Abstract

BACKGROUND

Few studies have analyzed factors that influence longitudinal changes in patient-perceived satisfaction during the recovery period following robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) for prostate cancer. We investigated variables that were associated with patient-perceived satisfaction after RARP using the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) survey.

METHODS

Of 175 men who underwent RARP between 2010 and 2011, 140 men completed the EPIC questionnaire preoperatively and 3, 6 and 12 months postoperatively. On the basis of the EPIC question no. 32 (item number 80), patients were divided into four groups according to the pattern of satisfaction change at postoperative 3 and 12 months: satisfied to satisfied (group 1); satisfied to dissatisfied (group 2); dissatisfied to satisfied (group 3); and dissatisfied to dissatisfied (group 4). Longitudinal changes in EPIC scores over time in each group and differences in EPIC scores of each domain subscale between groups at each follow-up were analyzed. A linear mixed model with generalized estimating equation approach was used to identify independent factors that influence overall satisfaction among repeated measures from same patients.

RESULTS

On the basis of the pattern of satisfaction change, groups 1, 2, 3 and 4 had 103 (74.3%), 21 (15.0%), 11 (7.9%) and 5 (2.9%) patients, respectively. The factor that was associated with overall satisfaction was urinary bother (UB) (β = 0.283, 95% confidence interval (0.024, 0.543); P = 0.033) adjusted for other factors under consideration.

CONCLUSIONS

UB was the independent factor influencing patient-perceived satisfaction after RARP. During post-RARP follow-up, physician should have the optimal management for the patient’s UB.

Keywords: quality-of-life, expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) survey, patient satisfaction, prostate neoplasms, robotics

INTRODUCTION

Health-related quality-of-life (HRQOL) issues are becoming as important as cancer control in the treatment of localized prostate cancer.1 Patients often select primary treatment based on a modality’s impact on HRQOL, as the various therapeutic interventions may be accompanied by potential long-term treatment-related side effects, such as urinary, bowel and sexual dysfunction, which alter and presumably diminish HRQOL.2–6

Satisfaction with treatment outcome among patients with prostate cancer has been shown to be directly impacted by changes in HRQOL.7 One study found that almost 16 percent of patients previously treated with early stage prostate cancer expressed regret. These men were more likely to have worse general and disease-specific HRQOL when compared with those without regret.8 Other studies have reported that decisional regret in the treatment of localized prostate cancer increased significantly over time demonstrating the possible impact of treatment side effects on regret9, and that regret following robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) can be independently predicted by a men’s age, baseline functional status, perioperative outcomes and postoperative (postop) urinary and erectile function.10

However, most of these studies8–10 examined treatment-related regret, and did not evaluate treatment satisfaction, which is mainly derived from perceived differences between expectations and experience.11 To date, few studies have reported on detailed factors that influence longitudinal changes in patient-perceived satisfaction during the recovery period following RARP for prostate cancer.

In this study, we analyzed the longitudinal change of patient-perceived satisfaction during the recovery period following RARP, and investigated factors that influence overall satisfaction, as assessed by the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) survey.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and data collection

Between January 2010 and February 2011, a prospective longitudinal survey on HRQOL was conducted in men who underwent RARP for localized prostate cancer at our institute after obtaining institutional review board approval. EPIC questionnaires were administered after informed consent and collected preoperatively and at 3, 6 and 12 months after surgery.

RARP was performed according to a standardized surgical technique by a single surgeon (IYK). Foley catheter was typically removed on postop day no. 7. No patients in this cohort underwent cystogram before foley catheter removal. Recovery of continence was defined as being completely pad free based on the patient’s interview and EPIC question no. 5 (Q5, item number 27). Potency was defined as the ability to achieve penetration and maintain erection in =50% of attempts based on question no. 2 and 3 on sexual health inventory for men regardless of the use of a PDE5 inhibitor.12,13 To determine the effect of other factors including postop adverse events and biochemical recurrence (BCR) on patient-perceived satisfaction, medical charts were reviewed for postop adverse events, serial serum PSA during follow-up visits and any additional adjunctive therapy following initial treatment. Patients were considered to have a BCR if two consecutive PSAs were rising and greater than 0.2 ng ml−1 after radical prostatectomy.

Questionnaire and measurement

The EPIC survey is a robust prostate cancer HRQOL instrument that complements prior instruments by measuring a broad spectrum of urinary, bowel, sexual and hormonal symptoms, thereby providing a unique tool for comprehensive assessment of HRQOL issues important in contemporary prostate cancer management.14 HRQOL was measured using the 50-item EPIC, a validated, self-administered questionnaire derived from the University of California, Los Angeles Prostate Cancer Index (UCLA-PCI).15 Multi-item scale scores were transformed linearly to 0–100 scale, with higher scores representing better HRQOL. We excluded hormonal domain from the analysis because this domain specifically measure symptoms related to androgen deprivation therapy and their related bother.

Overall satisfaction was measured with a five-level Likert scale ranging from ‘extremely dissatisfied’ to ‘extremely satisfied’ by the response to EPIC Q32 (item number 80).11 Original responses are recoded into a 100-point scale, with higher scores representing higher levels of satisfaction. Patients responding that they were ‘satisfied’ or ‘extremely satisfied’ with their treatment for prostate cancer were classified as satisfied, whereas all other patients were classified as dissatisfied.11

The patients were grouped according to the pattern of satisfaction change: satisfied at both 3 and 12 months after surgery (Group 1); satisfied at 3 months but dissatisfied at 12 months (Group 2); dissatisfied at 3 months but satisfied at 12 months (Group 3); and dissatisfied at both 3 and 12 months (Group 4). Longitudinal changes in each EPIC domain subscale scores in each group were evaluated and the differences in EPIC scores of each domain subscale were analyzed between groups at each follow-up to assess the factors associated with changes in satisfaction during the follow-up.

Statistical analysis

A repeated measures analysis of variance with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction determined the longitudinal changes of each domain subscale in each group. Correlations of each domain subscale with the degree of overall satisfaction were measured at each follow-up using the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, and it was also stratified by age. A linear mixed model was performed to identify independent domain subscales that influence overall satisfaction. Parameters of the model were estimated using a generalized estimating equation. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 software (IBM, Somers, NY, USA), and a P-value >0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Among 175 men who underwent RARP during the study period, 143 men completed the EPIC questionnaire preoperatively and at 3, 6 and 12 months after surgery. Patients who were treated with adjuvant radiotherapy and/or androgen deprivation therapy (n = 3) were excluded from the analysis. Therefore, the final cohort comprises 140 men. Baseline characteristics of our study cohort are shown in Table 1. Median age for the entire cohort was 59 years (range 41–77 years). Among the four groups, there were no significant differences with respect to age, body mass index, preoperative PSA, preoperative American Urological Association Symptom Score, race, prostate weight, Gleason’s score, pathologic stage or surgical margin status (Table 1). Overall, 111 (79.3%) and 29 (20.7%) patients had pT2 and pT3 disease, respectively. Recovery rates of urinary continence were 73, 89 and 97%, and the potency rates were 7, 28 and 61% at 3, 6 and 12 months after surgery for the overall cohort, respectively. Overall satisfaction rates (EPIC Q32, item number 80) at 3, 6 and 12 months after surgery were 88.6, 85.3, and 81.4%, respectively.

Table 1.

Clinical and pathological characteristics of patients

| Variables | Total (n = 140) | Group 1 (n = 103) | Group 2 (n = 21) | Group 3 (n = 11) | Group 4 (n = 5) | P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.356 | |||||

| Mean | 59.3±7.4 | 58.8±7.1 | 60.6±8.4 | 62.3±8.2 | 56.8±7.8 | |

| Median (range) | 59 (41–77) | 59 (41–75) | 60 (45–77) | 63 (43–75) | 56 (49–67) | |

| Body mass index (kg m−2) | 28.5±5.2 | 28.2±4.2 | 29.2±4.3 | 30.7±11.7 | 25.5±4.0 | 0.259 |

| Preoperative PSA (ng ml−1) | 5.6±2.7 | 5.3±2.3 | 6.5±3.9 | 6.2±3.3 | 6.2±2.3 | 0.197 |

| Preoperative AUASS | 8.6±6.7 | 8.0±6.3 | 9.8±7.9 | 11.2±7.3 | 12.0±3.7 | 0.174 |

| Preoperative SHIM score | 18.6±7.4 | 19.0±7.2 | 18.3±7.8 | 16.6±7.7 | 16.8±10.6 | 0.731 |

| Prostate weight (g) | 49.1±15.6 | 50.5±16.8 | 46.1±11.9 | 42.0±9.2 | 47.5±5.2 | 0.272 |

| Race | 0.056 | |||||

| White | 119 (85%) | 91 (88.4%) | 15 (71.4%) | 8 (72.7%) | 4 (80%) | |

| Black | 15 (10.7%) | 10 (9.7%) | 5 (23.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (20%) | |

| Asian | 6 (4.3%) | 2 (1.9%) | 1 (4.8%) | 3 (27.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Pathologic Gleason score | 1.000 | |||||

| 2–6 | 63 (45.0%) | 49 (47.6%) | 10 (47.6%) | 2 (18.2%) | 2 (40%) | |

| 7 | 60 (42.8%) | 43 (41.7%) | 8 (38.1%) | 8 (72.7%) | 1 (20%) | |

| 8–10 | 17 (12.2%) | 11 (10.7%) | 3 (14.3%) | 1 (9.1%) | 2 (40%) | |

| Pathologic stage | 1.000 | |||||

| ≤pT2 | 111 (79.3%) | 83 (80.6%) | 17 (81%) | 7 (63.6%) | 4 (80%) | |

| ⩾pT3 | 29 (20.7%) | 20 (19.4%) | 4 (19%) | 4 (36.4%) | 1 (20%) | |

| Positive surgical margin | 18 (12.8%) | 13 (12.6%) | 3 (14.3%) | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (20%) | 0.686 |

| Hospital stay (days) | 1.000 | |||||

| 1 | 131 (93.6%) | 96 (93.2%) | 21 (100%) | 10 (90.9%) | 4 (80%) | |

| 2 | 8 (5.7%) | 6 (5.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (20%) | |

| ⩾3 | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

Abbreviations: AUASS, American Urological Association Symptom Score; SHIM, Sexual Health Inventory for Men.

Group 1: the patients who were satisfied at both 3 and 12 months after surgery. Group 2: the patients who were satisfied at postop 3 months but dissatisfied at postop 12 months. Group 3: the patients who were dissatisfied at postop 3 months but satisfied at postop 12 months. Group 4: the patients who were dissatisfied at both 3 and 12 months after surgery.

P-value between four groups.

Serial changes of each EPIC domain subscale scores over time according to the study group

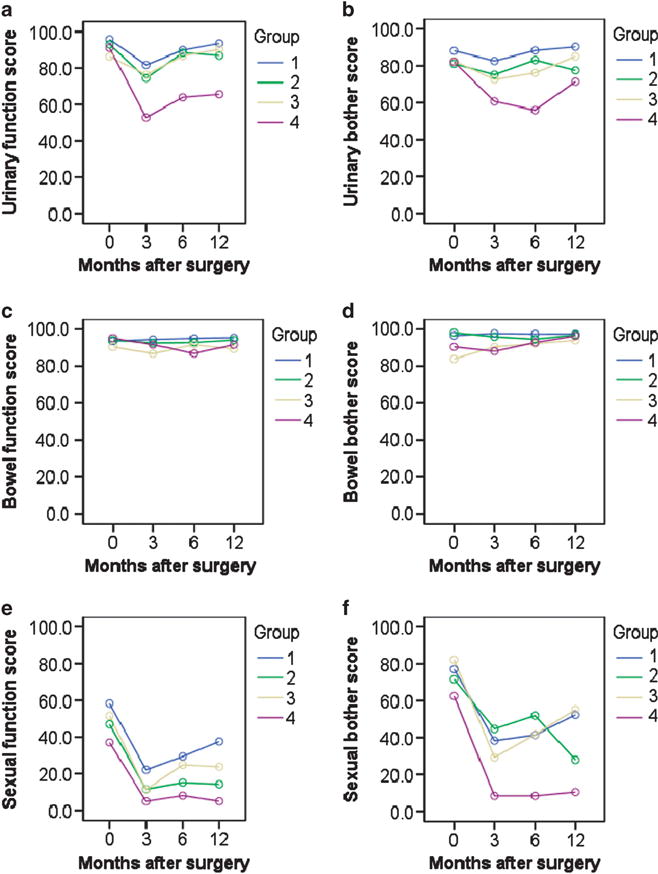

On the basis of the pattern of satisfaction change, groups 1, 2, 3 and 4 had 103, 21, 11 and 5 patients, respectively. Trends for EPIC score changes were represented in Figure 1 and created by repeated measures analysis of variance test.

Figure 1.

Longitudinal changes of each EPIC domain subscale scores over time, stratified according to the study group. The patients are grouped according to the pattern of satisfaction change: satisfied at both 3 and 12 months after surgery as group 1 (n = 103), satisfied at 3 months but dissatisfied at 12 months as group 2 (n = 21), dissatisfied at 3 months but satisfied at 12 months as group 3 (n = 11) and dissatisfied at both 3 and 12 months as group 4 (n = 5). (a) Urinary function, (b) urinary bother, (c) bowel function, (d) bowel bother, (e) sexual function, (f) sexual bother.

Correlations between the degree of overall satisfaction and individual EPIC domain subscale

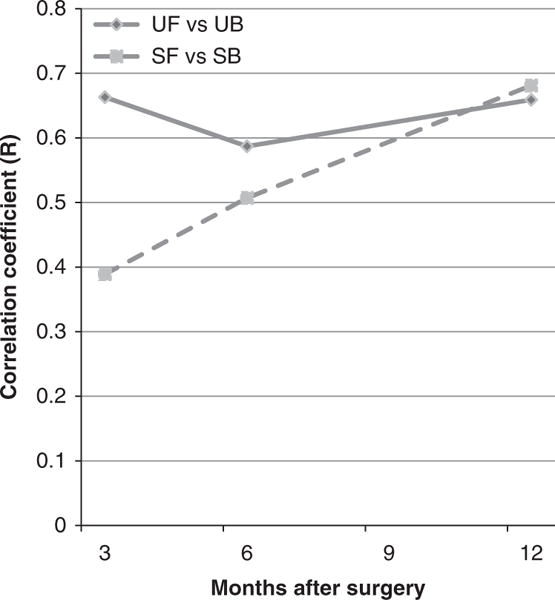

When examined at each follow-up, urinary bother (UB) and sexual bother (SB) showed significant correlation with overall satisfaction during the entire follow-up periods, whereas SB was not correlated with overall satisfaction at postop 3 and 6 months among the patients with older age (>60), but became significantly correlated with overall satisfaction at postop 12 months (Table 2). Correlation between urinary function and UB was high at each follow-up, whereas the correlation between sexual function (SF) and SB was relatively low at postop 3 months, but became higher over time (Figure 2). In univariate analyses, associations with most factors under consideration were statistically significant (P<0.05). In multivariable modeling, only UB was associated with overall satisfaction adjusted for age, urinary function, UB, bowel bother, bowel function, SF and SB (Table 3).

Table 2.

Correlations between the degree of overall satisfaction and individual EPIC domain subscale

| Postoperative F/U periods | Urinary function | Urinary bother | Bowel function | Bowel bother | Sexual function | Sexual bother | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Three months | Total | 0.155 | 0.224** | 0.195* | 0.219** | 0.058 | 0.196* |

| ≤60 years | 0.280* | 0.287* | 0.211 | 0.352** | 0.161 | 0.346** | |

| >60 years | 0.013 | 0.164 | 0.176 | 0.107 | −0.055 | 0.046 | |

| Six months | Total | 0.174* | 0.309** | 0.080 | 0.108 | 0.173* | 0.270** |

| ≤60 years | 0.169 | 0.391** | 0.092 | 0.200 | 0.306** | 0.321** | |

| >60 years | 0.257* | 0.285* | 0.070 | 0.071 | 0.139 | 0.235 | |

| Twelve months | Total | 0.238** | 0.249** | 0.151 | 0.111 | 0.319** | 0.331** |

| ≤60 years | 0.229* | 0.228* | 0.113 | 0.143 | 0.455** | 0.411** | |

| >60 years | 0.265* | 0.271* | 0.204 | 0.084 | 0.219 | 0.251* |

P <0.05.

P <0.01.

Figure 2.

Correlations between urinary bother (UB) and urinary function (UF) and between sexual bother (SB) and sexual function (SF) at each follow-up.

Table 3.

Factors of each EPIC domain subscale that influence the overall satisfaction including stratification by age using the multivariable modeling with linear generalized estimating equations

| Parameters | Univariate analyses

|

Multivariate analyses

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (β) | 95% CI | P | Estimate (β) | 95% CI | P | |||

| Age (≤60 years vs >60 years) | 0.402 | −5.046 | 5.850 | 0.885 | −2.193 | −7.319 | 2.933 | 0.402 |

| Urinary function | 0.200 | 0.040 | 0.360 | 0.014 | −0.052 | −0.274 | 0.170 | 0.646 |

| Urinary bother | 0.338 | 0.164 | 0.513 | <0.001 | 0.283 | 0.024 | 0.543 | 0.033 |

| Bowel function | 0.209 | −0.024 | 0.441 | 0.079 | 0.069 | −0.170 | 0.308 | 0.570 |

| Bowel bother | 0.427 | 0.002 | 0.853 | 0.049 | 0.069 | −0.364 | 0.502 | 0.754 |

| Sexual function | 0.226 | 0.119 | 0.333 | <0.001 | 0.146 | −0.018 | 0.311 | 0.081 |

| Sexual bother | 0.147 | 0.057 | 0.238 | 0.001 | 0.048 | −0.078 | 0.174 | 0.452 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Other factors related to overall satisfaction

Overall, the rate of postop adverse events was low. Transient urinary retention was reported in 11 patients (8%), bladder neck contracture in 3 patients (2%), paralytic ileus in 2 patients (1.4%), Clostridium difficile colitis in 1 patient (0.7%), lymphocele in 1 patient (0.7%) and pelvic abscess in 1 patient (0.7%). None of these adverse events were statistically associated with overall satisfaction (data not shown). By 1 year after surgery, two patients experienced BCR and they were followed without adjunctive treatment.

DISCUSSION

Although many previous studies have focused on quantifying the burden of prostate cancer treatment with objective measures of HRQOL from the perspective of physicians,16–21 there has been a relative paucity of studies that measure patient-reported satisfaction with treatment outcome and HRQOL.7–11 Patient-perceived satisfaction about treatment depends on several factors, including functional and oncological outcomes,7–11 as well as many other relationship-oriented factors.22 In addition, patient-perceived distress with dysfunction after treatment can also have a substantial impact on the overall satisfaction with specific treatment. Recently, investigators showed the relationships of several variables to treatment-related regret following RARP.10 However, the dynamic level of regret with time and important component of the development of decisional regret could not be assessed due to the cross-sectional nature of their study.10 To our knowledge, our study is the first to evaluate dynamic changes of patient-perceived satisfaction over time during the recovery period after RARP based on a validated questionnaire survey administered longitudinally. Also, we identified factors that affect changes over time in patient-perceived satisfaction about the treatment of prostate cancer.

In our study, we found that the majority of men (74.3%) were satisfied at both 3 and 12 months after surgery. Twenty-three percent of patients showed changes in their satisfaction status during follow-up periods; 15% of patients were satisfied during the early postop period but became dissatisfied during the delayed period and 8% of patients were dissatisfied during the early period but eventually became satisfied during the delayed period. We presume that only UB has a substantial impact on patient-perceived satisfaction about the treatment with RARP during the early period follow-up after surgery. Moreover, UB appears to have an impact on patient-perceived satisfaction adjusted for other factors under consideration via multivariate analyses with linear generalized estimating equation.

Our findings demonstrate that bother subscale is a more robust indicator of patient-perceived satisfaction on treatment than functional subscale. Bother scores report the distress experienced by patients as a consequence of functional detriments with the degree to which they consider the detriments problematic. Therefore, the measurement of bother is an important component of understanding patient-reported HRQOL after prostate cancer treatment. Previously, Gore et al.23 reported that worse function scores were associated with severe urinary, sexual and bowel bother following prostate cancer treatment. However, our findings showed several important disparities with their study. First, function score did not always correlate with bother. Correlation between dysfunction and bother can change depending on the type of dysfunction and distress over time. Urinary function score highly correlates with UB all through the follow-up period, whereas SF score showed a relatively low degree of correlation with SB during the early postop period, although it became well correlated with SB over time. Gacci et al.24 also reported that although the correlation between urinary function and UB was strongly maintained through the long-term periods, the correlation between SF and SB was modestly maintained for 7 years, after which the function and bother appeared to have divergent trajectories. Second, although Gore et al.23 reported that the association between function score and severe bother was weakest for the sexual domains, our findings showed strong correlation between SF and SB with longer follow-up, which substantially affected the overall satisfaction during later postop follow-up. In our study, we identified several variables that directly relate to patient-perceived satisfaction following surgery. We found these factors to vary according to the patient’s age and length of follow-up.

Surgery-related adverse events were low and two patients (1.4%) had BCR by 1 year after surgery. In spite of statistical verification, we could not conclude any influence of these complications and oncological results on patient-perceived satisfaction due to the small number of patients with complications or BCR. Our study has several more limitations. Certain demographic parameters such as socioeconomic and educational status, which may be associated with patient-perceived satisfaction, were not available in our study. Among this cohort, a risk of selection or nonrespondent bias existed, as not responding to complete a survey could be an indication for dissatisfaction. However, the response rate was high (81.7%) in our study when compared with prior published studies.8–11 Low correlation coefficients for all comparisons were also one of the shortcomings in our current study. Therefore, these results should be validated in other independent groups comprising larger population to confirm our current results. Finally, the number of men who showed changes in their satisfaction status during the follow-up periods is relatively small in our study group. Nevertheless, we found consistent results from correlations of overall satisfaction with each EPIC domain subscale and multiple linear regression analysis.

In conclusion, the majority of men (74.3%) were satisfied at both 3 and 12 months following RARP. UB was the most important factor that influenced patient-perceived satisfaction about the treatment during the early recovery period after RARP and continued to influence satisfaction at longer-term follow-up. In this age of information technology, most prostate cancer patients are very familiar with the various outcomes related to HRQOL of RARP. We identified that the UB is the only factor affecting patients-perceived satisfaction adjusted for other factors under consideration. During post-RARP follow-up, physician should especially take care of the patients’ UB via optimal treatment. Additional long-term longitudinal follow-up will be needed to corroborate and confirm our findings.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Kangwon National University Research Fund Grant.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Fulmer BR, Bissonette EA, Petroni GR, Theodorescu D. Prospective assessment of voiding and sexual function after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma: comparison of radical prostatectomy to hormonobrachytherapy with and without external beam radiotherapy. Cancer. 2001;91:2046–2055. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010601)91:11<2046::aid-cncr1231>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeliadt SB, Ramsey SD, Penson DF, Hall IJ, Ekwueme DU, Stroud L, et al. Why do men choose one treatment over another?: a review of patient decision making for localized prostate cancer. Cancer. 2006;106:1865–1874. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altwein J, Ekman P, Barry M, Biermann C, Carlsson P, Fossa S, et al. How is quality of life in prostate cancer patients influenced by modern treatment? The Wallenberg Symposium. Urology. 1997;49:66–76. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80325-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madalinska JB, Essink-Bot ML, de Koning HJ, Kirkels WJ, van der Maas PJ, Schroder FH. Health-related quality-of-life effects of radical prostatectomy and primary radiotherapy for screen-detected or clinically diagnosed localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1619–1628. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penson DF, Litwin MS, Aaronson NK. Health related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. J Urol. 2003;169:1653–1661. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000061964.49961.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilt TJ, MacDonald R, Rutks I, Shamliyan TA, Taylor BC, Kane RL. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness and harms of treatments for clinically localized prostate cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:435–448. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, Sandler HM, Northouse L, Hembroff L, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1250–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark JA, Inui TS, Silliman RA, Bokhour BG, Krasnow SH, Robinson RA, et al. Patients’ perceptions of quality of life after treatment for early prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3777–3784. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diefenbach MA, Mohamed NE. Regret of treatment decision and its association with disease-specific quality of life following prostate cancer treatment. Cancer Invest. 2007;25:449–457. doi: 10.1080/07357900701359460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lavery HJ, Levinson AW, Hobbs AR, Sebrow D, Mohamed NE, Diefenbach MA, et al. Baseline functional status may predict decisional regret following robotic prostatectomy. J Urol. 2012;188:2213–2218. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schroeck FR, Krupski TL, Sun L, Albala DM, Price MM, Polascik TJ, et al. Satisfaction and regret after open retropubic or robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2008;54:785–793. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel VR, Sivaraman A, Coelho RF, Chauhan S, Palmer KJ, Orvieto MA, et al. Pentafecta: a new concept for reporting outcomes of robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2011;59:702–707. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hakimi AA, Blitstein J, Feder M, Shapiro E, Ghavamian R. Direct comparison of surgical and functional outcomes of robotic-assisted versus pure laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: single-surgeon experience. Urology. 2009;73:119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.08.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2000;56:899–905. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00858-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Litwin MS, Hays RD, Fink A, Ganz PA, Leake B, Brook RH. The UCLA Prostate Cancer Index: development, reliability, and validity of a health-related quality of life measure. Med Care. 1998;36:1002–1012. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199807000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tseng TY, Kuebler HR, Cancel QV, Sun L, Springhart WP, Murphy BC, et al. Prospective health-related quality-of-life assessment in an initial cohort of patients undergoing robotic radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2006;68:1061–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrer M, Suarez JF, Guedea F, Fernandez P, Macias V, Marino A, et al. Health-related quality of life 2 years after treatment with radical prostatectomy, prostate brachytherapy, or external beam radiotherapy in patients with clinically localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker WR, Wang R, He C, Wood DP., Jr Five year expanded prostate cancer index composite-based quality of life outcomes after prostatectomy for localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2011;107:585–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pardo Y, Guedea F, Aguilo F, Fernandez P, Macias V, Marino A, et al. Quality-of-life impact of primary treatments for localized prostate cancer in patients without hormonal treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4687–4696. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willis DL, Gonzalgo ML, Brotzman M, Feng Z, Trock B, Su LM. Comparison of outcomes between pure laparoscopic vs robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: a study of comparative effectiveness based upon validated quality of life outcomes. BJU Int. 2012;109:898–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Touijer K, Eastham JA, Secin FP, Romero Otero J, Serio A, Stasi J, et al. Comprehensive prospective comparative analysis of outcomes between open and laparoscopic radical prostatectomy conducted in 2003 to 2005. J Urol. 2008;179:1811–1817. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Street RL, Jr, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, Haidet P. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:198–205. doi: 10.1370/afm.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gore JL, Gollapudi K, Bergman J, Kwan L, Krupski TL, Litwin MS. Correlates of bother following treatment for clinically localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 2010;184:1309–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gacci M, Simonato A, Masieri L, Gore JL, Lanciotti M, Mantella A, et al. Urinary and sexual outcomes in long-term (5 + years) prostate cancer disease free survivors after radical prostatectomy. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:94–101. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]