Abstract

A series of potent and selective D3 receptor (D3R) analogues with diazaspiro alkane cores were synthesized. Radioligand binding of compounds 11, 14, 15a, and 15c revealed favorable D3R affinity (Ki = 122–25.6 nM) and were highly selective for D3R vs D3R (ranging from 264–905-fold). Variation of these novel ligand architectures can be achieved using our previously reported 10–20 minute benchtop C–N cross-coupling methodology, affording a broad range of arylated diazaspiro pre-cursors.

Keywords: If you are submitting your paper to a journal that requires keywords, provide significant keywords to aid the reader in literature retrieval

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Dopamine is a crucial neurotransmitter that acts by stimulating G-protein coupled receptors responsible for many neurological processes such as emotion, reward, and motivation.1 These receptors are classified into two subtypes, D1-like and D2-like, based on sequence identity and similarity in signal transduction. The D2-like dopamine D3 receptor (D3R) is a protein of interest for various neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders including schizophrenia, Parkinson’s disease, dementia, anxiety and depression.2–5 The high appeal of the D3R stems from the high density of its expression within the mesolimbic pathway of the CNS.6–9 This region of the brain is responsible for the reward and motivational mechanisms associated with drug addition, thus, making the D3R an attractive target for pharmacological therapy in substance abuse disorders (SUD).10–13 However, the similarities shared between the D3R and D2R, such as an overall ~46% amino acid sequence homology, a 78% sequence identity within the transmembrane-spanning segments,14 and the near-identical binding site residues of these receptors,15 have made the development of a FDA approved D3R selective therapeutic quite challenging.

Many previously reported ligand architectures designed to selectively target the D3R employ the classic arylpiperazine amino template to enhance ligand affinity to the receptor (1–3, Figure 1).2, 16 In 2010, Reichert and co-workers used computational modeling to illustrate the extensive interactions between the amino component of the ligand and the D3R orthosteric binding site (OBS).17 Their modeling experiments indicated ligand binding efficacy is due to a salt bridge formation between the Asp3.32 of the receptor and the protonated nitrogen on the amino moiety. This binding interaction was later confirmed in the D3R crystal structure, with later reports correlating ligand affinity to OBS interactions, and D3R selectivity to secondary binding pocket interactions.18 As a result, these molecular determinants provide a challenging path for medicinal chemists to develop potent and selective D3R ligand scaffolds with amino moiety alternatives to the arylpiperazine pharmacophore.19

Figure 1.

Chemical structure and binding data of D3R selective antagonists as reported in the literature.

Over the past several years, reports have emerged with 1,2,4-triazole-based scaffolds with notable D3R vs. D2R efficacy and selectiviy.1, 11, 20 GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) disclosed several 1,2,4-triazole-based compounds with excellent D3R affinity and selectivity profiles,21–23 most notably, GSK598,809 (4), the first D3R selective antagonist to exhibit clinical evidence as a potential therapeutic for substance abuse disorders.24 More recently, Micheli and co-workers reported a D3R antagonist with an azaspiro alkane moiety (5), which displays sub-nanomolar affinity and excellent D3R selectivity over the D2R.25 Encouraged by these reports, we designed a new class of thiotriazole D3R selective scaffolds using commercially available diazaspiro alkanes A–H (Figure 2) as modified amino cores. Spiro synthons provide spatial modifications that are otherwise non-accessible to saturated six-membered rings such as piperazine, thus, affording unique interactions in the D3R binding pocket. Moreover, spirocyclic compounds exhibit lower lipophilicity compared to their monocyclic counterparts, resulting in increased bioavailability.26, 27 Herein we report the synthesis and in vitro studies of diazaspiro-containing 1,2,4-triazole-3-thiol ligand systems.

Figure 2.

Diazaspiro compounds evaluated as amino cores.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Initial synthesis of the target compounds began with arylation of amino cores A–H outlined in Scheme 1. Arylated diazaspiro synthons (I) and 6 were afforded in high yields in just 10–20 min following our previously reported one-pot Pd C–N cross-coupling methodology.28, 29 This catalytic protocol can be conducted under aerobic conditions, thus eliminating the need for an inert atmosphere or anhydrous solvents.

Scheme 1.

aReagents and conditions: (a) Pd2(dba)3, RuPhos, aryl halide, A–H, NaOt-Bu, dioxane, 100 °C, 20 min; (b) TFA, DCM, RT, 3h.

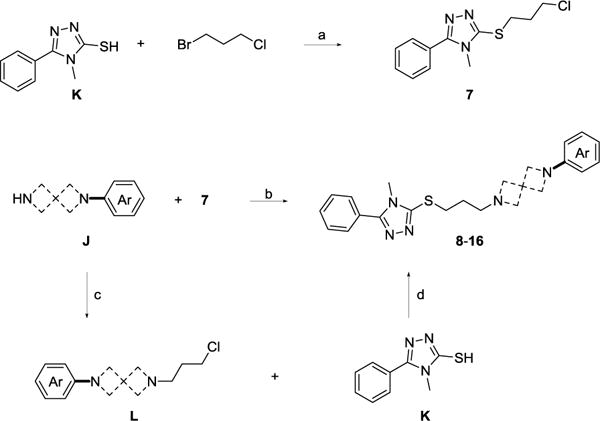

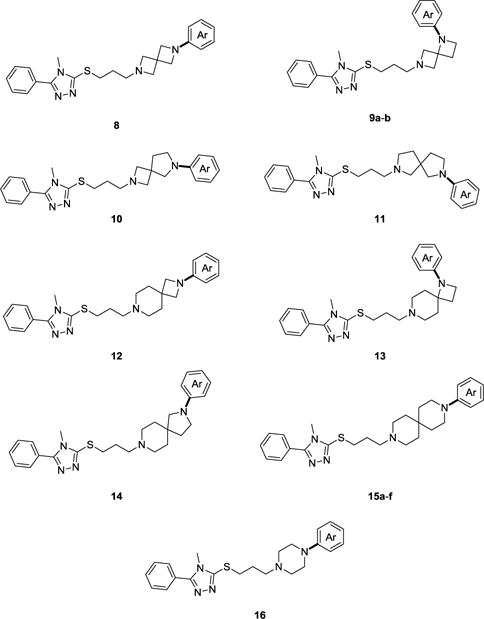

S-Alkylation of K with 1-bromo-3-chloropropane afforded 7 in high yield (92%) using a modified synthetic route from a previous report (Scheme 2).30 Compound 7 was then reacted with the appropriate arylated diazaspiro free amine intermediate (J) to form derivatives 8–16 illustrated in Figure 3. Target compounds can also be developed using the alternative synthetic route depicted in Scheme 2, by reacting the appropriate alkylated intermediate L with K in the presence of trimethylamine in ethanol.

Scheme 2.

aReagents and conditions: (a) 1-bromo-3-chloropropane, K2CO3, acetone, RT, 20 h; (b) Cs2CO3, ACN, 70 °C, 12 h; (c) 1-bromo-3-chloropropane, K2CO3, acetone, RT, 20 h; (d) TEA, EtOH, 75 °C, 12 h.

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of synthesized target compounds.

Our initial radioligand binding studies revealed diazaspirocycles A–B as poor amino core candidates in the 1,2,4-triazole scaffold (Table 1, compounds 8–9). Attempts to improve D3R efficacy with B were also unsuccessful with ortho-substituted fluorobenzene, resulting in diminished D3R affinity of 9b. Binding activity and selectivity improved with 10, containing slightly bulkier core C, when compared to A and B. When investigating D in compound 11, we observed moderate affinity (Ki = 24.2 nM) and good selectivity (D3R/D3R = 264) at the D3R. Replacing D with amino cores E and F resulted in lower D3R potency and selectivity compared to 11. Compounds 13 and 14, however, displayed more promising binding profiles than 8–9, scaffolds also with azetidine containing diazaspiro cores (A–C).

Table 1.

D3 and D2 Receptor Binding Affinities of Diazaspiro Analoguesa

| Compound | Ar | Kib ± SEM (nM) | D3R/D2R Ratioe | cLog Pf | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D3Rc | D2Rd | ||||

| 8 | 2−OCH3 | 833 ± 154 | 21,216 ± 4,636 | 25.5 | 3.95 |

| 9a | 2-OCH3 | 4,790 ± 280 | 114,945 ± 31,960 | 24.0 | 3.85 |

| 9b | 4-F | 18,1888 ± 2,284 | >109,574 ± NA | >6.0 | 4.23 |

| 10 | 2-OCH3 | 192 ± 2.3 | 60,152 ± 13,327 | 313 | 3.90 |

| 11(rac)g | 2-OCH3 | 24.2 ± 5.6 | 6,370 ± 1,145 | 264 | 4.16 |

| 12 | 2-OCH3 | 235 ± 41.1 | 37,579 ± 1,806 | 160 | 3.76 |

| 13 | 2-OCH3 | 169 ± 20.2 | 29,300 ± 3,139 | 173 | 3.76 |

| 14 | 2-OCH3 | 19.6 ± 4.7 | 6,168 ± 939 | 315 | 4.32 |

| 15a | 2-OCH3 | 12.0 ± 2.8 | 10,895 ± 2,069 | 905 | 4.88 |

| 15b | 4-OCH3 | 97.7 ± 17.4 | 104,847 ± 29,076 | 1,073 | 4.88 |

| 15c | 4-F | 25.6 ± 5.6 | 9,792 ± 1,790 | 383 | 5.32 |

| 15d | pyridine-2-yl | 871 ± 66.9 | 83,671 ± 62,789 | 96.1 | 4.05 |

| 15e | 3-CN | 438 ± 33.6 | 57,101 ± 29,507 | 130 | 4.83 |

| 15f | 2,3-Cl | 82.4 ± 1,053 | 7,501 ± 12.9 | 91.0 | 6.54 |

| 16 | 2-OCH3 | 6.5 ± 0.88 | 260 ± 44.2 | 40.2 | 4.09 |

Spiperone assayed under the same conditions as a reference blocker D2R 0.06 (nM) ± 0.001; D3R 0.33 (nM) ± 0.02; D4R 0.45 (nM) ± 0.01.

Mean ± SEM, Ki values were determined by at least three experiments.

Ki values for D3 receptors were measured using human D3 expressed in HEK cells with [125I]ABN as the radioligand.

Ki values for D2 receptors were measured using human D3 expressed in HEK cells with [125I]ABN as the radioligand.

Ki for D3 receptors/Ki for D2 receptors.

Calculated using ChemDraw Professional 15.1.

rac = racemate.

When investigating bulkier diazaspiro cores G–H as potential amino surrogates with the selected 1,2,4-triazole system, a noticeable increase in D3R potency and selectivity was observed. For example, compounds 14 and 15a exhibited good binding D3R affinity (Ki = 19.6 nM and 12.0 nM, respectively), with 15a demonstrating over 900-fold selectivity. Introduction of the −OCH3 functional group in para position (15b) led to a reduction in receptor affinity (Ki = 97.7 nM), and a slight increase in D3R selectivity. Replacing the aryl group with a para-substituted fluorobenzene on the H amino moiety (compound 15c) resulted in moderate D3R binding affinity (Ki = 25.6 nM) and selectivity (383-fold selectivity) in contrast to 15a. The insertion of a benzonitrile and pyridine moiety (15d and 15e, respectively) led to significant regression in D3R affinity and selectivity. Diazaspiro synthon 6 was evaluated as a potential bioisostere for the classical dichlorphenylpiperazine displayed in many antipsychotics. However, the binding profile for 15f revealed decreased D3R affinity (Ki = 82.4 nM) and selectivity (91.0-fold) in comparison to lead compound 15a.

We also examined the D3R binding profile of compound 16, a piperazine congener of lead compound 15a. Although compound 16 demonstrated a slightly higher affinity at the D3R (Ki = 6.5 nM), a significant decrease in D3R/D2R selectivity was observed (~40-fold) in contrast to 15a. This direct comparison illustrates the potential of spiro system H to act as a viable alternative to the classical arylpiperazine pharmacophore in D3R ligand frameworks.

Compounds 14, 15a, 15c, and 16 were then evaluated for human serotonin 5-HT1A receptor (5-HT1AR) binding affinity (Figure 4), a common off-target binding receptor with piperazine containing D3R scaffolds.31–35 As suspected, we observed low binding profiles at the 5-HT1A receptor with selected spiro compounds 14 (Ki = 724 nM), 15a (Ki = 931 nM), and 15c (Ki = 587 nM). It should also be noted, we briefly furthered the profiles for compounds 14, 15a, and 15c at the 5-HT2A and 5-HT2c receptors as well, and observed low binding affinities comparable to those obtained at the 5-HT1AR (data not shown). Piperazine analogue 16, however, expressed a 0.22 nM binding affinity to the 5-HT1AR, in contrast to the receptor affinity observed with lead compound 15a. In regards to our current research focus in PET probes development, eliminating off-target affinities of D2-like radioligands, such as for serotonin receptors, is pivotal in developing a radiotracer that can image the D3R in clinical settings.

Figure 4.

Competition curve of 14, 15a, 15c, and 16 at the 5-HT1AR. [3H]8-OH-DPAT used as competitive substrate in binding assay. Data shown are determined by at least three experiments.

Finally, we evaluated compounds 11, 14, 15a, and 15c for functional activity using adenylyl cyclase and β-arrestin recruitment assays (Figure 5). With the exception of 15a acting as a partial agonist for adenylyl cyclase, compounds 11, 14, and 15c had low activity in these assays, thus, consistent with their being antagonists at D3R.

Figure 5.

The efficacy of compounds to inhibit forskolin-dependent stimulation of adenylyl cyclase and β-arrestin binding is shown. Each test compound was used at a concentration equal to 10x the Ki value. The bar graph represents the mean percent efficacy ± SEM relative to the full agonist Quinpirole. Mean ± SEM values were determined by at least three experiments. Haloperidol was included as a prototypical antagonist.

CONCLUSION

We have identified several ligand architectures containing modified amino cores that exhibit excellent selectivity and good affinity at the D3R. In addition, diazaspiro cores D, G, and H alleviates serotonin binding, a common off-target effect of piperazine containing D3R ligands, illustrated by 16. Access to arylated diazaspiro synthons can be readily achieved in just 10–20 minutes using our previously reported C–N cross-coupling conditions, affording a convenient synthetic route to these novel D3R scaffolds. Investigation is currently ongoing to further improve D3R binding profiles of these compounds and will be reported in due course.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General

Chemical compounds A–H and K were purchased and used without further purification. NMR spectra were taken on a Bruker DMX 500 MHz. Compound structures and identity were confirmed by 1H and 13C NMR, and mass spectroscopy. Compound purity greater than 95% was determined by LCMS analysis using a 2695 Alliance LCMS. All other commercial reagents were purchased and used without further purification. Purification of organic compounds were carried out on a Biotage Isolera One with a dual-wavelength UV-VIS detector. Chemical shifts (δ) in the NMR spectra (1H and 13C) were referenced by assigning the residual solvent peaks.

Synthesis for Compound 7

3-((3-chloropropyl)thio)-4-methyl-5-phenyl-4H-1,2,4-triazole (7). A mixture of K (2.00 g, 10.46 mmol), 1-bromo-3-chloropropane (10.34 mL, 104.60 mmol), and K2CO3 (2.17 g, 15.00 mmol) were stirred in acetone (30.00 mL) at room temperature for 20 h. The crude reaction mixture was then filtered and solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel eluding with hexane/EtOAc (5:2) affording 2.59 g, 92% yield (white solid). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.55–7.53 (m, 2H), 7.41–7.39 (m, 3H), 3.63 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 3.52 (s, 3H), 3.32 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), (quint, J = 6.4, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.9, 151.2, 130.0, 128.8, 128.5, 127.0, 53.4, 43.1, 31.9, 31.5, 29.9; LC-MS (ESI) m/z: 268.05 [M+H].

General Method for Preparing Diazaspiro Analogues 8–16

The appropriate arylated diazaspiro and piperazine compounds (I), obtained following our previous report,28, 29 were dissolved in CH2Cl2 (2 mL), followed by dropwise addition of CF3COOH (2 mL), and stirred at room temperature for 3 h. Volatiles were then removed under reduced pressure and the crude product was neutralized with a saturated NaHCo3 (aq) solution (10 mL). The reaction mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 20 mL), and the organic layers were combined, dried, and concentrated to afford the free-amine intermediates (J) that were used as such in the following steps.

An equimolar mixture of the appropriate intermediate J (0.50 mmol), 7 (0.50 mmol), and Cs2CO3 (1.0 mmol) was stirred in acetonitrile (5 mL) at 70 °C for 12 h. The crude reaction mixture was then filtered and solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was loaded onto a Biotage SNAP flash purification cartridge and eluded with 10% 7N NH3 in MeOH solution/CH2Cl2 to give the target compounds 8–16.

Alternative Method for Preparing Diazaspiro Analogues 8–16

A mixture of J (1 mmol), 1-bromo-3-chloropropane (2 mmol), and K2CO3 (1.5 mmol) was stirred in acetone (5 mL) at room temperature for 20 h. The crude reaction mixture was then filtered and solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was loaded onto a Biotage SNAP flash purification cartridge and eluded with 5% MeOH in CH2Cl2 affording intermediates L.

A mixture of K (1 mmol), TEA (1.5 mmol), and ethanol (10 mL) was stirred at 75 °C for 15 min. The appropriate intermediate L (1 mmol) was then added, and the solution was stirred at 75 °C for 12 h. Solvent from the crude reaction mixture was then removed under reduced pressure. The residue was loaded onto a Biotage SNAP flash purification cartridge and eluded with 10% 7N NH3 in MeOH solution/CH2Cl2 to give the target compounds 8–16.

Compounds 8–16 were taken up with CH2Cl2 followed by dropwise addition of a 2.0M HCl solution in diethyl ether. After stirring at rt for 1 h, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure to afford the desire compound as a hydrochloride salt for in vitro studies.

Receptor Binding Assays

The binding properties of membrane-associated receptors were characterized by a filtration binding assay.36 For human D2R (long isoform) and D3R expressed in HEK 293 cells, membrane homogenates were suspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl/150 mM NaCl/10 mM EDTA buffer, pH 7.5 and incubated with [125I]IABN36 at 37 °C for 60 min, using 20 μM (+)-butaclamol to define the nonspecific binding. Human 5-HT1AR binding was assessed using membranes from heterologously expressing CHO-K1 cells (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA), suspended in buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM MgSO4, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 0.1% (w/v) ascorbic acid, pH 7.4 and incubated with [3H]-8-OH-DPAT (PerkinElmer) at 27 °C for 60 min. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 10 μM metergoline (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK).

The radioligand concentration was equal to approximately 0.5 (D3/2R) or 1.5–2 (5-HT1AR) times the Kd value, and the concentration of the competitive inhibitor ranged over 5 orders of magnitude for competition experiments. For each competition curve, two concentrations of inhibitor per decade were used, and triplicates were performed. Binding was terminated by the addition of ice cold wash buffer (D2/3R; 10 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5, 5-HT1AR; 10 mM TrisHCl, pH 7.4) and filtration over a glass-fiber filter (D3/2R; Schleicher and Schuell No. 32, 5-HT1AR; Whatman grade 934-AH, GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA). Packard Cobra (D3/2R) or PerkinElmer MicroBeta2 (5-HT1AR) scintillation counters were used to measure the radioactivity. The equilibrium dissociation constant and maximum number of binding sites were generated using unweighted nonlinear regression analysis of data modeled according to the equation describing mass R-binding. The concentration of inhibitor that inhibits 50% of the specific binding of the radioligand (IC50 value) was determined by using nonlinear regression analysis to analyze the data of competitive inhibition experiments. Competition curves were modeled for a single site, and the IC50 values were converted to equilibrium dissociation constants (Ki values) using the Cheng and Prusoff37 correction. Mean Ki values ± SEM are reported for at least three independent experiments.

β-Arrestin Assay

The PathHunter eXpress human D3 dopamine receptor-expressing human bone osteosarcoma epithelial cell line-based (U2OS cell line) β-Arrestin GPCR Assay kit (DiscoverX) was used to determine the efficacy of test compounds for β-arrestin-2 binding. The PathHunter® β-Arrestin D3 receptor cell line was genetically engineered to co-express a ProLink™ (PK) tagged receptor and the Enzyme Acceptor (EA) tagged β-Arrestin. Activation of the Dopamine D3 receptor-PK chimeric protein induces β-Arrestin-EA binding, leading to complementation of two β-galactosidase enzyme fragments (EA and PK), resulting in a functional enzyme that is capable of hydrolyzing substrate and generating a chemiluminescent signal. Following the manufacturer’s protocol, the D3 dopamine receptor expressing U2OS cells are seeded at a concentration of 10,000 cells per well, in white, 96-well, clear-bottomed plates that are provided with the kit. After a 48 hour incubation (37°C, 5% CO2), test compound or control compounds (quinpirole included as a prototypical full agonist and haloperidol as a prototypical antagonist) are added (at a dose of 10x the Ki value) to the appropriate wells and incubated for 90 minutes (37°C, 5% CO2). Kit substrate buffer is added (room temperature, 60 min in the dark) to each well and the luminescence is determined using an EnSpire Alpha 2390 multilabel plate reader (Perkin Elmer).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

National Institute on Drug Abuse [(R01 DA29840-07 to R.H.M.), (R01 DA23957-06 to R. R. Luedtke, University of North Texas Health Science Center-Fort Worth)] is gratefully acknowledged for financial support. SWR is supported by training grant 5T32DA028874-07.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ACN

acetonitrile

- AMP

adenosine monophosphate

- CNS

central nervous system

- DCM

dichloromethane

- D2R

dopamine D2 receptor

- D3R

dopamine D3 receptor

- HEK cells

human embryonic kidney 293 cells

- [125I]IABN

[125I]-N-benzyl-5-iodo-2,3-dimethoxy[3.3.1]azabicyclononan-3-β-ylbenzamide

- Pd

palladium

- PET

positron emission tomography

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications. Molecular formula strings (CSV), along with 1H and 13C NMR spectra, and mass spectral data of isolated compounds 6, and 8–16 (PDF).

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors./All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Maramai S, Gemma S, Brogi S, Campiani G, Butini S, Stark H, Brindisi M. Dopamine D3 Receptor Antagonists as Potential Therapeutics for the Treatment of Neurological Diseases. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:451. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keck TM, John WS, Czoty PW, Nader MA, Newman AH. Identifying Medication Targets for Psychostimulant Addiction: Unraveling the Dopamine D3 Receptor Hypothesis. J Med Chem. 2015;58:5361–5380. doi: 10.1021/jm501512b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joyce JN, Millan MJ. Dopamine D3 Receptor Antagonists as Therapeutic Agents. Drug Discovery Today. 2005;10:917–925. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03491-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortés A, Moreno E, Rodríguez-Ruiz M, Canela EI, Casadó V. Targeting the Dopamine D3 Receptor: An Overview of Drug Design Strategies. Expert Opin Drug Discovery. 2016;11:641–664. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2016.1185413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leggio GM, Bucolo C, Platania CBM, Salomone S, Drago F. Current Drug Treatments Targeting Dopamine D3 Receptor. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;165:164–177. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sokoloff P, Giros B, Martres M-P, Bouthenet M-L, Schwartz J-C. Molecular Cloning and Characterization of a Novel Dopamine Receptor (D3) as a Target for Neuroleptics. Nature. 1990;347:146–151. doi: 10.1038/347146a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho DI, Zheng M, Kim K-M. Current Perspectives on the Selective Regulation of Dopamine D2 and D3 Receptors. Arch Pharm Res. 2010;33:1521–1538. doi: 10.1007/s12272-010-1005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurevich EV, Joyce JN. Distribution of Dopamine D3 Receptor Expressing Neurons in the Human Forebrain: Comparison with D2 Receptor Expressing Neurons. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20:60–80. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Searle G, Beaver JD, Comley RA, Bani M, Tziortzi A, Slifstein M, Mugnaini M, Griffante C, Wilson AA, Merlo-Pich E, Houle S, Gunn R, Rabiner EA, Laruelle M. Imaging Dopamine D3 Receptors in the Human Brain with Positron Emission Tomography, [11C]PHNO, and a Selective D3 Receptor Antagonist. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:392–399. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heidbreder CA, Newman AH. Current Perspectives on Selective Dopamine D3 Receptor Antagonists as Pharmacotherapeutics for Addictions and Related Disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1187:4–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Micheli F. Recent Advances in the Development of Dopamine D3 Receptor Antagonists: a Medicinal Chemistry Perspective. ChemMedChem. 2011;6:1152–1162. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201000538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newman AH, Blaylock BL, Nader MA, Bergman J, Sibley DR, Skolnick P. Medication Discovery for Addiction: Translating the Dopamine D3 Receptor Hypothesis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;84:882–890. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Micheli F, Heidbreder C. Dopamine D3 Receptor Antagonists: A Patent Review (2007 – 2012) Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2013;23:363–381. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2013.757593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robert RL, Robert HM. Progress in Developing D3 Dopamine Receptor Ligands as Potential Therapeutic Agents for Neurological and Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9:643–671. doi: 10.2174/1381612033391199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chien EYT, Liu W, Zhao Q, Katritch V, Won Han G, Hanson MA, Shi L, Newman AH, Javitch JA, Cherezov V, Stevens RC. Structure of the Human Dopamine D3 Receptor in Complex with a D2/D3 Selective Antagonist. Science. 2010;330:1091–1095. doi: 10.1126/science.1197410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newman AH, Beuming T, Banala AK, Donthamsetti P, Pongetti K, LaBounty A, Levy B, Cao J, Michino M, Luedtke RR, Javitch JA, Shi L. Molecular Determinants of Selectivity and Efficacy at the Dopamine D3 Receptor. J Med Chem. 2012;55:6689–6699. doi: 10.1021/jm300482h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Q, Mach RH, Luedtke RR, Reichert DE. Subtype Selectivity of Dopamine Receptor Ligands: Insights from Structure and Ligand-Based Methods. J Chem Inf Model. 2010;50:1970–1985. doi: 10.1021/ci1002747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newman AH, Beuming T, Banala AK, Donthamsetti P, Pongetti K, LaBounty A, Levy B, Cao J, Michino M, Luedtke RR, Javitch JA, Shi L. Molecular determinants of selectivity and efficacy at the dopamine D3 receptor. J Med Chem. 2012;55:6689–99. doi: 10.1021/jm300482h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Micheli F. Novel, Selective, and Developable Dopamine D3 Antagonists with a Modified “Amino” Region. ChemMedChem. 2017;12:1254–1260. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201700148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Micheli F, Arista L, Bertani B, Braggio S, Capelli AM, Cremonesi S, Di-Fabio R, Gelardi G, Gentile G, Marchioro C, Pasquarello A, Provera S, Tedesco G, Tarsi L, Terreni S, Worby A, Heidbreder C. Exploration of the Amine Terminus in a Novel Series of 1,2,4-Triazolo-3-yl-azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexanes as Selective Dopamine D3 Receptor Antagonists. J Med Chem. 2010;53:7129–7139. doi: 10.1021/jm100832d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Micheli F, Bernardelli A, Bianchi F, Braggio S, Castelletti L, Cavallini P, Cavanni P, Cremonesi S, Cin MD, Feriani A, Oliosi B, Semeraro T, Tarsi L, Tomelleri S, Wong A, Visentini F, Zonzini L, Heidbreder C. 1,2,4-Triazolyl Octahydropyrrolo[2,3-b]pyrroles: A New Series of Potent and Selective Dopamine D3 Receptor Antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem. 2016;24:1619–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Micheli F, Arista L, Bonanomi G, Blaney FE, Braggio S, Capelli AM, Checchia A, Damiani F, Di-Fabio R, Fontana S, Gentile G, Griffante C, Hamprecht D, Marchioro C, Mugnaini M, Piner J, Ratti E, Tedesco G, Tarsi L, Terreni S, Worby A, Ashby CR, Heidbreder C. 1,2,4-Triazolyl Azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexanes: A New Series of Potent and Selective Dopamine D3 Receptor Antagonists. J Med Chem. 2010;53:374–391. doi: 10.1021/jm901319p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Micheli F, Bonanomi G, Blaney FE, Braggio S, Capelli AM, Checchia A, Curcuruto O, Damiani F, Di Fabio R, Donati D, Gentile G, Gribble A, Hamprecht D, Tedesco G, Terreni S, Tarsi L, Lightfoot A, Stemp G, MacDonald G, Smith A, Pecoraro M, Petrone M, Perini O, Piner J, Rossi T, Worby A, Pilla M, Valerio E, Griffante C, Mugnaini M, Wood M, Scott C, Andreoli M, Lacroix L, Schwarz A, Gozzi A, Bifone A, Ashby CR, Hagan JJ, Heidbreder C. 1,2,4-Triazol-3-yl-thiopropyl-tetrahydrobenzazepines: A Series of Potent and Selective Dopamine D3 Receptor Antagonists. J Med Chem. 2007;50:5076–5089. doi: 10.1021/jm0705612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mugnaini M, Iavarone L, Cavallini P, Griffante C, Oliosi B, Savoia C, Beaver J, Rabiner EA, Micheli F, Heidbreder C, Andorn A, Merlo Pich E, Bani M. Occupancy of Brain Dopamine D3 Receptors and Drug Craving: A Translational Approach. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:302–312. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Micheli F, Bacchi A, Braggio S, Castelletti L, Cavallini P, Cavanni P, Cremonesi S, Dal Cin M, Feriani A, Gehanne S, Kajbaf M, Marchió L, Nola S, Oliosi B, Pellacani A, Perdonà E, Sava A, Semeraro T, Tarsi L, Tomelleri S, Wong A, Visentini F, Zonzini L, Heidbreder C. 1,2,4-Triazolyl 5-Azaspiro[2.4]heptanes: Lead Identification and Early Lead Optimization of a New Series of Potent and Selective Dopamine D3 Receptor Antagonists. J Med Chem. 2016;59:8549–8576. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burkhard JA, Wagner B, Fischer H, Schuler F, Müller K, Carreira EM. Synthesis of Azaspirocycles and their Evaluation in Drug Discovery. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;49:3524–3527. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carreira EM, Fessard TC. Four-Membered Ring-Containing Spirocycles: Synthetic Strategies and Opportunities. Chem Rev. 2014;114:8257–8322. doi: 10.1021/cr500127b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reilly SW, Bryan NW, Mach RH. Pd-Catalyzed Arylation of Linear and Angular Spirodiamine Salts Under Aerobic Conditions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017;58:466–469. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.12.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reilly SW, Mach RH. Pd-Catalyzed Synthesis of Piperazine Scaffolds Under Aerobic and Solvent-Free Conditions. Org Lett. 2016;18:5272–5275. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Micheli F, Cremonesi S, Semeraro T, Tarsi L, Tomelleri S, Cavanni P, Oliosi B, Perdonà E, Sava A, Zonzini L, Feriani A, Braggio S, Heidbreder C. Novel Morpholine Scaffolds as Selective Dopamine (DA) D3 Receptor Antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2016;26:1329–1332. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.12.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.John Murray P, Harrison LA, Johnson MR, Robertson GM, Scopes DIC, Bull DR, Graham EA, Hayes AG, Kilpatrick GJ, Daas ID, Large C, Sheehan MJ, Stubbs CM, Turpin MP. A Novel Series of Arylpiperazines with High Affinity and Selectivity for the Dopamine D3 Receptor. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1995;5:219–222. [Google Scholar]

- 32.González-Gómez JC, Santana L, Uriarte E, Brea J, Villazón M, Loza MI, De Luca M, Rivas ME, Montenegro GY, Fontenla JA. New Arylpiperazine Derivatives with High Affinity for α1A, D2 and 5-HT2A Receptors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:175–178. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00933-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Terán C, Santana L, Uriarte E, Fall Y, Unelius L, Tolf B-R. Phenylpiperazine Derivatives with Strong Affinity for 5HT1A, D2A and D3 Receptors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1998;8:3567–3570. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00646-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nebel N, Maschauer S, Kuwert T, Hocke C, Prante O. In Vitro and In Vivo Characterization of Selected Fluorine-18 Labeled Radioligands for PET Imaging of the Dopamine D3 Receptor. Molecules. 2016;21:1144. doi: 10.3390/molecules21091144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chu W, Tu Z, McElveen E, Xu J, Taylor M, Luedtke RR, Mach RH. Synthesis and In Vitro Binding of N-Phenyl Piperazine Analogs as Potential Dopamine D3 Receptor Ligands. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luedtke RR, Freeman RA, Boundy VA, Martin MW, Huang Y, Mach RH. Characterization of 125I-IABN, A Novel Azabicyclononane Benzamide Selective for D2-Like Dopamine Receptors. Synapse. 2000;38:438–449. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20001215)38:4<438::AID-SYN9>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yung-Chi C, Prusoff WH. Relationship Between the Inhibition Constant (KI) and the Concentration of Inhibitor Which Causes 50 Percent Inhibition (I50) of an Enzymatic Reaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.