Abstract

Driving may increase mobility and independence for adolescents with autism without intellectual disability (ASD), however little is known about rates of licensure. To compare the proportion of adolescents with and without ASD who acquire a learner’s permit and driver’s license, as well as the rate at which they progress through the licensing system, we conducted a retrospective cohort study of 52,172 New Jersey residents born 1987–1995 who were patients of The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia healthcare network ≥ age 12; 609 (1.2%) had an ASD diagnosis. Electronic health records were linked to NJ’s driver licensing database (2004–2012). Kaplan-Meier curves and log-binomial regression models were used to determine the age at and rate of licensure and estimate adjusted risk ratios. One in 3 adolescents with ASD acquired a driver’s license vs. 83.5% for other adolescents and at a median of 9.2 months later. The vast majority (89.7%) of those with ASD who acquired a permit and were fully eligible to get licensed acquired a license within 2 years. Results indicated that a substantial proportion of adolescents with ASD do get licensed and that license-related decisions are primarily made prior to acquisition of a permit instead of during the learning-to-drive process.

Keywords: Driving, graduated driver licensing, high-functioning autism, mobility, teen drivers, transition to adulthood, transportation, young drivers

Introduction

The transition from adolescence to adulthood is particularly challenging for individuals with ASD and their families, as many of the services once received through special education are no longer available and adult services are more difficult to access (Lin et al., 2017; Taylor and Henninger, 2015). A recent report of data from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 reported that more than one in three young adults with ASD are disconnected (i.e., did not transition into either employment or education beyond high school), more than one in four are socially isolated, and nearly one in three have not had any community participation in the past year (Roux et al., 2015). These missed opportunities can have substantial long-term negative consequences on independence, well-being, and quality of life for the individual, as well as for their family and society as a whole. Thus, the authors of this report and others—including the Department of Health and Human Services’ interagency committee charged with advising the US on issues regarding autism spectrum disorders (ASD)—emphasize the importance of and urgent need for services that improve the functioning and quality of life of individuals with ASD as they transition from adolescence to adulthood (Geller and Greenberg, 2009; Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee, 2013).

An important milestone that typically occurs during adolescence is obtaining a license to drive. Licensure increases adolescents’ mobility by enabling independent travel to places of employment, school, and social activities (Winston and Senserrick, 2006), and more generally has been associated with positive outcomes such as autonomy, quality of life, and psychological well-being (Dickerson et al., 2007, Fonda et al., 2001). In particular for adolescents and young adults with ASD without intellectual disability (ID), successful licensure may increase their ability to seek employment and encourage community and social engagement. In turn, this may then serve to improve long-term physical and mental health and reduce maladaptive behaviors (Taylor et al., 2014).

Despite the potential importance of driving as a means to enhance independence in this population, very little is known about driving among adolescents with ASD (Classen and Monahan, 2013a). In a recent survey of parents of adolescents recruited through a national ASD organization, the majority (63%) reported that their teen was driving or planned to drive (Huang et al. 2012). This suggests that driving is an important issue for a significant proportion of families with ASD. However, findings from this and several other surveys of adolescents with ASD or their parents suggest that licensing rates may be substantially lower that the proportion of parents who express interest (Farley et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2012; Roux et al., 2015). Notably, none of the above-mentioned studies were designed specifically to examine rates of licensure among adolescents with ASD and how these rates compare with those of other adolescents; all were based on self- or parent-reports and two of the three included convenient samples. Further, we do not currently know the rate at which adolescents with ASD progress through state-level Graduated Driver Licensing (GDL) systems, which provide structure for parents to support and monitor their teen driver as they are phased into more challenging driving conditions and have proved to be effective in reducing the burden of adolescent crashes (Williams et al., 2012). A more detailed understanding of the extent to which adolescents with ASD become independently licensed to drive—and how the timing of licensure and progression thorough GDL differs compared with other adolescents—is an important first step towards establishing the evidence base for future development of tailored clinical-, educational-, and training-based interventions for families of adolescents with ASD.

To this end, we conducted the first longitudinal study focused on examining driving outcomes among adolescents and young adults with ASD. Specifically, we identified via electronic health records (EHR) a cohort of over 52,000 children who resided in New Jersey (NJ) and were patients of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) pediatric healthcare network and linked their records to records from NJ’s statewide traffic databases. The overall objective of this initial study was to establish current rates and patterns of licensure among adolescents and young adults with autism. To do this, we compared the proportion of adolescents with and without ASD who acquire a learner’s permit and driver’s license and determined whether adolescents with ASD progress more slowly through GDL.

Methods

Cohort Selection

Individuals for this retrospective cohort study were identified from the CHOP healthcare network. CHOP serves a socioeconomically and racially diverse patient population at >50 inpatient and outpatient locations throughout southeastern Pennsylvania and southern NJ. CHOP providers manage all aspects of clinical care using a unified and linked EHR system (EpicCare®, Epic Systems, Inc., Madison, WI). We queried this system to select individuals who were born 1987–1995 and had a CHOP visit as a NJ resident within 4 years of becoming eligible for their learner’s permit at 16 years old (i.e., age 12–15). Given that we could not accurately identify when patients might have migrated out of NJ, we limited the study population to those who maintained NJ residency through their last CHOP visit, which occurred at a median of 15.7 years old (interquartile range [IQR]: 14.1, 18.0) (n=52,713). We then excluded 491 individuals who had intellectual disability (ID), given that an ID diagnosis would likely remove an individual from the pool of eligible drivers. ID was defined as the presence of an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis code beginning with ‘317,’ ‘318,’ or ‘319’ either from a CHOP office visit or on the individual’s list of known medical conditions (i.e., “problem list”). After exclusions, there was a total of 52,222 individuals in the study cohort.

Patients were classified as having ASD if they had an ICD-9-CM diagnosis code beginning with ‘299,’ ‘299.0,’ or ‘299.8’ either at a CHOP office visit or on their problem list. To assess validity of this algorithm, we hand-reviewed the entire EHR of all individuals classified with ASD. Of these, three were confirmed not to have ASD and were reclassified as non-ASD. All others were classified as having ASD; we were able to locate independent sources in the EHR confirming ASD diagnosis (e.g., letters, provider notes) for the majority (77%) of these cases. In addition, we hand-reviewed 29 individuals who did not have the aforementioned ASD codes but had a diagnosis of ‘299.1’ (childhood disintegrative disorder) or ‘299.9’ (unspecified pervasive developmental disorder) in order to identify patients who had ASD but were miscoded; this yielded an additional 14 cases of ASD. In total, we identified 609 patients (1.2%) with ASD and 51,613 (98.8%) without ASD. The vast majority of individuals with ASD (91%) were classified via visit-level diagnostic codes.

NJ driver licensing data

Young drivers in NJ progress through three GDL phases: (1) learner’s permit: eligible at a minimum age of 16, 6-month minimum holding period (those permitted at age 21 or older have a 3-month holding period), and drivers must be supervised by a licensed adult; (2) intermediate (restricted) license: eligible at age 17, 1-year minimum holding period, and drivers can drive unsupervised but are restricted from driving with multiple passengers or from 11:00 p.m. through 4:59 a.m. (those who initiate GDL at age 21 or older are exempt from these restrictions); and (3) unrestricted (basic) license: eligible at age 18 and following completion of phases 1 and 2, and drivers can drive unsupervised without restrictions. Graduation to an unrestricted NJ license is not automatic after one year; intermediate drivers must present to a NJ licensing office to upgrade to an unrestricted license.

We obtained individual-level records on all those who obtained a NJ driver license from January 2004 through June 2012 from the NJ Motor Vehicle Commission’s licensing database. The database included dates related to each driver’s progression through NJ’s licensing system, including: date of birth, acquisition of a permit and intermediate license, license-related transactions, and death. We used these data elements to construct each driver’s age at acquisition of their permit, intermediate license, and unrestricted license. Further details are available elsewhere (Curry et al., 2013).

Linkage of EHR and licensing data

EHR and licensing data were linked via a hierarchical deterministic linkage process conducted in six sequential phases. Data elements used for the linkage included: date of birth, last name, first name, middle initial, sex, zip code, and city and street number of residence. Linkage quality was assessed via hand-review of a sample of over 3,000 matched records; we estimated the final true match rate (i.e., proportion of accepted matches that were true matches) to be 99.95%. To assess a false non-match rate (i.e., true matches that were not found), we searched for the five most likely potential matches for a random sample of 474 EHR records that were ultimately unmatched; we estimated the false non-match rate to be low (1.5%).

Other relevant variables

Sex, age, and race/ethnicity were ascertained from the EHR. Insurance payor at last CHOP visit (self-pay, Medicaid, private) was used as a proxy for individual-level socioeconomic status. We used the 2007–2011 American Community Survey to categorize NJ zip code of residence at last CHOP visit into quintiles of median household income and 2010 Census Gazetteer Files to categorize those zip codes into quintiles of population density (people per square mile) (United States Census Bureau, 2010b, 2011).

Analytic approach

Analyses were restricted to 609 adolescents with ASD and 51,563 adolescents without ASD who had at least one full month of follow-up after becoming age-eligible for a permit at age 16. Individuals were followed for license outcomes from age 16.0 until death, end of the study period, or final license expiration, whichever occurred first. We compared the distribution of relevant characteristics among ASD and non-ASD groups using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to graphically depict the cumulative proportion of individuals licensed over time. The probability of each licensing outcome by specified ages was also estimated among those with complete follow-up through that age using multivariable log-binomial regression models to directly estimate risk ratios (RR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). Adjusted models included potential confounders chosen a priori based on known or suspected association with ASD (or its clinical diagnosis) and driving outcomes, including: sex, race/ethnicity, insurance payor, and indicators for household income and population density. We also controlled for birth year to ensure comparison among individuals who were eligible for licensure in the same calendar year. We assessed whether the adjusted association between ASD and permit/licensure varied by sex via likelihood ratio tests; there was no evidence of effect modification (on the multiplicative scale) by sex.

In complementary analyses, we compared the rate at which young drivers who began the licensing process progressed through NJ’s GDL system. Thus, for each individual who had acquired a learner’s permit, we determined the time from full eligibility for an intermediate license to acquisition of that license. Further, for each individual who acquired an intermediate license, we determined the time from full eligibility for an unrestricted license to acquisition of that license. Full eligibility for each phase began either at the appropriate minimum eligible age for that phase or the end of the minimum holding period of the previous phase, whichever came later. Analyses were conducted in SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). This study was approved by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Institutional Review Board.

Results

Description of study population

Relevant characteristics of the study cohort are shown in Table 1. Individuals were followed for a median of 4.5 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 2.4, 6.7) after becoming age-eligible for a permit at 16.0. Individuals with ASD were on average younger than those without ASD at the end of the study period (median: 19.6 [18.0, 21.4] vs. 20.5 [18.4, 22.7], respectively; P<0.001). Those with ASD were more likely to be male, non-Hispanic white, and have private insurance.

Table 1.

Distribution of demographic and other relevant characteristics, overall study cohort and by autism spectrum disorder (ASD) status.

| Overall (N=52,172) | Cohort | ASD | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| No (N=51,563) | Yes (N=609) | ||||||

| Age at last CHOP visit, median (IQR), y | 15.7 (14.1–18.0) | 15.7 (14.1–18.0) | 17.0 (14.6–19.1) | <.001 | |||

| Age at end of study period, median (IQR), y | 20.5 (18.4–22.7) | 20.5 (18.4–22.7) | 19.6 (18.0–21.4) | <.001 | |||

| Sex, No. (%) | <.001 | ||||||

| Female | 25,152 | 48.2 | 25,034 | 48.6 | 118 | 19.4 | |

| Male | 27,019 | 51.8 | 26,528 | 51.4 | 491 | 80.6 | |

| Missing | 1 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | <.001 | ||||||

| Hispanic | 2,022 | 3.9 | 2,006 | 3.9 | 16 | 2.6 | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 36,941 | 70.8 | 36,460 | 70.7 | 481 | 79.0 | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 6,185 | 11.8 | 6,137 | 11.9 | 48 | 7.9 | |

| Non-Hispanic other/multiple race | 6,925 | 13.3 | 6,861 | 13.3 | 64 | 10.5 | |

| Missing | 99 | 0.2 | 99 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Payor at last CHOP visit, No. (%) | <.001 | ||||||

| Medicaid | 2,149 | 4.1 | 2,103 | 4.1 | 46 | 7.5 | |

| Private | 42,950 | 82.3 | 42,417 | 82.2 | 533 | 87.5 | |

| Self-pay | 88 | 0.2 | 84 | 0.2 | 4 | 0.7 | |

| Not recorded or billed | 6,985 | 13.4 | 6,959 | 13.5 | 26 | 4.3 | |

| Zip code level median household income, quintile, No. (%) | 0.54 | ||||||

| 1 (≤ $57,226) | 9,715 | 18.6 | 9,609 | 18.6 | 106 | 17.4 | |

| 2 ($57,227 – $72,857) | 15,279 | 29.3 | 15,111 | 29.3 | 168 | 27.6 | |

| 3 ($72,858 – $87,222) | 11,272 | 21.6 | 11,136 | 21.6 | 136 | 22.3 | |

| 4 ($87,223 – $105,888) | 9,687 | 18.6 | 9,572 | 18.6 | 115 | 18.9 | |

| 5 (≥$105,889) | 6,143 | 11.8 | 6,060 | 11.8 | 83 | 13.6 | |

| Missing | 76 | 0.1 | 75 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Zip code level population density (pop/sq mile), quintile, No. (%) | 0.91 | ||||||

| 1 (≤417) | 6,568 | 12.6 | 6,488 | 12.6 | 80 | 13.1 | |

| 2 (418 – 1,223) | 13,208 | 25.3 | 13,047 | 25.3 | 161 | 26.4 | |

| 3 (1,224 – 2,610) | 17,128 | 32.8 | 16,928 | 32.8 | 200 | 32.9 | |

| 4 (2,621– 4,864) | 12,673 | 24.3 | 12,534 | 24.3 | 139 | 22.8 | |

| 5 (≥4,865) | 2,558 | 4.9 | 2,529 | 4.9 | 29 | 4.8 | |

| Missing | 37 | 0.1 | 37 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | |

Acquisition of learner’s permit and driver’s license

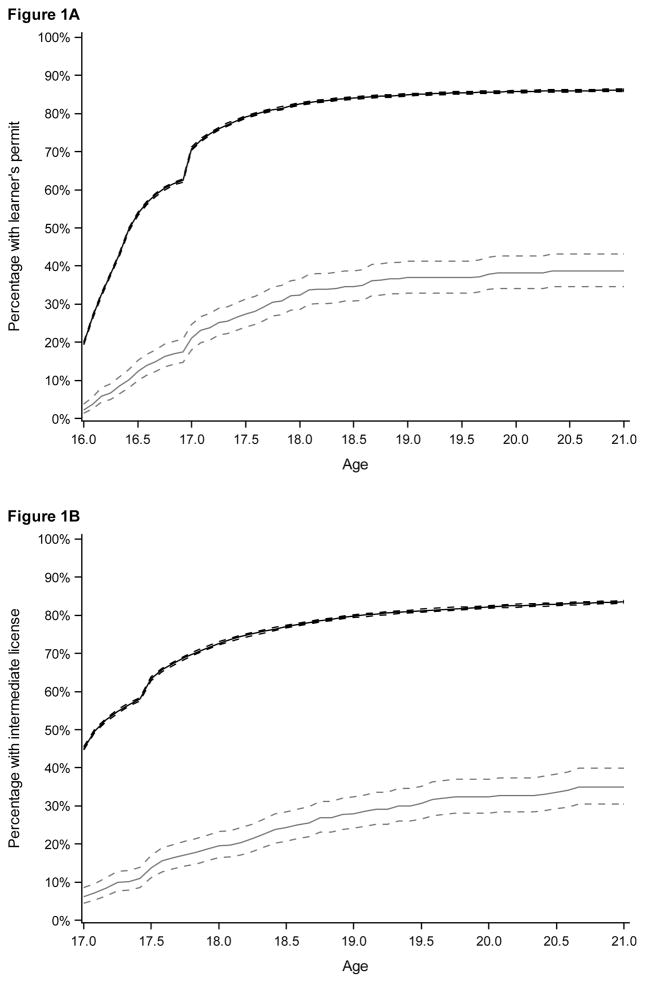

Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier curves depicting the cumulative proportion of individuals who obtained a learner’s permit and intermediate driver’s license, by ASD status, are shown in Figures 1a and 1b, respectively. As shown in Table 2, a total of 17.1% of individuals with ASD acquired a learner’s permit within one year of becoming age-eligible compared with 62.4% of adolescents without ASD (adjRR: 0.28; 95% CI: 0.23, 0.33). By age 21, 38.3% of individuals with ASD had acquired a learner’s permit, 34.4% an intermediate license, and 22.8% an unrestricted license. Among those who did acquire a permit during the study period, individuals with ASD did so a median of 7.2 months later

Figure 1.

Parts a–b. Cumulative percentage of subjects who acquired: (a) a learner’s permit and (b) an intermediate license from minimum eligible age, by ASD status.

Grey line: ASD; black line: No ASD. Dotted lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Minimum eligible age is 16.0 for permit and 17.0 for intermediate license. Percentages were estimated via inverse Kaplan-Meier curves. Log-rank test P-value for: (a) <0.001; (b) <0.001.

Table 2.

Acquisition of a learner’s permit, intermediate license, and unrestricted license comparing adolescents with and without ASD.

| ASD | No ASD | Adjusted (95% CI) RRa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Total N | Licensed N (%) | Total N | Licensed N (%) | ||

| Learner’s permit | |||||

| By age 17.0b | 556 | 95 (17.1) | 48,113 | 30,023 (62.4) | 0.28 (0.23, 0.33) |

| By age 21.0c | 180 | 69 (38.3) | 22,728 | 19,438 (85.5) | 0.44 (0.36, 0.53) |

| Intermediate license | |||||

| By age 18.0b | 454 | 82 (18.1) | 41,305 | 29,504 (71.4) | 0.25 (0.21, 0.31) |

| By age 21.0c | 180 | 62 (34.4) | 22,728 | 18,977 (83.5) | 0.39 (0.32, 0.49) |

| Unrestricted license | |||||

| By age 19.0b | 353 | 44 (12.5) | 34,837 | 16,066 (46.1) | 0.24 (0.18, 0.33) |

| By age 21.0c | 180 | 41 (22.8) | 22,728 | 14,134 (62.2) | 0.34 (0.26, 0.46) |

Risk ratios were estimated using multivariable log-binomial regression models. Models were adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, insurance status at last CHOP visit (private vs Medicaid/self-pay), birth year, and zip code quintiles of median household income and population density (with combined 4th and 5th quintiles).

Minimum eligible age: learner’s permit: 16.0; intermediate license: 17.0; unrestricted license: 18.0. Frequencies and risk ratios were estimated among subjects who were followed until noted age (which is equivalent to one year after minimum eligible age).

Frequencies and risk ratios were estimated among subjects who were followed until age 21.0.

ASD=autism spectrum disorders; RR=risk ratios; CI=confidence intervals.

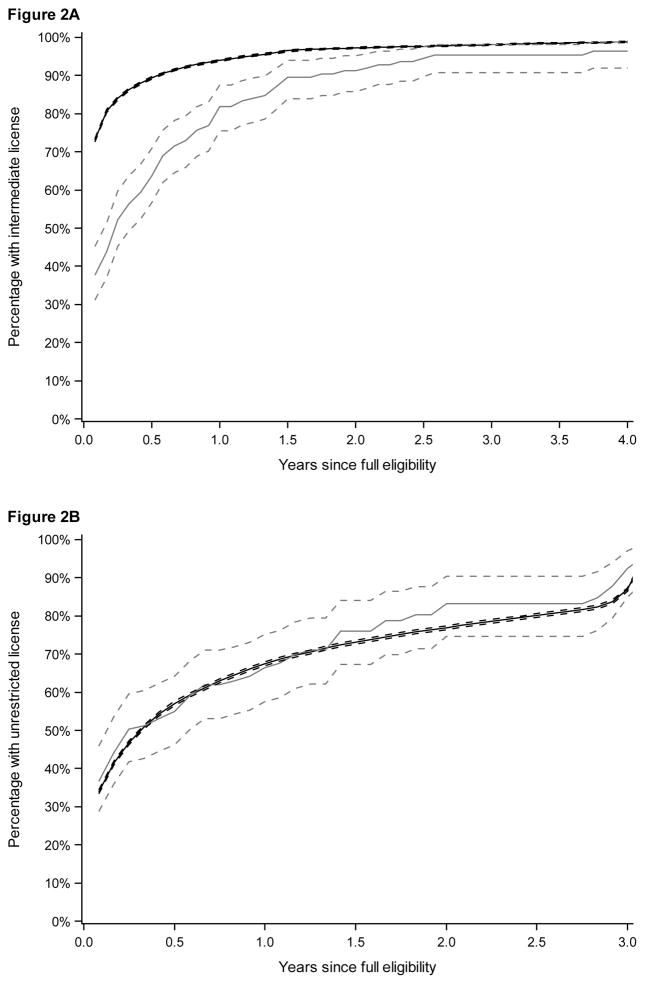

Rate of progression through GDL system

Among individuals with a permit who became fully eligible to acquire an intermediate driver’s license, 81.9% with ASD and 94.1% without ASD got licensed within 12 months (adjRR: 0.86; 95% CI: 0.79 0.94) (Table 3). For individuals followed at least 24 months after full eligibility, proportions increased to 89.7% and 97.7%, respectively (adjRR: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.86, 0.99). Among those with an intermediate license, individuals with and without ASD had a similar progression to acquiring an unrestricted license within 12 months of full eligibility (65.5% and 67.3%, respectively; adjRR: 0.97, 95% CI: 0.84, 1.11). The trajectory of obtaining an intermediate license after becoming fully eligible was a median of 2 months later for those with ASD than those without ASD (3 [1, 7] vs. 1 [1, 1] months post-eligibility, P<0.001) (Figure 2a), while time to an unrestricted license from full eligibility was not significantly different between those with and without ASD (Figure 2b) (2 [1, 12] vs. 3 [1, 12] months post-eligibility, P=0.45).

Table 3.

Acquisition of intermediate and unrestricted licenses from time of full eligibilitya, comparing adolescents with and without ASD.

| ASD | No ASD | Adjusted (95% CI) RRb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Total N | Licensed N (%) | Total N | Licensed N (%) | ||

| Intermediate license | |||||

| Within 1 yr. of full eligibilityac | 138 | 113 (81.9) | 33,876 | 31,880 (94.1) | 0.86 (0.79, 0.94) |

| Within 2 yrs. of full eligibilityac | 107 | 96 (89.7) | 28,280 | 27,627 (97.7) | 0.92 (0.86, 0.99) |

| Unrestricted license | |||||

| Within 1 yr. of full eligibilityac | 87 | 57 (65.5) | 27,109 | 18,234 (67.3) | 0.97 (0.84, 1.11) |

| Within 2 yrs. of full eligibilityac | 62 | 51 (82.3) | 21,887 | 16,629 (76.0) | 1.06 (0.95, 1.19) |

Full eligibility defined as: (a) for intermediate license: at least 17.0 years old and held permit for at least 6 months if permit acquired under age 21 or 3 months if permit acquired at age 21 or older; (b) for unrestricted license: at least 18.0 years old and held intermediate license for at least 1 year.

Risk ratios estimated using multivariable log-binomial regression models. Models were adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, insurance status at last CHOP visit (private vs Medicaid/self-pay), birth year, and zip code quintiles of median household income and population density (with combined 4th and 5th quintiles).

Frequencies and risk ratios were estimated among those who were followed for this length of time after eligibility.

ASD=autism spectrum disorders; RR=risk ratios; CI=confidence intervals.

Figure 2.

Parts a–b. Cumulative percentage of subjects who acquired an: (a) intermediate licensure and (b) unrestricted license from full eligibility, by ASD status.

Grey line: ASD; black line: No ASD. Dotted lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Full eligibility for each phase began either at the minimum eligible age for that phase or end of the minimum holding period of previous phase, whichever came later. Percentages were estimated via inverse Kaplan-Meier curves. Log-rank test P-value for: (a) <0.001; (b) 0.45.

Discussion

Via a unique linkage of childhood EHR and driver licensing data, this longitudinal study is the first to provide detailed information on the proportion of adolescents with ASD who acquire a license and the rate at which they progress through the Graduated Driver Licensing system. While adolescents with ASD are licensed at rates much lower than adolescents without ASD, approximately 1 in 3 teens with ASD are successfully achieving licensure by age 21, the majority who get licensed do so in their 17th year. Further, the vast majority of adolescents with ASD who acquire a learner’s permit (≈90%) go on to get licensed, and do so at a rate only slightly slower than other adolescents.

In a previous survey we conducted with 297 parents of driving-eligible adolescents with ASD, 63% reported that their teen was driving or planned to drive (Huang et al., 2012). Combined with the findings from our current study, these data strongly suggest that driving is an important issue for a sizable proportion of families with ASD. Further, the number of adolescents interested in driving is likely to increase, as the CDC now estimates that almost half of all children identified ASD have average or above average intellectual ability (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). However, these results also suggest that there may be an important discrepancy between a strong interest in driving and relatively lower licensure rates among adolescents with ASD. This may in part reflect appropriate parental decision to prohibit licensure or a lack of teen interest. Transition to independent driving is a particularly risky time for adolescents (Curry et al., 2015b; Foss et al., 2014). Further, individuals with ASD typically have dysfunction in skills that have been shown to be critical to safe driving (Michon, 1978)—attention, executive functioning, processing speed, and motor coordination (Corbett and Constantine, 2006; Kenworthy et al., 2013; Oliveras-Rentas et al., 2012; Wallace et al., 2016)—and adolescents and young adults have demonstrated poorer driving performance on simulators (Classen et al., 2013; Cox et al., 2015; Reimer et al, 2013). However, it may also indicate parental concern among and/or a lack of support for potentially capable drivers. Parents of adolescents with ASD who were pursuing driving have reported difficulty teaching more complex driving skills (e.g., multitasking) (Cox et al., 2012). Further, parents’ degree of engagement as driving practice supervisors is associated with both self-efficacy and anticipated stress of teaching a teen to drive (Mirman, et al., 2014), which may be heightened among parents of adolescents with ASD (Montes and Halterman, 2007; Schieve et al., 2007). We have previously identified several factors that substantially increased the odds of their child being a driver, including experience teaching a teen to drive and inclusion of driving goals in an Individual Education Plan (Huang et al., 2012). These findings suggests that having efforts in place to support and increase the self-efficacy of parents—who bear much of the responsibility for teaching their child to drive—may lead to an increase in licensing. However, a recent study reported that half of 17-year-olds with ASD do not receive any transportation-related services; this increases to 70% for services between high school and their early 20s (Roux et al., 2015). The discrepancy between parental interest in driving and actual licensure rates highlights the need for future studies to identify the primary factors underlying families’ licensing decisions and develop ways to improve the learning-to-drive process for these families and enhance mobility among adolescents with ASD. Given the potential for heightened risk for adverse driving outcomes, future research that examines driving patterns, risky driving behaviors, and crash risk among these adolescents is also warranted.

Our findings also have direct implications on the most appropriate timing for tailored efforts and interventions for these families. The fact that the vast majority of teens with ASD who obtained a learner’s permit go on to become licensed indicates that the bulk of families decide whether to pursue licensure prior to getting a permit—that is, before their teen ever gets behind the wheel. This suggests that the critical window for clinicians and educators to support and educate these families about whether or not their teen should with ASD should drive is the period just before permit eligibility. Further research is needed to understand the needs of families as well as the needs of clinicians when counseling families about driving. In addition, previous research generally shows that: (1) drivers who are licensed at older ages experience lower crash rates in the first year after licensure; and (2) regardless of age at licensure, young drivers who extend the intermediate phase have lower crash risks than those who transition to an unrestricted license (Curry et al., 2015b; Lewis-Evans, 2010). Research that determines whether licensing age and/or the rate of progression through GDL is associated with adverse outcomes among teens with ASD is also needed to guide future recommendations.

Limitations of this study include the use of EHRs for identification of ASD diagnosis. Although we confirmed the presence of ASD in the majority of cases identified using our definition, it is possible that some adolescents who truly did not have ASD were misclassified. This would lead to an overestimate of licensing rates among adolescents with ASD. However, when we limited analyses only to those with confirmed ASD (n=475), the estimated proportion that acquired an intermediate license within 12 months of age-eligibility was similar to the main analysis (17.4% vs. 18.1%, respectively). Further, the frequency of ASD diagnosis in this study (1.2%) mirrors estimates of ASD in the general population (Christensen et al., 2016). In addition, although we were able to confirm NJ residence status for each member of our cohort through their last visit to CHOP, a certain proportion of individuals determined to be unlicensed in this study may have in fact moved to another jurisdiction and become licensed there. According to the 2006–2010 American Community Survey (ACS), an estimated 1.6% of 5- to 17-year-olds and 12.9% of 18- to 24-year-olds reported living in a different state than the previous year (United States Census Bureau, 2010a); notably, however, the ACS is designed to capture where an individual lives which—in particular for those of college age—may differ from their legal state of residence. This may have resulted in an underestimation of absolute licensing rates in both ASD and non-ASD groups and—if teens with ASD are less likely than other teens to leave the state—an underestimation of the association between ASD and licensure. Finally, it is important to note that NJ’s GDL system is unique in several ways, including having the highest minimum licensure age of 17 and being the only state that applies full GDL rules to all newly licensed drivers under age 21. Thus, it is likely that the distribution of licensing ages and progression through GDL differs in other jurisdictions. To the extent that families of teens with ASD base licensing decisions on age (e.g., delaying licensure until age 18), the magnitude of some estimates—e.g., difference in median licensing age—may be even greater in states with lower minimum licensing ages.

Conclusion

Finding a balance between autonomy and safety—that is, ensuring safe mobility—is likely to be a particularly sensitive challenge for families of adolescents with ASD without ID. This study begins to provide the critically needed epidemiologic foundation to inform the development and timing of driving interventions for families of teens with ASD. Most current parent-directed teen driving interventions are universal in nature (Curry et al., 2015a). However, tailored efforts are likely needed to support these families in making the most informed decisions about whether or not their teen should drive and prepare them—if appropriate—for safe, independent driving. There is still much to be learned about the issue of driving with ASD. In subsequent studies, we plan to identify adolescent- and parent-related factors that influence families’ licensing decisions, examine the rates and types of motor vehicle crashes and traffic citations among adolescents with ASD compared with other adolescents, explore how driving patterns of adolescents with ASD differ from older adolescents, and identify factors influencing families’ driving-related decisions.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by a CHOP Foerderer Grant of Excellence and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development at the National Institutes of Health [grant number 1R01HD079398; PI: Curry]. Funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The c;ontent is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of CHOP or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

None of the authors have a conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 Years — Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2014;63(2):1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen DL. Prevalence and characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder among children aged 8 Years — autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2012. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2016;65(3):1–23. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6503a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen S, Monahan M. Evidence-based review on interventions and determinants of driving performance in teens with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or Autism Spectrum Disorder. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2013a;14(2):188–193. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2012.700747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen S, Monahan M, Hernandez S. Indicators of simulated driving skills in adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Open Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2013b;1(4):2. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett BA, Constantine LJ. Autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: assessing attention and response control with the integrated visual and auditory continuous performance test. Child Neuropsychology: a journal on normal and abnormal development in childhood and adolescence. 2006;12(4–5):335–348. doi: 10.1080/09297040500350938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox NB, Reeve RE, Cox SM, et al. Brief report: driving and young adults with ASD: parents’ experiences. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42(10):2257–2262. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox SM, Cox DJ, Kofler MJ, et al. Driving simulator performance in novice drivers with Autism Spectrum Disorder: The role of executive functions and basic motor skills. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2015;46(4):1379–1391. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2677-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry AE, Peek-ASA C, Hamann CJ, et al. Effectiveness of parent-focused interventions to increase teen driver safety: A critical review. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015a;57(1):S6–S14. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry AE, Pfeiffer MR, Durbin DR, et al. Young driver crash rates by licensing age, driving experience, and license phase. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2015b;80:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2015.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry AE, Pfeiffer MR, Localio R, Durbin DR. Graduated driver licensing decal law: effect on young probationary drivers. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson AE, Molnar LJ, Eby DW, et al. Transportation and aging: A research agenda for advancing safe mobility. Gerontologist. 2007;47(5):578–590. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.5.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley MA, McMahon WM, Fombonne E, et al. Twenty-year outcome for individuals with autism and average or near-average cognitive abilities. Autism Research. 2009;2(2):109–118. doi: 10.1002/aur.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonda SJ, Wallace RB, Herzog AR. Changes in driving patterns and worsening depressive symptoms among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2001;56(6):S343–351. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.6.s343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss RD, Masten SV, Martell CA. Examining the safety implications of later licensure: Crash rates of older vs. younger novice drivers before and after Graduated Driver Licensing. Washington DC: AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Geller LL, Greenberg M. Managing the transition process from high school to college and beyond: Challenges for individuals, families, and society. Social Work in Mental Health. 2009;8(1):92–116. [Google Scholar]

- Huang P, Kao T, Curry AE, Durbin DR. Factors associated with driving in teens with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2012;33(1):70–74. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31823a43b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee. Strategic plan for Autism Spectrum Disorder research – 2013 update. 2014 Available at: http://iacc.hhs.gov/strategic-plan/2013/index.shtml.

- Kenworthy L, Yerys BE, Weinblatt R, et al. Motor demands impact speed of information processing in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Neuropsychology. 2013;27(5):529–536. doi: 10.1037/a0033599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Evans B. Crash involvement during the different phases of the New Zealand Graduated Driver Licensing System (GDLS) Journal of Safety Research. 2010;41(4):359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Pearl AM, Kong L, et al. A Profile on Emergency Department Utilization in Adolescents and Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2017;47(2):347–358. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2953-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michon JA. Dealing with danger. Groningen, The Netherlands: Traffic Research Centre of the University of Groningen; 1978. Available at: http://www.jamichon.nl/jam_writings/1979_dealing_with_danger.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Mirman JH, Curry AE, Wang W, et al. It takes two: A brief report examining mutual support between parents and teens learning to drive. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2014;69:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montes G, Halterman JS. Psychological functioning and coping among mothers of children with autism: a population-based study. Pediatrics. 2007;119(5):e1040–e1046. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveras-Rentas RE, Kentworthy L, Roberson RB, et al. WISC-IV profile in high-functioning Autism Spectrum Disorders: Impaired processing speed is associated with increased autism communication symptoms and decreased adaptive communication abilities. Journal Autism Developmental Disorders. 2012;42(5):655–664. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1289-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimer B, Fried R, Mehler B, et al. Brief report: examining driving behavior in young adults with high functioning autism spectrum disorders: a pilot study using a driving simulation paradigm. Journal of Autism Devevelopmental Disorder. 2013;43(9):2211–2217. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1764-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux AM, Shattuck PT, Rast JE, et al. National Autism Indicators Report: Transition into Young Adulthood. Philadelphia, PA: Life Course Outcomes Research Program, A.J. Drexel Autism Institute, Drexel University; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schieve LA, Blumberg SJ, Rice C, et al. The relationship between autism and parenting stress. Pediatrics. 2007;119(Suppl 1):S114–S121. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2089Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, Henninger NA. Frequency and correlates of service access among youth with autism transitioning to adulthood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2015;45(1):179–191. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2203-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, Smith LE, Mailick MR. Engagement in vocational activities promotes behavioral development for adults with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2014;44(6):1447–1460. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-2010-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 5-year estimates, county-to-county migration flows 2006–2010. 2010a Available at: http://www.census.gov/data/tables/2010/demo/geographic-mobility/county-to-county-migration-2006-2010.html.

- United States Census Bureau. Census Gazetteer Files. 2010b Available at: http://www.census.gov/geo/maps-data/data/gazetteer2010.html.

- United States Census Bureau. 2007–2011 American Community Survey 5-year estimates, ACS demographic and housing estimates. 2011 Available at: http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_11_5YR_DP05&prodType=table.

- Wallace GL, Yerys BE, Peng C, et al. Assessment and Treatment of Executive Function Impairments in Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Update. International Review of Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2016;51:85–122. [Google Scholar]

- Williams AF, Tefft BC, Grabowski JG. Graduated Driver Licensing research, 2010-present. Journal of Safety Research. 2012;43(3):195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston FK, Senserrick TM. Competent independent driving as an archetypal task of adolescence. Injury Prevention. 2006;12(Suppl):i1–i3. doi: 10.1136/ip.2006.012765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]