Abstract

Given its short hyperpolarization time (~10−6 s) and mostly non-perturbative nature, photo-chemically induced dynamic nuclear polarization (photo-CIDNP) is a powerful tool for sensitivity enhancement in nuclear magnetic resonance. In this study, we explore the extent of 1H-detected 13C nuclear hyperpolarization that can be gained via photo-CIDNP in the presence of small-molecule additives containing a heavy atom. The underlying rationale for this methodology is the well-known external-heavy-atom (EHA) effect, which leads to significant enhancements in the intersystem-crossing rate of selected photosensitizer dyes from photoexcited singlet to triplet. We exploited the EHA effect upon addition of moderate amounts of halogen-atom-containing cosolutes. The resulting increase in the transient triplet-state population of the photo-CIDNP sensitizer fluorescein resulted in a significant increase in the nuclear hyperpolarization achievable via photo-CIDNP in liquids. We also explored the internal-heavy-atom (IHA) effect, which is mediated by halogen atoms covalently incorporated into the photosensitizer dye. Widely different outcomes were achieved in the case of EHA and IHA, with EHA being largely preferable in terms of net hyperpolarization.

Keywords: hyperpolarization, photo-CIDNP, heavy atoms, NMR sensitivity, inter-system crossing, external heavy-atom effect

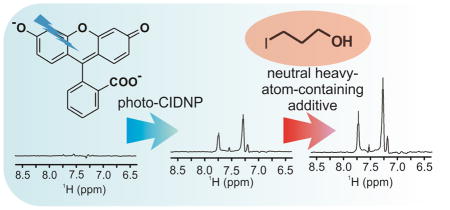

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy is an excellent tool to investigate molecular structure and dynamics at atomic resolution. Yet, NMR suffers from low sensitivity due to the intrinsically small polarization of nuclear spins even at high applied magnetic field. In real-life applications however, high sensitivity is often required, and NMR experiments demanding low sample concentration or kinetic timecourse studies away from equilibrium are often unfeasible.

Photochemically induced dynamic nuclear polarization (photo-CIDNP) requires a conveniently short (~10−6 – 1 s) in situ hyperpolarization time and is often non-perturbative in nature [1–6]. Photo-CIDNP has recently received considerable attention as an effective hyperpolarization tool for aromatic amino acids, polypeptides and proteins in solution. This technique bears great potential for further sensitivity enhancement in NMR, given that the percent polarization that has been achieved via photo-CIDNP to date is, in most cases, far below the theoretically achievable values.

The approaches adopted so far to increase the extent of photo-CIDNP-induced hyperpolarization in liquids include improved 1H pulse-sequences [4, 7], the development of hyperpolarization schemes tailored to nuclei other than 1H in the context of heteronuclear correlation spectroscopy [8, 9, 10, 11], variations in magnetic-field strength [12], addition of oxygen-scavenging agents [13], and the use of a variety of photosensitizer dyes [2], including one that is specifically tailored to low-concentration samples [14].

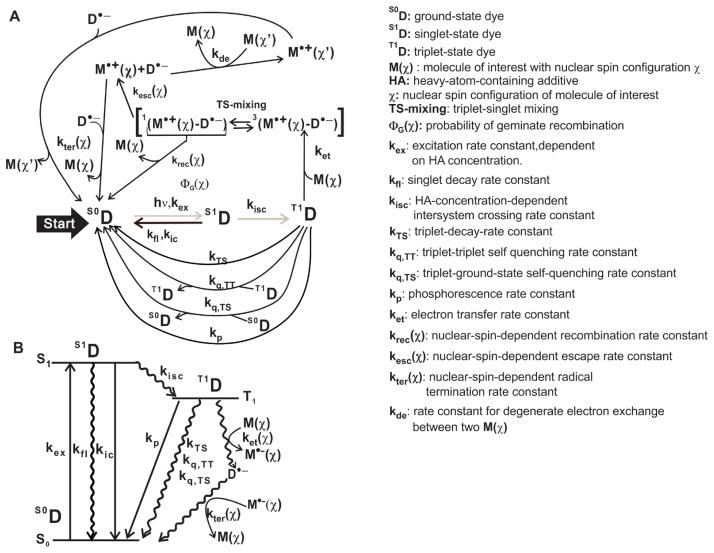

A schematic representation of the main steps involved in photo-CIDNP is illustrated in Figure 1. Under steady-state laser irradiation conditions and when the total probability that a single nucleus in a geminate radical pair generates photo-CIDNP geminate recombination products ΦG is small (i.e., ΦG ≪ 1), the nuclear spin polarization of the kth nucleus of the target molecule of interest M can be expressed as

Figure 1.

A) Schematic illustration of the photo-CIDNP process. B) Energy diagram showing the main transitions and physical events involving the photo-CIDNP dye.

| (1) |

where and are the longitudinal nuclear spin relaxation times of the kth nucleus for the diamagnetic and transient radical M•+, respectively, and is the normalized difference between the probabilities of a kth nucleus in a recombination product to be in an α or β nuclear spin state per geminate recombination event. Similarly, is the normalized difference between the probabilities of a kth nucleus in a recombination product to be in an α or β nuclear spin state per F-pair recombination event [5, 15]. The parameter γ denotes the ratio between geminate and F-pair polarization, assuming instantaneous paramagnetic relaxation (for ) so that the nuclear spin polarization of the radical nuclear spins is zero at all times (i.e., ), ket is the bimolecular electron transfer rate constant, kter is the effective bimolecular radical-termination rate constant and [T1DSS], [MSS] and [M•+,SS] are the steady-state concentrations of triplet excited-state dye D, M and M•+. These concentrations depend on various photophysical properties of the system (e.g., intersystem-crossing rate constant kisc), in addition to those listed above. The parameters , γ, kter and ΦG are related to the magnetic properties of the dye (e.g., g values and hyperfine coupling constants). For instance, in a chemical system composed of freely diffusing molecules in solution at high applied magnetic field, one has , where gdye and gM are the g factors of the dye and the molecule of interest, respectively. Finally, kde is the rate constant for degenerate electron exchange [16, 17].

Equation 1, which is derived in the Supporting Information, is related to previously derived expressions for time-resolved photo-CIDNP [3, 15] and incorporates the role of degenerate electron exchange [18]. Additional processes that depend on the concentration and chemical properties of the molecule of interest, including reductive inter-molecular electron transfer [19] and non-cyclic reactions [15] can be neglected on a 1st-order approximation, but must be taken into account for a more complete treatment.

To optimize the extent of nuclear polarization achievable via photo-CIDNP in liquids, different photosensitizer dyes were evaluated. To date, the main dyes that proved effective in steady-state photo-CIDNP at high field are flavin- [2], xanthene- [14, 20–22] and quinone-based molecules [2]. While flavin mononucleotide (FMN) has been the most widely used dye, fluorescein has led to the highest sensitivity enhancements in dilute liquid samples [14].

Variations in the photo-CIDNP dye structure are well known to often lead to the simultaneous change in several parameters in eq. 1, rendering the tuning and rational control of the desired effects rather difficult. For instance, it was experimentally shown that naphthalene derivatives [23], which are characterized by high intersystem-crossing rates from photoexcited singlet to triplet, also show fast photoexcited triplet decay rates. Indeed, while the former effect favors photo-CIDNP, the latter disfavors it. In addition, it was shown that important interactions (e.g., spin-orbit coupling) responsible for driving photophysical processes are often strongly coupled to variations in magnetic properties [24, 25]. Hence, unfortunately, the tuning of one parameter often affects others too, significantly complicating reliable predictions of the hyperpolarizing effect of different dyes in photo-CIDNP.

In this work, rather than developing new photosensitizer dyes, we selectively tuned the properties of an existing photo-CIDNP dye, fluorescein, in the attempt of modifying the smallest number of parameters in eq. 1. We exploited the fact that heavy atoms are known to cause increases in intersystem crossing rates, an effect that is expected to increase the transient concentration of triplet photoexcited dye at steady state, [T1DSS], hence enhance hyperpolarization (see eq. 1). We altered the characteristics of photo-CIDNP dyes by enabling their collisions with an extrinsic soluble form of a heavy atom (covalently linked to a carrier small molecule), thus exploiting the external heavy-atom (EHA) effect [26, 27]. The best heavy-atom-containing carrier was found to be the neutral and water-soluble 3-iodo-1-propanol (IPO).

We found that the above procedure induces an EHA on the fluorescein dye and substantially increases its photoexcited triplet-state concentration (i.e., [T1DSS]) while retaining many other favorable dye characteristics, including long triplet-state lifetimes and sensitivity-favoring magnetic properties. As a result, significant photo-CIDNP enhancements were observed. As a reference, we also probed the effect of internal heavy atoms (i.e., heavy atoms covalently incorporated into the structure of the molecule undergoing intersystem crossing). Towards this end, we examined the effect of introducing covalent heavy-atom substituents into the structure of the photosensitizer dye. We found that these substituents give rise to the internal heavy-atom (IHA) effect [27], which negatively affects the sensitivity-enhancing properties of the fluorescein photo-CIDNP sensitizer.

2. Results and discussion

Absorptive and emissive photo-CIDNP polarization in the presence of xanthene dyes

We performed photo-CIDNP experiments on the amino acid tryptophan (Trp, 13C-labeled) to assess the degree of nuclear polarization of its carbons in the presence of a number of xanthene derivatives employed as dyes. Each xanthene derivative was employed at low concentration (25 μM). Data were collected with the 1D version of the 13C PRINT pulse sequence [11].

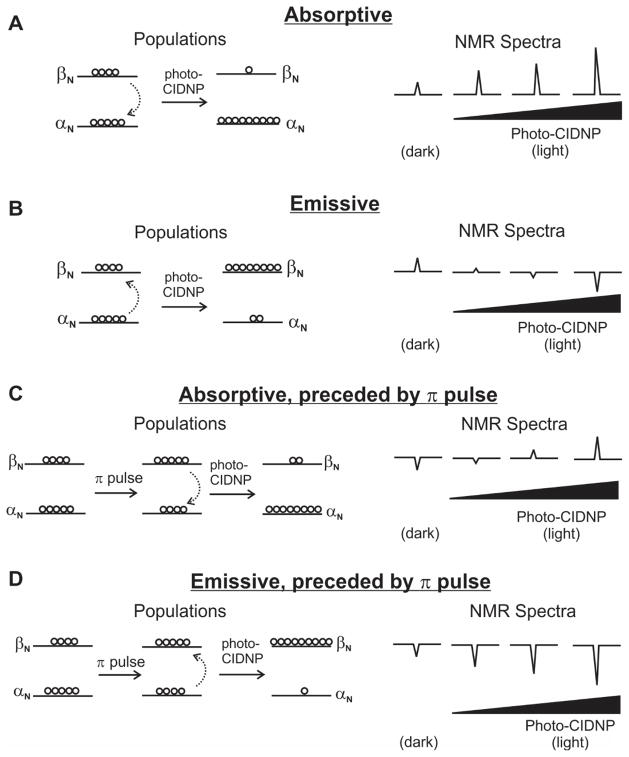

To fully understand the origin of the phase of each resonance in this experiment, it is helpful to start by reviewing some basic concepts. When the population of the lower-energy nuclear spin state (i.e., the α state in the case of 1H or 13C) of a specific nucleus is enhanced as a result of photo-CIDNP, the effect is said to be absorptive (Fig. 2A). Conversely, when the population of the higher-energy nuclear spin state (i.e., the β state for 1H or 13C) is enhanced, photo-CIDNP is regarded to be emissive (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Diagram illustrating the relation between A) absorptive and B) emissive photo-CIDNP and the phase of the corresponding NMR resonances for pulse sequences where photo-CIDNP laser irradiation precedes rf pulse(s). Corresponding diagrams for C) absorptive and D) emissive photo-CIDNP in the case of pulse sequences (e.g., 13C PRINT) where photo-CIDNP laser irradiation is preceded by inversion of the nuclear-spin-state populations by a πx or a πy rf pulse. The black slide bar highlights the dependence of the observed resonance intensities on the extent of photo-CIDNP polarization.

The overall net phase of each detected resonance relative to the corresponding phase in the dark spectrum depends on a variety of parameters and can be assessed from Kaptein’s rule [28].

| (2) |

where signRE denotes the contribution from geminate recombination and escape processes and takes a + or − value for recombination and escape products, respectively. SignTS is either a + or − depending on whether the radical-pair precursor is in a triplet or singlet state, respectively. SignA is the sign of the hyperfine coupling constant of the nucleus of interest, and signΔg is the sign of the g-value difference Δg = gM − gdye, with M being the molecule whose NMR resonance is being detected.

The most desirable type of photo-CIDNP outcome for sensitivity-enhanced NMR is the case of cyclic reactions, where escape and recombination products coincide with the original reactants and no new resonances are observed. Under these conditions, signRE is always + [2, 28]. In the case of noncyclic reactions, new products, hence new resonances, are expected and signRE may be either + or −.

Importantly, the overall value of net-phase parameter is either + or −, corresponding to an overall absorptive or emissive photo-CIDNP, respectively. The corresponding resonance phases displayed in panels A and B of Figure 2. Note that, in the case of emissive photo-CIDNP, the observed phase of the resonance of interest depends on the extent of photo-CIDNP nuclear polarization.

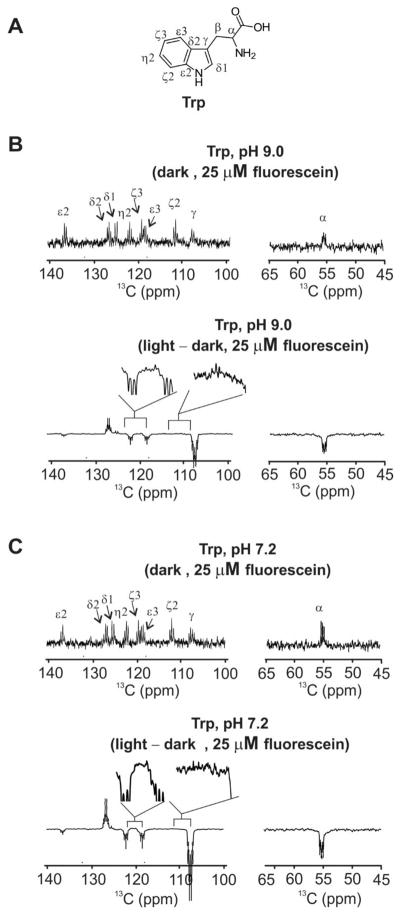

Let us now consider a simple 1D pulse-acquire 13C photo-CIDNP experiment performed on Trp in water at room temperature with fluorescein as a photosensitizer. The dark spectrum displays positive absorptive lineshapes for all resonances (Fig. 3B). The corresponding light spectrum (Fig. 3B) has positive and negative resonances as a result of absorptive and emissive photo-CIDNP for the different resonances. All the phases can be predicted from eq. 2 upon considering the following. First, the dark and light spectrum display the same number of resonances at identical chemical-shift values, supporting a cyclic photo-CIDNP process, and a + value for signRE. Second, the long excited-state lifetimes of the dyes (see sections below) support the fact that the radical-pair intermediate is in a triplet state, hence the signTS parameter takes a + value. Third, given that the known isotropic g factors of the Trp radical cation and the fluorescein radical anion are 2.0027 [29] and 2.0034 [30], respectively, the parameter signΔg is −. The 13C hyperfine coupling constants of the Trp radical cation at pH 9 are known from the literature and are shown in Table 1. Their values are either positive or negative depending on the specific nucleus of interest. The overall net phase of the polarization is predicted to be net phase=(+)(+)(signA)(−), hence positive (corresponding to absorptive photo-CIDNP) for ζ2, ζ3, δ1 and δ2, and negative (corresponding to emissive photo-CIDNP) for α, γ, ε3 and η2. This conclusion is reached after taking into account the 13C hyperfine coupling constant values of Table 1. In summary, the experimental 13C photo-CIDNP spectrum under light conditions in the presence of fluorescein at pH 9 (Fig. 3B) is fully consistent with Kaptein’s rule.

Figure 3.

A) Structure of tryptophan (Trp). B) Dark and difference (i.e., light – dark) 1D 13C photo-CIDNP spectra of aromatic-side-chain carbons and Cα of Trp (1 mM) in the presence of fluorescein (25 μM). Data were collected in an aqueous solution containing 10 mM potassium phosphate and 10% D2O at 25° C and pH 9. C) Same as panel B except that the experiment was carried out at pH 7.0. All experiment included 32 scans. Laser irradiation in the visible region was carried out with an Argon-ion laser (single-line mode, 488 nm, 1.5 W, 0.2 s irradiation time). 13C,15N-labeled Trp was employed. The pulse sequence included: laser irradiation - 13C (π/2)x rf pulse - acquisition with 15N decoupling.

Table 1.

13C hyperfine coupling constants of Trp radical cations at pH 9 computed by density functional theory (DFT) according to Kiryutin et al. [29].

| 13C of Trp | Hyperfine coupling constant (mT)a |

|---|---|

| αb | 0.025 |

| γ | 1.254 |

| δ1 | −0.227 |

| δ2 | −0.891 |

| ε3 | 0.619 |

| ζ2 | −0.182 |

| ζ3 | −0.499 |

| η2 | 0.443 |

1 mT = 10 Gauss

This computationally predicted value is significantly lower than the actual experimental value. The experimentally assessed hyperfine coupling constant relative to the γ carbon value is 0.45, corresponding to an absolute hyperfine coupling constant of 0.564 mT [29].

At the more physiologically relevant pH 7.0 employed in most of this work, the light 13C spectrum of Trp in the presence of fluorescein has the same pattern of phases as the spectrum at pH 9, though the photo-CIDNP enhancements are slightly different (Fig. 3C). Given that the pKa of the carboxylate of the Trp radical cation is ca. 4.3 [18], electrostatic effects within this species are expected to be similar, at pH 7.0 and pH 9.0. Not surprisingly, at pH 7.0 all the relevant Trp 13C photo-CIDNP nuclei display identical polarization patterns as those at pH 9.0 (Fig. 3C), in full agreement with Kaptein’s rule.

13C PRINT photo-CIDNP experiment on Trp

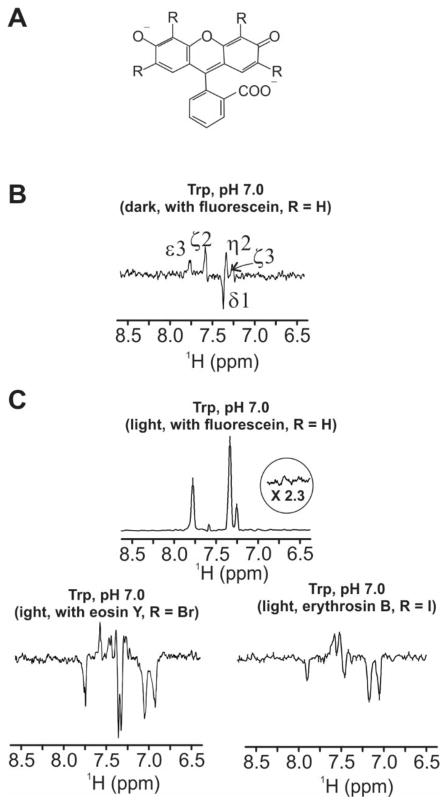

Photo-CIDNP data employing the xanthene dye fluorescein (Fig. 4A, R = H) were collected with the 13C PRINT pulse sequence [11]. This sequence takes advantage of heteronuclear polarization transfer from carbon to proton, and it is generally more sensitive than the simple 13C pulse-acquire experiment. Unlike most steady-state photo-CIDNP pulse sequences [4, 5], 2D 13C PRINT yields data on both 13C and 1H chemical shifts and their covalent connectivities, thus providing important structural information useful for resonance assignments, especially in the context of complex molecules. In addition 13C PRINT is very useful in the biological context, as it displays very good sensitivity for the side chain of aromatic amino acids as well as for their corresponding 1H-Cα pair. Hence 13C PRINT provides information on the Cα nucleus, which is important in biomolecular NMR, given that this chemical shift is diagnostic of peptide and protein secondary structure [31].

Figure 4.

A) Structure of the xanthene sensitizer dyes (in dianionic form) employed in this study: fluorescein (R = H), eosin Y (R = Br) and erythrosin B (R = I). B) 1D dark 13C PRINT photo-CIDNP spectrum of aromatic side-chain 1H resonances of Trp (1 mM) in the presence of fluorescein (25 μM). C) Same as panel B except that data were collected under light conditions and either fluorescein (25 μM), eosin Y (25 μM) or erythrosin B (25 μM) were employed as photosensitizer dye. All samples included catalytic amounts of glucose oxidase and catalase (GO-CAT system: 0.24–0.54 μM GO and 0.15–0.30 μM CAT), and were in 10 mM potassium phosphate, 5% D2O at pH 7.0 and 25° C. 13C,15N-labeled Trp was employed. Data collection was carried out with 16 scans. An Argon-ion laser was employed (multi-line mode, 1.5 W, 1 s laser irradiation).

The 13C PRINT sequence is in constant-time mode. Hence experiments performed under dark (i.e., laser off) conditions lead to resonances of opposite phase depending on whether the corresponding proton-carbon pairs are covalently linked to an even or an odd number of carbons. Data collected under light (i.e., laser on) conditions show resonances whose phase also depends on the absorptive or emissive nature of photo-CIDNP, reviewed in the previous section.

In this work, all 13C PRINT spectra were acquired in 1D mode (i.e., with no 13C chemical shift evolution) with an initial 13C π pulse [11] so that emissive 13C photo-CIDNP polarization always constructively adds to the preexisting 13C magnetization (Fig. 2D). In addition, spectra were phased so that resonances undergoing emissive photo-CIDNP are positive. Note that resonances undergoing absorptive photo-CIDNP may be either negative or positive depending on the extent of polarization enhancement (Fig. 2C).

At pH 7.0, the dark (i.e., laser off) 1D 13C PRINT spectrum of Trp in the presence of the fluorescein xanthene derivative (Fig. 4A, R = H) displays all the expected resonances in the aromatic region (Fig. 4B), corresponding to the 1H-linked 13Cs. One can easily verify that the light spectrum (Fig. 4C) has, with the exception of ζ3, all the expected phases, consistent with a cyclic photo-CIDNP process and with the predictions from Kaptein’s rule (see previous section). Note that the light spectrum displays a positive phase for the δ1 resonance. This phase is easily explained upon considering that (a) the δ1 carbon is only connected to a single carbon hence it has negative phase under dark conditions, and (b) this carbon experiences a significant degree of absorptive photo-CIDNP that enhances polarization beyond the thermal magnetization values. The resonance belonging to the other carbon experiencing absorptive photo-CIDNP, ζ2, is also positive but for different reasons. In this case (a) the dark-spectrum has a positive phase given that this carbon is connected to two other carbons, and (b) the extent of absorptive photo-CIDNP polarization for this nucleus is only moderate given its small hyperfine coupling constant (Table 1), and not sufficient to tilt the phase of the resonance from positive to negative. The ζ3 resonances is expected to display absorptive polarization in 13C photo-CIDNP (e.g., see Fig. 3) but it shows up as emissive in the 13C PRINT experiment(Fig. 4C). The cause of this discrepancy is not clear, and is beyond the scope of this study.

The internal heavy-atom (IHA) effect: photo-CIDNP in the presence of halogen-substituted xanthene photosensitizers

The so called internal-heavy-atom (IHA) effect takes place when large-size monoatomic substituents (e.g., I, Br, Cl) are covalently added to a molecule. This effect has been phenomenologically associated with a decrease in fluorescence quantum yield, an increase in intersystem crossing rate constant, a decrease in phosphorescence lifetime and an increase in phosphorescence quantum yield [27] known to be stronger for heavier atoms [23, 27]. Hence, the IHA effect is expected to be more pronounced for heavier-atom substituents [32].

We investigated the effect of internal heavy atoms on the photo-CIDNP properties of xanthene derivatives related to fluorescein but bearing heavy-atom (halogen) substituents of different mass: eosin Y (Fig. 4A, R = Br) and erythrosin B (Fig. 4A, R = I) in aqueous solution. The photo-CIDNP 1D 13C PRINT light spectra of Trp in the presence of the eosin Y and erythrosin B are widely different from the spectrum obtained in the presence of fluorescein (Fig. 4C). The spectra are complex in that they display unexpected relative phases, new resonances and poor enhancements. The presence of new resonances is undesirable and it strongly suggests a non-cyclic photo-CIDNP process, with new species produced. The above pattern suggests that signRE and(or) signΔg have changed for most of the observed resonances.

While a detailed analysis of the photo-CIDNP spectral features of Trp in the presence of eosin Y and erythrosin B is beyond the scope of this work, a few features stand out.

First, the fact that all dark-spectrum resonances and chemical shifts are preserved and that, in addition, at least four new resonances appear (at ca. 7.62, 7.45 and close to 7 ppm) suggests that a mixture of recombination and escape products is formed. The escape-product population will not be discussed further. Second, the fact that, for instance, the downfield resonances ε3 and ζ2 are absorptive and weakly emissive for both eosin Y and erythrosin B, respectively, supports the fact that signΔg must have changed from − to + in eq. 2. The latter outcome is obtained if gdye were to decrease to a value smaller than 2.0027 as a result of the introduction of heavy atoms within the structural scaffold of xanthene, as in eosin Y and erythrosin B.

A decrease in the g factor of the dye radical is consistent with the experimentally observed low g factor (g = 2.0024) of rose bengal [33], a related xanthene dye that contains four I and four Cl substituents. The expectation of a lower g factor in the presence of covalently linked heavy atoms is also consistent with the results of previous studies [34] with fluorescein, eosin Y and erythrosin B in the presence of substrates with high g values (2.0053 and 2.0052 [35]) than Trp.

Consistent with the above, theoretical predictions by Stone [24] show that g varies as a result of the covalent introduction of heavy-atom substituents. The g factor deviation from the free electron ge (equal to 2.002319) is proportional to the spin-orbit coupling according to

| (3) |

where ξi is the spin-orbit coupling constant of the ith nucleus and ρi is the corresponding electron density. ΔEi is the energy difference between the molecular orbital occupied by the unpaired electron and the next closest-in-energy orbital with different symmetry. Hence, mixing between the singly-occupied HOMO with the nearby lower-in-energy results in a higher g-factor value (than ge) and vice versa. Note that the spin-orbit coupling constant generally increases with the mass of the nucleus. The sign of |g − ge| depends on the relevant orbital energies [24], whose identification is beyond the scope of this work.

Other examples of poor enhancements in the presence of internal heavy atoms are known from the literature for other less biologically relevant substrate-dye systems. Consistent with our results, heavy atom substituents suppress the photo-CIDNP sensitivity enhancement. A representative case is that of benzophenone dyes acting upon phenols and anilines and substrates. For instance, a covalent bromo derivative of benzophenone reduces photo-CIDNP enhancements [36].

Photo-CIDNP is also known to be suppressed when the photo-CIDNP substrates bear internal-heavy-atom substitutions. For instance, the site-specific complete suppression of photo-CIDNP observed upon the selective labeling of specific Tyr as 3-I-Tyr in insulin has been exploited as an aid in the resonance assignment process [37]. Finally, the CIDNP enhancement of photo-excited p-bromo dibenzyl ketone, acting both as a substrate and a dye, is much lower than that of benzyl ketone [36].

In addition to a variation in the g value of the dye, photo-CIDNP suppression upon heavy-atom covalent substitution is also contributed by electron relaxation of the radical pair (from triplet-to-singlet). In the presence of heavy-atom substituents, spin-orbit coupling significantly contributes to electron relaxation of the radical pair [25]. This spin-independent phenomenon leads to an overall suppression of photo-CIDNP. Additional spin-orbit-coupling-induced direct recombination phenomena may also play a role [38].

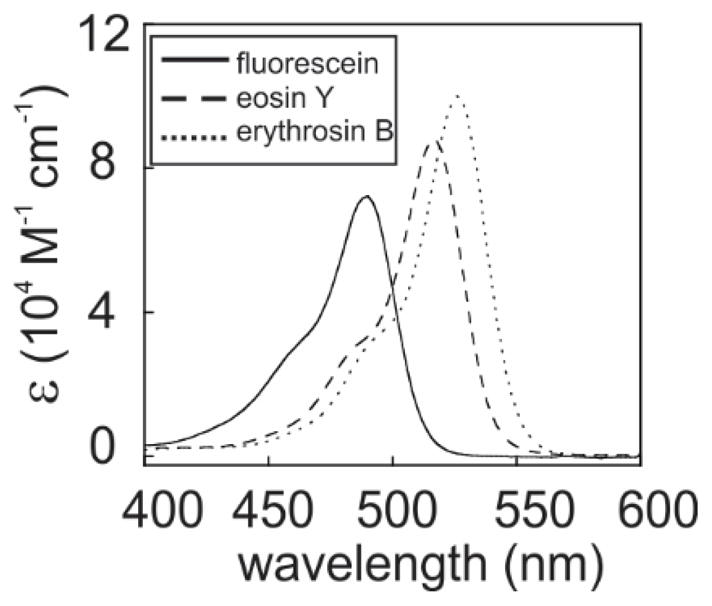

In addition, the introduction of heavy atoms to the aromatic scaffold leads to significant changes in several photo-physical properties of the dyes, as shown in Table 2. Note that, as expected for the IHA effect, the intersystem crossing rate constant increases with the size of the R substituent. While the latter property is anticipated to favor photo-CIDNP of triplet radical pairs, as in this study, we also observed red shifts in the maxima of the electronic absorption spectra, from ca. 488, 515 and 525 nm for fluorescein, eosin Y and erythrosin B, respectively, as shown in Figure 5. The heavy-atom substituents introduce a change in the nature of the electronic environment, leading to an increase in electronic excited-state polarity. This effect likely results into further stabilization of the electronic excited state by the surrounding water molecules. This spectral shift is unfavorable because it decreases the excitation rate constant at the photo-CIDNP laser excitation wavelength of 488 nm, due to a decrease in the absorption coefficient at this wavelength.

Table 2.

Photophysical properties of photo-CIDNP dyes.

| Dye name | Absorption maximum in H2O (nm) | Extinction coefficient at 488 and 515 nm at pH 7.2 c (M−1 cm−1) | Intersystem crossing rate constant (s−1) | Triplet-state lifetime (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescein | 490a | 74,700 at 488 nm 5,700 at 515 nm |

3.7 × 106 f | 20f 280e |

| Eosin Y | 515a,b | 62,700 at 488 nm 16,700 at 515 nm |

8.4 × 108 d 2.8 × 108 e |

0.19d 10e |

| Erythrosin B | 525b | 28,900 at 488 nm 70,000 at 515 nm |

3.44 × 109 e | 1.3e |

Figure 5.

Electronic absorption spectra of fluorescein (10 μM) eosin Y (6 μM) and erythrosin B (6 μM) in 10 mM potassium phosphate at pH 7.0 and 25° C, expressed in terms of wavelength-dependent extinction coefficient ε.

In summary, the IHA effect leads to a variety of changes in photo-physical and magnetic properties, usually resulting in suppression of photo-CIDNP enhancement and significant losses in polarization.

The external heavy-atom (EHA) effect: role of halogen-containing ionic cosolutes

The external-heavy-atom (EHA) effect is a well-known phenomenon discovered by Kasha in 1952 [26]. Unlike the IHA effect, the EHA phenomenon involves no covalent substitutions and arises from the introduction of extrinsic heavy-atom-containing additives to a solution. In this case, intermolecular collisions between the molecule of interest and the heavy-atom-containing cosolute promote the efficiency of intersystem crossing of photoexcited molecules, e.g., photo-CIDNP dyes [39]. A variety of organic molecules are known to experience an increase in intersystem crossing rate constant in the presence of both ionic and neutral heavy atoms in solution at room temperature [39]. The heavier the atoms the larger the observed intersystem crossing rates [40].

Two mechanisms have been proposed to explain the EHA effect. First, charge-transfer from the dye to the external heavy atom may take place within the transient noncovalent complex between the two species, leading to a significant increase in spin-orbit coupling [41]. Second, the exchange mechanism [42] may lead to mixing between the wavefunctions of the dye and the heavy-atom-containing additive by the so-called configuration interaction [27]. As a result, the wavefunction of the dye attains a larger extent of triplet-state character. A more detailed treatment of the EHA mechanisms can be found elsewhere [27].

Both the above mechanisms rely on the transient physical contact, hence on the orbital overlap, of the dye and the heavy-atom-containing additive. Hence, Brownian-motion -mediated molecular collisions in solution are essential for the EHA [43]. An important conclusion is that the EHA effect is directly proportional to the collisional frequency between a heavy atom and a dye, and is therefore proportional to the heavy-atom concentration. Hence, the extent of perturbation induced by the heavy atom can be modulated by its solution concentration. This is a key feature that differentiates the EHA effect from the IHA.

We hypothesize that an increase in intersystem crossing rate constant leads to an increase in the steady-state concentration of photoexcited triplet dye, hence to an increased hyperpolarization, according to eq. 1.

In order to explore whether the EHA effect could be exploited to enhance photo-CIDNP-induced nuclear spin hyperpolarization, representative steady-state photo-CIDNP experiments were performed with Trp (1 mM) as a substrate and fluorescein as a dye (25 μM) in the presence of heavy-atom-containing additives in an aqueous solution. The pH was adjusted to 7.0 and a variety of concentrations of heavy-atom additives were tested, on a 600 MHz NMR spectrometer. The NMR sensitivity, expressed as signal-to-noise ratio per unit time (S/N)t, is directly proportional to the nuclear spin polarization, and was determined according to

| (4) |

where S/N is the signal-to-noise ratio and ttot is the total experiment time.

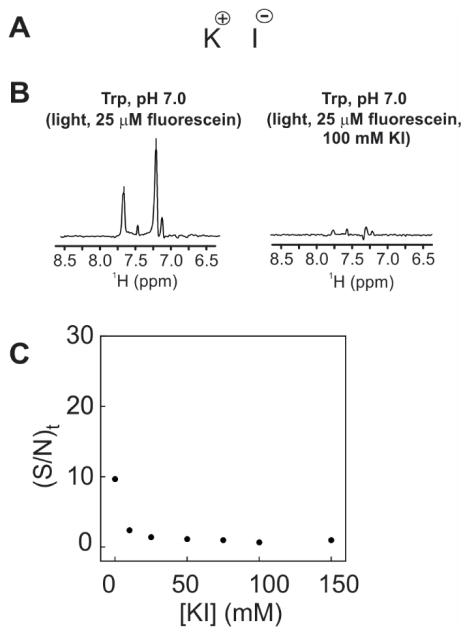

Ionic HA, potassium iodide (KI, Fig. 6A), was added to the solution containing fluorescein and tryptophan. As shown in Figure 6B, while no new resonances were observed in this case, supporting a cyclic photo-CIDNP reaction, a substantial decrease in photo-CIDNP intensities was observed for all aromatic resonances. The KI concentration dependence plot, shown in Figure 6C, illustrates the fact that at 10 mM and higher KI concentration a nearly complete suppression of photo-CIDNP was observed.

Figure 6.

A) Structure of the external heavy-atom additive potassium iodide. B) 1D 13C PRINT photo-CIDNP spectra of aromatic side-chain 1H resonances of Trp (1 mM, light conditions) in the presence of fluorescein (25 μM) at pH 7.0. Data were collected under the same conditions as the spectra in Figure 4 except that one of the samples also contained 100 mM KI. The laser irradiation time was set to 0.1 s. D) plot illustrating the signal-to-noise per unit time (S/N)t of the η2 side-chain 1H-13C Trp resonance (light conditions) as a function of KI concentration. 13C,15N-labeled Trp was used in all experiments.

Clearly, addition of the ionic KI cosolutes disfavors photo-CIDNP. Transient absorption and pH-dependent studies provided invaluable information on the origin on this phenomenon (see following sections).

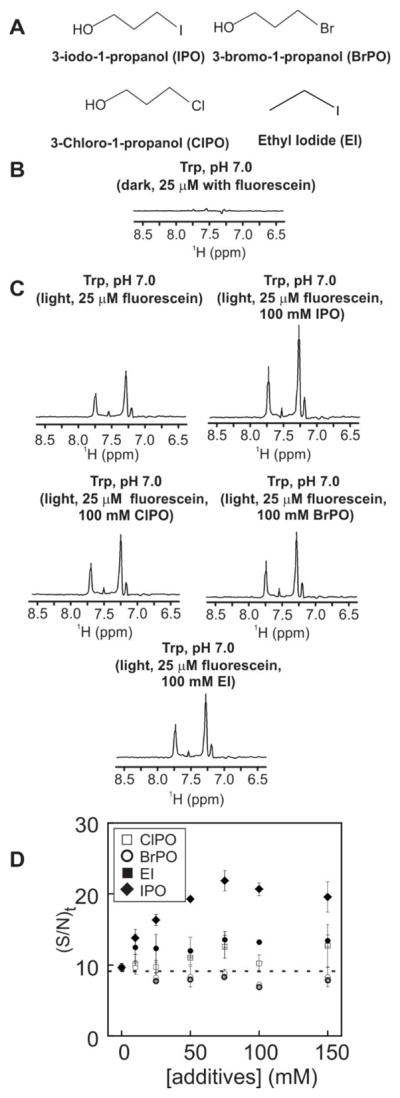

The external heavy-atom (EHA) effect: role of halogen-containing non-ionic cosolutes

Given the inability to obtain significant sensitivity enhancements in the presence of ionic additives, we reasoned that their net charge may be partially responsible for the losses. Hence we resorted to explore the effect of neutral additives. We focused on the small water-soluble alcohols 3-chloro-1-propanol (ClPO), 3-bromo-1-propanol (BrPO), 3-iodo-1-propanol (IPO) and on the small halogenated hydrocarbon ethyl iodide (EI). We performed experiments on 1 mM Trp in the presence of the fluorescein photosensitizer (25 μM).

As shown in Figure 7, no photo-CIDNP suppression was observed in the case of the heavy-atom-containing neutral cosolutes. On the contrary, a progressively larger sensitivity enhancement was observed within the alcohol series ClPO, BrPO and IPO, with the latter displaying the most significant increases. Further, Figure 7D shows that, as the IPO concentration increases up to 100 mM, progressively larger spectral gains are achieved, up to a 2.5-fold sensitivity enhancement relative to the photo-CIDNP intensity in the absence of heavy atoms.

Figure 7.

A) Structure of the neutral heavy-atom-containing additives used in this work. B) 1D 13C PRINT photo-CIDNP spectra of aromatic side-chain 1H resonances of Trp (1 mM, dark conditions) in the presence of fluorescein (25 μM) at pH 7.0. Data were collected under the same conditions as the spectra in Figure 6. C) 13C photo-CIDNP spectra of Trp (1mM, light conditions) collected under the same condition as in panel B, in the absence and presence of the external heavy-atom-containing additives IPO, ClPO, BrPO and EI, defined as in panel A. D) plot illustrating the NMR sensitivity expressed as signal-to-noise per unite time (S/N)t of the η2 Trp resonances under light conditions as a function of heavy-atom-containing additive concentration. Data collection parameters were as in panel C. 13C,15N-labeled Trp was used in all experiments.

The neutral alcohols bearing relatively small halogen substituents (i.e., ClPO and BrPO) led to only slight enhancements while the iodine-containing IPO performed better, consistent with predictions from the EHA effect. The fact that ethyl iodide showed a negligible enhancement suggests that the hydroxyl group may be important. This functional group may increase the binding affinity of the heavy-atom-containing derivatives for fluorescein, though previous studies showed that hydrogen bonding contributes only negligibly to the EHA effect and dye stabilization [44]. The absorptive and emissive nature of the photo-CIDNP effect of individual resonances did not vary, suggesting that addition of IPO does not significantly perturb the magnetic properties of fluorescein, unlike internal heavy atoms.

This result is somewhat surprising because it is known that the EHA effect influences both photophysical and magnetic characteristics of the colliding molecule (in this case the photo-CIDNP dye), including magnetic properties such as the g tensor of the dye. For instance, ESR studies of the fluorescein radical anion dissolved in heavy-atom-containing media like Cs+ showed ESR resonance line-broadening in viscous solution [45]. In addition, investigations on magnetic-field effects (MFE) [46, 47] involving quantification of the changes in radical concentration in the absence and presence of magnetic fields showed a reduction in the MFE experienced by p-cresol and fluorescein in the presence of external heavy atoms in fairly viscous solution of >3.5 cp/K, corresponding to, for instance, >1,032 cp at 295 K. Negligible effects were observed media below 1cp/K. The above studies suggest that addition of external heavy atoms tends to affect g tensors and hyperfine couplings.

The apparent inconsistency between the latter findings and our results is rationalized by considering the viscosity dependence the EHA effect. this phenomenon illustrates the importance of the rotational frequency of the photo-excited dye radical.

It is known that the EHA effect is significant only when the collision frequency of the heavy-atom-containing molecule is greater than the rotational frequency of the dye radical [45, 47, 48].

The estimated rotation frequency of fluorescein in water (0.93 cp [49]) at room temperature is around 1010 s−1and the heavy-atom collision frequency is of the order of 109 s−1, at the concentration employed in this study. Hence the g anisotropy induced by the heavy atom is likely eliminated by the rapid rotational motion of fluorescein, consistent with the apparent lack of magnetic effects in the presence of IPO observed in our experiments.

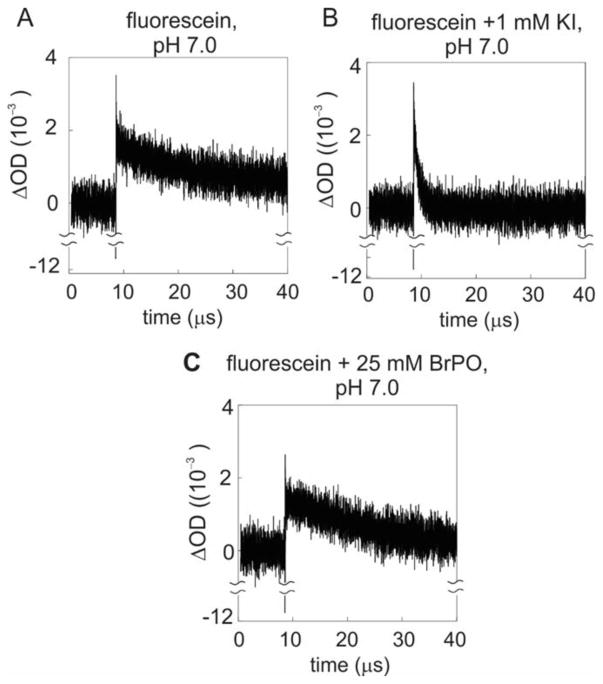

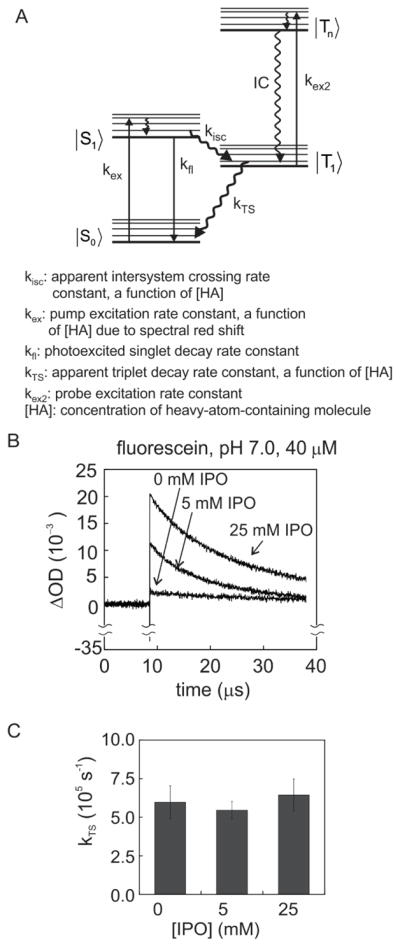

Triplet-triplet transient absorption experiments

In order to investigate the effect of heavy atoms on the triplet-state lifetime of photo-CIDNP dyes in solution, transient absorption experiments were carried out on fluorescein under conditions close to those of the photo-CIDNP NMR data collection. The measurements were carried out as a pump-probe experiment, with the fluorescein sample photo-excited via a high-energy ns pulsed laser (pump light source) at 488 nm. Given the low repetition rate of the laser (ca 20 Hz), the decay time course of the fluorescein triplet state, generated via intersystem crossing, could be followed. Triplet-state populations were monitored via a flash lamp (probe light source) by assessing triplet-triplet electronic absorption from the |T1> to a |Tn> photoexcited states of the dye. The time dependence of the triplet-state population of the dye was followed at 650 nm [50] after each pump laser pulse. A schematic illustration of the energy manifold of the dye in the context of the pump-probe experiment is shown in Figure 8A.

Figure 8.

A) Energy diagram illustrating the electronic transitions involved in the transient absorption experiment. B) Decay timecourse of T1 triplet-state photosensitizer dyes (pump laser excitation: 488 nm, probe lamp excitation: 650 nm, 100 scans) in the absence and presence of different concentration of IPO. The experiment was performed in the presence of catalytic amounts of the GO and CAT enzymes, 10 mM potassium phosphate, 10% D2O, at pH 7.0 and 25° C. C) Block diagram showing the observed triplet-state decay rate constant (kTS) of fluorescein as a function of IPO concentration (see also Table 3).

A fluorescein concentration of 40 μM was used to enable detection of the weak triplet-triplet absorption. The oxygen-scavenging enzymes glucose oxidase (GO) and catalase (CAT) were added in catalytic amounts ([GO]=0.24–0.54 μM, [CAT]=0.15–0.30 μM) to reduce the concentration of molecular oxygen, as in the NMR experiments.

As shown in Figure 8B, the output transient-absorption data are plotted as difference in optical density ΔOD650 = (OD650,ap − OD650, bp). The subscripts denote the sample optical density before (OD650, bp) and after (OD650, ap) the ns laser pulse. The negative spike (lasting a few ns) shortly after the pump-laser pulse is not surprising and it is due to the weak fluorescence emission of the dye at 650 nm, which is detected as an apparent net decrease in light absorption at 650 nm, shortly after the 488 nm pump laser pulse excitation.

The data in Figure 8B reveal that the presence of IPO in solution leads to a substantial increase in triplet-triplet absorption, showing that introduction of the neutral heavy-atom-containing additive IPO leads to a transient increase in triplet-state photoexcited dye concentration. We ascribe this increase to a higher intersystem crossing efficiency. The apparent intersystem crossing rate constant kisc was determined from the initial experimental ΔOD650 values (after fluorescence recovery) at different IPO concentrations (see Supporting Information). From this value, we were able to deuce the kinetic contribution due to the addition of IPO, kq,isc = 6.15 × 109 M−1 s−1, as detailed in the Supporting Information.

The fluorescein triplet decay curves of Figure 8B were fit to single exponentials, leading to observed triplet decay rate constant ( ) values of 55,000 ± 5600 s−1 and 64,000 ± 10.000 s−1 in the presence of 5 and 25 mM IPO, respectively (Table 3). Hence the neutral IPO additive has no influence on the apparent fluorescein lifetime within experimental error.

Table 3.

Observed triplet-state decay rate constant (kts,obs) of the fluorescein (40 μM) photo-CIDNP dye in the absence and presence of heavy-atom-containing additives assessed by transient absorption spectroscopy.

| Heavy-atom-containing additive | kts,obs a (s−1) | R2 a |

|---|---|---|

| – | 51,000 ± 1100 | 0.49 ± 0.03 |

| IPO (1 mM) | 60,000 ± 9400 | 0.75 ± 0.14 |

| IPO (5 mM) | 55,000 ± 5600 | 0.92 ± 0.03 |

| IPO (25 mM) | 64,000 ± 10,000 | 0.99 ± 0.01 |

| KI (5 mM) | 290,000 ± 70,000 | 0.72 ± 0.10 |

| BrPO (5 mM) | 45,000 ± 6900 | 0.52 ± 0.04 |

Average values of 2–5 independent experiments ± standard error.

Overall, the transient absorption data demonstrate that IPO modifies the photophysical properties of fluorescein by increasing its overall apparent intersystem crossing rate kisc with no perturbation in the apparent triplet-state decay rate.

Consistent with our results, the intersystem crossing rate constant (from singlet to triplet photo-excited state) of the non-photo-CIDNP-active rhodamine 6G is also significantly enhanced upon addition of the neutral heavy-atom-containing additive iodobenzene with no variations in triplet decay lifetime [39]. Given that the outcome of our experiments leads to a net increase in steady-state triplet dye population in the context of photo-CIDNP (see eq. 1), we conclude that the increased rate of intersystem crossing from singlet (i.e., S1) to triplet is likely responsible for the photo-CIDNP enhancement observed in the presence of IPO.

The transient triplet decay kinetics of another non-ionic heavy-atom-containing additive studied in this work, BrPO, shows no apparent changes in either triplet intensities or decay rates (Fig. 9 and Table 3), consistent with the weak photo-CIDNP enhancement exhibited by these additives. Similar results were obtained for ClPO (data not shown). Small increases in triplet intensity and decay rates were observed for EI.

Figure 9.

Decay timecourse of T1 triplet-state of fluorescein in the absence (panel A) and presence (panels B and C) of neutral heavy-atom-containing additives. Experimental conditions are as in Figure 8.

In contrast, the KI ionic additive displays an increase in initial |T1> population of the dye followed by a rapid decay (Fig. 8B). This result suggest that KI enhances both intersystem crossing and triplet-to-singlet. (TS path in Fig. 8A) interconversion of the photo-CIDNP dye, explaining the origin of the observed severe quenching of photo-CIDNP.

The origin of the above different effects observed for the heavy-atom-containing additives studied in this work is likely complex and beyond the scope of this work. Both the properties of photoexcited singlet and triplet states of the dyes, as well as properties of the heavy-atom-containing additives are likely contributing to the observed intersystem crossing and triplet decay rates (see chapters 1 and 8 of [27]).

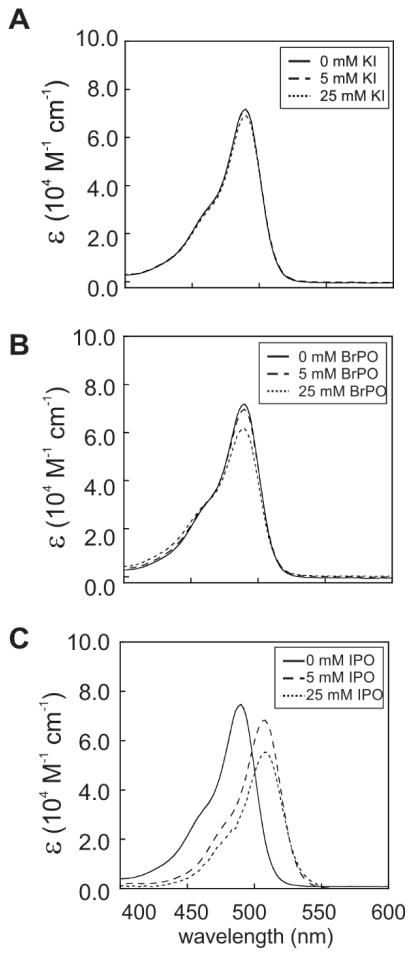

Electronic absorption characteristics of fluorescein in the presence of external heavy atoms

To further investigate the origin of the effect of external-heavy-atom-containing additives on photo-CIDNP, we collected electronic absorption spectra of fluorescein in the absence and presence of different concentrations of KI, BrPO and IPO (Fig. 10). The absorption spectrum of fluorescein did not significantly change in the presence of KI and BrPO, suggesting no or little influence on the |S0> state of the dye. On the other hand, a red shift was observed upon addition of IPO. The maximum of the major absorption band shifted from 490 to 512 nm, No clear isosbestic points were observed, supporting the conclusion that IPO and fluorescein do not form a well-defined two-state binding complex over the concentration range tested in this work.

Figure 10.

Electronic absorption spectra of fluorescein in 10 mM potassium phosphate, 10 % D2O at pH 7.2 and 25° C in the absence and presence of A) KI (10 μM FL) mM), B) BrPO (10 μM FL) and C) IPO (15 μM FL), expressed in terms of wavelength-dependent extinction coefficient ε.

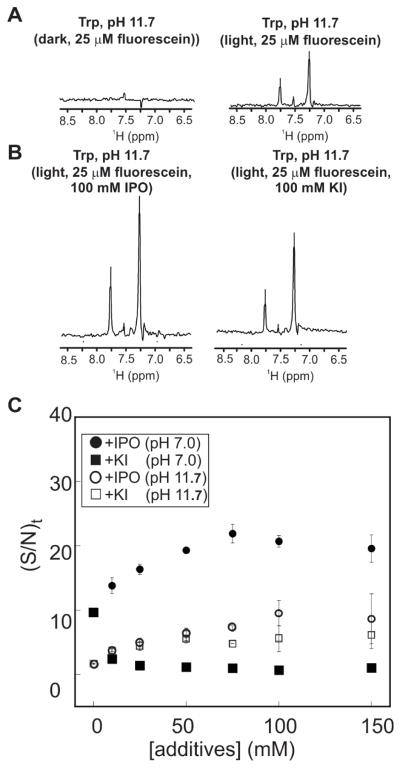

pH dependence of the EHA effect of IPO and KI

All the experiments discussed in the previous sections were conducted at ca. pH 7.0 ± 0.1. Under these conditions, Trp is in an overall neutral form and fluorescein is > 80 % dianionic. In order to test whether the observed IPO-induced enhancement and KI-induced quenching of photo-CIDNP may vary as a function of the protonation state of Trp, we also performed photo-CIDNP NMR experiments at pH 11.7, i.e., when Trp is in its deprotonated form (net charge −1) and fluorescein is still in its dianionic form. Not surprisingly, the 13C PRINT NMR spectrum of Trp under dark conditions differs at pH 7.1 and pH 11.7 (Figs. 7B and 11A).

Figure 11.

pH dependence of photo-CIDNP in the presence of external-heavy-atom-containing additives. 1D 13C photo-CIDNP spectra of aromatic-side-chain carbons of Trp (1 mM) in the presence of fluorescein (25 μM), under dark and light conditions. Data were collected in an aqueous solution containing 10 mM sodium phosphate and 5% D2O at 25° C and pH 11.7. C) Same as panel B except that the experiment was carried out in the presence of 100 mM IPO. All data were collected under the same condition as the spectra in Figure 6.

Overall, the transient radical pairs generated during photo-CIDNP have different protonation states. The pairs generated at neutral pH comprise cationic Trp (+1) and trianionic fluorescein (−3) radicals, while the pairs generated at pH 11.7 include neutral Trp (0) and tri-anionic fluorescein (−3) radicals. Hence, the spin and translational dynamics of the radical pairs are expected to be different at the different pH values.

Consistent with the above observations, photo-CIDNP in the presence of variable concentrations of KI or IPO (Fig. 11) shows different enhancements than at neutral pH. On the other hand, the heavy-atom concentration dependence of the sensitivity (expressed as (S/N)t) follows a similar pattern at neutral and at higher pH. The plot of Figure 11C highlights the fact that NMR sensitivity is significantly enhanced in the presence of external heavy-atom-containing derivatives, which is one of the major finding of this work. In addition, the neutral IPO is clearly better than the ionic KI at both pH values.

Interestingly, KI suppresses NMR sensitivity at neutral pH but it slightly enhances it at higher pH values. The origin of this effect is likely related to the ionic state of the radical pair. However, the details are likely complex and beyond the scope of this work.

Trp concentration dependence

The photo-CIDNP experiments described in the previous sections were carried out at 1 mM Trp concentration (1 mM). We investigated the effect of the most promising additive, IPO (50 mM), at different concentrations. While complete quenching of photo-CIDNP was observed at 20 μM Trp and small enhancements were detected at 200 μM Trp, the enhancements obtained at 5 mM Trp were higher than at 1 mM Trp concentration (data not shown). The origin of this concentration dependence is not clear at present and is beyond the scope of this work.

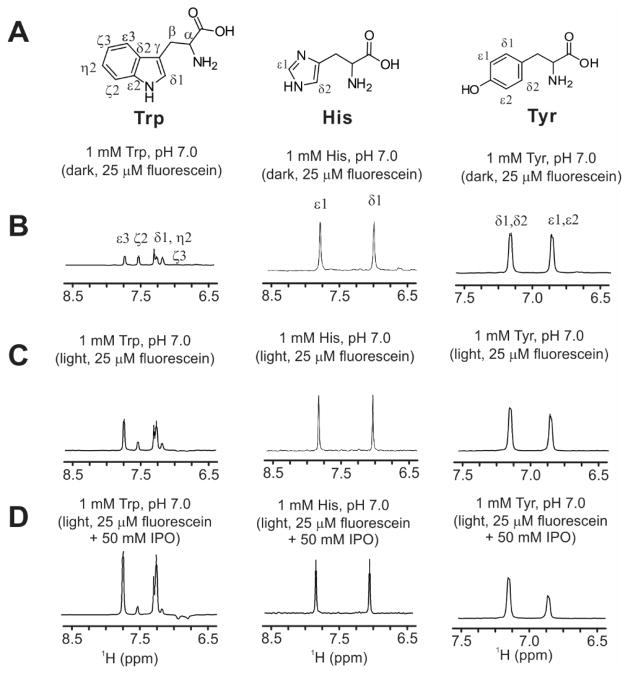

EHA effect on different amino acids

In order to explore the EHA effect on amino acids different from Trp, we performed some representative 1D 1H photo-CIDNP on tyrosine (Tyr) and histidine (His) in the presence of fluorescein (25 μM) and in the absence and presence of IPO (50 mM). In the absence of IPO, we observed a slight enhancement in the photo-CIDNP intensity of the Tyr δ1, δ2 (absorptive) and ε1, ε2 (emissive) resonances (Fig. 12). No enhancement was observed for any of the His resonances at 600 MHz, consistent with previous investigations based on 13C photo-CIDNP [14]. In the presence of IPO, additional enhancements were observed on Tyr, including very slight absorptive enhancements on the δ1 and δ2 resonances, and more sizable emissive enhancements on the ε1 and ε2 protons. On the other hand, not surprisingly, no effects were observed for His (Fig. 12).

Figure 12.

1D 1H-photo-CIDNP spectra of aromatic side-chain 1H resonances of Trp, Tyr, and His (1mM, dark and light conditions) in the presence of FL (25 μM) at pH 7.0. All sample included catalytic amounts of glucose oxidase and catalase, and were in sodium phosphate, 5% D2O. The samples were irradiated with an Argon-ion laser (multi-line mode, 1.5 W, 0.1 s irradiation time).

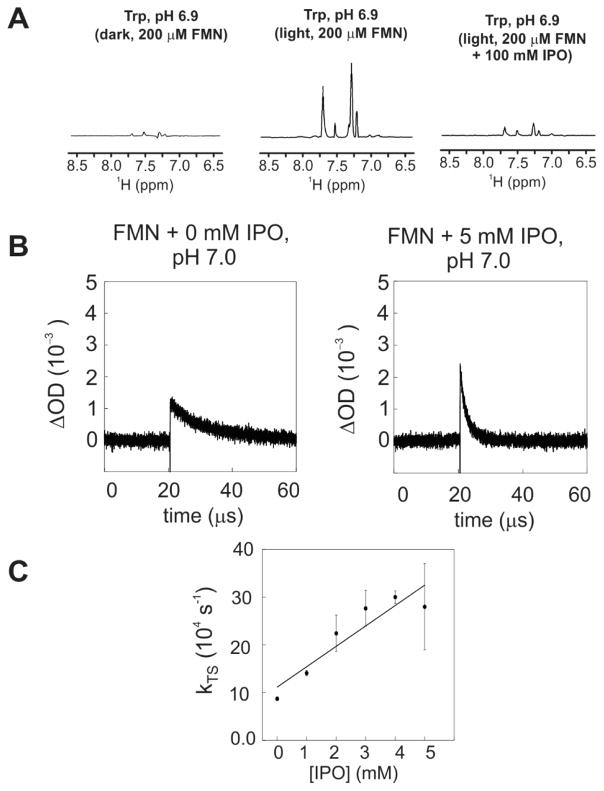

EHA effect on different dyes

In addition to the photo-sensitizer dye fluorescein, we examined the applicability of the EHA effect to flavin mononucleotide (FMN), which is often used in steady-state photo-CIDNP. Photo-CIDNP experiments were performed on Trp in the absence and presence of 100 mM IPO (Fig. 13A). Surprisingly, a ca. more than five-fold decrease in photo-CIDNP intensity was observed in the presence of IPO. To elucidate the origin of this effect, transient absorption experiments were performed on the FMN free dye (Fig. 13B). We observed a slight increase in the initial triplet-triplet absorption intensity, supporting the presence of an increased intersystem crossing rate. Concurrently, a substantial increase in the effective triplet-decay rate constant was also observed, and the IPO-mediated contribution to the triplet-state decay rate constant was found to be kTS,q = 4.3 × 107 M−1 s−1, with kTS,q defined as where kTS(0) is the observed triplet decay rate constant in the absence of IPO, as shown in Figure 13C. From the above observations, we conclude that the observed decrease in photo-CIDNP intensity in the presence of IPO is due to an increase in intersystem crossing rate and to a concurrent even larger increase in triplet-state decay rate constant.

Figure 13.

A) 1D 13C PRINT photo-CIDNP spectra of aromatic side-chain 1H resonances of Trp (1mM) in the absence and presence of FMN (200 μM) at pH 6.9. All samples included catalytic amounts of glucose oxidase and catalase, and were in potassium phosphate (10 mM) and 10% D2O.Data were collected under the same condition as in Figure 6.. B) Transient absorption spectrum of FMN (40 μM) in the absence and presence of IPO. C) Plot illustrating the observed triplet-decay rate constants as a function of IPO concentration. Linear fitting yielded a contribution to the triplet decay rate constant induced by IPO, kTS,q, of 4.3 × 107 M−1 s−1.

Kinetic simulations and general considerations

Transient triplet-triplet absorption and steady-state electronic absorption experiments showed that some of the photophysical properties (i.e., kex and kisc) of the photo-CIDNP dye fluorescein are perturbed by addition of the heavy-atom-containing additives IPO, BrPO, ClPO and KI (Figs. 8–10). On the other hand, photo-CIDNP experiments (Fig. 7) did not provide direct evidence for perturbations in the magnetic properties of the radical pairs, e.g., g factor or hyperfine coupling constants, in the presence of the above additives. Hence, we attempted to provide additional insights into the consequences of adding external heavy atoms on photo-CIDNP by a few theoretical considerations and some simple computer simulations.

First, we note that when kde[Trp] ≫ 1/T1Trp•+ and kter[D•−,SS] at any IPO concentration, the terms in the denominator of eq. 1 become

| (5) |

The above approximation is reasonable at the Trp concentration employed in this study. That is, kde = 9 × 108 M−1 s−1 for free Trp[18], yielding kde[Trp] = 9 × 105 s−1. The upper limit of kter is of the order of 109–1010 M−1 s−1 (i.e., diffusion-limited). At the laser power employed in this study (i.e., 1.5 W), the radical dye concentration is expected to be very small. Kinetic simulations (see details in the SI) yield [D•−,SS]≪2.5 μM at all IPO concentration considered here. In other words, kter ≪ 103–104 M−1 s−1. T1Trp•+ is most likely of the order of 104–105 s−1. Finally, kde[Trp] = 9 × 105 s−1 ≫ 104–105 s−1 > kter[D•−,SS] and T1Trp•+.

In addition, if we assume that the steady-state ground-state Trp concentration [TrpSS] is approximately the same as the initial concentration [Trp (t = 0)]. Then [TrpSS] ~ [Trp]o when [Trp(t = 0)]≫[S0D(t = 0)], where [S0D(t = 0)] is the initial concentration of the dye. In other words, [TrpSS]=[Trp(t=0)] − [Trp•+,SS]=[Trp(t=0)] − [D•−,SS] > [Trp(t=0)] − [S0D(t=0)] ≈ [Trp(t=0)]. As a result, eq. 1 becomes

| (6) |

Assuming that magnetic properties such as T1Trp•+, , ΦG and γ are unaltered by externally added heavy-atom-containing additives, eq. 6 can be further simplified upon considering the ratio of the observed polarization in the absence and presence of externally added heavy atoms (e.g., IPO) as follows

| (7) |

Conveniently, eq. 7 only depends on the triplet-state concentration which can, to a reasonably good approximation, be computed independently of the magnetic-field-dependent parameters. As shown in the supporting Information, the steady-state triplet-state concentration can be approximated as

| (8) |

where

| (9) |

kisc(0) is the intersystem crossing rate constant in the absence of externally added heavy atoms, kisc,q is the heavy-atom-mediated intersystem crossing rate constant, kfl is the singlet state deactivation rate constant, and kex is a heavy-atom-dependent excitation rate constant (Table S1).

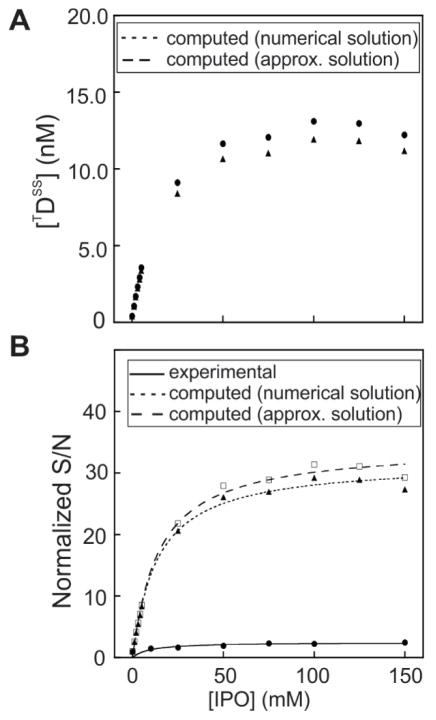

As input to our our simulations, we adopted multi-line laser-excitation mode and IPO as an additive (to fluorescein), consistent with the experimental data in Figure 11C. Importantly, the simulations take into account the experimentally detected electronic absorption spectral shifts induced by addition of IPO (Fig. 10).

A comparison between the simulated concentration derived from the Supporting-Information eq. S11–15 and from eq. 8 above is shown in Figure 12A. Eq. 8 shows that the triplet-state concentration is linearly proportional to kex. For kfl > kisc, the triplet-state concentration is also proportional to kisc but the asymptotic behavior at very large values of inter-system-crossing rate constants (i.e., kisc → ∞) the triplet-state concentration is independent of kisc.

The approximate ratio of nuclear spin polarizations can be obtained by substituting eq. 9 into eq. 7, yielding

| (10) |

The experimental and theoretically predicted ratio of nuclear spin polarizations in the absence and presence of external heavy atoms is plotted in Figure 12.

Similarly to the trends predicted from eq. 6, the nuclear spin polarization ratio is expected to be independent of kisc as kisc → ∞. In other words, a saturation behavior is predicted at high IPO concentrations ([IPO] → ∞).

The experimentally and theoretically predicted ratios are in good qualitative agreement in that increases linearly as a function of [IPO] at low [IPO] but levels off at higher IPO concentrations. However, the agreement is not quantitative, This result suggests that the presence of externally added heavy atoms leads to complex variations in the system, including changes in kisc and kex and variations in additional photo-CIDNP-related parameters in eq.1, e.g., , ΦG and γ. In addition, variations in electron spin relaxation caused by changes in g-tensor anisotropy [25] are also possible. Finally, the presence of cosolutes including external heavy-atom substituents may trigger variations in additional pathways involving the photoexcited triplet-state dye [39].

This study shows that the overall features of photo-CIDNP in the presence of neutral external heavy-atom substituents are similar to those of Figure 1. On the other hand, the pH-dependent effects of Fig. 11 and the simulation data of Figure 12 highlight the complexities of the external-heavy atom effect in relation to photo-CIDNP. Hence, additional future studies are necessary to address the yet unresolved mechanistic nuances. Finally, we found that non-neutral external-heavy-atom-containing additives (e.g., KI) as well as internal heavy-atom-containing dyes are not suitable sensitivity-enhancement agents.

Effect of single-line and multi-line laser excitation on photo-CIDNP enhancement

Fluorescein or FMN dye excitation with Ar ion lasers can be performed either in single-line or multi-line mode. The former setup uses a monochromatic beam at 488 nm while the latter employs a beam encompassing a few wavelengths, including two main lines at 488 and 514 nm. As illustrated in Supporting Figure S3 (see also supporting Table S2), the total excitation rate constants of fluorescein in the presence of variable concentrations of IPO (kex,[IPO]) decrease relative to the corresponding values in the absence of IPO (kex,[IPO]=0) in both multi-line and single-line mode, at IPO concentrations higher than 25 mM. Excitation rate constants, reflecting the efficiency of electronic absorption, were derived from electronic absorption spectral data and appropriate equation, as detailed in the Supporting Information.

As a result, for the argon-ion laser used in this study. According to Eqn. 10, a decrease in kex is predicted to result in a decreased photo-CIDNP enhancement. Due to the red shift of the electronic absorption band of fluorescein in the presence of IPO (Fig. 10C and Supporting Fig. S2) and considering the strong Ar-ion laser emission at 514 nm present in multi-line but not in single-line mode, photo-CIDNP enhancements upon addition of IPO are expected to decrease less in multi-line than the single-line mode (Supporting Fig. S3).

Indeed, photo-CIDNP experiments on 1 mM Trp and 25 μM FL in multi-line (total power = 1.5 W) and single-line mode (488 nm, total power = 1.5 W) performed in the absence and presence of 100 mM IPO (data not shown) showed a larger HEA-induced photo-CIDNP enhancement (by ca. 2.5-fold) in multi-line relative to single-line mode, as expected.

In summary, for sensitivity-enhancement purposes, it is best to perform photo-CIDNP experiments employing fluorescein as a dye and IPO as an additive in multi-line mode.

3. Conclusions

In summary, we showed that IPO is a novel NMR-sensitivity-enhancement agent that acts primarily in the context of photo-CIDNP by increasing the intersystem-crossing rate constant of photosensitizer dyes. Addition of IPO to liquid-state NMR samples at low mM concentration leads to a significant enhancement in the photo-CIDNP-mediated nuclear polarization of the model compound Trp. While the sensitivity-enhancing properties of the heavy-atom-containing neutral additive IPO has only been shown here for Trp, it is likely that this effect also applies to a variety of other NMR substrates of interest containing one or more aromatic rings.

4. Experimental methods

Materials

13C-15N-labeled Trp was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (574597). The photo-CIDNP sensitizers fluorescein (FL, 46955), eosin Y (230251) and erythrosin B (200964) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The heavy-atom-containing additives potassium iodide (60399), 3-iodo-1-propanol (451061), 3-bromo-1-propanol (167188), 3-chloro-1-propanol (292087) and ethyl iodide (17780) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Oxygen-scavenging enzymes

The enzymes glucose oxidase (GO, from Aspergillus niger, catalog number G7141, Enzyme Commission classification code: EC 1.1.3.4) and catalase (CAT, from bovine liver, catalog number C40, EC 1.11.1.6) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). All enzymes, provided in freeze-dried form, were separately dissolved in 30 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0) or sodium phosphate (pH 7.0). Separate single-use GO and CAT stock solutions (ca. 5.5–6.2 and 4.2–5.2 μM, respectively) were prepared and stored at −80 °C after flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen.

NMR sample preparation

All NMR samples contained 5 % D2O and 10 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0 ± 0.1) unless otherwise stated. The photo-CIDNP experiments in the presence of the GO and CAT enzymes included 5 mM D-glucose (158968, Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.24–54 μM and 0.15–0.30 μM of GO and CAT, respectively. All the samples used for photo-CIDNP experiments were incubated in the NMR spectrometer for at least 15 min to enable the oxygen concentration to reach steady state values in the absence or presence of GO and CAT.

Photo-CIDNP NMR experiments

All photo-CIDNP NMR experiments were carried out with a continuous-wave argon ion laser (Stabilite 2017, Spectra-Physics-Newport Corporation, Irvine, CA) in multi-line mode (main lines at 488 and 514 nm) or with an argon ion laser (INNOVA SABRE DBW 24/7 Coherent Inc., Santa Clara, CA) in single-line mode. The laser light was focused into an optical fiber (FDP600660710, Molex, Lisie, IL) using a convex lens (LB4330, Thorlabs, Newton, NJ) and a fiber-coupler (F-91-C1-T, Newport Corporation). The optical fiber was guided into a glass NMR-tube coaxial insert (WGS-5BL, Wilmad-Labglass, Buena, NJ), which was then inserted into the NMR tube and adjusted to be 5mm above the receiver coil region. The nominal laser power at the optical fiber tip to be inserted in the NMR tube was assessed with a power meter prior to the NMR experiments. A 1D version of the 1H-detected 13C PRINT pulse sequence [11] with 13C chemical-shift evolution time set to zero was employed. The 13C PRINT pulse sequence is in constant-time mode, and the total evolution time in the indirect dimension set to 13 ms. The spectral width was set to 9,000 Hz with 2,700 complex points. All photo-CIDNP data were collected at 25 °C on a Varian INOVA 600 MHz (14.1 Tesla) NMR spectrometer equipped with a triple-resonance 1H{13C,15N} triple-axis gradient room-temperature (i.e., not cryogenic) probe. Unless otherwise stated, laser irradiation time was set to 0.1 s. This value was chosen after performing sample experiments testing the S/N dependence of laser irradiation time [14]. The relaxation delay was set to 10 s for all experiments. All 1D time-domain data were apodized with a 5 Hz exponential line-broadening function and baseline-corrected with a multi-point baseline routine using the Mesternova Software (v. 10.0, Mestrelab Research, SL, Santiago de Compostela, Spain).

Transient absorption spectroscopy

All transient absorption kinetic data were collected with an LP980 flash photolysis apparatus (Edinburgh Instrument Ltd, UK) at room temperature. A tunable Opolette 355 HD (Opotek Inc., CA) ns pulsed laser equipped with a YAG source and employing OPO technology for wavelength tunability was employed as a pump light source. The pump laser pulses (ca. 7 ns each) were delivered at 488 nm, with an energy of ca. 5–7 mJ per pulse corresponding to a power of ca. 7–10 × 105 W. A flash lamp (150 W, xenon lamp) producing flashes of ca 6 ms duration was employed as a probe pulse and turned on at time zero of each scan, followed by the ns pump pulse after ca 7–8 μs. A quartz cuvette with a 10 mm path-length (111.070-QS, Hellma USA Inc.) was used. All samples contained 5 % D2O, 10 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0±0.2), catalytic amounts of GO-CAT enzymes and 2.5 mM D-glucose. Transient absorption kinetic data on fluorescein (40 μM) were collected in the absence and presence of heavy-atom-containing additives. Time-dependent triplet-triplet absorption data were recorded at 650 nm. 100 scans were acquired for each triplet-state decay curve with an interscan delay of 1 s.

Determination of (S/N)t

The NMR sensitivity (S/N)t was deduced from eq. 4, and the signal-to-noise ratio S/N was determined according to

| (10) |

where S denotes the NMR signal, i.e., the resonance intensity riding above the noise envelope and <N>PTP is the average peak-to-peak noise amplitude. The noise was evaluated within the 6–7 and 8–9 ppm ranges.

Electronic absorption spectroscopy

Electronic absorption data were collected with a Hewlett-Packard 8452A diode-array spectrophotometer. A 1 cm path-length cuvette quartz cuvette was used (283 QS, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA).

Kinetic Simulations and curve fitting

The kinetic simulations of Figure 14 were carried out with MATLAB (The MathWorks Inc. Natick, MA, v. 2016a). The curve fitting of the transient absorption traces was carried out with Kaleida Graph 4.0 (Synergy Software, Reading, PA).

Figure 14.

A) Computed steady-state triplet-state concentration of fluorescein as a function of IPO concentration, assesses either by numerically solving the differential equations S11–S15 or by obtaining an approximate analytic solution of the differential equations according eq. 8. B) Experimental and computed normalized signal-to-noise ratio in the presence of photo-CIDNP (light conditions) as a function of IPO concentration. The signal-to-noise ratio was normalized so that the its value in the presence of photo-CIDNP and in the absence of IPO is equal to 1. The simulations assume that the only processes affected by IPO are the initial photoexcitation and the intersystem-crossing steps.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

This investigation details the development of a novel methodology to increase photo-CIDNP-mediated nuclear hyperpolarization in liquids by introducing small amounts of heavy-atom-containing molecules into NMR samples.

The neutral heavy-atom-bearing additive 3-iodo-1-propanol (IPO) augments the already significant photo-CIDNP enhancements by a factor of up to 2.5, leading to substantial increases in NMR sensitivity for the detection of aromatic-containing molecules.

IPO acts primarily by increasing the intersystem-crossing rate constant of the photo-CIDNP sensitizer dye while the apparent triplet decay rate constant stays unchanged. As a result, the transient T1 triplet population of the sensitizer dye increases, favoring the efficiency of photo-CIDNP.

As opposed to the above external heavy-atom effect, the internal heavy atom effect (consisting of introducing heavy-atom substituents directly into the covalent structure of the photosensitizer dye) perturbs the magnetic properties of the photo-sensitizer dye, with resulting suppression of photo-CIDNP-induced nuclear hyperpolarization.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Hanming Yang for a critical reading of the manuscript. We acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health (grants R21AI088551, S10RR13866-01 and S10OD012245) and from the University of Wisconsin-Madison (Bridge Funds from the College of Letters & Science). Y.O. was a recipient of an NIH Molecular Biophysics predoctoral training fellowship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lee JH, Okuno Y, Cavagnero S. Sensitivity Enhancement in Solution NMR: Emerging Ideas and New Frontiers. J Magn Reson. 2014;241:18–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hore PJ, Broadhurst R. Photo-CIDNP of Biopolymers. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 1993;25:345–402. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hore PJ, Kaptein R. NMR Spectroscopy: New Methods and Applications. ACS Publications; 1982. Photochemically Induced Dynamic Nuclear Polarization (Photo-CIDNP) of Biological Molecules Using Continuous Wave and Time-Resolved Methods; pp. 285–318. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goez M. Pulse Techniques for CIDNP. Conc Magn Reson A. 1995;7:263–279. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okuno Y, Cavagnero Yusuke. Photochemically Induced Dynamic Nuclear Polarization: Basic Principles and Applications. eMagRes; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuhn LT. Hyperpolarization Methods in NMR Spectroscopy. Springer; 2013. Photo-CIDNP NMR Spectroscopy of Amino Acids and Proteins; pp. 229–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goez M, Kuprov I, Hun Mok K, Hore PJ. Novel Pulse Sequences for Time-Resolved Photo-CIDNP. Mol Phys. 2006;104:1675–1686. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyon CE, Jones JA, Redfield C, Dobson CM, Hore P. Two-Dimensional 15N-1H Photo-CIDNP as a Surface Probe of Native and Partially Structured Proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:6505–6506. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sekhar A, Cavagnero S. 1H Photo-CIDNP Enhancements in Heteronuclear Correlation NMR Spectroscopy. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:8310–8318. doi: 10.1021/jp901000z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sekhar A, Cavagnero S. EPIC-and CHANCE-HSQC: Two 15 N-Photo-CIDNP-Enhanced Pulse Sequences for the Sensitive Detection of Solvent-Exposed Tryptophan. J Magn Reson. 2009;200:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JH, Sekhar A, Cavagnero S. 1H-Detected 13C Photo-CIDNP as a Sensitivity Enhancement Tool in Solution NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:8062–8065. doi: 10.1021/ja111613c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grosse S, Yurkovskaya AV, Lopez J, Vieth H-M. Field Dependence of Chemically Induced Dynamic Nuclear Polarization (CIDNP) in the Photoreaction of N-Acetyl Histidine with 2, 2′-Dipyridyl in Aqueous Solution. J Phys Chem A. 2001;105:6311–6319. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JH, Cavagnero S. A Novel Tri-Enzyme System in Combination with Laser-Driven NMR Enables Efficient Nuclear Polarization of Biomolecules in Solution. J Phys Chem B. 2013;117:6069–6081. doi: 10.1021/jp4010168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okuno Y, Cavagnero S. Fluorescein: a Photo-CIDNP Sensitizer Enabling Hyper-Sensitive NMR Data Collection in Liquids at Low Micromolar Concentration. J Phys Chem B. 2016 doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b12339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vollenweider JK, Fischer H, Hennig J, Leuschner R. Time-Resolved CIDNP in Laser Flash Photolysis of Aliphatic Ketones. A Quantitative Analysis. Chem Phys. 1985;97:217–234. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreilick RW, Weissman S. Hydrogen Atom Transfer Between Free Radicals and Their Diamagnetic Precursors. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88:2645–2652. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Closs G, Sitzmann E. Measurements of Degenerate Radical Ion-Neutral Molecule Electron Exchange by Microsecond Time-Resolved CIDNP. Determination of Relative Hyperfine Coupling Constants of Radical Cations of Chlorophylls and Derivatives. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:3217–3219. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsentalovich YP, Morozova OB, Yurkovskaya AV, Hore P. Kinetics and Mechanism of the Photochemical Reaction of 2, 2′-Dipyridyl with Tryptophan in Water: Time-Resolved CIDNP and Laser Flash Photolysis Study. J Phys Chem A. 1999;103:5362–5368. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morozova OB, Yurkovskaya AV, Tsentalovich YP, Forbes MD, Sagdeev RZ. Time-Resolved CIDNP Study of Intramolecular Charge Transfer in the Dipeptide Tryptophan-Tyrosine. J Phys Chem B. 2002;106:1455–1460. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muszkat K. Effects of Acid-Base Equilibrium on Photo-CIDNP in Nitroaromatic Compounds. Chem Phys Lett. 1977;49:583–587. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muszkat K, Gilon C. Chemically Induced Dynamic Nuclear Polarisation of Tyrosyl Protons: Leucine-Enkephalin and Di-and Tri-Tyrosine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1977;79:1059–1064. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(77)91112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muszkat K, Gilon C. CIDNP in Tyrosyl Protons of Luliberin. Nature. 1978;271:685–686. doi: 10.1038/271685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turro NJ, Ramamurthy V, Scaiano JC. Principles of Molecular Photochemistry: an Introduction. University science books; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stone A. g Tensors of Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Mol Phys. 1964;7:311–316. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khudyakov IV, Serebrennikov YA, Turro NJ. Spin-Orbit Coupling in Free-Radical Reactions: On the Way to Heavy Elements. Chem Rev. 1993;93:537–570. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kasha M. Collisional Perturbation of Spin-Orbital Coupling and the Mechanism of Fluorescence Quenching. A Visual Demonstration of the Perturbation. J Chem Phys. 1952;20:71–74. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGlynn S, Azumi T, Kinoshita M. The Triplet State. Prentiee-Hall; New York: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaptein R. Simple Rules for Chemically Induced Dynamic Nuclear Polarization. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1971:732–733. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiryutin AS, Morozova OB, Kuhn LT, Yurkovskaya AV, Hore P. 1 H and 13C Hyperfine Coupling Constants of the Tryptophanyl Cation Radical in Aqueous Solution from Microsecond Time-Resolved CIDNP. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:11221–11227. doi: 10.1021/jp073385h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okuda M, Momose Y, Niizuma S, Koizumi M. ESR Studies on the Behavior of Fluorescein Semiquinone. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1967;40:1332–1338. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spera S, Bax A. Empirical Correlation Between Protein Backbone Conformation and C. Alpha. and C. Beta. 13C Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Chemical Shifts. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:5490–5492. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sagdeev R, Salikhov K, Molin Y. Photolysis of Micellar Solutions of Dibenzyl Ketones and Phenylbenzyl Ketones at 145000 G Observation of a ΔgH Effect on the Cage Reaction. 1982. Photochemistry in Ultrahigh Laboratory Magnetic Fields. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarna T, Zajac J, Bowman M, Truscott T. Photoinduced Electron Transfer Reactions of Rose Bengal and Selected Electron Donors. J Photochem Photobiol A: Chem. 1991;60:295–310. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muszkat K, Weinstein M. CIDNP Studies of Photochemical Hydrogen Atom Abstraction from Phenols. Z Phys Chem. 1976;101:105–114. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sugiura Y. Production of Free Radicals from Phenol and Tocopherol by Bleomycin-Iron (II) Complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1979;87:649–653. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(79)91843-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yankelevich A, Khudyakov I, Levin P, Serebrennikov YA. Chemical Polarization of Nuclei in Reactions of Photoreduction of Benzophenone and the Effect of a Heavy Atom. Russ Chem Bull. 1989;38:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiss MA, Nguyen DT, Khait I, Inouye K, Frank BH, Beckage M, O’Shea E, Shoelson SE, Karplus M, Neuringer LJ. Two-Dimensional NMR and Photo-CIDNP Studies of the Insulin Monomer: Assignment of Aromatic Resonances with Application to Protein Folding, Structure, and Dynamics. Biochemistry. 1989;28:9855–9873. doi: 10.1021/bi00451a046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steiner U, Winter G. Position Dependent Heavy Atom Effect in Physical Triplet Quenching by Electron Donors. Chem Phys Lett. 1978;55:364–368. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chmyrov A, Sandén T, Widengren J. Iodide as a Fluorescence Quencher and Promoter-Mechanisms and Possible Implications. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:11282–11291. doi: 10.1021/jp103837f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGlynn S, Sunseri R, Christodouleas N. External Heavy-Atom Spin-Orbital Coupling Effect. I. The Nature of the Interaction. J Chem Phys. 1962;37:1818–1824. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murrell J. The Effect of Paramagnetic Molecules on the Intensity of Spin-Forbidden Absorption Bands of Aromatic Molecules. Mol Phys. 1960;3:319–329. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dijkgraaf C, Hoijtink G. Environmental Effects on Singlet-Triplet Transitions in Aromatic Molecules. Tetrahedron. 1963;19:179–187. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin K, Lin S. Theoretical Calculation of an External Heavy-Atom Effect on the Spin-Orbit Coupling of the Benzene Molecule. Mol Phys. 1971;21:1105–1122. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramakrishnan V, Sunseri R, McGlynn S. External Heavy-Atom Spin-Orbital Coupling. IV. Equilibrium Investigations. J Chem Phys. 1966;45:1365–1366. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klimchuk E, Makarov B, Serebrennikov YA, Khudyakov I. Effect of an External Heavy Atom on the EPR Spectrum of the Fluorescein Semiquinone Radical. Bull Acad Sci USSR Div Chem Sci. 1989;38:1627–1630. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klimchuk E, Khudyakov I, Margulis L, Kuz’min V. Effect of an External Magnetic Field on the Yield of Radicals during the Photoreduction of Xanthene Dyes in Viscous Media. Russ Chem Bull. 1988;37:2462–2467. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klimtchuk E, Irinyi G, Khudyakov I, Margulis L, Kuzmin V. Effect of Magnetic Field on Radical Yields During the Photoreduction of Xanthene Dyes in Viscous Media. J Chem Soc Faraday Trans 1. 1989;85:4119–4128. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Minaev B, Danilovich I, Serebrennikov YA. Dynamics of Triplet Excitations in Molecular Crystals. Naukova Dumka; Kiev (in Russ): 1989. p. 109. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Togashi DM, Szczupak B, Ryder AG, Calvet A, O’Loughlin M. Investigating Tryptophan Quenching of Fluorescein Fluorescence Under Protolytic Equilibrium. J Phys Chem A. 2009;113:2757–2767. doi: 10.1021/jp808121y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lindqvist L. A Flash Photolysis Study of Fluorescein. Almqvist & Wiksell; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gandin E, Lion Y, Van de Vorst A. Quantum Yield of Singlet Oxygen Production by Xanthene Derivatives. Photochem Photobiol. 1983;37:271–278. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fleming G, Knight A, Morris J, Morrison R, Robinson G. Picosecond Fluorescence Studies of Xanthene Dyes. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:4306–4311. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seybold PG, Gouterman M, Callis J. Calorimetric, Photometric and Lifetime Determinations of Fluorescence Yields of Fluorescein Dyes. Photochem Photobiol. 1969;9:229–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1969.tb07287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Penzkofer A, Beidoun A, Daiber M. Intersystem-Crossing and Excited-State Absorption in Eosin Y Solutions Determined by Picosecond Double Pulse Transient Absorption Measurements. J Lumin. 1992;51:297–314. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Joshi N, Gangola P, Pant D. Internal Heavy Atom Effect on the Radiative and Non-Radiative Rate Constants in Xanthene Dyes. J Lumin. 1979;21:111–118. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.