Abstract

Using in vitro models, the mechanics as well as surgical techniques for mitral valves (MV) and MV devices can be studied in a more controlled environment with minimal monetary investment and risk. However, these current models rely on certain simplifications, one being that the MV has a static, rigid annulus. In order to study more complex issues of imaging diagnostics and implanted device function, it would be more advantageous to verify their use for a dynamic environment in a dynamic simulator. This study provides the novel design and development of a dynamically contracting annulus (DCA) within an in vitro simulator, and its subsequent use to study MV biomechanics. Experiments were performed to study the ability of the DCA to reproduce the MV leaflet mechanics in vitro, as seen in vivo, as well as investigate how rigid annuloplasties affect MV leaflet mechanics. Experiments used healthy, excised MVs and normal hemodynamics; contractile waveforms were derived from human in vivo data. Stereophotogrammetry and echocardiography were used to measure anterior leaflet strain and the change in MV geometry. In pursuit of the first in vitro MV simulator that more completely represents the dynamic motion of the full valvular apparatus, this study demonstrated the successful operation of a dynamically contracting mitral annulus. It was seen that the diseased contractile state increased anterior leaflet strain compared to the healthy contractile state. In addition, it was also shown in vitro that simulated rigid annuloplasty increased mitral anterior leaflet strain compared to a healthy contraction.

Keywords: Mitral valve, Annular contraction, In vitro simulator, Leaflet strain, Annuloplasty

1. Introduction

Moderate to severe mitral valve regurgitation (MR) affects 1.7% of adults in the US (Mozaffarian et al., 2015). In MR, the mitral valve (MV) leaflets do not completely coapt, leading to backward flow of blood from the ventricle to the atrium. Currently, in vivo large animal and patient studies do not offer ways to quickly evaluate MV and MV device mechanics, or to do so without higher monetary investment and risk. For functional MR (FMR), the MV maintains a normal anatomy with pathological structure/geometry (Schmitto et al., 2010). This allows in vitro models to be more advantageous due to their ability to use readily-accessible, healthy MVs and easily modify their geometry for different experiments, all while maintaining the valve’s subvalvular anatomy (Siefert and Siskey, 2015).

Using in vitro models, the solid and fluid mechanics of FMR, as well as surgical treatments, can be studied in a more controlled environment than in animal models, with the ability to focus on individual parameters of interest. This environment provides better physical and optical access to the MV, enabling the use of measurement techniques with better spatial and temporal resolution. However, these models are not perfectly representative of in vivo MV performance and rely on certain simplifications, one being that the MV is mounted to a static, rigid annulus (leaflet attachment to the myocardium). This simplification of the annulus is justified for investigations where systolic annular geometry is held constant to assess MR repairs during systole (Jimenez et al., 2006; Rabbah et al., 2014). However, in order to study more advanced issues of imaging diagnostics and implanted device function, it would be more powerful to verify their use for a dynamic environment (i.e. the MV) in a dynamic simulator. This extends to the needs of future MR quantification techniques to account for a moving MR jet orifice, the testing of valvular and perivalvular hemodynamics of transcatheter mitral valve replacements, advancing computational models for surgical planning, and further investigation of MV repair procedures.

Restrictive annuloplasty MV repair is the treatment of choice for patients with FMR (Carpentier, 1983; Carpentier et al., 1980). The annuloplasty ring is implanted into the MV to bring the MV leaflets closer together by reducing the annular area; this provides better leaflet coaptation during systole and reduces MR (Braun et al., 2008). Implantation of an annuloplasty ring restricts the motion of the mitral annulus throughout the cardiac cycle, with stiffer rings imparting greater restriction. Although this surgical repair is an effective treatment, studies have shown MR recurrence as high as 30% in patients with ischemic MR (a major type of FMR) within the first 6 months after operation (McGee et al., 2004). Previous studies have shown that a flat annuloplasty ring can alter anterior leaflet strain with the potential to decrease repair durability (Amini et al., 2012). Assessment of how changes in annular dynamics effect MV leaflet mechanics could help in further understanding long-term outcomes post-annuloplasty.

Motivated by these needs, this study provides the novel design and development of a dynamically contracting annulus (DCA) within an in vitro left heart simulator and subsequent use to study MV biomechanics. Experiments were performed to study the ability of the DCA to reproduce MV leaflet mechanics in vitro, as seen in vivo, as well as investigate how rigid annuloplasties affect MV leaflet mechanics. This was done by comparing anterior leaflet strains of healthy and diseased contractile annulus states, and a comparison of anterior leaflet strains between healthy contraction and static annulus states (modeling rigid annuloplasties).

2. Methods

2.1 Mitral Valve Annulus Plate Design and Development

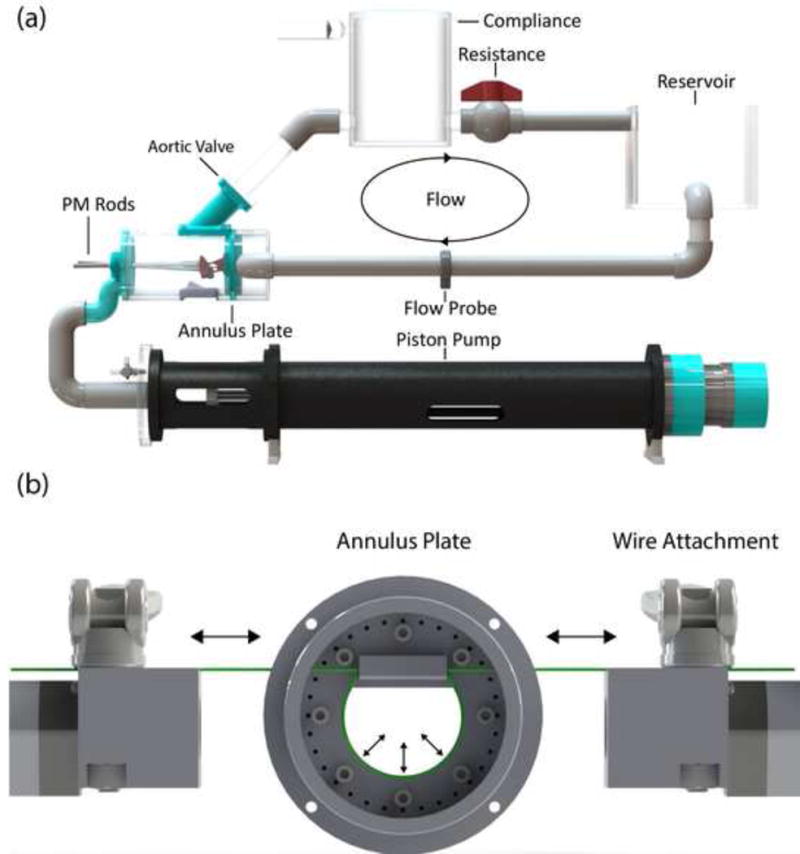

The dynamically contracting MV annulus (DCA) was designed to fit within our existing modular left heart simulators to maintain the current imaging capabilities (Fig. 1a) (Bloodworth et al., 2017; Siefert et al., 2013). A spring was embedded within a Dacron cuff to which the MV annulus is sutured. A wire was fed through the center of the spring and attached to the piston heads of two linear actuators (HAD2-2, RobotZone, Winfield, KS) (Fig. 1b). The wire facilitated contraction of the annulus using the motors, while the spring provided an improved means for relaxation. Two different annulus plates were fabricated; a larger to better accommodate the size of porcine MVs (porcine DCA) and a smaller for ovine (ovine DCA).

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic of left heart simulator complete flow loop with cylindrical chamber for ovine valves. (b) Simplified diagram of the ovine dynamically contracting annulus setup with the annulus plate centered between the wire attachments at the ends of the linear actuators. Cam levers are used to secured the steel wire.

The linear actuators were displacement driven and controlled individually using a proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controller with the addition of a feed-forward loop written in LabVIEW (2015, National Instruments, Austin, TX), and H-bridge controllers (DeviceCraft, Fitchburg, MA) with power supplies (Allied Electronics) to provide voltage to the motors. The positions of the motors were measured using their built-in potentiometers. All displacement waveforms used for the motors were derived from the mean MV annular circumference data from prior human, in vivo 3-D echocardiography work on mitral annular dynamics (Levack et al., 2012). This data was scaled to match the same mean percent areal change for the different annular area sizes of the DCAs.

Tuning of the motors for accuracy and precision of the waveform tracking was done before MV experiments were performed. This was tested in LabVIEW by comparing the actual position of the motors using their potentiometer to the desired position being output by the controller.

2.2 Experimental Set-up

2.2.1 Experimental Conditions

Changes in anterior leaflet strain between physiological and pathophysiological annulus conditions were investigated using the porcine DCA plate (Experiment A). Two states of annular function were tested: 1) healthy and 2) diseased. To isolate the effects of the annular contraction on leaflet strain, only the annulus size/motion was changed between healthy and diseased states, and papillary muscles were left in-place. This consisted of increasing its diastolic area from 11.4 cm2 to 13.0 cm2 to simulate annular dilation and using a contractile waveform consistent with ischemic MR patients. The percent change of contraction from diastole to systole of averaged healthy and ischemic annular area data was used for scaling (−13.2±2.5% and −5.4±1.9% change, respectively).

Changes in anterior leaflet strain between a rigid annuloplasty (static annulus) and a dynamic annulus were investigated using the ovine DCA plate (Experiment B). Three states of annular function were tested: 1) healthy contractile, 2) static-min, and 3) static-max. The minimum and maximum static states were sized to be the systolic and diastolic annular area (4.5 cm2 and 5.5 cm2, respectively) of the healthy dynamic contraction used as the healthy state. Differing from the porcine study, 2-D annular area fraction change as defined by Levack et al. was used for scaling of the healthy contraction (−19.02±4.94% change). This was done to simulate a healthy contraction for a worst-case comparison of differences due to changes made by a rigid annuloplasty. To isolate the effects of the annular contraction on leaflet strain, only the annular variables were changed between states and the papillary muscles remained stationary.

2.2.2 Testing Protocol

Healthy mitral valves were excised from fresh ovine hearts (Superior Farms, Denver, CO) and fresh porcine hearts (Holifield Farms, Atlanta, GA) (n=8 for each). The valves were sized to match the healthy, diastolic annular area of their respective annulus plate. During excision, the annuli and subvalvular structures (i.e. chordae tendineae and papillary muscles) were preserved. The MVs were then mounted into the left heart chamber by suturing the MV annulus to the annulus cuff and attaching the papillary muscles (PM) to the PM positioning rods (Fig. 1a).

A marker grid was applied to the MV leaflets using tissue dye (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH). Stereophotogrammetry was used to track a 3×3 grid on the central A2 scallop (Fig. 2) of the MV using two high-speed A504k cameras (Basler Inc., Exton, PA) and XCAP video acquisition software (EPIX, Inc.; Buffalo Grove, IL) at 250 Hz. Before camera acquisition, the LHS was run for multiple cardiac cycles to remove any initial transients in the MV dynamics and flow due to start-up. A cube of known side-length (1 cm) was placed in the same field-of-view (FOV) of the cameras where, in the paired 2-D camera frames, the same 7 corners of the cube were in their FOV. Using those 7 corners and the known length and shape of the cube, we defined a 3-D coordinate system between the two cameras using direct linear transformation. 4-D echocardiography via ie33 xMatrix ultrasound system and ×7–2 probe (Philips Healthcare, Andover, MA) was used for measuring annular area and leaflet midline coaptation length.

Figure 2.

Ovine mitral valve leaflet marked with tissue dye for stereophotogrammetry. 3×3 grid used for strain measurements highlighted.

Normal left heart pressures and flows (5 liters/min, 100 mmHg peak MV gradient, 70 beats/min, 35/65 systole/diastole ratio) were replicated within the simulator. A custom LabVIEW code was used to control the pulsatile pump (Vivitro Labs, Victoria, BC, CA), and record hemodynamics from wall-tapped pressure transducers (Utah Medical Products, Midvale, UT) and a flow probe (Carolina Medical Electronics, East Bend, NC). The pressure transducers were placed in the left atrium and left ventricle with the flow probe placed within the inlet of the left atrium as shown in Fig. 1a.

2.3 Data Analysis and Statistics

Green areal strain between peak systole and diastole for each state of annular function was computed over one cardiac cycle using a custom code written in MATLAB (R2016a, MathWorks, Natick, MA). Midline leaflet coaptation for each state was measured with QLAB (Philips Healthcare, Andover, MA) using 4-D echocardiography. In addition, annular area change was measured with QLAB to ensure proper annular contraction for each experiment.

The Wilcoxon signed-ranked test was used for paired-group statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics (v24, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

3. Results

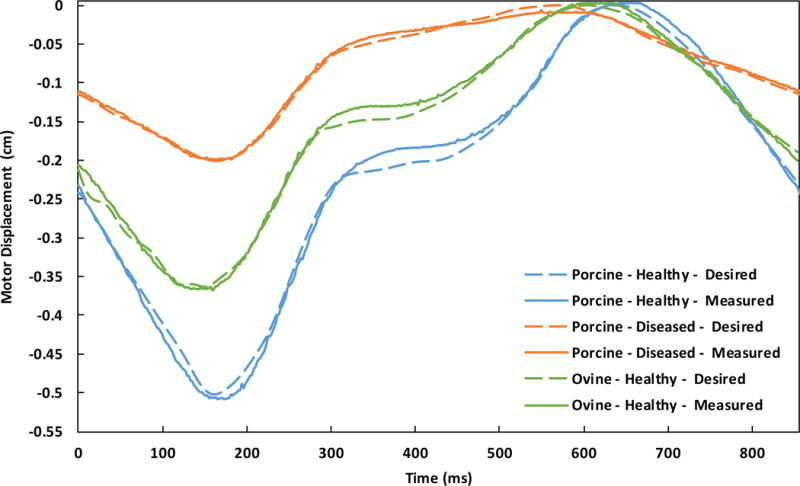

Motor position showed strong agreement with the target waveforms (Fig. 3; Table 1). In addition, tracking annular area showed similar agreement with the desired in vivo percent areal change (Fig. 4; Table 2).

Figure 3.

Comparison of desired and measured displacements of a single linear actuator starting with systole for plate type - waveform.

Table 1.

Resultant accuracy of measured motor displacements compared to their desired waveforms.

| Plate Type | Contractile Waveform | R2 | RMSE (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Porcine | Healthy | 0.99 | 113.3 |

| Diseased | 0.99 | 47.3 | |

| Ovine | Healthy | 0.99 | 84.2 |

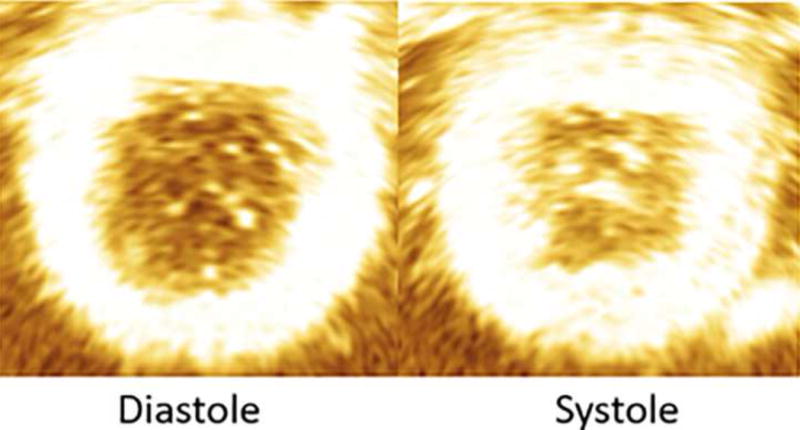

Figure 4.

Echocardiographic image showing annular contraction from diastole to systole (see Table 2 for results).

Table 2.

Measured mean ± SEM annular area of contractile states from 4-D echocardiography compared to the desired annular area.

|

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porcine | Ovine | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Healthy | Diseased | Healthy | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Diastole (cm2) |

Systole (cm2) |

Contraction (%) |

Diastole (cm2) |

Systole (cm2) |

Contraction (%) |

Diastole (cm2) |

Systole (cm2) |

Contraction (%) |

||

| Desired | 11.4 | 9.9 | −13.2 | 13.0 | 12.3 | −5.4 | 5.5 | 4.5 | −19.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Measured | Mean | 11.53 | 9.97 | −13.51 | 13.09 | 12.35 | −5.64 | 5.48 | 4.44 | −18.87 |

| SEM | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.39 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.24 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.61 | |

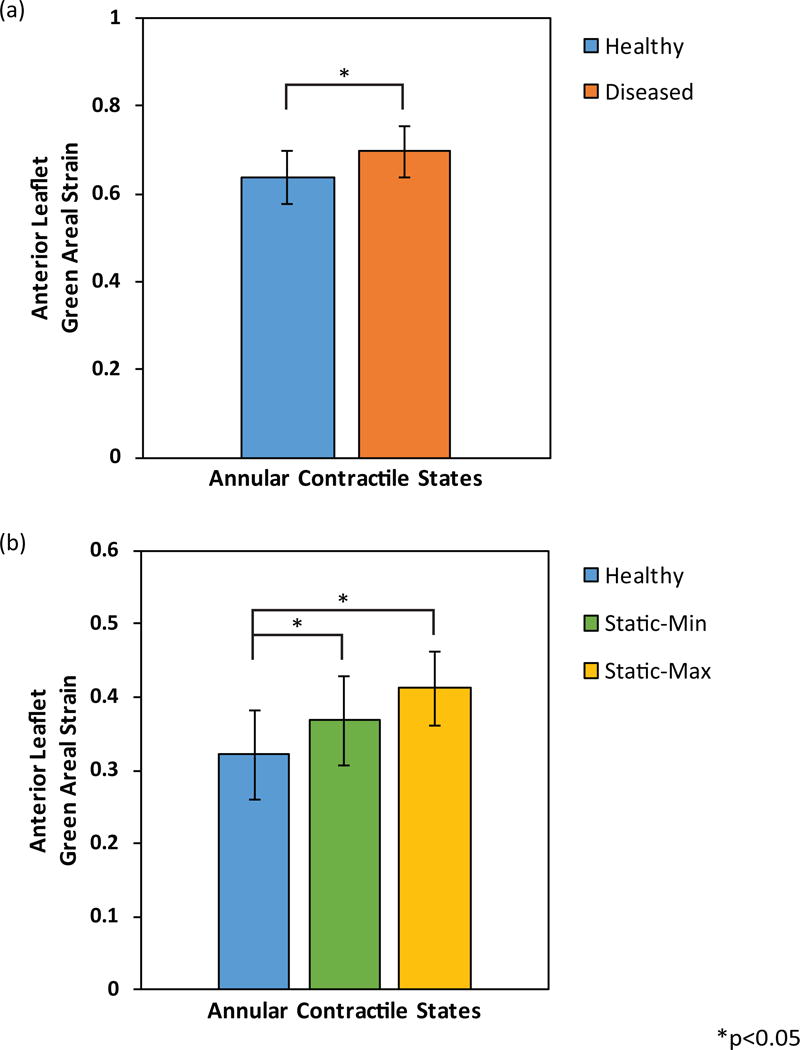

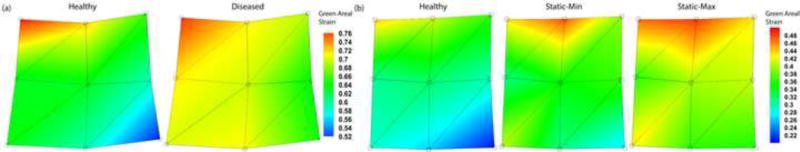

The mean ± standard error (SEM) anterior leaflet strain of the healthy and diseased states from Experiment A were 0.64±0.06 and 0.70±0.06, respectively (Figs. 5a and 6a). The healthy state significantly reduced leaflet strain when compared to the diseased state (p<0.05). There was no significant difference in coaptation length between the two states.

Figure 5.

(a) Anterior leaflet resultant mean ± SEM Green areal strain between annular contractile states: healthy and diseased. (b) Anterior leaflet resultant mean ± SEM Green areal strain between annular states: healthy, static-min, and static-max.

Figure 6.

(a) Anterior leaflet resultant Green areal strain between annular contractile states: healthy and diseased. (b) Anterior leaflet resultant Green areal strain between annular states: healthy, static-min, and static-max.

The mean ± SEM anterior leaflet strain of the healthy, static-min, and static-max states from Experiment B were 0.32±0.06, 0.37±0.06, and 0.41±0.05, respectively (Figs. 5b and 6b). The healthy state significantly reduced leaflet strain versus both static states (each p<0.05). There was no significant difference in anterior leaflet strain between static states, or coaptation length between the three states.

4. Discussion

In pursuit of a mitral valve simulator that more completely represents the dynamic motion of the full valvular apparatus, this study demonstrated the successful operation of a dynamically contracting mitral annulus. Motor accuracy was shown to be in good agreement with the desired waveforms for both the porcine and the ovine annulus plates. It was confirmed that this translated to proper annulus area change during experiments using 4-D echocardiography. With the DCAs shown to reproduce the scaled in vivo geometries, it was necessary to show that the MV leaflet mechanics were also reproduced.

When investigating the reproduction of MV leaflet mechanics of the new simulator in Experiment A, it was seen that the diseased contractile state increased anterior leaflet strain compared to the healthy state. In our study, strain in the center of the A2 scallop was evaluated, as that is where the highest strains are seen (Rausch et al., 2011). Previous porcine in vitro studies have seen comparable areal strain magnitudes (70–75% stretch) when only focusing on the central A2 scallop and using stereophotogrammetry (Sacks et al., 2002). Our results are also in agreement with previous in vivo and in vitro study trends that IMR increases anterior leaflet strain (Siefert et al., 2013). It is noted that our results have a greater magnitude of strain compared to the in vivo measurements; this is believed to be primarily due to differences seen between in vivo and in vitro models, using porcine and ovine valves, and the selected area being measured on the leaflet. Previous review articles have highlighted the increased MV leaflet strains seen with porcine compared to ovine as well as in vivo compared to in vitro (Rabbah et al., 2013b). Overall, our results highlight the ability of the simulator to not only reproduce in vivo MV annular dynamics, but also MV leaflet mechanics.

In Experiment B, it was also shown in vitro that simulated rigid annuloplasty increased mitral anterior leaflet strain compared to a healthy contraction. Previous in vivo animal studies have shown similar results where rigid true-sized annuloplasty rings increase anterior mitral leaflet strains (Bothe et al., 2011). Our work specifically shows that sizing an annuloplasty ring to an MV’s diastolic and systolic annular area leads to increased strain in the anterior leaflet. This implies that rigid annuloplasty rings, regardless of size, can lead to increased strain in the anterior leaflet. Additional in vivo animal studies have also reported that altering the MV geometry using restrictive annuloplasty rings alters strains in the MV anterior leaflet (Amini et al., 2012). Amini, et al. postulates that this annular restriction may affect long-term leaflet durability due to changes in the leaflet’s mechanobiological homeostasis. Clinical studies are needed to investigate if anterior leaflet strain is increased in patients with restrictive annuloplasty rings, and, if so, how it impacts repair failure.

Additionally, there was no significant difference seen in coaptation length between states of both experiments. This is believed to be predominantly due to the use of healthy MVs and the annulus being the only variable changed between experiments. Previous studies have highlighted the effects of isolated annular dilation and PM displacement on decreasing leaflet coaptation (He et al., 1999; Rabbah et al., 2013a). Their results show a much larger increase in annular area (greater than 75%), not representative of the 14% increase from the in vivo human data used in this study, is needed to have a significant decrease in coaptation. In addition, they also show that PM displacement has an even larger effect on decreasing leaflet coaptation, of which was not changed in this study.

The main limitation of this new annular design is that the annulus is flat and its contraction is limited to 2-D, planar motion derived from 2-D projections of 3-D geometry. Physiologically, the MV annulus has a 3-D contractile motion over the cardiac cycle, changing between a saddle-shape and a more flat-shape. It has been previously shown that the saddle-shape of the MV does minimize leaflet strain (Jimenez et al., 2007); it could then be hypothesized that adding this 3-D shape to our study would have presented even greater differences between a saddle-shaped healthy state and the flatter-shaped diseased and annuloplasty states. However, for our study, it was deemed that having a 2-D, planar motion allowed for more use of data as contractile inputs (annular metrics commonly presented as 2-D, planar projections) as well as a simplification that allowed for more control over the experiment.

This work provides the first in vitro MV simulator with a dynamically contracting annulus. The linear actuators in combination with the annular plate designs provided MV annular contraction, and reproduced the annulus area change of previous in vivo studies and MV leaflet mechanics of previous in vitro studies. This new left heart simulator will serve as a platform for future studies in MV biomechanics and repair procedures as well as implanted device testing.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute under Grant R01HL119297. The authors would also like to thank Andrew Seifert and Eric Pierce for their assistance in reviewing work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Amini R, Eckert CE, Koomalsingh K, McGarvey J, Minakawa M, Gorman JH, Gorman RC, Sacks MS. On the In Vivo Deformation of the Mitral Valve Anterior Leaflet: Effects of Annular Geometry and Referential Configuration. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2012;40:1455–1467. doi: 10.1007/s10439-012-0524-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloodworth CH, Pierce EL, Easley TF, Drach A, Khalighi AH, Toma M, Jensen MO, Sacks MS, Yoganathan AP. Ex Vivo Methods for Informing Computational Models of the Mitral Valve. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2017;45:496–507. doi: 10.1007/s10439-016-1734-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bothe W, Kuhl E, Kvitting JPE, Rausch MK, Göktepe S, Swanson JC, Farahmandnia S, Ingels NB, Miller DC. Rigid, Complete Annuloplasty Rings Increase Anterior Mitral Leaflet Strains in the Normal Beating Ovine Heart. Circulation. 2011;124:S81–S96. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.011163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun J, van de Veire NR, Klautz RJ, Versteegh MI, Holman ER, Westenberg JJ, Boersma E, van der Wall EE, Bax JJ, Dion RA. Restrictive mitral annuloplasty cures ischemic mitral regurgitation and heart failure. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2008;85:430–437. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier A. Cardiac valve surgery– the French correction. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 1983;86:323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier A, Chauvaud S, Fabiani J, Deloche A, Relland J, Lessana A, d’Allaines C, Blondeau P, Piwnica A, Dubost C. Reconstructive surgery of mitral valve incompetence: ten-year appraisal. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 1980;79:338–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Lemmon J, Jr, Weston M, Jensen M, Levine R, Yoganathan A. Mitral valve compensation for annular dilatation: in vitro study into the mechanisms of functional mitral regurgitation with an adjustable annulus model. The Journal of heart valve disease. 1999;8:294–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez JH, Forbess J, Croft LR, Small L, He Z, Yoganathan AP. Effects of Annular Size, Transmitral Pressure, and Mitral Flow Rate on the Edge-To-Edge Repair: An In Vitro Study. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2006;82:1362–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez JH, Liou SW, Padala M, He Z, Sacks M, Gorman RC, Gorman JH, Iii, Yoganathan AP. A saddle-shaped annulus reduces systolic strain on the central region of the mitral valve anterior leaflet. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2007;134:1562–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levack MM, Jassar AS, Shang EK, Vergnat M, Woo YJ, Acker MA, Jackson BM, Gorman JH, Gorman RC. Three-Dimensional Echocardiographic Analysis of Mitral Annular Dynamics. Implication for Annuloplasty Selection. 2012;126:S183–S188. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.084483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee EC, Gillinov AM, Blackstone EH, Rajeswaran J, Cohen G, Najam F, Shiota T, Sabik JF, Lytle BW, McCarthy PM. Recurrent mitral regurgitation after annuloplasty for functional ischemic mitral regurgitation. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2004;128:916–924. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Després JP, Fullerton HJ. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics— 2016 Update A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation, CIR. 2015 doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. 0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbah JP, Chism B, Siefert A, Saikrishnan N, Veledar E, Thourani VH, Yoganathan AP. Effects of Targeted Papillary Muscle Relocation on Mitral Leaflet Tenting and Coaptation. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2013a;95:621–628. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbah JPM, Saikrishnan N, Siefert AW, Santhanakrishnan A, Yoganathan AP. Mechanics of healthy and functionally diseased mitral valves: a critical review. Journal of biomechanical engineering. 2013b;135:021007. doi: 10.1115/1.4023238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbah JPM, Siefert AW, Bolling SF, Yoganathan AP. Mitral valve annuloplasty and anterior leaflet augmentation for functional ischemic mitral regurgitation: Quantitative comparison of coaptation and subvalvular tethering. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2014;148:1688–1693. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausch MK, Bothe W, Kvitting JPE, Göktepe S, Craig Miller D, Kuhl E. In vivo dynamic strains of the ovine anterior mitral valve leaflet. Journal of Biomechanics. 2011;44:1149–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks MS, He Z, Baijens L, Wanant S, Shah P, Sugimoto H, Yoganathan AP. Surface Strains in the Anterior Leaflet of the Functioning Mitral Valve. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2002;30:1281–1290. doi: 10.1114/1.1529194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitto JD, Lee LS, Mokashi SA, Bolman RM, III, Cohn LH, Chen FY. Functional mitral regurgitation. Cardiology in review. 2010;18:285–291. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e3181e8e648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siefert AW, Rabbah JPM, Koomalsingh KJ, Touchton SA, Jr, Saikrishnan N, McGarvey JR, Gorman RC, Gorman JH, III, Yoganathan AP. In Vitro Mitral Valve Simulator Mimics Systolic Valvular Function of Chronic Ischemic Mitral Regurgitation Ovine Model. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2013;95:825–830. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siefert AW, Siskey RL. Bench Models for Assessing the Mechanics of Mitral Valve Repair and Percutaneous Surgery. Cardiovascular Engineering and Technology. 2015;6:193–207. doi: 10.1007/s13239-014-0196-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]