Abstract

Individuals differ in the degree to which they tend to habitually accept their emotions and thoughts without judging them – a process here referred to as habitual acceptance. Acceptance has been linked with greater psychological health, which we propose may be due to the role acceptance plays in negative emotional responses to stressors: acceptance helps keep individuals from reacting to – and thus exacerbating – their negative mental experiences. Over time, experiencing lower negative emotion should promote psychological health. To test these hypotheses, Study 1 (N=1003) verified that habitually accepting mental experiences broadly predicted psychological health (psychological well-being, life satisfaction, depressive and anxiety symptoms), even when controlling for potentially related constructs (reappraisal, rumination, and other mindfulness facets including observing, describing, acting with awareness, and non-reactivity). Next, in an laboratory study (Study 2, N=156), habitual acceptance predicted lower negative (but not positive) emotional responses to a standardized stressor. Finally, in a longitudinal design (Study 3, N=222), acceptance predicted lower negative (but not positive) emotion experienced during daily stressors that, in turn, accounted for the link between acceptance and psychological health six months later. This link between acceptance and psychological health was unique to accepting mental experiences and was not observed for accepting situations. Additionally, we ruled out potential confounding effects of gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and life stress severity. Overall, these results suggest that individuals who accept rather than judge their mental experiences may attain better psychological health, in part because acceptance helps them experience less negative emotion in response to stressors.

Keywords: acceptance, negative emotion, stressors, psychological health

People commonly experience negative emotions and thoughts but approach those negative mental experiences in different ways. On one hand, people can judge these emotions and thoughts as unacceptable or “bad”, struggle with those experiences, and strive to alter them. On the other hand, people can accept their emotions and thoughts and acknowledge them as a natural occurrence. The tendency to accept (versus judge) one’s mental experiences represents a fundamental individual difference that should have important implications for downstream outcomes: Because negative emotions and thoughts are very common, the way individuals approach those experiences has great power to shape individuals’ day-to-day lives, with possible cumulative effects on longer-term outcomes. Although research has suggested that it is generally beneficial to accept (versus judge) mental experiences, key questions remain regarding the mechanisms of these benefits, as well as the scope of these benefits (how broadly does acceptance benefit different facets of psychological health?), their generalizability (how do the benefits of acceptance apply across diverse individuals?), and their specificity (how can alternative explanations for the benefits of acceptance be ruled out?).

We propose that individuals who tend to accept their mental experiences may attain greater psychological health because acceptance helps them experience less negative emotion in response to stressors. At first glance it may seem paradoxical that individuals who accept their negative mental experiences should feel less negative emotion. However, both theory and preliminary findings suggest that acceptance involves helping individuals not react to their own emotions and thoughts, which in turn helps attenuate those mental experiences and allow them to diffuse more quickly (Campbell-Sills, Barlow, Brown, & Hofmann, 2006; Singer & Dobson, 2007). As people who habitually accept their mental experiences repeatedly experience less negative emotion, their psychological health should improve.

Although there has been some theorizing regarding the mechanisms by which habitually accepting emotions and thoughts promotes psychological health (Baer, 2003; Campbell-Sills et al., 2006; Rau & Williams, 2016), little empirical research has directly tested these mechanisms. In the present investigation, we tested the proposed mechanism – less negative emotion – using a daily diary and longitudinal design, after first establishing the basic links between acceptance, emotional responses to stressors, and psychological health.

Habitual Acceptance and Psychological Health

Research has consistently linked the habitual tendency to accept one’s mental experiences with greater psychological health (Baer, Smith, & Allen, 2004; Baer et al., 2008; Cardaciotto, Herbert, Forman, Moitra, & Farrow, 2008; Hayes et al., 2004; Kohls, Sauer, & Walach, 2009). This research has typically demonstrated links between acceptance and clinically-relevant outcomes, such as fewer mood disorder and anxiety symptoms (see Aldao et al., 2010 for meta-analysis). Research on acceptance has often focused on clinical samples (Eisenlohr-Moul, Peters, & Baer, 2015), but links between habitual acceptance and greater psychological health have been demonstrated within non-clinical samples as well (Baer et al., 2004). Furthermore, the benefits of acceptance appear to be unique, having been differentiated from related constructs. For example, while acceptance has often been considered as part of the larger construct of mindfulness (Kohls et al., 2009; Vujanovic, Youngwirth, Johnson, & Zvolensky, 2009), it has been shown to be its own independent factor (Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, 2006), and recent research suggests that acceptance makes unique contributions to psychological health, above and beyond other elements of mindfulness (e.g., observing present-moment experiences, describing internal experiences, acting with awareness, and non-reactivity to inner experiences) (Thompson & Waltz, 2010; Vujanovic et al., 2009).

Given that acceptance appears to uniquely predict psychological health, what might account for this link? Surprisingly little empirical research has examined this question, in spite of its critical theoretical and practical implications for understanding how acceptance functions and how it can help improve psychological health. To advance our understanding of acceptance, we examined a plausible mechanism in the link between acceptance and psychological health: negative emotion. Next, we review research examining the link between acceptance and negative emotion. We focus on acceptance in the context of stress, because stressful situations are most likely to elicit negative mental experiences and are thus when acceptance is needed most.

Habitual Acceptance and Emotional Responses to Stress

It may at first glance appear paradoxical to propose that accepting negative emotions would lead to less negative emotion. However, there are multiple reasons why individuals who accept negative emotions and thoughts would experience less negative emotion: they are less likely to ruminate, which perpetuates negative emotions (Ciesla, Reilly, Dickson, Emanuel, & Updegraff, 2012; Mennin & Fresco, 2013), less likely to try to suppress mental experiences, which can backfire (Masedo & Esteve, 2007; Wegner, Schneider, Carter III, & White, 1987), and less likely to experience negative meta-emotional reactions such as feeling guilty about feeling angry (Mitmansgruber, Beck, Höfer, & Schüßler, 2009). Thus, when people accept (versus judge) their mental experiences, those experiences run their natural – and relatively short-lived – course, rather than being exacerbated (Simons & Gaher, 2005). As a consequence, acceptance should promote overall lower levels of negative emotion (Campbell-Sills et al., 2006; Singer & Dobson, 2007).

Laboratory research has begun to provide support for this idea. Individuals who habitually accept their mental experiences more (vs. less), and who were then exposed to a negative emotion induction, experienced lower levels of negative emotion. This pattern has been observed in the context of completing a physiologically stressful carbon dioxide challenge task (Feldner, Zvolensky, Eifert, & Spira, 2003; Karekla, Forsyth, & Kelly, 2004), working on a frustrating image-tracing task (Feldman, Lavalle, Gildawie, & Greeson, 2016), watching negative film clips (Liverant, Brown, Barlow, & Roemer, 2008; Shallcross, Troy, Boland, & Mauss, 2010), and viewing negative images (Ostafin, Brooks, & Laitem, 2014). Other studies have provided causal evidence, finding that participants who were asked to engage in acceptance (vs. comparison conditions) during a negative emotion induction experienced less negative emotion (Campbell-Sills et al., 2006; Dunn, Billotti, Murphy, & Dalgleish, 2009; Feldner et al., 2003; Huffziger & Kuehner, 2009; Kuehner, Huffziger, & Liebsch, 2009; Levitt, Brown, Orsillo, & Barlow, 2004; Wolgast, Lundh, & Viborg, 2011).

Building upon these laboratory findings, one study found that negative emotional responses to stressors may play a role in the link between acceptance and psychological health: undergraduate students who reported higher habitual acceptance reported less negative emotion in response to several negative images in a laboratory task, which in turn partially accounted for fewer concurrent anxiety symptoms (Ostafin et al., 2014). This investigation represents an important step toward understanding the mechanisms that account for the psychological health benefits of acceptance. As the next step, it is crucial to assess this mechanism as it unfolds in daily life: emotional responses to day-to-day negative contexts (e.g., daily stressors) should reflect the emotional experiences that accumulate to shape psychological health (Almeida, 2005).

To our knowledge, only two investigations have examined whether habitual acceptance predicts emotional responses to daily stressors. First, in a sample of undergraduates who completed seven daily diaries, students higher (vs. lower) in habitual acceptance felt less sad on days when they had more frequent stress-inducing ‘executive functioning lapses’ (e.g., being late for something important) (Feldman et al., 2016). Second, in a sample of adolescents who completed seven daily diaries, youths higher (vs. lower) in habitual acceptance felt less sad on days that were more stressful (Ciesla et al., 2012). These studies begin to suggest that habitual acceptance may play a role in daily emotional responses to stress. However, very little empirical research has examined the underlying mechanisms through which acceptance may be linked with greater psychological health. Next, we describe the limitations of the existing research and how the present investigation addresses them.

The Present Studies

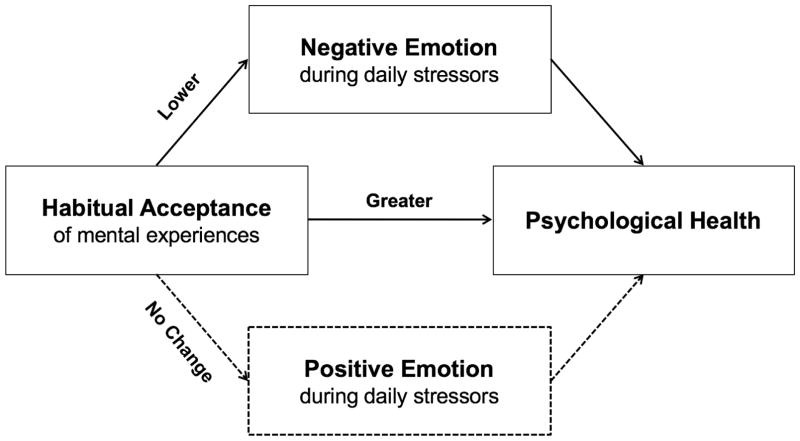

The current investigation examined whether habitually accepting (versus judging) one’s thoughts and emotions is linked to psychological health, and whether it is so because acceptance helps individuals experience less negative emotion during stressors (see Figure 1). Studies 1 and 2 laid the foundation for testing this mediation model by establishing the links between habitual acceptance and psychological health (Study 1) and between habitual acceptance and negative emotional responses to a standardized laboratory stressor (Study 2). Study 3 tested the mediation within a longitudinal design, employing a daily diary design to measure negative emotional responses to daily stressors. Together, these three studies address four unresolved questions within the relatively nascent empirical literature on acceptance: (a) Through which emotional mechanisms does habitual acceptance benefit psychological health? (b) How broadly does acceptance benefit different facets of psychological health? (c) How generalizable are the benefits of acceptance to diverse individuals? (d) How can alternative explanations of the benefits of acceptance be ruled out?

Figure 1.

Conceptual model wherein habitually accepting one’s mental experiences (i.e., emotions and thoughts) contributes to greater psychological health via lower daily negative emotion (and not via daily positive emotion) experienced during daily stressors.

Through which emotional mechanisms does habitual acceptance benefit psychological health?

Identifying the mechanisms that may account for the link between habitual acceptance and psychological health is crucial for improving our understanding of how acceptance functions, but very few studies have empirically tested these mechanisms (see Ostafin et al., 2014 for an exception). In the present investigation, we targeted negative emotional responses to daily stressors (e.g., an argument with a partner, car trouble) as a plausible and potentially important mediator because daily stressors are very common, and how people respond to them exerts strong cumulative effects on well-being (Almeida, 2005). Given our interest in capturing emotional experiences that accumulate over time, we assessed these experiences across 14 days. Habitual acceptance was assessed several days before our mediator, and psychological health was assessed six months after our mediator; as such, our design captures the temporal sequence of our hypotheses.

We also tested whether this mediation model was specific to negative emotional responses. Positive emotion is not redundant with negative emotion and has been shown to have a unique role in adapting to stressors successfully (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2000; Fredrickson, 2001). However, very few investigations of acceptance have reported positive emotion (see Low, Stanton, & Bower, 2008, for an exception), and it is thus an open – and important – question to ask how acceptance may affect positive emotion. Three patterns are possible: acceptance could be (a) linked with greater positive emotion if acceptance improves all emotional experiences, regardless of valence; (b) linked with lower positive emotion if acceptance attenuates both negative and positive emotional responses; (c) unassociated with positive emotion if acceptance has a unique effect on negative emotion. Given that the psychological effects of acceptance such as reducing rumination, attempts at thought suppression, and negative meta-emotions (e.g., worrying about feeling anxious), are more likely to change negative (versus positive) emotion, acceptance itself may be more strongly linked with negative (versus positive) emotion. To gain a more complete understanding of the emotional effects of acceptance, Studies 2 and 3 assessed both negative and positive emotional responses to stress.

How broadly does habitual acceptance benefit psychological health?

Many studies of the link between acceptance and psychological health have focused on measures of suffering (ill-being), such as depressive and anxiety symptoms. However, less ill-being is not redundant with greater well-being (Ryff & Keyes, 1995) and thus, to know how broad the benefits of acceptance are for psychological health, it is important to examine whether acceptance also has positive effects on well-being. To examine psychological health broadly, in Studies 1 and 3, we tested the associations between acceptance and a wide range of psychological health measures targeting both ill-being (depressive and anxiety symptoms) and well-being (psychological well-being and satisfaction with life). This wide range of outcomes allowed us to test whether the benefits of acceptance are limited to avoiding ill-being or extend to promoting well-being.

How generalizable are the benefits of habitual acceptance?

To learn whether acceptance might be beneficial for diverse individuals, it is crucial to test whether demographic variables moderate the link between acceptance and downstream outcomes. While some studies have controlled for demographic variables like gender and socioeconomic status (Harnett, Reid, Loxton, & Lee, 2016; Tomfohr, Pung, Mills, & Edwards, 2015) relatively fewer studies have examined whether these variables might moderate the effects of acceptance (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema & Aldao, 2011). In the current studies, we assessed key demographic features (i.e., gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status) that could shape the outcomes of acceptance. For example, those of lower (vs. higher) socioeconomic status may benefit more from accepting their negative mental experiences if acceptance is more consistent with the broader values supported within lower socioeconomic cultural backgrounds (Snibbe & Markus, 2005). To test whether the link between acceptance and psychological health is generalizable, we examined whether the link was consistent across demographic features for our three studies (total N=1381).

How can alternative explanations of the benefits of acceptance be ruled out?

Three alternative explanations are particularly important to address. First, it is important to address the discriminant validity of acceptance and its links with psychological health vis-à-vis constructs that show conceptual overlap with acceptance. For example, individuals higher in acceptance may also be more likely to reappraise stressful situations in less threatening terms. Additionally, individuals higher in acceptance may be less likely to ruminate over their stressors (either in a brooding manner or in a self-reflective manner). Finally, individuals higher in acceptance may also be higher in other facets of mindfulness: observing present-moment experiences, describing internal experiences, acting with awareness, and non-reactivity to inner experiences. Each of these constructs may help account for greater psychological health. Thus, to examine the discriminant validity of acceptance, we assessed these seven constructs in Study 1 and tested how strongly they are related to acceptance, as well as whether the links between acceptance and psychological health hold when controlling for them.

Second, the link between acceptance and psychological health may be confounded with stress: people with less life stress could find it easier to accept their negative mental experiences because these experiences were less distressing in the first place. At the same time, less life stress should lead to greater psychological health. Very few studies have ruled out stress as a possible confound (an exception: Shallcross et al., 2010); thus, in Study 2, we experimentally induced stress using a tightly controlled standardized procedure that guarantees all participants experienced the same stressor, and in Studies 1 and 3, we controlled for life stress severity.

Third, it is possible that the benefits of acceptance are not specific to accepting mental experiences, but rather extend to any form of acceptance, including the acceptance of external situations (e.g., Carver, Scheier & Weintraub, 1989). Although these two forms of acceptance share the feature of an accepting attitude, the target of that acceptance is quite different. We propose that the target is crucial to the outcomes of acceptance: The non-judgmental acceptance of one’s negative mental experiences during times of stress should allow these negative mental experiences to pass relatively quickly (Baer et al., 2006; Bishop et al., 2004). Accepting stressful situations, in contrast, does not address one’s negative mental experiences and should have relatively little influence on how quickly they pass. Passively resigning oneself to a stressful situation may even lead to worse longer-term psychological outcomes if that situation is potentially controllable. Both theory and research suggest that the acceptance of situations can be maladaptive or adaptive depending on how people engage in acceptance (e.g., active versus passive acceptance of the situation) (Carver & Scheier, in press; Nakamura & Orth, 2005). To ascertain whether the links between acceptance and either daily emotions or psychological health are indeed specific to the acceptance of mental experiences, we also assessed acceptance of situations in Study 1 and 3.1

Study 1

In Study 1, we tested in three undergraduate samples (total N = 1003) whether individuals who accepted their emotions and thoughts experienced greater psychological health, across a wide range of indices targeting both ill-being (depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms) and well-being (psychological well-being, satisfaction with life). The relatively large samples allowed us to examine the generalizability of the link between acceptance and psychological health by testing four possible moderators of that link: gender, ethnicity (European American vs. non-European American), socioeconomic status, and life stress. These data additionally allowed us to test a key alternative hypothesis for why acceptance might be linked with greater psychological health: perhaps people who experience less life stress are both more likely to accept and more likely to be psychologically healthy. Thus, we tested whether the link between acceptance and psychological health held when controlling for life stress. Finally, to test whether the link between acceptance and psychological health is specific to accepting mental experiences (vs. another form of acceptance), we compared its effects to those of accepting situations.

Method

Research ethics committee

The Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of California, Berkeley, approved all study procedures. Sample A was approved under the “Links between emotion, beliefs, and well-being” protocol (#2013-11-5811). Samples B and C were approved under “The effects of emotional goal pursuit” protocol (#2012-08-4593).

Participants

Participants were undergraduate students from the University of California, Berkeley, who received course credit for participation (Samples A, B and C; See Table 1 for a summary of sample characteristics). A total of 542 were enrolled in the study for Sample A, 396 for sample B, and 219 participants for sample C. Prior to data analysis, participants were excluded from analyses if they did not provide responses for the acceptance measure, at least one of the psychological health measures, and at least one of the demographic variables (8% in Sample A, 6% in Sample B, and 5% in Sample C). Additionally, in Samples A and B, participants were excluded if they failed all attention checks provided within the questionnaire (7% and 10% of enrolled participants in Sample A and B, respectively). An attention check consisted of an embedded scale question asking participants to give a certain answer (e.g., “For this item, please select the number six”. Participants failed an attention check if they gave any answer other than the requested answer (in this example, “6”). Attention checks were not included in Sample C. The final sample size was 459 for Sample A, 336 for Sample B, and 208 for Sample C.

Table 1.

Overview: Demographic Characteristics of the Samples and Descriptive Statistics for the Main Predictor Variable—Habitual Acceptance of Mental Experiences

| Study 1 | Study 2 | Study 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Sample A | Sample B | Sample C | Sample D | Sample E | |

| Sample Size | 459 | 336 | 208 | 156 | 222 |

| Age Mean (SD) | 20.7 (2.50) | 21.0 (2.52) | 20.6 (3.57) | 46.4 (17.21) | 41.3 (11.37) |

| Gender (% Female) | 67% | 67% | 100% | 100% | 56% |

| Ethnic composition (in %) | |||||

| European American | 31% | 31% | 26% | 62% | 76% |

| Asian American | 48% | 42% | 53% | 22% | 1% |

| Hispanic/Latino American | 3% | 14% | 9% | 4% | 12% |

| African American | 0% | 3% | 1% | 6% | 2% |

| Others/Mixed ethnicities | 14% | 8% | 7% | 6% | 8% |

| Did not Report | 5% | 2% | 2% | 0% | 1% |

| Acceptance Scale | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.01 (0.83) | 3.02 (0.85) | 3.11 (0.74) | 3.25 (0.74) | 3.24 (0.96) |

| Alpha Reliability | .89 | .91 | .89 | .82 | .89 |

Note. Habitual acceptance of mental experiences was rated on a scale of 1 to 5.

Materials

Acceptance

The degree to which participants habitually accepted their emotions and thoughts was assessed using the nonjudgment subscale of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, 2006). The scale includes eight items (e.g., I tell myself I shouldn’t be feeling the way that I’m feeling) rated on a scale of 1 (never or very rarely true) to 5 (very often or always true) that were averaged to form a composite.

The FFMQ is a widely-used measure of habitual acceptance that assesses acceptance of emotions (e.g., I tell myself I shouldn’t be feeling the way that I’m feeling) and thoughts (e.g., I tell myself I shouldn’t be thinking the way that I’m thinking). To ensure that the items focused on accepting emotions are not empirically distinct from the items focused on accepting thoughts, we separated these items into two subscales in preliminary analyses. We found that the three emotion acceptance items were very highly correlated with the five thought acceptance items (rs > .79), and the associations between emotion acceptance and psychological health (rs range = .24 – .55, average r = .41) were comparable to the associations between thought acceptance and psychological health (rs range: .24 – .54, average r = .41). Thus, accepting emotions and accepting thoughts are empirically related to one another and have similar links with psychological health, and there was thus no strong justification to consider these two targets of acceptance separately.

Finally, in Sample C, we also assessed the degree to which participants habitually accepted situations using the “acceptance” subscale of the Brief COPE Inventory (Carver, 1997), which includes two items (e.g., I’ve been accepting the reality of the fact that it has happened) rated on a scale of 1 (I haven’t been doing this at all) to 4 (I’ve been doing this a lot) that were averaged to form a composite (see Table 1).

Psychological health

Six measures were used to comprehensively assess psychological health across Samples A, B and C. Psychological well-being was assessed using the Scales of Psychological Well-Being (Ryff & Keyes, 1995), which includes 18 items (e.g., For me, life has been a continuous process of learning, changing, and growth) rated on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree) for Samples A and C, and was rated on a scale of 1 to 7 for Sample B. Satisfaction with life was assessed with the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985), which includes five items (e.g., I am satisfied with life) rated on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Depressive symptoms were assessed differently depending on the sample: In Sample A, depressive symptoms were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996), which includes 21 items rated on a scale of 0 (e.g., I do not feel sad) to 3 (e.g., I am so sad or unhappy that I cannot stand it); Due to IRB concerns, one BDI item referencing suicidal ideation was removed. In Sample C, depressive symptoms were assessed using a shortened version of the Center of Epidemiologic Studies- Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), which includes five items (e.g., I felt depressed) rated on a scale of 0 (rarely or none of time) to 3 (most or all the time); and in Sample B, depressive symptoms were assessed using both the BDI and the full 20-item version of the CES-D. Anxiety symptoms were assessed differently depending on the sample: In Sample A, anxiety symptoms were assessed using items selected from Positive and Negative Affect Schedule - Expanded Form (i.e., scared, jittery, nervous, afraid; PANAS-X; Watson & Clark, 1999) rated on a 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely) scale; in Sample B, the same set of anxiety items as Sample A was used, but items were rated on a 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely) scale; and in Sample C, anxiety symptoms were assessed using a different set of anxiety items (i.e., nervousness, worry, anxiety, tenseness) selected from PANAS-X rated on a 0 (not at all) to 9 (extremely) scale. Sample C also assessed anxiety symptoms using the trait subscale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, & Jacobs, 1983), which includes 20 items (e.g., I worry too much over something that really doesn’t matter) rated on a scale of 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always) that were averaged to create a composite.

Demographic variables

In Samples A, B and C, we assessed gender (male vs. female) and ethnicity (European American vs. non-European American) with self-reports. Socioeconomic status was assessed only in Samples A and B: In Sample A, socioeconomic status (SES) was assessed with household income: 7% reported < $20,000, 13% reported $20,000 – $39,999, 11% reported $40,000 –$69,999, 14% reported $70,000 – $99,999, 37% reported > $100,000, and 17% did not report. In Sample B, SES was assessed with four items about finance that were each rated dichotomously (Yes=0 or No=1): whether participants received financial aid, worked to support life, took out loans to support themselves, and received support from their parents for their entire education (reverse-scored). Scores were then summed to create a composite where higher values indicated higher SES.

Sixteen percent of Sample B endorsed none of the above items (indicating relatively low SES); 19% endorsed one of the above items; 14% endorsed two items; 19% endorsed three items; 29% endorse all four items (indicating relatively high SES), and 2% did not report. Although all three samples were college students, they were all enrolled in a large public school that attracts students from a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds.

Stress

Stress was assessed in Sample C only, using a shortened version of the Life Experiences Survey (LES; Sarason et al., 1978), which included 28 items assessing a wide range of stressful life events (e.g., going through a breakup, death of a family member). For each item, participants indicated whether a particular event had occurred during the past 18 months and rated the impact of each event that they experienced on a scale of −3 (extremely negative) to 3 (extremely positive). A summed score was computed for each participant by accumulating all the impact ratings of negatively rated stressful life events. The summed scores were then reversed coded, so that a higher score indicated greater stress.

Discriminant validity measures

Rumination was assessed in Sample C only, using the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991). To parse apart the brooding and reflective facets of rumination, we scored the RRS according to the revised scoring instructions outlined by Treynor, Gonzales and Nolen-Hoeksema (2003), which included three items assessing brooding and five items assessing reflection. Reappraisal was assessed in all three samples, using the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, 2003) which includes six items assessing the habitual use of cognitive reappraisal. Additional facets of mindfulness were assessed in all three samples using the four other subscales of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, 2006): eight items assessing observing present-moment experiences, eight items assessing describing internal experiences, eight items assessing acting with awareness, and seven items assessing non-reactivity to inner experiences.

Procedure

Participants completed measures of acceptance, reappraisal, rumination, the other four mindfulness facets, psychological health, stress, and demographics, in online questionnaires2.

Results

The link between acceptance and psychological health

First, we tested whether participants who habitually accepted their emotions and thoughts tended to report greater psychological health. As predicted, Pearson’s correlations indicated that accepting mental experiences was associated with greater psychological health, across all six psychological health measures in all three samples (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlations of Habitual Acceptance of Mental Experiences (4 Samples) and Habitual Acceptance of Situations (2 Samples) with Psychological Health

| Habitual Acceptance of: | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Experiences | Situations | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Sample A | Sample B | Sample C | Sample E | Sample C | Sample E | |

| Psychological well-being | ||||||

| Ryff Scales | .49* (.48*) | .44* (.43*) | .42* (.41*) | .38* (.35*) | .06 | .14* |

| Satisfaction with life | ||||||

| SWLS | .26* (.24*) | .39* (.37*) | .27* (.27*) | .25* (.21*) | .00 | .09 |

| Depressive symptoms | ||||||

| BDI | −.45* (−.45*) | −.49* (−.49*) | – | −.34* (−.29*) | – | −.12 |

| CES-D | – | −.49* (−.48*) | −.43* (−.42*) | – | .00 | – |

| Anxiety symptoms | ||||||

| Trait anxiety (PANAS-X) | −.41* (−.41*) | −.47* (−.47*) | −.43* (−.43*) | −.44* (−.41*) | .07 | −.04 |

| Trait anxiety (STAI) | – | – | −.57* (−.56*) | – | .02 | – |

| Social anxiety (ASQ) | – | – | – | −.34* (−.32*) | – | −.06 |

Note. Partial correlations controlling for demographic features (gender, ethnicity, SES) and life stress appear in parentheses.

p < .05.

SWLS: Satisfaction with Life Scale. BDI: Beck Depression Inventory. CESD-D: Center of Epidemiologic Studies- Depression Scale. PANAS-X: Positive and Negative Affect Schedule - Expanded Form. STAI: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. ASQ: Anxiety Screening Questionnaire. A dash indicates that a measure was not assessed in the given sample.

Tests of discriminant validity

Second, to examine the discriminant validity of the acceptance measure, we examined the links between acceptance and seven theoretically relevant variables and tested whether the links between acceptance and psychological health remained significant when controlling for each variable.

Reappraisal

Acceptance was related positively, but only weakly, to reappraisal (rs= .22, .19, .18, in Sample A, B, and C, respectively). When controlling for reappraisal in each of the three samples, the correlations between acceptance and psychological health remained significant for all indices of psychological health: psychological well-being, satisfaction with life, depressive symptoms, and trait anxiety (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Analyses Examining the Discriminant Validity of the Habitual Acceptance of Mental Experiences (Study 1).

| Discriminant Validity Measures | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Reappraisal (ERQ) | Rumination Facets (RRS) | Mindfulness Facets (FFMQ) | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Sample A | Sample B | Sample C | Sample C | Sample A | Sample B | Sample C | |||

| Correlations Between Acceptance and Discriminant Validity Measures | .22* | .19* | .18* | Brooding: | −.58* | Observing: | −.09 | −.06 | −.19* |

| Describing: | .27* | .11 | .29* | ||||||

| Reflecting: | −.32* | Awareness: | .56* | .39* | .52* | ||||

| Non-reacting: | .01 | .23* | .13 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Correlations Between Acceptance and Psychological Health, Controlling for Discriminant Validity Measures | |||||||||

| Psychological Well-being | |||||||||

| Ryff Scales | .45* | .40* | .38* | .28* | .29* | .31* | .22* | ||

| Satisfaction with Life | |||||||||

| SWLS | .22* | .35* | .22* | .14 | .15* | .28* | .18* | ||

| Depressive Symptoms | |||||||||

| BDI | −.42* | −.46* | – | – | −.28* | −.36* | – | ||

| CES-D | – | −.46* | −.40* | −.26* | – | −.35* | −.27* | ||

| Anxiety Symptoms | |||||||||

| Trait Anxiety (PANAS-X) | −.39* | −.45* | −.41* | −.31* | −.26* | −.33* | −.22* | ||

| Trait Anxiety (STAI) | – | – | −.55* | −.39* | – | – | −.38* | ||

Note.

p < .05.

For the correlations between acceptance of mental experiences and psychological health, both rumination facets are controlled for simultaneously, and all four mindfulness facets (observing present-moment experiences, describing internal experiences, acting with awareness, and non-reactivity to inner experiences) are controlled for simultaneously. ERQ: Emotion Regulation Questionnaire. RRS: Ruminative Responses Scale. FFMQ: Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire. SWLS: Satisfaction with Life Scale. BDI: Beck Depression Inventory. CES-D: Center of Epidemiologic Studies- Depression Scale. PANAS-X: Positive and Negative Affect Schedule - Expanded Form. STAI: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. ASQ: Anxiety Screening Questionnaire. A dash indicates that a measure was not assessed in the given sample.

Rumination

Acceptance was negatively correlated with the brooding component of rumination (r = −.58, in Sample C), and (to a lesser extent) with the reflection component of rumination (r = −.33, in Sample C). The size of these correlations suggests that acceptance and rumination are related but not redundant constructs. When simultaneously controlling for the brooding and reflection components of rumination, the correlations between acceptance and psychological health remained significant for psychological well-being, depressive symptoms, trait anxiety, and the correlation with satisfaction with life became marginal (p = .054, see Table 3).

Other mindfulness facets

In all three samples, acceptance was modestly or non-significantly related to the four other facets of mindfulness: observing present-moment experiences, describing internal experiences, acting with awareness, and non-reactivity to inner experiences (see Table 3). When simultaneously controlling for the four other mindfulness facets in each of the three samples, the correlations between acceptance and psychological health remained significant for all indices of psychological health: psychological well-being, satisfaction with life, depressive symptoms, and trait anxiety.

Robustness of the link between acceptance and psychological health

Third, we tested whether the links between acceptance and psychological health were robust when controlling for demographic and stress variables. When controlling for gender, ethnicity (European American vs. non-European American), SES, and stress using partial correlations, the links between acceptance and psychological health remained significant (see Table 2).

Moderations of the link between acceptance and psychological health

Fourth, for each sample, we tested whether the demographic variables (gender, ethnicity, and SES) or stress moderated the link between acceptance and each measure of psychological health. Specifically, our design allowed us to examine four possible moderators and whether any resulting moderation replicated across up to six indicators of psychological health. Only two analyses were significant: In sample A, the link between acceptance and depressive symptoms was moderated by ethnicity, β = .12, p = .008; and in sample B, the link between acceptance and trait anxiety was moderated by gender, β = −.10, p = .043. Because these effect sizes are quite small, and the moderations did not replicate for other samples or outcomes, they may be due to chance; therefore, we do not interpret them further. Overall, thus, we can conclude that the links between acceptance and psychological health were consistent across diverse groups of individuals and across different levels of stress.

Contrasting acceptance of mental experiences with acceptance of situations

Finally, we examined how accepting situations was linked with accepting mental experiences, and with psychological health. Accepting situations was not associated with accepting mental experiences, r = −.07, p = .295, and accepting situations was not associated with any measure of psychological health (see Table 2).

Discussion

Results of Study 1 provide evidence that accepting emotions and thoughts is linked with psychological health across multiple measures of both well-being and ill-being, including greater psychological well-being and satisfaction with life as well as lower depressive and anxiety symptoms.

This study also provided important evidence for the discriminant validity of the acceptance measure. Although acceptance was modestly correlated with theoretically relevant constructs such as reappraisal, rumination (brooding and reflection), and additional mindfulness facets (observing present-moment experiences, describing internal experiences, acting with awareness, and non-reactivity to inner experiences), the links between acceptance and psychological health remained significant (and in one analysis, marginal). These findings suggest that while acceptance is related to other theoretically-relevant constructs, acceptance is linked with psychological health above and beyond these other constructs.

The psychological health benefits of accepting mental experiences also did not extend to the acceptance of situations, which was unrelated to acceptance of mental experiences and psychological health. These findings suggest that people may be able to accept their emotions and thoughts without necessarily accepting the situations or events that elicited those experiences, and that it is specifically the acceptance of emotions and thoughts that is beneficial to psychological health.

In addition, the link between acceptance of mental experiences and psychological health was robust when controlling for gender, ethnicity, SES and stress, suggesting that demographic features and stress do not account for the link between acceptance and psychological health. In all three samples, the link between acceptance and psychological health was also not significantly moderated by these demographic features or stress, suggesting that the link between acceptance and psychological health is relatively consistent across men and women, European American and non-European American participants, participants from various SES levels, and at different levels of life stress.

Finding that the link between acceptance and psychological health was robust when controlling for life stress begins to suggest that the correlation between acceptance and psychological health is not merely an artifact of low levels of life stress. However, given that we were only able to address this alterative explanation by controlling for a self-reported measure of stress (and only within one of the three samples), it was important to build upon this finding in Study 2. In Study 2, we addressed the possible confounding influence of life stress more directly by utilizing a standardized laboratory stress induction.

Study 2

We propose that the link between habitual acceptance and psychological health established in Study 1 is accounted for by individuals’ emotional responses to stressors: accepting mental experiences should help people experience less negative emotion in response to their stressors, which should over time improve psychological health. However, in addition to assessing emotional responses to stressors encountered in daily life – as proposed by the present theoretical model – it is important to also examine whether habitually accepting mental experiences is linked with emotional responses to an externally-valid yet standardized laboratory stress induction (Kirschbaum, Pirke & Hellhammer, 1993). This approach has the important function of ruling out the crucial alternative hypothesis that habitual acceptance is associated with less negative emotion and greater psychological health simply because it is confounded with the severity of stressors that people encounter (e.g., less severe stressors might be easier to accept and also evoke less negative emotion).

Study 2 also allowed us to test whether accepting mental experiences is linked with individuals’ experiences of negative or positive emotion during stressors. Not many studies of acceptance have included assessments of positive emotion, and so it remains unclear how acceptance is related to positive emotion. Acceptance could help individuals generate some degree of positive emotion during stressors, but it may also attenuate positive emotion or be unrelated to the positive emotion.

Finally, this laboratory study was conducted with a community sample of female adults that was diverse in ethnicity and socioeconomic status. This sample allowed us to test whether the link between acceptance and emotional responses to a laboratory stressor is generalizable across diverse participants.

Method

Research ethics committee

The Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of California, Berkeley, approved all study procedures within the “Berkeley friendship, emotion, and wellness study” protocol (#2014-10-6844).

Participants

Female participants were recruited from California Bay Area to complete this study as part of a larger research project interested in stress (Sample D). Half of the sample was recruited to have experienced a recent life stressor of at least moderate impact within the past six months. Although the other half of the sample was not required to have experienced a stressor, given how common life stress is, all but three participants in the full sample had experienced a stressful life event in the past six months (e.g., relationship infidelity, job loss, car accident). A total of 160 participants were enrolled in the study. Prior to data analysis, participants were excluded from analyses if they did not provide responses for the acceptance measure and reactivity emotion measure (1%), or if they failed the attention check provided within the questionnaire (1%). The final sample size was 156. The sample was diverse in age, ethnicity, and SES as measured with income: 22% reported < $25,000, 24% reported $25,001 – $50,000, 22% reported $50,001 – $100,000, $24% reported > $100,000, and 8% did not report. See Table 1 for a summary of sample characteristics.

Materials

Acceptance

Acceptance was measured with a shortened and previously validated 5-item version of the scale used in Study 1 (FFMQ; Bohlmeijer, Klooster, Fledderus, Veehof, & Baer, 2011).

Emotional responses to a laboratory stressor

After a baseline task (i.e., watching a neutral film clip) and again after a laboratory stress task (i.e., giving a speech, described below), participants rated the extent to which they experienced negative emotions during those tasks (i.e., sad, lonely, distressed, angry, annoyed, anxious, nervous, embarrassed, rejected) selected from the PANAS-X (Watson & Clark, 1999) on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely). Because our hypotheses were not specific to discrete emotional states, we averaged the negative emotion items to create a negative emotion composite for the neutral clip, α = .80, M = 1.52, SD = 0.67 and for the speech, α = .89, M = 2.63, SD = 1.18. Participants also rated their experience of a wide range positive emotions (happy, excited, energetic, proud, calm, contented, interested, amused, and accepted3), which were averaged to create a positive composite for the neutral clip, α = .88, M = 3.10, SD = 1.08 and for the speech, α = .91, M = 3.35, SD = 1.27.

Demographic variables

Self-reported ethnicity (European American vs. non-European American) and SES (self-reported income) were used as control variables in supplementary analyses.

Procedure

Participants first completed measures of demographics and acceptance in an online questionnaire. Then, approximately four days later, participants completed a laboratory session in which emotional reactivity was measured in response to a well-validated stress induction (Kirschbaum, Pirke, & Hellhammer, 1993; Mauss, Wilhelm, & Gross, 2003, 2004). To establish a baseline, participants first watched a 5-minute neutral film clip and then rated their emotional experiences during the clip. Participants then gave a 3-minute speech on their qualifications for a job, while being video recorded. The video camera was conspicuously placed directly in front of them, and participants were aware that experimenters were currently watching them and that trained judges would later watch their recording. Specifically, participants were told the following:

“You will now have to deliver a three minute speech for a job application. You should imagine that you have applied for a position and were invited by that institution (Corporation, School, or Department) to describe how your communication skills, both verbal and written, qualify you for this job. You will have two minutes to prepare your speech. Please prepare without taking any notes. This speech will be filmed and voice recorded. Later, four judges will take notes regarding the manner, content, and quality of the speech. Judges are trained in behavioral observation, and your nonverbal behavior and body language will be accordingly documented.”

Whenever the participant paused for more than twenty seconds, the experimenters prompted them to continue. After giving the speech, participants rated their emotional experiences during the speech.

Results

Emotional responses to the stress induction

First, we tested whether the laboratory stressor successfully induced negative emotion. As expected, a paired-sample t-test comparing negative emotion experienced during the baseline task (M=1.52, SD=0.67) and during the stress task (M=2.63, SD=1.18) indicated that negative emotion was elevated to a large degree during the stressor, t(155) = 10.91, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.13 (Dunlap, Cortina, Vaslow, & Burke, 1996). A paired-sample t-test comparing positive emotion experienced during the baseline task (M=3.10, SD=1.08) and during the stress task (M=3.35, SD=1.27) indicated that levels of positive emotion were elevated to a small degree during the stressor, t(155) = 2.36, p = .020, Cohen’s d = 0.21. Upon further examination, this increase in positive emotion was due to an increase in higher-arousal positive emotions reflective of activation and task engagement (i.e., energetic and excited increased from M=2.06 to M=3.67, t(155)=11.92, p<.001), and did not extend to lower-arousal positive emotions, which decreased (i.e., calm and contented decreased from M=4.71 to M=3.11, t(155)=11.64, p<.001).

The link between acceptance and negative emotional responses to stress

Second, we tested whether acceptance predicted emotion experienced during the laboratory stressor. As predicted, Pearson’s correlations indicated that acceptance was associated with lower negative emotion during the stressor, r = −.20, p = .013, even when controlling for baseline negative emotion, pr = −.18, p = .027. On the other hand, acceptance was not associated with positive emotion during the stressor, r = .01, p = .883, including when controlling for baseline positive emotion, pr = .05, p = .507.

Robustness of the link between acceptance and negative emotional responses to stress

Finally, we tested whether the link between acceptance and negative emotion was robust when controlling for demographic variables (SES and European American vs. non-European American). The link between acceptance and negative emotion remained also significant when simultaneously controlling for ethnicity and SES using partial correlations, pr = −.19, p = .028, and when simultaneously controlling for baseline negative emotion in addition to ethnicity and SES, pr = −.17, p = .048.

Moderations of the link between acceptance and negative emotional responses to stress

Using the same approach as Study 1, we examined whether the link between acceptance and negative emotion was consistent at different levels of demographic variables. Acceptance consistently predicted lower negative emotion across different levels of ethnicity and SES, as indicated by small and non-significant moderations by ethnicity and SES, βs < .04, ps > .608.

Discussion

The results of Study 2 suggest that habitually accepting emotions and thoughts helps individuals experience less negative emotion in response to stress. Additionally, although participants experienced some measure of positive emotion during the stressor compared to the neutral baseline, acceptance did not predict levels of positive emotion in response to stress. To protect against the possibility of Type II error, we explored whether acceptance differentially predicted different types of positive emotion (i.e., higher vs. lower arousal positive emotion). We found that acceptance predicted neither higher arousal positive emotion (i.e., excited and energetic), r = −.03, p = .743, nor lower arousal positive emotion (i.e., calm and contented), r = .12, p = .145. Overall, these results suggest that acceptance neither attenuated nor enhanced positive emotion. This is important, given that accepting mental experiences could theoretically have the downside of attenuating positive emotion experiences in addition to negative emotion experiences. Our findings suggest that while acceptance helps individuals experience less negative emotion, there is no ‘collateral damage’ in terms of less positive emotion.

The fact that acceptance was linked with less negative emotion in the context of a standardized laboratory stressor rules out a crucial alternative hypothesis: that people who habitually accept their emotions and thoughts experience less negative emotion simply because they encounter less severe stressors. By holding the objective stressor constant across participants, the present results provide evidence that acceptance helps individuals experience less negative emotion rather than the other way around. By ruling out this key confound, this study sets the stage for testing whether acceptance predicts less negative emotion in the real world, in the context of daily stressors. By extending this research into daily experiences, we not only improve the external validity of our findings, but we also target real-world processes that are more relevant to psychological health than a laboratory stress induction. Specifically, we propose that experiencing less negative emotion during stressors in the real world should account for the link between acceptance and greater psychological health. We tested this hypothesis in Study 3 within a longitudinal design that included a daily diary component.

Study 3

Building upon the findings from Studies 1 and 2, Study 3 tested whether people who habitually accept emotions and thoughts experience less negative emotion in the context of daily stressors, and whether lower levels of emotion accounted for greater longitudinally-assessed psychological health. To capture how repeated experiences of lower negative emotion may over time shape psychological health, we examined two weeks of emotional experiences to daily stressors. We examined both negative and positive daily emotional experiences to ensure that the pattern we observed in the laboratory in Study 2 – wherein acceptance predicted negative but not positive emotion – would extend to everyday life. We again assessed several indices of psychological health capturing both ill-being (depressive and anxiety symptoms) and well-being (psychological well-being and satisfaction with life). We measured these outcomes six months after the assessment of acceptance, thereby providing a test of the longitudinal benefits of accepting mental experiences. Given that Study 3 is a community sample of men and women from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, we were again able to ensure that our results generalized across different demographic characteristics. Finally, in addition to measuring participants’ acceptance of mental experiences, we also assessed their acceptance of situations to confirm that the benefits of acceptance are specific to accepting mental experiences.

Method

Research ethics committee

The Institutional Review Board at the University of Denver approved all study procedures within the “Denver emotional adjustment in response to stress study” protocol (#1017).

Participants

A community sample was recruited from the Denver metro area to complete this study as part of a larger project4. A total of 340 participants were enrolled in the study. Participants were excluded from analyses if they did not complete the acceptance measure (1%), if they did not complete any portion of the daily diary element of the study (27%, due to only a subsample of original participants, N=247, being invited to complete the daily diary element of the study), or if they did not complete at least one of the longitudinal measures of psychological health (7%). The final sample size was 222. The sample was diverse in SES as measured by household income: 14% reported < $20,000, 19% reported $20,000 – $39,999, 25% reported $40,000 – $69,9999, 17% reported $70,000 – $99,999, 12% reported > $100,000, and 14% did not report. To enhance variability in psychological health, we recruited participants who had experienced a stressful life event within the past three months. See Table 1 for sample characteristics.

Materials

Acceptance

The degree to which individuals habitually accept their mental experiences was assessed using the nonjudgment subscale of the Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills (KIMS; Baer, Smith, & Allen, 2004). The nonjudgment subscale of the KIMS includes nine items rated on a scale of 1 (never or very rarely true) to 5 (very often or always true), which were averaged to create a composite. The nonjudgment subscale of the KIMS is an earlier version to the nonjudgment subscale of the FFMQ used in Studies 1 and 2, sharing seven of the eight items in the FFMQ. Additionally, acceptance of situations was assessed with the same scale as Study 1 (see Table 1).

Emotional responses during daily stressors

Participants completed a series of diaries each night for fourteen consecutive days. Each night, participants read a series of prompts that guided them through a list of different contexts in which stressful events could have occurred within the past 24 hours and identified which stressors they had experienced. At the end of this procedure, they were asked to report the most stressful event that occurred within the past 24 hours, which could have been one of the stressors listed in the prompts or anything else that was not prompted. This guided-recall procedure was used to reduce bias in the types of events that individuals identified as the most stressful event (Almeida, Wethington, & Kessler, 2002).

Participants then rated the extent to which they felt twelve negative emotions (i.e., sad, hopeless, lonely, distressed, angry, irritable, hostile, anxious, worried, nervous, ashamed, guilty) selected from the PANAS-X (Watson & Clark, 1999) during their most stressful event of the day on a scale of 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely). Because our hypotheses were not specific to discrete emotional states, we averaged across all twelve negative emotions within each day, αs = .87 .91, to create fourteen daily negative emotion composites. Participants also rated their experience of four positive emotions (excited, happy, strong, proud), which were averaged within each day, αs = .74 – .85, to create fourteen daily positive emotion composites.

Psychological health

Five scales were used to comprehensively assess psychological health. Psychological well-being and satisfaction with life were assessed using the same scales as in Study 1. Depressive symptoms were assessed with the same scale as Study 1 Sample A. Trait experience of anxiety was assessed with the same scale as Study 1 Sample A. Social anxiety symptoms were assessed with the social subscale of the Anxiety Screening Questionnaire (ASQ; Wittchen & Boyer, 1998), which includes 16 items that were summed to create a composite.

Demographic variables

Gender (male vs. female), ethnicity (European American vs. non-European American), and SES (household income) were assessed with self-reports.

Stress

Cumulative stress experienced in the past six months was assessed with the full version of the same scale used in Study 1 Sample C. Specifically, participants indicated whether they had experienced 45 stressful life events in the past six months and rated the impact of each event that they endorsed on a scale of −3 (extremely negative) to 3 (extremely positive). A summed score of cumulative stress was computed following the same procedure as Study 1 Sample C.

Procedure

Data were collected at three time points. At Time 1, participants completed measures of demographics and acceptance in an online questionnaire. About one week later, at Time 2 (Median = 8 days), participants began completing the measure of daily emotion experienced during stressors. Specifically, they received a packet of paper-and-pencil daily diaries and were asked to complete one diary each night for 14 consecutive nights. To enhance compliance, participants mailed the diaries back after each week separately. Diary completion rates were good; 79% filled out at least 10 days of diaries, 17% filled out between 5 and 9 days of diaries, and 4% filled out less than five diaries. The full sample is used for all analyses because overall compliance was high and because even a few days’ of assessment are informative for examining the link between acceptance and daily emotional experiences. Finally, at Time 3, which occurred about six months after the diary assessment (Median lag = 6 months, SD = 0.37), participants completed measures of psychological health as well as a measure of the stress they experienced in the preceding six months (i.e., the cumulative stress experienced between the diary assessment and the assessment of psychological health).

Results

Did acceptance predict psychological health?

The link between acceptance and psychological health

First, we tested whether participants who habitually accepted mental experiences tended to report greater psychological health six months later. As in Study 1, Pearson’s correlations indicated that acceptance was associated with greater psychological health, across all five psychological health measures (Table 2).

Robustness of the link between acceptance and psychological health

Second, we tested whether the links between acceptance and psychological health were robust when controlling for demographic and stress variables. When controlling for gender, ethnicity (European American vs. non-European American), SES, and stress using partial correlations, the links between acceptance and psychological health remained significant (see Table 2).

Moderations of the link between acceptance and psychological health

Third, we tested whether the demographic variables (gender, ethnicity, SES) or stress moderated the link between acceptance and psychological health. Specifically, our design allowed us to examine four possible moderators and whether any resulting moderation replicated across five indicators of psychological health. Only two analyses were significant: the link between acceptance and social anxiety was moderated by ethnicity, β = .16, p = .047, and SES, β = .17, p = .013. However, these moderations did not replicate with any of the other outcome measures and may well be due to chance; therefore, we do not interpret them further. Overall, then, these findings suggest that the links between acceptance and psychological health may be relatively consistent across diverse groups of individuals and across different levels of stress.

Contrasting acceptance of mental experiences with acceptance of situations

Finally, we examined how accepting situations was linked with accepting mental experiences and with psychological health. Pearson’s correlations indicated that accepting situations was not associated with accepting mental experiences, r = .00, p = .986, and that accepting situations was not associated with four out of five measures of psychological health (see Table 2). Accepting situations significantly predicted one measure of psychological health: psychological well-being, r = .14, p = .033. However, even when controlling for accepting situations, accepting mental experiences still predicted psychological well-being, pr = .38, p < .001. This correlation was the same magnitude as when not controlling for accepting situations, r = .38, p < .001, suggesting that accepting mental experiences uniquely predicts psychological well-being above and beyond the possible influence of accepting situations.

Did acceptance predict emotion during daily stressors?

The link between acceptance and negative emotional responses to stress

First, multi-level modeling analyses were performed (MPlus Version 7.4; Muthén & Muthén, 2015) to examine the link between acceptance (level 2 variable) and daily emotion experienced during stressors (level 1 variables). Acceptance predicted lower negative emotion during stressors, B = −.25, SE = .04, p < .001, but did not predict positive emotion during stressors, B = .04, SE = .04, p = .309.

Robustness of the link between acceptance and negative emotional responses to stress

Second, we tested whether the link between acceptance and daily negative emotion was robust when controlling for demographic and stress variables. When gender, ethnicity, SES, and stress were entered as covariates within the multi-level model, the link between acceptance and negative emotion remained significant, B = −.22, SE = .04, p < .001.

Moderations of the link between acceptance and negative emotional responses to stress

Third, we tested whether the link between acceptance and daily negative emotion was consistent at different levels of demographic and stress variables. Acceptance consistently predicted lower negative emotion across different levels of gender, ethnicity, SES, and stress as indicated by non-significant moderations by gender, ethnicity, SES, and stress, Bs < .04, ps > .231.

Contrasting acceptance of mental states with acceptance of situations

Finally, multilevel models confirmed that acceptance of situations was not significantly associated with negative emotion, B = −.12, SE = .07, p = .075, or positive emotion, B = .10, SE = .06, p = .088, during daily stressors.

Did daily negative emotion mediate the link between acceptance and psychological health?

Following the guidelines and syntax outlined by Preacher and colleagues (Preacher, Zhang, & Zyphur, 2011; Preacher, Zyphur, & Zhang, 2010), we tested a “2-1-2” two-level random effects mediation model wherein the predictor and the outcome was assessed at level 2 and the mediator was assessed at level 1. Specifically, Level 1 daily negative emotion was modeled as a within subject effect and Level 2 acceptance and psychological health were modeled as between subject effects. Each pathway in the mediation model was modeled using regression commands. In the case of added covariates, each component of the mediation model was additionally regressed onto the various covariates within the analysis, thus controlling for the covariates. Indirect effects were computed by multiplying together the parameter estimates for the a-path and the b-path.

As summarized in Table 4, these analyses confirmed that the link between acceptance and each of the five psychological health measures was mediated by negative emotions during daily stressors. The mediation was full for two indices of psychological health (satisfaction with life and depressive symptoms) and was partial for the other three indices (psychological well-being, trait anxiety, social anxiety symptoms). These significant indirect effects for each psychological health measure held when controlling for gender, ethnicity, SES, and stress as covariates: psychological well-being, B = 0.09, CI95 [0.04, 0.14], satisfaction with life, B = 0.18, CI95 [0.09, 0.28], depressive symptoms, B = −1.57, CI95 [−2.39, −0.76], trait anxiety, B = −0.15, CI95 [−0.23, −0.08], and social anxiety symptoms, B = −0.56, CI95 [−0.90, −0.22].

Table 4.

Multi-Level Mediation Analyses Testing Whether the Link Between the Acceptance of Mental Experiences and Psychological Health is Mediated by Negative Emotion Experienced During Daily Stressors (Study 3).

| Psychological health indicators | Acceptance predicting daily negative emotion | Daily negative emotion predicting psychological health (controlling for acceptance) | Acceptance predicting psychological health (controlling for daily negative emotion) | Coefficient and 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a path) | (b′ path) | (c′ path) | (Indirect effect) | |

| Psychological well-being(Ryff Scales) | B = −0.25, SE = 0.04, p < .001 | B = −0.50, SE = 0.09, p < .001 | B = 0.15, SE = 0.05, p = .002 | B = 0.13 [0.07, 0.18] |

| Satisfaction with life(SWLS) | B = −0.25, SE = 0.04, p < .001 | B = −1.16, SE = 0.21, p < .001 | B = 0.11, SE = 0.12, p = .330 | B = 0.29 [0.18, 0.40] |

| Depressive symptoms(BDI) | B = −0.25, SE = 0.04, p < .001 | B = 9.49, SE = 1.46, p < .001 | B = −1.14, SE = 0.67, p = .089 | B = −2.39 [−3.34, −1.43] |

| Trait anxiety(PANAS-X) | B = −0.25, SE = 0.04, p < .001 | B = 0.81, SE = 0.13, p < .001 | B = −0.24, SE = 0.06, p < .001 | B = −0.20 [−0.29, −0.11] |

| Social anxiety symptoms(ASQ) | B = −0.25, SE = 0.04, p < .001 | B = 2.43, SE = 0.59, p < .001 | B = −0.91, SE = 0.31, p = .003 | B = −0.61, [−0.96, −0.26] |

Note. Bs represent unstandardized multi-level coefficients; SEs represent standard errors. SWLS: Satisfaction with Life Scale. BDI: Beck Depression Inventory. PANAS-X: Positive and Negative Affect Schedule - Expanded Form. ASQ: Anxiety Screening Questionnaire.

For ease of interpretation, we additionally created a global psychological health composite by averaging the standardized well-being measures (psychological well-being and satisfaction with life) and the standardized inverse-scored ill-being measures (depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms). The link between acceptance and the psychological health composite was mediated by negative emotion during daily stressors (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mediation model from Study 3 testing whether habitually accepting one’s mental experiences (i.e., emotions and thoughts) predicts greater psychological health (a composite of psychological well-being, life satisfaction, depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms) via less negative emotion (and not via positive emotion) experienced during daily stressors. Each indirect effect was tested independently. The indirect effect through negative emotion was significant, B = .19, SE = .03, CI95 [0.13, 0.26], and the indirect effect through positive emotion was not, B = .01, SE = .01 CI95 [−0.01, 0.02]. The unstandardized multi-level modeling coefficients (Bs) are shown for each link. The Bs for the paths where both acceptance and the mediator (either negative or positive emotion during daily stressors) were included simultaneously within the model are shown in parentheses.

Discussion

Study 3 replicated and extended the findings from Studies 1 and 2 by testing a mediation model within a longitudinal and daily diary design. We again found evidence that accepting mental experiences is important for psychological health, measured using a variety of indices. Replicating Study 1, we also found that the benefits of acceptance were specific to accepting mental experiences and did not extend to accepting situations. Also replicating Study 1, we found that the link between acceptance and psychological health was robust when controlling for demographic (gender, ethnicity, SES) and stress variables, and was consistent across different levels of demographic and stress variables. Replicating Study 2, we found that the link between acceptance and negative emotional to stressors was robust when controlling for demographic and stress variables, and was consistent across different levels of demographic and stress variables.

Study 3 also built upon the findings from Study 1 and 2 by providing evidence of a mechanism in the link between acceptance and greater psychological health: individuals who habitually accepted their emotions and thoughts experienced less daily negative emotion during daily stressors. Daily negative emotions, in turn, accounted for the association between acceptance and greater psychological health assessed six months later. These mediations suggest that experiencing less negative emotion in response to daily stressors may be one of the key ways in which accepting mental experiences shapes our psychological health.

Replicating and extending Study 2, we found that habitually accepting mental experiences was associated with negative – but not positive – emotional responses to daily stressors. Although the four positive emotions that were assessed in the daily diaries did not allow us to examine lower vs. higher arousal positive emotion, the findings from Study 2 suggests that the absence of a link between acceptance and positive emotion is consistent across different types of positive emotion. This pattern suggests that although maintaining positive emotion in the face of stress is an important contributor to psychological health, acceptance may not help with maintaining or increasing the experience of positive emotion. Importantly, acceptance also did not interfere with the experience positive emotion, which was a viable alternative hypothesis given that acceptance could plausibly attenuate the experience of all emotional responses. Rather, acceptance appears to specifically attenuate the experience of negative emotions, the emotions most likely to be heightened during stressors.

General Discussion

Negative emotions and thoughts are common in everyday life, and individuals can respond to these mental experiences in different ways. While some people tend to accept their emotions and thoughts, others tend to judge them as inappropriate or bad. We propose that the ways in which individuals approach their mental experiences – accepting or judging them – has power to shape individuals’ day-to-day lives, with possible cumulative effects for longer-term psychological outcomes. The present studies were designed to address core unresolved questions regarding the mechanisms that account for the benefits of acceptance (through which emotional mechanisms does habitual acceptance benefit psychological health?), as well as the scope of these benefits (how broadly does acceptance benefit different facets of psychological health?), their generalizability (how do the benefits of acceptance apply across diverse individuals?), and their specificity (how can alternative explanations for the benefits of acceptance be ruled out?).

Negative Emotional Responses to Stress as a Mediator in the Link between Acceptance and Psychological Health

Based on existing research, it was unclear how habitually accepting negative mental experiences may lead to better psychological health. Building from prior theorizing, we proposed that this pathway may be accounted for by the role that acceptance plays in individuals’ negative emotional responses to stress. Although it may seem paradoxical that accepting negative mental experiences would reduce negative emotions, acceptance should help keep individuals from exacerbating or prolonging their negative emotions, thus allowing them to pass relatively quickly. As such, we examined negative emotional responses to stress as a plausible mediator that should account for the longer-term benefits of accepting mental experiences.

Consistent with this prediction, we found that accepting mental experiences predicted lower negative emotional responses to stress both within a laboratory-induced stressor (Study 2) and in daily life (Study 3). We proposed that an extended assessment of daily life represents a particularly powerful method for testing a mediator because the daily emotional experiences fostered by acceptance should accumulate over time and shape individuals’ psychological health. Indeed, using multi-level modeling, we found that the link between accepting mental experiences and longitudinally-assessed psychological health was mediated by individuals’ negative emotional responses to their daily stressors across two weeks of daily diaries.

The present studies also examined whether the mechanism linking acceptance and psychological health is specific to negative emotional responses to stressors, or if the mechanism also includes positive emotional responses to stressors. Effects of positive emotion have rarely been reported in studies of acceptance, and with a scarcity of evidence to build from, we considered several hypotheses for how acceptance might influence positive emotion in the context of stress: if acceptance were linked with “improved” emotional responding across the board in response to stressors, then acceptance would promote greater positive emotion. Alternatively, if acceptance served to lower the experience of any type of emotion – negative or positive – in response to stressors, then acceptance would promote less positive emotion. Instead, we found that acceptance was not related to positive emotional responses to stressors. The same result held whether those positive emotions were high in arousal (e.g., excitement) or low in arousal (e.g., contented), and whether those emotions were evoked be the laboratory stressor (Study 2) or recorded in daily life (Study 3). These findings on positive emotions are important because they provide important information regarding the psychological effects of acceptance. Specifically, acceptance appears to act most strongly on the negative emotions experienced during stressors, and leave positive emotions experienced during stressors relatively unchanged. This asymmetry may occur because the psychological effects of acceptance, such as reducing rumination, attempts at thought suppression, and negative meta-emotions (e.g., worrying about feeling anxious), are more likely to change negative emotion than positive emotion. This asymmetry may also be a core benefit of acceptance – it does not comprehensively shut down emotional responding in response to stress, but rather, it selectively targets negative emotion.

The Breadth and Generalizability of the Benefits of Acceptance