Abstract

Introduction

Telepsychiatric modalities are used widely in the treatment of many mental illnesses. It has also been proposed that telepsychiatric modalities could be a way to reduce readmissions. The purpose of the study was to conduct a systematic review of the literature on the effects of telepsychiatric modalities on readmissions in psychiatric settings.

Methods

We conducted a systematic literature search in MEDLINE, CINAHL, Embase, Cochrane, PsycINFO and Joanna Briggs databases in October 2015. Inclusion criteria were (a) patients with a psychiatric diagnosis, (b) telepsychiatric interventions and (c) an outcome related to readmission.

Results

The database search identified 218 potential studies, of which eight were eligible for the review. Studies were of varying quality and there was a tendency towards low-quality studies (five studies) which found positive outcomes regarding readmission, whereas the more methodological sound studies (three studies) found no effect of telepsychiatric modalities on readmission rates.

Discussion

Previous studies have proven the effectiveness of telepsychiatric modalities in the treatment of various mental illnesses. However, in the present systematic review we were unable to find an effect of telepsychiatric modalities on the rate of readmission. Some studies found a reduced rate of readmissions, but the poor methodological quality make the findings questionable. At the present time there is no evidence to support the use of telepsychiatry due to heterogeneous interventions, heterogeneous patient groups and lack of high-quality studies.

Keywords: Telepsychiatry, readmissions, videoconference, telephone calls

Introduction

In countries where distances between health providers are large, telemedicine can be an especially beneficial solution to some of the problems that occur due to the large distances. However, in countries where distances are smaller these tele-interventions may also be relevant in order to increase access to health services for patients with limited physical resources. The effectiveness of telemedicine interventions on somatic conditions have previously been published1–5 and literature reviews are common.6,7

In a psychiatric setting, telepsychiatric modalities can make sense for many reasons. In Denmark, where distances between health providers are small, the argument based on large distances is not valid. However, as in many other countries, recruiting and retaining qualified healthcare professionals is a constant challenge. Therefore, telepsychatric modalities are possibly a means of saving valuable transportation time for health professionals and thereby freeing up resources to treat more patients. A number of types of telepsychiatry modalities are in use: videoconferencing is used for therapy, education, and discharge conferences; telephone calls are used for adherence checks, disease status, visitation services etc.; telepsychiatry is widely used for treatment of various psychiatric illnesses. More specifically, telepsychiatry has proven effective for reduction of disease severity in depression, bi-polar depression, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), schizophrenia and psychosis.8–13 Furthermore, there is a high level of participant satisfaction with the use of telepsychiatric modalities and, in many cases, it even reduces the cost of treatment.14–16 Reduced readmission rates could contribute to the high levels of satisfaction. It is in everybody’s interest to reduce the rate of readmissions. Patients are more comfortable at home, hospitals can allocate the resources to more demanding patients and society reduces the expense of treatment.

However, the effect of telepsychiatry on preventing disease relapse and readmissions is not as thoroughly investigated. Therefore, the aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the effectiveness of telepsychiatric solutions on the reduction of readmissions in psychiatric settings.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature was conducted in October 2015 in order to explore the effectiveness of telepsychiatry for reducing readmissions. Effectiveness relates to the evidence showing statistically significant reduction in readmissions. In the present systematic review, the term ‘telepsychiatry’ is defined as any type of psychiatric treatment modality that is performed in a setting where the treatment provider and receiver are situated in different geographical locations.

Search criteria

The search strategy was designed to access all published materials that combined telepsychiatric modalities with readmissions. An initial search was performed to develop literature and search strategy using the Patient, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome (PICO) research methodology. Based on identified MESH terms, the reviewers made an extensive search in the following databases: PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, Cochrane, PsycINFO and Joanna Briggs.

The search terms used were ‘telemedicine’, ‘telepsychiatry’, ‘psychiatry’, ‘mental disorders’, ‘mental health’, ‘readmissions’ and ‘re-hospitalization’. The search strategy was adopted to fit the particular databases. Based on our initial search, appropriate articles were identified and reviewed.

The types of studies considered for inclusion were those in which: (a) all participants were diagnosed with a psychiatric condition; (b) interventions described were related to telemedicine; and (c) an outcome perspective was included on readmissions or equivalent to this reducing hospitalizations.

Exclusion criteria were: (a) reviews; (b) interventions focusing on children and adolescent psychiatry; and (c) studies with a lack of transparency with regard to endpoints.

Review process and data extraction

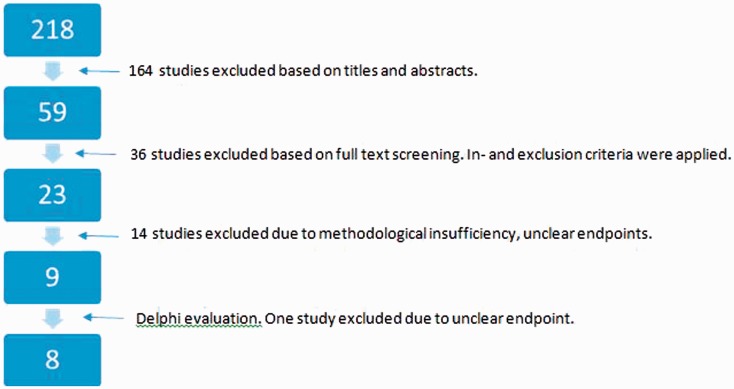

The review process was performed in five stages. By applying the before-mentioned search terms to the above databases, 218 papers were retrieved. The studies where title and abstract did not provide sufficient information were included for further review. This left 59 studies. In the second stage, two reviewers independently reviewed the full-text articles for suitability. Furthermore, articles were screened for references to identify additional studies that were not retrieved from the initial search. This resulted in two additional studies.

For studies where the two reviewers disagreed about suitability and eligibility, a third reviewer participated in the final discussion concerning inclusion or exclusion. If the three reviewers still disagreed, the majority ruled about inclusion or exclusion of the paper. Exclusion at this stage was due to emphasis on other primary diagnoses than psychiatry.

In the third stage, the 23 articles were discussed in depth by three reviewers and exclusion criteria in this stage were related to criteria in stage two, poor method and/or lack of transparency related to endpoints, and this resulted in nine articles. In the fourth stage, three reviewers performed a Delphi evaluation17 on the nine articles resulting in the exclusion of one article due to an unclear endpoint regarding readmission. Finally, at stage five, all eight articles were subjected to the Joanna Briggs data extraction template. The progress of the literature search is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart depicting the process of the literature search.

Results

Studies for review

Very few studies that investigate the effect of telepsychiatric solutions on the prevention of readmissions exist. Only eight studies met the inclusion criteria for this review.16,18–24 An overview is presented in Table 1 along with the level of evidence.

Table 1.

Overview of the included studies.

| Author (year) | Participants | Intervention | n | Study period | Study design | Outcome (re-admissions) | Quality and level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D’Souza (2002) | Inpatients in psychiatric centre | Discharged with videoconference | 78 Intervention: 51, control: 27 | 12 months | CCT | Readmissions Intervention: 1.63 (SD 0.64) Control: 3.48 (SD 0.86) | Delphi: 2/9 Evidence: IIIb |

| Eldon Taylor et al. (2005) | Patients with multiple admissions in the past 12 months | Telephonic care with follow up on non-adherence to outpatient appointments | 60 | 24 months | Quasi-cross-over | Before programme: 2.85 (SD 1.02), after programme: 0.70 (SD 1.14), p < 0.001 | Delphi: 2/9 Evidence: IIIc |

| Godleski et al. (2012) | Veterans with PTSD, schizophrenia or substance use. | Screening of disease severity with an electronic device. | 76 | 24 months | Quasi-cross-over | Decrease of 86% in rehospitalisations (p < 0001). | Delphi: 1/9 Evidence: IIIc |

| Godleski et al. (2012) | Veterans | Videoconferences | 98,609 | 12 months | Quasi-cross-over | Decrease of 24.2% in rehospitalisations | Delphi: 1/9 Evidence: IIIc |

| Rosen et al. (2013) | Veterans with PTSD | Biweekly telephone care in addition to standard care after discharge | 837 Intervention: 425, control: 412 | 12 months | Multisite RCT | No differences between groups. 11% in intervention group, 13% control group were readmitted | Delphi: 5/9 Evidence: II |

| Spaniel et al. (2008) | Outpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | ITAREPS – SMS reminders to complete early warning sign questionnaire | 45 | 34.7 patient/years | Quasi-cross-over | Reduction of 60% in hospitalizations (p < 0.004). High adherence to the programme reduced hospitalisations | Delphi: 2/9Evidence: IIIc |

| Spaniel et al. (2012) | Outpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | ITAREPS | 158 (ITT population: 146) Intervention: 75, control: 71 | 12 months | RCT | No significant differences in ITT analysis. | Delphi: 8/9 Evidence: II |

| Spaniel et al. (2015) | Outpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | ITAREPS | 146 Intervention: 74, control: 72. | 18 months | Double blind, RCT | No significant differences between groups regarding hospitalisations | Delphi: 5/9 Evidence: II |

ITAREPS: Information Technology Aided Relapse Prevention Programme in Schizophrenia; ITT: intention-to-treat; RCT: randomised controlled trial; SD: standard deviation; SMS: short message service.

Design

Of the eight studies included, one study was a Clinical Controlled Trial (CCT),23 four studies were quasi-cross-over designs,16,18,21,22 and three studies were randomised controlled trials (RCTs).19,20,24 The quality of the studies is displayed in Table 1. The studies that used a quasi-cross–over design included a group of patients with previous admissions. After the administration of the intervention the comparison was done between data from before and after the time when the patient was enrolled in the study.

Only one of the RCTs19 used blinding of the caregiver. The rest only blinded the investigator. No blinding allocation was possible in the RCTs, as all participants were aware of the telepsychiatric modality they were enrolled in.

Sample

The variation in sample size between the studies was large. One study included 98,609 veterans22 whereas one RCT21 only included 45 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. The participants had a broad range of psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, major depression, PTSD, bipolar disorder and substance-related disorders. In three studies,16,22,24 war veterans with PTSD were the main focus of investigation.

Interventions

The studies included different forms of telepsychiatric modalities ranging from videoconferences,22,23 telephone monitoring,18 short message service (SMS) questionnnaire19–21 to electronic devices where the patients were to answer some questions daily.16 All but two studies22,23 used the telepsychiatric modality as a form of screening tool, where increase in disease severity was scored, and action was taken if required. The remaining two studies provided psychotherapy via videoconferencing23 or videoconferencing, including supervision of medication intake, urgent care visits, medication management, individual therapy, group therapy and family therapy.22

Outcome

Although the studies reported effects of a variety of interventions and had different study designs, they commonly reported on readmission or rehospitalisation rates. Four studies16,18,22,23 reported a decrease in readmissions following the intervention, while four studies19,20,24 did not show a decrease in readmissions. In most studies relevant statistical methods were applied to investigate significant differences. However, in two studies22,23 no statistical tests were performed, and in one study18 the data analysis was insufficiently described.

Some methodological issues that could potentially affect the outcome of the included studies were lack of control group,23 no randomisation performed,16,18,21,23 vague description of intervention18 and mix of interventions.23

Discussion

We conducted a systematic review of the literature regarding the effects of telepsychiatric modalities in the prevention of readmission. We included eight studies that investigated various modalities including videoconferences, telephone calls and interactive electronic devices to monitor disease severity. The studies used different study designs including RCT and quasi-cross-over designs. Some studies showed up to 86% reduction in readmissions whereas other studies did not find any statistically significant differences.

There was a large variation in the design of included studies. Most studies were of low or moderate quality, which is likely to introduce bias and thereby result in an over- or underestimation of study effects. The included studies that administered a cross-over-like design, are at risk of overestimating the effect of the intervention due to the lack of blinding and an actual control group. Interestingly, it was primarily these studies that managed to show a positive effect of the telepsychiatry modality on readmissions. Godleski et al.16 showed an 86% reduction in readmission in veterans with PTSD using an electronic device to monitor disease severity. The patients were asked to report on their disease severity and general health via the electronic device. This resulted in a large reduction of readmissions. However, the quality of the study was poor and the level of evidence low. In a different study performed on a similar group, Rosen et al.24 were unable to find a significant difference between the groups. The intervention group received a biweekly telephone call in addition to standard care. This study was an RCT including 837 patients. However, the study did not use blinding and thereby increased the risk of bias from patient, caregiver and researcher. In a study with a similar intervention, Eldon Taylor et al.18 reported a reduction in the admission rate from 2.85 to 0.7 admissions over a 12-month period with a quasi-cross-over design. This was performed on a heterogeneous group consisting of 60 patients with multiple previous admissions with psychiatric illnesses. The heterogeneity of the group called for a much larger sample size to even out the variation between patients with different diagnosis.

D’Souza23 used videoconferences upon discharge for inpatients in a psychiatric centre. The finding was a reduction in self-reported readmission rates from 3.48 in the control group to 1.63 in the intervention group. However, no statistical test was performed to investigate the significance of this finding, so it is unknown if the results constitute a statistically significant difference. Furthermore, the study design was CCT but of low quality. There was no blinding and no intention-to-treat analysis included in the study.

In a series of three studies that investigate the same intervention, Information Technology Aided Relapse Prevention Programme in Schizophrenia (ITAREPS) – an SMS-based system to remind patients to complete an early warning questionnaire, Spaniel et al.19–21 have reported conflicting results. In the earliest study, a quasi-cross-over study, they found a 60% statistically significant reduction in readmissions. Furthermore, they found that high adherence to the ITAREPS programme was associated with fewer readmissions. However, the poor study design, small sample size and lack of blinding make these results somewhat unreliable. The latter two studies from the same authors19,20 applied an RCT design and found no significant differences. The authors suggest that a lack of adherence to the study protocol among the treating psychiatrists had a large influence on the non-significant results. The authors are clearly questioning whether the reluctance of the treating psychiatrists is based on a lack of confidence in the technology or a ‘loath to surrender their authority to an impersonal machine-like product’.5

The largest study that we included was published by Godleski et al.22 and included 98,609 veterans who were involved with the US Department of Veteran Affairs. The study investigated a clinic-based videoconference solution and did not include home telepsychiatry encounters. The videoconferences were administered in community-based outpatient clinics. The study found a 24.2% reduction in readmissions, but did not perform statistical analysis on the data. Furthermore, the study design was quasi-cross-over, where the patients’ previous admissions served as the control group. This study had a large sample size, but low quality and evidence level.

The studies included in the present study were characterised by both heterogeneity in patient selection and the investigated treatment, as well as outcome measures. As a consequence of this, direct comparisons between most of the studies are not possible. This also calls for caution with regard to the generalisability of the conclusions. Furthermore, many psychiatric patients have comorbid medical conditions. These conditions may limit their ability to tolerate or cope with different kinds of telepsychiatric modalities, which again would introduce bias to the studies. In the present review, we tried to avoid this by excluding studies that included patients with other primary somatic diseases. However, we cannot know if the patients that were included in the studies had other illnesses. In addition, we did not account for the possibility that the telespychiatric modalities can have differential effects based on the psychiatric diagnosis. In the optimal case, the intervention is planned based on the needs of the patient group. However, in the present review we included some studies where the same intervention was used for a range of psychiatric diagnoses. None of the studies reported the effect of the intervention based on diagnosis, so we cannot know if this had an influence.

The tendency in the present systematic review is our finding that only studies with low quality and evidence level have shown a significant effect of the telepsychiatric modalities. In RCTs of higher methodological quality, the results of the interventions were insignificant. However, only three RCT studies of moderate to good quality was found and the heterogeneity of the interventions makes a direct comparison between them unfeasible.

The fact that none of the high-quality studies found a significant effect of the specific telepsychiatric modality, and that the interventions and study groups in the RCTs were very heterogeneous, stresses that there is a need for high-quality research in this area. It is especially the case that high-quality RCT studies with readmissions as the primary outcome are warranted.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interestwith respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Hwang R, Mandrusiak A, Morris NR, et al. Assessing functional exercise capacity using telehealth: Is it valid and reliable in patients with chronic heart failure? J Telemed Telecare. 2017; 23(2): 225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kato NP, Johansson P, Okada I, et al. Heart failure telemonitoring in Japan and Sweden: A cross-sectional survey. J Med Internet Res 2015; 17: e258–e258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohammadzadeh N, Safdari R. Chronic heart failure follow-up management based on agent technology. Healthc Inform Res 2015; 21: 307–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolltveit B-CH, Gjengedal E, Graue M, et al. Telemedicine in diabetes foot care delivery: Health care professionals’ experience. BMC Health Serv Res 2016; 16: 134–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raymond JK, Berget CL, Driscoll KA, et al. CoYoT1 clinic: Innovative telemedicine care model for young adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2016; 18: 385–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cajita MI, Gleason KT, Han H-R. A systematic review of mhealth-based heart failure interventions. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2016; 31: E10–E22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dagres N, Hindricks G. Pulmonary pressure, telemedicine, and heart failure therapy. Lancet 2016; 387: 408–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rollman BL, Belnap BH, LeMenager MS, et al. Telephone-delivered collaborative care for treating post-CABG depression: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009; 302: 2095–2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim SE, Le Blanc AJ, Michalopoulos C, et al. Does telephone care management help Medicaid beneficiaries with depression? Am J Manag Care 2011; 17: e375–e382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mochari-Greenberger H, Vue L, Luka A, et al. A tele-behavioral health intervention to reduce depression, anxiety, and stress and improve diabetes self-management. Telemed J E Health. 2016; 22(8): 624–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauer MS, Krawczyk L, Miller CJ, et al. Team-based telecare for bipolar disorder. Telemed J E Health. 2016; 22(10): 855–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuen EK, Gros DF, Price M, et al. Randomized controlled trial of home-based telehealth versus in-person prolonged exposure for combat-related PTSD in veterans: Preliminary results. J Clin Psychol 2015; 71: 500–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ben-Zeev D, Brenner CJ, Begale M, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a smartphone intervention for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2014; 40: 1244–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Upatising B, Wood DL, Kremers WK, et al. Cost comparison between home telemonitoring and usual care of older adults: A randomized trial (Tele-ERA). Telemed J E Health 2015; 21: 3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Modai I, Jabarin M, Kurs R, et al. Cost effectiveness, safety, and satisfaction with video telepsychiatry versus face-to-face care in ambulatory settings. Telemed J E Health 2006; 12: 515–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Godleski L, Cervone D, Vogel D, et al. Home telemental health implementation and outcomes using electronic messaging. J Telemed Telecare 2012; 18: 17–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verhagen AP, de Vet HC, de Bie RA, et al. The Delphi list: A criteria list for quality assessment of randomized clinical trials for conducting systematic reviews developed by Delphi consensus. J Clin Epidemiol 1998; 51: 1235–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eldon Taylor C, Lopiccolo CJ, Eisdorfer C, et al. Best practices: Reducing rehospitalization with telephonic targeted care management in a managed health care plan. Psychiatr Serv 2005; 56: 652–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spaniel F, Hrdlicka J, Novak T, et al. Effectiveness of the information technology-aided program of relapse prevention in schizophrenia (ITAREPS): A randomized, controlled, double-blind study. J Psychiatr Pract 2012; 18: 269–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spaniel F, Novak T, Bankovska Motlova L, et al. Psychiatrist’s adherence: A new factor in relapse prevention of schizophrenia. A randomized controlled study on relapse control through telemedicine system. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2015; 22(10): 811–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Španiel F, Vohlídka P, Hrdlička J, et al. ITAREPS: Information technology aided relapse prevention programme in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2008; 98: 312–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Godleski L, Darkins A, Peters J. Outcomes of 98,609 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs patients enrolled in telemental health services, 2006–2010. Psychiatr Serv 2012; 63: 383–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D’Souza R. Improving treatment adherence and longitudinal outcomes in patients with a serious mental illness by using telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare 2002; 8: S113–S115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosen CS, Tiet QQ, Harris AHS, et al. Telephone monitoring and support after discharge from residential PTSD treatment: A randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Serv 2013; 64: 13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]