Abstract

Background

Chronic graft-versus host disease (GVHD) is a chronic and disabling complication after hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT). It is important to understand the association of socioeconomic status (SES) with health outcomes in patients with chronic GVHD because of the impaired physical health and dependence on intensive and prolonged health care utilization needs in these patients.

Methods

We evaluated the association of SES with survival and quality of life (QOL) in a cohort of 421 patients with chronic GVHD enrolled on the Chronic GVHD Consortium Improving Outcomes Assessment study. Income, education, marital status and work status were analyzed to determine the association with patient-reported outcomes at the time of enrollment, non-relapse mortality (NRM) and overall mortality.

Results

Higher income (P=0.004), ability to work (P<0.001), and having a partner (P=0.021) were associated with better mean Lee chronic GVHD symptom scores. Higher income (P=0.048), level of education (P=0.044), and ability to work (P<0.001) were also significantly associated with better QOL and improved activity. In multivariable models, higher income and ability to return to work were both significantly associated with better chronic GVHD Lee symptom scores, but income was not associated with activity level, QOL, or physical/mental functioning. The inability to return to work (HR 1.82, P=0.019) was associated with worse overall mortality, while none of the SES indicators were associated with NRM. Income, race, and education did not show statistically significant associations with survival.

Conclusion

In summary, we did not observe an association between SES variables and survival or NRM in patients with chronic GVHD, though there was some association with patient reported outcomes such as symptom burden. Higher income status was associated with less severe chronic GVHD symptoms. More research is needed to understand the psychosocial, biologic, and environmental factors that mediate this association of SES with major HCT outcomes.

Keywords: hematopoietic cell transplantation, chronic GVHD, patient reported outcomes, socioeconomic status

INTRODUCTION

Socioeconomic status (SES) is a composite measure of economic, social, and work status, most commonly measured by income, education, and occupation.1, 2 Inequalities in healthcare among socioeconomic groups have been well described3, 4 and lower SES is reported to be a significant predictor for increased mortality in cancer patients likely due to factors as reduced access to health care services, lower quality of medical care, and later diagnosis and greater severity of illness.5–7 Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is a potentially curative therapy for a variety of malignant and benign hematologic diseases. Despite advances in practices which have led to improved outcomes and increasing numbers of long-term HCT survivors, poor SES continues to be a barrier to access to HCT and also a significant predictor for mortality in those who undergo transplantation.8–10 The largest analysis of SES with HCT outcomes reported by Baker et al demonstrated that patients with a median household income in the lowest quartile (<$34,700) had worse overall survival compared to patients with income in the highest quartile (>$56,300), independent of race and ethnicity.10 Another recent analysis reported an association between low SES and worse survival and non-relapse mortality (NRM) in HCT recipients alive and in remission for at least 1 year.11

Low SES denoted by low household income has also been associated with poor psychosocial functioning and health-related quality of life (QOL) in HCT survivors.12–14 It is thus not surprising that transplant, a highly specialized and expensive procedure, may be associated with economic disparities in survival and NRM.15 Current knowledge of specific barriers preventing access to HCT and post-HCT care is limited but a critical area of study.9

Chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a major complication for long-term survivors of HCT and is the leading cause of NRM in patients alive more than a year after HCT.16–19 Chronic health conditions related to chronic GVHD such as visual impairment, pulmonary dysfunction, endocrinopathies, and musculoskeletal disabilities may require significant multi-disciplinary support and resource utilization. Chronic GVHD results in impairments in QOL, psychological symptoms, and functional status.20, 21 Additionally, financial, employment, and insurance-related challenges which are integrally related with SES, specifically denoted by income may be other stressors influencing mental and physical well-being of these chronic GVHD patients. Given the prolonged trajectory of recovery in these patients with only 50% of patients being cured within 7 years and continued need for intensive medical care utilization/ immunosuppressive treatment, we hypothesize that the socioeconomic gradient may have a significant impact on the morbidity and mortality of this complication.22 We sought to evaluate the association of SES and other sociodemographic factors with clinical and patient-reported outcomes including QOL in a large prospective multicenter study of patients with chronic GVHD. We used income as the main indicator of SES since it has been used in most of the studies of SES in HCT and because a higher income may portend improved access to health care.

METHODS

Patients

The Chronic GVHD Consortium Improving Outcomes Assessment study is a prospective, multi-center observational study that collects data on a cohort of HCT recipients with chronic GVHD.23 Patients enrolled in the cohort are allogeneic HCT recipients with a diagnosis of chronic GVHD. Primary disease relapse, or inability to comply with study procedures are exclusion criteria. Cases were classified as incident (enrollment less than 3 months after the diagnosis of chronic GVHD) or prevalent (enrollment 3 or more months but less than 3 years after the diagnosis of chronic GVHD).

At enrollment, 3 months (for incident cases) and every 6 months thereafter, physicians and patients report standardized information on chronic GVHD organ involvement and symptoms. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each site (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, University of Minnesota, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Stanford University, Vanderbilt University, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center, Medical College of Wisconsin, Memorial Sloan Kettering, and Washington University), and all patients on the study provided informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This analysis includes data from 421 adult patients (≥18 years) who had complete data on the five primary sociodemographic variables, out of a total of 545 patients in the parent cohort. A comparison between the 421 study patients and 124 patients with missing sociodemographic data did not reveal any significant differences in baseline characteristics, QOL, GVHD severity and survival outcomes (data not shown). Only baseline patient-reported outcome data were analyzed due to non-availability of complete data at later time points at time of the study.

Patient-reported outcomes

Chronic GVHD symptom burden

The Lee Chronic GVHD Symptom Scale is a validated measure of chronic GVHD manifestations which consists of 30 questions about specific GVHD symptoms.24 In this study, only the summary score is analyzed which includes energy, skin, nutrition, lung, psychological, eye, and mouth symptoms. A higher score represents greater symptom burden.

Quality of life

Health-related QOL was assessed by the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Bone Marrow Transplant Scale (FACT-BMT).25 The FACT-BMT is a validated 37-item self-reported questionnaire that includes a 10 item Bone Marrow Transplant Subscale. The FACT- BMT score encompasses physical, social, emotional, functional, and BMT specific concerns; a higher score represents better QOL.

Physical and mental functioning

The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) is a 36-item self-report questionnaire that measures patient-reported health and functioning. The physical component score (PCS) and the mental component score (MCS) are two summary scales.26 PCS is a sum of individual measures of physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health, bodily pain, and general health. MCS is the sum of mental health, role limitations due to emotional problems, social functioning, and vitality. Higher scores represent better functioning, and are normalized relative to healthy individuals. The Human Activity Profile (HAP) consists of 94 questions measuring activity level. Three scores can be obtained from HAP: maximum activity score, adjusted activity score, and modified adjusted activity score (mAAS). Only mAAS was included in this analysis because it is the one score of the three that excludes activities that are restricted after HCT. Higher scores represent greater physical activity.

Physician reported GVHD severity

Chronic GVHD severity is calculated from individual organ scoring provided by clinicians using the National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus global composite scoring (mild, moderate, severe).27

Primary sociodemographic variables

Standardized questions were given to patients to assess sociodemographic information at the time of study enrollment. Patients recorded their approximate annual family income in the year before the transplant as <$15,000, 15,000–24,999, 25,000–49,999, 50,000–74,999, 75,000–99,999, or >100,000. These were categorized into three groups for analysis: <25,000 (low), 25,000–74,999 (medium), or >75,000 (high). Highest grade of education was analyzed as high school or less (grade school, some high school, or high school graduate), some college, college graduate, or post graduate degree. Current work status was analyzed as ability to work or go to school (in school full time, in school part time, working full time, working part time, unemployed/looking for work); at home (homemaker, retired, unemployed/not looking for work); or inability to work or go to school (on medical leave from work, disabled/unable to work, unemployed/not looking for work). In addition to this economic, social, and work status data which serve as measures of SES, we also analyzed the additional sociodemographic data: relationship status was analyzed as partnered (married/living with partner) or not partnered (single/never married, divorced, separated, widowed) and race was analyzed as White or other (Black, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, Hawaiian Native/Pacific Islander, all others).

Clinical outcomes

Mortality outcomes were calculated from the time of study registration. Overall mortality was defined as death from any cause. NRM was defined as death without prior relapse.

Statistical Methods

Associations were assessed among each of the five primary sociodemographic variables (income, education, work status, relationship status and race). Association of physician-reported severity of chronic GVHD was also assessed with the five sociodemographic variables. Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel correlation test was used for two ordinal variables, Cochran-Armitage trend test for one ordinal and one binary variable, and Chi-square test between two binary variables. Associations between physician reported chronic GVHD severity and patient-reported measures were assessed with the Jonckheere-Terpstra trend test.

Primary patient-reported outcomes included the Lee score, HAP-mAAS, FACT-BMT, and SF-36 PCS and MCS. Univariable associations of these outcomes with the five primary sociodemographic variables was assessed using the t-test (relationship status, race) or analysis of variance (income, education, current work status); boxplots are shown to describe the data. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to identify multivariable prognostic factors for each patient-reported outcome. Income was analyzed as the primary variable of interest and was included in all multivariable models regardless of significance. Stepwise regression analysis with a variable entry criterion of P<0.10 and a variable retention criterion of P<0.05 was used to determine which of the other four sociodemographic variables were associated with these outcomes after adjusting for income. Results for each multivariable model are presented as the model intercept and parameter estimate and standard error of the estimate for each variable in the model. A parameter estimate of 0 indicates the reference group for each variable; non-reference group parameter estimates indicate the change in patient-reported score compared to the reference group, adjusted for other variables in the model. The model intercept is the expected outcome value when all variables or risk factors in the model have a parameter estimate of 0.

Primary long-term outcomes included overall mortality (inverse of overall survival) and NRM. Risk factors were identified using Cox proportional hazards for overall mortality, and Fine and Gray competing risk regression for NRM. Income was included in all multivariable models regardless of significance. Stepwise analysis was done to identify other risk factors, as described above. Other potential variables included in this model were the other four sociodemographic variables, the five primary patient-reported outcomes, year of transplant, transplant center, primary diagnosis, disease risk (early, intermediate, or advanced based on primary diagnosis and disease status at the time of transplant), donor gender, donor relationship, HLA match, transplant conditioning intensity, source of hematopoietic progenitor cells, months from transplant to study enrollment, age, gender, HCT-CI comorbidity index, physician reported chronic GVHD severity, and type of chronic GVHD (classic or overlap). Results are presented as the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Analyses were conducted using SAS® software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Missing data were infrequent, and were not imputed. No adjustment was made for multiple testing. All P-values are two-sided and a P-value of <0.05 was considered as significant.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Characteristics of the 421 study patients included in this study are detailed in Table 1. Fifty eight percent were incident cases. Median time between onset of chronic GVHD to enrollment was 1.8 (range 0–32.5) months. Patients were enrolled from 8/2007 through 3/2012 and had a median of 52 months follow-up (range, 4–87). Physician rated NIH chronic GVHD severity in study patients was mild in 198 (47%), moderate in 183 (44%), and severe in 39 (9%). The cohort included 58% males and 87% Whites and the median age was 52 years (range 19–79). Fifty-two percent had a myeloablative transplant, 89% received peripheral blood stem cells and 57% had unrelated donors. Most patients (65%) in the cohort had classic chronic GVHD while 35% had both acute and chronic manifestations (overlap syndrome). Median time of onset from HCT was 6.7 (range 1.3–23.6) months for overlap syndrome and 8.2 (range 1.2–57.7) months for classic chronic GVHD.

Table 1.

Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Study Site, N (%) | |

| Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center | 186 (44) |

| Stanford University | 53 (13) |

| University of Minnesota | 42 (10) |

| Dana-Farber Cancer Institute | 40 (10) |

| Vanderbilt | 36 (9) |

| H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center | 32 (8) |

| Medical College of Wisconsin | 21 (5) |

| Memorial Sloan-Kettering | 8 (2) |

| Washington University | 3 (1) |

|

| |

| Months from transplant to chronic GVHD | |

| Mean ± SD | 9.2 ± 6.1 |

| Median (range) | 7.5 (1.2–57.7) |

|

| |

| Months from transplant to enrollment | 14.6 ± 8.6 |

| Median (range) | 12.1 (3.3–60.8) |

|

| |

| Age at enrollment, years | |

| Mean ± SD | 51 ± 12 |

| Median (range) | 52 (19–79) |

|

| |

| Gender, N (%) | |

| Male | 246 (58) |

| Female | 175 (42) |

|

| |

| Race, N (%) | |

| White | 366 (87) |

| Black | 10 (2) |

| Hispanic | 19 (5) |

| Other | 26 (6) |

|

| |

| Income, N (%) | |

| <$25,000 | 53 (13) |

| $25–74,999 | 152 (36) |

| ≥$75,000 | 216 (51) |

|

| |

| Highest level of education, N (%) | |

| Some high school | 13 (3) |

| High school graduate | 67 (16) |

| Some college | 116 (28) |

| College graduate | 123 (29) |

| Post-graduate degree | 102 (24) |

|

| |

| Current work status, N (%) | |

| Able to work or go to school | 126 (30) |

| At home | 96 (23) |

| Unable to work or go to school | 199 (47) |

|

| |

| Relationship status, N (%) | |

| Partnered (married/living with partner) | 312 (74) |

| Not partnered (divorced, single, widowed, other) | 109 (26) |

Income, education, work status, and relationship status of the study population are described in Table 1. 36% of patients had a household income of ≥$100,000, 81% had at least some college education, and 74% had a partner/significant other.

Associations among Primary Sociodemographic Variables

Higher income was associated with higher education (25%, 45%, and 67% of low, medium, and high income patients had at least a college degree; P<0.001), greater ability to work (15%, 23%, and 38% among low, medium, and high income; P<0.001), greater likelihood of being in a partnered relationship (42%, 65%, and 88% among low, medium, and high income; P<0.001), and greater likelihood of White race (81%, 81%, and 93% among low, medium, and high income; P<0.001). White race was also associated with being in a partnered relationship (77% versus 58% non-White; P=0.004). There were no significant associations between work status and education (P=0.33), relationship status (P=0.11) or race (P=0.25) or between education and relationship status (P=0.23) or race (P=0.71).

Interactions between pairs of SES variables occurring together in multivariable models were also assessed. The only significant interaction was that ability to work had a positive association with SF-36 MCS among patients with a partner but not among those without a partner.

Association of Primary Sociodemographic Variables with GVHD Severity and Patient-Reported Outcomes

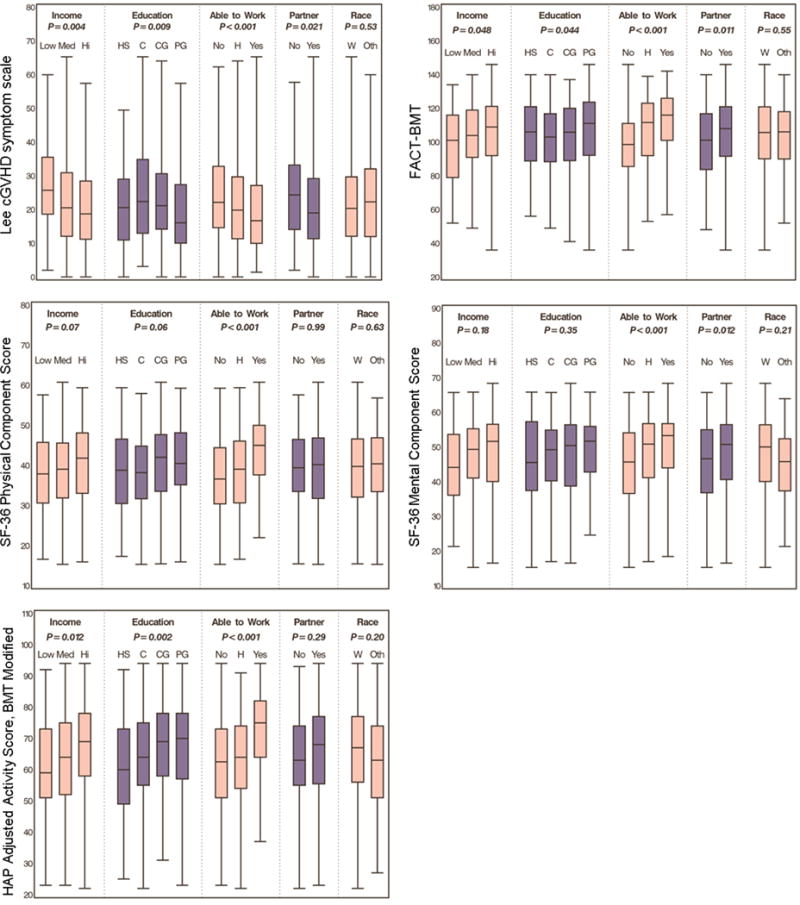

Figure 1 depicts univariable analysis of the association of sociodemographic variables with patient-reported GVHD severity and outcomes. Higher income, ability to work, and having a partner were associated with better mean Lee chronic GVHD symptom scores. Level of education was significantly associated with Lee symptoms scores, but the trend across levels was not consistent. Higher income, education, and ability to work were significantly associated with better QOL by FACT-BMT and better activity by the mAAS scores. None of the sociodemographic variables (income, P=0.53; ability to work, P=0.71; education, P=0.64; partner status, P=0.63; and race, P=0.74), were associated with physician-rated chronic GVHD severity.

Figure 1.

Association of SES variables and chronic GVHD symptoms, QOL, and functional and mental functioning. Line in the box plots represents the median value of the data.

In multivariable analysis, which includes income as a variable regardless of significance, higher income and the ability to return to work remained significantly associated with better Lee symptom scores (Table 2). However, income was not associated with activity level, QOL, or physical and mental functioning. The ability to return to work was associated with better QOL, activity level, and physical and mental functioning.

Table 2.

Multivariable models of Sociodemographic Variables and Patient-reported Outcomes

| Model/Variable | Parameter Estimate* (SE) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Patient-reported Overall Severity Score | ||

|

| ||

| Interceptǁ | 4.6 (0.3) | <0.001 |

|

| ||

| Income category | ||

| <$25,000 | 0 | – |

| $25–74,999 | −0.5 (0.4) | 0.15 |

| ≥$75,000 | −0.7 (0.4) | 0.06 |

|

| ||

| Lee cGVHD Symptom Score | ||

|

| ||

| Intercept | 28.8 (1.9) | <0.001 |

|

| ||

| Income Category | ||

| <$25,000 | 0 | – |

| $25–74,999 | −4.0 (2.1) | 0.05 |

| ≥$75,000 | −5.5 (2.0) | 0.006 |

|

| ||

| Current work/school status | ||

| Unable to work/school | 0 | – |

| At home | −3.3 (1.6) | 0.036 |

| Able to work/school | −5.2 (1.5) | <0.001 |

|

| ||

| HAP Adjusted Activity Score, BMT modified (mAAS) | ||

|

| ||

| Intercept | 57.6 (2.4) | <0.001 |

|

| ||

| Income category | ||

| <$25,000 | 0 | – |

| $25–74,999 | 0.2 (2.4) | 0.92 |

| ≥$75,000 | 1.3 (2.4) | 0.60 |

|

| ||

| Highest level of education | ||

| Some HS or HS grade | 0 | – |

| Some college | 0.2 (2.4) | 0.93 |

| College grade | 5.6 (2.2) | 0.010 |

| Post graduate degree | 4.7 (2.3) | 0.044 |

|

| ||

| Current Work/school status | ||

| Unable to work/school | 0 | – |

| At home | 1.8 (1.8) | 0.33 |

| Able to work/school | 11.9 (1.7) | <0.001 |

|

| ||

| FACT-BMT | ||

|

| ||

| Intercept | 93.2 (3.0) | <0.001 |

|

| ||

| Income category | ||

| <$25,000 | 0 | – |

| $25–74,999 | 4.4 (3.4) | 0.19 |

| ≥$75,000 | 5.3 (3.3) | 0.10 |

|

| ||

| Current work/school status | ||

| Unable to work/school | 0 | – |

| At home | 8.1 (2.6) | 0.002 |

| Able to work/school | 14.3 (2.4) | <0.001 |

|

| ||

| SF-36 Physical Component Score (PCS) | ||

|

| ||

| Intercept | 36.2 (1.4) | <0.001 |

|

| ||

| Income category | ||

| <$25,000 | 0 | – |

| $25–74,999 | 0.5 (1.6) | 0.76 |

| ≥$75,000 | 1.5 (1.5) | 0.34 |

|

| ||

| Current work/school status | ||

| Unable to work/school | 0 | – |

| At home | 1.7 (1.2) | 0.16 |

| Able to work/school | 6.6 (1.1) | <0.001 |

|

| ||

| SF-36 Mental Component Score (MCS) | ||

|

| ||

| Intercept | 41.9 (1.7) | <0.001 |

|

| ||

| Income category | ||

| <$25,000 | 0 | – |

| $25–74,999 | 1.8 (1.8) | 0.32 |

| ≥$75,000 | 0.8 (1.8) | 0.66 |

|

| ||

| Current work/school status | ||

| Unable to work/school | 0 | – |

| At home | 3.6 (1.4) | 0.008 |

| Able to work/school | 4.9 (1.3) | <0.001 |

|

| ||

| Relationship status | ||

| Not partnered | 0 | – |

| Partnered | 2.7 (1.3) | 0.037 |

A parameter estimate of 0 indicates the reference group for each variable; non-reference group parameter estimates indicate the change in patient-reported score compared to the reference group, adjusted for other variables in the model.

The intercept in each model is the expected outcome value when all variables or risk factors in the model have a parameter estimate of 0.

Given the strong association of patient-reported GVHD severity and the ability to work, we sought to further evaluate the potential impact of the other SES variables on outcomes excluding the ability to work. Thus in a separate multivariable model evaluating the same patient-reported outcomes excluding work status, we found that all associations were similar except that without the ability to work, higher income became a significant factor for better QOL.

Risk Factors for Non-relapse and Overall Mortality

In univariable analysis, the following variables were associated with increased risk of NRM: primary diagnosis, older age, inability to work, higher physician rated GVHD severity, worse patient-reported overall symptom score, overlap GVHD, worse Lee score, worse FACT-BMT, worse SF-36 PCS, and worse mAAS. Two variables remained significant in multivariable analysis: type of GVHD and mAAS. Patients with overlap GVHD had higher risk of NRM than those with classic GVHD, while those with higher (better) mAAS had lower risk of NRM. Income was not significantly associated with NRM (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable Risk Factors for Mortality

| Variable | Non relapse mortality | Overall mortality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

|

| ||||||

| Current work status | Not significant | |||||

| -Unable to work | Ref | |||||

| -At home | 0.84 | 0.55–1.29 | 0.43 | |||

| -Able to work | 0.55 | 0.34–0.91 | 0.019 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Type of chronic GVHD | ||||||

| - Classic | Ref | Ref | ||||

| - Overlap | 1.60 | 1.04–2.46 | 0.033 | 1.45 | 1.01–2.07 | 0.045 |

|

| ||||||

| HAP Adjusted Activity Score, BMT modified (mAAS) (5 point increase) | 0.86 | 0.80–0.92 | <0.001 | 0.89 | 0.84–0.94 | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Income category | ||||||

| - <$25,000 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| - $25–74,999 | 1.69 | 0.74–3.88 | 0.21 | 1.09 | 0.61–1.95 | 0.76 |

| - $≥75,000 | 1.88 | 0.84–4.19 | 0.12 | 1.27 | 0.73–2.22 | 0.40 |

More recent year of transplant, primary diagnosis, umbilical cord blood graft source, shorter time between transplant and study enrollment, older age, higher physician rated chronic GVHD severity, overlap GVHD, worse FACT-BMT, worse SF-36 PCS, and worse mAAS were all variables associated with increased risk of overall mortality in univariable analysis. The only sociodemographic variable associated with increased mortality was the inability to work, which remained significant also in multivariable analysis. It is intuitive that work status may be an indicator of overall patient health and well-being accounting for its association with mortality. However, the fact that patients who were able to work had the lowest risk of overall mortality relative to those unable to work, while those who were at home had a similar mortality risk relative to those unable to work may indicate its value as a proxy for SES. Two additional variables remained significant: type of GVHD, and mAAS. Table 3 shows the significant variables for overall mortality.

Income was not significantly associated with overall mortality.

DISCUSSION

In this large, multi-center, observational study of chronic GVHD patients, we report on the association of SES with patient-reported and clinical outcomes for these patients. Our results show a higher symptom burden for patients with chronic GVHD with lower SES as denoted by lower income and inability to return to work. We found the ability to work to be significantly associated with all patient-reported outcomes including the Lee symptom score, activity, QOL, and physical and mental functioning; as well as overall mortality. Interestingly, if the ability to work was removed from multivariable models, income then did become significantly associated with better QOL; which may be a reflection of patient resources and potentially the lack of chronic financial stressors.

Several analyses of SES in HCT have demonstrated that patients with lower SES have worse overall survival and patient-reported outcomes including QOL.10, 11, 13, 14, 28 While lower SES has previously been demonstrated to have a negative impact on HCT outcomes, the potential psychosocial, biologic, and environmental mechanisms are still being investigated. As a surrogate for insurance coverage, health literacy, and access to health-care, it has been speculated that SES plays a major role in healthcare disparities. In patients with chronic GVHD, patients with lower SES may have poorer access to medications and supportive care, leading to worse symptoms. Investigations have increasingly linked low SES with bio-behavioral factors, such as chronic stress, depression, and lower levels of social support to high levels of inflammatory and physiologic stress mechanisms.28, 29 Knight et al recently demonstrated an association of low SES and increased expression of the conserved transcriptional response to adversity (CTRA) gene profile, (a 53-gene panel of pro-inflammatory, response, and antibody synthesis genes), with increased risk of adverse outcomes in allogeneic HCT recipients, suggesting that the association of low SES with poor outcomes may have a biological basis.28

In health policy research studies have predominantly evaluated income, estimated by Zip code of residence and census data, as the primary indicator for SES.1 Occupation or work status is often used as another primary variable for SES. In this study we did not have data on patients’ occupations, or type of work; thus cannot account for the nature of the work (e.g. heavy manual work versus sedentary job) or impact of issues such as physical health problems or physician recommendations on their ability to return to work post-HCT. Thus whether work status in our study is a measure of socioeconomic status or rather a reflection of patient well-being, (or both), is not clear. The finding that patients who were unable to work had a similar mortality risk relative to those who were at home, and a higher mortality relative to those who were able to work, perhaps indicates its potential value as a measure of SES. The association of the ability to work with QOL further highlights the importance of returning to work on mental and physical well-being, emphasizing the need for structured rehabilitation programs for these patients as a way to improve their QOL.

Despite the findings of higher symptom burden with low income, our current study did not establish a correlation between income and mortality in this chronic GVHD cohort. A recent analysis from the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network also reported similar findings of lower income being associated with patient-reported outcomes such as worse physical functioning and more distress, but not with clinical outcomes including survival.30 It is possible that these findings may have resulted from selection bias of groups who inherently have access to health care irrespective of SES, given their ability to come to transplant and to receive post-HCT care as part of a clinical trial.31, 32 In addition, the present cohort may not necessarily be representative of individuals from lower SES categories who may be the most vulnerable. Eight-seven percent of the study population was White, and 73% reported a household income of ≥$50,000, which largely represents the highest quartile of income with the best outcomes in the study by Baker et al.10 In addition, our cohort may represent a more educated population, with 81% of the cohort having completed at least some college or more, significantly higher than the national average of 59%.33

There are several other limitations to our study. Although factors such as primary disease and disease risk were taken into account in analysis, data for this study represents a cross-sectional analysis of patients, and it is possible that factors varying over time may have also played a role in outcomes. Sociodemographic information was collected and its association with PROs was examined only at baseline. We also did not have data for these variables at the time of HCT to compare it with the information at enrollment. We did not assess the relationship between longitudinal change in SES and change in chronic GVHD severity and PROs over time. Further, insurance status is integrally related to SES, but we did not have any information regarding the insurance status of the patients in this cohort.

Notwithstanding the limitations, our study represents the first study specifically evaluating association of SES with outcomes in a large multi-center cohort of chronic GVHD patients with extensive sociodemographic, patient-reported outcome, and other clinical data. A novel feature of this study was use of patient-reported income and other sociodemographic information as indicators of SES, unlike most other studies in the area which use Zip-code and census based data about income and other SES indicators.

In conclusion, we demonstrate an important association between SES and patient-reported outcomes in patients with chronic GVHD. The potential psychosocial, biologic, and environmental factors that mediate this association remain poorly understood and need further research. Within the Chronic GVHD Consortium, a study assessing financial burden concerns is ongoing and may help further describe the specific financial challenges (specifically insurance or employment related) that might affect patient-reported and clinical outcomes. Interventions that promote health and facilitate educational advancement, increase work-related capabilities, and improve social support may help reduce the socioeconomic disparities in patient-reported outcomes in patients with chronic GVHD.

Highlights.

Lower socioeconomic status denoted by lower income was associated with higher symptom burden and poor quality of life in chronic GVHD patients.

There was no association of income, race or education with survival, but inability to work was associated with higher overall mortality in chronic GVHD patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutions of Health, National Cancer Institute (CA118953). The Chronic GVHD Consortium (grant U54 CA163438) is a part of the National Institutes of Health Rare Disease Clinical Research Network, supported through collaboration between the Office of Rare Diseases Research, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Cancer Institute and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no relevant financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Adler NE, Boyce T, Chesney MA, et al. Socioeconomic status and health. The challenge of the gradient. Am Psychol. 1994;49:15–24. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.49.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NCHHSTP Social Determinants of Health. 2014 Available from URL: https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/socialdeterminants/definitions.html. Accessed February 10, 2017.

- 3.Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam AJ, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2468–2481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0707519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marmot MG. Socio-economic factors in cardiovascular disease. J Hypertens Suppl. 1996;14:S201–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cross CK, Harris J, Recht A. Race, socioeconomic status, and breast carcinoma in the U.S: what have we learned from clinical studies. Cancer. 2002;95:1988–1999. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viana MB, Fernandes RA, de Oliveira BM, Murao M, de Andrade Paes C, Duarte AA. Nutritional and socio-economic status in the prognosis of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2001;86:113–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mackillop WJ, Zhang-Salomons J, Groome PA, Paszat L, Holowaty E. Socioeconomic status and cancer survival in Ontario. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1680–1689. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.4.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silla L, Fischer GB, Paz A, et al. Patient socioeconomic status as a prognostic factor for allo-SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;43:571–577. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Majhail NS, Omondi NA, Denzen E, Murphy EA, Rizzo JD. Access to hematopoietic cell transplantation in the United States. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2010;16:1070–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.12.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker KS, Davies SM, Majhail NS, et al. Race and socioeconomic status influence outcomes of unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2009;15:1543–1554. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu S, Rybicki L, Abounader D, et al. Association of socioeconomic status with long-term outcomes in 1-year survivors of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50:1326–1330. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abel GA, Albelda R, Khera N, et al. Financial Hardship and Patient-Reported Outcomes after Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2016;22:1504–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamilton JG, Wu LM, Austin JE, et al. Economic survivorship stress is associated with poor health-related quality of life among distressed survivors of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22:911–921. doi: 10.1002/pon.3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun CL, Francisco L, Baker KS, Weisdorf DJ, Forman SJ, Bhatia S. Adverse psychological outcomes in long-term survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation: a report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study (BMTSS) Blood. 2011;118:4723–4731. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khera N, Zeliadt SB, Lee SJ. Economics of hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2012;120:1545–1551. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-426783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duell T, van Lint MT, Ljungman P, et al. Health and functional status of long-term survivors of bone marrow transplantation. EBMT Working Party on Late Effects and EULEP Study Group on Late Effects. European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:184–192. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-3-199702010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wingard JR, Majhail NS, Brazauskas R, et al. Long-Term Survival and Late Deaths After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.7212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wingard JR, Piantadosi S, Vogelsang GB, et al. Predictors of death from chronic graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1989;74:1428–1435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Socie G, Stone JV, Wingard JR, et al. Long-term survival and late deaths after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Late Effects Working Committee of the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:14–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907013410103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Syrjala KL, Langer SL, Abrams JR, et al. Recovery and long-term function after hematopoietic cell transplantation for leukemia or lymphoma. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291:2335–2343. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.19.2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pidala J, Kim J, Anasetti C, et al. The global severity of chronic graft-versus-host disease, determined by National Institutes of Health consensus criteria, is associated with overall survival and non-relapse mortality. Haematologica. 2011;96:1678–1684. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.049841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vigorito AC, Campregher PV, Storer BE, et al. Evaluation of NIH consensus criteria for classification of late acute and chronic GVHD. Blood. 2009;114:702–708. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-208983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Chronic GC. Rationale and Design of the Chronic GVHD Cohort Study: Improving Outcomes Assessment in Chronic GVHD. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2011;17:1114–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee SJ, Cook EF, Soiffer R, Antin JH. Development and validation of a scale to measure symptoms of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2002;8:444–452. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2002.v8.pm12234170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McQuellon RP, Russell GB, Cella DF, et al. Quality of life measurement in bone marrow transplantation: development of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Bone Marrow Transplant (FACT-BMT) scale. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19:357–368. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247–263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, et al. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2005;11:945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knight JM, Rizzo JD, Logan BR, et al. Low Socioeconomic Status, Adverse Gene Expression Profiles, and Clinical Outcomes in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients. Clinical Cancer Research. 2016;22:69–78. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brummett BH, Babyak MA, Siegler IC, et al. Systolic Blood Pressure, Socioeconomic Status, and Biobehavioral Risk Factors in a Nationally Representative U.S Young Adult Sample. Hypertension. 2011;58:161–166. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.171272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knight JM, Syrjala KL, Majhail NS, et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes and Socioeconomic Status as Predictors of Clinical Outcomes after Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Study from the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network 0902 Trial. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2016;22:2256–2263. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pidala J, Craig BM, Lee SJ, Majhail N, Quinn G, Anasetti C. Practice variation in physician referral for allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:63–67. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sateren WB, Trimble EL, Abrams J, et al. How Sociodemographics, Presence of Oncology Specialists, and Hospital Cancer Programs Affect Accrual to Cancer Treatment Trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:2109–2117. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bauman Ra. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2016/demo/p20-578.html2015. Accessed May 5, 2017.