Abstract

Accurate detection of genomic alterations, especially druggable hotspot mutations in tumors, has become an essential part of precision medicine. With targeted sequencing, we can obtain deeper coverage of reads and handle data more easily with a relatively lower cost and less time than whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing. Recently, we designed a customized gene panel for targeted sequencing of major solid cancers. In this study, we aimed to validate its performance. The cancer panel targets 95 cancer-related genes. In terms of the limit of detection, more than 86% of target mutations with a mutant allele frequency (MAF) <1% can be identified, and any mutation with >3% MAF can be detected. When we applied this system for the analysis of Acrometrix Oncology Hotspot Control DNA, which contains more than 500 COSMIC mutations across 53 genes, 99% of the expected mutations were robustly detected. We also confirmed the high reproducibility of the detection of mutations in multiple independent analyses. When we explored copy number alterations (CNAs), the expected CNAs were successfully detected, and this result was confirmed by target-specific genomic quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Taken together, these results support the reliability and accuracy of our cancer panel in detecting mutations. This panel could be useful for key mutation profiling research in solid tumors and clinical translation.

Keywords: cancer panel, high-throughput DNA sequencing, next-generation sequencing, precision medicine

Introduction

Accurate detection of genomic alterations, especially druggable hot spot mutations in tumors, has become an essential part of precision medicine and medical research. Due to the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology, the ability to identify mutations has increased enormously, which has facilitated the realization of precision medicine [1]. However, even with NGS technology, the amount of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data is too large to handle by most researchers or clinicians. Whole-exome sequencing (WES), which targets the protein-coding sequences of whole genomes, is more efficient and cost-effective than WGS. Therefore, WES data are the most commonly generated NGS data in the research field [2]. However, the amount of WES data is too vast for clinicians to analyze and use in clinical practice, requiring an expert. In addition to data size issues, analyzing WES data needs experienced bioinformaticians, which is another big hurdle for clinical translation and application to basic research. The limited amount of available druggable targets is another practical limitation of WES for clinical translation.

Compared with WES and WGS, targeted sequencing uses target enrichment methods to capture or amplify regions of interest. With targeted sequencing, we can get deeper coverage of reads and handle data more easily with relatively lower cost and less time. For these reasons, targeted sequencing is noted to identify hotspot mutations and copy number alterations (CNAs) in cancer-related genes in the clinical field and research. It enables one to diagnose quickly and accurately and suggest appropriate therapeutic approaches that can elicit a favorable treatment outcome [3–5]. The flexibility of designing the number of genes and areas of interest is another advantage of a customized panel. In the new era of precision medicine, a number of institutes have developed customized target sequencing tools for discovering effective therapeutic agents [6–8].

In spite of these advantages, the performance of customized panels must be validated, such as evenness of on-target rates and their sensitivity/specificity in detecting mutations [9]. We recently developed a customized NGS panel, named OncoChase-AS, for targeted sequencing of major solid cancers. In this study, we aimed to validate its performance.

Methods

Samples

To validate the performance of OncoChase-AS, we first tested the limit of mutation detection by using the Quantitative Multiplex Reference Standard, which contains 11 mutations across six cancer-related genes (Horizon Discovery, Cambridge, UK). Mutation detection was examined using the Acrometrix Oncology Hotspot Control (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), a mixture of more than 500 Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) mutations across 53 genes. Four cell lines (HCT116, H1975, SW620, and HT29) were obtained from the Korean Cell Line Bank and used to assess the correlation with repeatability and reproducibility. To test the identification of CNAs, we used two primary tumors that are known to have CNAs, with the approval of the institutional review board of Catholic University of Korea. Genomic DNA was extracted from these samples using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

NGS and data analysis

We performed NGS analysis for the DNA samples with the OncoChase-AS cancer panel using an Ion S5 sequencer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Raw sequence data were analyzed with the Torrent Suite (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The aligner for mapping reads to the reference genome is included in the Torrent Suite [10]. To call variants from the mapped sequence data, we used a plug-in in the Torrent Suite, Torrent Variant Caller (v5.2.2.41). In order to annotate the called variants with the queried knowledge database, we used ANNOVAR [11]. In order to verify variants that were not detected by the Torrent Variant Caller plug-in, we confirmed no-called variants using the Integrative Genomic Viewer (IGV) program [12] with binary alignment mapping (BAM) format files as raw sequencing data before calling variants [13].

Limit of mutation detection

To verify the limit of detection, we used the Quantitative Multiplex Reference Standard DNA (Horizon Discovery) sample, which contains 11 variants with variant allele frequencies (VAFs) ranging from 1% to 24.5%. We diluted the reference DNA from 100% to 10% and sequenced it with OncoChase-AS. The limit of detection and correlation between the expected and observed VAFs were calculated as described [14]. Correlation coefficient and linear regression analysis was performed using R.

Concordance of variant detection

To check the concordance of the detected variants, Acrometrix Oncology Hotspot Control DNA (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used. NGS reactions were performed with the OncoChase-AS panel in triplicated runs. We annotated the variants using the ANNOVAR program [11]. The criteria for variant calling were as follows: exonic variants detected in more than 5% in the 1000 Genomes Project and the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) Project for East Asian and variants with >3% mutant allele frequency (MAF) [15, 16].

Reproducibility of mutation detection

To check the repeatability and reproducibility of the detection of mutations, especially mutations with a low VAF, we prepared mixtures of the DNAs extracted from four cell lines (H1975, HCT116, HT29, and SW620). NGS experiments were performed in duplicate by different researchers independently.

Detection of CNA

DNA copy number profiling of the targeted sequencing data was performed using NEXUS Copy Number, v9.0 (BioDiscovery, El Segundo, CA). CNA regions were defined by a rank segmentation algorithm. In the rank segmentation algorithm, we set a threshold for segmentation of p = 1.0E–6. The thresholds for copy number gain and loss were 0.3 and −0.4 on a log2 scale, respectively. The thresholds for amplification and homozygous deletion were 1.0 and −1.0 on a log2 scale, respectively.

Results and Discussion

Design of the custom cancer panel

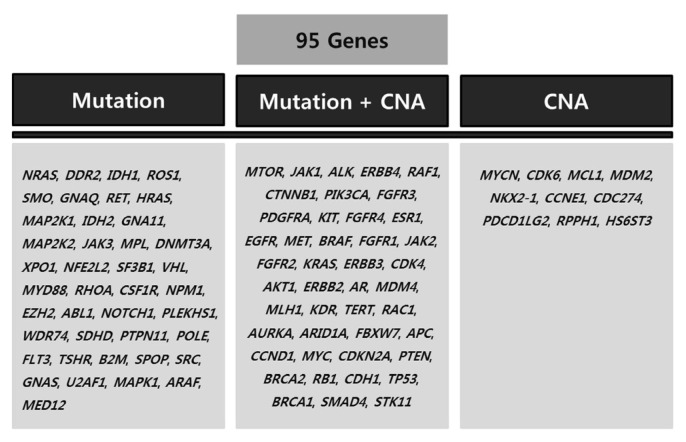

The custom NGS panel, named OncoChase-AS, was designed to detect 95 cancer-related genes with clinically important variants (Fig. 1). The 95 genes were selected based on the published literature and cancer databases, such as COSMIC [17] and GENIE [18]. Of the 95 target genes, 41 genes were selected for mutation screening, 10 genes were selected for CNA screening, and the other 44 genes were selected for screening of both mutations and CNAs (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The 95 target genes in the OncoChase-AS panel. CNA, copy number alteration.

Limit of mutation detection

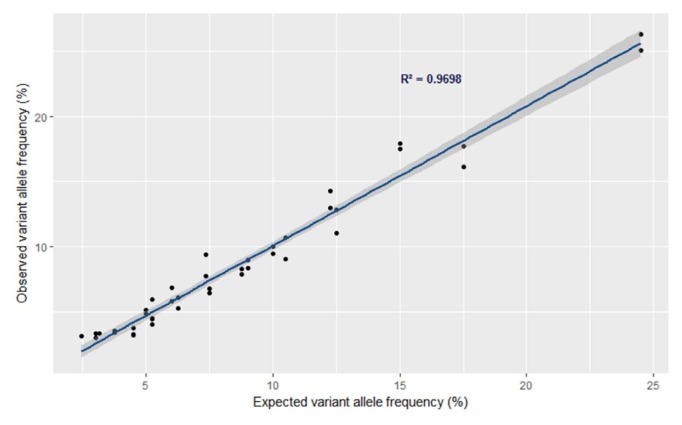

To determine the limit of mutation detection with OncoChase-AS, we used the Quantitative Multiplex Reference Standard DNA (Horizon Discovery), which contains 11 mutations with a 1% to 24.5% VAF across six cancer-related genes (BRAF, KIT, EGFR, KRAS, NRAS, and PIK3CA) (Table 1). When we performed NGS analysis with Onco-Chase-AS in duplicate, all of the expected mutations were consistently identified in both NGS analyses (Table 1). To assess the limit of mutation detection, we serially diluted the DNA sample from 50% to 10% and performed NGS analysis with each diluted DNA in duplicate. As a result, mutations with a very low MAF (<1% MAF) were successfully identified in most of the mutations (19/22, 86.4%). Mutations with a low MAF (1% to 3% MAF) were also successfully identified in most of the mutations (23/26, 88.5%). All mutations with >3% MAF were detected without exception (40/40, 100%) (Table 1). These results suggest that more than 86% of the mutations with <1% VAF can be identified by NGS analysis with OncoChase-AS. These results also suggest that any mutations with >3% frequency can be detected with this platform. When we calculated the correlation between the expected and observed VAFs by linear regression analysis, the R2 value was 0.97 (Fig. 2). This result further supports the reliability of this system for variant identification.

Table 1.

Limit of mutation detection

| Gene | Variant | Chromosome | Expected variant allelic frequency (%) | Detected variant allelic frequency (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Run 1 | Run 2 | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Dilution | Dilution | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Nonea | 50% | 30% | 10% | Nonea | 50% | 30% | 10% | |||||

| 1 | BRAF | V600E | 7q34 | 10.5 | 10.7 | 4.5 | 3.3 | 1.1 | 9.0 | 6.0 | 2.6 | 1.1 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| 2 | KIT | D816V | 4q11–q12 | 10.0 | 9.5 | 4.9 | 3.0 | - | 10.0 | 5.1 | - | - |

|

| ||||||||||||

| 3 | EGFR | ΔE746-A750 | 7p12 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| 4 | EGFR | L858R | 7p12 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.3 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| 5 | EGFR | T790M | 7p12 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | - | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| 6 | EGFR | G719S | 7p12 | 24.5 | 25.1 | 14.3 | 9.4 | 3.1 | 26.3 | 12.9 | 7.7 | 2.9 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| 7 | KRAS | G13D | 12p12.1 | 15.0 | 17.5 | 6.5 | 3.7 | - | 17.9 | 6.8 | 3.3 | - |

|

| ||||||||||||

| 8 | KRAS | G12D | 12p12.1 | 6.0 | 5.8 | 2.7 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 6.9 | 3.3 | 1.8 | 0.9 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| 9 | NRAS | Q61K | 1p13.2 | 12.5 | 12.8 | 5.3 | 3.6 | - | 11.0 | 6.1 | 3.4 | - |

|

| ||||||||||||

| 10 | PIK3CA | H1047R | 3q26.32 | 17.5 | 17.7 | 7.9 | 4.4 | 0.7 | 16.1 | 8.3 | 4.1 | 1.2 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| 11 | PIK3CA | E545K | 3q26.32 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 3.3 | 2.4 | 0.7 | 8.3 | 3.2 | 1.7 | 0.7 |

Next-generation sequencing was performed with Quantitative Multiplex Reference Standard DNA using the OncoChase-AS panel.

No dilution.

Fig. 2.

Correlation between expected variant allele frequency and observed variant allele frequency. The correlation was calculated using variants that were detected with >3% allele frequency.

Performance in detecting mutations

To determine how completely OncoChase-AS NGS detected the expected mutations, we used Acrometrix Oncology Hotspot Control DNA (Thermo Fisher Scientific), which is a mixture of 55 tumors that contain more than 500 COSMIC mutations across 53 genes. Among the mutations in the Acrometrix Oncology Hotspot Control DNA, OncoChase-AS targeted 358 mutations. Therefore, in principle, 358 mutations are expected to detected, if OncoChase-AS NGS works perfectly. In the first analysis, 353 out of the 358 expected mutations were detected (98.6% concordance). In the second analysis, all 358 mutations were detected (100% concordance). In the third analysis, the concordance rate was 98.6% (353/358) (Table 2). These results indicate that OncoChase-AS is fairly sensitive and reliable in identifying mutations.

Table 2.

Concordance of mutation detection

| Run | No. of expected mutations | No. of detected mutations | Concordance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 358 | 353 | 98.6 |

| 2 | 358 | 358 | 100.0 |

| 3 | 358 | 353 | 98.6 |

Reproducibility of mutation detection

Cancer gene panels can be used for clinical tests, such as the identification of druggable mutations from tumor tissue or liquid biopsy, in addition to research. Therefore, the reproducibility of mutation detection is an important issue. To test the reproducibility of mutation detection, we performed OncoChase-AS NGS with four cell lines (H1975, HCT116, HT29, and SW620) harboring eight known mutations (Table 3). In this analysis, cell line mixture samples were sequenced in triplicate by two different researchers. All of the expected mutations in mixtures and the MAFs were measured in every run. With these results, we verified the repeatability and reproducibility of the Onco-Chase-AS panel. The average repeatability and reproducibility were 98% (ranging from 93% to 100%) and 98% (ranging from 95% to 100%), respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Reproducibility and repeatability of mutation detection

| Cell line | Gene | Mutation | Repeatability (%) | Reproducibility (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1975 | EGFR | T790M | 100 | 100 |

| L858R | 95 | 95 | ||

|

| ||||

| HCT116 | PIK3CA | H1047R | 93 | 95 |

| KRAS | G13D | 99 | 97 | |

|

| ||||

| HT29* | SMAD4 | Q311* | 100 | 100 |

| BRAF | V600E | 99 | 97 | |

|

| ||||

| SW620 | KRAS | G12V | 100 | 100 |

| APC | Q1338* | 100 | 99 | |

Detection of CNAs

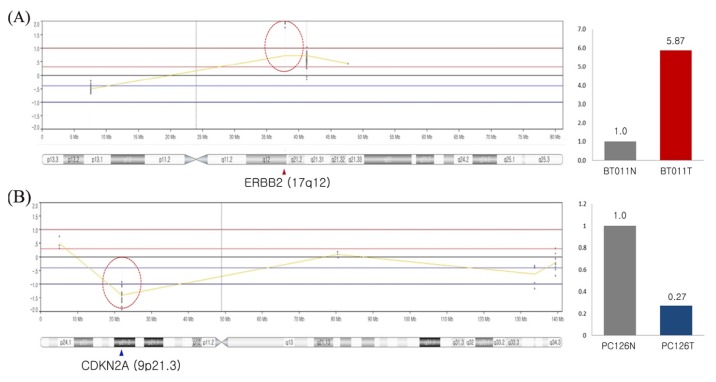

Chromosomal alteration is one of the most commonly occurring events during tumorigenesis. OncoChase-AS was designed to detect CNAs for 54 genes, including most of the clinically important CNAs, such as ERBB2 amplification and CDKN2A/B deletion. To test whether OncoChase-AS detected CNAs properly, we analyzed two primary tumors (brain cancer and sarcoma) with known CNAs: ERBB2 amplification in a brain cancer and CDKN2A deletion in a sarcoma. As a result, the expected CNAs were detected precisely by OncoChase-AS NGS analysis (Fig. 3). When we validated the target CNAs by genomic quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), the results were consistent with the NGS analysis results. Although we did not test all 54 target genes, the current results indicate that OncoChase-AS can robustly detect clinically important CNAs.

Fig. 3.

Copy number alterations detected by sequencing using the Onco-Chase-AS01 panel. (A) ERBB2 amplification in brain cancer patient and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) result of ERBB2 amplification. (B) CDKN2A copy number deletion in sarcoma cancer patient and quantitative PCR result of CDKN2A copy number deletion.

In conclusion, we have developed a cancer panel containing 95 cancer-related genes. In terms of the limit of detection, OncoChase-AS can detect more than 86% of target mutations with <1% MAF. In the case of those with >3% MAF, any mutation can be detected by NGS analysis with OncoChase-AS. When we applied this system for the analysis of Acrometrix Oncology Hotspot Control DNA, which contains more than 500 COSMIC mutations across 53 genes, 99% of the expected mutations were robustly detected. We also confirmed the very high reproducibility of the mutation detection in multiple independent analyses. When we examined CNAs, two expected CNAs related to tumorigenesis were successfully detected, and this result was confirmed by target-specific genomic qPCR. All of these results support the reliability and accuracy of our Onco-Chase-AS platform in detecting mutations. Therefore, this panel could be helpful for key mutation profiling research in solid tumors and clinical translational research, because this panel covers all 14 essential genes that have been suggested to be included in cancer panels for support from the national health insurance system in Korea. There are limitations of our panel. Due to the technical limitations of PCR amplification-based NGS, OncoChase-AS cannot detect repeat sequences with enough reliability and reproducibility, such as microsatellite instabilities and the promoter region of the TERT gene. For this purpose, a hybridization-based targeted sequencing panel would be more suitable.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Science of Korea (NRF-2015M3C7A1064778 and NRF-2017M3C9A6047615).

Computer analysis work was supported by KREONET (Korea Research Environment Open NETwork) which is managed and operated by KISTI (Korea Institute of Science and Technology Information).

Footnotes

Authors’ contribution

Conceptualization: YJC, SHJ

Data curation: SHC, SHJ

Data analysis: SHC, SHJ, YJC

Funding acquisition: YJC

Writing – original draft: SHC, SHJ

Writing – review & editing: YJC

References

- 1.Davey JW, Hohenlohe PA, Etter PD, Boone JQ, Catchen JM, Blaxter ML. Genome-wide genetic marker discovery and genotyping using next-generation sequencing. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:499–510. doi: 10.1038/nrg3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fontanges Q, De Mendonca R, Salmon I, Le Mercier M, D’Haene N. Clinical application of targeted next generation sequencing for colorectal cancers. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:E2117. doi: 10.3390/ijms17122117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen A, Conley B, Hamilton S, Williams M, O’Dwyer P, Arteaga C, et al. NCI-Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice (NCI-MATCH) trial: a novel public-private partnership. Eur J Cancer. 2016;69(Suppl 1):S137. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meldrum C, Doyle MA, Tothill RW. Next-generation sequencing for cancer diagnostics: a practical perspective. Clin Biochem Rev. 2011;32:177–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goossens N, Nakagawa S, Sun X, Hoshida Y. Cancer biomarker discovery and validation. Transl Cancer Res. 2015;4:256–269. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-676X.2015.06.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyman DM, Solit DB, Arcila ME, Cheng DT, Sabbatini P, Baselga J, et al. Precision medicine at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center: clinical next-generation sequencing enabling next-generation targeted therapy trials. Drug Discov Today. 2015;20:1422–1428. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia-Murillas I, Schiavon G, Weigelt B, Ng C, Hrebien S, Cutts RJ, et al. Mutation tracking in circulating tumor DNA predicts relapse in early breast cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:302ra133. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meric-Bernstam F, Brusco L, Shaw K, Horombe C, Kopetz S, Davies MA, et al. Feasibility of large-scale genomic testing to facilitate enrollment onto genomically matched clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2753–2762. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah PD, Nathanson KL. Application of panel-based tests for inherited risk of cancer. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2017;18:201–227. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-091416-035305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodwin S, McPherson JD, McCombie WR. Coming of age: ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17:333–351. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rathi V, Wright G, Constantin D, Chang S, Pham H, Jones K, et al. Clinical validation of the 50 gene AmpliSeq Cancer Panel V2 for use on a next generation sequencing platform using formalin fixed, paraffin embedded and fine needle aspiration tumour specimens. Pathology. 2017;49:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pathol.2016.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vendrell JA, Grand D, Rouquette I, Costes V, Icher S, Selves J, et al. High-throughput detection of clinically targetable alterations using next-generation sequencing. Oncotarget. 2017;8:40345–40358. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.1000 Genomes Project Consortium. Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, DePristo MA, Durbin RM, et al. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, Fennell T, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forbes SA, Beare D, Bindal N, Bamford S, Ward S, Cole CG, et al. COSMIC: high-resolution cancer genetics using the catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2016;91:10.11.1–10.11.37. doi: 10.1002/cphg.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.AACR Project GENIE Consortium AACR Project GENIE: powering precision medicine through an international consortium. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:818–831. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]