Abstract

Primary lymphomas of the bone or skeletal muscle are rare. Three mechanisms of lymphomatous involvement of the muscle have been described, namely direct invasion from adjacent involved lymph nodes or bone, metastatic spread and, least commonly, primary muscle lymphoma. We herein present a rare case of primary mucle non-Hodgkin lymphoma with a description if the associated clinicopathological findings and a review of the relevant literature. A 41-year-old female patient was referred to our hospital with a painful mass in the right lower extremity. Following resection and histopathological examination, a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma originating from the muscle with cutaneous and subcutanenous infiltration was diagnosed. The patient received chemotherapy with six cycles of cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunomycin, oncovin and prednisone (CHOP regimen) and a complete radiological response was achieved after six cycles of treatment.

Keywords: primary skeletal muscle lymphoma, B-cell non-Hogkin lymphoma, CHOP chemotherapy

Introduction

Muscle enlargement may be due to a variety of benign conditions, such as exercise hypertrophy, infection, hemorrhage, myxoma and autoimmune diseases, and malignant conditions, including cancer metastasis and primary sarcoma or lymphoma (1).

Primary lymphomas of the bone or skeletal muscle are rare entities. The most frequent among these diseases are primary bone lymphomas, accounting for 3–5% of all bone tumors and 5% of all primary extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) (2). Three mechanisms of lymphomatous involvement of the muscle have been described: Direct invasion from adjacent involved lymph nodes or bone, metastatic spread and, least commonly, primary muscle lymphoma (1,3). The treatment of primary skeletal muscle lymphoma relies predominantly on the type of lymphoma and the prognosis of primary skeletal muscle lymphoma is generally poor (4).

We herein present a rare case of primary mucle NHL with a description of the associated clinicopathological findings and a review of the relevant literature.

Case report

A 41-year-old female patient was referred to Erzurum Regional Training and Research Hospital with a painful mass in the right lower extremity that was impeding walking. The patient was otherwise healthy, with no significant medical history. The physical examination revealed a painful hard mass with a lobulated contour, beginning in the proximal third of the right femur and extending to the semitendinosus and sartorius muscles distally. The left lower and bilateral upper extremities were normal on physical examination. All the laboratory tests were normal, apart from an elevated lactate dehydrogenase level of 1,055 U/l (normal range, 240–480 U/l).

The patient received en bloc resection of the mass, along with the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue of the distal lower right extremity. On histopathological examination, a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma originating from the muscle with cutaneous and subcutanenous infiltration was diagnosed. On immunohistochemical staining, the tumor cells were positive for CD20, CD79a, paired box protein Pax-5 and CD22, and negative for CD3, CD5, CD30, CD15 and cyclin-D1; the Ki-67 proliferation index was 50% (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Histopathological examination of the lesion confirmed the diagnosis of malignant lymphoma with large-cell infiltration. Hematoxylin and eosin staining; magnification, (A) ×10 and (B) ×40. (C) Immunohistochemical examination revealed positive CD20 staining; magnification, ×40.

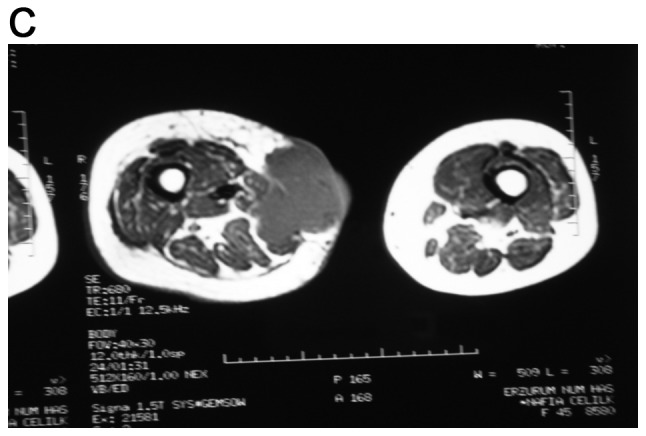

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lower extermities identified multiple solid masses with a lobulated contour at the medial and posterior part of the femur. The masses were infiltrating the gracilis and adductor magnus muscles and were extending to the semitendinosus and sartorius muscles distally and posteriorly, with cutaneous and subcutaneous fat invasion. The lesions were isointense to muscle on T1-weighted images (WI) and hyperintense on T2-WI. The size of all the lesions was 90×64×212 mm (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the patient's thigh. (A and B) Coronal sections and (C) axial section.

On lymphoma staging with contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) imaging of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, there was no evidence of lymphadenopathy. Bone marrow biopsy was performed and revealed a normocellular marrow with trilineage hematopoesis and no evidence of lymphoma.

The patient underwent chemotherapy with six cycles of cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunomycin, oncovin and prednisone (CHOP). CHOP chemotherapy was initially planned to be administered with rituximab (R-CHOP). However, after the first dose the patient developed an allergic reaction (fever, chills, flushing and nausea) to rituximab, which was thus excluded from the treatment. A complete radiological response was achieved after six cycles of treatment. A complete response was maintaned and the patient has remained disease-free for 1 year.

Discussion

Primary malignant lymphomas of soft tissues are rare (4). Primary skeletal muscle (PSM) NHL has rarely been reported (5,6). Lanham et al reviewed 75 cases of malignant lymphoma arising in soft tissue and reported the most common histological subtype to be large-cell type lymphoma (5). Travis et al reported 8 cases of primary mucle lymphoma among 7,000 malignant lymphomas (0.11%) diagnosed over a 10-year period (7). Elkouroshy et al reported an adult male patient diagnosed with primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the gluteal and adductor muscles, with aggressive bone involvement (8). Kounami et al had also reported an anaplastic cell lymphoma in a 14-year old female patient with a large left inguinal tumor (9). An increased frequency of PSM NHL (7%) was detected among AIDS-associated lymphomas (10). Approximately 25% of NHLs are extranodal (11). Komatsuda et al investigated a total of 2,147 patients between 1976–1978 and only found 31 primary muscle lymphomas in that series. Lymphomatous involvement of muscle has been reported to occur in 1.4% of all lymphoma cases, with 0.3% occuring in Hodgkin's disease and 1.1% in NHL (12). Primary NHLs originating from skeletal muscle may be misdiagnosed as soft tissue tumors, such as rhabdomyosarcoma, Ewing's sarcoma and metastasis to skeletal muscle (2).

A mass lesion may be identified on CT or MRI, but a definitive diagnosis can only be made by biopsy (4,6). Lee et al recommended that, in patients with a soft tissue mass, routine plain radiography and MRI should be performed prior to biopsy (3). Lim et al suggested that MRI is the most useful modality for assessment of muscular lymphoma (13). This condition most commonly affects skeletal muscles of the lower extremities, pelvis and gluteal regions. On CT, the mass may be iso- or hypodense (4). Suresh et al presented a report of MRI findings in 23 skeletal muscle lymphomas. In that report, all the tumors were of intermediate T1-WI signal intensity (SI), while 85% of the lesions also exhibited intermediate T2-WI SI (14). The majorty of these lymphomas have a B-cell immunophenotype. Two more reports of primary muscle lymphoma with a T-cell morphology were identified on Medline (15,16).

Primary NHLs originating in skeletal muscles are quite rare. Primary NHLs derived from lower limb soft tissues may be mistaken for metastatic tumors. The lesions may be identified on CT or/and MRI, but the definitive diagnosis relies on biopsy. In conclusion, masses of the extremities must be carefully assessed and a biopsy is recommended.

References

- 1.Kandel RA, Bédard YC, Pritzker KP, Luk SC. Lymphoma. Presenting as an intramuscular small cell malignant tumor. Cancer. 1984;53:1586–1589. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840401)53:7<1586::AID-CNCR2820530727>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ludwig K. Musculoskeletal lymphomas. Radiologe. 2002;42:988–992. doi: 10.1007/s00117-002-0824-0. (In German) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee VS, Martinez S, Coleman RE. Primary muscle lymphoma: Clinical and imaging findings. Radiology. 1997;203:237–244. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.1.9122401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beggs I. Primary muscle lymphoma. Clin Radiol. 1997;52:203–212. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9260(97)80274-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lanham GR, Weiss WS, Enzinger FM. Malignant lymphoma. A study of 75 cases presenting in soft tissue. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:1–10. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198901000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bozzola C, Boldorini R, Ramponi A, Monga G. Fine needle aspiration cytology in the diagnosis of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas of the muscle: A report of 2 cases. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:213–218. doi: 10.1159/000326137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Travis WD, Banks PM, Reiman HM. Primary extranodal soft tissue lymphoma of the extremities. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11:359–366. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198705000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elkourashy SA, Nashwan AJ, Alam SI, Ammar AA, El Sayed AM, Omri HE, Yassin MA. Aggressive lymphoma ‘Sarcoma Mimicker’ originating in the gluteus and adductor muscles: A case report and literature review. Clin Med Insights Case Rep. 2016;9:47–53. doi: 10.4137/CCRep.S39052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kounami S, Shibuta K, Yoshiyama M, Mitani Y, Watanabe T, Takifuji K, Yoshikawa N. Primary anaplastic large cell lymphoma of the psoas muscle: A case report and literature review. Acta Haematol. 2012;127:186–188. doi: 10.1159/000335744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raphael M, Gentilhomme O, Tulliez M, Byron PA, Diebold J. Histopathologic features of high-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphomas in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. The French study group of pathology for human immunodeficiency virus-associated tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1991;115:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman C, Berg JW, Cutler SJ. Occurrence and prognosis of extranodal lymphomas. Cancer. 1972;29:252–260. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197201)29:1<252::AID-CNCR2820290138>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Komatsuda M, Nagao T, Arimori S. An autopsy case of malignant lymphoma associated with remarkable infiltration in skeletal muscles (author's transl) Rinsho Ketsueki. 1981;22:891–895. (In Japanese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim CY, Ong KO. Imaging of musculoskeletal lymphoma. Cancer Imaging. 2013;13:448–457. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2013.0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suresh S, Saifuddin A, O'Donnell P. Lymphoma presenting as a musculoskeletal soft tissue mass: MRI findings in 24 cases. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:2628–2634. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-1014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alekshun TJ, Rezania D, Ayala E, Cualing H, Sokol L. Skeletal muscle peripheral T-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:501–503. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robaday S, Héron F, Girszyn N, Humbrecht C, Levesque H, Marie I. Muscle lymphoma: A case report. Rev Med Interne. 2008;29:837–839. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2008.01.019. (In French) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]