Abstract

Social networking sites (SNSs) are social platforms that facilitate communication. For adolescents, peers play a crucial role in constructing the self online through displays of group norms on SNSs. The current study investigated the role of online social identity (OSI) in the relationship between adolescent exposure to alcohol-related content posted by peers on SNSs and alcohol use. In a sample (N = 929) of Australian adolescents (Age M = 17.25, SD = 0.31) higher levels of exposure to alcohol-related content on SNSs was associated with higher levels of alcohol use. Importantly, the association was stronger when the participants reported higher OSI particularly when also reporting low or moderate amount of time spent on SNS. The findings can be explained by social identity literature that demonstrates individuals align their behaviors with other members of their social group to demonstrate, enact, and maintain social identity. The results of this study reflect the importance of considering the construction of the “self” through online and offline constructs.

Keywords: : online social identity, social networking sites, alcohol use

Introduction

Social networking sites (SNSs) are a form of communication technology that enables social interactions in an online environment; examples include Facebook, Twitter, and Myspace.1 While SNSs provide platforms for peer interaction for a wide cross-section of people, adolescents in particular are heavy users of these sites, with up to 92% of Australian adolescents owning a SNS profile.2 Given their use for peer interactions, SNSs are an important medium through which adolescents develop social identities,3–6 and it is important to understand this process because developing and defining social identity is fundamental for constructing the self, and accordingly, influencing behaviors, during adolescence.7,8 The present study focuses on the role of online social identity (OSI) in the relationship between exposure to alcohol-related content on SNSs and the offline behavior of adolescent alcohol use, beginning with a review of how adolescents use SNSs to construct the self online.

Constructing the self on social networking sites

For adolescents, physical and developmental changes coincide with constructing and navigating expanding repertoires of identity. As young people confront, explore, and seek to understand their place in the world, social identities can play a significant role by presenting and demarcating acceptable or prescribed norms and behaviors within important peer group settings.6–8 The social identity approach seeks to explain why, how, and when individuals think, feel, and act in group terms; that is, the influence of the social on the individual. Social identity posits an individual self-concept manifested through a dynamic relationship between multiple personal and social identities, wherein personal/social identity salience (and consequently behavior) can ebb and flow influenced by perceptions and experiences of context or situation.9,10

Accordingly, OSI is grounded in the realization that the online realm is a social medium. While individuals may be physically alone when interacting online, psychologically, their online experiences are often explicitly social. Individuals create and share content, engage in political discussions, play multiplayer games, and take part in a host of other explicitly social activities.11 Simply put, online social identities are self-concepts that result through identification with social groups or categories that individuals experience online. From the social identity approach, it follows that such identities are dynamic (become more or less salient depending on context), and have the potential to influence thought, emotion, and behavior, both online and offline. Importantly, distinguishing online from offline social identity is not an assertion that one is more real or valid than the other, but rather, given the growth of online interaction, it is worthwhile expanding our view of social identities to include online social contexts.

Technologies and popular media are common sources from which young people draw important markers that define boundaries and content of identity,12 and new and developing online technologies play an important role in influencing how young people experience, express, and enact their social and personal selves.13 SNSs demonstrate that influence. Research suggests that adolescents' use of SNSs has consequences for how they think about themselves and their relevant peers14 and shapes their perceptions of group norms and behavioral intentions.15,16

Although researchers have explored links between adolescents' SNS use and alcohol consumption, and have also conceptualized those links in terms of social identity, measurements of SNS social identity have commonly been constructed by classifying the content of young people's social network interactions;17,18 generally, systematic scale-based measures of OSI have not been deployed (although see Shen, Yu and Khalifa19). This study sought to measure OSI relevant to adolescents' SNS use through a theoretically derived scale, and test the role of such an identity in young people's propensity to align their own drinking behavior with alcohol use content they see online.

A significant body of work supports conceptualizing social identity as a multidimensional construct, where social identification can best be understood and measured across multiple dimensions or factors representing different aspects of identification.20 That work is ongoing, but Cameron's21 three-factor model of social identity has found support as an effective assessment framework,22 and has been used and adapted in a variety of contexts. Cameron's model describes three components: centrality—frequency of thoughts about being a group member; satisfaction—positive feelings about a group; and in-group ties—perceptions of bonds between group members. The present study adapted three items from Cameron's measure; two measuring centrality and one measuring satisfaction, to form a measure of OSI.

Exposure to alcohol-related content and adolescent alcohol use

Alcohol-related content, in the form of pictures or text posts, is common on SNSs and typically conveys positive attitudes toward alcohol.23 For adolescents and young adults, exposure to alcohol-related content on SNSs is related to higher rates of alcohol use.15,17,24–27 For example, in research that investigated young people's SNS and alcohol use, Beullens and Vandenbosch15 found that adolescents' exposure to SNS content depicting alcohol influenced their perceptions of norms about alcohol and thus predicted actual alcohol use intentions.

Similarly, Ridout et al.17 explained their finding of a link between young adult's presentation of alcohol-related behaviors in social media profiles and actual alcohol use in terms of an alcohol-identity construct, suggesting such online behaviors normalize actual alcohol consumption. A recent review article by Westgate and Holliday28 also highlighted the importance that alcohol identity and group influence may have in the relationship between exposure to alcohol-related content on SNS and alcohol use. In line with the social identity approach, it is apparent that the consequences of SNSs are not only limited to the online realm, but also affect offline social group norms that in turn can influence attitudes and behaviors.

It seems reasonable then to expect the relationship between exposure to alcohol-related content and alcohol use to be conditional on the degree of identification with online social groups (as measured by OSI). That is to say, to maintain consistency with an OSI, adolescents may align their behavior with that of the group norms set by peers posting alcohol-related content on SNSs. Indeed, in social identity theory, group norms are a contributing factor to the behavior change necessary to reflect group membership.10

Following the theory of normative social behavior,29 descriptive and injunctive norms have been applied to understand the interaction between perceived group norms and young adults' alcohol use. They suggested that, in the case of alcohol use, when a referent peer is perceived to engage in drinking alcohol (descriptive norm), a young adult is more likely to engage in drinking alcohol, particularly when they perceive the referent peer to expect that behavior (injunctive norm).29 Thus, if an adolescent views alcohol-related content posted by members of their online social group (referent peers), they will be more likely to engage in alcohol use if their membership in that online social group is central to their self-concept (i.e., expectations of other members is important).

The current study proposes that the relationship between exposure to alcohol-related content that is posted online by peers and alcohol use will be stronger for adolescents who report higher OSI. The conditional relationship may be dependent on intensity of SNS use, as research indicates that both SNS content and intensity of SNS use are related to higher alcohol use.30

Methods

Participants

Data came from the Youth Activity Participation Survey of Western Australia. Participants were 929 year 12 students (54.5% female) from 33 high schools (73.2% metropolitan, 26.8% regional). The adolescents ranged from 16 to 18 years of age (M = 17.25, SD = 0.31). Only 843 participants who reported having created a SNS (90.7%, 55.5% female) were included in the analyses.

Materials and procedure

Data used in this study were collected in 2014. During a classroom session, participants were allotted 45 minutes to complete the survey using either iPads or paper and pencil. Ethical approval to conduct research was obtained from the university Human Research Ethics Committee, the Catholic Education Office, and the Education Department. Participation in the study required informed consent from parents and students.

Measures

Alcohol use

Three items adapted from the alcohol scale in Fredricks and Eccles31 were used to assess alcohol use. The questions asked how often in the previous 6 months participants had drunk alcohol, been drunk, and consumed more than five drinks on one occasion. Responses were entered on an eight-point scale (1 = None to 8 = 31 or more times). A mean of the three items (α = 0.94) was computed.

SNS alcohol exposure

SNS Alcohol Exposure was measured by a single item asking participants how often in the previous 6 months their friends posted pictures, updates, or wall posts that showed or talked about them drinking alcohol. Responses were recorded on an eight-point scale (1 = None to 8 = 31 or more times).

Online social identity

The mean of three items that were developed by Cameron21 were used to measure OSI. The items were “Being a member of my on-line social network is an important reflection of who I am” (centrality), “In general, being a member of my on-line social network is an important part of my self-image” (centrality), and “Generally, I feel good when I think about myself as a member of my on-line social network” (satisfaction). Responses were coded on a seven-point scale (1 = completely disagree to 7 = completely agree). The scale was reliable (α = 0.90).

SNS intensity

SNS Intensity was measured with a single item asking how many hours per week the participants spent on SNS with response options ranging from 0 hours per week to 30 hours or more per week.

Results

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (v. 23) using listwise deletion to deal with missing data (5.9%). Descriptive statistics and correlations between Alcohol Use, SNS Alcohol Exposure, OSI, and SNS Intensity can be found in Table 1. The bivariate correlations among Alcohol Use, SNS Alcohol Exposure, OSI, and SNS Intensity were all positive and significant. These correlations indicate participants who reported higher levels of OSI also reported higher levels of Alcohol Use, SNS Alcohol Exposure, and SNS Intensity.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Pearson Correlations Between Alcohol Use, SNS Alcohol Exposure, Online Social Identity, and SNS Intensity for the Participants Who Have a SNS Profile (N = 793)

| Mean (SD) | 1. | 2. | 3. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Alcohol use | 2.55 (1.80) | — | ||

| 2.Alcohol exposure | 4.18 (2.29) | 0.41a | — | |

| 3.OSI | 2.52 (1.42) | 0.24a | 0.19a | — |

| 4.SNS frequency of use | 8.65 (8.32) | 0.22a | 0.22a | 0.17a |

Significance at the p < 0.001 level.

OSI, online social identity; SNS, social networking sites.

Moderated regression

A moderated regression analysis (Table 2) was conducted to test SNS Alcohol Exposure, OSI, and SNS Intensity as predictors of Alcohol Use. All interaction terms were calculated using mean-centered variables. At the first step of the analysis, SNS Alcohol Exposure, OSI, SNS Intensity, and gender explained 21.2% of the variance in Alcohol Use (F[4, 788] = 52.97, p < 0.001). All variables, with the exception of gender, made a significant and unique contribution to the model and were positively associated with Alcohol Use. SNS Alcohol Exposure was the strongest predictor explaining a unique 11.9% of Alcohol Use. The more reported posts about alcohol made by peers on SNSs, the greater the reported alcohol consumption.

Table 2.

A Moderated Multiple Regression Analysis Investigating the Association of SNS Alcohol Exposure, Online Social Identity, SNS Intensity, and Gender with Alcohol Use (N = 793)

| CI (B)95% | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | B (SE) | Lower | Upper | β | sr2% |

| Step 1 | |||||

| SNS Alcohol Exposure | 0.28 (0.03) | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.36a | 11.90 |

| OSI | 0.19 (0.04) | 0.10 | 0.27 | 0.15a | 1.96 |

| SNS Intensity | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.13a | 1.46 |

| Genderc | 0.11 (0.11) | −0.11 | 0.33 | 0.03 | 0.10 |

| Step 2 | |||||

| SNS Alcohol Exposure | 0.28 (0.03) | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.36a | 11.70 |

| OSI | 0.17 (0.04) | 0.08 | 0.25 | 0.13a | 1.49 |

| SNS Intensity | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.14a | 1.74 |

| Genderc | 0.10 (0.11) | −0.13 | 0.32 | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| SNS Alcohol Exposure × OSI | 0.04 (0.02) | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.09b | 0.64 |

| SNS Alcohol Exposure × SNS Intensity | 0.00 (−0.01) | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.10 |

| OSI × SNS Intensity | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.15 |

| Step 3 | |||||

| SNS Alcohol Exposure | 0.29 (0.03) | 0.24 | 0.34 | 0.37a | 12.25 |

| OSI | 0.18 (0.04) | 0.10 | 0.26 | 0.14a | 1.69 |

| SNS Intensity | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.15a | 2.05 |

| Genderc | 0.11 (0.11) | −0.11 | 0.33 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| SNS Alcohol Exposure × OSI | 0.05 (0.02) | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.09b | 0.67 |

| SNS Alcohol Exposure × SNS Intensity | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.06 |

| OSI × SNS Intensity | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.00 |

| SNS Alcohol Exposure × OSI × SNS Intensity | −0.01 (0.00) | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.10b | 0.72 |

Significance at the p < 0.001 level.

Significance at the p < 0.05 level.

0 = Female, 1 = Male.

The addition of three two-way interaction terms in the second step of the analysis explained an additional 0.8% of the variance in Alcohol Use (Fchg [3, 785] = 2.75, p = 0.041). The only interaction term that was uniquely significant was the SNS Alcohol Exposure by OSI interaction term indicating that the link between SNS Alcohol Exposure and Alcohol Use was conditional on the level of OSI. At the third step of the analysis, a three-way interaction term comprising of SNS Alcohol Exposure by OSI by SNS Intensity was added to the analysis and explained a significant 0.7% of the variance (Fchg [1, 784] = 7.27, p = 0.007) indicating that the conditional effect was significantly moderated by SNS Intensity.

To investigate the significant three-way interaction, simple slopes analysis was conducted using Hayes32 SPSS macro PROCESS. The SNS Alcohol Exposure by OSI interaction was investigated at different levels of SNS Intensity. The pick-a-point technique was used to conduct the simple slopes analysis with high and low values for SNS Alcohol Exposure, OSI, and SNS Intensity being one standard deviation above and below the mean, respectively, and the moderate values were the mean. The relationship between SNS Alcohol Exposure and Alcohol Use was conditional on OSI at low (B = 0.09, p < 0.001) and moderate (B = 0.05, p = 0.009) levels of SNS Intensity, but not at high levels of SNS Intensity (B < 0.01, p = 0.91).

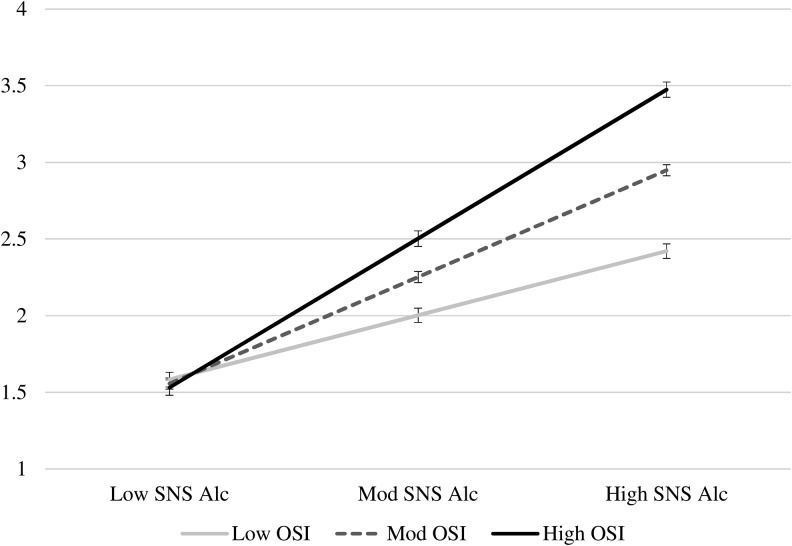

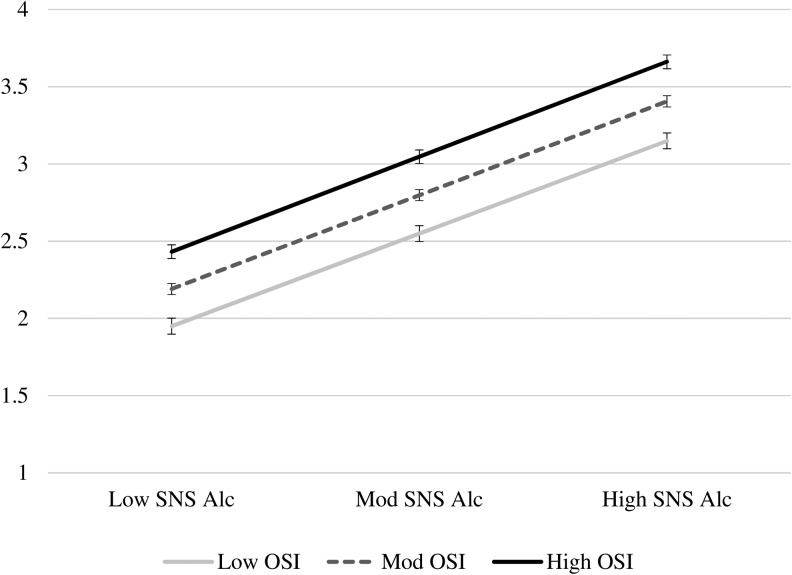

At low levels of SNS Intensity, the strength of the relationship between SNS Alcohol Exposure and Alcohol Use was dependent on the level of OSI (Fig. 1). At low levels of OSI (B = 0.18, p < 0.001), the relationship between SNS Alcohol Exposure and Alcohol Use was weaker than the relationship at moderate (B = 0.30, p < 0.001) and high levels of OSI (B = 0.43, p < 0.001). Similarly, at moderate levels of SNS Intensity, the relationship between SNS Alcohol Exposure and Alcohol Use was weaker at low levels of OSI (B = 0.22, p < 0.001) than moderate (B = 0.29, p < 0.001) and high (B = 0.35, p < 0.001) levels of OSI. At high levels of SNS Intensity (Fig. 2), the conditional effect of OSI was not significant as can be seen by the lack of significant differences in the relationships between SNS Alcohol Exposure and Alcohol Use irrespective of whether there was low (B = 0.26, p < 0.001), moderate (B = 0.27, p < 0.001), or high (B = 0.27, p < 0.001) levels of OSI. Therefore, adolescents who reported being exposed to more alcohol-related content on SNSs also reported more alcohol use. An important condition to that relationship is that the relationship was stronger when OSI was higher, but only when the participants spent low or moderate levels of time on SNS per week.

FIG. 1.

The conditional relationship between SNS Alcohol Exposure (SNS Alc) and alcohol use at low, moderate, and high levels of online social identity (OSI) at low SNS Intensity. Error bars depict standard error. SNS, social networking sites.

FIG. 2.

The conditional relationship between SNS Alcohol Exposure (SNS Alc) and alcohol use at low, moderate, and high levels of OSI at high SNS Intensity. Error bars depict standard error.

Discussion

A strong relationship between exposure to alcohol-related content on SNS and alcohol use has been reported in the literature.15,17,24–27 In light of the serious implications that adolescent alcohol use can have for adolescent development,15 this study sought to better understand potential individual vulnerabilities to the relationship between alcohol-related content on SNS and alcohol use, with a focus on adolescent identification with online social groups. The results demonstrated that the relationship between exposure to alcohol-related content on SNS and alcohol use was conditional on both the level of OSI and SNS intensity. Consistent with previous research, more exposure to alcohol-related content was associated with greater alcohol use in adolescents; however, the association was stronger for participants reporting higher OSI particularly in conditions of low or moderate levels of time spent on SNS.

The findings support the prediction that the relationship between exposure to alcohol-related content and alcohol use is stronger for those with higher OSI, consistent with literature suggesting members of a social group demonstrate social identity by aligning behavior with the perceived social norms of their group.9,10,15,16 Thus, our results suggest that adolescents with low or moderate SNS use may have aligned their alcohol use to the perceived alcohol-related norms of their online social group. However, for adolescents with high SNS use, the relationship between exposure to alcohol-related content and alcohol use did not significantly differ among those varying in strength of OSI. Research exploring exposure to alcohol-related content on other media (e.g., movies, television, music videos) has found that higher levels of exposure contributed to higher levels of alcohol use.33–35 Our results indicate two conditional main effects that remained significant in the presence of the significant interaction, with both exposure to alcohol online and time spent online predicting higher levels of alcohol use. It is possible that the present study reveals a “ceiling” effect, whereby high exposure to alcohol-related content through greater SNS use contributes to alcohol use irrespective of OSI.

Recently, Westgate and Holliday28 proposed that identity and influence may partly explain the relationship between exposure to alcohol-related content online and alcohol use, suggesting “people's self-representations on social media accurately reflect offline behaviors.” The present study extends that idea to include not only self presentation, but also adolescents' internalized view of their place in the online social milieu, highlighting the importance of considering social identity on SNS. A starting point in tapping into the construct of social identity connected to SNSs was to develop an operative measure of OSI. Our measure included two components of a three-component social identity measure,21 and further research is needed to explore the utility of adding an in-group ties component. Nevertheless, our adapted measure of OSI introduces a novel construct to measure how adolescents understand their social selves online, and revealed how the online self influences offline alcohol use.

There are two key limitations to the current study. Due to the cross-sectional design, causality cannot be inferred from the associations tested. All directionality inferred is in relation to previous research on social identity, alcohol use, and alcohol-related content on SNS. To overcome this limitation, future research should employ a longitudinal design. Additionally, further research should also investigate and compare the relationships between offline and online identity and exposure to alcohol, and their influence on alcohol use to disentangle the effects of SNS-based peer influence from that experienced in the offline world.

This study revealed the value of considering OSI with factors related to the content of and exposure to SNS in predicting drinking behavior. As the relationship between alcohol-related content on SNS and adolescent alcohol use is frequently cited as a public health concern by both researchers and public health officials,15,36 our findings may offer insights about which adolescents might benefit more from interventions focused on preventing adolescent alcohol use through pathways related to SNS use. A strong disposition to identify with members of a social network may incline some young people to take up offline behaviors they see modeled online. Clinicians and educators working with vulnerable young people may need to engage with perceptions related to online selves in endeavors to prevent risky levels of alcohol consumption and to offer support for alternative expressions of alignment to online social norms. In sum, the current study acknowledges OSI as a measurable construct which, in light of its relationship with exposure to alcohol-related content and alcohol use, warrants consideration in future research and prevention efforts.

Acknowledgments

The Youth Activity Participation Study of Western Australia (YAPS-WA) was supported through three Grants under the Australian Research Council's Discovery Projects funding scheme: DP0774125 and DP1095791 to Bonnie Baber and Jacquelynne Eccles, and DP130104670 to Bonnie Barber, Kathryn Modecki, and Jacquelynne Eccles. The authors would like to thank all high school principals, staff, and students who took part in the YAPS-WA study. They would also like to thank everyone from the YAPS-WA team.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Lenhart A. (2015) Teens, social media and technology overview. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center [Google Scholar]

- 2.Australian Media Communication Authority. (2013) Like, post, share: young Australians' experience of social media. Belconnen, ACT, Australia: www.acma.gov.au/~/media/mediacomms/Report/pdf/Like%20post%20share%20Young%20Australians%20experience%20of%20social%20media%20Quantitative%20research%20report.pdf (accessed May24, 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker V. Older adolescents' motivations for social network site use: the influence of gender, group identity and collective self-esteem. Cyberpsychology and Behavior 2009; 12:209–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borca G, Bina M, Keller PS, et al. Internet use and developmental tasks: adolescents' point of view. Computers in Human Behavior 2015; 52:49–58 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyd DM, Ellison NB. Social network sites: definition, history and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 2008; 13:210–230 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis K. Friendship 2.0: adolescents' experiences of belonging and self-disclosure online. Journal of Adolescence 2012; 35:1527–1536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erikson EH. (1968) Identity, youth, and crisis. New York: W. W. Norton [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pugh MJV, Hart D. Identity development and peer group participation. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 1999; 84:55–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reicher S, Spears R, Haslam SA. (2010) The social identity approach in social psychology. In: Wetherell M, Mohanty CT, eds. The SAGE handbook of identities. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, pp. 45–62 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turner JC, Onorato RS. (1999) Social identity, personality, and the self-concept: a self-categorization perspective. In: Tyler TR, Kramer RM, John OP, eds. The psychology of the social self. Berkeley CA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 11–46 [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKenna KY, Bargh JA. Plan 9 from cyberspace: the implications of the Internet for personality and social psychology. Personality and Social Psychology Review 2000; 4:57–75 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnett JJ. Adolescents' uses of media for self-socialization. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 1995; 24:519–533 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Livingstone S. (2011) Internet, children, and youth. In Consalvo M, Ess C, eds. The handbook of internet studies. Oxford, United Kingdom: Wiley Blackwell Publishing, pp. 348–368 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blomfield CJ, Barber BL. Social networking site use: linked to adolescents' social self-concept, self-esteem, and depressed mood. Australian Journal of Psychology 2014; 66:56–64 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beullens K, Vandenbosch L. A conditional process analysis on the relationship between the use of social networking sites, attitudes, peer norms, and adolescents' intentions to consume alcohol. Media Psychology 2016; 19:310–333 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffiths R, Casswell S. Intoxigenic digital spaces? Youth, social networking sites and alcohol marketing. Drug and Alcohol Review 2010; 29:525–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ridout B, Campbell A, Ellis L. “Off your Face (book)”: alcohol in online social identity construction and its relation to problem drinking in university students. Drug and Alcohol Review 2012; 31:20–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao S, Grasmuck S, Martin J. Identity construction on Facebook: digital empowerment in anchored relationships. Computers in Human Behavior 2008; 24:1816–1836 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen KN, Yu AY, Khalifa M. Knowledge contribution in virtual communities: accounting for multiple dimensions of social presence through social identity. Behaviour and Information Technology 2010; 29:337–348 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leach CW, Van Zomeren M, Zebel S, et al. Group-level self-definition and self-investment: a hierarchical (multicomponent) model of in-group identification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2008; 95:144–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cameron JE. A three-factor model of social identity. Self and Identity 2004; 3:239–262 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Obst PL, White KM, Mavor KI, et al. (2011) Social identification dimensions as mediators of the effect of prototypicality on intergroup behaviours. Psychology 2011; 2:426–432 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beullens K, Schepers A. Display of alcohol use on Facebook: a content analysis. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 2013; 16:497–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang GC, Unger JB, Soto D, et al. Peer influences: the impact of online and offline friendship networks on adolescent smoking and alcohol use. Journal of Adolescent Health 2014; 54:508–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Litt DM, Stock ML. Adolescent alcohol-related risk cognitions: the roles of social norms and social networking sites. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 2011; 25:708–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stoddard SA, Bauermeister JA, Gordon-Messer D, et al. Permissive norms and young adults' alcohol and marijuana use: the role of online communities. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 2012; 73:968–975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Westgate EC, Neighbors C, Heppner H, et al. “I will take a shot for every ‘like’ I get on this status”: posting alcohol-related Facebook content is linked to drinking outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 2014; 75:390–398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Westgate EC, Holliday J. Identity, influence, and intervention: the roles of social media in alcohol use. Current Opinion in Psychology 2016; 9:27–32 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rimal RN, Real K. Understanding the influence of perceived norms on behaviors. Communication Theory 2003; 13:184–203 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Epstein JA. Adolescent computer use and alcohol use: what are the role of quantity and content of computer use? Addictive Behaviors 2011; 36:520–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fredricks JA, Eccles JS. Developmental benefits of extracurricular involvement: do peer characteristics mediate the link between activities and youth outcomes? Journal of Youth and Adolescence 2005; 34:507–520 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayes AF. (2013) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York: The Guilford Press [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atkin CK. Effects of televised alcohol messages on teenage drinking patterns. Journal of Adolescent Health Care 1990; 11:10–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones SC, Magee CA. Exposure to alcohol advertising and alcohol consumption among Australian adolescents. Alcohol and Alcoholism 2011; 46:630–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith LA, Foxcroft DR. The effect of alcohol advertising, marketing and portrayal on drinking behaviour in young people: systematic review of prospective cohort studies. BMC Public Health 2009; 9:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pennay A, Lubman D, Frei MY. Alcohol: prevention, policy and primary care responses. Australian Family Physician 2014; 43:356–361 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]