Abstract

Commercially utilized parabens are employed for their antimicrobial properties, but a weak binding to the estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) may lead to breast cancer in some applications. Modification of the paraben scaffold should allow for a disconnection of these observed properties. Toward this goal, various 3,5-substituted parabens were synthesized and assessed for antimicrobial properties against S. aureus as well as competitive binding to the ERα. The minimum inhibitory concentration assay confirmed retention of antimicrobial activity in many of these derivatives, while all compounds exhibited decreased xenoestrogen activity as determined by a combination of competitive enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), proliferation, and estrogen receptor binding assay. Thus, these changes to the paraben scaffold have led to a multitude of paraben derivatives with antimicrobial properties up to 16 times more active than the parent paraben and that are devoid or significantly diminished of potential breast cancer causing properties.

Keywords: Paraben, preservative, antimicrobial, cosmetic, cancer, xenoestrogen

Parabens have been used within cosmetics for over 30 years with their initial safety assessment being performed in 19841 and reiterated by the Cosmetic Ingredient Review (CIR) in 2008.2 Despite approval under their current utility, parabens are still met with controversy leading back to the Routledge et al. publication that illustrated their xenoestrogenic properties in 1998.3 The antiparaben sentiment was fueled in 2004 by the finding breast tumor tissue that contained trace amounts of parabens, despite the fact that the article failed to determine the cause and effect relationship to their presence.4 Admittedly, the debate over paraben safety is still ongoing, but the fear of their utility can be seen in the ever increasing restrictions on their use. Most recently, in 2014, the European commission reduced the allowed maximum concentration of propyl and butyl paraben from 0.4% to 0.14% in products.5

Topical applications of paraben containing cosmetics or pharmaceuticals tend to be more problematic than ingestion.6 This is due to digestion through general stomach acids, and esterases found in the kidneys and liver are extremely efficient at hydrolyzing the ester function to the corresponding p-hydroxybenzoic acid.7 Alternatively, the carboxylesterases found on human skin are less effective at hydrolyzing the ester function leading to epidermal penetration of the paraben.8,9 This is made more concerning when combined with the finding that indicates parabens remain in skin tissue samples or that food consumption only accounts for a 1% of an individual’s daily paraben exposure.6

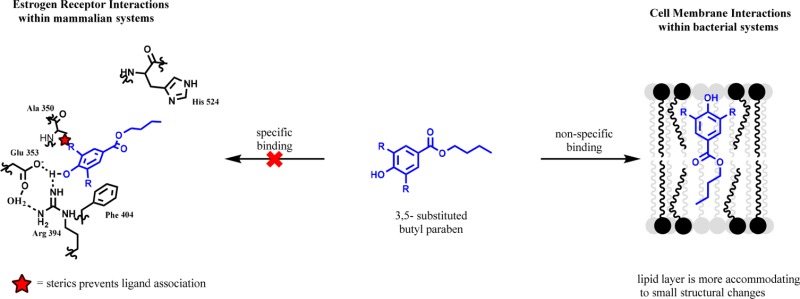

A complete ban on paraben use has been avoided due to their effectiveness and widespread application as preservatives.10 The effectiveness of parabens is attributed to a multitude of activities that involve their ability to inhibit glycolysis,11 protein synthesis,12 and increasing cell membrane permeability.13 Comparing the bactericidal activities shows that parabens are most potent in their action on the cell membrane of bacteria. The exact mode of action is not entirely understood but is thought to be similar to other organic compounds and phenolic disinfectants.14,15 This is believed to involve a nonspecific insertion into the cell membrane, which increases the membrane fluidity and decreases its integrity, while the phenolic function is capable of disrupting the cation gradient across the membrane leading to osmolysis.

Alternatively, parabens have been linked to breast cancer through their xenoestrogen properties.3 Many phenols can bind the estrogen receptor (ERα) leading to upregulation of gene expression similar to estrogen.16 Admittedly, the system is complex such that the genes expressed by xenoestrogen compounds of similar structures (even differing parabens) can lead to varying gene expression profiles.17 This activity requires a specific binding interaction between the paraben and the ER-estrogen binding site.18 From known xenoestrogen activities, it has been shown that mimicking the phenolic function of estrogen is most important for ERα binding and thus is the most likely pharmacophore in parabens.19

The nonspecific (lacking enzymatic binding) antimicrobial activities associated with parabens should lend greater flexibility in their structure–activity relationship (SAR). Alternatively, the specific binding of the phenolic function to the ERα is likely to result in a less amenable SAR associated with their xenoestrogen properties. A plethora of molecules capable of activating the estrogen receptor have been reviewed, which does indicate a potential flexibility in the binding pocket. However, Terasaki et al. examined the activation of the ERα by chlorinated parabens produced during the chlorination of wastewater and found that mono- and dichlorinated parabens tend to be less active or entirely inactive.20 This work is encouraging to the prospects that dissociation of the two activities is possible.

Herein, it can be seen that paraben activities can be dissociated given that the antimicrobial properties result from a nonspecific binding to the cell wall, while the precancerous activity results from a specific binding of the ER. To show that the disassociation of the SARs are related to a general blocking of access to the phenolic function, a multitude of substituted paraben was synthesized and screened. Thus, we report 3,5-substitutions to butyl paraben derivatives that are equivalent if not improved antimicrobial compounds that lack the competitive ER binding. To confirm the continued antimicrobial properties of these compounds a microdilution assay was used to determine minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC). Alternatively, an estradiol competition enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and cell proliferation assay were used to illustrate the efficacy of these potential precancerous activities. The affinity for the ERα was then determined by a time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET) binding assay.

Chemistry

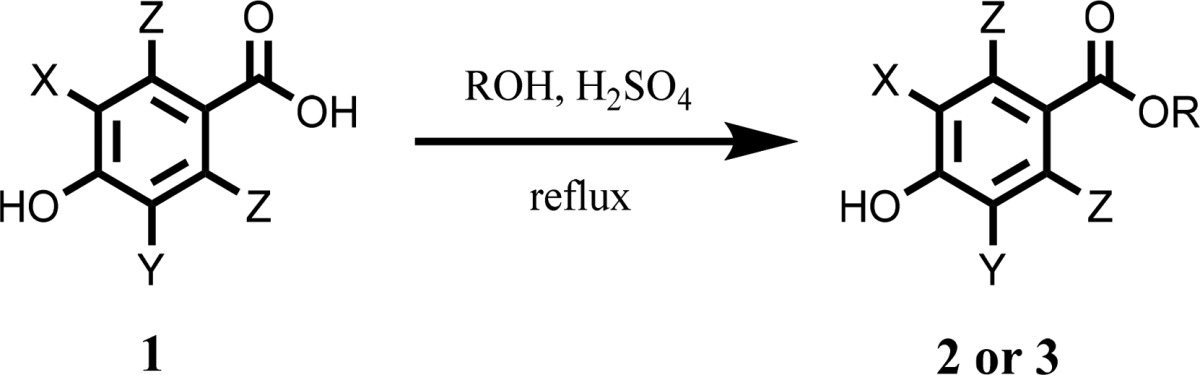

To prevent alkylation of the phenolic function, Fisher esterification, illustrated in Table 1, was used to convert various 3,5-substituted p-hydroxybenzoic acid derivatives 1 to their corresponding butyl or octyl esters, 2 and 3, respectively. Catalytic amounts of sulfuric acid were used to enhance the reaction rates, while tosylic acid failed to enhance conversion despite being devoid of water. Ester formation often required overnight (∼18 h) reflux but failed to show complete conversion by thin layer chromatography (TLC). Electron withdrawing groups such as halides and nitro functions allowed for faster reaction times.

Table 1. Results from Paraben Derivative Synthesis and Antimicrobial Screening against S. aureus.

| X, Y, Z | ROH | compd | rxn time (h) | rxn yield (%) | S. aureus MIC μg/mL (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F, F, F | BuOH | 2a | 18 | 35 | 128 (483) |

| Cl, Cl, H | BuOH | 2b | 18 | 65 | 64 (245) |

| Br, Br, H | BuOH | 2c | 18 | 53 | 32 (91) |

| Br, H, H | BuOH | 2d | 18 | 66 | 64 (236) |

| I, I, H | BuOH | 2e | 1 | 75 | 16 (36) |

| I, H, H | BuOH | 2f | 18 | 42 | 64 (199) |

| CH3, CH3, H | BuOH | 2g | 18 | 70 | >256a (>1045) |

| tBu, tBu, H | BuOH | 2h | 18 | 67 | >256a (834) |

| OH, OH, H | BuOH | 2i | 18 | 50 | 512 (2055) |

| OMe, OMe, H | BuOH | 2j | 18 | 88 | >256a (924) |

| NO2, NO2, H | BuOH | 2k | 3 | 56 | 512 (1809) |

| I, I, H | OctOH | 3e | 1 | 59 | 16 (31.8) |

| CH3, CH3, H | OctOH | 3g | 18 | 71 | 64 (213) |

| OH, OH, H | OctOH | 3i | 18 | 40 | 64 (210) |

| NO2, NO2, H | OctOH | 3k | 18 | 82 | 16 (47) |

| butyl parabenb | 256 (1320) | ||||

| penicillin G | 0.25 (0.749) |

Not soluble at the higher 512 μg/mL concentration and therefore was not tested.

Equivalent to butyl ester (2) with X, Y, Z = H, H, H.

This process proved reliable, but product purification often required multiple flash chromatography purifications. Throughout purification, the purity was confirmed by 1H NMR to ensure that the reactant alcohol was removed. The purity of individual column fractions could be qualitatively determined by staining TLCs with KMnO4. Moderate yields could be achieved even with these extra purification steps and can be seen in Table 1.

Biology

Antimicrobial activity was determined by finding the MIC via dilution assays in 96-well plates. Reproducibility was confirmed through trials run in duplicate across three separate days for a total of six biological replicates. S. aureus was used as a representative Gram-positive bacteria. Each paraben derivative was dissolved in biological grade DMSO to generate stock solutions at both 128 and 16 mg/mL. Serial dilution of the paraben derivatives then began at 512 μg/mL and occurred in half-fold dilutions with the exception of those not soluble above 256 μg/mL. Some samples reported with MICs at or greater than 256, most notably 2h, illustrate the first concentrations that appear visibly cloudy. Due to the assay pushing the limits of these compounds solubility, active compounds were tested with a minimum of one trial beginning at 128 μg/mL (∼500 μM), including the parent butyl paraben, to confirm dilution errors are not present. Butyl paraben and penicillin G were used to compare activities. The results of these studies can be found in Table 1.

Screening against S. aureus allowed for a SAR that could be compared directly to the commercially available paraben. In all derivatives we saw comparable if not improved antimicrobial activity from prepared 3,5-substituted parabens. The increased activity is likely a result of a combined increase in hydrophobicity and decrease in phenolic pKa. Halogenated parabens, 2a–2f, provided the greatest increase in activity against S. aureus; however, such changes in phenols have been documented before.20 Aliphatic substitutions, 2g and 2h, initially appeared to have lost all activity; however, increasing the hydrophobicity of the ester function led to recovered activity in 3g.21 This indicates that more aliphatic aromatic substitutions decrease solubility to a degree that underlying antimicrobial activity may no longer be observable. Increasing the lipophilicity of the ester increases antimicrobial activity presumably faster than it is decreasing compound solubility. Since all of these changes, 2 to 3, increased activity. It is important to note that 3e is likely more active than 2e but appears that the error in the serial dilution assay fails to allow an exact determination of this extent.

Polar substitutions, 2i and 2k, allowed for increased solubility and thus observable MIC values of 512 μg/mL were obtained. These extremely polar substitutions reiterate that a multitude of 3,5-substitutions on the paraben can be tolerated in these derivatives. Lengthening of these ester carbon chains, 3i and 3k, also increased these activities. Most importantly these derivatives provided a great recovery of antimicrobial activity compared to their butyl esters and offer balanced water solubility.

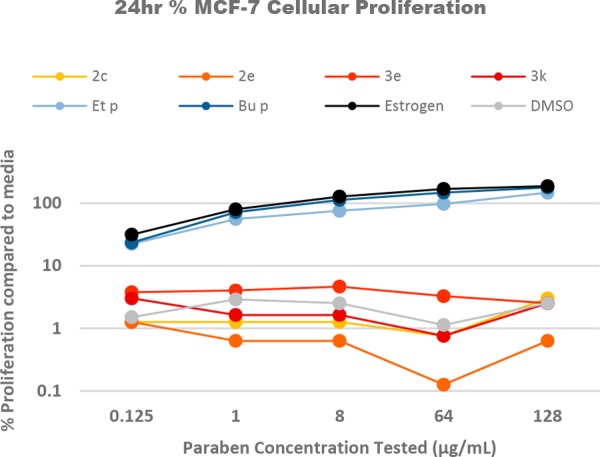

Cellular proliferation has been a hallmark measure for precancerous activity and remains to be an indicator of such. To investigate the MCF-7 cellular response from these new paraben derivatives, we have grown cells in the presence and absence of parabens and paraben derivatives 2 and 3. Figure 1 contains the cellular proliferation as a percent difference relative to proliferation in media for ethyl paraben, butyl paraben, estrogen, and the most active antibiotic paraben derivatives (2c, 2e, 3e, 3k). As expected, cellular proliferation for butyl paraben is very similar to estrogen stimulated cells; however, ethyl paraben stimulates proliferation to a lesser extent. Comprehensively, all derivatives lacked the cellular response leading to proliferation comparable to the control. The complete data set was removed for clarity but can be found in the Supporting Information. Cellular proliferation can be the response to various cellular stimuli, and it is not necessarily a result of the ER being stimulated. Therefore, it is important to look at a stimulation more closely linked to the ER activity.

Figure 1.

Percent MCF-7 cell proliferation after 24 h stimulation.

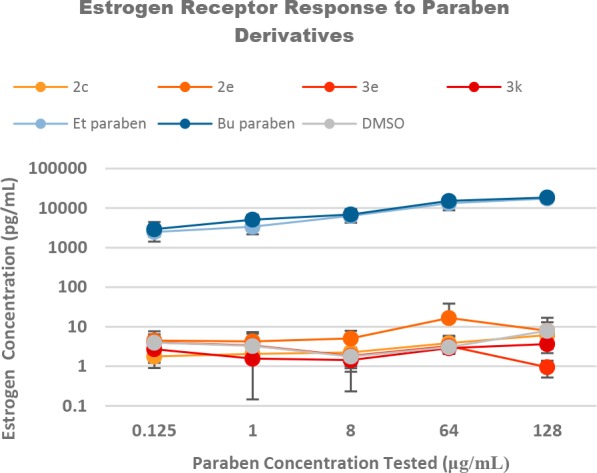

To determine the influence such substitution had on the activation of the ERα, we chose to screen the compounds via an estradiol competitive ELISA. MCF-7 cell response to the presence of paraben derivatives was correlated to an increase in estradiol concentration after 24 h of cell stimulation.22 Prior to ELISA analysis, we verified that the cells were viable in the presence of each paraben for this duration using the Pierce LDH Cytotoxicity Assay. All compounds proved to be nontoxic to MCF-7 cell proliferation and grew similar to the controls at 24, 48, and 72 h (results in Supporting Information).

Both commercially available ethyl and butyl paraben stimulated the production of estrogen within MCF-7 cells as shown in Figure 2. This matches the observed response from previous literature.23 As a control, DMSO was incubated with MCF-7 cells for the 24 h duration at volumes equal to and exceeding those required for compound addition (0, 1, 1.6, 8, and 16 μL) from DMSO stocks. No statistical difference in cell stimulation was observed for any of these volumes. The parabens and paraben derivatives were screened at concentrations of 0.125, 1, 8, 64, and 128 μg/mL (representing a maximum concentration tested range of 290 to 770 μM). While the commercial parabens stimulated estrogen production, all substituted derivatives failed to illustrate activities statistically different from the control or a response across various concentrations. For clarity, the more antimicrobial derivatives (2c, 2e, 3e, 3k) are shown in Figure 2, while the complete figure can be found within the Supporting Information. These combined data do tend to illustrate the reduced efficacy of substituted parabens relative to commercial parabens; however, it does not preclude the possibility of some binding interaction.

Figure 2.

MCF-7 estrogen receptor response to parabens and paraben derivatives.

A terbium based time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET) binding assay was used to determine the extent to which these parabens are interacting with the estrogen receptor. The assay used is a service of SelectScreen nuclear receptor profiling (Madison, WI) under Thermo Fisher Scientific. Within this assay a terbium-labeled anti-GST antibody binds the GST domain of the estrogen receptor. When a fluorescently tagged estrogen is bound to the estrogen receptor, there is high TR-FRET response. Competition with this labeled estrogen leads to a decreased response allowing for a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) to be determined. This IC50 is then related to the ability for the parabens to displace 50% of the tagged estrogen. For reference, 17-β-estradiol displaces 50% of this labeled estrogen at an IC50 of 0.452 nM, when the tagged estrogen is maintained at a concentration of 3 nM. It is also important to note that increased concentrations (up to 200,000 nM or roughly 64 μg/mL for MIC comparison) were investigated since the typical maximum 10,000 nM concentrations were suspected to miss the weaker IC50 values.

Under these conditions, butyl paraben displaced 50% of the labeled estrogen at 1420 nM. Table 2 shows that all substituted parabens proved to be weaker binders than this parent paraben. Most of which were between 20 and 40 times weaker binders with the exceptions being monosubstituted 2d and 2f and polyphenol 2i. These illustrated only six-fold weaker binding, which shows that substitution to both sides of the phenols is required to see drastic changes in binding. Also the poly-phenol derivative is most likely made weaker by the additional sterics, but the additional points of attachments in the other phenols allow it to maintain significant binding potential. The increased binding from longer alkyl chains of esters 3 is analogous to the tritium based competition assay performed by Blair et al.16 Compounds 2h, 2j, and 2k appear to have lost affinity for the estrogen receptor, but it is important to note that these compounds displaced nearly 20% of the labeled estrogen at the highest concentrations tested. Even if solubility prevents identification of their IC50 this indicates that they may still have some affinity for the estrogen receptor and that binding is not entirely abolished in any of these cases.

Table 2. IC50s for Paraben Binding to ERα as Determined by TR-FRET Analysis.

| X, Y, Z | compd | IC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|

| F, F, F | 2a | 29400 |

| Cl, Cl, H | 2b | 55300 |

| Br, Br, H | 2c | 39400 |

| Br, H, H | 2d | 8210 |

| I, I, H | 2e | 34600 |

| I, H, H | 2f | 7980 |

| CH3, CH3, H | 2g | 32500 |

| tBu, tBu, H | 2h | >200000 |

| OH, OH, H | 2i | 8970 |

| OMe, OMe, H | 2j | >200000 |

| NO2, NO2, H | 2k | >200000 |

| I, I, H | 3e | 13200 |

| CH3, CH3, H | 3g | 16200 |

| OH, OH, H | 3i | 8740 |

| NO2, NO2, H | 3k | 60400 |

| H, H, H | butyl paraben | 1420 |

| 17-β-estradiol | 0.452 |

In summary, we have produced paraben derivatives that have improved antimicrobial properties while lacking the undesirable xenoestrogen properties associated with tumor cell production. Increased substitution near the phenolic function of the parabens has led to weaker association to the estrogen receptor. The broad lack of estrogen receptor activation is expected to be, in part, a response to this decreased affinity. With most of the modifications (except 2i, 2k, 3i, and 3k) arising in more hydrophobic parabens, the investigations into mammalian cell permeability and other mammalian cell membrane associations is important for a complete understanding of the intracellular activity. Most importantly these substitutions allow the lengthening of the ester alkyl chain to improve antimicrobial properties while decreasing the cost of added precancerous activities. We are working now to confirm that ester chain lengths follow the general trends associated with commercial parabens and to complete computational analysis of such substituted parabens bound within the known crystal structure of ERα. The latter will hopefully provide insight into the extent that distortions of the binding pocket might provide the remainder of activity lost.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Hampden Sydney College for the use of their Joel 400 MHz NMR for identification of the perfluorinated 13C NMR, NC State University’s Mass Spectroscopy Facility for the HRMS, and Longwood’s Chemistry and Physics Department for constant support.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- ER

estrogen receptor

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- Rxn

reaction

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- TLC

thin layer chromatography

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- MCF-7

Michigan Cancer Foundation-7 (human breast adenocarcinoma cell line)

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00431.

Experimental procedures, compound characterizations, and compound purity determination (PDF)

Author Present Address

† Department of Biological Sciences and Environmental Sciences, Longwood University, 201 High Street, Farmville, Virginia 23909, United States.

Author Contributions

‡ These authors contributed equally. A.A.Y. wrote the article with contributions from other authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Longwood’s summer research program (PRISM), LU Office of Student Research, Faculty Development grant, and the Office of the Dean of Cook-Cole College of Arts and Sciences.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Elder R. L. Final report on the safety assessment of methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, and butylparaben. J. Am. Coll. Toxicol. 1984, 3, 147–209. 10.3109/10915818409021274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson F. A. Final amended report on the safety assessment of methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, isopropylparaben, butylparaben, isobutylparaben, and benzylparaben as used in cosmetic products. Int. J. Toxicol. 2008, 27, 1–82. 10.1080/10915810802548359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routledge E. J.; Parker J.; Odum J.; Ashby J.; Sumpter J. P. Some alkyl hydroxyl benzoate preservatives (parabens) are estrogenic. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1998, 153, 12–19. 10.1006/taap.1998.8544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darbre P. D.; Aljarrah A.; Miller W. R.; Coldham N. G.; Sauer M. J.; Pope G. S. Concentrations of parabens in human breast tumors. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2004, 24, 5–13. 10.1002/jat.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Commision. European Commission: Press Release Database. Consumers: Commission improves safety of cosmetics. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-14-1051_en.htm (accessed June 23, 2017).

- Soni M. G.; Carabin I. G.; Burdock G. A. Safety assessment of esters of p-hydroxybenzoic acid (parabens). Food Chem. Toxicol. 2005, 43, 985–1015. 10.1016/j.fct.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bando H.; Mohri Y.; Yamashita F.; Takakura Y.; Hashida M. Effects of metabolism on percutaneous penetration of lipophilic drugs. J. Pharm. Sci. 1997, 86, 759–761. 10.1021/js960408n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewell C.; Prusakiewicz J. J.; Ackermann C.; Payne N. A.; Fate G.; Voorman R.; Williams F. M. Hydrolysis of a series of parabens by skin microsomes and cytosol from human and minipigs and in whole skin in short-term culture. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2007, 225, 221–228. 10.1016/j.taap.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Hussein S.; Muret P.; Berard M.; Makki S.; Humbert P. Assessment of principal parabens used in cosmetics after their passage through human epidermis-dermis layers (ex-vivo study). Exp. Dermatol. 2007, 16, 830–836. 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzetti O. J.; Wernet T. C. Topical parabens: benefits and risks. Dermatology 1977, 154, 244–250. 10.1159/000251072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y.; Marquis R. E. Irreversible paraben inhibition of glycolysis by Streptococcus mutans GS-5. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1996, 23, 329–333. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.1996.tb00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nes I. F.; Eklund T. The effect of parabens on DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1983, 54, 237–242. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1983.tb02612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heipieper H.-J.; Keweloh H.; Rehm H.-J. Influence of phenols on growth and membrane permeability of free and immobilized Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991, 57, 1213–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook A. M. Phenolic Disinfectants. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1960, 12, 19T–28T. 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1960.tb10451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos F. M.; Couto J. A.; Figueiredo A. R.; Tóth I. V.; Rangel A. O. S. S.; Hogg T. A. Cell membrane damage unduced by phenolic acids on wine lactic acid bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 135, 144–151. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair R. M.; Fang H.; Branham W. S.; Hass B. S.; Dial S. L.; Moland C. L.; Tong W.; Shi L.; Perkins R.; Sheehan D. M. The estrogen receptor relative binding affinities of 188 natural and xenochemicals: Structural diversity of ligands. Toxicol. Sci. 2000, 54, 138–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler A. J.; Pugazhendhi D.; Darbe P. D. Use of global gene expression patterns in mechanistic studies of oestrogen action in MCF7 human breast cancer cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2009, 114, 21–32. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzozowski A. M.; Pike A. C. W.; Dauter Z.; Hubbard R. E.; Bonn T.; Engström O.; Öhman L.; Greene G. L.; Gustafsson J.-Ǻ.; Carlquist M. Molecular basis of agonism and antagonism in the oestrogen receptor. Nature 1997, 389, 753–758. 10.1038/39645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byford J. R.; Shaw L. E.; Drew M. G. B.; Pope G. S.; Sauer M. J.; Darbre P. D. Oestrogenic activity of parabens in MCF7 human breast cancer cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2002, 80, 49–60. 10.1016/S0960-0760(01)00174-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasaki M.; Kamata R.; Shiraishi F.; Makino M. Evaluation of estrogenic activity of parabens and their chlorinated derivatives by using the yeast two-hybrid assay and the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2009, 28, 204–208. 10.1897/08-225.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukahori M.; Akatsu S.; Sato H.; Yotsuyanagi T. Relationship between uptake of p-hydroxybenzoic acid eesters by Escherichia coli and antimicrobial activity. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1996, 44, 1567–1570. 10.1248/cpb.44.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintermantel T. M.; Campbell R. E.; Porteous R.; Bock D.; Gröne H.-J.; Todman M. G.; Korach K. S.; Greiner E.; Pérez C. A. Definition of Estrogen Receptor Pathway Critical for Estrogen Positive Feedback to Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Neurons and Fertility. Neuron 2006, 52, 271–280. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darbre P. D.; Harvey P. W. Paraben esters: review of recent studies of endocrone toxicity, absorption, esterase and human exposure, and discussion of potential human health risks. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2008, 28, 561–578. 10.1002/jat.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.