Abstract

Aims and objectives

To explore family perspectives on their involvement in the timely detection of changes in their relatives' health in UK nursing homes.

Background

Increasingly, policy attention is being paid to the need to reduce hospitalisations for conditions that, if detected and treated in time, could be managed in the community. We know that family continue to be involved in the care of their family members once they have moved into a nursing home. Little is known, however, about family involvement in the timely detection of changes in health in nursing home residents.

Design

Qualitative exploratory study with thematic analysis.

Methods

A purposive sampling strategy was applied. Fourteen semi‐structured one‐to‐one interviews with family members of people living in 13 different UK nursing homes. Data were collected from November 2015–March 2016.

Results

Families were involved in the timely detection of changes in health in three key ways: noticing signs of changes in health, informing care staff about what they noticed and educating care staff about their family members' changes in health. Families suggested they could be supported to detect timely changes in health by developing effective working practices with care staff.

Conclusion

Families can provide a special contribution to the process of timely detection in nursing homes. Their involvement needs to be negotiated, better supported, as well as given more legitimacy and structure within the nursing home.

Relevance to clinical practice

Families could provide much needed support to nursing home nurses, care assistants and managers in timely detection of changes in health. This may be achieved through communication about their preferred involvement on a case‐by‐case basis as well as providing appropriate support or services.

Keywords: acute care, aged care, chronic illness, elder care, family, hospital, nursing homes, older people, qualitative study

What does this paper contribute to the wider global clinical community?

Draws attention to the importance of supporting family involvement in nursing homes.

Demonstrates how family members are involved in nursing homes to support timely detection of changes in health, with potential to support the reduction of avoidable hospital admission from these settings.

1. INTRODUCTION

Reducing avoidable hospitalisations is an international issue. In the United States, Centres for Medicare and Medicare Services began in 2012 to implement an ongoing initiative to reduce avoidable hospitalisations across the country (CMS.gov Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services, 2016). The UK has been no exception, and reducing avoidable hospitalisations is a key priority within the National Health Service (NHS). A key outcome measure in the NHS Outcomes Framework (2016–2017) includes “Emergency admissions for acute conditions that should not usually require hospital admission” (National Health Service, 2016). In the UK, avoidable emergency hospital admissions increased 40% from 2001–2011 (Bardsley, Blunt, Davies, & Dixon, 2013).

As care homes in the UK have an increasingly ageing population (Office National Statistics, 2014), avoidable hospital admissions from these settings are receiving more attention (Care Quality Commission, 2014). Moreover, in an analysis of hospitalisations between April 2011–March 2012 across small geographical areas, Smith, Sherlaw‐Johnson, Ariti, and Barsley (2015) found that emergency hospital admissions for over 75s are higher in areas with more care home residents than those without, at 79.7% compared to 46.3%, respectively.

In 2012, one of six emergency hospital admissions in the UK was for ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSCs) (Tian, Dixon, & Gao, 2012). ACSCs are conditions where hospitalisation could be avoided through the provision of primary care (Purdy, Griffin, Salisbury, & Sharp, 2009). Those aged over 75 are particularly at risk of avoidable emergency hospital admissions for ACSCs (Tian et al., 2012). It has been demonstrated in the United States that timely detection of changes in health may help to reduce avoidable hospital admissions from nursing homes (Ouslander et al., 2011).

Alongside reducing avoidable hospital admissions, there has also been a policy imperative in the NHS towards the inclusion of patients in their own care, as well as their family members (National Health Service England, 2013). A significant body of research has called for effective partnership between care home staff and family members (Bauer, 2012; Bauer & Nay, 2011; Gaugler, 2005; Haesler, Bauer, & Nay, 2010; Hertzberg & Ekman, 2000; Nguyen, Pachana, Beattie, Fielding, & Ramis, 2015). However, family members'1 involvement in timely detection of changes in health in UK nursing homes has not received attention. UK “nursing homes” are care homes with registered nurses' onsite.

2. BACKGROUND

2.1. Health and avoidable admissions

Nursing home residents have complex health conditions. Approximately 280,000 people living in UK care homes have dementia (Alzheimer's Society, 2016). Reducing unnecessary deterioration of health conditions that can lead to hospitalisation is crucial. Hospitals can be distressing environments and can lead to iatrogenic conditions. There are also significant cost implications for the NHS (Bardsley et al., 2013).

Changes in ACS conditions can be detected and effectively managed before there is further deterioration in health (Ouslander et al., 2011). We use the term “timely” detection in this study to emphasise that health changes can be detected rapidly enough to prevent unnecessary hospitalisation. “Timely” can be distinguished from “early” detection. “Timeliness” signifies that the change was identified at the right opportunity as opposed to a fixed chronological time (Dhedhi, Swinglehurst, & Russell, 2014). Best practice guidelines have been developed about how to reduce avoidable hospital admissions for common chronic ACS conditions. Despite these guidelines, rates have increased in recent years, particularly for those aged over 80; 20% of emergency admission to hospital in the UK has been for ACS conditions (Bardsley et al., 2013).

2.2. Interventions to improve health and reduce avoidable admissions

Interventions to reduce the rate of avoidable hospitalisations from nursing homes are few and have not had particularly strong evidence. In a review, Graverholt, Forsetlund, and Jamtvedt (2014) found 11 such interventions, all of which were tested only once. However, despite the low quality of evidence, the results indicated several key ways in which avoidable hospital admission could be reduced. The interventions included “structure and standardising treatment,” “geriatric specialist services” and “influenza vaccination.” Morphet, Innes, Griffiths, Crawford, and Williams (2015) found that improving primary care services could lower the number of residents being admitted to emergency departments. In a study of three nursing homes that had the highest hospital admissions to a trust, it was discovered that emergency admissions reduced where there was regular contact with consultant geriatricians. Residents were also found to spend less time in hospital (Lisk et al., 2012).

Ouslander et al. (2011) “Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers” (INTERACT) produced a range of tools and approaches to reduce unnecessary hospitalisations. Some of the tools included an early warning tool (Stop and Watch), a card to assist nursing staff to identify changes in health, and care paths for conditions including urinary tract infection, congestive heart failure and dehydration. There were also “facility champions” to ensure the education of staff and implementation of INTERACT. The program was tested in 25 nursing homes over a 6‐month period and showed a 17% reduction in hospitalisations.

Young, Inamdar, Dichter, Kilburn, and Hannan (2011) has also shown that requests from family members that their relatives should be treated in hospital can increase the number of hospitalisations. Education for both family members and nursing staff has been suggested. How family members might be involved in other ways to reduce unnecessary hospitalisations needs further exploration.

2.3. Family involvement in timely detection of changes in health

To our knowledge, there is a lack of evidence about family member involvement in timely detection of changes in health. Mentes, Teer, and Cadogan (2004) highlights that family members are involved in detection of pain in their relatives with dementia, and may do so through being aware of the residents' normal habits and behaviour. Family members have knowledge themselves about changes in health of their relatives in NHS (Armitage et al., 2009) and hospital settings (Fry, Chenoweth, Macgregor, & Arendts, 2015). This is further supported by recent work involving people with dementia which has demonstrated that family members, who know the person well, may be able to support diagnosis of ill‐health, especially for people living with dementia in care homes (Scrutton & Brancati, 2016).

Bowers, Roberts, Nolet, and Ryther (2015) carried out a study to understand differing care processes across Green House nursing homes. The Green House model is an approach to cultural change in nursing homes. They have between 8–12 residents. The homes are staffed by nursing assistants named “Shahbazium” that provide care and manage the home, as opposed to registered or licensed nurses. Bowers et al. (2015) found one reason for lower hospital admissions in some Green House nursing homes was in part due to family members becoming involved in communicating with primary care physicians about their relative's changes in health. This communication was made possible as physicians made themselves more available.

2.4. How are family involved in care homes?

We know that family continue to be involved in the care of their relatives who have moved into a nursing home (Bauer, 2012; Bowers, 1988; Duncan & Morgan, 1994, Graneheim, Johansson, & Lindgren, 2014; Milligan, 2012) . Family members provide information about their relatives like and dislikes and life history to care staff (Bramble, Moyle, & McAllister, 2009; Davies & Nolan, 2006). Some health and care staff have been shown to appreciate receiving this information about the unique needs of the resident (Fry et al., 2015; O'Shea, Weathers, & McCarthy, 2014).

Several studies have identified that family members are involved in monitoring their relatives' care (Bowers, 1988; Mullin, Simpson, & Froggatt, 2011; Silin, 2001). Monitoring involves evaluating care provision by staff, working with care staff to ensure care quality (Bowers, 1988) and family members noticing when their family member is not being best cared for by staff (Silin, 2001).

Family members are involved in advocating on behalf of their relatives (Mullin et al., 2011) to improve the care provided to their family member (O'Shea et al., 2014). They are more likely to be advocates than staff members because they have knowledge of their relative before they moved into a nursing home (Gaugler & Kane, 2007). The Mental Capacity Act (2005) stipulates that it should be assumed that all persons have capacity to make decisions. However, family members can be involved in supporting their relative to make decisions. For example, a family member may be become a personal consultee, making decisions in the best interests of the person.

Family members can provide social support, such as visiting relatives, and emotional support, such as providing company for their relatives in nursing homes. Whatever work the family member does, it demonstrates to the resident that they care about them (Milligan, 2012). Residents that do not have frequent family contact can feel isolated (Goodman et al., 2013). Family can become involved in “preservative care” where family members maintain the residents' identity and dignity (Bowers, 1988).

Relatives are also involved in providing personal care. In a US study of 438 care home residents in 125 different residential, nursing and assisted living facilities, Williams, Zimmerman, and Williams (2012) found that 50% of family members assisted with meals and 40% assisted with personal tasks. It is also important to note that family members can see these physical tasks as the responsibility of formally employed care staff (Baumbusch & Phinney, 2014).

2.5. Supporting family involvement in care homes

Families are increasingly seen as partners in care in care homes (Gaugler, 2005; Nolan, 2001). To this end, a number of studies internationally have considered how to improve relationships between staff and family (Bauer, 2012; Bauer & Nay, 2011; Gaugler, 2005; Haesler et al., 2010; Hertzberg & Ekman, 2000; Nguyen et al., 2015).

Haesler et al. (2010, 47–61) conducted a systematic review of relationships between family and staff. Their results were mainly based on 41 qualitative studies as they identified there is a lack of evidence from high‐quality quantitative research in this area (only five were identified). Several ways in which positive relationships could be created and maintained were identified:

“the resident is unique” in which staff learn about unique personal information of the resident from family

“information is important” where relationships can be improved through information provided about the care home, their relatives care and health

“familiarity, trust, respect and empathy” between family and staff

“family characteristics and dynamics” where the personalities and individual characteristics of family members can have an impact on relationships

“collaboration and control” in which relationships can hinge on practicalities and the feeling of who knows best

“communication skills” in which for example staff consider the language they use, and there is greater recognition between staff and family

“organisational barriers” in which staff need to be supported through effective workload models to become involved in care with family members

Interventions have been implemented to improve these relationships, some with positive results, although more evidence is required (Haesler et al., 2010).

Several studies have tested a range of approaches to ensure effective family involvement. Yet despite the policy imperative of reducing avoidable hospital admissions, little is known about families' involvement in the timely detection of changes in health in nursing home residents, and how family members could be better supported within this process. There is now a compelling argument to more fully understand family members' involvement in the timely detection of their relative's health changes and what can be done to support it within a nursing home context.

2.6. Aim

To explore family members' perspectives on their involvement in timely detection of their family members' changes in health in UK nursing homes.

2.7. Research questions

How are family involved in timely detection of changes in health in nursing homes?

How can family be supported to engage in timely detection of their family members' changes in health?

3. METHODS

3.1. Ethical approval and funding

This study is independent research funded by a National Institute for Health Research Programme Grant for Applied Research “Reducing rates of avoidable hospital admissions: Optimising an evidence‐based intervention to improve care for ACSCs in nursing homes” (RP‐PG‐0612‐20010). This study received ethical approval from a university ethics committee. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health.

3.2. Design

An interpretivist paradigm was adopted to understand individuals' constructs and perceptions (Mason, 2002). This was an exploratory qualitative study using semi‐structured interviews, which was subject to thematic analysis. A qualitative exploratory study was deemed appropriate as we identified from the literature that little was known about family members' involvement in timely detection of health changes in the UK. Qualitative methods can be applied to shed light on the experiences and gain in depth data to understand individual perceptions and meanings (Mason, 2002).

3.3. Recruitment

Our review indicated the importance of gaining the family members perspective of their own experiences in care homes, as opposed to relying on care staffs understanding of family involvement (Bowers, 1988; Gaugler, 2005). Thus, we applied a sampling strategy that would enable us to access family views specifically. A purposive sampling strategy with criterion sampling was applied to recruit individuals who had current or very recent experience of their family members living in a nursing home. Criterion sampling involves deliberately selecting participants based on key criteria (Bryman, 2016). Our inclusion criteria were defined prior to sampling. All should have been family members of residents aged over 65. Moreover, to learn about recent experiences, all residents must have been living in the nursing home currently or been living there within the last 5 years. Advice was sought from two Carer Reference Panels on how best to recruit family members. The group consisted of members of the public who were family members of people with dementia, or had dementia themselves, had a family member living in a care home (with or without nursing) either currently or in the past, or had spent time in a care home themselves. Family members included spouses, partners and parents. These were the requirements of becoming a panel member. The Carer Reference Panels also assisted with the development of the poster and leaflet recruitment materials.

We used two recruitment methods, contacting nursing homes, and contacting online forums, newsletters and websites. In the first instance, the lead author contacted managers of nursing homes, primarily in the local area, by phone and email. The lead author met with seven nursing home managers who agreed to distribute the leaflets to family members via post, email, face‐to‐face on a one‐to‐one basis and at a resident meeting. Posters were also displayed in the nursing homes to raise awareness of the study. An additional 21 nursing home managers, whom the lead author contacted via phone, were sent posters and leaflets about the study to advertise to family members. Nine family members were recruited through contacting nursing homes. Our second method involved advertising the study to family members through relevant online forums, newsletters and websites. All these media were aimed at family members of people with health problems. Approval was gained from the providers to place an advert for the study. Interested potential participants were encouraged to respond to the advert anonymously. Five family members were recruited though this method.

3.4. Consent

Each family member received an information sheet with the aims, methods, anticipated benefits and potential risks of the study. Family members that were recruited through care homes received their information sheets from the care home managers. Potential participants made contact with the researcher through phone or email to discuss the study. If they were eligible to take part, they were given an information sheet. Those who were recruited through other means were given an information sheet when they contacted and discussed the study with the researcher. It was made clear to family members in the information sheet and consent form that they were under no obligation to participate in the study, and that they could withdraw at any time during the study, without having to give a reason. Family members were given a minimum of 24 hr to decide whether or not they wished to participate. They were given a consent form to sign and return to the researcher.

3.5. Data collection

A semi‐structured interview schedule was created based around key areas under investigation. The Carer Reference Panels also reviewed the interview schedule. The semi‐structured interviews were conducted by the lead author. Each interview lasted between 30 min–1 hr 30 min. Thirteen interviews were carried out by phone and audio recorded. Telephone interviews were employed to enable us to recruit participants from greater geographical distances across the UK within our resource constraints. Interviews by telephone have been demonstrated to be effective in qualitative research. Whilst there are no visual cues, it is possible to hear nonvisual paralinguistic cues such as sighs (Ward, Gott, & Hoare, 2015). One interviewee preferred to be interviewed face‐to‐face at the university. This face‐to‐face interview was also audio recorded. Pseudonyms were given to each of the interviewees.

3.6. Data analysis

Thematic analysis of the data was applied. Thematic analysis is suitable for gaining rich detail about phenomena (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This involved several steps. First, the recorded interviews were transcribed. Second, familiarisation was carried out by the lead author and two co‐authors. Familiarisation involves the identification and recording of initial themes from reading the interview data (Spencer, Ritchie, O'Connor, Morrell, & Ormston, 2014). Initial themes about family members' involvement in timely detection of changes in health in nursing homes were recorded. Third, following the creation of these themes, the lead author and a co‐author developed a thematic framework. The framework was compiled through searching for relationships between the themes. A hierarchy of themes and subthemes were created. Fourth, indexing was applied by the lead author across the data set creating the key findings of the study. Indexing indicates where in the data the themes and subthemes are (Spencer et al., 2014). QSR International's nvivo version 10 (2012) Software was used throughout the data analysis process. To ensure the trustworthiness of our findings, we employed Lincoln and Guba's (1985) approach of establishing “transferability” of our data. The Carer Reference Panels commented on the relevance of our findings as themes emerged.

4. RESULTS

Fourteen family members were recruited to the study, with connections to 13 different nursing homes. All the family members were adult children of the residents; 12 were female and two were male. The family members were all white British. All but one visited their family member at least once a week. One person visited approximately once a fortnight. The length of time residents had lived in a nursing home ranged from 2 weeks–7 years. The mean length of time was 26.9 months, and the standard deviation was 21.0.

All 14 family members were involved in the process of timely detection of their relatives' changes in health in nursing homes. The following section reports the ways in which they were involved. We then turn to family member views of how working practices between family and staff could support their involvement in the process of timely detection of changes in health.

4.1. How family members are involved in the process of timely detection of changes in health

There were three key ways in which family members were involved in timely detection. First, they noticed timely signs of changes in health. Second, family members informed staff about the timely signs of changes in health. Third, they educated staff about their family member. Whilst family members noticed timely signs of changes in health, they did not always communicate this information to care staff through informing or educating them.

4.1.1. Noticing signs of changes in health

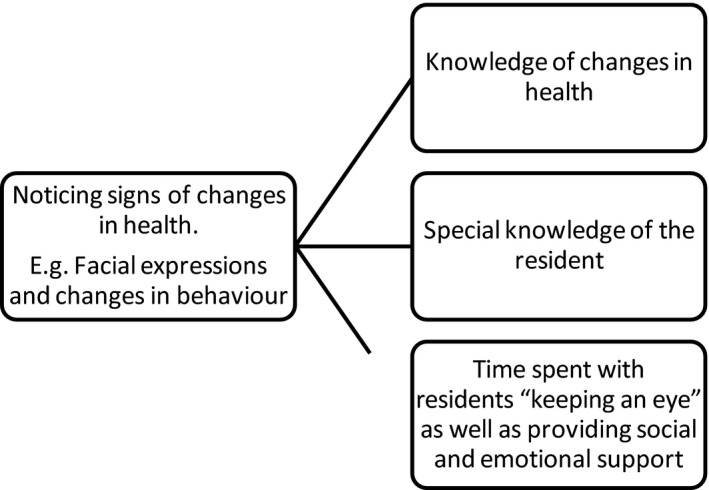

The following describes the signs of changes in health that family members noticed; facial expressions and changes in behaviour. It then goes on to explore how family members were able to detect changes in health. They were able to do so through having; knowledge of changes in health, special knowledge of the resident and time spent “keeping an eye on” family as well as providing social and emotional support. Figure 1 indicates how family members were able to notice signs of changes in health.

Figure 1.

How family members notice signs of changes in health

Family members described the subtlety of the signs of changes in health through particular expressions, such as, “things that I think are not quite right” (Rachel), and “very small changes” (Rachel). Facial expressions were often taken as a sign that residents were becoming unwell. For example, Stacey noticed her mother's knee “was bothering her” as she was “grimacing.” Family members mentioned how they could on occasions tell which health condition was affecting their relative from the ways that family members reacted. In the following extract, Carol describes how she noticed her father, who had dementia, was not behaving in the way he usually would. This alerted her to the possibility that he may be becoming unwell:

me and my sister went to visit on a Sunday and just thought he just didn't seem quite right…although he's got dementia, the person that he is now, he's still, he's quite cheeky and he's got this little sparkle about him…he'll have a giggle at you even though he might not necessarily understand what's happening…and he just seemed very flat. (Carol)

Family members were more able to notice signs of changes in health when they had knowledge of changes in health. They could overlook these signs without this knowledge. Barbara mistook signs of changes in health (swollen ankles) as signs of growing older:

I thought that might be just something that happened to old people, ‘cause there were a few people in the home with swollen feet and ankles. (Barbara)

Having special knowledge of the resident also enabled family members to notice signs of changes in health. There was a sense that by being a family member, you have “insider” family knowledge to notice these subtle signs. As Lucy mentioned, “you notice change, don't you with, especially with family” (Lucy). Rachel felt “I think it's about me being able to see what my mum's potential is greater than [the care staff]” (Rachel). Thus, many family members felt they knew what “normal” health for their relative looked like. This is also reflected in the earlier quote from Carol, who knew her father well enough to know that he had a change in behaviour. What is more, she was able to distinguish this change from his dementia.

Time spent with residents also had implications for whether family members noticed changes in health. Whilst almost all interviewees visited at least once a week, some described how other family members visited less regularly, particularly when they lived at a distance. Rachel, who visited once a week, highlighted that whilst she was able to notice small health changes, her brother, who visited every 6 weeks, “sees the changes that I don't see… I don't notice the gradual change quite so much” (Rachel).

The purpose of family member visits could be to “keep an eye on” their relative, or involve providing social and emotional support. These motivations led to family members, spending time with their relatives in a way which they felt care staff would often not have time for. For example, family members were often involved in engaging their relatives in social activities, such as reading or day trips. This provided an opportunity to become aware of signs of health changes. In the following extract, Heather highlights how she was able to notice changes in eyesight through spending time with her mother looking at photographs:

her eyesight, that I really only notice because I've sat with her and shown her things and photographs and….I suppose I did [notice before the carers and the nurse] because…very rarely does anybody sit with her and look at photographs or anything like that….they're understaffed and…[the carers] time is taken up with personal care… her eyesight isn't something that I came with knowledge of. It's something that I observed in the process of being with her. (Heather)

4.1.2. Informing care staff about the signs they noticed

A key part of family members' involvement in the process of detecting signs of changes in health involved informing staff about the signs that they noticed. In particular, family were able to tell staff when they felt something was not right with their relative.

Family members were not always able to distinguish between members of care staff. They informed different members of care staff about what they noticed. Some family members described how they would tell a nurse rather than care assistant about signs of health change, although they felt that the care assistants should be noticing signs of health themselves. Others would seek out a particular care assistant. Some were more likely to seek out the GP.

The following two extracts highlight how both Carol and Claire informed nurses about what they noticed:

He just seemed very flat and I asked one of the nurses, I said…has he been alright, ‘cause we hadn’t been in for a couple of days, dad seems a little bit distant. (Carol)

[Mum] was a bit sniffy and I said to one of the nurses…I think she's got a cold and they said yes…a few days later she started coughing… I remember thinking, hang on, she's coughing. She wasn't coughing when I saw her a couple of days ago…is she developing a chest infection? So I mentioned it to one of the nursing staff…The GP (general practitioner), he saw her that weekend, started her on antibiotics straightaway…but that kind of happened because I mentioned it. (Claire)

However, some family members avoided communication about their relatives with staff. By “speaking up” family members feared that they would appear to be accusing staff of not doing their job adequately, as Stacey commented, “it's kind of pointing a finger at a member of staff” and Rachel mentioned “it feels as though I'm interrupting.”

4.1.3. Educating care staff about their family member

In addition to informing care staff when they noticed changes in health, some family members' involvement comprised educating care staff about these health changes. Thus, staff could apply this knowledge to notice changes in health when the family member was not present. The following interview extracts indicate how family members could contribute to the training that care staff receives:

they learn about…her health because if I pick something up then I tell them and I have long discussions with the…nurse manager…not long discussions but… over the 18 months…and they think I'm a bit of a pain obviously. (Rachel)

you notice change don't you… if we sort of keep advising them that this is what [happens]…they'd be able to pick up on it quicker, wouldn't they. (Lucy)

Family members also provided a history of the health of their relatives. This included information about life style choices, such as whether they had smoked. They could also inform staff about their relatives' personality. By providing the care home with this information, family members felt staff may themselves be more able to work out additional signs (that family members could be unaware of) and better understand what changes in health residents may be at risk of.

4.2. Effective working practices to support family members' timely detection of changes in health

Whilst family members were involved in the process of timely detection, they also felt there could be better working practices to facilitate their involvement. This could be through legitimising family involvement in timely detection of changes in health or providing opportunities to communicate health changes with staff. The section explores family members' perspectives of how these working practices might be achieved.

4.2.1. Legitimising family involvement in timely detection of changes in health

Family involvement could be legitimised through the introduction of a formal mechanism in the nursing home which invites their involvement, as well as through providing family information about common changes in health. However, family members had different preferences as to how and whether they would like to be involved in timely detection of changes in health. Some felt “it's up to the care staff to…identify changes” (Sarah) rather than relatives. This could be for practical reasons, such as frequency of family member visitation, or because they felt it was the responsibility of the staff working in the care home as they are paid to care for residents. Some were involved despite feeling it was not their responsibility, filling in what they saw as gaps in their family members health care, whilst others wanted to be involved as they felt they had some responsibility.

Furthermore, some family members felt that the care staff did not see them as legitimate contributors to the process of timely detection of changes in health. They felt they were not listened to by staff members. Relatives sought “good” relationships with care staff. This motivation for a good relationship could have an impact on whether family members communicated with staff. Consequently, they were unsure and fearful about whether they should be involved in the process, and did not always communicate the changes they noticed to staff as a result.

Carol highlights that a “formal mechanism” could make family members feel able to contribute:

there isn't any, any formal mechanism for…asking me if I've noticed anything…Which makes any comments that I make…they need to be couched so that they can't be perceived as criticism…Which is why [family members] don't mention anything at all. They just grumble to me. (Carol)

The “mechanism,” however, should enable family members to choose how and whether they would like to be involved. Carol suggested improving communication of changes in health noticed by family members through “in‐invit[ing] a contribution in a sense rather than give me responsibility.”

It became clear that family members desired information from care staff about how changes in health commonly present so that they would be better placed to notice signs of changes in health in their family member. Carol describes how by doing so, the staff member would make the family member feel that timely detection was part of their responsibility:

the knowledge that dehydration is a problem and UTIs are a problem, that's sort of trickled through to me gradually. Nobody's actually given me that information…if somebody had said, ‘Look, these are common things that happen to old people and these are some of the signs, and if you see any of these…please speak to us,’ because the more people who are…keeping an eye… It would be hard for them to do it probably without somebody coming and saying, ‘That's your job’. (Carol)

4.2.2. Opportunities to communicate health changes with staff

Family members needed to have the opportunity to communicate health changes. Such opportunities could be increased through ensuring the right person to speak to is available, changing the physical layout of the care home, having appropriate tools to facilitate communication and having ongoing communication with family members beyond the admission process.

Finding the “right person” to speak to was a key way in which information about signs of health changes could be shared in a timely manner. As mentioned, sometimes this was felt to be the nurse, other times the GP and in some cases a particular care assistant.

Having the opportunity to communicate with the GP responsible for their family member was also an issue. There were several reasons why family members felt this was not always possible. First, the nursing home did not inform family members when the GP was visiting the nursing home. Second, many family members were not available when the GP visited the nursing home, and third family members felt the GPs were disinterested in speaking to relatives. In the following, Barbara highlights why she believed the GP had no time for her or other family members:

GPs get a fee for doing these nursing homes…and they want to do it in the shortest possible time…[speaking to family members] holds them up and they make it very obvious it holds them up. (Barbara)

The layout and size of the nursing home could also have implications for being able to speak to the right members of staff. Heather found it “very hit and miss” as to whether she could find staff members because of the layout of the nursing home. As she says:

the building is large…there are two floors to it…there are only 5 residents [on my dad's floor] … quite often I find that there is no‐one around… I will have already gone through password key locked double doors, so it is not as though I can just pop out and find someone…their argument is that at no point should there be more staff on while they have so few people downstairs. (Heather)

By contrast, Heather had more positive experiences in past nursing homes where there was more visibility and integration between residents, family members and care staff, where “the office was part of the…living room.”

Family members described the importance of being consulted about residents on an ongoing basis rather than only when they first moved into the care home. For example, Claire found that she needed to be prompted for information about the residents' history when it was relevant.

Well he's never had an illness as such that you would give them, he's never had problems with his breathing or he's never had problems with his heart. There's no family history as such…When they're thinking about things to do with his breathing, yeah there's that information that we haven't told them just because we haven't really considered it…It's 20 years ago…but I guess you'd only really think of it if a situation prompted it…If they hadn't have mentioned his oxygen levels yesterday, I would have never thought to say ‘oh well he used to smoke’…Unless you're prompted, you could just write pages and pages and pages and pages of everything that you've ever done, couldn't you? (Claire)

Thus, family members were involved in the process of timely detection; however, effective working practices were needed to support this.

5. DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore family members' involvement in the timely detection of changes in health of residents in UK nursing homes. We have highlighted ways family members are involved and how they can be supported to engage in timely detection of their relatives' changes in health.

Participants were involved in three key ways. First, family members noticed signs of changes in health through having knowledge of changes in health, special knowledge of their relative and spending time with them, particularly during nonpersonal care tasks. Second, family members informed care staff about the signs of changes in health, although they were not always clear about who they had communicated the information to. Third, family members educated care staff about how the signs of changes in health present in their family member, and provided history of their health. Thus, the results begin with an exploration of how family members realise the changes in health in their relatives for themselves, and following this, the results show that relatives communicate information with staff to support timely detection of health changes (through informing and educating care staff).

Whilst family members were involved in timely detection of changes in health, they felt they could be more effectively included in the process through improved working practices. Not all participants felt that they should become involved in timely detection, and some were not always able to do so. Legitimising family involvement in timely detection is one potential way of supporting those who wish to contribute. A second working practice involved ensuring there were opportunities to communicate health changes with staff. The findings suggest a requirement for formalising family involvement. They indicate a need for change in practice in nursing homes, through care staff regarding family members as integral to the timely detection process and the nursing home, where relatives are willing and able to contribute.

Our findings resonate with research into family member involvement in care homes to facilitate a more personalised form of care (Bowers, 1988; Bramble et al., 2009). Research has shown that family members monitor their relatives and their care (Baumbusch & Phinney, 2014; Bowers, 1988; Mullin et al., 2011; Silin, 2001). Staff might not have enough knowledge about their family member without their input. Thus, family members are in an important position to contribute to timely detection of changes in health.

On the other hand, family members' special ability to notice changes in health needs support from the nursing home. Communication is central to this. Clarifying responsibilities by having written information about the ways that families are involved (Hertzberg & Ekman, 2000); staff and family listening to one another, and family members providing feedback in a positive way (Bowers et al., 2015; Haesler et al., 2010; Hertzberg & Ekman, 2000) can improve staff and family relationships (O'Shea et al., 2014). Close relationships have been found to make staff feel more able to speak to family members about difficult subjects (Bowers et al., 2015). Care staff themselves can face difficulties communicating changes in pain in residents to other staff members for similar reasons identified in this study. For example, feeling valued, and having positive relationships between staff members, has improved the comprehensiveness of pain reports (Jansen et al., 2017). Our findings indicate that staff working with families to clarify involvement preferences may support family members themselves being involved in timely detection of health changes. This builds on research by Davies and Nolan (2006), which suggests that discussion could enable family to be taught about changes in health need of their relatives. Establishing clarity on involvement between family members and staff may create the legitimacy that family members need to become involved.

In addition, the physical structure of care homes could also open up opportunities for family members to become involved in timely detection of health changes. The Green House Study (Bowers et al., 2015) found that shared time and space in nursing homes could improve communication about health conditions.

There are some limitations with the study, particularly in terms of the sample. The sample was self‐selective. Respondents were more likely to be family members who had some type of involvement in the care home. All participants visited the nursing home at least once every 2 weeks. In addition, the sample comprised only adult children of care home residents. Baumbusch and Phinney (2014) found that spouses spend more time in the care home and carried out personal care tasks. Spouses and adult children may have different preferences for how they prefer to be involved in the detection of their family members' changes in health. It is also important to reflect on the lack of diversity amongst those who participated. All the interviewees were from a white British background, and contained only two males. Despite these limitations, this study has met its key aims of understanding family members' perspectives on how they are involved in timely detection of changes in health in nursing homes, as well as how they can be supported to engage in timely detection of their family members' changes in health.

This research has important implications for health care of care home residents in an international context. It demonstrates how family members are involved in timely detection of changes in health, and could potentially contribute to the reduction of avoidable hospitalisations, which is an international concern. However, it should be noted that this research has been carried out in UK nursing homes, where registered nurses are available on site. Therefore, the results may be different in care homes without registered nurses, or where there other types of staff member outside the UK context. There may be cultural differences in how family members become involved in health care (Parveen, Peltier, & Oyebode, 2017).

With regard to future research, there is a need for more robust testing to the extent to which family members' involvement in timely detection of health changes in nursing homes might improve the health of residents, and thereby reduce avoidable hospital admissions. This exploratory study has identified how family members perceive themselves to be involved in timely detection of health deterioration; however, it is not clear whether this timely detection leads to improvements in health in residents. Moreover, further research could focus on the accounts of residents and care staff in nursing home settings. Such perspectives could further elucidate how working practices between family members and staff might be improved to improve timely detection of changes in health. Fry et al. (2015), for example, identified in their research in hospital settings that emergency nurses can be receptive to family members providing them information about residents. Jansen et al. (2017) has shown that healthcare assistants are often the first to notice indications of pain. Seeking and acting on different family members' views could raise various challenges in practice that are not apparent from the family member accounts alone. There may be an additional layer of complexity to consider within the partnerships between staff, resident and family members, as relationships between multiple different family members can influence staff–family relationships (Haesler et al., 2010).

Following this study, family involvement in timely detection of health changes will be included in an intervention to improve timely detection of ACSCs in residents in nursing homes. This will involve a member of care staff formally establishing how family members would like to be involved in the intervention, recording preferences in each resident's care record, as well as explaining the purpose and application of an early warning and diagnostic tool.

6. CONCLUSION

Family members can be involved in timely detection of changes in health if they are provided with enough support from the nursing home. This study has shown that effective working practices need to be developed to support their involvement. Formalising and legitimising family involvement in timely detection of changes in health in nursing homes is critical. With this backing, family may have the potential to support the reduction of unnecessary hospital admissions.

7. RELEVANCE TO CLINICAL PRACTICE

There continues to be a gulf between research into effective partnerships and care practice. Research has clearly indicated that there needs to be an effective model of creating partnership between family members, residents and staff (Bauer & Nay, 2011; Gaugler, 2005; Haesler et al., 2010; Hertzberg & Ekman, 2000; Nguyen et al., 2015). However, as others have suggested (Baumbusch & Phinney, 2014), some family members continue to feel alienated from the nursing home in which their relatives live. This isolation may be having an impact on residents' health as family members are less able to share with staff members' information to support timely detection. This study has highlighted some suggestions from family members about how to bridge this gap.

Family members need to be included as partners that can shape the timely detection process. How relatives wish to be involved should be respected. This could be achieved through staff and family communicating with one another as part of an ongoing process, about how they might effectively be involved in timely detection, using appropriate supportive tools or services.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

We are not aware of any conflict of interests.

CONTRIBUTIONS

Data collection was carried out by CP. CP, AB and MD were involved in data analysis. CP, AB, KF, BMc, BW, JY, LR, MD contributed to the manuscript preparation and study design.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has only been possible due to the contribution of a large team of researchers and care professionals. These include Dr Liz Sampson, University College London; Dr Alex Feast, University College London; Shirley Nurock, Alzheimer's Research Network Volunteer; Dr Greta Rait, University College London; Caroline Baker, Barchester Health Care; Professor Clive Ballard, University of Exeter; Professor Heather Gage, University College London; Rachael Hunter, University College London; John Wood, University College London; Professor Finbarr Martin, Kings College London; Jenny Adams, University of Bradford; Professor Barbara Bowers, University of Wisconsin; Professor Lynn Chenoweth, University of New South Wales; Professor John Gladman, University of Nottingham; Professor Claire Goodman, University of Hertfordshire; Professor Martin Green, Care England; Professor Raymond Koopmans, UMC St Radbound University; Professor Julienne Meyer, My Home Life/City University London; Professor Des O'Neill, Trinity College Dublin; Professor Joseph Ouslander, Florida Atlantic University; Dr Hilary Rhoden, Public and Patient Involvement; Professor Graham Stokes, BUPA Care Services; Louise Taylor, Park Lodge Care Home; Gavin Terry, Alzheimer's Society; Stephen Williams, University of Bradford; Professor Jan Oyebode, University of Bradford; Dr Kathryn Lord, University of Bradford; the BHiRCH Carer Reference Panel members and the generous participation of care homes, care staff and families.

Powell C, Blighe A, Froggatt K, et al. Family involvement in timely detection of changes in health of nursing homes residents: A qualitative exploratory study. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27:317–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13906

Funding information

This study is independent research funded by a National Institute for Health Research Programme Grant for Applied Research “Reducing rates of avoidable hospital admissions: Optimising an evidence‐based intervention to improve care for Ambulatory Care Sensitive conditions in nursing homes” (RP‐PG‐0612‐20010). This study received ethical approval from the University of Bradford ethics committee. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health.

Note

“Family members” in this study includes relatives, close friends and care partners.

REFERENCES

- Alzheimer's Society (2016). Fix Dementia Care NHS and care homes. London: Alzheimer's Society. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, G. , Adams, J. , Newell, R. , Coates, D. , Ziegler, L. , & Hodgson, I. (2009). Caring for persons with Parkinson's disease in nursing homes: Perceptions of residents and their close family members, and an associated review of residents' care plans. Journal of Research in Nursing, 14, 333–348. [Google Scholar]

- Bardsley, M. , Blunt, I. , Davies, S. , & Dixon, J. (2013). Is secondary preventive care improving? Observational study of 10‐year trends in emergency admissions for conditions amenable to ambulatory care. British Medical Journal Open, 3, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, M. (2012). Relationships between patients, informal caregivers and health professionals in nursing homes. Evidence Based Nursing, 15, 28–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, M. , & Nay, R. (2011). Improving family‐staff relationships in assisted living facilities: The views of family. Journal Advanced Nursing, 67, 1232–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumbusch, J. , & Phinney, A. (2014). Invisible hands: The role of highly involved families in long‐term residential care. Journal of Family Nursing, 20, 73–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, B. J. (1988). Family perceptions of care in a nursing home. The Gerontologist, 28, 361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, B. , Roberts, T. , Nolet, K. , & Ryther, B. (2015). Inside the Green House “black box”: Opportunities for high‐quality clinical decision making. Health Services Research, 51, 378–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramble, M. , Moyle, W. , & McAllister, M. (2009). Seeking connection: Family care experiences following long‐term dementia care placement. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18, 3118–3125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods (5th ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Care Quality Commission (2014). Cracks in the Pathway: People's experiences of dementia care as they move between care homes and hospitals. London: Care Quality Commission. [Google Scholar]

- CMS.gov Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services (2016). Initiative to reduce avoidable hospitalizations among nursing facility residents. Baltimore, MD: CMS.gov Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services; Retrieved from https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/rahnfr/ [Google Scholar]

- Davies, S. , & Nolan, M. (2006). Making it better': Self‐perceived roles of family caregivers of older people living in nursing homes: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 43, 281–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhedhi, S. A. , Swinglehurst, D. , & Russell, J. (2014). ‘Timely’ diagnosis of dementia: What does it mean? A narrative analysis of GPs' accounts. British Medical Journal Open, 4, e004439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, M. T. , & Morgan, D. L. (1994). Sharing the caring: Family caregivers' views of their relationships with nursing home staff. The Gerontologist, 34, 235‐244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry, M. , Chenoweth, L. , Macgregor, C. , & Arendts, G. (2015). Emergency nurses perceptions of the role of family/carers in caring for cognitively impaired older persons in pain: A descriptive qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52, 1323–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler, J. E. (2005). Family involvement in residential long‐term care: A synthesis and critical review. Aging Mental Health, 9, 105–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler, J. E. , & Kane, R. L. (2007). Families and assisted living. The Gerontologist, 47, 83–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, C. , Davies, S. L. , Dickinson, A. , Gage, H. , Froggatt, K. , Morbey, H. , … Iliffe, S. (2013). A study to develop integrated working between primary health care services and care homes. Southampton: NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation Programme. [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim, U. H. , Johansson, A. , & Lindgren, B. M. (2014). Family caregivers' experiences of relinquishing the care of a person with dementia to a nursing home: Insights from a meta‐ethnographic study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 28, 215–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graverholt, B. , Forsetlund, L. , & Jamtvedt, G. (2014). Reducing hospital admissions from nursing homes: A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 14, 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haesler, E. , Bauer, M. , & Nay, R. (2010). Recent evidence on the development and maintenance of constructive staff–family relationships in the care of older people—A report on a systematic review update. International Journal of Evidence‐Based Healthcare, 8, 45–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzberg, A. , & Ekman, S. L. (2000). ‘We, not them and us?’ Views on the relationships and interactions between staff and family members of older people permanently living in nursing homes. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 31, 614–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, B. D. W. , Brazil, K. , Passmore, P. , Buchanan, H. , Maxwell, D. , McIlfatrick, S. J. , … Parsons, C. (2017). Exploring healthcare assistants' role and experience in pain assessment and management for people with advanced dementia towards the end of life: A qualitative study. BMC Palliative Care, 16, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y. S. , & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lisk, R. , Yeong, K. , Nasim, A. , Baxter, M. , Mandal, B. , Nari, R. , & Dhakam, Z. (2012). Geriatrician input into nursing homes reduces emergency hospital admissions. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 55, 331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason, J. (2002). Qualitative researching. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Mental Capacity Act (2005). Office of Public Sector Information. Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/contents

- Mentes, J. C. , Teer, J. , & Cadogan, M. P. (2004). The pain experience of cognitively impaired nursing home residents: Perceptions of family members and certified nursing assistants. Pain Management Nursing, 5, 118–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan, C. (2012). There's no place like home: Place and care in an ageing society. Surrey, UK: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.. [Google Scholar]

- Morphet, J. , Innes, K. , Griffiths, D. L. , Crawford, K. , & Williams, A. (2015). Resident transfers from aged care facilities to emergency departments: Can they be avoided? Emergency Medicine Australasia, 27, 412–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullin, J. , Simpson, J. , & Froggatt, K. (2011). Experiences of spouses of people with dementia in long‐term care. Dementia, 12, 177–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Service (2016). NHS Outcomes Framework 2016 to 2017. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/513157/NHSOF_at_a_glance.pdf

- National Health Service England (NHS) (2013). Transformation participation in health and care ‘The NHS belongs to us all’. Retrieved from https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/trans-part-hc-guid1.pdf

- Nguyen, M. , Pachana, N. A. , Beattie, E. , Fielding, E. , & Ramis, M. A. (2015). Effectiveness of interventions to improve family‐staff relationships in the care of people with dementia in residential aged care: A systematic review protocol. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 13, 52–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, M. (2001). Working with family carers: Towards a partnership approach. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 11, 92–97. [Google Scholar]

- Office National Statistics (2014). Changes in the older resident care home population between 2001 and 2011. London: Office of National Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- O'Shea, F. , Weathers, E. , & McCarthy, G. (2014). Family care experiences in nursing home facilities. Nursing Older People, 26, 26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouslander, J. G. , Lamb, G. , Tappen, R. , Herndon, L. , Diaz, S. , Roos, B. A. , … Bonner, A. (2011). Interventions to reduce hospitalizations from nursing homes: Evaluation of the INTERACT II collaborative quality improvement project. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59, 745–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parveen, S. , Peltier, C. , & Oyebode, J. R. (2017). Perceptions of dementia and use of services in minority ethnic communities: A scoping exercise. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25, 734–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdy, S. , Griffin, T. , Salisbury, C. , & Sharp, D. (2009). Ambulatory care sensitive conditions: Terminology and disease coding need to be more specific to aid policy makers and clinicians. Public Health, 123, 169–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2012). NVivo qualitative data analysis software, Version 10. Doncaster Australia: QSR International Pty Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Scrutton, J. , & Brancati, C. U. (2016). Dementia and comorbidities: Ensuring parity of care. London: International Centre of Longevity. [Google Scholar]

- Silin, P. S. (2001). Nursing homes and assisted living: The family's guide to making decisions and getting good care. Baltimore, MD: JHU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P. , Sherlaw‐Johnson, C. , Ariti, C. , & Barsley, M. (2015). Quality watch. Focus on: Hospital admissions from care homes. London: Health Foundation and Nuffield Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, L. , Ritchie, J. , O'Connor, W. , Morrell, Gareth , & Ormston, R. (2014). Analysis in practice In Ritchie J., Lewis J., Nicholls C. M. & Ormston R. (Eds), Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers (2nd ed., pp. 295–343). London: Sage; [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y. , Dixon, A. , & Gao, H. (2012). Emergency hospital admissions for ambulatory care‐sensitive conditions: Identifying the potential for reductions. Retrieved from https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/data-briefing-emergency-hospital-admissions-for-ambulatory-care-sensitive-conditions-apr-2012.pdf

- Ward, K. , Gott, M. , & Hoare, K. (2015). Participants' views of telephone interviews within a grounded theory study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71, 2775–2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, S. W. , Zimmerman, S. , & Williams, C. S. (2012). Family caregiver involvement for long‐term care residents at the end of life. Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67, 595–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young, Y. , Inamdar, S. , Dichter, B. S. , Kilburn, H. , & Hannan, E. L. (2011). Clinical and nonclinical factors associated with potentially preventable hospitalizations among nursing home residents in New York State. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 12, 364–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]