Abstract

Despite efforts to prevent physical teen dating violence, it remains a major public health issue with multiple negative consequences. This study aims to investigate gender differences in the relationships between exposure to interparental violence (mother-to-father violence, father-to-mother violence), acceptance of dating violence (perpetrated by boys, perpetrated by girls), and self-efficacy to disclose teen dating violence. Data were drawn from Waves 1 and 2 of the Quebec Youth Romantic Relationships Project, conducted with a representative sample of Quebec high school students. Analyses were conducted on a subsample of 2,564 teenagers who had been in a dating relationship in the past 6 months (63.8% girls, mean age of 15.3 years). Path analyses were conducted to investigate the links among exposure to interparental violence, acceptance of violence, self-efficacy to disclose teen dating violence (measured at Wave 1), and physical teen dating violence (measured at Wave 2). General exposure to interparental violence was linked, through acceptance of girl-perpetrated violence, to victimization among both genders and to girls’ perpetration of physical teen dating violence. No significant difference was identified in the impact of the gender of the perpetrating parent when considering exposure to interparental violence. Self-efficacy to disclose personal experiences of violence was not linked to exposure to interparental violence or to experiences of physical teen dating violence. The findings support the intergenerational transmission of violence. Moreover, the findings underline the importance of targeting acceptance of violence, especially girlperpetrated violence, in prevention programs and of intervening with children and adolescents who have witnessed interparental violence.

Keywords: dating violence, children exposed to domestic violence, youth violence, violence exposure

Occurring at a crucial moment in psychosocial development, physical teen dating violence (TDV) can affect the well-being and future relationships of teenagers who perpetrate or are victims of this type of violence. Indeed, romantic relationships at this stage play a role in the development of close relationships, sense of intimacy, sexual health, sense of self or identity (e.g., self-esteem, gender-role identity) and could influence academic achievement (Furman & Shaffer, 2003). The presence of violence in these first romantic relationships might be detrimental to these crucial issues. A representative study in the province of Quebec showed that among teenagers who had a romantic partner in the past year, 13.3% of boys and 11.0% of girls were victims of physical TDV, while 5.6% of boys and 19.2% of girls were involved in the perpetration of at least one episode (Pica et al., 2013). A recent representative survey conducted in the same Canadian province showed that girls (15.8%) reported more victimization than boys (12.8%) of at least one episode of physical TDV in the past year (Hébert, Lavoie, & Blais, 2017). School dropout, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and suicidal ideations are possible consequences of physical TDV (Banyard & Cross, 2008; Hébert et al., 2016). A prior experience of physical TDV victimization is also linked with a higher risk of being a victim of this type of violence in a long-term perspective (Smith, White, & Holland, 2003).

The widespread prevalence and consequences of this phenomenon underscore the necessity to improve our knowledge of physical TDV and its risk factors to adapt prevention programs. Prior studies have identified factors associated with the occurrence of victimization and perpetration of physical TDV for both genders, such as exposure to interparental violence (EIPV) and attitudes toward TDV (Olsen, Parra, & Bennett, 2010; Vézina & Hébert, 2007). It has been suggested that other individual factors should be studied, such as dispositional characteristics, family background and interpersonal characteristics (Bartholomew & Cobb, 2010). For the present study, perception of self-efficacy to disclose violence will be considered in addition to EIPV and acceptance of violence as risk factors for victimization and perpetration of physical TDV.

Intergenerational transmission of violence has often been used to explain the influence of EIPV on the development of victimization and perpetration of physical TDV. According to social learning theory, a child’s behavior can be modeled through observations of figures significant to him or her (Bandura, 1977). Moreover, the child will be more influenced by a model that he or she perceives as important or powerful. Therefore, as caregivers, parents’ behaviors of violence toward each other could lead a child to believe that violence is a normal part of relationships and a way to solve conflicts. Thus, the child could grow up holding attitudes of acceptance of violence and be more likely to accept violence or to perpetrate it in his or her own romantic relationships. The associations of EIPV with physical TDV perpetration (e.g., Ali, Swahn, & Hamburger, 2011; Malik, Sorenson, & Aneshensel, 1997; Wolfe, Wekerle, Scott, Straatman, & Grasley, 2004) and physical TDV victimization (e.g., Choi & Temple, 2016; Karlsson, Temple, Weston, & Le, 2016; Malik et al., 1997) are empirically supported.

Although many studies have explored the general transmission of violence by EIPV (being exposed to interparental violence regardless of the gender of the perpetrating parent), few have explored a gender-related transmission of violence (witnessing mother-to-father violence and father-to-mother violence), and contradictory findings have been produced. Indeed, as during childhood, the mother is considered as the primary caregiver (Doherty & Feeney, 2004), her behaviors could have a greater influence on the child. Social learning cognitive theory also suggests that the perceived consequences of the actions witnessed will influence the child’s appraisal and future reproduction of a specific behavior. Thus, the child or adolescent will be more prone to reproduce the mother’s violent behavior if the outcomes seem less negative (Olsen et al., 2010). Indeed, due to the usual greater physical strength of the father, the consequences of the father-to-mother violence would be seen as more serious and visible. On the contrary, the mother-to-father violence consequences seen by the child could be resignation of the father rather than injuries (Olsen et al., 2010). Some studies have found that mother-to-father violence is a greater predictor of physical TDV than father-to-mother violence (Karlsson et al., 2016; Malik et al., 1997; Moretti, Obsuth, Odgers, & Reebye, 2006; Temple, Shorey, Fite, Stuart, & Le, 2013). However, the results of other studies contradict this finding (Gover, Kaukinen, & Fox, 2008; Kinsfogel & Grych, 2004).

Another factor that could influence the relationship between exposure to interparental violence and physical TDV is the gender of the adolescent. Indeed, some studies have reported links for teenage girls only between EIPV and physical TDV victimization (e.g., Maas, Fleming, Herrenkohl, & Catalano, 2010; Tschann et al., 2009) and physical TDV perpetration (e.g., Tschann et al., 2009). However, Chen and White (2004) noted an effect only for boys, while Lichter and McCloskey (2004) found no gender differences but failed to find a direct link between EIPV and TDV. Possible explanation for these discrepant findings is methodological differences regarding the population under study and the developmental period in which EIPV was assessed. Lichter and McCloskey (2004) measured EIPV with reports of mothers who experienced severe marital violence victimization in a low-income sample of adolescents, while Chen and White (2004) studied a sample of young adults and measured EIPV occurring during adolescence and not childhood. Although the relation between EIPV and physical TDV seems generally well established, many contradictions in the literature remain regarding the influence of the gender of the parent inflicting violence and the gender of the adolescent.

Attitudes of acceptance of violence are a target for modification in many prevention programs of physical TDV (Foshee et al., 1998). Studies have found that acceptance of violence is related to victimization (e.g., Karlsson et al., 2016; Reeves & Orpinas, 2012) and to perpetration of physical TDV (e.g., Foshee, Linder, MacDougall, & Bangdiwala, 2001; Reeves & Orpinas, 2012). However, differences between attitudes of acceptance of man to woman violence and woman to man violence have been noted. Violence inflicted by girls was found to be more approved by teenage boys and girls than violence inflicted by boys (e.g., Reeves & Orpinas, 2012). Robertson and Murachver (2009) documented that acceptance of boy-inflicted violence was linked to the perpetration and victimization of violence in college students of both genders, while Ali et al. (2011) found in an at-risk sample of teenagers that this relation was significant only for boys. Ali et al. (2011) also suggested that acceptance of girl-inflicted violence was related to girls’ perpetration of physical TDV and to both genders’ victimization. Our study will test these relationships in a representative sample of high school students, along with other risk factors associated with physical TDV.

Self-efficacy is a central mechanism in personal agency as it influences individuals’ mobilization, decisions and effort they exert in a specific situation (Bandura, 2001). Self-efficacy is an individuals’ belief in his or her own capacity to complete a behavior or to reach a goal (Bandura, 1997). Therefore, in a relationship where conflicts occur, if a partner feels unable to change the situation, he or she will be less prone to seek help and will be more at risk of episodes of victimization or violence perpetration. Indeed, Cameron et al. (2007) found that teenagers who perpetrated physical TDV felt less able to address violence than their non-violent peers. Moreover, girls generally felt more confident than boys to act or seek help if confronted with the perspective of experiencing physical TDV (Van Camp, Hébert, Guidi, Lavoie, & Blais, 2014). Bandura (1997) stated that self-efficacy is partly acquired from vicarious experience. Therefore, EIPV could influence the perception of self-efficacy to address violence. By seeing his or her parents unable to stop or to address violence, a child could develop feelings of hopelessness and inefficacy toward violence. Wolfe, Wekerle, Reitzel-Jaffe, and Lefebvre (1998) found that youth with past experiences of maltreatment, including EIPV, had a lower sense of self-efficacy to handle problematic social situations. The perception of self-efficacy regarding control and anger management have been found to account for intimate partner violence in adult couples. Young adults who believed they could control their anger were more successful in self-regulating their emotions and therefore less likely to perpetrate intimate partner violence (Nocentini, Pastorelli, & Menesini, 2013). These findings suggest a possible impact of the perception of self-efficacy among teenagers and highlight the relevance of integrating this variable in our analysis of risk factors for physical TDV.

The aim of our study is to investigate gender differences in the relationships among EIPV, acceptance of physical TDV, self-efficacy to disclose TDV and victimization and perpetration of physical TDV. Hypothesis 1 (H1): Acceptance of violence is a mediator of the relationship between EIPV and physical TDV victimization and perpetration. If this mediated relationship is found to be significant, the model will be explored regarding (H1a) the differences between mother-to-father violence and father-to-mother violence regarding acceptance of violence and physical TDV and (H1b) the differences between acceptance of girl-inflicted violence and acceptance of boy-inflicted violence in the relation between EIPV and physical TDV. Hypothesis 2 (H2): Higher EIPV is associated with a lower sense of self-efficacy to disclose physical TDV, which is linked to a higher level of physical TDV perpetration and victimization. Therefore, the perception of self-efficacy is a mediator of the relationship between EIPV and physical TDV. Gender differences will be tested on every variable and association between variables in the model. The control variables considered in our study include a past experience of physical TDV and parents’ level of education as a proxy for socioeconomic status.

Method

Participants

Data collected in the Quebec Youth’s Romantic Relationship Survey Project (QYRRS Project), a longitudinal self-reported survey, were used in our study. The data were collected through a one-stage stratified cluster sampling of 34 Quebec high schools randomly selected from the Ministry of Education provincial database. Eight stratums were created, considering the language of teaching (French/English), the education system (Private/Public), the geographical area and the underprivileged school index.

The data collected from the QYRRS were weighted to minimize partial non-response and to better represent the population. The original sample included 8,194 teenagers from 329 classes of 34 schools in the province of Quebec. At wave 2, the sample included 6,472 teenagers. All analyses were performed taking into account the complex sampling design and sampling weights to ensure representativeness. The weighted sample was 6,540 youths.

For our study, the data from waves 1 and 2 of the QYRRS were used. Wave 1 occurred in autumn 2011, and wave 2 took place six months later. Participants who were not in a relationship in the past 6 months (3,175/6,540), were 18 years old or older at wave 1 (105/6,540; 39/3,175) and were attracted only to members of the same sex (107/6,540; 52/3,136) were excluded1. Then, the 520 participants who did not answer at both waves were excluded from the study. The final sample of our study included 2,564 adolescents (63.8% girls) with a mean age of 15.29 years (SE= 0.10; range= 14–17). The majority of our sample (58.4%) lived with both parents. The ethnicity of the parents of most participants (82.8%) was native-born Quebecer/Canadian. The majority of the sample reported that their parents’ level of education was college/professional training or higher (67.3% for mothers; 58.6% for fathers). The primary language spoken at home for most participants was French (92.5%). Since the age of 12 (excluding the past year), 6.2% of girls (M = 0.06, SE = 0.24) and 2.9% of boys (M = 0.03, SE = 1.7) reported at least one episode of perpetration, while 13.6% of girls (M = 0.14, SE = 0.34) and 3.7% of boys (M = 0.04, SE = 0.19) reported at least one experience of victimization. Some authors have highlighted the impact of cultural differences, even between American states, mostly related to gender’s roles and social status on the prevalence and perception of intimate violence (Vandello & Cohen, 2003). The data used in our study were drawn from a representative sample of the province of Quebec high school students. Therefore, results such as the TDV rates and attitudes toward violence must be interpreted in light of cultural differences. The main characteristics as expected in a representative Quebec sample were its homogeneity regarding the language spoken at home and parents’ country of origin and education level, which might differ from areas with more diversity. Many studies similar to ours have been conducted with American samples.

Measures

All predictive variables and sociodemographic information were assessed at Wave 1. Physical TDV victimization and perpetration were measured at Wave 2.

Sociodemographic information

Information regarding sex, age, family structure, language most spoken at home, ethnicity, sexual orientation and parents’ education level was collected.

Physical TDV

Youth who reported a relationship in the past 6 months completed the TDV questionnaire. Three items from the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory (CADRI short version; Wekerle et al.,2009; that is “slapped or pulled the other’s hair”; “kicked, hit or punched the other”; “pushed, shoved, shook, or pinned down the other”) were adapted from the original questionnaire to measure physical TDV in the past six months. These items referred specifically to acts occurring during a conflict with a romantic partner. The four-point response scale ranged from 0 (never) to 3 (6 times or more). The total score on the items was used to create a scale of victimization (α = .66) and of perpetration (α = .71) of physical TDV. A higher score on these scales indicates a higher frequency of physical TDV.

Past experience of physical TDV

One item inspired by the CADRI (Wekerle et al., 2009) was used to assess past experiences of physical TDV since the age of 12 (excluding the past 12 months). Participants were asked whether a boyfriend or girlfriend had behaved in the following way towards them: “Pushed, shoved, shook, or pinned down the other”. This item was modified to assess perpetration of physical violence. The response range was dichotomous (i.e., “yes” or “no”). The scores for perpetration and victimization were meant to be used as control variables.

EIPV

Four items from the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2: Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) were adapted to measure the frequency of exposure to interparental psychological and physical violence (i.e., “insult, swear, shout, yell”; “threaten to hit or destroy the other person’s belonging”; “push, shove, slap, twist the arm, throw something at the other person that could hurt”; “threaten with a knife or a weapon, punch or kick, slam the person against a wall”). Participants had to answer, for each item: “In my lifetime, I’ve seen my father do this to my mother” and “In my lifetime, I’ve seen my mother do this to my father”. Parents refer to the parental figure for the participant (e.g., stepfather, grandparent). The four-point response scale ranged from 0 (never) to 3 (11 times or more). A total score was computed for the three scales, a general EIVP scale (α = .80), a mother-to-father EIVP scale (α = .72) and a father-to-mother EIVP scale (α = .64). A higher score indicates a greater EIPV on each scale.

Self-efficacy to disclose personal violence

Two items from the Self-efficacy to Deal With Violence Scale (Cameron et al., 2007) were used to assess participants’ perceived self-efficacy to disclose violence (e.g., “[…] How confident are you that you could tell someone you trust that you are being abused by [or “you are abusing”] your boyfriend/girlfriend?”). Item responses ranged from 1 (not at all confident) to 4 (very confident). A total score on self-efficacy was computed. There was a moderate correlation of .51 between the items. A higher score indicates that participants feel more confident in their ability to disclose TDV as a victim or a perpetrator.

Acceptance of teen dating violence

Four original items from the Acceptance of Prescribed Norms Scale (Foshee et al., 2001) and two items adapted from this scale were used to measure acceptance of teen dating violence. Three of these items assessed acceptance of physical TDV perpetrated by boys, and three items assessed acceptance of physical TDV perpetrated by girls (e.g., “Boys sometimes deserve to be hit by their girlfriend; Girls sometimes deserve to be hit by their boyfriend”). Item responses ranged from 0 (strongly disagree) to 3 (strongly agree). Total scores were used to compute a scale of acceptance of physical TDV in general (α = .73), a scale of acceptance of physical TDV perpetrated by boys (α = .72) and a scale of acceptance of physical TDV perpetrated by girls (α = .73). A higher score on each of these scales indicates a greater acceptance of TDV.

Procedures

The approval of each school director was obtained for the project. Participants agreed to participate on a voluntary basis by signing an informed consent form and were provided a list of resources. The overall response rate was 99% of students present in class, and the retention rate between the two waves was 71%. The research ethics boards of the Université du Québec à Montréal approved the QYRRS Survey project.

Statistical Analyses

Step 1: Preliminary analyses

Mplus version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012) was used for the path analysis, and the other statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22. Overall, the non-response rates for the variables included in the subsample used (n = 2,564) ranged from .3% to 5.9%. Approximately 5% of the data were missing in our studied sample, a rate at which biases and losses of power are unlikely or non-significant (Graham, 2009). Further analysis showed no specific pattern of non-response in the missing data. The missing data were addressed using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) to estimate the model parameters when considering all raw data available (Wothke, 2000). Correlation analyses were conducted to explore the relationships among variables. Variables of physical TDV, EIPV and acceptance of violence were transformed with winsorization followed by logarithmic transformation because of their non-normal distributions (Hellerstein, 2008; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013).

Step 2: Process analysis to test moderation and mediation links

Mediation and moderation analyses were conducted following the approach put forward by Preacher, Rucker, and Hayes (2007) to clarify the relationships between TDV and the three predictive variables and the influence of gender on the model. As general EIPV was linked to physical TDV through acceptance of violence (H1), the effects of EIPV inflicted by parents of a specific gender (mother-to-father violence; father-to-mother violence) in the model were tested. As general acceptance of violence was linked to EIPV and physical TDV, the model was also tested regarding specific acceptance of girl-inflicted violence and boy-inflicted violence (H1b). Regarding H2, the indirect relationship between EIPV and physical TDV through self-efficacy was tested. However, as EIPV and self-efficacy were not linked, self-efficacy was retained as an independent predictor of physical TDV. Post-hoc analyses of the association between self-efficacy and acceptance of violence (general; girl-inflicted violence; boy-inflicted violence) were also conducted.

Step 3: Path analysis

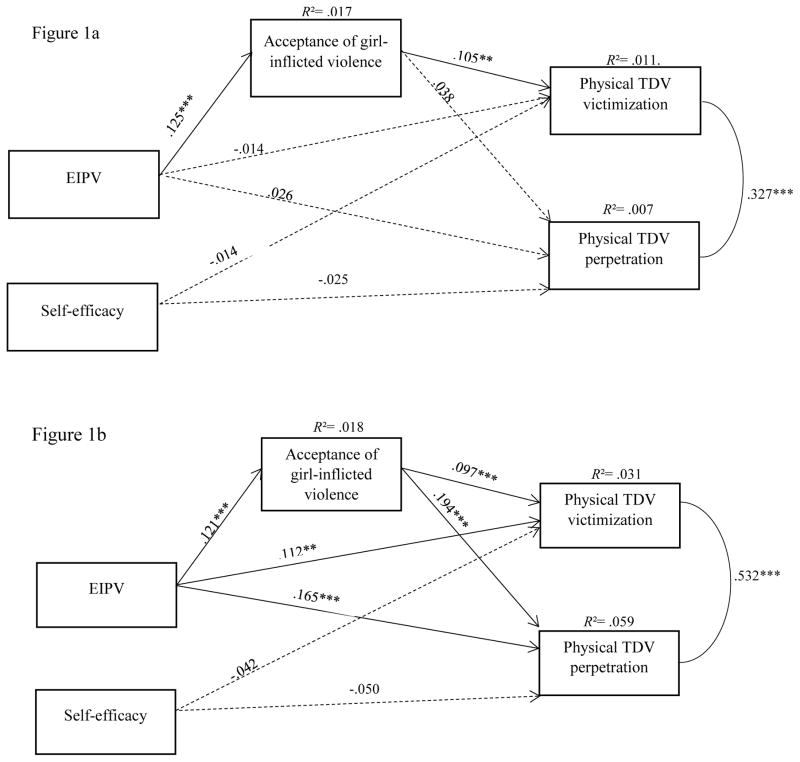

First, the indirect effects in the path models (figure 1a, figure 1b) were estimated using FIML, in which all data available to estimate parameters are used. The models were tested with ML estimation using robust standard errors. The significance of indirect effects in the path models were tested using 1000 bootstrap samples and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs).

Figure 1.

Fig 1a. Model 1: best-fitting model from the path analysis for boys. Note. EIPV= Exposure to interparental violence; TDV= Teen dating violence. Significant paths are represented by solid lines.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001

Fig 1b. Model 2: best-fitting model from the path analysis for girls. Note. EIPV= Exposure to interparental violence; TDV= Teen dating violence. Significant paths are represented by solid lines.

* p < .05. ** p <. 01. *** p < .001

We performed three separated path analyses using the three different scales of EIPV as independent variables (general; mother-to-father; father-to-mother) to predict victimization and perpetration of physical TDV through acceptance of violence and self-efficacy. As the relationships between the variables were the same in the three models and the models had a similar fit, only the model of general EIPV was kept, for the sake of parsimony. The correlations demonstrated significant gender differences between the variables used in the model (see table 2). Therefore, one model was computed for boys (model 1, see fig. 1a) and one for girls (model 2, see fig. 1b).

Table 2.

Means, Standard Error, and Bivariate Correlations between all Variables and Gender (N = 2,564)

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | M | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. EIPV | - | .90** | .93** | .11** | .10* | .08* | −.02 | .07 | .02 | 2.41 | 3.21 |

| 2. EIPV mother-to- father | .89** | - | .68** | .12** | .13** | .05 | −.02 | .06 | .015 | 1.10 | 1.64 |

| 3. EIPV father-to- mother | .92** | .64** | - | .08* | .05 | .09* | −.02 | .06 | .02 | 1.30 | 1.86 |

| 4. Acceptance of general violence | .10** | .10** | .08** | - | .91** | .65** | −.07 | 0.5 | .09* | 3.14 | 3.17 |

| 5. Acceptance of girl violence | .11** | .11** | .09** | .94** | - | .29** | −.05 | .04 | .10** | 2.55 | 2.51 |

| 6. Acceptance of boy violence | .05 | .04 | .04 | .73*** | .44** | - | −.07 | .04 | .02 | 0.58 | 1.35 |

| 7. Self-efficacy | −.04 | −.01 | −.05 | −.04* | −.03 | −.05 | - | −.05 | −.02 | 5.31 | 1.92 |

| 8. Physical TDV perpetration W2 | .16** | .14** | .15** | .17** | .19** | .05 | −.06 | - | .53** | 0.10 | .54 |

| 9. Physical TDV victimization W2 | .12** | .08** | .13** | .08** | .09** | .03 | −.05 | .58** | - | 0.33 | 1.00 |

| M | 3.07 | 1.41 | 1.67 | 2.50 | 2.02 | .48 | 5.83 | 0.31 | 0.25 | - | - |

| SE | 3.65 | 1.89 | 2.16 | 2.97 | 2.28 | 1.16 | 1.70 | 0.89 | 0.77 | - | - |

| Range | 0–24 | 0–12 | 0–12 | 0–18 | 0–9 | 0–9 | 2–8 | 0–9 | 0–9 | - | - |

Note. TDV= teen dating Violence; EIPV =Exposure to Interparental Violence; W2= Wave 2. Bivariate correlations used in a complex sample design, due to its rational and representativeness, do not provide results of standard deviations, but only of standard error. The results below the diagonal are for girls, while the results over the diagonal are for boys.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows the prevalence rates and chi-square results of gender differences in the variables of our study. Among participants engaged in a dating relationship in the past six months, there were no significant gender differences regarding physical TDV victimization; 14.0% of girls and 15.2% of boys reported at least some (≥1 item) physical TDV victimization. Moreover, girls (16.9%) were significantly more likely to report perpetration than boys (5.5%). In the final sample, 64.1% of participants reported acceptance of girl-inflicted violence (any response other than “totally disagree” to any item), and 25.1% reported acceptance of boy-inflicted violence. Two thirds of participants were exposed to general EIPV. Table 2 reports the means, SE, range and bivariate correlations between the variables for each gender. General EIPV was significantly associated with elevations in physical TDV victimization (r = .12, p < .01) and perpetration (r = .16, p <.01) only for girls. EIPV was not linked to self-efficacy.

Table 1.

Gender Differences in the Prevalence of Predictive Variables Dichotomized

| Measure | Girls | Boys | χ2 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | |||

| Physical TDV victimization W2 | No | 86.0 | 84.8 | .69 | 85.6 |

| Yes | 14.0 | 15.2 | 14.4 | ||

| Physical TDV perpetration W2 | No | 83.1 | 94.5*** | 67.98*** | 87.3 |

| Yes | 16.9*** | 5.5 | 12.7 | ||

| Acceptance of general violence | No | 37.4* | 32.2 | 6.83* | 35.5 |

| Yes | 62.6 | 67.8* | 64.5 | ||

| Acceptance of girl violence | No | 37.6* | 33.0 | 5.34* | 35.9 |

| Yes | 62.4 | 67.0* | 64.1 | ||

| Acceptance of boy violence | No | 75.5 | 73.8 | .92 | 74.9 |

| Yes | 24.5 | 26.2 | 25.1 | ||

| General EIPV | No | 33.5 | 44.2*** | 27.06*** | 37.3 |

| Yes | 66.5*** | 55.8 | 62.7 | ||

| EIPV mother-to- father violence | No | 40.6 | 51.9*** | 28.61** | 44.5 |

| Yes | 59.4*** | 48.1 | 55.5 | ||

| EIPV father-to- mother violence | No | 38.0 | 46.8** | 17.87** | 41.1 |

| Yes | 62.0** | 53.2 | 58.9 | ||

| Self-Efficacy | No | 4.3 | 11.9*** | 51.26*** | 7.1 |

| Yes | 95.7*** | 88.1 | 92.9 |

Note. TDV= teen dating Violence; EIPV =Exposure to Interparental Violence; W2= Wave 2. This table shows the prevalence of any episodes of physical TDV, acceptance of teen dating violence (other than “strongly disagree” on any item), any exposure to interparental violence and any self-efficacy to disclose violence (other than “ not at all confident”). The total scores of those variables were dichotomized for this table.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < 0.001

Path Analysis

The models (see Figure 1a for Model 1 and Figure 1b for Model 2) provided a good fit to the data: comparative fit index (CFI) = 1.000, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .000, χ2 (1) = .005, p = .943 for model 1; CFI = 0.997, RMSEA = .033, χ2 (1) = 2.684, p = .101 for model 2. Indeed, an RMSEA value of .05 or less represents models with a good fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993). A CFI score higher than .90 represents a model with a good fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993), and non-significant chi-square values indicate a good fit to the data (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Only acceptance of girl-inflicted violence was significant in the models; therefore, the variable of acceptance of boy-inflicted violence is not shown. For girls, general EIPV was directly associated with an increased experience of physical TDV victimization (fig. 1b: β = .112, p < .001) and physical TDV perpetration (fig. 1b: β = .165, p < .001). There was no significant direct association of EIPV with physical TDV victimization or with perpetration for boys (see fig. 1a). For boys, acceptance of girl-inflicted violence was a mediator of the relationships between EIPV and physical TDV victimization (model 1: IE = 0.013, 95% CI [.005, .025]), while there was an indirect effect of EIPV on physical TDV victimization for girls through acceptance of girl-inflicted violence (model 2: IE = 0.012, 95% CI [.007, .019]). There was an indirect effect of EIPV on physical TDV perpetration via acceptance of girl-inflicted violence for girls (model 2: IE = 0.024, 95% CI [.015, .033]). This relationship was not significant for boys (model 1: IE = 0.005, 95% CI [.000, .012]). There were no significant associations between self-efficacy and physical TDV for either gender.

Control variables considered in the model included the mother’s level of education and past experiences of victimization and perpetration of physical TDV at Wave 1. As these variables were not significant in the models, they were not included and therefore not shown in the results or figures. Indeed, they added little to the general fit of the models and had low correlations (range between r = .085 and r = .133; R2 = .003 for girls and R2 = .001 for boys (past victimization); R2 = .004 for girls and R2 = .006 for boys (past perpetration)) with physical TDV at wave 2.

Post Hoc Analysis

The analysis revealed a non-hypothesized link between acceptance of violence and self-efficacy to disclose violence. To clarify the model, the relationships between self-efficacy and acceptance of violence (general; girl-inflicted violence; boy-inflicted violence) were tested in the post-hoc path analysis for both genders. The addition of the post hoc link between self-efficacy and acceptance of violence was justified as the chi-square difference between the model with and the model without this parameter was significant. The addition of the post hoc link also slightly improved the measures of goodness of fit. The only significant relationship was between self-efficacy and acceptance of violence in general, only for girls (β = −.064, p <.05). Therefore, acceptance of violence in general was a mediator for the relationship between self-efficacy and physical TDV victimization (IE = −0.006, 95% CI [−.012, −.001]) and perpetration (IE = −0.012, 95% CI [−.021, −.001]) for girls. A lower perception of self-efficacy to disclose violence was linked to higher acceptance of TDV in general, which was related to victimization and perpetration experience of physical TDV for girls. The model, not illustrated, provided a good fit to the data (CFI = .997, RMSEA = .033, p = .10, χ2 (1) = 2.706, p = .100).

Discussion

The aim of our study was to explore gender differences in the relationships among EIPV, gender-specific acceptance of violence, self-efficacy to disclose personal violence, and physical TDV victimization and perpetration. Overall, it confirmed the importance of EIPV and acceptance of violence. Four main findings emerged from this study. First, there were gender differences in the models, as only boys’ victimization was significantly accounted for by some predictors, whereas both victimization and perpetration of physical TDV were significantly predicted for girls. Second, there was no distinct effect of exposure to mother-to-father or father-to-mother violence on the models (H1.1). Third, only acceptance of girl-inflicted violence was predictive of physical TDV among the models (H1.2). Fourth, there was no link between EIPV and self-efficacy or between self-efficacy and physical TDV for either gender (H2). Finally, the risk factors explained only a small part of the variance of physical TDV. However, studies with similar variables also reported low to moderate effect sizes (Karlsson et al., 2016; Temple, Shorey, Tortolero, Wolfe, & Stuart, 2013), showing that physical TDV is a complex phenomenon with many possible factors associated to it. Moreover, teenagers exposed to interparental violence are not destined to reproduce violent behaviors.

As hypothesized (H1), teenagers more highly exposed to interparental violence were more likely to accept violence in dating relationships, which increased their risk of experiencing physical TDV. However, this relationship was significant only for acceptance of girl-inflicted violence. This supports the intergenerational transmission of violence through the social learning theory of Bandura, implying that children learn from a model’s behaviors and are more prone to repeat or tolerate violence afterward. However, EIPV and acceptance of girl-inflicted violence predicted victimization and perpetration for girls, while it only predicted boys’ victimization. For girls, EIPV predicted experience of physical TDV both directly and indirectly through acceptance of violence, suggesting that girls who witness interparental violence are more likely to be victims or perpetrators of physical TDV because of their greater acceptance of girl-inflicted violence. On the contrary, for boys, acceptance of girl-inflicted violence was a mediator of the relationship between EIPV and physical TDV victimization. Therefore, boys who reported acceptance of TDV were more at risk of being victims, while boys who had a past experience of EIPV but reported no acceptance of TDV were not more likely to experience TDV. Foshee, Bauman, and Linder (1999) and Gage (2016) also found that general EIPV, through the mediation of acceptance of violence, was a better predictor of girls’ perpetration than boys’ perpetration. However, Gage (2016) measured exposure to violence inflicted by a man or woman of the family toward a partner and the outcome was a combination of sexual and physical TDV. Other studies partly supported these findings, concluding that EIPV was directly related to victimization and perpetration of physical TDV only for girls (e.g., Maas et al., 2010; Tschann et al., 2009).

For both genders, victimization predicted by EIPV through acceptance of girl-inflicted violence could be a result of a learned minimization of violence, implying that it is a proper and non-dangerous way for girls in particular to handle conflicts. Furthermore, girls could have fewer social barriers than boys to respond physically to an argument with a dating partner, which could explain their perpetration of physical TDV. Moreover, girls with past EIPV could have had less opportunity to learn constructive ways to address conflict, which could increase violence escalation in their relationship and lead to victimization, as well as aggression. Boys with past EIPV who are more accepting of girl-inflicted violence could also normalize the expression of anger by girls through physical violence but not by boys.

A second finding was the absence of significant differences between witnessing mother-to-father and father-to-mother violence in the prediction of both genders’ experiences of physical TDV (H1.1). Our findings reveal that witnessing violence perpetrated by a parental figure, regardless of their gender, could shape the attitudes toward violence of children exposed to it and their future experience of physical TDV; this finding supports previous findings with adult couples (MacEwen, 1994). However, most studies with teenagers reported significant differences between exposure to mother-to-father and to father-to-mother violence (e.g., Karlsson et al., 2016; Malik et al., 1997). A possible explanation for these divergent findings could be that the low levels of EIPV reported in our study were insufficient to show gender differences of the perpetrating parent in EIPV (M = 3.07/24 for general EIPV). A better understanding of the inconsistencies in the literature regarding the effect of the gender of the perpetrating parent may lie in the child’s appraisal of violence and its consequences, which are usually not assessed in studies regarding the influence of EIPV on physical TDV (Fosco, DeBoard, & Grych, 2007; Olsen et al., 2010). Indeed, Olsen et al. (2010) noted the need to assess the role of consequences observed by children witnessing interparental violence as these affect their understanding of the situation and their emotional and behavioral responses (Fosco et al., 2007). We contributed to such efforts by studying EIPV to both physical and psychological violence. Studied separately or together, the conclusions were the same.

In our models, only acceptance of girl-inflicted violence predicted physical TDV (H1.2). Therefore, the more acceptance of girl-inflicted violence teenagers reported, the more likely they were to experience physical TDV. Previous studies reported that acceptance of girl-inflicted violence was a more consistent predictor of physical TDV victimization (Karlsson et al., 2016) and perpetration (Josephson & Proulx, 2008) than acceptance of boy-inflicted violence. However, some studies found a greater influence of acceptance of boy-perpetrated violence on TDV (O’Keefe & Treister, 1998; Robertson & Murachver, 2009) or mixed results (Ali et al., 2011). The fact that our study included a general population of students could partly explain those differences. In at-risk sample, where participants may come from a background with greater violence, acceptance of violence could be stronger and acceptance of boy-inflicted violence might be present. While most participants in our sample did not accept dating violence, violence perpetrated by girls was more accepted than that inflicted by boys. Moreover, boys could be more reluctant to disclose acceptance of boy-inflicted violence because of potential social sanctions and social desirability bias, and for them, tolerating violence could only be expressed through acceptance of girl-inflicted violence.

The hypothesis that a higher EIPV would be associated with a lower sense of self-efficacy, which would predict a higher experience of physical TDV, was invalidated (H2). In fact, perception of self-efficacy was linked to neither EIPV nor physical TDV. Therefore, one’s belief of being able to seek help from a trusted person when experiencing violence was not influenced by EIPV and did not predict TDV. This suggests that children who have witnessed interparental violence do not necessarily develop a lower or higher sense of self-efficacy to disclose their experiences of violence than children not exposed to it and that other factors would be implied. However, our findings contradict previous studies that found a link between EIPV, measured in an inclusive maltreatment variable, and self-efficacy to cope with difficult relationship issues, including physical TDV (Wolfe et al., 1998; Wolfe et al., 2004). Moreover, Cameron et al. (2007) found that perpetrators of TDV felt less confident to address violence, but Van Camp et al. (2014) found no significant link between self-efficacy and victimization of TDV. The reliance on only two items to measure self-efficacy in our study, which focused only on help-seeking behaviors, could explain our result. Bandura postulated that self-efficacy is domain specific (Bandura, 2001). Therefore, a measure of self-efficacy to handle conflicts or emotional self-regulation might offer a better prediction of TDV. Finally, teenagers reported feeling moderately confident (“somewhat confident”) in disclosing TDV.

We chose to explore the relationship between self-efficacy and acceptance of violence, a link that was not hypothesized. Post hoc analyses showed that only for girls, a lower sense of self-efficacy was linked to a greater acceptance of violence in general (with no sex-specific perpetrated violence attitudes) and physical TDV victimization and perpetration. This would imply that girls who felt as if they could not get help if they were victims or perpetrators of violence would report more acceptance of violence and thus be more at risk of TDV. An alternative explanation would be that if girls approved violence or saw it as a way to assert themselves, they might not see the need to disclose it or address it. More longitudinal studies are necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

Our study offers support to the integration of modifiable risk factors, such as attitudes of acceptance of violence, in prevention programs for teenagers. Group education, social norm marketing or media campaigns in community-based programs could help change acceptance of violence (Lundgren & Amin, 2015). The results show the importance of targeting in particular the acceptance of physical violence perpetrated by girls, as it is more largely accepted, while not overlooking violence perpetrated by boys. Our study also indicates the need to intervene with youth with experience of EIPV, who would benefit from psychological interventions to increase their social and emotional skills (Lundgren & Amin, 2015) and revise their acceptance of physical TDV. Although more studies are needed to clarify the impact of self-efficacy on physical TDV, the descriptive results from our study suggest that adolescents feel only moderately confident in seeking help if they were in a violent relationship. This underlines the importance of improving teenagers’ confidence to act if they experience physical TDV.

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the data were collected in a self-reported, retrospective questionnaire, which may include biases, such as underreporting. Second, the sample is representative of Quebec high school students and fails to include youth who might be at a greater risk of experiencing physical TDV, such as school dropouts. Third, the measures of EIPV used did not consider the persistence or reciprocity that participants witnessed between their parents or the timing of this exposure in the participants’ development. Moreover, interparental violence can be private and the children exposed to it might not perceive the severity or the direction of this violence. Also, it is possible that participants were exposed to violence in a prior relationship of a parent, but only reported the violence in their parents’ current relationship. Fourth, the model did not include sexual or psychological dating violence. Physical TDV is a complex phenomenon. The low percentages of variance explained in our study suggest that including a broader range of factors, such as affiliation with violent peers, harsh parenting and exposure to violence in the neighborhood (Brooks-Russell, Foshee, & Reyes, 2015), could provide a more realistic model for physical TDV. Future studies should also explore the situation in non-heterosexual relationships and consider how acceptance of dating violence is associated with other norms, such as traditional gender role attitudes and beliefs of a high prevalence of dating violence, as suggested by Reyes, Foshee, Niolon, Reidy, and Hall (2016). It should be noted that the data used in their study dated from 20 years. Other mediators of EIPV could also be verified in future studies, such as hopelessness and coping strategies.

Nevertheless, our study was based on a representative sample of Quebec high school students aged 14 to 17 years, including teenagers from rural and urban areas. Victimization and perpetration of physical TDV for each gender were both taken into account in a design with two measure points. This research also adds to the findings on the influence of the gender of the perpetrating parent in EIPV and sex-specific attitudes of acceptance of violence. The models were analyzed based on continuous data rather than dichotomous responses, which allows a better comprehension of youths’ reported behaviors (Streiner, 2002). Moreover, this study is, to our knowledge, the first to test such variables among a francophone North American population.

Acknowledgments

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR; No. 103944) awarded to Martine Hébert. The first author received a student scholarship by the research group Équipe FQR-SC Violence Sexuelle et Santé (ÉVISSA) and The Interdisciplinary Research Centre on Intimate Relationship Problems and Sexual Abuse (CRIPCAS).

Biographies

Catherine Ruel is a doctoral candidate in the clinical psychology program at University Laval, Québec. Her research interests are in interpersonal violence.

Francine Lavoie, PhD, is a professor in community psychology at Université Laval, Québec. Over the years, she has received grants on marital violence, dating violence, and mutual aid groups. She has also developed and evaluated two prevention programs on dating violence (ViRAJ and PASSAJ) for high school students. Her more recent work was on violence in Nunavik and on sexualized social activities in adolescence. She is a fellow of the Society for Community Research and Action (American Psychological Association).

Martine Hébert is the Canada research chair in interpersonal traumas and resilience and a full professor in the Department of Sexology at UQAM. Her research explores the diversity of profiles in interpersonal trauma survivors as well as personal and familial factors influencing outcomes. She has also conducted several evaluative studies of violence prevention and intervention programs in collaboration with partnership from different settings. Her current research documents trajectories of revictimization and pathways to resilient outcomes in children and teenagers who experienced interpersonal traumas using a longitudinal design and a person-oriented approach.

Martin Blais, PhD (sociology), is a full professor in the sexology department of the Université du Québec à Montréal and a regular member of the Interdisciplinary Research Centre on Intimate Relationship Problems and Sexual Abuse. His research interests are the development of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transidentified persons; exposure to social biases, such as heterocisnormativity, and their impacts on psychosocial development; sexual diversity; sexual health; intimate relationships; and the sociology of sexuality and intimacy.

References

- Ali B, Swahn M, Hamburger M. Attitudes affecting physical dating violence perpetration and victimization: Findings from adolescents in a high-risk urban community. Violence and Victims. 2011;26:669–683. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.26.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL, Cross C. Consequences of teen dating violence: Understanding intervening variables in ecological context. Violence Against Women. 2008;14:998–1013. doi: 10.1177/1077801208322058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K, Cobb RJ. Conceptualizing relationship violence as a dyadic process. In: Horowitz LM, Strack S, editors. Handbook of interpersonal psychology: Theory, research, assessment, and therapeutic interventions. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2010. pp. 233–248. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Russell A, Foshee VA, Reyes HLM. Dating violence. In: Gullotta TP, Plant RW, Evans M, editors. Handbook of adolescent behavioral problems: Evidence-based approaches to prevention and treatment. New York, NY: Springer US; 2015. pp. 559–576. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equations models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron CA, Byers ES, Miller SA, McKay SL, St Pierre M, Glenn S the Provincial Strategy Team for Dating Violence Prevention. Dating violence prevention in New Brunswick. Frederiction, NB: Muriel McQueen Fergusson Centre for Family Violence Research; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chen PH, White HR. Gender differences in adolescent and young adult predictors of later intimate partner violence: A prospective study. Violence Against Women. 2004;10:1283–1301. doi: 10.1177/1077801204269000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HJ, Temple JR. Do gender and exposure to interparental violence moderate the stability of teen dating violence?: Latent transition analysis. Prevention Science. 2016;17:367–376. doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0621-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty NA, Feeney JA. The composition of attachment networks throughout the adult years. Personal Relationships. 2004;11:469–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00093.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fosco GM, DeBoard RL, Grych JH. Making sense of family violence: Implication of children’s appraisals of interparental aggression for their short- and long-term functioning. European Psychologist. 2007;12:6–16. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040.12.1.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Arriaga XB, Helms RW, Koch GG, Linder GF. An evaluation of Safe Dates, an adolescent dating violence prevention program. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:45–50. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.88.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Linder GF. Family violence and the perpetration of adolescent dating violence: Examining social learning and social control processes. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:331–342. doi: 10.2307/353752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Linder F, MacDougall JE, Bangdiwala S. Gender differences in the longitudinal predictors of adolescent dating violence. Preventive Medicine. 2001;32:128–141. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Shaffer L. The role of romantic relationships in adolescent development. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2003. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gage AJ. Exposure to spousal violence in the family, attitudes and dating violence perpetration among high school students in Port-au-Prince. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2016;31:2445–2474. doi: 10.1177/0886260515576971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gover AR, Kaukinen C, Fox KA. The relationship between violence in the family of origin and dating violence among college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:1667–1693. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hébert M, Lavoie F, Blais M. Teen dating victimization: Prevalence and impact among a representative sample of high school students in Quebec, Canada. 2017. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellerstein JM. Quantitative data cleaning for large databases. United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE); 2008. Retrieved from http://db.cs.berkeley.edu/jmh. [Google Scholar]

- Josephson WL, Proulx JB. Violence in young adolescents’ relationships: A path model. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:189–208. doi: 10.1177/0886260507309340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson ME, Temple JR, Weston R, Le VD. Witnessing interparental violence and acceptance of dating violence as predictors for teen dating victimization. Violence Against Women. 2016;22:625–646. doi: 10.1177/1077801215605920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsfogel KM, Grych JH. Interparental conflict and adolescent dating relationships: Integrating cognitive, emotional, and peer influences. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:505–515. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter EL, McCloskey LA. The effects of childhood exposure to marital violence on adolescent gender-role beliefs and dating violence. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28:344–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00151.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren R, Amin A. Addressing intimate partner violence and sexual violence among adolescents: Emerging evidence of effectiveness. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015;56:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas CD, Fleming CB, Herrenkohl TI, Catalano RF. Childhood predictors of teen dating violence victimization. Violence and Victims. 2010;25:131–149. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.2.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacEwen KE. Refining the intergenerational transmission hypothesis. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1994;9:350–365. [Google Scholar]

- Malik S, Sorenson SB, Aneshensel CS. Community and dating violence among adolescents: Perpetration and victimization. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1997;21:291–302. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti MM, Obsuth I, Odgers CL, Reebye P. Exposure to maternal vs. paternal partner violence, PTSD, and aggression in adolescent girls and boys. Aggressive Behavior. 2006;32:385–395. doi: 10.1002/ab.20137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nocentini A, Pastorelli C, Menesini E. Self-efficacy in anger management and dating aggression in Italian young adults. International Journal of Conflict and Violence. 2013;7:274–2. R85. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe M, Treister L. Victims of dating violence among high school students: Are the predictors different for males and females? Violence Against Women. 1998;4:195–223. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen JP, Parra GR, Bennett SA. Predicting violence in romantic relationships during adolescence and emerging adulthood: A critical review of the mechanisms by which familial and peer influences operate. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:411–422. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.002. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pica LA, Traoré I, Camirand HF, Laprise P, Bernèche F, Berthelot M, … Plante N. L’Enquête québécoise sur la santé des jeunes du secondaire 2010–2011, Tome 2 [The 2010–2011 health survey of high school students, Volume 2] Québec, Qc: Institut de la statistique du Québec; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007;42:185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves PM, Orpinas P. Dating norms and dating violence among ninth graders in Northeast Georgia: Reports from student surveys and focus groups. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2012;27:1677–1698. doi: 10.1177/0886260511430386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes HLM, Foshee VA, Niolon PH, Reidy DE, Hall JE. Gender role attitudes and male adolescent dating violence perpetration: Normative beliefs as moderators. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2016;45:350–360. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0278-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson K, Murachver T. Attitudes and attributions associated with female and male partner violence. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2009;39:1481–1512. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2009.00492.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, White JW, Holland LJ. A longitudinal perspective on dating violence among adolescent and college-age women. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:1104–1109. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.7.1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Streiner DL. Breaking up is hard to do: The heartbreak of dichotomizing continuous data. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;47:262–266. doi: 10.1177/070674370204700307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics: Pearson New Internatinal Edition. Essex, England: Pearson Education Limited; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Temple JR, Shorey RC, Fite P, Stuart GL, Le VD. Substance use as a longitudinal predictor of the perpetration of teen dating violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42:596–606. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9877-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple JR, Shorey RC, Tortolero SR, Wolfe DA, Stuart GL. Importance of gender and attitudes about violence in the relationship between exposure to interparental violence and the perpetration of teen dating violence. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37:343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.02.001. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschann JM, Pasch LA, Flores E, Marin BV, Baisch EM, Wibbelsman CJ. Nonviolent aspects of interparental conflict and dating violence among adolescents. Journal of Family Issues. 2009;30:295–319. doi: 10.1177/0192513x08325010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Camp T, Hébert M, Guidi E, Lavoie F, Blais M. Teens’ self-efficacy to deal with dating violence as victim, perpetrator or bystander. International Review of Victimology. 2014;20:289–303. doi: 10.1177/0269758014521741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandello JA, Cohen D. Male honor and female fidelity: Implicit cultural scripts that perpetuate domestic violence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:997–1010. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vézina J, Hébert M. Risk factors for victimization in romantic relationships of young women: A review of empirical studies and implications for prevention. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2007;8:33–66. doi: 10.1177/1524838006297029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wekerle C, Leung E, Wall AM, MacMillan H, Boyle M, Trocme N, Waechter R. The contribution of childhood emotional abuse to teen dating violence among child protective services-involved youth. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33:45–58. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.12.006. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Wekerle C, Reitzel-Jaffe D, Lefebvre L. Factors associated with abusive relationships among maltreated and nonmaltreated youth. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:61–85. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Wekerle C, Scott K, Straatman AL, Grasley C. Predicting abuse in adolescent dating relationships over 1 year: The role of child maltreatment and trauma. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:406–415. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wothke W. Longitudinal and multrigroup modeling with missing data. In: Little TD, Schnabel KU, Baumert J, editors. Modeling longitudinal and multilevel data: Practical issues, applied approaches, and specific examples. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2000. pp. 219–240. [Google Scholar]