Abstract

Stability of intrinsic electrical activity and modulation of input-output gain are both important for neuronal information processing. It is therefore of interest to define biologically plausible parameters that allow these two features to coexist. Recent experiments indicate that in some biological neurons, the stability of spontaneous firing can arise from coregulated expression of the electrophysiologically opposing IA and IH currents. Here, I show that such balanced changes in IA and IH dramatically alter the slope of the relationship between the firing rate and driving current in a Hodgkin-Huxley-type model neuron. Concerted changes in IA and IH can thus control neuronal gain while preserving intrinsic activity.

1. Introduction

Maintaining stable intrinsic activity patterns in the absence of relevant stimuli is thought to be important for proper information processing in neurons and neural circuits (Turrigiano & Nelson, 2000; Davis & Bezproznanny, 2001; Marder & Prinz, 2002). But the ability of neurons to change gain, that is, to alter the slope of the relationship between driving stimulus and firing response, is also critical for computation in diverse neural systems (Salinas & Thier, 2000; Salinas & Sejnowski, 2001). It is therefore of interest to define biologically plausible parameters that allow the gain of a neuron to be modulated without changes in its intrinsic (stimulus-independent) activity. It was recently demonstrated, using biological and model neurons, that one of the ways to achieve such “silent” modulation of gain is by covarying the frequencies of excitatory and inhibitory background synaptic input currents (Chance, Abbott, & Reyes, 2002). Another recent report indicated that biological neurons can intrinsically covary the magnitudes of certain excitatory and inhibitory ionic currents: increasing the expression of the transient outward current (IA) led to proportional increases in hyperpolarization-activated inward current (IH) in lobster somatogastric neurons (MacLean, Zhang, Johnson, & Harris-Warrick, 2003). This biological coregulation of IA and IH did not result in significant changes in intrinsic firing properties (MacLean et al., 2003). Therefore, this note addresses the question of whether the concerted changes in IA and IH can act as a cellular mechanism for “silent” gain modulation.

2. Results and Discussion

To explore the effects of concerted changes in IA and IH on neuronal gain, a recently published model of lobster somatogastric neurons (Prinz, Thirumalai, & Marder, 2003) was used. This is a Hodgkin-Huxley-type, single-compartment model that comprises seven membrane currents (INa, ICaS, IA, IKCa, IKd, IH, and Ileak) and an intracellular calcium buffer, and exhibits tonic intrinsic firing (Prinz et al., 2003). All maximal conductances (except those for IA and IH, which were varied as indicated) were as in Prinz et al., and simulations were performed using MATLAB stiff systems numerical integrator ode15s, at time resolution of 25 µs.

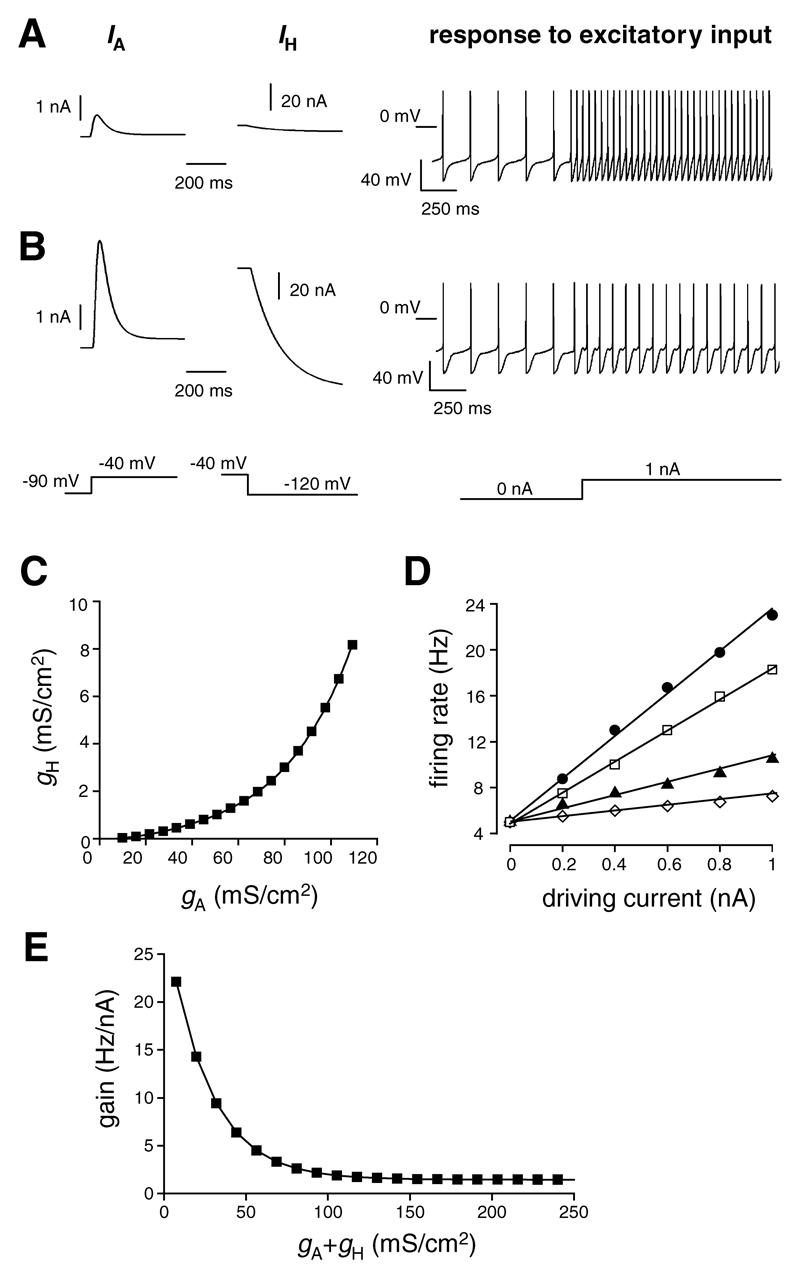

The maximal conductances (g) of IA and IH were changed from the values in Prinz et al. (10 and 0.05 mS/cm2, respectively) in such a way so as to keep the intrinsic firing characteristics (tonic pattern and firing frequency) unaltered. The relationship between the two conductances for the latter condition is shown in Figure 1C. Changes in gA and gH markedly altered the firing responses of the model neuron to a tonic excitatory current: balanced increases in gA and gH decreased the firing response (see Figures 1A and 1B). This implies that the concerted changes in gA and gH selectively altered the gain, since the tonic nature of firing and the firing frequency remained unaffected.

Figure 1.

(A, B) Examples of simulations illustrating that concerted changes in IA and IH affect neuronal gain without changes in unstimulated firing rate or pattern. (A) Neuron with a small IA and IH (gA and gH are 10 and 0.05 mS/cm2, respectively) responds to a tonic excitatory current with a large increase in firing rate. (B) Increasing IA and IH in a balanced manner that leaves unstimulated firing unaltered (here, gA and gH are 50 and 1 mS/cm2, respectively) leads to a marked reduction of the firing response to the same excitatory current. Simulation protocols used to elicit IA, IH, and firing responses in A and B are shown schematically below the corresponding traces. (C) The relationship between gA and gH that satisfies the condition of unaltered intrinsic firing characteristics. (D) Examples of f-I relationships of neurons with different balanced combinations of gA and gH (respectively, in mS/cm2: black circles = 10 and 0.05, white squares = 20 and 0.18, black triangles = 50 and 1, white diamonds = 100 and 6). (E) Gain values (the slopes of f-I relationships such as those shown in D) plotted against the sum of gA and gH for combinations of gA and gH that do not alter intrinsic firing characteristics.

To quantify the changes in gain in a simplified but plausible way, the firing rate (f) was plotted against the driving excitatory current (I) for a range of combinations of gA and gH that resulted in the same intrinsic firing rate. The balanced increases in gA and gH led to progressive decreases in the gain (slope) of the f-I relationship (see Figure 1D). The gain was altered most steeply when the sum of gA and gH was below 100 mS/cm2 (see Figure 1E); this conductance range is consistent with physiological gA and gH values in lobster somatogastric neurons (MacLean et al., 2003; Prinz et al., 2003). Decreases in gain saturated when the sum of gA and gH exceeded about 100 mS/cm2 (see Figure 1E).

These results indicate that concerted changes in IA and IH may allow neurons to vary gain while preserving intrinsic activity patterns. To the best of my knowledge, such cellular mechanism of gain control has not been previously reported. This mechanism is biologically plausible (MacLean et al., 2003), and could potentially be of general physiological importance considering that IA and IH are expressed together in many types of biological neurons and are under the control of a variety of neuromodulators (Yang et al., 2001; Ramakers & Storm, 2002; Schweitzer, Madamba, & Siggins, 2003; Frere & Luthi, 2004).

References

- Chance FS, Abbott LF, Reyes AD. Gain modulation from background synaptic input. Neuron. 2002;35(4):773–782. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00820-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GW, Bezprozvanny I. Maintaining the stability of neural function: A homeostatic hypothesis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:847–869. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frere SG, Luthi A. Pacemaker channels in mouse thalamocortical neurons are regulated by distinct pathways of cAMP synthesis. J Physiol. 2004;554:111–125. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.050989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean JN, Zhang Y, Johnson BR, Harris-Warrick RM. Activity-independent homeostasis in rhythmically active neurons. Neuron. 2003;37(1):109–120. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E, Prinz AA. Modeling stability in neuron and network function: The role of activity in homeostasis. Bioessays. 2002;24(12):1145–1154. doi: 10.1002/bies.10185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz AA, Thirumalai V, Marder E. The functional consequences of changes in the strength and duration of synaptic inputs to oscillatory neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23(3):943–954. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00943.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakers GM, Storm JF. A postsynaptic transient K(+) current modulated by arachidonic acid regulates synaptic integration and threshold for LTP induction in hippocampal pyramidal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(15):10144–10149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152620399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas E, Sejnowski TJ. Gain modulation in the central nervous system: Where behavior, neurophysiology, and computation meet. Neuroscientist. 2001;7(5):430–440. doi: 10.1177/107385840100700512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas E, Thier P. Gain modulation: A major computational principle of the central nervous system. Neuron. 2000;27(1):15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer P, Madamba SG, Siggins GR. The sleep-modulating peptide cortistatin augments the H-current in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23(34):10884–10891. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-34-10884.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano GG, Nelson SB. Hebb and homeostasis in neuronal plasticity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10(3):358–364. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00091-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Feng L, Zheng F, Johnson SW, Du J, Shen L, Wu CP, Lu B. GDNF acutely modulates excitability and A-type K(+) channels in midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4(11):1071–1078. doi: 10.1038/nn734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]