Abstract

The impact of illicit drug markets on the occurrence of violence varies tremendously depending on many factors. Over the last years, Mexico and the USA have increased security border issues that included many aspects of drug-related trade and criminal activities. Mexico experienced only a small reduction in trauma deaths after the enforcement of severe crime reinforcement policies. This strategy in the war on drugs is shifting the drug market to other Central American countries. This phenomenon is called the ballooning effect, whereby the pressure to control illicit drug-related activities in one particular area forces a shift to other more vulnerable areas that leads to an increase in crime and violence. A human rights crisis characterized by suffering, injury, and death related to drug trafficking continues to expand, resulting in the exorbitant loss of lives and cost in productivity across the continent. The current climate of social violence in Central America and the illegal immigration to the USA may be partially related to this phenomenon of drug trafficking, gang violence, and crime. A health care initiative as an alternative to the current war approach may be one of the interventions needed to reduce this crisis.

Keywords: Drug trafficking, Violence, USA, Mexico, Trauma, Injury

Introduction

The trade of psychoactive and other drugs has existed since ancient times. The criminalization of drug possession and trade most likely occurred during the Middle Ages, and such prohibitive legislation has continued to the present day [1]. Illegal drug trafficking is a global black market. The impact of this market on the occurrence and magnitude of violence varies tremendously depending on many factors including the socioeconomic and cultural background of the countries and the regions affected by it [2]. The suffering, caused by the whole spectrum of “illegal drugs,” is tremendously diverse and affects all socioeconomic levels, and it demands the implementation of a wide range of interventions, not simply criminal penalization [2]. In this narrative review, the association between violence and the illicit drug trade in Mexico and the USA is analyzed, including its impact on the human crisis at the border and in neighboring regions.

The Context of Violence and Illicit Drug Trade in Mexico

In the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, drugs such as marijuana, opiates, and cocaine were commonly used in Mexico, predominantly for medical reasons [3]. Opium derivatives such as morphine and heroin, and pharmaceuticals such as cocaine, coca wines, and marijuana cigarettes, were prescribed by doctors and easily obtained in pharmacies, popular markets, and even hardware stores. The cultivation of opium in Mexico began during the latter part of the 19th century, primarily in northwestern states like Sinaloa, Sonora, Chihuahua, and Durango [3]. With increased consumption within the Mexican population, authorities put in place regulations to ensure improved production quality in an attempt to protect the consumers. However, the Mexican government at that time did not deem it necessary to prohibit the production and use of these drugs. The implementation of drug prohibition in the USA in the 1920s created ideal conditions for drug trafficking, with legal commerce on one side of the USA-Mexico border and prohibition on the other [3]. In 1917, the Mexican congress passed an amendment that prohibited the trade of opium, morphine, ether, cocaine, and marijuana under pressure from the US government. The key reasoning for outlawing the commerce of these substances was that they were deemed “noxious to health.” Despite these obstacles, the illicit drug trade continued to grow, with much of the smuggling activity taking place via Mexicali and Tijuana in the Baja California territory. In the 1930s, as a response to the passing of the USA marijuana tax act, marijuana production increased substantially in Mexico [3]. In 1947, the Mexican government created the Federal Security Agency, a police force with power to intervene in drug-related issues. The initial investigations of the agency revealed that several politicians within the border regions were directly involved in, and in some cases even in control of, the illegal trafficking businesses. In most border cities, the individuals involved in the drug trade were merchants, including people from all social classes. Later, these individuals and their future generations succeeded in establishing a drug-trafficking dynasty that allowed their illicit businesses to grow and spread nationwide [3]. It was estimated that by the 1960s there were approximately 300 clandestine airfields in Northern Mexico, making the country extremely appealing to the Colombian cartels that were looking for a suitable center for distribution to the USA. By the late 1970s the drug-trafficking business in Mexico and its related violence had grown dramatically in collaboration with the Colombian cartels. Regular confrontations began between rival trafficking groups and also against the police within urban areas of several cities. The trade of marijuana from Mexico to the USA was further enhanced by the demands of some soldiers addicted to drugs returning from war areas in the Far East [3].

Faced with the increasing influx of illicit drugs into the USA from Mexico, President Nixon's government launched a plan for rigorous inspection of vehicles crossing the border [2]. Around the same time, the Mexican government initiated a series of military operations against the drug traffickers and their plantations, destroying tons of drugs. However, despite these actions, drugs continued to flow into the US market as Colombian marijuana replaced Mexican marijuana and the business relationship between the “cartels” of both countries began to flourish. This alliance resulted in an era of unparalleled success for drug trafficking, fueled by the increasing demand for Andean cocaine during the 1980s and the 1990s [3, 4, 5].

The US “war on drugs” policy attempted to tackle the trafficking problems within Mexico. Mexican cartels including the “Sinaloa” and the “Tijuana” cartels were prosecuted. Despite these apparent successes, drug-related violence increased, largely as a result of the new strategies used by traffickers following the dissolution of the Colombian cartels [5]. Mexico now serves as the new stage for the war on drugs. US authorities have estimated that close to 90% of the cocaine entering the country crossed the USA-Mexico land border [6]. Mexico is currently experiencing a situation comparable to that of Colombia two decades ago, with increased violence, kidnappings, and murders, and a rampant increase in crime, with two critical disadvantages [5]. Firstly, the government is attempting to tackle a social problem, whose participants infect different levels of the country's social spectrum with corruption, bloody intimidating behavior, and a total disregard for authority. Second, the territory of Mexico is extensive and is more difficult to control, with expansion into less organized countries on the extremely vulnerable south region due to a poor socioeconomic status leading to public insecurity worsened by limited law enforcement institutions [6].

Drug-Related Violence and Injuries in Mexico

The first national addiction survey in Mexico was conducted in 1988 [3]. Marijuana, inhalants, and tranquilizers were the most commonly used drugs, along with tobacco and alcohol. Compared to the consumption in the USA, the prevalence in Mexico was less than one tenth for each drug and age group [3]. In a more recent survey conducted in an emergency room in Mexico City, 7.5% of the patients reported illicit drug use during the preceding twelve months, with marijuana and cocaine being the most frequently used (i.e., 66 and 38%, respectively) [7, 8]. Drug-related violence is a major problem in Mexico, with official figures reporting the occurrence of approximately 28,000 drug-related killings in the past 4 years [9]. Between January and September of 2009, there were 5,874 drug-related murders in Mexico, an increase of almost 5% over the same period the previous year [10]. Agovernment analysis of the 6,000 people who died in 2008 as a result of organized crime violence revealed that 9 out of 10 of those deaths involved either individuals associated with the drug trade or law enforcement officials [11, 12]. In 2008, the Mérida Initiative was started as a plan to support the Mexican war against drugs, including the war in other Central American countries [4]. Close to USD 1.4 billion were offered to reinforce and bring technical assistance to the law enforcement in Mexico. Under this plan, fourteen new prisons were built, with a capacity of 20,000 prisoners/prison. According to government sources, crime related to drug-trafficking peaked in 2007, and it has been decreasing since 2008 [13]. Forty-six percent of the Mexican population is considered poor and at least 28% is considered as socially vulnerable to extreme poverty. A report of 2012 showed that at least 11.5 million Mexican citizens did not have enough income to cover basic social needs such as health, a home, education, and food [14]. According to studies in Mexico, the number of homicides grew from 8,867 in 2007 to 27,199 in 2011 [15]. In 2010 and 2011, violence-related to drug-trafficking was associated with 63.4 and 53.8% of the total intentional deaths in Mexico [15]. The increased risk and intensity of violence and its relation to the proximity to the USA-Mexico border was exemplified by the fact that the border city of Juárez was the scene of more than one fifth of recent drug-related murders [15]. In 2012, drug trafficking and organized crime style homicides were most concentrated in the central and eastern border region, as well as in central Pacific coast states [15].

The Context of Violence and Illicit Drug Trade in the USA

The first law prohibiting the use of a specific drug in the USA was a San Francisco ordinance that banned the smoking of opium in 1875 but not other forms of opium consumption [16]. This was followed by other laws throughout the country and federal laws which barred Chinese people from trafficking in opium [16, 17]. Though the laws affected the use and distribution of opium by Chinese immigrants, no action was taken against the producers of such products as tincture of opium and alcohol, commonly taken as a medicine by US citizens [16, 17]. Between 150,000 and 200,000 opiate addicts lived in the USA in the late 19th century, and approximately three-quarters of these addicts were women who had been given the drug by physicians or pharmacists for the relief of painful menstruation [17]. In the USA, the road to prohibition of cocaine began in the early part of the twentieth century. Newspapers began reporting stories of “cocaine addicts' violent behavior” and creating a national sense of panic. This public concern culminated in the passing of the Harrison Act in 1914, which required sellers of opiates and cocaine to apply for a license [16, 17]. Although its original purpose was to create paper trails of drug transactions between doctors, drug stores, and patients, the Harrison Act soon became a prohibitive law. However, due to its vague wording, the US judicial system did not initially accept drug prohibition. Prosecutors argued that possessing drugs was a tax violation, as no legal licenses to sell drugs were in existence; hence, a person possessing drugs must have purchased them from an unlicensed source. After some time, this was accepted as federal jurisdiction under the interstate commerce clause of the US Constitution. In 1919, the Supreme Court ruled that the Harrison Act was constitutional and physicians could not prescribe narcotics solely for maintenance [17]. In a landmark trial, the court upheld that it was a violation of the Harrison Act even if a physician provided a prescription of a narcotic for the treatment of an addict, and thus they would be subject to criminal prosecution [16, 17]. The original advocates of the Harrison Act did not support the prohibition of the drugs involved and this was also true of the Marijuana Tax Act introduced in 1937 [17]. This latter act allowed the levying of a tax on cannabis trade and also introduced fines, and even jail sentences, for the handlers of hemp and marijuana who violated strict governmental procedures. The passing of the marijuana tax act was successful despite a last-minute opposition from the American Medical Association, which believed that it would prevent a potentially useful medical treatment being provided to the public [17]. Following the end of WWII, the lack of a consistent prohibitory policy resulted in a rise in drug use among young people. The absence of uniform regulation of drug prohibition led to several significant milestones, including the introduction of the single convention on narcotic drugs in 1961 and the passing of the Controlled Substances Act in 1970. In 1972, Nixon launched the so-called war on drugs which was continued by Reagan who created the position of the drug “czar” within the US government. This approach was adopted largely due to the burden of the illegal drug trade in Miami during the 1970s and 1980s [17, 18, 19]. During this period marijuana imports were replaced by cocaine and the vast sums of money being made by the traffickers in Miami began to fuel the economic growth that took place in the city during that period. The money managed by the traffickers began to flow in large quantities into various legitimate businesses including banks, restaurants, and nightclubs. The intense gangland violence associated with the trade and the lawless and corrupt atmosphere in Miami at that time resulted in the gangsters called the “Cocaine Cowboys.” Most of those gangs were associated with the Colombian cartels from Medellin and Cali. During that time, the US government called for increased levels of law enforcement and economic assistance for Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia with the initiation of the US International Counter Narcotics Strategy [16, 17, 18, 19]. It was also announced that US help would be dispatched to Colombia to advise and assist security forces in counter narcotics techniques. One of the key strategies initiated to tackle the problem of drug trafficking was the USD 1.5 billion-financed program known as “Plan Colombia” [20, 21, 22].

Drug-Related Violence and Injuries in the USA

According to the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health [23], 35.3 million Americans aged 12 and older reported having used cocaine, and 8.5 million reported having used crack. An estimated 2.4 million Americans were current users of cocaine and 702,000 were current users of crack. There were an estimated 977,000 new users of cocaine in 2006, most of whom were aged ≥18 years when they first used cocaine. Among young adults aged 18–25 years, the 2006 use rate was 6.9% (no significant difference from 2005) [23]. According to a 2007 survey, cocaine use among students remained at an unacceptably high level, with 3.1% of 8th graders, 5.3% of 10th graders, and 7.8% of 12th graders having tried cocaine. Additionally, the survey revealed that 0.9% of 8th graders, 1.3% of 10th graders, and 2.0% of 12th graders were current cocaine users [12]. In 2008, 2.1% of the US population aged ≥12 years was estimated to have used cocaine in the previous year, and this figure fell from 2.5% in 2006 to 2.3% in 2007 [24].

In the absence of any legal means of settling disputes regarding business transactions, violence remains the predominant method for resolving disagreements within the illicit drug market. Additionally, individuals involved in the dealing of drugs often carry firearms for protection against any rival gangs or individuals, a point emphasized by a study that showed that approximately 80% of 19-year-old cocaine dealers in Pittsburgh carried armed weapons [25].

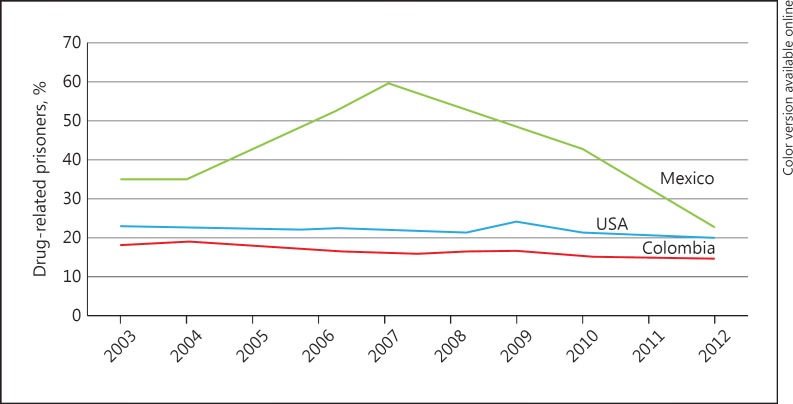

In 2005, approximately one third of all homicides were precipitated by other criminal activities, including drug trading, and in 2009, just in New York State, 54,000 hospital discharges were related to drugs [26]. According to the American Corrections Association, state prisons held 253,300 inmates for drug offenses in 2005, as shown in Figure 1. The average daily cost per state prison inmate per day in the USA is USD 67.55 (KWD 20.46), meaning that the USA spent approximately USD 17,110,415 per day to imprison drug offenders, or USD 6,245,301,475 per year [27, 28, 29].

Fig. 1.

Trend of drug-related crimes committed in the USA, Mexico, and Colombia from 2003 to 2012 [32, 33, 34].

Summary

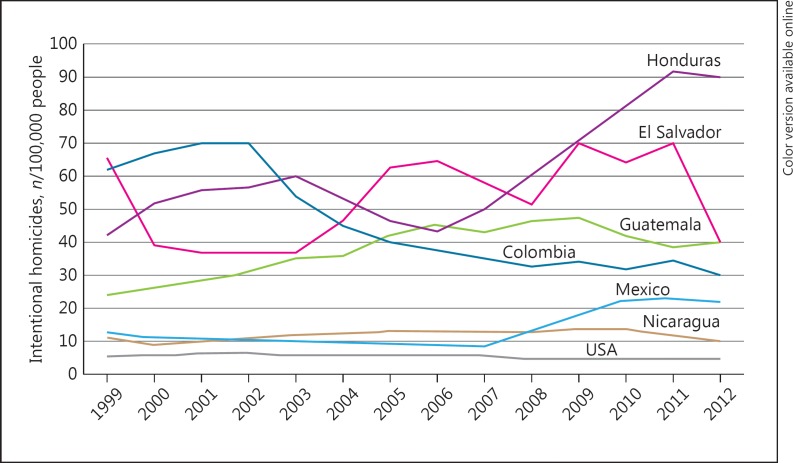

Over the past 40 years, more than USD 2.5 trillion have been spent fighting the illicit drug trade. Despite this, the war on drugs continues to be a human rights challenge, with not only a failed reduction in the introduction of drugs into the USA, but also with increasing levels of drug use and a number of lives lost due to the violence generated by these activities. The impact of this violence and related injuries is far more devastating in poor economies, causing a long-term stigma on these societies that may have spread beyond what could be predicted at any time in history. The current climate of social violence in Central America and the illegal immigration to the USA could be partially related to this phenomenon of drug trafficking, gang violence, and crime. A health care alternative policy shifting the actual criminal justice-based approach could minimize the human rights crisis that is increasing in the border region. Drug-related war areas in countries like Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala have created a humanitarian crisis driving illegal immigrants to the USA-Mexico border. In 2014, more than 57,000 illegal immigrants cross the USA-Mexico border [30]. The history of Central American gang violence dates to the 1980s, when civil wars in El Salvador and Nicaragua sent thousands of people north in search of refuge. Some of the immigrants found their way into gangs in Los Angeles that wound up seeding drug-related violence back home, often after their members were deported from the USA. The explosion of the drug war in Mexico after the Mérida initiative exacerbated the gang-related violence in the other Central American countries. Of 178 suspected drug flights to and from South America in 2007, 132 were coming and going from the Caribbean. By 2011, only about 20 suspected drug flights were using the Caribbean as a waypoint. The rest of the traffic was arriving from or departing to Honduras [30]. The level of poverty and unmet social needs in countries such as Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaragua is correlated with the level of violence and crime (Fig. 2). This correlation is alarming considering certain areas of Honduras are home to some of the highest murder rates per capita in the world. As the war-on-drugs policy continues, the human rights crisis in Central America increases, affecting not only those countries, but also their neighboring countries (Colombia and the USA). Recent reports from the health sector have provided different strategies for antidrug policy development in order to minimize the interaction between drug trafficking, drug consumption, injuries, and human rights violations [31]. The implications of these aspects are really important for clinical, social, and public policies as they are all connected. Drug abuse is a clinical disease motivated in part by social issues including family dysfunction, a lack of educational opportunities, and the absence of economic development policies. Many of these same aspects promote drug trading as an easy way to escape these issues. If public policies are not reinforced in order to tackle these social problems, we will maintain a vicious circle fueling the root of these situations. War-on-drugs policies are an easy way of bring “control” to a situation that needs deeper social changes that are possible only with public policies of education and wellbeing, including economic development and health care policies for drug abuse treated as a medical disease.

Fig. 2.

Trend of intentional homicides in countries strongly involved in drug trafficking in the American region from 1999 to 2012 [35].

The limitations of this review include that it is a narrative report and many other sources of information might not be accessible. The interpretation of the information sources could have been biased by the perception of the authors who are involved in the management of trauma patients in affected countries.

Conclusion

A human rights crisis related to drug trafficking continues to expand across the American continent, directly generating an ever increasing number of injuries and deaths resulting in the exorbitant loss of lives and cost in productivity. The current climate of social violence in Central America and the illegal immigration to USA could be partially related to this phenomenon of drug trafficking, gang violence, and crime. A health care initiative as an alternative to the current war approach may be one of the interventions needed to reduce this crisis.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support of the MEDITECH Foundation research group and the work of the students of the Public Health, Social Development and Human Rights research group of South Colombian University in Neiva (Colombia).

References

- 1.Chepesiuk R. The War on International Drugs: An International Encyclopedia. ed 1. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertram E. Drug War Politics: The Price of Denial. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Astorga L. Drug Trafficking in Mexico: A First General Assessment. Mexico: UNAM; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castro G. Nuestra Guerra Ajena. Bogota: Planeta; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Crisis Group . War and Drugs in Colombia: Latin American Report. Brussels: International Crisis Group; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Drug Intelligence Center . National Drug Threat Assessment 2009. Washington: National Drug Intelligence Center; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherpitel CJ, Borges G. A comparison of substance use and injury among Mexican American emergency room patients in the United States and Mexicans in Mexico. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1174–1180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherpitel CJ, Borges G. Screening for drug use disorders in the emergency department: performance of the rapid drug problems screen (RDPS) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:171–175. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris K. Drug crime and criminalization threaten progress on MDGs. Lancet. 2010;376:1131–1132. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61521-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs . International Narcotics Control Strategy Report. Washington: US Department of State; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lozano R, Río AD, Azalá E, et al. Informe Nacional Sobre Violencia y Salud en México. Mexico City: Secretaría de Salud; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.BBC: Q and A: Mexico's drug-fueled violence [News Report]. 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/7906284.stm (accessed February 24, 2016).

- 13.Procuraduría General de la República . Incidencia delictiva por entidad federativa. Mexico: Procuraduría General de la República; 2014. http://www.pgr.gob.mx/Temas%20Relevantes/estadistica/Incidencia%20Entidad/incidencia%20entidad%200106.asp?numberSection=4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social . Informe de Pobreza en México 2012. Mexico City: Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Molzahn C, Rodríguez O, Shirk D. Drug Violence in Mexico: Data and Analysis through 2012. San Diego: Trans-Border Institute University of San Diego; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen P. Re-Thinking Drug Control Policy: Historical Perspectives and Conceptual Tools. Geneva: UNRISD; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webster P. Learning from history: a review of David Bewley-Taylor's the United States and International Drug Control, 1909–1997. Int J Drug Policy. 2003;14:343–346. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Degrande R. The Cult of Pharmacology: How America Became the World's Most Troubled Drug Culture. Durham: Duke University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levine H. Global drug prohibition: its uses and crises. Int J Drug Policy. 2003;14:145–153. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham B, Scowcroft B, Shifter M. Toward Greater Peace and Security in Colombia: Forging a Constructive US Policy. New York: Council on Foreign Relations, Inter-American Dialogue; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isikoff M. Up to 100 military advisers to be sent to Colombia: DEA agents to resume attacks in Peru. Washington: The Washington Post; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagle L. Plan Colombia: reality of the Colombian crisis and implications for hemispheric security. Carlisle: Army War College-Strategic Studies Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Kammen W, Loeber R. Delinquency, drug use and the onset of adolescent drug dealing. In: Bilchik S, editor. Reducing Youth Gun Violence: An Overview of Programs and Initiatives. Washington: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 26.New York State Department of Health . New York State Drug-Related Discharge Rate per 10,000 Population. New York: New York State Department of Health; 2005. http://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/chac/hospital/drugs65.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sabol W, West H. Prisoners in 2007. Washington: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Correctional Association . 2006 Directory of Adult and Juvenile Correctional Departments, Institutions, Agencies and Probation and Parole Authorities. ed 67. Alexandria: ACA; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanchez Al, Krafty R, Ramirez M, et al. Trends of hospitalizations, deaths, and costs from trauma patients in the United States, 2005–2010. AAST poster competition. 2013. http://www.aast.org/AnnualMeeting/PastAbstracts.aspx

- 30.Johnson S. American-Born Gangs Helping Drive Immigrant Crisis at US Border Central America's Spiraling Violence Has a Los Angeles Connection. Washington: National Geographic; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pugh T, Netherlands J, Finkelstein R. Blueprint for a Public Health and Safety Approach to Drug Policy. New York: The New York Academy of Medicine; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Procuraduría General de la República Temas relevantes. http://www.pgr.gob.mx/Temas%20Relevantes/estadistica/Incidencia%20Entidad/incidencia%20entidad%200106.asp?numberSection=4

- 33.Colombian National Institute of Legal Medicine Forensics. http://www.medicinalegal.gov.co/forensis.

- 34.Bureau of Justice Prisoners series. http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=5109

- 35.The World Bank Intentional homicides (per 100,000 people) http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/VC.IHR.PSRC.P5