Abstract

Background

Young men living in Dar es Salaam’s informal settlements face environmental stressors that may expose them to multiple determinants of HIV risk including poor mental health and risky sexual behavior norms. We aimed to understand how these co-occurring risk factors not only independently affect men’s condom use and sexual partner concurrency, but also how they interact to shape these risk behaviors.

Methods

Participants in the study were male members of 59 social groups known as “camps” in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. We assessed moderation by changes in peer norms of the association between changes in symptoms of anxiety and depression and sexual risk behaviors (condom use and sexual partner concurrency) among 1113 sexually active men. Participants nominated their three closest friends in their camp and reported their perceptions of these friends’ behaviors, attitudes, and encouragement of condom use and concurrency. Anxiety and depression were measured using the HSCL-25 and condom use and sexual partner concurrency were assessed through self-report.

Results

Perceptions of decreasing condom use among friends (descriptive norms) and decreasing encouragement of condom use were associated with lower levels of condom use. Perceptions of increasing partner concurrency and acceptability of partner concurrency (injunctive norms) among friends were associated with higher odds of concurrency. Changes in perceived condom use norms (descriptive norms and encouragement) interacted with changes in anxiety symptoms in association with condom use such that the negative relationship was amplified by norms less favorable for condom use, and attenuated by more favorable norms for condom use.

Conclusions

These results provide novel evidence of the interacting effects of poor mental health and risky sexual behavior norms among a hard to reach population of marginalized young men in Dar es Salaam. Our findings provide important information for future norms-based and mental health promotion interventions targeting HIV prevention in this key population.

Keywords: Tanzania, men, mental health, condom use, concurrency, social norms, HIV

INTRODUCTION

There are 4 million young people ages 15–24 living with HIV (UNAIDS, 2014), 85% of whom live in sub-Saharan Africa (Idele et al., 2014). AIDS-related deaths among youth rose by 50% between 2005 and 2012 and adolescents and young adults account for a growing proportion of African populations (Idele et al., 2014), making the need to target and engage youth in HIV prevention increasingly important. In Tanzania specifically, 40 percent of new infections occur among 16–24 year olds (ICF International, 2013). Young men are important targets in HIV prevention in this context as gender norms position them to control the terms and conditions of sexual relationships (Barker & Ricardo, 2005), and encourage them to engage in high risk sexual behaviors including inconsistent condom use and sexual partner concurrency (Dunkle et al., 2006; Noar & Morokoff, 2002; Raj et al., 2006). Half of sexually active Tanzanian youth ages 15–24 did not use a condom at last intercourse in 2010, and nearly one-third reported concurrent partners (ICF Macro, 2011).

HIV risk in eastern and southern Africa has been observed to cluster in informal urban settlements (Greif et al., 2010; Magadi, 2013). The majority of urban residents in southern and eastern Africa live in these settlements, informally known as slums (United Nations, 2014). The populations of these settlements are growing due to rapid urbanization. In Dar es Salaam, the city’s growing population has led to a high demand for improved infrastructure, which the government has been largely unable to meet, and as a result an estimated 70% of the city’s population lives in informal settlements (United Nations, 2014). People living in these settlements lack access to sufficient housing and basic services such as water and sanitation (United Nations Human Settlements Programme, 2009). The prevalence of these living conditions is also explained by the high levels of poverty (Dar es Salaam City Council, 2004) and unemployment (21.5%) in the city (National Bureau of Statistics, 2014). Residence in contexts like these settlements is linked to HIV risk through a number of mechanisms. Both the state of poverty itself and the context of disadvantage in impoverished neighborhoods promote sexual risk behaviors (Akers et al., 2011; Bauermeister et al., 2011; Bowleg et al., 2014). As there are often poor education and employment options in these settings (MacLeod, 2010; South et al., 2003), youth often lack hope and positive orientation to the future (Smith & Elander, 2006), which is in turn linked to risk behavior (Prince et al., 2016; Robbins & Bryan, 2004). Neighborhood physical disorder also contributes to psychological distress (Curry et al., 2008) by providing a constant reminder of one’s status in poverty (Wilson, 2012). The living environment can shape mental health through other stressors, such as violence, poor housing, noise, and crowding (Morello-Frosch et al., 2011; Wallis et al., 2010); poor mental health in turn can shape sexual risk (Bowleg et al., 2014).

An impoverished living context has also been associated with riskier norms related to sexual behavior. The social isolation of impoverished neighborhoods can create a context in which distinct norms emerge and sustain themselves (Baumer & South, 2001; Wilson, 2012). Neighborhood disorder is also associated with the perceived prevalence of sexual risk behaviors (Davey-Rothwell et al., 2015). The potential clustering of risky social norms is of concern for HIV prevention as norms shape individuals’ perceptions of acceptable behavior, particularly for youth who are more strongly influenced by the attitudes and behaviors of their peers that older adults (Giordano, 2003). Normative influence may take the form of active peer pressure (Bernburg & Thorlindsson, 2005), leading to perceptions of what behaviors are considered acceptable to peers, known as injunctive norms (Cialdini et al., 1990). Influence can also occur through less direct social learning processes (Browning et al., 2004; Harding, 2009) whereby peers both transmit and reinforce norms (Oostveen et al., 1996) shaping individual perceptions of what peers are actually doing, known as descriptive norms (Cialdini et al., 1990).

In disadvantaged contexts, youth are exposed to multiple susceptibilities including normative risk behaviors and poor mental health. It is important to understand if these coexisting susceptibilities simply add to one another or compound in shaping young men’s predisposition to sexual risk behaviors. Knowledge of such a compounding (or interaction) effect would indicate the need to address these susceptibilities in tandem and not in separate, targeted programs. Because of previous preliminary quantitative evidence from the study population (Hill et al., 2016; Mulawa, Yamanis, Hill et al., 2016), we have chosen to focus on mental health and social norms to assess the extent to which these susceptibilities act together to shape sexual risk. Qualitative evidence from the study population also suggests the importance of sexual behavior norms in this context, indicating that men pressure and encourage each other to engage in sexual risk behaviors (Yamanis et al., 2010).

Behavioral norms and mental health have been shown to interact to shape drinking behaviors among youth in the US (Pedersen et al., 2013), but there are no studies to our knowledge assessing a similar relationship for sexual behaviors. To address this gap, we aim to understand if social norms moderate the relationship between mental health and sexual risk. The experience of anxiety and depression may create an inclination toward sexual risk behaviors through maladaptive coping to deal with stress (Bachanas et al., 2002) and impaired decision making (Bennett & Bauman, 2000). As peers serve as a reference groups which individuals look to in behavioral decision-making (Kemper, 1968), riskier norms among peers may increase the likelihood that an inclination toward risk behavior resulting from poor mental health manifests in actual risk behaviors. We therefore hypothesize that higher levels of risk behaviors among peers and perceptions of riskier norms among peers will serve to magnify the risk relationship between mental health and sexual risk behaviors. Further, we aim to gain specific understanding of the role of different types of social norms in shaping men’s sexual behaviors, and do so by additionally assessing the direct effect of observed peer behaviors and perceived behavioral norms on men’s sexual behaviors. The results of this study offer implications for future interventions aiming to reduce HIV risk among young men living in urban informal settlements in East Africa.

METHOD

Study context

This study was conducted in the context of an HIV prevention trial, a cluster randomized trial of a microfinance and health leadership intervention to prevent sexually transmitted infections and intimate partner violence (Kajula et al., 2016). Participants in this trial were members of venues known as “camps” in Dar es Salaam where young men 1) socialize and engage in small-scale enterprise; 2) who typically belong to only one camp; 3) pay membership fees to belong to that camp; 4) frequent the venue for its supportive social environment; and 5) most camp members are not formally employed and spend several hours each day at their camp (Yamanis et al., 2010).

Sampling and data collection

We identified camps for inclusion in the trial in four wards (equivalent to U.S. census tracts) of Dar es Salaam (Manzese, Tandale, Mwananyamala, and Mabibo) using an adaptation of PLACE (Priorities for Local AIDS Control Efforts) methodology (Weir et al., 2003). To be eligible for inclusion in the trial, camps had to have between 20 and 80 members, have been in existence for at least one year prior to the baseline assessment, and report no violent incidents with weapons in the past 6 months. A total of 303 camps were verified, of which 205 were eligible; 60 camps were randomly selected for inclusion in the study. Through member rosters completed by the leaders of these camps, 1,581 male members were identified and assessed for eligibility. To be eligible, men had to: 1) be a registered camp member for at least three months; 2) plan on residing in Dar es Salaam for the next 30 months; 3) be 15 years or older; 4) visit the camp at least once per week; and 5) be willing to provide contact information for themselves and two family members or friends to facilitate future participant contact regarding follow-up assessments for the study.

Eligible participants were asked to provide written consent, and consenting participants completed the baseline assessment in fall 2013 and a follow-up assessment 12 months after the launch of the intervention. Both questionnaires were administered by trained Tanzanian interviewers in Swahili using computer assisted personal interviewing (CAPI). A total of 1,258 men completed the baseline behavioral assessment, after which camp members from one camp (n=9) were removed from the study because of new information rendering them ineligible for participation, resulting in a final baseline sample of 1,249 men within 59 camps. 978 men in the 59 camps completed the follow-up assessment for 78% retention.

Measures

Condom use was measured as an ordered-categorical variable created from men’s self-report of condom use with up to their three most recent sexual partners over the past 12 months. For each sexual partner, men reported how many times they engaged in sex with these partners over the most recent month of the relationship, and how many of these times they used a condom. We calculated men’s proportion of condom use by dividing the number of times condoms were used by the total number of sex acts. Using these proportions, participants were assigned to one of three categories: “never use” (0% use), “some use” (greater than 0%, less than 100%), or “always use” (100%). This categorical approach is preferred to a continuous variable to minimize the effect of recall bias (Noar et al., 2006). To evaluate sexual concurrency, participants were asked to report if they had sex with anyone else during any of the same three most recent partnerships over the past 12 months. This measure was developed following best practices recommended by USAID (Zelaya et al., 2012).

Four types of norms were measured for both condom use and concurrency: friends’ reported behaviors, perceived descriptive norms, perceived injunctive norms, and friend encouragement of the behavior. Men were asked to nominate their three closest friends in their camp by selecting names from a camp roster. Each friend nomination was linked to a record of the friend’s reported behavior according to their own completed questionnaire using a unique identifier. Taking the reported behavior of all three friends for each individual, we created an average percent condom use and a percent of friends reporting concurrency measure for each participant. To assess perceived descriptive norms, men were asked for each of these three closest friends, “Do you think friend X uses condoms all the time?” For injunctive norms men were asked “Do you think friend X thinks that he should be using condoms all the time?” Finally, to assess friends’ encouragement of behaviors men were asked “Has friend X encouraged you to use condoms all the time?” Men were asked analogous questions for partner concurrency and provided yes/no answers. We created a measure of the proportion of friends for which the respondent answered “yes” for each item.

Symptoms of anxiety and depression were measured using a version of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (Hesbacher et al., 1980), that had previously been translated and validated in Tanzania (Kaaya et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2008). Participants rated a total of 25 symptoms (10 related to anxiety, 15 to depression) rated on a four-point Likert-type scale. Anxiety and depression scores were calculated by taking the mean of the corresponding 10 and 15 items, respectively. At baseline both subscales showed good internal consistency (α = 0.94 for anxiety, α = 0.91 for depression).

Covariates included in all analyses include age, education level, economic status, marital status, and treatment condition. Age was calculated based on reported date of birth, or when not available the reported age in years. Participants reported the highest level of education they had completed and responses were collapsed into three categories: primary school or less (no education, Standard 4 or less, or Standard 5–7); some secondary school (Form 1, Form 2, or Form 3); or secondary school completed or greater (Form 4 or Greater than Form 4). Socioeconomic status (SES) was evaluated through the Filmer Pritchett Wealth Index (Filmer & Pritchett, 2001). Participants indicated which of 10 assets they owned (Vyas & Kumaranayake, 2006), and a composite score was created by weighting each asset by its factor loading on the first component in a principle components analysis (Filmer & Pritchett, 2001). These scores were categorized into terciles (the lowest 33% as “lowest SES”, the highest 33% as “highest SES,” and the remainder as “middle SES”). Marital status was evaluated by asking men if they had ever been married. Finally, as the intervention being evaluated was designed to affect condom use and sexual partner concurrency, treatment condition was included as a covariate to account for this design effect in all analyses.

Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS v 9.4 and used a 2-sided significance level of 0.05. To address missing data (primarily due to attrition), we applied sequential multiple imputation using the fully conditional specification in proc MI (40 imputations, linear regression specification for continuous variables and logistic regression specification for categorical variables). To account for missing network ties in the Quadratic Assignment Procedure discussed below, we conducted imputation by reconstruction as recommended by Huisman (2009), randomly imputing ties proportionately to the observed network density.

In a previous study we found that that anxiety and depression were associated with men’s sexual risk behavior (Hill et al., 2016). In the present study we hypothesized that within-person change in behavioral norms would predict follow-up risk behavior controlling for baseline risk behavior, and that change in norms would moderate the relationship between changes in anxiety and depression, and sexual risk. To account for dependence due to clustering within camps, we fit multilevel models with a generalized link function, using proc glimmix with quadrature estimation (using 15 quadrature points), random intercepts, and logit and cumulative logit link functions (for dichotomous concurrency, and three-level condom use, respectively). For all models the dependent variable was sexual risk (condom use or concurrency) measured at the follow-up, controlling for baseline sexual risk and the covariates listed above. The primary predictors were change in each behavioral norm score, change in anxiety or depression (baseline score subtracted from follow-up score), and their interaction. In each model, the effect of only one behavioral norm score was tested at a time. Given the one-year time difference between the baseline and follow-up assessments, we selected change score exposure variables as we expected change in exposures over this time period to be more plausibly predictive than cross-sectional exposures at baseline, and more temporally informative than cross-sectional exposures at the follow-up. For each model, we assessed the interaction between mental health and peer norm change scores. Where these interaction terms were significant, we probed each significant interaction found by modeling the focal effect at the mean, one standard deviation above the mean, and one standard deviation below the mean of the moderator variable scores (Bauer & Curran, 2005).

For models including friend-reported behaviors, to adjust standard errors due to the dependence of observations we included controls for subgroup clustering within each camp. To account for such subgroups, we created a distance matrix for each camp where the cell values were the number of steps between each dyad. With each of these matrices we performed a principal components analysis to detect structurally significant subgroups within the camp, calculated the factor loading of each individual on each of the principal components, and included these factor loading terms in the models as a control (Hoff, 2011).

In a separate modeling approach to further assess the role of peer influence on condom use and concurrency in men’s full camp networks (as opposed to among men’s closest friends), we tested friendship correlations for condom use and concurrency within each of the 59 camp networks using a Quadratic Assignment Procedure (QAP), which is a non-parametric procedure for significance testing which is used to infer social influence by relating measures of structural similarity (in this case, the existence of friendship tie) between two network members to a measure of their similarity on variables of interest (Borgatti et al., 2013).

Ethical Review

The study was approved by the ethical review committees at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Individual written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

RESULTS

1249 men were interviewed at baseline, of whom 1113 (89%) reported being sexually active. 871 of these 1113 men (78%) participated at the follow-up. Men who did not participate at the follow-up did not significantly differ in their risk behavior from men who did (condom use: χ2 = 0.31, p = 0.58; concurrency OR = 0.94, p = 0.75). The 1113 men who reported being sexually active at baseline were included in the analyses presented below.

Participant characteristics

Sexually active men interviewed at baseline had an average age of 27 years (Table 1; range: 15 to 59). Over half had a primary school education or less (59%), nearly a third had graduated from secondary school (31%), and the remaining 11% had some secondary school but had not graduated. A quarter of the men had ever been married (25%) and 38% had children.

Table 1.

Baseline Participant Characteristics (n=1113).

| N (%) or Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 26.8 ± 7.1 |

| Currently in school | 97 (8.7%) |

| Education level (reference = primary school or less completed) | |

| Primary school or less | 652 (58.7%) |

| Some secondary school | 116 (10.5%) |

| Secondary school completed or greater | 342 (30.8%) |

| Socioeconomic status | |

| Lowest | 291 (26.2%) |

| Middle | 435 (39.1%) |

| Highest | 386 (34.7%) |

| Ever married | 277 (25.0%) |

| Has children | 423 (38.0%) |

Cross-sectional description and change in key variables

Men had an average score of 1.4 (range 1 to 4 with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms) for both anxiety and depression symptoms at both baseline and at the follow-up assessment (Table 2). The mean change in depression and anxiety scores were both close to zero, but there was substantial variation in change scores (−0.03 ± 0.76 for depression and −0.03 ± 0.72 for anxiety). At baseline 21% reported clinically significant symptoms of depression and 19% did for anxiety based on a standard cutoff (score ≥ 1.75; Sandanger et al., 1998). At the follow-up 20% and 16% of respondents met the criteria for depression and anxiety, respectively.

Table 2.

Cross-sectional description of key variables.

| Baseline | Follow-up | Within-person change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internalizing symptoms | |||

| Depression score (range 1–4) | 1.43 ± 0.57 | 1.42 ± 0.56 | −0.03 ± 0.76 |

| Anxiety score (range 1–4) | 1.38 ± 0.51 | 1.36 ± 0.53 | −0.03 ± 0.72 |

| Depression (score ≥ 1.75) | 237 (21.3%) | 174 (20.0%) | -- |

| Anxiety (score ≥ 1.75) | 206 (18.5%) | 141 (16.2%) | -- |

| Sexual risk | |||

| Condom use | |||

| Never | 491 (52.7%) | 408 (51.6%) | -- |

| Sometimes | 133 (14.3%) | 176 (22.3%) | -- |

| Always | 308 (33.1%) | 207 (26.2%) | -- |

| Concurrency | 193 (20.2%) | 262 (32.1%) | -- |

| Friend-reported peer norms (range 0–1) | |||

| Condom use | 0.43 ± 0.37 | 0.38 ± 0.33 | −0.06 ± 0.50 |

| Concurrency | 0.21 ± 0.30 | 0.30 ± 0.34 | 0.10 ± 0.44 |

| Perceived peer norms (range 0–1) | |||

| Descriptive condom use | 0.42 ± 0.46 | 0.54 ± 0.42 | 0.13 ± 0.57 |

| Injunctive condom use | 0.59 ± 0.46 | 0.81 ± 0.32 | 0.22 ± 0.52 |

| Condom use encouraged | 0.49 ± 0.44 | 0.66 ± 0.39 | 0.17 ± 0.55 |

| Descriptive concurrency | 0.24 ± 0.38 | 0.36 ± 0.39 | 0.11 ± 0.51 |

| Injunctive concurrency | 0.18 ± 0.33 | 0.26 ± 0.38 | 0.08 ± 0.50 |

| Concurrency discouraged | 0.39 ± 0.43 | 0.48 ± 0.41 | 0.09 ± 0.57 |

Note. Statistics are number (%) or Mean ± SD.

At the sample level, there were relatively similar levels of condom use and concurrency across the two time points. About half of men reported never using condoms at both baseline and the follow-up (53% and 52%, respectively). More men reported always using condoms at baseline than at the follow-up (33% and 26%, respectively). 14% of men reported sometimes using condoms at baseline, and this proportion increased to 22% at the follow-up. Many more men reported concurrency at the follow-up (262, 32%) than at baseline (193, 20%).

On average, men’s three closest friends reported using condoms 43% of the time at baseline and 38% of the time at the follow-up. At baseline, on average, 21% of men’s friends reported concurrency, and 30% did so at the follow-up. In comparison, at baseline, men perceived on average that 42% of their friends used condoms all the time, and that 24% of their friends had concurrent sexual partners (perceived descriptive norms). They also perceived that 59% of their friends thought that they should use condoms all the time and that only 18% would approve of them having concurrent sexual partners (perceived injunctive norms). Participants reported on average that 49% of friends had encouraged them to use condoms all the time, while 39% had discouraged them from having concurrent sexual partners. 150 (12%) men had no changes in their three closest friends named between baseline and the follow-up. 305 (35%) changed one friend, 312 (36%) changed two friends, and 141 (16%) changed all three friends.

Association between friend-reported and perceived norms

In comparing friends’ reported behaviors and men’s perceptions of behavioral norms among their friends (Table 3), none of the correlations surpassed an absolute value of 0.04. Friends’ own reports of their condom use and concurrency were not associated with men’s perceptions of their friends’ behaviors, their approval of these behaviors, or reports of their friends’ encouragement of these behaviors.

Table 3.

Baseline correlations between friend-reported and perceived norms.

| Friend-reported measure | Perceived measure | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived descriptive norm | Perceived injunctive norm | Behavior encouraged | |

| Condom use | −0.002 | 0.037 | 0.038 |

| Concurrency | 0.000 | −0.013 | −0.034 |

Behavioral similarity among camp peers

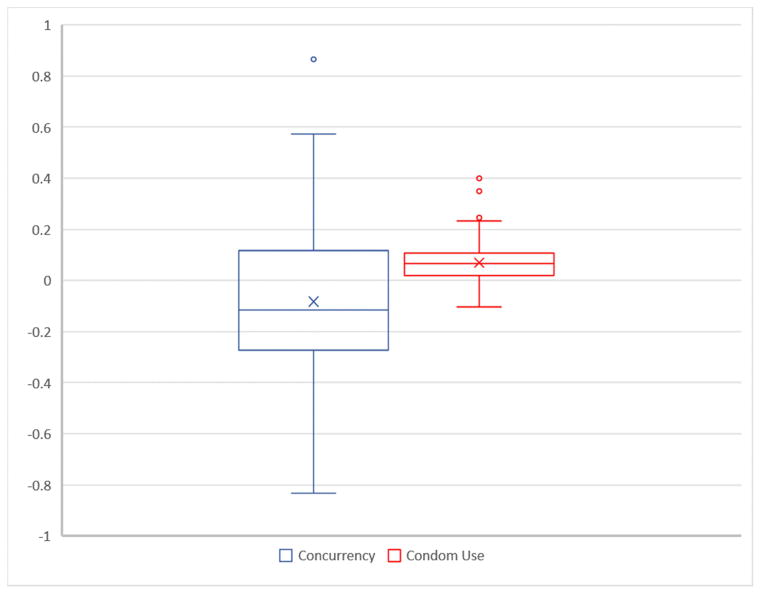

The results of the QAP analyses appear in Figure 1 as box plots of the individual results for each of the 59 camps. Overall, there was little evidence for peer similarity in concurrency or condom use at the camp level. On average, friends had 0.92 times the odds of having the same concurrency as non-friends (range: 0.43, 2.38; β(log odds)= −0.08), but the estimated association was only significant at the .05 level only for 9 (15%) camps. Friends had 0.07 greater similarity in percent condom use than non-friends (range: −0.10, 0.40), but the estimated association was only significant for 7 (12%) of camps.

Figure 1.

Box plot distributions of quadratic assignment procedure (QAP) correlations by camp

Condom use models

In assessing moderation by condom use norms of the relationship between mental health and men’s own condom use, we found that change in perceived descriptive condom use was significantly associated with men’s condom use (Table 4; aOR=1.63; 95% CI=1.20, 2.22) and significantly interacted with changes in anxiety symptoms in association with condom use (aOR=1.95; 95% CI=1.10, 3.47). Changes in friend encouragement of condom use were also significantly associated with men’s condom use (aOR=1.54; 95% CI=1.15, 2.05) and significantly interacted with changes in anxiety symptoms in association with condom use (aOR=1.75; 95% CI=1.01, 3.02). Changes in perceived injunctive condom use norms and friends’ self-reported condom use were not significantly associated with men’s own condom use and did not significantly interact with anxiety or depression change.

Table 4.

Condom use peer norm interaction model results.

|

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norm moderator

| ||||

| Descriptive condom use | Injunctive condom use | Encourage condom use | Friend-reported condom use | |

|

| ||||

| aOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | |

| Main effect model | ||||

| ΔAnxiety | 1.14 (0.86, 1.51) | 1.04 (0.76, 1.47) | 1.14 (0.86, 1.51) | 1.09 (0.79, 1.51) |

| ΔDepression | 0.71 (0.54, 0.93)* | 0.69 (0.53, 0.91)** | 0.70 (0.53, 0.91)* | 0.69 (0.50, 0.96)* |

| ΔNorm | 1.63 (1.20, 2.22)** | 1.14 (0.84, 1.55) | 1.54 (1.15, 2.05)** | 0.81 (0.55, 1.19) |

|

| ||||

| Interaction model | ||||

| ΔAnxiety | 1.07 (0.79, 1.44) | 1.11 (0.83, 1.43) | 1.04 (0.77, 1.40) | 1.09 (0.78, 1.54) |

| ΔDepression | 0.71 (0.53, 0.94)* | 0.67 (0.49, 0.91)** | 0.72 (0.54, 0.95)* | 0.69 (0.50, 0.97)* |

| ΔNorm | 1.58 (1.16, 2.15)** | 1.11 (0.82, 1.52) | 1.52 (1.14, 2.04)** | 0.81 (0.55, 1.18) |

| ΔAnxiety × ΔNorm | 1.95 (1.10, 3.47)* | 1.25 (0.71, 2.20) | 1.75 (1.01, 3.02)* | 1.03 (0.45, 2.37) |

| ΔDepression × ΔNorm | 0.79 (0.46, 1.33) | 1.10 (0.64, 1.89) | 0.78 (0.48, 1.26) | 1.05 (0.48, 2.26) |

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001;

Δ indicates change the listed variable

Note: All models include controls for condition, age, education level, SES, and ever having been married.

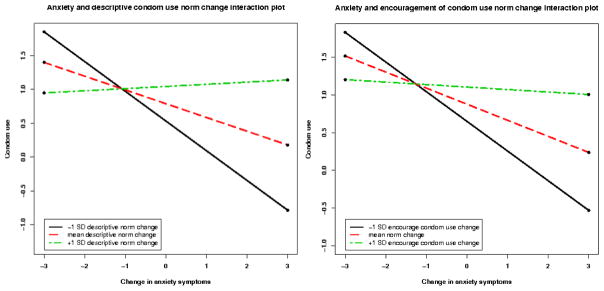

Looking specifically at the interaction between anxiety symptoms and descriptive condom use in association with men’s condom use, we present plots of the simple intercepts and slopes of the association between anxiety change and condom use, at the mean, at one standard deviation above, and at one standard deviation below the mean of each condom use norm change scores (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Condom use as a function of anxiety and peer norms.

Men with greater increases in anxiety symptoms reported lower levels of condom use at the mean level of change in perceived descriptive condom use (simple slope= −0.20, p=0.035) and in condom use encouragement (simple slope= −0.21, p=0.030). This association was amplified with decreasing/worsening perceived descriptive condom use norms (simple slope at mean - 1SD = −0.44, p=0.004) and with decreasing encouragement of condom use (simple slope at mean - 1SD = −0.39, p=0.009). The association was attenuated by increasing/improving perceived descriptive norms for condom use (simple slope at mean + 1SD = 0.03, p=0.776) and by increasing encouragement of condom use (simple slope at mean + 1SD = −0.03, p=0.761).

Concurrency models

In testing the hypotheses regarding moderation by concurrency norms in the relationship between mental health and partner concurrency, changes in perceived descriptive concurrency norms (Table 5; aOR=1.42; 95% CI=1.02, 2.00) and injunctive concurrency norms (aOR=1.50; 95% CI=1.08, 2.10) were significantly associated with men’s concurrency. However, changes in levels of concurrency discouragement and friend-reported concurrency were not significantly associated with concurrency. None of these hypothesized moderators significantly interacted with either change in anxiety or depression in association with concurrency.

Table 5.

Concurrency peer norm interaction model results.

|

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norm moderator

| ||||

| Descriptive concurrency | Injunctive concurrency | Discourage concurrency | Friend-reported concurrency | |

|

| ||||

| aOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | |

| Main effect model | ||||

| ΔAnxiety | 1.31 (0.94, 1.81) | 1.33 (0.96, 1.85) | 1.29 (0.93, 1.79) | 1.31 (0.90, 1.91) |

| ΔDepression | 1.29 (0.95, 1.74) | 1.27 (0.94, 1.72) | 1.29 (0.95, 1.75) | 1.31 (0.93, 1.84) |

| ΔNorm | 1.42 (1.02, 2.00)* | 1.50 (1.08, 2.10)* | 0.82 (0.61, 1.09) | 0.73 (0.45,1.18) |

|

| ||||

| Interaction model | ||||

| ΔAnxiety | 1.36 (0.95, 1.95) | 1.34 (0.95, 1.88) | 1.28 (0.92, 1.78) | 1.33 (0.90, 1.96) |

| ΔDepression | 1.31 (0.95, 1.81) | 1.30 (0.94, 1.78) | 1.30 (0.96, 1.76) | 1.28 (0.90, 1.81) |

| ΔNorm | 1.50 (1.06, 2.11)* | 1.57 (1.12, 2.20)** | 0.79 (0.60, 1.06) | 0.71 (0.44,1.17) |

| ΔAnxiety × ΔNorm | 0.73 (0.37, 1.47) | 0.90 (0.46, 1.77) | 1.05 (0.55, 2.03) | 0.76 (0.29, 2.01) |

| ΔDepression × ΔNorm | 0.90 (0.46, 1.75) | 0.79 (0.42, 1.51) | 1.17 (0.66, 2.07) | 1.54 (0.60, 3.95) |

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001;

Δ indicates change the listed variable

Note: All models include controls for condition, age, education level, SES, and ever having been married.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate that changes in perceived norms of behaviors among men’s closest friends are associated with men’s own condom use and concurrency behaviors. Specifically, perceived descriptive norms were associated with both condom use and concurrency, perceived injunctive norms were associated with concurrency, and direct encouragement was associated with condom use. Changes in perceived condom use norms (descriptive norms and reported encouragement) also interacted with changes in anxiety symptoms to shape condom use. Perceived norms and the self-reported behaviors of men’s closest friends were not significantly correlated. Changes in the self-reported behaviors of men’s closest friends were also not associated with men’s own behaviors. Further, there was no observed similarity in these behaviors in men’s larger camp friendship networks.

We found multiple significant associations between men’s perceptions of behavioral norms among their closest friends and their own behaviors. Such perceptions can affect behavior as a normative behavior is seen as the “correct” thing to do in a given social context (Cialdini & Trost, 1998). People may also anticipate social acceptance or increase in social status as a result of assuming a normative behavior (Bandura & McClelland, 1977; Heilbron & Prinstein, 2008). Motivation to adhere to the norm may even increase when peers directly reinforce perceptions of anticipated social rewards e.g. through direct encouragement (Brechwald & Prinstein, 2011). Among men’s closest friends, we found that both perceived descriptive norms and friends’ encouragement were associated with men’s condom use, and descriptive and injunctive norms were associated with concurrency. While it appears that men’s perceptions of their friends’ adoption of behaviors (descriptive norms) are related to both condom use and concurrency, future studies should attempt to understand why direct encouragement may be related to condom use but not concurrency, and why perceptions of what behaviors friends find acceptable (injunctive norms) may be related to men’s concurrency but not condom use.

We also found that descriptive condom use norms and encouragement to use condoms interacted with anxiety to shape condom use. As expected, with worsening condom use norms the risk relationship between anxiety and condom use was amplified, and with improving condom use norms the risk relationship between anxiety and condom use was attenuated. This interaction between mental health and peer norms can be understood through the fact that peer influence not only acts to directly shape behavior but peers may serve as a reference groups which individuals look to in behavioral decision-making (Kemper, 1968). In this way, higher levels of risk behaviors and approval thereof among direct peers will serve to magnify individual-level risks, such as those posed by poor mental health. Our results echo previous findings related to mental health, behavioral norms, and alcohol use (Buckner et al., 2011; Pedersen et al., 2013), and provide novel evidence of the interaction between mental health and sexual behavior norms. As we only found interactions in the relationship between anxiety and condom use, future studies should seek to understand why perceived norms might not interact with depression to shape young men’s sexual behaviors, and why norms related to concurrency may not magnify the relationship between mental health and concurrency as they seem to do for condom use.

While we found numerous associations between changes in perceived norms and men’s behavior, we found no support for the association between men’s behavior and changes in the self-reported behaviors of men’s closest friends or in their larger camp friendship networks. These results were surprising given previous studies which have found that individuals’ sexual behaviors, including partner concurrency (Catania et al., 1989) and condom use (DiClemente, 1991; Romer et al., 1994; Zapka et al., 1993), reflect their peers’ behavior. It is possible that men have other important friendships outside of their camps which may be more relevant to their sexual behavior than camp friendships. However, the fact that men’s perceptions of camp friends’ behaviors were associated with their own behaviors gives precedence rather to the hypothesis that men’s perceptions of their friends’ behaviors simply did not match their friends’ actual behaviors.

To this point, we found no significant correlations between men’s perceptions of their friends’ behaviors and their friends’ own self-reported behaviors, similar to previous findings in this population with regard to perceptions of friends’ HIV testing (Mulawa, Yamanis, Balvanz et al., 2016). Such a finding is not entirely surprising, as individuals’ perceptions of norms are related to observable peer behaviors, but these perceptions rarely match what peers are actually doing as perceptions of norms are filtered through each individual’s unique position and perspective (Tankard & Paluck, 2016). Previous research has shown that individuals tend to underestimate their peers’ protective behaviors and overestimate their risky behaviors (Black et al., 2013). Other studies have observed a false consensus effect, or a tendency to misperceive peer behavior in a direction that is that is consistent with one’s own behavior (Prinstein & Wang, 2005; Ross et al., 1977). Further, as people have limited opportunity to observe their friends’ behaviors, they often use availability heuristics to interpret norms from memories of observed behaviors that are most readily available (Fiske & Taylor, 1984). For example, a peer who has a second concurrent partner may draw more interest or attention than peers who have only one partner, making the examples of concurrency more cognitively available.

Taken together, these perceptual biases could explain the fact that men’s perceived norms did not correlate with directly friends’ self-reported behaviors, and may explain the observed relationship between perceived norms and men’s own behaviors. Though the change predictors included in our models indicate that within-individual changes in perceived norms were associated with men’s behaviors, future research is needed to better determine the temporality of these relationships, that is, to determine if changes in perceived norms precede changes in behaviors or vice versa. It is also possible that norms and behaviors are mutually deterministic, that norms shape behaviors and perceived norms may in turn be revised to align more closely with one’s own behaviors. A better understanding of these relationships is needed to inform norm change interventions, such as popular opinion leader interventions which aim to leverage the normative influence of key community members often used to target HIV risk behaviors (Jones et al., 2008; Kelly et al., 1997; Sikkema et al., 2000).

Limitations

There are important limitations to this study. Respondents’ willingness to report sexual risk behaviors may have been associated with the social acceptability of such an acknowledgment. Reports of sexual risk behaviors were retrospective, creating the opportunity for recall bias. Recall may have been more difficult in reporting condom use over 30 days of sexual contact than in reporting any concurrent sexual encounter over the course of a relationship, making recall bias a potentially larger issue in measuring condom use than partner concurrency. Given this potential reporting bias, the coding of the sexual behavior variables was designed to minimize this issue as discussed in the Methods. The HSCL-25 scale which was used to measure anxiety and depression was developed in a different cultural context than the study setting, though the scale version used has been previously validated in Tanzania (Kaaya et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2008). We were unable to represent all of the influence of peers in men’s lives beyond camp relationships, thus the results of this study can only represent the normative context within camps. Nevertheless, these camps reflect an important peer groups for their members. There was approximately 22% attrition in the analytic sample at the follow-up assessment. While loss to follow-up might be speculated to occur among men with the poorer mental health and more sexual risk, men who did not participate at the follow-up did not significantly differ in their risk behavior from men who did (condom use: χ2 = 0.31, p = 0.58; concurrency OR = 0.94, p = 0.75). Furthermore, the application of multiple imputation served to minimize the influence of any potential bias from loss to follow-up. Finally, with the present data we cannot say if changes in norms and mental health preceded changes in men’s sexual behaviors. Experimental research with successful manipulation of perceived norms is needed to better determine the temporal direction of a potential causal relationship between perceived norms and these behaviors.

Implications for future research and intervention

Future studies should seek to understand why different perceived descriptive, injunctive, and encouragement norms are more closely related to condom use or concurrency, and why perceived behavioral norms would interact with anxiety but not depression to shape sexual risk behaviors. A better understanding of these relationships and potential mechanisms explaining them would help to understand how to target different types of norms for different behaviors to optimize HIV prevention interventions. Scientists should also seek to understand what shapes men’s perceptions of their friends’ behaviors if not their friends’ actual behaviors. Such an understanding would help to identify other potential important psychosocial targets for behavioral interventions. Future HIV prevention interventions should consider the importance of targeting perceived social norms and mental health simultaneously, as our results indicate that these factors act together to shape sexual behavior. In norms-focused interventions, it will be important to consider how participants’ mental health, specifically anxiety, could affect the success of the intervention. In programs aiming to promote mental health, interventionists should consider the additional importance of condom use and concurrency norms, and aim to target perceptions of risky norms to prevent risk behaviors in high HIV prevalence populations. These measures will be particularly important among marginalized populations similar to the camps in the study, as men is these contexts may be exposed to multiple susceptibilities to risk behavior, including poor mental health and risky social norms.

As we found that men’s perceptions of peer behaviors did not match their friends’ actual behaviors, social norms interventions aiming to prevent sexual risk should consider promoting less risky perceived norms rather than or in addition to targeting the behavior of influential individuals. One successful approach to promoting realistic perceptions of peer behaviors and attitudes toward risky behaviors is found in myth-busting interventions (Stewart et al., 2002). In one example, a brief intervention in which university students were asked to estimate condom use and concurrency levels among their peers, and then to compare these estimates to actual data from a campus survey, was effective in increasing condom use and reducing partner concurrency (Chernoff & Davison, 2005). Where risk behavior data from a salient peer reference group are available, the efficacy of this type of intervention should be evaluated among marginalized youth.

Conclusion

In this study of sexual risk behaviors among young men living in Dar es Salaam, we found that perceived norms affected young men’s behaviors, and that these norms interacted with anxiety to shape sexual risk. We further found that perceived norms may not reflect actual peer behaviors, and found no evidence of peer influence in comparing self-reported behaviors among men’s closest friends and in their larger friendship networks. The results of this study provide novel evidence of the interacting effects of poor mental health and risky perceived norms among a hard-to-reach population of marginalized young men in Dar es Salaam. As such susceptibilities are common in the many informal settlements throughout eastern and southern Africa, our findings provide important information for future norms-based and mental health promotion interventions targeting HIV prevention in this key population.

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS.

Assessed interaction of co-occurring risk factors: mental health and peer norms

Men’s perceptions of peer norms do not match peers’ reported behaviors

Changes in perceived descriptive norms and peer encouragement linked to condom use

Increased anxiety coupled with riskier peer norms meant less condom use

Changes in perceived norms was associated with partner concurrency

Acknowledgments

Sources of support: This research was made possible by funding from The National Institute of Mental Health (1R01MH098690-01) and The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (T32AI007001-39). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akers AY, Muhammad MR, Corbie-Smith G. “When you got nothing to do, you do somebody”: A community’s perceptions of neighborhood effects on adolescent sexual behaviors. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72(1):91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachanas PJ, Morris MK, Lewis-Gess JK, Sarett-Cuasay EJ, Flores AL, Sirl KS, et al. Psychological adjustment, substance use, HIV knowledge, and risky sexual behavior in at-risk minority females: Developmental differences during adolescence. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27(4):373–384. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.4.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, McClelland DC. Social learning theory. 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Barker G, Ricardo C. Young men and the construction of masculinity in sub-Saharan Africa: Implications for HIV/AIDS, conflict, and violence. World Bank; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Curran PJ. Probing interactions in fixed and multilevel regression: Inferential and graphical techniques. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2005;40(3):373–400. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4003_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Zimmerman MA, Caldwell CH. Neighborhood disadvantage and changes in condom use among African American adolescents. Journal of Urban Health. 2011;88(1):66–83. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9506-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumer E, South S. Community effects on youth sexual activity. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63(2):540–554. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DL, Bauman A. Adolescent mental health and risky sexual behaviour: Young people need health care that covers psychological, sexual, and social areas. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed) 2000;321(7256):251–252. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7256.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernburg JG, Thorlindsson T. Violent values, conduct norms, and youth aggression: A multilevel study in Iceland. The Sociological Quarterly. 2005;46(3):457–478. [Google Scholar]

- Black SR, Schmiege S, Bull S. Actual versus perceived peer sexual risk behavior in online youth social networks. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2013;3(3):312–9. doi: 10.1007/s13142-013-0227-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti SP, Everett MG, Johnson JC. Analyzing social networks. SAGE Publications Limited; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L, Neilands TB, Tabb LP, Burkholder GJ, Malebranche DJ, Tschann JM. Neighborhood context and black heterosexual men’s sexual HIV risk behaviors. AIDS and Behavior. 2014;18(11):2207–2218. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0803-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brechwald WA, Prinstein MJ. Beyond homophily: A decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21(1):166–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning C, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Neighborhood context and racial differences in early adolescent sexual activity. Demography. 2004;41(4):697–720. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Ecker AH, Proctor SL. Social anxiety and alcohol problems: The roles of perceived descriptive and injunctive peer norms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25(5):631–638. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Coates TJ, Greenblatt RM, Dolcini MM, Kegeles SM, Puckett S, et al. Predictors of condom use and multiple partnered sex among sexually-active adolescent women. Implications for aids-related health interventions 1989 [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff R, Davison G. An evaluation of a brief HIV/AIDS prevention intervention for college students using normative feedback and goal setting. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2005;17(2):91–104. doi: 10.1521/aeap.17.3.91.62902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Reno RR, Kallgren CA. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58(6):1015. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Trost MR. Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Curry A, Latkin C, Davey-Rothwell M. Pathways to depression: The impact of neighborhood violent crime on inner-city residents in Baltimore, Maryland, USA. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar es Salaam City Council. City profile for dar es salaam, united republic of tanzania. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Davey-Rothwell MA, Siconolfi DE, Tobin KE, Latkin CA. The role of neighborhoods in shaping perceived norms: An exploration of neighborhood disorder and norms among injection drug users in Baltimore, MD. Health & Place. 2015;33:181–186. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ. Predictors of HIV-preventive sexual behavior in a high-risk adolescent population: The influence of perceived peer norms and sexual communication on incarcerated adolescents’ consistent use of condoms. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1991;12(5):385–390. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(91)90052-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Nduna M, Levin J, Jama N, Khuzwayo N, et al. Perpetration of partner violence and HIV risk behaviour among young men in the rural Eastern Cape, South Africa. AIDS. 2006;20(16):2107–2114. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247582.00826.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data—Or tears: An application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography. 2001;38(1):115–132. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST, Taylor SE. Social cognition reading. MA: Addison-Wesley; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano PC. Relationships in adolescence. Annual Review of Sociology. 2003:257–281. [Google Scholar]

- Greif MJ, Dodoo FN, Jayaraman A. Urbanisation, poverty and sexual behaviour: The tale of five African cities. Urban Studies. 2010;48(5):947–957. doi: 10.1177/0042098010368575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding DJ. Collateral consequences of violence in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Social Forces. 2009;88(2):757–784. doi: 10.1353/sof.0.0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilbron N, Prinstein MJ. Peer influence and adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: A theoretical review of mechanisms and moderators. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 2008;12(4):169–177. [Google Scholar]

- Hesbacher PT, Rickels K, Morris RJ, Newman H, Rosenfeld H. Psychiatric illness in family practice. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1980;41(1):6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill LM, Maman S, Kilonzo MN, Kajula LJ. Anxiety and depression strongly associated with sexual risk behaviors among networks of young men in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. AIDS Care. 2016;29(2):252–258. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1210075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff PD. Hierarchical multilinear models for multiway data. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis. 2011;55(1):530–543. [Google Scholar]

- Huisman M. Imputation of missing network data: Some simple procedures. Journal of Social Structure. 2009;10(1):1–29. [Google Scholar]

- ICF International. Tanzania HIV/AIDS and malaria indicator survey. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- ICF Macro. Tanzania demographic and health survey, 2010. National Bureau of Statistics; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Idele P, Gillespie A, Porth T, Suzuki C, Mahy M, Kasedde S, et al. Epidemiology of HIV and AIDS among adolescents: Current status, inequities, and data gaps. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2014;66(Suppl 2):S144–53. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KT, Gray P, Whiteside YO, Wang T, Bost D, Dunbar E, et al. Evaluation of an HIV prevention intervention adapted for black men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(6):1043–1050. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.120337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaaya SF, Fawzi MC, Mbwambo JK, Lee B, Msamanga GI, Fawzi W. Validity of the Hopkins symptom checklist-25 amongst HIV-positive pregnant women in Tanzania. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2002;106(1):9–19. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.01205.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajula L, Balvanz P, Kilonzo MN, Mwikoko G, Yamanis T, Mulawa M, et al. Vijana vijiweni II: A cluster-randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of a microfinance and peer health leadership intervention for HIV and intimate partner violence prevention among social networks of young men in Dar es Salaam. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2774-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, Murphy DA, Sikkema KJ, McAuliffe TL, Roffman RA, Solomon LJ, et al. Randomised, controlled, community-level HIV-prevention intervention for sexual-risk behaviour among homosexual men in US cities. The Lancet. 1997;350(9090):1500–1505. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)07439-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper TD. Reference groups, socialization and achievement. American Sociological Review. 1968:31–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Kaaya SF, Mbwambo JK, Smith-Fawzi MC, Leshabari MT. Detecting depressive disorder with the Hopkins symptom checklist-25 in Tanzania. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2008;54(1):7–20. doi: 10.1177/0020764006074995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod J. Ain’t no makin’it: Leveled aspirations in a low-income neighborhood. Westview Press; Boulder, CO: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Magadi MA. The disproportionate high risk of HIV infection among the urban poor in sub-saharan africa. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(5):1645–1654. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0217-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morello-Frosch R, Zuk M, Jerrett M, Shamasunder B, Kyle AD. Understanding the cumulative impacts of inequalities in environmental health: Implications for policy. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2011;30(5):879–887. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulawa M, Yamanis TJ, Balvanz P, Kajula LJ, Maman S. Comparing perceptions with actual reports of close friend’s HIV testing behavior among urban Tanzanian men. AIDS and Behavior. 2016;20(9):2014–2022. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1335-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulawa M, Yamanis TJ, Hill LM, Balvanz P, Kajula LJ, Maman S. Evidence of social network influence on multiple HIV risk behaviors and normative beliefs among young tanzanian men. Social Science & Medicine. 2016;153:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics. Tanzania integrated labour force survey 2014. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Cole C, Carlyle K. Condom use measurement in 56 studies of sexual risk behavior: Review and recommendations. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2006;35(3):327–345. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Morokoff PJ. The relationship between masculinity ideology, condom attitudes, and condom use stage of change: A structural equation modeling approach. International Journal of Men’s Health. 2002;1(1):43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Oostveen T, Knibbe R, DeVries H. Social influences on young adults’ alcohol consumption: Norms, modeling, pressure, socializing, and conformity. Addictive Behaviors. 1996;21(2):187–197. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, Miles JN, Hunter SB, Osilla KC, Ewing BA, D’Amico EJ. Perceived norms moderate the association between mental health symptoms and drinking outcomes among at-risk adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74(5):736. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince DM, Epstein M, Nurius PS, Gorman-Smith D, Henry DB. Reciprocal effects of positive future expectations, threats to safety, and risk behavior across adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2016:1–14. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1197835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Wang SS. False consensus and adolescent peer contagion: Examining discrepancies between perceptions and actual reported levels of friends’ deviant and health risk behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33(3):293–306. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3566-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Santana MC, La Marche A, Amaro H, Cranston K, Silverman JG. Perpetration of intimate partner violence associated with sexual risk behaviors among young adult men. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(10):1873–1878. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.081554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins RN, Bryan A. Relationships between future orientation, impulsive sensation seeking, and risk behavior among adjudicated adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004;19(4):428–445. doi: 10.1177/0743558403258860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romer D, Black M, Ricardo I, Feigelman S, Kaljee L, Galbraith J, et al. Social influences on the sexual behavior of youth at risk for HIV exposure. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(6):977–985. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.6.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross L, Greene D, House P. The “false consensus effect”: An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1977;13(3):279–301. [Google Scholar]

- Sandanger I, Moum T, Ingebrigtsen G, Dalgard O, Sørensen T, Bruusgaard D. Concordance between symptom screening and diagnostic procedure: The Hopkins symptom checklist-25 and the composite international diagnostic interview I. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1998;33(7):345–354. doi: 10.1007/s001270050064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikkema KJ, Kelly JA, Winett RA, Solomon LJ, Cargill VA, Roffman RA, et al. Outcomes of a randomized community-level HIV prevention intervention for women living in 18 low-income housing developments. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(1):57–63. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DM, Elander J. Effects of area and family deprivation on risk factors for teenage pregnancy among 13–15-year-old girls. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2006;11(4):399–410. doi: 10.1080/13548500500429353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South SJ, Baumer EP, Lutz A. Interpreting community effects on youth educational attainment. Youth & Society. 2003;35(1):3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart LP, Lederman UC, Golubow M, Cattafesta JL, Goodhart FW, Powell RL, et al. Applying communication theories to prevent dangerous drinking among college students: The RU SURE campaign. Communication Studies. 2002;53(4):381–399. [Google Scholar]

- Tankard ME, Paluck EL. Norm perception as a vehicle for social change. Social Issues and Policy Review. 2016;10(1):181–211. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. The gap report. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World urbanization prospects: The 2014 revision. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme. Tanzania: Dar es Salaam city profile; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vyas S, Kumaranayake L. Constructing socio-economic status indices: How to use principal components analysis. Health Policy and Planning. 2006;21(6):459–468. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czl029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis AB, Winch PJ, O’Campo PJ. “This is not a well place”: Neighborhood and stress in Pigtown. Health Care for Women International. 2010;31(2):113–130. doi: 10.1080/07399330903042815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir SS, Pailman C, Mahlalela X, Coetzee N, Meidany F, Boerma JT. From people to places: Focusing AIDS prevention efforts where it matters most. AIDS. 2003;17(6):895–903. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000050809.06065.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy. University of Chicago Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yamanis TJ, Maman S, Mbwambo JK, Earp JAE, Kajula LJ. Social venues that protect against and promote HIV risk for young men in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71(9):1601–1609. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapka JG, Stoddard AM, McCusker J. Social network, support and influence: Relationships with drug use and protective AIDS behavior. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelaya CE, Go VF, Davis WW, Celentano DD. Improving the validity of self-reported sexual concurrency in South Africa. USAID; 2012. [Google Scholar]