Abstract

Stimulus-frequency otoacoustic emissions (SFOAEs) are reflection-source emissions, and are the least familiar and perhaps most underutilized otoacoustic emission. Here, normative SFOAE data are presented from a large group of 48 young adults at probe levels from 20 to 60 dB sound pressure level (SPL) across a four-octave frequency range to characterize the typical SFOAE and describe recent methodological advances that have made its measurement more efficient. In young-adult ears, SFOAE levels peaked in the low-to-mid frequencies at mean levels of ∼6–7 dB SPL while signal-to-noise ranged from 23 to 34 dB SPL and test-retest reliability was ±4 dB for 90% of the SFOAE data. On average, females had ∼2.5 dB higher SFOAE levels than males. SFOAE input/output functions showed near linear growth at low levels and a compression threshold averaging 35 dB SPL across frequency. SFOAE phase accumulated ∼32–36 cycles across four octaves on average, and showed level effects when converted to group delay: low-level probes produced longer SFOAE delays. A “break” in the normalized SFOAE delay was observed at 1.1 kHz on average, elucidating the location of the putative apical-basal transition. Technical innovations such as the concurrent sweeping of multiple frequency segments, post hoc suppressor decontamination, and a post hoc artifact-rejection technique were tested.

I. INTRODUCTION

At low and moderate sound levels, the stimulus-frequency otoacoustic emission (SFOAE) is thought to be created by the back-scattering of traveling-wave energy off natural biological irregularity (or “roughness”) along the cochlear spiral (Shera and Guinan, 1999). The emission is typically generated by a single low-level pure tone that produces reflection mostly at the site of the traveling-wave peak corresponding to the probe frequency. Here, we provide normative data about swept-tone SFOAEs, describing their magnitude, input/output (I/O) features, phase, and delay while also probing SFOAE reliability and describing sex effects in a large group of normal-hearing young adults. The data will provide familiarity with the SFOAE, which is lacking in the literature at present, and potentially a normative framework against which to detect and define hearing loss. Secondarily, this study explores and tests methodological innovations that have made the recording and measurement of SFOAEs rapid and efficient, potentially accelerating their utility in the laboratory and clinic.

There is little literature describing the normative features of the SFOAE in large groups of normal-hearing humans. Shera and Guinan (2003) and Schairer et al. (2006) have described the latency and delay features of the SFOAE in normal hearers, the former developing the normalized SFOAE delay or NSFOAE metric we utilize in this study. Schairer et al. (2003) also characterized SFOAE level and I/O features in young adults (Schairer et al., 2003) while, most recently, Dewey and Dhar (2017) recorded SFOAEs out to much higher frequencies than conventionally recorded (20 kHz) and examined the link between behavioral audiograms and SFOAEs.

This handful of studies has provided a glimpse of the SFOAE in the normal human cochlea for limited frequencies and levels, and for relatively small groups of ears in most cases. In the last decade, the SFOAE appears to have garnered slightly more attention as new measurement paradigms have been tested and the SFOAE has been measured over a wider parametric space (e.g., Shera and Bergevin, 2012; Kalluri and Shera, 2013; Abdala and Kalluri, 2017; Dewey and Dhar, 2017) At present there is no uniform or optimized protocol for the recording of SFOAEs. Our report considers several methodological advances that could make the measurement of the SFOAE more efficient, hence, more feasible for researchers and clinicians alike. For example, SFOAEs can be recorded by sweeping a tone continuously and smoothly across frequency rather than presenting pure tones at discrete frequencies (Kalluri and Shera, 2013); such a program is already in regular use with distortion-product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAEs) (Long et al., 2008; Abdala et al., 2015). Here, we test a swept-tone program for the measurement of SFOAEs in a large group of 48 young-adult ears to provide normative data while considering and measuring the impact of various technical innovations. The goal of this work is to make the SFOAE more familiar by characterizing its normative features in a large group of young-adult subjects and more feasible by enhancing the efficiency with which it can be measured.

II. METHODS

A. Subjects

Forty-eight young adults ranging in age from 18 to 31 yr [mean = 23 yr; standard deviation (SD) = 3.6 yr] participated as subjects in this study. Forty-five of these subjects provided normative data and three provided data to test a novel method of stimulus sweeping. Of the 45 normative subjects, 30 were female and 15 were male, including 30 right and 15 left ears. All subjects were normal-hearing and had audiometric thresholds ≤15 dB hearing level (HL) as determined by an audiogram performed with the Hughson-Westlake procedure in 2 dB steps at half-octave intervals between 500 and 8000 Hz.

B. Instrumentation and basic protocol

Stimulus generation and OAE acquisition were controlled using a custom matlab-based swept-tone algorithm via a Babyface USB 2.0 High Speed Audio Interface (RME Audio, Haimhausen, Germany) and an Etymotic Research ER-10 C probe system (Elk Grove Village, IL). The subjects were tested in a reclining ergonomic chair within a double-walled IAC sound booth (Bronx, NY) while watching a subtitled video. The ER-10 C probe cable was suspended from the ceiling of the sound booth to eliminate contact with chair or subject, then coupled to the ear from above with a nylon strap around the forehead of each participant.

Stimulus-frequency otoacoustic emissions (OAEs) were measured using a modified interleaved suppression paradigm (Shera and Guinan, 1999). Four intervals were presented: p1 = probe tone alone, p2 = suppressor tone (+ polarity) and probe, p3 = probe tone alone, and p4 = suppressor tone (− polarity) and probe. The SFOAE waveform was calculated as pSFOAE = (p1 + p3 – p2 – p4)/2, which resulted in two SFOAE measurements for each block of four intervals. Some techniques varied slightly in two sub-groups of subjects as detailed below. SFOAE probe tones were swept downward from 8.0 to 0.5 kHz at 20 and 40 dB SPL in 20 of the subjects and from 20 to 60 dB SPL (10 dB steps) in 25 of the subjects. The stimuli were swept tones whose instantaneous frequency decreased smoothly at a rate of 2 kHz/s or 2 octaves/s; the sweep was linear for 20 subjects and logarithmic for 25 of the subjects. OAE protocols using swept (versus discrete) pure tones optimize efficiency of data collection and match well with discrete-tone recordings (Kalluri and Shera, 2013; Abdala et al., 2015). The sweeps are rapid, allowing for hundreds of presentations, which in turn contributes to a robust OAE average. The swept-tone technique requires post hoc analysis, which provides flexible frequency resolution depending on the needs of each experiment and allows for re-analysis under varying conditions. The enhanced frequency resolution reduces ambiguities in phase unwrapping, allowing for stable estimates of the SFOAE delay. Here, we presented four “stacked” sweep segments concurrently rather than one long single sweep. This concurrent sweeping method is tested in Sec. III B, Methodological considerations.

When present, suppressor tones were swept simultaneously with the probe tone, either 50 Hz or 5% below the probe frequency. The suppressor was fixed at 55 dB SPL (n = 20) or presented at +15 dB re: probe level (n = 25). Based on pilot experimentation, we presented 384 sweeps at probe levels of 20 dB SPL, 256 at 30 dB SPL, and 192 for levels from 40 to 60 dB SPL. Using these sweep numbers achieved well above the minimal criteria signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Actual mean SNR (binned into 1/3 octave frequency bands) ranged from 22 to 34 dB SPL across level and frequency.

To mitigate the effect of ear-canal standing waves on stimulus level, calibrated stimuli were delivered to each subject after compensating for the depth of probe insertion (Lee et al., 2012). The half-wave resonance was recorded in the ear of each subject and associated with a probe insertion depth. The pressure response recorded at a matched insertion depth measured in an ear simulator (BK 4157, Naerum, Denmark) was used to compensate the frequency response of the sound sources and approximate a relatively flat response across frequency at the tympanic membrane. Calibration was conducted prior to each 64-sweep block throughout the test session. Additionally, as a measure of probe stability, we monitored the half-wave resonance peak in the ear canal every 12 min throughout the test. If it shifted more than 200 Hz, the probe was adjusted or refit as needed and calibration re-initiated.

C. SFOAE analysis

SFOAE levels and phases were estimated with a least squares fit (LSF) technique (Long et al., 2008; Kalluri and Shera, 2013; Abdala et al., 2015). To apply LSF modeling, the SFOAE time waveform, pSFOAE, recorded at the microphone is segmented into analysis windows, and models for the probe/SFOAE are created. The signal of interest within each analysis window is then estimated by a LSF, which minimizes the sum of the squared residuals between the model and the data to achieve the best fit. The noise floor was similarly estimated after phase-inverting every alternate sweep window. The bandwidth of the LSF analysis shifted as a function of frequency from 0.16 (at 500 Hz) to 0.05 octave (at 8 kHz) with the goal of keeping the number of SFOAE group-delay periods constant in each window. The LSF model was applied to the data in 0.01 octave steps and resulted in an SFOAE comprised of roughly 800 points across the 4-octave frequency range. To improve the SFOAE estimation, a delay term was implemented in the LSF analysis based on the SFOAE delay data reported in Shera et al. (2002).

SFOAEs were processed with the inverse fast Fourier transform (IFFT). The SFOAE residual includes coherent reflections backscattered from the place on the cochlea associated with the probe frequency (near the peak of the traveling wave) but also longer-latency multiple internal reflections (MIRs). MIRs occur when out-going waves reflect from the stapes footplate back into the cochlea; they peak at the probe frequency site and are re-reflected basal- ward, contributing as a component of the SFOAE measured in the ear canal (Dhar et al., 2002; Konrad-Martin and Keefe, 2005; Sisto et al., 2013). MIRs can contaminate estimates of SFOAE delay, and the fine-structure they produce is mostly non-informative. To focus on the primary reflection at the probe frequency and eliminate longer-latency contributions, various signal processing methods have been implemented (e.g., Konrad-Martin and Keefe, 2005; Schairer et al., 2006; Shera and Bergevin, 2012; Abdala et al., 2014a; Mishra and Biswal, 2016).

To apply the IFFT, SFOAE data were resampled with 12-Hz frequency resolution. Overlapping (50-Hz overlap) Hann-windowed segments of the SFOAE were transformed into the time domain using the IFFT. Impulse response (IPR) functions in the time domain were created for each window, and rectangular time-domain filters were applied to each IPR to isolate the main reflection of the SFOAE from the region associated with the probe frequency. The rectangular window varied in duration from 6.3 ms at the lowest frequency to 2.1 ms at the highest frequency and was centered around the peak of maximum energy detected between 0 and 20 ms (a time frame encompassing the main SFOAE reflection). Longer-latency energy was eliminated as a consequence of this windowing. The windowed data were then transformed back into the frequency domain using the fast Fourier transform (FFT). The ear-canal noise floor was processed through the same time windows used to extract SFOAE and became the referent noise floor. Edge effects intrinsic to time-windowing were avoided by eliminating one-quarter to one-half of the analysis-window length at both ends of the frequency range.

III. RESULTS

A. Normative SFOAE data

1. SFOAE level and reliability

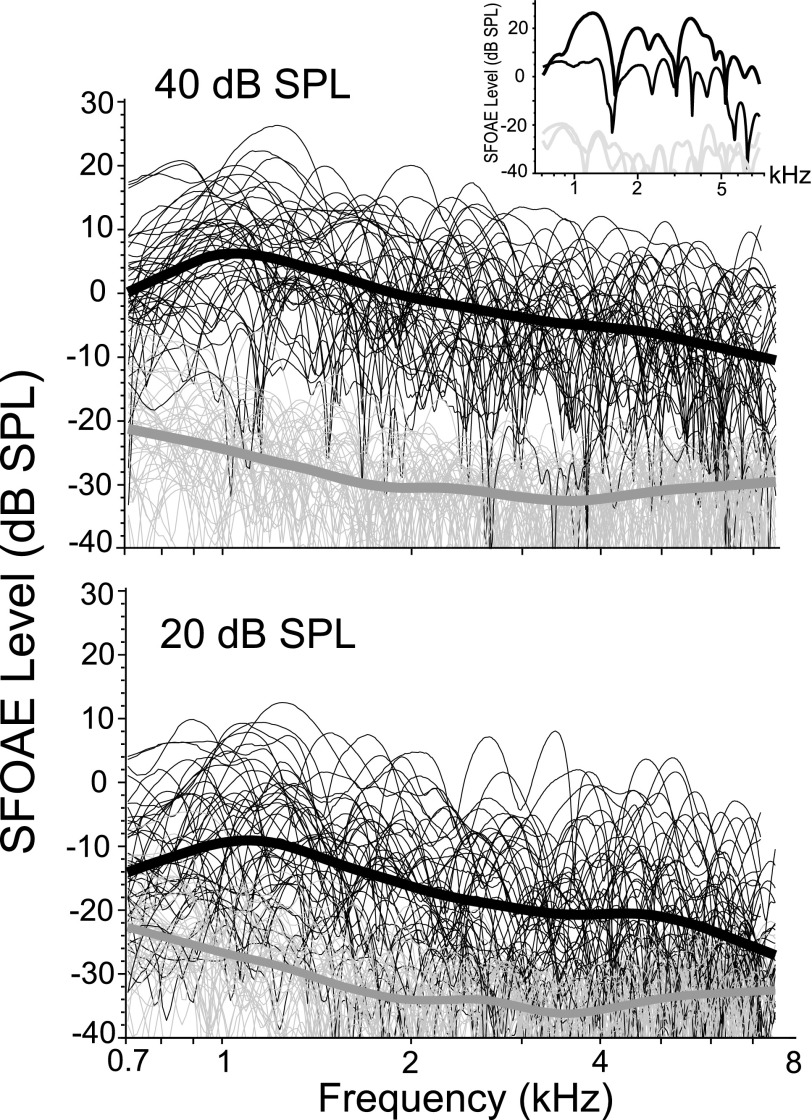

Individual SFOAE spectra are shown in the inset of Fig. 1 for one young-adult subject at two levels: 40 dB SPL and 20 dB SPL to illustrate a typical SFOAE. The 2 large panels in Fig. 1 display all SFOAE level data from each of the 45 ears with a loess trend line (Cleveland, 1993) superimposed on the individual spectra to help visualize the central tendency across frequency. To make SFOAE level data more tractable for analysis, we binned all level data into 1/3 octave frequency-bands denoted by center frequency; only those frequency bands with at least 9 dB SNR were included in the analyses. The peak of SFOAE level was observed at a center frequency of 990 Hz, with an average amplitude of 6.5 dB SPL (SD = 8.3 dB). SFOAEs measured at a center frequency of 1247 Hz had a mean level of 5.6 dB SPL (SD = 7.6 dB). On either side of this peak in SFOAE level between roughly 1 to 1.3 kHz, levels dropped off, though more markedly on the high-frequency end. These frequency-dependent results are evident in the trend line shown in Fig. 1. Others have described a high-frequency drop-off for SFOAEs in adult ears as well (Dewey and Dhar, 2017).

FIG. 1.

SFOAE amplitude spectra from 45 young-adult ears at two levels; all data are plotted with no SNR selection criteria imposed. The thin lines represent individual spectra while the thicker black line is a loess fit to the data to help visualize the trend. The noise floor is shown in gray. The inset to the upper panel shows SFOAEs recorded in one individual ear at 40 and 20 dB SPL, and gives an idea of the typical morphology and macrostructure of the SFOAE. The peaks, plateaus, and deep notches are intrinsic features of the SFOAE, and are associated with its fundamental generation mechanism rooted in the backscattering of wave energy off cochlear irregularity.

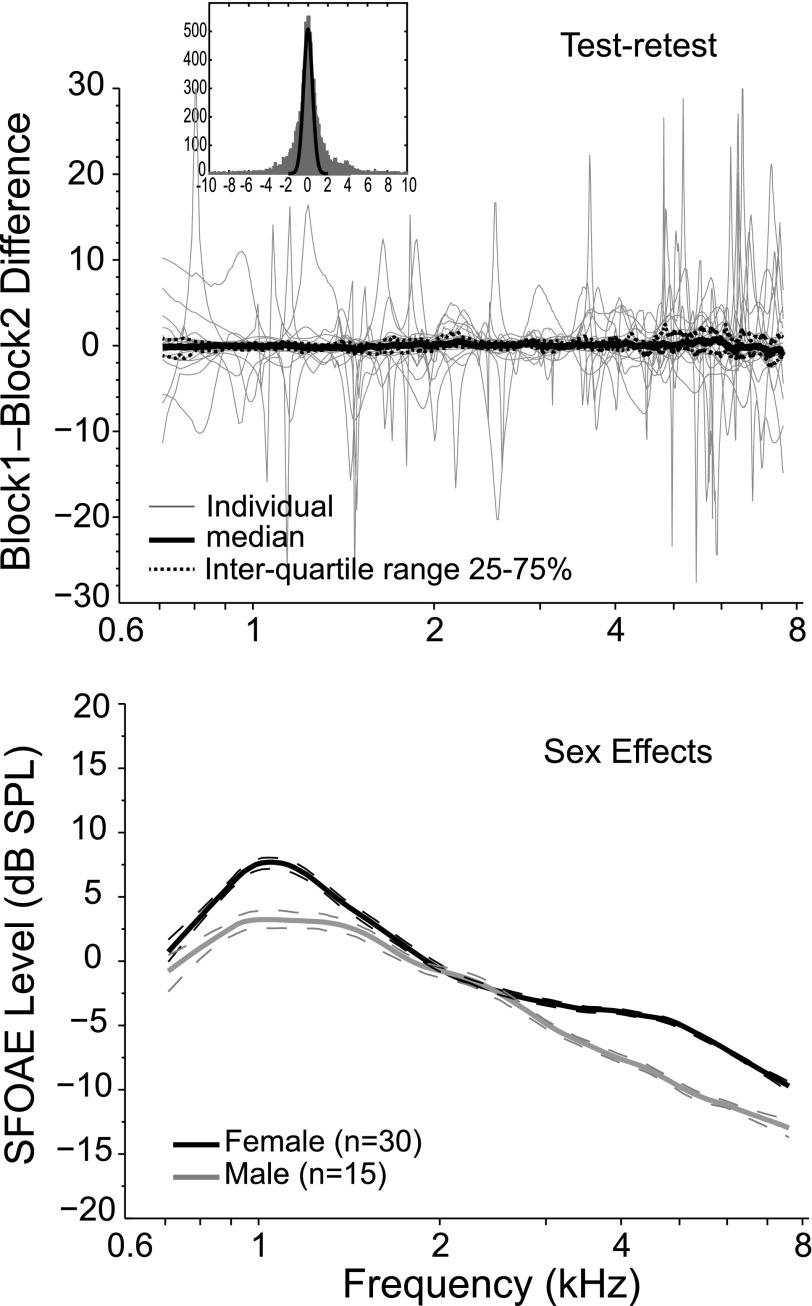

The data from these 45 young-adults were split by sex (male/female = 15/30), and a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to test SFOAE level for sex and frequency effects. Effects of sex (F = 8.97; p = 0.0029) and frequency (F = 15.58; p < 0.0001) on SFOAE level were observed with no interaction between these factors. On average, females had 2.5 dB higher SFOAE levels than the males across frequency, as shown in the lower panel of Fig. 2. No obvious sex effects were noted on SFOAE phase.

FIG. 2.

The upper panel shows the individual (thin gray lines) and median (thick black lines) differences between two blocks of data collected during one test session as a measure of test-retest reliability. The dashed lines around the median represent the inter-quartile 50% of difference scores from 25% to 75% and encompass differences no greater than ±1 dB. Large differences evident in some of the individual data are from measures taken at notches in the SFOAE spectra and do not represent the much greater stability of SFOAE measures taken at the peaks in SFOAE macrostructure. The inset histogram shows the distribution of difference scores with a best Gaussian fit to the peak (i.e., to the most stable part of the response). The distribution shows long tails falling outside of a normal distribution, which reflect the more outlier data measured at minima. The lower panel shows loess trend lines elucidating SFOAE level data from 15 males and 30 females. There is a significant effect of sex on SFOAE level with females having mean amplitudes 2.5 dB higher than males.

The upper panel of Fig. 2 provides test-retest reliability of SFOAE level for a probe at 40 dB SPL. The number of sweeps presented during a test session was divided into two blocks and two independent averages of SFOAE level were calculated for each subject; the difference in dB between block 1 and 2 SFOAEs provides a metric of test-retest reliability. The median difference is shown by the black line centered around 0 dB while the dashed lines depict the inter-quartile difference scores between 25% and 75%. The thin gray lines are difference scores from individual ears. The median block1-to-block2 difference for the most stable 50% of the SFOAE ranged from −0.70 to 0.89 dB across frequency, indicating that half of the SFOAE measures were repeatable to less than ±1 dB overall. However, it is clear from Fig. 2 that individual differences could be much larger for any given ear. It is helpful to consider what these larger deflections represent. The stable part of SFOAE (i.e., the 50% centered near the median value) comes from the plateaus and peaks in SFOAE spectra. In contrast, at SFOAE minima any small change in probe positioning due to swallowing (which activates the eustachian tube), or subject movement, for example, can alter SFOAE phase and amplitude patterns. Such a shift also alters the phase interactions among individual SFOAE components, which can produce marked swings in amplitude from one measurement to the next. However, these large differences do not characterize the stability of the SFOAE when measured at plateaus and peaks, which offer optimal stability, the most robust SNR (Abdala and Kalluri, 2017; Kalluri and Shera, 2013), and the best estimate of SFOAE latency (Shera and Bergevin, 2012).

To further explore this idea, we calculated the block1-to-block2 differences for 90% of the SFOAE data, which include many more outliers than our earlier calculation. The mean test-retest difference score is now within ±4 dB of the median difference. The histogram shown as an inset in Fig. 2 plots the distribution of difference scores. A Gaussian fit to the tip of this histogram (i.e., to the most stable data) is overlaid on the plot and illustrates that the difference score distribution has long tails on either side, deviating from a normal distribution. The “tail” data are the levels measured at minima in the SFOAE spectra. Arguably, the more representative stability, and that which matters when recording SFOAEs for hearing assessment purposes, is represented by the 50% inter-quartile range shown in Fig. 2, derived from peaks in SFOAE shape or macrostructure. Hence, the fundamental morphology of the SFOAE remained stable over the course of a test session and across two recording blocks, which sometimes included a refit of the probe. Our findings confirm that it is optimal to measure and characterize SFOAEs at spectral peaks and plateaus and to avoid measurement at minima.

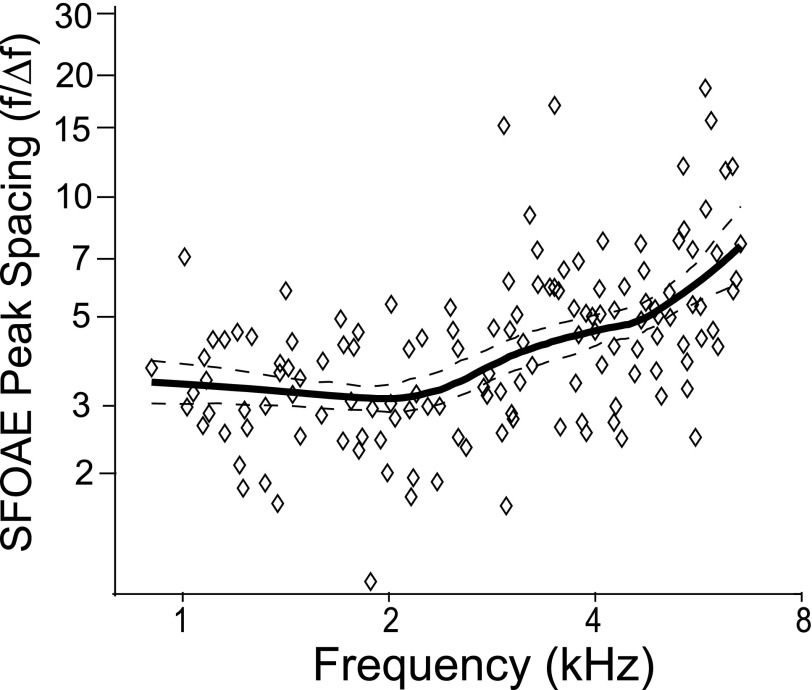

The typical morphology of the SFOAE spectrum, or what we term here as SFOAE macrostructure, was quantified at 40 dB SPL. Because the SFOAE is processed by the IFFT, which eliminates longer-latency energy due to MIRs (see Sec. II C, Methods), the microstructure has been mostly removed. As a result, here we are characterizing the broader, general outline of the response (i.e., macrostructure), rather than small-scale fluctuations. We characterize this macrostructure by quantifying the number of peaks per octave and the spacing of these peaks. A peak-picking algorithm was applied to the SFOAE, detecting peaks that extended at least 1 dB beyond the minima on either side and were at least 9 dB above the noise floor. (The noise floor was calculated as the median of a 100 Hz noise band centered around peak frequency.) On average, the highest octave (4–8 kHz) contained nearly three peaks while the octave from 0.5 to 1 kHz averaged less than one, indicating that SFOAEs have more spectral structure at higher frequencies.1 Figure 3 shows the fractional frequency spacing between SFOAE peaks, calculated as the geometric mean frequency of peak1 and peak2 (f) divided by the frequency difference (Δf) between them (f/Δf); larger values indicate narrower spacing. Spacing between SFOAE peaks decreases with increasing frequency. Between 0.7 and 7.2 kHz, the median value of f/Δf doubles, indicating systematically narrower spacing, consistent with the greater number of peaks per octave. The relationship between peak spacing and SFOAE delay will be considered in Sec. IV, Discussion.

FIG. 3.

SFOAE macrostructure spacing quantified by the dimensionless ratio f/Δf (see text) so that larger numbers represent more closely spaced peaks. A loess trend line (solid) and its 95% confidence intervals (dashed) are included to guide the eye.

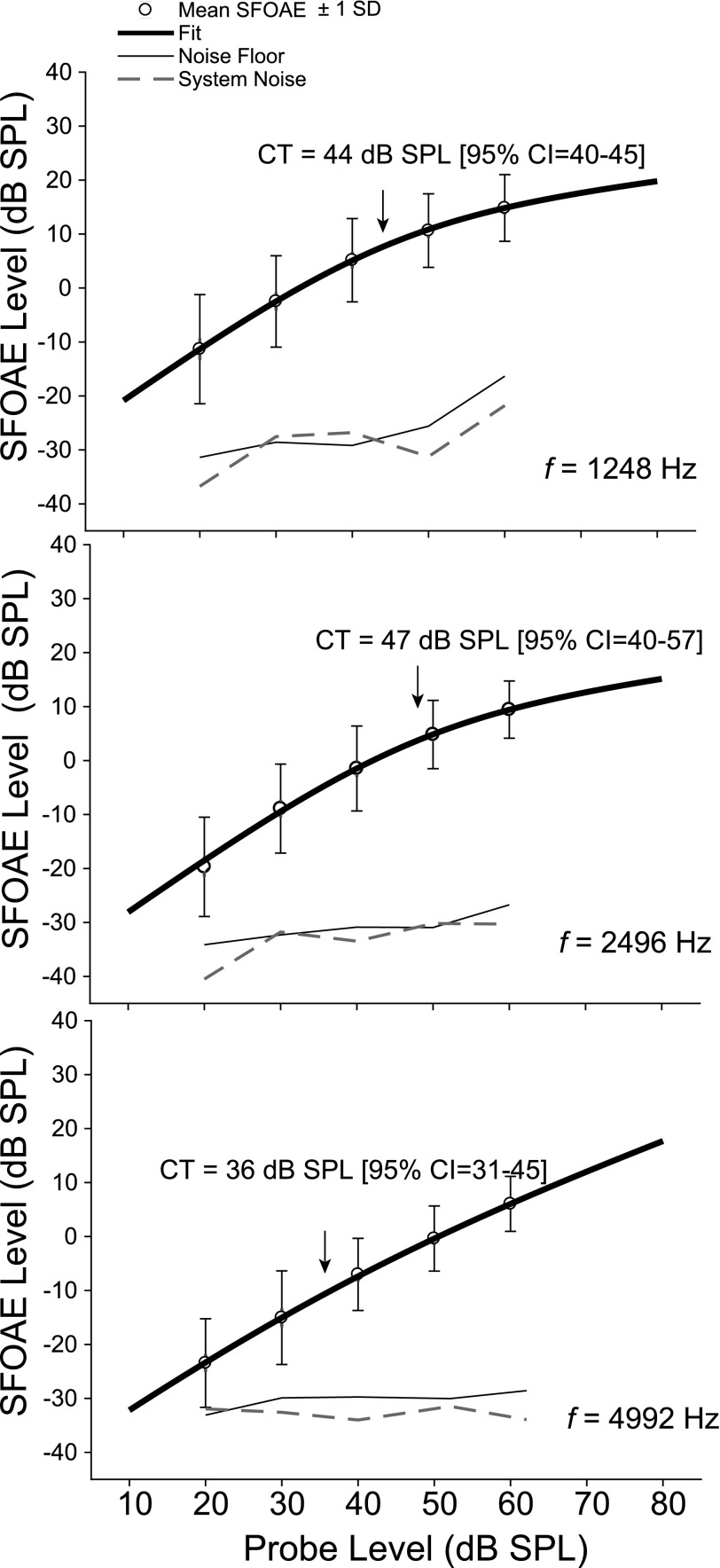

2. I/O functions

SFOAEs were recorded from 20 to 60 dB SPL (10 dB steps) in 25 subjects to generate I/O functions and quantify both the growth of the SFOAE across level and its compression features. As with the amplitude analysis above, SFOAE level was binned into third-octave frequency bands with center frequencies between 780 and 6288 Hz and I/O functions were generated at each center frequency for each subject. Group mean I/O functions were then calculated using all data points that met or exceeded 9 dB SNR re: noise floor and system noise, which was measured by running the SFOAE protocol in an ear simulator. Figure 4 shows exemplar group mean I/O functions for a low, mid, and high center frequency. The mean noise floor (100 Hz noise band centered around the center frequency) and system noise are also shown as thin and dashed black lines. The black line fit to the mean data is based on a fit originally described by Kalluri and Shera (2007b) to characterize SFOAE transfer functions. It was adapted here for I/O functions

T0 is a dimensionless constant that sets the overall scale; P is the amplitude of the stimulus pressure in pascals; PCT denotes the compression threshold (CT); the corresponding sound-pressure level is LCT = 20 log10(PCT/20 μPa), which is the stimulus level at which the OAE begins to grow compressively. 1-α is the asymptotic compressive slope, although for our purposes, local slopes were calculated at fixed levels above (60 dB SPL) and below (20 dB SPL) LCT.

FIG. 4.

Group mean SFOAE I/O functions (±1 SD) were generated at eight center frequencies of a third-octave frequency band. Three exemplars (1248 Hz, 2496 Hz, and 4992 Hz) are shown here. A fit (black line) to the I/O function was used to derive estimates of the CT, defined as the stimulus level at which the SFOAE begins to grow compressively. The CT and the 95% confidence intervals are provided for each of these three examples. The dashed line shows system distortion (measured in an ear simulator), whereas the thin black line is the mean noise floor centered at the test frequency band.

The CT of the SFOAE I/O function ranged from 37 to 50 dB SPL, decreasing with increasing frequency. The lowest CTs (35–36 dB SPL) were observed at 3960, 4992 Hz, and 6288 Hz. The overall SFOAE CT averaged across all frequencies was 43 dB SPL.2 The local slope calculated in the low-level regime of the function at 20 dB SPL averaged 0.92 dB/dB (range = 0.86–0.98 dB/dB), approaching linear growth as expected from models and experimental work (Shera and Zweig, 1993; Schairer et al., 2003). Slope measured above the CT at 60 dB SPL averaged 0.26 dB/dB (range = 0.09–0.51 dB/dB), showing highly compressed SFOAE growth at the higher stimulus levels.

3. SFOAE phase and delay

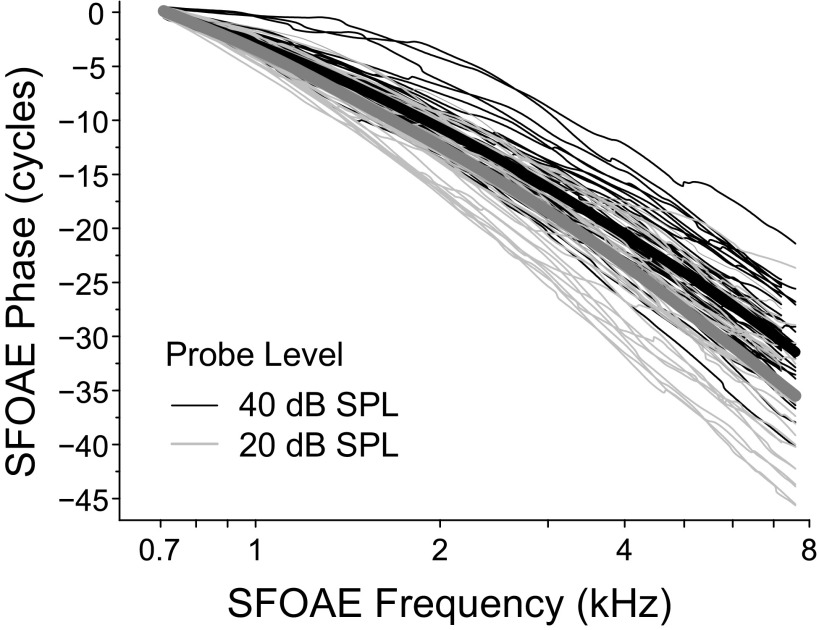

Figure 5 shows phase-versus-frequency functions on a log frequency axis for 45 subjects at 2 probe levels: 40 dB SPL (black lines) and 20 dB SPL (gray lines). A loess trend line was fit to both sets of phase curves (thick lines). At 40 dB SPL, the average SFOAE rotates through approximately 32 cycles (range = 23–40 cycles). Phase accumulation increases as the probe level decreases as shown by the steeper phase slope at 20 dB SPL, which accumulates nearly 36 cycles (range = 25–46 cycles). On a log axis, a steeper phase slope represents a longer group delay (in periods).

FIG. 5.

SFOAE phase versus frequency functions at two probe levels for all 45 subjects with loess trend lines superimposed on each set of data. The SFOAE phase rotates through approximately 30–36 cycles across the measured frequency range. The lower level probe (20 dB SPL) produces a steeper phase slope, and thus a longer phase-gradient delay, than the 40 dB SPL probe.

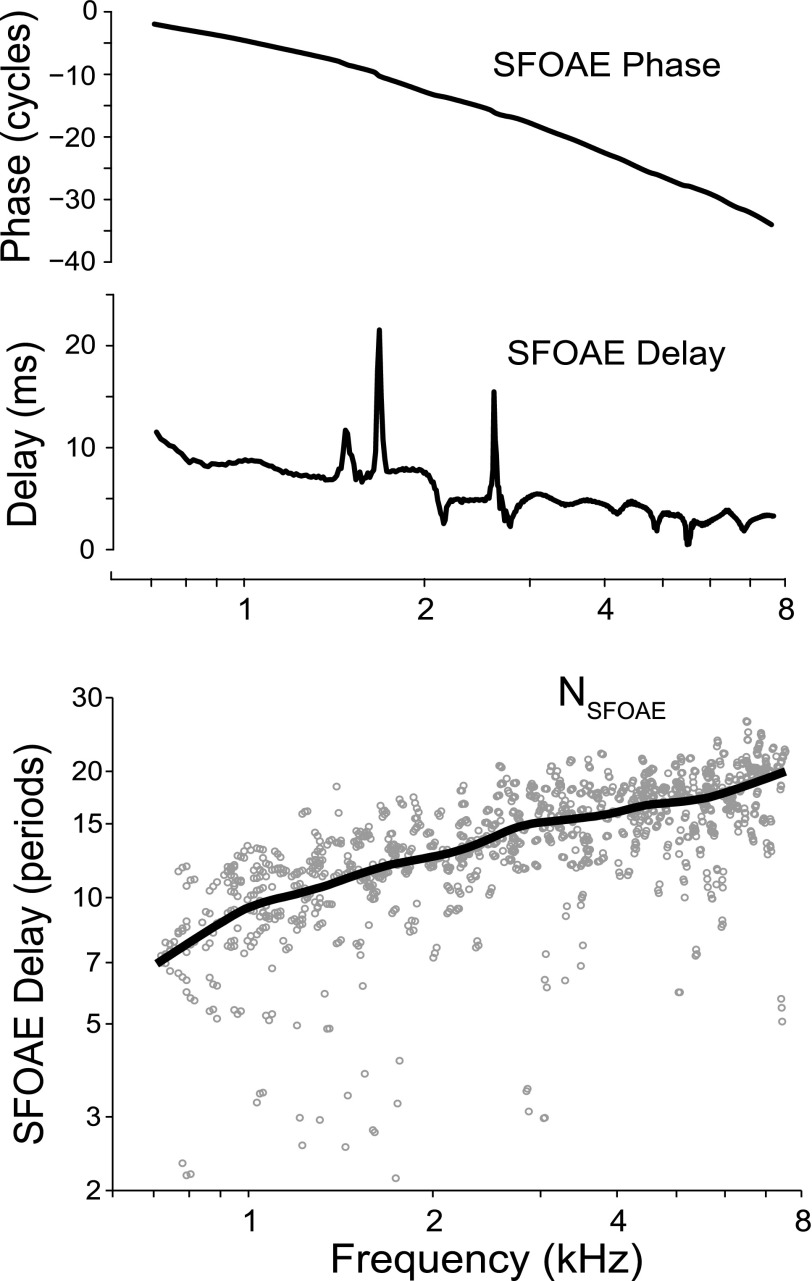

SFOAE delay was expressed following the convention of Shera and Guinan (2003), as a dimensionless variable representing the delay measured in periods of the stimulus frequency. Figure 6 illustrates how SFOAE delay is normalized in this manner. The top panel shows a typical SFOAE phase-versus-frequency function on a log frequency axis, much like those shown in Fig. 5. SFOAE phase is then converted to a group (or phase-gradient) delay by calculating the negative of the phase slope in milliseconds as τ(f) = −dϕSFOAE/df, where f is in kHz, and ϕSFOAE(f) is the SFOAE phase in cycles (Fig. 6, middle panel). This delay is then normalized and made dimensionless by calculating the equivalent number, N, of periods of the stimulus frequency: NSFOAE = fτ(f). (The normalization process is equivalent to computing the phase slope on a log-frequency axis: NSFOAE = –dϕSFOAE/dlnf.) Individual values of the dimensionless SFOAE delay, NSFOAE, are shown in the bottom panel of Fig. 6 for a 40 dB SPL probe as gray circles with a loess trend line superimposed on the group data.

FIG. 6.

Normalizing SFOAE delays: A typical SFOAE phase versus frequency function is shown in the upper panel. A delay is calculated from the phase as τ(f) = –dϕSFOAE/df, where ϕSFOAE(f) is the SFOAE phase in cycles (middle). The delay is then normalized and converted to dimensionless units by calculating the equivalent number of periods of the stimulus frequency: NSFOAE = fτ(f). The bottom panel shows NSFOAE from 45 young-adult ears (gray dots) at 40 dB SPL with a loess line superimposed to elucidate the trend.

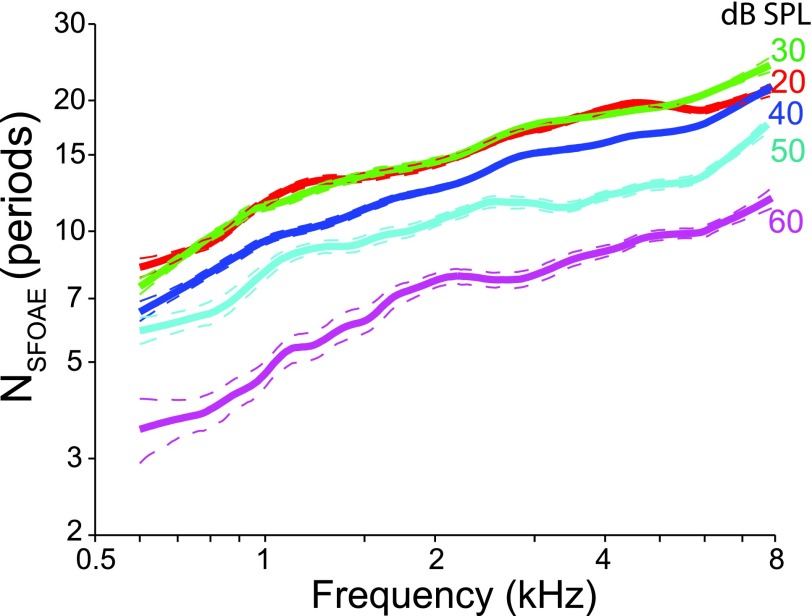

Figure 7 displays the trend lines that were fit to NSFOAE at each of five stimulus levels. At the lowest levels, where cochlear mechanics appears approximately linear (Robles and Ruggero, 2001), the delays are long and independent of level. Above about 30 dB SPL, however, the delays decrease strongly with level, as reported previously in smaller groups of subjects (Schairer et al., 2006). Finding longer delays at lower probe levels is not surprising given that SFOAE delays have been reliably linked to the sharpness of cochlear tuning and tuning is strongly level dependent, becoming sharper as probe levels decrease. The relationship between tuning and SFOAE delay has been demonstrated across frequency (at a fixed level) in groups of humans and in laboratory animals, including other primates (Shera et al., 2002, 2010; Joris et al., 2011); the longer the SFOAE delay, the sharper the tuning as gauged by auditory-nerve-fiber tuning curves in laboratory animals and psychoacoustic tuning curves for humans. The variation in delay with level found here (a factor of 2–3 between 20 and 60 dB SPL) roughly matches the mean variation in the sharpness of DPOAE suppression tuning curves (STCs) over the same level range (Abdala, 2001; Gorga et al., 2011). Although the level dependence of the delay appears similar across frequency, the level variation in the STC Q values is small below 1 kHz and increases at higher frequencies.

FIG. 7.

(Color online) Loess trend lines fit to the normalized SFOAE delay, NSFOAE, from 25 ears as a function of frequency with probe level (20–60 dB SPL) as the parameter. The dashed lines are the 95% confidence intervals. The individual delay values are not presented so as to more easily visualize the effects of stimulus level on NSFOAE. There is a clear effect of probe level on SFOAE delay, with NSFOAE generally increasing at lower stimulus levels. At the lowest probe levels, where cochlear mechanics become approximately linear, the delays are independent of level.

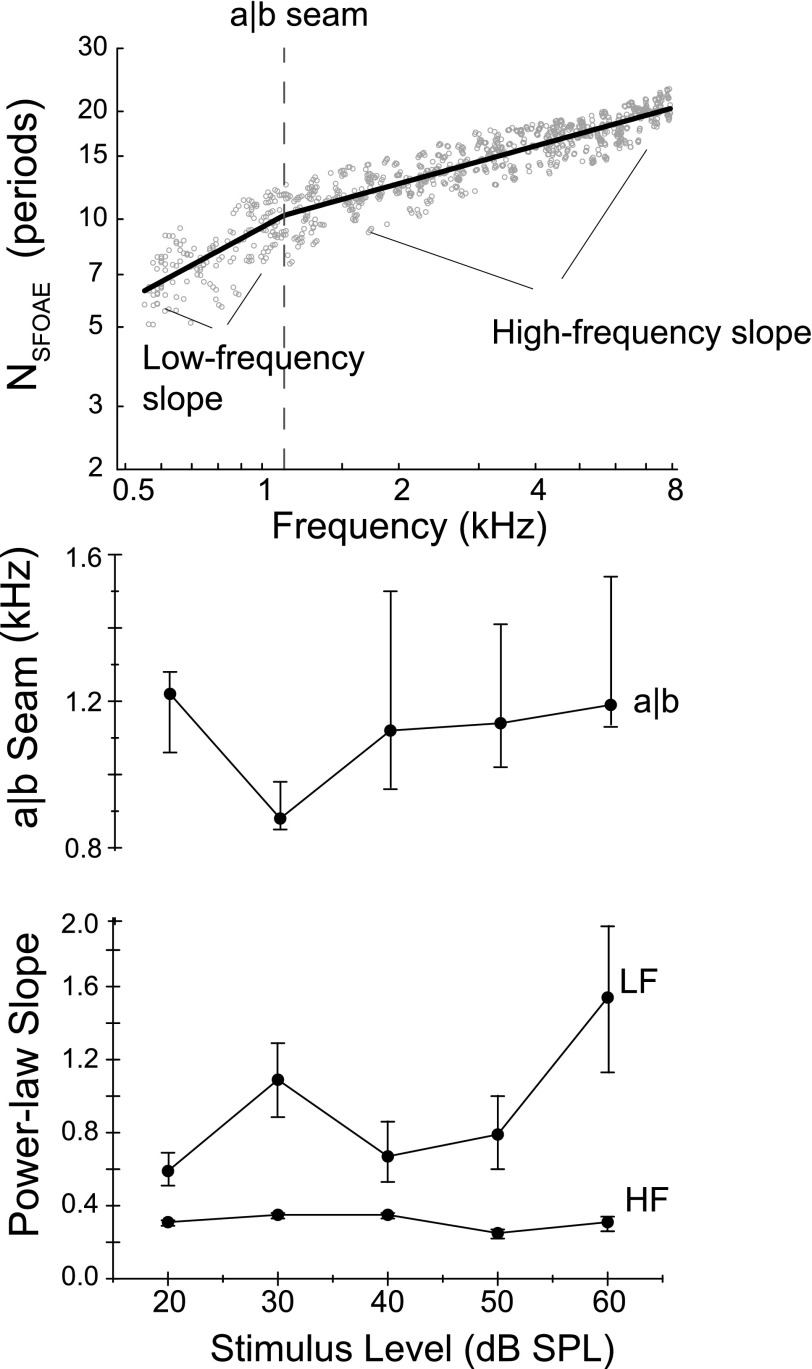

The NSFOAE group data at 40 dB SPL were fit with two intersecting power-laws (i.e., straight lines on log-log axes) where the point of intersection was a free parameter and represents the frequency where the slope of the SFOAE delay changes (see Fig. 8, top panel). At frequencies above this intersection, the slope was relatively shallow, while below it the slope steepened and decreased more rapidly. The intersection frequency has used to estimate the putative apical-basal (a|b) transition frequency. The segment above this frequency is thought to be approximately scaling symmetric,3 whereas the segment below the a|b seam deviates from scaling behavior (Shera and Guinan 2003; Abdala et al., 2011b).

FIG. 8.

The top panel displays individual NSFOAE values across frequency at 40 dB SPL. The delays are fit with two intersecting power-laws (i.e., straight lines on log-log axes) where the point of intersection is a free parameter representing the frequency at which the slope of the SFOAE delay changes (e.g., the location of the putative apical-basal, a|b, transition). The group a|b transition was estimated, as were the power-law slopes of the NSFOAE function above and below this frequency. The bottom two panels show the group means for each of these parameters. The mean a|b seam was around 1.1 kHz for all probe levels. The low-frequency (LF) slope appears to steepen with increased stimulus level, while the high-frequency (HF) slope remains roughly invariant across level.

The middle and bottom panels of Fig. 8 show the group mean a|b transition frequency and the power-law slope above and below this frequency as a function of stimulus level for 25 ears. The mean a|b transition in these young adults is 1.1 kHz. It does not vary greatly across stimulus level and ranges from 0.8 to 1.2 kHz, which is consistent with what has been previously described for the apical-basal transition elucidated by NSFOAE (Shera and Guinan, 2003). The low-frequency slope changes across stimulus level and appears to become steeper with increasing level. The high-frequency slope (in the scaled region of the cochlea) is shallow and does not vary across level.

While these data provide a normative framework, we note that estimates of SFOAE level and phase can vary depending on how the OAE is measured and analyzed. Section III B considers three methodological innovations and probes their effects on the SFOAE.

B. Methodological considerations

1. Concurrent frequency segments

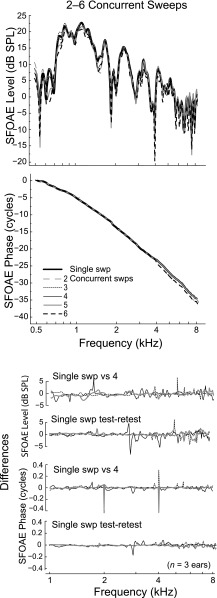

Our novel sweeping method involved the simultaneous presentation of multiple, concurrent frequency sweeps rather than one long continuous sweep spanning the entire targeted frequency range. Concurrent sweeping covers the range more quickly by dividing the total frequency range into Nseg partially overlapping segments, and presenting multiple sweeps that span these individual segments simultaneously in a “stacked” fashion. This innovation takes an already rapid technique and reduces the data collection time by a factor of approximately Nseg compared to the time required for a conventional single sweep spanning the same total range.

However, if Nseg is too large, and the concurrent segments are presented with starting frequencies too close together, there is danger of unwanted interaction between segments (e.g., via suppression). Here, we studied the effects of concurrent sweeping in three young-adult subjects to define the required separation between starting frequencies and examine the effects of this parameter on SFOAE level and phase. The single-sweep SFOAE (Nseg = 1), which has already been validated, served as the gold standard against which to compare the concurrent sweeping method. The upper and middle panels of Fig. 9 show SFOAE spectra and phase versus frequency functions for one ear in six different sweeping conditions corresponding to values Nseg = 1–6. The black line is the single-sweep referent (Nseg = 1). Data from the three ears indicate that stimuli with up to four segments (black thin line), which have start frequencies separated by at least one octave, provide excellent reproduction of the single-sweep SFOAE. This suggests little if any interaction among the four stacked frequency segments. If we present too many stacked segments, the resulting SFOAE spectra deviates slightly from the referent, as shown for the five- and six-segment conditions, consistent with possible interactions (see dashed black and solid gray lines compared to black solid lines).

FIG. 9.

The upper and middle panels show SFOAE spectra and phase versus frequency functions measured with various numbers of concurrent frequency segments in one ear. The concurrent sweeps with five and six segments have starting frequencies less than one octave apart and produced noticeable deviations from our gold standard, the single-sweep SFOAE. The lower panels show the differences between the level and phase of single-sweep SFOAEs versus four-segment SFOAEs in three subjects (each line-type represents a single subject). In general, the differences between single-sweep and four-stacked segments were minimal and comparable to typical test-retest repeatability within an ear.

The bottom panels show differences between SFOAE level/phase for the referent single-sweep and the Nseg = 4 stack used in this study in the three subjects; the normal test-retest reliability of a single-sweep for these same ears is also presented. The differences between the four-segment stack and the single-sweep are minimal and fall well within the normal intra-subject variability.

2. Suppressor decontamination

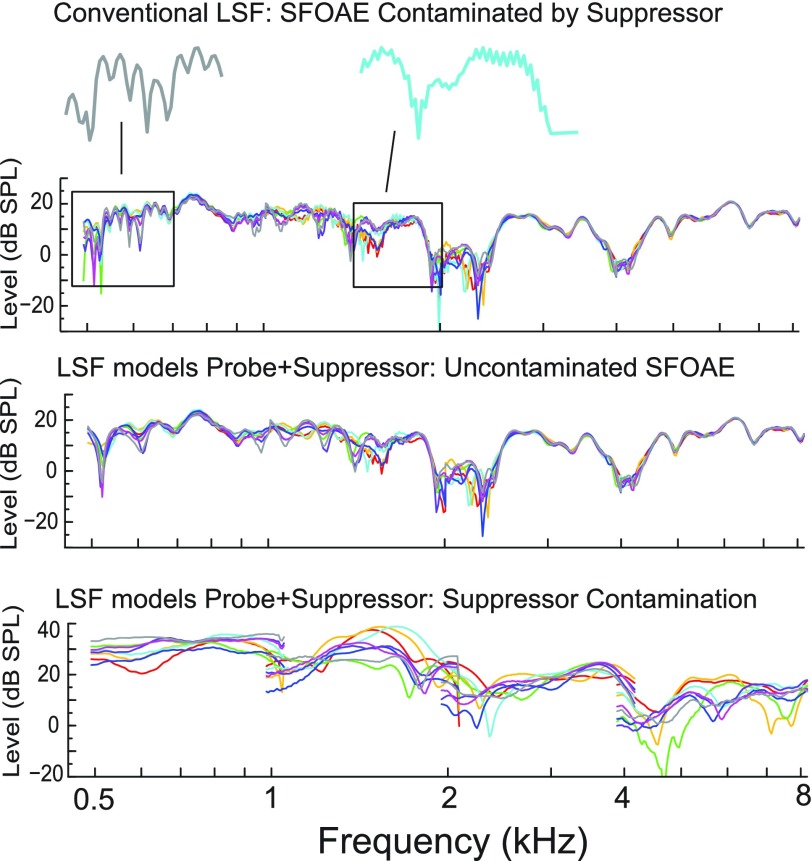

In the paradigm used here, the SFOAE was extracted as a residual because the probe and emission are at the same frequency. The interleaved suppression technique (Shera and Guinan, 1999) allows us to cancel the probe and suppressor and estimate this residual. However, when moderate-to-high-level probes and suppressors are presented, the cancellation of the suppressor is not always complete. This can occur when the transducers are slightly nonlinear or when shifts in the calibration or probe positioning occur during a test session. If the suppressor residual is significant (i.e., larger than the SFOAE), it can corrupt the recording. Here, we implemented an offline suppressor-decontamination analysis that corrects for this possibility. In addition to the standard LSF analysis, which models the probe to derive SFOAE estimates, we introduced a model of the suppressor tone into the LSF. This allowed us to estimate how much of the residual was suppressor-related and remove its contribution from the SFOAE average. An example of this decontamination process is shown in Fig. 10 for one ear.

FIG. 10.

(Color online) The top panel shows 8 averages of the SFOAE level (each comprised of 32 sweeps) evoked with a 60 dB SPL probe and 75 dB SPL suppressor-tone in one ear. Using a conventional application of the LSF, where only the response at the probe frequency is modeled to estimate the SFOAE, incomplete cancellation of the suppressor tone in the measured residual contaminates the LSF estimate of the SFOAE; the ripples riding atop the larger macrostructure give evidence of this contamination and are expanded in two places for easier visualization. The middle panel shows eight averages of the SFOAE level after applying an LSF analysis that also includes a model of the contaminating suppressor tone. The microstructure in the SFOAE is gone and the response is highly replicable in the eight averages. The lowest panel shows estimates of the contaminating suppressor tone extracted from the measured residual.

The topmost panel of Fig. 10 is an example of 8 repeated SFOAE averages from 1 ear (each average comprised of 32 sweeps) generated with a 60 dB SPL probe and 75 dB SPL suppressor tone. It was analyzed with a conventional LSF technique, which models only the probe-frequency component. One can see what is almost surely suppressor contamination by the microstructure evident in the SFOAE spectrum riding atop the larger macrostructure, below 2 kHz. Two small segments have been expanded to better visualize the effect. The middle panel of Fig. 10 shows the recalculated SFOAE analyzed using our modified LSF algorithm, which includes models of both the probe and the suppressor tone. The microstructure is mostly gone in this example, but the larger macrostructure of the response remains highly repeatable across the eight averages. The bottom panel shows eight examples of the contaminating suppressor tone identified by the LSF modeling. Consistent with significant variability in the amount of probe shift, and thus the amount of suppressor contamination that occurs from run to run, the replication is poor and estimates of the contamination vary by more than 20 dB SPL. In this study, all SFOAE measures were processed for suppressor decontamination. The implementation of this technique becomes particularly critical when recording SFOAE I/O functions, which necessarily extend the probe and suppressor to higher levels.

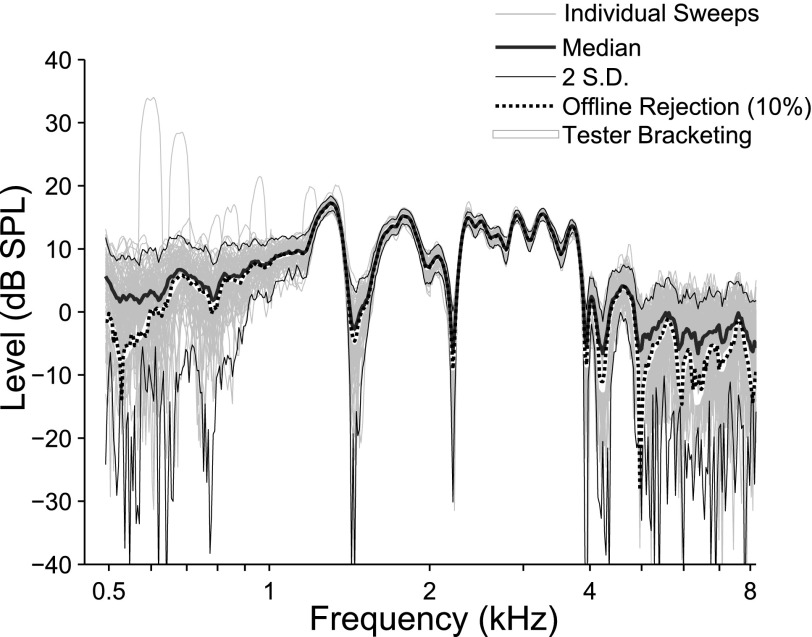

3. Artifact rejection

In this study, an online tester-directed artifact-rejection (AR1) strategy was employed. During data collection, the tester viewed an ongoing display of the SFOAE time waveform. She initially set a baseline threshold to remove marked spikes in the waveform with the rough goal of eliminating ∼10% of data points (corresponding to the most outlying values in each sweep). When an artifact exceeded the threshold, an interval extending 3 ms before and 3 ms after the spike was zeroed out prior to being added to the accumulating average and an additional sweep was presented to compensate for the rejected segment. The threshold was adjusted as needed throughout the session. Under this strategy, the final time-averaged SFOAE was comprised of slightly differing numbers of points at different frequencies, but clean data within a sweep were retained. Data collection continued until either a criterion number of artifact-free sweeps had been obtained or double the target number of sweeps had been presented.

As part of this study, a second tester-independent artifact-rejection strategy was tested (AR2) and applied in five ears for comparison to AR1. AR2 was an offline method that did not require tester participation. It detected outlier data in the frequency domain by comparing each incoming sweep analysis to a dynamic, real-time median of the accumulating SFOAE (see thick black line in Fig. 11). Each individual sweep was analyzed online with LSF (see thin gray lines) and compared to a dynamic calculation of 2 SDs bracketing this median (thin black line). Any frequency point in a sweep falling outside of the bracket was tagged as an artifact and triggered an additional sweep presentation; this ensured sufficient sweeps for a robust average even in noisier subjects. Data collection continued until the target number of artifact-free sweep segments was obtained. In relatively quiet young-adult subjects, most SFOAEs required approximately 10%–15% additional sweeping to achieve an average comprised of the target number of clean sweeps.

FIG. 11.

The AR1 procedure applied in this study involved a real-time tester-directed thresholding of the time waveform recorded at the microphone; the goal was elimination of roughly 10% of the data but the threshold was adjusted throughout the test as needed. This technique was compared with a more objective offline AR method. The thick black line in this figure is the median of the SFOAE and the thin lines bracketing this value display ±1 SD, both values are dynamically updated throughout the test session. The thin gray lines are the SFOAE estimates for each individual sweep. To compare both AR methods, one should compare the white line and the dashed black line. The white line shows the complex average of the SFOAE based on the online tester-directed technique. The dashed line shows the alternative strategy, where any artifactual spike exceeding two SDs from the median is considered an artifact and triggers an additional sweep. Offline, the noisiest sweeps are eliminated (i.e., those furthest from the median SFOAE). When 10% are eliminated in this ear (dashed black line), the SFOAE estimate is indistinguishable from the tester-directed method but puts no burden on the tester. For noisier subjects, more data may be rejected offline as needed.

Offline, a complex average of the SFOAE obtained from each individual sweep was calculated. The noisiest 10% of the data (or more) were eliminated based on their deviation from this grand average. Eliminating 10% of the data often left some of the detected artifacts in the average and may not be rigorous enough in a noisy subject, but for the quiet subject shown for Fig. 11, 10% post hoc elimination produced a clean and replicable SFOAE estimate (dashed line), comparable to the response recorded and analyzed using AR1 (compare white line to dashed line). There were insignificant differences between the SFOAE generated with the two methods in any of the five subjects tested.

IV. DISCUSSION

This study in a large group of 48 normal-hearing young adults suggests that swept-tone SFOAEs can be measured reliably and efficiently in young-adult ears. SFOAEs offer a useful laboratory tool to study cochlear mechanics and warrant further investigation as a clinical tool. Early work on the SFOAE may have been hampered by misperceptions that the response is not easily recorded due to technical challenges. Because the emission occurs at the same frequency as the probe that evoked it, robust methods of response extraction were developed to estimate the SFOAE accurately (see Schairer et al., 2003; Kalluri and Shera, 2007a). In this study, we employed a modified interleaved suppression method to extract the SFOAE, but others have used varied approaches, each with their own strengths and weaknesses. The SFOAE is a low-level response, often embedded in high levels of background noise, and it generally requires more averaging than the DPOAE to achieve adequate SNR. Although this is a drawback, methods such as the concurrent swept-tone technique described here can alleviate time concerns to some extent, allowing for the processing of hundreds of sweeps to produce a robust average and strong noise immunity.

The prevailing thought in the field has been that SFOAEs could not be recorded in ears with hearing loss due to low SNR. Although we did not study hearing loss in this report, past reports have countered this mistaken impression (e.g., Ellison and Keefe, 2005; Charaziak et al., 2015; Abdala and Kalluri, 2017). However, the utility of the SFOAE for the assessment of hearing has not been comprehensively explored. A large-scale study of the SFOAE in ears with auditory pathology, exploring its accuracy in the detection and characterization of hearing loss is warranted. Recent work from our laboratory has shown that SFOAEs can be recorded at multiple stimulus levels in mild-to-moderately impaired ears and can yield informative metrics of hearing health when recorded with DPOAEs as a joint protocol (Abdala and Kalluri, 2017). Many of these early misconceptions about SFOAEs, in addition to some of their real limitations, have likely hampered its integration into laboratory and clinical protocols.

A. SFOAE level

Our normative data here in 45 young-adult ears from 20 to 60 dB SPL for 0.5–8 kHz using swept-tone methodology show that SFOAEs are largest between 1 and 1.5 kHz, with mean peak levels approximating 6–7 dB on average and SNRs ranging from 22 to 34 dB across frequency. Others have successfully recorded SFOAES in young adults well beyond this upper frequency (Dewey and Dhar, 2017), although level drops relatively steeply for reflection emissions in the high-frequencies (Goodman et al., 2009; Rasetshwane and Neely, 2012), consistent with our observations in the current study. When considering the most stable SFOAE measurements, which are at peaks of the macrostructure, the test-retest reliability was excellent (±1 dB). If nearly all the data are considered, the intra-subject variability increased to ±4 dB, likely due to the inclusion of deep minima. We recommend measuring SFOAEs at maxima or plateaus in macrostructure only, to obtain the most stable and representative sample of the response and to optimize SNR. Here, we binned SFOAE magnitude into third-octave frequency bands. In doing so, we included data at minima as well as maxima, which reduced the average SFOAE levels. Even including these less stable SFOAE measurements at minima, test-retest reliability was roughly comparable to the reported reliability of TEOAEs (Franklin et al., 1992) and DPOAEs (Reavis et al., 2015; Dreisbach et al., 2017).

B. I/O functions

The I/O function of the SFOAE shows incipient compression at low-to-moderate levels as previously reported (Schairer et al., 2003; Abdala and Kalluri, 2017), with near-linear growth at the lowest levels. The CT appears to depend on the fitting procedures used to estimate it. Mean CTs measured in this study were slightly higher than those reported previously, both in a previous paper from our laboratory (Abdala and Kalluri, 2017) and a much earlier publication (Schairer et al., 2003). Abdala and Kalluri (2017) reported SFOAE CTs that varied from 20 dB to ∼40 dB across frequency, with an overall threshold of 33 dB SPL, which is lower than the 45 dB SPL threshold reported here. However, individual I/O functions were fit in Abdala and Kalluri (2017) rather than group-mean functions as done here, which likely alters the estimates. Individual fits were not possible in the present study because of limited resolution (i.e., five points per function using 10 dB steps).

A second factor that might have influenced the form of the I/O function and its estimate of CT is suppressor tone level. Here we used +15 dB SPL suppressor re: probe level for the 25 subjects in whom an I/O function was measured. This means that at the lowest probe levels the suppressor tone may not have extracted the entire SFOAE. Hence, in some ears the low-level end of the I/O function may contain only partial estimates of the SFOAE. This bias could have artificially steepened the low-level region of the function and altered estimates of CT. Combined, SFOAEs measured in our laboratory over the last year (current study combined with Abdala and Kalluri, 2017) produce mean SFOAE CTs 35 dB SPL overall. The average SFOAE CT is 6–10 dB lower than that derived for DPOAEs using the same fitting function (Ortmann and Abdala, 2016; Ortmann et al., 2017). This difference is not surprising, given that these two OAEs—one a reflection-source and the other a distortion-source OAE—have distinct generation mechanisms.

C. SFOAE phase and delay

There have been a number of attempts to associate the delay of the SFOAE or other reflection OAE with cochlear tuning and basilar-membrane mechanics (Shera et al., 2002, 2010; Shera and Guinan, 2003; Siegel et al., 2005; Schairer et al., 2006; Shera et al., 2008; Abdala et al., 2014b). Coherent-reflection theory predicts that the delays of SFOAEs evoked at low sound levels are determined by the round-trip travel time for the pressure-difference wave as it propagates between the stapes and the peak of the traveling wave (Shera et al., 2008). If forward and reverse travel times are equal, SFOAE delay would be expected to be twice the travel time to the site of the probe frequency. The theory also predicts that SFOAE delay varies with stimulus level (i.e., that delays increase at lower levels). These associations have been observed and documented in previous publications (Shera and Guinan, 2003; Schairer et al., 2006) and correlations between measures of tuning and SFOAE delay have been shown in a number of species (Shera et al., 2002; Shera et al., 2008; Shera et al., 2010; Joris et al., 2011).

Coherent-reflection theory also predicts that the spacing, Δf, between SFOAE macrostructure peaks (see Fig. 3) is largely determined by the width of the traveling-wave envelope near its peak (i.e., the spatial extent of the region where the principal scattering occurs). Based on the variability of SFOAE delays in humans, the theory predicts Δf to be roughly three times the frequency interval over which SFOAE phase changes by one cycle (Zweig and Shera, 1995). In other words, the theory predicts that NSFOAE/(f/Δf) ≈ 3. Comparison of the SFOAE peak spacing trends shown in Fig. 3 and the delays in Fig. 6 indicate that our data are consistent with this prediction.

In this study, we did not convert SFOAE delay into a measure of tuning using a species-independent tuning ratio used in the past for this purpose (Shera et al., 2010; Abdala et al., 2014b); however, if we simply consider SFOAE delay as a dimensionless unit (NSFOAE), we see a strong effect of level on delay (see Fig. 7). Also, the NSFOAE trend ranged from ∼7 to 18 periods from 0.5 to 8 kHz. The level effect we see here is similar to that described by Schairer et al. (2006), although we did not observe the flat, relatively scaled region of the NSFOAE above 1 kHz described by these researchers. They employed a technique to smooth the phase which may have influenced and flattened their delay data across frequency, and may explain the differences (Shera and Bergevin, 2012).

We detected a change in the slope of the SFOAE delay near 1.1 kHz and used this bend to estimate the apical-basal transition frequency. The break was defined as the frequency where the slope of NSFOAE transitioned from gradually sloping in the higher frequencies to a steeper decrease in slope at low frequencies. The DPOAE (recorded with a fixed f2/f1) also shows an invariant, scaled segment of its phase versus frequency function in the higher frequencies and a segment that violates scaling in the lower half of the frequency range (Abdala et al., 2011a,b; Christensen et al., 2017). The f2 associated with the DPOAE a|b break frequency averages ∼2.3 kHz, about an octave higher than the transition frequency found here. It is not clear whether the bends evident in the SFOAE and DPOAE delay data are indices of the same underlying mechanism (e.g., potential changes in cochlear tuning or tonotopic representation). If so, how they relate to one another is not clear from these data. This question is currently under study.

D. Optimizing methods

To use SFOAEs in the laboratory and, eventually, in the clinic, their measurement must be efficient, reliable, and rapid. This study represents the first large-scale measurement of SFOAEs using swept-tones as stimuli. The use of concurrently swept frequency segments makes the technique more efficient still, and combined with offline rejection of outliers, it offers an effective methodology for the measurement of SFOAEs in human ears. Our results suggest that an online detection, but offline rejection, of artifacts is more efficient than a tester-directed scheme. The tester-directed method is subject to the effects of personal experience and bias, and puts an undue burden on the tester. Only one tester (with more than two years of experience in OAE testing) conducted all data collection for this study, which presumably allowed for a uniform data-rejection strategy across sessions, but this will not always be the case. The same high-quality data set, relatively free of outliers, can be collected without reliance on tester experience and the bias it may introduce. The offline process offers objectivity and ultimate flexibility in the post hoc rejection of outliers.

To conclude, although our results from a large group of normal hearers are promising, the SFOAE needs to be measured in similarly large groups of individuals with varying degrees and etiologies of hearing loss. Pathological ears generally produce noisier data and more challenging recording conditions. The technical innovations described here may prove particularly helpful in these more difficult groups of subjects by allowing for the efficient and reliable measure of SFOAEs and for enhanced noise immunity. Such a study would also allow us to define the appropriate testing and analysis parameters for impaired ears, which may differ from those established here in healthy subjects. Providing reliable normative SFOAE data is an important first step toward realizing the clinical utility of the SFOAE; however, additional study in individuals with hearing loss is needed before the integration of SFOAE-based tests into the audiology clinic can be successful.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) Grant Nos. R01 DC003552 (C.A.) and R01 DC003687 (C.A.S.). The authors would like to thank Ping Luo for assistance in data management and analysis and Amanda Ortmann for data collection in a sub-group of 20 subjects analyzed for this study.

Footnotes

The lowest and highest frequency bands were not full octave-wide bands because a segment equal to half the analysis window was removed from the low- and high-frequency ends of the frequency range to eliminate edge-effects intrinsic to the IFFT time-windowing process; therefore, it is possible the lowest and highest frequency bins could have included more peaks per octave than the number reported here.

The confidence intervals for the fit-derived estimate of the CT parameter never exceeded 20 dB and were as low as 6 dB as noted for the center frequency of 1248 Hz shown in the top panel of Fig. 4.

Scaling indicates that cochlear tuning curves measured at two different locations have approximately similar shapes and the traveling wave accumulates a roughly equal number of cycles phase lag at the two locations.

References

- 1. Abdala, C. (2001). “ Maturation of the human cochlear amplifier: Distortion product otoacoustic emission suppression tuning curves recorded at low and high primary tone levels,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 110, 1465–1476. 10.1121/1.1388018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abdala, C. , Dhar, S. , Ahmadi, M. , and Luo, P. (2014a). “ Aging of the medial olivocochlear reflex and associations with speech perception,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 135, 754–765. 10.1121/1.4861841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abdala, C. , Dhar, S. , and Kalluri, R. (2011a). “ Deviations from cochlear scaling symmetry in the apical half of the human cochlea,” in What Fire is in Mine Ears: Progress in Auditory Biomechanics, edited by Shera C. A. and Olson E. S. ( AIP, Melville, NY: ), pp. 483–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abdala, C. , Dhar, S. , and Kalluri, R. (2011b). “ Level dependence of distortion product otoacoustic emission phase is attributed to component mixing,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 129, 3123–3133. 10.1121/1.3573992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abdala, C. , Guérit, F. , Luo, P. , and Shera, C. A. (2014b). “ Distortion-product otoacoustic emission reflection-component delays and cochlear tuning: Estimates from across the human lifespan,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 135, 1950–1958. 10.1121/1.4868357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abdala, C. , and Kalluri, R. (2017). “ Towards a joint reflection-distortion otoacoustic emission profile: Results in normal and impaired ears,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 142, 812–824. 10.1121/1.4996859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abdala, C. , Luo, P. , and Shera, C. A. (2015). “ Optimizing swept-tones to measure DPOAEs in adult and newborn ears,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 138, 3785–3799. 10.1121/1.4937611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abdala, C. , Luo, P. , and Shera, C. A. (2017). “ Characterizing spontaneous otoacoustic emissions across the human lifespan,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 141, 1874–1886. 10.1121/1.4977192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Charaziak, K. K. , Souza, P. E. , and Siegel, J. H. (2015). “ Exploration of stimulus-frequency otoacoustic emission suppression tuning in hearing-impaired listeners,” Int. J. Audiol. 54, 96–105. 10.3109/14992027.2014.941074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Christensen, A. , Ordoñez, T. , and Hammershøi, R. (2017). “ Distortion-product otoacoustic emission measured below 300 Hz in normal-hearing human subjects,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 18, 197–208. 10.1007/s10162-016-0600-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cleveland, W. S. (1993). Visualizing Data ( Hobart, Summit, NJ: ). [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dewey, J. B. , and Dhar, S. (2017). “ Profiles of stimulus-frequency otoacoustic emissions from 0.5 to 20 kHz in humans,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 18, 89–110. 10.1007/s10162-016-0588-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dhar, S. , Talmadge, C. L. , Long, G. R. , and Tubis, A. (2002). “ Multiple internal reflections in the cochlea and their effect on DPOAE fine structure,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 112, 2882–2897. 10.1121/1.1516757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dreisbach, L. , Zettner, E. , Chang Liu, M. , Meuel Fernhoff, C. , MacPhee, I. , and Boothroyd, A. (2017). “ High-frequency distortion-product otoacoustic emission repeatability in a patient population,” Ear Hear. 39, 85–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ellison, J. C. , and Keefe, D. H. (2005). “ Audiometric predictions using stimulus-frequency otoacoustic emissions and middle ear measurements,” Ear Hear. 26, 487–503. 10.1097/01.aud.0000179692.81851.3b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Franklin, D. J. , McCoy, M. J. , Martin, G. K. , and Lonsbury-Martin, B. (1992). “ Test/retest reliability of distortion-product and transiently evoked otoacoustic emissions,” Ear Hear. 13, 417–429. 10.1097/00003446-199212000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goodman, S. , Fitzpatrick, D. , Ellison, J. , Jesteadt, W. , and Keefe, D. (2009). “ High-frequency click-evoked otoacoustic emissions and behavioral thresholds in humans,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 125, 1014–1032. 10.1121/1.3056566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gorga, M. P. , Neely, S. T. , Kopun, J. , and Tan, H. (2011). “ Distortion-product otoacoustic emission suppression tuning curves in humans,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 129, 817–827. 10.1121/1.3531864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Joris, P. X. , Bergevin, C. , Kalluri, R. , McLaughlin, M. , Michelet, P. , van der Heijden, M. , and Shera, C. A. (2011). “ Frequency selectivity in Old-World monkeys corroborates sharp cochlear tuning in humans,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 17516–17520. 10.1073/pnas.1105867108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kalluri, R. , and Shera, C. A. (2007a). “ Comparing stimulus-frequency otoacoustic emissions measured by compression, suppression, and spectral smoothing,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 122, 3562–3575. 10.1121/1.2793604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kalluri, R. , and Shera, C. A. (2007b). “ Near equivalence of human click-evoked and stimulus-frequency emissions,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 121, 2097–2110. 10.1121/1.2435981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kalluri, R. , and Shera, C. A. (2013). “ Measuring stimulus-frequency otoacoustic emissions using swept-tones,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 134, 356–368. 10.1121/1.4807505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Konrad-Martin, D. , and Keefe, D. H. (2005). “ Transient-evoked stimulus-frequency and distortion-product otoacoustic emissions in normal and impaired ears,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 117, 3799–3815. 10.1121/1.1904403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee, J. , Dhar, S. , Abel, R. , Banakis, R. , Grolley, E. , Lee, J. , Zecker, S. , and Siegel, J. (2012). “ Behavioral hearing thresholds between 0.125 and 20 kHz using depth-compensated ear simulator calibration,” Ear Hear. 33, 315–329. 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31823d7917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Long, G. R. , Talmadge, C. L. , and Lee, J. (2008). “ Measuring distortion product otoacoustic emissions using continuously sweeping primaries,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 124, 1613–1626. 10.1121/1.2949505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mishra, S. K. , and Biswal, M. (2016). “ Time–frequency decomposition of click evoked otoacoustic emissions in children,” Hear. Res. 335, 161–178. 10.1016/j.heares.2016.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ortmann, A. J. , and Abdala, C. (2016). “ Changes in the compressive nonlinearity of the cochlea during early aging: Estimates from distortion OAE input/output functions,” Ear Hear. 37, 603–614. 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ortmann, A. J. , Guardia, Y. C. , and Abdala, C. (2017). “ Aging and cochlear nonlinearity as measured with distortion OAEs and loudness perception,” poster presented to the 40th Annual Midwinter Meeting of the Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol., Baltimore, MD, PS 82. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rasetshwane, D. , and Neely, M. (2012). “ Measurements of wide-band cochlear reflectance in humans,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 13, 591–607. 10.1007/s10162-012-0336-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Reavis, K. M. , McMillan, G. P. , Dille, M. F. , and Konrad-Martin, D. (2015). “ Meta-analysis of distortion product otoacoustic emission retest variability for serial monitoring of cochlear function in adults,” Ear Hear. 36, E251–E260. 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Robles, L. , and Ruggero, M. A. (2001). “ Mechanics of the mammalian cochlea,” Physiol. Rev. 81, 1305–1352. 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schairer, K. S. , Ellison, J. C. , Fitzpatrick, D. , and Keefe, D. H. (2006). “ Use of stimulus-frequency otoacoustic emission latency and level to investigate cochlear mechanics in human ears,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 120, 901–914. 10.1121/1.2214147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schairer, K. S. , Fitzpatrick, D. H. , and Keefe, D. (2003). “ Input-output functions for stimulus-frequency otoacoustic emissions in normal-hearing adult ears,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 114, 944–966. 10.1121/1.1592799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shera, C. A. , and Bergevin, C. (2012). “ Obtaining reliable phase-gradient delays from otoacoustic emissions data,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 132, 927–943. 10.1121/1.4730916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shera, C. A. , and Guinan, J. J., Jr. (1999). “ Evoked otoacoustic emissions arise by two fundamentally different mechanisms: A taxonomy for mammalian OAEs,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 105, 782–798. 10.1121/1.426948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shera, C. A. , and Guinan, J. J. (2003). “ Stimulus-frequency-emission group delay: A test of coherent reflection filtering and a window on cochlear tuning,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 113, 2762–2772. 10.1121/1.1557211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shera, C. A. , Guinan, J. J. , and Oxenham, A. J. (2002). “ Revised estimates of human cochlear tuning from otoacoustic and behavioral measurements,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 3318–3323. 10.1073/pnas.032675099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shera, C. A. , Guinan, J. J. , and Oxenham, A. J. (2010). “ Otoacoustic estimation of cochlear tuning: Validation in the chinchilla,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 11, 343–365. 10.1007/s10162-010-0217-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shera, C. A. , Tubis, A. , and Talmadge, C. (2008). “ Testing coherent reflection in chinchilla: Auditory-nerve responses predict stimulus-frequency emissions,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 124, 381–395. 10.1121/1.2917805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shera, C. A. , and Zweig, G. (1993). “ Noninvasive measurement of the cochlear traveling-wave ratio,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 93, 3333–3352. 10.1121/1.405717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Siegel, J. H. , Cerka, A. J. , Recio-Spinoso, A. , Temchin, A. N. , van Dijk, P. , and Ruggero, M. A. (2005). “ Delays of stimulus-frequency otoacoustic emissions and cochlear vibrations contradict the theory of coherent reflection filtering,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 118, 2434–2443. 10.1121/1.2005867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sisto, R. , Sanjust, F. , and Moleti, A. (2013). “ Input/output functions of different-latency components of transient-evoked and stimulus-frequency otoacoustic emissions,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 133, 2240–2253. 10.1121/1.4794382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zweig, G. , and Shera, C. A. (1995). “ The origin of periodicity in the spectrum of evoked otoacoustic emissions,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 98, 2018–2047. 10.1121/1.413320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]