Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study is to investigate the impact of missed chemotherapy administrations (MCA) on the prognosis of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients treated with definitive chemoradiation therapy (CRT).

Materials and Methods

In total, 97 patients with NSCLC treated with definitive CRT were assessed for MCA due to toxicities. Logistic regression was used to determine factors associated with MCA. Kaplan-Meier curves, log-rank tests, and Cox Proportional Hazards models were conducted.

Results

MCA occurred in 39% (n = 38) of the patients. Median overall survival was 9.6 months for patients with MCA compared with 24.3 months for those receiving all doses (P = 0.004). MCA due to decline in performance status was associated with the worst survival (4.6 mo) followed by allergic reaction (10.0 mo), hematologic toxicity (11 mo), and esophagitis (17.2 mo, P = 0.027). In multivariate models, MCA was associated with higher mortality (hazard ratio, 1.97; P = 0.01) and worse progression-free survival (hazard ratio, 1.96; P = 0. 009).

Conclusions

MCA correlated with worse prognosis and increased mortality. Methods to reduce toxicity may improve administration of all chemotherapy doses and increase overall survival in NSCLC treated with CRT.

Keywords: missed chemotherapy, non-small cell lung cancer, chemoradiation therapy, toxicity, survival

The standard of care for unresectable non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is concurrent chemoradiation therapy (CRT). The use of CRT results in improvements in locoregional control and overall survival (OS) compared with sequential chemotherapy and radiation or either treatment alone. However, increased toxicities have accompanied the efficacy of concurrent CRT, which can often necessitate interruptions in treatment.1–3

When significant toxicity arises, Radiation Therapy Oncology Group protocols typically instruct holding chemotherapy before holding radiation therapy (RT). For example, when grade 3 esophagitis occurs, chemotherapy is stopped while RT continues, until grade 4 esophagitis arises. The importance of continuous uninterrupted RT has been well documented, and RT interruptions are a risk factor for worse OS and local recurrence-free survival in multiple malignancies, including NSCLC.4–8 Unlike missed RT, the impact of missed chemotherapy administrations (MCA) during primary treatment for patients with NSCLC is poorly studied. However, work in other malignancies, such as pancreatic ductal carcinoma, demonstrated that deviations from planned chemotherapy regimens are associated with worse outcomes and OS.9

Deviations from the initially prescribed treatment regimens are common during CRT for NSCLC, and documented rates of treatment-related toxicity interruptions range from 23% to 35%.10–12 Given the frequency with which treatment interruptions occur, understanding the impact of MCA becomes important to optimize the outcomes of CRT. Thus, the goal of this study is to investigate the impact of toxicity-related interruptions in chemotherapy administrations on the outcomes of NSCLC patients treated with definitive CRT. We hypothesized that MCA during CRT would result in reduced OS rates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Population

From March 2003 to September 2013, a cohort of 97 patients with histologically confirmed NSCLC who received definitive concurrent CRT were evaluated under an Institutional Review Board–approved protocol. Seventy-one patients received carboplatin doublets, 14 received cisplatin doublets, and 12 received single-agent chemotherapy. Patients were assessed through chart review for toxicity-related MCA. The number of missed or reduced chemotherapy doses and reasons for missed or reduced doses were documented and weekly laboratory data was acquired to assess hematologic toxicity (HemeTox). Patients with inoperable (due to medical comorbidities) stage II (n = 9) disease treated with definitive CRT were included, whereas patients with stage IV disease were excluded.

Pretreatment Evaluation

Pre-CRT workup included a complete history and physical examination, complete blood count, serum chemistry profile, chest x-ray, contrast-enhanced chest computed tomography scan, positron emission tomography scan, brain magnetic resonance imaging, and mass or nodal biopsy. Histological confirmation of the mediastinal lymph nodes was required for staging. Clinical staging was defined using the American Joint Committee on Cancer 7th-edition criteria.13

Treatment Planning

Patients were placed in a supine position with arms up to allow accurate reproducibility of the target lesion among treatment sessions. A large rigid pillow or mold was created for each patient. RT was delivered using 3-Dimensional conformal (3D-CRT) or intensity-modulated technique. RT was delivered through anteroposterior fields first to 40 Gy in 1.8 or 2 Gy/fraction/d followed by oblique fields to avoid the spinal cord for an additional 20 to 26 Gy for a total RT dose of typically 60 to 66 Gy. For involved bilateral mediastinal lymph nodes, intensity-modulated technique was used either from the onset of RT or for the boost/off-cord component of RT. The analytic anisotropic algorithm was used with tissue inhomogeneity corrections, with 6- or 15-MV photons used to deliver the RT. The radiation dose constraints for the spinal cord was <50 Gy, mean lung dose <20 Gy, lung V5 < 60% to 70%, and lung V20 < 37%.

The typical chemotherapy regimen consisted of intravenous infusional drug delivery consisting of paclitaxel (45 mg/m2) plus carboplatin (AUC = 2) or etoposide (50 mg/ m2) plus cisplatin (50 mg/m2). RT was delivered after the administration of chemotherapy, with RT beginning on Monday.

Criteria for Treatment Interruptions

At our institution, when significant toxicities arise, our preference is to continue RT and hold chemotherapy. Chemotherapy was held for Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0 (CTCAE) grade 2 absolute neutrophil count (ANC) or CTCAE grade 3 white blood cell count. Chemotherapy was also often held for CTCAE grade 3 esophagitis and occasionally CTCAE grade 2 esophagitis. Chemotherapy held for decline in performance status (PS) was defined as PS deterioration resulting in hospitalization.

Statistical Analysis

Initial analyses of baseline characteristics (contingency tables) of patients were conducted using χ 2 tests of significance and their corresponding P-values were evaluated. These were first analyzed for all the patients, followed by comparisons of patients with and without MCA and chemotherapy dose reduction. Continuous variables were assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Non-normally distributed variables were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Univariate logistic regression was used to determine which factors were significantly associated with MCA and variables with the lowest P-value were included in the multiple regression models. Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier curves for product limit survival estimates, progression-free survival (PFS), distant metastasis, and locoregional failure were computed for subjects. These curves were stratified on MCA status during CRT. Time was defined as the end of CRT to the event of interest. Reduced dose was included in the no MCA group for this analysis. Log-rank tests were used to compare survival and progression among strata. Survival analysis was carried out with Cox Proportional Hazards models and the number of variables in the multivariable models was determined on the basis of the number of events of interest, which is 1 variable per 10 events. Variables with the lowest P-values from univariate models were added to the multivariable model. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and the statistical level of significance was <0.05.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the 97 patients are shown in Table 1. Median follow-up time was 14.6 months (0.23 to 103.2 mo). Median tumor volume was 136.3 cm3.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristics | Overall Frequency | % With MCA | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.22 | ||

| Male | 56 | 34 | |

| Female | 41 | 46 | |

| Ethnicity | 0.68 | ||

| White | 83 | 39 | |

| African American | 7 | 29 | |

| Asian | 3 | 67 | |

| Hispanic | 4 | 50.0 | |

| Performance status | 0.77 | ||

| 0 | 61 | 38 | |

| 1 | 24 | 38 | |

| 2 | 9 | 56 | |

| 3 | 3 | 33 | |

| T stage | 0.47 | ||

| T0 | 2 | 50 | |

| T1 | 13 | 62 | |

| T2 | 34 | 35 | |

| T3 | 22 | 32 | |

| T4 | 26 | 38 | |

| N stage | 0.29 | ||

| N0 | 7 | 50.0 | |

| N1 | 9 | 50.0 | |

| N2 | 47 | 37.1 | |

| N3 | 34 | 40.0 | |

| Histology | 0.90 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 40 | 40 | |

| Poorly diff | 12 | 33 | |

| SCC | 45 | 40 | |

| Stage | 0.08 | ||

| IIA | 4 | 75 | |

| IIB | 5 | 0 | |

| IIIA | 34 | 32 | |

| IIIB | 54 | 44 | |

| Concurrent chemo type | 0.89 | ||

| Carboplatin doublet | 71 | 40 | |

| Cisplatin doublet | 14 | 43 | |

| Single-agent chemotherapy | 12 | 33 |

Chemo indicates chemotherapy; MCA, missed chemotherapy administration; poorly diff, poorly differentiated carcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Characteristics of Missed Chemotherapy

Characteristics of MCA or reduced chemotherapy dose are seen in Table 2. MCA occurred in 39% (n = 38) of patients. There were 6 patients with reduction in chemotherapy doses (none of whom went on to miss any chemotherapy administrations). The reasons for MCA included HemeTox (56%, n = 21), esophagitis (17%, n = 6), decline in PS (12%, n = 4), allergic reaction (5%, n = 2), neuropathy (2.5%, n = 1), fever (2.5%, n = 1), hemoptysis (2.5%, n = 1), and hypotension (2.5%, n = 1). Of the 21 patients who had MCA due to HemeTox, 11 had CTCAE grade 3 ANC nadirs and 10 had CTCAE grade 2 ANC nadirs. Of the 6 patients who had MCA due to esophagitis, 3 were due to CTCAE grade 3 esophagitis and 3 were due to CTCAE grade 2 esophagitis. MCA occurred at a median of 5 weeks (range, 1 to 6 wk) for CTCAE grade ≥2 HemeTox, at a median of 4 weeks (range, 2 to 6 wk) for CTCAE grade ≥2 esophagitis, at a median of 2.3 weeks (range, 2.1 to 2.4 wk) for decline in PS, and at a median of 0.8 weeks (range, 0 to 1.6 wk) for allergic reaction. Of the patients who had a MCA, 50% (n = 19) missed only 1 dose, 29% (n = 11) missed 2 doses, and 21% (n = 8) missed ≥3 doses.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics Stratified by Missed, Reduced, or Fulldose Chemotherapy

| Characteristics | Missed Chemo (%) | Chemo Reduction (%) | Full-dose Chemo (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histology | 0.99 | |||

| Adeno | 16 (55) | 2 (5) | 22 (40) | |

| SCC | 18 (40) | 3 (7) | 24 (53) | |

| Poorly diff | 4 (34) | 1 (8) | 7 (58) | |

| ECOG PS | 0.92 | |||

| 0 | 23 (37) | 4 (7) | 34 (56) | |

| 1 | 9 (38) | 2 (8) | 13 (54) | |

| 2 | 5 (56) | 0 (0) | 4 (44) | |

| 3 | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 2 (67) | |

| Sex | 0.26 | |||

| Male | 19 (34) | 5 (9) | 32 (57) | |

| Female | 19 (46) | 1 (2) | 21 (52) | |

| Stage | 0.07 | |||

| IIA | 3 (75) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | |

| IIB | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 4 (80) | |

| IIIA | 11 (32) | 0 (0) | 23 (68) | |

| IIIB | 24 (45) | 5 (9) | 25 (46) | |

| Elapsed days during RT* | 45 | 52 | 44 | 0.12 |

| Total RT dose (cGy)* | 6000 | 6450 | 6200 | 0.25 |

| TVol* | 108.9 | 253.2 | 138.3 | 0.49 |

| Missed/reduced doses | 0.22 | |||

| 1 | 19 (95) | 1 (5) | ||

| 2 | 11 (85) | 2 (15) | ||

| 3 + | 8 (73) | 3 (27) | ||

| Reason for MCA | 0.18 | |||

| HemeTox | 21 (91) | 2 (9) | ||

| Esophagitis | 6 (75) | 2 (25) | ||

| Decline in PS | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | ||

| Allergic reaction | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | ||

| Neuropathy | 1 (33) | 2 (67) | ||

| Fever | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | ||

| Hemoptysis | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | ||

| Hypotension | 1 (100) | 0 (0) |

Comparisons of median values.

Adeno indicates adenocarcinoma; chemo, chemotherapy; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HemeTox, hematologic toxicity; MCA, missed chemotherapy administration; poorly diff, poorly differentiated carcinoma; PS, performance status; RT, radiation therapy; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

MCA Impact on Survival

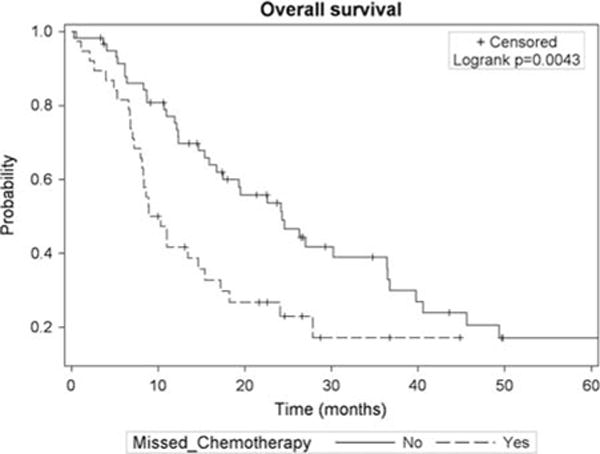

On univariate analysis, MCA was associated with increased mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 2.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.24-3.36; P = 0.005). Median OS (Fig. 1) was 9.6 months (95% CI, 8.0-15.4 mo) for patients who had an MCA compared with 24.3 months (95% CI, 15.9-36.4 mo) for those receiving all doses (P = 0.004). MCA due to decline in PS was associated with the worst survival (4.6 mo; 95% CI, 0.53-7.2 mo), followed by allergic reaction (10.0 mo; 95% CI, 8.9-11.0 mo), HemeTox (11 mo; 95% CI, 8-15.4 mo), and esophagitis (17.2 mo, 95% CI, 5.3-22.6mo; P<0.027). Dose reductions in chemotherapy (9.8 mo; 95% CI, 5.3-22.6 mo; P = 0.0007) were also associated with worse survival compared with treatment with full-dose chemotherapy. However, patients with MCA (9.6 mo) compared with those with dose reduction (9.8 mo) did not have significant differences in survival rates (P = 0.48). Patients who missed 1 dose of chemotherapy (14.6 mo; 95% CI, 8.1-19.5 mo) had better survival rates than those who missed 2 doses (8.4 mo; 95% CI, 6.2-27.8 mo) or ≥ 3 doses of chemotherapy (8.3 mo; 95% CI, 2.6-11 mo; P = 0.08).

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve for overall survival stratified by missed chemotherapy status.

Stage IIIB patients with MCA had the shortest survival rates (8.5 mo; 95% CI, 6.6-13.4 mo) with survival rates improving for stage IIIA and MCA (14.6 mo; 95% CI, 7.1-24.1 mo), stage IIIB with no MCA (15.4 mo; 95% CI, 8.7-26.6 mo), and stage IIIA with no MCA (45.6 mo; 95% CI, 26.3-78.2 mo; P = 0.0001). When adjusting for clinical-related and treatment-related factors (Table 3), MCA during CRT continued to be associated with increased mortality (HR, 1.97; 95% CI, 1.16-3.34; P = 0.01). Increasing age was also associated with worse mortality in the model (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01-1.07; P = 0.02).

TABLE 3.

Multivariate Analysis for OS, PFS, and DM

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OS | Missed chemotherapy | 1.97 (1.16–3.34) | 0.01 |

| Age | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 0.02 | |

| RT elapsed days | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | 0.16 | |

| Tumor volume | 1.001 (1.0–1.002) | 0.16 | |

| ECOG PS | 1.15 (0.83–1.58) | 0.40 | |

| 2 vs. 1 concurrent chemo agents | 0.64 (0.30–1.35) | 0.24 | |

| PFS | Missed chemo | 1.96 (1.19–3.24) | 0.009 |

| Age | 1.03 (0.99–1.06) | 0.10 | |

| RT elapsed days | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) | 0.06 | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 0.60 (0.27–1.31) | 0.20 | |

| Squamous cell | 0.48 (0.21–1.08) | 0.08 | |

| 2 vs. 1 concurrent chemo agent | 0.78 (0.36–1.66) | 0.51 | |

| Tumor volume | 1.001 (1.0–1.003) | 0.12 | |

| DM | Missed chemo | 2.13 (1.27–3.60) | 0.004 |

| Tumor volume | 1.001 (1.0–1.002) | 0.10 | |

| RT elapsed days | 1.02 (0.99–1.03) | 0.15 | |

| Female sex | 1.22 (0.73–2.03) | 0.45 | |

| Stage III | 0.79 (0.33–1.87) | 0.58 |

Chemo indicates chemotherapy; CI, confidence interval; DM, distant metastasis; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; RT, radiation therapy.

Neither pre-RT chemotherapy (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.49-1.39; P = 0.47) nor post-RT chemotherapy (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.40-1.32; P = 0.29) impacted survival on univariate analysis.

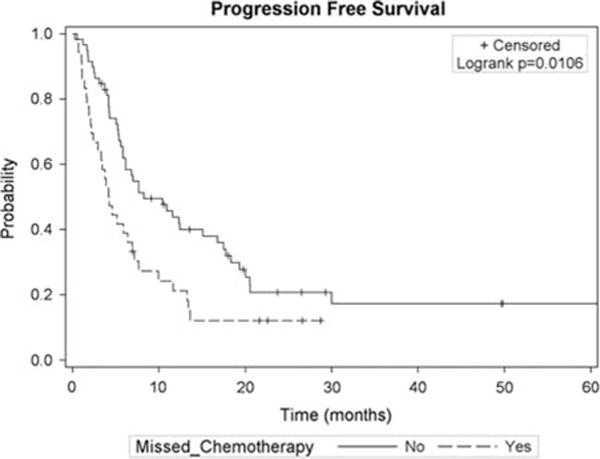

Missed Chemotherapy Impact on PFS

MCA (HR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.14-2.89; P = 0.01) was also a risk factor for worse PFS on univariate analysis. Patients with MCA had a median PFS time (Fig. 2) of 4.2 months (95% CI, 2.4-6.9 mo) compared with 8.3 months (95% CI, 5.87-16.8 mo) for those who received all doses (P = 0.01). However, dose reductions (8 mo; 95% CI, 1.2-19.3 mo) were not associated with worse PFS compared with full-dose chemotherapy (8.3 mo; 95% CI, 5.6-17.5 mo; P = 0.34).

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve for progression-free survival stratified by missed chemotherapy status.

Each MCA was associated with a 34% increased risk of disease progression (HR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.19-3.24; P = 0.009). When adjusting for patient, treatment, and tumor-related factors (Table 3) MCA continued to be associated with risk for worse PFS (HR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.14-3.36; P = 0.01). Increasing elapsed RT days (range, 29 to 116 d) trended toward increased risk of progression (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.99-1.05; P = 0.06).

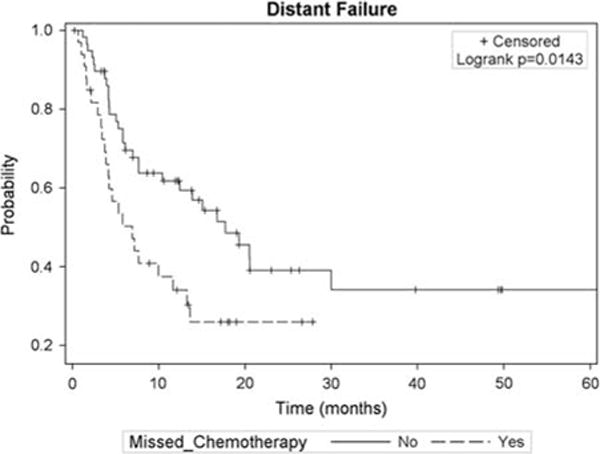

As seen in Figure 3, MCA was associated with earlier distant spread of disease (6.9 mo; 95% CI, 3.9-13.3 mo versus 17.7 mo for those with no MCA; 95% CI, 7.7-30.0 mo; P=0.01). Each MCA corresponded to 42% increased risk of distant spread of disease (HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.13-1.80; P = 0.0031). When adjusting for patient and treatment factors (Table 3), MCA was a risk for distant metastasis (HR, 2.13; 95% CI, 1.27-3.60; P = 0.004). However, MCA was not a risk for local progression (HR, 1.54; 95% CI, 0.72-3.30; P = 0.26).

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan-Meier curve for distant progression stratified by missed chemotherapy status.

DISCUSSION

MCA was associated with worse OS as well as shorter times to PFS and distant metastasis during definitive CRT. Reduced chemotherapy dose was an additional risk for worse OS. The most frequent causes of MCA were HemeTox (56%) and esophagitis (17%).

Treatment interruptions are common with CRT and range from 23% to 35% in the literature,13 which is similar to our rate of 39%. Decline in PS was associated with the worst survival (4.6 mo) and increasing Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group PS was a risk factor for worse survival in our analysis. Poor PS has long been acknowledged as a negative prognostic factor and reflects general health and systemic problems2,10–12; however, our study only included 12 patients with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group PS >2, thus limiting the generalizability of this part of the analysis.

The impact of MCA on the outcome of patients with NSCLC being treated with curative intent CRT is a poorly studied topic. Previous work in other cancers demonstrated deviation from the original radiation treatment plan is associated with worse prognosis. For example, prolongation of treatment time during RT is associated with worse local control in NSCLC, cervical, anal, and head and neck cancers.14,15 To account for the impact of RT treatment time on outcomes, we included elapsed days of RT in our multivariate models. In these models, MCA continued to be an independent predictor for worse OS, PFS, and earlier distant metastasis when accounting for RT treatment times demonstrating its clear impact on patient outcome.

In a study by Cox et al,8 interruptions delaying completion of planned RT were more frequent in patients receiving higher total radiation doses (≥ 69.6 Gy) due to acute treatment reactions and poor tolerance by patients.4-7,16-19 The effects of higher doses of RT were also recently demonstrated with the results from Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 0617, which showed decrements in OS in patients treated with higher RT doses.8 One hypothesis in the context of these findings suggest that treatment with standard doses of RT may reduce the risk of toxicity and result in avoidance of both RT and chemotherapy interruptions, possibly resulting in better treatment outcomes.

Chemotherapy dose reductions were also associated with worse OS (9.8 mo compared with 24.3 mo in patients who did not experience dose reductions; P = 0.0007), meaning dose reduction is not a viable alternative to holding chemotherapy. This finding is consistent with the knowledge of chemotherapy in breast cancer.20 This further underlines the importance of optimizing delivery of both chemotherapy and RT. In this context, targeted radiotherapy to the tumor volume and sparing other thoracic organs, such as the esophagus and bone marrow, becomes important to improve the toxicity profile and tolerability of chemotherapy and RT as high doses to these structures can cause esophagitis and hematologic toxicity resulting in missed chemotherapy.21-23 In addition, optimizing nutritional status is associated with better survival in NSCLC patients and may improve treatment compliance.24 Finally, careful consideration of chemotherapy regimen should be considered after taking patient status into account. Although treatment with cisplatin/etoposide versus carboplatin/taxol does not differ in survival, cisplatin/etoposide is associated with high rates of morbidity.25

CONCLUSIONS

MCA during CRT frequently occur in NSCLC patients receiving CRT and are associated with poor prognosis and OS. Efforts to minimize treatment toxicity with more targeted radiation planning to organs at risk may aid in delivery of all planned doses of chemotherapy and may improve OS in unresectable NSCLC treated with CRT.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Furuse K, Fukuoka M, Kawahara M, et al. Phase III study of concurrent versus sequential thoracic radiotherapy in combination with mitomycin, vindesine, and cisplatin in unresectable stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2692–2699. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fournel P, Robinet G, Thomas P, et al. Randomized phase III trial of sequential chemoradiotherapy compared with concurrent chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Groupe Lyon-Saint-Etienne d’Oncologie Thoracique-Groupe Francais de Pneumo-Cancerologie NPC 95-01 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5910–5917. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curran WJ, Jr, Paulus R, Langer CJ, et al. Sequential vs. concurrent chemoradiation for stage III non-small cell lung cancer: randomized phase III trial RTOG 9410. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1452–1460. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishimura Y, Nagata Y, Okajima K, et al. Radiation therapy for T1,2 glottic carcinoma: impact of overall treatment time on local control. Radiother Oncol. 1996;40:225–232. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(96)01796-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bese NS, Hendry J, Jeremic B. Effects of prolongation of overall treatment time due to unplanned interruptions during radiotherapy of different tumor sites and practical methods for compensation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:654–661. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fyles A, Keane TJ, Barton M, et al. The effect of treatment duration in the local control of cervix cancer. Radiother Oncol. 1992;25:273–279. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(92)90247-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen M, Jiang GL, Fu XL, et al. The impact of overall treatment time on outcomes in radiation therapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2000;28:11–19. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(99)00113-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox JD, Pajak TF, Asbell S, et al. Interruptions of high-dose radiation therapy decrease long-term survival of favorable patients with unresectable non-small cell carcinoma of the lung: analysis of 1244 cases from 3 Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;27:493–498. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(93)90371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsumoto I, Tanaka M, Shirakawa S, et al. Postoperative serum albumin level is a marker of incomplete adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;22:2408–2415. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4280-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belani CP, Choy H, Bonomi P, et al. Combined chemoradiotherapy regimens of paclitaxel and carboplatin for locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized phase II locally advanced multi-modality protocol. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5883–5891. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.55.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parlak C, Mertsoylu H, Guler OC, et al. Definitive chemoradiation therapy following surgical resection or radiosurgery plus whole-brain radiation therapy in non-small cell lung cancer patients with synchronous solitary brain metastasis: a curative approach. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88:885–891. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strom HH, Bremnes RM, Sundstrom SH, et al. Concurrent palliative chemoradiation leads to survival and quality of life benefits in poor prognosis stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised trial by the Norwegian Lung Cancer Study Group. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:1467–1475. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lababede O, Meziane MA, Rice TW. TNM staging of lung cancer: a quick reference chart. Chest. 1999;115:233–235. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.1.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simpson JR, Francis ME, Perez-Tamayo R, et al. Palliative radiotherapy for inoperable carcinoma of the lung: final report of a RTOG multi-institutional trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1985;11:751–758. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(85)90307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tas F, Sen F, Odabas H, et al. Performance status of patients is the major prognostic factor at all stages of pancreatic cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2013;18:839–846. doi: 10.1007/s10147-012-0474-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lanciano RM, Pajak TF, Martz K, et al. The influence of treatment time on outcome for squamous cell cancer of the uterine cervix treated with radiation: a patterns-of-care study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;25:391–397. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(93)90058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ben-Josef E, Moughan J, Ajani JA, et al. Impact of overall treatment time on survival and local control in patients with anal cancer: a pooled data analysis of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group trials 87-04 and 98-11. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:5061–5066. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koukourakis M, Hlouverakis G, Kosma L, et al. The impact of overall treatment time on the results of radiotherapy for nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;34:315–322. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)02102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeremic B, Shibamoto Y, Milicic B, et al. Impact of treatment interruptions due to toxicity on outcome of patients with early stage (I/II) non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with hyperfractionated radiation therapy alone. Lung Cancer. 2003;40:317–323. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradley JD, Paulus R, Komaki R, et al. Standard-dose versus high-dose conformal radiotherapy with concurrent and consolidation carboplatin plus paclitaxel with or without cetuximab for patients with stage IIIA or IIIB non-small-cell lung cancer (RTOG 0617): a randomised, two-by-two factorial phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:187–199. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71207-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shayne M, Crawford J, Dale DC, et al. Predictors of reduced dose intensity in patients with early-stage breast cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;100:255–262. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9254-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muss HB, Woolf S, Berry D, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in older and younger women with lymph node-positive breast cancer. JAMA. 2005;293:1073–1081. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.9.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deek MP, Benenati B, Kim S, et al. Thoracic vertebral body irradiation contributes to acute hematologic toxicity during chemoradiation therapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;94:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kovarik M, Hronek M, Zadak Z. Clinically relevant determinants of body composition, function and nutritional status as mortality predictors in lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer. 2014;84:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santana-Davila R, Devisetty K, Szabo A, et al. Cisplatin and etoposide versus carboplatin and paclitaxel with concurrent radiotherapy for stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: an analysis of Veterans Health Administration data. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:567–574. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]