Key Points

Question

What are the characteristics of patients referred to inpatient palliative care (PC) consultation teams for advance care planning (ACP) or goals of care (GOC) discussions, what ACP/GOC needs are identified, and what are the outcomes?

Findings

In this cohort study of 73 145 patients in inpatient palliative care teams, a need for ACP/GOC was the most common reason for inpatient PC consultation, and ACP/GOC needs were frequently identified even when the consultation request was for other reasons. During PC consultation, surrogates were identified and patients’ preferences regarding life-sustaining treatments were updated; however, only a minority of patients completed legal forms to document their preferences.

Meaning

Inpatient PC consultation meets a common and important need, but there remains opportunity for improvement.

Abstract

Importance

Care planning is a critical function of palliative care teams, but the impact of advance care planning and goals of care discussions by palliative care teams has not been well characterized.

Objective

To describe the population of patients referred to inpatient palliative care consultation teams for care planning, the needs identified by palliative care clinicians, the care planning activities that occur, and the results of these activities.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a prospective cohort study conducted between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2016. Seventy-eight inpatient palliative care teams from diverse US hospitals in the Palliative Care Quality Network, a national quality improvement collaborative. Standardized data were submitted for 73 145 patients.

Exposures

Inpatient palliative care consultation.

Results

Overall, 52 571 of 73 145 patients (71.9%) referred to inpatient palliative care were referred for care planning (range among teams, 27.5%-99.4% of patients). Patients referred for care planning were older (73.3 vs 67.9 years; F statistic, 1546.0; P < .001), less likely to have cancer (30.0% vs 41.1%; P < .001), and slightly more often had a clinical order of full code at the time of referral (54.6% vs 52.1%; P < .001). Palliative care teams identified care planning needs in 52 825 of 73 145 patients (72.2%) overall, including 42 467 of 49 713 patients (85.4%) referred for care planning and in 10 054 of 17 475 patients (57.5%) referred for other reasons. Through care planning conversations, surrogates were identified for 10 571 of 11 149 patients (94.8%) and 9026 patients (37.4%) elected to change their code status. Substantially more patients indicated that a status of do not resuscitate/do not intubate was consistent with their goals (7006 [32.1%] preconsultation to 13 773 [63.1%] postconsultation). However, an advance directive was completed for just 2160 of 67 955 patients (3.2%) and a Physicians Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment form was completed for 8359 of 67 955 patients (12.3%) seen by palliative care teams.

Conclusions and Relevance

Care planning was the most common reason for inpatient palliative care consultation, and care planning needs were often found even when the consultation was for other reasons. Surrogates were consistently identified, and patients’ preferences regarding life-sustaining treatments were frequently updated. However, a minority of patients completed legal forms to document their care preferences, highlighting an area in need of improvement.

This cohort study describes the population of patients referred to inpatient palliative care consultation teams for care planning, the needs identified by palliative care clinicians, and the care planning activities that occur.

Introduction

Advance care planning (ACP) is “a process that supports adults at any age or stage of health in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care. The aim of ACP is to help ensure that people receive medical care that is consistent with their values, goals, and preferences during serious and chronic illness.”1(p826) Goals of care (GOC) discussions have an aim similar to that of ACP and overlap with it, but typically pertain to more proximal decisions.1,2,3 Advance care planning and GOC discussions often occur through a series of conversations over time. Specific wishes, such as preferences for life-sustaining treatments, can be documented in an advance directive (AD) or Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) form to direct future health care. When done effectively, ACP and GOC discussions have been shown to increase the percentage of patients who receive care consistent with their previously expressed wishes, improve patient and family satisfaction, and decrease anxiety and depression in bereaved family members.4,5,6,7,8

Advance care planning and GOC discussions are critical functions of palliative care (PC) teams. The National Consensus Project, which seeks to define and promote high-quality PC, has described care planning as a core competency for PC teams.9 National training programs focus on care planning as an essential skill for PC physicians.10 Furthermore, the Joint Commission’s Advanced Certification Program for PC requires that PC clinicians document care plans for all patients they see.11 Despite these guidelines, to our knowledge the nature of the ACP and GOC discussions requested of and performed by inpatient PC teams has not yet been described in a diverse sample of PC teams in the United States. Using the Palliative Care Quality Network (PCQN) database, a registry of patient-level, standardized data collected by PC clinicians about inpatients referred for consultation, we sought to characterize the care planning performed by PC teams. Specifically, we examined which patient characteristics are associated with referral to PC for ACP or GOC discussions, ACP or GOC needs identified by PC clinicians, and the results of ACP or GOC conversations.

Methods

The PCQN

The PCQN is a large, multisite collaborative of interdisciplinary PC teams that collect standardized data about their patients and practice to benchmark processes of care and outcomes, identify best practices, and drive quality improvement.12 As of December 31, 2016, there were 78 PC teams entering patient-level data into the PCQN database from a diverse group of academic and community hospitals in 11 states in the United States.

Data Set

The 23-item PCQN core data set includes patient demographics, actions taken by PC teams, and clinical outcomes. Demographic information includes patient age, sex, primary diagnosis, and Palliative Performance Scale score.13 Process measures include date of the PC referral, reason(s) for the PC consultation (eg, ACP and/or GOC, pain management, comfort care), PC disciplines involved in the consultation (eg, physician, social worker, nurse, chaplain), PC needs screened for (eg, ACP and/or GOC, pain, other symptoms, psychosocial and spiritual needs) and results of the screen, PC needs intervened on by the PC team (the PCQN defines a PC intervention as a concerted effort to address a particular need, which does not necessarily lead to resolution of the need), number of family meetings conducted, whether code status was clarified (meaning that it was specifically discussed with the patient or surrogate and either confirmed or changed), completion of ACP forms, such as an AD or POLST form, and services arranged on hospital discharge (eg, hospice, home-based PC). Patient-level outcomes are also documented, including daily symptom scores for pain, dyspnea, nausea, and anxiety; code status; and survival to hospital discharge. There are additional optional data elements that teams can choose to collect, including whether a surrogate decision maker was documented and code status at discharge. Most optional data elements have been added since the introduction of the core data set in response to needs identified by teams in the PCQN; they are not collected by all teams. A full list of the PCQN data elements is available at www.pcqn.org.

Of note, ACP and GOC were combined into “ACP/GOC” in PCQN data elements in recognition that these 2 processes are often performed concurrently for seriously ill inpatients and are difficult for clinicians to consistently distinguish.1,2,3 For readability we have used the terms ACP or care planning rather than ACP/GOC through most of this article, but we recognize that some of these conversations would be more accurately and specifically described as GOC conversations, particularly when they address very proximal decisions.

For the purposes of the PCQN, a PC consultation is defined as the series of PC visits that occur for a single patient during a single hospitalization. Clinicians are encouraged to enter data for all 23 of the core data elements for every patient they see during the consultation. However, because the PCQN database is used primarily for quality improvement and data are collected by clinicians in the course of usual patient care, not all data elements are completed for every patient. There is no effort to obtain missing data.

The data for this study were extracted on February 2, 2017, and include the PC consultation records of patients who received consultation requests between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2016. This study was reviewed and approved by the UCSF institutional review board.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (frequencies, means [SDs], and ranges) were used to examine the distribution of measures, as appropriate. We used χ2 analysis to test for bivariate associations among categorical variables and analysis of variance to examine the association among patient characteristics, PC team activities, and outcomes of care as well as whether a patient was referred to PC for ACP. From these analyses, independent variables that were significant at P ≤ .10 were included in a multivariate logistic regression model to identify predictors associated with patients being referred to PC for ACP. The categorical variable of “PC teams” was included as a fixed effect to adjust for any potential variation among the teams. To analyze change in code status during PC consultation, a McNemar-Bowker test was performed. An α ≤ .05 was used to determine statistical significance. There was no adjustment or imputation for missing data; we performed analyses only for patients for whom data were available for each specific data element, resulting in variations in n values for each analysis. SPSS statistical software (for Mac; version 23; SPSS Inc) was used to conduct all analyses.

Results

Referrals for ACP

There were 73 145 PC consultations by 78 PC teams during our study period. Advance care planning was the most common reason for PC consultation (52 571 of 73 145 consultations [71.9%]). However, the percentage of referrals for ACP varied among teams (range, 27.5%-99.4%). Of patients referred for ACP, 28 414 of 52 571 (54.0%) were referred only for that reason. The other 24 157 patients (46.0%) who were referred to PC for ACP were also referred for additional reasons, such as referral to hospice (9026 [37.4%]), pain management (7296 [30.2%]), other symptom management (6950 [28.8%]), transition to comfort care (3017 [12.5%]), and withdrawal of interventions (1923 [8.0%]). Palliative care consultation requests occurred on average 4.7 days (95% CI, 4.3-5.1 days) after hospital admission.

Univariate analyses revealed that patients referred to PC for ACP were older than those referred for other reasons (73.3 years vs 67.9 years; P < .001), had lower Palliative Performance Scale scores (34.2 vs 37.2; P < .001), were less likely to have cancer (30.0% vs 41.1%; P < .001), and were slightly more likely to have a clinical order of full code at the time of PC consultation request (54.6% vs 52.1%; P < .001) (Table 1). Patients referred for ACP were also more likely to have a POLST form in the medical record at the time of referral to PC (12.4% vs 9.7%; P < .001), but no more likely to have an AD at the time of referral (22.7% vs 21.2%; P = .06).

Table 1. Patient Characteristics Associated With Referral to PC for ACPa.

| Characteristic | Referral for ACP/GOCb | Referral for Other Reason(s) | Statistic Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | (n = 52 524) | (n = 19 426) | |

| Age, mean (95% CI), y | 73.3 (73.2-73.4) | 67.9 (67.9-68.2) | F = 1546.0 |

| Sex, No. (%) | (n = 52 543) | (n = 19 449) | |

| Female | 26 576 (50.6) | 10 440 (53.7) | χ2 = 54.6 |

| Male | 25 967 (49.4) | 9009 (46.3) | |

| Patients with Palliative Performance Scale score | (n = 46 658) | (n = 15 922) | |

| Score, mean (95% CI) | 34.2 (34.1-34.4) | 37.2 (36.9-37.6) | F = 293.1 |

| Patients with primary diagnosis, No. (%) | (n = 51 499) | (n = 8 593) | |

| Cancer | 15 472 (30.0) | 7645 (41.1) | χ2 = 878.0 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 7333 (14.2) | 1743 (9.4) | |

| Pulmonary disease | 6115 (11.9) | 1748 (9.4) | |

| Neurologic disease | 5313 (10.2) | 1730 (9.3) | |

| Other | 17 266 (33.5) | 5727 (30.8) | |

| Level of care at time of PC referral, No. (%) | (n = 52 330) | (n = 19 272) | χ2 = 1207.0 |

| Medical/surgical unit | 20 140 (38.5) | 8566 (44.4) | |

| Critical care unit | 13 266 (25.4) | 3778 (19.6) | |

| Telemetry/step-down unit | 14 311 (27.3) | 3916 (20.3) | |

| Other | 4613 (8.8) | 3012 (15.6) | |

| Patients with code status at time of PC referral, No. (%) | (n = 51 263) | (n = 18 095) | χ2 = 85.2 |

| Full code | 28 001 (54.6) | 9429 (52.1) | |

| Partial code | 3338 (6.5) | 980 (5.4) | |

| DNR/DNI | 19 924 (38.9) | 7686 (42.5) | |

| Patients with AD at time of PC referral | (n = 50 962) | (n = 18 460) | |

| No. (%) | 11 574 (22.7) | 3921 (21.2) | χ2 = 16.9 |

| Patients with POLST at the time of PC referral | (n = 49 692) | (n = 18 093) | |

| No. (%) | 6137 (12.4) | 1747 (9.7) | χ2 = 93.7 |

| Patients hospital LOS prior to consultation request | (n = 52 185) | (n = 19 104) | |

| Mean (95% CI), d | 4.5 (4.3-4.6) | 4.7 (4.3-5.1) | F = 2.1 |

Abbreviations: ACP, advance care planning; AD, advance directive; DNI, do not intubate; DNR, do not resuscitate; GOC, goals of care; LOS, length of stay; PC, palliative care; POLST, physician orders for life-sustaining treatment.

P < .001 for all comparisons.

Patients in ACP/GOC group may have additional reasons for PC consultation identified by the referring team.

After adjusting for all characteristics that were significantly associated with referral for ACP in the univariate analyses, and accounting for differences among PC teams, multivariate logistic regression showed that men were more likely to be referred for ACP (odds ratio [OR], 1.12; 95% CI, 1.07-1.16) (Table 2), as were patients with cardiovascular (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.23-1.43) or pulmonary disease (OR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.13-1.31), and those in telemetry/step down (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.55-1.73) or intensive care units (OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.45-1.63). Patient with a code status of do not resusciate/do not intubate (DNR/DNI) were less likely to be referred to PC for ACP (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.57-0.63).

Table 2. Logistic Regression Identifying Characteristics Associated With Referral to PC for ACP/GOC.

| Characteristic | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.02 (1.01-1.02) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1.12 (1.07-1.16) | <.001 |

| Female | 1 [Reference] | |

| Palliative Performance Scale score | 0.99 (0.99-0.99) | <.001 |

| Primary diagnosis | ||

| Cancer | 1 [Reference] | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1.33 (1.23-1.43) | <.001 |

| Pulmonary disease | 1.22 (1.13-1.31) | <.001 |

| Neurologic disease | 1.00 (0.93-1.08) | .98 |

| Other | 1.15 (1.09-1.21) | <.001 |

| Level of care at time of referral | ||

| Medical/surgical unit | 1 [Reference] | |

| Critical care unit | 1.54 (1.45-1.63) | <.001 |

| Telemetry/step-down unit | 1.63 (1.55-1.73) | <.001 |

| Other | 0.78 (0.73-0.84) | <.001 |

| Code status | ||

| Full code | 1 [Reference] | |

| Partial code | 0.95 (0.87-1.04) | .30 |

| DNR/DNI | 0.60 (0.57-0.63) | <.001 |

| PC team | Data not included | <.001 |

Abbreviations: ACP/GOC, advance care planning and goals of care; DNI, do not intubate; DNR, do not resuscitate; OR, odds ratio; PC, palliative care.

Needs Identified by PC Teams

During the consultation, PC teams identified ACP needs in 52 825 of 73 145 patients (72.2%) overall, which included 42 467 of 49 713 patients who were referred for ACP (85.4%) and 10 054 of 17 475 patients who were not referred for ACP (57.5%). Palliative care teams addressed ACP needs in 39 981 of 42 458 patients who were referred for ACP (94.2%). Even among patients referred to PC for reasons other than ACP, most had their ACP needs addressed by the PC team when they were found (9220 of 10 053 [91.7%]).

Forty percent of the patients referred for ACP (with or without additional reasons) reported having pain (20 131 of 50 062 [40.2%]) and other symptoms (23 134 of 50 062 [46.2%]) when assessed by the PC team. Psychosocial and spiritual needs were also common regardless of the reason for PC referral (24 046 of 49 524 [50.6%] and 13 238 of 49 055 [27.0%], respectively). In most cases in which additional needs were identified, PC clinicians addressed these needs even though the consultation was requested for ACP (pain was addressed in 17 796 of 20 126 of the cases in which it was identified [88.4%]; other symptoms, 20 703 of 23 131 [89.5%]; psychosocial needs, 23 181 of 25 047 [92.6%]; and spiritual needs, 14 926 of 16 539 [90.2%]).

ACP Activities and Results

Palliative care consultations for ACP involved physicians (25 802 of 49 408 [52.2%]), social workers (19 672 of 49 408 [39.8%]), chaplains (16 210 of 49 408 [32.8%]), and registered nurses (18 305 of 49 408 [37.0%]). Patients were followed by the PC team for an average of 5.5 days (median, 3.0 days; range, 3.3-9.8 days), and PC teams had an average of 1.4 family meetings (median, 1.0 meetings; range, 0.3-4.1 meetings) throughout the course of the consultation. Based on data from the subset of 57 teams that collected data for the optional data element of surrogate decision maker documented, surrogates were identified for 10 571 of 11 149 patients (94.8%; range, 71.1%-100%).

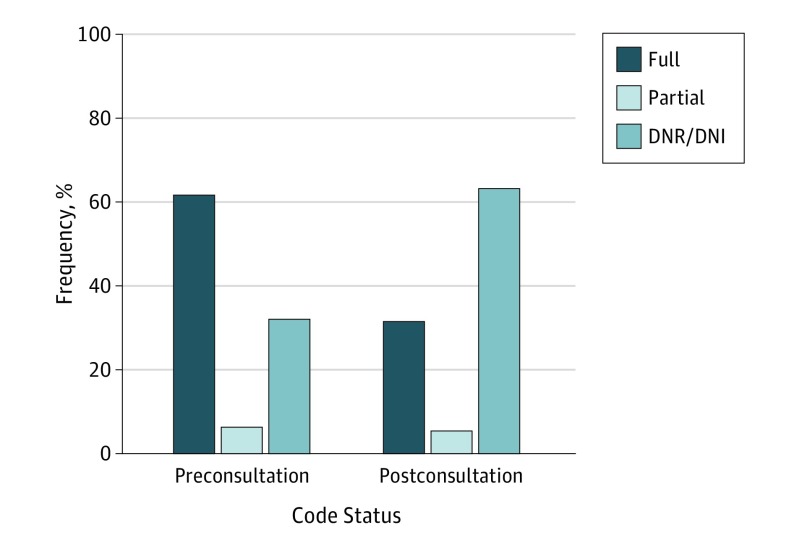

We found a significant change in the distribution of patients’ code status orders from the time of referral to PC to the conclusion of the PC consultations (Figure). Of patients for whom the optional data element of code status at the conclusion of the PC consultation was documented, we found that 8163 patients (37.4%) changed their code status in the course of the PC consultation. It was more common for patients who initially had a clinical order of Full Code to change their code status to express a preference for less aggressive treatment (6933 [51.5%]), but 292 patients (4.2%) who initially had status of DNR/DNI changed their code status to express a preference for more aggressive treatment. Even among patients who had completed an AD or POLST form prior to the PC referral, indicating that they had previously engaged in ACP, many patients changed their code status during the course of the PC consultation (34.9% of patients who had previously completed an AD and 27.1% of patients who had previously completed a POLST form changed their code status).

Figure. Change in Code Status During Palliative Care Consultation.

McNemar-Bowker test: P < .001; a total of 21 827 patients had code status preconsultation and code status postconsultation documented in the PCQN database and therefore the number of patients who were included in the analysis of how code status changed from preconsultation to postconsultation.

Despite the fact that patients’ surrogate decision maker and code status were frequently clarified, an AD was completed for just 2160 of 67 955 patients (3.2%; range, 0%-27.3%) and a POLST form was completed for 8359 of 67 955 (12.3%; range, 0%-50.7%). Even among patients who expressed a preference to limit life-sustaining treatments (eg, DNR/DNI or Partial Code status), survived until hospital discharge, and were followed by the PC team until the end of the hospitalization, AD and POLST forms were infrequently completed (for 467 of 10 987 patients [4.3%] and 3184 of 10 987 patients [29.0%], respectively). Among patients discharged to an extended care facility, where POLST forms are required in many states, a POLST was completed for 2103 of 11 405 patients (18.4%) overall and for 852 of 2749 patients (31.0%) who had a preference to limit life-sustaining treatments at the time of hospital discharge.

All aspects of ACP were more common among patients referred to PC for ACP, but PC teams also commonly engaged in ACP with patients who were referred for other reasons (Table 3). There was no significant difference in the hospital length of stay among patients who had ACP addressed by the PC team (10.0 days; 95% CI, 9.8-10.2 days) and those who did not (9.7 days; 95% CI, 9.4-10.2 days; P = .13).

Table 3. ACP/GOC Activities and Outcomes of PC Consultationsa.

| Activities and Outcomes | Referral for ACP/GOCb | Referral for Other Reason(s) | Statistic Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surrogate decision maker, No. (%) | (n = 11 149) | (n = 3264) | |

| Addressed, identified | 10 571 (94.8) | 3038 (93.1) | χ2 = 40.7 |

| Addressed, none identified | 348 (3.1) | 94 (2.9) | |

| Not addressed | 230 (2.1) | 132 (4.0) | |

| Family meetings | (n = 47 824) | (n = 15 705) | |

| Mean (95% CI) | 1.4 (1.38-1.41) | 1.19 (1.2-1.2) | F = 242.8 |

| Code status clarified | (n = 49 067) | (n = 16 994) | |

| No. (%) | 26 707 (54.4) | 6106 (35.9) | χ2 = 1728.0 |

| AD completed during PC consultation | (n = 49 711) | (n = 17 268) | |

| No. (%) | 1777 (3.6) | 376 (2.2) | χ2 = 80.4 |

| POLST completed during PC consultation | (n = 49 711) | (n = 17 268) | |

| No. (%) | 7212 (14.5) | 1092 (6.3) | χ2 = 790.4 |

| In-hospital death | (n = 51 208) | (n = 18 374) | |

| No. (%) | 11 074 (21.6) | 4569 (24.9) | χ2 = 81.5 |

| Discharge location, No. (%)c | (n = 73 061) | (n = 27 233) | |

| Home | 39 520 (54.1) | 13 505 (49.6) | |

| Long-term acute care hospital | 17 549 (24.0) | 7491 (27.5) | χ2 = 645.9 |

| Extended care facility | 1248 (1.7) | 2167 (8.0) | |

| Hospital inpatient (PC team signed-off prior to hospital discharge) | 9684 (13.3) | 2167 (8.0) | |

| Other | 5460 (7.5) | 1903 (7.0) | |

| Services arranged at dischargec | |||

| Hospice | (n = 35 127) | (n = 11 786) | χ2 = 33.1 |

| No. (%) | 13 262 (37.8) | 4101 (34.8) | |

| Clinic-based PC | (n = 35 089) | (n = 11 764) | χ2 = 674.3 |

| No. (%) | 1087 (3.1) | 1048 (8.9) | |

| Home-based PC | (n = 35 084) | (n = 11 762) | χ2 = 13.7 |

| No. (%) | 1608 (4.6) | 444 (3.8) | |

| Home health care | (n = 35 099) | (n = 11 775) | χ2 = 31.7 |

| No. (%) | 5389 (15.4) | 2066 (17.5) | |

| Other | (n = 35 089) | (n = 11 774) | χ2 = 21.2 |

| No. (%) | 2505 (7.1) | 695 (5.9) | |

| No services | (n = 35 137) | (n = 11 789) | χ2 = 27.7 |

| No. (%) | 12 224 (34.8) | 3788 (32.1) |

Abbreviations: ACP, advance care planning; DNI, do not intubate; DNR, do not resuscitate; GOC, goals of care; LOS, length of stay; PC, palliative care; POLST, physician orders for life-sustaining treatment.

P < .001 for all comparisons.

Patients in ACP/GOC group may have additional reasons for PC consultation identified by the referring team.

Among patients discharged from the hospital alive.

Discussion

Palliative care teams at 78 diverse US hospitals prospectively collected data that describe the ACP and GOC discussions that occur during inpatient PC consultations. These findings highlight strengths and gaps in care that can be used by PC clinicians for benchmarking and quality improvement. They also enable non-PC clinicians and health care administrators to understand the value of PC and identify issues amenable to system-level solutions.

Assistance with ACP and GOC discussions was requested in nearly three-quarters of PC consultations overall and was the most common reason for PC consultation. Older and sicker patients were more likely to be referred for ACP or GOC. Palliative care teams engaged in care planning with most of the patients they saw, frequently clarifying both surrogate decision maker and code status. In nearly one-third of patients, PC teams identified a preference to limit life-sustaining interventions (eg, code status of DNR/DNI) that had not been previously documented. A change in code status was common even among patients who had previously completed an AD or POLST form, illustrating the importance of continuing care planning conversations over time as clinical context and patients’ priorities change. These conversations are critical work that can promote care that is consistent with patients’ values while improving resource utilization by helping patients avoid unwanted interventions at the end of life.

More than half of the patients who were referred to PC for reasons other than ACP or GOC were also found to have a need for care planning when seen by the PC team. This finding highlights the dynamic nature of patients’ needs and the different information yielded by PC assessments compared with those of primary teams. Furthermore, even patients who had engaged in prior ACP, as evidenced by an AD or POLST on the medical record at the time of referral to PC, frequently had a need for further care planning when evaluated by the PC team, demonstrating the need for planning to occur in a longitudinal and iterative fashion with reconsideration when clinical status changes. Care planning is not complete simply because a form has been signed.

The large number of additional issues—including pain and other symptoms as well as psychosocial and spiritual needs—that were identified in patients referred for ACP or GOC shows the complexity of seriously ill patients. Palliative care teams intervened in most of these issues, regardless of the reason for PC referral, which highlights the importance of the interdisciplinary composition of PC teams and comprehensive screening for PC needs during each consultation. The reason for referral to PC physicians is not sufficient information to limit the scope of a consultation.

There remains substantial room for improvement, however. Despite the fact that PC teams commonly clarified preferences for surrogate decision maker and code status, few patients left the hospital with a completed AD or POLST form. It may not be reasonable to expect inpatient PC teams to complete ADs routinely given that the legal requirements of ADs in many states make them difficult to complete during short hospitalizations, ADs are within the purview of many other professionals, and ADs may not be effective for all seriously ill inpatients.14 However, completion of POLST forms (and analogous documents depending on the state) for patients who wish to limit life-sustaining treatments is a reasonable expectation of PC teams and can have important clinical impact.15 We found a substantial variation in the rate of POLST completion across teams in the PCQN (0%-50.7%), suggesting that better performance is achievable. In recognition of this quality gap, we are currently undertaking a multisite quality improvement project within the PCQN to increase POLST completion. Through direct observation and deeper qualitative analyses to understand the processes of care of high-performing teams, we are seeking identify strategies that can be adopted widely to improve care. We are tracking and reporting comparative data for all teams in the network to motivate change.

Limitations

We would like to highlight several limitations of our study. It is important to note that all PCQN data are collected by PC clinicians in the course of usual patient care. This approach has the advantage that data are prospectively collected and directly reflect the work done by clinicians rather than their documentation practices. However, because data are collected by busy clinicians, the PCQN data set was kept concise for it to be feasible. We therefore do not have detailed information, for instance about patients’ comorbidities, clinical circumstances, and the specific ACP or GOC needs identified, which limits the granularity of our findings. We were also unable to fully characterize the care planning that occurred, including what percentage were ACP vs GOC conversations. The PCQN strove to include data elements that are unambiguous whenever possible (eg, code status, whether a POLST form was completed) and developed a data dictionary to define and standardize each data element (eg, an ACP/GOC “intervention” is defined as a concerted effort to address an ACP/GOC need, which does not necessarily lead to resolution of the need), but still it is difficult to ensure that the data elements were interpreted identically by all clinicians who collected data. The PCQN data set does not include any information about patients’ or families’ opinions of their needs or the care they received, although these data are important and will be a focus of future work for the PCQN. An important goal of care planning is for patients to receive care consistent with their values and preferences, but this concordance is challenging to measure, and we are not currently able to report this outcome. We also did not collect information about the needs or clinical outcomes of patients who were not seen by PC consultation teams. Finally, given the large sample size, we are aware that statistically significant results are not necessarily clinically meaningful; we tried to be careful to highlight only clinically meaningful findings.

Conclusions

Our data show that ACP and GOC needs are prevalent in patients referred to PC teams and assistance with care planning is the most common reason for inpatient PC consultation. Palliative care clinicians frequently address care planning with patients and families, identify surrogate decision makers, and clarify care preferences to promote patient autonomy and reduce unwanted care. Care planning, though time consuming, does not result in longer hospital length of stay. However, the fact that few patients have their care preferences legally documented by the time of hospital discharge highlights a significant opportunity to improve care. Further direct observation and study of better performing teams is planned to identify best practices in care planning that can be disseminated across the PCQN and the field.

References

- 1.Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(5):821-832.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sinuff T, Dodek P, You JJ, et al. Improving end-of-life communication and decision making: the development of a conceptual framework and quality indicators. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(6):1070-1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):256-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernacki RE, Block SD; American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force . Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1994-2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leung JM, Udris EM, Uman J, Au DH. The effect of end-of-life discussions on perceived quality of care and health status among patients with COPD. Chest. 2012;142(1):128-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davison SN, Simpson C. Hope and advance care planning in patients with end stage renal disease: qualitative interview study. BMJ. 2006;333(7574):886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Houben CHM, Spruit MA, Groenen MTJ, Wouters EFM, Janssen DJA. Efficacy of advance care planning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(7):477-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bischoff KE, Sudore R, Miao Y, Boscardin WJ, Smith AK. Advance care planning and the quality of end-of-life care in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):209-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 3rd ed Pittsburg, PA: National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myers J, Krueger P, Webster F, et al. Development and validation of a set of palliative medicine entrustable professional activities: findings from a mixed methods study. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(8):682-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Joint Commission Palliative Care Certification Manual 2014. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission Resources; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pantilat SZ, Marks AK, Bischoff KE, Bragg AR, O’Riordan DL. The Palliative Care Quality Network: improving the quality of caring. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(8):862-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson F, Downing GM, Hill J, Casorso L, Lerch N. Palliative performance scale (PPS): a new tool. J Palliat Care. 1996;12(1):5-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fagerlin A, Schneider CE. Enough: the failure of the living will. Hastings Cent Rep. 2004;34(2):30-42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hickman SE, Keevern E, Hammes BJ. Use of the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment program in the clinical setting: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(2):341-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]