Abstract

Sexual minority youth (SMY) experience elevated rates of adverse sexual health outcomes. Although risk factors driving these outcomes are well studied, less attention has been paid to protective factors that potentially promote health and/or reduce negative effects of risk. Many factors within interpersonal relationships have been identified as protective for the sexual health of adolescents generally. We sought to systematically map the current evidence base of relationship-level protective factors specifically for the sexual health of SMY through a systematic mapping of peer-reviewed observational research. Articles examining at least one association between a relationship-level protective factor and a sexual health outcome in a sample or subsample of SMY were eligible for inclusion. A total of 36 articles reporting findings from 27 data sources met inclusion criteria. Included articles examined characteristics of relationships with peers, parents, romantic/sexual partners, and medical providers. Peer norms about safer sex and behaviorally specific communication with regular romantic/sexual partners were repeatedly protective in cross-sectional analyses, suggesting that these factors may be promising intervention targets. Generally, we found some limits to this literature: few types of relationship-level factors were tested, most articles focused on young sexual minority men, and the bulk of the data was cross-sectional. Future work should expand the types of relationship-level factors investigated, strengthen the measurement of relationship-level factors, include young sexual minority women in samples, and use longitudinal designs. Doing so will move the field toward development of empirically sound interventions for SMY that promote protective factors and improve sexual health.

Keywords: adolescence, protective factors, relationships, sexual health, sexual minority

Introduction

Sexual minority youth (i.e., adolescents/young adults who experience same-sex attraction, engage in same-sex sexual behavior, or identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual; SMY) experience elevated risk for adverse sexual health outcomes, including HIV,1 sexually transmitted infections (STIs),2 and unplanned pregnancies,3 compared to heterosexual peers, and may engage in more sexual risk behaviors than heterosexual youth.4 These disparities are attributed largely to risk factors associated with the social marginalization of SMY, specifically stigma, violence, and discrimination,4–6 and research with this population has focused traditionally on identifying how these risks drive sexual health disparities. However, literature about adolescent populations also emphasizes the importance of protective factors, which are characteristics, conditions, and behaviors that improve positive health outcomes for individuals or reduce the negative effects of risks or hazards on individual health.7–12 Identifying protective factors is critical, as they provide useful targets for developing health programs or interventions to improve outcomes.8 In the case of SMY, promoting protective factors may be particularly important given that an overemphasis on risk may reinforce stigma inadvertently by framing these youth as inherently risky.13

The broader literature on protective factors for adolescent sexual health highlights the importance of relationship-level factors. Relationship-level factors that promote sexual health can be conceptualized as attributes of specific types of relationships, such as family, peers, or romantic/sexual partners. For example, connection to and communication with parents,14–17 behavioral norms and strength of connection to peers,10,16 and communication with partners about safer sex18 have all been associated with positive adolescent sexual health outcomes. Identifying protective factors relevant to specific relationships has facilitated intervention development, such as parent-based interventions that increase parent–adolescent communication and reduce sexual risk.17

However, previous research has considered relationship-level protective factors specifically among SMY less frequently. The unique developmental experiences of SMY may have implications for their interpersonal relationships and how these relationships influence their sexual health. Adolescence is a time of rapid sexual development, during which SMY may become aware of same-sex attraction, engage in same-sex sexual activity, and adopt or disclose a sexual minority identity.19 These processes can affect the relationships of SMY. Family dynamics may be strained after youth disclose a sexual minority identity,20 and peers may bully youth with actual or perceived minority identities.4,21 These relationship dynamics may carry implications for whether relationship-level factors function for SMY in the same capacity as observed among adolescents broadly.

There is a clear need to understand relationship-level protective factors that benefit the sexual health of SMY. Previous work on protective factors and SMY indicates that this research may be limited9; however, systematically mapping the scope of empirical work in an emerging area of inquiry can enable future research to build on promising findings and address key gaps.22 Thus, we conducted a systematic mapping with two primary goals, as follows: (1) to identify empirically supported relationship-level protective factors that benefit sexual health for SMY and (2) to identify conceptual and methodological gaps in this evidence that warrant further research. We hope that these results will advance the development of an evidence base that informs interventions to improve the sexual health of SMY.

Methods

Conceptual framework

To provide an operational definition of relationship-level protective factors and structure the scope of our search, we first developed a list of types of relationships theoretically or empirically identified by scholars as influential to the sexual health of adolescents and young adults. These included family, romantic/sexual partners, peers, and trusted adults/medical providers. We then conducted a nonsystematic scan of the broader adolescent health literature (i.e., not focused on SMY) to identify the factors within each relationship type that were identified as protective for sexual health (Table 1). Due to our interest in intervention development, we only included factors that could be modified through programs (e.g., support and communication). Nonmodifiable factors such as parents’ marital status or the type of SMY’s romantic or sexual partner (i.e., main, casual, commercial, and so on) were excluded from the conceptual framework.

Table 1.

A Priori List of Theoretical/Empirical Relationship-Level Protective Factors

| Type of relationship | Family | Romantic/sexual partners | Peers | Trusted adults/medical providers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Examples of theorized protective characteristics of relationship types | Parenting style Parenting practices Parental/family behaviors Parental/family attitudes and values Opportunities or rewards/recognition for prosocial family involvement Family connectedness Parental/family acceptance of sexual identity Disclosure of sexual identity to family |

Partner beliefs and attitudes Partner support Partner communication Partner behaviors |

Peer connectedness Peer norms Prosocial peer involvement Peer support Peer behaviors Peer acceptance of sexual identity Peers who are LGB Disclosure of sexual identity to peers |

Presence/absence Relationship characteristics (duration, frequency of interaction, type of connection) Connectedness/attachment Social support Communication (frequency, quality) |

Systematic search

A systematic search of peer-reviewed observational research published in English-language journals between 1997 and 2015 then was conducted. Given that a systematic review is an analysis of preexisting documents and data sources, institutional review board review was not required for this search. Keywords from four domains (i.e., adolescence, sexual orientation, sexual health outcomes, and relationship types) were used to create the search strategy (Table 2). The search queried eight public health and social science databases (Table 2). In addition, we reviewed the reference lists of each included article manually to identify any further relevant articles.

Table 2.

Search Strategy

| Category | Search terms |

|---|---|

| Adolescence | adolescent or students or teen* or youth* or adolescen* or young or ymsm or ywsw or student* or high school* or middle school* or junior high or tween* or preteen* or pre-teen* |

| Sexual orientation | LGB* or lesbian* or gay or homosexual* or same-sex or MSM or men who have sex with men or women who have sex with women or WSW or sexual orientation or bisexual* or sexual minorit* |

| Sexual health outcomes | sex* health or reproductive health or sex* behav* or sex* risk* or same-sex behav* or sex* intercourse or anal sex or oral sex or safe sex or unsafe sex or pregnan* or sexual* transmit* or hiv or std* or sti* or human immunodeficiency virus or sexual* active* or sex* debut or sexual initiation or contracep* or condom* or birth control or partner violence or rape or sex* violen* or sex* abuse* or sex* assault |

| Relationship types | interpersonal relation* or famil* or parent* or filial or sibling* or sex* partner* or intimate partner* or romantic* or boyfriend* or girlfriend* or same-sex couple* or friend* or mentor* or school counselor* or teacher* or social network* or relational self or peer group* or peer* or brother* or sister* or father* or paternal or mother* or maternal or significant other* or school nurse* or health* provider* or social worker* or role model or doctor* or nurse* or counselo* or trusted adult* or patient-provider* or caregiver* |

| Databases used | MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, Sociological Abstracts, ERIC (Education Resources Information Center), ASSIA: Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, PsycARTICLES, Educational Journals |

Inclusion/exclusion criteria and screening process

The research team screened abstracts identified through the searches using a standard form. To be included, articles had to examine the association between a relationship-level factor previously conceptualized as protective for adolescent sexual health (Table 1) and at least one sexual health outcome (e.g., HIV, pregnancy, STIs, and related behaviors such as condom use) using significance testing. Because the World Health Organization identifies protective factors for adolescent sexual health as similar across geographical contexts, we did not limit articles by region.10 Protective factors that did not describe characteristics of a specific relationship type (e.g., generalized social support) were excluded. Articles had to report findings from a sexual minority sample or subsample (e.g., gay, lesbian, or bisexual, reporting same-sex attraction or behavior) and include youth (i.e., 10–24 years, overall mean age of 26 or below). Notably, to avoid conflating sexual orientation and gender identity, samples of gender minority youth (i.e., transgender and gender nonconforming youth) were not the focus of this review. Retrospective studies of adults older than 24 years were not included due to the potential for recall bias. Qualitative studies were excluded, given the lack of significance testing. All relevant articles identified through the abstract screening were subjected to full-text review to confirm eligibility. All articles that were unclear with respect to inclusion or exclusion were discussed among coders until consensus was reached.

Data extraction

A standard coding sheet was used to extract the following information from each included article: data source, study design, sampling strategy, sample characteristics, relationship-level protective factor(s), and sexual health outcomes. We itemized all associations tested between a relationship-level protective factor and a sexual health outcome for each article. Most articles reported multiple associations because they assessed multiple relationship-level factors or sexual health outcomes, stratified results by subgroup, or compared multiple categories/levels of a categorical/ordinal variable. In every case, we extracted all associations that fit inclusion criteria and classified each as protective, null, or risk, based on statistical significance (P < 0.05) and direction of association. When multivariate results were not available, we reported bivariate results. We considered findings protective if the presence or high level of a relationship-level factor was associated with a decrease in an adverse sexual health outcome or if the absence or low level of relationship-level factor was associated with an increase in an adverse sexual health outcome. Null findings were associations without statistical significance. Risk findings were associations operating in the opposite direction as protective relationships.

Data analysis

To summarize the current state of the science, we first grouped extracted associations between a relationship-level factor and a sexual health outcome by relationship type (i.e., family, romantic/sexual partners, peers, trusted adults, and medical providers). Then, within each relationship type, we organized associations according to the specific protective factor examined (e.g., parental acceptance, peer norms about safer sex) and then we counted the frequency of protective, null, and risk associations for each factor. We considered whether articles used cross-sectional or longitudinal data, as the latter provides better evidence for causality, and noted the data source, as articles reporting on the same data source might duplicate findings. Given our interest in comprehensively mapping emergent empirical work on relationship-level protective factors and SMY, we did not rate the quality of these articles.

Results

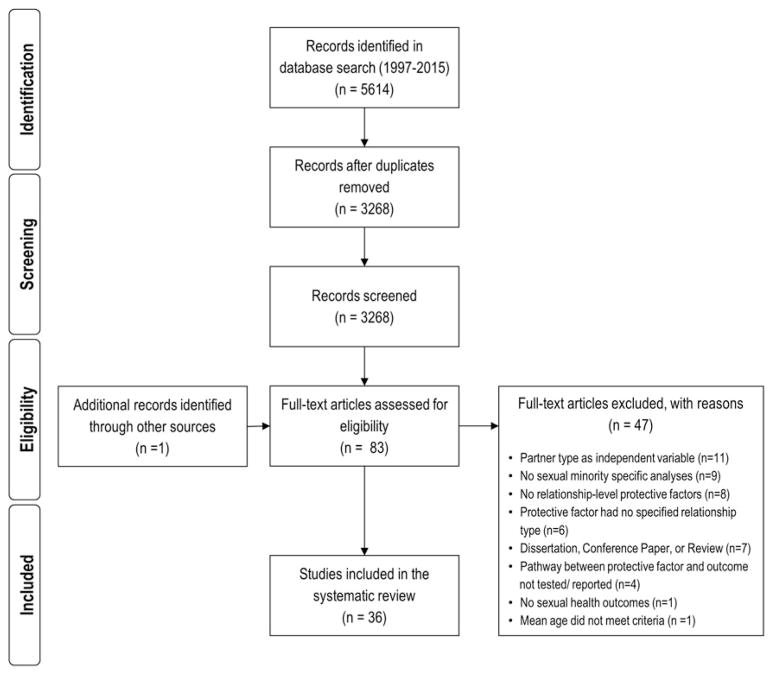

Our initial search of this literature identified 5614 articles. After removing 3186 duplicates, 3268 abstracts were screened, 82 articles identified for full text review, and 1 additional article identified through a manual search. Intercoder agreement on the abstract screening was 85.3%. After full-text review, 47 articles were excluded for not meeting inclusion criteria. A total of 36 articles reporting data from 27 data sources were included in the mapping (Fig. 1).23–58 Although the scope of the literature search included multiple relationship types, only two articles reported on youth’s relationships with trusted adults.25,35 We summarized characteristics of articles about trusted adults but excluded them from the synthesis of protective factors as our ability to draw inferences from two sources was limited.

FIG. 1.

Flow diagram for inclusion and exclusion of articles.

Study characteristics

The majority of articles reported on cross-sectional non-probability studies (n = 23; Table 3).23,25–27,33,35–38,40,41,43, 45–48,50–53,55,57,58 Six articles reported on the Community Intervention Trial for Youth (CITY) Study,24,29,31,39,44,54 a randomized, multisite control trial using venue-based time-space sampling; however, five of those six analyzed site- or race-specific subsamples.24,31,39,44,54 One article reported on a case–control study,28 two articles used longitudinal data,30,34 three reported cross-sectional findings from venue-based probability samples,42,49,56 and one reported on a multistage sample of households.32 Given that very few longitudinal or probability samples were included, we did not disaggregate findings by study design or sampling strategy. Of those articles sharing a data source, only two reported duplicative findings (i.e., results presented were equivalent predictors and outcomes from the same subsample of the original data source).24,31 These duplicative findings are only counted once in result summaries.

Table 3.

Study Characteristics for Articles Examining at Least One Relationship-Level Protective Factor and a Sexual Health Outcome Among Sexual Minority Youth

| Authors (date) | Data source, country | Study design | Sampling strategy | Sample characteristics (n, gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, age) | Type of relationship-level factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amirkhanian et al. (2006)23 | Original data, Russia | Cross-sectional | Nonprobability, venue-based |

n = 187 Male: 78.1%/n = 146; female: 21.9%/n = 41 Race/ethnicity not reported Of males: MSM: 95%/n = 139 Age: 22.1 |

Peers |

| Bakeman et al. (2007)24 | CITY Study, Atlanta, GA, United States | Cross-sectional (subsample from a randomized, multisite controlled trial) | Probability, venue-based, time-space sampling |

n = 849 Male: 100%/n = 849 Black: 100%/n = 849 Gay: 56%/n = 475.4; bisexual: 32%/n = 271.7; heterosexual: 1%/n = 8.5; undecided: 4%/n = 34.0; other: 8%/n = 67.9 Age: 18–25 |

Peers |

| Bird et al. (2012)25 | Project Q, Chicago, IL, United States | Cross-sectional | Nonprobability, community-based sampling |

n = 436 Male: 62%/n = 270.3; female: 29%/n = 126.4; transgender: 9%/n = 39.2 White: 34%/n = 148.2; Black: 28%/n = 122.1; Latino: 26%/n = 113.4 Gay/lesbian: 70%/n = 305.2; bisexual: 25%/n = 109; unsure/questioning: 2%/n = 8.7 Age: 20.0, 16–24 |

Trusted adults |

| Cohall et al. (2010)26 | Original data source, New York, NY, United States | Cross-sectional | Nonprobability, venue-based sampling |

n = 177 Male: 96%/n = 170; transgender: 4.0%/n = 7 Black: 64%/n = 112; Latino: 24.1%/n = 42; mixed race: 11.5%/n = 20 Gay: 59.5%/n = 103; bisexual: 26%/n = 45; down low: 3.5%/n = 6; straight: 5.2%/n = 9; other: 5.9%/n = 10 Age: 20.4 (2.15), 18–24 |

Romantic/sexual partners |

| Cook et al. (2015)27 | Adolescent Trials Network, United States | Cross-sectional | Nonprobability, clinical sample |

n = 991 Male: 94.5%/n = 936; transgender: 5.4%/n = 54 White: 14.2%/n = 140; Black: 63.6%/n = 628; Latino: 22.2%; n = 219; mixed race: 13.2%/n = 130; other: 9.0%/n = 89 Gay: 75.3%/n = 746; bisexual: 16.0%/n = 159; heterosexual: 4.5%/n = 45; other: 3.9%/n = 39 Age: 21.3 (2.0), 15–26 |

Peers; romantic/sexual partners; family |

| Dorell et al. (2011)28 | Original data, Jackson, MS, United States | Unmatched case–control | Nonprobability, cases = local HIV/AIDS reporting system; controls = venue-based sampling |

n = 125 Male: 100%/n = 125 Black: 100%/n = 125 Cases (N = 30): gay: 63%/n = 19; bisexual: 23%/n = 7; straight: 10%/n = 3; questioning: 3%/n = 1 Controls (n = 95): gay: 59%/n = 56; bisexual: 26%/n = 25; straight: 6%/n = 6; questioning: 4%/n = 4; none of these: 4%/n = 4 Age: cases: median 20.0, 16–25; controls: median 22, 16–25 |

Medical providers |

| Forney et al. (2012)29 | CITY, United States | Randomized+multisite control trial | Probability, venue-based time-space sampling |

n = 8235 Male: 100%/n = 8235 White: 22.4%/n = 1875; Black: 28.1%/n = 2351; Latino: 34.2%/n = 2867; other: 15.3%/n = 1282 Gay: 74.2%/n = 6211; bisexual: 19.9%/n = 1667; straight: 0.5%/n = 38; other: 5.4%/n = 459 Age: 21.5 (2.3), 15–25 |

Peers |

| Glick and Golden (2014)30 | Development and Sexual Health (DASH) study, Seattle WA, United States | Longitudinal, prospective | Nonprobability, peer, online (Facebook), and venue-based recruitment (college organizations, STI clinic) |

n = 94 Male: 100%, n = 94 White: 59.6%/n = 56; other— “Nonwhite race”: 40.4%/n = 38 Gay 84%/n = 79; other MSM (bisexual, queer, straight, and/or other): 16%/n = 15 Age: 21.0, 16–30 |

Peers; family |

| Hart et al. (2004)31 | CITY—Atlanta Sample, United States | Cross-sectional (subsample from a randomized, multisite controlled trial) | Probability, venue-based time-space sampling |

n = 758 Male: 100%/n = 758 Black: 100%/n = 758 Gay: 53.4%/n = 405; bisexual: 32.6%/n = 247; heterosexual: 0.8%/n = 5; other: 13.4%/n = 101 Age: 21.6 (2.1), 18–25 |

Peers |

| Hays et al. (1997a)32 | San Francisco Young Men’s Health Study—Wave 1, United States | Cross-sectional | Probability, multistage sample of households from the 21 census tracts in San Francisco with the highest cumulative number of AIDS cases in 1992 |

n = 372 Male: 100%/n = 372 White: 77%/n = 286.4; Black: 5%/n = 18.6; Latino: 8%/n = 29.8; Asian/Pacific Islander: 7%/n = 26.0; other: 4%/n = 14.9 Gay: 84%/n = 312.5; bisexual: 14%/n = 52.1; heterosexual: 2%/n = 7.4 Age: 25.8 (2.5), 18–29 |

Peers; romantic/sexual partners |

| Hays et al. (1997b)33 | Young Men’s Survey, Wave 2, United States | Cross-sectional (longitudinal survey, but these data are only from wave 2) | Nonprobability, venue-based sampling |

n = 416 Male: 100%/n = 416 White: 83%/n = 345.3; Black: 2%/n = 8.32; Latino: 6%/n = 25.0; Asian/Pacific Islander: 7%/n = 29.1; other: Native American: 2%/n = 8.3 Gay: 82%/n = 314.1; bisexual: 18%/n = 74.9 Age: 24.0 (2.7), 18–27 |

Romantic/sexual partners |

| Hightow-Weidman et al. (2013)34 | YMSM of Color Initiative, United States | Longitudinal | Nonprobability, different recruitment strategies in each of the eight cities |

n = 362 Male: 100%/n = 362 Black: 66.6%/n = 241; Latino: 21.5%/n = 78; mixed: 11.9%/n = 43 Gay: 63.8%/n = 231; bisexual: 19.9%/n = 72; other: 16.3%/n = 59 Age: 20.4 (1.9), 15–24 |

Romantic/sexual partners |

| Jones et al. (2008)35 | Original data, Raleigh, Greens-boro, and Charlotte, NC, United States | Cross-sectional | Nonprobability, venue-based sampling |

n = 308 Male: 100%/n = 308 Black: 100%/n = 308 Gay: 53.6%/n = 165.1; other “Nongay Identified” MSM: 46.4%/n = 142.39 Age: 23.0 (3.1), 18–30 |

Family; peers; trusted adults |

| Kelly et al. (2001)36 | Original data, Russia | Cross-sectional | Nonprobability, event-based recruitment |

n = 422 Male: 100%/n = 422 Race not reported MSM: 100%/n = 422; sexual identity not reported Age: with a history of exchanging sex for money or valuables: 23.8 (6.5), 18+; with no history of exchanging sex for money or valuables: 27.3 (7.7), 18+ |

Peers |

| Leonard et al. (2014)37 | Original data (baseline data from longitudinal study), Bronx, United States | Cross-sectional | Nonprobability, venue-based and snowball recruitment |

n = 80 Male: 100%/n = 80 Black: 39.5%/n = 31.6; Latino: 38.2%/n = 30.6; mixed race: 10.5%/n = 8.4; other: 11.8%/n = 9.4 Gay: 60.0%/n = 48; bisexual: 29.1%/n = 23.8; other: 11.4%/n = 9.1 Age: 19.0 (2.0), 16–21 |

Medical providers; romantic/sexual partners |

| Lorente et al. (2012)38 | Original data collected by Alternatives-Cameroun NGO, Cameroon | Cross-sectional | Nonprobability, snowball recruitment |

n = 165 Male: 100%/n = 165 Race not reported Check all that apply: gay: 40%/n = 66; bisexual: 50%/n = 82.5; other: 31%/n = 51.2 Age: median: 25, 18–44 |

Peers |

| Mashburn et al. (2004)39 | CITY—African American only samples (Atlanta, Birmingham, Chicago), United States | Cross-sectional (subsample from a randomized, multisite controlled trial) | Probability, venue-based time-space sampling |

n = 551 Male: 100%/n = 551 Black: 100%/n = 551 Gay: 47%/n = 259; bisexual: 42%/n = 231; straight: 1%/n = 6; other 11%/n = 61 Age: 21.4 (2.14), 16–25 |

Peers |

| Meanley et al. (2015)40 | Original data, Detroit, MI, United States | Cross-sectional observational | Nonprobability, web-based survey |

n = 304 Male: 100%/n = 304 White: 24.8%/n = 92; Black: 51.2%/n = 190; Hispanic/Latino: 14.8%/n = 55; other, not specified: 9.2%/n = 34 Gay: 85.2%/n = 259; bisexual: 8.6%/n = 26; other (e.g., same gender loving, queer): 6.3%/n = 19 Age: 22.9 (2.9), 18–29 |

Medical providers |

| Molitor et al. (1999)41 | Original data, City of Long Beach and the counties of Riverside, Sonoma, and Sacramento, CA, United States | Cross-sectional | Nonprobability, venue-based recruitment |

n = 834 Male: 100%/n = 834 White: 63.3%/n = 528; Black: 11.1%/n = 93; Latino: 15.8%/n = 132; API: 4.8%/n = 40; other: 5%, n = 42 MSM: 100%/n = 834; sexual identity not reported Age: 21.9 (2.4), 17–25 |

Peers; romantic/sexual partners |

| Mutchler et al. (2011)42 | Original data, Los Angeles, CA, New York, NY, United States | Cross-sectional | Probability, venue-based time-space sampling |

n = 416 Male: 100%/n = 416 Black: 40.1%/n = 167; Latino: 47.1%/n = 196; mixed race: 12.8%/n = 53 Gay: 74%/n = 308; bisexual: 22%/n = 92; other: 4%/n = 17 Age: 20.7, 18–24 |

Peers |

| Nyoni and Ross (2013)43 | Original data, Tanzania | Cross-sectional (baseline interview of longitudinal survey) | Nonprobability, respondent driven sampling |

n = 271 Male: 100%/n = 271 Race/ethnicity not reported MSM: 100%/n = 271; sexual identity not reported Age: 24.0 (6.2) |

Peers; romantic/sexual partners |

| O’Donnell et al. (2002)44 | CITY project— Hermanos Jóvenes, Latino sample in NYC, United States | Cross-sectional (subsample from a randomized, multisite controlled trial) | Probability, venue-based time-space sampling |

n = 465 Male: 100%/n = 465 Latino: 100%/n = 465 Gay: 74%/n = 341; bisexual: 22%/n = 102; other: 4%/n = 19 Age: 21.4 (2.4), 15–25 |

Peers; family |

| Peterson et al. (2009)45 | Original data, United States | Cross-sectional | Nonprobability, target sampling, referrals |

n = 158 Male: 100%/n = 158 Black: 100%/n = 158 MSM: 100%/n = 158; sexual identity not reported Age: 23.0, 19–29 |

Peers |

| Rhodes et al. (2003)46 | Original data, Birmingham, AL, United States | Cross-sectional | Nonprobability, venue-based (one bar) |

n = 107 Male: 100%/n = 107 Black: 100%/n = 107 MSM 100%; sexual identity not reported Age: 24.8 (6.0), 18–50 |

Medical providers |

| Ryan et al. (2009)47 | Family Acceptance Project, San Francisco Bay Area, United States | Cross-sectional | Nonprobability; venue-based sampling |

n = 224 Male: 51%/n = 114; female: 49%/n = 110 White: 48%/n = 107; Latino: 52%/n = 117 Gay: 42%/n = 94.1; lesbian: 28%/n = 62.7; bisexual: 13%/n = 29.1; other: 17%/n = 38.1 Age: 22.8, 21–25 |

Family |

| Ryan et al. (2010)48 | Family Acceptance Project, San Francisco Bay Area, United States | Cross-sectional | Nonprobability, venue-based sampling |

n = 224 Male: 51%/n = 114; female: 49%/n = 110 White: 48%/n = 107; Latino: 52%/n = 117 Gay: 42%/n = 94.1; lesbian: 28%/n = 62.7; bisexual: 13%/n = 29.1; other: 17%/n = 38.1 Age: 22.8, 21–25 |

Family |

| Scott et al. (2014)49 | Original data (baseline data from an intervention trial), TX, United States | Cross-sectional | Probability, venue-based, time location sampling (modeled after NHBS) |

n = 813 Male: 100%/n = 813 Black: 100%/n = 813 MSM: 100%/n = 813; sexual identity not reported Age: median: 23, 18–29 |

Peers |

| Shapiro and Vives (1999)50 | Original data, San Francisco, CA, United States | Cross-sectional | Nonprobability, community venue-based sampling |

n = 60 Male: 100%/n = 60 Asian: 100%/n = 60; Chinese: 31.7%; Filipino: 30.0%; other Asian: 38.3% MSM: 100%/n = 60; sexual identity not reported Age: 23.7, 18–39 |

Romantic/sexual partners |

| Shilo and Mor (2014)51 | Original data, Israel (also used in Shilo and Mor52) | Cross-sectional | Nonprobability, online recruitment (Facebook and other web groups) |

n = 952 Male: 53.4%/n = 508; female: 46.6%/n = 444 Race/ethnicity not reported Gay: 41%/n = 390; lesbian: 15%/n = 142; bisexual: 16%/n = 153; heterosexual: 28%/n = 267 Age: 22.1 (4.7), 12–30 |

Peers; family |

| Shilo and Mor (2015)52 | Original data, Israel (also used in Shilo and Mor51) | Cross-sectional | Nonprobability |

n = 445 Male: 100%/n = 445 Race/ethnicity not reported Gay: 87.6%/n = 390; bisexual: 8.8%/n = 39; questioning: 3.4%/n = 16 Age: 22.5 (4.7), 12–30 |

Peers; family |

| Siconolfi et al. (2013)53 | Project 18, New York City, NY, United States | Cross-sectional (baseline data of a longitudinal survey) | Nonprobability, venue-based, and online recruitment |

n = 590 Male: 100%/n = 590 White: 29.3%/n = 173; Black: 14.7%/n = 87; Hispanic/Latino: 38.3%/n = 226; Asian/Pacific Islander: 4.7%/n = 28; other: 12.9%/n = 76 Exclusively gay: 58.6%/n = 346; not exclusively gay: 41.4%/n = 244 Age: 18–29 |

Peers |

| Sumartojo et al. (2008)54 | CITY Study, baseline data, 13 sites (Atlanta; Birmingham; Chicago; Washington Heights/South Bronx; Jackson Heights; San Gabriel Valley; Orange County; Seattle; San Diego; Milwaukee; West Hollywood; Detroit; Minneapolis), United States | Cross-sectional (baseline data from a randomized, multisite controlled trial) | Probability, venue-based time-space sampling |

n = 2621 Male: 100%/n = 2621 Check all that apply: White: 25%/n = 653; Black: 29%/n = 762; Latino: 34%/n = 886; Asian/Pacific Islander: 13%/n = 329; other: 2%/n = 58 Gay: 67%/n = 1761; other MSM: 33%/n = 848 Age: median: 21, 15–25 |

Peers |

| Thoma and Huebner (2014)55 | Diverse Adolescents Sexual Health Philadelphia, Boston, Oakland, Indianapolis, United States | Cross-sectional | Nonprobability, venue-based sampling through local CBOs, community fliers, online recruitment, peer word of mouth |

n = 257 Male: 100%/n = 257 White: 22%/n = 56.5; Black: 35%/n = 90; mixed race: 30%/n = 77.1; other (including Latino, Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American): 13%/n = 33.4 Gay 67%/n = 172; bisexual 25%/n = 64.3; queer or other 8%/n = 20.6 Age: 17.4 (1.3), 14–19 |

Family |

| Waldo et al. (2000)56 | San Francisco Bay Area Young Men’s Survey II, San Francisco, CA, United States | Cross-sectional | Probability, venue-based time-space sampling |

n = 719 Male: 100%/n = 719 White: 30.7%/n = 221; Black: 18.9%/n = 136; Latino: 29.5%/n = 212; Asian/Pacific Islander: 16.3%/n = 117; other: 4.6%/n = 33 Gay: 63.3%/n = 455; bisexual: 36.0%/n = 259; heterosexual: 3.4%/n = 24 Age: 15–22 |

Peers |

| Xiao et al. (2013)57 | Original data, China | Cross-sectional | Nonprobability sample, multiple means (venue-based, peer outreach, snowballing, Internet outreach) |

n = 307 Male: 100%/n = 307 Han ethnicity: 92%/n = 282 Gay: 59.9%/n = 184; bisexual: 30.9%/n = 95; heterosexual: 1.3%/n = 4; uncertain: 7.8%/n = 24 Age: 23.7 (2.9), 18–29 |

Romantic/sexual partners |

| Xu et al. (2011)58 | Original data, China | Cross-sectional | Nonprobability |

n = 436 Male: 100%/n = 436 Han ethnicity: 88.5%/n = 386; non-Han 11.5%/n = 50 Homosexual: 57.8%/n = 252; bisexual: 35.6%/n = 155; heterosexual: 0.9%/n = 4; other, sexual orientation undetermined: 5.7%/n = 25 Age: under 20: 54.4%; over 20: 45.6% |

Family; medical providers |

Where exact n’s were not provided for sample characteristics, we estimated based on reported percentages and vice versa. Age is reported as mean (standard deviation), range; however, if any of this information was not included in an article it was omitted.

CBOs, community based organizations; CITY, Community Intervention Trial for Youth; NHBS, National HIV Behavioral Surveillance Systems; STI, sexually transmitted infection; YMSM, young men who have sex with men.

Twenty-eight articles reported on samples from the United States,24–35,37,39–42,44–50,53–56 and eight reported on international samples.23,36,38,43,51,52,57,58 Samples from the United States were racially diverse—24 articles had samples that were majority people of color.24–29,31,34,35,37,39,40,42,44–50,53–56 International studies did not report information on race/ethnicity typically with the exception of two articles from China that specified if participants were Han or non-Han ethnicity.57,58 Participant ages ranged from 12 to 44 years across all articles, with a mean age of 21.9 years across those articles that reported mean age (n =28).23,25–27,29–37,39–48,50–52,55,57 All samples included young sexual minority men (n =36),23–58 four included young sexual minority women,25,47,48,51 one included female friends of young sexual minority men as part of a network analysis,23 and three included transgender women under the umbrella of “men who have sex with men” (MSM).25–27 In order from most to least, 22 articles examined factors within peer relationships,23,24,27,29–32,35,36,38,39,41–45,49,51–54,56 10 with family relationships (primarily parents),27,30,35,44,47,48,51,52,55,58 10 within romantic/sexual relationships,26,27,32–34,37,41,43,50,57 and 5 within medical provider relationships.28,37,40,46,58 Results on protective factors are presented by number of unique associations, not by article or data source (Table 4).23,24,26–58

Table 4.

Theorized Relationship-Level Protective Factors and Their Associations with Sexual Health Outcomes

| Protective factor | Factor measure (as specified in articles) | Outcome | Type of association | Sexual minority population | Article | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer relationships | ||||||

| Peer norms about safer sex | Peer condom norms/peer norms regarding condom use | Unprotected insertive anal sex | Protective | African American MSM | Bakeman et al.24 | Protective: 16; null: 11; risk: 0 |

| Unprotected receptive anal sex | Protective | Hart et al.31 | ||||

| Peer condom norms | UAI with main partners | Protective | African American MSM | Bakeman et al.24 | ||

| UAI with casual partners | Protective | |||||

| Peer norms about condoms | Avoidance of UAI | Protective | HIV+ YMSM | Forney et al.29 | ||

| Avoidance of UAI | Protective | HIV − YMSM | ||||

| Peer norms about condoms | HIV testing | Null | Young African American MSM | Mashburn et al.39 | ||

| Peer norms about condom use | Ever having been tested for HIV | Null | YMSM | Sumartojo et al.54 | ||

| HIV testing in the last 3 months | Null | |||||

| Peer norms regarding condom use | UAI | Protective | Young African American MSM | Hart et al.31 | ||

| Peer norms regarding condom use—Strongly agree versus disagree/strongly disagree | Any UAI | Protective | Young Black MSM | Jones et al.35 | ||

| Any UIAI | Protective | |||||

| Any URAI | Protective | |||||

| Peer norms regarding condom use—Agree versus disagree/strongly disagree | Any UAI | Null | ||||

| Any UIAI | Null | |||||

| Any URAI | Null | |||||

| Perceived norms around condom use and safer sex | Exchange of sex for money or valuables | Null | MSM | Kelly et al.36 | ||

| Perceived condom norms | Sexual risk compositea—No risk versus high risk | Protective Null |

Young African American MSM | Peterson et al.45 | ||

| Sexual risk compositea—Low risk versus high risk | ||||||

| Safer sex peer norms | Number of sex partners (3 months) | Protective | YMSM in St. Petersburg and their social networks | Amirkhanian et al.23 | ||

| Having unprotected vaginal or anal intercourse (3 months) | Protective | |||||

| Number of unprotected vaginal or anal sex acts (3 months) | Protective | |||||

| Paid or received money for sex (1 year) | Protective | |||||

| Testing positive for an STD at baseline | Null | |||||

| Safer sex peer norms | UAI in past 6 months among participants age 15–17 | Protective | Young GB men | Waldo et al.56 | ||

| UAI in past 6 months among participants age 18–22 | Null | |||||

| Social support from friends for condoms | UAI | Null | YMSM in California | Molitor et al.41 | ||

| Social network characteristics | Social network: number of sex partners (3 months) | Number of sex partners (3 months) | Protective | YMSM in St. Petersburg and their social networks | Amirkhanian et al.23 | Protective: 5; null: 6; risk: 0 |

| Social network: having unprotected vaginal or anal intercourse (3 months) | Having unprotected vaginal or anal intercourse (3 months) | Protective | ||||

| Social network: testing positive for an STD at baseline | Testing positive for an STD at baseline | Protective | ||||

| Social network: paid or received money for sex (1 year) | Paid or received money for sex (1 year) | Protective | ||||

| Social network: number of unprotected vaginal or anal sex acts (3 months) | Number of unprotected vaginal or anal sex acts (3 months) | Null | ||||

| How many friends are gay or bisexual | UAI | Protective | Young HIV − GB men | Hays et al. (1997a)32 | ||

| UAI | Null | Young HIV+ GB men | ||||

| UAI | Null | Young untested GB men | ||||

| Friends sexual orientation— Mostly homosexual versus mostly heterosexual | Never having been tested for HIV | Null | MSM living in Douala, Cameroon | Lorente et al.38 | ||

| Friends sexual orientation— Mostly homosexual versus mixed homosexual and heterosexual | Never having been tested for HIV | Null | ||||

| Friends sexual orientation— Mostly homosexual versus does not know/has no friends | Never having been tested for HIV | Null | ||||

| Peer connectedness | Social isolation from friends (i.e., association interpreted as inverse of “connection to friends”) | Nonconcordant UAI in past 3 months | Protective | YMSM | Glick and Golden30 | Protective: 3; null: 2; risk: 0 |

| New HIV/STI diagnosis | Null | |||||

| Peer connectedness—A little connected versus not at all connected | Inconsistent condom use | Protective | African American, Latino, and multiracial YMSM in Los Angeles and New York | Mutchler et al.42 | ||

| Peer connectedness—Very connected versus not at all connected | Inconsistent condom use | Protective | ||||

| Peer connectedness— Somewhat connected versus not at all connected | Inconsistent condom use | Null | ||||

| Friends’ support | Social support from friends | Sexual risk behaviorsb | Risk | Young LGBs | Shilo and Mor51 | Protective: 1; null: 0; risk: 3 |

| Social support from friends | Internet use for seeking sex | Risk | Young GB men | Shilo and Mor52 | ||

| Sexual risk behaviorsb | Risk | |||||

| Support received from Black gay/bisexual male friends | Delayed HIV testing | Protective | Young Black MSM | Scott et al.49 | ||

| Communication with peers | Communication about safer sex—told a friend about protecting self | UAI | Null | Young Black MSM | Jones et al.35 | Protective: 1; null: 8; risk: 0 |

| UIAI | Null | |||||

| URAI | Null | |||||

| Communication about safer sex—friend told participant about protecting self | UAI | Null | ||||

| UIAI | Null | |||||

| URAI | Null | |||||

| Disclosure of HIV+ serostatus status to friend/other person | UAI | Null | HIV+ YMSM (includes transgender women) | Cook et al.27 | ||

| UAI with serodiscordant partner | Null | |||||

| Discussing condoms with friends | Condom use during last intercourse with a casual partner | Protective | Urban Tanzanian MSM | Nyoni and Ross43 | ||

| Disclosure | Peer knowledge of MSM behavior | UAI | Null | Urban Latino YMSM | O’Donnell et al.44 | Protective: 0; null: 4; risk: 0 |

| UAI at last sex with main partner | Null | |||||

| UAI at last sex with nonmain partner | Null | |||||

| Proportion of friends who knew of same-sex sexual behavior | Sexual health screening in the last 6 months for YMSM | Null | Young gay, bisexual, and other MSM | Siconolfi et al.53 | ||

| Family relationships | ||||||

| Support | General relationship quality compositec | UAI in past 6 months | Null | YMSM | Thoma and Huebner55 | Protective:1; null: 12; risk: 0 |

| Maternal support: when first came out | Nonconcordant UAI in past 3 months | Null | YMSM | Glick and Golden30 | ||

| New HIV/STI diagnosis | Null | |||||

| Maternal support: current | Nonconcordant UAI in past 3 months | Null | ||||

| New HIV/STI diagnosis | Protective | |||||

| Paternal support: when first came out | Nonconcordant UAI in past 3 months | Null | ||||

| New HIV/STI diagnosis | Null | |||||

| Paternal support: current | Nonconcordant UAI in past 3 months | Null | ||||

| New HIV/STI diagnosis | Null | |||||

| Social support from family | Sexual risk compositeb | Null | Young LGBs | Shilo and Mor51 | ||

| Social support from family | Internet use for seeking sex partners | Null | Young GB men | Shilo and Mor52 | ||

| UAI in past 6 months | Null | |||||

| Sexual risk compositeb | Null | |||||

| Disclosure | Disclosure of HIV-positive serostatus status to a family member | UAI | Protective | HIV+ YMSM (includes transgender women) | Cook et al.27 | Protective: 2; null: 7; risk: 1 |

| Ever came out to a mother or mother figure | Nonconcordant UAI in past 3 months | Null | YMSM | Glick and Golden30 | ||

| New HIV/STI diagnosis | Null | |||||

| Ever came out to a father or father figure | Nonconcordant UAI in past 3 months | Risk | ||||

| New HIV/STI diagnosis | Null | |||||

| Outness to cohabitating parents | UAI in past 6 months | Null | YMSM | Thoma and Huebner55 | ||

| Parental knowledge of MSM behavior | UAI | Null | Urban Latino YMSM | O’Donnell et al.44 | ||

| UAI with main partner | Null | |||||

| UAI with nonmain partner | Null | |||||

| Sexual orientation known by family members | HIV status | Protective | MSM in NE China | Xu et al.58 | ||

| Acceptance | Family acceptance | UAI or UVI in past 6 months with casual partner or a steady partner who was nonmonogamous or serodiscordant for HIV | Null | LGBT adolescents | Ryan et al.48 | Protective: 1; null: 9; risk: 0 |

| Family expressed disapproval of sex with men (i.e., association interpreted as inverse of “family approval”) | UAI | Null | Young Black MSM | Jones et al.35 | ||

| UAI with main partner | Null | |||||

| UAI with nonmain partner | Null | |||||

| Family rejection (i.e., association interpreted as lack of family rejection)— Low family acceptance versus high family acceptance | UAI with casual partner in past 6 months | Protective | White and Latino LGB young adults | Ryan et al.47 | ||

| UAI with casual partner at last intercourse | Null | |||||

| STD diagnosis | Null | |||||

| Family rejection (i.e., association interpreted as lack of family rejection)— Low family acceptance versus medium family acceptance | UAI with casual partner in past 6 months | Null | ||||

| UAI with casual partner at last intercourse | Null | |||||

| STD diagnosis | Null | |||||

| Connectedness | Social isolation from family (i.e., association interpreted as inverse of “connection to family”) | Nonconcordant UAI in past 3 months | Protective | YMSM | Glick and Golden30 | Protective: 1; null: 1; risk: 0 |

| New HIV/STI diagnosis | Null | |||||

| Communication | Sexual communication scaled | UAI in past 6 months | Risk | YMSM | Thoma and Huebner55 | Protective: 0; null: 0; risk: 1 |

| Monitoring | Parental monitoring | UAI in past 6 months | Null | YMSM | Thoma and Huebner55 | Protective: 0; null: 1; risk: 0 |

| Romantic/Sexual partners | ||||||

| Communication about safer sex with partners | Asking partner to disclose their HIV status | Condom use at last intercourse with casual partner | Protective | Urban Tanzanian MSM | Nyoni and Ross43 | Protective: 12; null: 21; risk: 0 |

| Disclosed HIV status to sex partners/boyfriends | Condom use during oral sex within last 3 months | Protective | HIV+ MSM | Hightow-Weidman et al.34 | ||

| Condom use during insertive anal intercourse within last 3 months | Protective | |||||

| Condom use during receptive anal intercourse within last 3 months | Protective | |||||

| Disclosure of HIV-positive serostatus to a sex partner/romantic partner | UAI in last 3 months | Null | HIV+ YMSM (study includes transgender women) | Cook et al.27 | ||

| UAI with serodiscordant partner | Null | |||||

| Ever asked by a partner about HIV testing | History of HIV testing | Protective | Young men of color who have sex with men (study includes transgender women) | Cohall et al.26 | ||

| Ever asked partner about partner’s HIV test | History of HIV testing | Protective | ||||

| New partner asked for HIV testing | Frequency of testing | Null (P < .10) | Urban YMSM of color | Leonard et al.37 | ||

| Sexual communication about condom use with casual partners | Lifetime consistent condom use during oral or anal sex with regular partner | Null | Chinese MSM in Beijing | Xiao et al.57 | ||

| Consistent condom use with regular partner in last three episodes of oral or anal sex | Null | |||||

| Lifetime consistent condom use during oral or anal sex with casual partner | Null | |||||

| Consistent condom use with casual partner in last three episodes of oral or anal sex | Null | |||||

| Sexual communication about condom use with regular partners | Lifetime consistent condom use during oral or anal sex with regular partner | Protective | ||||

| Consistent condom use with regular partner in last three episodes of oral or anal sex | Protective | |||||

| Lifetime consistent condom use during oral or anal sex with casual partner | Null | |||||

| Consistent condom use with casual partner in last three episodes of oral or anal sex | Null | |||||

| Sexual communication about HIV/STDs with casual partners | Lifetime consistent condom use during oral or anal sex with regular partner | Null | ||||

| Consistent condom use with regular partner in last three episodes of oral or anal sex | Null | |||||

| Lifetime consistent condom use during oral or anal sex with casual partner | Null | |||||

| Consistent condom use with casual partner in last three episodes of oral or anal sex | Null | |||||

| Sexual communication about HIV/STDs with regular partners | Lifetime consistent condom use during oral or anal sex with regular partner | Protective | ||||

| Consistent condom use with regular partner in last three episodes of oral or anal sex | Protective | |||||

| Lifetime consistent condom use during oral or anal sex with casual partner | Null | |||||

| Consistent condom use with casual partner in last three episodes of oral or anal sex | Null | |||||

| Sexual communication about sexual history with casual partners | Lifetime consistent condom use during oral or anal sex with regular partner | Null | ||||

| Consistent condom use with regular partner in last three episodes of oral or anal sex | Null | |||||

| Lifetime consistent condom use during oral or anal sex with casual partner | Null | |||||

| Consistent condom use with casual partner in last three episodes of oral or anal sex | Null | |||||

| Sexual communication about sexual history with regular partners | Lifetime consistent condom use during oral or anal sex with regular partner | Protective | ||||

| Consistent condom use with regular partner in last three episodes of oral or anal sex | Protective | |||||

| Lifetime consistent condom use during oral or anal sex with casual partner | Null | |||||

| Consistent condom use with casual partner in last three episodes of oral or anal sex | Null | |||||

| Quality of communication with partners | Feel embarrassed or find it difficult discussing condom use with sexual partners | Condom use at last intercourse with casual partner | Protective | Urban Tanzanian MSM | Nyoni and Ross43 | Protective: 2; null: 5; risk: 0 |

| Safer sex communication (i.e., comfort with) | Sexual risk compositee | Null | Asian MSM | Shapiro and Vives50 | ||

| Safer sex communication scalef | UAI within last 6 months | Protective | YMSM in California | Molitor et al.41 | ||

| Sexual communication skills | UAI | Null (P < .10) | Young GB men (HIV+) | Hays et al. (1997a)32 | ||

| UAI | Null (P < .10) | Young GB men (HIV−) | ||||

| UAI | Null (P < .10) | Young GB men (untested) | ||||

| Sexual communication skills | UAI with a boyfriend | Null (P < .10) | Young gay men in a boyfriend relationship | Hays et al. (1997b)33 | ||

| Medical providers | ||||||

| Communication with medical providers | Counselor or other professional suggested (HIV testing) | HIV testing—High frequency versus low frequency | Null | Urban YMSM of color | Leonard et al.37 | Protective: 4; null: 3; risk: 0 |

| Offered as part of my regular medical care | HIV testing—High frequency versus low frequency | Null (P > .1) | ||||

| Healthcare provider communication | Hepatitis A vaccination | Protective | African American MSM | Rhodes et al.46 | ||

| No advice on HIV or STD prevention or testing (association interpreted as inverse of received advice) | HIV+ | Protective | African American MSM | Dorell et al.28 | ||

| Sexual identity disclosed to health provider (yes, disclosed) | HIV+ | Protective | ||||

| Provider prevention discussions | No testing/HIV testing/HIV and STD testing | Protective | YMSM | Meanley et al.40 | ||

| Source of HIV/AIDS knowledge—clinical doctors | HIV infection | Null | MSM in NE China | Xu et al.58 | ||

| Quality of communication with medical providers | Provider comfort | No testing/HIV testing/HIV and STD testing | Null | YMSM | Meanley et al.40 | Protective: 0; null: 1; risk: 0 |

Number of times participants had anal sex as a top and as a bottom in last 3 months and how often a condom was used for both behaviors.

UAI, use of drugs and alcohol before or during sex.

Maternal and paternal warmth, support, and attachment.

Composite of issues discussed with parents such as HIV/AIDS, condoms, choosing partners.

Multiple/anonymous partners, inconsistent condom use, no HIV test, unprotected alcohol-related sex.

Perceived efficacy and experience with communication with partners.

GB, gay or bisexual; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LGB, lesbian, gay, or bisexual; STD, sexually transmitted disease; UAI, unprotected anal intercourse; UIAI, unprotected insertive anal intercourse; URAI, unprotected receptive anal intercourse. UVI, unprotected vaginal intercourse.

Peer relationships

As seen in Table 4, the specific factors considered in articles examining peer relationships included peer norms about safer sex (16 protective associations, 11 null), characteristics of social network members (5 protective, 6 null), peer connectedness (3 protective, 2 null), friends’ support (1 protective, 3 risk), communication with peers (1 protective, 8 null), and disclosure (4 null). The vast majority of these associations examined condom use during anal or vaginal sex as the sexual health outcome (30 associations).

Associations with peer norms about safer sex were primarily protective. Perceiving that peers used condoms or engaged in safer sex was associated 14 times with a reduced likelihood that young sexual minority men engaged in condomless anal or vaginal sex23,24,29,31,45,56 and null 6 times.35,41,45,56 One protective association was also found between safer sex peer norms and fewer sex partners for young men who have sex with men (YMSM).23,36 One of two associations between peer norms about condom use and transactional sex was protective; the other was null.23 Peer norms about condoms also had three null associations with HIV testing39,54 and one null association with sexually transmitted disease (STD) diagnosis.23

Social network characteristics had mixed results. In one analysis of Russian YMSM, YMSM’s behaviors were associated with their peer network’s behaviors with respect to number of sex partners, unprotected vaginal or anal intercourse in the last 3 months, testing positive for an STD, and paying or receiving money for sex in the past year.23 These four associations were protective in that if YMSM’s network connections engaged in fewer of these behaviors, YMSM were less likely to report the behaviors themselves. Frequency of unprotected vaginal or anal sex acts of YMSM’s social networks was unassociated with their own frequency of unprotected vaginal or anal sex acts. In a separate analysis in San Francisco, HIV-negative young gay and bisexual men who had more friends who were gay or bisexual also reported less unprotected anal intercourse (UAI); however, this association was null for HIV-positive and untested participants.32 An analysis from Cameroon found the proportion of friends who were homosexual to be unrelated to HIV testing (three null associations).38

Results for peer connectedness were mixed. A longitudinal analysis by Glick and Golden30 found reductions in isolation from friends, which was interpreted as increasing connection to friends, to be associated with a reduced likelihood of engaging in UAI with a nonconcordant partner in the past 3 months, but unassociated with new HIV/STI diagnoses. Meanwhile, Mutchler et al.42 looked at levels of peer connectedness among young MSM and generally found that men who were more connected to peers reported more consistent condom use than those who were less connected (two protective associations, one null).

Friends’ support had more risk than protective associations. Social support from friends was associated with increased sexual risk behaviors among a sample of LGB youth,51 and a follow-up analysis with only the young gay and bisexual men from that sample found that friends’ support was associated with more use of the Internet to find sex partners and more sexual risk behaviors.52 Alternatively, Scott et al.49 found that support from friends was associated with not delaying HIV testing for young Black men who have sex with men (YBMSM).

Communication with peers yielded largely null results. Among Tanzanian YMSM, discussing condoms with friends was associated with more frequent condom use during last intercourse with a casual partner.43 Jones et al.35 examined if YBMSM told friends about protecting themselves and if friends told YBMSM about their self-protection and found both to be unrelated to UAI across six associations. Disclosure of HIV-positive serostatus to a friend by YMSM was not associated with UAI generally and UAI with a serodiscordant partner.27

Analyses of disclosure of identity or same-sex behavior to peers yielded null results. The proportion of YMSM’s friends who knew they engaged in same-sex behavior was not associated with UAI in general or during last sex with main or nonmain partners (three associations),44 nor was it associated with having had a sexual health medical screening in the last 6 months.53

Family relationships

Articles examining the characteristics of parent/family relationships focused on factors of support (1 protective association, 12 null), disclosure (2 protective, 7 null, 1 risk), acceptance (1 protective, 9 null), connectedness (1 protective, 1 null), communication (1 risk), and monitoring (1 null). The majority of these associations examined condom use during anal or vaginal sex as the sexual health outcome (26 associations).

Findings about family support were mostly null. Only one protective association was reported: YMSM with current maternal support had lower odds of having a positive HIV/STI test; however, current maternal support was not associated with UAI.30 Previous maternal support, current paternal support, and previous paternal support each had null relationships with HIV/STI testing and UAI.30 Social support from family was also not associated with sexual risk among LGB youth in Israel51 and, among only the gay and bisexual men in that sample, it was not associated with UAI, using drugs or alcohol before sex, and using the Internet to find sex partners.52 A composite measure of family relationship quality was also not associated with UAI.55

Results for disclosure included protective, risk, and null associations, but were majority null. A family member’s knowledge of youth’s sexual orientation was protectively associated with HIV status,58 and disclosure of HIV-positive serostatus to a family member was protectively associated with UAI among HIV-positive YMSM.27 Coming out to one’s father had a risk relationship to nonconcordant UAI in the past 3 months, but no relationship to HIV/STI test results; coming out to one’s mother was not associated with UAI or HIV/STI test results.30 Four other associations between parental knowledge of MSM behavior or “outness to parents” and UAI were null.44,55

Generally, family acceptance or family rejection was unrelated to condomless intercourse. Although Ryan et al.47 found that compared to those with high levels of rejection from their families, LGB youth with low levels were less likely to have UAI with a casual partner in the past 6 months; three other associations between levels of parental rejection and UAI were null. In a separate analysis, Ryan et al.48 studied family acceptance, measured differently from family rejection, and found no association with UAI or unprotected vaginal intercourse in the past 6 months with a casual partner or a partner who was nonmonogamous or serodiscordant for HIV. Family disapproval of same-sex behavior, interpreted as the inverse of family approval of same-sex behavior, was not associated with three UAI outcomes among YBMSM.35 In addition, high and medium levels of family rejection were not associated with an STD diagnosis for LGB young adults.47

Social isolation from family, interpreted as a lack of family connectedness, was protectively associated with nonconcordant UAI in the past 3 months for YMSM, but had a null association with testing positive for HIV/STI.30 Parental communication had one risk relationship: increased communication with parents about the topics of waiting to have sex, using condoms, choosing partners, and HIV/STD testing was associated with more UAI in the past 6 months among gay, bisexual, and queer young men in 4 U.S. cities.55 One null association was found between parental monitoring and UAI in the past 6 months.55

Partner relationships

Articles examined two factors theorized to be protective within sexual or romantic partnerships—communicating about safer sex (12 protective associations, 21 null) and quality of communication (2 protective, 5 null). The vast majority of these associations examined condom use during oral or anal sex as the sexual health outcome (37 associations).

Communication with sexual and romantic partners had mixed findings. Examinations of YMSM who discussed HIV testing or status with romantic and sexual partners found mostly protective associations between these conversations with two outcomes: condom use during oral and anal sex (4 protective associations, 2 null)27,34,43 and HIV testing (2 protective associations, 1 null).26,37 One analysis from China distinguished both the topic of communication (i.e., condom use, HIV/STDs, and sexual history) and whether the communication occurred with casual or regular partners and found different effects of sexual communication occurring with casual partners versus with regular partners.57 Communication with casual partners regardless of topic was not associated with use of condoms across 12 associations. Communication with regular partners across all three topics was associated with increased condom use with those regular partners (six associations), but communication with regular partners was not associated with condom use with casual partners (six associations).

In examinations of dimensions of communication quality, confidence communicating with a sexual/romantic partner among YMSM was mostly unassociated with condomless anal sex, with one protective association41 and four null associations.32,33 Results about comfort communicating about sex were mixed: one association with condom use at last sex with a casual partner was protective,43 yet another association with a composite sexual risk measure was null.50

Medical provider relationships

Articles examined two provider-related factors theorized to be protective for adolescent sexual health—communication (four protective associations, three null) and quality of communication (one null). Most analyses examined HIV testing or status as the outcome of interest (six associations).

Results for provider communication, which included various types of provider conversations, were mixed. Having prevention discussions with a provider had a protective relationship with HIV testing once,40 while being offered an HIV test by a counselor or as part of routine care were both unassociated with frequency of HIV testing.37 Both receiving advice from a provider about HIV/STD and coming out to a provider were protectively associated with HIV status,28 while getting knowledge about HIV/AIDS from a medical provider was not associated with HIV infection.58 General healthcare provider communication was associated with having received the hepatitis A vaccine once.46 Comfort with provider (a dimension of communication quality) had no association with HIV testing.40

Discussion

We identified 36 articles from 27 data sources evaluating the characteristics of peer, family, romantic/sexual partner, or medical provider relationships in relation to SMY’s sexual health.23–58 The majority of articles focused on relationships with peers, and few identified notable patterns within peer, partner, and medical provider relationships. The results point to key methodological issues in terms of the range of factors and outcomes tested, inclusivity of samples, measurement of relationship-level factors, and study design.

For peer relationships, positive peer norms about condom use/safer sex were protective for condom use. This finding echoes research on peers shaping behavioral norms among adolescents broadly.59,60 The quality of peer relationships for SMY had more mixed associations with sexual health. Connectedness with peers was related to a reduction in sexual risk taking in some cases30,42; yet social support from peers was related to an increase in sexual risk taking in others.51,52 These mixed findings may indicate that the quality of SMY’s friendships is not a robust indicator of their sexual health behaviors, particularly in comparison to influential factors such as peer norms.

Although most associations between family factors and sexual health were null, family factors have been found to be influential in improving the mental well-being of SMY.61,62 Given that positive mental health has been connected to less sexual risk taking among young gay and bisexual men,63 the possibility remains that family characteristics may be an important antecedent to the sexual health of SMY, but potentially difficult to observe in cross-sectional studies. Contrary to trends in the adolescent heath literature,64 direct parental communication about sex55 and coming out to one’s father30 were associated with increases in unprotected sex for YMSM. Notably, these analyses assessed if these conversations had taken place, but did not explore the quality or context of the interactions, thus potentially missing influential characteristics of conversations between parents and SMY. Conversations with parents who approve of SMY may be protective for sexual health, while conversations with disapproving parents may be related to health risks.

Regarding romantic/sexual partner relationship protective factors, communication about safer sex topics was protective with regular partners or when the partner type was unspecified, but universally null with casual partners. This finding may speak to the effectiveness of communication as a safer sex strategy when done with a partner with whom SMY are comfortable or have a preestablished rapport. This hypothesis is reinforced by those articles that examined the quality of safer sex conversations. Those analyses found that a greater comfort and confidence with discussing sexual health topics with a romantic or sexual partner had some association to more condom use.41,43 In tandem, these findings suggest that SMY’s skills in and comfort with broaching sexual health conversations with romantic and sexual partners may be essential to reducing sexual risk.

For articles focused on SMY and medical provider relationships, communication was protective for HIV testing and HIV status. However, simply receiving information about HIV or a recommendation for services as routine care was unrelated to HIV testing and status. These findings echo the crucial role that interactive conversations with medical providers play in the effective delivery of sexual health services to adolescent girls65,66—perhaps providers have a similar role to play in counseling YMSM in need of HIV testing or preventive care. One possible barrier to these conversations occurring with YMSM may be provider discomfort with discussing sexual orientation with their patients.67 Connecting medical providers with professional development on the topics of sexual identity, sexual attraction, and sexual behaviors may enhance their ability to discuss sexual orientation effectively with SMY.68 Such awareness may better facilitate comfort of YMSM patients67 and potentially improve health seeking behaviors such as HIV testing in this population.68 As part of the ongoing discussion about increasing competency among medical providers to address sexual orientation,68,69 additional measures of communication quality in research on sexual health outcomes among SMY seeking sexual health services may be warranted.

This systematic mapping also revealed many conceptual and methodological gaps in research on SMY, relationship-level protective factors, and sexual health. First, the breadth of the articles included was limited. Some key relationship types remain unexplored, and the range of factors examined within each type was narrow. Investigating the role of other interpersonal relationships that may benefit adolescents (e.g., expanding inquiry on trusted adults70,71 to look at teachers, coaches, or LGB adults) or including more work on factors well supported in literature on heterosexual adolescents (e.g., parental monitoring72 and romantic partner’s attitudes about condoms73) would do much to advance this field. In addition, the majority of articles looked at condom use or HIV testing as sexual health outcomes of interest. Other outcomes relevant to SMY such as STI testing/diagnosis2 and pregnancy3 should be considered.

Second, included articles focused overwhelmingly on young sexual minority men. With the exception of four articles,25,47,48,51 young sexual minority women were largely overlooked, thus making it difficult to draw conclusions about effectiveness of relationship-level factors for their sexual health. Given the disparate rates of pregnancy experienced by young lesbian women3 and the elevated rates of STIs experienced by young bisexual women,2 research on protective factors and their relationship to sexual health outcomes for young sexual minority women is needed.

Third, articles were limited by the approach to measurement of relationship-level factors. With one notable exception,23 articles tested individual-level perceptions of relationships, rather than using dyadic or social network analysis of relationship effects. For example, articles on peer norms used measures of subjective peer norms rather than assessing behavioral characteristics of a network of youth and performing a social network analysis of peer behaviors. Recently, a growing number of scholars are seeking out these alternate methodological structures as a more comprehensive means of assessing how relationships relate to individual behavior and health.74,75 Work with SMY may benefit from these methods to understand the complex interpersonal dynamics playing a role in sexual health.

Finally, similar to other reviews of protective factors among SMY, the articles included in this study were primarily cross-sectional in design and had relatively small sample sizes.9 Longitudinal research is needed to ascertain causality between relationship-level protective factors and sexual health outcomes, and replication of some of these null results within larger samples may find them to be protective when adequately powered.

Study limitations

This systematic mapping has some limitations. First, our population of interest for this review was SMY, defined in terms of sexual orientation, thus we did not explicitly discuss transgender and gender nonconforming youth. The unique health issues and the role of protective factors in the lives of gender minority youth merit their own investigation.76 Second, although relationship-level factors are critical to the sexual health of adolescents,10,11 they do not represent the entire social ecology of protective factors which may benefit SMY. Individual-level protective factors for this population have been mapped elsewhere,9 but continued efforts are needed to research and synthesize the evidence on community- and societal-level protective factors for the sexual health of SMY. Third, while we included articles from international samples, the community and societal contexts of these international studies may not be equivalent to U.S. studies; however, the presence of these articles may bolster the breadth of our findings. For example, relationship-level factors such as friendship and positive parenting skills appear to improve adolescent sexual health regardless of youths’ country of origin.10 Fourth, we focused the mapping on quantitative evidence as a starting point; however, examinations of qualitative studies of relationship-level protective factors may provide additional insight about how these factors uniquely operate for SMY. Finally, our intention was to map the existing evidence base of relationship-level protective factors for sexual health among SMY systematically. Because our inclusion criteria were purposefully broad in service of this objective, we did not synthesize the results of a single research question, as done in a traditional systematic review.

Conclusion

Our results affirm that this literature is in its early stages, but they also provide potential direction for programs and research on relationship-level protective factors and SMY health. Two relationship-level factors emerged as promising: peer norms about condom use and communication with regular romantic partners. Interventions that normalize condom use/safer sex behaviors among SMY’s peers or that build SMY’s capacity to converse about safer sex with regular romantic/sexual partners may be effective. A number of other relationship-level factors yielded mixed results in relation to the sexual health of SMY, highlighting the need for continued research to build a more robust evidence base for program development. Future work should expand the types of relationship-level factors studied, strengthen the measurement of factors, include young sexual minority women, and use longitudinal designs. Doing so will move the field toward development of empirically sound interventions for SMY that promote protective factors and improve sexual health.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Arcus Foundation awarded to the CDC Foundation. The authors thank Lisa Barrios for her contributions to the conceptualization of this project.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A version of these findings was presented at the 2016 American Psychological Association Annual Convention, Denver, Colorado, August 4–7, 2016.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report: Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2014. Atlanta, GA: Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mojola SA, Everett B. STD and HIV risk factors among U.S. young adults: Variations by gender, race, ethnicity and sexual orientation. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;44:125–133. doi: 10.1363/4412512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saewyc EM. Adolescent pregnancy among lesbian, gay, and bisexual teens. In: Cherry AL, Dillon ME, editors. International Handbook of Adolescent Pregnancy: Medical, Psychosocial, and Public Health Responses. New York: Springer Science+Business Media; 2014. pp. 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kann L, Olsen EO, McManus T, et al. Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-related behaviors among students in grades 9–12—United States and selected sites, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65:1–202. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6509a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaza S, Kann L, Barrios LC. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents: Population estimate and prevalence of health behaviors. JAMA. 2016;316:2355–2356. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer IH, Frost DM. Minority stress and the health of sexual minorities. In: Patterson CJ, D’Augelli AR, editors. Handbook of Psychology and Sexual Orientation. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 252–266. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resnick MD. Resilience and protective factors in the lives of adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27:1–2. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fergus S, Zimmerman MA. Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:399–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armstrong HL, Steiner RJ, Jayne PE, Beltran O. Individual-level protective factors for sexual health outcomes among sexual minority youth: A systematic review of the literature. Sex Health. 2016;13:311–327. doi: 10.1071/SH15200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blum RW, Mmari KN. Report of Risk and Protective Factors Affecting Adolescent Reproductive Health in Developing Countries: An Analysis of Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Literature from Around the World. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ivankovich MB, Fenton KA, Douglas JM., Jr Considerations for national public health leadership in advancing sexual health. Public Health Rep. 2013;128(Suppl 1):102–110. doi: 10.1177/00333549131282S112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bearinger LH, Sieving RE, Ferguson J, Sharma V. Global perspectives on the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents: Patterns, prevention, and potential. Lancet. 2007;369:1220–1231. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60367-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dwyer A. “We’re not like these weird feather boa-covered AIDS-spreading monsters”: How LGBT young people and service providers think riskiness informs LGBT youth–police interactions. Crit Criminol. 2014;22:65–79. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the national longitudinal study on adolescent health. JAMA. 1997;278:823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vesely SK, Wyatt VH, Oman RF, et al. The potential protective effects of youth assets from adolescent sexual risk behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34:356–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markham CM, Lormand D, Gloppen KM, et al. Connectedness as a predictor of sexual and reproductive health outcomes for youth. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(3 Suppl):S23–S41. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutton MY, Lasswell SM, Lanier Y, Miller KS. Impact of parent-child communication interventions on sex behaviors and cognitive outcomes for Black/African-American and Hispanic/Latino youth: A systematic review, 1988–2012. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54:369–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirby D. Antecedents of adolescent initiation of sex, contraceptive use, and pregnancy. Am J Health Behav. 2002;26:473–485. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.26.6.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diamond LM, Savin-Williams RC. Adolescent sexuality. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2009. pp. 479–523. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmerman L, Darnell DA, Rhew IC, et al. Resilience in community: A social ecological development model for young adult sexual minority women. Am J Community Psychol. 2015;55:179–190. doi: 10.1007/s10464-015-9702-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Malley Olsen E, Kann L, Vivolo-Kantor A, et al. School violence and bullying among sexual minority high school students, 2009–2011. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55:432–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26:91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amirkhanian YA, Kelly JA, Kirsanova AV, et al. HIV risk behaviour patterns, predictors, and sexually transmitted disease prevalence in the social networks of young men who have sex with men in St Petersburg, Russia. Int J STD AIDS. 2006;17:50–56. doi: 10.1258/095646206775220504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bakeman R, Peterson JL Community Intervention Trial for Youth Study Team. Do beliefs about HIV treatments affect peer norms and risky sexual behaviour among African-American men who have sex with men? Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18:105–108. doi: 10.1258/095646207779949637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bird JD, Kuhns L, Garofalo R. The impact of role models on health outcomes for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohall A, Dini S, Nye A, et al. HIV testing preferences among young men of color who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1961–1966. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook SH, Valera P, Wilson PA, et al. HIV status disclosure, depressive symptoms, and sexual risk behavior among HIV-positive young men who have sex with men. J Behav Med. 2015;38:507–517. doi: 10.1007/s10865-015-9624-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dorell CG, Sutton MY, Oster AM, et al. Missed opportunities for HIV testing in health care settings among young African American men who have sex with men: Implications for the HIV epidemic. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25:657–664. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]