Abstract

Protein tyrosine phosphatase nonreceptor type 2 (PTPN2) has been identified as an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) candidate gene. However, the mechanism through which mutations in the PTPN2 gene contribute to the pathogenesis of IBD has not been identified. PTPN2 acts as a negative regulator of signaling induced by the proinflammatory cytokine, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ). IFN-γ is known not only to play an important role in the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease (CD), but also to increase permeability of the intestinal epithelial barrier. We have shown that PTPN2 protects epithelial barrier function by restricting the capacity of IFN-γ to increase epithelial permeability and prevent induction of expression of the pore-forming protein, claudin-2. These data identify an important functional role for PTPN2 as a protector of the intestinal epithelial barrier and provide clues as to how PTPN2 mutations may contribute to the pathophysiology of CD.

Keywords: IFN-γ, STAT proteins, claudin-2, Crohn’s disease

Introduction

The protein product of the protein tyrosine phosphatase nonreceptor type 2 (PTPN2) gene, referred to as T cell protein tyrosine phosphatase (TCPTP), is a ubiquitously expressed classical phosphatase that was originally cloned in T lymphocytes.1,2 TCPTP exists in two different splice forms: a 45 kD (TC-45) isoform that contains a nuclear localization signal and can shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, and a cytoplasmic 48 kD (TC-48) variant that is targeted to the endoplasmic reticulum.3–5 Several important tyrosine kinase receptors and signaling intermediates are recognized substrates known to be dephosphorylated by TCPTP. These include the epidermal growth factor receptor, the insulin receptor, and the signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) 1 and STAT3.3,4,6–9 Thus, TCPTP acts as an important negative regulator of a number of signaling events, including signaling mediated by the inflammatory cytokines, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), and interleukin (IL)-6.8,10

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), comprising Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), is a chronic intestinal inflammatory condition that arises through a combination of genetic, immunological, bacterial, and environmental factors.11 There is increasing evidence of a major role for an epithelial barrier defect, coincident with an inappropriate immune response to commensal bacteria, as a critical contributor to the development of chronic intestinal inflammation in the pathogenesis of IBD.12 In addition to allowing increased access of bacteria and bacterial products to the lamina propria and triggering an immune cell response, decreased epithelial barrier function may also have a role in the loss of fluid and electrolytes into the lumen and thus contribute directly to the major clinical symptom of CD, diarrhea. With respect to their pathologies, both CD and UC are characterized by specific cytokine profiles with CD in particular being associated with elevated levels of IFN-γ.12,13 IFN-γ is the major effector cytokine of Th1- and, possibly, Th17-mediated immune responses.14 With respect to its involvement in IBD pathogenesis, in addition to its role(s) in tissue destruction, IFN-γ can also induce more discreet effects on intestinal epithelial cells by reducing epithelial barrier function via signaling pathways that lead to a reconfiguration of tight junctions (TJs).15,16

Recent advances in our understanding of genetic mutations associated with IBD, starting with the discovery of the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein (NOD)-2 mutation through to multiple genome-wide array studies, have greatly illuminated the genetic component of IBD pathogenesis. A number of studies have identified single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in the gene locus encoding PTPN2 that are associated not just with CD and UC, but also with type I diabetes and celiac disease.17–20 However, the functional role(s) for TCPTP and mutations in the PTPN2 gene in the pathogenesis of these conditions have not been determined. Given the role of TCPTP as a negative regulator of IFN-γ signaling, we therefore set out to investigate if PTPN2 (TCPTP) plays a protective role in preserving a critical function of intestinal epithelial cells, the ability to form an effective barrier, from the deleterious effects of IFN-γ.

We identified that TCPTP is upregulated both in intestinal epithelial cell (IECs) following IFN-γ treatment and in CD patient biopsies. We also determined that TCPTP acts as a protective factor to restrict IFN-γ–induced epithelial barrier dysfunction in part through prevention of expression of the pore-forming protein, claudin-2. These data suggest that PTPN2 mutations, leading to a loss of function, could contribute to the pathogenesis of IBD.

Methods

Human colonic T84 and HT29.cl19A epithelial cell lines were cultured on 12 mm Millicell-HA semipermeable filter supports. siRNA transfection was performed using the Amaxa (Lonza; Allendale, NJ, USA) nucleofector system. Human studies were conducted with full Institutional Review Board approval. Western blotting, real-time polymerase chain reaction, immunofluorescence staining, and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran (10 kD) permeability assays were performed as described previously.21 Transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) was measured using an Evom voltohmeter (World Precision Instruments, Inc., Sarasota, FL, USA).

Results

TCPTP expression is increased in CD and by IFN-γ in IEC

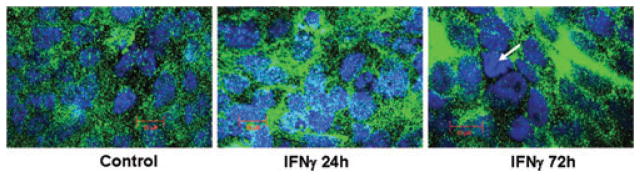

To establish a clinical association between TCPTP expression and IBD, we determined TCPTP mRNA levels in human biopsies obtained from (1) macroscopically noninflamed areas of the terminal ileum, colon, or rectum of CD patients in clinical and macroscopic remission; (2) macroscopically inflamed areas of the terminal ileum and colon of CD patients with clinically and macroscopically active disease; or (3) healthy control subjects undergoing routine colon cancer screening. We found that TCPTP mRNA was significantly elevated in tissue samples of CD patients with acute inflammation (P < 0.05 vs. control), but not in CD patients in remission.21 We next investigated whether a major inflammatory cytokine involved in CD, IFN-γ, directly affects TCPTP expression in intestinal epithelial cells. Confluent monolayers of T84 cells, a colonic crypt epithelial cell line, were treated with IFN-γ (10; 100; 1000; 3000 U/mL) for 24 hours. IFN-γ significantly increased TCPTP mRNA expression with a peak occurring at 1,000–3,000 U/mL.21 Using 1,000 U/mL of IFN-γ, a concentration that has been detected in biopsy cultures from a patient with active CD,22 we also observed that a significant increase in TCPTP mRNA occurred not just at 24 h but also at 48- and 72-h posttreatment versus control cells treated with medium alone. Protein expression was also assessed by Western blotting. Dose–response studies revealed that a concentration of 1,000 U/mL IFN-γ caused a maximal increase in TCPTP protein by 24-h IFN-γ treatment. A sustained increase in cytoplasmic TCPTP protein was observed from 24 to 72 hours, but a drop in nuclear TCPTP occurred after 24 h.21 The decrease in nuclear TCPTP at later time points correlated with immunofluorescent staining, which indicated nuclear exit of TCPTP at 72 h (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

IFN-γ affects TCPTP distribution over time in T84 IEC. Confocal microscopy shows TCPTP (green) distribution in control (24 hours) and IFN-γ (1000 U/mL) treated (24 and 72 hours) T84 cells. Nuclear staining is blue. Individual panels show an image for one experiment representative of three separate experiments for each condition. TCPTP is increased in both cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments after 24-hour IFN-γ but a loss of nuclear TCPTP occurs by 72 hours (arrow).

TCPTP activity negatively regulates IFN-γ signaling in IECs

In addition to demonstrating that IFN-γ increases transcription and expression of TCPTP, we also investigated whether IFN-γ alters the enzymatic activity of TCPTP. We observed that IFN-γ increases TCPTP activity maximally within 72 hours of treatment in TCPTP immunoprecipitates isolated from T84 whole cell lysates.21 To study the effects of TCPTP activity on IFN-γ signaling, we examined the tyrosine phosphorylation status of the IFN-γ downstream targets, and TCPTP substrates, STAT1 and STAT3. IFN-γ treatment for 24 h increased both cytoplasmic and nuclear STAT1 phosphorylation on tyrosine,701 but also elevated STAT1 expression as determined by Western blotting.21 Nuclear STAT1 phosphorylation declined markedly at 48-hour IFN-γ treatment and returned to control levels by 72 h, suggesting that TCPTP significantly dephosphorylates STAT1 in the nucleus as early as 24–48 h after IFN-γ treatment (P < 0.001; not shown). In contrast, cytoplasmic STAT1 phosphorylation was still significantly elevated even at 48-h treatment (P < 0.05). This difference in dephosphorylation in nuclear versus cytoplasmic fractions may partly be explained by the increased enzymatic activity of the nuclear 45 kD isoform of TCPTP.8 Dephosphorylation of cytoplasmic p-STAT1 after 48 h may also be assisted by nuclear exit of the 45 kD form of TCPTP. By extension, the delayed increase in TCPTP activity, which conflicts with increased TCPTP expression at 24 h, may be due to whole cell lysates used for the TCPTP activity assay containing only a small portion of the nuclear protein fraction (not shown). Similar data were obtained regarding IFN-γ–induced phosphorylation of tyrosine705 on cytoplasmic STAT3.21 Overall, these data indicated that basal and IFN-γ–induced TCPTP activity correlates with decreased phosphorylation of STAT proteins.

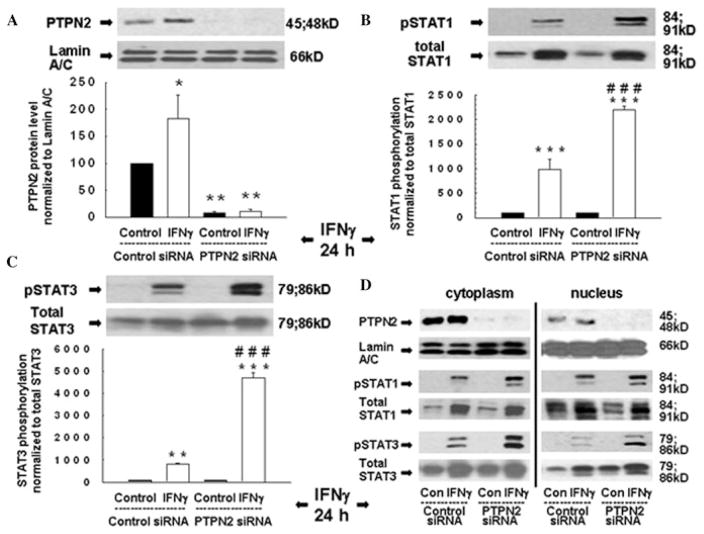

We next investigated whether knockdown of TCPTP influenced IFN-γ–induced STAT1 and STAT3 activity. T84 cells were transfected with either PTPN2-specific siRNA or nonspecific control siRNA sequences, cultured on semipermeable supports for 48 h and then treated with IFN-γ (24 hours) or medium. Transfection of PTPN2 siRNA reduced TCPTP expression with a maximal reduction of 92 ± 3% (Fig. 2A), while levels of the nuclear envelope protein lamin A/C and total STAT1 and STAT3 were unaffected (Fig. 2A–C). As expected, IFN-γ increased TCPTP protein (Fig. 3A) as well as STAT1 and STAT3 phosphorylation, while nuclear and cytoplasmic STAT1 and 3 phosphorylation were significantly increased in TCPTP-deficient cells treated with IFN-γ (Fig. 2B and C). siRNA-induced knockdown of TCPTP in HT29cl.19a cells revealed the same regulatory influence of TCPTP on STAT1 phosphorylation (not shown).21 These data suggest that TCPTP is a key negative regulator of IFN-γ–induced STAT signaling in IEC.

Figure 2.

Loss of TCPTP promotes IFN-γ–stimulated STAT activation. T84 cells were transfected with either nonspecific siRNA or PTPN2 siRNA and treated with IFN-γ (24 h) before generation of whole cell lysates. (A) Representative Western blots and densitometry for TCPTP (PTPN2) and lamin A/C (n = 3); (B, C) STAT1 and STAT3 phosphorylation and expression, respectively (n = 3). Asterisks indicate significant differences versus the respective control (*P < 0.05, * *P < 0.01, * * *P < 0.001). ###P < 0.001 versus 24-h IFN-γ treatment of control siRNA-transfected cells. (D) Representative Western blots showing TCPTP (PTPN2) and lamin A/C expression, STAT1 and STAT3 expression and phosphorylation, in cytoplasmic and nuclear lysates (n = 2). Reproduced from Ref. 21, with permission from Elsevier.

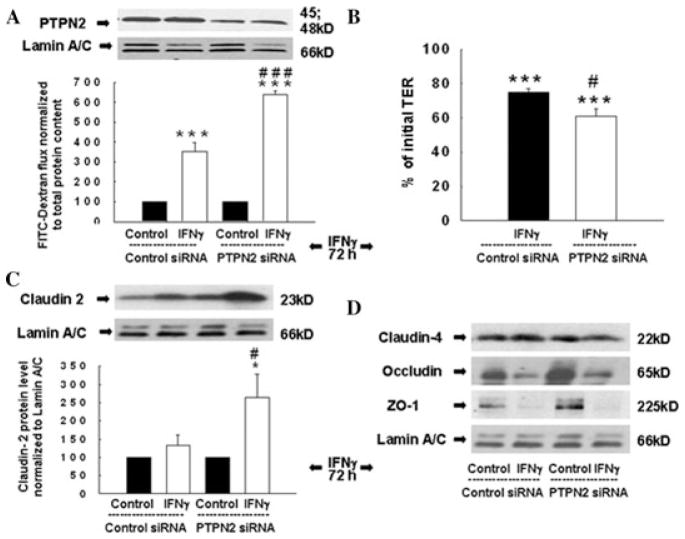

Figure 3.

TCPTP knockdown exacerbates IFN-γ –induced barrier defects. (A, B) Western blots showing decreased TCPTP but not lamin A/C protein in TCPTP-deficient T84 cells after IFN-γ (72 h) treatment. (A) FITC-dextran flux (n = 3) and (B) TER (n = 3) across T84 monolayers transfected with control or PTPN2 siRNA. (C) Western blot and densitometric analysis of claudin-2 expression in control or PTPN2 siRNA-transfected cells in response to IFN-γ (n = 3). (D) Western blots of claudin-4, occludin, and ZO-1 expression in control or PTPN2 siRNA-transfected T84 cells (n = 3). Asterisks indicate significant differences versus the respective control (*P < 0.05, * * *P < 0.001). #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001 versus 72-h IFN-γ treatment of control siRNA cells. Adapted from Ref. 21, with permission from Elsevier.

Loss of TCPTP elevates epithelial permeability

We next investigated the role of TCPTP in regulating IFN-γ–induced alterations in barrier function. We measured epithelial permeability by quantifying the flux of 10 kD FITC-Dextran across T84 and HT29cl.19a monolayers, transfected with either control or PTPN2-specific siRNA and subsequently treated with IFN-γ (72 hours). Although IFN-γ significantly increased permeability in cells transfected with nonspecific siRNA, TCPTP knockdown further exacerbated IFN-γ–induced barrier defects in both T84 (P < 0.001; n = 3; Fig. 3A) and HT29cl.19A (P < 0.01; n = 4) cell lines.21 Moreover, TCPTP knockdown further exaggerated the IFN-γ–induced decrease in TER across T84 monolayers (P < 0.05; n = 3; Fig. 3B). These data indicate that TCPTP plays a key role in restricting intestinal epithelial barrier defects induced by inflammatory cytokines.

We subsequently explored molecular targets that may be affected more prominently in TCPTP-deficient cells versus TCPTP-competent cells in response to IFN-γ and may contribute to the greater defect in barrier function. Members of the claudin family can act either as sealing proteins, to enhance barrier function, or to form cation-selective pores that increase the electrolyte permeability of the TJ. Claudin-2 is a pore-forming protein that plays an important role in regulating epithelial permeability in CD and UC and whose expression is increased in IBD.23–25 IFN-γ does not increase claudin-2 expression in IEC lines and we observed that in T84 cells transfected with control siRNA, IFN-γ treatment did not affect claudin-2 expression.25,26 However, in parallel with the rise in epithelial permeability, IFN-γ significantly increased expression of claudin-2 in TCPTP-deficient cells (Fig. 3C). The TJ protein, occludin, and the TJ-associated molecule zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) are known to be affected by inflammatory cytokines, including IFN-γ.27,28 Although the expression of ZO-1 and occludin was reduced by IFN-γ as expected, levels were not further decreased by TCPTP knockdown. We also examined expression of claudin-4, a prominent sealing claudin whose expression is decreased in IBD, and observed that claudin-4 expression was not affected by TCPTP knockdown with or without IFN-γ treatment (Fig. 3D).25 Overall, these data suggest that loss of TCPTP uncovers IFN-γ–stimulated expression of claudin-2, and this may contribute to increased permeability in TCPTP-deficient cells treated with IFN-γ and possibly to the increased permeability associated with in IBD. These data thus identify a novel role for PTPN2 (TCPTP) in protecting epithelial barrier function.

Discussion

We observed that TCPTP plays an important role in negatively regulating IFN-γ–induced signaling as assessed by inhibition of STAT signaling, in intestinal epithelial cells, and is thus in agreement with previous studies demonstrating that TCPTP exerts a similar function in immune cells.3,8,9 Moreover, PTPN2−/− mice die within three–five weeks from progressive systemic inflammation accompanied by elevated serum levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α.29 These data were supported by PTPN2 siRNA knockdown studies. Thus, it appears that TCPTP participates in a negative feedback mechanism activated by IFN-γ to limit cytokine signaling in IEC.

An observed functional consequence of elevated IFN signaling in TCPTP-deficient cells was a significant increase in epithelial permeability and a decrease TER. This was accompanied by a significant induction of claudin-2, which is not usually induced by IFN-γ in IEC.25,26 The claudin family of TJ proteins are key regulators of paracellular permeability, with many claudins functioning as sealing proteins.23,30 Interestingly, one such sealing claudin, claudin-4, was unaffected by IFN-γ in TCPTP-deficient cells, indicating a relatively specific effect on claudin-2, with the caveat that these were the only members of the claudin family investigated. Moreover, decreased expression of ZO-1 and occludin by IFN-γ was not further exacerbated by PTPN2 knockdown. Changes in expression or localization of claudins can result in increased epithelial permeability, which is believed to contribute substantially to the pathophysiology of CD.31 Although many claudins function to seal the TJ, claudin-2 is able to form a cation-selective membrane pore for substrates smaller than 4 A and may ° therefore directly account for the greater decrease in TER observed in IFN-γ–treated TCPTP-deficient T84 monolayers. Although the pore size of claudin-2 is not sufficiently large enough to permit passage of FITC-dextran (10 kD), and thus an increase in pore number is likely not responsible for the increase in IFN-γ–stimulated permeability to FITC-dextran observed in TCPTP-deficient cells, claudin-2 may indirectly contribute to increased macromolecule permeability.23 Claudin-2 is upregulated in intestinal crypt epithelium in CD, while in active CD there is an increase in the number of TJ strand breaks in colonic epithelium.24,25 Large macromolecules such as the 10 kD FITC-dextran used in our study can pass through these breaks, of ≥ 25 nm.24 In addition, increased claudin-2 expression correlates with the appearance of discontinuous TJ strands.32 Therefore, a possible explanation for the increased FITC-dextran flux observed in TCPTP-deficient cells is that this may be due to claudin-2 influenced changes in the structural composition of TJs, and a consequent increase in epithelial permeability.23–26,33 These findings suggest that TCPTP normally prevents a rise in claudin-2 expression in response to IFN-γ. Alternatively, additional signaling events involved in “leak”-type barrier events, such as internalization of TJ proteins in response to myosin light chain kinase or Rho-associated kinase activity, could explain the increase in permeability to FITC-dextran in TCPTP-deficient cells.34 This is currently under investigation in our laboratory.

It is possible that the IFN-γ–induced elevation of claudin-2 expression in TCPTP-deficient cells was mediated by STAT proteins. In support of this, we previously identified a putative STAT1/STAT3 binding sequence in the claudin-2 promoter region.21 Whether TCPTP restricts the influence of STAT proteins in claudin-2 expression, perhaps by reducing their phosphorylation, remains to be determined. This will be a particularly important issue to address as the involvement of STAT proteins in IFN-γ –induced barrier defects is controversial.16 Nevertheless, our findings indicate not only that TCPTP may protect epithelial barrier function during exposure to inflammatory cytokines, but also that loss of functional TCPTP may contribute to the pathogenesis of CD, a chronic inflammatory disease featuring elevated levels of IFN-γ. Given the association of mutations in the PTPN2 gene locus with CD, it is possible that mutations could lead to a loss of functional TCPTP in IBD.18,20,35 We have observed that (1) TCPTP expression is increased in biopsies from CD patients with active inflammation versus normal subjects; (2) IFN-γ increases TCPTP expression in vitro; and (3) loss of TCPTP exacerbates barrier defects. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that increased TCPTP is normally a protective response to inflammation and that mutations that compromise TCPTP expression or activity are likely detrimental. This interpretation is supported by one study that identified that heterozygous PTPN2-deficient mice exhibit a more severe inflammation than wild-type mice following exposure to dextran sulfate sodium.36 From a clinical perspective, identifying signaling events and pathophysiological outcomes that are amplified by reduced TCPTP expression, or loss-of-function PTPN2 mutations, could lead to the isolation of molecular targets that may be particularly effective therapeutic targets in IBD patients harboring PTPN2 SNPs. Therapeutic agents that “mimic” the effect of TCPTP by reducing the activity of these amplified signaling events could theoretically help to circumvent the biological consequences of PTPN2 SNPs.

In summary, these observations indicate a crucial role for PTPN2 (TCPTP) activity in the regulation of inflammatory responses and in the preservation of intestinal epithelial barrier properties in the setting of inflammation.

Acknowledgments

The studies in this paper were supported by a Senior Research Award from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America and by the UCSD Digestive Diseases Research Development Center, NIH grant #DK080506.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Cool DE, Tonks NK, Charbonneau H, et al. cDNA isolated from a human T-cell library encodes a member of the protein-tyrosine-phosphatase family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5257–5261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pao LI, Badour K, Siminovitch KA, Neel BG. Nonreceptor protein-tyrosine phosphatases in immune cell signaling. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:473–523. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ten Hoeve J, Ibarra-Sanchez MJ, Fu Y, et al. Identification of a nuclear Stat1 protein tyrosine phosphatase. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5662–5668. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.16.5662-5668.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tiganis T, Bennett AM, Ravichandran KS, Tonks NK. Epidermal growth factor receptor and the adaptor protein p52Shc are specific substrates of T-cell protein tyrosine phosphatase. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1622–1634. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ibarra-Sanchez MJ, Simoncic PD, Nestel FR, Duplay P, et al. The T-cell protein tyrosine phosphatase. Semin Immunol. 2000;12:379–386. doi: 10.1006/smim.2000.0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattila E, Pellinen T, Nevo J, et al. Negative regulation of EGFR signalling through integrin-alpha1beta1-mediated activation of protein tyrosine phosphatase TCPTP. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:78–85. doi: 10.1038/ncb1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galic S, Klingler-Hoffmann M, Fodero-Tavoletti MT, et al. Regulation of insulin receptor signaling by the protein tyrosine phosphatase TCPTP. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:2096–2108. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.6.2096-2108.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamamoto T, Sekine Y, Kashima K, et al. The nuclear isoform of protein-tyrosine phosphatase TC-PTP regulates interleukin-6-mediated signaling pathway through STAT3 dephosphorylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297:811–817. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02291-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu W, Mustelin T, David M. Arginine methylation of STAT1 regulates its dephosphorylation by T cell protein tyrosine phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35787–35790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200346200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scharl M, Hruz P, McCole DF. Protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor Type 2 regulates IFN-γ-induced cytokine signaling in THP-1 monocytes. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:2055–64. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaser A, Zeissig S, Blumberg RS. Inflammatory bowel disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:573–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Podolsky DK. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:417–429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuss IJ, Neurath M, Boirivant M, et al. Disparate CD4+ lamina propria (LP) lymphokine secretion profiles in inflammatory bowel disease. Crohn’s disease LP cells manifest increased secretion of IFN-gamma, whereas ulcerative colitis LP cells manifest increased secretion of IL-5. J Immunol. 1996;157:1261–1270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strober W, Zhang F, Kitani A, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines underlying the inflammation of Crohn’s disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:310–317. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328339d099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madara JL, Stafford J. Interferon-gamma directly affects barrier function of cultured intestinal epithelial monolayers. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:724–727. doi: 10.1172/JCI113938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beaurepaire C, Smyth D, McKay DM. Interferon-gamma regulation of intestinal epithelial permeability. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009;29:133–144. doi: 10.1089/jir.2008.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franke A, Balschun T, Karlsen TH, et al. Replication of signals from recent studies of Crohn’s disease identifies previously unknown disease loci for ulcerative colitis. Nat Genet. 2008;40:713–712. doi: 10.1038/ng.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parkes M, Barrett JC, Prescott NJ, et al. Sequence variants in the autophagy gene IRGM and multiple other replicating loci contribute to Crohn’s disease susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2007;39:830–832. doi: 10.1038/ng2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fisher SA, Tremelling M, Anderson CA, et al. Genetic determinants of ulcerative colitis include the ECM1 locus and five loci implicated in Crohn’s disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:710–712. doi: 10.1038/ng.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Welcome Trust Case Control Consortium. Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scharl M, Paul G, Weber A, et al. Protection of epithelial barrier function by the Crohn’s disease associated gene protein tyrosine phosphatase n2. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:2030–2040. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.07.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sasaki T, Hiwatashi N, Yamazaki H, et al. The role of interferon gamma in the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1992;27:29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Itallie CM, Holmes J, Bridges A, et al. The density of small tight junction pores varies among cell types and is increased by expression of claudin-2. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:298–305. doi: 10.1242/jcs.021485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeissig S, Burgel N, Gunzel D, et al. Changes in expression and distribution of claudin 2, 5 and 8 lead to discontinuous tight junctions and barrier dysfunction in active Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2007;56:61–72. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.094375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prasad S, Mingrino R, Kaukinen K, et al. Inflammatory processes have differential effects on claudins 2, 3 and 4 in colonic epithelial cells. Lab Invest. 2005;85:1139–1162. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watson CJ, Hoare CJ, Garrod DR, et al. Interferon-gamma selectively increases epithelial permeability to large molecules by activating different populations of paracellular pores. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5221–5230. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruewer M, Utech M, Ivanov AI, et al. Interferon-gamma induces internalization of epithelial tight junction proteins via a macropinocytosis-like process. FASEB J. 2005;19:923–33. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3260com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang F, Graham WV, Wang Y, et al. Interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha synergize to induce intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction by up-regulating myosin light chain kinase expression. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:409–419. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62264-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heinonen KM, Nestel FP, Newell EW, et al. T-cell protein tyrosine phosphatase deletion results in progressive systemic inflammatory disease. Blood. 2004;103:3457–3464. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amasheh S, Meiri N, Gitter AH, et al. Claudin-2 expression induces cation-selective channels in tight junctions of epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:4969–4976. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mankertz J, Schulzke JD. Altered permeability in inflammatory bowel disease: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007;23:379–383. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32816aa392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Furuse M, Sasaki H, Tsukita S. Manner of interaction of heterogeneous claudin species within and between tight junction strands. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:891–903. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.4.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kinugasa T, Sakaguchi T, Gu X, Reinecker HC. Claudins regulate the intestinal barrier in response to immune mediators. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:1001–1011. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70351-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Utech M, Ivanov AI, Samarin SN, et al. Mechanism of IFN-gamma-induced endocytosis of tight junction proteins: myosin II-dependent vacuolarization of the apical plasma membrane. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:5040–5052. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-03-0193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weersma RK, Stokkers PC, Cleynen I, et al. Confirmation of multiple Crohn’s disease susceptibility loci in a large Dutch-Belgian cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:630–638. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hassan SW, Doody KM, Hardy S, et al. Increased susceptibility to dextran sulfate sodium induced colitis in the T cell protein tyrosine phosphatase heterozygous mouse. PLoS One. 2010;5:1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]