Abstract

Background:

Self-care is a valuable strategy to improve health and reduce events of hospitalization and the duration of hospital stay in elderly diabetic patients. This study aimed to examine the model of self-care behaviors in elderly diabetic patients.

Materials and Methods:

A survey was conducted among 209 diabetic elderly patients who were admitted in three hospitals affiliated with the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Iran. Convenience sampling method was used to recruit the participants. Depression, anxiety, stress, and perceived social support were considered as predicting exogenous variables and elderly patients' self-care activities were treated as endogenous variables. The data were collected by a four-part questionnaire consisting of demographic and health-related characteristics; 21-item depression anxiety stress scale, multidimensional scale of perceived social support, and Diabetes Self-care Activities scale. Structural equation modelling by Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16 and Analysis of Moment Structures-7 (AMOS) software was applied for data analysis.

Results:

Mean (standard deviation) of depression, anxiety, stress, perceived social support, and self-care activities of participants were 14.29 (4.3), 13.62 (3.74), 16.83 (4.23), 57.33 (14.19), and 44.56 (13.77), respectively. The results showed that the overall model fitted the data (χ2/df = 3.8, goodness-of-fit index (GFI) = 0.52, incremental fit index (IFI) = 0.48, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.14). Three out of four variables (i.e., perceived social support, anxiety, and depression) significantly predicted adherence to self-care behaviors among diabetic elderly patients (p < 0.05).

Conclusions:

The perceived social support, anxiety, and depression were identified as key constructs which need to be taken into account and well managed by health care professionals to enhance adherence to self-care activities in diabetic elderly patients.

Keywords: Aged, diabetes, self-care

Introduction

Elderly population is increasing worldwide.[1] Such a rapid growth in elderly population has challenged health care systems, particularly in Iran,[2] to meet the complexities of caring for such a vulnerable population who are at risk of various health problems and disabilities.[3]

Evidences show that currently diabetes is one of the chronic and disabling diseases that is seriously threatening the health of elderly population worldwide[4] and Iran is not an exception.[5] Diabetes in elderly is associated with poor health outcomes that lead to frequent hospitalizations,[6] which puts elderly at serious health risks such as irreversible decline of physical and cognitive function,[7] leading to increasing hospital costs, decreasing efficacy of clinical care, and other adverse consequences.[8]

Enhancing self-care activities (SCA) is now identified as a valuable strategy to meet health care needs and improve health as well as reduce events of hospitalization of diabetic elderly patients.[9,10] Despite emphasizing the importance of self-care in elderly patients, some studies have reported the self-care status in elderly patients as poor.[11,12,13] Hence, some researchers began to study the determinants of self-care, particularly in the elderly population. It is emphasized that ability to perform self-care varies according to many social determinants and health conditions.[12] While most studies have recently focused on the role of psychological and social determinants of self-care in diabetic patients[14,15] or elderly patients,[16,17] their possible contribution among the diabetic elderly patients, particularly in Iranian population, have been poorly investigated. It is essential to consider the interplaying roles of psychological and social factors as an integrated model of psychosocial factors, which fits the nature of such a complex phenomenon as psychosocial determinants of self-care in diabetic elderly patients. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the model of psychosocial determinants of self-care in diabetic elderly patients hospitalized in selected hospitals affiliated with the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted among 209 diabetic patients aged 60 years and more who were admitted in three hospitals affiliated with the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Iran from April to August 2016.

The sample size was estimated using the Power Analysis and Sample Size software program ((PASS), Utah, USA. Dattalo[18] suggested this method to be an appropriate method of power analysis and calculating sample size. Type I error probability and statistical power were considered to be 0.05 and 0.8, respectively. The effect size coefficient was considered to be 0.2 to get the maximum number of sample. Number of independent variables was considered as 4 (i.e., depression, anxiety, stress, and perceived social support). In total, data from 209 participants were analyzed.

Convenient sampling method was used to recruit the participants, such that according to the total number of diabetic elderly diabetics hospitalized in each center during the study period, the share of each center was identified and then the participants were sampled conveniently.

Data was collected by a trained person using a four-part questionnaire consisting of (a) demographic and health related characteristics, (b) 21-item Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21), (c) Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), and (d) The Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities (SDSCA) questionnaire. The DASS-21, which is a standard scale,[19] contains 21 items or phrases to measure individuals' depression, anxiety, and stress on a four-point Likert's scale (never, few, sometimes, and always) with scores of 0 to 3 and a total range of 0–21. The MSPSS contains 12 items on a seven-point Likert's scale (from 1 indicating completely disagree to 7 indicating completely agree) with a total score of 12–84; higher scores indicate better social support. The SDSCA questionnaire[20] is a validated 12-item self-report recall measure of adherence over the past 7 days to certain important aspects of the diabetes self-care regimen. The participants mark how many of the past 7 days they have adhered to each of the behaviors listed on the scale. Mean scores are calculated for each self-care behavior, and a total adherence score can be obtained by summing the mean subscale scores.

Internal consistency of the Persian version of the DASS-21[21] and MSPSS (Cronbach's alpha = 0.89)[22] has already been supported. The internal consistency of the SDSCA questionnaire has also been supported in an Iranian study (Cronbach's alpha = 0.68).[23]

After obtaining ethical and official permission, the participants were interviewed in the hospitals and were acquainted with the research objectives. Subsequently, the researcher distributed the questionnaires, and the participants filled the questionnaires personally and/or by the researcher (in the case of any problem with filling).

In addition to descriptive statistics (percentiles, mean, and standard deviation) and other analysis to examine the relationship between demographic/health related characteristics variables, our key analysis was structural equation modelling (SEM)[24] to examine the model of SCA in diabetic elderly patients based on psychosocial variables (i.e., depression, anxiety, stress, perceived social support, and self-care behaviors). Before SEM analysis, data were checked to ensure that it meets the key assumptions of the analysis. For each of the predicting variables, the normality assumption of the variables was satisfied such that almost all values of skewness and kurtosis were within Plus-Minus 2, indicating an acceptable range of values.[25] The version 16 of the SPSS and AMOS-7 software (SPSS, AMOS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all analyses, and all analyses were two-tailed.

Ethical considerations

The ethical considerations were met. Participants signed an informed consent. Moreover, their privacy, confidentiality, and volunteer participation were ensured.

Results

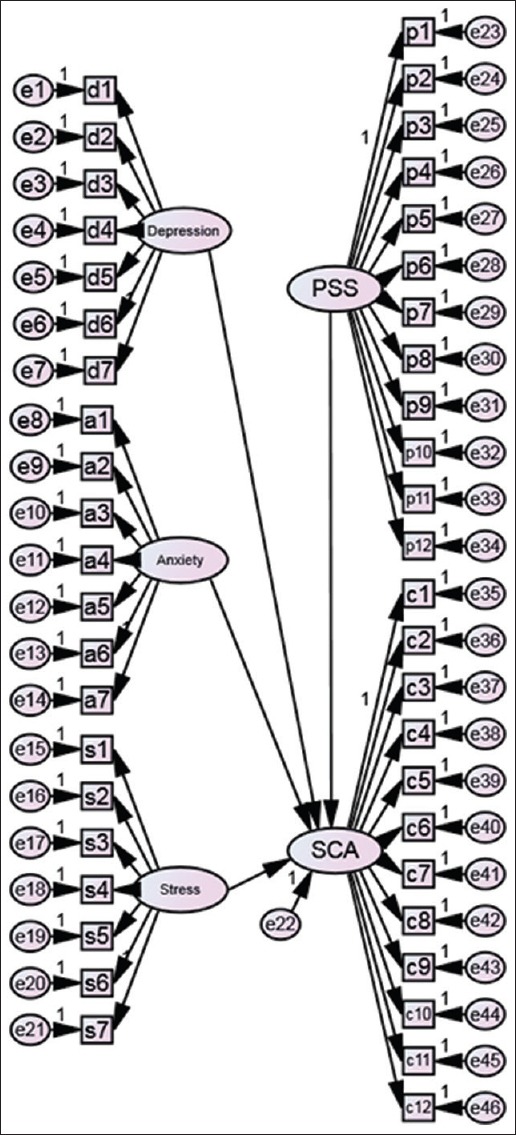

The descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. The analysis initially began by the hypothesized model [Figure 1]. However, 6 items (i.e., 4 items measuring anxiety, 1 item measuring stress, and 1 item measuring SCA) were further dropped because of insignificant regression weights (less than 3). The hypothesized model was constructed from five constructs of depression, anxiety, stress, perceived social support, and self-care behaviors, each of which were measured by 7, 7, 7, 12 and 12 items, respectively.

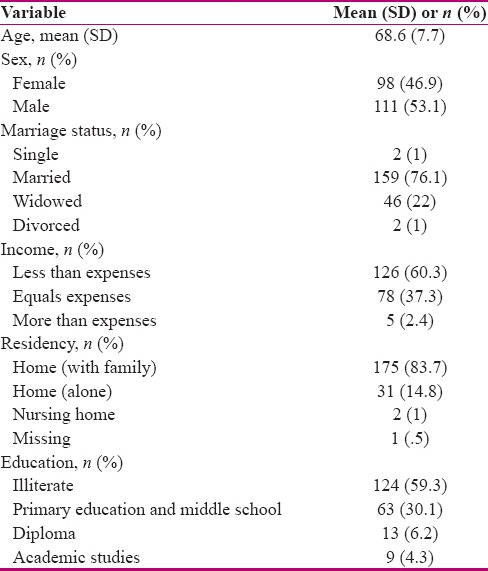

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study subjects

Figure 1.

Hypothesized structural model of predicting diabetic elderly patients' SCA based on four psychosocial factors. Note. The PSS is perceived social support and SCA is self-care behaviours

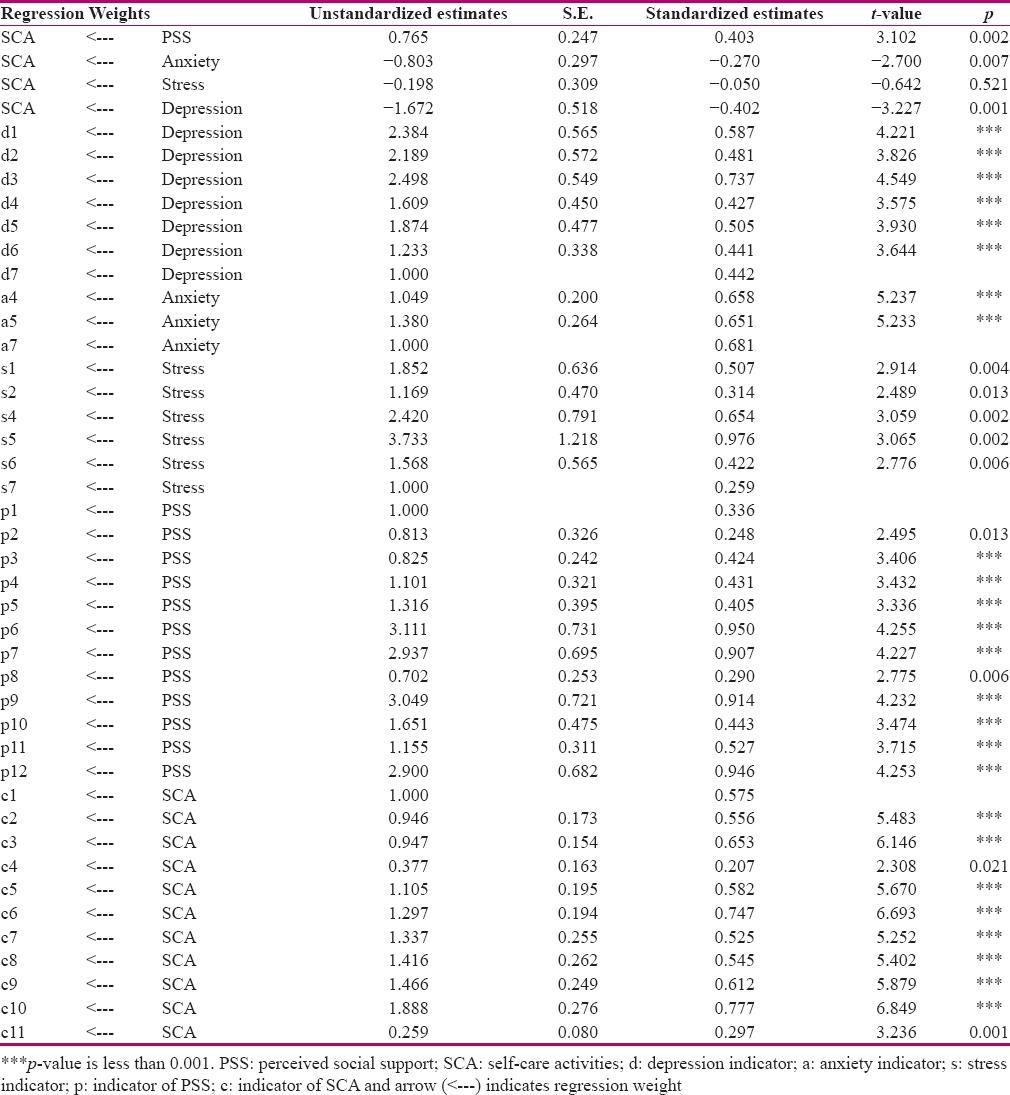

The results of the SEM showed that 3 out of 4 exogenous predicting variables (i.e., perceived social support, anxiety, and depression) had significant regression weights on the endogenous, predicted variable, SCA indicating that they significantly predicted the SCA of diabetic elderly patients [Table 2]. As can be seen in Table 2, all indicators have t-values more than 2, indicating significant and acceptable regression weights of the respective items.[26]

Table 2.

Unstandardized and Standardized estimates as well as p-values of the association between items and factors

Moreover, the proportion of Chi-square to degree of freedom (df) showed that the structural model has an acceptable fit with the data (χ2/df = 3.8 <5). However, indices have not significantly supported such a fitness (GFI = 0.52, IFI = 0.48, and RMSEA = 0.14).

Discussion

The present study aimed to evaluate the model of psychosocial determinants of SCA in diabetic elderly patients hospitalized in Isfahan. The results showed that three out of four latent variables (i.e., perceived social support, anxiety, and depression) significantly predicted adhering to the self-care behaviors.

The findings highlighted the role of perceived social support to predict SCA in diabetic elderly patients. Such a finding is in line with findings from some other similar studies.[12,15] However, it is inconsistent with that reported by Hackworth et al.[27] who found that social support and engagement in community activities was not influential on diabetes self-care. Miller and DiMatteo[28] pointed out that the exact mechanism by which social support affects treatment adherence and SCA is not yet completely understood.

The findings also supported significant predicting role of anxiety and depression in SCA of diabetic elderly patients. Higher scores of anxiety and depression were associated with low scores in self-care behaviors. This finding is in line with the study reported by Mut-Vitcu et al.[29] It is revealed that positive psychological health may sustain long-term coping efforts, and thus, facilitate diabetes self-management behaviors.[30] The role of psychological factors is of significant importance in Iranian elderly population who has been shown to have low happiness.[31]

A notable finding was the insignificant role of stress in predicting SCA of the diabetic elderly patients in this study. This finding was not in line with the findings of Albright et al.[15] who found that personal stress were strongly associated with self-care in in adults with type 2 diabetes. Future studies are recommended to clarify the role of stress in SCA of the elderly patients.

Some studies have shown significant role of self-care education in elderly patients' SCA[32] and some others have supported the effect of training program on depression, anxiety, and stress in older adults.[33] Therefore, it would be worthwhile to suggest similar programs to decrease depression, anxiety, and stress and to improve SCA in diabetic elderly patients.

Despite the strong association between three out of four predicting variables of the structural model, borderline values of the indices suggested adding a caution about the overall fit of the model.

Conclusion

In conclusion, perceived social support, anxiety, and depression were identified as key constructs which need to be taken into account and well managed by health care professionals to enhance adherence to SCA in diabetic elderly patients. Further studies to imperially test the effect of each of these factors on diabetic elderly health condition are recommended.

Financial support and sponsorship

Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank all participants of the study and the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for financial as well as scientific support. The study was approved and supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran (NO: 194263).

References

- 1.Christensen K, Doblhammer G, Rau R, Vaupel JW. Ageing populations: The challenges ahead. Lancet (London, England) 2009;374:1196–208. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61460-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Molavi R, Alavi M, Keshvari M. Relationship between general health of older health service users and their self-esteem in Isfahan in 2014. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2015;20:717–22. doi: 10.4103/1735-9066.170009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahmoodi A, Alavi M, Mosavi N. The relationship between self-care behaviors and HbA1c in diabetic patients. Scientific Journal of Hamadan Nursing & Midwifery Faculty. 2012;20:20–30. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization: Global report on diabetes. 2016. [Last cited on 2016 Sep 10]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/204871/1/9789241565257_eng.pdf .

- 5.Haghdoost AA, Rezazadeh-Kermani M, Sadghirad B, Baradaran HR. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the Islamic Republic of Iran: Systematic review and meta-analysis. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15:591–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Comino EJ, Harris MF, Islam MD, Tran DT, Jalaludin B, Jorm L, et al. Impact of diabetes on hospital admission and length of stay among a general population aged 45 year or more: A record linkage study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:12. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0666-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nobili A, Licata G, Salerno F, Pasina L, Tettamanti M, Franchi C, et al. Polypharmacy, length of hospital stay, and in-hospital mortality among elderly patients in internal medicine wards. The REPOSI study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67:507–19. doi: 10.1007/s00228-010-0977-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sicras-Mainar A, Navarro-Artieda R, Morano R, Ruiz L. Use of healthcare resources and costs associated to the start of treatment with injectable drugs in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus? Endocrinol Nutr. 2016;63:527–35. doi: 10.1016/j.endonu.2016.07.001. PMID: 27744013 DOI: 10.1016/j.endonu.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suhl E, Bonsignore P. Diabetes self-management education for older adults: General principles and practical application. Diabetes Spectrum. 2006;19:234–40. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinger K, Beverly EA, Smaldone A. Diabetes self-care and the older adult. West J Nurs Res. 2014;36:1272–98. doi: 10.1177/0193945914521696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raziyeh A, Simin J, Abdolail S. Self-care behaviors in older people with diabetes referred to Ahvaz Golestan Diabetes Clinic. Jundishapur Journal of Chronic Disease Care. 2012;2:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borhaninejad V, Tahami AN, Yousefzadeh G, Shati M, Iranpour A, Fadayevatan R. Predictors of Self-care among the Elderly with Diabetes Type 2: Using Social Cognitive Theory. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2016.08.017. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pavlou MP, Lachs MS. Self-neglect in Older Adults: A Primer for Clinicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1841–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0717-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song Y, Song HJ, Han HR, Park SY, Nam S, Kim MT. Unmet needs for social support and effects on diabetes self-care activities in Korean Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Edu. 2012;38:77–85. doi: 10.1177/0145721711432456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albright TL, Parchman M, Burge SK. Predictors of self-care behavior in adults with type 2 diabetes: An RRNeST study. Fam Med. 2001;33:354–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang AK, Lee EJ. Factors affecting self-care in elderly patients with hypertension in Korea. Int J Nurs Pract. 2015;21:584–91. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamrani AA, Foroughan M, Taraghi Z, Yazdani J, Kaldi AR, Ghanei N, et al. Self care behaviors among elderly with chronic heart failure and related factors. Pak J Biol Sci. 2014;17:1161. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2014.1161.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dattalo P. Determining Sample Size: Balancing Power, Precision, and Practicality. USA: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2005;44:227–39. doi: 10.1348/014466505X29657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toobert DJ, Glasgow RE. Assessing diabetes self-management: The summary of diabetes self-care activities questionnaire. Handbook of psychology and diabetes: A guide to psychological measurement in diabetes research and practice. 1994:351–75. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazloom Z, Ekramzadeh M, Hejazi N. Efficacy of supplementary vitamins C and E on anxiety, depression and stress in type 2 diabetic patients: A randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pak J Biol Sci. 2013;16:1597–600. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2013.1597.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chenari R, Norozi A. R T. The relationship between perceived social support with health promotion behaviors in veterans of Ilam, 2012-2013. Iran J War Public Health. 2013:21. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morowatisharifabad MA, Mahmoodabad SS, Baghianimoghadam MH, Tonekaboni N. Relationships between locus of control and adherence to diabetes regimen in a sample of Iranians. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2010;30:27–32. doi: 10.4103/0973-3930.60009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alavi M. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) in Health Sciences Education Researches: An Overview of the Method and Its Application. Iranian Journal of Medical Education. 2013;13:519–30. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim HY. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor Dent Endod. 2013;38:52–4. doi: 10.5395/rde.2013.38.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suhr DD. Exploratory or confirmatory factor analysis? SAS Institute Cary. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hackworth NJ, Hamilton VE, Moore SM, Northam EA, Bucalo Z, Cameron FJ. Predictors of Diabetes Self-care, Metabolic Control, and Mental Health in Youth with Type 1 Diabetes. Australian Psychologis. 2013;48:360–9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller TA, Dimatteo MR. Importance of family/social support and impact on adherence to diabetic therapy. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2013;6:421–6. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S36368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mut-Vitcu G, Timar B, Timar R, Oancea C, Citu IC. Depression influences the quality of diabetes-related self-management activities in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study. Clin Interv Agin. 2016;11:471–9. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S104083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chew B-H, Shariff-Ghazali S, Fernandez A. Psychological aspects of diabetes care: Effecting behavioral change in patients. World J Diabetes. 2014;5:796–808. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v5.i6.796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farajzadeh M, Ghanei Gheshlagh R, Sayehmiri K. Health Related Quality of Life in Iranian Elderly Citizens: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2017;5:100–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rabie T, Klopper HC. Guidelines to facilitate self-care among older persons in South Africa. Health SA Gesondheid. 2015;20:33–44. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghazavi Z, Feshangchi S, Alavi M, Keshvari M. Effect of a Family-Oriented Communication Skills Training Program on Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in Older Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2016;5:e28550. doi: 10.17795/nmsjournal28550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]