Abstract

As countries across sub-Saharan Africa work towards universal health coverage and HIV epidemic control, investments seek to bolster the quality and relevance of the health workforce. The African Health Profession Regulatory Collaborative (ARC) partnered with 17 countries across East, Central, and Southern Africa to ensure nurses and midwives were authorized and equipped to provide essential HIV services to pregnant women and children with HIV. Through ARC, nursing leadership teams representing each country identify a priority regulatory function and develop a proposal to strengthen that regulation over a 1-year period. Each year culminates with a summative congress meeting, involving all ARC countries, where teams present their projects and share lessons learned with their colleagues. During a recent ARC Summative Congress, a group survey was administered to 11 country teams that received ARC Year 4 grants to measure advancements in regulatory function using the five-stage Regulatory Function Framework, and a group questionnaire was administered to 16 country teams to measure improvements in national nursing capacity (February 2011–2016). In ARC Year 4, eight countries implemented continuing professional development projects, Botswana revised their scope of practice, Mozambique piloted a licensing examination to assess HIV-related competencies, and South Africa developed accreditation standards for HIV/tuberculosis specialty nurses. Countries reported improvements in national nursing leaders’ teamwork, collaborations with national organizations, regional networking with nursing leaders, and the ability to garner additional resources. ARC provides an effective, collaborative model to rapidly strengthen national regulatory frameworks, which other health professional cadres or regions may consider using to ensure a relevant health workforce, authorized and equipped to meet the emerging demand for health services.

Keywords: African Health Profession Regulatory Collaborative, global nursing regulation, Regulatory Function Framework

As countries work to realize the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 (United Nations, 2017), health professional regulation remains an important lever to ensure the health workforce is adequately authorized and equipped to meet the population demand for health services (Clarke, 2016; World Health Organization, 2016b). Regulation allows for sufficient production of competent health workers with relevant skills to deliver safe, high-quality care (World Health Organization, 2013). As countries examine their regulatory frameworks to ensure health professionals and health facilities are efficiently and effectively structured to sustainably deliver the necessary health services, increasing consideration is given to balancing public risk with regulatory requirements that produce a competent workforce with skills relevant to population health needs (Clarke et al., 2016; Professional Standards Authority, 2015). Globally, nursing and midwifery regulatory boards and councils seek to ensure professional competence, conduct, and mobility, as well as approaches to monitor their regulatory performance and effectiveness (Benton, Gonzalez-Jurado, & Beneit-Montesinos, 2013).

The African Health Profession Regulatory Collaborative (ARC) for Nurses and Midwives was established in 2011 to sustain the scale-up of HIV services by advancing nursing and midwifery regulatory frameworks, strengthening organizational capacity, and developing nursing and midwifery leadership (Gross, McCarthy, & Kelley, 2011). The ARC initiative was part of a global response to the critical health worker shortage and desire to meet ambitious health targets, including the Millennium Development Goals and the rapid scale-up of people living with HIV on antiretroviral therapy (ART) (World Health Organization, 2008, 2009). Although a correlation exists between an increased number of health care providers and positive health outcomes (World Health Organization, 2006), sub-Saharan Africa has a disproportionately high burden of disease and shortage of available health workers (Joint Learning Initiative, 2004; World Health Organization, 2016a). Global initiatives often invest in service delivery without comparable investments in health work-force capacity (World Health Assembly, 2006, 2013). The ARC initiative aimed to improve health care and health outcomes by investing in nursing and midwifery education, regulation, standards, and practice. ARC supported the formalization of HIV task sharing with nurses and midwives, as they comprise the largest cadre in Africa’s health delivery system (World Health Organization, 2006).

To achieve these aims, a multilateral partnership was formed of representatives from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); Emory University’s Lillian Carter Center for Global Health and Social Responsibility; the East, Central, and Southern Africa (ECSA) Health Community; Commonwealth Secretariat; and the Commonwealth Nurses and Midwives Federation (McCarthy & Riley, 2012). The ARC initiative brought together representatives from 17 countries in the ECSA region, including nursing and midwifery leaders in policy, regulation, education, and practice. Over the course of the ARC initiative, a national unity emerged, with nursing and midwifery leaders referring to their country teams as the “Quads.” This structure is similar to the International Council of Nurses’ triad structure, except for the additional inclusion of an academic representative. This innovative cross-country collaboration aimed to engage and build capacity in Africa’s health professional leadership for nursing and midwifery using local solutions and peer-based learning (Gross, Kelley, & McCarthy, 2015). The ARC initiative was funded through the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and received approximately $850,000 in Year 4.

The ARC conceptual framework was adapted from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s (IHI) model for breakthrough organizational change. The IHI Breakthrough Series© model is a 6- to 15-month learning system in which organizations learn about an area needing improvement from each other and from recognized experts. The IHI model is a series of alternating learning sessions and action periods (IHI, 2003). ARC used a three-pronged approach: (a) awarding 1-year grants, (b) providing technical assistance, and (c) convening regional learning sessions (Gross et al., 2011) to enhance nursing and midwifery capacity and to reduce bottlenecks in HIV services for women and children, specifically to authorize and advance nurse-initiated and -managed ART (NIMART). Numerous studies have found NIMART to be an efficient and cost-effective way to increase ART coverage in the region (Brennan et al., 2011; Kredo, Adeniyi, Bateganya, & Pienaar, 2014; Long et al., 2011; Penazzato, Davies, Apollo, Negussie, & Ford, 2014). The ARC initiative aimed to strengthen the capacity and collaboration of national organizations to perform key regulatory functions and to mobilize resources. It also aspired to foster a sustained regional network of nursing and midwifery leaders to facilitate the exchange of best practices. Each year, an evaluation was conducted to measure grantees’ progress over the course of the grant year (Dynes et al., 2016; McCarthy, Zuber, Kelley, Verani, & Riley, 2014). This study presents the results of the ARC Year 4 evaluation that assessed advancements in countries’ key regulatory functions and increases in national nursing and midwifery institutional capacity.

Methods

In ARC Year 4, 11 countries received $10,000 grants to address regulatory issues in continuing professional development (CPD), scope of practice (SOP), licensure, and accreditation to advance NIMART authorization and practice. During the February 2016 ARC Summative Congress, two evaluation tools were administered to nursing and midwifery leaders in practice, education, regulation, and policy from countries in the ECSA region. The first tool was a survey measuring regulatory advancement for the 11 countries that received ARC Year 4 grants.* The second was a questionnaire administered to 16 country teams** measuring improvements in perceptions of national-level teamwork, networking, fundraising, and interorganizational relationships. To facilitate discussion, improve accuracy, and minimize conflicting information, both instruments were self-administered by country teams as Quad group surveys. All participants gave voluntary individual informed consent. The protocol for this evaluation was reviewed and approved by the Emory Institutional Review Board, which determined it human subjects research exempt, and the CDC Associate Director for Science.

The first group survey tool was developed based on a Capability Maturity Model, which measures process improvement in stages over time (Paulk, Weber, Curtis, & Chrissis, 1994). The Capability Maturity Model used for this analysis was the Regulatory Function Framework (RFF), developed to assess the maturity of national nursing and midwifery regulatory systems (McCarthy, Kelley, Verani, St Louis, & Riley, 2014). In the RFF, stage 1 represents ad hoc function only, stage 2 confirms a documented process, stage 3 indicates routine practice, stage 4 demonstrates improved function, and stage 5 demonstrates optimized function to align with global and regional standards (Paulk et al., 1994). ARC used the RFF to measure maturity across seven regulatory functions—registration, licensure, SOP, CPD, preservice accreditation, professional discipline, and legislation—and administered it annually before ARC grantee implementation (Table 1) (McCarthy et al., 2014). The RFF was completed by ARC Year 4 grantees to measure advances in these seven functions. We compared the baseline RFF stages reported by the teams before they received their grants (February 2015) with RFF stages reported at the completion of project implementation (February 2016). To advance a stage on the RFF, all of the criteria for that stage must be met and all criteria for the previous stages must be fully met or exceeded. Because the RFF is designed to measure large structural advancements, some countries require more than 1 year to advance a single stage. Prior publications address RFF tool development (McCarthy et al., 2014) and refinement (Dynes et al., 2016).

TABLE 1. Regulatory Function Framework.

- Place a checkmark in the box next to every criteria that has been achieved.

- Circle the stage you feel most accurately reflects where your country is at in development. All criteria within a stage must be met in order to circle a stage.

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 | Stage 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing and Midwifery Legislation | □Identification of key issues with participation of stakeholders. □Consensus around whether a new nursing and midwifery Act or amendments to existing legislation are needed. |

□Legislation drafted with stakeholders including Ministry of Health, nursing and midwifery council and/or professional associations, academia, and legislature or parliament. | □Approval, commencement, and publication of legislation. | □Implementation through dissemination and training of nurses and midwives in their rights and duties. □Issuance by Councils and/or Ministry of Health of rules or regulations. |

□Monitoring and evaluation of compliance and impact. |

| Registration System and Use of Registration Data | □Registration is not legally required for nurses and midwives to practice. OR Registration is lifelong (i.e., renewal is not required). □The register is primarily a paper-based system. |

□Renewal of registration (or license) is required. □Both paper and electronic (e.g., Excel) system for registration is used. □Registration system can answer basic queries (e.g., number of midwifes in the country). |

□Registration system (including licensure and re-licensure) is primarily electronic (use of software). □Database includes all public sector nurses and is regularly updated. □Registration system can be queried to generate workforce reports. |

□Registration system is completely electronic and includes all public and private sector nurses. □Database displays various registration statuses of nurses and midwives. □Database can be programmed to automatically generate workforce reports. |

□Registration, licensure, and relicensure services are available online or are decentralized. □Registration database can exchange data with other health information systems. □Registration data used by decision makers for workforce policy and planning. |

| Licensure Process | □Licenses not required to practice. | □Licenses are issued with initial registration (no separate licensure examination). □Renewal of license is required at intervals specified by the regulatory authority. |

□An examination or assessment process is in place for initial registration and licensure. □The examination or assessment is paper based. □National competency standards are being developed. |

□Examination or assessment content meets national competency standards. □Various statuses of licenses issued (i.e., conditional, suspended). □Licensure verification process facilitates entry of foreign educated nurses/midwives into workforce. |

□Registration and initial licensure examination content is updated regularly. □Examination content aligns with global guidelines or regional competency standards. □The licensure status of a nurse or midwife is available to the public either via website, phone, or in person. |

| Scope of Practice (SOP) | □SOP not defined by legal statute or regulation. □SOP may be decided by the employer or based on health facility needs. |

□Council has the authority to formally define the SOP. □SOP are under development. □SOP reviewed or revised within 10 years. |

□Nationally standardized SOP for all nurse and midwife categories. □SOP is based on nursing/midwifery context, consultations, and job descriptions. □SOP reviewed or revised within last 5 years. |

□SOP includes essential nursing/midwifery competencies. □SOP is regularly and systematically reviewed and revised. □SOP allows for individuals to make decisions about task shifting or task sharing. |

□All SOP align with global guidelines and standards for nursing and midwifery. □SOP reviewed and revised according to global standards. □SOP is dynamic, flexible, and inclusive, not restrictive. |

| Continuing Professional Development (CPD) | □CPD does not exist. □CPD is voluntary. □CPD framework for nursing and midwifery may be in planning stages. |

□Council has a mandate in legislation to require CPD. □National CPD framework for nursing and midwifery is developed. □Implementation of CPD requirement is in pilot or early stages. |

□CPD program for nurses and midwives is finalized and nationally disseminated. □CPD is officially required for relicensure. □Strategy in place to promote and track compliance. |

□Electronic system in place to monitor CPD compliance. □Penalties for noncompliance with CPD exist. □Available CPD includes content on national HIV service delivery guidelines for nurses and midwives. |

□Multiple types of CPD are available including Web-based and mobile-based models. □CPD content aligns with regional standards or global guidelines. □Regular evaluations of CPD program carried out. |

| Accreditation of Preservice Education | □Council does not have legal authority to approve preservice nursing/midwifery schools or programs. □Public schools/programs may be “endorsed” by the council. |

□Council has legal authority to approve preservice schools/programs. □Council issues standards for accreditation of nursing schools/programs. □No time limit or expiration date on accreditation approval. |

□Initial assessment visits are carried out by the council or their designated authority. □Standards for accreditation are regularly reviewed and revised. □Requirement for accreditation renewal is enforced. |

□Assessment visits are regularly carried out by an independent body. □Council has an electronic system to track accreditation status. □Various levels of accreditation granted (i.e., probationary, conditional). |

□Group independent from council makes accreditation determination for both public and private schools/programs. □Accreditation standards align with global or regional guidelines. □Accreditation status available to the public. |

| Professional Misconduct and Disciplinary Powers | □Council does not have authority to manage complaints and impose sanctions. □Standards of professional conduct may not be defined. |

□Legislation authorizes council to define standards for professional conduct. □Council has authority to investigate or initiate inquiries into professional misconduct. □Basic types of complaints and sanctions exist. |

□Complaints investigation and misconduct hearings are separate processes. □A range of disciplinary measures (e.g., penalties, sanctions, conditions) exist. □Appeals processes are available and accessible. |

□The processes and documentation of complaints and sanctions are transparent. □Processes and timelines are in place to review and remove penalties and sanctions. □Processes are in place for members of the public to lodge a complaint. |

□Professional conduct standards align with regional standards or global guidelines. □The complaint management process is regularly evaluated for transparency and timeliness. □Information on complaints and sanctions is available to the public. |

The second group survey used a mixed-methods questionnaire to evaluate changes in national nursing capacity, specifically country teams’ perceptions of national-level teamwork, networking, fundraising, and interorganizational relationships. The tool asked country teams to indicate to what extent they engaged in these activities (using a five-level scale) before the initiation of ARC (February 2011) and at the end of the 4-year ARC initiative (February 2016) and to provide some descriptive detail about their experiences through open-ended questions. The participants were allotted 1 hour to discuss the questions and record the answers for their country team upon reaching group consensus. Two members of the ARC evaluation team conducted independent reviews to analyze the data, elicit trends, and summarize the results.

Results

During ARC Year 4, eight countries (Ethiopia, Kenya, Lesotho, Rwanda, Seychelles, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe) implemented CPD projects. Botswana revised its SOP, Mozambique piloted a prevention of mother-to-child transmission competency examination as part of the new graduate licensure process, and South Africa developed accreditation standards for HIV/tuberculosis (TB) specialty nurses. Table 2 describes the key achievements of each country’s project.

TABLE 2.

Grantee Achievements in ARC Year 4

| Country Team | Regulatory Function | Key Achievements |

|---|---|---|

| Botswana | Scope of Practice |

|

|

| ||

| Ethiopia | Continuing Professional Development |

|

|

| ||

| Kenya | Continuing Professional Development |

|

|

| ||

| Lesotho | Continuing Professional Development |

|

|

| ||

| Mozambique | Licensure |

|

|

| ||

| Rwanda | Continuing Professional Development |

|

|

| ||

| Seychelles | Continuing Professional Development |

|

| Scope of Practice |

|

|

|

| ||

| South Africa | Accreditation |

|

|

| ||

| Tanzania | Licensure |

|

| Continuing Professional Development |

|

|

| Scope of Practice |

|

|

|

| ||

| Zambia | Continuing Professional Development |

|

|

| ||

| Zimbabwe | Continuing Professional Development |

|

Note. ARC = African Health Profession Regulatory Collaborative; ART = antiretroviral therapy; CPD = continuing professional development; NIMART = nurse-initiated and -managed ART; PMTCT = prevention of mother-to-child transmission; TB = tuberculosis.

The stages and incremental criteria for each regulatory function (legislation, registration, licensure, SOP, CPD, preservice accreditation, and professional discipline) are described in detail in Table 1 (McCarthy et al., 2014). Regulatory advancements in the countries varied. Two countries advanced two stages on the RFF, three countries advanced one stage and six countries remained in the same stage (Table 3). Seychelles and Tanzania advanced from stage 1 to stage 2 for CPD, indicating their national councils now have a legal mandate to require CPD and that national CPD frameworks for nurses and midwives were established with CPD programs at the early stages of implementation. Lesotho advanced from stage 3 to stage 5, and Zimbabwe advanced from stage 4 to stage 5 for CPD, indicating their CPD programs have electronic systems, penalties for noncompliance, innovative modules (e.g., Web-based), content aligned with regional standards or global guidelines (including content on HIV guidelines for nurses and midwives), and regular evaluations. Botswana advanced from stage 3 to stage 5 for SOP, indicating that its nursing and midwifery scope is dynamic, flexible, inclusive, and reviewed/revised regularly to align with current global guidelines and standards.

TABLE 3.

Advancement by Regulatory Function Stage and Country for ARC Year 4 Grantees

| Country (Regulatory Function) | Beginning Year 4 (February 2015) | End Year 4 (February 2016) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rwanda (CPD) | 2 | 2 | — |

| Zimbabwe (CPD) | 4 | 5 | ↑ |

| Zambia (CPD) | 2 | 2 | — |

| Tanzania (CPD) | 1 | 2 | ↑ |

| South Africa (ACC) | 3 | 3 | — |

| Seychelles (CPD) | 1 | 2 | ↑ |

| Mozambique (LIC) | 1 | 1 | — |

| Lesotho (CPD) | 3 | 5 | ↑ |

| Kenya (CPD) | 3 | 3 | — |

| Ethiopia (CPD) | 2 | 2 | — |

| Botswana (SOP) | 3 | 5 | ↑ |

Note. ↑ = increased 1 stage or more; — = no stage advancement; ACC = Accreditation; ARC = African Health Profession Regulatory Collaborative; CPD = Continuing Professional Development; LIC = Licensure; SOP = Scope of Practice.

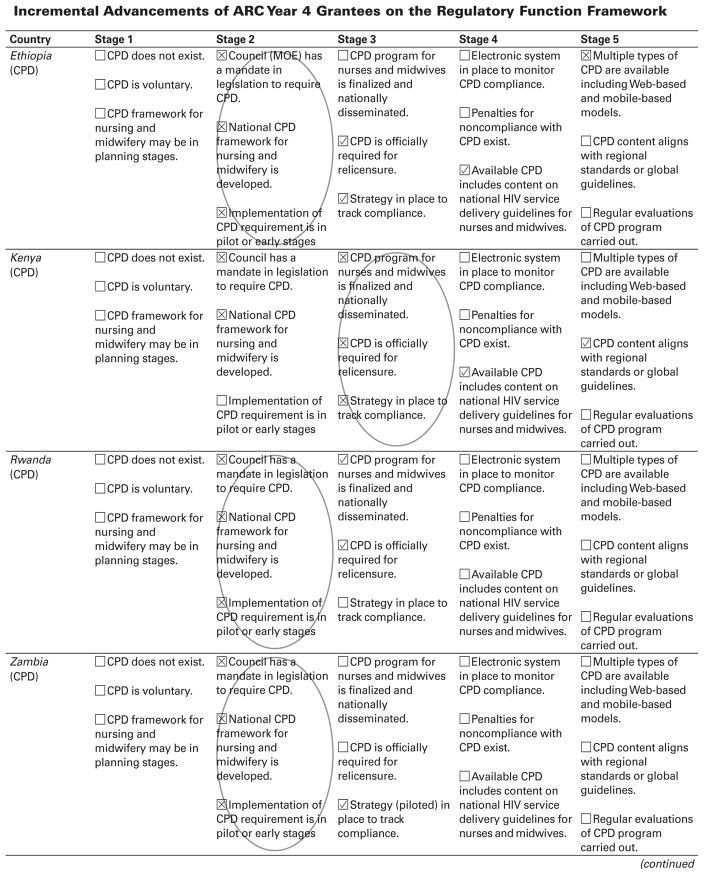

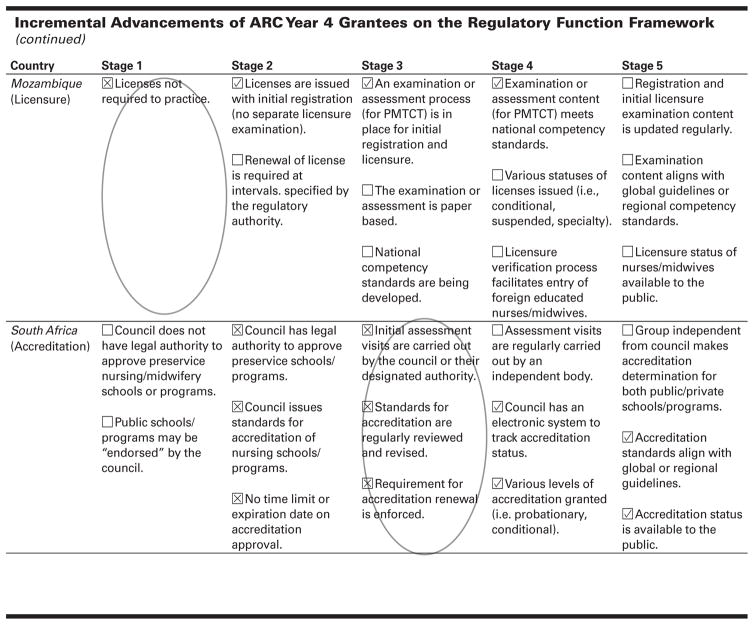

Whereas six countries remained in the same regulatory stage, all made incremental advancements. Figure 1 shows the countries’ RFF stage (i.e., circled) with incremental advancements during ARC Year 4 noted by check marks in stages following the circled stage. Specifically, Ethiopia reported that CPD is now officially required for licensure renewal with a strategy in place to track noncompliance. Ethiopia and Kenya both indicated that CPD content for nurses and midwives on national HIV service delivery guidelines is now available, and Kenya developed a nationally accredited CPD module on pediatric HIV care aligned with global guidelines. Mozambique introduced observed structured clinical examination in prevention of mother-to-child transmission for new nursing graduates as part of initial licensure and registration. Rwanda reported the finalization and implementation of their national CPD program with CPD now being officially required for licensure renewal. South Africa reported advancements in preservice nursing accreditation, including the development of an electronic system to track the accreditation process, standards for preservice nursing education aligned to global guidelines, and the public availability of institutions’ accreditation status. Zambia piloted a strategy to promote and track CPD compliance.

FIGURE 1. Incremental Advancements of ARC Year 4 Grantees on the Regulatory Function Framework.

☒ = Baseline at the beginning of ARC Year 4.

☑ = Incremental advancement by the end of ARC Year 4.

Note. ARC = African Health Profession Regulatory Collaborative; CPD = Continuing Professional Development; PMTCT = prevention of mother-to-child transmission.

Teamwork Among National Nursing Leaders

In reflecting on their teamwork before ARC involvement, country teams described a lack of systematic collaboration with occasional disagreements among leadership. Team members reported working in isolation from one another and communicating based on demands related to specific situations. Country teams noted the professional roles of other national nursing leaders and activities of their respective organizations were poorly understood. At the end of the 4-year ARC initiative, all but 2 participating country teams reported an increase in internal teamwork, with 6 teams reporting substantial increases. Country team rankings for teamwork among national nursing leaders before the ARC initiative were predominately described as “very weak” to “moderate” (13 countries) (Table 4). After ARC Year 4, country team rankings for teamwork among national nursing leaders were predominately described as “very strong” to “strong” (12 countries) (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Quad Rankings for Teamwork, Interorganizational Relationships, and Regional Networking

| Before ARC (# of Quads) | ARC at Year 4 (# of Quads) | |

|---|---|---|

| Teamwork Among National Nursing Leaders | ||

| Very strong | 1 | 5 |

| Strong | 1 | 7 |

| Moderate | 5 | 2 |

| Weak | 4 | 0 |

| Very weak | 4 | 0 |

| Not answered | 1 | 2 |

| Relationships Among Nursing Organizations | ||

| Very strong | 1 | 6 |

| Strong | 0 | 7 |

| Moderate | 10 | 2 |

| Weak | 2 | 0 |

| Very weak | 3 | 0 |

| Not answered | 0 | 1 |

| Regional Networking Opportunities | ||

| Many | 0 | 10 |

| Several | 1 | 5 |

| Some | 6 | 1 |

| Few | 8 | 0 |

| None | 1 | 0 |

| Not answered | 0 | 0 |

| Relationships with Other Organizations | ||

| Very strong | 0 | 7 |

| Strong | 2 | 4 |

| Moderate | 5 | 3 |

| Weak | 6 | 1 |

| Very weak | 2 | 0 |

| Not answered | 1 | 1 |

This improvement was typically characterized by the establishment of regular meetings and focused efforts to develop and work toward common goals. Some of these efforts led to the collaborative pursuit of projects and funding opportunities outside of ARC, including those supported by private-sector health facilities, national health ministries, and international organizations. All but 4 country teams reported an increase in non-ARC funding opportunities. Select examples of increased communication and collaboration are highlighted below.

Although we had no animosity, we worked in silos – each taking care of their own business and only consulting when needed. Now our teamwork is very strong and we tackle most nursing issues in unison. – Botswana

It is clear that unless we work together to advance regulatory systems, nursing and midwifery can be negatively affected. When we started working more closely as [a] Quad, we addressed professional and regulatory issues together. For example, we all felt and appreciated the big role we played in reviewing and revising the scope of practice for nurses and midwives in preservice and in-service HIV education. – Rwanda

Relationship Building between National Nursing Organizations

Similar to teamwork experiences among national nursing leaders, relationships between national nursing organizations before ARC were largely described as being “very weak” to “moderate” (15 countries) (Table 4). Participants characterized organizations as operating independently, with the goals and activities of each organization being unclear to members of other organizations and, in a few instances, with a lack of trust between organizations. At the end of ARC Year 4, all but 3 country teams described interorganizational relationships as “strong” or “very strong” (13 countries) (Table 4). This improvement probably represents a spillover effect from the improved teamwork among leadership and was apparent in descriptions of more mutual support, more effective communication, and better appreciation of organizational missions. Select examples of relationship building between national nursing organizations are highlighted below.

[ARC has facilitated] both collaboration and bonding between midwives and nursing associations, as well as with other academic sectors. – Ethiopia

[Before ARC], there was no communication between the [Chief Nursing Officer’s] office, regulation, and the schools. The Association was not supportive of council activities. All organizations now work together and support each other; since [forming the] ARC Quad, messages are disseminated across all of the organizations. – Lesotho

Relationship Building with Nonnursing Organizations

ARC supported broader stakeholder engagement to advance nursing and midwifery regulations. Before their involvement in the ARC initiative, 5 country teams reported having “moderate” relationships with nonnursing organizations operating in their countries, 6 reported these relationships were “weak,” and 2 reported “very weak” (Table 4). Team members described outreach efforts for collaboration with other organizations as being minimal, with a lack of recognition for what organizations might contribute to nursing and midwifery regulation, and sometimes with the assumption that these organizations have unrelated goals and agendas or lack interest in working to advance nursing and midwifery. After 4 years of ARC engagement, country teams reported having much stronger relationships with other national organizations, which include private health facilities, local CDC offices, local and international nongovernmental organizations (e.g., JHPIEGO, University Research Center), and United Nations organizations (e.g. World Health Organization [WHO], UNICEF, The World Bank). Seven countries reported “very strong” and 4 countries reported “strong” relationships with nonnursing oganizations nationally (Table 4). Select examples of relationship building with nonnursing organizations are highlighted below.

Our networks have increased beyond [the] Ministry of Health to other health professional groups, [nongovernmental organizations], and development partners. We have been able to form linkages for technical support and funding. – Botswana

We have formed collaborative ties with several other organizations involved in HIV/AIDS issues. – Zimbabwe

Regional Networking With Nursing Leaders from Other Countries

In addition to fostering teamwork among national leaders, ARC promoted cross-country collaboration between nursing and midwifery leaders in the ECSA region. Seven country teams reported having opportunities for regional networking with nursing leaders from other countries before ARC, and 9 reported having limited or no such opportunities (Table 4). In contrast, 10 country teams reported having “many” opportunities for networking at the end of ARC Year 4 (highest level of engagement) and 5 reported having “several” opportunities (Table 4). One country reported “some” opportunities. Country teams described how networking fostered the sharing of experiences and resources at triannual meetings (i.e., annual summative congress and two learning sessions). Nine country teams indicated using online networks that facilitated networking and collaboration, including the ECSA College of Nursing (ECSACON) website launched with ARC funding and the ARC Knowledge Gateway, a virtual community of practice built on a WHO open-source platform. Select examples of regional networking opportunities are highlighted below.

[Previously] we had limited forums to bring nurses together. ECSACON happens every two years. [The International Council of Nurses] and [International Confederation of Midwives] meetings also happen every two years but very few people can afford to attend. ARC created the opportunity for nurse leaders to meet regularly at the country level as well as at the regional level to discuss nursing issues. – Tanzania

Opportunities to network as Quad were [previously] limited; e.g., the Council was networking with ECSACON and ICN separately whilst the National Nurses Association was liaising with nongovernmental organizations locally and South African Development Community AIDS Network of Nurses and Midwives regionally. ARC has remarkably increased opportunities and avenues for networking. The establishment of the Knowledge Gateway website has broadened possibilities for accessing other country’s documents for the sharing of best practices. – Seychelles

Overall Experiences With ARC

Nearly all the country teams reported a positive overall experience with ARC. Fifteen country teams ranked their experience as “positive” or “extremely positive”; 1 country reported a “neutral” experience. In describing these experiences, all country teams reiterated their appreciation for increased collaboration and networking opportunities. Other benefits commonly noted included strengthened nursing regulatory functions and improved capacity in terms of proposal writing and project implementation. Looking to the future, country teams noted their desire for increased funding and larger grants, an expansion of focus to include noncommunicable disease, and more training and capacity building for implementation research and quality improvement. Select examples of ARC experiences are highlighted below.

ARC has helped us to achieve many things related to the strengthening of regulatory functions. As a Quad, we are able to write a grant proposal, implement our project, and evaluate it – as well as manage donor funding. ARC has also opened up many opportunities for collaboration within the region. – Zambia

ARC has motivated and encouraged us. As a part of ARC, we have attended conferences that have helped us to understand the essential responsibilities of each Quad member and have brought us together to work as a team. We’ve learned and shared experiences with other ARC countries, and are confident that we will start our regulatory function in a more fully developed manner. – South Sudan

Discussion

The findings from ARC Year 4 demonstrate rapid, breakthrough change over a 1-year period, as multiple countries advanced their regulatory frameworks. Three countries (Lesotho and Zimbabwe for CPD, Botswana for SOP) ended the project year in a state of optimized regulatory function that aligns with global and regional standards (stage 5). Furthermore, two countries (Tanzania and Seychelles for their development of national CPD programs) advanced one full stage within the framework over the same 1-year period. Notable incremental advancements over the course of the year were also present; two countries officially adopted CPD requirements for licensure renewal (Ethiopia and Rwanda) and one (South Africa) introduced accreditation for HIV care as a specialty amongst nurse providers.

Although 6 countries did not advance a stage on the RFF, several considerations exist. To progress a stage on the RFF, countries must meet all of their criteria for that specific stage. Although Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Zambia, Mozambique and South Africa all made incremental advancements (Figure 1), they did not meet all the criteria to advance to the subsequent stage. This finding highlights limitations with the RFF tool, which describes cross cutting regulatory functions but lacks the granularity to measure more nuanced change. For example, the RFF tool does not capture the introduction of accreditation for HIV/TB nurses as a specialty, which is a significant advancement. Instead, the tool measures the accreditation of preservice programs. Other context-specific barriers likely exist; however, more research would be needed to identify their causes.

The ARC model worked well in the ECSA region where national nursing organizations previously existed in most countries with a moderate baseline capacity. ARC harnessed existing national nursing structures to advance nursing workforce capacity in HIV care, specifically NIMART. Where national nursing structures were lacking, as in Mozambique, ARC provided technical assistance that informed the development of their first national nursing and midwifery act, which was signed into law in 2015 providing the legal mandate to establish a nursing council. Collaborative approaches, using twinning or cross-country communities of practice, to share resources and lessons learned have worked well to strengthen preservice education to ensure a fit-for-purpose health workforce (Palsdottir et al., 2016). This cross-country, collaborative approach promoted efficient regulatory advancements to ensure a more relevant nursing and midwifery workforce, authorized and equipped to practice NIMART.

Based on recommendations from the ARC Year 3 evaluation (Dynes et al., 2016), the RFF tool (McCarthy, et al., 2014) was adapted to enhance the data collection process and a mixed-methods questionnaire was administered to document and elucidate advances in national nursing leadership capacity. The adapted RFF tool (Table 1) more accurately captured the regulatory progress of each country team, improving data collection and analysis. In addition, the mixed-methods questionnaire yielded information on improvements in team work and collaboration among national nursing and midwifery leadership teams. Previous anecdotal feedback from ARC participants suggested improved collaboration between Quad members and their organizations; however, this questionnaire offered the first opportunity to capture these advancements in national nursing capacity.

Results captured by the nursing leadership evaluation tool indicate growth and capacity building throughout the 4-year project period. Although country teams made clear advancements in their teamwork, fundraising, organizational collaboration and regional networking over the ARC initiative, further research is needed to identify specific factors in the ARC intervention that contributed to this growth. Factors like the number of seed grants received and the frequency, amount, and nature of technical assistance provided are likely influential in countries’ increased capacity. These relationships should be explored in future research and could have programmatic implications for other initiatives in the region targeting national nursing leadership. Lessons learned and technical approaches from the ARC model could be translated to other professional realms or regions beyond nursing in the ESCA region.

Increases in teams’ national leadership capacity could yield benefits beyond the initial advancements in nursing regulatory functions. For instance, enhanced capacity for regional and national networking and business development functions, such as grant proposal writing and management of funds, are translatable skills identified by the country teams as having improved as a result of participation in ARC. In this way, the initial benefit of ARC to advance nursing regulation specific to HIV could have farther reaching effects to improve the quality of nursing practice in other areas. Botswana, for example, decided to draft its first-ever national strategy for nursing and midwifery. Enhanced capacity among national nursing and midwifery leadership teams demonstrates sustainability of the project’s effects beyond its initial implementation.

Across the ECSA region, nursing policy and practice are often not aligned. For example, nurses may practice NIMART without formal authorization in their SOP or through a national task sharing policy, given the patient demand. Alternately, nurses may be authorized to practice NIMART through a country’s national ART treatment guidelines; however, the nurses and midwives may not possess the required competencies to confidently initiate pediatric patients on ART. Although ARC worked to address these disparities, we acknowledge the numerous contributions by national governments, PEPFAR, and other donors occurring simultaneously. The targeted ARC Year 4 investments are clearly defined in Table 2, where each country’s project achievements are described linked to a specific regulatory function with relevant stage (Table 3) or incremental (Figure 1) advancements noted using the RFF. Further research is needed to identify specific factors (e.g., grants, technical assistance, learning sessions, improved leadership capacity) that contributed to countries’ regulatory advancements.

Conclusion

Regulation is an important mechanism to ensure the health work-force is authorized and equipped to deliver safe, high-quality servies that are relevant to the public’s evolving health needs. The ARC initiative proved to be an effective model to promote rapid regulatory advancements and improve the capacity of national nursing institutions. National regulatory boards and councils will continue to implement and advance these regulations, highlighting the sustainability of this investment. Other health professional cadres, such as mid-level care providers, or regions, like Southeast Asia or Francophone West Africa, may consider using collaborative models to advance national regulatory reforms, as they work to ensure the health workforce is equipped to meet the ever-evolving demand for health services.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) under the terms of a cooperative agreement with the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health (ASPPH) grant number 1U36OE000002. The findings and conclusions of this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC. This evaluation was supported by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN).

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the nursing and midwifery leadership teams across the ECSA region, especially their dedication to advancing the authorization and competency of the nursing workforce to support HIV epidemic control. The authors also acknowledge the staff support provided by the 15 CDC country offices to national nursing leaders as they worked to advance nursing regulations, including Dr. Fatma Soud and Dr. Peter Chipimo from CDC Zambia, and Dr. Patricia Oluoch, Dr. Abraham Katana, Dunstan Achwoka, and Dr. Lucy Ng’Ang’A from CDC Kenya. Acknowledgements are given to Angel Mendonça (JHPIEGO), Moises Matsinhe, and Hamido Braimo (ICAP), and Alfredo Vergara and Sonia Machaieie (CDC Mozambique) for their support of the nursing leaders in Mozambique to implement OSCE for new graduates and advance the national nursing act. We give special thanks to Michelle Dynes (CDC) for the initial development of the evaluation tool to measure changes in nursing and midwifery leadership capacity.

Footnotes

Botswana, Ethiopia, Kenya, Lesotho, Mozambique, Seychelles, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe; Rwanda received a grant but was not able to attend the meeting and completed the group survey electronically.

Botswana, Ethiopia, Kenya, Lesotho, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Rwanda (electronically following the meeting), Seychelles, South Africa, South Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

Contributor Information

Maureen A. Kelley, Former Principal Investigator for the African Health Profession Regulatory Collaborative (ARC) and Clinical Professor Emeritus at Emory University’s Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Atlanta, GA.

Sydney A. Spangler, Co-Principal Investigator for ARC and Assistant Clinical Professor at Emory University’s Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing.

Laura I. Tison, Public Health Analyst in the HIV Care and Treatment Branch at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, GA.

Carla M. Johnson, Nurse Consultant in the HIV Care and Treatment Branch at the CDC.

Tegan L. Callahan, Health Scientist in the Maternal and Child Health Branch at the CDC.

Jill Iliffe, Executive Secretary for the Commonwealth Nurses and Midwives Federation, London, England.

Kenneth W. Hepburn, Principal Investigator for ARC and a Professor at Emory University’s Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing.

Jessica M. Gross, Senior Nursing Advisor in the Division of Global HIV and TB at the CDC.

References

- Benton DC, Gonzalez-Jurado MA, Beneit-Montesinos JV. Defining nurse regulation and regulatory body performance: A policy Delphi study [Epub April 9, 2013] International Nursing Review. 2013;60(3):303–312. doi: 10.1111/inr.12027. doi:310.1111/inr.12027. Epub 12013 Apr 12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan AT, Long L, Maskew M, Sanne I, Jaffray I, MacPhail P, Fox MP. Outcomes of stable HIV-positive patients down-referred from a doctor-managed antiretroviral therapy clinic to a nurse-managed primary health clinic for monitoring and treatment. AIDS. 2011;25(16):2027–2036. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834b6480. doi:2010.1097/QAD.2020b2013e32834b36480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke D. Law, regulation and strategizing for health. In: Schmets G, Rajan D, Kadandale S, editors. Strategizing national health in the 21st century: A handbook. Chapter 10. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/250221/1/9789241549745-chapter10-eng.pdf?ua=1/ [Google Scholar]

- Clarke D, Duke J, Wuliji T, Smith A, Phuong K, San U. Strengthening health professions regulation in Cambodia: A rapid assessment. Human Resources for Health. 2016;14:9. doi: 10.1186/s12960-12016-10104-12960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dynes M, Tison L, Johnson C, Verani A, Zuber A, Riley PL. Regulatory advances in 11 sub-saharan countries in year 3 of the African Health Profession Regulatory Collaborative for Nurses and Midwives (ARC) Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2016;27(3):285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J, McCarthy C, Kelley M. Strengthening nursing and midwifery regulations and standards in Africa. African Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2011;5(4):185–188. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JM, Kelley MA, McCarthy CF. A model for advancing professional nursing regulation: The African Health Profession Regulatory Collaborative. Journal of Nursing Regulation. 2015;6(3):29–33. doi: 10.1016/S2155-8256(15)30790-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The breakthrough series: IHI’s collaborative model for achieving breakthrough improvement. Boston, MA: Author; 2003. Retrieved from http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/TheBreakthroughSeriesIHIsCollaborativeModel-forAchievingBreakthroughImprovement.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Joint Learning Initiative. Human resources for health: overcoming the crisis. 2004 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17482-5. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/hrh/documents/JLi_hrh_report.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kredo T, Adeniyi FB, Bateganya M, Pienaar ED. Task shifting from doctors to non-doctors for initiation and maintenance of antiretroviral therapy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;(7):CD007331. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007331.pub3. 007310.001002/14651858.CD14007331. pub14651853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long L, Brennan A, Fox MP, Ndibongo B, Jaffray I, Sanne I, Rosen S. Treatment outcomes and cost-effectiveness of shifting management of stable ART patients to nurses in South Africa: An observational cohort. PLoS Medicine. 2011;8(7):e1001055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001055. doi:1001010.1001371/journal.pmed.1001055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy CF, Kelley MA, Verani AR, St Louis ME, Riley PL. Development of a framework to measure health profession regulation strengthening. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2014;46:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy CF, Riley PL. The african health profession regulatory collaborative for nurses and midwives. Human Resources for Health. 2012;10:26. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-10-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy CF, Zuber A, Kelley MA, Verani AR, Riley PL. The African Health Profession Regulatory Collaborative (ARC) at two years. African Journal of Midwifery and Womens Health. 2014;8(Suppl 2):4–5. doi: 10.12968/ajmw.2014.8.sup2.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palsdottir B, Barry J, Bruno A, Barr H, Clithero A, Cobb N, … Worley P. Training for impact: The socio-economic impact of a fit for purpose health workforce on communities. Human Resources for Health. 2016;14(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s12960-12016-10143-12966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulk MC, Weber CV, Curtis B, Chrissis MB, editors. The capability maturity model: Guidelines for improving the software process, reading. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Penazzato M, Davies MA, Apollo T, Negussie E, Ford N. Task shifting for the delivery of pediatric antiretroviral treatment: a systematic review. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2014;65(4):414–422. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000024. doi:410.1097/QAI.0000000000000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Professional Standards Authority. Right-touch regulation revised. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.professionalstandards.org.uk/docs/default-source/publications/thought-paper/right-touch-regulation-2015.pdf?sfvrsn=12.

- United Nations. Sustainable development goals: 17 goals to transform our world. 2017 Retrieved from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/

- World Health Assembly. WHA 59.23: Rapid scaling of health workforce production. 2006 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/WHA_59-23_EN.pdf?ua=1.

- World Health Assembly. WHA Resolution 66.23: Transforming health workforce education in support of universal health coverage. 2013 Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA66/A66_R23-en.pdf.

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2006: Working together for health. 2006 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/whr/2006/en/

- World Health Organization. Scaling up, saving lives. 2008 Retrieved from Global Health Workforce Alliance http://www.who.int/work-forcealliance/documents/Global_Health%20FINAL%20REPORT.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Report on the WHO/PEPFAR planning meeting on scaling up nursing and medical education. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.hrhresourcecenter.org/node/2979.

- World Health Organization. Transforming and scaling up health professionals education and training: World Health Organization guidelines 2013. 2013 Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/93635/1/9789241506502_eng.pdf. [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global strategy on human resources for health: Workforce 2030. 2016a Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/250368/1/9789241511131-eng.pdf?ua=1.

- World Health Organization. Working for health and growth: Investing in the health workforce. Report of the High-Level Commission on Health and Economic Growth. 2016b Retreived from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/250047/1/9789241511308-eng.pdf?ua=1.