Abstract

Purpose

Female veterans are at high risk for sleep problems, and there is a need to provide effective treatment for this population who experience insomnia. This study’s primary goal was to compare the acceptability of medication versus nonmedication treatments for insomnia among female veterans. In addition, we examined the role of patient age, severity of sleep disturbance, and psychiatric symptoms on acceptability of each treatment approach and on the differences in acceptability between these approaches.

Methods

A large nationwide postal survey was sent to a random sample of 4000 female veterans who had received health care at a Veterans Administration (VA) facility in the previous 6 months (May 29, 2012–November 28, 2012). A total of 1559 completed surveys were returned. Survey items used for the current analyses included: demographic characteristics, sleep quality, psychiatric symptoms, military service experience, and acceptability of medication and non-medication treatments for insomnia. For analysis, only ratings of “very acceptable” were used to indicate an interest in the treatment approach (vs ratings of “not at all acceptable,” “a little acceptable,” “somewhat acceptable,” and “no opinion/don’t know”).

Findings

In the final sample of 1538 women with complete data, 57.7% rated nonmedication treatment as very acceptable while only 33.5% rated medication treatment as very acceptable. This difference was statistically significant for the group as a whole and when examining subgroups of patients based on age, sleep quality, psychiatric symptoms, and military experience. The percentage of respondents rating medication treatment as very acceptable was higher for women who were younger, had more severe sleep disturbances, had more psychiatric symptoms, who were not combat exposed, and who had experienced military sexual trauma. By contrast, the percentage of respondents rating nonmedication treatment as very acceptable differed only by age (younger women were more likely to find nonmedication treatment acceptable) and difficulty falling asleep.

Implications

Female veterans are more likely to find nonmedication insomnia treatment acceptable compared with medication treatment. Thus, it is important to match these patients with effective behavioral interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Efforts to educate providers about these preferences and about the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia may serve to connect female veterans who have insomnia to the treatment they prefer. These findings also suggest that older female veterans may be less likely to find either approach as acceptable as their younger counterparts. (Clin Ther. 2016;38:2373–2385) Published by Elsevier HS Journals, Inc.

Keywords: cognitive-behavioral therapy, female veterans, insomnia, medications, sleep, treatment acceptability

INTRODUCTION

Women are the fastest growing demographic group within the veteran population, and the health care needs of female veterans are often different from those of their male counterparts.1 In addition, the health needs of female veterans are unique compared with women who have not served in the armed forces. For example, women have higher rates of posttraumatic stress disorder than men in the general population,2 and aspects of military service (eg, combat exposure) increase that risk. Insomnia, defined as persistent, frequent difficulty initiating and/or sustaining sleep accompanied by daytime symptoms,3,4 is also more common among women compared with men. A meta-analysis found that women are 1.4 times more likely to have insomnia than men, worldwide.5 The mean prevalence rate of insomnia among women in the United States is >23%; however, evidence suggests that insomnia rates among veterans may be as high as 60%.6 Thus, female veterans may experience insomnia at a much higher rate than civilian women. A previous study of female veterans in the Los Angeles area found that 54% of respondents to a postal survey met basic diagnostic criteria for an insomnia disorder.7

Despite this high prevalence rate, female veterans may not be reporting sleep difficulties to their providers. This scenario may be especially true for older women given that older patients are less likely to speak to health care providers about insomnia symptoms in general, perhaps due to a difference in beliefs and attitudes about sleep and sleep disturbances.8 One study found that older adults with chronic insomnia endorsed stronger beliefs about the negative consequences of insomnia, expressed more hopelessness about the fear of losing control of their sleep, and expressed more helplessness about its unpredictability.9 These maladaptive sleep-related cognitions are even more pronounced in older adults with anxiety and depression.10 Thus, even though there may be a high rate of insomnia among older female veterans, these women may not be seeking treatment from VA providers.

Insomnia is an important health concern because it is associated with poor clinical outcomes. Symptoms of insomnia are associated with an increased risk for hypertension,11 diabetes,12 and cardiac events.13 Individuals with insomnia report significantly lower quality of life,14 are at greater risk for accidents,15 and have higher rates of psychiatric comorbidities (eg, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD], suicidality).16–18 Insomnia also carries a substantial economic burden due to high health care costs19 and reduced work productivity.20 Treating female veterans of all ages who have insomnia is an important goal in improving health, longevity, and quality of life.

Evidence-based treatments for insomnia include pharmacologic therapy with sedative-hypnotic medications, cognitive-behavioral approaches (eg, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia [CBT-I]), or both. Studies21,22 have shown that both approaches are effective in terms of improving sleep over the short term; however, CBTs are superior in terms of maintained benefits.22,23 In addition, clinical practice guidelines strongly recommend CBT approaches to treating insomnia.24 Despite these recommendations, many individuals with chronic insomnia do not receive these treatments. There are numerous reasons for this disparity, including an insufficient number of trained providers and difficulties with access to CBTs. The Veterans Administration (VA) has embarked on a national training initiative to close the gap between the need for insomnia treatment and the availability of skilled providers.25,26 An additional and relatively unexplored barrier is the acceptability of medication and nonmedication approaches among female veterans. To our knowledge, no research has explored which approach veterans might find most acceptable or whether there are subgroups of women (eg, older vs younger) who are most likely to prefer one approach over another.

Some literature suggests that patients who receive their preferred treatment have better outcomes. In 1 study27 investigating psychotherapy versus medication in the treatment of chronic major depressive disorder, patient preferences at baseline moderated treatment outcome such that patients who were randomized to the treatment they preferred had significantly higher remission rates and lower depression scores at posttreatment. In addition, a meta-analysis28 found that these patients were 3 times more likely to express a preference for psychological treatment versus pharmacologic treatment for psychiatric disorders, a finding that remained consistent across primary care and specialty care settings and was true across treatment-seeking and non–treatment-seeking groups. Importantly, this analysis also found that younger patients and women were significantly more likely to prefer psychological treatments than their older or male counterparts. Although treatment preferences for insomnia are largely unexplored, 1 study which investigated preferences among hospitalized patients on a geriatric assessment unit found that 82% of study participants believed that nondrug alternatives were healthier and that women were significantly more willing to consider nondrug alternatives than men.29 Taken together, these results indicate that female veterans may have a preference for psychological rather than pharmacologic interventions in the treatment of insomnia and that this preference may change with age.

Although there is evidence that women in particular may prefer nonmedication approaches, Jenkins et al6 reported that veterans with insomnia most frequently seek primary care services, and the setting in which veterans seek care for insomnia influences the type of treatment provided. Studies show that primary care providers are most likely to provide pharmacologic rather than behavioral treatment for insomnia.30 Thus, there may be a mismatch between female veterans’ preferences regarding insomnia treatment and the intervention they actually receive, which is likely to influence treatment outcome.

To maximize the match between patient preference and the care provided, it is important to know not only what those preferences are but also whether these preferences are associated with patient characteristics such as age, symptom severity, and psychiatric co-morbidities. Using data from a national survey of women veterans, the present study aimed to directly assess how acceptable female veterans find medication and nonmedication treatments for insomnia. First, we sought to determine the overall proportion of female veterans who find medication treatment for insomnia highly acceptable and to evaluate whether this acceptability varies as a function of age, severity of insomnia symptoms, other sleep characteristics, and psychiatric symptoms. Second, we sought to determine the proportion of female veterans who find nonmedication treatment for insomnia highly acceptable and whether this acceptability varies as a function of the same patient characteristics. Finally, we compared the acceptability of the 2 approaches and evaluated whether the relative preference for treatment modality varies as a function of the patient characteristics listed earlier.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design and Patient Population

Data for the present analyses were obtained from a large nationwide cross-sectional postal survey of insomnia among female veterans. The goals of the original study were to establish the national prevalence of insomnia among female veterans and to evaluate the acceptability of different insomnia treatment modalities. The survey included items asking a variety of questions about the respondent’s background as well as questions about sleep quality and treatment acceptability for sleep problems. Additional information about participants’ military service and utilization was obtained from administrative data sources. This analysis focused on 4 categories of variables: sleep quality, psychiatric symptoms, military experience, and treatment acceptability for sleep problems. Each of these sets of variables is described in detail in the following text.

The basic eligibility criteria for receiving the survey were having a valid address in the VA Health Eligibility Center (HEC) database and having received health care services at a VA facility in the previous 6 months. We obtained a database containing the names, addresses, and telephone numbers for all female veterans who met the eligibility criteria, which was imported into Stata version 13 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas). Invalid and duplicate cases were eliminated. A variable containing a random number was then created for each entry using the “runifrom()” function, and the cases were sorted based on this variable. The top 1000 cases formed the first batch of surveys, the second 1000 formed the second batch, and so forth, yielding 4 batches of 1000 surveys each. Surveys were sent from February through October 2013. Women who did not return a survey were sent a second copy ~3 weeks later, and an attempt was made to complete the same survey by telephone for women who were in the first cohort of 1000 mailed surveys. This additional step was conducted by a trained research staff member and was taken to reduce the potential for response bias in the final completed survey sample. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. A waiver of documentation of informed consent was obtained.

A total of 1559 surveys were returned by mail or completed by telephone, yielding a total response rate of 39%. Of the respondents, 1538 individuals had complete data for the current analyses.

Study Variables

Patient Characteristics

Date of birth (used to compute age) and military service experience (combat exposure and military sexual trauma) were obtained from the data provided by HEC. All other variables were collected within the survey: race, marital status, employment status, psychiatric symptoms, and self-reported sleep.

Self-reported Sleep

Information on sleep problems was assessed across 4 domains: sleep quality (hours of sleep, sleep efficiency, and sleep onset latency), duration of sleep problems, insomnia symptoms, and sleep apnea symptoms. In each domain, variables were dichotomized to facilitate comparison of treatment acceptability across subgroups of patients.

First, 4 items from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index31 (bedtime, rise time, total hours of sleep, and time to fall asleep) were used to calculate the following: (1) total sleep time, which was dichotomized as <7 hours versus ≥7 hours; (2) sleep efficiency (time asleep divided by time in bed multiplied by 100), which was dichotomized as <80% versus ≥80%; and (3) sleep onset latency, which was dichotomized as >30 minutes versus ≤30 minutes. Second, duration of sleep problems based on insomnia criteria from the International Classification of Sleep Disorders–Third Edition was categorized as follows: no sleep problems or problems lasting <3 months, 3 to 12 months, 1 to 5 years, 5 to 10 years, and >10 years. Third, we included the 7-item Insomnia Severity Index (ISI),32 calculated the total score, and categorized the findings according to published cutoffs: no clinically significant insomnia (0–7), subthreshold insomnia (8–14), moderate insomnia (15–21), and severe insomnia (22–28). Fourth, risk for obstructive sleep apnea was assessed by using the 4-item STOP Questionnaire.33 This questionnaire assesses 4 domains: snoring, daytime tiredness/sleepiness/fatigue, observed apneas, and presence of hypertension. Endorsement of ≥2 domains indicates high risk for sleep apnea; thus, a dichotomous outcome variable of ≥2 versus <2 was created.

Psychiatric Symptoms

Three domains of psychiatric symptoms were assessed: depression, anxiety, and PTSD. Depression and anxiety were assessed by using the 4-item Patient Health Questionnaire,34 which combines the 2-item Patient Health Questionnaire35 and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale–2.36 PTSD symptoms were assessed by using the Primary Care PTSD screen.37 Scores on each of these measures were dichotomized by using the clinical cutoffs (≥3 vs <3).

Military Service Experience

Time period of military service was assessed by using a checklist that included Operation New Dawn, the Global War on Terrorism (Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation Enduring Freedom), Desert Storm/Shield, the Vietnam War, the Korean War, World War II, peacetime, and other. Two additional variables regarding military service were obtained from the VA HEC database: documented combat exposure and documented military sexual trauma. The definition of military sexual trauma, as provided by US Code 1720D of Title 38, is psychological trauma, which, in the judgment of a VA mental health professional, resulted from a physical assault of a sexual nature, battery of a sexual nature, or sexual harassment that occurred while the veteran was serving on active duty or active duty for training.

Insomnia Treatment Acceptability

To assess treatment acceptability and treatment preferences, the 9-item Treatment Acceptability Scale38 was adapted for use in a postal survey format. A brief description of medication and nonmedication insomnia treatments were included within the survey (Figure 1) and respondents were then asked to rate the acceptability of each approach by using a Likert-type scale. The response options for each type of treatment included “not at all acceptable,” “a little acceptable,” “somewhat acceptable,” “very acceptable,” or “no opinion/don’t know.” These preference questions were then categorized as binary variables in which 1 indicated finding the treatment modality “very acceptable” and 0 indicated all other responses. We chose this relatively conservative definition for “acceptability” based on the notion that women would be most likely to access treatments they find “very acceptable” compared with other response categories.

Figure 1.

Description of medication treatment versus nonmedication treatment in the postal survey.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for all the aforementioned variables as well as for demographic characteristics of the sample. The mean and SD were computed for age, and frequencies were computed for the remaining variables (ie, self-reported sleep, psychiatric symptoms, military experience, treatment acceptability). Chi-square tests were used.

To test whether ratings of medication as very acceptable varied as a function of respondent characteristics, χ2 tests were also used.

Because each participant provided an acceptability rating of both medication treatment as well as non-medication treatment, a paired sample z test of proportions was performed to test the null hypothesis of no difference in the proportion rating medication and non-medication treatment as very acceptable. This test was performed for the entire sample. This same test was then repeated for each of the subgroups formed by self-reported sleep quality measures, psychiatric symptoms, military experience, and age group.

For all statistical tests, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed by using Stata software version 13 (Stata Corp).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

A total of 1538 female veterans had sufficiently complete surveys for the present analyses. Patient characteristics are shown in Table I. The mean (SD) age of study participants was 51.8 (14.6) years. Respondents indicated a variety of racial/ethnic backgrounds: 66.3% white, 26.5% African-American, 6.5% Hispanic/Latina, 2.9% American Indian/Alaska Native, and 1.7% Asian/Asian American. Many participants were married (41.6%); 31.6% were divorced/separated, 17.0% were single, and 7.3% were widowed.

Table I.

Patient characteristics (N = 1538*).

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 51.8 (14.6) |

| Age groups, no. (%) | |

| 18–29 y | 112 (7.3) |

| 30–39 y | 217 (14.1) |

| 40–49 y | 331 (21.5) |

| 50–59 y | 476 (31.0) |

| 60–69 y | 257 (16.7) |

| ≥70 y | 145 (9.4) |

| Race, no. (%)† | |

| White | 1008 (66.3) |

| African-American | 403 (26.5) |

| Hispanic/Latina | 95 (6.5) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 45 (2.9) |

| Asian/Asian American | 26 (1.7) |

| Marital status, no. (%)† | |

| Married | 632 (41.6) |

| Divorced/separated | 481 (31.6) |

| Widowed | 112 (7.3) |

| Single | 258 (17.0) |

| Employment status, no. (%)† | |

| Employed for wages | 628 (41.2) |

| Retired | 485 (31.8) |

| Unable to work | 330 (21.6) |

| Unemployed | 196 (12.9) |

| Student | 183 (12.0) |

| Homemaker | 157 (10.3) |

| Self-reported sleep | |

| Average bedtime (mean [SD] time) | 10:48 PM (105 min) |

| Average rise time (mean [SD] time) | 6:48 AM (116 min) |

| Total sleep time, mean (SD), h | 5.8 (1.7) |

| Total sleep time <7 h, no. (%) | 1085 (71.2) |

| Sleep efficiency (mean (SD)) | 73.3 (19.2) |

| Sleep efficiency <80%, no. (%) | 859 (56.8) |

| Time to fall asleep >30 min, no. (%) | 640 (42.1) |

| Duration of sleep problems, no. (%) | |

| No sleep problems | 246 (16.1) |

| <3 mo | 36 (2.4) |

| 3–12 mo | 82 (5.4) |

| 1–5 y | 460 (30.1) |

| 5–10 y | 280 (18.3) |

| >10 y | 427 (27.9) |

| Insomnia Severity Index, no. (%) | 19 (14.2) |

| No insomnia (0–7) | 387 (25.3) |

| Subthreshold (8–14) | 503 (32.8) |

| Moderate insomnia (15–21) | 451 (29.4) |

| Severe insomnia (22–28) | 191 (12.5) |

| STOP Questionnaire score ≥2, no. (%) | 755 (50.2) |

| Psychiatric symptoms, no. (%) | |

| PHQ, anxiety ≥3 | 553 (36.3) |

| PHQ, depression ≥3 | 461 (30.2) |

| PC-PTSD score ≥3 | 485 (31.9) |

| Military service experience, veteran, no. (%) | 1423 (93.5) |

| Period of military service, no. (%)† | |

| Global war on terrorism | 440 (29.0) |

| Desert Storm/Desert Shield | 512 (33.7) |

| Vietnam War | 288 (19.0) |

| Korean War | 37 (2.4) |

| World War II | 37 (2.4) |

| Peacetime | 526 (34.7) |

| Other | 131 (8.6) |

| Documented combat exposure, no. (%)‡ | 254 (16.5) |

| Documented military sexual trauma, no. (%)‡ | 354 (23.0) |

| Treatment preference for sleep problems, no. (%) | |

| Medication (very acceptable) | 508 (33.5) |

| Nonmedication (very acceptable) | 874 (57.7) |

PC-PTSD = Primary Care PTSD screen; PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire.

Valid N varies according to variable, from n = 1503 to n = 1538.

Multiple response options can be selected, and thus percentages do not sum to 100%.

Gathered from Department of Veterans Affairs administrative datasets.

Seventy-one percent of respondents reported short sleep duration (<7 hours), and more than one half reported a sleep efficiency <80%. Only 16% reported no sleep problems and 76% had sleep problems for at least 1 year. Approximately 42% of respondents reported clinically significant insomnia (based on ISI scores), and 50% screened as high risk for obstructive sleep apnea (based on STOP scores). Overall, 58% of respondents considered nonmedication treatment for insomnia to be very acceptable, and 34% of respondents considered medication treatment to be very acceptable.

Medication Treatment Acceptability by Patient Characteristics

Table II displays the percentage of respondents rating medication treatment as very acceptable as a function of patient characteristics: age, self-reported sleep, psychiatric symptoms, and military service experience. For example, Column A of Table II indicates that, among those who slept <7 hours, 35.1% rated medication as very acceptable; among those who slept ≥7 hours, 29.9% rated medication as very acceptable. The P value of the test of whether the proportion rating medication as very acceptable differed by total sleep time was P = 0.055. Although the percentage of participants rating medication treatment highly acceptable was greater in those who slept <7 hours than in those who slept ≥7 hours (35.1% vs 29.9%), this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.055).

Table II.

Acceptability of insomnia treatmenct modality (medication vs nonmedication) according to respondent characteristics.

| Respondent Characteristics | (A) Medication Treatment Very Acceptable

|

(B) Nonmedication Treatment Very Acceptable

|

(C) Difference in Treatment Acceptability (A–B [%])

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | P* | % | P† | % | P‡ | |

| Age group | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| 18–29 y | 30.4% | 63.1% | –32.7% | <0.001 | ||

| 30–39 y | 32.6% | 61.9% | –29.3% | <0.001 | ||

| 40–49 y | 40.7% | 66.3% | –25.6% | <0.001 | ||

| 50–59 y | 37.5% | 58.3% | –20.8% | <0.001 | ||

| 60–69 y | 28.6% | 51.0% | –22.4% | <0.001 | ||

| ≥70 y | 16.9% | 37.1% | –20.2% | <0.001 | ||

| Total sleep time | 0.055 | .689 | ||||

| <7 h | 35.1% | 58.2% | –23.1% | <0.001 | ||

| ≥7 h | 29.9% | 57.0% | –27.2% | <0.001 | ||

| Sleep efficiency | <0.001 | 0.728 | ||||

| >80% | 38.1% | 58.3% | –20.2% | <0.001 | ||

| ≥80% | 27.8% | 57.4% | –29.6% | <0.001 | ||

| Time to fall asleep | <0.001 | 0.041 | ||||

| >30 mins | 40.0% | 55.0% | –15.0% | <0.001 | ||

| ≤30 mins | 29.0% | 60.2% | –31.2% | <0.001 | ||

| Duration of sleep problems | <0.001 | 0.844 | ||||

| No sleep problems | 15.2% | 57.0% | –41.8% | <0.001 | ||

| <3 mo | 11.1% | 52.8% | –41.7% | <0.001 | ||

| 3–12 mo | 34.6% | 51.9% | –17.3% | 0.026 | ||

| 1–5 y | 31.7% | 59.1% | –27.3% | <0.001 | ||

| 5–10 y | 42.4% | 58.8% | –16.5% | <0.001 | ||

| >10 y | 41.8% | 57.8% | –15.9% | <0.001 | ||

| Insomnia Severity Index | <0.001 | 0.763 | ||||

| No insomnia | 19.7% | 59.9% | –40.2% | <0.001 | ||

| Subthreshold | 30.3% | 56.4% | –26.1% | <0.001 | ||

| Moderate insomnia | 39.6% | 57.9% | –18.3% | <0.001 | ||

| Severe insomnia | 56.1% | 56.8% | –0.8% | 0.559 | ||

| PHQ, Anxiety | <0.001 | 0.207 | ||||

| ≥3 | 44.9% | 55.5% | –10.6% | <0.001 | ||

| <3 | 27.1% | 58.9% | –31.8% | <0.001 | ||

| PHQ, Depression | <0.001 | 0.205 | ||||

| ≥3 | 47.6% | 55.2% | –7.6% | 0.021 | ||

| <3 | 27.4% | 58.7% | –31.6% | <0.001 | ||

| PC-PTSD | <0.001 | 0.584 | ||||

| ≥3 | 43.6% | 58.7% | –15.1% | <0.001 | ||

| <3 | 29.0% | 57.2% | –28.2% | <0.001 | ||

| Combat exposure | 0.018 | 0.510 | ||||

| Yes | 27.1% | 59.5% | –32.4% | <0.001 | ||

| No | 34.8% | 57.3% | –22.5% | <0.001 | ||

| Military sexual trauma | <0.001 | 0.425 | ||||

| Yes | 43.1% | 57.1% | –16.4% | <0.001 | ||

| No | 30.6% | 59.5% | –26.5% | <0.001 | ||

PC-PTSD = Primary Care PTSD screen; PHQ Patient Health Questionnaire.

The χ2 test of respondent characteristic by ratings of medication treatment as “very acceptable” (yes/no).

The χ2 test of respondent characteristic according to ratings of nonmedication treatment as “very acceptable” (yes/no).

Paired sample z test of percentage from column A versus percentage from column B.

Except for total sleep time, the percentage of respondents rating medication treatment very acceptable varied significantly as a function of all patient characteristics shown in Table II, including age, self-reported sleep, psychiatric symptoms, and military service experience (all, P ≤ 0.018).

Age

Acceptability of medication treatment varied significantly across age (Table II P < 0.001) with the highest acceptability in the group aged 40 to 49 years and a decreasing trajectory with advancing age.

Self-reported Sleep

Medication treatment was more likely to be highly acceptable for those whose sleep efficiency was <80% and whose sleep onset latency was >30 minutes compared with those with sleep efficiency ≥80% or sleep onset latency ≤30 minutes, respectively. Medication acceptability also varied as a function of sleep problem duration (P < 0.001); although the relationship is not perfectly monotonic, medication treatment acceptability tended to increase with greater duration of sleep problems.

Acceptability of medication treatment also increased as a function of insomnia severity. The more severe the insomnia symptoms (based on ISI score), the more likely women were to rate medication treatment as very acceptable (P < 0.001). Only 19.7% of women without insomnia rated this treatment as acceptable, whereas 56.1% of women with severe insomnia rated medication treatment highly acceptable.

Psychiatric Symptoms

Respondents who screened positive for anxiety, depression, and PTSD were significantly more likely to find medication treatment very acceptable than their counterparts who scored below clinical thresholds on these measures (all P < 0.001).

Military Service Experience

Veterans with documented combat exposure were less likely to find medication treatment acceptable (P = 0.018). Those patients with documented military sexual trauma were more likely to find medication treatment acceptable (P < 0.001).

Nonmedication Treatment Acceptability According to Patient Characteristics

Table II indicates the percentage of respondents rating nonmedication treatment very acceptable as a function of patient characteristics. In addition, Column B reports the P value of the test of whether the proportion of respondents rating nonmedication treatment as very acceptable varied according to each of the respondent characteristics. Rating nonmedication treatment very acceptable varied as a function of only 2 respondent characteristics: age and sleep onset latency. Acceptability of nonmedication treatment was highest in the group aged 40 to 49 years and decreased with advancing age (P < 0.001). Acceptability of nonmedication treatment was significantly lower in respondents whose sleep onset latency was >30 minutes (P = 0.041). There were no other significant differences in the acceptability of nonmedication insomnia treatment based on any other self-reported sleep variable, psychiatric symptoms, or military service experience.

Medication Versus Nonmedication Acceptability

Overall, 33.5% of respondents rated medication treatment as very acceptable, and 57.7% of respondents rated nonmedication treatment as very acceptable. The difference in these percentages is −24.1%, which is significantly different from zero (z = −13.3; P < 0.001). This outcome indicates that respondents were significantly less likely to find medication treatment acceptable compared with nonmedication treatment. In other words, nonmedication treatment was more likely to be acceptable than medication treatment.

Medication Versus Nonmedication Acceptability by Patient Characteristics

Table II indicates the difference in treatment acceptability (percentage who rated medication treatment very acceptable vs nonmedication treatment very acceptable) as a function of patient characteristics. In addition, Column C reports the P value of the test of whether this difference in treatment acceptability is different from zero. For example, among respondents aged 18 to 29 years, the difference in treatment acceptability was −32.7%, which is significantly different from zero (P < 0.001). In this group, respondents were significantly more likely to find nonmedication treatment highly acceptable than medication treatment.

In all but 1 of the subgroups, respondents favored nonmedication over medication treatment (all, P < 0.03). The exception was among those experiencing severe insomnia as measured by using the ISI (P = 0.559); in this group, there was no difference between acceptability of medication versus nonmedication treatment. There were no subgroups of respondents in which a larger proportion reported medication treatment highly acceptable than nonmedication treatment (Table II).

Age

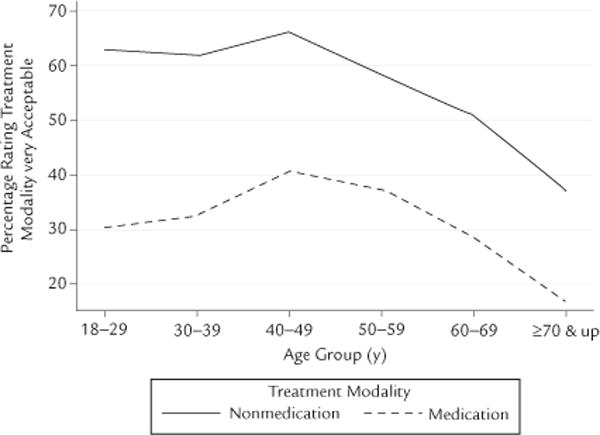

Figure 2 depicts the acceptability of medication treatment versus acceptability of nonmedication treatment as a function of age. Across all age groups, the difference in acceptability between the 2 types of insomnia treatment was statistically significant; however, the absolute difference in acceptability ratings was smaller among older respondents, suggesting that the preference for nonmedication treatment may be slightly attenuated in the oldest age groups and that women find both approaches less acceptable with advancing age.

Figure 2.

Acceptability of medication treatment and nonmedication treatment as a function of age.

DISCUSSION

The present results indicate that female veterans, regardless of age, are interested in treatment for insomnia. In this study, women were significantly more likely to rate nonmedication insomnia treatment as very acceptable (57.7%) compared with medication treatment (33.5%). With the exception of women with the most severe insomnia, this difference was consistent across all subgroups of women we considered. The pattern of responses indicated a preference for nonmedication approaches, regardless of age, military experience, presence of psychiatric symptoms, and reported sleep problems. Although this difference in acceptability was statistically significant across all age groups, the smallest difference was observed among female veterans aged ≥70 years (difference, 20.2%). This finding suggests that the preference for nonmedication approaches is slightly attenuated in older women. The reasons for this difference are not entirely clear; however, it is likely related to multiple factors, perhaps including previous experiences with medication and nonmedication treatments for other conditions. Because of changes in health status and increasing rates of chronic diseases typically managed with medications (eg, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia), older women may be more wary of seeking treatment at all for insomnia for fear of being given yet another medication to take. The overall pattern of results (Figure 2) also shows a downward trajectory in terms of acceptability of both treatments after age 50 years, which may be a reflection of changing beliefs about sleep among women after menopause. This finding is important and worthy of further investigation. It is conceivable that older women are less interested in treatment because they are more likely to attribute sleep problems to biological causes and, therefore, less likely to believe that any treatment will be effective. This theory would be in line with literature indicating that older patients with insomnia report more maladaptive beliefs and cognitions about sleep and express more hopelessness about sleep problems.9 Another possibility is that older female veterans are more accepting of sleep problems perhaps due to reduced daytime responsibilities, whereas younger women juggling the responsibilities of small children and jobs may be more distressed by the consequences of poor sleep (eg, daytime sleepiness) and, therefore, be more interested in receiving treatment. The survey used in the present study did not directly assess beliefs and attitudes about sleep problems, but this topic would be an interesting future line of investigation. Despite this subtle downward trajectory in treatment acceptability across age, a clear difference in acceptability of nonmedication treatment versus medication treatment was observed across all age groups.

Women with the most severe insomnia (ISI scores >22) were the only subgroup for whom there was no difference in the acceptability of medication versus non-medication treatment. This finding reflects an increase in the acceptability of medications rather than a decrease in the acceptability of nonmedication approaches. Although only 19.7% of women without insomnia symptoms found medications acceptable, 56% of women with severe insomnia found medication treatment acceptable, which was the only subgroup of women for whom a majority found medication treatment to be very acceptable. On the contrary, 59.9% of women without insomnia felt nonmedication treatment was acceptable and 56.8% of women with severe insomnia felt non-medication treatment was acceptable. Clinically, this suggests all women with insomnia should be offered nonmedication treatment and those with severe insomnia may also be interested in pharmacologic treatment. Importantly, acceptability of medication treatment was never significantly higher than acceptability of nonmedication treatment in any of the subgroups; however, in the subgroup in which insomnia symptoms were most severe, acceptability of medication treatment reached acceptability of nonmedication treatment.

There were differences in how acceptability of treatment varied across subgroups of respondents. Age was 1 of only 2 respondent characteristics (in addition to sleep onset latency >30 minutes) that predicted variability in rating nonmedication treatment as very acceptable and, as with medication treatment, the acceptability of nonmedication treatment decreased with age. Conversely, acceptability of medication treatment for insomnia varied as a function of almost all of the respondent characteristics such that those with more severe symptoms were more likely to find medications acceptable. Those who reported sleep efficiency <80%, sleep onset latency >30 minutes, longer duration of sleep problems, and greater ISI scores (indicating more severe insomnia) were significantly more likely to rate medication treatment as very acceptable. Those who scored above the clinical cutoff scores on screening measures of anxiety, depression, and PTSD were also significantly more likely to find medication acceptable. In terms of military service history, having an eligibility flag in the administrative database for combat exposure decreased the likelihood of finding medication treatment acceptable, whereas having an indication of military sexual trauma in the administrative database was associated with a higher likelihood of finding medication treatment acceptable.

There are some limitations to this study. There remains the possibility of response bias because participants self-selected to return the postal survey or agreed to complete the survey over the telephone; it is possible that individuals who completed the survey may differ from those who did not in terms of their sleep difficulties. However, it is unclear whether this potential response bias would affect the present findings given that participants were more likely to find nonmedication insomnia treatment acceptable regardless of whether or not they were experiencing insomnia symptoms. Another limitation is that the survey used in this study could not assess all potentially relevant domains. Specifically, it did not directly assess beliefs and attitudes regarding the etiology of sleep problems or beliefs and attitudes about the potential for any treatment to be effective. This information could be especially helpful in elucidating the downward trajectory in terms of acceptability of both treatments with age. Finally, the inclusion of multiple statistical comparisons creates the possibility that some findings are type I errors; however, given the overall pattern of systematic statistical differences, this possibility is unlikely to account for our findings in their entirety.

These results provide strong evidence for the acceptability of nonmedication treatment of insomnia among female veterans, regardless of age. According to the American Psychological Association and the American Psychiatric Association, when there is no evidence for the superiority of 1 treatment over the other, patient preference should guide selection of treatment. In this case, patient preferences align with current recommendations that CBT-I should be the first line of treatment given its effectiveness and enhanced durability compared with medications.39 Across multiple, randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses, CBT-I was efficacious, with therapeutic gains maintained long-term.23,40 Medications, conversely, have not been studied for long-term use and are not recommended unless other approaches are ineffective.24,41 CBT-I is an effective treatment, and female veterans are more likely to find behavioral treatment more acceptable than medication treatment. However, it is likely that most female veterans with insomnia either receive no treatment or receive medication treatment given that veterans are most likely to mention sleep complaints to primary care providers5 who are unlikely to have quick access to CBT-I providers and are more likely to provide pharmacologic treatment, which is readily available.30 These findings highlight the need for educating primary care providers within the VA about the effectiveness and availability of CBT-I in the treatment of insomnia as well as for further disseminating CBT-I to more providers who work with female veterans. Educating primary care providers about nonmedication approaches in general (and about CBT-I specifically) should accompany the VA’s national effort to increase veterans’ access to nonmedication insomnia treatments through training initiatives.

CONCLUSIONS

Female veterans are significantly more likely to find nonmedication insomnia treatment acceptable compared with medication treatment. This finding holds true regardless of age, self-reported sleep quality, psychiatric symptoms, and military service experience. Highly effective nonmedication treatment programs for insomnia, such as CBT-I, are available, and access to these treatments should continue to be enhanced. With advancing age, women are less likely to find either nonmedication or medication treatment very acceptable. Further investigation of why older women are less interested in insomnia treatment (medication and non-medication) is needed. If this finding is due to maladaptive attitudes and beliefs about sleep, it is important to provide these women with education regarding how sleep changes with age and the potential benefits of nonpharmacologic interventions, regardless of age. Even though older female veterans were less interested in insomnia treatment in general, they were still more likely to be interested in nonmedication treatment than medication treatment. There is a need to match female veterans who have sleep issues with the treatment modality they are most likely to find acceptable: non-medication treatment. Doing so may require further educating primary care providers regarding the efficacy of CBT-I and further disseminating CBT-I to a greater number of providers across multiple disciplines, particularly to those who work with older women.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported the VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI; RRP 12-189; Principal Investigator: Dr. Martin), Research Services of the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and VA-GLAHS Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center; VA Health Services Research and Development Service (Senior Research Career Scientist Award, RCS 05-195; Principal Investigator: Dr. Yano). Preparation of this publication was also supported by the Office of Academic Affiliations, Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors thank Julia Yosef, MA, RN, Simone Vukelich, and Sergio Martinez for their assistance with the study. They thank Terry Vandenberg, MA, posthumously, for her many contributions to this project as well.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in critical elements of this project: development of the survey questionnaire, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the paper for submission.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have indicated that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the content of this article.

The opinions stated in this work are the authors’ and do not represent the opinions of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.US Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. America’s Women Veterans: Military Service History and VA Benefits Utilization Statistics. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders-Third Edition (ICSD-3) 3rd. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang B, Wing YK. Sex differences in insomnia: a meta-analysis. Sleep. 2006;29:85–93. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenkins MM, Colvonen PJ, Norman SB, et al. Prevalence and Mental Health Correlates of Insomnia in First-Encounter Veterans with and without Military Sexual Trauma. Sleep. 2015;38:1547–1554. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin J, Hughes J, Jouldjian S, et al. Insomnia among women veterans: results of a postal survey. Sleep (Abstract Supplement) 2011:A314. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shochat T, Umphress J, Israel AG, AncoliIsrael S. Insomnia in primary care patients. Sleep. 1999;22(Suppl 2):S359–S365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morin CM, Stone J, Trinkle D, et al. Dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep among older adults with and without insomnia complaints. Psychol Aging. 1993;8:463–467. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.8.3.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leblanc MF, Desjardins S, Desgagne A. The relationship between sleep habits, anxiety, and depression in the elderly. Nat Sci Sleep. 2015;7:33–42. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S77045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Bixler EO, et al. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration is associated with a high risk for hypertension. Sleep. 2009;32:491–497. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.4.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Pejovic S, et al. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration is associated with type 2 diabetes: A population-based study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1980–1985. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mallon L, Broman JE, Hetta J. Sleep complaints predict coronary artery disease mortality in males: a 12-year follow-up study of a middle-aged Swedish population. J Intern Med. 2002;251:207–216. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.00941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leger D, Morin CM, Uchiyama M, et al. Chronic insomnia, quality-of-life, and utility scores: comparison with good sleepers in a cross-sectional international survey. Sleep Med. 2012;13:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leger D, Bayon V, Ohayon MM, et al. Insomnia and accidents: cross-sectional study (EQUINOX) on sleep-related home, work and car accidents in 5293 subjects with insomnia from 10 countries. J Sleep Res. 2014;23:143–152. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. 2011;135:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCall WV, Blocker JN, D’Agostino R, Jr, et al. Insomnia severity is an indicator of suicidal ideation during a depression clinical trial. Sleep Med. 2010;11:822–827. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riemann D, Voderholzer U. Primary insomnia: a risk factor to develop depression? J Affect Disord. 2003;76:255–259. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daley M, Morin CM, LeBlanc M, et al. The economic burden of insomnia: direct and indirect costs for individuals with insomnia syndrome, insomnia symptoms, and good sleepers. Sleep. 2009;32:55–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosekind MR, Gregory KB, Mallis MM, et al. The cost of poor sleep: workplace productivity loss and associated costs. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52:91–98. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181c78c30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobs GD, Pace-Schott EF, Stick-gold R, Otto MW. Cognitive behavior therapy and pharmacotherapy for insomnia: a randomized controlled trial and direct comparison. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1888–1896. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.17.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morin CM, Colecchi C, Stone J, et al. Behavioral and pharmacological therapies for late-life insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;281:991–999. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.11.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morin CM, Vallieres A, Guay B, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy, singly and combined with medication, for persistent insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:2005–2015. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Forciea MA, et al. Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:125–133. doi: 10.7326/M15-2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karlin BE, Trockel M, Taylor CB, et al. National dissemination of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in veterans: therapist-and patient-level outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81:912–917. doi: 10.1037/a0032554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manber R, Carney C, Edinger J, et al. Dissemination of CBTI to the non-sleep specialist: protocol development and training issues. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:209–218. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kocsis JH, Leon AC, Markowitz JC, et al. Patient preference as a moderator of outcome for chronic forms of major depressive disorder treated with nefazodone, cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy, or their combination. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:354–361. doi: 10.4088/jcp.08m04371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McHugh RK, Whitton SW, Peckham AD, et al. Patient preference for psychological vs pharmacologic treatment of psychiatric disorders: a meta-analytic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:595–602. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12r07757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Azad N, Byszewski A, Sarazin FF, et al. Hospitalized patients’ preference in the treatment of insomnia: pharmacological versus non-pharmacological. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;10:89–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simon GE, VonKorff M. Prevalence, burden, and treatment of insomnia in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1417–1423. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.10.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:812–821. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31816d83e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:613–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, co-morbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:317–325. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychiatry. 2003;9:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morin CM, Gaulier B, Barry T, Kowatch RA. Patients’ acceptance of psychological and pharmacological therapies for insomnia. Sleep. 1992;15:302–305. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.4.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitchell MD, Gehrman P, Perlis M, Umscheid CA. Comparative effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edinger JD, Wohlgemuth WK, Radtke RA, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment of chronic primary insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:1856–1864. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.14.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.NIH State-of-the-Science Conference Statement on manifestations and management of chronic insomnia in adults. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2005;22:1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]