Abstract

Objective

Kraepelin considered declining course a hallmark of schizophrenia, but others have suggested that outcomes usually stabilize or improve after treatment initiation. The authors investigated this question in an epidemiologically defined cohort with psychotic disorders followed for 20 years after first hospitalization.

Method

The Suffolk County Mental Health Project recruited first-admission patients with psychosis from all inpatient units of Suffolk County, New York (response rate, 72%). Participants were assessed in person six times over two decades; 373 completed the 20-year follow-up (68% of survivors); 175 had schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder. Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), psychotic symptoms, and mood symptoms were rated at each assessment. Month 6, when nearly all participants were discharged from the index hospitalization, was used as a reference.

Results

In the schizophrenia group, mean GAF scores declined from 49 at month 6 to 36 at year 20. Negative and positive symptoms also worsened (Cohen’s d values, 0.45–0.73). Among participants without schizophrenia, GAF scores were higher initially (a mean of approximately 64) but declined by 9 points over the follow-up period. Worsening began between years 5 and 8. Neither aging nor changes in antipsychotic treatment accounted for the declines. In all disorders, depression improved and manic symptoms remained low across the 20 years.

Conclusions

The authors found substantial symptom burden across disorders that increased with time and ultimately may undo initial treatment gains. Previous studies have suggested that better health care delivery models may preempt this decline. In the United States, these care needs are often not met, and addressing them is an urgent priority.

Emil Kraepelin1 considered declining course a distinguishing feature of schizophrenia (dementia praecox) in contrast to the non-declining, episodic course of mood disorders with psychosis (MoDWP). Others challenged this view, suggesting that a downward trajectory is not typical of schizophrenia and outcomes tend to improve over time2,3. Prospective investigations of clinical course—evolution of symptom burden over time—in first episode/admission psychosis (FEP) can provide key evidence for answering this question, as they employ a well-defined early starting point.

Numerous studies followed FEP cohorts in the short- and mid-term. A systematic review found global outcome to be fairly stable across the first decade of illness4. Recent 10-year follow-ups of two seminal FEP cohorts observed that positive symptoms initially improve and then stabilize, while negative symptoms remain largely unchanged5 and only a minority of participants is continuously ill6. Overall, this research did not suggest a decline in the first decade of illness, but the second decade may be different.

The international Determinants of Outcome of Severe Mental Disorders (DOSMeD) project is the only prospective study to follow FEP patients for two decades7,8. More than half of participants with schizophrenia had good outcome (Global Assessment of Functioning [GAF] score >60), and 50% improved over the interval whereas only 23% declined8. However, limited interim information precluded charting of illness trajectories. Also, these analyses included only one small sample (N = 56) from the U.S., and large cross-national differences in outcomes were observed8. The most similar U.S. project, the Chicago Follow-up Study assessed an early course sample six times over two decades after admission with psychosis. In schizophrenia, global outcome improved through year 7.5 and then stabilized with about 20% having good outcome 9 . Repeated assessment provided a detailed picture of illness course, but conclusions are limited by a sample drawn primarily from a private hospital.

Less is known about long-term course of MoDWP. The DOSMeD study did not analyze this group separately, but presented all non-schizophrenia psychoses together, finding better outcomes (two-thirds had GAF >60) and course (69% improving and only 12% declining) than in schizophrenia8. In the Chicago Follow-up Study, non-schizophrenia psychoses also had better course, with global outcome improving through year 4.5 and then stabilizing with about 40% having good outcome9. Another investigation found that only 8% of MoDWP were continuously ill during the decade after first admission6. No studies have charted illness trajectories of this group over 20 years.

Furthermore, previous long-term studies largely focused on global outcome and overall pattern of course. Consequently, trajectories of specific symptoms are less understood. At least four clearly distinct dimensions of psychotic symptoms have been identified: reality distortion (i.e., hallucinations, delusions), disorganization, inexpressivity, and apathy-asociality10,11. This scheme is an elaboration of the classic 3-dimensional model12 through division of negative symptoms into apathy-asociality and inexpressivity. Mood symptoms—depression and mania—also play a prominent role in psychotic disorders13,14. These six dimensions follow distinct trajectories15 yet long-term data on changes in many of these symptoms are lacking.

The present study sought to address the aforementioned limitations of long-term follow-up studies of clinical course by: (1) examining an epidemiologically-defined FEP cohort, (2) tracing trajectories of the six symptom dimensions as well as global outcome (GAF) across two decades, (3) following a sufficiently large MoDWP group to precisely chart its course and compare to course of schizophrenia, and (4) using longitudinal consensus diagnoses to define study groups with high accuracy. The present study is the first to put the four techniques together, offering an unprecedented opportunity to clarify the disagreement between modern views of illness course and Kraepelin’s descriptions. Moreover, this also is the first study to attempt direct replication of DOSMeD’s long-term findings in the U.S.

Methods

Participants

The cohort was assembled by the Suffolk County Mental Health Project, an epidemiologic study of first-admission psychosis11,16,17. Participants were recruited from the 12 psychiatric inpatient units of Suffolk County, NY, 1990–1995. Inclusion criteria were first admission either current or within six months, clinical evidence of psychosis, ages 15–60, IQ >70, proficiency with English, resident of Suffolk County, and no apparent medical etiology. The study was approved annually by the institutional review boards of Stony Brook University and the participating hospitals.

We initially interviewed 675 participants (72% of referrals); 628 of them met the eligibility criteria. Follow-ups were conducted at 6-month, 24-month, 48-month, 10-year, and 20-year points. Seventy nine participants died during the 20 years. Of the 549 survivors, 373 were successfully contacted at year 20 and constitute the analysis sample. Of them, 68.9% lived in Suffolk County, 6.4% moved to another county in NY, and 24.7% moved to another state. Non-participants were similar to the analysis sample on study variables at baseline (demographics, diagnosis, and symptoms; Table 1), but they were less likely to be Caucasian (67.4% vs. 77.7%) and had more severe reality distortion symptoms (Cohen’s d = .23). For the analysis sample (N=373), we had 2,046 observations across six waves (i.e., data were 91.4% complete). Follow-ups that were done over the phone (277 across waves) did not allow behavioral ratings necessary for scoring inexpressivity, resulting in 1,769 observations available for inexpressivity. Primary analyses employed maximum likelihood estimation and thus used all available data.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Follow-up Cohort (N=373) and Surviving Non-Participants (N=176)

| 20-Year Cohort | Non-Participants | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | ||||

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Male | 222 | 59.5% | 97 | 55.1% | .329 |

| Age less than 28 | 195 | 52.3% | 87 | 49.4% | .533 |

| Blue collar household | 165 | 44.2% | 75 | 42.6% | .721 |

| Race, Caucasian | 290 | 77.7% | 119 | 67.6% | .011 |

| Research diagnosis (last available) | |||||

| Schizophrenia spectrum disorders | 175 | 46.9% | 73 | 41.5% | .531 |

| Bipolar I disorder with psychosis | 94 | 25.2% | 41 | 23.3% | |

| Major depressive disorder with psychosis | 43 | 11.5% | 25 | 14.2% | |

| Substance-induced psychosis | 25 | 6.7% | 16 | 9.1% | |

| Other/undetermined psychosis | 36 | 9.7% | 21 | 11.9% | |

| Baseline Ratings | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | |

| GAF (best month in year before hospitalization) | 58.17 | 14.25 | 59.98 | 14.87 | .172 |

| Apathy-asociality | 9.38 | 7.61 | 8.90 | 6.21 | .435 |

| Inexpressivity | 7.32 | 8.08 | 6.28 | 6.98 | .142 |

| Reality distortion | 10.73 | 8.71 | 12.78 | 10.39 | .024 |

| Disorganization | 6.89 | 6.52 | 6.32 | 5.89 | .321 |

| Depression | 17.52 | 5.38 | 17.22 | 4.93 | .509 |

| Mania/Excitement | 1.66 | 1.16 | 1.53 | 1.07 | .192 |

Surviving nonparticipants were patients who completed baseline assessment but did not participate in the 20-year follow-up assessment and were not known to be deceased: 78 refused, 70 were lost, 15 were impossible to interview (abroad or institutionalized), and 13 provided brief updates insufficient for target ratings. GAF = global assessment of functioning.

Measures

Interviews were conducted by master’s level mental health professionals. Medical records and interviews with significant others were solicited at every assessment. This multi-source information was used to complete the following rating scales about past-month symptoms: the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS 18 the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS19) the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS 20 and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID 21) In the present cohort, we scored four reliable factor-analytically derived subscales from the SANS and SAPS: Inexpressivity (α ≥ .88, 9 items), Apathy-Asociality (α ≥ .81, 6 items), Reality Distortion (α ≥ .80, 14 items), and Disorganization (α ≥ .72, 11 items)11. Mania was operationalized with the excitement rating of the BPRS. Depression symptoms were assessed with the current depression module of the SCID administered without skip-outs. We constructed a nine-symptom depression composite (range: 9 – 27) with excellent reliability (α ≥ .81) and validity11,17. All ratings were highly reliable (eMethods).

Primary DSM-IV diagnosis was formulated at the 10-year point by consensus of study psychiatrists using all available information17. The same process was performed in previous waves, including 6-month assessment. Diagnoses were grouped into five categories: schizophrenia/schizophreniform/schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder with psychosis, depression with psychosis, substance-induced psychosis, and other/undetermined psychosis (e.g., psychotic disorder not otherwise specified). Psychiatrists made consensus ratings of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) for the best month of the year before interview, an index that captures both symptoms burden and functional impairment. At year 20, psychiatrists also rated the overall pattern of clinical course following the DOSMeD criteria (see eMethods)22. For interpretability, we grouped eight course categories into three: single episode (i.e., baseline episode resolved, no recurrence), multiple episodes, and continuous illness (i.e., no remission).

Data Analysis

We investigated trajectories of each disorder on seven outcome measures: GAF (primary measure) and the six symptom dimensions. All participants were highly symptomatic and hospitalized at baseline; therefore, baseline could not be included in the model and we started charting trajectories from month 6. We focus on mean disorder trajectories here. Within-group heterogeneity was reported previously11.

First, we examined clinical course in bivariate analyses, comparing outcomes at subsequent follow-ups to month 6 using paired t-tests. We compared outcomes between disorders using independent samples t-tests. Next, we charted trajectories of disorders across all waves by fitting multi-level spline regression models with random intercept (see eMethods)23–25. Models were fit for each disorder separately; they estimated trajectories of individual participants and then calculated the mean trajectory for the group. These analyses took advantage of variation in follow-ups around target dates (i.e., some were done late and others early), which allowed us to chart trajectories through year 23. However, data were limited for years 5 – 8 and 13 – 16 (< 20 observations/year) and these portions of trajectories were estimated less precisely. Spline regression is a piecewise regression that allows different slopes in different segments of the predictor variable. We considered up to 3 segments (the largest number suggested by descriptive analyses). Transition points between segments were determined empirically by testing the full range of possible transition points and selecting the model with the best Bayesian Information Criterion26. The number of segments was determined similarly. Finally, we added age and antipsychotic medication as time-varying covariates to resulting models to determine whether observed changes were independent from variation in these covariates.

Results

Description of clinical course

Table 2 shows outcomes and antipsychotic medication use of the five diagnostic groups across the two decades. The pattern is notable for worse outcomes in schizophrenia. Differences among the other groups were less pronounced, although bipolar disorder with psychosis and psychotic depression often had better outcomes than substance-induced and other/undetermined psychoses. Importantly, within-group variability was substantial and often dwarfed between-group differences. The overall pattern of clinical course over 20 years indicated that schizophrenia typically followed a chronic course (74.1% continuously ill), whereas an episodic course was common in bipolar disorder with psychosis (79.5%) and psychotic depression (66.7%), and the other two groups fell between them. Psychotic depression, substance-induced psychosis, and other/undetermined groups were too small (N<50) for planned analyses; therefore, we combined groups based on similarity of course, resulting in three larger categories: schizophrenia (N=175), MoDWP (N=137), and other (N=61).

Table 2.

Characteristics of diagnostic groups over time

| Outcome | Schizophrenia

|

Bipolar disorder with psychosis

|

Psychotic depression

|

Substance- induced

|

Other/Undetermined

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| GAF | ||||||||||

| baseline | 52.65 | 14.17 | 67.83 | 9.44 | 60.30 | 12.99 | 57.68 | 11.92 | 57.53 | 14.64 |

| 6 months | 49.34 | 13.18 | 66.37 | 11.90 | 61.45 | 13.94 | 61.74 | 11.45 | 62.73 | 12.67 |

| 24 months | 50.39 | 12.90 | 69.14 | 10.83 | 64.98 | 12.31 | 64.65 | 11.45 | 60.96 | 14.39 |

| 48 months | 49.27 | 12.21 | 70.05 | 11.81 | 67.93 | 12.03 | 65.05 | 13.06 | 63.13 | 15.10 |

| 10 years | 44.06 | 10.67 | 66.95 | 13.14 | 65.61 | 11.72 | 61.39 | 13.99 | 60.93 | 15.49 |

| 20 years | 35.79 | 10.57 | 57.79 | 16.78 | 52.81 | 16.06 | 53.88 | 16.82 | 51.33 | 19.03 |

| Apathy-asociality | ||||||||||

| baseline | 12.11 | 7.36 | 4.95 | 5.74 | 10.67 | 7.60 | 8.40 | 5.61 | 6.86 | 8.26 |

| 6 months | 11.55 | 7.92 | 5.23 | 6.05 | 8.51 | 7.87 | 7.35 | 4.98 | 5.69 | 7.11 |

| 24 months | 11.31 | 6.64 | 3.76 | 5.20 | 6.97 | 7.32 | 5.87 | 5.74 | 6.36 | 6.90 |

| 48 months | 11.30 | 6.70 | 3.70 | 4.67 | 5.67 | 6.88 | 4.47 | 4.90 | 7.67 | 7.12 |

| 10 years | 13.99 | 8.14 | 3.53 | 4.75 | 4.60 | 5.77 | 7.87 | 7.96 | 6.62 | 8.13 |

| 20 years | 17.56 | 8.84 | 8.00 | 7.70 | 10.11 | 8.52 | 9.74 | 9.05 | 11.51 | 10.23 |

| Inexpressivity | ||||||||||

| baseline | 10.22 | 8.39 | 3.86 | 6.10 | 6.60 | 8.43 | 4.28 | 5.70 | 5.28 | 7.23 |

| 6 months | 10.52 | 8.92 | 2.64 | 4.79 | 5.00 | 7.09 | 3.30 | 4.20 | 3.92 | 6.58 |

| 24 months | 9.48 | 8.19 | 1.80 | 2.63 | 3.68 | 5.62 | 3.22 | 5.14 | 2.68 | 4.64 |

| 48 months | 8.82 | 8.82 | 1.61 | 3.15 | 2.24 | 3.66 | 1.53 | 3.22 | 3.72 | 5.30 |

| 10 years | 7.99 | 7.67 | 1.68 | 3.98 | 1.87 | 4.15 | 2.40 | 4.57 | 2.83 | 6.49 |

| 20 years | 10.32 | 10.37 | 3.69 | 5.45 | 4.26 | 7.13 | 4.00 | 6.17 | 7.90 | 11.34 |

| Reality distortion | ||||||||||

| baseline | 12.54 | 9.36 | 10.77 | 8.87 | 6.23 | 6.00 | 8.40 | 6.89 | 8.83 | 6.05 |

| 6 months | 4.26 | 7.44 | 0.56 | 1.29 | 2.81 | 4.56 | 1.52 | 3.19 | 2.50 | 4.67 |

| 24 months | 4.41 | 6.36 | 0.99 | 3.19 | 0.92 | 2.74 | 1.83 | 3.66 | 3.40 | 6.30 |

| 48 months | 4.03 | 6.67 | 1.05 | 2.78 | 0.94 | 2.52 | 1.53 | 3.01 | 3.44 | 7.96 |

| 10 years | 6.66 | 8.24 | 0.46 | 1.86 | 1.03 | 2.29 | 1.78 | 3.25 | 3.07 | 5.69 |

| 20 years | 7.31 | 9.34 | 0.84 | 2.16 | 0.93 | 2.32 | 2.73 | 4.79 | 3.47 | 5.92 |

| Disorganization | ||||||||||

| baseline | 7.19 | 7.00 | 8.97 | 6.05 | 1.86 | 2.96 | 5.68 | 5.37 | 6.89 | 6.07 |

| 6 months | 2.99 | 5.14 | 1.61 | 3.00 | 0.89 | 1.37 | 0.70 | 1.15 | 2.08 | 2.64 |

| 24 months | 2.99 | 4.35 | 2.19 | 3.93 | 1.08 | 2.13 | 2.09 | 3.63 | 3.36 | 5.22 |

| 48 months | 3.65 | 4.87 | 2.34 | 4.22 | 0.73 | 1.86 | 0.47 | 1.02 | 2.33 | 3.07 |

| 10 years | 4.27 | 6.00 | 1.79 | 3.74 | 0.94 | 2.45 | 1.29 | 2.24 | 3.64 | 6.20 |

| 20 years | 6.16 | 7.28 | 3.21 | 5.22 | 2.45 | 4.33 | 2.07 | 3.76 | 5.71 | 6.32 |

| Depression | ||||||||||

| baseline | 17.04 | 5.02 | 16.85 | 5.13 | 22.21 | 5.23 | 16.96 | 5.83 | 16.42 | 5.10 |

| 6 months | 13.55 | 4.03 | 12.13 | 3.35 | 15.51 | 5.51 | 12.70 | 3.97 | 13.04 | 5.08 |

| 24 months | 13.20 | 4.46 | 11.16 | 3.47 | 12.86 | 5.27 | 12.52 | 4.67 | 13.72 | 5.00 |

| 48 months | 10.69 | 3.79 | 9.94 | 3.07 | 12.00 | 5.72 | 10.53 | 3.42 | 11.72 | 5.38 |

| 10 years | 11.92 | 3.76 | 10.99 | 3.47 | 13.35 | 5.10 | 12.55 | 4.27 | 11.37 | 3.25 |

| 20 years | 11.60 | 3.28 | 11.87 | 3.93 | 13.35 | 4.57 | 11.43 | 3.51 | 12.45 | 3.85 |

| Mania/Excitement | ||||||||||

| baseline | 1.49 | 1.00 | 2.13 | 1.39 | 1.07 | 0.34 | 1.96 | 1.34 | 1.78 | 1.22 |

| 6 months | 1.21 | 0.66 | 1.44 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.26 | 0.75 | 1.20 | 0.71 |

| 24 months | 1.22 | 0.65 | 1.41 | 0.92 | 1.14 | 0.48 | 1.22 | 0.60 | 1.48 | 1.08 |

| 48 months | 1.33 | 0.68 | 1.47 | 0.96 | 1.12 | 0.42 | 1.21 | 0.54 | 1.39 | 0.78 |

| 10 years | 1.29 | 0.80 | 1.35 | 0.90 | 1.15 | 0.48 | 1.57 | 1.20 | 1.59 | 1.37 |

| 20 years | 1.28 | 0.83 | 1.34 | 0.87 | 1.13 | 0.47 | 1.14 | 0.48 | 1.21 | 0.63 |

|

| ||||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Use antipsychotics | ||||||||||

| baseline | 152 | 86.9% | 82 | 87.2% | 31 | 72.1% | 15 | 60.0% | 31 | 86.1% |

| 6 months | 148 | 84.6% | 63 | 67.0% | 24 | 55.8% | 9 | 36.0% | 20 | 55.6% |

| 24 months | 136 | 79.5% | 37 | 39.4% | 18 | 41.9% | 4 | 16.7% | 14 | 40.0% |

| 48 months | 122 | 70.1% | 32 | 34.0% | 10 | 23.3% | 4 | 16.0% | 12 | 33.3% |

| 10 years | 142 | 87.1% | 34 | 40.0% | 8 | 20.0% | 6 | 26.1% | 7 | 25.9% |

| 20 years | 117 | 81.8% | 30 | 36.1% | 10 | 25.0% | 4 | 20.0% | 10 | 37.0% |

| Illness pattern over 20 years | ||||||||||

| Single episode | 1 | 0.6% | 10 | 11.4% | 8 | 19.0% | 4 | 17.4% | 10 | 38.5% |

| Multiple Episodes | 43 | 25.3% | 70 | 79.5% | 28 | 66.7% | 13 | 56.5% | 8 | 30.8% |

| Continuous illness | 126 | 74.1% | 8 | 9.1% | 6 | 14.3% | 6 | 26.1% | 8 | 30.8% |

Note: For apathy-asociality, inexpressivity, reality distortion, and disorganization scales, zero indicates no symptoms; depression scale ranges from 9 (no symptoms) to 27; mania/excitement range from one (none) to seven (very severe). Sample size for symptom outcomes is N = 153, 148, 145, 166, and 175 for schizophrenia (6-month to 20–year wave, respectively); 83, 81, 82, 86, and 94 for bipolar disorder with psychosis; 38, 41, 40, 41, and 43 for psychotic depression; 26, 28, 23, 29, and 36 for substance-induced psychosis; and 23, 23, 21, 23, and 25 for other/undetermined psychoses.

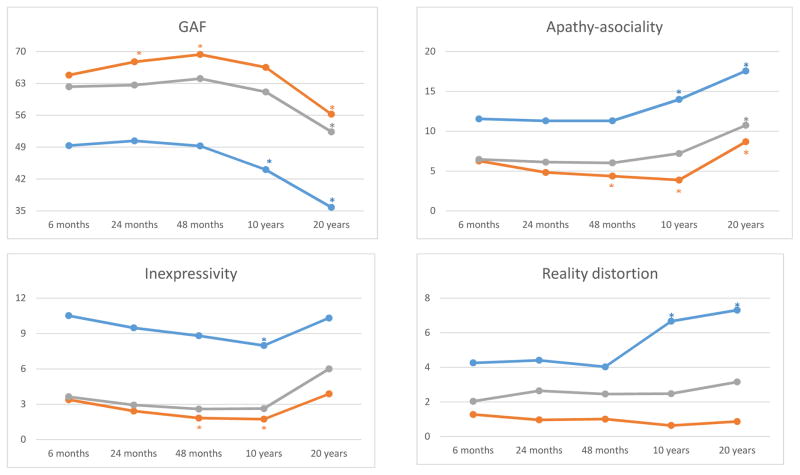

Next, we tested the significance of changes within the three groups from month 6 to each follow-up (Figure 1). The GAF remained stable or improved from month 6 through 48 for each group, but thereafter declined by 13 points in schizophrenia and 9 points in the other groups. With regard to specific symptom dimensions, apathy-asociality also remained stable or improved through month 48, but then worsened (ds = .35 – .73, comparing year 20 to month 6). Inexpressivity improved through year 10, but by year 20 it returned to initial levels. Reality distortion symptoms were at stable low levels throughout the follow-up in MoDWP and other psychoses. In schizophrenia, reality distortion was stable through month 48, but then increased substantially (d = .45), whereas disorganization worsened even more (d = .61). These increases are particularly notable given that rates of antipsychotic medication use remained largely stable in schizophrenia, while they declined dramatically in other disorders (eFigure 1). In contrast, depression decreased and mania/excitement remained stable across the interval.

Figure 1. Outcomes in major diagnostic groups: means at each follow-up and comparison to month 6.

Note: Blue = schizophrenia, orange = mood disorders with psychosis, grey = other psychoses.

Sample size is N = 153, 148, 145, 166, and 175 for schizophrenia (6-month to 20-year wave, respectively), 121, 122, 122, 127, and 137 for MoDWP, and 49, 51, 44, 52, and 61 for other psychoses.

*p<.01 for difference between 6-month and a later follow-up

We also compared clinical course among disorders, focusing on the initial outcome (month 6), long-term outcome (year 20), and the change between these waves (eTable 1). Compared to MoDWP, schizophrenia had consistently worse outcomes on GAF, apathy-asociality, inexpressivity, reality distortion, and disorganization. Moreover, worsening was greater in schizophrenia than in MoDWP on these outcomes, except for inexpressivity. No differences were observed between disorders on depression and mania/excitement. The only difference between other psychoses and MoDWP was higher reality distortion symptoms at year 20 in the former.

Although highly accurate, 10-year diagnosis may be confounded by illness course during the first decade. To consider the impact of this confounding, we repeated the analyses using 6-month diagnosis (eFigure 2). Schizophrenia trajectories were virtually unchanged for GAF, apathy-asociality, inexpressivity, reality distortion, and disorganization, whereas MoDWP and other psychoses showed more severe trajectories with 6-month vs 10-year diagnosis. This pattern is consistent with misclassification, namely that some cases who followed schizophrenia trajectory were assigned other diagnoses at month 6. Indeed, we previously found in this cohort that many 6-month non-schizophrenia cases were later reclassified as schizophrenia, whereas few people shifted out of schizophrenia17. The reanalysis with 6-month diagnosis had little impact on trajectories of mood symptoms.

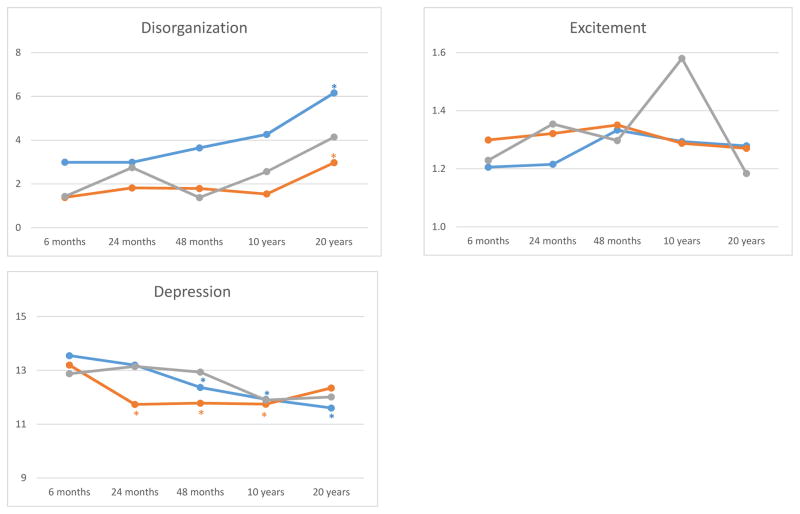

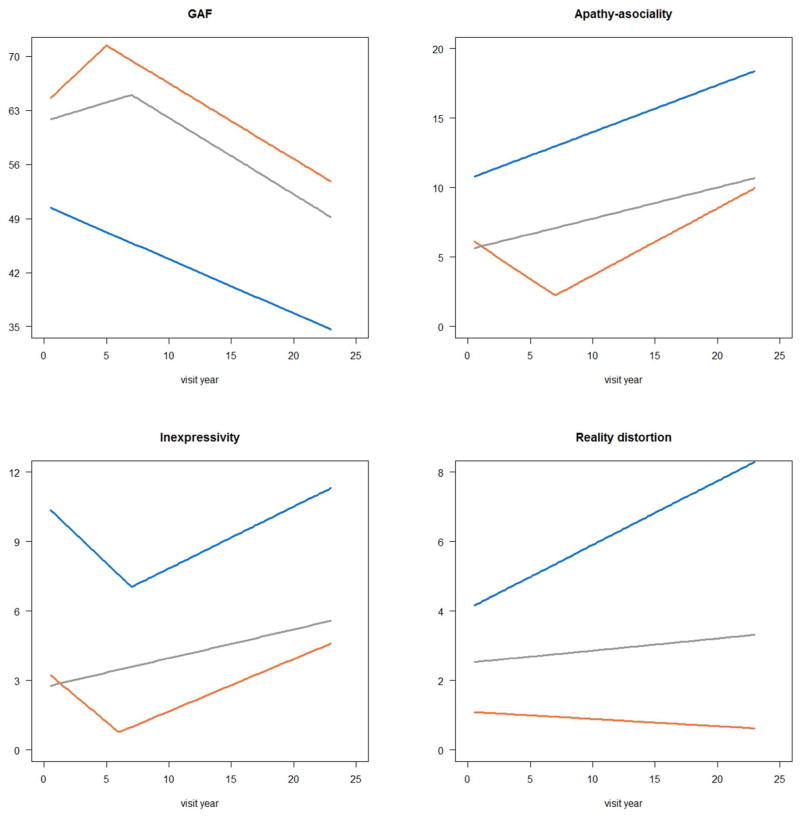

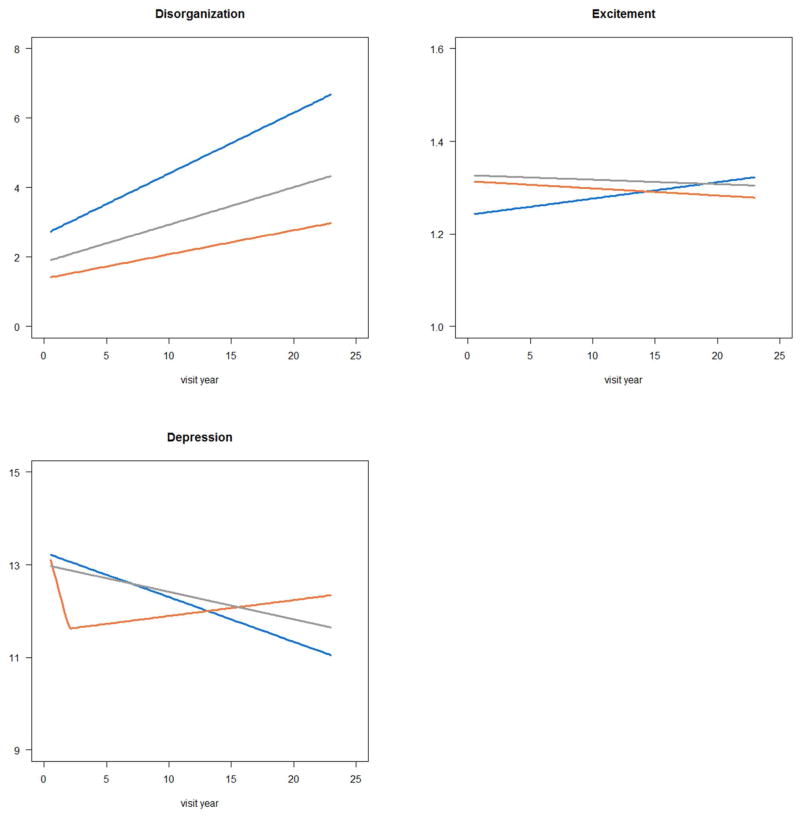

Trajectories of diagnostic groups

Next, we used multi-level spline regression to estimate trajectories of the three groups across the entire follow-up for each outcome. The number of segments was determined empirically (eTable 2). Selected models were either linear (i.e., had only one segment) or allowed one change in trajectory’s slope (i.e., had two segments). Estimated trajectories (Figure 2) closely resembled longitudinal patterns obtained by smoothing raw data (eFigure 3), which suggests that models represented the data well. Change per year and its significance are given in Table 3 (unadjusted columns).

Figure 2. Trajectories of diagnostic groups post-admission modeled using spline regression.

Note: Blue line is schizophrenia, orange line is mood disorders with psychosis, grey line is other psychoses

Sample size is N = 175 for schizophrenia, 137 for MoDWP, and 61 for other psychoses.

Table 3.

Changes in symptoms over time: unadjusted and adjusting for age and antipsychotic medications

| Schizophrenia | MoDWP | Other Psychoses | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||||

| B | p-value | B | p-value | B | p-value | B | p-value | B | p-value | B | p-value | |

| GAF | ||||||||||||

| Time(S1) | −0.70 | <.001* | −0.59 | <.001* | 1.52 | <.001* | 1.26 | <.001* | 0.49 | .119 | 0.60 | .097 |

| Time(S2) | --- | --- | --- | --- | −0.98 | <.001* | −0.94 | <.001* | −0.99 | <.001* | −0.60 | .011 |

| Age | --- | --- | −0.10 | .231 | --- | --- | −0.07 | .415 | --- | --- | −0.31 | .055 |

| Antipsychotics | --- | --- | −0.84 | .480 | --- | --- | −4.78 | <.001* | --- | --- | −5.19 | .004* |

| Apathy-asociality | ||||||||||||

| Time(S1) | 0.34 | <.001* | 0.26 | <.001* | −0.59 | <.001* | −0.58 | <.001* | 0.22 | <.001* | 0.05 | .571 |

| Time(S2) | --- | --- | 0.48 | <.001* | 0.40 | <.001* | --- | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Age | --- | --- | 0.09 | .133 | --- | --- | 0.09 | .014 | --- | --- | 0.16 | .045 |

| Antipsychotics | --- | --- | 2.59 | .001* | --- | --- | 2.33 | <.001* | --- | --- | 1.90 | .058 |

| Inexpressivity | ||||||||||||

| Time(S1) | −0.51 | <.001* | −0.55 | <.001* | −0.45 | <.001* | −0.29 | .019 | 0.12 | .035 | 0.11 | .245 |

| Time(S2) | 0.27 | <.001* | 0.32 | .002* | 0.23 | <.001* | 0.21 | <.001* | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Age | --- | --- | 0.00 | .957 | --- | --- | −0.02 | .453 | --- | --- | 0.01 | .912 |

| Antipsychotics | --- | --- | 2.59 | .003* | --- | --- | 2.04 | <.001* | --- | --- | 1.98 | .035* |

| Reality distortion | ||||||||||||

| Time | 0.18 | <.001* | 0.20 | .003* | −0.02 | .102 | −0.04 | .056 | 0.03 | .299 | −0.04 | .553 |

| Age | --- | --- | −0.02 | .679 | --- | --- | 0.02 | .124 | --- | --- | 0.07 | .208 |

| Antipsychotics | --- | --- | −1.82 | .027 | --- | --- | 0.54 | .020 | --- | --- | 2.24 | .001* |

| Disorganization | ||||||||||||

| Time | 0.18 | <.001* | 0.18 | .001* | 0.07 | <.001* | 0.05 | .064 | 0.11 | .001* | 0.03 | .602 |

| Age | --- | --- | −0.01 | .875 | --- | --- | 0.02 | .393 | --- | --- | 0.07 | .146 |

| Antipsychotics | --- | --- | −1.65 | .005* | --- | --- | 0.00 | .990 | --- | --- | −0.05 | .939 |

| Depression | ||||||||||||

| Time(S1) | −0.10 | <.001* | −0.08 | .016 | −0.99 | .001* | −0.89 | .002* | −0.06 | .065 | −0.15 | .007* |

| Time(S2) | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.03 | .166 | 0.00 | .969 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Age | --- | --- | −0.02 | .466 | --- | --- | 0.04 | .130 | --- | --- | 0.08 | .056 |

| Antipsychotics | --- | --- | 0.72 | .088 | --- | --- | 0.83 | .033 | --- | --- | 1.49 | .019 |

| Mania/Excitement | ||||||||||||

| Time | 0.00 | .313 | 0.01 | .149 | 0.00 | .696 | 0.00 | .887 | 0.00 | .889 | -0.01 | .368 |

| Age | --- | --- | -0.01 | .291 | --- | --- | 0.00 | .549 | --- | --- | 0.01 | .332 |

| Antipsychotics | --- | --- | -0.20 | .009* | --- | --- | 0.09 | .229 | --- | --- | 0.02 | .896 |

Note: B = change in symptom score per year; dashes indicate non-applicable (i.e., effects not included in the model). MoDWP = mood disorder with psychosis. S1 is first segment of the 20-year interval or the entire interval, if we model has only one segment; S2 is the second segment. Transition point between segments for GAF was at year 5 in MoDWP and year 7 in other psychoses; for apathy-asociality it was at year 7 in MoDWP; for inexpressivity it was at year 6 in MoDWP and year 7 in schizophrenia; for depression it was at year 2 in MoDWP. Sample size is N = 175 for schizophrenia, 137 for MoDWP, and 61 for other psychoses.

p <.01

GAF declined significantly in schizophrenia; it improved in MoDWP and other psychoses initially, but declined significantly after approximately year 7 (Figure 2). Apathy-asociality worsened in all groups, although in MoDWP it improved through about year 7 and then deteriorated well beyond the initial level. Inexpressivity lessened until approximately year 7 but increased thereafter, except for other psychoses where the trajectory was flat throughout. Reality distortion increased in schizophrenia but remained stable in the other groups. Disorganization worsened in all disorders. Depression improved in all groups, but in MoDWP improvement plateaued at year 2. Mania/excitement did not change significantly across the interval. Changes in GAF were primarily driven by changes in apathy-asociality and reality distortion (eTable 3).

To test whether observed patterns reflect effects of aging or changes in treatment rather than illness evolution, we repeated the analyses controlling for age and antipsychotic use at each assessment point (Table 3). Age had no effect on psychopathology after accounting for time since baseline. Antipsychotic use was associated with worse GAF, inexpressivity, and apathy-asociality overall, but with less disorganization and mania/excitement in schizophrenia. Also, antipsychotic use was associated with lower reality distortion in schizophrenia, but greater symptoms in other psychoses. This pattern may indicate medication side effects or self-selection (e.g., sicker participants are more likely to receive antipsychotics long-term). Adjustment for these two variables did not change findings for illness trajectories except that three slopes became non-significant in other psychoses and two became non-significant in MoDWP. Adjustments for various other potential confounds had little impact on the pattern of results (see eResults and eTable 4).

Discussion

We found that schizophrenia exhibits substantial and consistent decline over the two decades following first hospitalization. Mean GAF score of this group decreased from 49 (at 6-month assessment) to 36 (20-year assessment), and the latter score indicates impairment in reality testing, communication, or pervasive disability. With regard to specific symptom dimensions, worsening was observed in apathy-asociality, reality distortion, and disorganization. MoDWP were less severe than schizophrenia (mean GAF of 65 at 6-month), but they also showed worsening on GAF, apathy-asociality, and disorganization. This decline was smaller (e.g., nine points on GAF) than that in schizophrenia. The decline began five to eight years after the first hospitalization. Depression and mania showed no signs of worsening in any disorders. Overall, 74% participants with schizophrenia were continuously ill, compared to 14% of MoDWP, and most of the rest of these groups experienced multiple episodes during the 20-year interval.

Our results align with the Kraepelinian view of schizophrenia as following a downward trajectory. The illness worsened gradually, but in the second decade the decline become noticeable. Treatment initiation improved reality distortion and disorganization substantially, as indicated by change from baseline to month 6, but symptoms gradually returned, undoing many treatment gains by year 20. Contrary to Kraepelin’s observations, MoDWP also experienced significant worsening, although less pronounced than schizophrenia and limited to negative symptoms (reality distortion and disorganization remained low). Of note, mood symptoms showed a different pattern, either improving or remaining consistently low.

Importantly, heterogeneity within diagnostic groups was substantial, and a number of participants achieved good outcomes (GAF>60 at year 20): 42% of MoDWP, 31% of other psychoses, and 4% of schizophrenia. We previously reported that rank-order stability over 20 years is modest for negative symptoms (test-retest r ~ .40) and low for reality distortion and disorganization (r ~ .20)11. Thus, trajectories of individual participants varied around the mean trend for their group with some increasing and others decrease.

To minimize misclassification, a common problem early in the course of psychosis17, we used consensus diagnoses based on 10 years of observation. Such diagnoses are very accurate but are influenced by illness course. To examine this confounding, we repeated analyses using 6-month diagnoses. This had little impact on trajectories of schizophrenia, other than moderating the increase of psychotic symptoms somewhat. In contrast, other disorders looked consistently worse when 6 month diagnoses were used. This pattern can be explained by initial misclassification of schizophrenia cases as non-schizophrenia psychoses. Nevertheless, illness course is integral to diagnostic criteria (e.g., 6 months of symptoms are required for schizophrenia diagnosis) and some circularity is inherent in comparing course of diagnostic groups.

Trajectories of reality distortion were notable in that symptoms worsened in schizophrenia, despite consistently high rates of antipsychotic medication use across the two decades (~80% at each wave). This pattern is consistent with suggestions that antipsychotics may lose some of their effectiveness in the long-term and may even lead to paradoxical effects27,28 perhaps due to treatment non-adherence and relapses29. Also, changes in specific medication prescribed or its dose may contribute to this finding. Our study cannot directly test these possibilities as they require an experimental design.

Present findings paint a bleaker picture than the DOSMeD study, where only 29% of participants with schizophrenia were continuously ill and more than half had GAF>60 after two decades7. A variety of factors distinguish the U.S. from other countries included in DOSMeD study (India, Russia, Japan, England, Ireland, and Czech Republic). Availability of family support and community integration may contribute to differences in outcomes8, but a particularly salient issue is access to treatment. The Suffolk County cohort received community services typical of the U.S. and experienced a substantial unmet need for care30, which may account for poor outcomes especially compared to countries with universal health care.

On the other hand, our results are consistent with meta-analyses that found outcome in schizophrenia to be almost universally poor 31,32. Moreover, a systematic review of FEP studies found that during first decade of illness outcomes in treatment studies (mean GAF=66) were much better than in observational studies (mean GAF=50), and the latter are consistent with initial outcomes in the present cohort. The current study extends these reviews by documenting timing and pace of decline across multiple symptom dimensions.

Our findings are also consistent with evidence of accelerated neurodegeneration in schizophrenia33 that may underpin worsening negative symptoms. Poor physical health also may contribute to worse clinical course, as it limits daily functioning, impairs cognitive performance, and is common in psychotic disorders34. We observed significant effects of poor health in MoDWP but not in other groups (eTable 4). Furthermore, our results for MoDWP are consistent with studies that reported functional impairment and residual symptoms to be very common in psychotic bipolar disorder years after first admission35.

Current results should not be interpreted as an indication that good outcomes are out of reach. There is extensive evidence that aggressive treatment, especially psychotherapy and vocational rehabilitation, can substantially improve outcomes36–38. Moreover, 10-year follow-ups of FEP in Denmark and the United Kingdom, countries with universal access to psychiatric services, found relatively good outcomes with no evidence of decline and few continuously ill participants both in non-schizophrenia and schizophrenia groups5,6. It is possible that with better care, outcomes in the U.S. would mirror those of Denmark and the United Kingdom.

This study is the first in the U.S. to follow an epidemiologically-defined large FEP cohort long-term. Nevertheless, it has several limitations. First, it is limited to one geographic location and does not necessarily reflect illness course in other societies. Nevertheless, present findings call attention to a glaring public health problem in the U.S. Second, attrition was non-negligible; 32% of survivors could not be contacted or refused participation. However, attrition analyses suggest that non-participants were largely similar to participants, except for slightly higher likelihood of being a minority and more severe psychotic symptoms at baseline, both risk factors for worse outcome29,39. Thus, the present results may underestimate severity of clinical course. Third, assessments began at first admission rather than first onset. Fortunately, length of pre-admission illness was short relative to the follow-up with median duration of untreated psychosis of 40 days (only 27% were ill for more than a year). Fourth, we did not measure mania symptoms dimensionally and had to rely on a proxy measure, BPRS Excitement. Fifth, the study focused on symptoms and global outcome, and did not consider dimensions of functioning. Functioning was beyond the scope of the present paper focused on symptom burden, but we are reporting several functional outcomes in another publication40.

Conclusions

Present results suggest an alarming public health problem, a high symptom burden in psychotic disorders that increases with time and ultimately may undo initial treatment gains. Previous studies suggest that better care may preempt this decline. In the U.S., psychotic disorders are associated with a large unmet need for care, and the current study highlights this shortcoming as an urgent priority. Reasons for the decline are unclear and numerous explanations exist. Greater research attention to mid and late course of psychotic disorders is needed to identify factors that drive this decline, just as it unfolds, and learn how to preempt it.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (MH44801 to E.J.B. and MH094398 to R.K.), Eli Lilly Corporation (grant to E.J.B.), and the Stanley Medical Research Institute (grant to E.J.B.). The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the participants and mental health community of Suffolk County for contributing their time and energy to this project. They are also indebted to dedicated efforts of study coordinators, interviewers for their careful assessments, and to the psychiatrists who derived the consensus diagnoses. Special thanks to Janet Lavelle for her many contributions to the study.

References

- 1.Kraepelin E, editor. Psychiatrie. 6. Leipzig, Germany: Barth; 1899. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGlashan TH. A selective review of recent north american long-term followup studies of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1988;14(4):515–542. doi: 10.1093/schbul/14.4.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zipursky RB, Reilly TJ, Murray RM. The myth of schizophrenia as a progressive brain disease. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(6):1363–1372. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menezes NM, Arenovich T, Zipursky RB. A systematic review of longitudinal outcome studies of first-episode psychosis. Psychol Med. 2006;36(10):1349–1362. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Austin SF, Mors O, Budtz-Jorgensen E, et al. Long-term trajectories of positive and negative symptoms in first episode psychosis: A 10year follow-up study in the OPUS cohort. Schizophr Res. 2015;168(1–2):84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morgan C, Lappin J, Heslin M, et al. Reappraising the long-term course and outcome of psychotic disorders: The AESOP-10 study. Psychol Med. 2014;44(13):2713–2726. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrison G, Hopper K, Craig T, et al. Recovery from psychotic illness: A 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:506–517. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.6.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hopper K, Harrison G, Wanderling J. Recovery from schizophrenia: An international perspective: A report from the WHO collaborative project, the international study of schizophrenia. Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrow M, Grossman LS, Jobe TH, Herbener ES. Do patients with schizophrenia ever show periods of recovery? A 15-year multi-follow-up study. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31(3):723–734. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanchard JJ, Cohen AS. The structure of negative symptoms within schizophrenia: Implications for assessment. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(2):238–245. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotov R, Foti D, Li K, Bromet EJ, Hajcak G, Ruggero CJ. Validating dimensions of psychosis symptomatology: Neural correlates and 20 year outcomes. Journal of abnormal psychology. doi: 10.1037/abn0000188. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liddle PF. The symptoms of chronic schizophrenia. A re-examination of the positive-negative dichotomy. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;151:145–151. doi: 10.1192/bjp.151.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuesta MJ, Peralta V. Integrating psychopathological dimensions in functional psychoses: A hierarchical approach. Schizophr Res. 2001;52(3):215–229. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00190-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Os J, Gilvarry C, Bale R, et al. A comparison of the utility of dimensional and categorical representations of psychosis. UK700 group. Psychol Med. 1999;29(3):595–606. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798008162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGrath J. Dissecting the heterogeneity of schizophrenia outcomes. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(2):247–248. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bromet EJ, Schwartz JE, Fennig S, et al. The epidemiology of psychosis: The suffolk county mental health project. Schizophr Bull. 1992;18(2):243–255. doi: 10.1093/schbul/18.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bromet EJ, Kotov R, Fochtmann LJ, et al. Diagnostic shifts during the decade following first admission for psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(11):1186–1194. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11010048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andreasen NC. The scale for the assessment of negative symptoms (SANS) Iowa City: The University of Iowa; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andreasen NC. The scale for the assessment of positive symptoms. Iowa City: The University of Iowa; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Overall JE, Gorham DR. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychological Reports. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB. The structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: History, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(8):624–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jablensky A, Sartorius N, Ernberg G, et al. Schizophrenia: Manifestations, incidence and course in different cultures. A world health organization ten-country study. Psychol Med Monogr Suppl. 1992;20:1–97. doi: 10.1017/s0264180100000904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotov R, Leong SH, Mojtabai R, et al. Boundaries of schizoaffective disorder: Revisiting kraepelin. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(12):1276–1286. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klein DN, Kotov R. Course of depression in a 10–year prospective study: Evidence for qualitatively distinct subgroups. journal of abnormal psychology. Course of depression in a 10-year prospective study: Evidence for qualitatively distinct subgroups. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2016;125:337–348. doi: 10.1037/abn0000147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muggeo VMR. Estimating regression models with unknown break points. Stat Med. 2003;22:3055–3071. doi: 10.1002/sim.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Model selection and multimodel inference: A practical information-theoretic approach. 2. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrow M, Jobe TH. Does long-term treatment of schizophrenia with antipsychotic medications facilitate recovery? Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(5):962–965. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wunderink L, Nieboer RM, Wiersma D, Sytema S, Nienhuis FJ. Recovery in remitted first-episode psychosis at 7 years of follow-up of an early dose reduction/discontinuation or maintenance treatment strategy: Long-term follow-up of a 2-year randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(9):913–920. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carbon M, Correll CU. Clinical predictors of therapeutic response to antipsychotics in schizophrenia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2014;16(4):505–524. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.4/mcarbon. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mojtabai R, Fochtmann L, Chang SW, Kotov R, Craig TJ, Bromet E. Unmet need for mental health care in schizophrenia: An overview of literature and new data from a first-admission study. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(4):679–695. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hegarty JD, Baldessarini RJ, Tohen M, Waternaux C, Oepen G. One hundred years of schizophrenia: A meta- analysis of the outcome literature. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1409–1416. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.10.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jääskeläinen E, Juola P, Hirvonen N, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2013;39:1296–1306. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fusar-Poli P, Smieskova R, Kempton MJ, Ho BC, Andreasen NC, Borgwardt S. Progressive brain changes in schizophrenia related to antipsychotic treatment? A meta-analysis of longitudinal MRI studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(8):1680–1691. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Hert M, Correll CU, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10:52–77. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Treuer T, Tohen M. Predicting the course and outcome of bipolar disorder: A review. Eur Psychiatry. 2010;25(6):328–333. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alvarez-Jimenez M, Parker AG, Hetrick SE, McGorry PD, Gleeson JF. Preventing the second episode: A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological trials in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):619–630. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hegelstad WT, Larsen TK, Auestad B, et al. Long-term follow-up of the TIPS early detection in psychosis study: Effects on 10-year outcome. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169:374–380. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11030459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE early treatment program. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2016;173:362–372. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15050632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morgan C, Charalambides M, Hutchinson G, Murray RM. Migration, ethnicity, and psychosis: Toward a sociodevelopmental model. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2010;36:655–664. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Velthorst E, Fett AK, Reichenberg A, Perlman G, van Os J, Bromet EJ, Kotov R. The 20-year longitudinal trajectories of social functioning in individuals with psychotic disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15111419. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.