Abstract

The outcome of bladder cancer after radical cystectomy is heterogeneous. We aim to evaluate the prognostic value of HALP (hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte and platelet) and explore novel prognostic indexes for patients with bladder cancer after radical cystectomy. In this retrospective study, 516 patients with bladder cancer after radical cystectomy were included. The median follow-up was 37 months (2 to 99 mo). Risk factors of decreased overall survival were older age, high TNM stage, high American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade and low HALP score. The predictive accuracy was better with HALP-based nomogram than TNM stage (C- index 0.76 ± 0.039 vs. 0.708 ± 0.041). By combining ASA grade and HALP, we created a novel index—HALPA score and found it an independent risk factor for decreased survival (HALPA score = 1, HR 1.624, 95% CI 1.139–2.314, P = 0.007; HALPA score = 2, HR 3.471, 95% CI: 1.861–6.472, P < 0.001).The present study identified the prognostic value of HALP and provided a novel index HALPA score for bladder cancer after radical cystectomy.

Introduction

Bladder cancer is the most common cancer in the urogenital system1. In 2017, there were 79030 new cases estimated in United States; the cancer ranks 6th in all cancers and 4th in males2. Radical cystectomy is the typical treatment for bladder cancer including muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) and high risk non-MIBC (NMIBC)1,3,4. Despite the advancements in surgical techniques and chemotherapy, the outcome of bladder cancer is poor, especially for patients with advanced and metastatic disease3,5.

The outcome of bladder cancer is heterogeneous, with 77.9% survival at 5 years for patients at all stages, 96.4% with in situ disease, 70.2% with invasive tumors and 3.0% and 5.4% with regional and distant-stage disease6. Therefore, it is crucial to stratify the risk of mortality and establish the optimal therapy and follow-up strategies.

Besides the traditional TNM system, numerous prognostic factors may predict outcome with bladder cancer. Haematological parameters including leukocyte count (neutrophil, lymphocyte and monocyte), platelet count and levels of hemoglobin, albumin, C-reactive protein (CRP), and fibrinogen are all easily assessed and reliable indicators of postoperative prognosis7–11. The combination of those indices have better predictive ability, for example, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and lymphocyte to monocyte ratio (LMR)12–14. Recently, a novel index, HALP (hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte and platelet levels) was developed and demonstrated as a significant prognostic factor for patients with colorectal cancer and gastric carcinoma15,16.

Here we evaluated the prognostic value of HALP and explored the development of a novel prognostic index for patients with bladder cancer after radical cystectomy.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 516 patients were enrolled in this study (436 84.5% males; median age 66 years) (Table 1). The median follow-up was 37 months (interquartile range [IQR] 20–56). 91 patients (17.6%) received adjuvant chemotherapy after radical cystectomy. At the end of follow-up, 164 patients (31.8%) had died from any cause and the 3- and 5-year estimated overall survival was 75.3% and 69%. Hypoalbuminemia was present in 8.3% patients (n = 43; 3.9% with NMIBC, 11.1% with MIBC, P = 0.009) and anemia was present in 27.9% (n = 144; 12.4% with NMIBC, 37.5% with MIBC, P < 0.001). Other clinicopathological characteristics are in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics for 516 bladder cancer patients.

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 66 (57–73) |

| Gender | |

| female | 80 (15.5%) |

| male | 436 (84.5%) |

| Smoking history | |

| no | 355 (68.8%) |

| yes | 161 (31.2%) |

| Alcohol-drinking history | |

| no | 449 (87.0%) |

| yes | 67 (13%) |

| Hypertension | |

| no | 367 (71.1%) |

| yes | 149 (28.9%) |

| Histology subtype | |

| transitional cell carcinoma | 488 (94.6%) |

| non-transitional cell carcinoma | 28 (5.4%) |

| Grade | |

| 2 | 126 (24.4%) |

| 3 | 385 (75.6%) |

| T-stage | |

| NMIBC | 162 (31.4%) |

| MIBC | 354 (68.6%) |

| N-stage | |

| negative | 81 (15.7%) |

| positive | 435 (84.3%) |

| M-stage | |

| negative | 511 (99.03%) |

| positive | 5 (0.97%) |

| Adjunctive chemotherapy | |

| yes | 91 (17.6%) |

| no | 425 (82.4%) |

| ASA grade | |

| 1&2 | 436 (84.5%) |

| 3&4 | 80 (15.5%) |

| Anemia | |

| present | 144 (27.9%) |

| absent | 342 (72.1%) |

| Hypoalbuminemia | |

| present | 43 (8.3%) |

| absent | 442 (85.7%) |

| PLR, median (IQR) | 133.8 (98.22–180.23) |

| HALP, median (IQR) | 41.2 (27.78–58.71) |

IQR, interquartile range; MIBC, muscle-invasive bladder cancer; NMIBC, non-muscle invasive bladder cancer; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; PLR: platelet to lymphocyte ratio.

Association between clinicopathological features and HALP

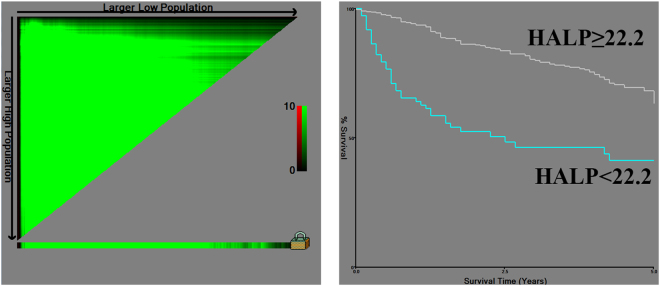

We determined the cut-off values of HALP as 22.2 and PLR as 214.8. Patients were divided into 2 groups according to the cut-offs (Fig. 1). Older age, female sex, high T stage, high ASA grade and anemia were associated with low HALP score (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Cut off value for HALP by X-tile software.

Table 2.

Association between clinicopathological characteristics and HALP.

| Cohort characteristics | HALP value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | P value | |

| Age | 0.019 | ||

| <65 | 24(32.9) | 196(47.7) | |

| ≥65 | 49(67.1) | 215(52.3) | |

| Gender | 0.013 | ||

| female | 18(24.7) | 55(13.4) | |

| male | 55(75.3) | 356(86.6) | |

| Smoking history | 0.204 | ||

| no | 55(75.3) | 279(67.9) | |

| yes | 18(24.7) | 132(32.1) | |

| Alcohol-drinking history | 0.646 | ||

| no | 65(89.0) | 358(87.1) | |

| yes | 8(11.0) | 53(12.9) | |

| Hypertension | 0.890 | ||

| no | 52(71.2) | 296(72.0) | |

| yes | 21(28.8) | 115(28.0) | |

| Histology type | 0.553 | ||

| transitional cell carcinoma | 70(95.9) | 387(94.2) | |

| non-transitional cell carcinoma | 3(4.1) | 24(5.8) | |

| Grade | 0.178 | ||

| 2 | 13(17.8) | 102(24.8) | |

| 3 | 60(82.2) | 304(74.0) | |

| T-stage | <0.001 | ||

| NMIBC | 7(9.6) | 146(35.5) | |

| MIBC | 66(90.4) | 265(64.5) | |

| N-stage | 0.725 | ||

| negative | 61(83.6) | 350(85.2) | |

| positive | 12(16.4) | 61(14.8) | |

| M-stage | 0.026 | ||

| negative | 70(95.9) | 409(99.5) | |

| positive | 3(4.1) | 2(0.5) | |

| Adjunctive chemotherapy | 0.170 | ||

| yes | 16(21.9) | 68(16.5) | |

| no | 57(78.1) | 343(83.5) | |

| ASA grade | 0.010 | ||

| 1&2 | 54(74.0) | 353(85.9) | |

| 3&4 | 19(26.0) | 58(14.1) | |

| Anemia | <0.001 | ||

| absent | 13(17.8) | 327(79.6) | |

| present | 60(82.2) | 84(20.4) | |

| Hypoalbuminemia | <0.001 | ||

| absent | 47(64.4) | 394(95.9) | |

| present | 26(35.6) | 17(4.1) | |

| PLR | <0.001 | ||

| low | 23(31.5) | 397(96.6) | |

| high | 50(68.5) | 14(3.4) | |

Data are shown as n (%).

MIBC, muscle-invasive bladder cancer; NMIBC, non-muscle invasive bladder cancer; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; PLR: platelet to lymphocyte ratio.

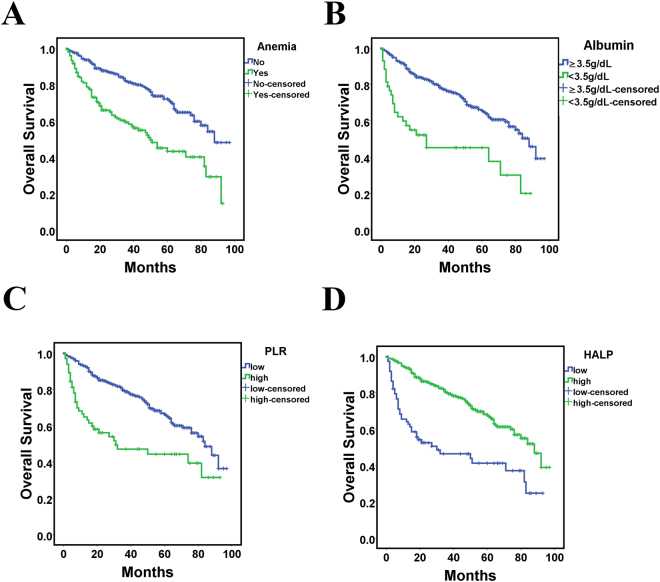

Prognostic value of HALP for outcomes

On univariate analysis, hypoalbuminemia, anemia, high PLR, and low HALP were all associated with worse overall survial (Fig. 2).Other factors included older age (>65 years), high TNM grade and high ASA grade (all P < 0.05) (Table 3). These variables were included in a multivariable analysis. Independent factors associated with decreased overall survival were older age, high TNM stage, high ASA grade and low HALP score (HR = 1.986, 95% CI: 1.386–2.886, P < 0.001) for bladder cancer patients after radical cystectomy (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival in patients with bladder cancer according to anemia level, (A) hypoalbuminemia level, (B) platelet to lymphocyte rate (PLR), (C) and HALP (D).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariable analysis of factors associated with overall survival in bladder cancer patients who underwent radical cystectomy.

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Gender (female vs. male) | 0.794(0.528–1.193) | 0.264 | ||

| Age (>65 vs. ≤65) | 2.220(1.592–3.098) | 0.001 | 1.923 (1.336–2.768) | <0.001 |

| Smoking history | 1.014(0.725–1.417) | 0.937 | ||

| Alcohol-drinking history | 0.922(0.565–1.504) | 0.743 | ||

| Hypertension | 1.130(0.803–1.591) | 0.480 | ||

| Histology type (TCC vs. no-TCC) | 0.706(0.331)1.506 | 0.363 | ||

| G (3 vs. 2) | 2.118(1.373–3.267) | <0.001 | ||

| T (MIBC vs. NMIBC) | 4.301(2.665–6.942) | <0.001 | 2.769 (1.679–4.565) | <0.001 |

| N (positive vs. negative) | 2.448(1.716–3.491) | <0.001 | 2.114 (1.434–3.116) | <0.001 |

| M (positive vs. negative) | 10.509(3.842–28.746) | <0.001 | 4.153 (1.454–11.863) | 0.008 |

| Adjunctive chemotherapy | 2.056(1.437–2.941) | <0.001 | ||

| ASA (3&4 vs. 1&2) | 2.068(1.442–2.964) | <0.001 | 1.540(1.038–2.284 | 0.032 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 2.919(1.900–4.484) | <0.001 | ||

| Anemia | 2.433(1.775–3.335) | <0.001 | ||

| PLR | 1.963(1.421–2.712) | <0.001 | ||

| HALP | 2.820(1.976–4.025) | <0.001 | 1.986 (1.386–2.886) | <0.001 |

TCC, transitional cell carcinoma; MIBC, muscle-invasive bladder cancer; NMIBC, non-muscle invasive bladder cancer; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; PLR: platelet-lymphocyte ratio; HR, hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval.

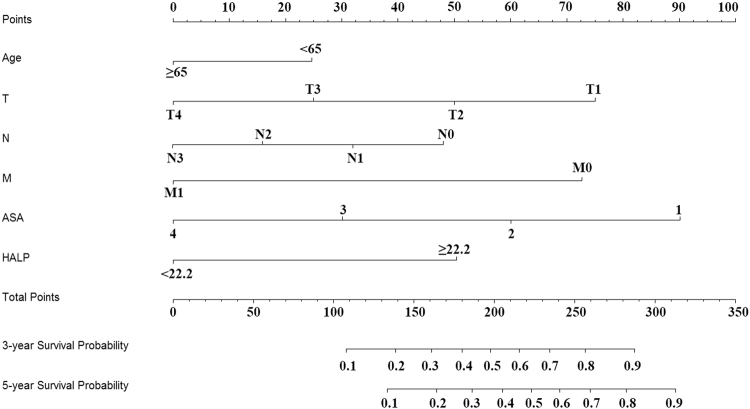

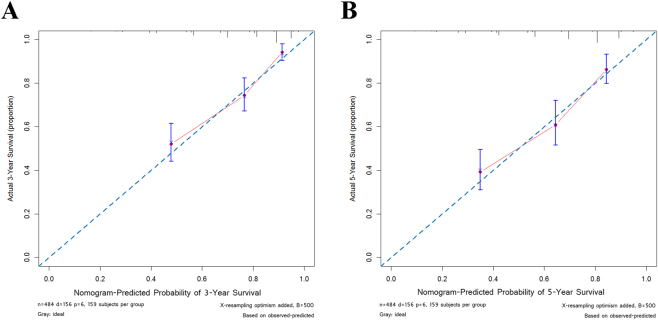

HALP-based risk model for bladder cancer patients after radical cystectomy

To further assess the prognostic ability of HALP and other variables, we used nomogram including the independent risk factors in the multivariable regression analysis (Fig. 3). Predicted 3- and 5- year survival was similar to the actual rates (Fig. 4). The predictive accuracy of C-indices was 0.76 ± 0.039 for the HALP-based nomogram as compared with 0.708 ± 0.041 for the TNM stage-based nomogram.

Figure 3.

Nomogram for 3-year and 5-year survival.

Figure 4.

Calibration curves for 3-year (A) and 5-year (B) survival.

Prognostic value of novel index HALPA

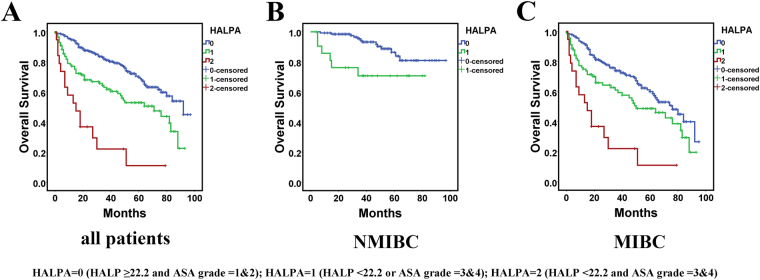

In the multivariate analysis and nomograms, ASA was a significant factor in addition to TNM stage and HALP score. Therefore, we combined ASA grade and HALP score and created a new index, HALPA score. The score of HALPA was determined as follows: HALPA = 0 (HALP ≥ 22.2 and ASA grade = 1&2); HALPA = 1 (HALP < 22.2 or ASA grade = 3&4); and HALPA = 2 (HALP < 22.2 and ASA grade = 3&4). Therefore, a higher HALPA score indicated higher risk of decreased survival. Univariate and multivariable analyses were performed again with HALPA score. On log-rank test, HALPA score was a significant indicator of poor survival for all patients and NMIBC or MIBC patients (Fig. 5). Notably, no NMIBC patient had a HALPA score of 2, which also showed the ability of HALPA score to distinguish the tumor stage of bladder cancer patients. On multivariable analysis, high HALPA score remained an independent risk factor of decreased survival along with older age and TNM stage (HALPA score = 1, HR = 1.624, 95% CI:1.139–2.314, P = 0.007; HALPA score = 2, HR = 3.471, 95% CI: 1.861–6.472, P < 0.001) (Table 4).

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier curves for all patients (A), NMIBC patients (B), MIBC patients (C) by HALPA score.

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariable analysis of factors associated with overall survival in bladder cancer patients who underwent radical cystectomy including HALPA.

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Gender (female vs. male) | 0.794(0.528–1.193) | 0.264 | ||

| Age (>65 vs. ≤65) | 2.220(1.592–3.098) | 0.001 | 1.849 (1.294–2.641) | 0.001 |

| Smoking history | 1.014(0.725–1.417) | 0.937 | ||

| Alcohol-drinking history | 0.922(0.565–1.504) | 0.743 | ||

| Hypertension | 1.130(0.803–1.591) | 0.480 | ||

| Histology type (TCC vs. no-TCC) | 0.706(0.331)1.506 | 0.363 | ||

| G (3 vs. 2) | 2.118(1.373–3.267) | <0.001 | ||

| T (MIBC vs. NMIBC) | 4.301(2.665–6.942) | <0.001 | 2.831 (1.720–4.658) | <0.001 |

| N (positive vs. negative) | 2.448(1.716–3.491) | <0.001 | 2.135 (1.448–3.146) | <0.001 |

| M (positive vs. negative) | 10.509(3.842–28.746) | <0.001 | 3.807 (1.278–11.336) | 0.016 |

| Adjunctive chemotherapy | 2.056(1.437–2.941) | <0.001 | ||

| ASA (3&4 vs. 1&2) | 2.068(1.442–2.964) | <0.001 | ||

| Hypoalbuminemia | 2.919(1.900–4.484) | <0.001 | ||

| Anemia | 2.433(1.775–3.335) | <0.001 | ||

| PLR | 1.963(1.421–2.712) | <0.001 | ||

| HALP | 2.820(1.976–4.025) | <0.001 | ||

| HALPA | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 2.084(1.477–2.941) | <0.001 | 1.624 (1.139–2.314) | 0.007 |

| 2 | 6.300(3.628–10.940) | <0.001 | 3.471 (1.861–6.472) | <0.001 |

TCC, transitional cell carcinoma; MIBC, muscle-invasive bladder cancer; NMIBC, non-muscle invasive bladder cancer; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; PLR: platelet to lymphocyte ratio; HR, hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Discussion

Besides traditional TNM stage and histologic classification, several haematological-based indices such as hemoglobin, albumin, and CRP levels, NLR, PLR and LMR were found associated with outcome with bladder cancer7,10,12–14,17. In the present study, we evaluated the prognostic value of a recently reported index, HALP, which combined hemoglobin and albumin levels and lymphocyte and platelet count, and found it as a good prognostic index for overall survival of patients with bladder cancer after radical cystectomy. By combining ASA grade and HALP score, we also created HALPA score and found it as an independent risk factor of decreased overall survival.

Cancer-related anemia is a common complication for cancer patients because of chromic blood loss, iron deficiency, vitamin deficiency and inflammation imbalance in terms of increased expression of interleukin and tumor necrosis factor. Jung et al.7 reported that 81 of 200 (40.5%) bladder cancer patients undergoing radical cystectomy had preoperative anemia and that anemia was significantly associated with disease recurrence and cancer-specific mortality and for MIBC patients, 53.3% patients were anemic, and older age, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, female sex, and low BMI were independent predictors of preoperative anemia. In this study, anemia was present in 27.9% patients (12.4% NMIBC, 37.5% MIBC, P < 0.001), which was lower than in previous reports. This difference may be due to use of different population. On univariate analysis, anemia was significantly associated with decreased overall survival (P < 0.001).

Hypoalbuminemia is another nutrition deficiency index. Lambert et al.11 reported that for bladder cancer patients after radical cystectomy, 16.5% had low-albumin level (<3.5 g/dL), and low albumin level was significantly associated with increased risk of mortality (HR = 1.76, P = 0.04). Another study found that 197 of 1471 (13.4%) bladder cancer patients had a low serum albumin level, and low albumin level was independently associated with reduced recurrence-free survival (HR 1.68, P = 0.006) and overall survival (HR 1.93, P < 0.001). Moreover, the authors also found low serum albumin associated with higher 90-day complication rate (42% vs. 34%, P = 0.03) and 90-day mortality (7.6% vs. 3.3%, P = 0.008)17. These findings document the adverse effects of nutritional deficiency on survival of bladder cancer after radical cystectomy and demonstrate the importance of nutritional interventions.

Tumor-promoting inflammation is one of the hallmarks of cancer18. For example, neutrophils and platelets could promote carcinogenesis, angiogenesis, invasion, or metastasis by secreting proinflammatory cytokines19,20. However, lymphocytes could inhibit tumor proliferation and migration via cytotoxicity21. Therefore, high PLR level, which reflects high platelet count and low lymphocyte count was found associated with overall survival in patients with bladder cancer undergoing radical cystectomy14.

The association of ASA score and long-term survival outcomes of bladder cancer patients after radical cystectomy is rarely reported. One study found that 740 of 1964 (64.8%) patients who underwent radical cystectomy had a high ASA score (3 or 4), and a high ASA grade remained independently associated with decreased overall survival (HR 1.45, 95% CI: 1.13–1.86, P = 0.003)17. In this study, a high ASA score was also significant independent risk factor for decreased overall survival and the nomogram including ASA grade and HALP score had better predictive accuracy than TNM stage. By combining ASA grade and HALP score, we created a novel index, HALPA score, and found it to have a specific distribution in patients at different stages and a significant independent risk factor with higher risk ratio than HALP score or ASA alone.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the retrospective nature has inherent limitations. Second, this was a single-center study and could not avoid the bias of population choice. Third, the use of cutoffs for continuous variables might weaken the reliability of the risk system. Finally, ASA is a subjective measure and this may limit the generalizability and overall utility. The prognostic ability and accuracy of HALP and HALPA score for bladder cancer patients warrants prospective multi-center validation.

Conclusions

HALP may be a good prognostic index for overall survival for patients with bladder cancer after radical cystectomy. Combining ASA grade and HALP score in the HALPA score could distinguish tumor stage and was an independent risk factor for decreased overall survival. These indices could be used for risk stratification of individual bladder cancer patients and for choosing therapeutic strategy.

Methods

Data collection

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Peking University First Hospital. Between 2006 and 2012, 516 bladder cancer consecutive patients underwent radical cystectomy in the Department of Urology, Peking University First Hospital. This research was carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines and informed consent was obtained from all patients. Hematological features including hemoglobin and albumin levels and blood cell counts were preoperative collected within 3 days before surgery. Other clinicopathological data included gender, age, smoking history, hypertension history, histology subtype, grade, TNM stage and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade.

The follow-up of bladder cancer patients after radical cystectomy was according to the routine procedure in our institution. The period from the operation date until the time of death resulting from any cause was calculated as overall survival time. HALP was calculated as hemoglobin (g/L) × albumin (g/L) levels × lymphocyte count (/L)/platelet count (/L) and PLR as platelet count/lymphocyte count. Anemia was defined according to preoperative hemoglobin level (males <120 g/L and females <110 g/L) and hypoalbuminemia according to preoperative albumin level (<35 g/L).

Statistical analysis

X-tile software v3.6.1 (Yale University) was used to determine the cut-off values of PLR and HALP22. SPSS v22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. Chi-square test was used to evaluate the association between clinicopathological data and HALP. Overall survival was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test was used for univariate analysis. Variables with significant differences on univariate analysis (P < 0.05) were then included in the multivariable survival analyses with a Cox proportional-hazards regression model, estimating hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Nomogram and production of calibration curves involved use of R v3.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) with the rms package (Regression Modeling Strategies). A two-tail P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no.: 81372746, 81772703 and 81672546) and Natural Science Foundation of Beijing (Grant no.: 7172219).

Author Contributions

D.P. and C.Z. wrote the manuscript. D.P., Y.G. and C.Z. analyzed the data. D.P., Y.G., H.H. and B.G. collected data and edited the tables. D.P., X.L. and L.Z. designed the study. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Ding Peng and Cui-jian Zhang contributed equally to this work.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yan-qing Gong, Email: yqgong@bjmu.edu.cn.

Xue-song Li, Email: pineneedle@sina.com.

Li-qun Zhou, Email: zhoulqmail@sina.com.

References

- 1.Clark PE, et al. Bladder cancer. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network: JNCCN. 2013;11:446–475. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babjuk M, et al. EAU Guidelines on Non–Muscle-invasive Urothelial Carcinoma of theBladder: Update 2016. European urology. 2017;71:447–461. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alfred Witjes J, et al. Updated 2016 EAU Guidelines on Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer. European urology. 2017;71:462–475. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang, S. S. et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: AUA/SUO Guideline. The Journal of urology, 10.1016/j.juro.2016.06.049 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.DeSantis CE, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2014;64:252–271. doi: 10.3322/caac.21235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jo JK, et al. The impact of preoperative anemia on oncologic outcome in patients undergoing radical cystectomy for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. International urology and nephrology. 2016;48:489–494. doi: 10.1007/s11255-016-1219-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moschini M, et al. Impact of preoperative thrombocytosis on pathological outcomes and survival in patients treated with radical cystectomy for bladder carcinoma. Anticancer research. 2014;34:3225–3230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klinga G, Sherif A. A retrospective evaluation of preoperative anemia in patients undergoing radical cystectomy for muscle-invasive urothelial urinary bladder cancer, with or without neoadjuvant chemotherapy. SpringerPlus. 2016;5:1167. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2865-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eggers H, et al. Serum C-reactive protein: a prognostic factor in metastatic urothelial cancer of the bladder. Medical oncology. 2013;30:705. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0705-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lambert JW, et al. Using preoperative albumin levels as a surrogate marker for outcomes after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. Urology. 2013;81:587–592. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Temraz S, et al. Preoperative lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio predicts clinical outcome in patients undergoing radical cystectomy for transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: a retrospective analysis. BMC urology. 2014;14:76. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-14-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma C, et al. Preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and fibrinogen level in patients distinguish between muscle-invasive bladder cancer and non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. OncoTargets and therapy. 2016;9:4917–4922. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S107445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang GM, et al. Preoperative lymphocyte-monocyte and platelet-lymphocyte ratios as predictors of overall survival in patients with bladder cancer undergoing radical cystectomy. Tumour biology: the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2015;36:8537–8543. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3613-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang, H. et al. Preoperative combined hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte and platelet levels predict survival in patients with locally advanced colorectal cancer. Oncotarget, 10.18632/oncotarget.12271 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Chen XL, et al. Prognostic significance of the combination of preoperative hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte and platelet in patients with gastric carcinoma: a retrospective cohort study. Oncotarget. 2015;6:41370–41382. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Djaladat H, et al. The association of preoperative serum albumin level and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score on early complications and survival of patients undergoing radical cystectomy for urothelial bladder cancer. BJU international. 2014;113:887–893. doi: 10.1111/bju.12240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masson-Lecomte A, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers and bladder cancer prognosis: a systematic review. European urology. 2014;66:1078–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Fridman WH, Pages F, Galon J. Natural immunity to cancer in humans. Current opinion in immunology. 2010;22:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Camp RL, Dolled-Filhart M, Rimm DL. X-tile: a new bio-informatics tool for biomarker assessment and outcome-based cut-point optimization. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2004;10:7252–7259. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]