Abstract

Purpose: Transgender individuals are medically underserved in the United States and face many documented disparities in care due to providers' lack of education, training, and comfort. We have previously demonstrated that specific transgender medicine content in a medical school curriculum increases students' willingness to treat transgender patients. However, we have also identified that those same students are less comfortable with transgender care relative to care for lesbian, gay, and bisexual patients. We aimed to demonstrate that clinical exposure to care for transgender patients would help close this gap.

Methods: At Boston University School of Medicine, we piloted a transgender medicine elective where students rotate on services that provide clinical care for transgender individuals. Pre- and postsurveys were administered to students who participated in the elective.

Results: After completing the elective, students who reported “high” comfort increased from 45% (9/20) to 80% (16/20) (p=0.04), and students who reported “high” knowledge regarding management of transgender patients increased from 0% (0/20) to 85% (17/20) (p<0.001).

Conclusion: Although integrating evidence-based, transgender-specific content into medical curricula improves student knowledge and comfort with transgender medical care, gaps remain. Clinical exposure to transgender medicine during clinical years can contribute to closing that gap and improving access to care for transgender individuals.

Keywords: : transgender health, transgender medical education, transgender medicine, transgender clinical care

Introduction

In the United States, transgender people make up an estimated 0.5–0.6% of the population.1–3 Transgender individuals have unique health needs; however, a majority of the members in the medical community are not adequately trained to address those needs.4–11 Barriers accessing appropriate and culturally competent care play a significant role in the persistent health disparities experienced by transgender individuals, such as increased rates of certain cancers, substance abuse, mental health concerns, infections, and chronic diseases.10–17 There is a need for healthcare providers to be comfortable treating transgender patients, as well as being versed in the health needs of transgender patients. Physicians and medical students report having knowledge gaps in transgender healthcare due to insufficient education and exposure.18–23

In recent years, public awareness in the press regarding the health disparities within the transgender population has been increasing. There has been a call to arms by the Institute of Medicine for further research on healthcare inequities among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) patients by specifically addressing the shortage of LGBT medicine training.10 A study by White et al. found that among 176 allopathic and osteopathic medical schools, a median of 5 h was dedicated to teaching content related to LGBT health and 33% of medical schools reported 0 h of LGBT-related content being taught during clinical years. In addition, fewer than 35% provided content related to hormone therapy and gender-confirming surgery.18

The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) suggested specific curricular content for LGBT patients in general and transgender patients specifically.24 Over the past decade, individual medical schools have made efforts to improve their LGBT health curricula in efforts to meet the AAMC recommendation.

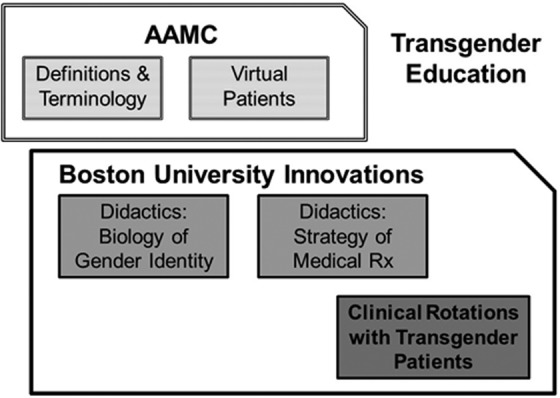

At Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM), we supplemented the AAMC approach with evidence-based, transgender-specific medical education that we have longitudinally integrated throughout the medical curriculum (Fig. 1). Beyond the AAMC suggested program, first-year BUSM students in physiology learn about the biologic evidence for gender identity.25 In the following year, BUSM students are taught both the classic treatment regimens and monitoring requirements for transgender hormone therapy as part of the standard endocrinology curriculum.26 Following the first 2 years, students reported a significant increase in willingness to care for transgender patients and a 67% decrease in discomfort with providing care to transgender patients.

FIG. 1.

The Boston University model for teaching transgender medical care. Boston University's transgender education framework follows AAMC recommendations and further supplements them with own innovations. First- and second-year medical students are taught about the biologic evidence for gender identity and the treatment strategies for transgender hormone therapy, respectively. Fourth-year students are offered clinical exposure through the transgender medicine elective. AAMC, Association of American Medical Colleges.

Despite our program, we found that at BUSM, our students reported comfort with transgender medical care still lags behind that for lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) patients.19 We speculated that the disparity related to direct personal exposure being greater for LGB patients at our institution than it is for transgender patients.

Other medical programs have reported that medical trainees with greater clinical exposure to transgender patients reported more comfort and greater knowledge than students with no clinical exposure.27–29 In this study, we hypothesized that in addition to integrating evidence-based, transgender-specific content into the medical curriculum, clinical exposure through the transgender medicine elective would significantly improve medical students' attitudes and level of overall preparedness in providing care for transgender patients.

Methods

Curriculum content

At BUSM, in addition to general LGBT coursework, biology of gender identity and transgender hormone treatment management are integrated into the mandatory first and second-year curriculum frameworks, respectively. The biology of gender identity content is included within the normal first-year physiology course. The evidence for the biological underpinnings of gender identity is reviewed with key data, including (1) the experience of intersex individuals in whom attempts to manipulate gender identity were made, (2) the increased incidence of being transgender among identical twins of transgender individuals, (3) the data for androgen impact on gender identity, and (4) the brain anatomy data that correlate with gender identity rather than other biological features. The transgender hormone management content is included during teaching of reproductive hormones in the Endocrinology section in the second year. In 2014, BUSM expanded its transgender programming further to include an experiential component with a clinical elective for fourth-year medical students. The transgender medicine elective included direct patient care experiences with transgender individuals in adult primary care, pediatrics, endocrinology, and surgery.

Study design

Over the 3-year period between January 1, 2014, and December 31, 2016, pre- and postsurveys were administered to each of the medical students who participated in the elective. The pre- and postsurveys were identical and asked students to report their self-perceived level of comfort and readiness to care for transgender patients. The presurvey was administered before beginning the rotation, and the postsurvey was administered immediately after the conclusion of the elective.

Students were asked to assess their own knowledge, skills, and comfort caring for transgender patients using a 7-point Likert scale from 0 (Very Low) to 6 (Very High) (Table 1). Responses of “0” and “1” were grouped as “Low”; “2,” “3,” and “4” were grouped as “Moderate”; and “5” and “6” were grouped as “High.” The survey also prompted the students to answer questions regarding their attitudes toward transgender care and transgender education by responding “Strongly Disagree,” “Disagree,” “Neither Agree nor Disagree,” “Agree,” or “Strongly Agree” (Table 2). For the analysis, “Strongly Disagree” and “Disagree” responses were grouped as “Disagree”; “Neither Agree nor Disagree” was labeled as “Neutral”; and “Agree” and “Strongly Agree” were grouped as “Agree.”

Table 1.

The Following Questions Were Used to Assess the Students' Knowledge, Skill, and Comfort When Caring for Transgender Patients. Students Responded Using a 7-Point Likert Scale from 0 (Very Low) to 6 (Very High)

| Knowledge level |

| What is your level of knowledge regarding the management of transgender persons? |

| What is your level of knowledge of guidelines regarding the management of transgender persons? |

| Skill level |

| How would you assess your level of skill in inquiring about a patient's gender identity? |

| How would you assess your level of skill in providing general care for transgender patients? |

| How would you assess your level of skill in providing hormone for transgender patients? |

| Comfort level |

| What is your level of comfort with providing care to a transgender patient? |

Table 2.

The Following Questions Were Used to Assess the Students' Attitude Toward Transgender Care. Students Responded with “Strongly Disagree,” “Disagree,” “Neither Agree nor Disagree,' “Agree,” or “Strongly Agree”

| Attitude |

| I think it is important to ask all patients about their gender identity |

| I think it is important to conduct health screenings for gender minorities according to their sex at birth |

| I am interested in learning more about medical interventions for transgender patients |

| Medications for transgender patients should be covered by medical insurance |

| Surgery for transgender patients should be covered by medical insurance |

| Psychotherapy for transgender patients should be covered by medical insurance |

| Prescribing cross-gender hormones will result in unacceptable side effects |

| Withholding cross-gender hormones will result in unacceptable consequences |

| Patients who have sex reassignment surgery will have regrets later |

| Patients who have sex reassignment surgery will have better well-being |

Responses were all collected using a paper survey and the study was approved by the Boston University Institutional Review Board.

Statistical analyses

A chi-square test for independence was used to compare the relative frequencies of the pre- and postsurvey responses. All statistical analyses were conducted with SAS software packaged version 9.3.30

Results

Students entered the elective with broadly positive attitudes toward transgender care

All 20 students (100%) completed the pre- and postelective surveys. Students began the elective with a high degree of support for transgender care. All the students were interested in learning more about medical interventions for transgender patients. Owing to a high baseline, there was no significant change in students' attitudes toward transgender care and transgender education after completing the fourth-year elective.

Before the survey, 79% (15/19) of students agreed that it was important to ask all patients about their gender identity. Ninety-five percent (18/19) agreed that it was important to conduct health screenings for gender minorities according to organs and tissues present. Every student agreed that medications, surgery, and mental health support for transgender patients should be covered by medical insurance. Seventeen students (85%) felt that patients who have genital reconstruction surgery would not have regrets later in life and would have better well-being. In addition, no student believed that prescribing transgender hormones would result in unacceptable consequences, but 16 out of 20 students did believe withholding transgender hormones would result in unacceptable consequences.

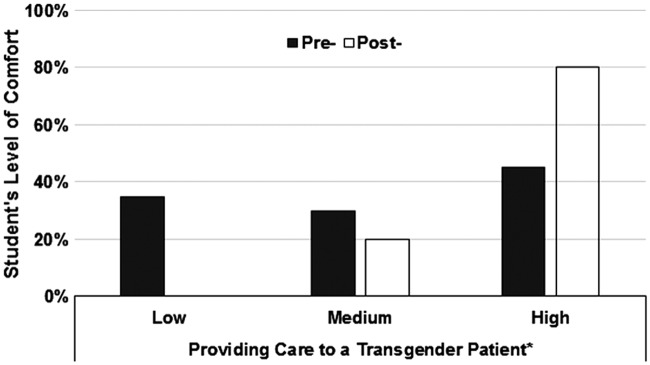

Comfort with transgender care rose significantly

When asked about comfort before the elective, some students reported comfort with providing medical care to transgender individuals (Fig. 2). However, after the elective, those who reported “high” level of comfort providing care for transgender patients increased from 45% (9/20) to 80% (16/20) (p=0.04). Students unanimously reported that they believed that to make high-quality gender minority care a reality, medical schools and residency programs must provide training in transgender health.

FIG. 2.

Percentage of fourth-year students self-assessing their comfort level caring for transgender patients. p-Values were obtained using chi-square test for independence. *p<0.05.

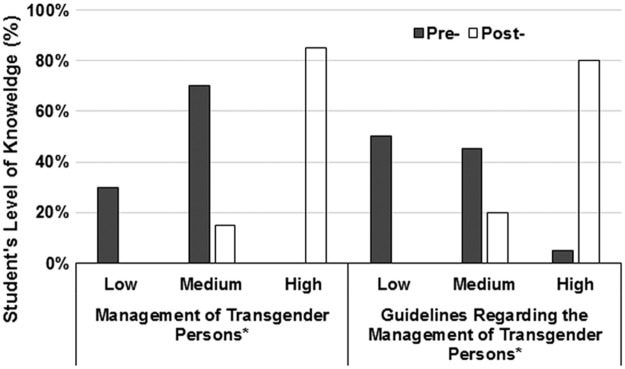

Clinical exposure resulted in a significant increase in self-reported knowledge of transgender care

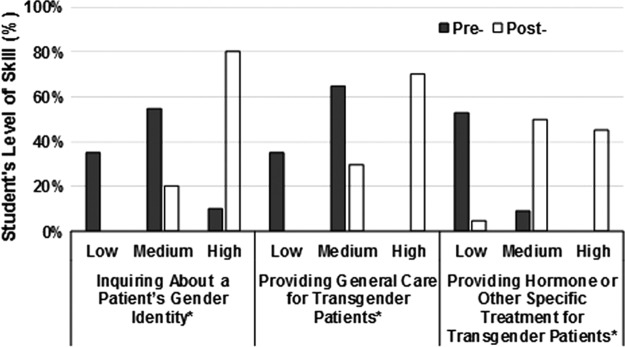

Before the elective, despite some comfort with transgender medical knowledge and strongly positive attitudes, students reported limited knowledge. Students reported a substantial increase in their knowledge of transgender medical care after clinical exposure to transgender patients (Fig. 3). After completing the elective, the number of students who reported having “high” knowledge for the management of transgender persons increased from 0% (0/20) to 85% (17/20) (p<0.001). Students also reported an increase in having “high” knowledge for management guidelines of transgender persons from 5% (1/20) to 80% (16/20) (p<0.001). There was a considerable increase in student's self-reported skills caring for transgender patients (Fig. 4). Only 10% of fourth-year students (2/20) entering the elective reported they had “high” skills inquiring about a patient's gender identity compared with 80% (16/20) after completing the elective (p<0.001). In addition, seven students (35%) reported that they had “low” skills providing general care for transgender patients before the elective, whereas no student (0/20) felt this way after the elective (p<0.001). Before the elective, more than half of the students (10/19) reported having “low” skills providing hormone treatment for transgender patients, while only one student (5%) reported that skills remained “low” after participating in the elective (p<0.001).

FIG. 3.

Percentage of fourth-year students self-assessing their knowledge of transgender care management. p-Values were obtained using chi-square test for independence. *p<0.05.

FIG. 4.

Percentage of fourth-year students self-assessing their skill level of transgender care. p-Values were obtained using chi-square test for independence. *p<0.05.

Discussion

This is the first study to demonstrate that clinical exposure to transgender patients can improve medical students' level of comfort, confidence, skill, and knowledge to deliver culturally competent care to transgender patients above a baseline achieved by other modalities.

While the BUSM evidence-based approach to teaching transgender medicine improved attitudes among medical students above the baseline achieved with AAMC modeled content alone,25,26 a gap remained in student comfort relative to LGB patients.19 We propose that the remaining gap might be addressed at least, in part, with an experiential program that includes direct medical care of transgender individuals (Fig. 1).

There were no significant changes in attitudes toward transgender care and transgender education after completing the fourth-year elective. That finding appeared to reflect the high bar among students who entered the elective already exhibiting an overwhelming willingness to care for transgender patients and recognition of the appropriateness of transgender hormone therapy. We attribute the high starting point to the existing transgender-specific content in the mandatory first- and second-year curriculum.

However, despite the positive attitudes toward transgender individuals, a majority of fourth-year medical students did not feel comfortable caring for transgender patients before beginning the elective. This suggests that classroom lectures are not enough to adequately prepare students to manage the care of transgender patients as future physicians. Even among students with strongly positive attitudes toward transgender medicine, comfort with needed clinical skills was low. By providing students experiential opportunities such as in the case for other medical topics, the fourth-year elective provides a novel approach to close gaps in transgender medical education.

One of the limitations to the study was that it was conducted at a single institution. Therefore, the results of our findings may not be generalizable to other medical schools. There is also likely selection bias because students who participated may have been more inclined to work with transgender patients as the clinical rotation was not mandatory. An opportunity to mandate transgender clinical exposure may be superior. Still, the identification of a remediable gap in skills even among a positively biased cohort is an important finding.

Due to the fact that these are self-reported data, there is potential for response bias because students may believe they should be more prepared than they are in their abilities to care for transgender patients after completing a transgender elective. Furthermore, although there was 100% response rate, the study was further limited by the small number of students due to the limited capacity of the elective.

Future research assessing medical students' comfort and knowledge regarding transgender care can be improved by including students who did not take the transgender elective as controls. This would not only increase the sample size of the study but also produce results that are more robust. In addition, future surveys should include questions inquiring about which specialty students are planning to pursue. This would help elucidate potential areas of medicine attracting students who are more or less prepared to work with transgender patients. Finally, future studies should test whether the medical education intervention could have similar results among different medical schools.

Conclusion

We propose that the existing Boston University model, which supplements what has been termed “cultural competency” by some with evidence-based curricular content on (1) the biology of gender identity and (2) current strategies for transgender hormone therapy, is necessary but not sufficient for optimal training for care of transgender patients. We propose a need for a third component to our model in the form of experiential activities such as those that exist for other medical topics, with increased clinical exposure to transgender patients.

Abbreviations Used

- AAMC

Association of American Medical Colleges

- BUSM

Boston University School of Medicine

- LGB

lesbian, gay, and bisexual

- LGBT

lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Conron KJ, Scott G, Stowell GS, et al. Transgender health in Massachusetts: results from a household probability sample of adults. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:118–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flores AR, Herman JL, Gates GJ, et al. How Many Adults Identify as Transgender in the United States? Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crissman HP, Berger MB, Graham LF, et al. Transgender demographics: a household probability sample of US adults. Am J Public Health. 2017;107:213–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Safer JD, Tangpricha V. Out of the Shadows: it is time to mainstream treatment for transgender patients. Endocr Pract. 2008;14:248–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Safer JD, Coleman E, Feldman J, et al. Barriers to healthcare for transgender individuals. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23:168–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makadon HJ. Improving health care for the lesbian and gay communities. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:895–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayer KH, Bradford JB, Makadon HJ, et al. Sexual and gender minority health: what we know and what needs to be done. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:989–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irwig MS. Transgender care by endocrinologists in the United States. Endocr Pract. 2016;22:832–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obedin-Maliver J, Goldsmith ES, Stewart L, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-related content in undergraduate medical education. JAMA. 2011;306:971–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.IOM (Institute of Medicine). The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011. Available at: www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=13128 Accessed August1, 2017 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant JM, Tanis J, Herman JL, et al. National Transgender Discrimination Survey Report on Health and Health Care. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dean L, Meyer IH, Robinson K, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health: findings and concerns. J Gay Lesbian Med Assoc. 2000;4:102–151 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gay and Lesbian Medical Association and LGBT Health Experts. Healthy People 2010 Companion Document for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Health. San Francisco, CA: Gay and Lesbian Medical Association, 2001. Available at: www.glma.org/_data/n_0001/resources/live/HealthyCompanionDoc3.pdf Accessed August19, 2014

- 14.Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities; Board on the Health of Select Populations; Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, 2011. Available at: www.iom.edu/Reports/2011/The-Health-of-Lesbian-Gay-Bisexual-and-Transgender-People.aspx Accessed August1, 2017

- 15.Smith DM, Mathews WC. Physicians' attitudes toward homosexuality and HIV: survey of a California Medical Society-revisited (PATHH-II). J Homosex. 2007;52:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kosenko K, Rintamaki L, Raney S, et al. Transgender patient perceptions of stigma in health care contexts. Med Care. 2013;51:819–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stroumsa D. The state of transgender health care: policy, law, and medical frameworks. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:31–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White W, Brenman S, Paradis E, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patient care: medical students' preparedness and comfort. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27:254–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang JJ, Gardner IH, Walker JA, et al. Observed deficiencies in medical student knowledge of transgender and intersex health. Endocr Pract. 2017;23:897–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khalili J, Leung LB, Diamant AL. Finding the perfect doctor: identifying lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-competent physicians. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:1114–1119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sequeira GM, Chakraborti C, Panunti BA. Integrating lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) content into undergraduate medical school curricula: a qualitative study. Ochsner J. 2012;12:379–382 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan B, Skocylas R, Safer JD. Gaps in transgender medicine content identified among Canadian medical school curricula. Transgend Health. 2016;1:142–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rondahl G. Students' inadequate knowledge about lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender persons. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2009;6:Article 11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Association of American Medical Colleges. Joint AAMC-GSA and AAMC-OSR Recommendations Regarding Institutional Programs and Educational Activities to Address the Needs of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender (GLBT) Students and Patients. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eriksson SE, Safer JD. Evidence-based curricular content improves student knowledge and changes attitudes towards transgender medicine. Endocr Pract. 2016;22:837–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Safer JD, Pearce EN. A simple curriculum content change increased medical student comfort with transgender medicine. Endocr Pract. 2013;19:633–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dy GW, Osbun NC, Morrison SD, et al. Exposure to and attitudes regarding transgender education among urology residents. J Sex Med. 2016;13:1466–1472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davidge-Pitts C, Nippoldt TB, Danoff A, et al. Transgender Health in Endocrinology: Current Status of Endocrinology Fellowship Programs and Practicing Clinicians. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:1286–1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanchez NF, Rabatin J, Sanchez JP, et al. Medical students' ability to care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered patients. Fam Med. 2006;38:21–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.SAS Institute Inc. The SAS System for Windows: Version 9.3. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc, 2011 [Google Scholar]

References

Cite this article as: Park JA, Safer JD (2018) Clinical exposure to transgender medicine improves students' preparedness above levels seen with didactic teaching alone: a key addition to the Boston University Model for teaching transgender healthcare, Transgender Health 3:1, 10–16, DOI: 10.1089/trgh.2017.0047.