1. Introduction

Much work in the late 1990s and early 2000s highlighted the emerging role of the neighbourhood social environment in public health research. These works described the influence of neighbourhood social processes on individual health and well-being outcomes and highlighted the need for better understandings of how we conceptualise and measure the social environment (i.e., Earls and Carlson, 2001, Morrow, 1999, Morrow, 2001; Yen & Syme, 1999). Overall, the neighbourhood social environment is defined as the social dimensions of the neighbourhoods in which we live (Yen & Syme, 1999). However, the complexity of these social dimensions leads to ambiguity of definitions that creates difficulties in measurement (Earls & Carlson, 2001).

In a seminal piece of work, Sampson, Morenoff, and Gannon-Rowley (2002) synthesised the evidence on the role of the social environment on health behaviours and outcomes, with a particular focus on adolescents. The authors provided a summary of neighbourhood social mechanisms, extending beyond more traditional measures of neighbourhood deprivation, and drew several conclusions regarding future research directions. They concluded that, relating to issues of consistency in how measures were operationalised and theoretically situated, questions remained as to whether the neighbourhood social environment is best measured by a few higher-level constructs or several sub-domains. Additionally, while community-based surveys were found to yield valid measurements of the neighbourhood social environment, methods for evaluating ecological (aggregate) measures, termed ‘ecometrics’, were not widespread, though needed in a multilevel framework (Earls and Carlson, 2001, Sampson et al., 2002). More than a decade later much inconsistency and debate still exists regarding how best to conceptualise and measure the neighbourhood social environment, particularly when studying adolescents.

Among adolescents, choice and freedom to engage in behaviours is influenced, at least in part, by the neighbourhood social environments to which they are exposed (Morrow, 1999, Morrow, 2001). Adolescents are active agents within their neighbourhoods; however, their agencies within the wider social and physical environments are widely overlooked in studies that utilize adult-centred measures (Morrow, 1999, Paiva et al., 2014). This signifies a methodological weakness as adult perceptions of the neighbourhood cannot fully represent the perceptions that young people have of their environment (Schaefer-McDaniel, 2004). Some evidence of this is provided by studies that examine both perceptions of adolescents and adults and find differing results on outcomes (Bryden et al., 2013, Byrnes et al., 2007, Byrnes et al., 2013, De Haan et al., 2009). Therefore, it is reasoned that adolescent-centred approaches are more theoretically valid than adult measures of the adolescent environment, as young people may have different perceptions of their neighbourhood than adults, are generally exposed to fewer neighbourhoods due to a relative lack of mobility, and may have access to different areas within their neighbourhood.

The use of good quality instruments is necessary when examining associations between adolescents’ neighbourhood social environments and their health and well-being. Different approaches are taken to conceptualisation, operationalisation and measurement which might explain inconsistent research findings (Sampson et al., 2002). Reviews examining the social environment and similar health outcomes (i.e. alcohol use) have found conflicting results between studies (Bryden et al., 2013, Jackson et al., 2014) which may be due to considerable heterogeneity in how the neighbourhood social environment is measured.

The neighbourhood social environment is often measured at different levels. The individual level represents the survey respondent's perception of their neighbourhood, while the neighbourhood level represents the combined characteristics of all survey respondents in that area. Ecological neighbourhood level measures are relevant to research of neighbourhoods and health so that the researcher can address health outcomes that vary across places, independent of the resident's individual level characteristics (Hawe & Shiell, 2000). Moreover, neighbourhood level exposures may be mediated by the corresponding individual level measure. As social processes occur at a neighbourhood level, measurement of ecological constructs represents a collective phenomenon; consequently, neighbourhood level measures are essential to better understand what makes some places more or less healthy and inform place-based interventions (Sampson et al., 2002).

The aim of this systematic review was to identify measures currently available relating to the neighbourhood social environment in research with adolescents, and make recommendations about the future use, development and application of such measures. Specifically, as a growing number of studies are utilising survey-based measures of the social environment when examining health outcomes, there is a need for future research to assess validity and reliability of existing measures both at the individual (perceived) and neighbourhood (aggregate) level. This systematic review will contribute to the literature by presenting a critical review and evaluation of how the neighbourhood social environment has been measured in studies of adolescents. It is appropriate to critically examine such studies, as the social environment of adolescents is an area of increasing research interest, yet little is known about the reliability and validity of instruments used to assess this or how these concepts are operationalised and theorised. It is clear that questions about the reliability and validity of measures affect the evaluation of study results; therefore this study will provide a framework for the use of such measures in studies of the adolescent social environment.

The specific objectives of the systematic review are as follows:

-

1)

To assess the methodological quality of studies reporting on measures of the neighbourhood social environment.

-

2)

To critically review and compare how these measures are conceptualised and operationalised.

-

3)

To make recommendations for future use of neighbourhood social environmental measures in studies of adolescents.

2. Methods

2.1. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they: 1) reported on quantitative studies published in a peer-reviewed journal, 2) reported the use, original development, or refinement of tools that have been developed to measure the neighbourhood social environment, as perceived by adolescents. In order to ensure that the neighbourhood social environment remained the focus of the study, only geographically bound measures about perceptions of the local areas in which adolescents live and spend their time (i.e., the question specifically referred to ‘local area’, ‘neighbourhood’, ‘community’, etc.), were included. The population was limited to the World Health Organisation definition of adolescence (10–19 years of age or if age was not stated, the corresponding school grades of 5–12, or equivalent i.e., P7 – S6 in Scotland) (World Health Organization, 2017).

The following studies were considered beyond the scope of this review and were therefore excluded: 1) studies examining macro-environmental factors (e.g. experiences of terrorist attacks or living in a war zone), 2) studies examining social conditions of the school or family, 3) general quality of life indicators, 4) measures that solely related to the physical or built environment, 5) studies where neighbourhood socio-economic status was the only predictor of the social environment, and 6) studies which focused on measures of community violence and/or substance misuse.

In addition, studies which utilised measures that only consisted of one item, or did not provide full details of items used in the research, or provide a citation of where these items can be found, were not included due to dearth of detail preventing a meaningful assessment of measurement operationalisation.

Studies were limited to those written in English and publications listed on databases from 2001 (the cut-off year of Sampson et al.’s 2002 review, thus providing an update to some components of that review) to Aug 18th, 2014. If a study contained multiple measures, only measures that met the above criteria were discussed.

2.2. Search strategy

A detailed systematic review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (registration ID: CRD42014014721) (to access see Martin, Gavine, Currie, Inchley, and Miller (2014)). Studies were identified by a search of six databases on August 18th, 2014: Medline (via EBSCO), Scopus, Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) which includes the Institute of Educational Sciences (ERIC) database, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (via EBSCO), Web of Science, and PsycInfo (via EBSCO). The search architecture (see Appendix A) was developed drawing on past reviews of the neighbourhood social environment that reported search terms (Bryden et al., 2013, Jackson et al., 2014, McPherson et al., 2013, Vyncke et al., 2013), using an initial scoping of the literature, and through co-author discussion.

2.3. Study selection process

The records identified from the database searches were imported into Endnote and de-duplicated. Due to time constraints, only one author screened all titles and abstracts and a second author independently screened a sample of 15% of the abstracts in order to explore whether the application of the inclusion/exclusion criteria to the identified records was appropriate. Inter-rater agreement was quantified by examining simple percentages, as Kappa scores are rarely more informative than using this approach (Gough, Oliver, & Thomas, 2012). Disagreements were resolved by discussion with the goal of consensus. Any studies that potentially met the inclusion criteria were retrieved and full text was screened by the first author.

2.4. Quality assessment

Evaluations of the methodological quality of psychometric measures were assessed using the 4-Point COnsensus-based Standards from the selection of health status Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) checklist (Mokkink et al., 2010, Terwee et al., 2012). This module-based standardised instrument was designed to evaluate the methodological quality of studies presenting measures from health status questionnaires, in terms of their reliability and validity reporting (Paalman, Terwee, Jansma, & Jansen, 2013). Similar to past studies who used the COSMIN checklist (Ammann-Reiffer, Bastiaenen, de Bie, & van Hedel, 2014; Reimers, Mess, Bucksch, Jekauc, & Woll, 2013) we used a subset of the modules appropriate to the included studies. Reliability and validity were assessed using questions from “Box A-Internal Consistency” and “Box E -Structural Validity” (duplicate or overlapping questions were only assessed once- see Table 1). Where necessary it was also noted when aggregate (neighbourhood level) measures were also derived and, in the absence of a quality appraisal tool for ecological (aggregate) measures, any attempts made to describe their reliability or validity.

Table 1.

Modified COSMIN checklist for methodological quality assessment.

| Excellent | Good | Fair | Poor | NA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Was the percentage of missing items given? | Percentage of missing items described | Percentage of missing items NOT described | – | – | – |

| 2 | Was there a description of how missing items were handled? | Described how missing items were handled | Not described but can deduce how missing items were handled | Not clear how missing items were handled | – | – |

| 3 | For Classical Test Theory (CTT) was Cronbach's alpha calculated?/ For IRT Was a goodness of fit statistic at the global level calculated? |

Cronbach's alpha or KR-20 calculated/ Goodness of fit statistic at a global level calculated | – | Only item-total correlations calculated/- | Cronbach's alpha or KR-20 NOT calculated/ Goodness of fit statistic at a global level NOT calculated | – |

| 4 | Was the sample size included in the internal consistency adequate? | Adequate sample size (≥100) | Good sample size (50–99) | Moderate sample size (30–49) | Small sample size (<30) | If 3 is poor |

| 5 | For CTT: Was exploratory or confirmatory factor analysis performed?/ For IRT: Were IRT tests for determining (uni-)dimensionality of the items performed? | Exploratory or confirmatory factor analysis performed and type of factor analysis appropriate in view of existing information/IRT test for determining uni(dimensionality performed | Exploratory factor analysis performed while confirmatory would have been more appropriate/ - |

– | No Exploratory or confirmatory factor analysis performed/ IRT test for determining (uni)dimensionality NOT performed | – |

| 6 | Was an internal consistency statistic calculated for each (unidimensional) (sub) scale separately? | Internal consistency statistic calculated for each subscale separately | – | – | Internal consistency statistic NOT calculated for each subscale separately | – |

| 7 | Was the sample size included in the unidimensionality analysis adequate? | 7*#items and ≥ 100 | 5*#items and ≥ 100 OR 6–7*#items but <100 | 5*#items but <100 | <5*#items | If 5 is poor |

| 8 | Were there any important flaws in the design or methods of the study? | No other important methodological flaws in the design or execution of the study | – | Other minor methodological flaws in the design or execution of the study | Other important methodological flaws the design or execution of the study | – |

2.5. Data extraction

Studies were organised by measurement concept (i.e. social control, neighbourhood support, etc.; see Table 2). Where a single study reported multiple measures, it was listed multiple times. Where data were duplicated in multiple studies for the same population, a note was made and data extraction only occurred once. Data were extracted on the study characteristics of: geographic region, urban/rurality, participants’ age, sample size, and the number and size of aggregate neighbourhoods (if applicable).

Table 2.

Data extraction from studies included in narrative synthesis.

| Author(s) (year) | Author(s) measure description | Sample size | Participants age (or grade) when measure was taken | Region | Urban /rurality | Psychometric method | Number of items | Measure reliability (Cronbach's alpha) | Aggregate measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informal social control | |||||||||

| Kerrigan et al. (2006) | Neighbourhood collective monitoring | 343 | 14–19 | Baltimore | Urban | EFA | 4 | 0.80 | No |

| Law and Barber (2007) | Collective social control | 676 | Grades 5 and 8 | Ogden, Utah | ? | EFA | 3 | 0.69 | No |

| Neumann et al. (2010) & Barker et al. (2011) | Informal social control | 4597 | 12 | Edinburgh | Urban | CFA | 6 | 0.58 | No |

| Oliva et al. (2012) | Social control | 2400 | 12–17 | Western Andalusia, Spain | Mixed | EFA and CFA | 4 | 0.85 | No |

| Attachment/Sense of belonging/connectedness | |||||||||

| Albanesi, Cicognani, and Zani (2007) | Sense of belonging | 566 | 14–19 | Mantova and San Giovanni in Northern Italy | Mixed | CFA | 9 | 0.85 | No |

| Chiessi et al. (2010)a | Sense of belonging | 661 | 15–18 | Town in Northern Italy | Midsized town | EFA and CFA | 4 | 0.82 | No |

| Karcher and Sass (2010) | Sense of community connectedness | 3633 | Grades 6–8 | Midwest US city | Urban | CFA | 6 | 0.85 | No |

| Mayberry et al. (2009) | Sense of community | 14,548 | Grades 9–12 | Dane County Midwest US county | ? | EFA and CFA | 6 | 0.77 | Yes; aggregated to school level; no reliability reported |

| Oliva et al. (2012) | Attachment to neighbourhood | 2400 | 12–17 | Western Andalusia, Spain | Mixed | EFA and CFA | 4 | 0.91 | No |

| Perez-Smith et al. (2001) | Neighbourhood affiliation (attachment) | 167 | 14–19 | Baltimore, US | Urban | EFA | 9 | 0.92 | No |

| Van Gundy et al. (2011) | Community attachment | 1310 | Grades 7–11 | Coös County and Southern New Hampshire, US | Mixed | EFA | 4 | 0.72 | No |

| Zani et al. (2001) | Membership | 823 | 14–19 | North Central Italy | Mixed | EFA | 4 | 0.64 | No |

| Opportunities for prosocial involvement | |||||||||

| Albanesi et al. (2007) | Satisfaction of needs and opportunities for involvement | 566 | 14–19 | Mantova and San Giovanni in Northern Italy | Mixed | CFA | 7 | 0.82 | No |

| Opportunities for influence | 566 | 14–19 | Mantova and San Giovanni in Northern Italy | Mixed | CFA | 4 | 0.71 | No | |

| Baheiraei et al. (2014)d | Opportunities for prosocial involvement | 753 | 15–18 | Tehran, Iran | Urban | CFA | 3 | 0.79 | No |

| Chiessi et al. (2010)a | Satisfaction of needs and opportunities for involvement | 661 | 15–18 | Town in Northern Italy | Midsized town | EFA and CFA | 4 | 0.76 | No |

| Opportunities for influence | 661 | 15–18 | Town in Northern Italy | Midsized town | EFA and CFA | 4 | 0.74 | No | |

| Zani et al. (2001) | Opportunities for participation and fulfilment of needs | 823 | 14–19 | North Central Italy | Mixed | EFA | 6 | 0.65 | No |

| Support | |||||||||

| Albanesi et al. (2007) | Support and emotional connection in the community | 566 | 14–19 | Mantova and San Giovanni in Northern Italy | Mixed | CFA | 6 | 0.81 | No |

| Support and emotional connections with peers | 566 | 14–19 | Mantova and San Giovanni in Northern Italy | Mixed | CFA | 10 | 0.90 | No | |

| Anthony and Stone (2010)e | Neighbourhood supportive adults | 20,749 | Grades 6–12 | US | ? | IRT | 12 | 0.81 | No |

| Chiessi et al. (2010)a | Support and emotional connection in the community | 661 | 15–18 | Town in Northern Italy | Midsized town | EFA and CFA | 4 | 0.77 | No |

| Support and emotional connections with peers | 661 | 15–18 | Town in Northern Italy | Midsized town | EFA and CFA | 4 | 0.88 | No | |

| Crean (2012) | Neighbourhood adult support | 2611 | Grades 6–8 | Upstate New York, US | Urban | CFA | 4 | 0.75 | No |

| DeHaan and Boljevac (2010) | Community supportiveness | 1424 | 11–15 | Northern Plains, US | Rural | EFA | 8 | 0.91 | No |

| Oliva et al. (2012) | Support and empowerment of youth | 2400 | 12–17 | Western Andalusia, Spain | Mixed | EFA and CFA | 6 | 0.91 | No |

| Safety/security | |||||||||

| Anthony and Stone (2010)e | Neighbourhood safety | 20,749 | Grades 6–12 | US | ? | IRT | 12 | 0.80 | No |

| Nichol et al. (2010) | Neighbourhood safety | 9114 | Grades 6–10 | Canada | Mixed | EFA | 3 | 0.68 | Yes;182 schools means; no reliability reported |

| Oliva et al. (2012) | Security | 2400 | 12–17 | Western Andalusia, Spain | Mixed | EFA and CFA | 4 | 0.87 | No |

| Meier et al. (2008) | Neighbourhood risk | 85,301 | 10–19 | Iowa, USA | Mixed | EFA | 7 | 0.80 | No |

| Detachment | |||||||||

| Baheiraei et al., (2014)d | Low neighbourhood attachment | 753 | 15–18 | Tehran, Iran | Urban | CFA | 2 | 0.64 | No |

| Choi et al. (2006) | Lack of attachment to neighbourhood | 2336 | 10–14 | Seattle, US | Urban | CFA | 5 | 0.78 | No |

| Van Gundy et al. (2011) | Community detachment | 1310 | Grades 7–11 | Coös County and Southern New Hampshire, US | Mixed | EFA | 3 | 0.74 | No |

| Disorganisation | |||||||||

| Baheiraei et al., (2014)d | Community disorganisation | 753 | 15–18 | Tehran, Iran | Urban | CFA | 5 | 0.75 | No |

| Lee (2010) | Social disorganization | 485 | 10–15 | Southern US | ? | EFA and CFA | 3 | 0.45 | No |

| Ward and Laughlin (2003) | Social disorganization | 6504 | Grades 7–12 | US | Mixed | EFA | 6 | 0.69 | Yes;72 schools; dispersion around the mean; coefficient of variation used to examine reliability |

| Winstanley et al. (2008) | Neighbourhood disorganization | 38,115 | 12–17 | US | Mixed | EFA | 8 | 0.73 | No |

| Disorder/deterioration | |||||||||

| Ewart and Suchday (2002) | Neighbourhood disorder | 212 | High school students | Baltimore, US | Urban | EFA | 11 | 0.88 | No |

| Law and Barber (2007) | Problems in the neighbourhood | 676 | Grades 5 and 8 | Ogden, Utah, US | ? | EFA | 3 | 0.79 | No |

| Suchday et al. (2006)c | Neighbourhood disorder | 163 | Grade 10 | New Delphi, India | Urban | CFA | 6 | 0.76 | No |

| Vowell (2007) | Neighbourhood deterioration | 8072 | Grades 10 -12 | Southern state in the US | Mixed | CFA | 5 | 0.75 | No |

| Wilson et al. (2005) | Neighbourhood disorder | 369 | Middle schools | Three states in the US | ? | EFA | 6 | 0.87 | No |

| Social cohesion | |||||||||

| Kerrigan et al. (2006) | Neighbourhood social cohesion | 343 | 14–19 | Baltimore, US | Urban | EFA | 3 | 0.79 | No |

| Community integration | |||||||||

| Law and Barber (2007) | Community social integration | 676 | Grades 5 and 8 | Ogden, Utah | ? | EFA | 3 | 0.63 | No |

| Sorribas et al. (2014) | Community integration | 191 | Grade 11 and 12 | Barcelona, E and W Valles of Catalonia, Spain | ? | EFA | 3 | 0.62 | No |

| Rewards for prosocial involvement | |||||||||

| Baheiraei et al. (2014)d | Rewards for prosocial environment | 753 | 15–18 | Tehran, Iran | Urban | CFA | 2 | 0.83 | No |

| Social capital | |||||||||

| Vafaei et al. (2014) | Social capital | 23,532 | 11–15 | Canada | Mixed | EFA and CFA | 5 | 0.76 | Yes; 436 school means; no reliability reported |

| Quality | |||||||||

| Ceballo et al. (2004) | Neighbourhood quality | 262 | Grades 7 and 8 | Midwest city in the US | Midsized city | EFA | 4 | 0.61 | Yes- 20 Census tracts, mean – no reliability |

| van den Bree et al., (2009)b | Neighbourhood quality | 10,433 | 11–18 | US | Mixed | EFA | 6 | 0.63 | No |

| Available activities | |||||||||

| Oliva et al. (2012) | Availability of youth activities | 2400 | 12–17 | Western Andalusia, Spain | Mixed | EFA and CFA | 4 | 0.80 | No |

| Social resources | |||||||||

| Widome et al. (2008)f | Neighbourhood social resources | 118 | 11–13 | Minneapolis, US | Urban | EFA | 8 | 0.76 | No |

| Social climate | |||||||||

| Zani et al. (2001) | Social climate | 823 | 14–19 | North Central Italy | Mixed | EFA | 2 | 0.64 | No |

| Youth behaviour | |||||||||

| Anthony and Stone (2010)e | Neighbourhood youth behaviour | 20749 | Grades 6–12 | US | ? | IRT | 8 | 0.87 | No |

| Community participation | |||||||||

| Sorribas et al. (2014) | Community participation | 191 | Grade 11 and 12 | Barcelona, E and W Valles of Catalonia, Spain | ? | EFA | 6 | 0.63 | No |

| Pleasantness of living area | |||||||||

| Zani et al. (2001) | Pleasantness of living area | 823 | 14–19 | North Central Italy | Mixed | EFA | 4 | 0.68 | No |

| Protective community | |||||||||

| Clark et al. (2011)d | Community protective | 907 | Grades 10 and 12 | Virginia, US | Mixed | EFA | 7 | 0.80 | No |

EFA = Exploratory Factor Analysis; CFA = Confirmatory Factor Analysis; IRT= Item Response Theory; US=United States of America

This is a shortened version of the scale used by Albanesi et al. (2007)

The questions utilised are the same as Ward and Laughlin (2003) Social Disorder Scale and both use US National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) data however, the subsample varies slightly

Adapted from Ewart and Suchday (2002)

Adapted from the Communities-that-Care (CTC) Questionnaire- this questionnaire also has measures about norms and availability of substances that were not extracted for this review as per the inclusion criteria

Anthony and Stone (2010) secondary analysis of the School Success Profile

Widome et al. (2008) also had a scale of intention to contribute but this was not included because it had several items that were not geographically bound

2.6. Synthesis

A narrative approach was used to synthesise the results of the review. To support this, each measure discussed in the manuscripts was coded based on the author's terminology (i.e. collective efficacy, social capital, social control, etc.), and these were then grouped into conceptual themes, for example, informal social control, collective monitoring and collective social control were all grouped as social control. This approach was used in order to differentiate each author's conceptualisation of the social process under study (see Table 2). Secondly, the items used to measure each conceptual theme were coded in order to critically assess similarities and differences within and between conceptual themes (for details on item coding see Appendix B).

In order to ensure that the measurement instruments were of sufficient quality to draw appropriate conclusions, it was decided post-hoc that studies where the instrument reporting was deemed poor quality (based on lack of reliability and structural validity reporting from the COSMIN checklist) would not be included in the narrative synthesis. This was due to a large number of studies with poor quality reporting or insufficient information to make an assessment of quality. Specifically, if a study's instrument reporting was rated as poor on any question in the modified COSMIN it was considered of poor quality. We used this cut-off in line with the “worst score counts” algorithm outlined in Mokkink et al. (2012). As a consequence of this, any study not reporting reliability, in terms of internal consistency and structural validity of each measure, was not included in the narrative synthesis.

3. Results

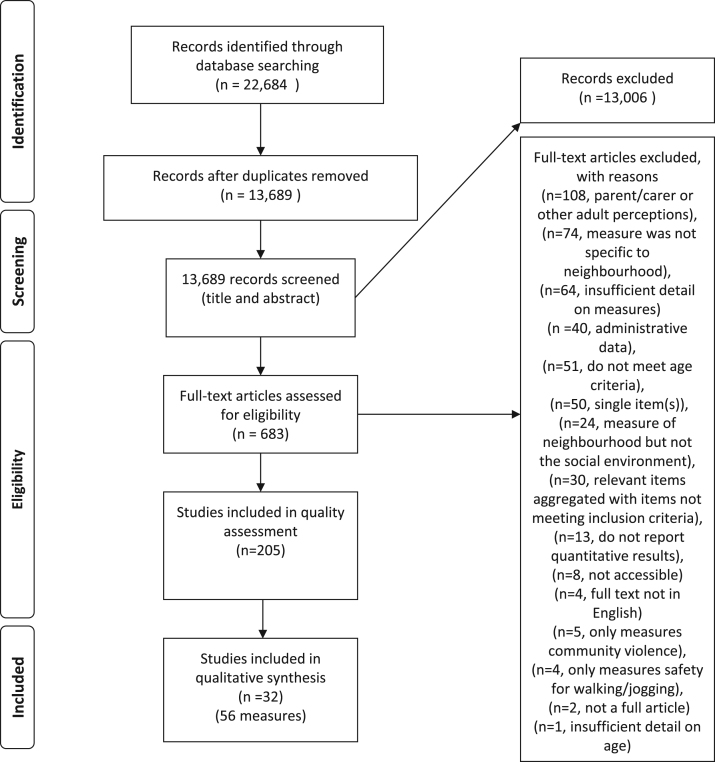

The search yielded a total of 13689 unique articles. Scanning these titles and abstracts yielded 683 articles that were further assessed for eligibility through full-text screening. Inter-rater agreement in the sample of 15% of titles and abstracts double-screened was 97% which suggested good agreement between the reviewers. Outstanding disagreements were resolved by the two reviewers through discussion. Upon screening the full-texts of the 683 articles, 205 met the inclusion criteria and were further assessed for quality using the COSMIN checklist. This led to exclusion of 651 articles. Thus a total of 32 studies (containing 56 unique measures) were rated as sufficient quality to include in the narrative synthesis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram showing search results and exclusions.

Of the 32 studies, the majority were conducted in the Europe or North America (US = 21). Only 2 studies were conducted in regions outside of Europe or North America. Approximately an equal number of studies were conducted in urban and mixed areas. Only one study was conducted in a solely rural environment. One paper used item response theory to examine reliability and structural validity; all others used classical test theory methods. Moreover, only five studies derived aggregate neighbourhood measures, with four of these using school as a proxy for residential neighbourhood. Reliability of aggregate neighbourhood measures was not addressed for most of these studies.

General characteristics of the measures included in this review are presented in Table 2. Of the 56 social environment measures the minimum number of items was two and the maximum was 15. The minimum Cronbach's alpha was 0.45 and the maximum was 0.92. It has been suggested that an alpha between .70 and .90 is desirable, as an alpha that is too high may suggest that some items are redundant (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011); just over half of the 56 measures fell within this range. As shown in Table 2, concepts relating to sense of community belonging and neighbourhood support were the most prevalent.

3.1. How do studies conceptualise and operationalise neighbourhood social measures?

Many studies based their conceptualisation of neighbourhood measures on broader theoretical models. The theoretical models that were discussed in studies most frequently were: 1) the social development model (which is the basis for the Communities that Care Survey) (Baheiraei et al., 2014, Mayberry et al., 2009, Widome et al., 2008) 2) Bronfenbrenner's ecological systems theory (Anthony and Stone, 2010, Lee, 2010 (8),2010, 1664-1693, Neumann et al., 2010, Oliva et al., 2012, Perez-Smith et al., 2001), 3) the social disorganisation model (Mayberry et al., 2009, Perez-Smith et al., 2001, Vowell, 2007, Ward and Laughlin, 2003) and 4) theories of sense of community (Albanesi et al., 2007, Chiessi et al., 2010, Zani et al., 2001).

An overarching theme within these bodies of research was that the various measures of the neighbourhood social environment are somehow interconnected. For example, Oliva et al. (2012) describe the concepts of neighbourhood assets, neighbourhood social capital, social organisation, trust, neighbourhood attachment or belonging, and collective efficacy as associated concepts when discussing how community contributes to the empowerment and maturity of adolescents.

“In some ways, this claim is similar to the concept of social capital, which is understood as those features of social organization, such as existing social networks and mutual trust, which facilitate action and cooperation for mutual benefit between members of a community (Halpern, 2005, Putnam, 1993). According to some authors, this social capital has a positive influence on the feeling of emotional attachment or belonging to the neighbourhood in which the members reside. This may increase their desire to actively engage in community service, which has been defined by some as collective efficacy (Cancino, 2005)” – Oliva et al. (2012) p. 564.

Another example of how conceptualisations of various social neighbourhood measures overlap is addressed in the discussion of social cohesion. Vafaei et al. (2014) considered their social capital measure as incorporating elements of cooperation, trust and cohesion. The authors then discuss social cohesion as based on interpersonal relationships and the availability of safe places to spend time and interact. Meier, Slutske, Arndt, and Cadoret (2008) discussed their measure in terms of collective efficacy, stating that they used items that referred to social cohesion as well as informal social control; however, they use the more generic term of “neighbourhood risk” to label their measure. In contrast, social cohesion was discussed in other research as an overarching domain. For example, Van Gundy, Stracuzzi, Rebellon, Tucker, and Cohn (2011) described their measures of community attachment and detachment as being two components of cohesion.

Additionally, although some authors stated that different concepts are used in their analysis, there is evidence that these concepts were not always theoretically distinct. For example, van de Bree et al.’s (2009) “neighbourhood quality” measure used the same items (although anchored in opposite directions) with an adjusted sample as Ward and Laughlin's (2003) “social disorganization” measure.

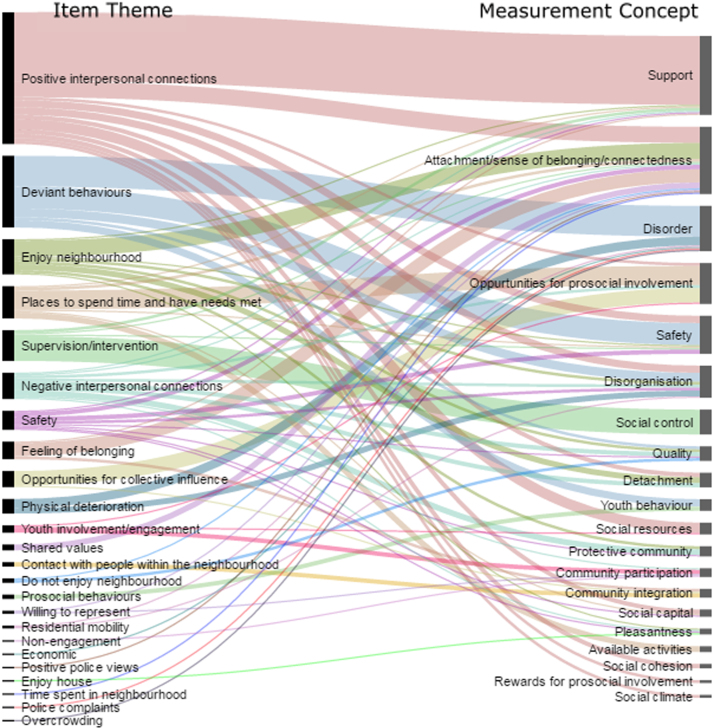

When examining the items that are used to operationalise the various thematic concepts of the adolescent social environment, a similar picture emerges (see Fig. 2). There was much overlap in the items used to measure the various concepts. For example, items that illicit information of adolescent's perceptions of deviant behaviours appeared in scales that were conceptually defined as neighbourhood safety, disorder, disorganisation, quality, and youth behaviour. Similarly, items asking about adolescent's perceptions of positive interpersonal connections in their neighbourhood were utilised in measures of a range of concepts including support, sense of belonging, safety, resources, social capital and social cohesion. Across studies, neighbourhood safety was presented as both a conceptual theme as well as an item used to measure various concepts, such as, quality, social capital, attachment/sense of belonging/connectedness. These results further indicate that the distinction between concepts is blurred thus suggesting the need for a greater differentiation between some concepts and a theoretical linking of highly related concepts.

Fig. 2.

Alluvial diagram of question item themes used in measurement of various author defined concepts. Height of nodes indicates number of items in each theme. Diagram was created using http://app.raw.densitydesign.org/.

Based on the items included in the measures, some concepts did emerge as divergent from others. Across studies, the concept of social control was only measured using questions about supervision and intervention of behaviours within the neighbourhood. Moreover, the concepts of disorder and safety, for the most part, were measured using items regarding deviant behaviours; however, disorder measures also included some items referring to physical deterioration.

4. Discussion

The aim of this paper was to review measures of the adolescent neighbourhood social environment. One of our most stark findings was how many studies were identified as having poor quality reliability and/or validity reporting. This likely exacerbates confusion surrounding the concepts related to the neighbourhood social environment, both in research and in public policy. Having good quality measurement instruments is necessary for identifying associations between the neighbourhood social environment and adolescent health outcomes; lack of methodological uniformity is, therefore, likely to be a contributing factor to inconsistent findings. Despite the finding that many studies did not meet the quality cut-off, this review identified 56 measures of the neighbourhood social environment, where studies had sufficient quality in reporting. These measurement tools represent an encouraging basis in the field of measuring the neighbourhood social environment of adolescents. However, there is a need for further development or validation of existing measures outside of the US, particularly in non-westernised countries. Moreover, very few studies extend their measure to ecological areas, and those that do often use school as a proxy for neighbourhood. This is of concern, as the questions referred to the area in which adolescents live rather than area where they attend school. Consequently, these aggregate scales suffer from issues of face validity as adolescents may not live in the same area as where they go to school. Even fewer studies reported attempts to quantify the reliability and validity of ecological measures. This finding mirrors that of Sampson et al. (2002) and highlights that many studies addressing neighbourhood characteristics examine individual perceptions, but do not extend these measure to the neighbourhood level. This limits the informative power of these studies in terms of place-based interventions. Only one study utilised item response theory techniques; these techniques are useful for non-linear items and can be extended to neighbourhood level measures and are therefore of use in future studies (Matsueda & Drakulich, 2016).

We found little consistency in how adolescent neighbourhood social environments have been both conceptualised and operationalised. When operationalised the various concepts of adolescent neighbourhood measures were largely indistinct. Again, this is similar to findings from the previous review by Sampson et al. (2002). There seems to be some understanding within the literature that various concepts are somehow related; however, a clear framework does not exist and is inconsistent and contradictory across studies. By scrutinising the literature, it appears that one neighbourhood measure – social control - appears distinct from other concepts, in that it was formulated only by measures of supervision and intervention by adults in the neighbourhood. We also found that neighbourhood disorder (physical and social) and safety were largely distinct from measures such as support, cohesion, and attachment/sense of community and belonging, which used a high proportion of measures that deal with relationships and ties within the community. In advancing theory, emerging work conducted with different populations, such as adults, may prove informative.

Another issue that influenced the consistency of neighbourhood measures, was that although all survey questions made reference to a geographical area where adolescents lived, there was no standardised definition of neighbourhood; i.e. Zani et al. (2001) used the term “town” as a whole, which differs greatly from ‘the street where you live’ or local area. Different neighbourhood boundary definitions may apply in urban and rural locales; therefore further research is needed to better understand the perceptions of neighbourhood boundaries among young people who reside in different contexts.

Overall, we found that despite the large number of studies of adolescents that have used a measure of the neighbourhood social environment since 2001, it appears that little progress has been made in terms of clarity of concepts. This has important implications for future research. In light of this, several technical recommendations are relevant and in line with many of the recommendations from Brandt, Ward, Dawes, and Flisher (2005). First, we suggest that studies not using a previously valid and reliable scale report on the psychometric properties of their measure, so that the research findings can be appropriately interpreted. Adaptions made to existing measurement scales, or use of scales in different cultural contexts, should be documented and the psychometric properties noted. Moving forward, researchers should stress improved conceptualisation and transparency in reporting; authors of original studies should provide a clear definition of the type/s of neighbourhood social environment that their measurement tool is attempting to assess and record all items in scale measures. This would ensure that results can be understood with greater clarity in terms of what is measured and therefore research and policy implications can be better understood. This is of utmost importance, as a lack of comparability of studies limits growth in the field (Brandt et al. 2005). Whether certain subdomains are distinct from others should be further examined with empirical evidence from cross-cultural studies (Reimers et al., 2013). Additionally, from a developmental perspective, whether measures are invariant for younger versus older adolescents is an important area of future research. Furthermore, studies should extend beyond the psychometric to the ecological (ecometric) as this is a key element in neighbourhood research (Sampson et al., 2002). Appropriate neighbourhood boundaries based on residence, and at an appropriate spatial-scale, should be selected when possible. Finally, we suggest that reviews of effects of concepts relating to the social environment should consider multiple typologies in search terms in order to cover all studies.

A quality checklist of studies examining ecological constructs would be useful in future studies and would allow for the structural validity of neighbourhood measures to be determined without examining the individual level analogue constructs. However, in the absence of a standardised assessment tool, reliability reporting should be conducted using methods which draw on multilevel modelling to examine reliability, such as those outlined in Raudenbush and Sampson (1999). Convergent and divergent validity can be tested using similar approaches used in individual level constructs, by examining associations with other neighbourhood measures that are theoretically thought to be correlated (Matsueda & Drakulich, 2016). It may be that individual level and neighbourhood level constructs vary in their composition and therefore methods to test their structural validity are needed. This is a topic that has received little attention but recent studies utilising methods such multilevel factor analysis provide a useful focus for future research (Dunn, Masyn, Johnston, & Subramanian, 2015).

There are several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results of this review. First, given the search strategy, we were unable to identify unpublished studies or studies that were not published in indexed journals. Studies in languages other than English were also not included and the majority of the identified studies were conducted in high income countries, thus limiting the generalisability of the findings. The scope of this review did not address self-reports from different sources (such as parent, teacher or non-resident perceptions of the neighbourhood). Self-reports from multiple sources may be differentially associated with adolescent health outcomes, and the validity and reliability of these measures warrant future research. Given the strict age criterion, it is possible that some studies may have been overlooked, with the majority of the sample within the age limits; however, this criterion was deemed important to ensure comparability amongst studies, particularly in the context of adolescent development. Moreover, reducing our narrative synthesis to studies that provided sufficient information on psychometric properties, and did not score poorly on reliability and validity reporting, allowed for a more refined synthesis and comparison of measures; however, this excluded some papers that may be worthy of note. Two studies worth mentioning are: Arthur, Hawkins, Pollard, Catalano, and Baglioni (2002) and Glaser, Horn, Arthur, Hawkins, and Catalano (2005) which, taken together, provide sufficient information to assess the measurement instrument qualities. These studies addressed the Communities that Care Survey items that were included in Baheiraei et al.’s (2014) study of Iranian adolescents and were the basis for Clark et al. (2011), so the survey instrument was still represented in this review. Another key limitation of this review was that the full text screening of articles, data extraction and quality appraisal was conducted by one researcher. However, given the high level of inter-rater agreement (97%) in the title and abstract screening, we are confident that the inclusion criteria was applied appropriately. Because this review was designed to examine conceptual and operational considerations in measurement instruments, and not to produce a pooled effect size from intervention studies, missing studies are of less concern.

In conclusion, the body of literature on the adolescent social neighbourhood environment represents a complex and fragmented set of findings. There is much room for improvement in terms of moving the field forward by further explicating both theory and methods. However, existing measures based on prominent theories provide a promising base on which to build future research.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Aixa Aleman-Diaz and Joseph Hancock for comments on early drafts of this manuscript. We thank the two anonymous reviewers of this paper for their helpful comments and suggestions. We also are grateful to Gill Rhodes for her time in proof-reading the manuscript. This work was supported by the 600th Anniversary PhD Scholarship which was awarded to Gina Martin by the University of St Andrews.

Appendix A. Search term strategy used in Web of Science, Medline, ASSIA, CINAHL and PsycInfo

| Collective terms | Search terms | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Components of the social environment | “social environment*” OR “social capital” OR “social disorganisation” OR “social disorganization” OR “social disorder” OR “social cohesion” OR “social trust” OR “social control” OR “informal control” OR “social ecology” OR socioecolog* OR “collective efficacy” OR “sense of community” OR “sense of place” OR “distal factor*” OR “distal character*” OR “place character*”OR “place attachment*” OR “communities that care” OR “neighbourhood disorganisation” OR “neighbourhood disorganization” OR “neighbourhood disorder” OR “neighbourhood cohesion” OR “neighbourhood trust” OR “neighbourhood control” OR “neighbourhood problem*” OR “neighbourhood safety” OR “neighbourhood stress” OR “neighbourhood organisation” OR “neighbourhood organization” OR “neighbourhood attachment” OR “neighbourhood perception*” OR “neighbourhood qualit*” OR “neighbourhood support*” OR “neighbourhood character*” OR “neighbourhood factor*” OR “neighbourhood strength*” OR “neighbourhood satisfaction” OR “neighborhood disorganisation” OR “neighborhood disorganization” OR “neighborhood disorder” OR “neighborhood cohesion” OR “neighborhood trust” OR “neighborhood control” OR “neighborhood problem*” OR “neighborhood safety” OR “neighborhood stress” OR “neighborhood organisation” OR “neighborhood organization” OR “neighborhood attachment” OR “neighborhood perception*” OR “neighborhood qualit*” OR “neighborhood support*” OR “neighborhood character*” OR “neighborhood factor*” OR “neighborhood strength*”OR “neighborhood satisfaction” OR “community disorganisation” OR “community disorganization” OR “community disorder” OR “community cohesion” OR “community trust” OR “community control” OR “community problem*” OR “community safety” OR “community stress” OR “community organisation” OR “community organization” OR “community attachment” OR “community perception*” OR “community qualit*” OR “community support*” OR “community character*” OR “community factor*” OR “community strength*” OR “community satisfaction” |

| 2 | Population | adolescen* OR teen* OR youth OR “young people” OR “schoolchildren*” OR “school children” OR “school age*” |

Appendix B. Questions used to measure the adolescent neighbourhood social environment, grouped by theme

| Item themes | Questions (study) |

|---|---|

| Positive Interpersonal connections | Adults in my neighbourhood make me feel important (1) Adults in my neighbourhood listen to what I have to say (1) In my neighbourhood I feel like I matter to people (1) People in this neighbourhood look out for each other (6) You know most of the people in your neighbourhood (6) In the past month, you have stopped on the street to talk with someone who lives in your neighbourhood(6) People say ‘hello’ and talk to each other in the streets (8) You can trust people around here (8) I could ask for help or favour from a neighbour (8) I know many people in my neighbourhood by name (10) People in my neighbourhood encourage me to do my best (10) People in my neighbourhood care about how things are going in my life (10) I spend a lot of time with kids where I live (11) I get along with kids in my neighbourhood (11) I hang out a lot with kids in my neighbourhood (11) Everybody is willing to help each other in my neighbourhood (12) People are there for each other in my neighbourhood (12) People support each other in my neighbourhood (12) People in my neighbourhood work together to get things done (12) We look out for each other in my neighbourhood (12) If I needed help I could go to anyone in my neighbourhood (12) People in my neighbourhood pitch in to help each other (12) I feel okay asking for help from my neighbours (12) My neighbours get along well with each other (13) Adults in my community care about people my age (13) Adults in my neighbourhood or community help me when I need help (13) Adults in my neighbourhood or community let me know they are proud of me (13) Adults in my neighbourhood or community spend time talking with me (13) People in the neighbourhood could be trusted (14) People in the neighbourhood care a lot about each other (14) People in the neighbourhood are willing to help each other (14) People in your neighbourhood often help each other out (15) People in your neighbourhood often visit each other’s homes (15) If I need advice about something I could go to someone in my neighbourhood (16) There are adults in my neighbourhood that I look up to (16) If I got in trouble I know someone who would help me out in my neighbourhood (16) I know the names of a lot of people in my neighbourhood (16) I know someone I could borrow money from (for bus fare or something else) (16) I regularly stop to talk with people in my neighbourhood (16) I visit with neighbours in their homes (16) I live in a close knit community (17) People (around) here are willing to help their neighbours (17) People in my community generally get along with each other (17) The adults in my neighbourhood are concerned with the well-being of the youth (19) People my age can find adults in my neighbourhood to help solve problems (19) The adults in my neighbourhood say that young people must be heard (19) In my neighbourhood, when adults make decisions that affect young people, they listen to youth’s opinions (19) Adults in my neighbourhood value the youth (19) People my age feel valued by adults in the neighbourhood (19) There are a lot of adults I can talk to (21) Our neighbours listen to what kids have to say (21) People in my neighbourhood are proud of me (21) My neighbours notice when I do a good job (21) People in my town collaborate together (22,23) People in this place support others (22, 23) People in my town work together to improve things (22, 23) Many people in this town are willing to help each other (22, 23) In this place I feel like I can share experiences and interests with other young people (22,23) In my town people look out for each other and get along well (22) People in my town are willing to share things (22) I spend a lot of time with other adolescents that live in this place(22,23) Many of my real friends are young people that live in this town(22) I like to stay with other adolescents who live in this town (22,23) In this place, there are people able to stay beside me if I need it (22) If I need a little help, I can ask for it to someone who lives in my town (22) If I feel like talking I can generally find someone in my town to chat to (22,23) There are people here that represent an important source of moral support to me (22) In this place, it is not difficult to find someone that can give some advice if I need to make a decision (22) The friendships and connections I have with people in my neighbourhood mean a lot to me (24) I feel loyal to the people in my neighbourhood (24) Most of my friends live in this neighbourhood (24) Adults in my neighbourhood are interested in what young people in the neighbourhood are doing (25) If I had problems there are neighbours who could help me (25) People in my neighbourhood really help each other out (25) Adults in my neighbourhood encourage young people to get an education (25) Young people in my neighbourhood show respect to adults (25) Adults in my neighbourhood seem to like young people (25) Adults in my neighbourhood can be trusted (25) Many of the people in this town are available to provide help when someone needs (30) The people in this town are polite and well mannered (30) If I had a problem there are neighbours I could count on to help me (32) Most people in my community know and care for each other (32) My neighbours notice when I do a good job and let me know about it (27) There are a lot of adults I can talk to about something important (27) There are people in my neighbourhood who encourage me to do my best (27) There are people in my neighbourhood who are proud of me when I do something well (27) |

| Deviant behaviours | Teenagers in my neighbourhood are out of control (4) How often are there problems with muggings, burglaries, assaults or anything like that in your neighbourhood (9) How much of a problem is the selling and using of drugs in your neighbourhood (9) There is a lot of crime in your neighbourhood (15) A lot of drug selling goes on in your neighbourhood (15) There are lots of street fights in your neighbourhood (15) In my neighbourhood there are people who sell drugs (19) People in my neighbourhood commit crimes and hooliganisms (19) In my neighbourhood there are often fights between street gangs (19) Alcoholics and excessive drinking in public in the neighbourhood (20) What describes your neighbourhood: fights and brawls (21) What describes your neighbourhood: crime, drug selling (21) How likely are young people in the neighbourhood to get in trouble with police? (25) How likely are young people in the neighbourhood to use drugs? (25) How likely are young people in the neighbourhood to join a gang? (25) How likely are young people in the neighbourhood to drink an alcoholic beverage? (25) How likely are young people in the neighbourhood to carry a weapon such as a gun, knife or club? (25) Have any of the following happened in your neighbourhood over the past 30 days someone you lived with was robbed or mugged? (25) Have any of the following happened in your neighbourhood over the past 30 days someone in your neighbourhood was robbed or mugged? (25) Have any of the following happened in your neighbourhood over the past 30 days someone broke into your home or your neighbour's home? (25) Have any of the following happened in your neighbourhood over the past 30 days you heard gunshots? (25) Have any of the following happened in your neighbourhood over the past 30 days you saw someone selling illegal drugs? (25) Have any of the following happened in your neighbourhood over the past 30 days someone tried to get you to break the law? (25) Have any of the following happened in your neighbourhood over the past 30 days a person was murdered? (25) Have any of the following happened in your neighbourhood over the past 30 days a fight broke out between two gangs? (25) Have any of the following happened in your neighbourhood over the past 30 days someone threatened you with a weapon such as a gun, knife or club? (25) Have any of the following happened in your neighbourhood over the past 30 days you saw someone threatened with a weapon such as a gun, knife or club? (25) Have any of the following happened in your neighbourhood over the past 30 days someone offered you an alcoholic beverage? (25) Have any of the following happened in your neighbourhood over the past 30 days someone tried to sell you illegal drugs? (25) Drug dealers near my home (26, 29) Strangers drunk near my house (26, 29) Adults arguing loudly on streets (26) Neighbours complain about crime (26,29) “Shooting gallery” near my home (26, 29) Someone arrested or in jail (26, 29) Gang fight near my home (26, 29) Cars speeding on my street (26) How often people drink alcohol on the streets in their neighbourhood?(28) How often someone gets robbed in their neighbourhood?(28) How often someone uses drugs in their neighbourhood?(28) How often the police arrest someone in their neighbourhood?(28) How often there is a fight in their neighbourhood?(28) How often someone steals something in their neighbourhood?(28) |

| Supervision/intervention | Would adults try to stop if someone was spray painting a wall in your neighbourhood? (2, 3) Would adults try to stop if someone was trying to steal a car in your neighbourhood? (2, 3) Would adults try to stop if teenagers were fighting in the street in your neighbourhood? (2, 3) Would someone call the police if someone was spray painting a wall in your neighbourhood? (2, 3) Would someone call the police if someone was trying to steal a car in your neighbourhood? (2, 3) Would someone call the police if teenagers were fighting in the street in your neighbourhood? (2, 3) If someone in my neighbourhood or community saw me doing something wrong, they would tell my parents (or adults who live with me) (13) How likely adults in their neighbourhood would be to intervene if children or teenagers were hanging out on the street? (14) How likely adults in their neighbourhood would be to intervene if children or teenagers spray painting graffiti? (14) How likely adults in their neighbourhood would be to intervene if children or teenagers showing disrespect to an adult? (14) How likely adults in their neighbourhood would be to intervene if children or teenagers fighting? (14) The adults in my neighbourhood reprimand us if we damage trees or public gardens(19) The adults in my neighbourhood would try to prevent young people from burning or breaking things (trashcan, etc.) (19) If a young person in my neighbourhood tried to damage a car, an adult would try to stop him/her(19) In my neighbourhood if you get into hooliganism an adult will scold you (19) If a group of children were skipping school and hanging out on the street corner, how likely is it a neighbour would do anything about it? (20) If some children were spray-painting graffiti on a local building, how likely is it that your neighbours would do something about it? (20) If a child was showing disrespect to an adult, how likely is it that people in your neighbourhood would scold that child? (20) If I did something wrong, adults in my neighbourhood who knew about it would probably tell the adults I live with (25) Adults in my neighbourhood would say something to me if they saw me doing something that could get me into trouble (25) Most adults in my community keep an eye on what kids are up to (32) |

| Enjoy neighbourhood | If, for any reason, you had to move from here to some other neighbourhood, how happy or unhappy would you be (6) On the whole, how happy are you living in your neighbourhood (6) Do you think the area in which you live is a good place to live?(7) Overall, how satisfied are you with your neighbourhood (9) How would you rate the physical appearance of your neighbourhood (9) If I had to move, I would miss the neighbourhood I live in now (10, 21, 27) I like the neighbourhood that I live in (10, 30) I like hanging out around where I live (11) I like my neighbourhood (21) I think this is a good place to live in (22,23) This is a pretty town (22,23) As compared to others my town has many advantages (22,23) Some of our local holidays and celebrations attract many people because they are very nice and well organized (22) I like to notice that when some local events are organized, many people participate and are involved (22) During local holiday celebrations, I feel proud to live here (22) I am happy with the neighbourhood I live in (25) I like the neighbourhood or the area where I live (27) It would take a lot for me to move away from this town (30) |

| Negative interpersonal connections | Adults in my neighbourhood don’t care about people my age (1) My neighbours do not care what my friends do in this area (4) It is difficult for kids to make friends in my neighbourhood (4) Neighbours do not look out for others (5) Do not know most people in neighbourhood (5) Do not stop and talk to neighbours (5) People in this/my community like to gossip (17) People in this/my community know too much about each other’s business (17) Once you get a bad reputation around here it is hard to get rid of (17) There are few chances to meet people in this town (30) In this town it is difficult to have good social relationships (30) I don’t like the people in my area (30) Very few people in my neighbourhood know who I am (31) In my neighbourhood, away from school, people sometimes treat me unfairly because of my race or ethnicity (32) |

| Places to spend time and have needs met | I often spend time playing or doing things in my neighbourhood (11) There are good places to spend free time (8) There are places for kids my age to go that are alcohol and drug free (13) During vacation, there are many activities for young people to have fun in my neighbourhood (19) Young people in my neighbourhood have places to get together during bad weather (19) The young people in my neighbourhood can do so many things they rarely get bored (19) There are few neighbourhoods, such as my own, where there are as many activities for young people(19) In this town, there are many places loved and appreciated by all inhabitants (22) In this place, it is easy to find information about things that interest young people (22) In this place, young people can find many opportunities to amuse themselves (22,23) This place gives me opportunities to do many different things (22) There are activities that young people can do in my town (22) In this place, there are enough opportunities to meet other boys and girls (22,23) In this place, there are many situations and initiatives that involve young people like me (22, 23) In this place, there are enough initiatives for young people (22,23) This town gives me an opportunity to do a lot of different things (30) If I need help this town has many excellent services to meet my needs (30) In my neighbourhood, there are a lot of fun things for people my age to do (25) |

| Feeling of belonging | I identify with my community (19) I feel I am part of my community (19) I feel very connected to my neighbourhood (19) Living in my neighbourhood makes me feel that I am part of a community(19) I feel like I belong to this town (22,23) I think I have a lot in common with other young people that live here (22) The neighbourhood I live in is a big part of who I am (24) Living in this neighbourhood gives me a feeling of belonging (24) I feel like I belong here (30) I feel very identified with my neighbourhood (31) I feel that the neighbourhood belongs to me (31) |

| Safety | Do not feel safe in neighbourhood (5) Do you usually feel safe in your neighbourhood (6) I feel safe in the area that I live (7) It is safe for younger children to play outside during the day (7, 8) My community is safe (17) Some of my friends are afraid to come to my neighbourhood (19) I feel safe in my neighbourhood (21, 25) I feel safe here (22, 30) Generally, my neighbourhood is a safe place to live (32) I feel safe in my neighbourhood, or the place that I live (27) |

| Opportunities for collective influence | Honestly, I feel that if we engaged more, we would be able to improve things for young people in this town (22, 23) If only we had the opportunity, I think that we could be able to organize something special for our town (22, 23) If the people here were to organize, they would have good chance of reaching their desired goals (22, 23, 30) I think the people who live here could change things that are not properly working for the community (22, 23) If you want to, in this town it possible to participate in local politics (30) My opinions are well received in my neighbourhood(31) |

| Physical deterioration | There are empty and abandoned buildings in your neighbourhood (15) There is a lot of graffiti in your neighbourhood (15) How common is broken cars on the street (18) How common is houses looking like they need repair (18) How common is trash on the streets (18) Litter or trash on the sidewalks or streets in the neighbourhood (20) Graffiti on buildings and walls in the neighbourhood (20) What describes your neighbourhood: graffiti (21) What describes your neighbourhood: abandoned buildings (21) No. of vacant houses (26) |

| Youth involvement/engagement | I am interested in finding out about new things in my neighbourhood (16) Kids in my neighbourhood are involved in decision making (21) I take part in organizations in my community (31) I take part in social activities in my neighbourhood (31) I take part in social or citizen groups (31) |

| Do not enjoy neighbourhood | Would be happy to move (5) Not happy in neighbourhood (5) My neighbourhood is boring (11) |

| Shared values | I think of myself as the same as people in my neighbourhood (24) I think I agree with most people in my neighbourhood about what is important in life (24) I generally respect the habits and traditions of this town (30) There are some holidays or anniversary days that in this town that involve most people (30) |

| Prosocial behaviours | How likely are young people in the neighbourhood to make good grades? (25) How likely are young people in the neighbourhood to graduate from high school? (25) How likely are young people in the neighbourhood to find a job or go to college after completing high school? (25) |

| Contact with people within the neighbourhood | Frequency with neighbours within the community (20) Frequency with church leaders within the community (20) Frequency with community leaders within the community (20) |

| Residential mobility | People move in and out of your neighbourhood often (15) Families moving in and out of houses in your neighbourhood (18) |

| Willing to represent | If there is trouble I will represent my neighbourhood (24) I attend the calls for support made within my community (31) |

| Positive police views | Usually I can count on the police if am having a problem or need help (32) |

| Police complaints | People complain about police (26) |

| Non-engagement | I don’t take part in my neighbourhood festive activities (31) |

| Enjoy house | I like the house in which I live (30) |

| Overcrowding | How common is 2 or 3 families living in one house (18) |

| Economic | Number of neighbours with food stamps (26) |

| Time spent in neighbourhood | I spend most of my free time in the neighbourhood where I live (24) |

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

- 8.

- 9.

- 10.

- 11.

- 12.

- 13.

- 14.

- 15.

- 16.

- 17.

- 18.

- 19.

- 20.

- 21.

- 22.

- 23.

- 24.

- 25.

- 26.

- 27.

- 28.

- 29.

- 30.

- 31.

- 32.

References

- Albanesi Cinzia, Cicognani Elvira, Zani Bruna. Sense of community, civic engagement and social well‐being in Italian adolescents. Journal of Community Applied Social Psychology. 2007;17(5):387–406. [Google Scholar]

- Ammann-Reiffer Corinne, Bastiaenen Caroline H.G., de Bie Rob A., van Hedel Hubertus J.A. Measurement properties of gait-related outcomes in youth with neuromuscular diagnoses: A systematic review. Physical Therapy. 2014;94(8):1067–1082. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony Elizabeth, Stone Susan. Individual and contextual correlates of adolescent health and well-being. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services. 2010;91(3):225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur Michael W., Hawkins J. David, Pollard John A., Catalano Richard F., Baglioni A.J.J. Measuring risk and protective factors for use, delinquency, and other adolescent problem behaviors the communities that care youth survey. Evaluation Review. 2002;26(6):575–601. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0202600601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baheiraei Azam, Soltani Farzaneh, Ebadi Abbas, Cheraghi Mohammad Ali, Foroushani Abbas Rahimi, Catalano Richard F. Psychometric properties of the Iranian version of ‘Communities That Care Youth Survey’. Health Promotion International. 2014 doi: 10.1093/heapro/dau062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker Edward D., Trentacosta Christopher J., Salekin Randall T. Are impulsive adolescents differentially influenced by the good and bad of neighborhood and family? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120(4):981–986. doi: 10.1037/a0022878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt René, Ward Catherine L., Dawes Andrew, Flisher Alan J. Epidemiological measurement of children’s and adolescents' exposure to community violence: Working with the current state of the science. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2005;8(4):327–342. doi: 10.1007/s10567-005-8811-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryden Anna, Roberts Bayard, Petticrew Mark, McKee Martin. A systematic review of the influence of community level social factors on alcohol use. Health Place. 2013;21:70–85. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes Hilary F., Chen Meng-Jinn, Miller Brenda A., Maguin Eugene. The relative importance of mothers' and youths' neighborhood perceptions for youth alcohol use and delinquency. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36(5):649–659. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9154-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes Hilary F., Miller Brenda A., Chamratrithirong Aphichat, Rhucharoenpornpanich Orratai, Cupp Pamela K., Atwood Katharine A.…Chookhare Warunee. The roles of perceived neighborhood disorganization, social cohesion, and social control in urban Thai adolescents' substance use and delinquency. Youth Society. 2013;45(3):404–427. doi: 10.1177/0044118X11421940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancino Jeffrey Michael. The utility of social capital and collective efficacy: Social control policy in nonmetropolitan settings. Criminal Justice Policy Review. 2005;16(3):287–318. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballo Rosario, McLoyd Vonnie C., Teru Toyokawa. The influence of neighborhood quality on adolescents’ educational values and school effort. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004;19(6):716–739. [Google Scholar]

- Chiessi Monica, Cicognani Elvira, Sonn Christopher. Assessing Sense of Community on adolescents: Validating the brief scale of Sense of Community in adolescents (SOC‐A) Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;38(3):276–292. [Google Scholar]

- Choi Yoonsun, Harachi Tracy W., Catalano Richard F. Neighborhoods, family, and substance use: Comparisons of the relations across racial and ethnic groups. Social Service Review. 2006;80(4):675–704. doi: 10.1086/508380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark Trenette T., Nguyen Anh B., Belgrave Faye Z. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and marijuana use among African-American rural and urban adolescents. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2011;20(3):205–220. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2011.581898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crean Hugh F. Youth activity involvement, neighborhood adult support, individual decision making skills, and early adolescent delinquent behaviors: Testing a conceptual model. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2012;33(4):175–188. [Google Scholar]

- DeHaan Laura, Boljevac Tina. Alcohol prevalence and attitudes among adults and adolescents: Their relation to early adolescent alcohol use in rural communities. Journal of child & adolescent substance abuse. 2010;19(3):223–243. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2010.488960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeHaan Laura, Boljevac Tina, Schaefer Kurt. Rural community characteristics, economic hardship, and peer and parental influences in early adolescent alcohol use. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;30(5):629–650. doi: 10.1177/0272431609341045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn Erin C., Masyn Katherine E., Johnston William R., Subramanian S.V. Modeling contextual effects using individual level data and without aggregation: An illustration of multilevel factor analysis (MLFA) with collective efficacy. Population Health Metrics. 2015;13(12) doi: 10.1186/s12963-015-0045-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earls Felton, Carlson Mary. The social ecology of child health and well-being. Annual Review of Public Health. 2001;22(1):143–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.22.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewart Craig K., Suchday Sonia. Discovering how urban poverty and violence affect health: Development and validation of a Neighborhood Stress Index. Health Psychology. 2002;21(3):254–262. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser Renita R., Horn M. Lee Van, Arthur Michael W., Hawkins J. David, Catalano Richard F. Measurement properties of the Communities That Care® Youth Survey across demographic groups. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2005;21(1):73–102. [Google Scholar]

- Gough David, Oliver Sandy, Thomas James. Sage; 2012. An introduction to systematic reviews. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern David. Polity; Cambridge: 2005. Social capital. [Google Scholar]

- Hawe Penelope, Shiell Alan. Social capital and health promotion: A review. Social Science Medicine. 2000;51(6):871–885. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson Nicki, Denny Simon, Ameratunga Shanthi. Social and socio-demographic neighborhood effects on adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of multi-level studies. Social Science Medicine. 2014;115:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karcher Michael J., Sass Daniel. A multicultural assessment of adolescent connectedness: Testing measurement invariance across gender and ethnicity. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2010;57(3):274–289. doi: 10.1037/a0019357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan Deanna, Witt Stephanie, Glass Barbara, Chung Shang-en, Ellen Jonathan. Perceived neighborhood social cohesion and condom use among adolescents vulnerable to HIV/STI. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10(6):723–729. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law Julianne H.J., Barber Brian K. Neighborhood conditions, parenting, and adolescent functioning. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2007;14(4):91–118. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Chang-Hun. An ecological systems approach to bullying behaviors among middle school students in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010 (8),2010, 1664-1693;26(8):1664–1693. doi: 10.1177/0886260510370591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, G., Gavine, A., Currie, C., Inchley, J., & Miller, M. (2014). Conceptualizing, measuring and evaluating constructs of the adolescent neighbourhood social environment: a systematic review PROSPERO 2014:CRD42014014721 Available from 〈http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42014014721〉. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Matsueda Ross L., Drakulich Kevin M. Measuring collective efficacy a multilevel measurement model for nested data. Sociological Methods Research. 2016;45(2):191–230. [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry Megan L., Espelage Dorothy L., Koenig Brian. Multilevel modeling of direct effects and interactions of peers, parents, school, and community influences on adolescent substance use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38(8):1038–1049. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9425-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson Kerri E., Kerr Susan, Antony Morgan, McGee Elizabeth, Cheater Francine M, McLean Jennifer, Egan James. The association between family and community social capital and health risk behaviours in young people: An integrative review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):971. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier Madeline H., Slutske Wendy S., Arndt Stephan, Cadoret Remi J. Impulsive and callous traits are more strongly associated with delinquent behavior in higher risk neighborhoods among boys and girls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(2):377–385. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokkink Lidwine B., Terwee Caroline B., Patrick Donald L., Alonso Jordi, Stratford Paul W., Knol Dirk L.…De Vet Henrica C.W. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: An international Delphi study. Quality of Life Research. 2010;19(4):539–549. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9606-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokkink Lidwine B., Terwee Caroline B., Patrick Donald L., Alonso Jordi, Stratford Paul W., Knol Dirk L., Bouter Lex M., de Vet Henrica C.W. University Medical Center; Amsterdam: 2012. COSMIN checklist manual. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow Virginia. Conceptualising social capital in relation to the well‐being of children and young people: A critical review. The Sociological Review. 1999;47(4):744–765. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow Virginia. Young people's explanations and experiences of social exclusion: Retrieving Bourdieu's concept of social capital. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy. 2001;21(4–6):37–63. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann Anna, Barker Edward D., Koot Hans M., Maughan Barbara. The role of contextual risk, impulsivity, and parental knowledge in the development of adolescent antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119(3):534–545. doi: 10.1037/a0019860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichol Marianne, Janssen Ian, Pickett William. Associations between neighborhood safety, availability of recreational facilities, and adolescent physical activity among Canadian youth. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2010;7(4):442–450. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.4.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva Alfredo, Antolín Lucía, López Ana María. Development and validation of a scale for the measurement of adolescents' developmental assets in the neighborhood. Social Indicators Research. 2012;106(3):563–576. [Google Scholar]

- Paalman Carmen H., Terwee Caroline B., Jansma Elise P., Jansen Lucres M.C. Instruments measuring externalizing mental health problems in immigrant ethnic minority youths: A systematic review of measurement properties. PloS One. 2013;8(5):e63109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paiva Paula Cristina Pelli, de Paiva Haroldo Neves, de Oliveira Filho Paulo Messias, Lamounier Joel Alves, e Ferreira Efigênia Ferreira, Ferreira Raquel Conceição.…Zarzar Patrícia Maria. Development and validation of a social capital questionnaire for adolescent students (SCQ-AS) PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e103785. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Smith Alina M., Albus Kathleen E., Weist Mark D. Exposure to violence and neighborhood affiliation among inner-city youth. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30(4):464–472. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam Robert D. The prosperous community. The american prospect. 1993;4(13):35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush Stephen W., Sampson Robert J. Ecometrics: toward a science of assessing ecological settings, with application to the systematic social observation of neighborhoods. Sociological methodology. 1999;29(1):1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Reimers Anne K., Mess Filip, Bucksch Jens, Jekauc Darko, Woll Alexander. Systematic review on measurement properties of questionnaires assessing the neighbourhood environment in the context of youth physical activity behaviour. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson Robert J., Morenoff Jeffrey D., Gannon-Rowley Thomas. Assessing” neighborhood effects”: Social processes and new directions in research. Annual Review of Sociology. 2002:443–478. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer-McDaniel Nicole J. Conceptualizing social capital among young people: Towards a new theory. Children Youth and Environments. 2004;14(1):153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Sorribas Jaume del Campo, Vila Banos Ruth, Marín Gracia, María Angeles. The Perception of Community Social Support among Young Foreign-Born People in Catalonia. Revista de Cercetare şi Intervenţie Socială. 2014;45:75–90. [Google Scholar]