Abstract

Apolipoprotein E4 (ApoE4) is a major genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The E4 allele of ApoE plays a crucial role in the inflammatory and neurodegenerative processes associated with AD. This is evident from the multiple effects of the ApoE isoforms in beta amyloid (Aβ) aggregation. Glia maturation factor (GMF) is a brain-specific neuroinflammatory protein, that we have previously demonstrated to be significantly upregulated in various regions of AD brains compared to non-AD control brains and that it induces neurodegeneration. We have previously reported that GMF is predominantly expressed in the reactive astrocytes surrounding APs in AD brain. In the present study, using immunohistochemical staining methods we show the expression of GMF and ApoE4 in AD brains. Double immunofluorescence labelling of GMF and ApoE4 showed their co-localization in the amyloid plaques (APs) of AD brain. We show the co-localization of GMF and ApoE4 in APs of AD brain by double immunohistochemical and dual immunofluorescence methods. Our results show that ApoE4 is present in APs of AD brain. Double immunofluorescence labelling method shows the relationship between ApoE4 and GMF expression in the APs in the AD brain. We found that GMF and ApoE4 were strongly expressed and co-associated in APs and in the reactive astrocytes surrounding APs in AD. The increased expression of GMF in APs and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) in the AD brain, and the co-localization of GMF and ApoE4 in APs suggest that GMF and ApoE4 together should be contributing to the pathogenesis of AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, Amyloid plaques, Neurofibrillary tangles, Apolipoprotein E4, Neuroinflammation

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder affecting 5 million Americans and about 35 million individuals worldwide. It is the most common cause of dementia among older people and is characterized by amyloid plaques (APs) or neuritic plaques (NPs) containing aggregates of beta-amyloid (Aβ) peptide and, neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) leading to neuroinflammation and degenerating neurons. The deposition of APs and the formation of NFTs are the histopathological hallmarks of AD. Among the affected regions, hippocampus (HC) and entorhinal cortex (EC) are the major brain areas that show neuropathological lesions of AD [1, 2]. Both HC and EC have direct connectivity, being very important for memory associated functions and which are also the most vulnerable during the early progression of AD pathology [2]. The number of NFT’s especially in these two brain areas is well correlated with the cognitive memory impairment in AD patients [3, 4].

Although the main cause of neuronal death in AD is commonly attributed to the APs and the NFTs, it has become clear that other biological response modifiers including the local chronic inflammatory responses mediated by the glial cells (microglia and astrocytes) contribute to the severity of the pathologic process. Activated glia is known to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and other toxic substances capable of causing neuronal death. Glia maturation factor (GMF) is an inflammatory protein playing a major role in the pathogenesis of central nervous system (CNS) inflammation and neurodegenerative diseases. The presence of GMF in activated glia in close vicinity of APs and NFTs support the hypothesis that overexpression of GMF is closely involved in the pathogenesis of AD [5]. Further, it has been shown that GMF induces interleukin-33 (IL-33) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) in mouse astrocytes which are major proinflammatory cytokines that induces neurodegeneration and neuronal death [6]. GMF has been co-localized along with APs and NFTs in EC and HC of AD. The EC and HC are the most vulnerable and heavily affected brain regions in AD [2, 7].

Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) is a polymorphic protein that plays a key role in the lipid and cholesterol transport and lipoprotein metabolism in the CNS and peripheral nervous system [8, 9]. This protein is produced differentially in the CNS (by astrocyte and microglia) and peripherally (by liver and macrophages) and it does not cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) [10]. It is a 299-amino acid protein with a molecular mass of ~34 kDa encoded by the ApoE gene. This gene has three major polymorphic alleles: ε2, ε3 and ε4, with a worldwide frequency of about 8, 78 and 14 %, respectively [8, 11]. ApoE remains the strongest and most common genetic risk factor for both familial and sporadic onset AD with 60–80% of AD cases having at least one ApoE4 allele [12–14]. ApoE4 has been described both immunohistochemically and biochemically as a constituent of deposits, along with many other amyloid-associated proteins. In this study we report the association of GMF and ApoE4 expression in AD brains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human brain samples

Human postmortem AD and age matched non-AD brain were obtained through the University of Iowa Deeded body program. The temporal lobe sections were cut on a sledge freezing microtome. Sections were stored in cryoprotectant solution until the start of the immunostaining protocol. This study was approved by the University of Missouri Institutional Review Board (IRB #2008067; Exempt Application 224561), Columbia, MO, USA. This study was conducted under standard ethical procedures. All the appropriate personal protection safety procedures were followed to handle the human samples.

Immunohistochemistry and thioflavin-S staining

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed according to our published methods [15, 16]. We used free-floating sections from the temporal cortex of AD and non-AD brains. Sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4C. We performed antigen retrieval with citrate buffer (10mM citric acid in dH2O) treatment as described previously. The sections were blocked with 5% normal goat serum and 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) with 0.1% Triton-X 100 in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 1h at room temperature. Sequential incubation with the primary antibodies anti-ApoE4 mouse monoclonal (1:2000 dilution, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) and anti-GMF polyclonal (1:100 dilution, ABCAM) was performed overnight at 4°C. After washing with PBS three times, sections were sequentially incubated with Impress HRP anti-Mouse IgG (Peroxidase) and Impress™ HRP Anti-Rabbit IgG (Peroxidase) Polymer Detection Kits (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). In the first sequence of double labelling, we used the ImmPACT SG Peroxidase (HRP) substrate with the anti-GMF stained cells to reveal the blue-gray colour. In the second sequence of immunohistochemical labelling, Impact DAB Peroxidase (HRP) substrate was used which stained cells in brown colour that were immunopositive with the ApoE4 antibody. For thioflavin-S staining, ApoE4 immunostained sections were incubated in the 1% aqueous thioflavin-S solution for 10 min at room temperature. Then the sections were washed with 80% ethanol, rinsed with distilled water, and air-dried and finally a cover slip was placed. Both bright field and fluorescent microscopic images were used to show the colocalization of ApoE4 with thioflavin-S stained APs. Digital images were captured at 20× magnification using Nikon microscope equipped with a camera (Nikon DIAPHOT microscope, Garden City, NY). The number of thioflavin-S positive APs were counted by using Metamorph Image analysis software (Meta Imaging Series 7.8, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). We analyzed an average of three digital images per section to detect and quantify the average intensity of areas.

Double immunofluorescence

Double immunofluorescence labelling was performed using the monoclonal anti-ApoE4 (ABCAM) in combination with polyclonal anti-GMF (ABCAM) and anti-rabbit GFAP (ABCAM). Following overnight incubation with primary antibodies, a cocktail of Alexa 488 labelled goat anti-mouse IgG and Alexa 568 labelled goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies were used for double immunofluorescence labelling. After washing with PBS, the sections were mounted on to the slides and viewed with Nikon fluorescence microscope.

Staining intensity and Area quantification

We used the integrated morphology analysis MetaMorph software to quantify the average intensity and area of GMF, ApoE4 and GFAP antibodies immunoreactivity as previously reported [17]. Measurements were conducted on three fields from three representative sections in each case.

Statistical Analysis

We performed statistical analysis by using independent student t test in the GraphPad InStat software. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. The p <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

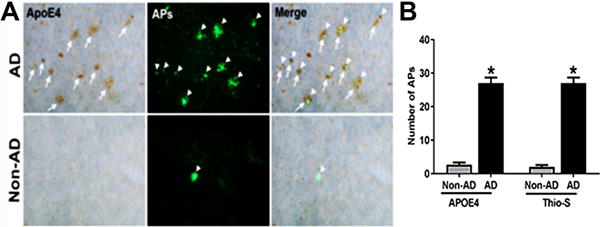

Expression of ApoE4 and APs in human AD and non-AD brain

As there is a strong correlation between ApoE4 and AD pathophysiology, we wanted to address the question whether or not differential ApoE4 expression is observed between the AD and non-AD brains in relation to the APs. Our immunohistochemical study showed ApoE4 immunoreactivity mainly in APs. To show the expression of ApoE4 in APs, AD and non-AD brain sections were immunostained with ApoE4 antibody then counterstained with thioflavin-S. Histochemical analysis showed that most of the thioflavin-S stained APs (green color, arrowheads) contained strong ApoE4 (brown color, arrows) immunoreactivity (Fig. 1A). Relative counts of ApoE4 positive and thioflavin-S stained APs are shown in Fig.1B. Our immunostaining data indicates high levels of ApoE4 expression specifically in AD brains. Non-AD brain sections revealed negligible ApoE4 staining despite presence of a few APs.

Fig. 1.

ApoE4 expression is enhanced in AD brain and localizes with APs. (A) Co-localization of ApoE4 positive (brown color, white arrows) and thioflavin-S (green color arrowheads) revealed APs in temporal cortex of AD and non-AD brains. Merged image shows most of the APs extensively immunoreactive to ApoE4 are co-localized with thioflavin-S labeled APs. Magnification: 200x. (B) The data were expressed as mean ± SEM. P <0.05 versus non-AD was considered statistically significant.

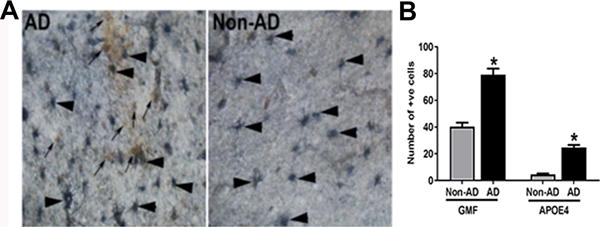

Co-expression of ApoE4 and GMF in human AD and non-AD brain

Having established the localization of ApoE4 to APs in AD brain, we next explored the expression of the neuroinflammatory protein, GMF in relation to ApoE4 and APs. To understand this relationship, brain sections were subjected to double immunofluorescence staining for ApoE4 deposits and GMF expression. Our results clearly showed abundant ApoE4 deposits as well as strong GMF expression in the APs (Fig. 2A). Relative quantification of GMF and ApoE4 stained cells is shown in Fig.2B.

Fig. 2.

Dual immunohistochemical staining reveals enhanced expression of GMF and ApoE4 in AD brain. (A) Double immunohistocehmical analysis of GMF (SG vector, blue/gray color, arrowheads) and ApoE4 stained APs (DAB, brown color, arrows) in temporal cortex of AD and non-AD brain. Magnification 200×. (B) Quantification of number of GMF and ApoE4 positive cells. The data were expressed as mean ± SEM and P <0.05 versus non-AD was considered statistically significant.

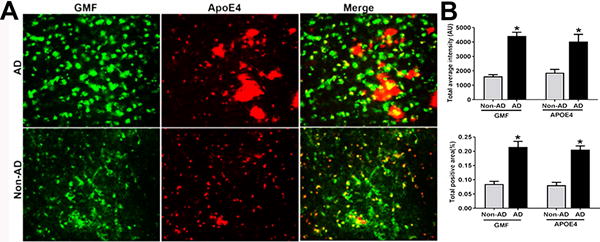

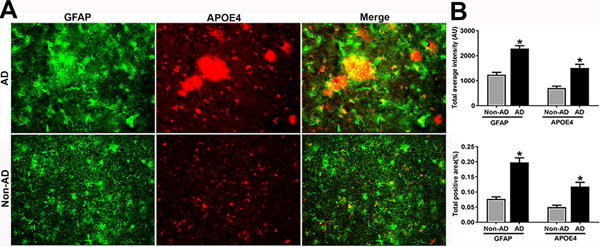

To examine the spatiotemporal relationship between GMF expression relative to the deposits of ApoE4 in APs in the temporal cortex of AD and non-AD brain sections; we performed double immunofluorescence staining for GMF (green color) and ApoE4 (red color) (Fig.3A). Quantification analysis showed the total staining intensity and positive stained area (Fig.3B). These results show that GMF immunoreactivity is associated with APs and activated astrocytes surrounding the APs. In addition, ApoE4 expression is associated with APs in AD brain.

Fig. 3.

Co-localization of GMF and ApoE4 in the temporal cortex of human AD brain. (A) Co-localization of GMF (green color) and ApoE4 (red color) in the temporal cortex of AD and non-AD human brain. Sections were stained with anti-GMF and anti-ApoE4 antibody respectively to check the co-localization of GMF with ApoE4 in the temporal cortex of human AD brain. Magnification 200×. (B) Quantification based on average staining intensity and positive area. The data were analysed as mean ± SEM and P <0.05 versus non-AD was considered statistically significant.

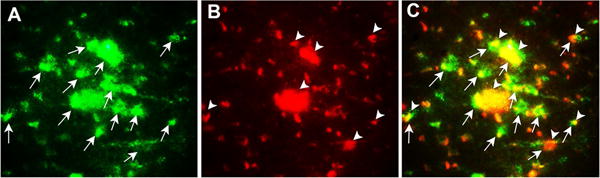

Immunofluorescence photomicrographs shows in more detail (Fig.4) the co-localization of GMF (green color, arrows) and ApoE4 (red color, arrows) contained within APs in AD brain. Also, it shows that the ApoE4 positive APs is observed near clusters of reactive astrocytes surrounding the ApoE4 stained APs.

Fig. 4.

Co-localization of GMF (A, green color) and ApoE4 (B, red color) and merged image (C, yellow color) indicates overlap of green and red in temporal cortex of AD brain. In addition, it shows that the ApoE4 positive APs was observed near clusters of reactive astrocytes. Magnification 200×.

ApoE4 stimulates and co-localizes with astroglial GFAP in human AD and non-AD brain

To understand this relationship between astrogliosis and ApoE4 in human AD and non-AD brains, sections were processed for double immunofluorescence staining to show the co-localization of ApoE4 and the astrocytic marker, GFAP in AD and non-AD brain as shown in Fig.5A. ApoE4 immunostained APs (red color) were associated with clustered and strongly stained GFAP-positive astrocytes (green color). This finding clearly indicates that ApoE4 is increased in regions of glial activation in AD brain (Fig.5A). Most of the ApoE4 immunostained APs and cluster of astrocytes surrounding the APs were also strongly immunoreactive for GMF as shown in Fig.4. Quantification analysis showed the total staining intensity and positive staining area of GFAP and ApoE4 (Fig.5B)

Fig. 5.

ApoE4 and GMF are localized to regions of reactive astrocytes in temporal cortex of human AD brain. (A) Co-localization of GFAP (green) and ApoE4 (red) in human AD and non-AD brain. Representative immunofluorescence staining showed the co-localization of GFAP with ApoE4. Magnification 200×. (B) Quantification based on average staining intensity and positive area. The data were analysed as mean ± SEM and p <0.05 versus non-AD was considered statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Apolipoprotein plays an important role in brain homeostasis because of its lipid transport function and effect on energy metabolism. Perusal of literature suggests a strong linkage between late onset form of AD and ApoE4. The importance of ApoE4 as a causative factor in cognitive decline and dementia associated with AD has been documented [18]. It has been shown that ApoE plays a central role in the brain’s response to injury and neurodegeneration in AD brain. In the CNS, ApoE plays a very important role especially in mobilization and redistribution of phospholipid and cholesterol during membrane remodelling associated with synaptic plasticity. Neuronal cell losses in various areas of brain including substantia nigra, locus cereleus, amygdale and the nucleus of Meynert are almost never compensated in humans carrying one or two copies of the e4 allele while subjects with AD without the ApoE4 allele show marked regenerative capacity. Altogether, these results suggest that the usual compensatory growth of nerve fibres appear to be affected somewhat in the ApoE4/AD population. ApoE levels may vary according to the extent a given brain region is affected by ongoing AD-related degeneration. The capacity to repair decreases as neuronal loss progresses in the course of disease [19]. As demonstrated in previous studies [20, 21], ApoE/amyloid complex triggers a cascade of molecular events that could lead to the formation of senile plaques. It has also been reported that purified ApoE4 has a higher affinity for soluble beta amyloid than ApoE3 and ApoE2 isoforms. A recent study [22] showed that ApoE secreted by glia stimulates neuronal Aβ production with the potency of ApoE4 greater than that of Apo E3 and Apo E2.

Furthermore, density of β-A4 was shown to correlate positively with the ApoE4 dose of the immunopositive plaques and NFTs in the cortex and hippocampus of AD patients [21, 23]. The combination of this biochemical, pathological and genetic evidence suggests that there is an intricate relationship between cholesterol homeostasis, ApoE metabolism and amyloid plaque formation and secretion.

In this study, we report that ApoE4 is localized in the vicinity of APs and is associated with glial cells that are thought to play key roles in plaque development during AD pathogenesis. We report that ApoE4 and GMF were significantly increased in the AD brains when compared to non-AD brains. Further, we also have detected ApoE4 in the lesions indicating their expression in the glial cells. GMF is an intracellular inflammatory signal transduction regulator involved in neuroinflammation and subsequent neurodegeneration. As the amino acid sequence of GMF is highly conserved, it plays basic roles across many species. GMF concentration is higher specifically at the sites of APs and hyperphosphorylated Tau containing NFTs, the two pathological hallmarks of AD[24]. It is also demonstrated that GMF could be phosphorylated by protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase C (PKC); and the phosphorylated form is an inhibitor of the extra cellular signal regulated kinase (ERK) isoform of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) [25] and at the same time a stimulator of the p38 isoform; implicating that GMF is involved in stress-activated inflammatory responses[26]. A recent study [22] described a novel signal transduction pathway in neurons in which MAPK cascade was activated by ApoE leading to enhanced Aβ synthesis. Research has also shown that GMF leads to activation of nuclear transcription factor kappa-B (NF-kB), followed by increased production of inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β and IL-33 [6]. Recently, it is also seen that overexpression of GMF is necessary for the induction of granulocyte-macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) in astrocytes. GM-CSF is one of the key molecules for GMF-dependent production of inflammatory cytokines in microglial cells which enhances the expression of several pro inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, thus playing an important role in the amplification of immune and inflammatory processes [27]. A study clearly demonstrated that the levels of GM-CSF were significantly increased in patients with AD[28]. Factors triggering excessive synthesis and secretion of GMF in the CNS are not yet clearly understood. However, increased number of APs, NFTs, inflammatory cells and inflammatory molecules may induce the up-regulation of GMF expression and GMF may act in an autocrine/or paracrine manner in the CNS of AD patients. High GMF expression by the glial cells may augment or synergize with other inflammatory molecules of the CNS and exacerbate the pathogenesis in AD. Besides GMF, other inflammatory molecules released by glial cells may also significantly contribute to the pathogenesis of AD [29–31].

From previous studies, it is known that astrocytes and microglia may be increased and or activated as an immune response to the presence of APs and NFTs, and these reactions may initiate the critical inflammatory reaction cascades of events in the early stages of AD [24, 32]. This is the first report that shows expression of GMF and ApoE4 is significantly increased in the cerebral cortex of AD brain where GMF is mainly localized in astrocytes and ApoE4 is associated with APs and NFTs. The distribution of GMF-immunoreactive cells in and around the thioflavin-S stained APs and NFTs suggests involvement of GMF in inflammatory responses through reactive glial cells in AD brain and a role for GMF in pathogenesis of AD. Thus, the role of GMF in AD pathogenesis may be to augment the neurotoxicity of ApoE4 and Aβ in potentiating neuronal degeneration.

Conclusion

The increased expression of GMF in APs and NFT in the AD brain, and the co-localization of GMF and ApoE4 in thioflavin-S stained APs suggest that GMF and ApoE4 together may play important roles in the pathogenesis of AD. For the first time we are providing evidence regarding colocalization of GMF and ApoE4 in AD brain. We believe that our current study will enable us and others to understand and decipher the molecular mechanism underlying the association of GMF and ApoE4 to facilitate neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration and memory deficits in AD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AG048205, Veteran Affairs Merit Award I01BX002477 and NS073670 to AZ

References

- 1.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thangavel R, Kempuraj D, Stolmeier D, Anantharam P, Khan M, Zaheer A. Glia maturation factor expression in entorhinal cortex of Alzheimer’s disease brain. Neurochem Res. 2013;38:1777–1784. doi: 10.1007/s11064-013-1080-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson PT, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, Kryscio RJ, Jicha GA, Santacruz K, Smith CD, Patel E, Markesbery WR. Brains with medial temporal lobe neurofibrillary tangles but no neuritic amyloid plaques are a diagnostic dilemma but may have pathogenetic aspects distinct from Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:774–784. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181aacbe9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson PT, Dimayuga J, Wilfred BR. MicroRNA in Situ Hybridization in the Human Entorhinal and Transentorhinal Cortex. Front Hum Neurosci. 2010;4:7. doi: 10.3389/neuro.09.007.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaheer S, Thangavel R, Wu Y, Khan MM, Kempuraj D, Zaheer A. Enhanced expression of glia maturation factor correlates with glial activation in the brain of triple transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mice. Neurochem Res. 2013;38:218–225. doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0913-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kempuraj D, Khan MM, Thangavel R, Xiong Z, Yang E, Zaheer A. Glia maturation factor induces interleukin-33 release from astrocytes: implications for neurodegenerative diseases. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013;8:643–650. doi: 10.1007/s11481-013-9439-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stolmeier D, Thangavel R, Anantharam P, Khan MM, Kempuraj D, Zaheer A. Glia maturation factor expression in hippocampus of human Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Res. 2013;38:1580–1589. doi: 10.1007/s11064-013-1059-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez-Morillo E, Hansson O, Atagi Y, Bu G, Minthon L, Diamandis EP, Nielsen HM. Total apolipoprotein E levels and specific isoform composition in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma from Alzheimer’s disease patients and controls. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127:633–643. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1266-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Premkumar DR, Cohen DL, Hedera P, Friedland RP, Kalaria RN. Apolipoprotein E-epsilon4 alleles in cerebral amyloid angiopathy and cerebrovascular pathology associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:2083–2095. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu M, Kuhel DG, Shen L, Hui DY, Woods SC. Apolipoprotein E does not cross the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier, as revealed by an improved technique for sampling CSF from mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;303:R903–908. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00219.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glockner F, Meske V, Ohm TG. Genotype-related differences of hippocampal apolipoprotein E levels only in early stages of neuropathological changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 2002;114:1103–1114. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel D, George-Hyslop PH, Pericak-Vance MA, Joo SH, Rosi BL, Gusella JF, Crapper-MacLachlan DR, Alberts MJ, et al. Association of apolipoprotein E allele epsilon 4 with late-onset familial and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1993;43:1467–1472. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.8.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strittmatter WJ, Saunders AM, Schmechel D, Pericak-Vance M, Enghild J, Salvesen GS, Roses AD. Apolipoprotein E: high-avidity binding to beta-amyloid and increased frequency of type 4 allele in late-onset familial Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:1977–1981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arold S, Sullivan P, Bilousova T, Teng E, Miller CA, Poon WW, Vinters HV, Cornwell LB, Saing T, Cole GM, Gylys KH. Apolipoprotein E level and cholesterol are associated with reduced synaptic amyloid beta in Alzheimer’s disease and apoE TR mouse cortex. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:39–52. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0892-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thangavel R, Sahu SK, Van Hoesen GW, Zaheer A. Modular and laminar pathology of Brodmann’s area 37 in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 2008;152:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thangavel R, Sahu SK, Van Hoesen GW, Zaheer A. Loss of nonphosphorylated neurofilament immunoreactivity in temporal cortical areas in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 2009;160:427–433. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Purushothuman S, Johnstone DM, Nandasena C, Mitrofanis J, Stone J. Photobiomodulation with near infrared light mitigates Alzheimer’s disease-related pathology in cerebral cortex - evidence from two transgenic mouse models. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2014;6:2. doi: 10.1186/alzrt232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahley RW, Weisgraber KH, Huang Y. Apolipoprotein E4: a causative factor and therapeutic target in neuropathology, including Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5644–5651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600549103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arendt T, Schindler C, Bruckner MK, Eschrich K, Bigl V, Zedlick D, Marcova L. Plastic neuronal remodeling is impaired in patients with Alzheimer’s disease carrying apolipoprotein epsilon 4 allele. J Neurosci. 1997;17:516–529. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00516.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strittmatter WJ, Weisgraber KH, Huang DY, Dong LM, Salvesen GS, Pericak-Vance M, Schmechel D, Saunders AM, Goldgaber D, Roses AD. Binding of human apolipoprotein E to synthetic amyloid beta peptide: isoform-specific effects and implications for late-onset Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:8098–8102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wisniewski T, Golabek A, Matsubara E, Ghiso J, Frangione B. Apolipoprotein E: binding to soluble Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;192:359–365. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang YA, Zhou B, Wernig M, Sudhof TC. ApoE2, ApoE3, and ApoE4 Differentially Stimulate APP Transcription and Abeta Secretion. Cell. 2017;168:427–441 e421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rebeck GW, Reiter JS, Strickland DK, Hyman BT. Apolipoprotein E in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: allelic variation and receptor interactions. Neuron. 1993;11:575–580. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thangavel R, Stolmeier D, Yang X, Anantharam P, Zaheer A. Expression of glia maturation factor in neuropathological lesions of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2012;38:572–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2011.01232.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaheer A, Lim R. Protein kinase A (PKA)- and protein kinase C-phosphorylated glia maturation factor promotes the catalytic activity of PKA. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5183–5186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.5183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kempuraj D, Thangavel R, Natteru PA, Selvakumar GP, Saeed D, Zahoor H, Zaheer S, Iyer SS, Zaheer A. Neuroinflammation Induces Neurodegeneration. J Neurol Neurosurg Spine. 2016;1 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaheer A, Mathur SN, Lim R. Overexpression of glia maturation factor in astrocytes leads to immune activation of microglia through secretion of granulocyte-macrophage-colony stimulating factor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;294:238–244. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00467-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tarkowski E, Wallin A, Regland B, Blennow K, Tarkowski A. Local and systemic GM-CSF increase in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;103:166–174. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2001.103003166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garden GA, Moller T. Microglia biology in health and disease. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2006;1:127–137. doi: 10.1007/s11481-006-9015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glass CK, Saijo K, Winner B, Marchetto MC, Gage FH. Mechanisms underlying inflammation in neurodegeneration. Cell. 2010;140:918–934. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cameron B, Landreth GE. Inflammation, microglia, and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;37:503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zaheer S, Thangavel R, Sahu SK, Zaheer A. Augmented expression of glia maturation factor in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 2011;194:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.07.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]