Abstract

Background

Physical activity improves health, exercise tolerance and quality of life in adults with congenital heart disease (CHD), and exercise training is in most patients a high-benefit low risk intervention. However, factors that influence the confidence to perform exercise training, i.e. exercise self-efficacy (ESE), in CHD patients are virtually unknown. We aimed to identify factors related to low ESE in adults with CHD, and potential strategies for being physically active.

Methods

Seventy-nine adults with CHD; 38 with simple lesions (16 women) and 41 with complex lesions (17 women) with mean age 36.7 ± 14.6 years and 42 matched controls were recruited. All participants completed questionnaires on ESE and quality of life, carried an activity monitor (Actiheart) during four consecutive days and performed muscle endurance tests.

Results

ESE in patients was categorised into low, based on the lowest quartile within controls, (≤ 29 points, n = 34) and high (> 29 points, n = 45). Patients with low ESE were older (42.9 ± 15.1 vs. 32.0 ± 12.4 years, p = 0.001), had more complex lesions (65% vs. 42%, p = 0.05) more often had New York Heart Association functional class III (24% vs. 4%, p = 0.01) and performed fewer shoulder flexions (32.5 ± 15.5 vs. 47.7 ± 25.0, p = 0.001) compared with those with high ESE. In a logistic multivariate model age (OR; 1.06, 95% CI 1.02–1.10), and number of shoulder flexions (OR; 0.96, 95% CI 0.93–0.99) were associated with ESE.

Conclusion

In this study we show that many adults with CHD have low ESE. Age is an important predictor of low ESE and should, therefore, be considered in counselling patients with CHD. In addition, muscle endurance training may improve ESE, and thus enhance the potential for being physically active in this population.

Keywords: Exercise self-efficacy, Adult congenital heart disease, Quality of life, Muscle function, Physical activity

1. Introduction

Due to advances in surgical and medical care, the majority of children born with congenital heart disease (CHD) reach adulthood. Therefore, this patient group is a growing and aging population [1] and with improved survival increased need for re-intervention might be expected in adults with CHD [2]. The exposure to traditional cardiovascular risk factors in addition to the potential need for re-intervention renders the prevention of acquired cardiovascular disease even more important in this group. In the prevention of acquired cardiovascular disease physical activity plays an important role [3], [4], [5].

On a group level, adults with CHD have reduced aerobic exercise capacity [6] and impaired muscle endurance [7], [8]. The reasons for this are multifactorial and includes cardiac limitations, respiratory causes [9], [10], [11], inappropriate advice regarding exercise [12] and overprotection by parents and relatives [13]. Physical activity improves health, exercise tolerance as well as quality of life in adults with CHD, and exercise training is a high-benefit low risk intervention in most patients with CHD [14]. Also, we previously showed that a more physically active lifestyle is associated with better quality of life in adults with congenital aortic valve disease [15]. Thus, physical activity seems to be important for quality of life, but in adults with CHD there are several factors that may potentially limit a physically active lifestyle.

Self-efficacy refers to patient's initial decision to perform behavioural changes and their capability to successfully adhere to specific health behaviours such as compliance to exercise training regimes [16]. To measure exercise self-efficacy (i.e. measuring the confidence in performing physical exercise), different versions of the exercise self-efficacy scale have been used [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]. We have previously reported that exercise self-efficacy, using the protocol suggested by Ahlström [21], on a group level is reduced in adults with CHD [8], but variables that are related to exercise self-efficacy in this population are essentially unknown.

In the present paper we studied exercise self-efficacy in a population with mixed CHD, and compared these data with an age and sex matched population (non-CHD). The aim was to identify factors related to low exercise self-efficacy in adults with CHD, and potential strategies for being physically active.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

Seventy-nine adult patients (≥ 18 years) with CHD were recruited from the University hospital centres in Umeå and Lund in Sweden. The inclusion criteria were periodic out-patient medical visits for CHD and a clinically stable condition over the past three months. The exclusion criteria were cognitive impairment, disability or mental illness affecting independent decision-making, extra-cardiac disease affecting physical activity or other circumstances making participation unsuitable. To achieve a balanced diversity of diagnoses and complexities (since the simple lesions are much more common) patients were recruited into the following four different groups based on diagnosis: (1) shunt lesions, (2) left-sided lesions, (3) repaired tetralogy of Fallot/transposition of the great arteries (TGA), and (4) Eisenmenger/Fontan/TCPC/other complex lesions. Forty-two patients had at least one previous intervention (simple lesions 32%, complex lesions 73%) (Table 1). No patients had a lesion indicating intervention, e.g. severe aortic diagnosis. Among the patients eighteen had beta-blockers, five had calcium channel blockers and twenty-one had angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers. Recruitment was continued until each group comprised at least 20 patients with complete data. Groups (1) and (2) were classed as ‘simple’ lesions and (3) and (4) as ‘complex’ lesions, see Table 1. This classification has been used by others [22] and harmonizes with the expected exercise capacity [6]. The recruitment of patients was previously described in detail [23].

Table 1.

Distribution of heart lesions and classification into simplex vs. complex lesions.

| Simple lesion | n = 38 | Complex lesion | n = 41 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CoA | 9b | d-TGA (atrial switch) | 4 |

| AS | 3 | ccTGAc | 1 |

| AR | 3a | ToF | 9 |

| AS/AR | 4a | PA | 3 |

| ASD | 2 | DORV | 2 |

| VSD | 14a | DILVc | 1 |

| PFO | 1a | TCPC | 9 |

| PDA | 1a | RA-PA Fontan | 2 |

| MR | 1a | Ebsteinc | 3 |

| Eisenmengerc | 6 | ||

| Miscellaneous | 1 |

CoA, coarctation of the aorta; AS, aortic stenosis; AR, aortic regurgitation; ASD, atrial septal defect; VSD, ventricular septal defect; PFO, persistent foramen ovale; PDA, persistent ductus arteriosus; MR, mitral regurgitation; d-TGA, d-transposition of the great arteries; ccTGA, congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries; ToF, tetralogy of Fallot; PA, pulmonary artresia; DORV, double outlet of the right ventricle; DILV, double inlet of the left ventricle; TCPC, total cavo-pulmonary connection. RA-PA, right atrium to pulmonary artery.

One patient had a previous intervention.

Six patients had previous interventions.

No previous intervention.

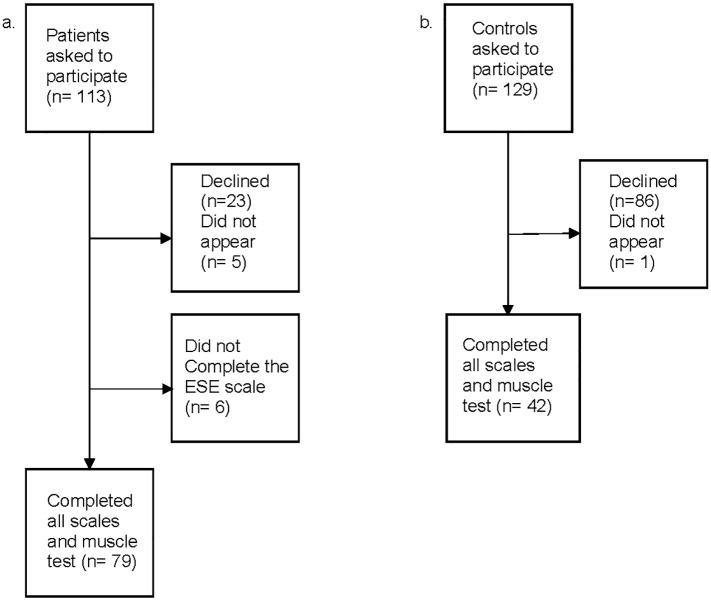

Forty-two age and gender-matched controls (non CHD or any of the exclusion criteria presented above) who lived in the Umeå area were randomly recruited via the Swedish national population register. For each gender, the patients were ranked according to age. For every consecutive pair of patients with the same gender a control person with the mean age of this pair of patients was recruited. Among the controls, five had anti-hypertensive treatment, two had ASA, one had statins and one had all three treatments. Fig. 1 gives an overview of patient and control group recruitment. This population of patients and controls were also included in previous reports that focused other outcomes [8], [23]. Prior to participation in the present study or previous studies patients and controls gave their informed consent.

Fig. 1.

Overview of recruited patients (a) and controls (b).

2.2. Ethical considerations

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, as revised in 2008, and have been approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Umeå (registration number 2011-51-31 M, 2011).

2.3. Instruments and procedure

According to the study protocol, the muscle endurance test were performed first, followed by the application of the activity monitor and finally the patients completed the questionnaires. All tests were performed during a clinic visit.

2.4. The exercise self-efficacy scale

In the present work, the recently validated Swedish version of the ESE scale was used [21]. The exercise self-efficacy (ESE) scale is an instrument used to evaluate the confidence of being physically active. The scale consists of 10 items, each item is scored on a four point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 4 (1 = not at all true, 2 = rarely true, 3 = moderately true, 4 = always true). The best possible ESE scale score is 40 points. The ESE scale is a validated instrument with high internal consistency and scale integrity [20].

2.5. The EQ-5D self-reported questionnaire

The EuroQoL-5 Dimension Questionnaire was developed by the EuroQol Group with a purpose of developing a validated and non-disease specific measure of quality of life (QoL) to complement other health-related instruments [24]. The questionnaire evaluates health in five dimensions – mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Each dimension consists of three levels – no problem, some or moderate problems and extreme problems. Two hundred forty-three potential health statuses are possible (if including death or unconsciousness there are 245). The Swedish version of the EQ-5D self-reported questionnaire was used in this study. The information from EQ-5D questionnaire can be converted into an index (EQ-5Dindex) by using a formula weighting all levels in each dimension using an index tariff. The EQ-5Dindex value for best possible health status is 1, and the worst possible health status or death is 0 [24]. Since there is no Swedish version of the EQ-5D value set, the British index tariff was used as reference [25].

2.6. Muscle endurance tests

Shoulder flexion was performed with the participants sitting comfortably with their back touching the wall and holding a weight (2 kg for women and 3 kg for men) in the hand of the dominant side. Participants were asked to elevate the arm from 0° to 90° flexion as many times as possible at a frequency of 20 repetitions per minute guided by a metronome.

Heel lift was performed with the test person standing on one leg on a 10° tilted wedge touching the wall with the fingertips for balance. The contralateral foot was held slightly above the floor. The test persons were asked to perform as many heel-lifts as possible at a frequency of 30 repetitions per minute guided by a metronome [8], [26]. The muscle endurance tests have good test re-test reliability [26]. All tests were instructed and monitored by the same researcher (CS).

2.7. Actiheart

The Actiheart monitor (CamNTech Ltd., Cambridge, UK), a reliable and validated [27] combined heart rate monitor and accelerometer for ambulatory use, was worn day and night during four consecutive days following the clinic visit. The extent to which participants reached the current WHO recommendations on physical activity for promoting health was analyzed. For details see Ref. [23].

2.8. Data analysis

All calculations were performed using SPSS 20–23 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The distribution of data were visually assessed for normality. Differences in mean and ratios between groups were tested with Student's t-test or chi2-test respectively as appropriate. Exercise self-efficacy in patients was categorised into low (exercise self-efficacy ≤ 29 points) (n = 34), based on the lowest quartile within controls and the upper three quartiles (exercise self-efficacy > 29 points) (n = 45) was classed as high. The EQ-5D index was dichotomized into index = 1 vs. < 1. Variables used in multivariate analyses were selected by univariate logistic regression. Multivariate logistic regression was performed in a manual backward manner. The null hypothesis was rejected for p-values < 0.05.

3. Results

Patients with low exercise self-efficacy were older, had more complex lesions, had higher NYHA class (III), performed less shoulder flexions and performed fewer heel lifts compared with patients with high exercise self-efficacy (see Table 2). In the high group, exercise self-efficacy did not differ from controls (35.0 ± 3.04 vs. 33.4 ± 6.08, p = 0.11). The distribution of treatment with beta-blockers were equal between those with high and low ESE.

Table 2.

Overview of controls and patients characteristics.

| n | Controls (n = 42) | Patients (n = 79) | P1 | ESE low (n = 34) | ESE high (n = 45) | P2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age years | Mean ± SD | 121 | 36.9 ± 14.9 | 36.7 ± 14.6 | 0.95 | 42.9 (15.1) | 32.0 (12.4) | 0.001 |

| Sex female | n (%) | 121 | 16 (38) | 33 (42) | 0.69 | 12 (35) | 21 (47) | 0.31 |

| BMI kg/m2 | Mean ± SD | 121 | 25.8 ± 5.3 | 24.6 ± 4.1 | 0.17 | 25.0 (4.2) | 24.2 (4.1) | 0.39 |

| Medication yes | n (%) | 121 | 8 (19) | 40 (51) | 0.001 | 20 (59) | 20 (44) | 0.20 |

| Smoking yes | n (%) | 121 | 5 (12) | 15 (19) | 0.32 | 9 (27) | 6 (13) | 0.14 |

| EQ-5Dindex < 1 | n (%) | 121 | 22 (52) | 37 (47) | 0.56 | 20 (59) | 17 (38) | 0.06 |

| Shoulder flexion reps | Mean ± SD | 121 | 63.6 ± 40.4 | 41.2 ± 22.6 | 0.002 | 32.5 (15.5) | 47.7 (25.0) | 0.001 |

| Heel lift reps | Mean ± SD | 120 | 26.3 ± 12.8 | 20.9 ± 7.7 | 0.02 | 18.9 (7.4) | 22.4 (7.7) | 0.05 |

| Reaching WHO rec., yes | n (%) | 116 | 24 (57) | 34 (46) | 0.25 | 17 (52) | 17 (42) | 0.39 |

| NYHA class III | n (%) | 79 | NA | 10 (13) | NA | 8 (24) | 2 (4) | 0.01 |

| Complex heart lesion yes | n (%) | 79 | NA | 41 (52) | NA | 22 (65) | 19 (42) | 0.05 |

Exercise self-efficacy (ESE) in patients was categorised into low, based on the lowest quartile within controls (≤ 29 points) (patients n = 34) and high(≤ 29 points) (patients n = 45). Data are presented as means and standard deviations (SD) and proportions (percent). Reaching WHO recommendations on physical activity measured by Actiheart (data on 74 patients) P1, p-value for comparison between controls and patients; P2, p-value for comparison between ESE low and high; BMI, body mass index; EQ-5Dindex, EuroQoL 5-dimensions(index); reps, repetitions; MET, metabolic equivalent; NYHA, New York Heart Association functional class; NA, not applicable. Bold numbers indicate p < 0.05.

Variables possibly explaining exercise self-efficacy were tested in univariate logistic regression where age, shoulder flexion and NYHA class were associated with lower exercise self-efficacy see Table 3. Complexity of heart lesion and NYHA class were related, and were thus tested separately in the multivariate model but yielded the same result. Age and number of shoulder flexions were independently associated with exercise self-efficacy see Table 4.

Table 3.

Univariate logistic regression analysis with low exercise self-efficacy (≤ 29 points) as dependent variable.

| OR | 95% CI | P-Value | r2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age years | 1.06 | 1.02–1.10 | 0.002 | 0.18 |

| Sex female | 0.62 | 0.25–1.56 | 0.31 | 0.02 |

| BMI kg/m2 | 1.05 | 0.94–1.17 | 0.39 | 0.01 |

| Smoking yes | 2.34 | 0.74–7.38 | 0.15 | 0.04 |

| Medication yes | 1.8 | 0.73–4.40 | 0.21 | 0.03 |

| Shoulder flexion (reps) | 0.96 | 0.93–0.99 | 0.007 | 0.17 |

| Heel lift (reps) | 0.94 | 0.88–1.00 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| Reaching WHO rec. yes | 1.5 | 0.60–3.78 | 0.39 | 0.01 |

| Complex lesion | 2.5 | 1.00–6.29 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| NYHA–III | 6.62 | 1.30–33.57 | 0.02 | 0.11 |

| EQ-5Dindex < 1 | 0.43 | 0.17–1.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

Univariate logistic regression analysis with exercise self-efficacy as the dependent variable; OR, Odds Ratio; CI, 95% confidence interval; r2, variance in the dependent variable (Nagelkerke R square); BMI, body mass index; reps, repetitions; rec., recommendation; NYHA, New York Heart Association functional class; EQ-5D, EuroQoL 5-dimensions(index). Bold numbers indicate p < 0.05.

Table 4.

Multivariate model with variables associated with low exercise self-efficacy (≤ 29 points) as dependent variable.

| Initial model |

Final model |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | P-Value | |

| Age years | 1.05 | 1.01–1.09 | 0.02 | 1.05 | 1.02–1.09 | 0.006 |

| Smoking yes | 3.58 | 0.90–14.2 | 0.07 | |||

| Heel lift (reps) | 0.97 | 0.90–1.00 | 0.45 | |||

| Shoulder flexions (reps) | 0.96 | 0.92–1.00 | 0.07 | 0.96 | 0.93–0.99 | 0.02 |

| EQ-D5index < 1 | 0.56 | 0.19–1.67 | 0.29 | |||

| Complex lesions | 0.74 | 0.17–3.16 | 0.69 | |||

| NYHA class–III | 2.38 | 0.36–15.89 | 0.37 | |||

Multivariate regression analysis. OR, effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; reps, repetitions; EQ-5D, EuroQoL 5-dimensions(index); NYHA, New York Heart Association functional class. Bold numbers indicate p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we show that many adults with CHD have low confidence in performing exercise training. Age and muscle endurance were associated with lower exercise self-efficacy. Muscle endurance is possible to reach by intervention, and may thus potentially improve exercise self-efficacy. Furthermore, age was highly associated with lower exercise self-efficacy. An overall decrease in physical activity level associated with aging may be the reason, which is in line with previous reports [28]. In addition, it may be speculated that older patients, in their childhood, were given advice and restrictions on physical activity from doctors and relatives [12], [13], a practise that was more common in the past. Thus, this is something that may change as younger patients, advised according to contemporary guidelines, reach higher age. As the population of adults with CHD is expected to increase over the next decades [29], [30] the effect of aging in these patients will be a factor in need of careful attention.

Similar to the general population many patients with CHD, are known to be insufficiently active to reach the recommendations for physical activity [23]. In CHD patients and especially those who had previous cardiac surgery, it is important to avoid developing coronary artery disease. In the prevention of atherosclerosis, physical activity plays an important role and therefore should be promoted [3], [4], [5]. Nurses and other health care providers may help by increasing patients' confidence in being physically active and in performing exercise training. Individualized exercise prescription and advice are important for this group of patients to prevent future cardiovascular disease [31].

Previously exercise self-efficacy has only been reported in a limited number of CHD studies [32]. Until now, no attempts have been made to identify factors associated with impaired exercise self-efficacy in this population. Although a relatively small sample size the present study includes a broad spectrum of diagnoses, and it is therefore possible to apply our results for a majority of the population of adults with CHD. The results can help in identifying patients with low exercise self-efficacy and thereby offer individualized support, e.g. initialize prescription of muscle endurance training.

Quality of life is a complex entity. Previously we reported that a high physical activity level (i.e. exercise training > 3 h/week) is associated with a higher quality of life [15]. Here we show that exercise self-efficacy and quality of life are borderline associated, although in univariate mode, and this association is probably bidirectional. However, quality of life is a very broad concept and is difficult to reach with single interventions. Many of the factors associated with quality of life, as well as exercise self-efficacy, are modifiable and hopefully this translates also into improved quality of life.

Previous research have shown impaired muscle strength and endurance in adults with CHD [7], [8], [33]. Here we show that muscle endurance capacity, represented by shoulder flexions, was associated with exercise self-efficacy. However, a corresponding association was not found regarding heel lift and ESE. This might be explained by the frequent use of the calf muscles, e.g. during walking and standing (postural control), in contrast to the upper extremities that not to the same extent are stressed during daily activities. In any case, testing muscle endurance may be useful in the general assessment of adults with CHD. Furthermore, muscle exercise training programmes, with the aim to increase muscle function, may have the potential to improve both exercise self-efficacy and quality of life in adults with CHD [34]. Considering the association between muscle endurance in the upper extremities and ESE, the function of these muscles may actually reflect a higher level of upper body activity and thus be a source of ESE in this population.

4.1. Limitations

At present, there is no established limit for what is considered low or high exercise self-efficacy. We applied a definition of low exercise self-efficacy as the lowest quartile within controls. In order to challenge this model, a lower cut off based on the distribution within cases was tested and yielded similar results. Thus, our assumptions appear stable using either limit.

The sample size may appear relatively small but considering the unique population of adults with CHD and relating to studies in similar populations [32] our sample size is comparable.

None of the patients included in the study had recommendations on exercise restrictions, however we have no control over historical advice. In some patients, e.g. those with Eisenmenger syndrome, exercise is limited by symptoms already at low level. In this situation exercise is limited by symptoms irrespective of advice given by health care personal.

5. Conclusions

In this study, many adults with CHD had low exercise self-efficacy. Both age and muscle endurance were associated with low exercise self-efficacy. In the multidisciplinary counselling of patients with CHD older age should be considered. In addition, strategies that target muscle training may improve exercise self-efficacy, and thus enhance the general potential for being physically active in this population.

Authors' contributions

AB, CS and BJ designed this study, AB, CS, BJ and UT collected data, AB, CS and BJ analyzed the data and wrote the report. KW and UT was involved in critical revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the submitted article.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Funding

This work was supported by the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation (20150579), the Heart Foundation of Northern Sweden, the Swedish Heart and Lung Association (registration number: E143-15), Umeå University and the Västerbotten County Council.

Footnotes

The authors take responsibility for all aspects of the reliability and freedom from bias of the data presented and their discussed interpretation.

References

- 1.Hoffman J.I., Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002;39:1890–1900. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumgartner H., Bonhoeffer P., De Groot N.M., de Haan F., Deanfield J.E., Galie N. ESC guidelines for the management of grown-up congenital heart disease (new version 2010) Eur. Heart J. 2010;31:2915–2957. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith S.C., Jr., Jackson R., Pearson T.A., Fuster V., Yusuf S., Faergeman O. Principles for national and regional guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention: a scientific statement from the World Heart and Stroke Forum. Circulation. 2004;109:3112–3121. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133427.35111.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heran B.S., Chen J.M., Ebrahim S., Moxham T., Oldridge N., Rees K. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011;7 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001800.pub2. Cd001800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naci H., Ioannidis J.P. Comparative effectiveness of exercise and drug interventions on mortality outcomes: metaepidemiological study. BMJ. 2013;347 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kempny A., Dimopoulos K., Uebing A., Moceri P., Swan L., Gatzoulis M.A. Reference values for exercise limitations among adults with congenital heart disease. Relation to activities of daily life—single centre experience and review of published data. Eur. Heart J. 2012;33:1386–1396. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kröönström L.A., Johansson L., Zetterström A.K., Dellborg M., Eriksson P., Cider Å. Muscle function in adults with congenital heart disease. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014;170:358–363. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandberg C., Thilén U., Wadell K., Johansson B. Adults with complex congenital heart disease have impaired skeletal muscle function and reduced confidence in performing exercise training. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2015;22:1523–1530. doi: 10.1177/2047487314543076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bassareo P.P., Saba L., Solla P., Barbanti C., Marras A.R., Mercuro G. Factors influencing adaptation and performance at physical exercise in complex congenital heart diseases after surgical repair. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/862372. article ID 862372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dimopoulos K., Diller G.P., Piepoli M.F., Gatzoulis M.A. Exercise intolerance in adults with congenital heart disease. Cardiol. Clin. 2006;24:641–660. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2006.08.002. (vii) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gatzoulis M.A., Webb G.D., Daubeney P.E.F. 2nd ed. Elsevier Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 2011. Diagnosis and Management of Adult Congenital Heart Disease. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swan L., Hillis W.S. Exercise prescription in adults with congenital heart disease: a long way to go. Heart. 2000;83:685–687. doi: 10.1136/heart.83.6.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reybrouck T., Mertens L. Physical performance and physical activity in grown-up congenital heart disease. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabil. 2005;12:498–502. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000176510.84165.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaix M.A., Marcotte F., Dore A., Mongeon F.P., Mondesert B., Mercier L.A. Risks and benefits of exercise training in adults with congenital heart disease. Can. J. Cardiol. 2016;32:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandberg C., Engström K.G., Dellborg M., Thilén U., Wadell K., Johansson B. The level of physical exercise is associated with self-reported health status (EQ-5D) in adults with congenital heart disease. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2015;22:240–248. doi: 10.1177/2047487313508665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bandura A. W.H. Freeman; New York: 1997. Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Everett B., Salamonson Y., Davidson P.M. Bandura's exercise self-efficacy scale: validation in an Australian cardiac rehabilitation setting. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009;46:824–829. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hickey M.L., Owen S.V., Froman R.D. Instrument development: cardiac diet and exercise self-efficacy. Nurs. Res. 1992;41:347–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banks L., Rosenthal S., Manlhiot C., Fan C.S., McKillop A., Longmuir P.E. Exercise capacity and self-efficacy are associated with moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity in children with congenital heart disease. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2017;38:1206–1214. doi: 10.1007/s00246-017-1645-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroll T., Kehn M., Ho P.S., Groah S. The SCI exercise self-efficacy scale (ESES): development and psychometric properties. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2007;4:34. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahlström I., Hellström K., Emtner M., Anens E. Reliability of the Swedish version of the exercise self-efficacy scale (S-ESES): a test-retest study in adults with neurological disease. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2015;31:194–199. doi: 10.3109/09593985.2014.982776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erikssen G., Liestol K., Seem E., Birkeland S., Saatvedt K.J., Hoel T.N. Achievements in congenital heart defect surgery: a prospective, 40-year study of 7038 patients. Circulation. 2015;131:337–346. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012033. (discussion 46) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandberg C., Pomeroy J., Thilén U., Gradmark A., Wadell K., Johansson B. Habitual physical activity in adults with congenital heart disease compared with age- and sex-matched controls. Can. J. Cardiol. 2016;32:547–553. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rabin R., de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann. Med. 2001;33:337–343. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drummond M. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2005. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cider A., Carlsson S., Arvidsson C., Andersson B., Sunnerhagen K.S. Reliability of clinical muscular endurance tests in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2006;5:122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brage S., Brage N., Franks P.W., Ekelund U., Wareham N.J. Reliability and validity of the combined heart rate and movement sensor Actiheart. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005;59:561–570. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chase J.A. Physical activity interventions among older adults: a literature review. Res. Theory Nurs. Pract. 2013;27:53–80. doi: 10.1891/1541-6577.27.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moons P., Bovijn L., Budts W., Belmans A., Gewillig M. Temporal trends in survival to adulthood among patients born with congenital heart disease from 1970 to 1992 in Belgium. Circulation. 2010;122:2264–2272. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.946343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marelli A.J., Mackie A.S., Ionescu-Ittu R., Rahme E., Pilote L. Congenital heart disease in the general population: changing prevalence and age distribution. Circulation. 2007;115:163–172. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.627224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Budts W., Börjesson M., Chessa M., van Buuren F., Trigo Trindade P., Corrado D. Physical activity in adolescents and adults with congenital heart defects: individualized exercise prescription. Eur. Heart J. 2013;34:3669–3674. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dua J.S., Cooper A.R., Fox K.R., Graham Stuart A. Physical activity levels in adults with congenital heart disease. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabil. 2007;14:287–293. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32808621b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greutmann M., Le T.L., Tobler D., Biaggi P., Oechslin E.N., Silversides C.K. Generalised muscle weakness in young adults with congenital heart disease. Heart. 2011;97:1164–1168. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.213579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dua J.S., Cooper A.R., Fox K.R., Graham Stuart A. Exercise training in adults with congenital heart disease: feasibility and benefits. Int. J. Cardiol. 2010;138:196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]