Abstract

Expression of fission yeast glycerophosphate transporter Tgp1 is repressed in phosphate-rich medium and induced during phosphate starvation. Repression is enforced by transcription of the nc-tgp1 locus upstream of tgp1 to produce a long noncoding (lnc) RNA. Here we identify two essential elements of the nc-tgp1 promoter: a TATA box −30TATATATA−23 and a HomolD box −64CAGTCACA−57, mutations of which inactivate the nc-tgp1 promoter and de-repress the downstream tgp1 promoter under phosphate-replete conditions. The nc-tgp1 lncRNA poly(A) site maps to nucleotide +1636 of the transcription unit, which coincides with the binding site for Pho7 (1632TCGGACATTCAA1643), the transcription factor that drives tgp1 expression. Overlap between the lncRNA template and the tgp1 promoter points to transcriptional interference as the simplest basis for lncRNA repression. We identify a shorter RNA derived from the nc-tgp1 locus, polyadenylated at position +508, well upstream of the tgp1 promoter. Mutating the nc-tgp1-short RNA polyadenylation signal abolishes de-repression of the downstream tgp1 promoter elicited by Pol2 CTD Ser5Ala phospho-site mutation. Ser5 mutation favors utilization of the short RNA poly(A) site, thereby diminishing transcription of the lncRNA that interferes with the tgp1 promoter. Mutating the nc-tgp1-short RNA polyadenylation signal attenuates induction of the tgp1 promoter during phosphate starvation. Polyadenylation site choice governed by CTD Ser5 status adds a new level of lncRNA control of gene expression and reveals a new feature of the fission yeast CTD code.

Keywords: phosphate homeostasis, polyadenylation, CTD code

INTRODUCTION

Phosphate homeostasis in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe is achieved by an intricate network of positive and negative influences on the transcription of genes encoding three proteins involved in extracellular phosphate mobilization and uptake: a cell surface acid phosphatase Pho1, an inorganic phosphate transporter Pho84, and a glycerophosphate transporter Tgp1 (Carter-O'Connell et al. 2012). These genes are repressed during growth in phosphate-rich medium and induced during phosphate starvation. Induction of the phosphate-regulated genes is dependent on transcription factor Pho7 (Henry et al. 2011; Carter-O'Connell et al. 2012). Repression of pho1 under phosphate-replete conditions is itself an active process involving protein kinases Csk1 and Cdk9, and the phosphorylation of the carboxyl-terminal domain (CTD) of the Rpb1 subunit of RNA polymerase II (Pol2) (Carter-O'Connell et al. 2012; Schwer et al. 2014, 2015; Chatterjee et al. 2016).

Recent studies have unveiled a role for long noncoding (lnc) RNAs in phosphate-regulated expression of the pho1 and tgp1 genes. The prt lncRNA, initiating 1147 nucleotides (nt) upstream of the pho1 mRNA transcription start site, represses pho1 in cis during phosphate-replete growth (Lee et al. 2013; Shah et al. 2014; Schwer et al. 2015; Chatterjee et al. 2016). pho1 expression from the prt–pho1 locus is inversely correlated with the activity of the prt promoter, which resides in a 110-nt DNA segment preceding the prt transcription start site. Within the prt promoter, there are two elements that dictate its strength: (i) a TATA box (−37TATATATA−30) that is essential for prt transcription; and (ii) an upstream segment from −110 to −62 that augments prt transcription (Chatterjee et al. 2016). The positive contributions of the upstream segment stem, at least in part, from the presence of a HomolD sequence (−75CAGTCACG−68). Manipulations of the prt promoter in the context of the prt–pho1 locus that either delete the upstream DNA segment or mutate the TATA box cause de-repression of pho1 in phosphate-replete cells. Unlike pho1, expression of prt is independent of Pho7 (Schwer et al. 2015). The pho1 promoter resides within a 283-nt DNA segment upstream of the mRNA start site and its activity depends on two tandem dodecamer sequences [consensus motif 5′-TCG(G/C)(A/T)xxTTxAA] that are binding sites for the Pho7 transcription factor (Chatterjee et al. 2016; Schwer et al. 2017).

In the case of tgp1, the lncRNA nc-tgp1, initiating 1865 nt upstream of the tgp1 AUG start codon (Fig. 1A), represses tgp1 in cis during phosphate-replete growth (Ard et al. 2014). tgp1 is de-repressed when the nc-tgp1 locus is disrupted either by deleting the nc-tgp1 transcription start site and upstream flanking DNA (embracing the putative nc-tgp1 promoter) or by inserting a ura4+ cassette (in reverse orientation) into the 5′ end of the nc-tgp1 transcription unit (Ard et al. 2014). The cis and trans factors that control nc-tgp1 transcription are presently unknown. However, it is clear that prt and nc-tgp1 lncRNA levels are restrained by the action of the nuclear exosome; they increase sharply when the Rrp6 nuclear exosome subunit is absent. The turnover of these lncRNAs by the exosome is aided by Mmi1 (Ard et al. 2014; Shah et al. 2014), a YTH domain-containing protein that recognizes determinants of select removal (DSR) in the target RNA (Harigaya et al. 2006; Yamashita et al. 2012; Chatterjee et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2016).

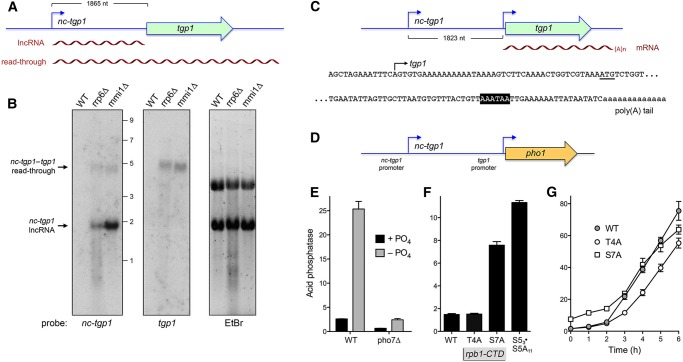

FIGURE 1.

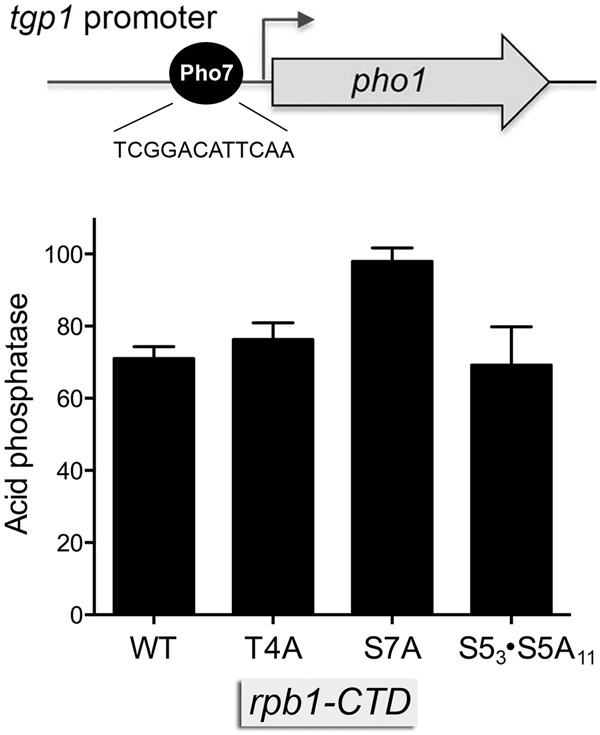

Transcripts derived from the nc-tgp1 and tgp1 loci and plasmid reporter for dissection of nc-tgp1 control of tgp1 expression. (A) The tandem nc-tgp1–tgp1 locus is shown with the nc-tgp1 transcription start site indicated by the blue arrow and the tgp1 ORF depicted as a green bar with arrowhead indicating the direction of transcription. The distance between the nc-tgp1 transcription initiation site and the ATG translation start site of the tgp1 ORF is indicated by the bracket. The two nc-tgp1 transcripts detected by northern analysis (in panel B) are depicted as wavy lines below the DNA. (B) Northern blotting. Total RNA from wild-type (WT), rrp6Δ, and mmi1Δ cells was resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis, and ethidium bromide-stained ribosomal RNAs (EtBr, right panel) were visualized prior to transfer of the gel contents to membrane, which was hybridized to 32P-labeled nc-tgp1 (left panel) and tgp1 (middle panel) DNA probes. The positions and sizes (kb) of RNA size markers are indicated on the left panel. (C) tgp1 mRNA. The nc-tgp1–tgp1 locus is shown with the distance between the nc-tgp1 and tgp1 transcription initiation sites indicated by the bracket. The DNA sequence surrounding the tgp1 transcription start site (mapped by primer extension and indicated by the black arrow) is shown on the top line; the tgp1 ATG translation start codon is underlined. The cDNA sequence including and preceding the poly(A) tail of the tgp1 mRNA is shown on the bottom line; the consensus poly(A) signal is highlighted in white on black background. (D) The plasmid-borne nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter cassette is shown with the mapped transcription start sites of the nc-tgp1 lncRNA and tgp1 mRNA indicated by arrows. The pho1 ORF is depicted as a gold bar with arrowhead. (E) The nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 plasmid was introduced into pho1Δ yeast cells that were either pho7+ (WT) or pho7Δ. Cells grown for 3 h in synthetic medium containing 15.5 mM phosphate (+PO4) or in medium lacking exogenous phosphate (−PO4) to elicit the starvation response were assayed for acid phosphatase activity by conversion of p-nitrophenylphosphate to p-nitrophenol. The y-axis specifies the phosphatase activity (A410) normalized to input cells (A600). The error bars denote SEM. (F) CTD mutations de-repress regulated tgp1 expression during phosphate-replete growth. The nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter plasmid was introduced into pho1Δ cells in which the rpb1 chromosomal locus was replaced by alleles rpb1-CTD-WT, CTD-T4A, CTD-S7A, or CTD-S53S5A11. Cells grown in phosphate-replete medium were assayed for acid phosphatase activity. (G) Time course of the phosphate starvation response. The indicated CTD strains bearing the nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter plasmid were assayed for acid phosphatase activity immediately prior to and at hourly intervals after transfer to medium lacking exogenous phosphate.

Whereas there are divergent views on the role of heterochromatin in the lncRNA-mediated repression of fission yeast phosphate-responsive genes, the simplest model is that transcription of the upstream lncRNA in cis is what interferes with expression of the downstream genes encoding Pho1 or Tgp1 in phosphate-replete cells, likely by displacing the Pho7 transcription factor from the pho1 and tgp1 promoter DNAs (Ard et al. 2014; Chatterjee et al. 2016). By extension, the simplest view of the response to phosphate starvation is that it causes cessation of lncRNA transcription across the downstream gene promoter (in a manner as yet uncharted) and alleviates the downstream interference.

We are interested in elucidating the signals that affect this dynamic during phosphate starvation and in the role of the Pol2 CTD in establishing or overriding the repressed state imposed by lncRNA synthesis. Here we focus on the repression of tgp1 by nc-tgp1. We address the following questions: (i) What comprises the nc-tgp1 promoter? (ii) Does nc-tgp1 promoter strength correlate with tgp1 repression? (iii) How do CTD phospho-site mutations affect nc-tgp1 and tgp1 expression? (iv) Does mutating DSR-like elements in the nc-tgp1 RNA affect tgp1 phosphate-responsiveness? (v) Is there a connection between nc-tgp1 lncRNA 3′ end formation and tgp1 promoter activity?

In the course of answering these questions, we identified a novel short polyadenylated RNA derived from the nc-tgp1 transcription unit and found that mutation of its polyadenylation signal abolished the de-repression of the downstream tgp1 promoter elicited by CTD Ser5Ala phospho-site mutation. Ser5Ala promotes utilization of the short RNA poly(A) site located upstream of the tgp1 promoter, thereby diminishing transcription of the lncRNA that overlaps and interferes with the tgp1 promoter. We find that mutating the nc-tgp1-short RNA polyadenylation signal attenuates induction of the tgp1 promoter during phosphate starvation. Polyadenylation site choice responsive to Pol2 CTD status comprises a new means of lncRNA control of gene expression.

RESULTS

Two transcripts derived from the nc-tgp1 locus

Northern analysis of total RNA from phosphate-replete wild-type S. pombe cells using nc-tgp1 and tgp1 probes failed to detect transcripts from either locus. In contrast, in a mmi1Δ strain, bearing a mei4 mutation that suppresses the lethality of mmi1Δ (Sugiyama and Sugioka-Sugiyama 2011), we detected two discrete transcripts that hybridized to the nc-tgp1 probe: a ∼1.9 kb RNA corresponding to the nc-tgp1 lncRNA; and a ∼4.6 kb RNA that extended through the tgp1 gene and was therefore recognized by the tgp1-specific probe (Fig. 1A,B). The nc-tgp1 lncRNA and the nc-tgp1–tgp1 read-through transcript were also detectable by northern analysis of RNA from rrp6Δ cells (Fig. 1B). A transcript corresponding to the ∼2.5 kb tgp1 mRNA (Ard et al. 2014) was not detected in phosphate-replete mmi1Δ or rrp6Δ cells, affirming that tgp1 is tightly repressed during growth in phosphate-rich medium (more so than pho1, which is expressed at a basal level in phosphate-replete cells).

tgp1 mRNA initiation and polyadenylation sites

Reverse transcriptase primer extension analysis located the 5′ end of the tgp1 mRNA to a single site 42 nt upstream of the start codon of the tgp1 open reading frame (Fig. 1C; Schwer et al. 2017). Thus, the tgp1 mRNA transcription start site is 1823 nt downstream from the nc-tgp1 lncRNA initiation site (Fig. 1C). Here we mapped the site of polyadenylation of the tgp1 mRNA by 3′ RACE using as template total RNA isolated from phosphate-starved wild-type cells. Sequencing of 14 individual cDNA clones revealed that 43% (6/14) had the identical junction to a poly(A) tail at a site 2102 nt downstream from the tgp1 transcription start site (Fig. 1C). The dominant tgp1 poly(A) site is located 19 nt downstream from a fission yeast AAAUAA polyadenylation signal (Fig. 1C; Mata 2013). Seven additional poly(A) junctions, six recovered once and one recovered twice among the 14 cDNA clones, were distributed within a 277-nt segment (Supplemental Fig. S1). The most proximal poly(A) site was located 1940 nt downstream from the transcription start site, and the most distal poly(A) site was situated 2216 nt from the transcription start site. The most distal poly(A) site is preceded by two tandem fission yeast AAUAAA polyadenylation signals (Supplemental Fig. S1; Mata 2013).

We also performed 3′ RACE analysis using RNA isolated from phosphate-replete mmi1Δ cells that express the nc-tgp1–tgp1 read-through transcript. Of 13 individual cDNA clones sequenced, four had a poly(A) tail at the position corresponding to the dominant poly(A) site of the tgp1 mRNA (Supplemental Fig. S2). Four of the cDNA clones had a poly(A) tail at the position corresponding to the most distal poly(A) site of the tgp1 mRNA (Supplemental Fig. S2). The majority of the poly(A) sites of the nc-tgp1–tgp1 read-through transcript (9/13) were downstream from fission yeast polyadenylation signals. Five other poly(A) junctions were each recovered once (Supplemental Fig. S2), two of which were identical to “singlet” poly(A) sites detected by 3′ RACE of the tgp1 mRNA.

The tgp1 gene is annotated in Pombase (www.pombase.org) as containing a putative 46-nt intron interrupting the 3′ end of a predicted open reading frame that, assuming the intron is spliced out in the mature tgp1 mRNA, would encode a predicted polypeptide of 543 amino acids. Our 3′ RACE analysis of the tgp1 mRNA from phosphate-starved fission yeast, which used sense strand primers corresponding to sequences 5′ of the predicted intron, yielded polyadenylated cDNA clones that, in every case (14/14), contained the 46-nt segment thought to comprise an intron (Supplemental Fig. S1). We conclude that this element is not a bona fide intron and is not spliced out during phosphate starvation, the only time when tgp1 mRNA is known to be transcribed. (The 46-nt segment is also retained in all of the 13 cDNA clones obtained by 3′ RACE of the nc-tgp1–tgp1 read-through transcript in phosphate-replete mmi1Δ cells [Supplemental Fig. S2].) The corrected 1584-nt open reading frame in the tgp1 mRNA encodes a 528-aa protein (Supplemental Fig. S1) that contains a C-terminal Lys528 instead of a C-terminal 16-aa peptide that would have been encoded had the intron been spliced.

Plasmid-based reporter assay to study regulated expression of tgp1

Whereas the regulation of pho1 expression is conveniently studied by measuring acid phosphatase enzyme activity on the surface of live yeast cells, analyses of tgp1 expression have relied on steady-state tgp1 RNA levels. Because our goal here was to dissect what drives nc-tgp1 lncRNA expression and its influence on tgp1 transcription, we developed a plasmid-based reporter system inspired by the recently described prt–pho1 plasmid reporter, which recapitulated the features of regulated pho1 expression that had been determined for the chromosomal prt–pho1 locus (Chatterjee et al. 2016). As depicted in Figure 1D, we isolated a fragment of the nc-tgp1–tgp1 locus, spanning 301 nt upstream of the nc-tgp1 transcription initiation site (encompassing the putative nc-tgp1 promoter) and the entire 1865 nt segment between the nc-tgp1 transcription start site and the tgp1 translation start codon (containing the putative tgp1 promoter), and fused it to the pho1 ORF and its native 3′ flanking DNA. We cloned the nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter cassette into a fission yeast plasmid, which we then introduced into a pho1Δ strain in which the chromosomal pho1 gene had been deleted. Plasmid-bearing pho1Δ cells grown to mid-log phase in liquid culture in phosphate-replete YES medium were washed and then incubated for 3 h in synthetic medium containing 15.5 mM phosphate (+PO4) or in medium lacking exogenous phosphate (−PO4) to elicit the starvation response. Acid phosphatase activity was quantified by incubating suspensions of serial dilutions of the cells for 5 min with p-nitrophenylphosphate and assaying colorimetrically the formation of p-nitrophenol. Product formation in the linear response range, normalized to cell density, is plotted on the y-axis in Figure 1E. The low basal phosphatase activity of nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 cells in phosphate-replete medium was increased 10-fold after 3 h of phosphate starvation. Moreover, the basal activity and the starvation response of the nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter was attenuated in a pho7Δ strain that lacks the Pho7 transcription factor. Thus, the plasmid-borne DNA element containing the nc-tgp1 gene and the tgp1 transcription start site suffices to confer phosphate-regulated expression of the acid phosphatase reporter.

Effect of CTD phospho-site mutations on regulated tgp1 expression

Previous studies had shown that repression of pho1 expression from the prt–pho1 locus (in either chromosomal or plasmid contexts) in phosphate-replete cells is affected by Pol2 CTD phosphorylation status, as gauged by the impact of CTD mutations that eliminate particular phosphorylation marks (Schwer et al. 2014, 2015; Chatterjee et al. 2016). For example, inability to place a Ser7-PO4 mark in S7A cells de-repressed pho1. Limiting the number of serine-5 CTD sites to three consecutive Ser5-containing CTD heptads also de-repressed pho1. In contrast, inability to place a Thr4-PO4 mark in T4A cells hyper-repressed pho1 under phosphate-replete conditions. Here, to test the impact of these CTD mutations on regulated tgp1 expression, we introduced the nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter plasmid into pho1Δ cells in which the rpb1 chromosomal locus was replaced by alleles rpb1-CTD-WT, -CTD-T4A, -CTD-S7A, or -CTD-S53•S5A11 (Schwer and Shuman 2011; Schwer et al. 2012). Whereas the T4A allele had no effect on nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter activity in phosphate-replete cells, the S7A and S53•S5A11 CTD variants elicited fivefold and eightfold increases in activity compared to the wild-type CTD (Fig. 1F).

The time dependence of the phosphate starvation response of the nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter in the rpb1-CTD-WT, -CTD-T4A, and -CTD-S7A strains was monitored by scoring acid phosphatase activity immediately prior to and at hourly intervals after transfer of the cells to medium lacking exogenous phosphate (Fig. 1G). The onset of acid phosphatase accumulation in T4A cells occurred with a slight delay (≤1 h) compared to rpb1-CTD-WT, though the slope of the increase was similar in both strains. Whereas the S7A strain started with a higher basal level of acid phosphatase prior to phosphate starvation, the time course of induction of the nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter was similar to that of T4A cells.

nc-tgp1 transcription: What comprises a nc-tgp1 promoter?

To address this question, we constructed a plasmid reporter in which the pho1 ORF was fused immediately downstream from a genomic DNA segment containing nucleotides −301 to +6 of the nc-tgp1 transcription unit (Fig. 2A). Because this plasmid generated vigorous acid phosphatase activity when introduced into a pho1Δ strain (Fig. 2B), we surmised that the 301-nt segment embraces a nc-tgp1 promoter and potential regulatory elements. Absence of the Pho7 transcription factor had no effect on the activity of the nc-tgp1•pho1 reporter (Fig. 2C). To demarcate cis-acting elements, we serially truncated the 5′ flanking DNA to positions −211, −134, −98, −71, and −55 upstream of the nc-tgp1 transcription start site. The acid phosphatase activity of the plasmid-bearing pho1Δ cells (Fig. 2B) indicated that the 5′ flanking 134-nt segment sufficed for nc-tgp1 promoter-driven expression. Truncation to −98 and −71 reduced acid phosphatase activity to 52% and 40% of that driven by the −134 promoter; further truncation to −55 effaced acid phosphatase activity (Fig. 2B). To query whether CTD mutations influence nc-tgp1 promoter-driven transcription, we introduced the -301 nc-tgp1•pho1 reporter plasmid into the pho1Δ rpb1-CTD-WT, -CTD-T4A, -CTD-S7A, and -CTD-S53•S5A11 strains and measured acid phosphatase expression (Fig. 2D). nc-tgp1 promoted pho1 activity was identical in the WT and S53•S5A11 strains, from which we conclude that the de-repression of the nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter in S53•S5A11 cells was not caused by a decrease in transcription from the nc-tgp1 lncRNA promoter. The nc-tgp1•pho1 reporter activity in T4A and S7A cells was 25% and 35% higher than that in WT cells, respectively (Fig. 2D).

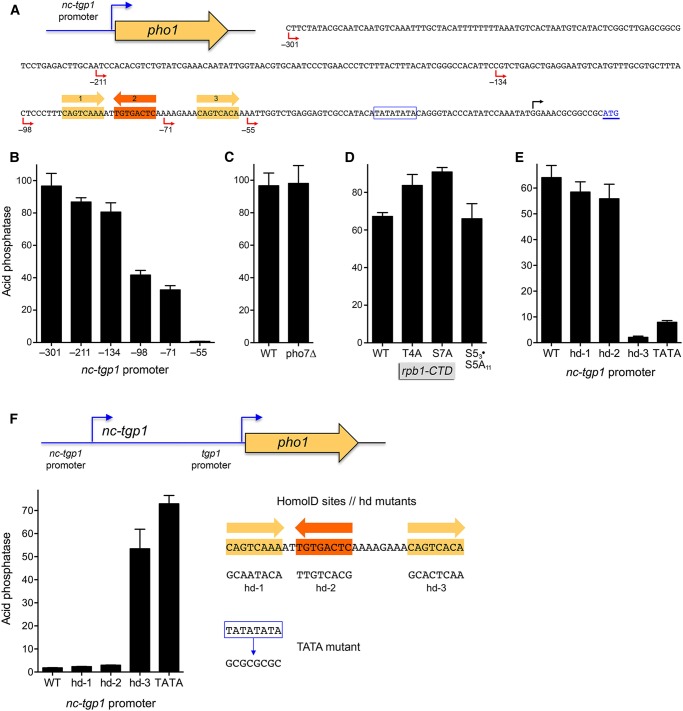

FIGURE 2.

HomolD and TATA boxes are essential for nc-tgp1 promoter activity and regulation of tgp1. (A) Plasmid reporter of nc-tgp1 promoter activity. The pho1 ORF (beginning at the underlined ATG translation initiation codon in blue font) was fused downstream from a fragment of genomic DNA containing the nc-tgp1 transcription start site (indicated by the black arrow above the DNA sequence) and 301 nt of 5′ flanking nc-tgp1 DNA (presumed to include the nc-tgp1 promoter). Serial truncations of the upstream margin of the 5′ flanking nc-tgp1 DNA were made at positions −211, −134, −98, −71, and −55 (indicated by red arrows below the DNA sequence) relative to the nc-tgp1 transcription start site. A putative TATA element is outlined by a blue box. Three putative HomolD elements are shaded in gold (forward orientation) or orange (reverse orientation). (B) Acid phosphatase activity of pho1Δ cells bearing the indicated nc-tgp1 promoter-driven pho1 reporter plasmids. (C) Acid phosphatase activity of pho1Δ pho7+ (WT) and pho1Δ pho7Δ cells bearing the −301 nc-tgp1 promoter-driven pho1 plasmid. (D) Acid phosphatase activity of pho1Δ rpb1-CTD strains bearing the −301 nc-tgp1–pho1 plasmid. (E,F) The indicated mutated versions of individual HomolD sites (hd-1, hd-2, and hd-3) and the TATA box of the nc-tgp1 promoter (shown at right in panel F) were introduced into the −301 nc-tgp1•pho1 reporter and phosphate-replete pho1Δ cells bearing the indicated nc-tgp1•pho1 reporter plasmids were assayed for acid phosphatase activity (panel E). (F) The HomolD and the TATA box mutations of the nc-tgp1 promoter were introduced into the nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter plasmid (shown at the top of the panel). Phosphate-replete pho1Δ cells bearing the indicated reporter plasmids were assayed for acid phosphatase activity.

HomolD and TATA boxes are essential for nc-tgp1 promoter activity

The sequence of the 301-nt DNA segment flanking the nc-tgp1 start site is shown in Figure 2A. The promoter deletion analysis suggested the presence of an essential transcriptional element in the interval between −56 and −71 and a stimulatory element located between −72 and −134. Our inspection of these segments disclosed three sequences that are potential HomolD-box elements (shaded yellow and orange in Fig. 2A). The consensus HomolD element 5′-CAGTCAC(A/G) functions as a Pol2 promoter signal in fission yeast, especially in genes encoding ribosomal proteins (Witt et al. 1993, 1995; Gross and Käufer 1998). The HomolD sequence is a binding site for the essential fission yeast transcription factor Rrn7 (Rojas et al. 2011). The putative HomolD box closest to the nc-tgp1 transcription start site (−64CAGTCACA−57; box 3 in Fig. 2A) is a perfect match to the HomolD consensus sequence. The candidate HomolD element furthest from the start site (−90CAGTCAAA−83; box 1 in Fig. 2A) deviates by one nucleobase from the consensus sequence. Putative box 2 (−80TGTGACTC−73), situated between boxes 1 and 3 in the opposite orientation, is a single-base variant GAGTCA CA of the HomolD consensus (Fig. 2A). Our previous studies of the prt–pho1 locus implicated a HomolD box as a driver of prt lncRNA transcription and its ensuing repression of pho1 during phosphate-replete growth (Chatterjee et al. 2016).

Here, to evaluate whether any of the HomolD boxes play a role in lncRNA regulated tgp1 expression, we introduced into the nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter multiple nucleotide changes, at six out of eight positions in box 1, or at seven out of eight positions in boxes 2 or 3 (Fig. 2F). pho1Δ cells transformed with the mutated nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporters hd-1, hd-2, and hd-3 were grown in phosphate-replete medium and tested for acid phosphatase activity in parallel with cells bearing the WT nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 plasmid. Whereas mutations hd-1 and hd-2 had no effect on the phosphate-repressive state of the nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 locus, the hd-3 mutation elicited a de-repression of reporter activity, to a level 29-fold higher than the WT control (Fig. 2F). To judge whether this apparent loss of phosphate regulation was caused by a change in the activity of the nc-tgp1 promoter, we introduced the hd-1, hd-2, and hd-3 mutations into the nc-tgp1•pho1 reporter plasmid (Fig. 2E). The salient findings were that whereas hd-1 and hd-2 mutations had no significant effect, nc-tgp1 promoter activity was lowered 30-fold by the hd-3 mutation (Fig. 2E). We conclude that HomolD box 3 is an essential component of the nc-tgp1 promoter and that down-regulation of nc-tgp1 promoter-driven lncRNA transcription by its mutation leads to increased activity of the downstream tgp1 promoter in phosphate-replete cells.

The nc-tgp1 promoter also contains a TATA box sequence −30TATATATA−23. To query the role of the TATA element in nc-tgp1 function, we introduced a TATA mutant (GCGCGC GC) into the nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter and found that it (akin to the hd-3 mutant) resulted in a 40-fold increase in acid phosphatase activity under phosphate-replete conditions (Fig. 2F) that correlated with an eightfold decrement in the activity of the nc-tgp1 promoter (Fig. 2E). Thus, the TATA box, too, is a key determinant of nc-tgp1 promoter function and phosphate repression of the flanking tgp1 promoter.

Effect of CTD mutations on tgp1 promoter activity

To interrogate the tgp1 promoter, we constructed a plasmid reporter in which a genomic DNA segment containing nucleotides −871 to +42 of the tgp1 transcription unit (with +1 being the mRNA start site) was fused to the pho1 ORF (Fig. 3). This plasmid generates vigorous acid phosphatase activity when introduced into a pho1Δ strain (Schwer et al. 2017). Acid phosphatase activity driven by the tgp1 promoter reporter plasmid is reduced by 85% either: (i) in a pho7Δ strain background; or (ii) by mutation of the Pho7 DNA binding site 5′-TCGGACATTCAA located at nucleotides −192 to −181 upstream of the tgp1 transcription start site (Schwer et al. 2017). The effects of CTD mutations on the activity of the tgp1•pho1 reporter are shown in Figure 3. Activity was nearly identical in the rpb1-CTD WT, T4A, and S53•S5A11 strains. Thus, the de-repression of the nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 locus seen in S53•S5A11 cells is not reflective of increased activity of the tgp1 promoter per se. Whereas tgp1 promoter-driven Pho1 expression in S7A was 38% higher than in WT cells, this effect is much less than the fivefold increase in expression of Pho1 from the nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter elicited by the S7A allele.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of rpb1-CTD mutations on tgp1 promoter activity. A schematic of the -871 tgp1 promoter-driven pho1 reporter (Schwer et al. 2017) is shown at the top, with the Pho7 binding site in the tgp1 promoter highlighted. Acid phosphatase activity of pho1Δ rpb1-CTD-WT, rpb1-CTD-T4A, rpb1-CTD-S7A, and rpb1-CTD-S53S5A11 cells bearing the tgp1•pho1 reporter plasmid is shown.

Effect of mutating DSR sequences in the nc-tgp1 lncRNA

Ard et al. (2014) noted that the nc-tgp1 RNA contains a cluster of three putative DSR sequences in the region from nucleotides +821 to +850 (highlighted in gold in Fig. 4A). Tandem DSRs promote RNA degradation via their recognition by the YTH-domain protein Mmi1. The canonical DSR hexanucleotide sequence is 5′-U(U/C)AAAC (Yamashita et al. 2012). The first and third hexanucleotides in the putative DSR cluster of the nc-tgp1 lncRNA conform to the UCAAAC consensus; the middle hexanucleotide is a single-base variant UUAAAA (Fig. 4A). It was shown previously that certain variant DSR hexanucleotide motifs can augment the function of the consensus DSR element to promote RNA elimination (Yamashita et al. 2012). However, 5′-UUAAAA was not among the variant motifs tested. We have shown that the Mmi1 YTH domain binds equally well to RNA containing either a consensus UUAAAC hexamer or a UUAAAU variant (Chatterjee et al. 2016). Inspection of the nc-tgp1 RNA sequence revealed three UUAAAU sequences and two UUAAAC sequences (highlighted in green in Fig. 4A) in addition to the DSR cluster.

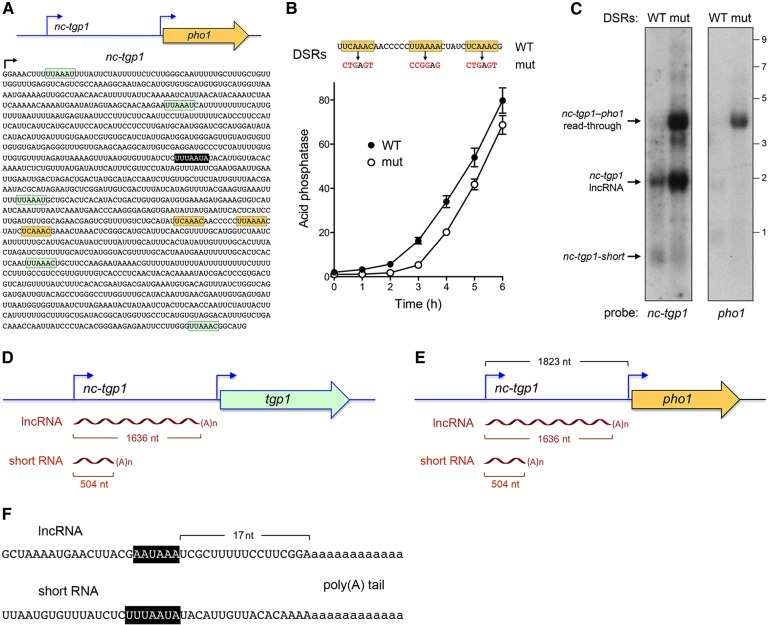

FIGURE 4.

Characterization of the nc-tgp1 lncRNA and a novel nc-tgp1 short RNA. (A) The nucleotide sequence of the first 1395 nt of the nc-tgp1 lncRNA is shown. A cluster of three putative DSR sequences in the region from nucleotides +821 to +850 is highlighted in gold. Other DSR hexamers are highlighted in green. The polyadenylation signal for the nc-tgp1-short RNA is shown in white font on black background. (B) Phosphate starvation response. The indicated mutated version of the +821 to +850 DSR cluster (mut) was introduced into the nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter plasmid shown in panel A. Yeast pho1Δ cells bearing the DSR WT or mut nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 plasmids were assayed for acid phosphatase activity immediately prior to and at hourly intervals after transfer to medium lacking exogenous phosphate. (C) Northern blotting. Total RNA from pho1Δ cells bearing the DSR WT or mut nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 plasmids was resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis, transferred to membrane, and probed with 32P-labeled nc-tgp1 (left panel) and pho1 (right panel) DNAs. The positions and sizes (kb) of RNA size markers are indicated on the right. (D–F) Mapping the 3′ ends of the polyadenylated nc-tgp1 lncRNA by 3′ RACE of RNA from mmi1Δ cells expressing nc-tgp1 from the native chromosomal locus (panel D; sequencing three independent cDNA clones), and pho1Δ cells expressing nc-tgp1 from the nc-tgp1(DSR-WT)–tgp1•pho1 and nc-tgp1(DSR-mut)–tgp1•pho1 reporter plasmids (panel E; sequencing two and four independent cDNA clones, respectively). (D–F) Mapping the 3′ ends of the polyadenylated nc-tgp1-short RNA by 3′ RACE of RNA from cells expressing nc-tgp1 from the native chromosomal locus (sequencing 10 independent cDNA clones), and pho1Δ cells expressing nc-tgp1 from the nc-tgp1(DSR-WT)–tgp1•pho1 and nc-tgp1(DSR-mut)–tgp1•pho1 reporter plasmids (sequencing 15 and 2 independent cDNA clones, respectively). (F) The lncRNA and short RNA sequences preceding the poly(A) tails are shown. Poly(A) nucleotides are depicted in lower case font. A canonical fission yeast polyadenylation signal is shown in white font on black background.

To evaluate the role of the +821 to +850 DSR cluster in tgp1 regulation, we introduced compound mutations (at five out of six positions) into each of the three hexanucleotide motifs of the nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter (Fig. 4B). We gauged the effect of the DSR cluster mutation on the responsiveness to phosphate starvation, as reflected in the induction of acid phosphatase activity as a function of time after transfer to medium lacking phosphate. DSR mutation delayed the onset of acid phosphatase production by 1 h, but did not affect the rate of acid phosphatase production thereafter (Fig. 4B).

Northern analysis of RNA isolated from phosphate-replete pho1Δ cells bearing the wild-type nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter plasmid showed that the ∼1.9 kb nc-tgp1 lncRNA was detectable, but the downstream pho1 mRNA was not (Fig. 4C). We also detected a ∼0.7-kb transcript that was recognized by the nc-tgp1 probe, which we refer to henceforth as nc-tgp1-short. (The ability to detect by northern blot the lncRNA, and the short RNA, expressed from the plasmid, but not from the chromosomal nc-tgp1 locus [Fig. 1B], likely reflects the high copy number of the fission yeast plasmid.) The salient finding was that the DSR cluster mutation elicited an increase in the abundance of the nc-tgp1 lncRNA as well as the accumulation of a ∼4 kb nc-tgp1–pho1 read-through transcript that annealed to the nc-tgp1 and pho1 probes. These findings implicate the DSR cluster as a determinant of the stability of the nc-tgp1 lncRNA, and its propensity to terminate without read-through into the downstream gene. Note that the level of the nc-tgp1-short RNA was not increased by the DSR cluster mutation, presumably because the short transcript terminates upstream of the DSR cluster.

Defining the 3′ end of the polyadenylated nc-tgp1 lncRNA

We mapped the site of polyadenylation of the nc-tgp1 lncRNA by 3′ RACE using as template total RNA isolated from two cellular sources that have 1.9 kb lncRNAs detectable by northern analysis: (i) mmi1Δ cells expressing nc-tgp1 from the native chromosomal locus (Fig. 1B, 4D); and (ii) pho1Δ cells expressing nc-tgp1 from the nc-tgp1(DSR-WT)–tgp1•pho1 reporter and nc-tgp1(DSR-mut)–tgp1•pho1 reporter plasmids (Fig. 4C,E). Sequencing of three, two, and four independent cDNA clones from these RNA sources, respectively, revealed (in all nine cases) identical junctions to a poly(A) tail at nucleotide 1636 of the lncRNA transcript, which is situated 17 nt downstream from a fission yeast AAUAAA polyadenylation signal (Fig. 4F; Mata 2013). Thus, the same polyadenylated lncRNA is produced from the native nc-tgp1–tgp1 locus (Fig. 4D) and the nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter (Fig. 4E). The cleavage/poly(A) site of the nc-tgp1 lncRNA (5′-UCGGA↓) is located 187 nt upstream of the tgp1 transcription start site, within the sequence that corresponds to the Pho7 DNA binding site of the tgp1 promoter (5′-TCGGA↓CATTCAA). Thus, transcription across the poly(A) site of the nc-tgp1 lncRNA excludes (or displaces) Pho7 binding at the tgp1 promoter.

Defining the 3′ end of the polyadenylated nc-tgp1-short RNA

We mapped the site of polyadenylation of the nc-tgp1-short RNA by 3′ RACE using as template total RNA isolated from yeast cells (not containing a plasmid) expressing nc-tgp1 from its natural context in the chromosome (10 independent cDNA clones sequenced), from pho1Δ cells expressing nc-tgp1 from the wild-type nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter plasmid (15 independent cDNA clones sequenced), and from pho1Δ cells expressing nc-tgp1 from the nc-tgp1(DSR-mut)–tgp1•pho1 reporter plasmid (two independent cDNA clones sequenced). The RACE analysis revealed identical junctions in all 27 cases to a poly(A) tail at nucleotide 504–508 of the nc-tgp1-short transcript, the ambiguity being that the poly(A) tail overlaps with four consecutive templated A nucleotides (Fig. 4F). The short RNA poly(A) site is situated downstream from overlapping fission yeast UUUAAU and UUAAUA polyadenylation signals (Fig. 4F; Mata 2013).

Mutating the poly(A) signal of the nc-tgp1-short RNA abolishes de-repression of the tgp1 promoter by CTD S5A mutation

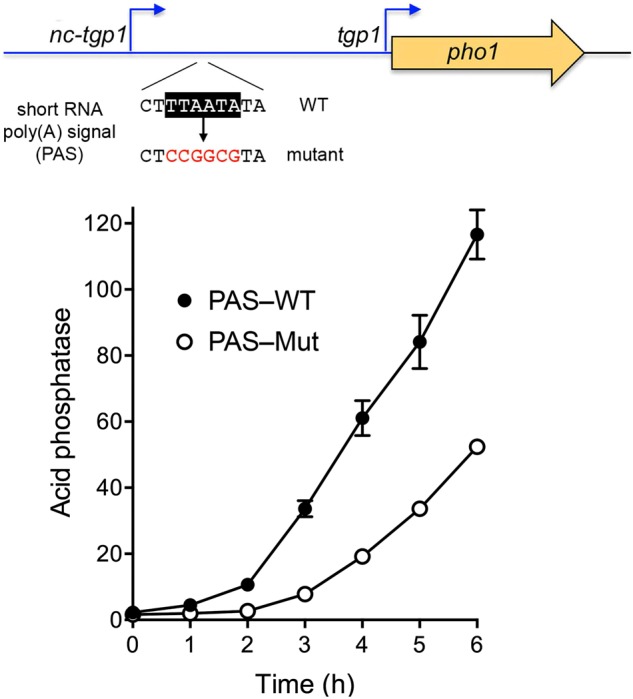

Our detection of a novel short poly(A)+ RNA derived from the nc-tgp1 gene adds a new wrinkle to the nc-tgp1 story. Most pertinent is the fact that Pol2 elongation complexes synthesizing the nc-tgp1-short RNA will undergo nascent strand 3′ cleavage, and (in all likelihood) ensuing transcription termination (Loya and Reines 2016) well upstream of the Pho7 binding site of the tgp1 promoter [which coincides with the lncRNA poly(A) site] (Fig. 4D). This scenario raises the prospect that poly(A) site choice might modulate lncRNA activity. For example, a change in poly(A) site choice skewed toward nc-tgp1-short might contribute to the observed de-repression of the downstream tgp1 promoter in phosphate-replete cells with S53•S5A11 phospho-site mutations in the Pol2 CTD (Fig. 1F). If this is the case, then we would expect that the de-repressive effects of this CTD allele on the tgp1 promoter in the nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter should be effaced by mutation of the nc-tgp1-short RNA polyadenylation signal (PAS). Indeed, this was precisely what occurred when we changed the nc-tgp1-short PAS in the DNA template from TTAATA (wild-type) to CCGGCG (mutant) (Fig. 5A) and gauged tgp1 promoter-driven acid phosphatase expression in phosphate-replete S53•S5A11 cells (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that the reduction in CTD Ser5 phospho-sites exerts its de-repressive effect via the nc-tgp1-short PAS.

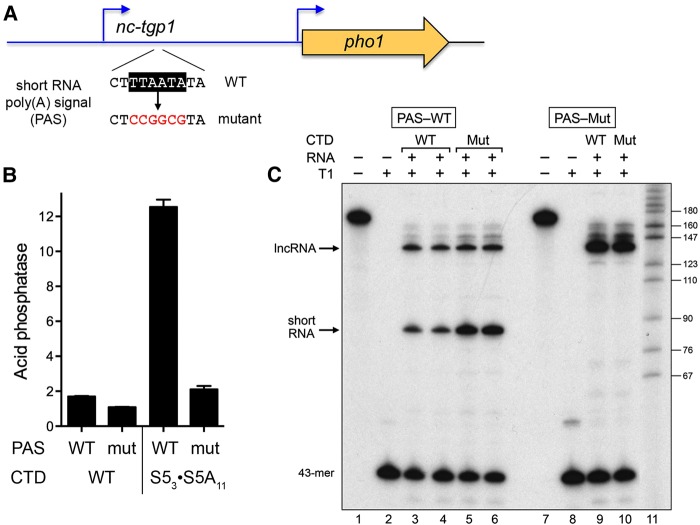

FIGURE 5.

Mutating the poly(A) signal of the nc-tgp1-short RNA abolishes de-repression of the tgp1 promoter by CTD S5A mutation. (A) The short RNA polyadenylation signal (PAS) in the nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter cassette (highlighted in white font on black background) was replaced by the mutant sequence shown in red font below the wild-type PAS. (B) Acid phosphatase activity of pho1Δ rpb1-CTD-WT or rpb1-CTD-S53S5A11 cells bearing nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter plasmids with wild-type (WT) or mutant (mut) short RNA PAS elements. (C) RNase protection analysis of nc-tgp1-short PAS utilization in rpb1-CTD-WT cells (CTD WT; lanes 3,4,9) or rpb1-CTD-S53S5A11 cells (CTD Mut; lanes 5,6,10) bearing nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter plasmids with wild-type (PAS–WT; lanes 3–6) or mutant (PAS-Mut; lanes 9,10) short RNA PAS elements was performed as described in Materials and Methods. The RNase T1-digested samples (T1+) and untreated controls (T1−; lanes 1,7) were analyzed by denaturing PAGE. The positions and lengths (nt) of radiolabeled DNA size markers (lane 11) are indicated on the right.

To directly assess poly(A) site choice, we performed RNase probe protection analysis of RNA isolated from rpb1-CTD-WT and -S53•S5A11 cells bearing the nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter with a wild-type or mutant nc-tgp1-short PAS. The 170-nt wild-type 32P-UMP-labeled RNA probe (Fig. 5C, lane1) is complementary to the wild-type nc-tgp1 lncRNA throughout a 133-nt segment that spans the 3′ cleavage/polyadenylation site of the nc-tgp1-short RNA. RNase T1 cleavage of any probe annealed to lncRNA yields a 138-nt protected fragment; cleavage of probe annealed to the polyadenylated nc-tgp1-short RNA yields a shorter 86-nt protected fragment (Fig. 5C, lanes 3–6). Protection of these two fragments from T1 digestion depended on prior annealing to RNA from cells bearing the PAS-WT reporter (Fig. 5C, lane 2). The presence in all RNase digests of a 43-nt T1-resistant fragment corresponding to the longest interval between G nucleotides of the labeled probe (lanes 3–6), affirmed that the probe was present in excess over the complementary cellular nc-tgp1 RNAs. The probe protection analysis revealed that utilization of the short PAS site increased in the rpb1-CTD-S53•S5A11 strain (lanes 5,6) vis à vis the wild-type (lanes 3,4). The ratio of the nc-tgp1-short to lncRNA T1-protected fragments is a measure of nc-tgp1-short PAS choice. The short RNA/lncRNA ratio values (mean ± SEM of RNA preparations from three independent yeast cultures, with two technical replicates of the RNase protection for each RNA sample) were 0.955 ± 0.03 for the rpb1-CTD-WT strain and 1.92 ± 0.03 for the rpb1-CTD-S53•S5A11 strain. Control experiments using a probe complementary to the nc-tgp1 transcript with the mutant nc-tgp1-short PAS (lane 7) affirmed that the PAS mutation effaced the shorter protected species and yielded exclusively a signal for the nc-tgp1 lncRNA (Fig. 5C, lanes 9,10).

Mutating the poly(A) signal of the nc-tgp1-short RNA attenuates the tgp1 phosphate starvation response

We gauged the effect of the inactivating TTAATA (wild-type) to CCGGCG (mutant) change in the nc-tgp1-short RNA PAS on the kinetics of tgp1 promoter-driven acid phosphatase expression from the nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter during phosphate starvation. The PAS mutation elicited a delay in the onset of Pho1 accumulation and a decrement in the rate of Pho1 production during the 6 h interval after transfer of the cells to phosphate-free medium (Fig. 6), e.g., such that the acid phosphatase activity of PAS-Mut cells at 5 h post-starvation was equivalent to the activity of PAS-WT cells after 3 h of starvation. These results imply that transcription from the nc-tgp1 promoter persists during phosphate starvation (at least during the time frame analyzed) to an extent that a nc-tgp1-short PAS mutation, which biases toward nc-tgp1 lncRNA synthesis, significantly blunts tgp1 promoter activity. The fact that a PAS mutation does not completely prevent tgp1 promoter induction during phosphate starvation suggests that there is also a component of nc-tgp1 promoter down-regulation in phosphate homeostasis.

FIGURE 6.

Mutating the poly(A) signal of the nc-tgp1-short RNA attenuates the induction of the tgp1 promoter during phosphate starvation. Cells bearing the nc-tgp1–tgp1•pho1 reporter in which the nc-tgp1-short RNA polyadenylation signal (PAS) was either wild-type or mutant were assayed for acid phosphatase activity immediately prior to and at hourly intervals after transfer to medium lacking exogenous phosphate.

DISCUSSION

lncRNA repression of phosphate-starvation genes in fission yeast

Fission yeast phosphate homeostasis entails repressing the tgp1 and pho1 genes during phosphate-replete growth and inducing/de-repressing them under conditions of phosphate starvation. Here we contribute to an emerging appreciation of the role of lncRNAs transcribed co-directionally from upstream nc-tgp1 and prt genomic loci flanking tgp1 and pho1 in enforcing the repressive status, in particular by delineating shared features that govern transcription of the nc-tgp1 and prt lncRNAs. Within the nc-tgp1 promoter, there are two essential elements: a HomolD box (−64CAGTCACA−57) and a TATA box (−30TATATATA−23). We find that mutations in either the HomolD or TATA sequences in the context of the nc-tgp1–tgp1 reporter result in de-repression of the tgp1 promoter in phosphate-replete cells. HomolD and TATA elements are also present and positioned similarly in the prt lncRNA promoter, where they are important for prt-dependent repression of pho1 expression (Chatterjee et al. 2016), and in the promoter for the S. pombe U3 snoRNA (Nabavi and Nazar 2008).

Our results focus attention on the HomolD element as a likely target of phosphate responsiveness, whereby HomolD functions positively in nc-tgp1 lncRNA transcription when phosphate is available, presumably via binding of an activating transcription factor to the HomolD sequence. Because loss of nc-tgp1 and prt transcription suffices to de-repress tgp1 and pho1, the simplest model for phosphate starvation-induced tgp1 and pho1 expression is that starvation elicits a signaling pathway that eventually shuts off the nc-tgp1 and prt promoters (Ard et al. 2014; Chatterjee et al. 2016), conceivably by an inactivating modification of the transcription factor that recognizes HomolD in the lncRNA promoters. Maldonado and colleagues have shown that the HomolD sequence is recognized by the essential fission yeast transcription factor Rrn7 (Rojas et al. 2011) and that phosphorylation of Rrn7 by casein kinase 2 (CK2) inhibits its ability to bind to HomolD DNA in vitro (Moreira-Ramos et al. 2015). By mutating three predicted CK2 phosphorylation sites in Rrn7 to alanine, they showed that (i) replacing Thr67 with alanine uniquely eliminated its CK2 phosphorylation in vitro; and (ii) binding of Rrn7-T67A to HomolD DNA was unaffected by CK2 (Moreira-Ramos et al. 2015). We reasoned that if Rrn7 Thr67 phosphorylation during phosphate starvation is the basis for shut-off of HomolD-driven lncRNA transcription, then prevention of such phosphorylation by T67A mutation might block the starvation induction of phosphate-responsive genes. Therefore, we disrupted the native S. pombe rrn7+ gene in a diploid strain by insertion of a ura4+ marker and introduced a mutant rrn7-T67A allele at the leu1 locus. After sporulation to obtain a haploid rrn7::ura4+ leu1::rrn7-T67A strain, we verified that the rrn7-T67A strain grew as well as rrn7+ on YES medium. Testing for induction of Pho1 phosphatase activity upon shift to phosphate-free medium showed no effect of rrn7-T67A on the extent of Pho1 accumulation (not shown), leading us to surmise that Rrn7 Thr67 phosphorylation is not a decisive event in the phosphate starvation response.

Our experiments illuminate key properties of the nc-tgp1 lncRNA. For example, whereas it had been noted earlier that the lncRNA contains a cluster of three DSR-like hexanucleotide elements that are recognized by Mmi1 (Ard et al. 2014; Kilchert et al. 2015), the contribution of these DSRs to regulated tgp1-driven transcription was not addressed. Here we showed that mutating the DSR cluster resulted in a higher steady-state level of the nc-tgp1 lncRNA and the accumulation of a longer read-through transcript spanning the lncRNA and the downstream tgp1 promoter-driven pho1 reporter. (These effects of nc-tgp1 DSR mutations on the plasmid reporter echoed those of mmi1Δ on the chromosomally transcribed nc-tgp1 lncRNA and nc-tgp1–tgp1 read-through RNA.) The lack of effect of the DSR mutations on the activity of the downstream tgp1 promoter in phosphate-replete cells simply reflects the fact that the tgp1 promoter is already maximally repressed by transcription of the wild-type nc-tgp1 lncRNA. However, the DSR mutations do elicit a 1 h delay in the induction of tgp1 promoter-driven expression after phosphate starvation. In contrast, DSR cluster mutations in the prt lncRNA cause a significant decrement in the basal level of Pho1 expression in phosphate-replete cells and they cause a longer 2-h delay in the induction of Pho1 after phosphate starvation (Chatterjee et al. 2016).

The poly(A) site of the nc-tgp1 lncRNA is located 187 nt upstream of the tgp1 transcription start site and directly overlaps the binding site for transcription factor Pho7 in the tgp1 promoter (Fig. 4D). The salient point here is that Pol2 elongation complexes synthesizing the nc-tgp1 lncRNA will fully traverse the tgp1 promoter. Thus, the simplest model for repression posits that nc-tgp1 lncRNA synthesis interferes with tgp1 promoter function by displacing Pho7 from the promoter DNA, via collision with Pol2 traveling on the segment of the nc-tgp1 template that includes the Pho7 recognition site. An alternative view is that lncRNA transcription causes changes in chromatin status over the tgp1 promoter (albeit not via heterochromatin) that interfere with Pho7 binding (Ard and Allshire 2016). These views are not mutually exclusive, e.g., displacement of Pho7 by Pol2 transcribing nc-tgp1 could incite changes in nucleosome density over the tgp1 promoter.

Comparison to regulated SER3 expression in budding yeast

The repression of the phosphate-responsive tgp1 gene in fission yeast by transcription of an upstream lncRNA echoes themes established for regulated SER3 expression in S. cerevisiae, whereby SER3 is tightly repressed during growth in rich medium via transcription of the upstream SRG1 lncRNA so as to interfere with the SER3 promoter (Martens et al. 2004). As seen here for nc-tgp1: (i) The size of the polyadenylated SRG1 lncRNA is such that its 3′ end overlaps the SER3 promoter; and (ii) mutation of the TATA box in the SRG1 promoter de-represses SER3 (Martens et al. 2004). SRG1 transcription is regulated by serine availability, i.e., SRG1 is turned on under serine-rich conditions and shut off in response to acute serine starvation, with SER3 expression anti-correlating to that of SRG1 (Martens et al. 2004). Whereas fission yeast nc-tgp1 lncRNA expression is driven by a HomolD element in its promoter, the cognate transcription factor(s) of which remain unclear absent genetic evidence for a role of Rrn7, budding yeast SRG1 expression is activated by a DNA element that contains a binding site for transcription factor Cha4 (Martens et al. 2005). Deletion of Cha4 suppresses SRG1 expression and consequently de-represses SER3 in serine-rich medium (Martens et al. 2005). It is noteworthy that budding yeast Cha4 is a member of the Zn2Cys6 family of fungal transcription regulators (Holmberg and Schjerling 1996), as is S. pombe Pho7 (Schwer et al. 2017). Thus, whereas budding yeast deploys a Zn2Cys6 factor to transcribe the lncRNA and thereby enforce the repressive state of the flanking gene, fission yeast uses a Zn2Cys6 factor to transcribe the flanking target gene once the repressive effect of the lncRNA is alleviated.

Influence of nc-tgp1-short RNA and CTD status

A short poly(A)+ RNA derived from the nc-tgp1 gene adds another layer of control to the system. The poly(A) site of the nc-tgp1-short RNA is located 504–508 nt from the transcription start site, well upstream of the DSR cluster present in the lncRNA. Pol2 elongation complexes that synthesize the nc-tgp1-short RNA are expected to terminate transcription well upstream of the Pho7 site of the tgp1 promoter. Thus, transcription of the nc-tgp1-short RNA would not elicit repression of the downstream tgp1 gene, which raised a hypothesis that poly(A) site choice might figure in the regulation of lncRNA function. Indeed, we show here that poly(A) site choice biased toward nc-tgp1-short contributes to the de-repression of the downstream tgp1 promoter in phosphate-replete cells bearing S5A mutations in the Pol2 CTD, and that de-repression of the tgp1 promoter by the rpb1-CTD-S53•S5A11 allele is eliminated by mutation of the nc-tgp1 short RNA poly(A) signal. In the same vein, the de-repression of the tgp1 promoter by rpb1-CTD-S7A (Fig. 1F) is also eliminated by mutation of the nc-tgp1 short RNA poly(A) signal (not shown). We find that mutation of the nc-tgp1-short RNA poly(A) signal attenuates induction of the downstream tgp1 promoter in phosphate-starved cells, both with respect to the lag time to see an increase in gene expression (gauged by acid phosphatase reporter activity) and the rate of acid phosphatase accumulation.

Finally, our results reveal a new aspect of the fission yeast CTD code, in which the Ser5 phospho-site (and presumably its phosphorylation) disfavors a proximal poly(A) site in the nc-tgp1 transcription unit, whereas reducing available Ser5 phospho-sites by S5A mutation enhances proximal poly(A) site choice. Recent studies by the Bachand laboratory have implicated the fission yeast protein Seb1 in the regulation of cotranscriptional PAS selection in coding and noncoding genes (Lemay et al. 2016; Larochelle et al. 2017). Seb1 is an RNA binding protein, essential for vegetative growth, that recognizes a 5′-(A/U)GUA(A/G) motif situated 50- to 100-nt downstream from sites of cleavage/polyadenylation (Lemay et al. 2016). Seb1 also interacts with the Pol2 CTD, though available evidence weighs against a role for the Ser5-PO4 mark in Seb1 recruitment and function (Lemay et al. 2016). Of note, whereas there are three distinct Seb1 motifs within the 100-nt segment downstream from the cleavage/polyadenylation site of the nc-tgp1 lncRNA, there are, in contrast, no Seb1 motifs flanking the cleavage/polyadenylation site of the nc-tgp1-short RNA (i.e., the nearest GUA sequence is 466 nt downstream from the short RNA cleavage/polyadenylation site). These considerations militate against Seb1 as an agent of Ser5-regulated usage of the nc-tgp1-short poly(A) site.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reporter plasmids

We constructed three sets of pho1-based reporter plasmids, marked with a kanamycin-resistance gene (kanMX), in which the expression of Pho1 acid phosphatase was driven by either: (i) a tandem nc-tgp1(promoter+lncRNA)-tgp1(promoter) element; (ii) a nc-tgp1(promoter) element; (iii) or a tgp1(promoter) element. These were derivatives of pKAN-(pho1) described previously (Chatterjee et al. 2016) generated by insertion of genomic sequences flanking pho1, as follows. Plasmid pKAN-(nc-tgp1–tgp1prom•pho1) includes a fragment of the nc-tgp1–tgp1 locus, spanning 301 nt upstream of the nc-tgp1 transcription initiation site (encompassing the putative nc-tgp1 promoter) and the entire 1865-nt segment between the nc-tgp1 transcription start site and the tgp1 translation start codon (containing the putative tgp1 promoter) fused to the pho1 ORF and its native 3′ flanking DNA. Plasmid pKAN-(nc-tgp1prom•pho1) includes the 301 nt upstream of the nc-tgp1 transcription initiation site fused to the pho1 ORF and its native 3′ flanking DNA. Plasmid pKAN-(tgp1prom•pho1) includes the 913-nt segment upstream of the tgp1 translation start codon fused to the pho1 ORF and its native 3′ flanking DNA. Serial truncations from the 5′ end of the nc-tgp1 promoter were generated by PCR amplification and cloned into the pKAN-(nc-tgp1prom•pho1) reporter in lieu of the original promoter segment. Nucleotide substitutions were introduced into the reporter constructs by two-stage overlap extension PCR amplification with mutagenic primers, followed by insertion in lieu of the wild-type DNA segments. The inserts of all plasmids were sequenced to exclude unwanted mutations.

Reporter assays

Reporter plasmids were transfected into pho1Δ cells (Chatterjee et al. 2016). kanMX transformants were selected on YES (yeast extract with supplements) agar medium containing 150 µg/mL G418. Single colonies of transformants (≥20) were pooled and grown at 30°C in plasmid-selective liquid medium. Aliquots of exponentially growing cultures were harvested, washed, and suspended in water to attain A600 of 1.25 or 2.5. To quantify acid phosphatase activity, reaction mixtures (200 µL) containing 100 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.2), 10 mM p-nitrophenylphosphate, and cells (ranging from 0.01 to 1 A600 units) were incubated for 5 min at 30°C. The reactions were quenched by adding 1 mL of 1 M sodium carbonate; the cells were removed by centrifugation, and the absorbance of the supernatant at 410 nm was measured. Acid phosphatase activity is expressed as the ratio of A410 (p-nitrophenol production) to A600 (cells). Each datum in the graphs is the average (±SEM) of phosphatase assays using cells from at least three independent cultures. To test the responsiveness of Pho1 expression to phosphate starvation, cells transformed with pKAN-(nc-tgp1–tgp1prom•pho1) were grown in YES+G418 liquid medium, aliquots of exponentially growing cultures were harvested, washed in water, and adjusted to A600 of ∼0.3 in PMG (phthalate medium glutamate) +G418 liquid medium without phosphate. After incubation for various times at 30°C, cells were harvested, washed, and assayed for acid phosphatase activity as described above.

RNA analyses

Total RNA was extracted via the hot phenol method from 20 A600 units of yeast cells that had been grown at 30°C in YES, YES + G418 (for selection of kanMX plasmids), or PMG without phosphate. The RNAs were treated with DNase I, extracted serially with phenol:chloroform and chloroform, and then precipitated with ethanol. The RNAs were resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 1 mM EDTA. For northern blotting, equivalent amounts (10 µg) of total RNA were resolved by electrophoresis through a 1.2% agarose/formaldehyde gel. After photography under UV illumination to visualize ethidium-bromide-stained 18S and 28S rRNAs, the gel contents were transferred to a Hybond-XL membrane (GE Healthcare). Gene-specific probes were prepared by radiolabeling DNA fragments of the tgp1 (nucleotides 151–1064), nc-tgp1 (nucleotides 1–1141), or pho1 (nucleotides 590–1293) genes. Hybridization was performed as previously described (Herrick et al. 1990) and the hybridized probes were visualized by autoradiography.

For amplification of cDNA 3′ ends, we used the 3′ RACE Kit (Invitrogen). In brief, 2 µg of total RNA was used as template for first strand cDNA synthesis by SuperScript II RT and an oligo(dT) adapter primer (AP). The RNA template was removed by digestion with RNase H, and the cDNA was then diluted 10-fold for amplification by PCR using gene-specific forward primers and an abridged universal reverse primer (AUAP). The PCR products were gel-purified, cloned into a pCRII TOPO vector by using the TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen). Plasmid DNAs isolated from individual bacterial transformant colonies were sequenced. cDNAs were deemed to be “independent” when they contained different lengths of poly(dA) at the cloning junction.

Assay of nc-tgp1 poly(A) site choice by RNase protection

To generate RNA probes for hybridization, a 134-bp DNA fragment (from nucleotides +424 to +558 of the nc-tgp1 transcription unit) spanning the poly(A) site of wild-type nc-tgp1-short RNA was amplified by PCR using primers that introduced restriction sites for cloning into the pGEM1 vector. An equivalent fragment containing the mutated polyadenylation signal was also cloned into pGEM1. The plasmids were linearized and used as templates for the in vitro synthesis of 32P-UMP labeled anti-sense transcripts by T7 RNA polymerase. The RNAs were gel-purified and aliquots (3–4 × 104 cpm) were coprecipitated with 10 µg of total RNA from pKAN-(nc-tgp1–tgp1prom•pho1)-bearing pho1Δ rpb1-CTD-WT or rpb1-CTD-S53•S5A11 cells. After ethanol precipitation, the RNA pellets were dissolved in 20 µl hybridization buffer (80% formamide, 40 mM PIPES pH 6.4, 1 mM EDTA, 400 mM NaCl), heated at 80°C for 10 min, and then incubated at 42°C for 12–15 h. Following hybridization, 200 µL of RNase T1 (0.5 U in 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA) was added and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Digestion was quenched by adding 10 µL of 10% SDS. The samples were extracted with phenol:chloroform, ethanol precipitated, and analyzed by denaturing PAGE.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health (National Institute of General Medical Sciences) grant GM52470 (to S.S. and B.S.). We thank Dr. T. Sugiyama for the mmi1Δ mei4-P527 strain.

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.063966.117.

REFERENCES

- Ard R, Allshire RC. 2016. Transcription-coupled changes to chromatin underpin gene silencing by transcriptional interference. Nucleic Acids Res 44: 10619–10630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ard R, Tong P, Allshire RC. 2014. Long non-coding RNA-mediate transcriptional interference of a permease gene confers drug tolerance in fission yeast. Nat Commun 5: 5576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter-O'Connell I, Peel MT, Wykoff DD, O'Shea EK. 2012. Genome-wide characterization of the phosphate starvation response in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. BMC Genomics 13: 697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee D, Sanchez AM, Goldgur Y, Shuman S, Schwer B. 2016. Transcription of lncRNA prt, clustered prt RNA sites for Mmi1 binding, and RNA polymerase II CTD phospho-sites govern the repression of pho1 gene expression under phosphate-replete conditions in fission yeast. RNA 22: 1011–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross T, Käufer NF. 1998. Cytoplasmic ribosomal protein genes of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe display a unique promoter type: a suggestion for nomenclature of cytoplasmic ribosomal proteins in databases. Nucleic Acids Res 26: 3319–3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harigaya Y, Tanaka H, Yamanaka S, Tanaka K, Watanabe Y, Tsutsumi C, Chikashige Y, Hiraoka Y, Yamashita A, Yamamoto M. 2006. Selective elimination of messenger RNA prevents an incidence of untimely meiosis. Nature 442: 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry TC, Power JE, Kerwin CL, Mohammed A, Weissman JS, Cameron DM, Wykoff DD. 2011. Systematic screen of Schizosaccharomyces pombe deletion collection uncovers parallel evolution of the phosphate signal pathways in yeasts. Eukaryot Cell 10: 198–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrick D, Parker R, Jacobson A. 1990. Identification and comparison of stable and unstable RNAs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 10: 2269–2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg S, Schjerling P. 1996. Cha4p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae activates transcription via serine/threonine response elements. Genetics 144: 467–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilchert C, Wittmann S, Passoni M, Shah S, Granneman S, Vasiljeva L. 2015. Regulation of mRNA levels by decay-promoting introns that recruit the exosome specificity factor Mmi1. Cell Rep 13: 2504–2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larochelle M, Hunyadkürti J, Bachand F. 2017. Polyadenylation site selection: linking transcription and RNA processing via a conserved carboxy-terminal domain (CTD)-interacting protein. Curr Genet 63: 195–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee NN, Chalamcharia VR, Reyes-Turce F, Mehta S, Zofall M, Balachandran V, Dhakshnamoorthy J, Taneja N, Yamanaka S, Zhou M, Grewal S. 2013. Mtr4-like protein coordinates nuclear RNA processing for heterochromatin assembly and for telomere maintenance. Cell 155: 1061–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemay JF, Marguerat S, Larochelle M, Liu X, van Nues R, Hunyadkürti J, Hoque M, Tian B, Granneman S, Bähler J, et al. 2016. The Nrd1-like protein Seb1 coordinates cotranscriptional 3′ end processing and polyadenylation site selection. Genes Dev 30: 1558–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loya TJ, Reines D. 2016. Recent advances in understanding transcription termination by RNA polymerase II. F1000Res 5: 1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens JA, Laprade L, Winston F. 2004. Intergenic transcription is required to repress the Saccharomyces cerevisiae SER3 gene. Nature 429: 571–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens JA, Wu PY, Winston F. 2005. Regulation of an intergenic transcript controls adjacent gene transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev 19: 2695–2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata J. 2013. Genome-wide mapping of polyadenylation sites in fission yeast reveals widespread alternative polyadenylation. RNA Biol 10: 1407–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira-Ramos S, Rojas DA, Montes M, Urbina F, Miralles VJ, Maldonado E. 2015. Casein kinase 2 inhibits HomolD-directed transcription by Rrn7 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. FEBS J 282: 491–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabavi S, Nazar RN. 2008. U3 snoRNA promoter reflects the RNA's function in ribosome biogenesis. Curr Genet 54: 175–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas DA, Moreira-Ramos S, Zock-Emmenthal S, Urbina F, Contreras-Levicoy J, Käufer NF, Maldonado E. 2011. Rrn7 protein, an RNA polymerase I transcription factor, is required for RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription directed by core promoters with a HomolD box sequence. J Biol Chem 286: 26480–26486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwer B, Shuman S. 2011. Deciphering the RNA polymerase II CTD code in fission yeast. Mol Cell 43: 311–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwer B, Sanchez AM, Shuman S. 2012. Punctuation and syntax of the RNA polymerase II CTD code in fission yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109: 18024–18029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwer B, Bitton DA, Sanchez AM, Bähler J, Shuman S. 2014. Individual letters of the RNA polymerase II CTD code govern distinct gene expression programs in fission yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111: 4185–4190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwer B, Sanchez A, Shuman S. 2015. RNA polymerase II CTD phospho-sites Ser5 and Ser7 govern phosphate homeostasis in fission yeast. RNA 21: 1770–1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwer B, Sanchez AM, Garg A, Chatterjee D, Shuman S. 2017. Defining the DNA binding site recognized by the fission yeast Zn2Cys6 transcription factor Pho7 and its role in phosphate homeostasis. mBio 8: e01218–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S, Wittmann S, Kilchert C, Vasiljeva L. 2014. lncRNA recruits RNAi and the exosome to dynamically regulate pho1 expression in response to phosphate levels in fission yeast. Genes Dev 28: 231–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama T, Sugioka-Sugiyama R. 2011. Red1 promotes the elimination of meiosis-specific mRNAs in vegetatively growing fission yeast. EMBO J. 30: 1027–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Zhu Y, Bao H, Jiang Y, Xu C, Wu J, Shi Y. 2016. A novel RNA-binding mode of the YTH domain reveals the mechanism for recognition of determinant of selective removal by Mmi1. Nucleic Acids Res 44: 969–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt I, Straub N, Käufer NF, Gross T. 1993. The CAGTCACA box in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe functions like a TATA element and binds a novel factor. EMBO J 12: 1201–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt I, Kwart M, Groβ T, Käufer NF. 1995. The tandem repeat AGGGTAGGGT is, in the fission yeast, a proximal activation sequence and activates basal transcription mediated by the sequence TGTGACTG. Nucleic Acids Res 23: 4296–4302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita A, Shichino Y, Tanaka H, Hiriart E, Touat-Todeschini L, Vavasseur A, Ding DQ, Hiraoka Y, Verdel A, Yamamoto M. 2012. Hexanucleotide motifs mediate recruitment of the RNA elimination machinery to silent meiotic genes. Open Biol 2: 120014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.