Marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug during pregnancy, and its use is increasing. From 2002 to 2014, the prevalence of self-reported, past-month marijuana use among US adult pregnant women increased from 2.4% to 3.9%.1 In aggregated 2002–2012 data, 14.6% of US pregnant adolescents reported past-month use.2 However, studies are limited to self-reported surveys and likely underestimate use due to social desirability bias and underreporting, leaving the scope of the problem unclear. We investigated trends of prenatal marijuana use from 2009–2016 using data from a large California health care system with universal screening via self-report and urine toxicology.

Methods

The Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) institutional review board approved and waived consent for this study. KPNC is an integrated health care system serving approximately 4 million patients representative of the geographic area. The sample comprised KPNC pregnant females 12 years or older who completed a self-administered questionnaire on marijuana use since pregnancy and a cannabis toxicology test (58% occurred at the same visit as the questionnaire, 87% occurred within 2 weeks of completing the questionnaire) during standard prenatal care (at approximately 8 weeks’ gestation) from 2009 through 2016.

We estimated the adjusted prevalence of prenatal marijuana use via self-report or toxicology annually using Poisson regression with a log link function, controlling for age, race/ethnicity, and median neighborhood household income using SAS (SAS Institute), version 9.3. Adjusted prevalence estimates used the average covariate distributions across the study period. We tested for linear trends and differences in trends by age. Two-sided P values less than .05were considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 31 8085 pregnant females, 38 628 (12.1%) were excluded (1123 who missed the self-reported screening questionnaire [0.4%], 37 303 who missed a toxicology test [11.7%], and 202 who missed both [0.06%]). The race/ethnicity of the 279 457 females (87.9%) included in the study was 36.0% white, 27.9% Hispanic, 16.6% Asian, 5.9% black, and 13.6% other. The age ranges of the sample included females aged 12 to 17 years (1.4%), 18 to 24 years (15.8%), 25 to 34 years (61.6%), and more than 34 years (21.2%). The median neighborhood household income was $70 677 (interquartile range, $51 645–$92 917).

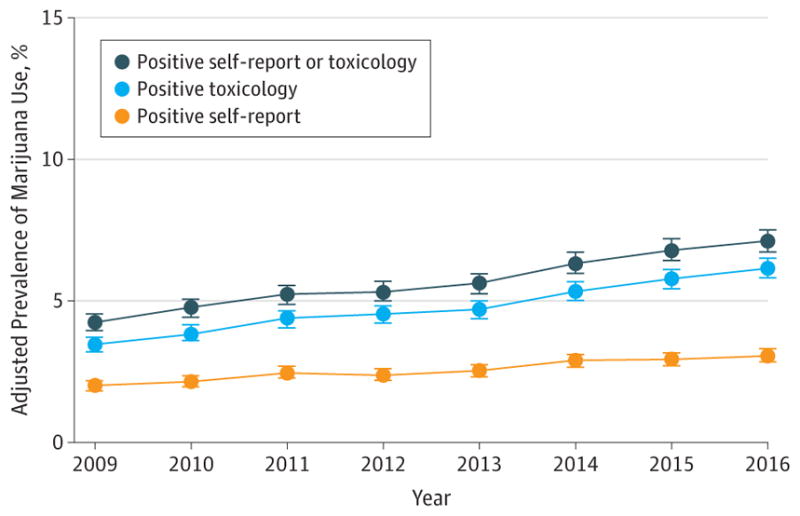

From 2009 through 2016, the adjusted prevalence of prenatal marijuana use based on self-report or toxicology increased from 4.2% (95% CI, 4.0%–4.5%) to 7.1% (95% CI, 6.7%–7.5%) and was higher based on toxicology than self-report each year (Figure 1). Linear trend tests found use increased at an annual rate of 1.075 for self-report or toxicology (95% CI, 1.064–1.085; P < .001), 1.083 for toxicology (95% CI, 1.072–1.094; P < .001), and 1.062 for self-report (95% CI, 1.048–1.075; P < .001).

Figure 1. Adjusted Prevalence of Marijuana Use Among 279 457 Pregnant Females in KPNC by Screening Type, 2009–2016.

KPNC indicates Kaiser Permanente Northern California. Error bars indicate 95% CIs of the adjusted prevalences. Poisson regression models controlled for age group, race/ethnicity, and median neighborhood household income (extracted from the electronic health record). The self-reported use questionnaire and toxicology screening were part of standard prenatal care (at approximately 8 weeks’ gestation; 84%of females completed both screenings during their first trimester). For toxicology tests, 58%were completed at the same visit as the self-reported use questionnaire, 87%were completed within 14 days of completing the questionnaire, and 100% were completed within 8 weeks of completing the questionnaire. All toxicology tests were confirmed with a confirmatory laboratory test. Among pregnant females with a positive test result for prenatal marijuana use, 15.9% were positive on self-report only, 54.9%were positive on toxicology only, and 29.2%were positive on both self-report and toxicology. The sample of females included in the study was generally representative of the population of all pregnant females. There were only small differences in the demographic characteristics of females who were included vs excluded (due to missing data on prenatal marijuana use), indicating minimal to no selection bias. The median sample size across years was 34 322 (range, 32 813–38 919).

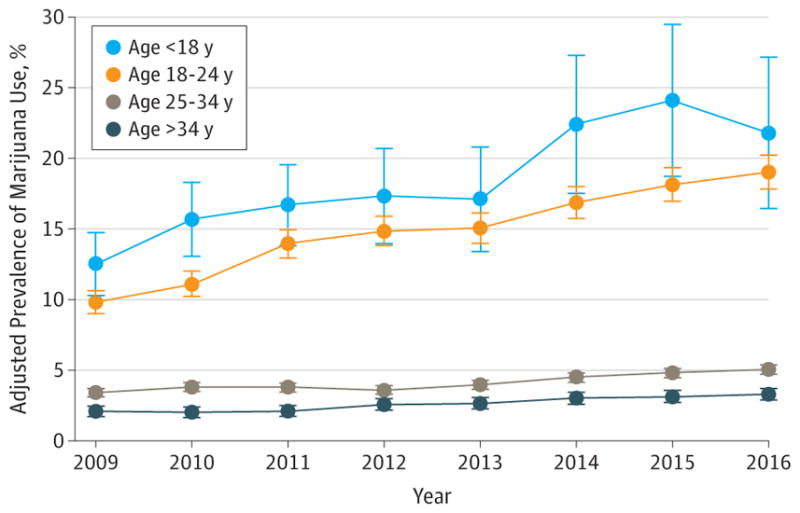

The adjusted prevalence based on self-report or toxicology increased significantly from 2009 to 2016 for each age group (Figure 2). Use among females younger than 18 years to age 24 years increased the most, from 12.5% (95% CI, 10.3%–14.7%) to 21.8% (95% CI, 16.5%–27.2%) for those younger than 18 years and from 9.8% (95% CI, 9.0%- 10.6%) to 19.0% (95% CI, 17.8%–20.2%) for those aged 18 to 24 years. Use among women aged 25 to 34 years increased from 3.4% (95% CI, 3.1%–3.7%) to 5.1% (95% CI, 4.7%–5.4%) and use among women older than 34 years increased from 2.1% (95% CI, 1.7%–2.5%) to 3.3% (95% CI, 2.9%–3.7%). Linear trend tests found prenatal use increased at an annual relative rate of 1.088 for females younger than 18 years (95% CI, 1.037–1.142; P = .01), 1.092 for those aged 18 to 24 years (95% CI, 1.076–1.108; P < .001), 1.080 for those aged 25 to 34 (95% CI, 1.047–1.113; P < .001), and 1.057 for those older than 34 years (95% CI, 1.042–1.072; P < .001). Trends varied by age (P = .02).

Figure 2. Adjusted Prevalence of Marijuana Use Among 279 457 Pregnant Females in KPNC by Age, 2009–2016.

KPNC indicates Kaiser Permanente Northern California. Results were based on positive self-report or positive toxicology screening. Error bars indicate 95%CIs of the adjusted prevalences. Age groups included younger than 18 years (n = 3813; 1.4%); 18 to 24 years (n = 44 112; 15.8%); 25 to 34 years (n = 172 278; 61.6%); and older than 34 years (n = 59 254; 21.2%). Poisson regression models by age group controlled for race/ethnicity and median neighborhood household income (extracted from the electronic health record). The self-reported use questionnaire and toxicology screening were part of standard prenatal care (at approximately 8 weeks’ gestation; 84%of females completed both screenings during their first trimester). For toxicology tests, 58%were completed at the same visit as the self-reported use questionnaire, 87%were completed within 14 days of completing the questionnaire, and 100% were completed within 8 weeks of completing the questionnaire. All toxicology tests were confirmed with a confirmatory laboratory test. Among pregnant females with a positive test result for prenatal marijuana use, 15.9%were positive on self-report only, 54.9% were positive on toxicology only, and 29.2%were positive on both self-report and toxicology. The sample of females included in the study was generally representative of the population of all pregnant females. There were only small differences in the demographic characteristics of females who were included vs excluded (due to missing data on prenatal marijuana use), indicating minimal to no selection bias. The median (range) sample size for each age group was 443 (236–779) for less than 18 years; 5485 (5221–5956) for 18 to 24 years; 21 258 (20 002–24 347) for 25 to 34 years; and 7236 (6532–8848) for more than 34 years.

Discussion

From 2009 to 2016, marijuana use among KPNC pregnant females increased from 4% to 7%. Of concern, 22% of pregnant females younger than 18 years and 19% of pregnant females aged 18 to 24 years screened positive for marijuana use in 2016. Age-specific, self-reported prevalences were similar to US data,1 but toxicology prevalences were higher, suggesting use has been underestimated in self-reported surveys. In California, medical marijuana was legalized in 1996, and prenatal use may further escalate in 2018 when recreational marijuana is available legally.

This study was limited to KPNC pregnant women screened for marijuana use at approximately 8 weeks’ gestation. Prenatal use before vs after women realized they were pregnant could not be distinguished. Marijuana is detectable approximately 30 days after last use and varies with heaviness of use and marijuana potency. It is possible, but unlikely, that some toxicology tests identified prepregnancy use.

Initial evidence suggests that prenatal marijuana may impair fetal growth and neurodevelopment,3 but 79% of 785 pregnant women surveyed between 2007 and 2012 reported perceiving little to no harm in prenatal use.4 Continued monitoring of trends, exposure timing, and offspring outcomes is important as marijuana potency rises5 in an increasingly permissive legal landscape.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by a grant from the Kaiser Permanente Community Benefits Program and a NIDA K01 award (DA043604) from the National Institutes of Health.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none were reported.

Author Contributions: Dr Young-Wolff had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Young-Wolff, Tucker, Armstrong, Conway, Weisner, Goler.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Young-Wolff, Tucker, Alexeeff, Armstrong, Weisner, Goler.

Drafting of the manuscript: Young-Wolff.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Young-Wolff, Tucker, Alexeeff, Armstrong.

Obtained funding: Young-Wolff, Armstrong.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Young-Wolff, Tucker, Conway.

Supervision: Young-Wolff, Weisner, Goler.

References

- 1.Brown QL, Sarvet AL, Shmulewitz D, Martins SS, Wall MM, Hasin DS. Trends in marijuana use among pregnant and nonpregnant reproductive-aged women, 2002–2014. JAMA. 2017;317(2):207–209. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Ugalde J, Todic J. Substance use and teen pregnancy in the United States. Addict Behav. 2015;45:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volkow ND, Compton WM, Wargo EM. The risks of marijuana use during pregnancy. JAMA. 2017;317(2):129–130. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.18612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ko JY, Farr SL, Tong VT, Creanga AA, Callaghan WM. Prevalence and patterns of marijuana use among pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(2):201e1–201.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ElSohly MA, Mehmedic Z, Foster S, Gon C, Chandra S, Church JC. Changes in cannabis potency over the last 2 decades (1995–2014) Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(7):613–619. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]