Abstract

Prenatal alcohol exposure can cause a range of physical and behavioral alterations; however, the outcome among children exposed to alcohol during pregnancy varies widely. Some of this variation may be due to nutritional factors. Indeed, higher rates of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) are observed in countries where malnutrition is prevalent. Epidemiological studies have shown that many pregnant women throughout the world may not be consuming adequate levels of choline, an essential nutrient critical for brain development, and a methyl donor. In this study, we examined the influence of dietary choline deficiency on the severity of fetal alcohol effects. Pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats were randomly assigned to receive diets containing 40, 70, or 100% recommended choline levels. A group from each diet condition was exposed to ethanol (6.0 g/kg/day) from gestational day 5 to 20 via intubation. Pair-fed and ad lib lab chow control groups were also included. Physical and behavioral development was measured in the offspring. Prenatal alcohol exposure delayed motor development, and 40% choline altered performance on the cliff avoidance task, independent of one another. However, the combination of low choline and prenatal alcohol produced the most severe impairments in development. Subjects exposed to ethanol and fed the 40% choline diet exhibited delayed eye openings, significantly fewer successes in hind limb coordination, and were significantly overactive compared to all other groups. These data suggest that suboptimal intake of a single nutrient can exacerbate some of ethanol’s teratogenic effects, a finding with important implications for the prevention of FASD.

Keywords: fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, prenatal ethanol, open field activity, hindlimb coordination, cliff avoidance, choline deficiency

1. Introduction

Individuals exposed to alcohol prenatally may suffer from fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD), which include a range of physical, neuropathological, and behavioral alterations (Hofer and Burd, 2009; Mattson et al., 2013; Riley et al., 2011). Physical effects include reduced birth weight, facial dysmorphology (long, flat philtrum, low nasal bridges, short palpebral fissures, thin upper lips, ear malformations, flattened maxilla, and epicanthal folds), as well as muscular, cardiac, and skeletal malformations (Feldman et al., 2012; Hofer and Burd, 2009). Prenatal alcohol exposure can also lead to neuropathology in a variety of brain regions (Donald et al., 2015; Riley et al., 2011) that affect an array of behavioral and cognitive domains, leading to learning impairments, attention deficits, motor dysfunction, altered social behavior, mood disorders, and changes in sleep and stress responses (Kelly et al., 2000; Mattson et al., 2011; Moore et al., 2014; Riley et al., 2011; Tsang et al., 2016).

The outcomes among children prenatally exposed to alcohol vary widely. Numerous risk factors may contribute to this variability, including the dose, developmental timing, pattern of alcohol consumption, polydrug use, genetic factors, as well as prenatal care. Variability in outcome may also be related, in part, to nutritional factors. Nutritional deficiencies, even without the presence of alcohol, can lead to serious abnormalities in physical and central nervous system (CNS) development (Georgieff, 2007; Keen et al., 1998). But the combination of poor prenatal nutrition and alcohol exposure may be even more damaging to the developing fetus (Keen et al., 2010). For example, animal studies have shown that the teratogenic effects of alcohol, including low birth weight (Wiener et al., 1981), physical anomalies (Weinberg et al., 1990), and brain damage (Wainwright and Fritz, 1985), are more severe when consumed with suboptimal nutrition, although blood alcohol levels are often higher among malnourished subjects (Wiener et al., 1981). This is alarming, given that heavy alcohol use is associated with nutrient deficiencies (Gloria et al., 1997), in part because of poor nutritional intake and in part because alcohol can interfere with nutrient absorption and utilization (Bode and Bode, 2003). Alcohol can also impair placental transfer of nutrients (Syme et al., 2004), so the fetus may be at higher risk of poor nutritional state when exposed to alcohol. Indeed, higher rates of FASD are observed in populations where malnutrition is prevalent (May et al., 2016a; May et al., 2014).

Interestingly, both animal and clinical studies have shown that deficiencies in specific nutrients can exacerbate the teratogenic effects of prenatal alcohol exposure. Prenatal zinc deficiency can lower fetal and offspring body weights, increase resorption rates, and increase physical malformations associated with prenatal alcohol exposure (Dreosti and Partick, 1987; Keen et al., 2010; Keppen et al., 1985; Miller et al., 1983; Ruth and Goldsmith, 1981). Similarly, iron deficiency exacerbates neuropathology and behavioral deficits, such as impaired learning, associated with prenatal alcohol exposure (Beard and Connor, 2003; Congdon et al., 2012; Huebner et al., 2016; Huebner et al., 2015; Rufer et al., 2012).

Choline is among these nutrients that are essential for normal CNS development (Food and Nutrition Board, 1998; Zeisel, 2013; Zeisel and Niculescu, 2006). Choline is found in a variety of foods, including eggs, liver, meats, and some vegetables (see https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400525/Data/Choline/Choln02.pdf). Choline is important for various cellular functions, and is a precursor to cell membrane constituents such as the phospholipids, phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin, and choline can act as the precurso Such disruptions to brain development can ultimately lead to significant behavioral deficits. Prenatal choline deficiency leads to long-lasting impairments in memory function (McCann et al., 2006; Meck and Williams, 1999), attention, temporal processing (Meck and Williams, 1997a, b), and sensory inhibition (Stevens et al., 2008b).

We have previously shown that prenatal or early postnatal choline supplementation can attenuate many of the behavioral alterations associated with developmental alcohol exposure (Monk et al., 2012; Ryan et al., 2008; Thomas et al., 2009; Thomas et al., 2004; Thomas et al., 2010; Thomas et al., 2000). However, it is not known how choline deficiency during pregnancy influences the severity or incidence of ethanol’s teratogenicity. The present study examined the effects of manipulating dietary choline levels in an animal model of FASD. Subjects were given diets that contained 100%, 70%, or 40% recommended choline levels to mimic the levels of dietary choline during pregnancy that have been reported in epidemiological studies (Gossell-Williams et al., 2005; Shaw et al., 2004). The present study investigated the effects of concomitant prenatal ethanol exposure and reduced dietary choline on physical and behavioral development.

2. Materials and Methods

All procedures included in this study were approved by the SDSU IACUC and are in accordance with the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.1 Subjects and Treatment

Eighty-four female Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, Hollister, CA) at the Center for Behavioral Teratology vivarium at San Diego State University (SDSU) were randomly assigned to one of nine groups in a 3 (Diet: 40%, 70%, or 100% levels of recommended choline (Dyets Company, Bethlehem, PA)) × 3 (Prenatal Exposure: ethanol, pair-fed control, or ad lib control) design. The diets contained the following levels of choline bitartrate: 1 g/kg, 1.75 g/kg, and 2.5 g/kg, respectively. Subjects were individually housed in a temperature and humidity controlled room with ad lib access to diet and water. Subjects were placed on the appropriate diet for 2 weeks prior to conception, throughout pregnancy, and during lactation (up to PD 21). Daily food intake was measured. After 7 days on the diet, subjects were acclimated to intragastric intubations of isotonic saline for 7 days before mating.

After the 14-day acclimation period to both the diet and intragastric intubations, the female rats were housed with Sprague-Dawley male rats until a seminal plug was found, which indicated mating and was designated as gestational day (GD) 0. Pregnant females were then singly housed and assigned to one of three prenatal treatments: 6.0 g/kg/day ethanol from GD 5–20 via intragastric intubation (EtOH), pair-fed control (PF), or ad lib chow control (LC).

Ethanol was administered via a single intragastric intubation (6.0 g/kg) each day from GD 5 through 20 in a binge-like manner. This is an ethanol dose that produces clinically relevant blood alcohol levels and is a model we have used in the past (Thomas et al., 2009; Thomas et al., 2010). To control for any reductions in food intake related to ethanol intoxication, PF controls were included. Each PF subject was matched in weight with an EtOH subject; the food availability of the PF dam was then yoked to that of the EtOH subject. The PF controls were intubated with isocaloric maltose, instead of ethanol, to control for the stress of intubation and ethanol-related calories (Thomas et al., 2009; Thomas et al., 2010). To determine whether restricted feeding had any effect, a lab chow group with ad lib access to food was also included. This control group was intubated with a saline solution daily from GD 5–20 (EtOH+40 n=9; EtOH+70 n=10; EtOH+100 n=11; LC+40 n=9; LC+70 n=8; LC+100 n=9; PF+40 n=10; PF+70 n=9; PF+100 n=9).

Litters were culled pseudorandomly to 10 pups (5 males, 5 females whenever possible) on PD 1. On PD 5, India ink was injected into the subjects’ paws for individual identification. Investigators remained blind to treatment conditions during evaluation of all outcome measures. To control for litter effects, body weight and physical developmental milestones (i.e. ears unfurling, eye opening, fur appearance, teeth eruption) were determined for all pups in each litter and litter means were used for each data point. In contrast, one sex pair from each litter was used for all reflex development testing and another sex pair for activity testing.

2.2 Blood Alcohol Level

On GD 5 and 20, 3 hours after the ethanol intubation, 20 μL of blood were obtained from the pregnant females via tail clip to obtain peak blood alcohol levels. Blood samples were analyzed using an Analox Alcohol Analyzer (Model AM1, Analox Instruments; Lunenburg, MA).

2.3 Physical Development

Physical developmental parameters included ear (pinna) unfurling, eye opening, fur appearance, and teeth eruption. Ear unfurling and fur appearance were recorded from PD 2, tooth eruption from PD 7, and eye opening from PD 12. Ear unfolding was recorded when the ears were in the fully erect position. Eye opening was defined as a full slit length break in the membrane covering the eye. Recording of these parameters continued until all were present in the rat pups.

2.4 Reflex Development Testing

2.4.1 Cliff Avoidance Reflex

From PD 5–12, subjects were placed with their heads and front paws over the edge of a platform. The latency to retract their body 1.5 cm from the edge was measured each day. Subjects were tested for two consecutive trials. If the subject was unable to retract their body fully within the allotted time (30 seconds), it was considered unsuccessful. Falls off of the ledge were also recorded.

2.4.2 Grip Strength and Hind Limb Coordination

From PD 12–20, each subject was suspended by its forefeet from a wire 2 mm in diameter. The duration of suspension was measured until the subject fell or 30 seconds elapsed. A successful grasp trial was recorded if the subject was able to hold on for the entire 30-second trial. A successful hind limb coordination trial was recorded if the subject was able to place one of its hind limbs on the wire; latency to hindlimb success was also recorded. Subjects were tested for 2 trials per day, for up to 30 seconds/trial.

2.5 Locomotor Activity

From PD 18 to 21, subjects’ activity levels were measured in an automated open field chamber made of plexiglas (46 cm wide × 46 cm long × 38 cm deep). Each open field was housed in a sound-attenuating chamber that also contained a fan that provided ventilation. White noise was played in the room to further mask outside noises and a dim red light lit the testing rooms. The open field contained a grid of infrared beams (Motor Monitor Version 4.10, Hamilton Kinder, LLC, Poway, CA) that tracked each subject’s movement.

Subjects were acclimated to the testing room for 30 minutes before testing. Each testing chamber was carefully cleaned before testing to remove any odors. Each subject was initially placed in the open field, facing the front wall. Activity was recorded in 5-minute bins for a period of 1 hour per day during the subjects’ dark cycle. Outcomes measured were total distance traveled, the number of beam breaks (basic movements), the number of rearing movements, and the number of entries and time spent in the center of the chamber.

2.6 Data Analyses

Data were analyzed with ANOVAs using SPSS software. Prenatal Exposure (EtOH, PF, LC), Diet (40%, 70%, 100% Choline), and Sex (male, female) served as between-subject factors. Dependent variables measured across time were analyzed with repeated measures. For offspring physical developmental milestones, the mean of each litter was determined and analyzed as a single data point; however, for behavioral testing, only a single sex pair per litter was tested to control for potential litter effects. Student Newman-Keuls follow-up post-hoc analyses were conducted with p<.05. Chi-square analyses followed by Fisher’s exact probability analyses were conducted to compare percentage of subjects reaching criterion for each day in the reflex development tasks. Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric analyses were conducted on gestational length.

3. Results

3.1 Maternal Body Weight

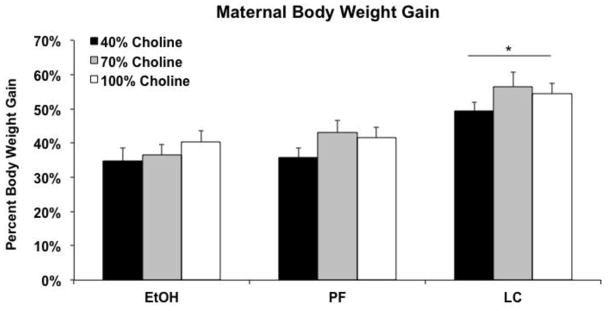

Percent body weight gain is shown in Figure 1. LC dams gained significantly more weight compared to the PF and EtOH-treated dams, producing a main effect of Prenatal Exposure [F(2,70) = 18.0, p<.001]; maternal body weight gain of PF and EtOH-treated dams were not significantly different from each other. There were no significant main or interactive effects of diet on body weight gain.

Figure 1.

Mean (+SEM) percent body weight gain during pregnancy. * = Lab chow (LC) dams gained significantly more weight compared to the pair-fed (PF) and ethanol (EtOH)-treated dams.

3.2 Blood Alcohol Level (BAL)

Diet condition did not affect peak BAL (all p’s >.05). Only a significant main effect of Gestational Day was found [F(1,25) = 12.3; p<.05], as peak BALs were higher on GD 20 (239.1 ± 15.7 mg/dL) compared to GD 5 (185.6 ± 11.2 mg/dL).

3.3 Litter Size, Sex Ratio, and Gestation Length

No significant effects of Prenatal Exposure or Diet were found on litter size or male to female ratio within each litter (all p’s>.05). All litters were born on GD 22 except that 1 litter (EtOH+40 group) was born on GD 23, 3 litters (2 LC+70 and 1 LC+100) were born on GD 21 and one LC+40 was born on GD 20. Thus, gestational length of LC controls was significant shorter than that of PF and EtOH groups (Kruskal-Wallis, p<.05).

3.4 Offspring Body Weights

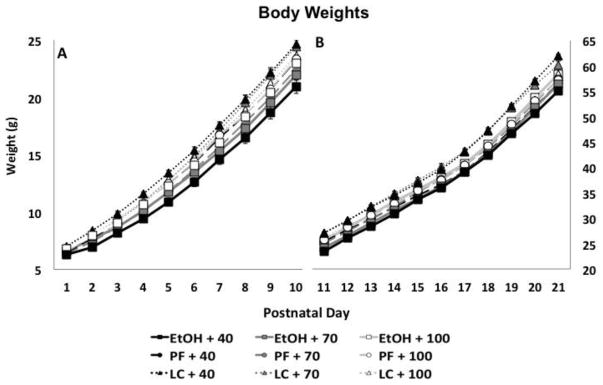

Prenatal ethanol exposure and a choline-deficient diet significantly influenced the offspring’s body weights from PD 1 to 21 (Figure 2). A significant Day × Diet × Prenatal Exposure interaction was found [F(80,2780) = 3.2, p<.001], in addition to Day × Prenatal Exposure [F(40, 2780) = 6.4, p<.001], Prenatal Exposure × Diet [F(4,139) = 2.5, p<.05] and a main effect of Prenatal Exposure [F(2,139) = 11.5, p<.001]. Across early postnatal development, LC subjects weighed more than EtOH and PF subjects. Diet did not modify growth among the PF or LC controls. However, from birth up to PD 10, the EtOH subjects fed the 40% diet weighed less than all groups except EtOH+70 and PF+70 groups, and from PD 11–21, EtOH subjects fed 40% or 70% choline weighed less than LC controls fed 40% or 70% choline. Finally, all subjects gained weight over days, and males gained weight at a faster rate than females, producing significant effects Day × Sex [F(20, 2780) = 5.5, p<.001], Day [F(20, 2780) = 20720, p<.001] and Sex [F(1,139) = 11.7, p<.001] (data not shown). There were no interactions of sex with diet or prenatal exposure.

Figure 2.

Mean (± SEM) body weights of offspring from postnatal day (PD) 1 to 10 (Panel A) and PD 11–21 (Panel B).

3.5 Physical Developmental Milestones

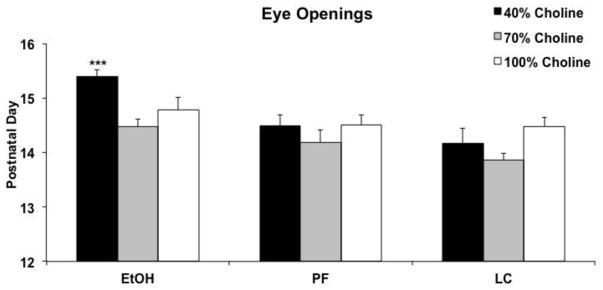

The combination of EtOH and a 40% choline diet significantly delayed eye opening (Figure 3). There was a significant interaction of Diet and Prenatal Exposure [F(4,70) = 2.9, p<.05] on the day of eye opening, as well as main effects of Prenatal Exposure [F(2,70) = 13.3, p<.001] and Diet [F(2,70) = 6.4, p<.01]. Follow up analyses confirmed that eye opening was significantly delayed in ethanol-exposed subjects fed a 40% choline diet compared to controls fed a 40% diet [F(2,26) = 11.5, p<.001], as well as all other ethanol-exposed groups [F(2,24) = 10.6, p<.001]. There were no significant effects of ethanol in either the 70% or 100% choline diet conditions. In fact, all but one litter exposed to ethanol and fed 40% choline had average eye openings after PD 15 (88%), compared to 15% of subjects in all other groups combined. No significant effects of prenatal alcohol exposure or diet were found for day of ear unfurling, fur appearance, nor for day of teeth eruption (all p’s >.05; results not shown). In addition, there were no significant main or interactive effects of sex on any measures.

Figure 3.

Mean (+ SEM) age that both eyes opened. Age of eye opening was significantly delayed among ethanol-exposed subjects also fed a diet with 40% choline levels. *** = significantly different from all other groups.

3.6 Reflex Development

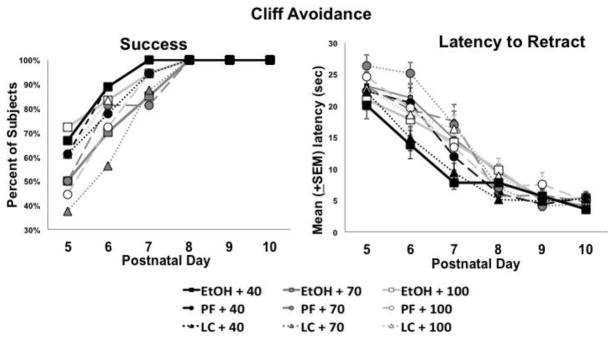

3.6.1 Cliff Avoidance

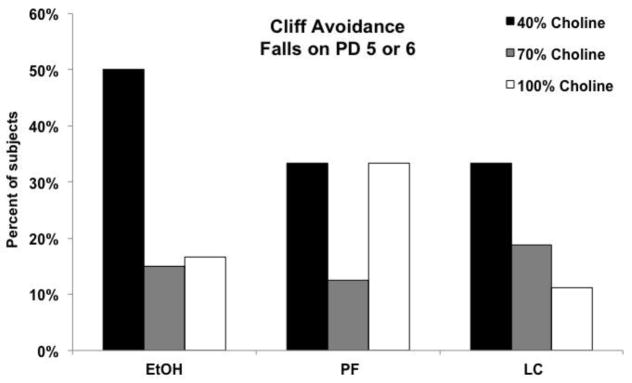

Low dietary choline significantly affected performance on the cliff avoidance task. First, subjects fed the 40% choline diet were more likely to fall off of the platform edge on the first two days of testing (PD 5 or 6) [Chi-square (2) = 8.7, p<.05]. Fisher’s exact probability follow-ups confirmed that more subjects from the 40% choline diet fell compared to subjects fed 70% or 100% diet (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Percent of subjects that fell from the platform edge during a cliff avoidance task. Significantly more subjects from the 40% choline diet fell compared to subjects fed 70% or 100% choline diets.

Despite being more likely to fall, subjects fed 40% choline diet were more able to retract from the edge of the platform in under 30 sec (Figure 5A; note that subjects had two trials each day, so they could have both a fall and success within the same day). In fact, subjects fed 40% choline were more successful on PD 5 & 6 compared to those fed 70% choline [Chi-square = 5.3, p<.05], with subjects fed 100% choline intermediate, not differing significantly from other diet conditions. Moreover, subjects from the 40% choline diet groups had shorter latencies compared to other groups early in testing, producing a significant interaction of Diet by Day [F(12,846) = 3.1, p<.001] and Diet [F(2,141)= 5.4, p<.01] (Figure 5B). Beginning on PD 6, the groups fed 40% choline had significantly shorter latencies compared to those fed 70% choline; latencies of subjects fed 100% choline were intermediate but not significantly different from that of other diet groups [F(2,142)= 4.8, p<.01]. By PD 7 (Figure 5B), the 40% choline diet groups were significantly faster to retract from the edge compared to all other diet groups [F(2,142)= 8.5, p<.001]. No significant main or interactive effects of ethanol or sex were found (all p’s >.05).

Figure 5.

Percent of subjects that were able to successfully retract from the platform edge in under 30 seconds. Despite falling, subjects fed the 40% choline diet were more successful at retracting from the platform compared to controls (Panel A). Similarly, subjects fed the 40% choline diet were significantly faster at retracting from the edge compared to subjects fed 70% or 100% choline diets (Panel B).

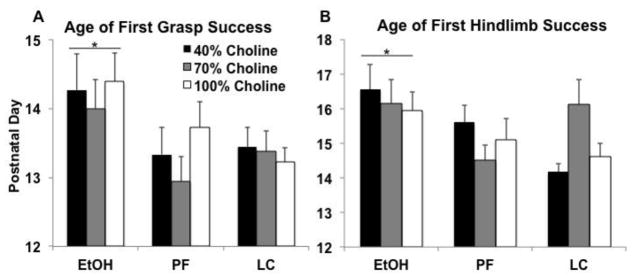

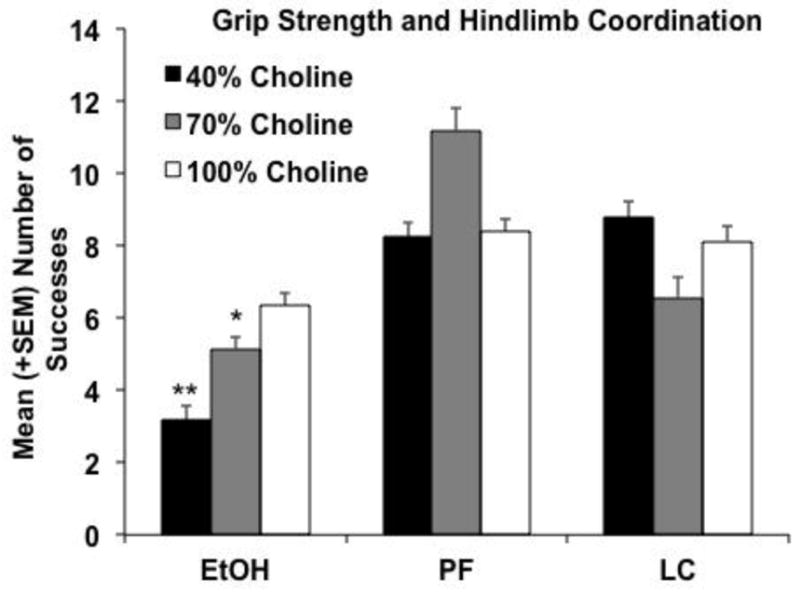

3.6.2 Grip Strength and Hindlimb Coordination

Three subjects in the EtOH+40 group and one subject in the EtOH+70 group were unable to hang onto the bar for 30 sec throughout testing. Even with those subjects removed from the analyses, prenatal ethanol exposure significantly delayed the age of the first successful grip trial compared to both control groups, and this was not significantly modified by diet (main effect of Prenatal Exposure [F(2,138) = 5.6, p<.01]; Figure 6A). Similarly, three EtOH+40, three EtOH+70, one EtOH+100, one PF+40, one PF+70, and two LC+70 subjects were not able to get their hindlimb up onto the bar. With the removal of data from these subjects, ethanol-related delays on the age of the first hindlimb success did not reach significance (p<.1). However, if PD 21 (the day after testing) was put as an age of success for those who failed, success was significantly delayed in ethanol-exposed subjects compared to both control groups [F(2,142) = 4.6, p<.05]. Thus, prenatal alcohol exposure significantly delayed motor function on this task.

Figure 6.

Grip strength and hindlimb coordination. Prenatal ethanol exposure significantly (*) delayed the age of the first successful grasp (Panel A) and first hindlimb coordination success (Panel B), when compared to LC and PF groups.

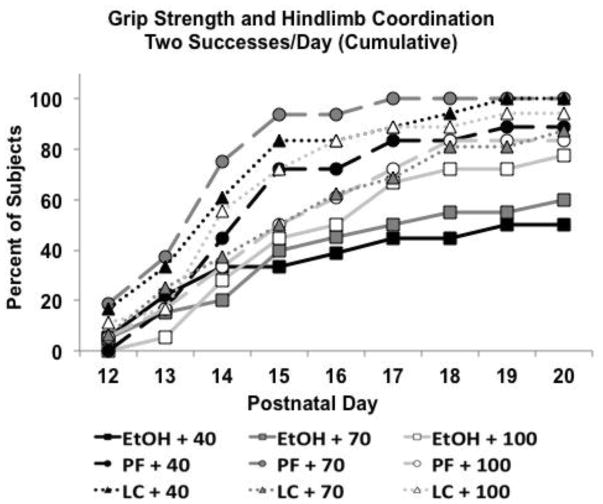

However, when overall success and performance consistency were examined, choline diet did modify ethanol’s effects. The number of successful trials (either hanging on for 30 sec or getting their hindlimb up on the bar) is shown in Figure 7. Ethanol-exposed subjects fed a 40% choline diet performed significantly worse than all other groups, except the ethanol-exposed subjects fed 70% choline. Ethanol-exposed subjects fed 70% choline performed significantly worse than all controls except LC+70 group, producing a significant interaction of Prenatal Exposure × Diet [F(4,142) = 3.5, p<.01], as well as a main effect of Prenatal Exposure [F(2,142) = 19.2, p<.001]. A similar pattern was seen for success in hindlimb coordination alone. Success in both trials within a day is even more challenging. Figure 8 shows the percent of subjects successful on both trials/day when calculated cumulatively. By PD 15, fewer ethanol-exposed subjects had 2 successes/day compared to all groups except PF+100 and LC+70 [χ2(8) = 25.5, p<.01; Fisher exact probabilities p’s<.05]. This pattern continued for ethanol-exposed subjects fed 70% choline, but by PD 18–20, fewer ethanol-exposed subjects fed 40% choline had achieved 2 successes/day compared to all control groups. Finally, over time, more ethanol-exposed subjects fed 100% choline were successful; however, there were still fewer subjects that had achieved 2 successes/day compared to PF+70 and LC+100 subjects from PD 16–20. Thus, the severity of ethanol-related impairments in performance was affected by the severity of the choline deficiency.

Figure 7.

Grip strength and hindlimb coordination (either hanging for 30 seconds or getting the hindlimb to the rod). EtOH-exposed subjects fed 40% choline were significantly less successful than all groups except the EtOH+70 group. EtOH-exposed subjects fed 70% choline were less successful than all controls except the LC+70 group. ** = significantly different from all groups except EtOH+70; * = significantly different from all controls except EtOH+40 and LC+70 groups.

Figure 8.

For the cumulative percentage of subjects successful for both trials/day, the severity of ethanol-related impairments in performance was affected by the severity of the choline deficiency.

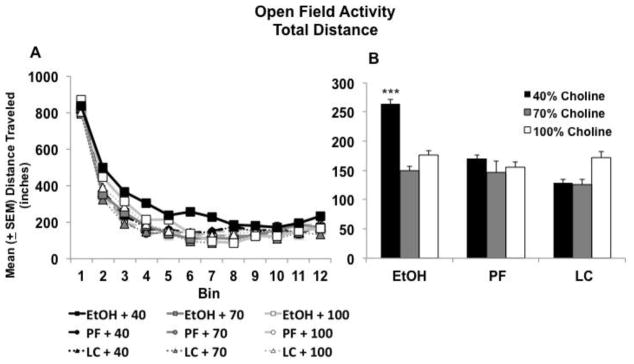

3.6.3 Locomotor Activity

Prenatal ethanol exposure and choline deficiency during development had a significant effect on the total distance traveled in the open field. Subjects exposed to prenatal alcohol and fed 40% choline took longer to habituate during the open field sessions, producing an interaction of Prenatal Exposure × Diet × Day × Bin [F(44,1639)= 1.9, p<.001], Prenatal Exposure × Diet × Bin [F(44,4620) = 1.4, p<.001], Prenatal Exposure × Day × Bin [F(66, 2640)= 1.5, p<.001], Diet × Day × Bin [66,26400 = 1.3, p<.05], as well as a main effect of Prenatal Exposure [F(2,140)= 4.5, p<.05]. As seen in Figure 9A, although groups did not differ in locomotor activity at the beginning of the session, ethanol-exposed subjects fed a 40% choline diet were more active during the next 30 minutes of the first three days of testing, eventually habituating to control levels by the end of the session. Figure 9B shows activity collapsed across 10–40 minutes (bins 3–8) within the session for PD 18–20. The combination of prenatal alcohol and low dietary choline (40%), but neither condition alone, significantly increased activity levels, producing a significant interaction Prenatal Exposure × Diet [F(2,140) = 2.5, p<.05], as well as main effects of Prenatal Exposure [F(2,140) = 4.6, p<.05] and Diet [F(2,140) = 3.0, p<.05]. All subjects habituated within sessions and across days, producing significant effects of Day [F(3,420) = 91, p<.001] and Bin [F(11,1540) = 924.5, p<.001].

Figure 9.

Subjects exposed to prenatal alcohol and 40% choline diet took longer to habituate in the open field (A). Data from bins 3–8 are collapsed in Panel B. *** = significantly different from all other groups.

A similar pattern was seen for other activity measures, including total number of beam breaks, and the number of center entries (results not shown). No significant or meaningful effects or interactions were observed for number of rearing movements, or time spent in the center (results not shown). In addition, there were no significant main or interactive effects of sex on any measures.

4. Discussion

The present study is the first to illustrate that reduced dietary choline intake can exacerbate some of the teratogenic effects of prenatal alcohol exposure, affecting early physical and behavioral development. These findings provide evidence that even suboptimal levels of a single nutrient can modify the expression of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. In fact, on most measures, prenatal alcohol exposure did not significantly affect development unless there was a concomitant reduction in dietary choline level (see Table 1 for summary).

Table 1.

| Measure | Specific EtOH Effect | Specific Choline Deficiency Effect | EtOH × Choline Deficiency Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day of Eye Opening |

|

|||

| Cliff Avoidance | #Falls |

|

||

| Ability to Retract |

|

|||

| Grip Strength and Hindlimb Coordination | Age of First Success |

|

||

| #Successes |

|

|||

| Locomotor Activity |

|

|||

Ear unfurling, fur appearance, teeth eruption, and eye opening all mark significant milestones in offspring development (Heyser, 2004), and impaired development of these milestones may predict later behavioral changes (Schuch et al., 2016). Eye opening was the only milestone significantly delayed in the current study. The combination of 40% choline and prenatal alcohol significantly delayed the age of eye opening, even when either factor by itself did not. Although prenatal alcohol exposure itself can delay eye opening (Kelly et al., 1987; Stromland and Pinazo-Duran, 2002; Thomas et al., 2009), we did not find that in the present study.

Similarly, it was the combination of low dietary choline and alcohol that impaired motor coordination on the hindlimb task and increased activity levels. Ethanol-exposed subjects that were fed 40% choline were less successful in hanging from the bar and coordinating their hindlimbs. Similarly, ethanol-exposed subjects fed 40% choline exhibited less habituation in locomotor activity within the open field chambers. These data suggest that pregnant women who are drinking alcohol and also consuming low levels of dietary choline may be placing their fetus at higher risk for FASD. These findings may have real implications for clinical populations. Importantly, this study did not induce a severe choline deficiency, but one that is reported in human populations both within (Caudill, 2010; Chester et al., 2011; Shaw et al., 2004) and outside the U.S. (Gossell-Williams et al., 2005; Masih et al., 2015; May et al., 2016b). Analyses of choline intake in the 2003–2004 NHANES study indicated that over 90% of pregnant women in the US consumed well below the adequate intake level of 450 mg/d (Jensen et al., 2007), whereas 87% of pregnant women studied in a Canadian sample were consuming dietary choline a third below adequate intake levels (Masih et al., 2015). In fact, in South Africa, mothers of children, both with or without FASD, were consuming around 50% of adequate levels of choline (May et al., 2016b) and in one report they found lower choline intake among women with children with FASD compared to those with control children (May et al., 2014). Moreover, there was a significant negative correlation between choline intake and child head circumference and palpebral fissure length (May et al., 2016b). Thus, epidemiological data indicate that pregnant women across the globe are not consuming adequate choline and this may convey greater risk to FASD in their fetus if they are also drinking alcohol.

Importantly, numerous genetic polymorphisms influence choline metabolism, creating variability in the level of dietary choline needed for normal development (da Costa et al., 2006; Kohlmeier et al., 2005; Resseguie et al., 2011). For example, dietary choline needs may be affected by genetic variations in phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PEMT) (da Costa et al., 2006) or methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase (MTHFD) (Kohlmeier et al., 2005). Even genetic variation in folate needs may also affect required dietary choline levels (Ganz et al., 2016). If reductions in dietary choline availability increase risk for FASD, it is likely that individuals with genetic polymorphisms that require more dietary choline may be at higher risk for having a child with FASD if they drink during pregnancy. The combination of genetic risk factors and low dietary choline may be particularly risky.

Low dietary choline intake and prenatal alcohol exposure also had independent effects. For example, 40% prenatal choline deficiency altered performance on the cliff avoidance task, a developmental reflex that requires sensory and motor integration (Santillan et al., 2010). Although offspring exposed to a 40% choline diet were faster at retracting from the cliff, they also were more likely to fall, suggesting that they may have had increased arousal and/or activity which affected their performance (Bailey et al., 1986; Sandberg et al., 1984). These findings are notable, as most studies examining dietary choline deficiency during prenatal development completely eliminate choline from the diet during a critical period (Stevens et al., 2008a; Wong-Goodrich et al., 2011), rather than varying choline levels. Thus, the current study would suggest that suboptimal dietary choline intake (40%), by itself, may adversely affect behavioral development. Given that pregnant women around the world consume suboptimal choline levels, the consequences could be more harmful than previously recognized.

In contrast, prenatal alcohol exposure by itself significantly delayed grip strength and hindlimb coordination, a result that has been previously demonstrated (Bowen et al., 2005; Hannigan, 1995; Kelly et al., 1987; Thomas et al., 2009). It was somewhat surprising that we did not see more effects of ethanol exposure by itself, as we have previously reported delays in eye opening, incisor emergence, and the developmental reflexes (Thomas et al., 2009) following the same prenatal alcohol exposure paradigm. It is not clear why this is the case, especially since BALs were similar in both studies.

Importantly, varying dietary choline levels had no significant effect on peak BAL, suggesting the adverse effects of low choline and alcohol were not due to differences in ethanol absorption or rate of metabolism in the dams. Data from our lab also indicate that prenatal alcohol exposure does not affect maternal or fetal plasma choline levels; similarly, Coles and colleagues did not find differences in plasma choline levels in alcohol-using pregnant women compared to non-alcohol-using pregnant women (Coles et al., 2015). However, it is possible that prenatal alcohol exposure exacerbates the effects of low dietary choline deficiency on choline metabolism. It is also important to recognize that nutrients can interact with one another (Keen et al., 2010; Sandstrom, 2001) and choline deficiency may result in secondary nutritional deficiencies or demands. For example, choline, methionine, and folate metabolism interact at the point that homocysteine is converted to methionine, and perturbing any one of these methyl donors results in compensatory changes (Zeisel et al., 1991). In addition, higher folate levels are needed to compensate for low methionine levels in individuals who are choline deficient (Niculescu and Zeisel, 2002).

Although we do not yet know the consequences of reduced dietary choline (40%) on brain development of subjects exposed to alcohol prenatally, numerous animal studies have shown that choline deficiency (0% choline) during mid-pregnancy (GD 11–17) is damaging to the developing fetus. Prenatal choline deficiency during this period significantly reduces brain size (Wang et al., 2016), impairs neural progenitor cell proliferation (Craciunescu et al., 2003; Niculescu et al., 2006), disrupts differentiation, and increases apoptosis (Albright et al., 1999; Yen et al., 2001; Zeisel, 2006). Moreover, prenatal choline deficiency may impair neural plasticity beyond early development (Glenn et al., 2007). All of the above may contribute to our current findings, particularly when we note that prenatal alcohol exposure can disrupt many of these same processes. For example, ethanol significantly alters cell proliferation (Guerri et al., 2001) disrupts differentiation (Zhou et al., 2001), increases apoptosis (Idrus and Napper, 2012), and compromises lifespan neuroplasticity (Gil-Mohapel et al., 2010).

In contrast, prenatal choline supplementation increases cell proliferation and neurogenesis (Craciunescu et al., 2003), reduces apoptosis (Albright et al., 1999), and leads to long-lasting morphological (Li et al., 2004; Williams et al., 1998), neurochemical (Glenn et al., 2007), and functional changes (Li et al., 2004; Williams et al., 1998) in the CNS. Such changes in brain development are associated with enhanced performance on a number of cognitive tasks, including temporal memory, spatial memory (Brandner, 2002; Meck and Williams, 2003), attentional processing (Meck and Williams, 1997a, b), and sensory inhibition (Stevens et al., 2008b). Such effects are evident even in aged subjects (27 months of age), months after choline supplementation has been terminated (Meck and Williams, 2003).

Moreover, choline supplementation can be neuroprotective against a variety of insults (Blusztajn and Mellott, 2013). We have demonstrated that prenatal choline supplementation mitigates ethanol-related reductions in birth and brain weights, delays in incisor emergence, and delays in reflex development, including impairments in hindlimb coordination (Thomas et al., 2009). Subjects prenatally exposed to alcohol also exhibit delayed development of spontaneous alternation behavior and deficits on working memory during adulthood, effects that were mitigated with prenatal choline supplementation (Thomas et al., 2010). In fact, choline can also improve cognitive abilities among animals developmentally exposed to alcohol, even when the choline is administered postnatally (Ryan et al., 2008; Schneider and Thomas, 2016; Thomas et al., 2007; Thomas et al., 2010; Thomas et al., 2000; Thomas and Tran, 2012; Wagner and Hunt, 2006). Recent clinical data also suggest that early choline supplementation shows potential for mitigating some adverse effects of prenatal alcohol exposure (Kable et al., 2015; Wozniak et al., 2015). The present data suggest that if pregnant women are drinking alcohol and also consuming inadequate dietary choline, then correcting that inadequacy could, by itself, reduce the risk of FASD.

Conclusions

Although alcohol-induced undernutrition has been considered one of the provocative factors for FASD (Abel and Hannigan, 1995; Keen et al., 2010), the concomitant effects of alcohol consumption and specific nutrient deficiencies on the developing fetus are not well-understood (Amos-Kroohs et al., 2016; Fuglestad et al., 2013; Nguyen et al., 2016; Werts et al., 2014), nor are the long-lasting effects of prenatal ethanol on nutritional status and metabolism of the child. Our findings illustrate that suboptimal dietary choline during pregnancy exacerbates ethanol’s teratogenic effects. These findings should be of concern, given that women around the globe are not consuming adequate choline during pregnancy. Importantly, these results have implications for identifying populations at a higher risk for having a child with FASD. Elucidation of how nutritional factors influence alcohol’s teratogenic effects is critical both for effective prevention and treatment of FASD.

Highlights.

Prenatal alcohol exposure in rats disrupted development, delaying motor development

A low choline diet during the perinatal period altered sensorimotor development

Low choline diet and alcohol severely disrupted physical and behavioral development

Suboptimal intake of choline perinatally can exacerbate ethanol’s teratogenic effects

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIAAA grant AA12446 and AA014811.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abel EL, Hannigan JH. Maternal risk factors in fetal alcohol syndrome: provocative and permissive influences. Neurotoxicology and teratology. 1995;17(4):445–462. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(95)98055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albright CD, Friedrich CB, Brown EC, Mar MH, Zeisel SH. Maternal dietary choline availability alters mitosis, apoptosis and the localization of TOAD-64 protein in the developing fetal rat septum. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;115(2):123–129. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amos-Kroohs RM, Fink BA, Smith CJ, Chin L, Van Calcar SC, Wozniak JR, Smith SM. Abnormal Eating Behaviors Are Common in Children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. The Journal of pediatrics. 2016;169:194–200. e191. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey EL, Overstreet DH, Crocker AD. Effects of intrahippocampal injections of the cholinergic neurotoxin AF64A on open-field activity and avoidance learning in the rat. Behavioral and neural biology. 1986;45(3):263–274. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(86)80015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard JL, Connor JR. Iron status and neural functioning. Annual review of nutrition. 2003;23:41–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.23.020102.075739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blusztajn JK, Mellott TJ. Neuroprotective actions of perinatal choline nutrition. Clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine. 2013;51(3):591–599. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2012-0635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode C, Bode JC. Effect of alcohol consumption on the gut. Best practice & research. Clinical gastroenterology. 2003;17(4):575–592. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6918(03)00034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen SE, Batis JC, Mohammadi MH, Hannigan JH. Abuse pattern of gestational toluene exposure and early postnatal development in rats. Neurotoxicology and teratology. 2005;27(1):105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandner C. Perinatal choline treatment modifies the effects of a visuo-spatial attractive cue upon spatial memory in naive adult rats. Brain Res. 2002;928(1–2):85–95. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03363-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudill MA. Pre- and postnatal health: evidence of increased choline needs. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(8):1198–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chester DN, Goldman JD, Ahuja J, Moshfegh A. Dietary intakes of choline: What we eat in American, NHANES 2007–2008. Food Surveys Research Group Dietary Data Brief No.9 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Coles CD, Kable JA, Keen CL, Jones KL, Wertelecki W, Granovska IV, Pashtepa AO, Chambers CD, Cifasd Dose and Timing of Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and Maternal Nutritional Supplements: Developmental Effects on 6-Month-Old Infants. Maternal and child health journal. 2015;19(12):2605–2614. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1779-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congdon EL, Westerlund A, Algarin CR, Peirano PD, Gregas M, Lozoff B, Nelson CA. Iron deficiency in infancy is associated with altered neural correlates of recognition memory at 10 years. The Journal of pediatrics. 2012;160(6):1027–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craciunescu CN, Albright CD, Mar MH, Song J, Zeisel SH. Choline availability during embryonic development alters progenitor cell mitosis in developing mouse hippocampus. The Journal of nutrition. 2003;133(11):3614–3618. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.3614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa KA, Kozyreva OG, Song J, Galanko JA, Fischer LM, Zeisel SH. Common genetic polymorphisms affect the human requirement for the nutrient choline. FASEB J. 2006;20(9):1336–1344. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-5734com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donald KA, Eastman E, Howells FM, Adnams C, Riley EP, Woods RP, Narr KL, Stein DJ. Neuroimaging effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on the developing human brain: a magnetic resonance imaging review. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2015;27(5):251–269. doi: 10.1017/neu.2015.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreosti IE, Partick EJ. Zinc, ethanol, and lipid peroxidation in adult and fetal rats. Biological trace element research. 1987;14(3):179–191. doi: 10.1007/BF02795685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman HS, Jones KL, Lindsay S, Slymen D, Klonoff-Cohen H, Kao K, Rao S, Chambers C. Prenatal alcohol exposure patterns and alcohol-related birth defects and growth deficiencies: a prospective study. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2012;36(4):670–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher MC, Zeisel SH, Mar MH, Sadler TW. Inhibitors of choline uptake and metabolism cause developmental abnormalities in neurulating mouse embryos. Teratology. 2001;64(2):114–122. doi: 10.1002/tera.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher MC, Zeisel SH, Mar MH, Sadler TW. Perturbations in choline metabolism cause neural tube defects in mouse embryos in vitro. Faseb J. 2002;16(6):619–621. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0564fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Nutrition Board, I.o.M. Dietary reference intakes for thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B6, folate, vitamin B12, pantothenic acid, Biotin, and choline. National Academy Press; Washington, D.C: 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuglestad AJ, Fink BA, Eckerle JK, Boys CJ, Hoecker HL, Kroupina MG, Zeisel SH, Georgieff MK, Wozniak JR. Inadequate intake of nutrients essential for neurodevelopment in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) Neurotoxicology and teratology. 2013;39:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz AB, Shields K, Fomin VG, Lopez YS, Mohan S, Lovesky J, Chuang JC, Ganti A, Carrier B, Yan J, Taeswuan S, Cohen VV, Swersky CC, Stover JA, Vitiello GA, Malysheva OV, Mudrak E, Caudill MA. Genetic impairments in folate enzymes increase dependence on dietary choline for phosphatidylcholine production at the expense of betaine synthesis. FASEB J. 2016 doi: 10.1096/fj.201500138RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgieff MK. Nutrition and the developing brain: nutrient priorities and measurement. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2007;85(2):614S–620S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.2.614S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Mohapel J, Boehme F, Kainer L, Christie BR. Hippocampal cell loss and neurogenesis after fetal alcohol exposure: insights from different rodent models. Brain research reviews. 2010;64(2):283–303. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn MJ, Gibson EM, Kirby ED, Mellott TJ, Blusztajn JK, Williams CL. Prenatal choline availability modulates hippocampal neurogenesis and neurogenic responses to enriching experiences in adult female rats. The European journal of neuroscience. 2007;25(8):2473–2482. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05505.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloria L, Cravo M, Camilo ME, Resende M, Cardoso JN, Oliveira AG, Leitao CN, Mira FC. Nutritional deficiencies in chronic alcoholics: relation to dietary intake and alcohol consumption. The American journal of gastroenterology. 1997;92(3):485–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossell-Williams M, Fletcher H, McFarlane-Anderson N, Jacob A, Patel J, Zeisel S. Dietary intake of choline and plasma choline concentrations in pregnant women in Jamaica. The West Indian medical journal. 2005;54(6):355–359. doi: 10.1590/s0043-31442005000600002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerri C, Pascual M, Renau-Piqueras J. Glia and fetal alcohol syndrome. Neurotoxicology. 2001;22(5):593–599. doi: 10.1016/s0161-813x(01)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannigan JH. Effects of prenatal exposure to alcohol plus caffeine in rats: pregnancy outcome and early offspring development. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 1995;19(1):238–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyser CJ. Assessment of developmental milestones in rodents. Current protocols in neuroscience/editorial board Jacqueline N. Crawley … [et al.] 2004;Chapter 8(Unit 8):18. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0818s25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer R, Burd L. Review of published studies of kidney, liver, and gastrointestinal birth defects in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Birth defects research. 2009;85(3):179–183. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner SM, Blohowiak SE, Kling PJ, Smith SM. Prenatal Alcohol Exposure Alters Fetal Iron Distribution and Elevates Hepatic Hepcidin in a Rat Model of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. The Journal of nutrition. 2016 doi: 10.3945/jn.115.227983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner SM, Tran TD, Rufer ES, Crump PM, Smith SM. Maternal iron deficiency worsens the associative learning deficits and hippocampal and cerebellar losses in a rat model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2015;39(11):2097–2107. doi: 10.1111/acer.12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idrus NM, Napper R. Acute and Long-Term Purkinje Cell Loss Following a Single Ethanol Binge During the Early Third Trimester Equivalent in the Rat. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36(8):1365–1373. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen H, Batres-Marquez SAC, Schalinske K. Choline in the diets of the US population: NHANES, 2003–2004. The FASEB Journal. 2007:219. [Google Scholar]

- Kable JA, Coles CD, Keen CL, Uriu-Adams JY, Jones KL, Yevtushok L, Kulikovsky Y, Wertelecki W, Pedersen TL, Chambers CD, Cifasd The impact of micronutrient supplementation in alcohol-exposed pregnancies on information processing skills in Ukrainian infants. Alcohol (Fayetteville, N Y. 2015;49(7):647–656. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen Uriu-Adams JY, Skalny A, Grabeklis A, Grabeklis S, Green K, Yevtushok L, Wertelecki WW, Chambers CD. The plausibility of maternal nutritional status being a contributing factor to the risk for fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: the potential influence of zinc status as an example. BioFactors (Oxford, England) 2010;36(2):125–135. doi: 10.1002/biof.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen CL, Uriu-Hare JY, Hawk SN, Jankowski MA, Daston GP, Kwik-Uribe CL, Rucker RB. Effect of copper deficiency on prenatal development and pregnancy outcome. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1998;67(5 Suppl):1003S–1011S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.5.1003S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly SJ, Day N, Streissguth AP. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on social behavior in humans and other species. Neurotoxicology and teratology. 2000;22(2):143–149. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(99)00073-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly SJ, Hulsether SA, West JR. Alterations in sensorimotor development: relationship to postnatal alcohol exposure. Neurotoxicology and teratology. 1987;9(3):243–251. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(87)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppen LD, Pysher T, Rennert OM. Zinc deficiency acts as a co-teratogen with alcohol in fetal alcohol syndrome. Pediatric research. 1985;19(9):944–947. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198509000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlmeier M, da Costa KA, Fischer LM, Zeisel SH. Genetic variation of folate-mediated one-carbon transfer pathway predicts susceptibility to choline deficiency in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(44):16025–16030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504285102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Guo-Ross S, Lewis DV, Turner D, White AM, Wilson WA, Swartzwelder HS. Dietary prenatal choline supplementation alters postnatal hippocampal structure and function. Journal of neurophysiology. 2004;91(4):1545–1555. doi: 10.1152/jn.00785.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masih SP, Plumptre L, Ly A, Berger H, Lausman AY, Croxford R, Kim YI, O’Connor DL. Pregnant Canadian Women Achieve Recommended Intakes of One-Carbon Nutrients through Prenatal Supplementation but the Supplement Composition, Including Choline, Requires Reconsideration. The Journal of nutrition. 2015;145(8):1824–1834. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.211300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson SN, Crocker N, Nguyen TT. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: neuropsychological and behavioral features. Neuropsychology review. 2011;21(2):81–101. doi: 10.1007/s11065-011-9167-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson SN, Roesch SC, Glass L, Deweese BN, Coles CD, Kable JA, May PA, Kalberg WO, Sowell ER, Adnams CM, Jones KL, Riley EP, Cifasd Further development of a neurobehavioral profile of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2013;37(3):517–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01952.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, de Vries MM, Marais AS, Kalberg WO, Adnams CM, Hasken JM, Tabachnick B, Robinson LK, Manning MA, Jones KL, Hoyme D, Seedat S, Parry CD, Hoyme HE. The continuum of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in four rural communities in south africa: Prevalence and characteristics. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016a;159:207–218. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Hamrick KJ, Corbin KD, Hasken JM, Marais AS, Blankenship J, Hoyme HE, Gossage JP. Maternal nutritional status as a contributing factor for the risk of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Reproductive toxicology. 2016b;59:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Hamrick KJ, Corbin KD, Hasken JM, Marais AS, Brooke LE, Blankenship J, Hoyme HE, Gossage JP. Dietary intake, nutrition, and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. Reproductive toxicology. 2014;46:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann JC, Hudes M, Ames BN. An overview of evidence for a causal relationship between dietary availability of choline during development and cognitive function in offspring. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2006;30(5):696–712. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meck WH, Williams CL. Characterization of the facilitative effects of perinatal choline supplementation on timing and temporal memory. Neuroreport. 1997a;8(13):2831–2835. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199709080-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meck WH, Williams CL. Perinatal choline supplementation increases the threshold for chunking in spatial memory. Neuroreport. 1997b;8(14):3053–3059. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199709290-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meck WH, Williams CL. Choline supplementation during prenatal development reduces proactive interference in spatial memory. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;118(1–2):51–59. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meck WH, Williams CL. Metabolic imprinting of choline by its availability during gestation: implications for memory and attentional processing across the lifespan. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2003;27(4):385–399. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SI, Del Villano BC, Flynn A, Krumhansl M. Interaction of alcohol and zinc in fetal dysmorphogenesis. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1983;18(Suppl 1):311–315. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(83)90192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk BR, Leslie FM, Thomas JD. The effects of perinatal choline supplementation on hippocampal cholinergic development in rats exposed to alcohol during the brain growth spurt. Hippocampus. 2012;22(8):1750–1757. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore EM, Migliorini R, Infante MA, Riley EP. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: Recent Neuroimaging Findings. Current developmental disorders reports. 2014;1(3):161–172. doi: 10.1007/s40474-014-0020-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TT, Risbud RD, Chambers CD, Thomas JD. Dietary Nutrient Intake in School-Aged Children With Heavy Prenatal Alcohol Exposure. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2016;40(5):1075–1082. doi: 10.1111/acer.13035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niculescu MD, Craciunescu CN, Zeisel SH. Dietary choline deficiency alters global and gene-specific DNA methylation in the developing hippocampus of mouse fetal brains. FASEB J. 2006;20(1):43–49. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4707com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niculescu MD, Zeisel SH. Diet, methyl donors and DNA methylation: interactions between dietary folate, methionine and choline. The Journal of nutrition. 2002;132(8 Suppl):2333S–2335S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.8.2333S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resseguie ME, da Costa KA, Galanko JA, Patel M, Davis IJ, Zeisel SH. Aberrant estrogen regulation of PEMT results in choline deficiency-associated liver dysfunction. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286(2):1649–1658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.106922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley EP, Infante MA, Warren KR. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: an overview. Neuropsychology review. 2011;21(2):73–80. doi: 10.1007/s11065-011-9166-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rufer ES, Tran TD, Attridge MM, Andrzejewski ME, Flentke GR, Smith SM. Adequacy of maternal iron status protects against behavioral, neuroanatomical, and growth deficits in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. PloS one. 2012;7(10):e47499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruth RE, Goldsmith SK. Interaction between zinc deprivation and acute ethanol intoxication during pregnancy in rats. The Journal of nutrition. 1981;111(11):2034–2038. doi: 10.1093/jn/111.11.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan SH, Williams JK, Thomas JD. Choline supplementation attenuates learning deficits associated with neonatal alcohol exposure in the rat: effects of varying the timing of choline administration. Brain Res. 2008;1237:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.08.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg K, Sanberg PR, Coyle JT. Effects of intrastriatal injections of the cholinergic neurotoxin AF64A on spontaneous nocturnal locomotor behavior in the rat. Brain Res. 1984;299(2):339–343. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90715-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandstrom B. Micronutrient interactions: effects on absorption and bioavailability. The British journal of nutrition. 2001;85(Suppl 2):S181–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santillan ME, Vincenti LM, Martini AC, de Cuneo MF, Ruiz RD, Mangeaud A, Stutz G. Developmental and neurobehavioral effects of perinatal exposure to diets with different omega-6:omega-3 ratios in mice. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif. 2010;26(4):423–431. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider RD, Thomas JD. Adolescent Choline Supplementation Attenuates Working Memory Deficits in Rats Exposed to Alcohol During the Third Trimester Equivalent. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2016;40(4):897–905. doi: 10.1111/acer.13021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuch CP, Diaz R, Deckmann I, Rojas JJ, Deniz BF, Pereira LO. Early environmental enrichment affects neurobehavioral development and prevents brain damage in rats submitted to neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Neuroscience letters. 2016;617:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw GM, Carmichael SL, Laurent C, Rasmussen SA. Maternal nutrient intakes and risk of orofacial clefts. Epidemiology. 2006;17(3):285–291. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000208348.30012.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw GM, Carmichael SL, Yang W, Selvin S, Schaffer DM. Periconceptional dietary intake of choline and betaine and neural tube defects in offspring. American journal of epidemiology. 2004;160(2):102–109. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens KE, Adams CE, Mellott TJ, Robbins E, Kisley MA. Perinatal choline deficiency produces abnormal sensory inhibition in Sprague-Dawley rats. Brain Res. 2008a;1237:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens KE, Adams CE, Yonchek J, Hickel C, Danielson J, Kisley MA. Permanent improvement in deficient sensory inhibition in DBA/2 mice with increased perinatal choline. Psychopharmacology. 2008b;198(3):413–420. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromland K, Pinazo-Duran MD. Ophthalmic involvement in the fetal alcohol syndrome: clinical and animal model studies. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37(1):2–8. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syme MR, Paxton JW, Keelan JA. Drug transfer and metabolism by the human placenta. Clinical pharmacokinetics. 2004;43(8):487–514. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200443080-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JD, Abou EJ, Dominguez HD. Prenatal choline supplementation mitigates the adverse effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on development in rats. Neurotoxicology and teratology. 2009;31(5):303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JD, Biane JS, O’Bryan KA, O’Neill TM, Dominguez HD. Choline supplementation following third-trimester-equivalent alcohol exposure attenuates behavioral alterations in rats. Behavioral neuroscience. 2007;121(1):120–130. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JD, Garrison M, O’Neill TM. Perinatal choline supplementation attenuates behavioral alterations associated with neonatal alcohol exposure in rats. Neurotoxicology and teratology. 2004;26(1):35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JD, Idrus NM, Monk BR, Dominguez HD. Prenatal choline supplementation mitigates behavioral alterations associated with prenatal alcohol exposure in rats. Birth defects research. 2010;88(10):827–837. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JD, La Fiette MH, Quinn VR, Riley EP. Neonatal choline supplementation ameliorates the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on a discrimination learning task in rats. Neurotoxicology and teratology. 2000;22(5):703–711. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(00)00097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JD, Tran TD. Choline supplementation mitigates trace, but not delay, eyeblink conditioning deficits in rats exposed to alcohol during development. Hippocampus. 2012;22(3):619–630. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang TW, Lucas BR, Carmichael Olson H, Pinto RZ, Elliott EJ. Prenatal Alcohol Exposure, FASD, and Child Behavior: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):1–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner AF, Hunt PS. Impaired trace fear conditioning following neonatal ethanol: reversal by choline. Behavioral neuroscience. 2006;120(2):482–487. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.2.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainwright P, Fritz G. Effect of moderate prenatal ethanol exposure on postnatal brain and behavioral development in BALB/c mice. Experimental neurology. 1985;89(1):237–249. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(85)90279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Surzenko N, Friday WB, Zeisel SH. Maternal dietary intake of choline in mice regulates development of the cerebral cortex in the offspring. FASEB J. 2016;30(4):1566–1578. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-282426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J, D’Alquen G, Bezio S. Interactive effects of ethanol intake and maternal nutritional status on skeletal development of fetal rats. Alcohol (Fayetteville, N Y. 1990;7(5):383–388. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(90)90020-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werts RL, Van Calcar SC, Wargowski DS, Smith SM. Inappropriate feeding behaviors and dietary intakes in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder or probable prenatal alcohol exposure. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2014;38(3):871–878. doi: 10.1111/acer.12284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener SG, Shoemaker WJ, Koda LY, Bloom FE. Interaction of ethanol and nutrition during gestation: influence on maternal and offspring development in the rat. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 1981;216(3):572–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CL, Meck WH, Heyer DD, Loy R. Hypertrophy of basal forebrain neurons and enhanced visuospatial memory in perinatally choline-supplemented rats. Brain Res. 1998;794(2):225–238. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00229-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong-Goodrich SJ, Tognoni CM, Mellott TJ, Glenn MJ, Blusztajn JK, Williams CL. Prenatal choline deficiency does not enhance hippocampal vulnerability after kainic acid-induced seizures in adulthood. Brain Res. 2011;1413:84–97. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak JR, Fuglestad AJ, Eckerle JK, Fink BA, Hoecker HL, Boys CJ, Radke JP, Kroupina MG, Miller NC, Brearley AM, Zeisel SH, Georgieff MK. Choline supplementation in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2015;102(5):1113–1125. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.099168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen CL, Mar MH, Meeker RB, Fernandes A, Zeisel SH. Choline deficiency induces apoptosis in primary cultures of fetal neurons. FASEB J. 2001;15(10):1704–1710. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0800com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeisel SH. Choline: critical role during fetal development and dietary requirements in adults. Annual review of nutrition. 2006;26:229–250. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.26.061505.111156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeisel SH. Nutrition in pregnancy: the argument for including a source of choline. International journal of women’s health. 2013;5:193–199. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S36610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeisel SH, Da Costa KA, Franklin PD, Alexander EA, Lamont JT, Sheard NF, Beiser A. Choline, an essential nutrient for humans. FASEB J. 1991;5(7):2093–2098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeisel SH, Niculescu MD. Perinatal choline influences brain structure and function. Nutrition reviews. 2006;64(4):197–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2006.tb00202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou FC, Sari Y, Zhang JK, Goodlett CR, Li T. Prenatal alcohol exposure retards the migration and development of serotonin neurons in fetal C57BL mice. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2001;126(2):147–155. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(00)00144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]