Abstract

Background

For many years, low back pain has been both the leading cause of days lost from work and the leading indication for medical rehabilitation. The goal of the German Disease Management Guideline (NDMG) on non-specific low back pain is to improve the treatment of patients with this condition.

Methods

The current update of the NDMG on non-specific low back pain is based on articles retrieved by a systematic search of the literature for systematic reviews. Its recommendations for diagnosis and treatment were developed by a collaborative effort of 29 scientific medical societies and organizations and approved in a formal consensus process.

Results

If the history and physical examination do not arouse any suspicion of a dangerous underlying cause, no further diagnostic evaluation is indicated for the time being. Passive, reactive measures should be taken only in combination with activating measures, or not at all. When drugs are used for symptomatic treatment, patients should be treated with the most suitable drug in the lowest possible dose and for as short a time as possible.

Conclusion

A physician should be in charge of the overall care process. The patient should be kept well informed over the entire course of his or her illness and should be encouraged to adopt a healthful lifestyle, including regular physical exercise.

For many years, low back pain has been both the leading cause of days lost from work and the leading indication for medical rehabilitation (1, 2). Musculoskeletal diseases have been second only to mental disorders in recent years as a cause of early retirement due to loss of the ability to work (3). In 2010, 26% of all adults participating in the mandatory nationwide health insurance system in Germany sought medical help at least once because of low back pain (4). The new update of the German Disease management Guideline (NDMG) on non-specific low back pain (5) contains many new elements. Among other things, psychosocial and workplace-related factors are given more emphasis, multiple imaging procedures are discouraged, and early multidisciplinary assessment is recommended. Moreover, both the guideline’s positive recommendations, such as those for less intensive diagnostic evaluation and for exercise rather than bed rest, and its negative recommendations, such as the recommendation against passive measures, are now supported by high-level evidence and confirmed by the guideline group.

Method

The following instruments were used in the creation of the NDMG:

The concepts of the Guidelines International Network (G-I-N),

the guideline criteria of the German Medical Association (Bundesärztekammer, BÄK) and the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians (Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung, KBV) (6),

the guideline regulations of the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften, AWMF) (e1), and

the German Guideline Evaluation Instrument (Deutsches Leitlinienbewertungsinstrument, DELBI) (e2).

The essentials of the guideline-creating procedure are described in the methods report (e3), and specific details are described in the guideline report (e4). The current version of the NDMG on non-specific back pain was developed from March 2015 to March 2017 by a multidisciplinary guideline group (ebox 1). It was then organized by the German Association for Quality Assurance in Medicine (Ärztliches Zentrum für Qualität in der Medizin, ÄZQ). All of the participants’ conflicts of interest have been documented and made public, as stipulated by the AWMF (e4).

eBOX 1. Sponsoring societies and authors of the NDMG on non-specific low back pain (2nd edition).

-

Sponsoring societies

German Medical Association (Bundesärztekammer, BÄK), Working Group of the German Medical Associations (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Deutschen Ärztekammern)

National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians (Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung, KBV)

Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften, AWMF)

-

and

Medicines Committee of the German Medical Association (Arzneimittelkommission der deutschen Ärzteschaft, AkdÄ)

German Psychotherapy Association (Bundespsychotherapeutenkammer, BPtK)

German Association of Independent Physical Therapists (Bundesverband selbstständiger Physiotherapeuten e. V., IFK)

German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin e. V., DEGAM)

German Society for Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Anästhesiologie und Intensivmedizin S. V., DGAI)

German Society for Occupational and Environmental Medicine (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Arbeitsmedizin und Umweltmedizin e. V., DGAUM)

German Surgical Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Chirurgie e. V., DGCh)

German Society for Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für experimentelle und klinische Pharmakologie und Toxikologie e. V., DGPT)

German Society for Internal Medicine (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Innere Medizin e. V., DGIM)

German Society for Manual Medicine (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Manuelle Medizin e. V., DGMM)

German Society for Neurosurgery (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurochirurgie e. V., DGNC)

German Society for Neurology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie e. V., DGN)

German Society for Neurorehabilitation (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurorehabilitation e. V., DGNR)

German Society for Orthopedics and Orthopedic Surgery (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Orthopädie und Orthopädische Chirurgie e. V., DGOOC)

German Society for Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Physikalische Medizin und Rehabilitation e. V., DGPMR)

German Soceity for Psychology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychologie e. V., DGPs) Deutsche Gesellschaft für psychologische Schmerztherapie und -forschung e. V. (DGPSF)

German Society for Psychosomatic Medicine and Medical Psychotherapy (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychosomatische Medizin und Ärztliche Psychotherapie e. V., DGPM)

German Society for Rehabilitation Science (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Rehabilitationswissenschaften e. V., DGRW)

German Society for Rheumatology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Rheumatologie e. V., DGRh)

German Society for Trauma Surgery (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Unfallchirurgie e. V., DGU)

German Radiological Society (Deutsche Röntgengesellschaft e. V., DRG)

German Pain Society (Deutsche Schmerzgesellschaft e. V., DGSS)

German Bekhterev‘s Disease Association (Deutsche Vereinigung Morbus Bechterew e. V., DVMB)

German Spine Society (Deutsche Wirbelsäulengesellschaft e. V., DWG)

German Association of Ergotherapists (Deutscher Verband der Ergotherapeuten e. V., DVE)

German Physiotherapy Association (Deutscher Verband für Physiotherapie e. V., ZVK)

German Network for Evidence-Based Medicine (Deutsches Netzwerk Evidenzbasierte Medizin e. V., DNEbM)

Society for Phytotherapy (Gesellschaft für Phytotherapie e. V., GPT)

-

Authors of the 2nd edition

Prof. Dr. Heike Rittner

Prof. Dr. Monika Hasenbring

Dr. Tina Wessels

Patrick Heldmann

Prof. Dr. Jean-François Chenot, MPH

Prof. Dr. Annette Becker, MPH

Dr. Bernhard Arnold

Dr. Erika Schulte

Prof. Dr. Elke Ochsmann

PD Dr. Stephan Weiler

Prof. Dr. Werner Siegmund

Prof. Dr. Elisabeth Märker-Hermann

Prof. Dr. Martin Rudwaleit

Dr. Hermann Locher

Prof. Dr. Kirsten Schmieder

Prof. Dr. Uwe Max Mauer

Prof. Dr. Dr. Thomas R. Tölle

Prof. Dr. Till Sprenger

Dr. Wilfried Schupp

Prof. Dr. Thomas Mokrusch

Prof. Dr. Bernd Kladny

Dr. Fritjof Bock

Dr. Andreas Korge

Dr. Andreas Winkelmann

Dr. Max Emanuel Liebl

PD Dr. Dipl.-Psych. Regine Klinger

Prof. Dr. Dipl.-Psych. Michael Hüppe

Prof. Dr. Dipl.-Psych. Michael Pfingsten

Dr. Dipl.-Psych. Anke Diezemann

Prof. Dr. Volker Köllner

Dr. Beate Gruner

Prof. Dr. Bernhard Greitemann

Dr. Silke Brüggemann, MSC

Prof. Dr. Thomas Blattert

Dr. Matti Scholz

Prof. Dr. Karl-Friedrich Kreitner

Prof. Dr. Marc Regier

Prof. Dr. Hans-Raimund Casser

Prof. Dr. Frank Petzke

Ludwig Hammel

Manfred Stemmer

Prof. Dr. Tobias Schulte

Patience Higman

Heike Fuhr

Eckhardt Böhle

Reina Tholen, MPH

Dr. Dagmar Lühmann

Prof. Dr. Jost Langhorst

Dr. Petra Klose

-

Methodological support and coordination

Dr. Monika Nothacker, MPH (AWMF)

Dr. Christine Kanowski, Dr. Susanne Schorr, Corinna Schaefer,

Dr. Dr. Christoph Menzel, Peggy Prien, Isabell Vader, MPH (ÄZQ)

Evidence base

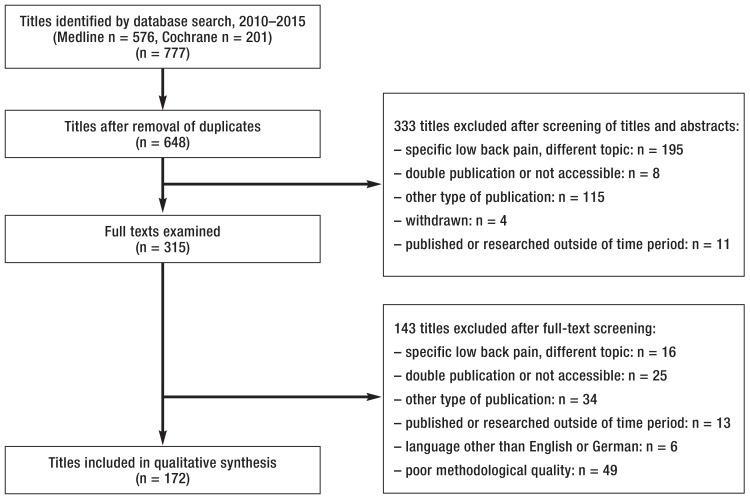

For this update, a systematic search was carried out in Medline (via PubMed) and the Cochrane database for aggregated evidence regarding non-specific low back pain (etable 1). In a two-step procedure, the retrieved articles were examined and their key questions and recommendations were classified, extracted, and evaluated (efigure 1) (e4). On some issues, such as the use of opioids to treat acute, non-specific back pain, supplementary searches for primary studies were carried out. Moreover, the S3 guideline on the long-term use of opioids to treat non-cancer pain (LONTS) (7) was used as a reference guideline.

eTable 1. Literature search for aggregated evidence on non-specific low back pain.

| Medline searching strategy (www.pubmed.org) (20 April 2015) | |||

| No. | Query | Hits | |

| #3 | Search (#1 OR #2) Filters: Systematic Reviews; Publication date from 2006/01/01; English; German | 873 | |

| #2 | Search (“low* back pain*”[tiab] OR “lumbago”[tiab] OR “low* backache*”[tiab] OR “low* back ache*”[tiab] NOT medline[sb]) Filters: Systematic Reviews; Publication date from 2006/01/01; English; German | 158 | |

| #1 | Search low back pain[mesh] Filters: Systematic Reviews; Publication date from 2006/01/01; English; German | 715 | |

| Number of hits: 873 | |||

| PICO scheme: Population: low back pain, chronic or acute, non-specific low back pain Intervention: no restriction Comparison: no restriction Outcome: no restriction Study type: only systematic reviews | |||

| Searching strategy for Cochrane Library databases (20. April 2015) | |||

| No. | Query | Hits | |

| #3 | #1 or #2, Publication Year from 2006, in Cochrane Reviews (Reviews only), Other Reviews and Technology Assessments | 313 | |

| #2 | TI, AB, KW: “low* back pain*” or “lumbago” or “low* backache*” or “low* back ache*”:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) | 4862 | |

| #1 | MeSH descriptor: [Low Back Pain] explode all trees | 2127 | |

| Number of hits: 313 | |||

| Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (48) Others (208) Health Technology Assessment Database (57) | |||

| Summary of results from databases | |||

| Medline | Cochrane Databases | Total | |

| Aggregated evidence | |||

| Hits (2006–2015) |

873 | 313 | 1186 |

| Relevant hits (2010–2015) |

576 | 201 | 777 |

eFigure 1.

Flow chart for literature search

Recommendation grades and consensus process

Recommendation grades were assigned in consideration of the following:

the strength of the underlying evidence

ethical commitments

the clinical relevance of the effect strengths that were documented in the studies

the applicability of the study findings to the target patient group

patient preferences

and the practicality of implementation in routine clinical practice.

Two upward arrows (??) indicate a strong recommendation, a single upward arrow (?) indicates a weak recommendation, and a horizontal double arrow (?) indicates an open recommendation. The recommendations, algorithms, and information for patients were agreed upon in a formalized, written voting procedure (Delphi process) or in a consensus conference (nominal group process). The draft guideline was made accessible for public comment in September 2016 (www.versorgungsleitlinien.de). Potential consequences of the comments that were received were voted upon in a written Delphi process (e4).

Results

Diagnostic evaluation

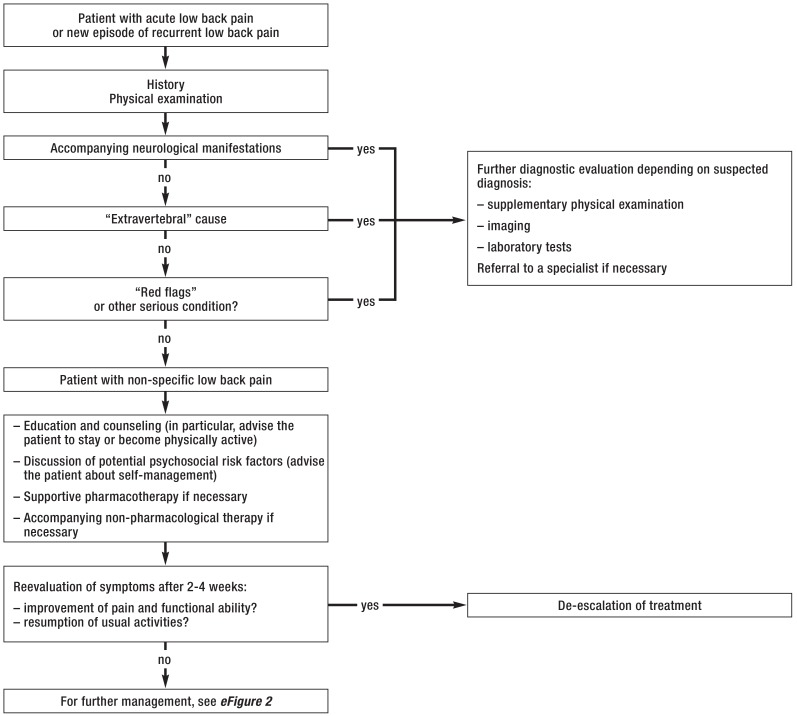

If the initial history and physical examination of a patient with low back pain do not yield any sign of a dangerous course of the disease or other serious conditions, no further diagnostic steps should be undertaken for the time being (??, expert consensus). Restricting the diagnostic evaluation spares the patient an unnecessary burden while avoiding unnecessary costs for the health-care system (e5). Intensive diagnostic evaluation that is not justified by clinical findings will only exceptionally result in a relevant, specific diagnosis and may well promote the patient’s fixation on his or her condition and the chronification of pain (e6– e8). The Figure is a depiction of the diagnostic course of a patient with acute low back pain or a new episode of recurrent back pain, starting from the initial contact with a physician. If any somatic warning signs (“red flags”) are present (ebox 2), then further imaging or laboratory tests and/or referral to a specialist should ensue, depending on the particular diagnosis that is suspected and its degree of urgency (??, expert consensus).

Figure.

Diagnosis and treatment on initial contact with a physician

eBOX 2. “Extravertebral” causes, somatic warning signs (“red flags”) and psychosocial risk factors for chronification (“yellow flags”).

“Extravertebral” causes of low back pain (due to processes affecting neighboring organs not belonging to the bony, muscular, or discoligamentous structures of the spine):

abdominal and visceral processes, e.g., cholecystitis, pancreatitis

vascular changes, e.g., aortic aneurysms

gynecological causes, e.g., endometriosis

urological causes, e.g., urolithiasis, renal tumors, perinephric abscesses

neurological disease, e.g., peripheral neuropathy

mental and psychosomatic illnesses

Somatic warning signs (“red flags”)

-

Fracture/osteoporosis

severe trauma, e.g., due to automobile accident, fall from a height, sporting accident

minimal trauma (e.g., coughing, sneezing, or heavy lifting) in an elderly patient or a patient with osteoporosis

systemic steroid therapy

-

Infection

systemic symptoms, e.g., recent fever/chills, anorexia, fatigability

recent bacterial infection

intravenous drug abuse

immune suppression

underlying debilitating disease

recent spinal infiltration therapy

severe pain at night

-

Radiculopathy/neuropathy

in younger patients, disk herniation as the most common cause of nerve root compression

pain radiating down one or both legs in a dermatomal distribution, possibly associated with sensory disturbances such as numbness or tingling in the area of pain, and/or with weakness

cauda equina syndrome: bladder and bowel dysfunction of sudden onset, e.g. urinary retention, urinary frequency, incontinence

perianal/perineal sensory deficit

marked or progressive neurologic deficit (weakness, sensory deficit) in one or both lower limbs

improvement of pain with simultaneous worsening of weakness, up to complete loss of function of the segmental muscle (“nerve root death”)

-

Tumor/metastases

elderly patient

history of malignancy

systemic symptoms: weight loss, anorexia, fatigability

worse pain when supine

severe pain at night

-

Axial spondylarthritis

low back pain persisting for more than 12 weeks in a patient under age 45

insidious onset of pain

morning stiffness (= 30 minutes)

improvement of low back pain with movement rather than at rest

awakening at night or early in the morning because of pain

alternating buttock pain

progressive stiffness of the spine

accompanying peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, uveitis

concomitant psoriasis or inflammatory bowel disease

-

Psychosocial risk factors for chronification (“yellow flags”) (selection)

depressive mood, distress (i.e., negative stress, mainly related to occupation or workplace)

pain-related cognitions: e.g., catastrophizing tendency, helplessness/hopelessness, fear-avoidance beliefs

passive pain behavior: e.g., markedly defensive and fearful/avoidant behavior; excessively active pain behavior: task persistence, suppressive pain behavior

pain-related cognitions: thought suppression

somaticizing tendency

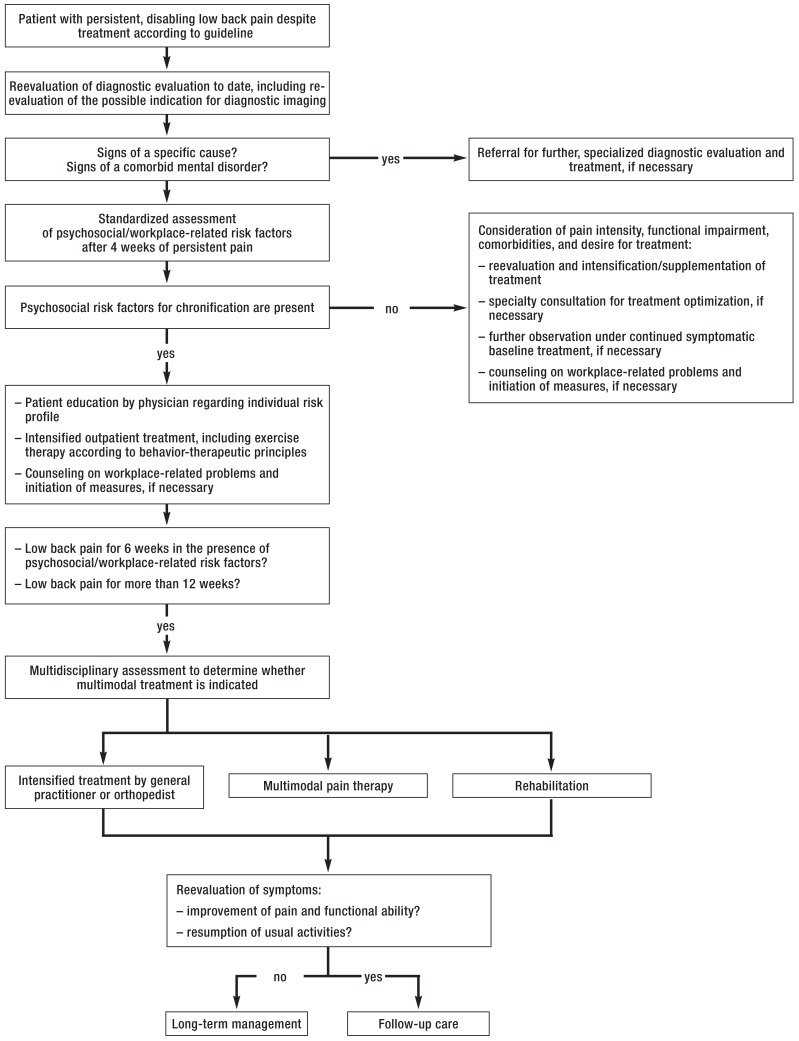

Psychosocial and workplace-related risk factors (ebox 2) should be considered from the beginning (??, expert consensus). After four weeks of persistent pain with an inadequate response to treatment that has been provided in accordance with the guideline (efigure 2), the coordinating physician should assess psychosocial risk factors (“yellow flags”) with a standardized screening instrument (e.g., the STarT Back Tool or the Örebro Short Questionnaire) (?, expert consensus) and may also assess workplace-related factors with a standardized screening instrument (?, expert consensus). Patient information and related questionnaires are freely accessible via the German-language website www.kreuzschmerz.versorgungsleitlinien.de.

eFigure 2.

Diagnosis and treatment of persistent low back pain (at 4 weeks)

Imaging

Patients with acute or recurrent low back pain in whom the history and physical examination yield no evidence of a dangerous course of the disease or other serious condition should not undergo any imaging (??, [8, 9]). A systematic review of randomized and controlled trials (RCTs) revealed that, among patients with acute or subacute low back pain who have no clinical evidence of a serious condition, the intensity of pain at three months or at 6–12 months was no different in those who underwent imaging immediately than in those who had no imaging at all (standardized mean difference [SMD] at 3 months 0.11, 95% confidence interval [-0.29; 0.50]; corresponding figures at 6 months, -0.04 [-0.15; 0.07]), and at 12 months 0.01; [-0.17; 0.19]); the two groups of patients received the same treatment (8). These data were confirmed by a prospective cohort study involving 5239 patients over age 65 with acute low back pain: at one year, there was no difference in functional ability between patients who underwent imaging at an early or late date (i.e., less vs. more than 6 weeks after diagnosis). The SMD and confidence interval figures were, for plain x-rays, -0.10 [-0.71; 0.5]; for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT), -0.51; [-1.62; 0.60]) (9). Moreover, imaging can lead to unnecessary treatment and promote chronification (10). Patient information leaflets were developed as an aid to physician-patient communication on this topic.

Most patients experience appreciable improvement within 6 weeks (11). For patients whose low back pain continues to limit their physical activity or has worsened despite treatment in accordance with the guideline (efigure 2), the indication for diagnostic imaging should be reassessed in 4 to 6 weeks (??, expert consensus based on [10, 12]). Early reassessment in 2–4 weeks may be necessary if a currently employed patient has been unable to work for a considerable period of time, or if a diagnostic evaluation is required before the initiation of multimodal treatment. The authors of the guideline consider one-time diagnostic imaging to be justified as part of such an assessment, alongside the history and physical examination. Nevertheless, imaging that lacks any potential therapeutic relevance should be avoided. After 4–6 weeks of pain, physicians should place greater emphasis on the search for a specific somatic cause than at the patient’s initial presentation. Even in patients with persistent pain, however, the physician should first consider whether the symptoms and course might not be accounted for by other risk factors or by the individual history. Current evidence does not support routine imaging (e.g., MRI) for chronic, non-specific low back pain (12).

An analysis of claims data by WIdO (which is the scientific department of AOK, a German health-insurance carrier) revealed that 26% of patients with low back pain underwent two instances of diagnostic imaging of the lumbar spine within 5 years, and 27% underwent three or more (4). Patients with unchanged symptoms should not undergo repeated imaging (??, expert consensus), as there is no reason to expect any relevant structural changes calling for a change in the treatment strategy. If the symptoms change, however, the indications for imaging may need to be reassessed.

Multidisciplinary assessment

Patients whose activities in everyday life are still restricted and who still have inadequate relief of pain despite 12 weeks of treatment in accordance with the guideline, as well as patients with an exacerbation of chronic non-specific low back pain, should undergo multidisciplinary assessment (??, expert consensus). Patients at high risk of chronification should undergo such an assessment after 6 weeks of persistent pain (efigure 2). In the assessment, the patient’s symptoms are evaluated as comprehensively and holistically as possible and the findings are discussed in a multidisciplinary case conference, where plans are made for further diagnostic evaluation and treatment.

In the outpatient setting, the principles of multidisciplinary assessment are best met by combining the diagnostic expertise of the physician, the physical therapist, and the psychologist. Broad implementation is generally difficult in ambulatory care but is feasible in the German health care system with the aid of an “integrated care contract” (IV-Vertrag; IV = integrierte Versorgung). Such assessments are regularly performed in multidisciplinary pain centers, which are entitled to obtain reimbursement for them, but usually only in a later phase of the course of the disease (13).

The management of low back pain

A physician should be responsible the overall care process (Figure and eFigure 2) (??, expert consensus). Over the course of the disease, the physician should continually explain the condition and the treatment to the patient and should encourage the pursuit of a healthful lifestyle, including regular physical exercise (??, [e9–e13]). Recommendations for special situations are summarized in Box 1. The diagnostic and therapeutic process for patients with persistent low back pain is presented in eFigure 2.

BOX 1. Care requirements in special situations*.

-

Pharmacotherapy for longer periods of time (>4 weeks)

need for the continuation of pharmacotherapy

side effects (e.g., gastrointestinal symptoms due to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAID])

interactions with other drugs

appropriate dosing; dose reduction or switch to another drug if necessary (consultation with specialist)

use of suitable non-pharmacological measures, e.g., psychosocial interventions

need for specialized work-up or follow-up of pre-existing or new comorbidities

need for the initiation of multimodal treatment

-

Discharge from multimodal treatment

support with the initiation and adaptation of treatment measures; monitoring of implementation if necessary

stepwise reintroduction to the workplace or initiation of occupational reintegration measures

initiation and coordination of further psychotherapeutic care, if necessary

coordination of continued care by a specialist, if necessary

consideration of the patient‘s disability and compensation status (consequent to medical judgments) and its potential effects on health, if necessary

-

Persistent chronification factors and/or psychosocial consequences of the painful condition

basic psychosomatic care

regular screening for chronification factors

initiation and coordination of further psychotherapeutic care, if necessary; the patient should be encouraged to participate as a component of medical treatment

possibly social counseling with respect to disability and compensation, or initiation of such counseling

possibly suggestion of measures for occupational reintegration and/or retraining

-

Symptom-maintaining or symptom-reinforcing comorbidities

(e.g., affective disorders such as anxiety and depression, or somatoform disorders)

regular appointments for treatment; unscheduled visits only in case of an emergency

basic psychosomatic care

initiation and coordination of disorder-specific treatment

-

Continued inability to work

screening for workplace-related risk factors

contact with company physician (if there is one) and, if necessary, with employer (after discussion with the patient) or pension insurance company

consider and, if necessary, initiate measures to support occupational reintegration

*Selected items; for the full table, see the NDMG on non-specific low back pain

Non-pharmacological treatment

Patients should be instructed to continue their usual physical activities as much as possible (??, [14]). Systematic reviews of RCTs have shown that bed rest for patients with acute non-specific low back pain either has no effect or actually delays recovery and the resumption of everyday activities, leading to longer periods of medically excused absence from work (14, 15). Bed rest should not be a part of the treatment of non-specific low back pain, and patients should be advised against it (??, [14, 15]).

Exercise therapy combined with educative measures based on behavioral-therapeutic principles should be used in the primary treatment of chronic non-specific low back pain (??, [16, e14–e38]). It yields more effective pain reduction and better functional ability than can be achieved with general medical care and passive treatment measures (16, e14– e34). Programs for strengthening and stabilizing the musculature seem to relieve low back pain better than programs with a cardiopulmonary orientation (e35, e36). Reviews of RCTs have shown that exercise programs based on a behavior-therapeutic approach improve physical functional ability and speed up the return to work (e22, e37). Current evidence does not show which specific type of exercise therapy is best for pain relief and improved functional ability (e14– e34). The choice of exercise therapy is, therefore, based mainly on the patient’s preference, everyday life circumstances, and physical fitness and the availability of a qualified therapist to carry it out (e39).

Weaker recommendations are given for rehabilitative sports and functional training (?, expert consensus) and progressive muscle relaxation (?, [e40]). Self-administered heat therapy (?, [15, e41–e43]), manual therapies such as manipulation and mobilization (?, [e44–e47]), massage (?, [17, e34, e48, e49]), ergotherapy (?, [e50]), “back school” (?, [17, e51–e54]), and acupuncture (?, [e28, e55–e57]) can be used to treat chronic low back pain as part of an overall concept in combination with activating therapeutic measures.

Strongly negative recommendations are given with regard to interventions for which there is little or no evidence of benefit, even if there is no evidence of harm either. This is done so as not to imply that these methods are an acceptable alternative to maintaining physical activity; a passive approach to treatment should not be promoted. The authors of the guideline, considering this to be a relevant potential harm, have altered the recommendation strengths accordingly. These interventions, while discouraged, may still be used in individual cases, in combination with physical exercise, as long as there is no evidence that they cause harm. Negative recommendations are given for interference-current therapy (e58– e62), kinesiotaping (e63, e64), short-wave diathermy (e65– e68), laser therapy (17, e69), magnetic field therapy (e70), medical aids (e71– e74), percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (PENS) (17, e75), traction devices (17, e76), cryotherapy (e41), transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), and therapeutic ultrasound (e77, e78).

Pharmacotherapy

The treatment of non-specific low back pain with drugs is purely symptomatic. In the acute phase, drugs are used to support non-pharmacologic measures, so that the patient can return to his or her usual activities as soon as possible. The treatment of chronic low back pain with drugs is indicated if the physician considers it potentially helpful for the implementation of activating measures, or else when, despite the appropriate performance of these measures, the patient still has an intolerable functional impairment due to pain.

Overall, there is moderate evidence with a low-to-intermediate effect size showing that treatment with drugs relieves acute and chronic non-specific low back pain. Particularly long-term treatment carries relevant risks including major adverse effects. It follows that the physician must carefully weigh the risks and benefits of pharmacotherapy when starting pharmacotherapy (box 2).

BOX 2. The principles of pharmacotherapy for non-specific low back pain.

The following principles apply regardless of the choice of drug and the mode of its introduction and administration (??, expert consensus):

The patient should be informed that drugs are only a supportive measure for persons with low back pain.

A realistic, relevant therapeutic goal should be set, with reference to physical function (e.g., an increase in the distance the patient can walk or in some other type of physical exertion, relevant pain relief [>30% or >50%]).

The drug should be chosen on an individual basis, with due consideration of comorbidities and comedication, drug intolerances, and the patient’s prior experiences and preferences (see also the guideline on multiple drug prescription [DEGAM)] [e79] and the PRISCUS and FORTA lists [DGIM] [e80, e81]).

The dose of the drug should be titrated in steps until the benefit is achieved at the lowest possible dose.

The patient should be monitored at regular intervals (ca. every 4 weeks) to assess the desired and undesired effects of medication.

Drugs for acute pain should be stopped or tapered to off when the pain improves.

Drug treatment should be continued only if effective and well tolerated; its effects should be monitored at regular intervals (every three months).

Drugs that are inadequately effective (despite appropriately prescribed doses) or that cause relevant side effects should be stopped or tapered to off.

DEGAM: German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin e. V.); DGIM: German Society for Internal Medicine (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Innere Medizin e. V.); FORTA: “Fit for the aged”; PRISCUS, “potentially inappropriate medication in the elderly“

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) are the pain-relieving drugs most likely recommended. Multiple reviews have documented the short-term analgesic effect and the functional benefit of oral NSAID, compared to placebo, in patients with acute and chronic non-specific low back pain, with a median difference of -5.96 points [-10.96; -0.96] at 16 weeks on a Visual Analog Scale ranging from 0 to 100 (15, 18– 21). To minimize side effects NSAIDs should be given in the lowest effective dose and for the shortest possible time (?). Considering the contraindications, COX-2-inhibitors can be used if NSAIDs are contraindicated or poorly tolerated (off-label-use) (?, [18–20]).

In individual cases, metamizole can be considered as an treatment option if non-opiod analgesics are contraindicated or poorly tolerated. (?, expert consensus). The systematic literature search yielded no reviews documenting its efficacy against non-specific low back pain. The Medicines Committee of the German Medical Association (Arzneimittelkommission der deutschen Ärzteschaft, AkdÄ) recommends its use only for the approved indications (severe pain for which other treatments are not indicated) and states that the patient must be adequately informed about its side effects, particularly the manifestations of agranulocytosis, which include fever, sore throat, and lesions of the oral mucosa. Monitoring of the complete blood count is recommended whenever agranulocytosis is suspected, as well as for all patients taking the drug over the long term (22).

In the light of new evidence, paracetamol (= acetaminophen) should no longer be used (?, [23]). In comparison to placebo, the use of this drug did not lead to any improvement in pain (weighted mean difference [WMD] 1.4 [-1.3; 4.1]) or functional ability (WMD -1.9 [-4.8; 1.0]) in patients with either acute or chronic non-specific low back pain. Nor should flupirtine be used to treat non-specific low back pain (??, [24–32]): its inadequately documented benefit is outweighed by its risks—mainly hepatotoxicity, ranging from elevated liver function parameters to organ failure, and potential dependence (27– 29) (cf. the risk assessment of the European Medicines Agency [EMA] [33]).

Opioid drugs can be a treatment option for acute non-specific low back pain if non-opioid analgesics are contraindicated or have been found to be ineffective in the individual patient (?, [e82–e86]). The indication for opioid drugs should be regularly reassessed at intervals of no longer than 4 weeks (??, [7]). They can be used to treat chronic non-specific low back pain for 4 to 12 weeks initially (?, [19, 34–36]). If this brief period of treatment brings about a relevant improvement in the patient’s pain and/or subjective physical impairment, while causing only minor or no side effects, then opioid drugs can also be a long-term therapeutic option (?, [37]). In the review articles that were identified for the creation of this guideline, the administration of opioid drugs (weak and strong, oral and transdermal) for a brief or intermediate period of time (4 to 26 weeks) significantly reduced pain (SMD: -0.43 [-0.52; -0.33]) and mildly improved physical functional ability (SMD: -0.26 [-0.37; -0.15]) compared to placebo (19, 34– 36). Open long-term observations from the late observational phase of RCTs have revealed long-term analgesic efficacy in approximately 25% of the patients initially included in the trials (37). The most important points to be considered with respect to opioid therapy are summarized in the Table.

Invasive treatments

Non-specific low back pain should not be treated with percutaneous procedures (??, [e34, e87–e94]) or with surgery (??, [e95–e103]). Nor should intravenously, intramuscularly, or subcutaneously administered analgesic drugs, local anesthetics, glucocorticoids, or mixed infusions be used (??, [e104–e112]).

Multimodal treatment programs

Patients with subacute and chronic non-specific low back pain should be treated in multimodal programs if less intensive evidence-based treatments have yielded an insufficient benefit (??, [17, 38, 39]). Trials have shown the superiority of multimodal programs over traditional treatments, waiting lists, or less intensive forms of treatment (17, 38, 39). According to the most recent review, including data from a total of 6858 study participants, multimodal treatment was better than traditional treatment at lowering pain intensity (SMD: -0.21 [-0.37; -0.04]) and increasing physical functional ability (SMD: -0.23 [-0.40; -0.06]) at 12 months in patients with chronic, non-specific low back pain (38). The evidence in the underlying trials is of low to moderate quality, and some of the measured effects are weak. The heterogeneity of the findings can be attributed, in part, to wide variation in the content of the multimodal programs (39). In practice, such programs are offered by pain clinics and rehabilitation clinics (etable 2).

Table. Considerations regarding opioid treatment.

| Aspects of opioid treatment | |

| Choice of drug and formulation | – long-acting drugs, sustained-release preparations – oral intake is generally preferred; transdermal systems might be an option if oral intake is contraindicated – note the side-effect profile of the opioid analgesic drug – consider the patient’s comorbidities – take patient preferences into account |

| Titration (dose-finding)phase | – agree on treatment goals – educate the patient about side effects, risk of addiction, traffic safety – start at a low dose – fixed dosing schedule – incrementally raise dose depending on efficacy and tolerability – the optimal dose is the one at which the treatment goals are met with tolerable (or no) side effects – the oral morphine-equivalent dose should not exceed 120 mg/day, with rare exceptions – short-term use of non-sustained-release oral opioid analgesic drugs can be given “as needed” as an aid to titration |

| Long-term treatment | – no non-sustained-release oral opioid analgesic drugs administered as needed – if the pain worsens, add-on therapy with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) should be tried first, rather than an increase of the opioid dose – reevaluate at regular intervals: – attainment of treatment goals – side effects (e.g., loss of libido, psychological changes such as loss of interest, inattention, falls) – evidence of inappropriate use of prescribed medication – after 6 months of treatment with good response: – consider dose reduction or cessation – reassess the indication for continued treatment and the response to non-pharmacological treatment |

| Cessation of treatment | – individual treatment goals attainable by other therapeutic measures – individual treatment goals not met after 4–12 weeks of opioid therapy – appearance of intolerable or inadequately treatable side effects – persistent loss of effect despite modification of opioid therapy (dose adjustment, change of drug) – inappropriate use of prescribed opioid analgesic drug by the patient despite treatment in collaboration with an addiction specialist – the cessation of opioid analgesic treatment must be gradual |

Key Messages.

If, on the initial contact of a patient complaining of low back pain with a physician, the history and physical examination yield no evidence of a dangerous or otherwise serious pathological abnormality, no further studies are indicated for the time being.

Psychosocial and workplace-related factors should be asked about at the initial contact. If the pain persists four weeks later despite treatment, these factors should be systematically assessed with standardized questionnaires.

The physician should advise the patient to maintain or intensify physical exercise and should advise against bed rest. Exercise therapy should be used to treat chronic non-specific low back pain.

Analgesic drugs are only moderately effective; their main role is to support physical activity. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) are, under these circumstances, the most recommended drugs.

Patients with persistent pain and relevant impairment in the activities of daily living after (at most) 12 weeks of treatment should undergo a multidisciplinary assessment. Depending on the results of this assessment, they should then be offered multimodal treatment.

eTable 2. Differences between multimodal pain therapy in the curative sector and multimodal treatment in the rehabilitative sector.

| Multimodal pain therapy in the curative sector | Multimodal treament in the rehabilitative sector | |

| Indications | – The requirements for indicated treatments with curative intent according to the current regulations in Germany [§27 (1) SGB V] must be met: the purpose of such treatment is “to detect or cure a disease, to prevent its worsening, or to alleviate its symptoms.” – comprehensive diagnostic evaluation required – rehabilitative capacity not present /not given – comorbidities impeding effective treatment (e.g., severely limited cardiopulmonary reserve, poorly controlled metabolic diseases, neurological diseases, impaired mobility) – continual worsening of pain over the past six months: spreading of the painful area, appearance of new kinds of pain, change in the character of pain, increase in the duration or frequency of painful attacks – increased physical impairment or drug consumption – inappropriate drug use – difficulties encountered in the initiation or switching of drugs or in drug withdrawal – increased need for interventional procedures – need for more frequent and intensive treatment – need for intensive medical supervision with daily rounds or team discussions – significant psychosocial factors or comorbid mental disorders that are relevant to pain |

– The requirements for indicated rehabilitative treatment according to current regulations in Germany [§ 11 (2) SGB V or § 15 SGB VI] must be met: the purpose of such treatment is “to prevent, eliminate, lessen, or compensate for disability or nursing dependency, prevent its worsening, or alleviate its consequences.” – rehabilitative capacity and motivation must be present – limitation of daily activities and participation because of disease – marked endangerment of capacity for employment – already impaired capacity for employment – imminent need for nursing care – conse quences of disease that require treatment, and imminent or already existing physical impairment due to disease |

| Criteria for inpatient rehabilitation in a facility far from the patient’s home: – longstanding ineffective treatment – absence of local treatment facilities – need to eliminate contextual stress factors, e.g., workplace-related factors – need for (or recognized claim upon) participatory measures that require inpatient treatment | ||

| Special considerations | – reimbursement as per the German Operations and Procedures Key (Operationen- und Prozedurenschlüssel, OPS), defined in consideration of patient features and structural and procedural quality – is part of few selective contracts – intensive, bundled use of resources to achieve cure or stability for further outpatient care |

– medically / occupation–oriented rehabilitation – behavior-therapy-oriented rehabilitation |

| Hospitalization | – partial or full hospitalization | – on either an outpatient or an inpatient basis |

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Acknowledgements

We thank all authors and participants in the NDMG on non-specific low back pain: Prof. Dr. Heike Rittner, Prof. Dr. Monika Hasenbring, Dr. Tina Wessels, Patrick Heldmann, Prof. Dr. Annette Becker, Dr. Bernhard Arnold, Dr. Erika Schulte, Prof. Dr. Elke Ochsmann, PD Dr. Stephan Weiler, Prof. Dr. Werner Siegmund, Prof. Dr. Elisabeth Märker-Hermann, Prof. Dr. Martin Rudwaleit, Dr. Hermann Locher, Prof. Dr. Kirsten Schmieder, Prof. Dr. Uwe Max Mauer, Prof. Dr. Dr. Thomas R. Tölle, Prof. Dr. Till Sprenger, Dr. Wilfried Schupp, Prof. Dr. Thomas Mokrusch, Dr. Fritjof Bock, Dr. Andreas Korge, Dr. Andreas Winkelmann, Dr. Max Emanuel Liebl, PD Dr. Dipl.-Psych. Regine Klinger, Prof. Dr. Dipl.-Psych. Michael Hüppe, Dr. Dipl.-Psych. Anke Diezemann, Prof. Dr. Volker Köllner, Dr. Beate Gruner, Dr. Silke Brüggemann, Prof. Dr. Thomas Blattert, Dr. Matti Scholz, Prof. Dr. Karl-Friedrich Kreitner, Prof. Dr. Marc Regier, Prof. Dr. Hans-Raimund Casser, Ludwig Hammel, Manfred Stemmer, Prof. Dr. Tobias Schulte, Patience Higman, Heike Fuhr, Eckhardt Böhle, Reina Tholen, Dr. Dagmar Lühmann, Prof. Dr. Jost Langhorst, Dr. Petra Klose, Dr. Monika Nothacker, Dr. Christine Kanowski, Corinna Schaefer, Dr. Dr. Christoph Menzel, Peggy Prien, Isabell Vader.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Chenot has served as a paid consultant for WIdO, for the Bertelsmann Foundation, and for the Institute for Applied Health Care Research (Institut für angewandte Gesundheitsforschung, InGef).

Prof. Greitemann has served as a paid consultant for Bauerfeind AG. He has received author’s honoraria for works published by Springer and Thieme. He has received research funding from DRV Westfalen (a pension insurance company).

Prof. Kladny has received lecture honoraria from Bauerfeind.

Prof. Petzke has served as a paid consultant for Janssen-Cilag.

He is the director of a multimodal pain treatment facility.

Prof. Pfingsten has received lecture honoraria from Abbvie, Gruenenthal, and Pfizer.

Dr. Schorr states that she has no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund (DRV-Bund) DRV-Bund. Berlin: 2016. Reha-Bericht Update 2016. Die medizinische und berufliche Rehabilitation der Rentenversicherung im Licht der Statistik. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marschall J, Hildebrandt S, Sydow H, Nolting HD. Gesundheitsreport 2016. Analyse der Arbeitsunfähigkeitsdaten. Schwerpunkt: Gender und Gesundheit. Heidelberg: medhochzwei Verlag. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raspe H. Robert Koch-Institut (RKI) RKI. Berlin: 2012. Rückenschmerzen. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klauber J, Günster C, Gerste B, Robra BP. Versorgungs-Report 2013/2014. In: Schmacke N, editor. Schwerpunkt: Depression. Stuttgart Schattauer: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bundesärztekammer (BÄK), Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV), Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Nicht-spezifischer Kreuzschmerz - Langfassung, Version 1. doi.org/10.6101/AZQ/000353 (last accessed on 6 March 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bundesärztekammer (BÄK), Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV) Beurteilungskriterien für Leitlinien in der medizinischen Versorgung - Beschlüsse der Vorstände der Bundesärztekammer und Kassenärztlicher Bundesvereinigung, Juni 1997. Dtsch Arztebl. 1997;94:A2154–A-2155. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deutsche Schmerzgesellschaft. Langzeitanwendung von Opioiden bei nicht tumorbedingten Schmerzen - „LONTS“. www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/145-003.html (last accessed on 17 March 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chou R, Fu R, Carrino JA, Deyo RA. Imaging strategies for low-back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:463–472. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarvik JG, Gold LS, Comstock BA, et al. Association of early imaging for back pain with clinical outcomes in older adults. JAMA. 2015;313:1143–1153. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou R, Qaseem A, Owens DK, Shekelle P. Diagnostic imaging for low back pain: advice for high-value health care from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:181–189. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-3-201102010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.da C Menezes Costa L, Maher CG, Hancock MJ, McAuley JH, Herbert RD, Costa LO. The prognosis of acute and persistent low-back pain: a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2012;184:E613–E624. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chou D, Samartzis D, Bellabarba C, et al. Degenerative magnetic resonance imaging changes in patients with chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:S43–S53. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31822ef700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sens E, Mothes-Lasch M, Lutz JF. Interdisziplinäres Schmerzassessment im stationären Setting: Nur ein Türöffner zur multimodalen Schmerztherapie? Schmerz. 2017 [Epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1007/s00482-017-0237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahm KT, Brurberg KG, Jamtvedt G, Hagen KB. Advice to rest in bed versus advice to stay active for acute low-back pain and sciatica. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007612.pub2. CD007612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdel SC, Maher CG, Williams KA, McLachlan AJ. Interventions available over the counter and advice for acute low back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2014;15:2–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Malmivaara A, Koes BW. Exercise therapy for treatment of non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000335.pub2. CD000335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Middelkoop M, Rubinstein SM, Kuijpers T, et al. A systematic review on the effectiveness of physical and rehabilitation interventions for chronic non-specific low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2011;20:19–39. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1518-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roelofs PD, Deyo RA, Koes BW, Scholten RJ, van Tulder MW. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000396.pub3. CD000396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung JW, Zeng Y, Wong TK. Drug therapy for the treatment of chronic nonspecific low back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Physician. 2013;16:E685–E704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuijpers T, van Middelkoop M, Rubinstein SM, et al. A systematic review on the effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for chronic non-specific low-back pain. Eur Spine J. 2011;20:40–50. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1541-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Enthoven WT, Roelofs PD, Deyo RA, van Tulder MW, Koes BW. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012087. CD012087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arzneimittelkommission der deutschen Ärzteschaft (AkdÄ) Agranulozytose nach Metamizol - sehr selten, aber häufiger als gedacht. Dtsch Arztebl. 2011;108 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Machado GC, Maher CG, Ferreira PH, et al. Efficacy and safety of paracetamol for spinal pain and osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo controlled trials. BMJ. 2015;350 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wörz R, Bolten W, Heller B, Krainick JU, Pergande G. Flupirtin im Vergleich zu Chlormezanon und Plazebo bei chronischen muskulöskelettalen Rückenschmerzen Ergebnisse einer multizentrischen randomisierten Doppelblindstudie. Fortschr Med. 1996;114:500–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li C, Ni J, Wang Z, et al. Analgesic efficacy and tolerability of flupirtine vs tramadol in patients with subacute low back pain: a double-blind multicentre trial*. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:3523–3530. doi: 10.1185/03007990802579769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Überall MA, Mueller-Schwefe GH, Terhaag B. Efficacy and safety of flupirtine modified release for the management of moderate to severe chronic low back pain: results of SUPREME, a prospective randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled parallel-group phase IV study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28:1617–1634. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.726216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michel MC, Radziszewski P, Falconer C, Marschall-Kehrel D, Blot K. Unexpected frequent hepatotoxicity of a prescription drug, flupirtine, marketed for about 30 years. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73:821–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04138.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein F, Glanemann M, Rudolph B, Seehofer D, Neuhaus P. Flupirtine-induced hepatic failure requiring orthotopic liver transplant. Exp Clin Transplant. 2011;9:270–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puls F, Agne C, Klein F, et al. Pathology of flupirtine-induced liver injury: a histological and clinical study of six cases. Virchows Arch. 2011;458:709–716. doi: 10.1007/s00428-011-1087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wörz R. Zur Langzeitbehandlung chronischer Schmerzpatienten mit Flupirtin. MMW Fortschr Med. 2014;156:127–134. doi: 10.1007/s15006-014-3759-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Douros A, Bronder E, Andersohn F, et al. Flupirtine-induced liver injury—seven cases from the Berlin Case-control Surveillance Study and review of the German spontaneous adverse drug reaction reporting database. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70:453–459. doi: 10.1007/s00228-013-1631-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Überall MA, Essner U, Müller-Schwefe GH. 2-Wochen-Wirksamkeit und -Verträglichkeit von Flupirtin MR und Diclofenac bei akuten Kreuz-/Rückenschmerzen Ergebnisse einer Post-hoc-Subgruppenanalyse individueller Patientendaten von vier nichtinterventionellen Studien. MMW Fortschr Med. 2013;155:115–123. doi: 10.1007/s15006-013-2542-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.European Medicines Agency (EMA) PRAC recommends restricting the use of flupirtine-containing medicines. Committee also recommends weekly monitoring of patients‘ liver function. EMA/362055/2013. www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/ (last accessed on 17 March 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chaparro LE, Furlan AD, Deshpande A, Mailis-Gagnon A, Atlas S, Turk DC. Opioids compared to placebo or other treatments for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;8 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004959.pub4. CD004959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petzke F, Welsch P, Klose P, Schaefert R, Sommer C, Häuser W. Opioide bei chronischem Kreuzschmerz Systematische Übersicht und Metaanalyse der Wirksamkeit, Verträglichkeit und Sicherheit in randomisierten, placebokontrollierten Studien über mindestens 4 Wochen. Schmerz. 2015;29:60–72. doi: 10.1007/s00482-014-1449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abdel Shaheed C, Maher CG, Williams KA, Day R, McLachlan AJ. Efficacy, tolerability, and dose-dependent effects of opioid analgesics for low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:958–968. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hauser W, Bernardy K, Maier C. Langzeittherapie mit Opioiden bei chronischem nicht-tumorbedingtem Schmerz - Systematische Übersicht und Metaanalyse der Wirksamkeit, Verträglichkeit und Sicherheit in offenen Anschlussstudien über mindestens 26 Wochen. Schmerz. 2015;29:96–108. doi: 10.1007/s00482-014-1452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;9 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000963.pub3. CD000963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waterschoot FP, Dijkstra PU, Hollak N, de Vries HJ, Geertzen JH, Reneman MF. Dose or content? Effectiveness of pain rehabilitation programs for patients with chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Pain. 2014;155:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) Zuckschwerdt. München: 2012. Das AWMF-Regelwerk Leitlinien. [Google Scholar]

- E2.Ärztliches Zentrum für Qualität in der Medizin (ÄZQ), Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) Deutsches Instrument zur methodischen Leitlinien-Bewertung (DELBI). Fassung 2005/2006 + Domäne 8. www.leitlinien.de/mdb/edocs/pdf/literatur/delbi-fassung-2005-2006-domaene-8-2008.pdf (last accessed on 26 June 2017 [Google Scholar]

- E3.Bundesärztekammer (BÄK) Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV), Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) Nationales Programm für VersorgungsLeitlinien. Methoden-Report 4. edition. www.leitlinien.de/mdb/downloads/nvl/methodik/mr-aufl-4-version-1.pdf (last accessed on 26 June 2017 [Google Scholar]

- E4.Bundesärztekammer (BÄK) Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV), Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Nicht-spezifischer Kreuzschmerz - Leitlinienreport, Version 1. doi.org/10.6101/AZQ/000330 (last accessed on 6 March 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E5.Gilbert FJ, Grant AM, Gillan MG, et al. Low back pain: influence of early MR imaging or CT on treatment and outcome—multicenter randomized trial. Radiology. 2004;231:343–351. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2312030886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Kendrick D, Fielding K, Bentley E, Kerslake R, Miller P, Pringle M. Radiography of the lumbar spine in primary care patients with low back pain: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2001;322:400–405. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7283.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Jarvik JJ, Hollingworth W, Heagerty P, Haynor DR, Deyo RA. The longitudinal assessment of imaging and disability of the back (LAIDBack) study: baseline data. Spine. 2001;26:1158–1166. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200105150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, Modic MT, Malkasian D, Ross JS. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:69–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407143310201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Engers A, Jellema P, Wensing M, van der Windt DA, Grol R, van Tulder MW. Individual patient education for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004057.pub3. CD004057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Traeger AC, Hubscher M, Henschke N, Moseley GL, Lee H, McAuley JH. Effect of primary care-based education on reassurance in patients with acute low back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:733–743. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Clarke CL, Ryan CG, Martin DJ. Pain neurophysiology education for the management of individuals with chronic low back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Man Ther. 2011;16:544–549. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Liddle SD, Gracey JH, Baxter GD. Advice for the management of low back pain: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Man Ther. 2007;12:310–327. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Holden J, Davidson M, O‘Halloran PD. Health coaching for low back pain: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Clin Pract. 2014;68:950–962. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Ferreira ML, Smeets RJ, Kamper SJ, Ferreira PH, Machado LA. Can we explain heterogeneity among randomized clinical trials of exercise for chronic back pain? A meta-regression analysis of randomized controlled trials. Physical Therapy. 2010;90:1383–1403. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20090332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Buechter RB, Fechtelpeter D. Climbing for preventing and treating health problems: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Ger Med Sci. 2011;9 doi: 10.3205/000142. Doc19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Smith BE, Littlewood C, May S. An update of stabilisation exercises for low back pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15 doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.McCaskey MA, Schuster-Amft C, Wirth B, Suica Z, de Bruin ED. Effects of proprioceptive exercises on pain and function in chronic neck- and low back pain rehabilitation: a systematic literature review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15 doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Yue YS, Wang XD, Xie B, et al. Sling exercise for chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099307. e99307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Wang XQ, Zheng JJ, Yu ZW, et al. A meta-analysis of core stability exercise versus general exercise for chronic low back pain. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052082. e52082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Scharrer M, Ebenbichler G, Pieber K, et al. A systematic review on the effectiveness of medical training therapy for subacute and chronic low back pain. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2012;48:361–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E21.Kriese M, Clijsen R, Taeymans J, Cabri J. Segmentale Stabilisation zur Behandlung von lumbalen Rückenschmerzen: Ein systematisches Review. Sportverletz Sportschaden. 2010;24:17–25. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1251512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E22.Bunzli S, Gillham D, Esterman A. Physiotherapy-provided operant conditioning in the management of low back pain disability: a systematic review. Physiother Res Int. 2011;16:4–19. doi: 10.1002/pri.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E23.Surkitt LD, Ford JJ, Hahne AJ, Pizzari T, McMeeken JM. Efficacy of directional preference management for low back pain: a systematic review. Physical Therapy. 2012;92:652–665. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E24.Dunsford A, Kumar S, Clarke S. Integrating evidence into practice: use of McKenzie-based treatment for mechanical low back pain. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2011;4:393–402. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S24733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E25.Patti A, Bianco A, Paoli A, et al. Effects of pilates exercise programs in people with chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000383. e383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E26.Wells C, Kolt GS, Marshall P, Hill B, Bialocerkowski A. The effectiveness of pilates exercise in people with chronic low back pain: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100402. e100402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E27.Miyamoto GC, Costa LO, Cabral CM. Efficacy of the pilates method for pain and disability in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Braz J Phys Ther. 2013;17:517–532. doi: 10.1590/S1413-35552012005000127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E28.Yuan QL, Guo TM, Liu L, Sun F, Zhang YG. Traditional Chinese medicine for neck pain and low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117146. e0117146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E29.O‘Connor SR, Tully MA, Ryan B, et al. Walking exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:724–734. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E30.Holtzman S, Beggs RT. Yoga for chronic low back pain: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Res Manag. 2013;18:267–272. doi: 10.1155/2013/105919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E31.Hill C. Is yoga an effective treatment in the management of patients with chronic low back pain compared with other care modalities—a systematic review. J Complement Integr Med. 2013;10:1–9. doi: 10.1515/jcim-2012-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E32.Ward L, Stebbings S, Cherkin D, Baxter GD. Yoga for functional ability, pain and psychosocial outcomes in musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Musculoskeletal Care. 2013;11:203–217. doi: 10.1002/msc.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E33.Cramer H, Lauche R, Haller H, Dobos G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of yoga for low back pain. Clin J Pain. 2013;29:450–460. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31825e1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E34.Chambers H. Physiotherapy and lumbar facet joint injections as a combination treatment for chronic low back pain. A narrative review of lumbar facet joint injections, lumbar spinal mobilizations, soft tissue massage and lower back mobility exercises. Musculoskeletal Care. 2013;11:106–120. doi: 10.1002/msc.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E35.Searle A, Spink M, Ho A, Chuter V. Exercise interventions for the treatment of chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Rehabil. 2015;29:1155–1167. doi: 10.1177/0269215515570379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E36.Hendrick P, Te Wake AM, Tikkisetty AS, Wulff L, Yap C, Milosavljevic S. The effectiveness of walking as an intervention for low back pain: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:1613–1620. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1412-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E37.Oesch P, Kool J, Hagen KB, Bachmann S. Effectiveness of exercise on work disability in patients with non-acute non-specific low back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Rehabil Med. 2010;42:193–205. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E38.Richards MC, Ford JJ, Slater SL, et al. The effectiveness of physiotherapy functional restoration for post-acute low back pain: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2013;18:4–25. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E39.Slade SC, Patel S, Underwood M, Keating JL. What are patient beliefs and perceptions about exercise for non-specific chronic low back pain? A systematic review of qualitative studies. Clin J Pain. 2014;30:995–1005. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E40.Henschke N, Ostelo RW, van Tulder MW, et al. Behavioural treatment for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002014.pub3. CD002014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E41.French SD, Cameron M, Walker BF, Reggars JW, Esterman AJ. A Cochrane review of superficial heat or cold for low back pain. Spine. 2006;31:998–1006. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000214881.10814.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E42.Oltean H, Robbins C, van Tulder MW, Berman BM, Bombardier C, Gagnier JJ. Herbal medicine for low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004504.pub4. CD004504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E43.Rubinstein SM, van Middelkoop M, Kuijpers T, et al. A systematic review on the effectiveness of complementary and alternative medicine for chronic non-specific low-back pain. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:1213–1228. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1356-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E44.Franke H, Fryer G, Ostelo RW, Kamper SJ. Muscle energy technique for non-specific low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009852.pub2. CD009852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E45.Rubinstein SM, Terwee CB, Assendelft WJ, de Boer MR, van Tulder MW. Spinal manipulative therapy for acute low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008880.pub2. CD008880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E46.Franke H, Franke JD, Fryer G. Osteopathic manipulative treatment for nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15 doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E47.Orrock PJ, Myers SP. Osteopathic intervention in chronic non-specific low back pain: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14 doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E48.Furlan AD, Giraldo M, Baskwill A, Irvin E, Imamura M. Massage for low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001929.pub3. CD001929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E49.Furlan AD, Yazdi F, Tsertsvadze A, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and safety of selected complementary and alternative medicine for neck and low-back pain. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/953139. 953139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E50.Schaafsma FG, Whelan K, van der Beek AJ, van der Es-Lambeek LC, Ojajarvi A, Verbeek JH. Physical conditioning as part of a return to work strategy to reduce sickness absence for workers with back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;8 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001822.pub3. CD001822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E51.Heymans MW, van Tulder MW, Esmail R, Bombardier C, Koes BW. Back schools for non-specific low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000261.pub2. CD000261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E52.Arzneimittelkommission der deutschen Ärzteschaft (AkdÄ) Empfehlungen zur Therapie von Kreuzschmerzen. www.akdae.de/Arzneimitteltherapie/TE/A-Z/PDF/Kreuzschmerz.pdf#page=1&view=fitB (last accessed on 20 April 2017) (3) [Google Scholar]

- E53.Kuhnt U, Fleichaus J. Dortmunder Deklaration zur Förderung der nationalen Rückengesundheit durch die Neue Rückenschule 2008. www.kddr.de/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/Dortmunder-Deklaration2008.pdf (last accessed on 9 November 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E54.Kempf HD, editor. Verl. Heidelberg Springer Med: 2010. Die neue Rückenschule. Das Praxisbuch. [Google Scholar]

- E55.Lam M, Galvin R, Curry P. Effectiveness of acupuncture for nonspecific chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38:2124–2138. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000435025.65564.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E56.Xu M, Yan S, Yin X, et al. Acupuncture for chronic low back pain in long-term follow-up: a meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials. Am J Chin Med. 2013;41:1–19. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X13500018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E57.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1444–1453. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E58.Hurley DA, McDonough SM, Dempster M, Moore AP, Baxter GD. A randomized clinical trial of manipulative therapy and interferential therapy for acute low back pain. Spine. 2004;29:2207–2216. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000142234.15437.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E59.Hurley DA, Minder PM, McDonough SM, Walsh DM, Moore AP, Baxter DG. Interferential therapy electrode placement technique in acute low back pain: a preliminary investigation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:485–493. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.21934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E60.Werners R, Pynsent PB, Bulstrode CJ. Randomized trial comparing interferential therapy with motorized lumbar traction and massage in the management of low back pain in a primary care setting. Spine. 1999;24:1579–1584. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199908010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E61.Lara-Palomo IC, Aguilar-Ferrandiz ME, Mataran-Penarrocha GA, et al. Short-term effects of interferential current electro-massage in adults with chronic non-specific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27:439–449. doi: 10.1177/0269215512460780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E62.Facci LM, Nowotny JP, Tormem F, Trevisani VF. Effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and interferential currents (IFC) in patients with nonspecific chronic low back pain: randomized clinical trial. Sao Paulo Med J. 2011;129:206–216. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802011000400003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E63.Vanti C, Bertozzi L, Gardenghi I, Turoni F, Guccione AA, Pillastrini P. Effect of taping on spinal pain and disability: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Physical Therapy. 2015;95:493–506. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E64.Parreira PC, Costa LC, Hespanhol Junior LC, Lopes AD, Costa LO. Current evidence does not support the use of Kinesio Taping in clinical practice: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2014;60:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E65.Rasmussen GG. Manipulation in treatment of low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. Man Med. 1979;1:8–10. [Google Scholar]

- E66.Gibson T, Grahame R, Harkness J, Woo P, Blagrave P, Hills R. Controlled comparison of short-wave diathermy treatment with osteopathic treatment in non-specific low back pain. Lancet. 1985;1:1258–1261. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92323-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E67.Sweetman BJ, Heinrich I, Anderson JAD. A randomized controlled trial of exercises, short wave diathermy, and traction for low back pain, with evidence of diagnosis-related response to treatment. J Orthop Rheumatol. 1993;6:159–166. [Google Scholar]

- E68.Durmus D, Ulus Y, Alayli G, et al. Does microwave diathermy have an effect on clinical parameters in chronic low back pain? A randomized-controlled trial. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2014;27:435–443. doi: 10.3233/BMR-140464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E69.Yousefi-Nooraie R, Schonstein E, Heidari K, et al. Low level laser therapy for nonspecific low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005107.pub4. CD005107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E70.Pittler MH, Brown EM, Ernst E. Static magnets for reducing pain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. CMAJ. 2007;177:736–742. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E71.van Duijvenbode I, Jellema P, van Poppel MN, van Tulder MW. Lumbar supports for prevention and treatment of low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;CD001823 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001823.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E72.Oleske DM, Lavender SA, Andersson GB, Kwasny MM. Are back supports plus education more effective than education alone in promoting recovery from low back pain? Results from a randomized clinical trial. Spine. 2007;32:2050–2057. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181453fcc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E73.Calmels P, Queneau P, Hamonet C, et al. Effectiveness of a lumbar belt in subacute low back pain: an open, multicentric, and randomized clinical study. Spine. 2009;34:215–220. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31819577dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E74.Chuter V, Spink M, Searle A, Ho A. The effectiveness of shoe insoles for the prevention and treatment of low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15 doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E75.Ehrenbrusthoff K, Ryan CG, Schofield PA, Martin DJ. Physical therapy management of older adults with chronic low back pain: a systematic review. J Pain Manag. 2012;5:317–329. [Google Scholar]

- E76.Wegner I, Widyahening IS, van Tulder MW, et al. Traction for low-back pain with or without sciatica. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;8 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003010.pub5. CD003010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E77.Ebadi S, Henschke N, Nakhostin AN, Fallah E, van Tulder MW. Therapeutic ultrasound for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009169.pub2. CD009169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E78.Seco J, Kovacs FM, Urrutia G. The efficacy, safety, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness of ultrasound and shock wave therapies for low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J. 2011;11:966–977. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E79.Leitliniengruppe Hessen, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin (DEGAM), PMV forschungsgruppe, Ärztliches Zentrum für Qualität in der Medizin (ÄZQ) Hausärztliche Leitlinie Multimedikation. Empfehlungen zum Umgang mit Multimedikation bei Erwachsenen und geriatrischen Patienten, Version 1.05. www.aezq.de/mdb/edocs/pdf/schriftenreihe/schriftenreihe41.pdf (last accessed on 9 November 2017) (1) [Google Scholar]

- E80.Holt A, Schmiedl S, Thürmann PA. Priscus-Liste potenziell inadäquater Medikation für ältere Menschens. www.priscus.net/download/PRISCUS-Liste_PRISCUS-TP3_2011.pdf (last accessed on 9 November 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E81.Institut für Experimentelle und Klinische Pharmakologie, Zentrum für Gerontopharmakologie, Abteilung für Medizinische Statistik BuI. Pazan F, eiß C, Wehling M. Die Forta-Liste.“Fit for the Aged“. Expert Consensus Validation 2015. www.umm.uni-heidelberg.de/ag/forta/FORTA_Liste_2015_deutsche_Version.pdf (last accessed on 9 November 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E82.Eken C, Serinken M, Elicabuk H, Uyanik E, Erdal M. Intravenous paracetamol versus dexketoprofen versus morphine in acute mechanical low back pain in the emergency department: a randomised double-blind controlled trial. Emerg Med J. 2014;31:177–181. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2012-201670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E83.Friedman BW, Dym AA, Davitt M, et al. Naproxen with Cyclobenzaprine, Oxycodone/Acetaminophen, or placebo for treating acute low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:1572–1580. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E84.Biondi D, Xiang J, Benson C, Etropolski M, Moskovitz B, Rauschkolb C. Tapentadol immediate release versus oxycodone immediate release for treatment of acute low back pain. Pain Physician. 2013;16:E237–E246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E85.Lasko B, Levitt RJ, Rainsford KD, Bouchard S, Rozova A, Robertson S. Extended-release tramadol/paracetamol in moderate-to-severe pain: a randomized, placebo-controlled study in patients with acute low back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28:847–857. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.681035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E86.Behrbalk E, Halpern P, Boszczyk BM, et al. Anxiolytic medication as an adjunct to morphine analgesia for acute low back pain management in the emergency department: a prospective randomized trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014;39:17–22. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E87.Waseem Z, Boulias C, Gordon A, Ismail F, Sheean G, Furlan AD. Botulinum toxin injections for low-back pain and sciatica. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008257.pub2. CD008257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E88.Henschke N, Kuijpers T, Rubinstein SM, et al. Injection therapy and denervation procedures for chronic low-back pain: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:1425–1449. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1411-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E89.Chou R, Hashimoto R, Friedly J, et al. Pain management injection therapies for low back pain Technology Assessment Report. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0073206/pdf/PubMedHealth_PMH0073206.pdf (last accessed on 9 November 2017) [Google Scholar]