Abstract

Background

There are many systematic reviews and meta-analyses (SRs) of interventions for family caregivers of persons with Alzheimer's disease or a related dementia. A challenge when synthesizing the efficacy of dementia caregiver interventions is the potential discrepancy in how they are categorized. The objective of this study was to systematically examine inconsistencies in how dementia caregiver interventions are classified.

Methods

We searched Ovid Medline®, Ovid PsycINFO®, Ovid Embase®, and the Cochrane Library to identify previous SRs published and indexed in bibliographic databases through January 2015. Following a graphical network analysis, open-coding of classification definitions was conducted. A descriptive analysis was then completed to examine classification consistency of individual interventions across SR grouping labels.

Results

Twenty-three SRs were identified. A graphical network analysis revealed a significant amount of overlap in individual studies included across SRs, but stark differences in how reviews labeled or categorized them. The qualitative content analysis identified seven themes; one of these, content of the intervention, was used to compare classification consistency. When subjecting the classification of interventions to descriptive empirical analysis, extensive inconsistency was apparent.

Conclusions

The substantial inconsistency in how dementia caregiver interventions are classified across SRs has hindered the science and practice of dementia caregiver interventions. Specifically, accurate reporting of intervention components and SRs would allow for more precise assessments of efficacy as well as a fuller determination of how caregiver interventions can best yield benefits for caregivers and persons with dementia.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, dementia, carers, interventions, randomized controlled trial, systematic reviews, meta-analysis

Introduction

The negative emotional, psychological, and health effects of caring for a relative with Alzheimer's disease or a related dementia (ADRD) and the need to facilitate the rewards and meaningfulness of this role has resulted in a range of clinical interventions to support family caregivers (Gaugler et al., 2014). The number of empirical evaluations of dementia caregiver interventions has grown considerably, and there now exist many meta-analyses and systematic reviews (SRs) that consider a range of family caregiver (e.g. stress, depression) and person with ADRD (e.g. behavior problems, time to institutionalization) outcomes (Gitlin and Hodgson, 2015). A potential concern, however, when synthesizing or comparing the efficacy of dementia caregiver interventions is inconsistency in how they are classified (Czaja et al., 2003; Schulz et al., 2010). This can result in confusion when ascertaining whether certain types of interventions are more efficacious than others for given caregiver and care-recipient outcomes, and may also inhibit the ability to implement these programs into routine clinical care settings (Gitlin and Hodgson, 2015; Gaugler and Burgio, 2016). The actual extent of this problem, however, is unknown. The objective of this study was to systematically describe the classification of individual interventions in existing SRs to examine possible inconsistencies, with the aim of advancing the literature to facilitate more effective categorization.

Prior classifications of dementia caregiver interventions

Syntheses of the dementia caregiver intervention literature suggest that an ad hoc classification approach is utilized that is based largely on the general function of interventions (Pinquart and Sörensen, 2006). Organizations that serve as clearinghouses for dementia caregiver intervention information, such as the Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregiving or the Alzheimer's Disease Supportive Services Program in the USA, do not categorize dementia caregiver interventions by type (Maslow, 2012). However, some researchers have advocated for a more detailed approach when describing intervention components. In the ADRD caregiving context, Czaja et al. (2003) “decomposed” the various multi-component interventions of the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer's Caregiver Health (REACH) program into the following dimensions: the primary entity (e.g. caregiver, person with ADRD, environment); the functional domain (e.g. skills, behavior of the person with ADRD); and delivery characteristics including mode of delivery, frequency and intensity, group or individual delivery, and similar aspects. Results across the six decomposed REACH interventions for 1,222 dementia caregivers indicated that targeting caregiver behavior (e.g. ensuring and validating caregivers' abilities to implement effective behavioral approaches) reduced caregiver depression (Czaja et al., 2003).

Schulz and colleagues have built on this earlier work to create a taxonomy that categorizes health-related behavior change interventions. Their taxonomy focuses on delivery characteristics including method of contact between intervention provider and recipient; materials used in the delivery of the intervention; location of intervention delivery; duration and intensity; extent of intervention “scripting;” sensitivity of intervention to participant background, skills, and abilities; interventionist training; adaptability; and treatment implementation (Schulz et al., 2010). The content and goals of the intervention, such as specific strategies to improve outcomes of participants and mechanisms that operate to achieve targeted outcomes, are additional domains of the taxonomy.

Advancing syntheses of evidence for dementia caregiver interventions

It is not apparent whether the recommendations of Schulz and others have influenced the reporting of individual dementia caregiver interventions or the classification strategies of existing SRs. More specifically, an ongoing issue when conducting SRs of dementia caregiver interventions is that many individual evaluations do not report extensive details about their context, structure, or process. For these reasons, authors of SRs must often rely on subjective approaches and definitions to categorize interventions. This can lead to wide disparities in how dementia caregiver interventions are classified across SRs, and such ambiguity may continue to hinder efforts to synthesize the effectiveness of various interventions and translate these programs into practice settings.

As early as 2001, a comparison of two SRs of dementia caregiver interventions that included largely similar review questions, study inclusion criteria, and years of review found that only 44% of controlled trials appeared in both reviews (Charlesworth, 2001). To our knowledge, no study to date has systematically described the extent of misclassification of individual dementia caregiver interventions across SRs. Until the discipline better understands how individual interventions are categorized, conclusions of efficacy of different types of interventions will continue to vary considerably. For these reasons, the current study employed visual data method and network analysis (Kolaczyk and Csárdi, 2014), qualitative methods, and empirical description to examine how specific interventions are classified across SRs.

Methods

Search strategy

We searched Ovid Medline®, Ovid PsycINFO®, Ovid Embase®, and the Cochrane Library to identify previous SRs published and indexed in bibliographic databases through January 2015. Our search strategy (Online Supplemental Material) included relevant medical subject headings and natural language terms for concepts related to dementia and caregivers. These terms were combined with filters to select SRs. Bibliographic database searches were supplemented with backward citation searches of relevant SRs. Two independent investigators (EJ and MB) reviewed titles and abstracts of search results. Citations deemed eligible by either investigator underwent full-text screening. EJ and MB independently screened full texts to determine if the inclusion criteria (Table 1) were met. Discrepancies in screening decisions were resolved by consultation between investigators and, if necessary, consultation with a third investigator (TPS). We documented the exclusion reason for reviews at the full-text screening stage (Online Supplemental Material). EJ and MB assessed the quality of eligible SRs using AMSTAR (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews) (Shea et al., 2009). Quality assessment of SRs included items such as a priori design, dual review, and individual study risk-of-bias assessment. Results of previous SRs used in lieu of de novo extraction were updated with new data when additional relevant studies were identified (Viswanathan et al., 2012).

Table 1. Study inclusion criteria.

| CATEGORY | CRITERIA FOR INCLUSION |

|---|---|

| SR inclusion criteria | Systematic reviews that include:

|

| SR objective | To synthesize evidence on CG interventions on CG psychosocial health outcomes and CR institutionalization |

| Study design | SRs that at a minimum assessed and reported risk of bias of eligible trials |

| Time of publication | Literature published from 1994 forward (reflects interventions used today) |

| Publication type | Published in peer reviewed journals |

| Language of publication | English |

Note: SR = systematic review; RCT = randomized controlled trial; CG = caregiver; CR = care-recipient.

We extracted information from SRs that were relevant to address the taxonomy of CG interventions and were assessed as fair or high quality. Study quality reflects the belief that the study methods yield unbiased results. To that effect, and consistent with Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Evidence Based Practice Center methodology, we excluded low-quality reports from the analysis to report the best available evidence (Viswanathan et al., 2012). EJ identified relevant SR characteristics (search dates, inclusion criteria, number and types of studies included, intervention categorization, and outcomes reported) and entered them into an evidence table. Definitions of intervention types as defined by the SR authors were then extracted. A database using bibliographic management software that contained the SRs and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of dementia caregiver interventions included in each SR was then created.

Evaluation and extraction of intervention classifications

We initially identified the original grouping categories used in each SR and the individual studies included in each group. Using a network analysis framework, we graphically plotted results by showing connections (i.e. common studies) between the original SR grouping labels. The first and third authors (JEG and TPS) then conducted open-coding of intervention grouping definitions in SRs that matched the inclusion criteria. Both authors compared their individual codes for inter-rater reliability. We used an inductive (data-driven) approach for the analysis. As a result, we developed codes and identified categories and themes based on language used in the SRs, rather than fitting the data into preconceived categories. Coding and analyses proceeded in a manner largely similar to that described by Charmaz (2004). Our approach is similar to grounded theory, which focuses on developing emergent codes entirely from the data, but does not fully adhere to grounded theory's all-inductive and iterative approach. Specifically, to develop codes, JEG and TPS read definitions and used “line-by-line” open coding, which entails closely examining each line of text and assigning codes to reflect the meaning(s) contained in it (Charmaz, 2004). Codes were arranged into categories, or groups of similar codes under one label. We then grouped categories into themes. To help organize the data, we used the NVivo 10 software package (QSR International Pty Ltd., 2012).

We then empirically described the consistency of intervention classification across SRs. Using the themes identified in open coding, we compared the individual studies included in common themes across reviews and noted discrepancies between SRs. Where possible, we identified the reason for the discrepancy (e.g. differences in search dates or differences in study inclusion criteria). Discrepancies that could not be identified nor explained were considered an inconsistency and are reported here.

Results

Search results

Our search identified 220 citations, of which 80 required full-text review after title and abstract screening. Of the 80 full-text SRs screened, we identified 26 eligible SRs. Three of these were assessed as poor quality. We extracted information from the remaining 23 SRs (Online Supplemental Material). On average, reviews included 20.21 (SD = 21.44) studies and categorized studies into 2.74 (SD = 2.13) groupings (n = 63). The average grouping included 7.17 (SD = 7.07) studies. Table 2 presents the intervention grouping categories in each review and the number of studies included in each category.

Table 2. Intervention grouping categories and studies included in each category (n = 23).

| SYSTEMATIC REVIEW | CATEGORY: DEFINED WITHIN STUDY | NUMBER OF STUDIES IN GROUP |

|---|---|---|

| Brasure et al., 2015 | Interventions targeting caregiver knowledge and skills: Interventions that primarily target caregiver knowledge and have a secondary target of improving caregiver skills. | 2 |

| Interventions targeting caregiver knowledge and affect: Interventions that primarily target caregiver knowledge and have a secondary target of improving caregiver affect. | 1 | |

| Interventions targeting caregiver skills and knowledge: Interventions that primarily target caregiver skills and have a secondary target of improving caregiver knowledge. | 6 | |

| Interventions targeting caregiver skills and behaviors: Interventions that primarily target caregiver skills and have a secondary target of improving the persons with dementias behavior. | 9 | |

| Interventions targeting caregiver skills and behaviors: Interventions that primarily target caregiver skills and have a secondary target of improving the persons with dementias behavior. | 2 | |

| Parker et al., 2008 | Psycho-educational: Structured information about dementia and caregiver issues. Applies new knowledge to help solve problems. Support may be offered as a secondary component. | 13 |

| Support: Support for challenge caregiving and provide opportunities for sharing personal feels and alleviate social isolation. | 7 | |

| Multi-component: A combination of at least psycho-educational and support. | 12 | |

| Other-interventions: Includes cognitive behavioral therapy and exercise. | 2 | |

| Li et al., 2013 | Group coping skills interventions (without behavioral activation): Group based interventions for family caregivers based on cognitive-behavioral techniques (e.g. behavior modification, cognitive reframing, assertive communication, and relaxation). Interventions provide coping skills, problem solving, and stress management in combination with information on dementia and care planning. | 3 |

| Group coping skills interventions with behavioral activation: Group-based interventions for family caregivers based on behavioral activation techniques that teach caregivers to develop pleasant activities. | 2 | |

| Remotely delivered behavioral management: Coping and behavioral management interventions that are delivered through video. | 2 | |

| Individual behavioral management: Interventions delivered on an individual basis using cognitive-behavioral principles. | 1 | |

| Dyadic interventions: Interventions delivered to both the caregiver and person with dementia. | 1 | |

| Cognitive stimulation therapy training: Caregivers are trained to delivery cognitive stimulation therapy to the person with dementia. | 1 | |

| Griffin et al., 2013 | Family assisted approaches: Interventions that train families to change or manage patient behavior. | 7 |

| Family focused cognitive based therapy that includes skills building, family coping, and problem solving to address patient behavior and family issues: Interventions that provided support or counseling for family members and train family member to effectively manage patient symptoms or behaviors. | 7 | |

| Olazarán et al., 2010 | Caregiver education: Interventions that provide coping skills to caregivers in individual or group sessions. | 38 |

| Caregiver support:Insufficient information provided to determine definition. | 9 | |

| Respite care:Insufficient information provided to determine definition. | 2 | |

| Case management for caregiver:Insufficient information provided to determine definition. | 7 | |

| Multi-component for person with dementia and caregiver: Interventions that provide in-home counseling or support groups. | 24 | |

| Multi-component for caregiver:Insufficient information provided to determine definition. | 16 | |

| Elvish et al., 2013 | Psychoeducational-skill building: Interventions that provide education to caregivers about dementia and provide coping skills for managing emotional difficulties. | 8 |

| Psychotherapy-counseling: Interventions that provided psychotherapy or counseling individually or in groups. | 1 | |

| Multi-component: Interventions that combine theoretically different approaches. | 6 | |

| Technology-based interventions: Interventions that that use technology (e.g. telephone) as a significant delivery mechanism for the intervention. | 5 | |

| Van't Leven et al., 2013 | Dyadic psychosocial interventions: Interventions that target psychosocial outcomes and are delivered in-person between a care professional and a person with dementia and their caregiver. | 26 |

| Boots et al., 2014 | Internet based education and support: Website with information and support on caregiving. | 8 |

| Internet based strategies: Website with caregiving strategies. | 1 | |

| Website with telephone support:Insufficient information provided to determine definition. | 1 | |

| Website with email support:Insufficient information provided to determine definition. | 2 | |

| Website with individual work and exchange with other caregivers:Insufficient information provided to determine definition. | 6 | |

| Jensen et al., 2015 | Educational interventions: Interventions that teach skills for dementia caregiving (e.g. communication skills and coping strategies). | 7 |

| Eggenberger et al., 2013 | Communication skills training for informal caregivers: Interventions that provide training to family caregivers in groups or individually to improve care interactions. | 3 |

| Communication training to train formal caregivers to then train informal caregivers: Interventions (group or individual) that provide training to family caregivers through professional caregivers to improve care interactions. | 1 | |

| Pimouguet et al., 2010 | Case management: Interventions that involve a case manager providing advocacy over time, support, information about caregiving services, and financial and legal advice to a caregiver. | 12 |

| Hurley et al., 2014 | Meditation: Interventions that use medication based methods (e.g., mantra repetition, mindfulness-based methods, and yoga meditation). | 8 |

| Orgeta and Miranda-Castillo, 2014 | Physical Activity in Caregivers: Interventions that promote physical activity in dementia caregivers. | 4 |

| Smith and Greenwood, 2014 | Peer Support: Interventions that employ volunteers with prior caregiving experience to support current caregivers. | 3 |

| Befriending: Interventions that employ volunteers without prior caregiving experience to befriend current caregivers. | 1 | |

| Lins et al., 2014 | Telephone Counseling: Interventions that use telephones to provide caregivers with support and provide resources for addressing problems. | 11 |

| Maayan et al., 2014 | Respite care: The temporary provision of care to give informal caregivers relief. | 5 |

| Corbett et al., 2012 | Information Provision: Interventions in which the primary component included information and advice to caregivers. | 13 |

| Vernooij-Dassen et al., 2011 | Group or individual cognitive reframing: Interventions that address caregiver's beliefs about their responsibility and their own need for support combined with information about the disease process. | 11 |

| Spijker et al., 2008 | Support programs for caregivers: Multicomponent individualized support programs. | 13 |

| Smits et al., 2007 | Combined interventions: Interventions aimed at both the person with dementia and informal caregiver. | 25 |

| Selwood et al., 2007 | Education: Interventions that only provide information about dementia. | 16 |

| Individual/group caregiver coping strategies (<6 sessions; ≥6 sessions): Interventions that teach coping strategies, stress management, problem appraisal, and problem solving combined with education. | 16 | |

| Individual/group behavioral management techniques (<6 sessions; ≥6 sessions): Interventions that teach behavioral management theory, methods for managing problem behaviors, and coping strategies. | 27 | |

| Supportive therapy: A mix of interventions (e.g. computer-based program and telephone support). | 9 | |

| Cooper et al. 2007 | Cognitive behavioral therapy:Insufficient information provided to determine definition. | 5 |

| Behavioral management techniques:Insufficient information provided to determine definition. | 3 | |

| Group counseling: Insufficient information provided to determine definition. | 1 | |

| Provision of IT support for caregivers:Insufficient information provided to determine definition. | 1 | |

| Groups involving relaxation/yoga:Insufficient information provided to determine definition. | 2 | |

| Exercise therapy: Insufficient information provided to determine definition. | 2 | |

| Providing additional professional support for caregivers:Insufficient information provided to determine definition. | 3 | |

| Respite care:Insufficient information provided to determine definition. | 3 | |

| Pusey and Richards, 2001 | Service configuration: Interventions that altered service configuration compared to usual care. | 3 |

| Technology: Interventions using computers or telephone to deliver education, decision support, and communication. | 2 | |

| Group based psychosocial interventions: Interventions delivered in a group setting that provide education and behavioral management techniques. | 8 | |

| Individual psychosocial interventions: Interventions delivered individually that provide education and behavioral management techniques. | 9 |

Note: See Online Supplemental Material for full citation of each review.

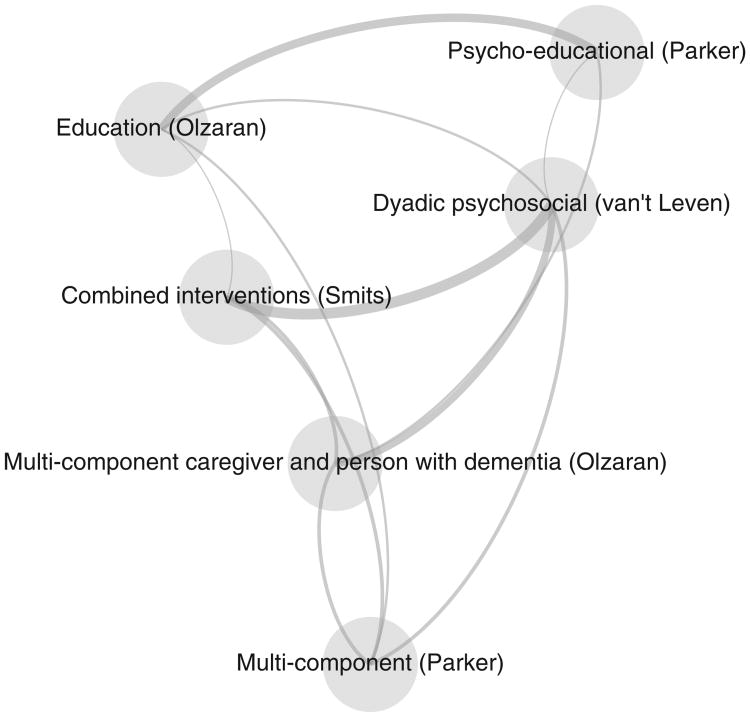

Descriptive network analysis of studies and groupings

Of the 232 individual studies identified across the 23 SRs, each individual study was included in 2.01 SRs on average (SD = 1.36). Often the same individual study was classified differently in separate reviews. In Figure 1, the nodes indicate the groupings used to categorize studies in a SR. To minimize “noise,” Figure 1 only shows groupings that had at least 30 different connections. A line connecting two groupings indicates that the groups included at a minimum a single study (in some cases, there was multiple overlap of individual studies which is indicated by thicker weighted lines). For example, Parker et al. (2008) (grouping label = multi-component) and Olazarán et al. (2010) (grouping label = education) both included the same study in their reviews but categorized the study differently. Figure 1 reveals a significant amount of overlap in the studies included across SRs, but also noticeable graphical differences in how SRs labeled or categorized studies.

Figure 1.

Network analysis of dementia caregiver intervention classification across systematic reviews.

Qualitative content analysis of intervention classifications

Our qualitative content analysis identified the following seven themes: (1) content of the intervention (the clinical content and focus of ADRD caregiver interventions; this included coded categories such as case management, education, cognitive stimulation, psychosocial support, skills building, and similar areas that reflected the content of reviewed interventions); (2) delivery method (whether dementia caregiver interventions were delivered face-to-face, through computer or telephone, video, or web-based platforms); (3) intended audience (individual, dyadic, or group); (4) standardized versus tailored content; (5) structure/type (multi-domain or singular content); (6) intensity (fewer than six or more than six sessions); and (7) source of delivery (professional-or peer-led). Table 3 provides additional detail of the categories identified within each theme.

Table 3. Categories and themes of existing dementia caregiver intervention classifications.

| THEME | CATAGORY |

|---|---|

| Content | Case management |

| Cognitive stimulation | |

| Cognitive/behavioral | |

| Education | |

| Physical activity intervention | |

| Psychosocial support | |

| Relaxation-yoga | |

| Respite | |

| Skills building | |

| Delivery technology | Computer or telephone delivery |

| Telephone consultation | |

| Video delivery | |

| Web-based | |

| Intended-audience | Dyadic |

| Family member Group | |

| Individual | |

| Standardized-tailored | Standardized |

| Tailored | |

| Types-structure | Combined |

| Single | |

| Intensity | Greater than or equal to six sessions |

| Less than six sessions | |

| Who delivers | Caregivers are trained to deliver intervention |

| Professional support for caregivers |

Analysis of inconsistent classification of interventions across reviews

Focusing on the content theme identified in our qualitative content analysis (as this domain was most commonly used to group intervention types) in SRs, we selected and compared reviews that: (i) utilized similar definitions of intervention content; (ii) identified intervention studies from similar yearly intervals (e.g. 1990–2010); and (iii) used similar inclusion criteria (e.g. a sole focus on RCTs) to determine the degree of overlap or misclassification across reviews. Due to space considerations, citations of the individual interventions categorized across SRs are not included here; they are available from the authors.

The first intervention content area considered was respite (a service designed to give caregivers “time off” from responsibilities either at-home or at another site). Three SRs utilized similar definitions when grouping and synthesizing results of respite for dementia caregivers (Cooper et al., 2007; Olazarán et al., 2010; Maayan et al., 2014). Olazarán and colleagues included two studies of respite, while Maayan et al. included four and Cooper and colleagues included three. Only one study was consistent across the three reviews. In contrast, four studies were included in at least one review but not the others. Furthermore, one study was included in two of the reviews, but was classified as respite in one and not the other.

Case management (e.g. “interventions that involve a case manager providing advocacy over time, support, information about caregiving services, and financial and legal advice to a caregiver;” Pimouguet et al., 2010) was the next grouping examined. Olazarán and colleagues included eight trials and Pimouguet et al. included 12 (Olazarán et al., 2010; Pimouguet et al., 2010). Nine studies were included in Pimouguet et al. that were not included in Olazarán and colleagues, even when accounting for non-overlapping search dates. Two studies in Olazarán et al. and one in Pimouguet et al. were unique to those respective reviews and not included in another SR, and an additional 12 studies were included in either Olazarán et al. or Pimouguet et al. but not in any other review.The next content category examined was physical activity, which classified interventions that promote exercise or other physical activities for dementia caregivers. Two SRs considered physical activity interventions (Cooper et al., 2007; Orgeta and Miranda-Castillo, 2014). Orgeta and colleagues included four interventions in this particular category while Cooper et al. included two. Two studies were consistent between the two reviews. Relaxation and yoga was another content classification but was only included in one review (Cooper et al., 2007). This SR only included two studies in this category, with one not grouped in any other SR.

Skills building was a common classification across reviews. Eight SRs included skills building classifications, although the content definitions varied (Selwood et al., 2007; Olazarán et al., 2010; Eggenberger et al., 2013; Elvish et al., 2013; Griffin et al., 2013; Li et al., 2013; Brasure et al., 2015; Jensen et al., 2015). Nonetheless, no intervention studies were consistent across all seven reviews. Sixty-one studies were reported in only one of the SRs that considered skills building interventions. Nine interventions were reported in two reviews, and eight were reported in three SRs. In contrast, 45 interventions were inconsistently classified in a skills-based grouping in one review and a different category in another.

Education (e.g. information provision) was included as a category in eight SRs (Pusey and Richards, 2001; Selwood et al., 2007; Parker et al., 2008; Elvish et al., 2013; Brasure et al., 2015; Jensen et al., 2015). Although there was less overlap of inclusion dates reported across these reviews, no individual caregiver intervention study was consistent between all SRs. There were 70 individual studies reported in only one review, 15 in two, four in three, and three studies reported across four of the SRs. In contrast, there were a total of 42 studies that were included in an education-based grouping in one review and in a non-education grouping in another SR.

Four SRs were identified that classified cognitive behavioral interventions, and as with psycho-educational interventions, there were no studies that were consistent across all four reviews (Cooper et al., 2007; Vernooij-Dassen et al., 2011; Griffin et al., 2013; Li et al., 2013). Twenty studies were included in only one review, three were reported in two reviews, and one was reported in three reviews. Another 22 individual intervention studies were classified in a cognitive-behavioral therapy category in one of four SRs but were classified as another type in a different review. Eight studies that were published after 2005 (i.e. outside of the Cooper et al. search date range) were included in only one of the other three SRs.

Among the six reviews that included a psychosocial category, there were no studies that were consistent across reviews (although it is important to note that dates of inclusion varied widely; Cooper et al., 2007; Parker et al., 2008; Olazarán et al., 2010; Elvish et al., 2013; Griffin et al., 2013; Van't Leven et al., 2013). Fifty-four studies were only reported in one review, whereas ten studies were reported in two reviews. Thirty-nine studies were classified as “psychosocial” in one of six reviews but were then classified in an altogether different category in other SRs.

Discussion

Even when considering time frames and inclusion criteria, the inconsistency of dementia caregiver intervention classification across SRs was striking. A general pattern seemed to emerge where the more complex the clinical content of a given intervention (e.g. skills building approaches), the more irregular the classification across reviews. In many instances, an intervention was categorized in one review as one type, but then classified as a different type in another SR (even if the same category was utilized in the latter review); in others, many individual interventions were included in one SR but not another. The extent of discrepancy is likely due to a number of factors, including the range of rigor adopted when conducting SRs (e.g. varying search strategies), a more narrow focus in some reviews than others leading to alternative classifications of individual interventions, and the highly subjective criteria utilized when categorizing interventions.

Some inconsistency is understandable; for example, SRs may be guided by questions that require alternative grouping of interventions. However, even these explanations are unlikely to account for the amount of discrepancy that currently exists. This inconsistency looms as a major concern: There are a number of efforts throughout the USA and elsewhere to translate evidence-based interventions for ADRD caregivers to advance the quality of existing long-term services and supports for family caregivers and persons with dementia. The current state of the evidence, however, hinders overall assessments of “what works for whom” when determining the efficacy of interventions and whether there are certain interventions or intervention types that result in more positive outcomes for caregivers or persons with ADRD than others (Gitlin and Hodgson, 2015).

In defense of current and past SRs, the reporting standards of individual dementia care-giver interventions could be considered less than optimal. Although process data may exist in the grey literature (i.e. unpublished reports or manuscripts), even the most careful synthesis of existing dementia caregiving interventions is unlikely to fully characterize the administration method, clinical content, delivery approach, and other key characteristics of selected programs. The quality of reporting continues to hamper attempts to determine not only whether a given type of dementia caregiver intervention is efficacious, but also how it achieves or does not achieve its stated benefits. As the themes identified in our qualitative content analysis suggest, there are a number of important components (content of the intervention; delivery method; source of delivery; standardized vs. tailored content; structure/type; intensity; and intended audience) that should serve as a reporting framework of individual dementia caregiver interventions. Reporting such information in individual studies will likely result in more consistent classification of single studies in subsequent SRs.

There also exist clear, compelling recommendations that to date have not been adopted consistently: those of Schulz and colleagues outlining frameworks to decompose, identify, and report core components and processes of dementia caregiver interventions (Schulz, 2001; Czaja et al., 2003; Schulz et al., 2010). Our content analysis of existing intervention definitions used in SRs confirmed these recommendations. It is not immediately clear why the reporting recommendations of Schulz and colleagues have not been uniformly adopted. The evolution of dementia caregiver interventions can be traced from the evaluation of brief, circumscribed, singular component interventions that demonstrated modest to minimal efficacy for key caregiver and care-recipient outcomes to those that include multiple treatment components that are delivered over longer periods of time (Gitlin and Hodgson, 2015). Although multi-component protocols tended to demonstrate more consistent significant effects on key outcomes, the drive to establish efficacy outpaced process-oriented evaluations or component analyses to better understand mechanisms of benefit (which may be less palatable to some peer-reviewed journals). The empirical results reported here offer further support for the adoption of comprehensive reporting standards (via extramural grant mechanisms and/or peer-reviewed journal requirements) to yield greater understanding for why certain dementia caregiver interventions do or do not exert benefits for families. They would also facilitate improved syntheses of the literature to provide consistent conclusions of efficacy and opportunities for comparative effectiveness research. Expert consensus panels (that include the original principal investigators of interventions), use of more rigorous SR methods, or similar strategies could also be employed to result in more consistent intervention classifications.

In addition to the qualifications described above, there are several limitations to our evidence-based synthesis. An open coding methodology was used to identify themes across reviews. While there was strong consensus between coders, others may have interpreted the coding results differently. The primary conclusions of our analysis advocate for use of reporting standards. However, the existing reporting standards are not without limitations themselves (e.g. they may be time consuming or require additional information that do not fit within journal word limits). Although existing criteria were used to ensure comparisons of intervention classifications across SRs, there may be other unobserved reasons that explain why inconsistent categorization occurred.

The implications of our findings extend beyond the performance of meta-analyses or SRs of the literature to clinical settings. The evidence-base of dementia caregiver interventions has advanced to the point where many of these programs are now in translation in various community and clinical settings (Gitlin et al., 2015; Wethington and Burgio, 2015). However, there exist a number of barriers that have hindered efficacious dementia caregiver interventions from reaching the number of families that they should. For example, many clinical and community-based service providers who are ideal candidates to translate dementia caregiver interventions require improved information to guide their decision-making when selecting a given intervention for their setting and clients (Maslow, 2012; Burgio and Gaugler, 2016). In particular, key information that could guide such decision-making includes more effective categorization of intervention types that better informs whether certain approaches are more appropriate than others for a given set of outcomes. Improved reporting and analysis of interventions could also help organizations identify components that are most essential to improving outcomes for persons with dementia and their family caregivers. To date, there is a distinct lack of analysis of intervention components among established, evidence-based interventions to ascertain what aspects drive positive outcomes (Burgio and Gaugler, 2016). As emphasized in our findings, improved classification of and rigorous reporting of intervention components could not only help to facilitate an overall understanding of dementia caregiver intervention efficacy, but may also help to inform more robust translational efforts.

Conclusion

Moving forward, reporting standards of dementia caregiving interventions and SRs require substantial enhancements. Comprehensive and transparent reporting of various intervention domains would benefit future research by facilitating consistent classification of individual interventions in SRs, as would greater rigor in the conduct of SRs themselves. Moreover, improvements in reporting would likely have important clinical ramifications: Many practitioners, when seeking to translate or implement an ADRD caregiver intervention in their community or healthcare setting, could use improved reporting of intervention content, design, and delivery to inform their decisions as to whether a given program is feasible and appropriate. A fuller accounting of a given intervention's clinical components could help organizations avoid the adoption of programs that require more extensive resources and expertise than anticipated. Scientific outlets that publish and disseminate the results of dementia caregiver interventions could also feature process evaluations or similar reports that could better guide implementation efforts beyond traditional outcome reporting.

A considerable gap between evidence and clinical practice continues to persist in dementia (Chodosh et al., 2007), and generating higher quality evidence regarding the efficacy of caregiver interventions could help to bridge this gap and facilitate the translation of these programs in clinical contexts. Due to inconsistency in how dementia caregiver interventions are categorized across SRs, whether certain interventions are more or less effective for various caregivers remains opaque. This lack of clarity has hindered the science and practice of dementia caregiver interventions from achieving their considerable potential.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research reported here was supported by grant K18HS022445-02 to Dr. Gaugler from the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None.

Description of authors' roles: J. E. Gaugler was responsible for all aspects of the study, including the design, qualitative analysis, interpretation of findings, and the writing of this paper. E. Jutkowitz conducted the evidence-based synthesis, the graphical network analysis, and the descriptive analysis of intervention classification across SRs. T. P. Shippee provided assistance in the evidence-based review of SRs, conducted the qualitative content analysis with J. E. Gaugler, provided input into the design of the paper and its interpretation, and assisted with reviewing the paper. M. Brasure provided considerable assistance in conducting the evidence-based synthesis and also reviewed the paper.

Supplementary Material: To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1041610216001514.

References

- Boots LM, de Vugt ME, van Knippenberg RJ, Kempen GI, Verhey FR. A systematic review of Internet-based supportive interventions for caregivers of patients with dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2014;29:331–344. doi: 10.1002/gps.4016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasure M, et al. Nonpharmacologic Interventions for Agitation and Aggression in Dementia Comparative Effectiveness Review. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota; 2015. Prepared by the Minnesota Evidence-Based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2012-00016-I. [Google Scholar]

- Burgio LD, Gaugler JE. Caregiving for the chronically ill: state of the science and future directions. In: Burgio LD, Gaugler JE, Hilgeman MM, editors. The Spectrum of \Family Caregiving for Adults and Elders with Chronic Illness. New York: Oxford University Press; 2016. pp. 258–278. [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth GM. Reviewing psychosocial interventions for family carers of people with dementia. Aging & Mental Health. 2001;5:104–106. doi: 10.1080/13607860120038401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Grounded theory. In: Nagy Hesse-Biber S, Leavy P, editors. Approaches to Qualitative Research A Reader on Theory and Practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 496–521. [Google Scholar]

- Chodosh J, et al. Caring for patients with dementia: how good is the quality of care? results from three health systems. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55:1260–1268. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01249.x. doi:JGS1249 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C, Balamurali TB, Selwood A, Livingston G. A systematic review of intervention studies about anxiety in caregivers of people with dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;22:181–188. doi: 10.1002/gps.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett A, et al. Systematic review of services providing information and/or advice to people with dementia and/or their caregivers. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2012;27:628–636. doi: 10.1002/gps.2762. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/gps.2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czaja SJ, Schulz R, Lee CC, Belle SH REACH Investigators. A methodology for describing and decomposing complex psychosocial and behavioral interventions. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18:385–395. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggenberger E, Heimerl K, Bennett MI. Communication skills training in dementia care: a systematic review of effectiveness, training content, and didactic methods in different care settings. International Psychogeriatrics. 2013;25:345–358. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212001664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elvish R, Lever S, Johnstone J, Cawley R, Keady J. Psychological interventions for carers of people with dementia: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 2013;13:106–125. [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Burgio LD. Caregiving for individuals with Alzheimer's disease and related disorders. In: Burgio LD, Gaugler JE, Hilgeman MM, editors. The Spectrum of \Family Caregiving for Adults and Elders with Chronic Illness. New York: Oxford University Press; 2016. pp. 15–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Potter T, Pruinelli L. Partnering with caregivers. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 2014;30:493–515. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2014.04.003. doi:S0749-0690(14)00038-X[pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Hodgson N. Caregivers as therapeutic agents in dementia care: the evidence-base for interventions supporting their role. In: Gaugler JE, Kane RL, editors. Family Caregiving in the New Normal. San Diego: Academic Press; 2015. pp. 305–356. [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Marx K, Stanley IH, Hodgson N. Translating evidence-based dementia caregiving interventions into practice: state-of-the-science and next steps. Gerontologist. 2015;55:210–226. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin JM, et al. Effectiveness of Family and Caregiver Interventions on Patient Outcomes Among Adults with Cancer or Memory-Related Disorders: A Systematic Review. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley RV, Patterson TG, Cooley SJ. Meditation-based interventions for family caregivers of people with dementia: a review of the empirical literature. Aging & Mental Health. 2014;18:281–288. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.837145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen M, Agbata IN, Canavan M, McCarthy G. Effectiveness of educational interventions for informal caregivers of individuals with dementia residing in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2015;30:130–143. doi: 10.1002/gps.4208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolaczyk ED, Csárdi G. Statistical Analysis of Network Data with R. New York: Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Cooper C, Austin A, Livingston G. Do changes in coping style explain the effectiveness of interventions for psychological morbidity in family carers of people with dementia? A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Psychogeriatrics. 2013;25:204–214. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212001755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lins S, et al. Efficacy and experiences of telephone counselling for informal carers of people with dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;9:CD009126. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009126.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maayan N, Soares-Weiser K, Lee H. Respite care for people with dementia and their carers. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;1:CD004396. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004396.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow K. Translating Innovation to Impact: Evidence-Based Interventions to Support People with Alzheimer's Disease and Their Caregiver at Home and in the Community. Washington, DC: Administration for Community Living; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Olazarán J, et al. Nonpharmacological therapies in Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review of efficacy. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2010;30:161–178. doi: 10.1159/000316119;10.1159/000316119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orgeta V, Miranda-Castillo C. Does physical activity reduce burden in carers of people with dementia? a literature review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2014;29:771–783. doi: 10.1002/gps.4060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker D, Mills S, Abbey J. Effectiveness of interventions that assist caregivers to support people with dementia living in the community: a systematic review. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare. 2008;6:137–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2008.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimouguet C, Lavaud T, Dartigues JF, Helmer C. Dementia case management effectiveness on health care costs and resource utilization: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. 2010;14:669–676. doi: 10.1007/s12603-010-0314-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Helping caregivers of persons with dementia: which interventions work and how large are their effects? International Psychogeriatrics. 2006;18:577–595. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206003462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusey H, Richards D. A systematic review of the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for carers of people with dementia. Aging & Mental Health. 2001;5:107–119. doi: 10.1080/13607860120038302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software, Version 10 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R. Some critical issues in caregiver intervention research. Aging & Mental Health. 2001;5:S112–S115. doi: 10.1080/13607860120044882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Czaja SJ, McKay JR, Ory MG, Belle SH. Intervention taxonomy (ITAX): describing essential features of interventions. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2010;34:811–821. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2010.34.6.811[pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selwood A, Johnston K, Katona C, Lyketsos C, Livingston G. Systematic review of the effect of psychological interventions on family caregivers of people with dementia. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;101:75–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea BJ, et al. AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62:1013–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R, Greenwood N. The impact of volunteer mentoring schemes on carers of people with dementia and volunteer mentors: a systematic review. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. 2014;29:8–17. doi: 10.1177/1533317513505135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits CH, de Lange J, Droes RM, Meiland F, Vernooij-Dassen M, Pot AM. Effects of combined intervention programmes for people with dementia living at home and their caregivers: a systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;22:1181–1193. doi: 10.1002/gps.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spijker A, et al. Effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions in delaying the institutionalization of patients with dementia: a meta-analysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56:1116–1128. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van't Leven N, et al. Dyadic interventions for community-dwelling people with dementia and their family caregivers: a systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics. 2013;25:1581–1603. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213000860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernooij-Dassen M, Draskovic I, McCleery J, Downs M. Cognitive reframing for carers of people with dementia. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011;11:CD005318. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005318.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M, et al. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Methods Guide for Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Bethesda, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wethington E, Burgio LD. Translational research on caregiving: missing links in the translation process. In: Gaugler JE, Kane RL, editors. Family Caregiving in the New Normal. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2015. pp. 193–210. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.