L. A., Bombardier E., Goonasekera S. A., Tupling A. R., Molkentin J. D., and Periasamy M. (2012) Sarcolipin is a newly identified regulator of muscle-based thermogenesis in mammals. Nat. Med. 18, 1575–1579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chu G., Li L., Sato Y., Harrer J. M., Kadambi V. J., Hoit B. D., Bers D. M., and Kranias E. G. (1998) Pentameric assembly of phospholamban facilitates inhibition of cardiac function in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 33674–33680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Glaves J. P., Trieber C. A., Ceholski D. K., Stokes D. L., and Young H. S. (2011) Phosphorylation and mutation of phospholamban alter physical interactions with the sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium pump. J. Mol. Biol. 405, 707–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smeazzetto S., Tadini-Buoninsegni F., Thiel G., Berti D., and Montis C. (2016) Phospholamban spontaneously reconstitutes into giant unilamellar vesicles where it generates a cation selective channel. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 1629–1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kovacs R. J., Nelson M. T., Simmerman H. K., and Jones L. R. (1988) Phospholamban forms Ca2+-selective channels in lipid bilayers. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 18364–18368 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smeazzetto S., Schröder I., Thiel G., and Moncelli M. R. (2011) Phospholamban generates cation selective ion channels. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 12935–12939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bidwell P., Blackwell D. J., Hou Z., Zima A. V., and Robia S. L. (2011) Phospholamban binds with differential affinity to calcium pump conformers. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 35044–35050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li J., James Z. M., Dong X., Karim C. B., and Thomas D. D. (2012) Structural and functional dynamics of an integral membrane protein complex modulated by lipid headgroup charge. J. Mol. Biol. 418, 379–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gustavsson M., Verardi R., Mullen D. G., Mote K. R., Traaseth N. J., Gopinath T., and Veglia G. (2013) Allosteric regulation of SERCA by phosphorylation-mediated conformational shift of phospholamban. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 17338–17343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pintschovius J., and Fendler K. (1999) Charge translocation by the Na+/K+-ATPase investigated on solid supported membranes: rapid solution exchange with a new technique. Biophys. J. 76, 814–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tadini-Buoninsegni F., Bartolommei G., Moncelli M. R., Guidelli R., and Inesi G. (2006) Pre-steady state electrogenic events of Ca2+/H+ exchange and transport by the Ca2+-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 37720–37727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reddy L. G., Jones L. R., Pace R. C., and Stokes D. L. (1996) Purified, reconstituted cardiac Ca2+-ATPase is regulated by phospholamban but not by direct phosphorylation with Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 14964–14970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Young H. S., Jones L. R., and Stokes D. L. (2001) Locating phospholamban in co-crystals with Ca2+-ATPase by cryoelectron microscopy. Biophys. J. 81, 884–894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Andronesi O. C., Becker S., Seidel K., Heise H., Young H. S., and Baldus M. (2005) Determination of membrane protein structure and dynamics by magic-angle-spinning solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 12965–12974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Trieber C. A., Douglas J. L., Afara M., and Young H. S. (2005) The effects of mutation on the regulatory properties of phospholamban in co-reconstituted membranes. Biochemistry 44, 3289–3297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Trieber C. A., Afara M., and Young H. S. (2009) Effects of phospholamban transmembrane mutants on the calcium affinity, maximal activity, and cooperativity of the sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium pump. Biochemistry 48, 9287–9296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ceholski D. K., Trieber C. A., and Young H. S. (2012) Hydrophobic imbalance in the cytoplasmic domain of phospholamban is a determinant for lethal dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 16521–16529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tadini-Buoninsegni F., Bartolommei G., Moncelli M. R., Tal D. M., Lewis D., and Inesi G. (2008) Effects of high-affinity inhibitors on partial reactions, charge movements, and conformational States of the Ca2+ transport ATPase (sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase). Mol. Pharmacol. 73, 1134–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tadini-Buoninsegni F., Moncelli M. R., Peruzzi N., Ninham B. W., Dei L., and Nostro P. L. (2015) Hofmeister effect of anions on calcium translocation by sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. Sci. Rep. 5, 14282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schörner M., Beyer S. R., Southall J., Cogdell R. J., and Köhler J. (2015) Conformational memory of a protein revealed by single-molecule spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 13964–13970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gorski P. A., Trieber C. A., Ashrafi G., and Young H. S. (2015) Regulation of the sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium pump by divergent phospholamban isoforms in zebrafish. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 6777–6788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ji Y., Loukianov E., Loukianova T., Jones L. R., and Periasamy M. (1999) SERCA1a can functionally substitute for SERCA2a in the heart. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 276, H89–H97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Loukianov E., Ji Y., Grupp I. L., Kirkpatrick D. L., Baker D. L., Loukianova T., Grupp G., Lytton J., Walsh R. A., and Periasamy M. (1998) Enhanced myocardial contractility and increased Ca2+ transport function in transgenic hearts expressing the fast-twitch skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. Circ. Res. 83, 889–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sagara Y., and Inesi G. (1991) Inhibition of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transport ATPase by thapsigargin at subnanomolar concentrations. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 13503–13506 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Odermatt A., Becker S., Khanna V. K., Kurzydlowski K., Leisner E., Pette D., and MacLennan D. H. (1998) Sarcolipin regulates the activity of SERCA1, the fast-twitch skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 12360–12369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Toyoshima C., and Nomura H. (2002) Structural changes in the calcium pump accompanying the dissociation of calcium. Nature 418, 605–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Toyoshima C., Nakasako M., Nomura H., and Ogawa H. (2000) Crystal structure of the calcium pump of sarcoplasmic reticulum at 2.6 Å resolution. Nature 405, 647–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Toyoshima C., Yonekura S., Tsueda J., and Iwasawa S. (2011) Trinitrophenyl derivatives bind differently from parent adenine nucleotides to Ca2+-ATPase in the absence of Ca2+. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 1833–1838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cantilina T., Sagara Y., Inesi G., and Jones L. R. (1993) Comparative studies of cardiac and skeletal sarcoplasmic reticulum ATPases: effect of phospholamban antibody on enzyme activation. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 17018–17025 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Blackwell D. J., Zak T. J., and Robia S. L. (2016) Cardiac calcium ATPase dimerization measured by cross-linking and fluorescence energy transfer. Biophys. J. 111, 1192–1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Inesi G., Lewis D., Toyoshima C., Hirata A., and de Meis L. (2008) Conformational fluctuations of the Ca2+-ATPase in the native membrane environment. Effects of pH, temperature, catalytic substrates, and thapsigargin. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 1189–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Douglas J. L., Trieber C. A., Afara M., and Young H. S. (2005) Rapid, high-yield expression and purification of Ca2+-ATPase regulatory proteins for high-resolution structural studies. Protein Expr. Purif. 40, 118–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Eletr S., and Inesi G. (1972) Phospholipid orientation in sarcoplasmic reticulum membranes: spin-label ESR and proton NMR studies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 282, 174–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Stokes D. L., and Green N. M. (1990) Three-dimensional crystals of Ca-ATPase from sarcoplasmic reticulum: symmetry and molecular packing. Biophys. J. 57, 1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tadini Buoninsegni F., Bartolommei G., Moncelli M. R., Inesi G., and Guidelli R. (2004) Time-resolved charge translocation by sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca-ATPase measured on a solid supported membrane. Biophys. J. 86, 3671–3686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ferrandi M., Barassi P., Tadini-Buoninsegni F., Bartolommei G., Molinari I., Tripodi M. G., Reina C., Moncelli M. R., Bianchi G., and Ferrari P. (2013) Istaroxime stimulates SERCA2a and accelerates calcium cycling in heart failure by relieving phospholamban inhibition. Br. J. Pharmacol. 169, 1849–1861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Patton C., Thompson S., and Epel D. (2004) Some precautions in using chelators to buffer metals in biological solutions. Cell Calcium 35, 427–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Warren G. B., Toon P. A., Birdsall N. J., Lee A. G., and Metcalfe J. C. (1974) Reconstitution of a calcium pump using defined membrane components. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 71, 622–626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.