Abstract

Cancer initiating cell (CIC) formation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) are pivotal events in lung cancer cell invasion and metastasis. They have been shown to occur in gefitinib resistance. Studying the molecular mechanisms of CICs, EMT and acquired gefitinib resistance will enhance the understanding of the pathogenesis and progression of the disease and offer novel targets for effective therapies. TWIK-related acid-sensitive K(+) (TASK-1) is expressed in a subset of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines, where it promotes cell proliferation while inhibiting apoptosis. In the present study, TASK-1 was demonstrated to induce gefitinib resistance in the A549 NSCLC cell line. Overexpression of TASK-1 promoted the acquisition of CIC-like traits by A549 cells. CD133, octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (OCT-4) and Nanog have been suggested to be markers of CICs in lung cancer. It was demonstrated that overexpression of TASK-1 promoted CD133, OCT-4 and Nanog protein expression in A549 cells. Increased formation of stem cell-like populations results in EMT of cancer cells. The present study found that overexpression of TASK-1 promoted EMT of A549 cells. Thus, downregulation of TASK-1 may represent a novel strategy for EMT reversal, decreasing CIC-like traits and increasing gefitinib sensitivity of NSCLCs.

Keywords: cancer initiating cells, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, lung cancer, TASK-1

Introduction

Lung cancer is a heterogeneous malignancy with aggressive phenotypes (1,2). Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for ~85% of lung cancer cases (2). Lung cancers harboring somatic mutations in exons encoding the tyrosine kinase domain of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) exhibit a significant tumor regression when treated with the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) gefitinib or erlotinib in ~70% of cases (3–5). However, acquired resistance inevitably develops in an overwhelming majority of these patients.

Epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) is associated with the acquired resistance of NSCLC to gefitinib (6,7). It is a process by which cells undergo a morphological shift from the epithelial polarized to the mesenchymal fibroblastoid phenotype. EMT has been recognized to have pivotal roles in several diverse processes during embryonic development, chronic inflammation and fibrosis, as well as tumor progression (8–11). During EMT, epithelial cells lose their defined cell-cell/cell-substratum contacts and their structural/functional polarity, and become spindle-like.

Lung cancer stem cells (CSCs) or cancer-initiating cells (CICs) have been identified and demonstrated to constitute a primitive cell population capable of self-renewal and differentiation that have the unique capacity to give rise to new tumors upon serial transplantation (12–15). They represent a small population of undifferentiated tumorigenic cells responsible for tumor initiation, maintenance and spreading. Resistance to conventional chemotherapeutic drugs is a common characteristic of CICs (16). It has been reported that lung CICs were associated with gefitinib resistance (17).

TWIK-related acid-sensitive K(+) (TASK-1) is expressed in a subset of NSCLCs, where it is functional, and promoted the proliferation and inhibited apoptosis in a highly TASK-1-expressing lung cancer cell line (18). The present study demonstrated that TASK-1 induced gefitinib resistance in NSCLC A549 cells. Overexpression of TASK-1 promoted the formation of CICs in A549 cells. CD133, octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (OCT-4) and Nanong have been proposed as markers of CICs in lung cancer (13,19,20). The present study demonstrated that overexpression of TASK-1 promoted CD133, OCT-4 and Nanong protein expression in A549 cells. Increased formation of CSC-like populations may result in EMT of cancer cells (21–24). The present study found that overexpression of TASK-1 promotes EMT of A549 cells.

Materials and methods

Cell line and culture

The A549 NSCLC cell line was purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) within 3 months of performing the experiments. They were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (both Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and antibiotics (100 mg/ml penicillin and 100 U/ml streptomycin) in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C.

Cell transfection

The pGCMV/EGFP/TASK-1 plasmid and the pGCMV/EGFP/Neo plasmid were constructed (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). The two plasmids were transfected into A549 NSCLC cells separately using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). In order to detect the transfection efficiency of the plasmids, green fluorescent signal was measured by fluorescence microscopy. Subsequent experimentation was performed after 24 h.

Western blot analysis

Total proteins in cells were extracted using protein lysis solution (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.). Protein concentration was measured using a bicinchoninic acid kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.). Protein extracts (50 µg/lane) were resolved through 8% SDS-PAGE, transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) and blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were probed with antibodies against human TASK-1 (ab135883), vimentin (ab92547), E-cadherin (ab40772), CD133 (ab16518), OCT4 (ab109183), Nanog (ab109250), matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)9 (ab76003), MMP2 (ab92536) or β-actin (ab8227) (all 1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) at 4°C overnight. Membranes were then incubated with anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:500; ab218695; Abcam) for 1 h at room temperature. An enhanced chemiluminescence system (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to detect the antibody binding.

Sphere formation assay

Cells were seeded at 2.5×104 cells/well on 0.5% agar pre-coated 6-well plates. After 1 week, half the medium was exchanged every third day. After a total of 14 days, single spheres were picked and counted (25). Sphere formation efficiency was calculated by dividing the total number of spheres formed by the total number of live cells seeded multiplied by hundred.

MTT assay

To monitor resistance to gefitinib, A549 cells were treated with gefitinib (purity >99%; AstraZeneca, Cambridge, UK) at different concentrations for 24 h. An MTT assay was performed as described previously (2). Data were analyzed with the software Origin 7.5 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA) to fit a sigmodial curve. The IC50 was the gefitinib concentration that reduced the number of viable cells by 50%.

Immunofluorescence staining

Cells seeded on glass coverslips in 6-well plates were fixed in 4% formaldehyde solution for 30 min at room temperature and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton-X-100/PBS. Cells were blocked with 5% BSA-PBS (BSA from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with primary antibodies against E-cadherin (1:500; ab92547; Abcam) or vimentin (1:500; ab40772; Abcam) at 4°C overnight. Cells were then incubated with rhodamine- or fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500; ab150077; Abcam) for 1 h at room temperature. The coverslips were counterstained with DAPI and imaged under a confocal microscope (TCS SP5; Lecia Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Wound healing assay

Cells (5×105) were seeded onto each 35-mm glass bottom dish (MatTek Co., Ashland, MA, USA) and cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 h. The confluent monolayer of cells was wounded with yellow 200 µl pipette tips (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.). After washing with warm PBS, the cells were incubated in fresh serum-free culture medium. Images of the wounded areas were captured at different time-points with an inverted microscope (Eclipse TE-2000U; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a video camera (DS-U1; Nikon). Results were examined at five randomly selected fields in each field, at ×20 magnification. The wound areas were calculated by ImageJ 1.43b software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Statistical analysis

Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean. SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the analysis of experimental data. Student's t-test (two-tailed) was used for comparison between two groups. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

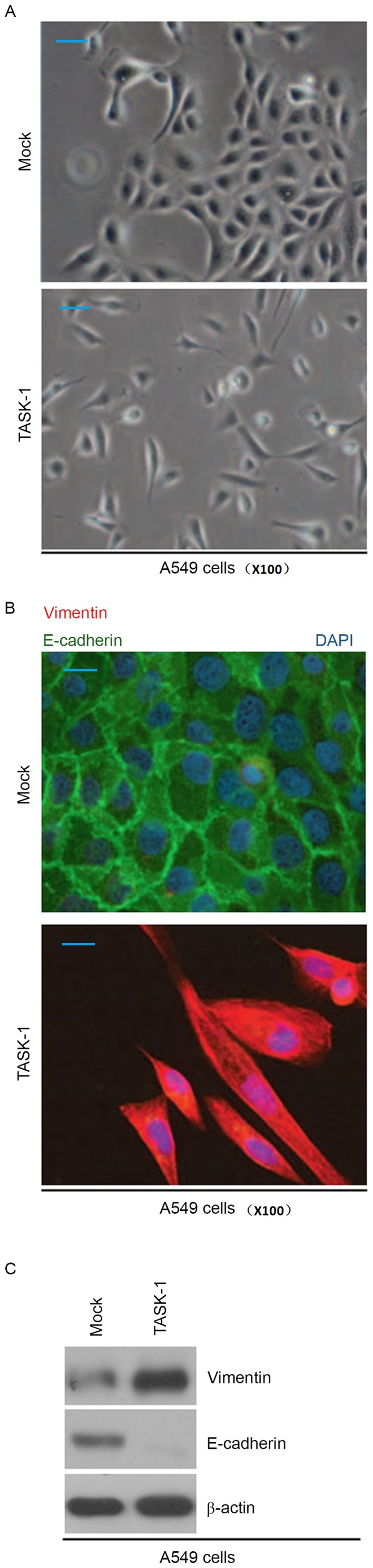

Overexpression of TASK-1 promotes gefitinib resistance

In order to confirm the efficiency of plasmid-mediated TASK-1-expression, A549 cells transfected with TASK-1-expressing plasmid and empty vector were subjected to western blot analysis. The results showed that TASK-1 protein was significantly upregulated in A549 cells transfected with TASK-1-expressing plasmid (Fig. 1A). To further identify whether TASK-1 affected the efficacy of gefitinib in A549 cells, A549 cells transfected with TASK-1-expressing plasmids or empty vector were subjected to an MTT assay (Fig. 1B). The results demonstrated that TASK-1 transformed native, gefitinib-sensitive A549 cells into gefitinib-resistant A549 cells, suggesting that its overexpression induced gefitinib resistance (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Overexpression of TASK-1 promotes gefitinib resistance. (A) Western blot analysis of TASK-1 in A549 cells. β-actin was used as a loading control. (B) MTT cell viability assay. A549 cells transfected with TASK-1 expressing plasmids or empty vector (mock) were untreated or treated with gefitinib. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n=3). TASK-1, TWIK-related acid-sensitive K(+).

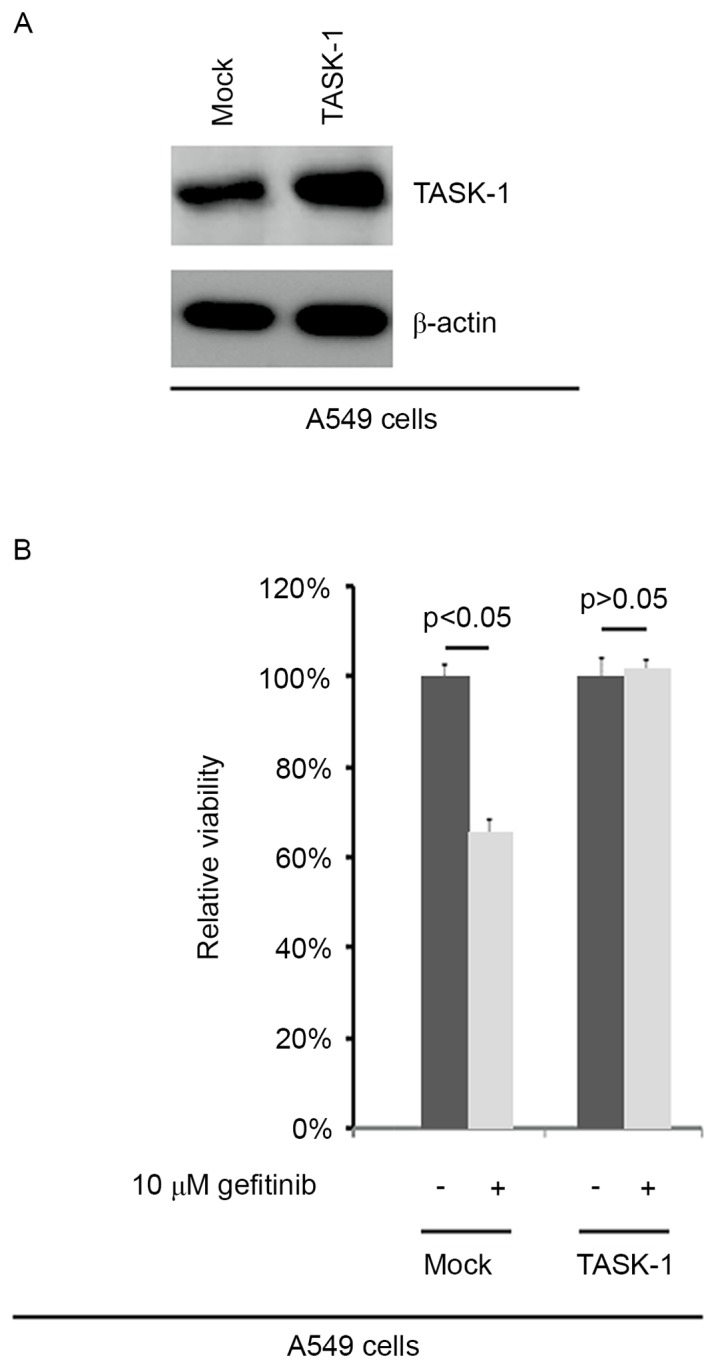

TASK-1 gives A549 cells CIC-like traits

In order to identify whether TASK-1 affects CIC-like traits in A549 cells, a sphere formation assay was performed to assess the capacity of A549 cells for self renewal, which is associated with CICs and CSCs. The results demonstrated that after 14 days of culture TASK-1-overexpressing cells formed bigger spheres than control cells, indicating markedly increased CIC-like traits provided by the TASK-1-expressing plasmids (Fig. 2A). To identify whether TASK-1 regulates CD133, OCT-4 and Nanog protein expression, western blot analysis of A549 cells transfected with TASK-1-expressing plasmids and empty vector was performed. The results revealed that CD133, OCT-4 and Nanog protein were upregulated in A549 cells by TASK-1 (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

TASK-1 induces formation of CIC phenotypes in A549 cells. (A) Sphere growth of A549 cells transfected with TASK-1-expressing plasmids and empty vectors (mock) (scale bar, 100 µm). (B) Western blot analysis of CD133, OCT-4 and Nanog in A549 cells transfected with TASK-1-expressing plasmids and empty vectors (mock). β-actin was used as a loading control. Representative images of triplicate experiments are shown. TASK-1, TWIK-related acid-sensitive K(+); OCT-4, octamer-binding transcription factor 4.

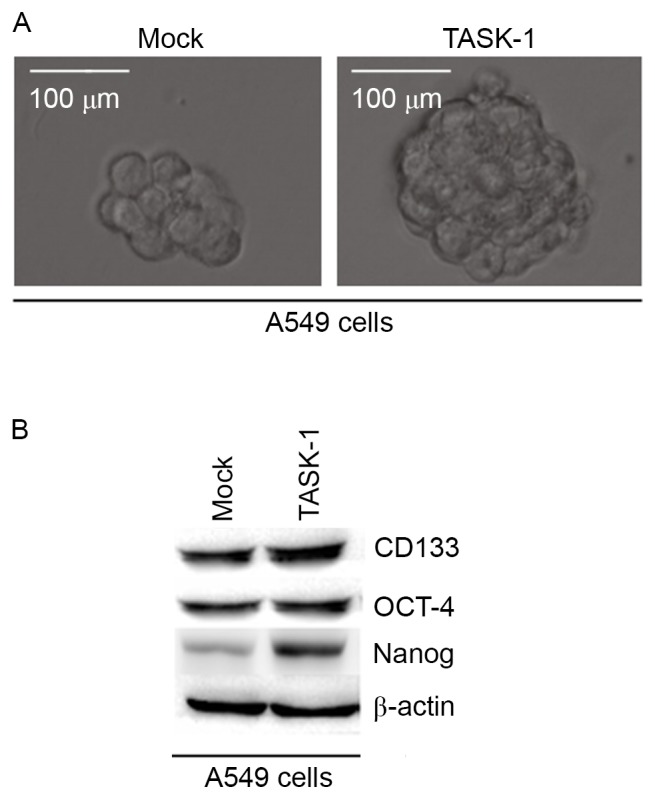

TASK-1 induces EMT in A549 cells

Cell morphological observation revealed that overexpression of TASK-1 induced EMT phenotypes in A549 cells (transition from a cobblestone-like to a spindle-like morphology; Fig. 3A). In order to detect whether TASK-1 affects E-cadherin (epithelial marker) and vimentin (mesenchymal marker) protein, immunofluorescence analysis of A549 cells transfected with TASK-1 and empty vector was performed. It was found that overexpression of TASK-1 promoted vimentin expression and inhibited E-cadherin expression in A549 cells (Fig. 3B). Western blot analysis was also performed to detect E-cadherin and vimentin protein in A549 cells transfected with TASK-1 and empty vector. The results revealed that vimentin protein is upregulated, while E-cadherin is downregulated in A549 cells transfected with TASK-1 overexpression vector (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

TASK-1 induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition of A549 cells. (A) Phase-contrast microscopy images of A549 cells transfected with TASK-1-expressing plasmids and empty vectors (mock). Scale bar=100 µm. (B) Immunofluorescence analyses for vimentin and E-cadherin in A549 cells transfected with TASK-1-expressing plasmids and empty vectors (mock). The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar=100 µm. (C) Western blot analysis of vimentin and E-cadherin in A549 cells transfected with TASK-1 expressing plasmids and empty vectors (mock). β-actin was used as a loading control. Representative images of triplicate experiments are shown. TASK-1, TWIK-related acid-sensitive K(+).

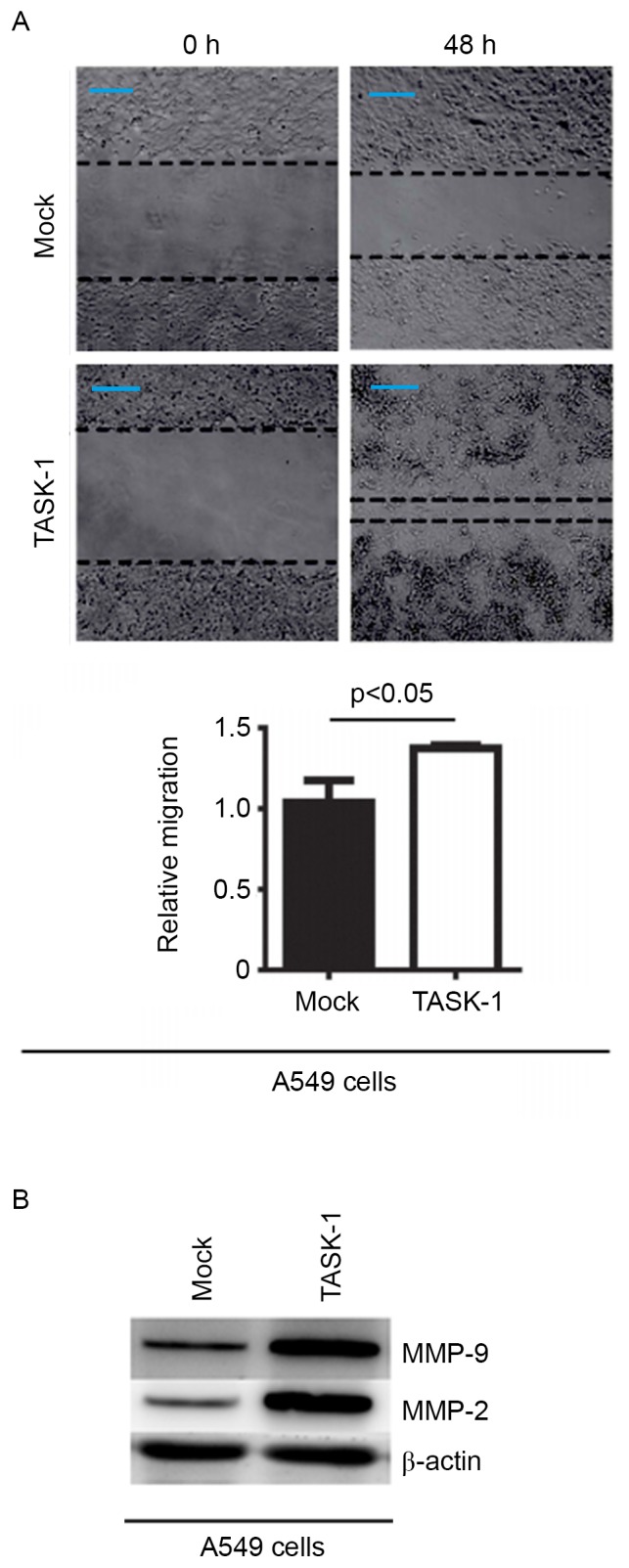

Overexpression of TASK-1 promotes migration of A549 cells

In an attempt to identify the role of TASK-1 in regulating the migration of A549 cells, a would healing assay was performed to detect the migration of A549 cells transfected with TASK-1-expressing plasmid and empty vector. Overexpression of TASK-1 was found to promote the migration in the cells (Fig. 4A). In order to detect whether TASK-1 affects MMP-2 and MMP-9 protein expression, western blot analysis of A549 cells transfected with TASK-1 and empty vector was performed. It was revealed that expression of TASK-1 promotes MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression in A549 cells (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Overexpression of TASK-1 promotes migration of A549 cells. (A) Wound-healing assay of A549 cells transfected with TASK-1-expressing plasmids and empty vectors (mock). Images of the cell monolayers were captured directly after scraping and subsequent to 48 h of incubation. The wound healing rate was quantified by detecting the percentage of wound closure vs. that of the original wound. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n=3). Scale bar=100 µm. (B) Western blot analysis of MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression in A549 cells transfected with TASK-1-expressing plasmids and empty vectors (mock). β-actin was used as a loading control. Representative images of triplicate experiments are shown. MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; TASK-1, TWIK-related acid-sensitive K(+).

Discussion

NSCLC patients with early-stage disease are treated by surgery, and 30–60% develop recurrent tumors, which results in mortality (26,27). Chemotherapeutic agents, including gemcitabine, platinum compounds and taxanes, improve survival to a limited extent, but overall survival rates remain low due to recurrence of more aggressive, drug-resistant tumors (28,29). NSCLC in non-smokers predominantly has mutations in EGFR (30); such patients respond well to EGFR inhibitors such as gefitinib, but eventually develop resistance and succumb to the disease (31). The recurrence may be local or metastatic, and commonly occurs after a period of clinical dormancy. Resistance to EGFR inhibitors occurs through various mechanisms, including the appearance of a T790M gatekeeper mutation, expression of the c-Met gene or activation of alternate signaling pathways (32,33). Development of strategies to combat resistance to EGFR inhibitors in NSCLC will provide an immense benefit to a large number of patients (34).

A recent study reported that knockdown of TASK-1 by small interfering RNA significantly enhanced apoptosis and reduced proliferation in A549 cells (18). For the first time, to the best of our knowledge, the present study demonstrated that overexpression of TASK-1 induced gefitinib resistance in A549 cells, implying that TASK-1 may represent a novel target to reverse gefitinib resistance.

Resistance to radiation therapies and conventional chemotherapeutic drugs is a common characteristic of CSCs (35–37). It has been reported that aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member A1 (ALDH1A1)-positive CSCs promote gefitinib resistance in lung cancer (17). The present study found that overexpression of TASK-1 promoted A549 cells to adopt CIC-like properties. In addition, overexpression promoted CD133, OCT-4 and Nanog protein expression in A549 cells, indicating that TASK-1 induces the development of CIC-like traits. However, it remains elusive whether TASK-1 promotes the formation of ALDH1A1-positive lung CICs.

Increased formation of a CIC population may result in EMT of cancer cells and EMT has been shown to contribute to the formation of CIC-like characteristics (38). It has been suggested that the reversal of the EMT phenotype potentially enhances the sensitivity of lung cancer cells to gefitinib (39). Consistent with these results, the present study demonstrated that overexpression of TASK-1 induced EMT of A549 cells. The degradation of ECM and the destruction of basement membrane are prerequisites for tumor infiltration and metastasis (40). Tumor cells must have the ability to degrade ECM and basement membranes, and this degradation process depends on proteolytic enzymes, mainly serine-degrading enzymes, cysteine proteases and MMPs. MMPs are considered to be the most important. MMP2 and MMP9 are important members of the MMP family, encoding 72 KDa gelatinase A and 92 KDa gelatinase B, respectively, which have a partial co-acting substrate that degrades the major constituents of the basement membrane IV type collagen. This is conducive to the migration of tumor cells (41,42).

In conclusion, the results of the present study provided strong molecular evidence demonstrating that TASK-1 promotes gefitinib resistance, EMT and CIC-like properties of NSCLCs. Thus, downregulation of TASK-1 appears to be a novel strategy for the reversal of the EMT, decreasing CIC-like traits and increasing gefitinib sensitivity of NSCLCs.

References

- 1.Ding L, Getz G, Wheeler DA, Mardis ER, McLellan MD, Cibulskis K, Sougnez C, Greulich H, Muzny DM, Morgan MB, et al. Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2008;455:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature07423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanders HR, Albitar M. Somatic mutations of signaling genes in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;203:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2010.07.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costa DB, Kobayashi S, Tenen DG, Huberman MS. Pooled analysis of the prospective trials of gefitinib monotherapy for EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancers. Lung Cancer. 2007;58:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller VA, Riely GJ, Zakowski MF, Li AR, Patel JD, Heelan RT, Kris MG, Sandler AB, Carbone DP, Tsao A, et al. Molecular characteristics of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, bronchioloalveolar carcinoma subtype, predict response to erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1472–1478. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackman DM, Miller VA, Cioffredi LA, Yeap BY, Jänne PA, Riely GJ, Ruiz MG, Giaccone G, Sequist LV, Johnson BE. Impact of epidermal growth factor receptor and KRAS mutations on clinical outcomes in previously untreated non-small cell lung cancer patients: Results of an online tumor registry of clinical trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5267–5273. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rho JK, Choi YJ, Lee JK, Ryoo BY, Na II, Yang SH, Kim CH, Lee JC. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition derived from repeated exposure to gefitinib determines the sensitivity to EGFR inhibitors in A549, a non-small cell lung cancer cell line. Lung Cancer. 2009;63:219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li D, Zhang L, Zhou J, Chen H. Cigarette smoke extract exposure induces EGFR-TKI resistance in EGFR-mutated NSCLC via mediating Src activation and EMT. Lung Cancer. 2016;93:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grünert S, Jechlinger M, Beug H. Diverse cellular and molecular mechanisms contribute to epithelial plasticity and metastasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:657–665. doi: 10.1038/nrm1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalluri R, Neilson EG. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its implications for fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1776–1784. doi: 10.1172/JCI200320530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and pathologies. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:740–746. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:442–454. doi: 10.1038/nrc822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pine SR, Marshall B, Varticovski L. Lung cancer stem cells. Dis Markers. 2008;24:257–266. doi: 10.1155/2008/396281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eramo A, Lotti F, Sette G, Pilozzi E, Biffoni M, Di Virgilio A, Conticello C, Ruco L, Peschle C, De Maria R. Identification and expansion of the tumorigenic lung cancer stem cell population. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:504–514. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim CF, Jackson EL, Woolfenden AE, Lawrence S, Babar I, Vogel S, Crowley D, Bronson RT, Jacks T. Identification of bronchioalveolar stem cells in normal lung and lung cancer. Cell. 2005;121:823–835. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang F, Qiu Q, Khanna A, Todd NW, Deepak J, Xing L, Wang H, Liu Z, Su Y, Stass SA, Katz RL. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 is a tumor stem cell-associated marker in lung cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:330–338. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dean M, Fojo T, Bates S. Tumour stem cells and drug resistance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:275–284. doi: 10.1038/nrc1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang CP, Tsai MF, Chang TH, Tang WC, Chen SY, Lai HH, Lin TY, Yang JC, Yang PC, Shih JY, Lin SB. ALDH-positive lung cancer stem cells confer resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Cancer Lett. 2013;328:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leithner K, Hirschmugl B, Li Y, Tang B, Papp R, Nagaraj C, Stacher E, Stiegler P, Lindenmann J, Olschewski A, et al. TASK-1 regulates apoptosis and proliferation in a subset of non-small cell lung cancers. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen YC, Hsu HS, Chen YW, Tsai TH, How CK, Wang CY, Hung SC, Chang YL, Tsai ML, Lee YY, et al. Oct-4 expression maintained cancer stem-like properties in lung cancer-derived CD133-positive cells. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2637. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiou SH, Wang ML, Chou YT, Chen CJ, Hong CF, Hsieh WJ, Chang HT, Chen YS, Lin TW, Hsu HS, Wu CW. Coexpression of Oct4 and nanog enhances malignancy in lung adenocarcinoma by inducing cancer stem cell-like properties and epithelial-mesenchymal transdifferentiation. Cancer Res. 2010;70:10433–10444. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurrey NK, Jalgaonkar SP, Joglekar AV, Ghanate AD, Chaskar PD, Doiphode RY, Bapat SA. Snail and slug mediate radioresistance and chemoresistance by antagonizing p53-mediated apoptosis and acquiring a stem-like phenotype in ovarian Cancer cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2059–2068. doi: 10.1002/stem.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, Eaton EN, Ayyanan A, Zhou AY, Brooks M, Reinhard F, Zhang CC, Shipitsin M, et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:704–715. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morel AP, Lièvre M, Thomas C, Hinkal G, Ansieau S, Puisieux A. Generation of breast cancer stem cells through epithelial-mesenchymal transition. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santisteban M, Reiman JM, Asiedu MK, Behrens MD, Nassar A, Kalli KR, Haluska P, Ingle JN, Hartmann LC, Manjili MH, et al. Immune-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition in vivo generates breast cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2887–2895. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tiran V, Stanzer S, Heitzer E, Meilinger M, Rossmann C, Lax S, Tsybrovskyy O, Dandachi N, Balic M. Genetic profiling of putative breast cancer stem cells from malignant pleural effusions. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0175223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demicheli R, Fornili M, Ambrogi F, Higgins K, Boyd JA, Biganzoli E, Kelsey CR. Recurrence dynamics for non-small-cell lung cancer: Effect of surgery on the development of metastases. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:723–730. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31824a9022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Senthi S, Lagerwaard FJ, Haasbeek CJ, Slotman BJ, Senan S. Patterns of disease recurrence after stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for early stage non-small-cell lung cancer: A retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:802–809. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sève P, Dumontet C. Chemoresistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Curr Med Chem Anticancer Agents. 2005;5:73–88. doi: 10.2174/1568011053352604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lara PN, Jr, Lau DH, Gandara DR. Non-small-cell lung cancer progression after first-line chemotherapy. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2002;3:53–58. doi: 10.1007/s11864-002-0041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun S, Schiller JH, Gazdar AF. Lung cancer in never smokers-a different disease. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:778–790. doi: 10.1038/nrc2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brugger W, Thomas M. EGFR-TKI resistant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): New developments and implications for future treatment. Lung Cancer. 2012;77:2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nurwidya F, Takahashi F, Murakami A, Kobayashi I, Kato M, Shukuya T, Tajima K, Shimada N, Takahashi K. Acquired resistance of non-small cell lung cancer to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Respir Investig. 2014;52:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wangari-Talbot J, Hopper-Borge E. Drug resistance mechanisms in non-small cell lung carcinoma. J Can Res Updates. 2013;2:265–282. doi: 10.6000/1929-2279.2013.02.04.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chong CR, Jänne PA. The quest to overcome resistance to EGFR-targeted therapies in cancer. Nat Med. 2013;19:1389–1400. doi: 10.1038/nm.3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou BB, Zhang H, Damelin M, Geles KG, Grindley JC, Dirks PB. Tumour-initiating cells: Challenges and opportunities for anticancer drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:806–823. doi: 10.1038/nrd2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frank NY, Schatton T, Frank MH. The therapeutic promise of the cancer stem cell concept. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:41–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI41004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J, Wakeman TP, Lathia JD, Hjelmeland AB, Wang XF, White RR, Rich JN, Sullenger BA. Notch promotes radioresistance of glioma stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:17–28. doi: 10.1002/stem.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Polyak K, Weinberg RA. Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states: Acquisition of malignant and stem cell traits. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:265–273. doi: 10.1038/nrc2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie M, Zhang L, He CS, Xu F, Liu JL, Hu ZH, Zhao LP, Tian Y. Activation of notch-1 enhances epithelial-mesenchymal transition in gefitinib-acquired resistant lung cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113:1501–1513. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hirvonen R, Talvensaari-Mattila A, Pääkkö P, Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) in T(1–2)N0 breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;77:85–91. doi: 10.1023/A:1021152910976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kalhori V, Törnquist K. MMP2 and MMP9 participate in S1P-induced invasion of follicular ML-1 thyroid cancer cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;404:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu B, Cui J, Sun J, Li J, Han X, Guo J, Yi M, Amizuka N, Xu X, Li M. Immunolocalization of MMP9 and MMP2 in osteolytic metastasis originating from MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14:1099–1106. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]